Diabetes mellitus is characterised by chronic hyperglycaemia and is one of the most common chronic diseases. The prevalence of detected diabetes is around 3–4% in the general population 1 and set to double worldwide by 2030, Reference Wild, Roglic, Green, Sicree and King2 largely as a result of an ageing population and the epidemic of obesity. Reference Amos, McCarty and Zimmet3 The most common types of diabetes are types 1 and 2. Type 1 diabetes represents around 10–15% of all cases of diabetes and is associated with absolute insulin deficiency. Type 2 diabetes accounts for 85–90% of all cases and results from a combination of insulin resistance and relative insulin deficiency.

The prevalence of diabetes has been reported to be two- to threefold higher in people with schizophrenia than the general population. Reference Dixon, Weiden and Delahanty4–Reference Sernyak, Leslie, Alarcon, Losonczy and Rosenheck8 The reason for this increase is not well understood but likely to be multifactorial. Reference Holt, Peveler and Byrne9

There has been increasing concern that antipsychotics, especially the second-generation type, are also associated with an increased risk for diabetes in people with schizophrenia. Reference Ananth, Venkatesh, Burgoyne and Gunatilake10–Reference Henderson12 Despite this increase in case reports, commentaries and editorials, there has been no systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Establishing the evidence base for this apparent phenomenon which is of increasing concern to psychiatrists and people with schizophrenia is crucial prior to developing guidelines for diabetes screening and management.

We conducted a systematic review of the evidence for an association between diabetes and type of antipsychotic medication, and carried out a meta-analysis of the relative risk of diabetes in people with schizophrenia who were prescribed second-generation antipsychotics, compared with those who were prescribed first-generation antipsychotics.

Methods

Criteria for selecting studies

Abstracts were considered eligible for full manuscript data extraction if they fulfilled the following criteria:

-

(a) the design was a cross-sectional, case–control, cohort or controlled trial

-

(b) the study population included children or adults with schizophrenia or related psychotic disorders

-

(c) second-generation antipsychotics (defined in this study as clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone and quetiapine) were being compared with first-generation antipsychotics (listed in the British National Formulary (BNF)) 13

-

(d) measurement of diabetes as a primary or secondary outcome was included.

Studies were excluded according to the criteria shown in Fig. 1. Studies funded by pharmaceutical companies were included, and coded as such, whether fully or partially funded.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of systematic review.

Search strategy

Using established Cochrane Collaboration search strategies and definitions for schizophrenia, antipsychotics and diabetes mellitus, we searched the following electronic libraries: MEDLINE (1966 to September 2006); PsycINFO (1967 to September 2006); EMBASE (1980 to September 2006); International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970 to September 2006); CINAHL Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (1982 to September 2006); and Web of Knowledge (1981 to September 2006). The following search terms were used: ‘schizophrenia and related illnesses’, adapted from the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group schizophrenia search strategy; ‘antipsychotic’, including all first-generation antipsychotics in the BNF; 13 ‘diabetes mellitus’, amended from the Cochrane Collaboration Metabolic and Endocrine Disorder Group general diabetes search strategy (search strategy available from authors on request).

The proceedings of conferences during 2000–2005 on diabetes (American Diabetes Association, Diabetes UK, European Association for the Study of Diabetes, International Diabetes Federation) and psychiatry (American Psychiatric Association, Schizophrenia Research) were hand and electronically searched in the relevant sections.

The reference lists of included studies and reviews were searched for any additional studies. Although clozapine was first introduced in 1956 and withdrawn shortly after because of severe side-effects, there was a small risk of not detecting pre-1966 studies (when MEDLINE began), which was addressed by checking reference lists.

Corresponding authors and experts in the field were contacted for additional information on published and unpublished studies.

Data extraction

The abstracts of studies identified by electronic searches were examined by M.S. If unclear, the original article was retrieved, reviewed and discussed with co-investigators.

Data were extracted from papers selected for further review. Foreign papers were translated by doctors who were native speakers in that language.

