1.1 Perceptions of Asia

Asia is vast and varied, its physical contours subject to many different demarcations. For many centuries, European chroniclers considered that Asia started at Constantinople, although over time this boundary was displaced eastwards. In this book, the Asia that we are talking about starts thousands of miles east of the Bosphorus in the flat and densely populated Indus and Gangetic plains of Pakistan and India before traversing the massive and desolate highland spaces of the Himalayas and Tibet, passing into the very diverse topologies of the many Chinese provinces and at its eastern perimeter, the Koreas, before falling into the sea opposite Japan. Beneath China lie the states of Southeast Asia, stretching from Myanmar and Thailand through to the Mekong Basin with Vietnam curled around its outer edge, while further south stretch the elongated archipelagos of Malaysia and then Indonesia, the latter extending far in the direction of the Antipodes. Over this immense terrain, it is scarcely any wonder that disparities in climate, ecology, social and political organisation and culture are so large. Yet in recent decades, there has been a marked tendency to speak as much about regional attributes as those at a national or local level. Indeed, talk of an Asian miracle or the Asian twenty-first century has become a new staple.

Until Vasco da Gama’s voyage to India in 1497–99, European cartography and knowledge had extended no further than western Persia and the Gulf, despite the chronicles of some earlier explorers. Thereafter, as the frontiers of territory and knowledge were pushed back and gradually revealed, later explorers and visitors were often dazzled by the splendour of Asia’s courts and rulers but also the quality of its products, natural and man-made. For example, China’s abilities in science and technology were comparatively advanced.Footnote 1 In 1700, India alone accounted for around a quarter of the world economy and a similar share of the global textile trade. The Chinese economy was only slightly smaller in that year.Footnote 2

Yet, as innovation and growth picked up in western Europe in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the desire to dominate trade elided into a desire to dominate territory and with it came the colonial moment in which most of Asia fell under the direct sway of one or more European power. Despite acute rivalry between those powers and a recognition of the political and strategic differences across dominions, intellectual currents, such as orientalism – a fashion for pooling traits of behaviour and systems of rule – often simply rolled up most of the Asiatic world into a common space, albeit one with attributes that were deemed mostly outmoded, if not reprehensible, and almost always inferior to their European comparators. But even when devoid of colonial condescension, it has not been uncommon for more recent writers to portray Asian government as inherently different from its more western counterparts. For instance, historian Karl Wittfogel argued in the 1950s that the Orient was doomed to despotism due to the pre-eminent need to harness and allocate water resources through the implementation of large-scale public infrastructure works. He also argued that this induced a profound continuity so that, for example, communist rule in China was in many respects similar to earlier systems.Footnote 3

Although such ways of typifying the world have by no means entirely disappeared, more modern narratives about Asia tread a rather different path, balanced once again between marvel at its recent and dramatic successes – not least the massive cumulative growth in income achieved since 1980 – but also the dangers and threats that this resurrection poses to the dominant world order. Those dangers may come from the participation of giant countries such as India and China in global trade and production and the ensuing consequences for workers in the advanced economies of Europe, Japan and North America, but also from the accretion of political and military power that has accompanied economic success. China’s growing nationalist rhetoric and expansive claims to territory and influence in the region have proven, unsurprisingly, to be unsettling. More generally, China’s extraordinary growth in the size of its economy and in the average income of its people has also unleashed dire prophecies of future dominance and threats to American hegemony, in particular.Footnote 4

Whatever the inferences and particular interpretations, it is quite clear that Asia’s re-emergence as a grand regional and, increasingly, global force now focusses interest in ways that could scarcely have been imagined even fifty or so years ago. Then, the dominant narrative was to bemoan the vast amount of entrenched poverty, especially in the Indian subcontinent, as well as the periodic excesses of communist rule, such as the Great Leap Forward and the appalling famine that ensued, in China. Now, it is more about whether Asia’s resurgence will result in a region that rivals either North America or Europe. This rivalry extends way beyond the political to embrace technological and productive capacity, including the ability to innovate.

To begin to address these questions presupposes, of course, that the direction of travel that has been unleashed this past half-century will be sustained and that the foundations of greater prosperity that have been laid prove to be exactly that. Here, there is no single voice among the myriad number of commentators, whether in relation to the future of the region as a whole or at the level of individual countries. Some have suggested that these economies will struggle to attain rich country levels of income because of institutional and other failings that will hold them back. One consequence is likely to be the inability to create large knowledge-intensive sectors of economic activity that are innovative. This notion is sometimes summarised as the middle-income trap. Others point to the ability of some of these countries not only to marshal resources and to create new sectors and activities, but the way that this has been in innovative spaces, such as software and artificial intelligence (AI), that many would have expected to be the domain of the richer world. But whatever the balance of interpretations, politicians and citizens in the region have increasingly adopted a more optimistic tone – including through responses to public opinion surveys – about their futures and the respective places of their economies in the global system, especially in the two giant countries, China and India. Recognition of this weight and dynamic has also been reflected in secondary ways, such as the composition of the G20 or voting rights in international organisations. Perhaps most significantly, it is clear that attempts to address carbon emissions and climate change cannot succeed without Asian action both on the ground and in terms of accepting constraints within the context of international agreements.

