Introduction

Richard Nixon’s strained relationship with the American press was legendary. During a 1962 press conference following his failed gubernatorial campaign, Nixon said to collected members of the press: “You don’t have Nixon to kick around anymore.” When he won the presidency six years later, his tone was little changed, with his office frequently accusing the media in general, and newspapers specifically, of having a “liberal bias.” Greenburg (Reference Greenburg2008) argues that Nixon was a driving force behind the creation of the notion of a liberal media aimed at attacking conservative politicians. There is then no little irony that Nixon enjoyed massive support from the editorial pages of those American newspapers in his 1960, 1968, and 1972 presidential campaigns. In each of these elections, the cumulative circulation of Nixon-endorsing newspapers was more than ten million copies greater than the circulation of those that endorsed his opponents.

Nixon’s 1968 victory was narrow. His popular vote victory over Hubert Humphrey was only 0.7 percentage points. His 301 electoral votes meant that he needed almost every state-level victory he got to reach the necessary 270 votes. Of those 301 votes, 84 came from states that he carried by less than 3 percentage points. In this article, we ask whether the large Republican skew in newspaper endorsements was sufficient to swing the Electoral College to Nixon. To answer this question, we utilize the change in the pattern of newspaper endorsements between 1964 and 1968, allowing us to use newspaper-level shifts to estimate their effects on readers’ voting behavior by measuring within-reader changes in voting. To make this analysis possible, we created a novel dataset of newspaper endorsements in 1964 and 1968, which reveals that the size of the Republican advantage in 1968 endorsements was larger than previously measured.

We find that the shift in newspaper endorsements towards Nixon increased the likelihood that a reader supported him by 8.62 percentage points. This point estimate, combined with the size of the Republican skew, means that Humphrey would have won if newspapers had maintained their 1964 endorsement patterns. If, instead, newspapers endorsed Humphrey and Nixon at similar rates, no candidate would have reached 270 electoral votes, though Humphrey would have won the popular vote.

Literature

The general question within the empirical literature on newspaper endorsements has shifted from whether newspapers persuade voters − studies have consistently found that they do − to identifying what mediating factors drive those effects and whether the cumulative effects can be significant. Chiang and Knight (Reference Chiang and Knight2011), Casas et al. (Reference Casas, Fawaz and Trindade2016), and Sprick Schuster (Reference Sprick Schuster2023) all found that newspaper endorsements can significantly affect political preferences. Both Chiang and Knight (Reference Chiang and Knight2011) and Casas et al. (Reference Casas, Fawaz and Trindade2016) found that “surprising” endorsements are more effective. Chiang and Knight (Reference Chiang and Knight2011) go further in showing that, within the settings those papers cover, cumulative effects of endorsements will be small because the relatively rare endorsements will have larger impacts than more common ones. However, Sprick Schuster (Reference Sprick Schuster2023) found a different outcome when studying mid-century American newspapers. He determined that because ideological sorting of readers to like-minded newspapers in the mid-century period was minimal, many more readers were exposed to endorsements that went against their prior leanings, making cumulative effects plausible.

To determine the effect of newspaper endorsements, we exploit a change in the pattern of endorsements between 1964 and 1968. In 1964, Goldwater received endorsements from 394 daily newspapers, while Johnson received 542. The cumulative circulation of the Johnson-endorsing papers was three times that of the Goldwater-endorsing papers. But 1968 saw a dramatic shift towards Republicans. Nixon received 757 endorsements to Humphrey’s 154.

Similar shifts have previously been used by researchers to estimate the effect of endorsements. Both Ladd and Lenz (Reference Ladd and Lenz2009), who looked at a similar shift in 1990s British media, and Erikson (Reference Erikson1976), who looked at the shift between 1960 and 1964 in American papers towards Democrats, find large persuasive effects of newspapers on voting behavior. Readers paid close attention to these endorsements. Robinson (Reference Robinson1972) studied voters’ perception of their own media exposure in the 1968 election. About 50 percent of the time, voters claimed being exposed to their newspaper endorsing one candidate over the other, more than any other media source. Robinson then compared the respondents’ claims to the actual media that they consumed, finding that nearly 90 percent of the claims were found to be accurate.

The 1968 election

In March 1968, President Johnson, battered and exhausted by foreign policy failures in Vietnam and domestic unrest, announced his withdrawal from the 1968 election and endorsed Humphrey, his vice president. This endorsement was also intended as a blow to the campaigns of those who represented the anti-Vietnam wing of the party, Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy, Sr. Johnson even forced members of his cabinet to remain neutral after two of them initially endorsed Kennedy (Nichter Reference Nichter2023, p. 21). Following Kennedy’s assassination in June, Humphrey won the nomination over McCarthy in a contentious convention. Although he won on the first ballot, he earned only 60.1 percent of the delegate votes. These intra-party tensions were further illustrated by the large-scale conflicts that took place outside the convention between anti-war protesters and Chicago police.

Leading up to the party conventions, polling showed Humphrey consistently ahead of Nixon, leading in Gallup and Harris polls by an average of 3 percentage points in June–July. But he lost ground in late August and September. The Gallup poll of September 29 showed Nixon leading by 15 percentage points. This gap narrowed to reflect a razor-thin margin on election day, with Nixon going on to win the popular vote by 0.7 percentage points.