Using a standardised data extraction sheet, we recorded and coded the following information (if available) from studies: country of origin; study design; setting; total sample size (and total number taking second-generation and first-generation antipsychotics); classification and method of assessment of schizophrenia; ascertainment of antipsychotic exposures; assessment and classification of outcome (diabetes); follow-up period; age; type of confounders adjusted; and source of funding. An attempt to retrieve missing data in the published article was made by contacting the author for correspondence on at least two occasions by email or letter.

Quality assessment

There is no consensus standardised method for the quality assessment of observational studies. We adapted the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson, Rennie, Moher, Becker, Sipe and Thacker14 and Strengthening of the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) 15 guidelines to assess and code the quality of the studies.

A study method was considered as high-quality if the following criteria were present:

-

(a) the design was prospective, including randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

-

(b) case definition for participants with schizophrenia was based on the past three editions of the ICD or the DSM

-

(c) the study included only patients who did not have diabetes at recruitment (baseline) of the sample

-

(d) recruitment of the sample was consecutive or random

-

(e) ascertainment of antipsychotic medication exposure used an objective technique, such as screening of electronic prescription databases

-

(f) ascertainment of diabetes mellitus as an outcome was based on accepted diagnostic criteria, such as the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 16 and the World Health Organization (WHO) 17

-

(g) temporality of an association between antipsychotic and diabetes was assessed with at least 1 year of follow-up reported

-

(h) the data were controlled for the six main independent risk factors for diabetes (body mass index, family history of diabetes (first-degree relatives), ethnicity, age, physical activity and socio-economic status).

All other descriptions, or lack of any description, were coded as low-quality.

Setting and funding status of the studies were recorded but not coded for quality as it was difficult to assess with confidence how this could have introduced a bias.

We did not summarise the quality of studies with a score as this approach has been criticised as allocating equal weight to different aspects of methodology. Reference Juni, Altman and Egger18

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data from studies of high quality were pooled using random effects inverse variance weighted meta-analysis Reference Woodward and Raton19 in Stata, version 9 for Windows. Where available, approximate relative risks (odds ratios or hazard ratios) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for diabetes, which compared second-generation antipsychotics with first-generation antipsychotics, were used from each study. Where results were given after different adjustments for confounding factors, the result for the largest confounding set was used. If only numbers with diabetes by drug type were available, these were first used to compute unadjusted odds ratios and corresponding 95% CIs for that study. Where no diabetes events occurred in any drug group, the study was excluded from the meta-analysis. Some studies gave separate results for different second-generation drugs but no overall result. In these cases, meta-analysis was used to create a pooled result, over all second-generation drugs, for that study only. This result was carried forward to the overall meta-analysis. The percentage of heterogeneity between studies not attributable to random noise was estimated using Higgins' I-squared statistic. Reference Woodward and Raton19

Results

The search strategy identified 1974 abstracts from which 73 full texts were selected for further extraction. Data extraction from full texts identified 14 studies that met the criteria for inclusion in the systematic review. A total of 11 studies had sufficient information to be included in the meta-analysis. The number of studies that were excluded from the review and meta-analysis are shown in Fig. 1. The studies included in the systematic review are described in the online Table DS1.

Of the 14 studies, 10 were based in a hospital setting, 1 was based in primary care and 3 comprised a mixed hospital and primary care setting. Seven studies used a health administration or health insurance database. Reference Sernyak, Leslie, Alarcon, Losonczy and Rosenheck8,Reference Lambert, Chou, Chang, Tafesse and Carson20–Reference Zhao, Tunis and Loosbrock25 Only 1 study used a database designed for conducting research. Reference Koro, Fedder, L'Italien, Weiss, Magder, Kreyenbuhl, Revicki and Buchanan26

The majority of study designs were either cross-sectional (n=4), retrospective cohort (n=4) or case–control (n=2) with only a handful using prospective design (n=3). The majority used consecutive or convenience sample selection, with two studies using random selection (Table DS1).