1.2 Pillars of Asia’s Resurgence: Commonalities Trump Particularities

Given Asia’s extraordinary renaissance and the resulting recalibration of the world economy, our concern in this book is with understanding whether that resurgence can be expected to retain its vitality so that these countries can continue along a path towards substantially greater wealth and opportunity. To do that requires, of course, that we understand very well how Asia has got to the position that it currently finds itself in and what have become the main characteristics of these economies following decades of rapid expansion. We should also clarify that when talking about Asia in this book, we are primarily concerned with the larger emerging economies of the region. These are indicated in Figure 1.1, where the countries that form the focus of this book are named. Although Japan and the smaller island states – Taiwan and Singapore – are not our main focus, their various experiences post-1945 in the former case and since the 1970s for the latter are, of course, very relevant in understanding the policy models followed by the countries on which we are concentrating. Indeed, it is very clear that South Korea – an economy that has successfully become a high-income economy – based much of its strategy on Japanese post–Second World War experience. And, in turn, China has aimed to pursue policies that have been tried and tested in South Korea. In short, these earlier experiences of development are used to cast light on what has happened – and what is likely to happen – in those economies of Asia that are our main interest.

What is evident is that the various models that have driven Asia’s transformation have been strikingly different from earlier templates of capitalist development that accompanied the ascent of the older rich worlds of Europe and North America. Moreover, despite some major differences within Asia – China and Vietnam (not to forget the current-day anomaly that is North Korea) pursued a Soviet-like path of the planned economy for several decades, something that was not followed in most other countries – there are some surprisingly powerful and common features that cut across differences in political systems, institutional organisation and geography and that also intrude substantially into underlying patterns of economic behaviour and governance.

These common features are centred on the pervasive use of connections – familial, commercial and political. They trump the particularities of countries’ political systems and their associated institutions. Even when countries have made transitions from autocracy to democracy, it is striking how such networks of connections have survived and entrenched themselves. We term this resilient and powerful phenomenon as the connections world. It is in no small measure due to the way in which such connections between businesses, politicians and the state have played out that Asia has been able to achieve so much cumulative growth. But this path comes with its costs, in terms of both how these societies and economies currently function and their potential functioning in the future.

A notable feature of the various Asian capitalisms has been the pivotal role of the state and public policy in driving growth and productivity. The intellectual and practical precursor was post-1945 Japan.Footnote 5 Using state guidance of the economy through industrial policy while mobilising public resources to stimulate selected sectors and activities was an approach that was then explicitly imitated by South Korea, Singapore and Taiwan, among others. Most other countries in the region also relied on a prominent role for the state, along with an active industrial policy, but in ways that generally involved protection of domestic industries and rarely involved the successful nurturing of new activities and sources of productivity growth. In China and Vietnam, the entire economy effectively became subject to the priorities established by government. Not surprisingly, this led to massive inefficiencies but also some remarkable accumulations of productive capacity and knowledge in activities that benefitted from support by government and the related channelling of resources. In almost all instances, the leading role of the state included the establishment of major state-owned enterprises (SOEs) across wide swathes of the respective economies.

The role of an activist state has been widely acknowledged as a driving factor behind Asia’s success. What has been far less widely discussed is the way in which the state and the private sector have interacted and engaged with each other. To our mind, as striking – and undoubtedly more long lasting – has been the way in which many Asian economies have come to be populated by often substantial, highly influential and acquisitive private businesses, many of whom have been, and continue to be, organised in family-owned and -controlled business groups. Business groups are confederations of firms that are bound together in both formal and informal ways, including in many instances through ownership vested in families and dynasties. Ownership and control are often highly opaque, and many business groups suffer from weak governance and oversight. Such entities have tended to benefit from public largesse or preferential access to assets, finance and other sorts of privilege, including of a regulatory variety. Consequently, not only have the boundaries between public and private been difficult to draw but major pockets of private market power and economic concentration – sometimes explicitly fashioned by the actions of the state – have also been created. With this have come networks of economic and political influence that web together politicians, political organisations and business. Such networks have proven very capable of perpetuating themselves even while tolerating some changes in composition and shape. As we shall see later, the consequences of these organisational forms and the networks that underpin them have by no means been unambiguously adverse, but they have often had deleterious effects at both economic and political levels. Those costs have proven difficult to address, not least because their network nature has made them far more able to resist attempts at change.

