Introduction

Insofar as there has been an academic focus on the transformations associated with the financialization that took place from the 1980s, primarily at the macroeconomic level, corporate financialization is usually seen as a range of realignment to the external power of shareholders. Chandlerian organization would have been forced to adapt to exogenous changes. As Davis Kim points out, the financialization of the whole economy “shapes social institutions in fundamental ways […] financial markets [would] have favored disaggregation of the corporation.”Footnote 1 The main contributions on corporate financialization “consider the impact of the stock market’s increasing demands for financial returns on corporate behavior and performance.”Footnote 2 A new type of shareholder capitalism would have substituted the logic of “downsize to distribute” for that of “retain-and-reinvest,”Footnote 3 and hence structure a new organizational model: the post-Chandlerian enterprise.Footnote 4 This necessitated a battery of financial indicators and budgetary controls as channels to introduce short-term financial metrics.Footnote 5

Financialization has become a hegemonic concept in management, business history, and economic literature, especially since the subprime financial crisis.Footnote 6 There are many facets to this phenomenon, and this article concentrates on the internalist approach.Footnote 7 Corporate financialization has been defined as a rise of financial actors and instruments within organizations, along with a proliferation in accounting and budgetary controls.Footnote 8 Economic sociologists and political economists have focused on the underlying institutional conditions, such as deregulation,Footnote 9 global capital instability,Footnote 10 or the role of financial instrumentsFootnote 11 to explain the broader financialization of the economy.Footnote 12 In line with Adam Goldstein and Neil Fligstein,Footnote 13 this article traces corporate financialization not only as an adaptation to external evolution but also as a vertical integration process and with changes in the organizational model of the firms.

The most historically and theoretically successful conceptualization of the corporate financialization is that of Neil Fligstein. He describes this phenomenon:

[Corporate financialization is] the use of financial tools to evaluate product lines and divisions. The multidivisional form became the accepted organizational structure and control was achieved by decentralizing decision-making while paying close attention to financial performance. Product lines or divisions that did not meet corporate expectations for growth or earnings were divested […] [and the firm] focused on the corporation as a collection of assets that could and should be manipulated to increase short-run profit. Footnote 14

This article addresses the organizational conditions that underpinned the emergence of this conception of control. This article argues that the spectacular transformations leading up to corporate finance maximization first appeared in France during the 1960s and 1970s, and that large multidivisional companies were not always the “victims” of external financialization; they in fact contributed to its development and, to a certain extent, they were in control.

This article is in line with the teachings derived from the Chandlerian model, which, since the beginning of the twentieth century, has highlighted the role of large companies in macroeconomic developments. While their role in globalization has been emphasized, there has been little or no research in relation to the dynamics of financialization, which is of equal weight in the modern economy.Footnote 15 It is necessary to quickly review the financial elements of the Chandlerian model so as to connect Chandlerian and Fligsteinian patterns of structural and managerial innovations in large companies.

With the capital amassed since the second Industrial Revolution at the end of the nineteenth century, large companies based their success on their ability to use economies of scale and synergies, building large organizational structures expected to demonstrate a certain efficiency to optimize resources. This development led managers to play a key role in using management tools to organize this efficiency. Pioneering companies rapidly became monopolies or oligopolies in their sector and acted as a pole of attraction for the rest of the economy during the twentieth century.Footnote 16

According to Chandler, the financial issue occupies a central place in these transformations. He points out that at the beginning of the twentieth century, “many of the later mergers were engineered and concluded by Wall Street financiers and speculators, eager to profit from the promoter’s commissions, capital dilution and other financial transactions.”Footnote 17 Before multidivisional management could be structured, and before divisional performance measures could be refined, major challenges facing companies had to be resolved: the obtention of consistent and accurate cost, production, and revenue data, including the standardization of accounting systems.Footnote 18

The emergence of the Chandlerian enterprise was linked to the creation of financial tools. Therefore, it is not surprising that in developing his dynamics of financialization, Neil Fligstein carefully read Chandler’s work, to which he explicitly pays tribute.Footnote 19 Going beyond Chandler’s functionalist approach, Fligstein formulated an institutionalist account of the transformation of corporate control.Footnote 20

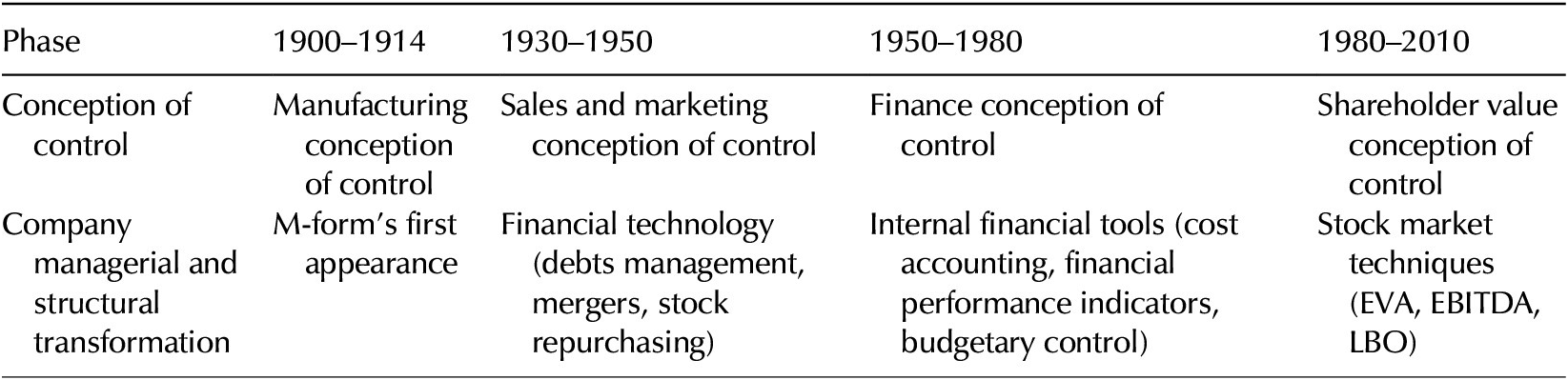

In the postwar period, the financial conception of control evolved in the United States throughout the manufacturing, sales, and marketing conception of control. Major internal financial tools were used starting in the 1950s, especially by managers trained in finance and accounting, who then developed the metrics that paid close attention to a firm’s financial performance. This was related to the growth of large companies and the spread of the multidivisional form: “Finance executives reduced the information problem to a measurement of the rate of return earned by each product line.”Footnote 21 During the 1960s, with the formation of conglomerates, “all the financial forms of reorganization including mergers, divestitures, leveraged buyouts, the accumulation of debt, and stock repurchasing were invented or perfected.”Footnote 22 Thus, the development of the finance conception of corporate control is rooted in the development of the Chandlerian enterprise.Footnote 23 Table 1 show the relationship of the conception of control and managerial structures of companies.

Table 1. Relation between Fligstein’s conceptions of control and the managerial structure of companies, 1900–2010

The development of the multidivisional company has been a long process that has undergone several transitions. The transformations, especially in Europe and France, have been more progressive than sometimes reported: “The finance conception of control therefore already viewed the firm in primarily financial terms. […] The shift from financial conception of control to the shareholder value conception of control is a subtle one.”Footnote 24

This means that uniting the Chandlerian and Fligsteinian models in the same dialogue aids an understanding of the continuous managerial transformations that took place in the financialization of large companies. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the creation of large industrial groups during the 1960s in France may have provided the organizational basis for subsequent financialization. Financial strategies and metrics cannot emerge in companies without some prior development. This article describes some of the financial conditions for the development of the Chandlerian form in France and the organizational conditions for corporate financialization.