Nine (64.3%) studies used a classification system for schizophrenia (ICD, DSM–IV) but the majority were based on a clinical assessment with only one study using a research diagnostic interview, namely the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–III–R Reference Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon and First27 (Table DS1). The average age was 45.0 years (s.d.=7.7) (n=12 studies with age data).

Second-generation antipsychotics included in these studies were clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone and quetiapine, with clozapine studied on its own in four of the studies. Reference Hägg, Joelsson, Mjörndal, Spigset, Oja and Dahlqvist5,Reference Lund, Perry, Brooks and Arndt23,Reference Chae and Kang28,Reference Miller and Molla29 Although sulpiride is classified as a second-generation antipsychotic in one paper, Reference Cohen, Dekker, Peen and Gispen-de Wied30 it is classified as a first-generation in the BNF and therefore was excluded from our list of second-generation antipsychotics.

The diagnosis of diabetes mellitus was according to WHO 31 guidelines in 3 (21.4%) studies, Reference Hägg, Joelsson, Mjörndal, Spigset, Oja and Dahlqvist5,Reference Chae and Kang28,Reference Cohen, Dekker, Peen and Gispen-de Wied30 ICD–9 diagnosis in 5 (35.7%) studies, Reference Sernyak, Leslie, Alarcon, Losonczy and Rosenheck8,Reference Lambert, Chou, Chang, Tafesse and Carson20,Reference Lambert, Cunningham, Miller, Dalack and Hur21,Reference Lund, Perry, Brooks and Arndt23,Reference Zhao, Tunis and Loosbrock25 and ADA guidelines in 3 (21.4%) studies. Reference Miller and Molla29,Reference Kurt, Oral and Verimli32,Reference Lindenmayer, Czobor, Volavka, Citrome, Sheitman, McEvoy, Cooper, Chakos and Lieberman33 Most of the studies ensured that there was no evidence of diabetes prior to antipsychotic use but certain studies did not clearly differentiate between new and existing cases of diabetes. Reference Sernyak, Leslie, Alarcon, Losonczy and Rosenheck8,Reference Miller and Molla29,Reference Cohen, Dekker, Peen and Gispen-de Wied30 In addition, some studies used prescription of diabetes medication for diagnosis of diabetes. Reference Lambert, Chou, Chang, Tafesse and Carson20,Reference Lambert, Cunningham, Miller, Dalack and Hur21,Reference Lund, Perry, Brooks and Arndt23–Reference Koro, Fedder, L'Italien, Weiss, Magder, Kreyenbuhl, Revicki and Buchanan26

Excluding cross-sectional studies, follow-up periods ranged from 2 to 62 months and the median duration of follow-up from the start of the study was 12 months (interquartile range 2.6–16.8 months).

Most studies did not adjust for confounders in the methods or analysis. Studies also did not adjust for all risk factors for diabetes (Table DS1).

There were 7 studies funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Reference Lambert, Chou, Chang, Tafesse and Carson20–Reference Leslie and Rosenheck22,Reference Ollendorf, Joyce and Rucker24–Reference Koro, Fedder, L'Italien, Weiss, Magder, Kreyenbuhl, Revicki and Buchanan26,Reference Lindenmayer, Czobor, Volavka, Citrome, Sheitman, McEvoy, Cooper, Chakos and Lieberman33 One study was translated into English. Reference Kurt, Oral and Verimli32