1.3 Connecting Business and Politics

The connections between politics and business take many forms, and these forms depend in part on the political and institutional arrangements that exist in each country. Even so, there are several, recurring patterns that emerge irrespective of these institutional and other differences, such as the following. One-time public officials commonly choose to move directly into political life, either standing for office or taking up non-elected appointments with clear political dimensions. Similarly, businesspeople very often choose to move explicitly into the political sphere – a wide selection of prime ministers and presidents, such as Nawaz Sharif in Pakistan, the Rajapaksa family in Sri Lanka and a fair number of recent Filipino presidents – are highly visible cases in point. The process also proceeds in a very widespread way at lower levels of the political hierarchy, including at provincial and municipal levels. Although the motives vary significantly, a common motivation is the perceived need to protect, or further, their business interests. In a similar vein, private businesses tend to make financial and other donations to political parties or campaigns – sometimes within the legal limits but often outside those limits. Public officials or politicians may also be shareholders – sometimes openly but more often covertly – in private businesses.

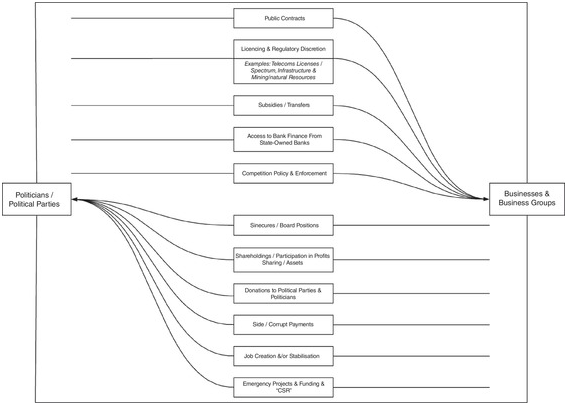

The ties between politics and business materialise in a large and diverse set of ways. Figure 1.2 lists the channels of interaction that run between them. For example, among the more common manifestations are the awarding of public contracts to favoured businesses or business groups by politicians. This may or may not occur with side payments or bribes, but almost always there is some underlying reciprocity or bargain involved. Well-connected companies may also be able to garner access to finance in amounts that may not be warranted or on terms that can be preferential, such as through subsidies or transfers. This is often through the channels of state-owned banks with the consequences commonly including the accumulation of large portfolios of non-performing loans and other impaired assets by those banks. As such, state-owned banks with large market shares have over many decades made lending decisions that do not reflect market-based criteria. This has been a pronounced and hugely recurrent feature in the Indian subcontinent, but also in China.

Private businesses have used connection to politicians and political authority also to influence the regulatory context and, sometimes, even the regulatory framework. Telecoms has, notably, been one area where this has been a major feature. For example, in India, the mobile company that has captured the largest market share – Reliance’s Jio – has deftly attained that position in part through helpful treatment by the regulators, including the terms on which crucial spectrum and operating licenses have been obtained. In the more tightly controlled economies with a dominant Communist Party, party membership has also proven to be a useful way of facilitating support, whether financial, market access or other. Further, in China there is a common pattern among successful companies. Some have started originally as SOEs, but as the state’s share has been diluted over time, former managers and insiders have emerged as the dominant players in the company. The ZTE Corporation is one of the more notable cases in point. Even when a company has been ab initio private, such as Huawei, its founder’s close connections to the Communist Party and the People’s Liberation Army were critical in securing finance from state banks, contracts with public agencies as well as protection from competitors.

The leading new generation companies in China – such as Baidu, Tencent Holdings and Alibaba – also have very strong links to government which may comprise access to finance but, more often, takes the form of protection from competition, including foreign competition. Reciprocation, not surprisingly, takes the form of compliance with government’s preferences and overall objectives. Irrespective of the type of political regime, there is a clear trade-off for connected businesses. When asked by government to take specific actions or finance specific projects, they will always oblige even when it runs counter to their immediate financial interests. Connected businesses are also expected to rise to the occasion at times of national emergencies. It is no accident that across the region, the ravages of COVID-19 have induced many declarations of financial and other commitments by leading businesses to health care or other public agencies. In the Philippines, for example, two of the most powerful business groups – Ayala and First Pacific – made large emergency donations to hospitals and health workers that led the country’s president to declare a cessation of hostilities on his part towards these companies.

Aside from listing the channels of interaction, Figure 1.2 also highlights the way in which these interactions tend to have some reciprocal component, whether of a financial or other nature. It further suggests that some sorts of activity are more prone to reliance on connections. In a nutshell, any activity that needs a license or is subject to a high degree of regulatory interference – such as ports, roads and infrastructure projects as well as telecoms and, quite frequently, media – is far more likely to be marked by close connections between politicians and businesses. Similarly, companies in sectors or locations that have large numbers of employees – the scale effect – tend to have a degree of importance that smaller companies lack, and this commonly attracts the attention of politicians. That is because they can be useful in creating jobs, either for themselves, their friends or relations or more generally by boosting employment at propitious times, such as elections. Conversely, the owners of large enterprises can use the fear of layoffs to extract subsidies or other forms of support from government or government-influenced bodies. For example, the Chinese steel industry has been plagued by overcapacity. In cities, such as Wuhan or in the Northeast of the country, excess employment has consequently emerged. Yet, in a sign of sensitivity to unemployment, limited layoffs have been pushed through with steel companies’ finances being propped up by public money, including through mergers.