Humphrey’s drop in the polls coincided with a wave of newspaper endorsements for Nixon, who had been nominated by Republicans at their convention on August 8. Endorsements began appearing as early as August 30, when the Pottstown Mercury endorsed Nixon in a front-page editorial. The seventeen papers of the Scripps-Howard chain endorsed Nixon on September 30, and Nixon continued to enjoy an advantage of newspaper endorsements through Election Day, including the endorsements of most of the nation’s largest newspapers, such as the Dallas Morning News (September 29), the Los Angeles Times (October 13), and the Detroit Free Press (October 20). Sprick Schuster (Reference Sprick Schuster2023) found that endorsements had a large and immediate persuasive effect on readers’ intention to vote of about 19 percentage points. It is therefore possible that newspaper endorsements were a significant factor in this shift in opinion polls.

Figure 1 shows the state-level breakdown of newspaper endorsements in 1968, weighted by newspaper circulation. In the average state, Nixon received endorsements from 57.76 percent of all newspapers. Humphrey received endorsements from only 15.06 percent, while 27.18 percent endorsed neither major party candidate. Humphrey received the majority of endorsements in only a handful of states, and in fourteen states, we failed to find any newspaper endorsing Humphrey. Of the newspapers that endorsed neither Humphrey nor Nixon, abstention was the most common. Although George Wallace received some endorsements, most newspapers that chose to avoid supporting a major party candidate endorsed no one. We identified only eleven papers that endorsed a third-party candidate.

Figure 1. Percent of newspapers endorsing candidates, 1968.

Notes: The figure shows the percentage of newspapers, weighted by circulation, that endorsed Nixon in 1968, endorsed Humphrey in 1968, or endorsed neither in 1968. Alaska and Hawaii, where newspaper data was unavailable, are excluded.

This Republican skew marks a significant shift from 1964, when most newspapers endorsed Johnson over Barry Goldwater. Although this represents a change in party allegiance, it fits in with a larger trend of newspapers endorsing the more experienced candidate. Footnote 1 Ansolabehere et al. (Reference Ansolabehere, Lessem and Snyder2006) found that by the mid-20th century, newspapers had shifted from endorsements that focused on party affiliation to ones that focused on individual candidate characteristics, favoring incumbents and those with electoral experience. DeLuca (Reference DeLuca2025) found this to be true for local candidates as well. In his summary of newspapers’ own statements about how they endorse, DeLuca said that “they can be treated as a kind of expert opinion about which candidate has better governing potential.” The 1964 campaign provides a clear example of how newspapers valued experience. Papers endorsing Johnson consistently criticized Goldwater for his inexperience and temperament. The Kansas City Star stated, “We frankly fear that the Goldwater philosophy … might plunge the world into the uncertainty of greater international tensions.” Footnote 2 The Syracuse Post-Standard sarcastically wrote, “We respect Senator Goldwater’s sincerity, but he has proved himself too reactionary and too unstable.” Footnote 3 The Saturday Evening Post published a blistering attack on the Republican nominee, saying, “Goldwater is a grotesque burlesque of the conservative he pretends to be. He is a wildman, a stray, an unprincipled and ruthless political jujitsu artist.” Footnote 4 The 1968 election featured two experienced candidates, with an incumbent vice president against a former one. But the volatile summer of ’68 allowed Nixon to position himself as a stabilizing force, especially when compared to Goldwater’s “political jujitsu” four years prior. His 1960 campaign, during which he also received the majority of endorsements, made Nixon a known quantity. Editorial pages followed suit, calling Nixon a “steady hand at the helm.” Footnote 5 Meanwhile, Humphrey was saddled with many of the same criticisms that had doomed Johnson’s aborted campaign and struggled to stake out his own policy positions without alienating the president (Nichter Reference Nichter2023, p. 42). One paper stated, “Mr. Humphrey … has been associated with a foreign policy that began with the Bay of Pigs and had continued straight downhill to Vietnam…” Footnote 6 Nixon cleverly attempted to stay away from the question of Vietnam, even canceling a planned speech on Vietnam after Johnson’s withdrawal from the race (Chester et al. Reference Chester, Hodgson and Page1969, p. 18). He was so coy on specifics that newspapers simply began reporting that he had a “secret plan” (Johns Reference Johns2010, p. 197). Instead, he framed himself as the “law and order” candidate, focusing on domestic stability following a chaotic and violent year for American cities, including the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., which was followed by riots in numerous American cities, the assassination of Robert Kennedy, and the violence surrounding the Democratic National Convention. The Houston Chronicle said Nixon was “the best chance of restoring peace, economic stability, the unity of spirit and the confidence this country so desperately needs.” Footnote 7 Similar sentiments can be found in many Nixon endorsements, including the Tampa Tribune, which stated, “As president, we believe he could and would quiet internal conflict and restore the stability this nation sorely needs.”Footnote 8

But how can this endorsement advantage be squared with Nixon’s antagonistic stance towards the press? One explanation is that his edge in endorsements fits well into the narrative of a more media-savvy campaign, utilizing television and other forms of persuasion much more effectively than in 1960. Spurred by a young Roger Ailes, who reassured Nixon, “Television is not a gimmick” (McGinniss Reference McGinniss1969, p. 63), the campaign invested heavily in the planning and production of television appearances. This culminated in a November 4, four-hour telethon where a polished and relaxed Nixon answered questions from voters. This event was seen as so successful that Nixon wrote in his memoir that without it, he would have lost the election (Nixon Reference Nixon2013, p. 329).