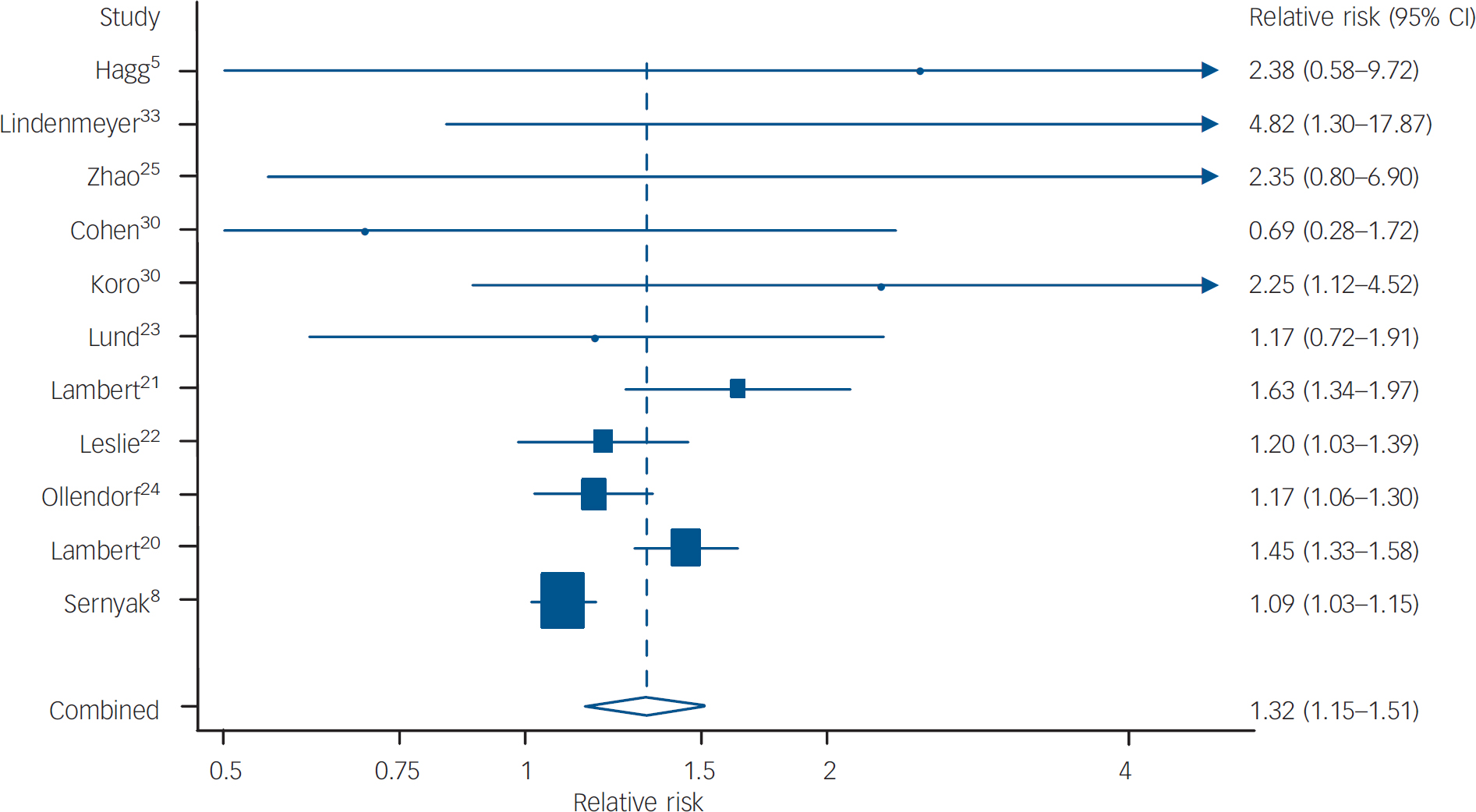

Our meta-analysis found an overall relative risk of a diagnosis of diabetes in people with schizophrenia prescribed a second-generation antipsychotic of 1.32 (95% CI 1.15–1.51) compared with being prescribed a first-generation antipsychotic (Fig. 2). The percentage of variability across studies that is attributable to heterogeneity rather than chance was 80% (95% CI 66–89) and the test for heterogeneity was highly significant (P<0.001). Both these results suggest that there is considerable variation between the studies.

Fig. 2 Forest plot of relative risks and 95% CIs for diabetes in patients on first-generation antipsychotics compared with second-generation antipsychotics. Estimates are at the centre of the boxes, which are drawn in proportion to the standard errors; lines show 95% CIs. Arrows denote censoring. The diamond shows the combined (pooled) estimate at its centre; its horizontal points lie at the 95% confidence limits for the combined estimate.