Among the most significant manifestation of the influence of connections has been the way in which particular companies or conglomerates have acquired market power and a resulting attenuation of competition. Further, competition agencies have rarely had the independence or clout to rein in market dominance. And once in that position, it is very striking how adept they have proven at entrenching themselves by leveraging connections to erect or raise barriers to entry. Although competition in external markets has been a salient feature, even export sectors have seen multinational enterprises (MNEs) coexist or partner with powerful, local companies often with the support – explicit or implicit – of government.

1.4 The Connections World in Asia: Past and Present

The idea of connections conjures up images of cronyism and corruption. Both sorts of behaviour – bearing in mind that they tend to be intricately related – have certainly been important features and have been amply documented. For instance, it has been recently argued that the current Chinese system is largely based on crony relationships,Footnote 6 many of which have outright corrupt consequences. Consider the case of Liu Zhijun, a former minister in the Chinese government. He was found guilty in 2013 of amassing over $250 million in bribes as well as a huge portfolio of properties and large amounts of foreign currency, not least through the allocation of public contracts. Yet, that level of peculation pales in comparison with the now infamous 1MDB scandal, a government-run strategic development company of that name. In this instance, it is alleged that the then Malaysian Prime Minister – Najib Razak – siphoned off around $700 million into accounts that he controlled, while the main co-conspirator, a Malaysian financier by the name of Jho Low, a man with close ties to China, diverted more than $4.5 billion into opaque financial structures. While the principal players in the scandal were Malaysian, international financial institutions, such as Goldman Sachs, as well as officials from some Arab countries, were also implicated.

Although this scandal seems peculiarly egregious, it is no exaggeration to say that just about every country that we are covering has had in recent times multiple instances of financial scandal resulting from an undesirably close proximity of politicians and business. In the worst instances, it appears that those connections are simply endemic. Of course, these features are by no means particular to Asia. A former president of South Africa – Jacob Zuma – has been accused of multiple illicit and corrupt dealing, including with one family – the Dubai-based Guptas – that facilitated what many have called state capture; the massive subordination of public resources to private interest. Virtually all recent presidents of Peru – as well as many politicians throughout Latin America – have been indicted or convicted for accepting bribes from a major Brazilian construction company – Odebrecht – in return for large public contracts. This sorry litany of greed and the – often illegal – subordination of public resources to private appetites cuts across many countries and regions.

Further, copious as these examples may be, it is important to recognise that there is undoubtedly little new in such behaviour. Some of the protagonists clearly follow in the footsteps of politicians who have conflated public and private interests and translated their position into wealth over the centuries. Nor would it be surprising to find that particular companies or individuals and the state have long been closely – and often unhealthily – entwined. After all, most European powers in the medieval period largely allocated land and then trading rights to individuals or families connected to the ruler. The Venetian Empire, based as it was on trade, was organised around its patricians reserving the main opportunities for investment in long-distance trade as well as its supervision and protection. Even the Arsenal – Europe’s largest hub of industry in the fifteenth century – had exclusive and prescriptive rights assigned to specific patricians.Footnote 7

In yet more accentuated form, the South Sea Company, set up in 1711 as a joint stock company, was allowed to participate in the management of Britain’s national debt and was not only granted trade monopolies but also ensured that an Act was passed which meant that the creation of any other joint stock company would require a royal charter. The bubble associated with its name is emblematic of these moral and economic entanglements. Another British behemoth – the East India Company – came to exemplify the conflation of political power with commercial interest while being beholden only to its shareholders. Following Clive’s victory over the Nawab of Bengal and his French allies at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, the spoils flowing to the East India Company were a staggering £232 million and Clive himself pocketed some £22 million.Footnote 8 After the East India Company’s absorption into the British Empire just over a hundred years later, the colonial system continued to pursue policies that granted explicit preferences for a significant variety of activities, whether of a trading or manufacturing nature, to specified companies or trading groups. Part of that preference was founded on race, resulting in indigenous manufacturers and traders being confined to specific niches or struggling to attain any scale.

The examples mentioned previously are mostly drawn from periods prior to the modern heyday of capitalism when mercantilism was the dominant economic model or where political power was organised around imperial dynasties or weakly representative forms of political organisation. These practices became outmoded in the Western economies as industrialisation and its corporate counterparts, along with more democratic political structures, emerged. The resulting changes included rules for ownership and governance and the emergence of the publicly listed corporation and the oversight that this implies. In a nutshell, industrial capitalism in the West fused with institutional formats, notably the limited liability company, that allowed issuance of equity and at the same time provided protection for shareholders. The birth of the modern corporation surely took somewhat different formats depending on each country’s legal system, but a common element was the extension of ownership to wider circles than family. Although, such innovations by no means solved tensions between ownership and control rights and the alignment of the interests of managers, owners and shareholders, they created a legal and organisational bedrock that is still largely in place to this day. Yet, what is striking is that many of the patterns of behaviour and organisation that existed in these earlier arrangements have either spilled over or adapted to modern times in Asia. This suggests not only some form of deep resilience and capacity to mutate but also a fairly radical departure from many of the changes that have been introduced by industrial capitalism and its successors in the advanced world. Intriguingly, this different model has developed almost contemporaneously with the emergence of challenges to the Western model of wide share ownership and democracy.