The development of finance in Europe has followed different paths from the United States.

While the American industrial structure is firmly in the grasp of the shareholder value conception of control, the rest of the world has steadfastly resisted importing it, [the shareholder value conception] has not emerged in many other advanced capitalist countries, in large part because of pre-existing sets of institutional arrangements between states and economic elites.Footnote 25

To understand the rise of the finance conception of control, it is therefore necessary to describe the specificities of the French institutional arrangements and economic structures that cannot be replicated to US dynamics. The institutional conditions of corporate finance emerged in France in the 1960s and 1970s, which in turn shaped the conditions for the rise of this financial conception of control.

The case of Peugeot Société Anonyme (PSA) is relevant to these early changes because the automotive sector was the archetype for the Fordist model. Eminent French business historians have shown considerable interest in Peugeot and Renault, the two main French manufacturers. Although the industrial transformation of these companies between the 1950s and the 1970s has been thoroughly examined,Footnote 26 Peugeot’s financial dimension has largely been ignored.Footnote 27 Furthermore, the prism of financialization is absent from the literature on large French automotive companies. Thus, an improved understanding of the endogenous aspects of financialization in the automotive industry remains a challenging area of research.Footnote 28

Using an in-depth case study, this article explains an episode in the 1960s when organizational bases were created for further financialization within PSA. My specific focus is on a crucial step in 1965: a financial reorganization brought all the various activities under the control of a multilevel structure of holding companies.

This analysis draws on both written and oral sources. The written sources include archival records from PSA’s collections and public institutions, such as the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, as well as documents from personal archives. In terms of oral sources, I conducted semistructured interviews, one of which is quoted in this article. The interviewee is a former director who had a major financial role in PSA, and he was asked about his understanding of the issues and choices made by the company over time.

This article demonstrates that the institutional and endogenous factors leading to the major financial restructuring of the Peugeot family business in 1965 dovetails neatly with the evolving French economy and politics of the 1960s, which contrasts with the classical narrative on corporate financialization. This article argues that this transformation was a pivotal episode in dealing with Chandlerian stakes, which paved the way for further corporate financialization.

This article starts by presenting the industrial and financial contexts of the 1960s. The first section provides information on state-driven mergers and acquisitions (M&A) that led to the rise of the Chandlerian multidivisional form. This changeover period saw the development of the French stock market capitalization for large businesses and the rise of financial companies offering their expertise in the formation of the French National Champion initiative. It explains that the French-style financialization process began at this time as a corollary of the Chandlerian model. The following section undertakes the significant financial issues caused by the push to form partnerships. In presenting the financial reorganization in 1965, this article explains the features of this financial structure. It discusses why all of Peugeot’s industrial activities were placed under the control of several holding companies, and how the decisions made included multiple industrial and financial rationales, activities, and structures. The third section addresses the main financial consequences of this reorganization, which put financial constraints on the industrial side of the business. This led management to incorporate more financial terms in their communication and to develop a centralized financial control system for maximizing short-term profits and driving up the stock price. Finally, this new multilevel holding structure allowed subsidiaries to be considered as literal independent assets that constituted the basis for subsequent financialized management within PSA.

Peugeot during the Changing 1960s: M&A Movement, Spread of the Large Chandlerian Enterprise, and the First French-Style Financialization

The details of the European path toward corporate financialization can be summarized as follows. State-company relations in Western Europe developed over a longer period and remained more stable than the same relations in the United States. Moreover, the French case can be considered as the archetype of this interpenetration of economic and administrative elites. French industrial policy was directed toward the creation of what the state deemed as national champions. As a result, French companies tended to be relatively large, vertically integrated, and only slightly diversified.Footnote 29 The 1960s was a disruptive changeover period for large French companies, enriching the general narrative about earlier stages of corporate financialization. The French state encouraged a move toward growth and vertical integration, disseminating the multidivisional model to large French companies. This went hand in hand with strengthening the Chandlerian form and developing French financial markets, management tools, and financial indicators.

The Context of 1960s French Industry: The Move Toward Vertical Integration as Orchestrated by the State and the Spread of the Multidivisional Form

The 1960s saw contrasting transformations, with multiple factors leading to the institutionalization of finance within French industrial groups. From the 1950s onward, there were clear signs that the French economy was once again embracing the international scene.Footnote 30 French employers wanted some corporate structural reform linked to European harmonization. After 1958, the Gaullist stateFootnote 31 gave impetus to reforms to encourage the rationalization of industry. Indeed, at the center of state concerns was that large French companies exported less, were less competitive, and generally smaller than their European counterparts. The Gaullist state’s industrial and financial policies set out to stimulate the “competitiveness” of its companies by encouraging the success of national champions, which shaped the specific institutional context of French capitalism.Footnote 32 The state used two instruments to encourage this modernization: planning policy and industrial policy.

A major wave of M&As followed and constituted a decisive factor in the development of the large Chandlerian enterprise, which is concomitant with certain financial structures and tools that took a central place in large French companies. The number of mergers between French companies increased dramatically in the 1960s, as seen by 1,850 M&As as compared to 843 in the previous decade.Footnote 33 For instance, of the 33 car companies that survived the war, only 16 were active in 1956, and this concentration continued.Footnote 34 Most large French groups were formed or consolidated between 1958 and 1965. These mergers generated powerful groups including Saint-Gobain-Pont-à-Mousson, Thomson, CGE, Rhône-Poulenc, ATO, Creusot-Loire, Babcock-Five, SNIAS, Le Nickel, and Peugeot; they became the new face of French capitalism.

This “spirit of modernization” stems from the relatively widespread thinking among the economic elites of that period. Business organization advisers’ concern for efficiency was spreading. Consulting firms, especially McKinsey in the United States and Cegos in France, were essential in transforming companies as they spread the multidivisional form across Europe during the 1960s.Footnote 35 Because the institutional context was different from US companies, European companies were less attracted to diversification insofar as their close relationships with banks and the state mitigated their need to compensate for the risks they encountered. Nevertheless, the multidivisional form (M-form) developed in Western Europe. By 1970, 42 percent of French industrial companies were M-form.Footnote 36

Clearly, the 1960s was propitious for the formation of large groups, the spread of the M-form, and the structuring of management. These are embedded in the French hybrid model, which is marked by limited diversification; multi-divisionalization; an expanded system of financial holdings; and intertwined economic elites, powerful family businesses, political elites, and managerial executives.Footnote 37

A First Step to French-Style Financialization: A Corollary of the Chandlerian Model

In this context, a key challenge was financing the growth of industrial companies. The Peugeot family business found itself woven into these shifts in financing at the macroeconomic and microeconomic levels as the state orchestrated economic rationalization of the industry, which had its corollary in the banking and financial industries.