To explain this heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were carried out. Relative risks for separate second-generation drugs were as follows: risperidone 1.16 (95% CI 0.99–1.35; n=6 studies), quetiapine 1.28 (95% CI 1.14–1.45; n=3 studies), olanzapine 1.28 (95% CI 1.12–1.45; n=8 studies) and clozapine 1.39 (95% CI 1.24–1.55; n=7 studies).

Discussion

The study criteria for this systematic review identified 14 papers comparing the risk of having or developing diabetes while on second generation antipsychotics with first-generation antipsychotics in people with schizophrenia or related disorders. Eleven of these studies had sufficient data to pool. Meta-analysis found that second-generation antipsychotics were associated with a small increased relative risk for diabetes compared with first-generation antipsychotics. Reference Holt and Peveler34 Methodological limitations in nearly all the studies were evidenced by significant heterogeneity and this raises some difficulties in interpreting and comparing the studies.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our review are that the study is based on principles derived from the Cochrane Collaboration methods, such as an a priori protocol. In addition, established Cochrane Collaboration search strategies were adapted as well as hand searching of references of relevant papers, including non-English ones. Experts in the field were contacted for missing data and further information. We also conducted separate analyses comparing individual second-generation antipsychotics with first-generation antipsychotics to take account of the unequal distribution and potentially different diabetogenic potential of individual drugs.

A possible limitation of our review is that we used a narrow search strategy which may have excluded well-designed studies that focused on related outcomes other than diabetes, such as weight gain or insulin levels. Although cardiovascular risk factors other than diabetes mellitus such as abnormal lipid metabolism, blood pressure and obesity may also have a significant effect on the physical health of patients with schizophrenia, we chose to focus on diabetes and exclude metabolic syndrome. Although the diagnosis of diabetes is relatively uniform, no such consensus exists for metabolic syndrome. Reference Holt, Peveler and Byrne9 We also chose to exclude homoeostasis model assessment as an outcome as it is a research tool and its validity for predicting diabetes remains unclear. We excluded patients taking antipsychotics when the clinical indication was not clear. Reference Etminan, Streiner and Rochon35 We excluded studies of mixed psychiatric populations where subgroups of patients with schizophrenia who developed diabetes could not be distinguished. Reference Citrome, Jaffe, Levine, Allingham and Robinson36–Reference Spanarello, Beoni, Mina and Colotto41

This led to some studies that included people with schizophrenia being excluded. The rationale for including only schizophrenia and related illnesses, and excluding all other psychiatric illnesses or studies which did not state diagnosis, was the importance of considering schizophrenia as an independent risk factor for diabetes. Studies that did not compare a second-generation antipsychotic with a first-generation antipsychotic, but instead to another second-generation antipsychotic or placebo were excluded. Reference Brown and Estoup42–Reference Meyer45 We included all second-generation antipsychotics but there were no studies that met our eligibility criteria for the more recent drugs such as ziprasidone, amisulpride and aripiprazole, which have been suggested to be less diabetogenic in some case reports. Reference Ananth, Parameswaran and Gunatilake46,Reference Mackin, Watkinson and Young47 Future studies comparing their diabetogenic profiles are awaited.

Quality of studies

We found that the average duration of studies was around 12 months with three studies having a follow up of only 3 months or less. It could be that these studies did not follow up their patients for long enough, perhaps several years, to capture the long-term risk for diabetes and this may have led to an underestimation of our findings. However, there is also some evidence that the diabetogenic effects are rapid in onset – within the first few months. Reference Jin, Meyer and Jeste48 It is possible that there may be several glucose-metabolism-altering mechanisms, a short- and a long-term process, and studies with repeated measurements over several years could help to elucidate the diabetogenic patterns.