As a consequence of this resilience, in Asia companies – especially those that have major market shares – still tend to be dominated by families or dynasties. Moreover, many are maintained as diversified conglomerates; an organisational arrangement that is a comparative rarity in the advanced economies. These specifics are no accident. They result not just from the relatively recent origin of many of these companies in family ownership but also from the way in which such organisational formats are shaped by, and in turn shape, the highly personalised and connections-based worlds of businesses and politics. Rather than stand-alone, externally owned companies with relatively focussed business or sectoral interests, as predominate in most advanced economies, private, usually family-owned, companies tend to be built around networked organisational formats, such as business groups.

Although the widespread presence of family-based businesses and business group structures can in part be traced to issues of trust and institutional limits on what can be contracted (let alone enforced), it is also very much to do with the nexus between business and politics. As noted earlier, businesses court politicians for privileged access to assets or resources, contracts, priority in public procurement and other preferences, not least limitations on competition. At the same time, politicians promote links to business for a variety of reasons that often include securing income or campaign contributions. Politicians also often demand reciprocity from those businesses that benefit. Sometimes, companies have to pay off debts or other obligations incurred by those to whom they are connected.

This complex skein of interactions and reciprocities makes business groups an attractive organisational format for their owners as they provide suitable vehicles for risk sharing, opacity in accounting and transactions and, crucially, for bargaining with politicians. Their scale and complexity can also act as a deterrent to politicians trying to expropriate or dilute their interests if, or when, they fall out of favour or there is some sort of regime change. And, of course, the very perpetuation of these organisational formats is also a reason for why market failures and institutional weaknesses persist over time.

In sum, the connections world in Asia is testimony to the power of networks and the pervasive, resilient, elastic boundaries between governments and businesses. Some of the links between politicians and businesses are clearly corrupt; others hew a more ambiguous line. Public institutions – such as those concerning law, competition and regulation – have tended to bend to the will of entrenched interests or have even failed to materialise. Yet, viewing these relationships simply through the prisms of corrupt practices and cronyism is too simplifying and obscures the benefits as well as the depth and resilience of the wider connections world. It also fails to capture how connections infiltrate ways of doing things throughout the economy, affecting not just how businesses and politicians interact but also how businesses themselves are set up and function. The implications of this are that the connections world has a very substantial impact on the structure of the economy as well as on its productivity. The economic landscape tends to be dominated by collusive and rent-seeking corporations, individuals and their networks. In a nutshell, connections and the networks on which they are based do not just characterise the present but actively ensure that the future will retain some similar features. As we shall argue, while connections may not have inhibited growth and development in the past – and may, indeed, have sometimes actively helped – that is less likely to be the case in the future. Because Asian capitalism is largely not arms-length and impersonal but strongly based on networks, a competitive, popular capitalism has, for the most part, yet to emerge.

1.5 Fallibilities of the Connections World

Will the connections world and the shapes of the capitalism that it has spawned be sustainable, both economically and politically? Will the power of entrenched networks subvert dynamic processes of innovation and reinvigoration? Will these systems have sufficient adaptability to shocks to retain support from their populations? Moreover, can this broad model of capitalism prove sufficiently dynamic to engage with the sorts of powerful and disruptive challenges that are already present, perhaps most notably those emanating from technological change? These are the questions that this book addresses. But before going further, it is time to delineate briefly some of the main risks associated with the connections world before providing in the coming chapters a more detailed examination. At the end of the book, we return to these risks, this time with a view to identifying the policies that could address the problems that we have identified.

The connections world, effective and resilient as it has been, nevertheless contains multiple fallibilities, many of which are, in a variety of ways, already visible and some of which are likely to pose substantive risks, possibly of a systemic nature, in the future.

The first fallibility flows directly from the inherent nature of the connections world with its concentrations of influence, power and economic benefits in the hands of relatively small numbers of networked persons, families and, even, dynasties. Important manifestations are the high – and often growing – levels of inequality in both income and wealth, let alone frequent manifestations of corruption. Without a shift to a more open, popular and inclusive form of capitalism, these inequalities will prove debilitating and affect stability.

The second concerns the consequences of the market power and restraints on competition, especially in domestic markets, that flow from the primacy of connections and the resulting weakness of regulatory and other institutions. In most Asian contexts, there is plenty of evidence that connected parties, often based in business groups, work very hard to ensure that they are ‘better’ connected than others. There is often acute competition among connected entities. Why then does this not necessarily result in undermining the system? The answer is that most of this competition results in the reallocation of rents and privileges rather than their elimination or reduction. As such, the aim of this competition is not really to open up markets or induce the entry of new players, quite the contrary. Barriers are set up against new entrants and disruptors. The principal aim is to redistribute the cake between the incumbents. Furthermore, because success commonly stems from connections rather than education or effort, this provides weak foundations for growth that is based on productivity, creativity and innovation. In some cases, this has actively deterred inward investment or the return of individuals with new ideas and skills from abroad.