Starting in 1958, under the Treasury’s supervision, there was a decline in how companies were traditionally financed alongside the development of market financing.Footnote 38 In 1964, a report challenged the fundamental principles of interventionist policy,Footnote 39 and the subsequent reorganization of the French banking system led to an increase in short-term liquid savings, which helped liquefy the French economy. Between 1965 and 1974, investments financed by the banking system rose from 36 percent to 60 percent from financing through Treasury channels.Footnote 40

The Gaullist government promoted and supported this shift in financing arrangements. The Debré-Haberer reform contained a series of decrees issued in 1966 and 1967. First, like companies in the industrial sector, banks were encouraged to merge. This led to the formation of several large banking and financial groups. Second, there was attenuation in how the two types of business were partitioned. This was a major step toward the creation of French financial markets, and indeed European financial markets.Footnote 41 At the dawn of the 1960s, growth in the Paris financial center took shape: the financial newspaper Les Échos stated in 1965 that “the government intends to solve the problem of investments through a cautious revival of the financial market.”Footnote 42 And the headline of an investment financing insert was: “Recourse to the financial market… is imperative. It is therefore essential to provide new resources, through recourse to capital increases, and therefore to the financial market.”Footnote 43

Several converging indicators show the influence of shareholders on large companies and their recourse to the French financial market. The ratio of market capitalization to gross domestic product rose to almost 40 percent in 1962 before dropping to 5 percent in 1982.Footnote 44 Therefore, if one considers the importance of dividends through the share price/dividend ratio, a similar development appears: a sharp rise in 1955 to a peak in 1962 (more than 60 percent), followed by a decline until 1984. The share of dividends in company earnings was over 60 percent in 1975, falling to below 5 percent in 1989.Footnote 45

During the 1960s and 1970s, the industrial and banking sectors were interrelated, and the technical interventions of the large investment banks were crucial in all M&A transactions.Footnote 46 In France, the Lazard Bank played a particularly important role in disseminating the concepts of corporate finance to large industrial groups.Footnote 47 Indeed, many industrial groups sought to integrate banks and financial companies by buying them out.Footnote 48 This led to a specific form of French capitalism in which the central role of the state, combined with crossholdings of banks and industries, shaped the French “financial core” model.Footnote 49

The interdependency of large companies and banks gave rise to a first step toward further corporate financialization. The new injection of power into the large banks and the important operations on the Parisian financial market from the expanding industrial groups converged to create the first stage of a French-style financialization.Footnote 50

Financial Holding Structure: The Condition for Industrial Development

When observing the financial stakes inherent to the development of the Chandlerian enterprise, one understands that the creation of large industrial groups in 1960s France could have constituted the organizational basis for a subsequent corporate financialization. In this respect, the 1960s in France was a time of contrast and transition, which can be enlightened by studying the issues of the Peugeot business.

In 1962, Peugeot’s senior management team created a committee from the three industrial branches (Automobiles, Bicycles, and Steel and Tools), with major players involved in the reorganization.Footnote 51 This committee included Wilfrid Baumgartner, who was a former inspector of Finance, former governor of the Banque de France, and recently appointed minister of the Economy and Finance. The presence of this senior state financial official, according to Michel Margairaz, reflects the “rise in power of the group of finance inspectors […] their dissemination throughout the economy through pantouflages, the growing importance in the twentieth century, of the so-called ‘financial’ sphere.”Footnote 52 Thus, whether because of the economy or the profile of the elites that influenced the reorganization, Peugeot’s development was intertwined with industrial and financial stakes.

Industrial, Organizational, and Financial Challenges Intertwined

Peugeot’s financial reorganization was embedded in the size challenge of the Chandlerian enterprise and driven by engineers and commercial managers. Starting in the 1950s, production volumes increased exponentially. Automobiles PeugeotFootnote 53 manufactured 100,000 vehicles in 1950; 200,000 in 1960; and more than 500,000 in 1970.Footnote 54 Until 1965, a triumvirate of Jean-Pierre Peugeot, Maurice Jordan, and Paul Perrin ran the company.Footnote 55 These engineering and commercial experts broadened the company’s industrial scope, which led to huge financial changes. Annual investments increased continuously in the first part of the decade, rising from F 76 million in 1960 to F 180 million in 1964, an increase of 137 percent. Nevertheless, production capacity reached saturation and Automobiles Peugeot alone could not carry the high expected levels of French automotive progression.Footnote 56 To sustain this increase in volume, senior managers had to consider restructuring the company’s capital.

Consequently, to remain competitive, executives had to seek out opportunities for collaboration. At the end of the 1950s, Maurice Jordan, as well as the other automotive executives, were aware of the need to change the industrial scope. He approached Citroën’s main shareholder, Michelin. Starting in 1955, Jean-Pierre Peugeot and Maurice Jordan met with the grandson of Édouard Michelin, the new CEO of the Michelin group, once a year for lunch.Footnote 57 The following quote from a former senior manager sheds light on what it must have felt like inside the company:

I was wondering if this [the 1965 reform of the group structure] wasn’t just an easier way to prepare for external developments by splitting Peugeot Automotives, Cycles, and Steel and Tools, and keeping control of them. Were we already thinking about grouping companies together in the automotive sector? 1966 was when the agreement was made with Renault, but there was no capital agreement, so there were limitations.Footnote 58

And this quote in 1974 from Le Figaro Économie, a leading French daily business newspaper, illustrates that size of Peugeot was both of public and official concern:

Peugeot, despite the quality and prudence of its management […] would not have been able to face the coming struggles because of its small size. It had neither mass production […], nor specialization compared to BMW and Mercedes, for example. Sooner or later, the Sochaux firm would have had to find a partner. It is better that it is a French partner.Footnote 59

The company had been accumulating profits and financial reserves since the 1950s. Nevertheless, the relative financial autonomy of the Peugeot family business was to become a brake on its industrial development. Starting at the end of the 1940s, the various companies in the business organized regular increases in capital through bond issues and loans from banks. In 1960, Automobiles Peugeot also obtained F 1,050 million in credit from a banking group run by Société Générale. This considerable loan, as well as the Swap Execution Facility forms and other favorable reports prepared by financial companies in the 1950s and 1960s, indicates the financial credibility of the business.Footnote 60

The growth outlook was such that external financing was developed in parallel with the strengthening of equity capital. The CEO at the time, Maurice Jordan, had long implemented a policy of hoarding cash. These decisions gave a solid financial structure to the balance sheet: the value of shareholders’ equity increased by 55 percent,Footnote 61 from F 470 million to F 726.6 million between 1960 and 1964.Footnote 62 Profits increased only slightly; net operating value and fixed asset value increased more substantially, as did share capital, reserves, and retained earnings.

Nevertheless, if the business enjoyed a high level of credibility at the beginning of the 1960s, it did not bring the various companies in the business together as a whole. Although they could obtain financing independently, no one investor could provide support to all the companies. For Peugeot to carry on a small provincial business would have meant being marginalized at a time when the importance of the automotive sector was increasing, as was the growth in volumes and prospects for large groups.

Creating a new financial structure was a necessary response to having fragmented companies. At the beginning of the 1950s, the business consisted of fifty companies, and their interrelations increased over time through various activities. The result was a confusing and complex overall structure understood only by a few senior managers.Footnote 63 Subsidiaries that had to be merged with other companies, such as Automobiles Peugeot, required independent accounting systems. Indeed, a decision by the family during the 1920s led to the business being run in relative industrial and financial isolation.Footnote 64 A key factor for this reorganization was to end the seclusion; as long as the family exclusively and internally managed the capital of the various industrial companies, there was little need for formalization. Now that capital mergers were envisaged for the automotive sector, a more formal split was considered necessary.