Another explanation stems from the traditional “wall of separation” between the news and editorial sides of newspapers (Kahn and Kenney Reference Kahn and Kenney2002), which allowed systematic differences to develop in tone between their reporting and endorsements. St. Dizier (Reference St. Dizier1986) showed that newspaper reporters during this period were often much more liberal than their newspapers’ editorial stances would suggest. But perhaps the best way to square Nixon’s criticism of the press with the endorsement advantage is to recognize that his criticism of the media appeared to be aimed at what he saw as unfavorable news coverage, not editorial content. Several high-profile news events, including Nixon’s “Secret Fund” scandal in 1952 and Alger Hiss’s involvement in the 1963 ABC special “The Political Obituary Richard Nixon,”Footnote 9 fueled this feeling of unfair treatment. He also held personal animus toward a Washington, D.C., press corps that was probably not a representative sample of all media:

You can see it in my press conferences all the time. You read the Kennedy press conference and see how soft and gentle they were with him, and then you read mine. I never get any easy questions – and I don’t want any. I am quite aware that ideologically the Washington press corps doesn’t agree with me. (Drury Reference Drury1971, p. 395)

Empirical analysis of the newspaper coverage of the 1968 election supports the idea that the tone of editorial and news reporting differed. Graber (Reference Graber1974) found that statements about Nixon in the news coverage were seven percentage points more likely to be negative (48 percent) than positive (41 percent). For Humphrey, they were nine percentage points less likely to be negative (34–43 percent). Regardless of whether this tone of coverage was warranted, it highlights a disconnect between newspapers’ editorial endorsements and their news coverage in 1968.

Though he received little newspaper support, George Wallace had a large impact on the 1968 campaign. Dubbed the “Spoiler from the South” by Time magazine, Footnote 10 Wallace sought to increase the power of aggrieved white southerners who were alienated from their nominal party’s nominee, Humphrey. Wallace also opened a lane for Nixon to make headway in a set of states long dominated by Democrats. Nixon believed the South was critical to his victory and shaped his campaign partially around presenting himself as a viable alternative to Wallace for Southern voters (Black and Black Reference Black and Black1992, p. 298). He did this by sculpting his law and order campaign around issues like anti-busing and other messages later criticized as dog-whistle politics (Cheliotis Reference Cheliotis2024). But beyond this indirect effect on campaign strategies, Wallace’s popularity in the South created the potential for Electoral College deadlock. Wallace would go on to win five states with 45 electoral votes. This meant that only 493 electoral votes remained, from which either Nixon or Humphrey would need to secure 270 to win the presidency via the general election. The alternative, a contingent election, would have given Wallace significant power in determining the winner and shaping future policy. Though Wallace often stated he was running to win, he also acknowledged his desire to sway policy in the event of the election being sent to the House of Representatives, saying that his goal was “a coalition government” (Chester et al. Reference Chester, Hodgson and Page1969, p. 658).

Data and empirical framework

State-level voting data come from the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (1994). To create our dataset of newspaper endorsements, we started with data from Gentzkow et al. (Reference Gentzkow, Shapiro and Sinkinson2014), which provides self-reported endorsement data from newspapers via Editor and Publisher surveys taken throughout the 1964 and 1968 campaigns. However, these data were incomplete and required supplementation. To do this, we used newspapers.com and individual newspaper archives, similar to the method used by Sprick Schuster (Reference Sprick Schuster2023). Using this method, we found that the Editor and Publisher data were far from complete and contained multiple errors. In 1964 alone, we identified 276 cases of missing or incorrectly reported endorsements.Footnote 11

Voting and newspaper readership data come from the 1968 American National Election Study (ANES). This survey asked respondents three questions critical to our identification strategy: their vote in 1968, their vote in 1964, and the newspaper they read for election coverage. We use the change in newspaper endorsements between 1964 and 1968 to predict changes in voter preferences between those two years. The choice of voters in 1968 is modeled as:

VoteRepublican i,1968 is equal to 1 if a respondent i voted for Richard Nixon in 1968, and 0 otherwise. This means that we are grouping Democratic, third-party, and non-voters together. Endorsement i,1968 is equal to 1 if the newspaper read by respondent i endorsed Richard Nixon for president in 1968, and 0 otherwise, similarly grouping Democratic endorsements, third-party endorsements, and non-endorsements together. X i is a vector of observable voter characteristics (age, marital status, number of children, education level, and whether they served in Vietnam).

β, the coefficient on our endorsement variable, will only yield unbiased results if the error term, e i , is uncorrelated with our outcome variable. The biggest threat to this is the ideological sorting of readers to like-minded newspapers. Although Sprick Schuster (Reference Sprick Schuster2023) found little evidence of ideological sorting during this period, it is certainly possible that unobserved characteristics that affect people’s newspaper choice is also correlated with their voting decisions.