The third concerns an important corollary of the connections world; its ability or otherwise to create jobs and achieve an essential – probably the primary – aim of societies; the creation of sufficient and productive employment. It is not the case that it does not create jobs; it does. Many are indeed good jobs, well paid and productive. But the absolute number still remains quite small. The informal economy continues to account for a large – often the largest – share of employment in the Asian economies. Moreover, politicians also often ensure that connected companies, and particularly SOEs, are funnels through which employment, including job creation sensitive to the political cycle, is maintained. The broader implication of this is that much of the necessary employment creation occurs in the informal economy where fragility and low pay are pervasive features. Most troublingly, connected companies are also an important reason for why the formal economy has failed to raise its share of total employment in a major way over time.

The fourth fallibility is closely related. Because padding employment in connected companies and/or SOEs is the dominant mechanism for dealing with adverse economic developments or shocks, the scope for introducing more efficient – and ultimately longer lasting – policies has been far more limited than is desirable. It is striking that as China’s average incomes have risen, dealing with individual or households’ employment and income risk through creating mechanisms of social insurance has been avoided. Part of the reason for this is that politicians still prefer to rely on mechanisms that they believe are more responsive to their demands and interests. As a consequence, using SOEs and connected companies to cushion labour market risk has remained the dominant approach to the problem. Further, faced with rapid technological change (such as advances in AI) and significant exposure to international markets and value chains, Asian companies have faced pressure to shift more towards capital-intensive production. Absent any effective social insurance, such a shift would imply that citizens in the future will carry significantly higher risk themselves. Moreover, although technological advances can offer the opportunity for new players to challenge incumbents, for this to materialise will require that the space for competition does not get squeezed out by the latter.

The final fallibility concerns political systems and their associated institutions. While, in principle, elections and political turnover are the main ways in which democracies handle change, a significant number of Asian economies are either autocracies or heavily managed democracies. In these instances, the risk of competition among the connected spilling into disruptive turmoil is far greater, if only because of the difficulties in resetting the political equilibrium. Such risks, as a result, are potentially destabilising for both the Chinese and Vietnamese political systems and their associated economic configurations. The lack of adaptability has – both in Asia and elsewhere – been a prelude to disorderly, sometimes chaotic, responses to pressures.

These fallibilities by no means sound the death knell of future growth. Yet, they do highlight that while the connections world has played a central part in Asian success, it also bears the seeds of major challenges in the future. Asian economic performance in the coming decades will depend on how countries respond to these challenges and their capacity for adaptation. In the final chapter, we ask how policies could begin to address some of the fallibilities that we have identified. Whilst clearly not straightforward – due to the entrenched behaviour and advantages of the connected – we suggest specific changes that could be put in place to counter the market power accumulated by business groups along with the allied consequences of the limited creation of productive jobs, let alone the exacerbated levels of inequality that have emerged. Such changes could also radically influence the governance of companies and in so doing achieve far higher levels of transparency and accountability. Moreover, it could create space for the introduction of more modern systems of risk management, both for workers and companies. This would limit the need to rely on connections and reciprocity-based deals that characterises the present-day connections world.

1.6 A Guide to the Coming Chapters

In the next chapter, we provide a building block for the analysis which follows. We start by setting the context, looking at Asia’s economic ascent and the factors behind it. That ascent has shifted its share of the world economy from 9 per cent to nearly 40 per cent over the last half-century and seen income levels and living standards rise dramatically. We use data on the economy, political systems and institutions from a variety of sources to chart the progress of Asian countries since the 1970s. What becomes clear is that despite this ascent, the gap between incomes in most of Asia and those in the rich world are still huge so that there is considerable convergence yet to be achieved. Moreover, productivity levels are but a fraction on average of those in the economies of Europe and North America. For these reasons, the ascent – though steep – has realistically only taken Asia to a staging post for any future drive to the peak. Further, growth has been mainly driven by population increase and investment, financed by high savings and, particularly in East Asia, export-led integration into global value chains (GVCs). Yet, some of these factors are now less favourable: the demographic dividend is being exhausted and globalisation is being challenged, a process being accelerated by COVID-19. In addition, whilst poverty has declined, economic insecurity remains ubiquitous and inequality has risen steeply. Although the quality of formal institutions has often improved, non-market supporting informal institutions remain significant almost everywhere and many countries remain wedded to autocracy or forms of ‘managed’ democracy. In short, for Asia to go from the foothills to the summit will require not only a shift away from the extensive growth model but also a profound re-evaluation of the organisational, institutional and other arrangements currently in place.