Ultimately, restructuring was a way to gain broader access to the money market and banking institutions. It was imperative to present an image to the corporate world of having clear legal, financial, and accounting structures. To summarize the various issues raised by the senior managers, I refer to a report by François Gautier to the board of directors of Automobiles Peugeot in 1965:

The structure, which is conveniently but inaccurately referred to as “group,” is the outcome of historical circumstances. It has not been strictly remodeled when required, and has gradually become too complicated, too cluttered and too expensive because of excessive tax costs. Moreover, the diversification that has been its strength, has at other times prevented the public from having an accurate view of the whole, and makes it virtually impossible to draw up consolidated balance sheets, despite their usefulness to us. Finally, this type of architecture is ill-suited to the times we are entering, with the foreseeable prospects of increased national and international competition, and the probable need for regrouping and concentration.Footnote 65

This discourse, which was presented to the shareholders at the annual general meeting in June 1965, constitutes a fundamental pillar of the institutionalization taking place at that time. The excerpt encapsulates the various issues and defines the reality facing the new organization. It refers to a discursive strategy in a context in which the effective action perceived by the leading members of the business involves a break with the past.Footnote 66 This message suggests that the executive senior managers and family members were a unified group, underpinned by these new legal and financial structures. The overriding issues of size and concentration put the company on the path to capital restructuring and, more generally, financial reorganization.

While this development was envisaged as an opportunity for the groups to merge, a further justification was to build a robust “industrial holding company” in a bid to promote more advantageous negotiations with other manufacturers during ongoing mergers:

Mr. Peugeot and Mr. Jordan, and all the directors, remained convinced that the future would require some form of consolidation (association, merger…) This reflection led us, among other things, to note that controlling only 30 to 35 percent (of AP’s capital) would disadvantage us in any negotiation, even if the dual voting rule for shares registered for more than two years guaranteed complete security.Footnote 67

With Peugeot’s commitment to industrial development, the senior managers had to open up capital to outside investors. To attract major investors and appear to the state and industrial competitors as a large company, it was necessary to create a single capital base for the business. Future negotiations were supported by the publication of consolidated accounts, which acted as a clear indication of greater control over the whole business, like with other French industrial groups.Footnote 68 These elements equated to the constitution of a large multidivisional group, in line with the model used by competitors.Footnote 69

The final reason for the financial reorganization came from the fifty family shareholders. The group’s economic center was shifting rapidly toward the automotive sector, which was causing disruption to the family dynamics. Members of different family branches owned assets in various activities that had developed separately since the nineteenth century. Automobiles Peugeot, headed by Jean-Pierre Peugeot, Maurice Jordan, and François Gautier, was by far the main source of dividends. Jean-Pierre, who was advancing in age, anticipated the conflicts in managing the intergenerational handover, and tried to preserve unity and concentration of assets.Footnote 70 Family dynasties are particularly fragile, and conflicts over succession may significantly jeopardize their continuity.Footnote 71

The New Financial Overall Structure for the Multidivisional Industrial Company

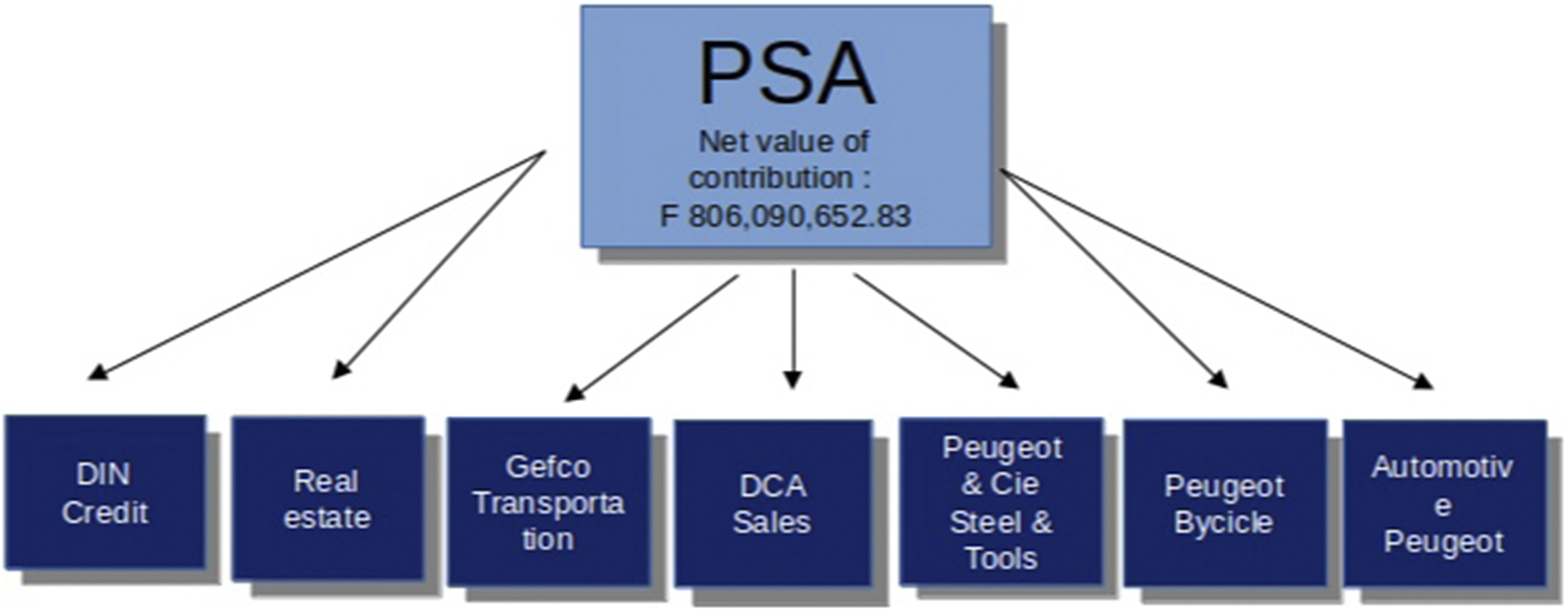

Automotive companies were now keen to set up financial companies specialized in national and international financial management.Footnote 72 Because of the various issues affecting Peugeot, a financially powerful company at the head of the business would seem better for negotiating. This major “structural reform,” a term used by interviewees from the time, involved the legal and financial sides of the business headed by Paul Perrin. To exercise its new holding function, Automobiles Peugeot divested itself of its industrial and commercial activities by transferring them to Indenor, a financial subsidiary of the company. This combined various industrial activities, which had been acquired over time, and were specialized in the manufacture of diesel engines. The new structure took the name Peugeot Société Anonyme; it controlled the “leading companies,” which in turn controlled all the subsidiaries, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1. New structure: Companies under the control of PSA and the new top holding company

Note: The different companies are the main subsidiaries of PSA holding in 1966 (after its reorganization). In addition to the three main sectors (Automotive, Bicycles, Steel and Tools), there were credit, sales, vehicle transportation, and real estate. It is important to mention smaller industrial firms (Compagnie Industrielle des Mécaniques, Union Centrale de Participations Métallurgiques et Industrielles, Société pour l’Équipement Électrique des Véhicules); mortgage subsidiaries (Crédit Mobilier Industriel, Sovac); and dealers (Société Nouvelle des Garages de Champagne; Grand Garage de la place Saint-Augustin; Société Industrielle Automobile du Languedoc de Lorraine, de Normandie, de l’Ouest, de Provence). Report presenting the structural reform to the general extraordinary assembly of shareholders in October 1965, Entry number: 4-WZ-24 09, BNF.

The establishment of PSA grouped the assets of the various industrial, commercial, and financial assets within a unique financial center. PSA quickly grew to a workforce of fifty; by 1972, it held a share capital of F 420,000,000.Footnote 73 Moreover, by listing the now powerful financial company PSA as a single entity, the new corporation found the conditions for accessing the financial market much more attractive (see figure 2).