Therefore, we use the fact that we can measure both the change in voter behavior between 1964 and 1968 and the change in the endorsement of their newspaper between those same years. This will allow us to difference out any time-invariant omitted variables, including any long-term sorting of readers to ideologically similar newspapers. We estimate the effect of newspaper endorsements using the following first-difference model:

Where ∆VoteRepublican i,1968 = VoteRepublican i,1968 − VoteRepublican i,1964. It is therefore the change in a respondent’s vote between 1964 and 1968, taking on a value of +1 if the respondent did not vote for Goldwater in 1964 but did vote for Nixon in 1968, −1 if a voter voted for Goldwater but then did not vote for Nixon, and 0 if they voted for a Republican in both elections or neither election. Because X i,1968 comes from responses in the 1968 election, we do not measure differences in these variables. However, this is done at little cost, since many of them (such as date of birth) do not change over time. Instead, these variables capture any demographic-dependent political shifts that occurred within the electorate between 1964 and 1968.

It is possible that observed endorsements are something of a proxy for the larger editorial stance of the newspaper, and potentially even its coverage of news and politics. While endorsements are an editorial decision made by the publisher or editor-in-chief, they might be correlated with the coverage of the newspaper. Kahn and Kenney (Reference Kahn and Kenney2002) showed that newspaper endorsements for US Senate races in the 1990s were correlated with the tone of news coverage. Within our framework and setting, a larger slant is less likely. St. Dizier (Reference St. Dizier1986) shows that the political leanings of newspaper reporters around this period were significantly more liberal than what would be reflected by presidential endorsements. Additionally, Graber (Reference Graber1974) showed that Nixon received less favorable press coverage than Humphrey. Nonetheless, the idea of treatment throughout our analysis should more properly be thought of “reading a newspaper that endorses candidate X” instead of “reading an endorsement for candidate X.”

Results

Of the 1,373 ANES respondents in 1968 who reported being eligible to vote in 1964, 25.3 percent of them reported voting for Barry Goldwater. In 1968, 32.7 percent of this group reported voting for Richard Nixon. This is roughly similar to the nationwide trend. Goldwater received the votes of 24.2 percent of the voting-age population. Nixon received the votes of 27.2 percent of the population in 1968.