Chapter 3 turns explicitly to the way in which Asia’s connections world is configured, highlighting the extraordinarily pervasive nature of ties between businesses and politics and the networks on which they are based. These networks derive advantage from their mutual – often reciprocal – relationships. Most of these relationships are strongly transactional but they also affect how individuals and companies actually organise themselves to achieve some of these goals. For example, the institutional framework for private companies is often designed with a central – even primary – purpose of leveraging resources and assets, as well as gaining advantage, whether in relation to the regulator or with regard to other actual or potential competitors.

The nature of these connections and their associated networks is initially described using information on politicians, political parties and various types of businesses for each of the countries on which we are concentrating. We rely on a novel dataset that puts together comprehensive information on politically exposed persons and institutions in all of Asia. This information allows us to map the various networks at the level of each country. These maps highlight significant differences between countries, mainly resulting from the variation in political systems and related institutions. Although these maps provide a useful starting point, to understand how connections actually play out requires using detailed cases and examples from across Asia. Once done, we find that that whatever the local variation, these webs of connections bind together with common purpose. Moreover, leveraging connections for mutual benefit has often delivered large and very enduring benefits that have proven resistant to changes of government or even political regime. Indeed, in today’s Asian democracies, many large, sometimes dominant, businesses have been built on the connections established in earlier autocratic eras. Perhaps most importantly, these webs of connections have created a system of behaviour that has become increasingly entrenched whether in the richer economies, such as South Korea, or in some of the poorer ones, such as Pakistan. Such behaviours also cut across political systems.

The connections world not only influences in important ways how businesses organise themselves but also how they function. Chapter 4 examines a central, indeed a defining, feature of the Asian economies: family-based and founder-manager business groups. These comprise networks of firms bound together through formal and informal ownership links, with a family or dynasty usually at their heart. Some are truly massive by global standards; most are highly diversified, and they are often the dominant players in their home country across a wide variety of industries.

What we find is that business groups are a uniquely well-suited format for doing business in the connections world. Opaque cross-holdings and pyramids of stocks ensure that families can exert effective control, even if their actual shareholdings are relatively small. These arrangements also open up endless opportunities for playing reciprocity games with politicians, civil servants and members of other oligarchic dynasties. Although there are examples of efficient and well-run business groups, most do not conform to this characterisation. Furthermore, while it has often been argued that business groups are a response to institutional and market weaknesses – for example in relation to securing finance – they have not faded with growth and the improvement in institutions. Rather, business groups have become more entrenched in Asia over time.

Just what has happened is shown by our measure of economic prevalence. This indicates the impact of the largest business groups on an economy in terms of their market power. In many Asian economies, half a dozen or fewer business groups generate revenues which constitute the majority of the country’s economic activity. Such concentrated ownership has also had an impact on extreme wealth. The growth in the number of billionaires has been quite staggering – from only 47 in 2000 to 719 twenty years later! This entrenchment of economic power and wealth underpins the operation, and reflects the consequences, of the connections world.

With business groups and connections playing such a major role throughout Asia, what are the implications for making the transition to growth based on technological advance and innovation? In Chapter 5, we explore how these economies sit globally in terms of innovation. What transpires is that most Asian economies are not very innovative by international standards. Most perform in line with what could be expected for their level of development. Asian economies mostly obtain their technological innovation from abroad through foreign direct investment (FDI) or by domestic firms obtaining these technologies in nefarious ways from licenses to imitation. However, despite very rapid growth – and with the exception of China – the attraction of FDI by the Asian economies has actually been distinctly lacklustre. Part of this is the consequence of the connections world. Politicians and business groups have been mutually supportive in erecting barriers to entry by new firms, be they from abroad through FDI, or from domestic entrepreneurs trying to disrupt domestic incumbents. As a result, most innovation has been within business groups or by new firms entering new sectors where existing business groups were absent or had not managed to erect unscalable entry barriers.

However, even if most Asian economies will not be able to base their growth on their own innovations in the near future, there are three countries which have developed a base for innovation: China, India and South Korea. In each, long-standing efforts to construct an environment favourable to innovation, including policies for education, science and technology, as well as encouraging returning migrants with knowledge, are beginning to reap dividends. Each has adopted a rather different model, generally centred in business groups. In India, this has mostly happened where the dead hand of state regulation and licensing has been weakest. In South Korea, innovation-driven growth is based on a compact that knits together the massive, incumbent business groups and the state. In China – with its aspirations for being a global technology leader – the onus has shifted to notionally private companies spearheading the effort but with substantial support – financial and otherwise, along with increasingly vigilant – not to say, intrusive – oversight from the autocratic state. Yet, even despite these achievements, the power and influence of the connections world in these three countries also remains a serious brake on their ability to innovate in the future.