Figure 2. First listed shared created by Peugeot SA, 1965

Note: PI2016ECR-08469, PSA Archives.

The main industrial company had become a financial holding company. As the head of the group, PSA controlled all of the subsidiaries and consolidated the financial statements. And a prestigious new head office in Paris for senior managers cemented the image of a powerful group. PSA was henceforth a mirror for Peugeot’s industrial activities to the financial community. The board’s position was elevated, which indicated that senior managers would be farther from operational decisions. This was an essential condition of the corporate financialization process.

This new structure closely corresponds to Chandler’s M-form. It was the outcome of one hundred years of industrial development, which resulted in several family-held companies developing different products yet remaining within the same family structure. This business could only be decentralized into “autonomous divisions,” specialized according to product lines. By 1965, each division had its own management and functional structure and was operating as an independent company. PSA now controlled this agglomeration of product lines within a single entity.

Starting in 1965, the PSA’s board of directors controlled management of divisions, which were actually independent companies. I argue that this was a factor in the development of financial tools used to manage distinct, although related, industrial activities according to the centralized interests of the shareholders. The first step in refining divisional performance measures was to address the major challenges facing the business: developing consistent and accurate data on costs, production, and revenues.Footnote 74 As this article presents in the third section, the business’s reorganization had an immediate corollary with the development of a centralized system of financial controls overseen by PSA’s senior managers.

Control of the Financial Edifice: A Cascade of Holdings to Manage the Business Portfolio

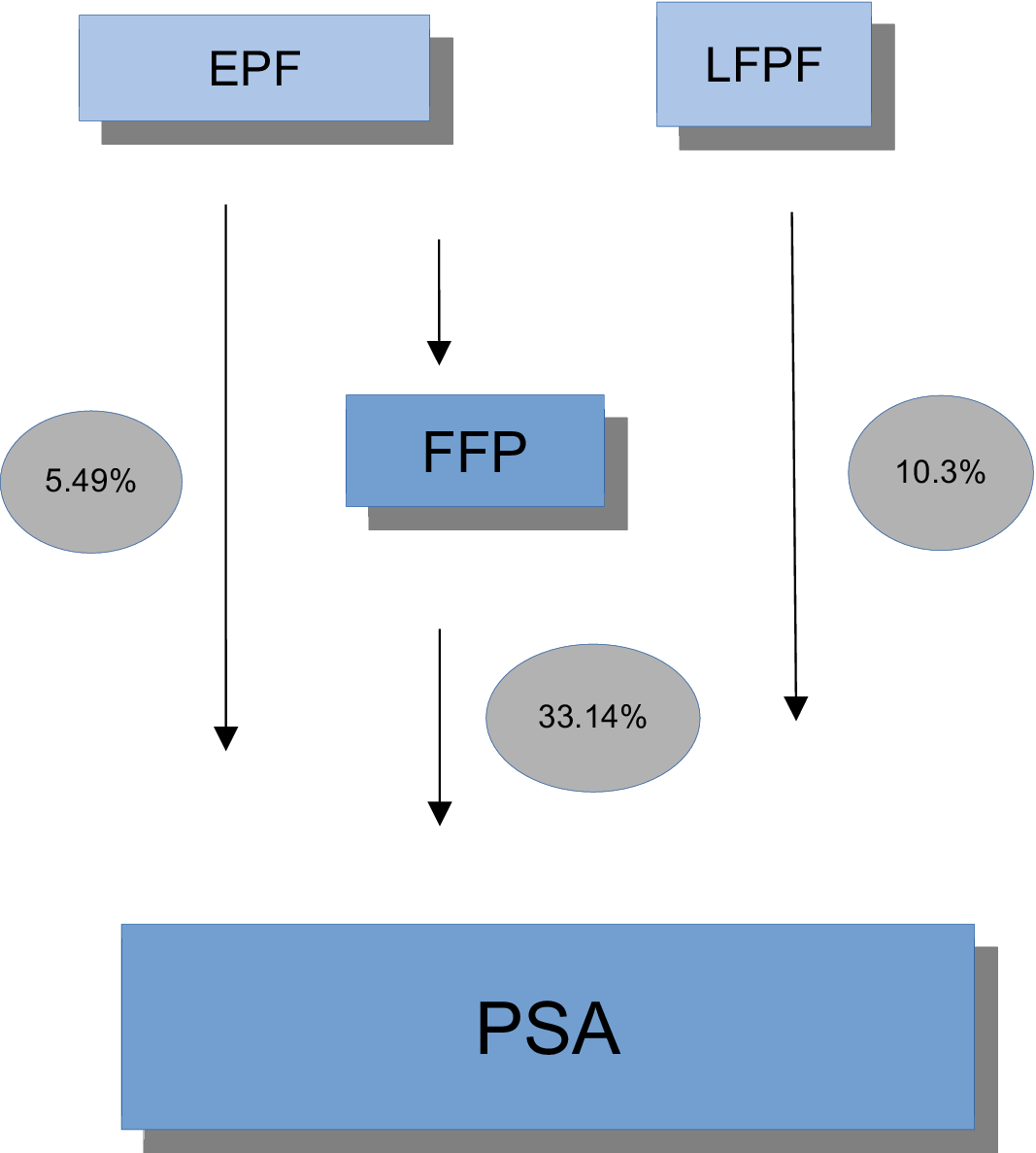

The company Établissements Peugeot Frères (EPF), created in 1810, was a holding company by the end of the nineteenth century. Les Fils de Peugeot Frères (LFPF) was an older family-holding company. The family created the Foncière, Financière et de Participations (FFP) in 1929 as a holding company to secure family control of the capital.

The new CEO was in an ideal position to monitor the income generated and the level of capital control required for the whole group. The main function of the holding company was to facilitate management’s control and unity. Here, EPF allowed several companies to concentrate control with a minimum of investment. For example, EPF owned 50 percent of FFP, which itself held 50 percent of PSA’s capital, thus allowing EPF to control the majority of PSA while holding only a quarter of its capital. In general, each time a holding company is added to the cascade, the proportion of capital required for control can be halved.Footnote 75

The use of holding companies to concentrate control involves more sophisticated financial management, which is both legally simpler and less costly than other means, such as mergers or consolidation. It allows for the collection of dividends at low tax cost and the repurchase of the shares issued. Controlling the subsidiaries in a group was not only financially advantageous but also beneficial to the family’s assets and economic power. With Peugeot, it established family solidarity by centralizing the interests within a single structure: FFP, as shown in figure 3:Footnote 76

Figure 3. The financial control structure of the group, 1971

Note: Total control of PSA by the family group in 1971: 50.64 percent, which includes 48.97 percent direct control by the family group, and 1.67 percent indirect control by related shareholders. Report by Thierry Armangaud on the evolution of family control. Armangaud was a financial manager from 1960 to 1990 and a family-holdings manager starting in the 2000s. Thierry Armangaud, personal archives.

The reorganization was necessary because without FFP’s independence from the industrial group (i.e., without a clear organizational separation between operational and financial management), the group’s development would not have been possible.

The PSA group was now in effect controlled by several holding companies. At the top were EPF and LFPF, two exclusively family-owned concerns. After World War I, FFP developed its active role in the financial market. These three holding companies were all managed by the largest family shareholders, guaranteeing that the family had direct and indirect control of the capital. The main function of FFP, in addition to ensuring the family’s management of the business, was to act as the interface between the group and the market. Indeed, any new financing (i.e., internal investment or external development) could take the form of an equity contribution, a loan, or the raising of new shares.