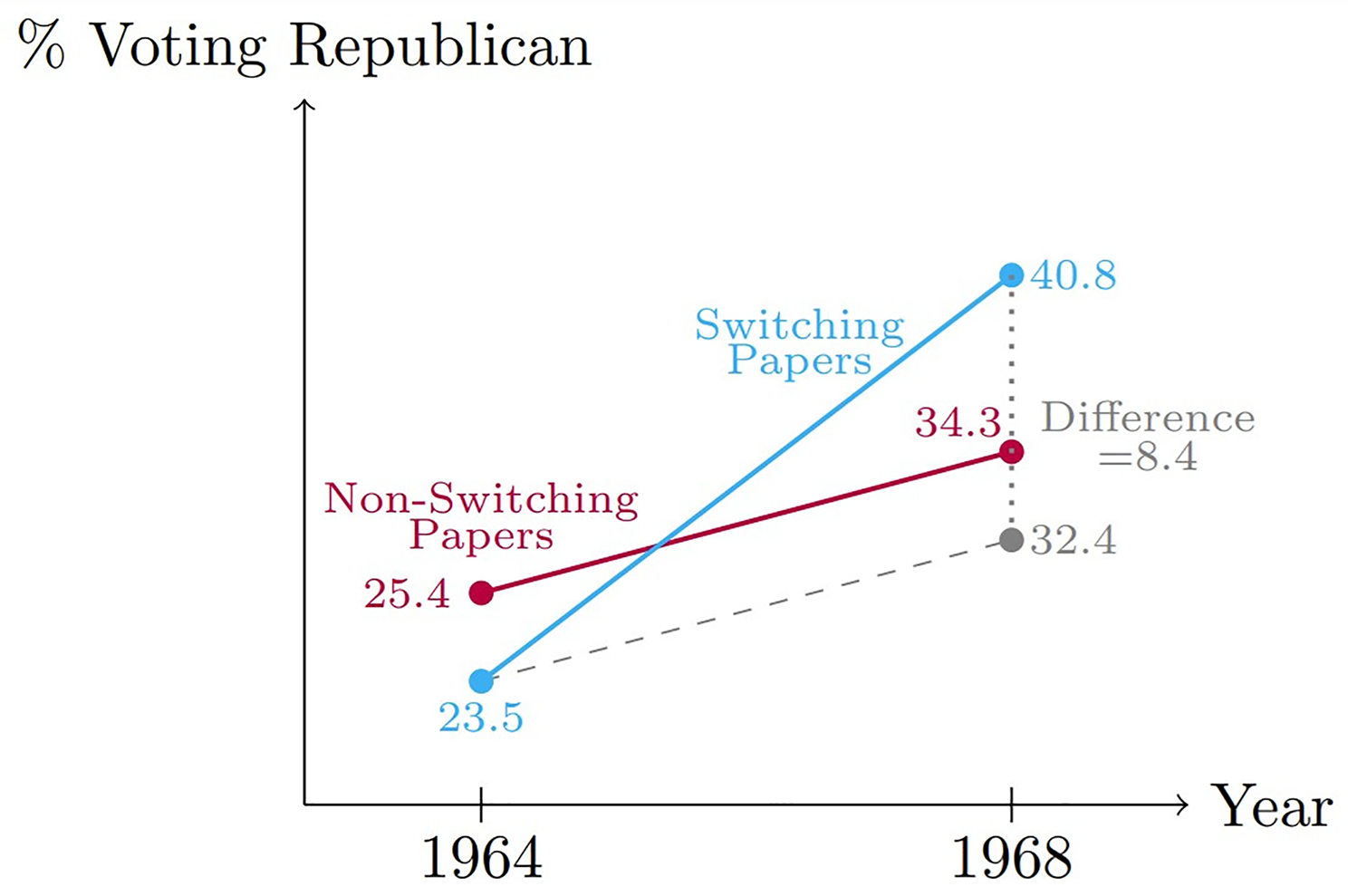

The changes in the voting behavior of ANES respondents are driven by those who read newspapers that changed their editorial stance between 1964 and 1968 to favor Republicans. Figure 2 shows this shift across different groups of newspaper readers. Of those who read newspapers that did not endorse a Republican in either 1964 or 1968, 25.4 percent reported voting for Goldwater in 1964, and 34.3 percent reported voting for Nixon in 1968, an 8.9 percentage point increase, showing the large shift in voter support for Republicans over those years. But for those who read a newspaper that didn’t endorse Goldwater in 1964 but shifted towards Republicans by endorsing Nixon in 1968, the change is dramatic: 23.5 percent voted for Goldwater in 1964, but 40.8 percent voted for Nixon four years later. If this group had experienced the same 8.9 percentage point increase as other newspaper readers, only 32.4 percent of them would have voted for Nixon. This means that among readers of Nixon-endorsing newspapers, support for Nixon was 8.4 percentage points greater than expected.

Figure 2. Change in reader Republican support by newspaper type.

Notes: The figure shows the percentage of ANES respondents who voted for Goldwater in 1964 and Nixon in 1968, broken into two groups. “Switching Papers” are readers of newspapers that did not endorse Goldwater in 1964 but did endorse Nixon in 1968. “Non-switching Papers” are readers of newspapers that did not endorse Goldwater in 1964 and also did not endorse Nixon in 1968.

Table 1 shows the regression results from the first-difference equation. We find that reading a newspaper that endorses a Republican candidate increases the probability that someone votes for that candidate by 8.62 percentage points, in line with the aggregate measures shown in Figure 2. The results are statistically significant, allowing us to reject the null hypothesis that endorsements have no effect.

Table 1. Regression results

Notes: Coefficients are from a first-difference regression. The dependent variable is change, between 1964 and 1968, in an indicator variable equal to 1 if someone voted for the Republican candidate, and 0 otherwise. All regressions include controls for age, marital status, number of children, education level, and whether the respondent served in Vietnam. Alaska and Hawaii, where newspaper data were unavailable, are excluded. Robust standard errors, clustered at the newspaper level, in parentheses. For column 2, which includes non-newspaper readers, non-readers are clustered into one group. ***p<.001. **p<.05 *p<.1.

The biggest threat to this identification strategy is unobserved time-variant political shocks that lead to changes in both voters’ choices and newspapers’ endorsements. What if newspaper readership-specific changes are driving our results? Fortunately, there is little evidence that readers during the era sorted across newspapers in a way that anticipated the shift in preferences between 1964 and 1968. Among readers in 1964, of newspapers that supported Republicans in neither 1964 nor 1968, 23.36 percent identified as Republicans. Of those who read a newspaper that didn’t endorse a Republican in 1964 but switched to endorsing Nixon in 1968, only 20.05 percent identified as Republican. But the 1968 ANES responses suggest that the shift towards Nixon was strongest among self-declared Republicans. This means that if sorting across newspapers was driving our results, we would expect Republicans to be more likely to already be reading the newspapers who were changing their endorsements. But we find no evidence of this.

We can also address this concern while working within the first-difference framework by utilizing the ANES sample of voters who reported not reading any paper for political coverage. This group was omitted from our original sample, but by including them with a full set of city fixed effects,Footnote 12 we can control for any city-specific changes in voter preferences between 1964 and 1968. Because non-readers are not exposed to endorsements, Republican or otherwise, the dependent variable for this group is coded as 0. While these are not perfect controls for readership-specific shocks, their inclusion provides evidence that time-variant shocks are not regionally specific. These results, presented in Column 2 of Table 1, show that controlling for non-readers in the same area, while also adding a full set of place fixed effects, actually increases our point estimates. The point estimate of 0.100 means that newspaper readers of papers that switched their endorsements to the Republican candidate were 10 percentage points more likely to switch to the Republican candidate when compared to non-newspaper readers or readers of other newspapers in the same town.

While our regression results show the effect of newspaper endorsements on Republican voter support, they are not sufficient to determine the effect of endorsements on vote shares. We first need to determine where these additional Republican voters are coming from. Are they Democratic voters who are switching, or people who are choosing Republicans instead of third-party candidates or not voting at all? Our results, shown in Columns 3 and 4 of Table 1, indicate that endorsements for Republicans prevented a larger flow of voters from embracing third-party candidates or abstention. We find that a Republican endorsement does not decrease the likelihood that someone votes for the Democrat, as seen in Column 3. The point estimate is almost exactly zero, and we can rule out a moderately large effect. If the 0.0862 increase in Republican voting was coming from people who would otherwise vote for the Democrat, we would expect the endorsement effect on Democratic vote shares to be −0.0862, but this value is outside the 95% confidence interval for our estimate [−0.0785, 0.0631], meaning that we can reject the hypothesis that Republican endorsements had a negative effect on Democratic votes of a similar magnitude to the positive effect they had on Republican votes. Instead, endorsements decrease the likelihood that a respondent fails to vote for either Republican or Democratic candidates, as seen in Column 4. The point estimate of −0.0784 means that a Republican endorsement decreases the likelihood that a voter fails to vote for either a Democrat or a Republican by 7.84 percentage points. Therefore, the additional Republican votes are not coming at the expense of votes for the Democratic candidate. This suggests that endorsements may have affected voters that were on the fence between Nixon and Wallace.