Most studies included in this review were retrospective or pharmacoepidemiological using large databases. Limitations in analysing data from such studies, mainly due to the quality of clinical data recorded, exist. Database studies do not rely on a standardised method of diagnosing diabetes mellitus. Random blood glucose measures were often used, highlighting the difficulty of obtaining fasting blood samples from this patient group. Furthermore, utilisation of established diagnostic guidelines for diabetes such as those provided by the WHO 17 or ADA 16 was inconsistent. Prescription of hypoglycaemic medication as a method of diagnosis may exclude patients receiving non-pharmacological treatment for diabetes such as those on diet alone. It may also include some people receiving metformin for other indications such as polycystic ovarian syndrome. Little evidence existed that the diagnosis of diabetes in databases was reliable or valid. The date of the first listed claim may not represent the actual date of onset of diabetes as the diagnosis may have been previously made but recorded elsewhere.

The techniques and methods used to diagnose schizophrenia cannot be inferred accurately from the databases. We observed that not all antipsychotics were included in the databases. This may be a reflection of the country where the study was undertaken and the availability of, and preference for, one type of antipsychotic over another. Many of the databases were of specific populations and mainly in the USA, which may limit their generalisability to other populations. In addition, a number of studies had only a few weeks or months of observation which may have captured those individuals who have rapid weight gain but which may be too short a time to identify later onset of diabetes.

Association between antipsychotics and diabetes

The first observation of an association between antipsychotics and diabetes occurred over 50 years ago, but renewed interest in this link has developed with second-generation antipsychotics in the past decade. Second-generation antipsychotics have been shown to reduce extrapyramidal side-effects and are beneficial to many patients. Reference Geddes, Freemantle, Harrison and Bebbington49 However, the concerns that second-generation antipsychotics may also increase the risk of metabolic dysregulation must also be carefully considered.

As the majority of studies were cross-sectional or retrospective cohort in design, it is not possible to determine the direction of the association between second-generation antipsychotics and diabetes. Our review highlights that most studies were limited in quality with none of the studies fulfilling all of the quality criteria; five studies had four or fewer quality criteria (Table DS1). Any association detected in this review is likely to be significantly biased. The possibility of residual confounding also cannot be dismissed. One residual confounder not reported in any of the studies was whether an increased amount of screening occurred in those on second-generation antipsychotics compared with first-generation antipsychotics, owing to greater clinical awareness. This is important because of the high prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes in people with schizophrenia, among whom as many as 75% of cases of diabetes may be missed. Reference Subramaniam, Chong and Pek50

Our review found that second-generation antipsychotics were associated with a 30% increased risk of diabetes compared with first-generation antipsychotics in people with schizophrenia – this is probably a biased observation Reference Lindenmayer, Czobor, Volavka, Citrome, Sheitman, McEvoy, Cooper, Chakos and Lieberman33,Reference Hill51 with the true association probably being smaller. This review was unable to find sufficient evidence to differentiate the risk associated with individual antipsychotics, nor did the studies we identified help shed any light on causal mechanisms. Our review emphasises that, to date, the evidence is very poor and should not be used alone as a guideline for or switching antipsychotic medications or implementing diabetes screening and management protocols for schizophrenia until further evidence comes to light.

In epidemiological terms, a relative risk of less than 2 is considered low, whereas a relative risk of greater than 3 is considered high. Reference Hill51 This is an important clinical issue to consider when treating patients with antipsychotic medication. Importantly, clinicians should implement protocols for identifying physical illnesses, in particular diabetes, in people with schizophrenic illnesses, while also reviewing the rationale and dosage of prescribing antipsychotic medication both in terms of treatment of psychotic symptoms and risk of diabetes. Our review has identified the key confounders and methodological issues that need to be considered in evaluating the association between diabetes and antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia. There also remains an urgent need for continuing to identify and understand the biological pathways and increase the epidemiological evidence base for diabetes in schizophrenia. In particular, randomised controlled trials comparing first- and second-generation drugs should consider the implications of their study's power to detect differences in onset of diabetes as an adverse event, bearing in mind these events are likely to be rare.

Acknowledgements

There was no funding for this study. We would like to thank Hugh McGuire (Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London) and Dr Alex Mitchell (Leicester) respectively for help with the search strategy, and Dr Zerrin Atakan (Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London), Dr Carmine Pariante (Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London), and Dr Smith for translation of articles written in Turkish, Italian and Mandarin respectively.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.