The fundamental financial challenge was to support the group’s new development while preserving family control of the capital. Each new freeing up of capital meant a dilution of the family share, which was why an unlisted family company operated purely as a financial holding company. This made it possible to balance the two goals: expansion and family control. The larger the loan, the greater the need for financial credibility. Peugeot’s name, success, and image was now formally through FFP.

This new financial structure emerged as part of the industrial development of the business. Several additional elements were essential for subsequent corporate financialization. One was that PSA’s capital control could only be achieved in the financial market by managing the share price and helping raise the necessary capital for financing. In fact, a move to financialization links directly to the amount of capital raised. The more important the capital operations, the more they require a form of financial engineering, which in turn necessitates interventions by professionals in the financial sphere.

In the case of Peugeot, the major capital operation following this reorganization was the purchase of Citroën, carried out in close collaboration with state financial experts, former finance inspectors, and representatives from large investment banks, in particular Lazard Frères Bank.Footnote 77 The new general financial structure required the group to develop financial skills. Before explaining how the reorganization immediately set the company on the road to further financialization, this article addresses the relations between family members and PSAs senior managers, which changed significantly during the same period.

The Power Issue: Managerialization Under Family Supervision

In addition to these industrial and financial elements, the group’s multidivisional structuring also underwent major organizational changes, which refers to the Chandlerian model. This included the managerialization of the board of directors as well as the separation of capital control and operational management tasks. This meant that there was now a certain distance between the Peugeot’s family executives and operational management.

With the division of tasks came a legal device in 1967: the dual management structure of a senior management team and the board of directors. As already indicated, the family had to deal with a succession challenge. In the early 1960s, Jean-Pierre Peugeot was the only family manager with the stature to assume operational management. He endeavored to reorganize the operational management, and planned for Maurice Jordan to be his successor as CEO. A clear statement of this intent was made at the Central Works Council in June 1972: “We are coming to an era that will see the end of the reign of the single man, and we must therefore prepare… young men to facilitate the transition during the beginning of the end of the absolute monarchy.”Footnote 78

The legal format for PSA was also decided in June 1972: the board of directors, comprising ten family members, appointed the company’s first senior management team: François Gautier (chairman), Paul Perrin (chief executive officer), and Pierre Peugeot (chief operating officer). Specialized senior managers were entrusted with the operational executive structure. This solution, which few large French companies used at the time, enabled the Peugeot family to specialize in the financial management of the group’s capital.Footnote 79 This also allowed for an operational management that was collective and mostly external to the family; and it legitimized professional managers, who were no longer recruited only by birth. At this stage, if one observes the features of the managerialization of the group’s administration, one notices that the family still exercised control, and would for decades to come. The meetings of the supervisory board, which occurred several times a year, indicate the interest of the family members in knowing how the industrial companies were progressing. This included supervising major financing, capital control, and the hiring of senior managers.

The dual structure of board of directors and senior management team was used throughout PSA and the main subsidiaries. Automobile Peugeot, therefore, had its own board of directors, with representatives from the main shareholder, PSA, which in turn had the same dual structure. FFP representatives managed the capital and major financing challenges, so the family’s supervision covered all three financial levels (PSA, FFP, and EPF). The same members had multiple functions and seats on the different boards. Important decisions concerning the financial interests of the family occurred at these three levels, and family control proliferated throughout the structures. There was collaboration between senior managers and family members rather than conflict or power plays, and this collaboration was formalized after the reorganization in 1965.

The new financial structure, as noted, was a response to various industrial, financial, and family-related challenges. In the context of general organizational growth, the rise of the Chandlerian version of the Peugeot family business came out of these crucial financial changes. With development of the financial market and formalization of family shareholder interests in the whole business, the financial structure soon experienced changes in relation to the business strategy and the tools designed to maximize financial income.

On the Road to Financialization

This financial structure not only shaped the Peugeot industrial and financial groups but also offered conditions for further changes in corporate financialization. This section addresses the immediate consequences of the reorganization: the orientation of senior management toward financial objectives, the use of financial tools to evaluate subsidiary results, and the possibility for family executives to manage their assets as any other financial asset. The strategy led to financial diversification.

Financial Language and Increases in the Financial Results for Industrial Companies

As already demonstrated, Peugeot’s M&A meant that negotiations for future mergers would involve the Paris financial market. From this perspective, the board sought to inscribe a financial language and integrate managerial methods, with the aim of maximizing the stock market price. In 1969, four years after the reorganization, a seminar aroused the interest of the PSA board.Footnote 80 Members of the two main industrial subsidiaries attended: A. Banzet, assistant director of Peugeot Steel and Tools, and M. Baratte, general director of Automobiles Peugeot. The seminar, organized by Cegos Consultancy, a consultancy and training agency, brought together representatives from Peugeot and twelve other large French companies.Footnote 81 They flew to America to tour twelve large US companies and participate in working meetings. A forty-two-page report from the seminar summarized the key findings.

-

• A company must maximize its share price. The first point in the “rules of the game” is that “you do business to make money.”

-

• “The central objective of the development plan is therefore expressed as a rate of growth in earnings per share, and states that 5 percent per year, corresponds to a company with low ambition, 10 percent to dynamic companies, and 15 percent to very dynamic companies.”

-

• “The creation of wealth and power is measured by the stock market price of shares, which is the price to net profit ratio.”

-

• A graph helped to “explain why US companies take such good care of their shareholders (and among them the financiers): it is not that they love them, it’s that their appreciation of them determines their power, so the general objectives are expressed in terms of ‘earnings per share growth rate.’”Footnote 82

Their participation testifies to these two senior managers’ interest in learning the language of financial maximization. Moreover, Cegos Consultancy’s legitimacy was underlined, as seen from the participation of twelve other large French companies. Following the reorganization in 1965 and the seminar in 1969, the company was clearly oriented toward financial objectives, as observed in a 1973 report to shareholders.Footnote 83 A significant increase in the dividends paid appears; it presents the earnings per share over the short-term, and there is the appearance of the cash flow concept. It mentions a significant increase in financial investments and stresses the need to manage the company’s share price so as to maintain its constant progression.