The point estimate of 0.0862 means that for every 1,000 readers who are exposed to a Republican political endorsement, 86.2 more of them will vote for the Republican candidate. Since we find no negative effects on votes for the Democratic candidate, this will increase the vote margin between the Republican and Democrat by 86.2. If, instead, the votes were coming at the expense of the Democrat, this would increase the vote margin by 172.4. Using the shift in endorsements between 1964 and 1968, we can estimate how many more people voted for Nixon because of the aggregate shift in newspaper endorsements.

Figure 3 shows the state-level shift in newspaper endorsements between 1964 and 1968. It shows the change in the percent of newspapers, weighted by circulation, that endorsed the Republican candidate. All but six states saw an increase in the share of papers endorsing the Republican candidate, and most states experienced large shifts, with seventeen states seeing shifts of more than 50 percent. This was also true of swing states. Of the seven states for which we have data and for which Nixon and Humphrey were within 3 percent (WA, TX, MD, MO, NJ, OH, IL), the average rank of the percentage change was 14 among the forty-eight Continental United States, meaning that swing states saw a larger than average shift towards Republican endorsements.

Figure 3. Aggregate shift in republican newspaper support by state.

Notes: The figure shows the change in the percentage of newspapers, weighted by circulation, that endorsed Republicans between 1964 and 1968. Alaska and Hawaii, where newspaper data were unavailable, are excluded.

How, then, do we convert the marginal effect of endorsements into a change in the general election results as a whole? To perform this analysis, we must first make assumptions that are informed by our results thus far.

-

A Republican newspaper endorsement increases the likelihood that a reader who relies on that newspaper for political coverage votes for a Republican by 8.62 percentage points.

-

The number of people who rely on newspapers for political coverage is not the same as the circulation of the newspaper but can be calculated using the method described by Sprick Schuster (Reference Sprick Schuster2023). He showed that when you account for the fact that (1) each copy of a newspaper is read by more than one person, and (2) not all newspaper readers rely on newspapers for political coverage, each copy of a newspaper was read for political coverage by an estimated 1.348 people in 1968.

-

We will consider two counterfactual scenarios: first, what if newspapers maintained their 1964 endorsement strategies; and second, what if newspapers endorsed Democrats and Republicans in equal numbers in 1968?

As an example, consider Missouri, which Nixon won by 20,488 votes. The total circulation of newspapers in Missouri was 1,853,741, meaning that 1,853,741×1.348=2,498,842 readers in Missouri read newspapers for political coverage. Using our dataset of newspaper endorsements, we find that the cumulative circulation of newspapers endorsing Republicans increased by 1,182,446 between 1964 and 1968, or an increase in readership of 1,182,446×1.348=1,593,937. This means that the number of people who switched to voting Republican because of the change in newspaper endorsements was 1,593,937×0.0862=137,397. This number is much larger than the 20,488 gap between Nixon and Humphrey, indicating that the shift in endorsement patterns between 1964 and 1968 was large enough to swing Missouri, and its twelve electoral votes, to Nixon.

In Table 2, we estimate the cumulative effects of newspaper endorsements for each state (excluding HI and AK) against the counterfactual of maintaining the same endorsement patterns as 1964. We find that if newspapers were endorsing in the same patterns as 1964, 33.7 million fewer readers would have been exposed to a Republican endorsement, and Nixon would have earned 2.9 million fewer votes. As a result, he would have lost eight additional states, representing 141 electoral votes. In all but one of these states, Humphrey came in second, with Wallace coming in second in Tennessee. This suggests that Nixon would have ended with 160 electoral votes, Humphrey winning the Electoral College with 321 votes, and Wallace winning a sixth state, bringing his electoral college votes to 57.

Table 2. Counterfactual: Newspapers maintain 1964 endorsement patterns

Notes: The table shows the estimated change in the number of readers exposed to Nixon endorsements, the estimated effect of that change on voting behavior, and the loss or gain of Nixon electoral votes due to those effects if newspapers endorsed the candidate of the same party that they endorsed in 1964. Using ANES responses, we assume that each circulated newspaper is read by 1.348 people, and we use the point estimate of 0.0862 to calculate the shift of endorsement exposure on voting behavior. Alaska and Hawaii, where newspaper data were unavailable, are excluded.