Although much of Asia’s success in recent decades has been focused on growth, governments actually worry just as much about the amount of employment that has been created. Presently, just to keep the share of employment stable, Asia needs to generate over a million jobs a month. In Chapter 6 we examine how well these goals have been achieved and the forms of job creation that have resulted. We show that, even when employment targets in aggregate have been achieved, the ways in which that has occurred mostly fly in the face of governments’ declared objectives. Specifically, most employment remains in the unorganised or informal parts of the economy. Those jobs are generally fragile, low wage and low productivity. Although public sector employment is often quite high, the reduced enthusiasm for SOEs throughout Asia has meant that ‘good jobs’ are now mostly to be found in the private sector. For sure, many of the business groups that figure in the connections world also create productive and relatively well-remunerated jobs. As do other large companies, including foreign-owned ones. The problem, however, is that the organised or formal private sector is of limited size and lacks the ability, or even willingness, to create substantially increased numbers of jobs. In the connections world, business groups and other established companies may compete with each other, but the scale of entry and exit, as well as rivalry, is held in check. This has led to a pronounced polarity between working conditions, compensation and productivity in the numerically dominant informal firms compared to the relatively small number of larger formal ones. Boosting formality and, with it, productivity – a clarion call of almost all Asian governments for decades – has largely failed to materialise.

The entrenchment of the connections world has also helped ensure that little or no progress has been made in bringing in more effective responses to employment risk. In this world, neither government nor companies have a strong interest in promoting arms-length methods of dealing with such risk. They prefer, rather, to rely on discretion. Jobs can be created, and their destruction tempered, as a result of interactions or even haggling between politicians and employers. The bulk of workers, namely those who function in the informal economy, are de facto excluded. And the modernisation of welfare systems – now feasible given the income levels of China, Malaysia and others – remains stalled.

Our final chapter places our argument in a longer perspective. The aim is not to make prognostications about the future of each of these countries. But it is to say something about how the characteristics of today will affect the paths of Asian growth and development tomorrow and, in particular, to draw conclusions about what will be the impact of the connections world on those prospects. Despite many similarities, the connections worlds still have many local features, dynamics and, ultimately, prospects. Even so, set against the tasks of climbing the steep income mountain towards convergence with the rich world and doing so in ways that do not necessarily confer disproportionate rewards on limited groups of people and institutions, the connections world imposes some quite common constraints.

One is the ability of powerful businesses and families to entrench themselves by virtue of their connections to government and/or politicians. This is as true in China as it is in India. The mutual benefits of the current system for politicians and business owners mean that neither side has much, if any, incentive to move away from the current arrangements. Hence, limiting competition and suppressing the dynamic processes of entry and exit, particularly in the formal or organised part of the economies, will be hard to shift. We propose a series of measures and policies aimed at improving transparency and governance more generally, whether in firms, capital markets or in relation to government and politicians. Because marginal changes pursued through existing competition or regulatory authorities are most likely not to be credible or effective, we propose a set of more radical measures to disrupt and refashion the connections world that, ideally, should be taken simultaneously. Among them are the use of prohibitions on cross-holdings and other business group practices, as well as the application of tax reforms, including the introduction of inheritance taxes, that can begin to shift the balance of advantage away from the business group format. In addition, we propose a series of changes aimed at boosting competition and ultimately making competition policy more effective. At the same time, improving political transparency and oversight, so as to limit the incentives for politicians to perpetuate the connections world will be essential.

Finally, we focus on the main pressure points to which the connections world is, and will be, subject. As signalled earlier, these are the ability, or otherwise, to generate innovation through reliance on new entrants and an effective entrepreneurial ecosystem. With a few notable exceptions, this has so far proven elusive, not least because of the entrenched market power of business groups and their cossetting by government.

Then there is the constant pressure to create sufficient jobs. Not only has the connections world been actually quite poor at creating productive, ‘good’ jobs but technological change is beginning to bite and will affect both the level and type of employment. In some countries – notably China – those changes have paradoxically been encouraged with a view to gaining strategic advantage in AI. But whatever the context, the reality is that if stuck with their current arrangements, the Asian economies will struggle to satisfy the demand for jobs. That will likely mean further increases in the size of the informal economy. This will doubtless be accompanied by continued reliance on subsidies to preserve some part of employment in the formal economy, rather than the creation of better systems for managing employment risk.

An additional pressure point comes from ballooning inequality of income and wealth. High inequality tends to be associated with economic underperformance let alone susceptibility to political turmoil. This is especially problematic with autocracies. While progressive taxes and greater coverage can help mollify inequality, that has to be led by effective targeting of the sources of that inequality, not least the features of the connections world that this book will have described.

Before we get going, let us emphasise that Asia’s ascent – and the wider ripples that it has induced across a broad swathe of emerging economies – has been testimony to a remarkable marshalling of resources and, in some instances, highly effective public policy. Many households have been pulled out of poverty and income gains have been substantial, if unequal. These are huge achievements. But it has also revealed fallibilities, not least the accretion of market power and an unhealthily close relationship between business and politicians. What we have termed the Asian connections world has proven very effective in limiting possible encroachments on the privileges that it has secured. However, the organisational forms of this model of capitalism – notably business groups and state-owned firms – exhibit features that betray not only their purpose but also their weaknesses.