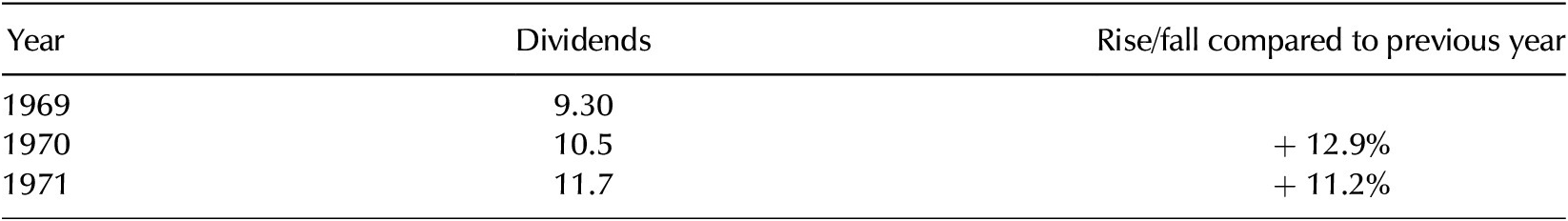

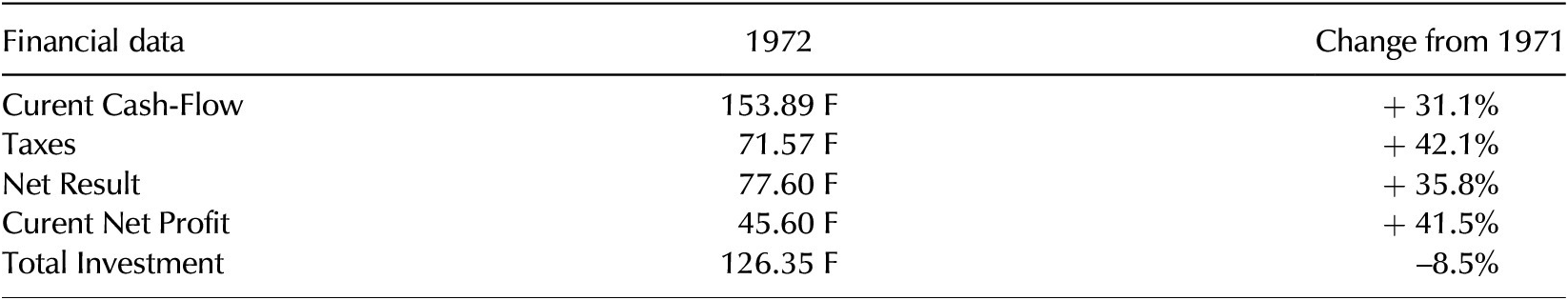

The increase in dividends paid out is a good indicator of PSA’s financial performance (Table 2), and the company’s attitude toward its shareholders. This increase was parallel to the growth of investments. The presentation of the financial results over the short-term in a 1973 report concerns both the distribution of dividends and other financial data.

Table 2. Total dividends paid, 1969 to 1971

The 1973 report indicated the financial profits and costs per share as well as the changes over one year. This is particularly noteworthy in view of the general development and investment program in which the company had been engaged for over a decade. Two years later, PSA bought Citroën, which constituted a considerable investment that cannot be understood in a timeframe as short as one year. This may explain the use of a typical financial presentation of the company’s results for the shareholders. Furthermore, cash flow was explicitly presented as an indicator of financial performance. As noted in the 1973 report:

At the level of the group, the current consolidated cash flow increased at a rate that was twice that of turnover. This development confirms the recovery of margins that began the previous year. [. . .] It allows us to hope that operating margins will be maintained in 1973 even if the ratio between production costs and sales prices undergoes a certain deterioration.Footnote 84

Investment in fixed assets decreased in 1972 as compared to 1971, which is not significant. However, there was a parallel increase in financial investments, notably in the acquisition of shares in external companies, which increased by 15.2 percent in a year, which is significant (Table 3).Footnote 85

Table 3. Consolidated information per share in 1972

Finally, the report includes information about Peugeot’s share price:

The Peugeot SA share price rose from FRF 251 in 1971 to FRF 437.5 in 1972, an increase of 74.3 percent over the year. [. . .] The rise in the Peugeot SA share price was accompanied by a very significant increase in the volume of transactions. With a daily average of FRF 2,051,000 for the futures and cash markets, the company was the eleventh most active French variable-income company in 1972. [. . .] Trading involved approximately 1,300,000 shares, or nearly 22 percent of the capital.Footnote 86

The purpose of this paragraph was for company senior managers to demonstrate that they were committed to managing the share price, ensuring its continued growth, and strengthening the credibility of the share in the Paris financial community to encourage shareholders to speculate on PSA shares.

This language was also a means of pressuring negotiations that were underway with other manufacturers. In 1974, Citroën, which was owned by Michelin holding, was on the verge of bankruptcy.Footnote 87 As noted, in close cooperation with the government, which provided substantial financial support, Peugeot bought out Citroën. The terms of the financial transaction reflect the balance of power between the two companies and highlight Peugeot’s interest in having a strong share price. On September 30, 1976, shareholders ratified the creation of PSA Peugeot Citroën, after a major financial operation: the first capital increase for PSA. A single PSA share was exchanged for 6.25 Citroën SA shares, giving PSA an extremely favorable exchange ratio.

To summarize, in the immediate aftermath of the reorganization, the group’s senior managers turned to Cegos Consultancy and other large French companies to learn how to integrate the tools and mindset needed for financial maximization. The managers created financial reports that emphasized the information perceived as relevant to shareholders. This was to ensure shareholder loyalty and to persuade them to pursue speculative activity with PSA stock by promising them attractive financial results. In parallel with this external financial redirection, the internal control structure was profoundly reorganized around tools that constrained financial profitability.

Financial Control Over the Daily Industrial Life

This aim to maximize financial results was reflected in the design of management tools for analyzing industrial activities. The role of accounting tools in the development of capitalist rationality and accumulation has long been demonstrated,Footnote 88 but during the twentieth century, the implementation of corporate control systems was identified as an important factor in converting industrial activities into financial metrics.Footnote 89 The development of organizational, financial, and budgetary control instruments can be seen as stages in the financialization of production processes.Footnote 90 The role of accounting—especially budgetary control—in creating shareholder value (which is itself a key element in corporate financialization) has also been widely demonstrated.Footnote 91 The implementation of a centralized budgetary control system implies a standardization of work processes, financial and short-term management control, and pressure on workers.Footnote 92 The PSA’s head office created a Controllership Branch in 1972 to standardize and financially control the production process, and to generate substantial profit margins for the holding companies, as reflected in the consolidated accounts.Footnote 93

The establishment of a centralized budget system within PSA introduced financial discipline in the day-to-day running of operational departments. A new management control system emerged in 1972 that served several purposes, including “permanent control of the companies [. . .] by sending them regular information in a form to be developed” and “periodic inspections of companies in the group,” which “will be the subject of reports sent to the head office of each branch, to the Finance Department for the problems within its remit and to the operational departments concerned.”Footnote 94

The centralized budget system allowed resources to be allocated and monitored at all levels, which reflects one central managerial element of a multidivisional company. This system was linked to control of the subsidiaries and branches via the financial department and consolidation of PSA’s financial results.Footnote 95 In particular, it was necessary for subsidiary accounts to be “all presented in the same way” and “connectable” with Accounts Payable, whether accounts are “general” or “operating” in order to “allow a significant consolidation of the margins of each activity.”Footnote 96

The centralized budget system introduced financial constraints over industrial processes by controlling for both adherence to past budgets and by creating new budgets. Needing to justify failures and provide budgets for better financial performance, particularly in terms of cost price, also placed financial constraints on operational decisions. Finances were now subject to the budgetary calendar short-termism, which required a commitment from operational departments to financial controllers each year. It should be pointed out here that the financial control system from 1972 was maintained until 2020. This financial monitoring foreshadowed the dynamics of financialization.

PSA pursued its financial objectives, especially the continuous growth of dividends payable and the PSA share price. The organizational bases for financial processes over industrial ones were reinforced during economic crises in the 1980s and 2010s: the “iron fist” determination to use financial controls to strengthen financial profitability.Footnote 97 Another dimension of PSA’s financialization is to consider is that the activities and departments were autonomous to allow for maximized financial results, achieved by FFP as the holding company.