But this counterfactual may be artificially increasing the likelihood that we find that newspapers were pivotal in the election. While this tells us how much of the voting shift between 1964 and 1968 can be attributable to newspaper endorsements, a return to 1964 endorsement patterns may not be a suitable counterfactual. By using 1964, a year in which an unusually large number of newspapers endorsed the Democrat, we are using an uneven distribution of endorsements. Suppose that instead we assume that, among the endorsing newspapers in 1968, endorsements were split evenly between Humphrey and Nixon. This provides a more neutral counterfactual. We achieve this by reducing the circulation of Nixon-endorsing newspapers and increasing the number Humphrey-endorsing newspapers by an equal amount until the circulations are equal. Using similar calculations as above, we again use Missouri as an example. We find that if we gave Nixon and Humphrey equal levels of 1968 endorsement in Missouri, it would decrease the cumulative readership of Nixon-endorsing newspapers by 568,857, resulting in a decrease in Nixon votes of 568,857×.0862=49,036. Again, this would be sufficient to swing Missouri to Humphrey.

In Table 3, we consider what would have happened if endorsements in 1968 had been split evenly between Nixon and Humphrey. Under this counterfactual, 17.1 million fewer people would have been exposed to a Nixon endorsement. Given our 0.0862 point estimate, Nixon would have lost 1.475 million votes, eliminating his popular vote edge. Humphrey would have won four more states than he actually did (Delaware, Illinois, Missouri, and Ohio). These states had 67 electoral votes, and would not be enough for a Humphrey win, falling short with 258. But since Nixon would now have 234 electoral votes, Footnote 13 there would be no Electoral College winner. This result would have triggered a contingent election, with the House of Representatives choosing the president. Figure 4 shows the state-level shift in voting that would have occurred if newspapers in each state had endorsed Humphrey and Nixon with equal probability.

Table 3. Counterfactual: Newspapers endorse Republicans and Democrats equally

Notes: The table shows the estimated change in the number of readers exposed to Nixon endorsements, the estimated effect of that change on voting behavior, and the loss or gain of Nixon electoral votes due to those effects if newspapers in 1968 were equally likely to endorse Nixon and Humphrey. Calculations are done by taking the total circulation of Nixon-endorsing newspapers, then determining the change needed for Republican and Democratic endorsements to be equal. Using ANES responses, we assume that each circulated newspaper is read by 1.348 people, and we use the point estimate of 0.0862 to calculate the shift of endorsement exposure on voting behavior. Alaska and Hawaii, where newspaper data was unavailable, are excluded.

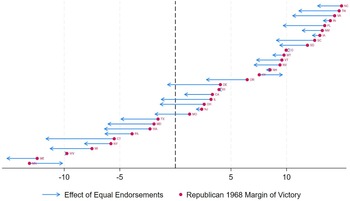

Figure 4. Effect of equal endorsements on Republican margin of victory, 1968.

Notes: The figure shows Republican margin of victory (or loss), along with the shift that would have occurred to the Republican two-party share of each state’s votes if newspapers had endorsed Nixon and Humphrey equally. Calculations are done by taking the total circulation of Nixon-endorsing newspapers, then determining the change needed for Republican and Democratic endorsements to be equal. Using ANES responses, we assume that each circulated newspaper is read by 1.348 people, and we use the point estimate of 0.0862 to calculate the shift of endorsement exposure on voting behavior. Only states won by Humphrey or Nixon, and for which the margin of victory was within 15 percentage points, are included. Alaska and Hawaii, where newspaper data were unavailable, are excluded.

Another, perhaps more straightforward, way of asking the relevant research question is: given the shift in newspaper endorsements, how large would the causal effects have to be to be pivotal in the 1968 election? One of the main contributions of this article is the creation of the 1964–1968 endorsement data, which reveal a stronger Republican skew in 1968 than previously realized. Given the extant body of literature that has previously estimated the effect of endorsements, we can simply ask if the effect necessary to make endorsements pivotal in 1968 is a reasonable one.

With a point estimate of 0.0862, we find that Nixon’s advantage in newspaper endorsements was pivotal in his wins in Delaware, Illinois, Missouri, and Ohio. Given the Republican endorsement advantage in each state, the causal effect would need to be at least 0.0739 to have shifted Delaware, an effect of at least 0.0624 would have shifted Illinois, an effect of at least 0.0571 would have shifted Ohio, and 0.0361 for Missouri. Ohio and Missouri had 38 electoral votes, sufficient to drop Nixon below the 270 needed for an Electoral College victory. Therefore, as long as newspaper endorsements increased the likelihood of voting for a candidate by 5.71 percentage points, newspapers persuaded enough voters to win Nixon the 1968 election.

If a 5.71 percentage point effect of newspaper endorsements is needed for endorsements to have been pivotal, we can simply ask whether an effect of that size is plausible. Sprick Schuster (Reference Sprick Schuster2023) found that a newspaper endorsement increased the likelihood that its readers state a support for a candidate by 19.9 percentage points. Ladd and Lenz (Reference Ladd and Lenz2009) found that endorsements had an effect equivalent to 8.6–14.0 percentage points on its readers. The 8.62 percentage point change found in our article is plausible given what has been found in other contexts, and a 5.71 effect is smaller than any of the empirical estimates of causal effect. This shows that we need not simply rely on the estimation strategy presented here to defend the claim that newspapers were pivotal in the 1968 election.Footnote 14

This thought experiment can also be applied to the biggest assumption that we have used throughout our analysis: that each paper is read by 1.348 people for political coverage. While this number is based on responses to the survey itself, survey respondents may not be fully representative of the entire population. Using our point estimates, we find that newspapers persuaded enough people to give Nixon an Electoral College victory as long as at least 0.893 people read each paper for political coverage. Estimates of the “pass-along rate” for newspapers and magazines are typically above 2 (Atkin Reference Atkin1967; Simpson Reference Simpson2011). Therefore, as long as 45 percent of newspaper readers read the paper for political coverage, Nixon’s advantage in endorsements were sufficient to be pivotal in his election.

Discussion

A contingent election would have been an unprecedented scenario in modern American politics. The 12th Amendment outlines the rules governing this. The 91st Congress, which was elected in the same 1968 election, would choose the winners: the House of Representatives choosing the president and the Senate choosing the vice president. However, instead of presidential votes being allocated based on House seats, each state’s representatives would meet to cast a single ballot. Only the top three electoral vote-getters (Nixon, Humphrey, Wallace) would be eligible, and the first one to receive twenty-six votes from the state delegations would become president.

Democrats had a majority in exactly twenty-six state delegations of House members, Republicans had the majority in nineteen, and five states were tied. If each of those twenty-six states had supported Humphrey, he would have won the contingent election. Footnote 15 However, George Wallace’s role as a spoiler would likely have likely been critical in such a scenario. Each of the five states Wallace won had Democratic-majority delegations, and Humphrey was unpopular in the South. His average vote share in the five Wallace states was 25.4 percent. Given Wallace’s allegiance with the conservative movement, he might have attempted to garner these delegation votes for Nixon. But even if all five Wallace states voted for Nixon and all nineteen Republican majority states did as well, this would leave him with only twenty-four votes.

This leaves the five tied delegations of Illinois, Montana, Oregon, Virginia, and Maryland. Humphrey only won Maryland, though in our counterfactual world, he would have also won Illinois. If we add Maryland and Illinois to Humphrey’s side, he still would have needed three Wallace states to reach the required twenty-six delegation votes. This means that both Humphrey and Nixon would have some plausible path to victory in a contingent election, with both trying to siphon off enough support from Wallace-voting states and states with tied delegations while holding onto states where the party balance of the US House delegation was in their favor. One possible solution was a bipartisan plan, reportedly supported by more than fifty members of Congress, proposed by Representatives Charles Goodell and Mo Uhall in July 1968, when Wallace’s growing support made a contingent election appear more likely. Under the plan, the House of Representatives would vote for the candidate who received a plurality of the popular vote (Chester et al. Reference Chester, Hodgson and Page1969, p. 655). Given the shift in votes we calculated in Table 3, this would have been Humphrey.

To complicate this further, a contingent election would need to be completed by January 20th, or the vice president-elect would be sworn in as president. The vice president would have been selected by the Senate, with each senator having one vote. With fifty-seven Democratic senators, it is possible that Humphrey’s running mate, Edmund Muskie, would have earned the majority of the votes, but again Wallace’s shadow looms large. All ten senators from Wallace-voting states were Democrats, and all were segregationists. Each of those who had been in the Senate in 1964 opposed the Civil Rights Act. Their support for Muskie, a northern liberal, would not have been guaranteed. The alternative, Spiro Agnew, may have been seen as a suitable compromise option. He was a “law and order progressive” who supported Civil Rights legislation while also criticizing black leaders during the 1968 riots (Nichter Reference Nichter2023, p. 117). Regardless, fifty-seven Democratic votes (or fifty-three Republican/Dixiecrat votes) would not be enough to avoid a filibuster. In such a case, a vice-presidential vacancy would have been a possibility, especially given that outside candidates were impossible. The rules state that the Senate must choose between the top two vote-getters (Muskie and Agnew). Ironically, Humphrey would have been presiding over the vice-presidential election. As the incumbent vice president, he would have served as the president of the Senate for the 91st Congress from January 3, when the new Senate was sworn in, to January 20, when Humphrey’s term ended.

One secondary effect of a contingent election could have been a change in the rules governing the election of the executive branch. Sending the election to the House of Representatives may have led to anything from marginal, parliamentary changes to an overhaul of the election system entirely. By sending the election of the vice president to the Senate, the majority coalition would potentially have had to eliminate the filibuster to seat Muskie or Agnew.

Conclusion

Though the role of the American newspaper has waned in recent years, it was the primary source of news for the voting public through much of the twentieth century. And while the newspaper endorsement has become less common, it was a much-discussed component of presidential campaigns. Through much of the twentieth century, those endorsements were overwhelmingly in support of the Republican candidate.

Using the political shift in newspaper endorsements between 1964 and 1968, we find that readers of newspapers that changed their endorsement were much more likely to switch their own voting behavior. Regression analysis shows that reading a switching newspaper led to an 8.62 percentage point increase in the likelihood of voting for Nixon. This point estimate, combined with the scale of the Republican skew in endorsements, means that newspapers persuaded enough voters to be pivotal in Nixon’s Electoral College victory.

Broadly, this research speaks to the power of mass media to shape election outcomes. A large body of research on fundamentals-based models has shown the importance of broader economic and political climates in affecting election outcomes (Hummel and Rothschild Reference Hummel and Rothschild2014), but campaigns and voter persuasion matter, especially in close elections. Newspaper endorsements are unlikely to sway significant numbers of voters in today’s political climate, but this speaks more to a changing role of newspapers within the broader media landscape than to changes in the ability of campaigns or media to persuade voters.