The Group as a Portfolio of Assets

One element in Neil Fligstein’s definition of financial conception of control is “the corporation as a collection of assets that could and should be manipulated to increase short-run profit.”Footnote 98 This aspect of corporate financialization is manifested in how senior management conceive of a group as a portfolio of strategic activities.Footnote 99 Downsizing and focusing on the core business to the detriment of less profitable activities that are nevertheless essential to the production process is a strategy that has been widely used in large companies since the 1990s, and is associated with financialization.Footnote 100 Peugeot reorganized in 1965 so the business could further develop, but why exactly did it have to do so, and how did Peugeot accomplish it?

In 1973, the takeover of Citroën led to a new subsidiary in PSA: Automobile Citroën. This was alongside Automobile Peugeot. As PSA became increasingly international in scope, it developed France’s automotive sector through the acquisitions of plants in other countries, adding new subsidiaries to its overall structure.

Starting in the 1990s, PSA concentrated on automotive production. It restructured the companies that were manufacturing bicycles and tools to the automotive supply side of its operations. The subsidiary Faurecia became one of the largest automotive suppliers in the world. The restructuring included the merger of two important PSA subsidiaries: AOP and Cycles Peugeot. With the reorganization in 1965, the asset portfolio was modified by removing or adding new activities according to the relative importance of PSA subsidiaries. As noted earlier, this shift in the industrial side of the business was simultaneous with a shift in the financial side.

In 1989, PSA focused on its core automotive business, even though FFP was first listed on the French Stock Exchange in 1989, after several capital increases in the 1980s. At the instigation of the state, the majority shareholder initiated a process of diversification of FFP’s assets. The guideline adopted was to “seek minority stakes in industrial and commercial companies belonging to economic sectors deemed particularly promising in terms of medium-term value, and not to constitute a simple securities investment portfolio.”Footnote 101

FFP’s objective was clearly identified from the outset: not to develop passive investments but to create a medium-term investment activity in anticipation of the increase in asset value. In 1989, FFP invested 124 million francs in the haute couture and perfume sectors, communications, and venture capital. FFP’s investment activity increased from that year onward, experiencing exponential acceleration after 2002.

The group, consisting of PSA and FFP, can be seen as having financial assets managed at two levels. At the industrial level, some activities were sold and others were bought, as allowed by the structure created in 1965. This implied a disconnect between PSA management and operational management of the industrial subsidiaries. At the financial level, FFP’s portfolio of investments and financial participation was also constituted in 1965 with the reorganization.

Naturally, there is no question of adopting a teleological design by saying that the subsequent consequences were anticipated by the 1965 reorganization. Nevertheless, the reorganization involved profound changes and the structure that emerged paved the way for a radically different management of industrial activity. For one, the cognitive framework of financial maximization developed during this period, as did the metrics for evaluation of the industrial processes based on financial objectives. For another, management of the industrial and financial activities was related to the financial investment portfolio administered by FFP. In 1965, Peugeot began to build the bases that made it possible for future strategies to become inextricably bound to corporate financialization.

Conclusion and Discussion

This article demonstrates that important financial shifts were prerequisite to Peugeot’s transformation into a large multidivisional group. Considering the profound mutation of French capitalism during the 1960s, the financial reorganization of the Peugeot family business serves as an emblematic case, and one which diverges from the exogenous narrative on corporate financialization. The major rationalization and M&A movement within the industrial sector, driven by the Gaullist state, led to the restructuring and concentration of industrial capital. At the same time, it is possible to observe the development of the financial groups that became interrelated with large industrial companies.

The transformation of senior managers at Peugeot mirrors the company’s general transformations, as they had to deal with three classic issues from the Chandlerian model. First, their desire to increase Peugeot’s industrial scope was reflected in their search for alliances with other automotive manufacturers. Second, they needed consolidated access to money to better negotiate with competitors, meaning that all family assets were channeled into a group based on its automotive activity. Third, financial reorganization was needed to better handle the challenges of new financial controls and maintain family cohesion with regards to its assets.

The response to this threefold challenge was the major restructuring of the business in 1965. New legal and financial structures linked all of the industrial, commercial, financial, and real estate activities under a single controlling company. The industrial arm was placed under the authority of a specially created management holding company: Peugeot Société Anonyme. There was greater unity in the Peugeot family for a while, as PSA could negotiate automotive mergers from a more advantageous position. The takeover of Citroën in 1974 would de facto lead PSA to create Automobiles Citroën as a new subsidiary.

In parallel with the creation of PSA, a former holding company, FFP, was placed at the head of the group. Its role, once peripheral, became central to the gamut of industrial activities and family shareholders. Its objective was to concentrate the income generated by the industrial arm and to give the family financial control of this arm. Through PSA and FFP, the group was now directly linked to the external financial environment. In this new structure, operational management was carried out at the level of the holding company.

This financial structure can be seen as the institutionalization of financial control beyond the industrial arm. On the one hand, all the industrial subsidiaries could now benefit from FFP’s financial power, since the holding company acted as an interface between the group and the financial market. On the other hand, it brought together for the first time all of the family’s financial resources into a single structure. Within this process, FFP became a factor in the group’s financialization. The switch to a holding company changed the senior managers’ perceptions of the industrial activities. Their distance from the industrial activities moved them away from manufacture and industrial constraints and toward financial concerns.

It is natural that this reorganization went hand in hand with a pronounced orientation toward financial maximization and an evolution in the mindset, tools, and strategy of the group’s management. With the dividends distributed and the group’s cash flow increasing, the senior managers immersed themselves in the financial end by participating in a training session organized by Cegos Consultancy. In the years that followed, the group’s financial department gave rise to a new management control system that placed the industrial activities of the entire group under the discipline of financial profitability. Although a holding company controlling a group’s subsidiaries was a novelty in 1965, this structure allowed the family and management team to handle entities as legally and financially independent assets. The FFP was now managing a portfolio of strategic activities. A few years later, it would be managing a portfolio of investments.

This restructuring represents a seminal episode in the group’s development: the multilevel control structure implemented in 1965 remained intact until 2020. The 2021 merger of PSA and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles into Stellantis N.V. was based on this structure. It allowed the Peugeot family-holding and financial companies at the head of the new corporation to centralize industrial restructuring and company closures while continuing their financial investment activities within FFP.

This case clarifies the understanding of corporate financialization by illustrating the contribution of an endogenous account of this process. If the initial step by the Peugeot’s family business was mainly due to Chandlerian factors, the new multilevel structure of holding companies paved the way for the development of organizational conditions of financialization. More generally, the case of Peugeot provides a counterpoint to the reduced timeframe of financialization, since financialization, particularly in France, is the result of more complex dynamics than the classical narrative would suggest. Hence, this research opens up future research on other large companies and other European national contexts.

Chandler’s and Fligstein’s models are essential in explaining the major organizational developments of the twentieth century. They are sometimes wrongly set in opposition to each other but, as this article has shown, both models can be reconciled. It is possible to emphasize the crucial financial conditions in establishing a large Chandlerian enterprise while also focusing on the Chandlerian origins of corporate financialization. Consequently, the large traditional enterprise is not always the “victim” of external financialization; to a certain extent, it forms the conditions for its development.

Chandler’s argument was that large companies contribute to the construction of markets, and then they play a crucial role in the long-term transformation of capitalism. It is not surprising that the so-called shareholder revolution is based on earlier developments, even when these developments relate to contradictory Chandlerian logic. The contradiction is only apparent, as this article has demonstrated.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Alexis Drach, Neil Fligstein, Patrick Fridenson, Samuel Knafo, Stéphane Jaumier, Pierre Labardin, Tommaso Pardi, Sigfrido Ramirez, the anonymous reviewers and some friends for their comments and constructive suggestions.