Ben Teensma (1932) studied Spanish language and culture at the University of Utrecht, in the Netherlands. His PhD was on Portuguese language and culture, with an innovative and challenging literary and historiographical reading entitled Francisco Manuel de Melo: inventário general de sus ideas (public defence 1966). His passion for Portuguese literature and writers led him to the University of Groningen where he was a lecturer of Portuguese and responsible for the Portuguese and Spanish section of the University Library. Later in his career, he joined the Department of Latin American Languages and Cultures (TCLA) at Leiden University, where, as a Senior Lecturer, he dedicated his life to teaching Portuguese and publishing broadly about the history of Brazil and, most emphatically, the history of its indigenous populations. He was simultaneously an activist for the rights of dispossessed Amerindian populations in Brazil under different regimes and their right to land, education, and healthcare. He combined many of his academic trips to universities in the Brazilian sertão with visits to his long-time friends in indigenous communities, a tradition he kept well into his eighties. He remains a philologist at heart, passionate about Brazilian literature from the nineteenth and early twentieth century, and a vocal supporter of indigenous rights and historical memory in the modern world.

Thank you Ben for accepting to talk to Itinerario about your life story which has so informed your academic career and the way you look at academic work about the history of local (indigenous) communities. Perhaps you can tell us a bit about your origins?

I was born on a plantation (called onderneming in Dutch) in the Deli agricultural region, on the island of Sumatra, on 7 March 1932. At the time, still called the Dutch Indies, currently Indonesia. My parents were Dutch and we spoke Dutch at home (my parents, my sister, and I). The majority of the people in our surroundings were Indonesian and spoke Malay. So, I grew up speaking Dutch with my family and Malay with everyone else. I transitioned effortlessly from speaking one language to the other. This ability to speak different languages was of great help after the Japanese invasion of 1942 and my subsequent internment in a camp where Malay and Japanese were essential to survive. I still whisper and speak in Malay with my beloved dogs (as I have no children) and all my emotional communication is still easier in Malay.

How was it growing up in a tropical plantation-society?

My father had studied in Wageningen (the Technical Agricultural University of the Netherlands) and was an agricultural engineer specializing in tropical agriculture. He was employed by the Handelsvereniging Amsterdam trading company, which was a major operator of plantations in the Dutch Indies. We lived on a large plantation named Dolok Sinoemba, in a house for European employees. All houses for Europeans looked the same. They were built on stone pillars, half a meter high. We, the children, could crawl under the houses, which was exciting because there was loose sand underneath, with scorpions and anthills. As soon as an ant fell into one of the pits, the scorpion would pounce on it to eat it. This was the children's entertainment. The houses were built on rows of pillars to keep them snake-free. Furthermore, the plantation had part of the ground covered to keep it shaded. That means that crawling plants abounded where rats and mice could hide. They always attracted snakes that came to eat them.

You entered the house through a staircase of six or seven steps. Then you entered a large covered front porch, and behind that, running through the middle of the house, was a corridor. On either side were the rooms: the living room, the dining room, and the bedrooms (for the parents and for the children). At the end of the long corridor, there were three or four steps going down again, and you would come to the back veranda, called the kakilima in Malay. The kakilima serviced the rooms located at the back: the bathroom, the kitchen, the staff quarters (because we had servants and they all had their own in-house accommodation). The kokki (cook), the jongos (boy), and the toekang ajer (water carrier) lived with us. Since there were no water pipes or electricity, the toekang ajer got the water through a tanker pulled by oxen that distributed the water from the railway line to the plantation and from there, the water carrier, using two petroleum cans on either side of a yoke, did nothing else but walk up and down, many times a day, to attend to the need for water in the house. He would deposit the water in a mandibak (water tank), from which we could bathe, using a gajong (dipper with which you could pour water over your head). The bathroom had a cement floor. For illumination, we used lampu templek (petroleum lamps with a kind of chimney on them). The jongos was responsible for the lampu templek and had to ensure there was enough kerosene to keep them alight.

Next to the house was the pondok. The pondok were large sheds meant for the Indonesian workers. These sheds had galleries with small rooms where the so-called ‘coolies’ lived. These were also the words that were used at the time with all the pejorative connotations that they had and still have.

The plantation had an administration compound. That was the central square, which was a few kilometres away from our home. At that compound were the service quarters. The head administrator lived there. Next to it was the factory that crushed the oil palm nuts, converting them into oil. The school for Dutch and European children was located there as well.

The majority of the people in the plantation spoke Indonesian or Malay. That is the reason why Dutch children like me who were brought up in these plantations still have a creole-like accent in Dutch, even now in my nineties. We are, however, fading away and with us this variation in the Dutch language.

What did your average day look like as a child?

We woke up at the crack of dawn. I am still an early riser because you get used to it. We were picked up by buses that ran at fixed times to go to school at the compound. There were two teachers and two classes in two different classrooms. Classes one through six ran simultaneously and teachers had a total of about fifty children under their care. However, after the fourth year you were not considered a young child and therefore you had to be taken by the water carrier, on the back of a bicycle, to the main road, where the bus stopped to pick us up. In the middle of the afternoon, you would go back again by bus and be dropped off at the same spot and picked up again by the water carrier. I keep saying the water carrier, but he was not anonymous. Not to me. His name was Damir. Damir was nice and friendly and a really good man. I was very fond of Damir.

What did you learn in school?

It was European primary education. You learned Dutch, arithmetic, geography, and history. The teachers were hired by the company, as the company was a broad concept. Next to the plantation and the oil factory were the school and a hospital as well, with a doctor and nursing personnel. The hospital was for the Europeans, however, the personnel of the hospital also treated the ‘coolies’ when necessary, but in their quarters or at the place where they worked.

Besides Europeans, what other people did you have contact with?

The household personnel like Damir were Indonesians. We lived on the east coast of Sumatra and those were the Batak lands. A bit further north lies Aceh. The people working and living at our house were Indonesians from the Batak lands, located around Lake Toba.

Among the ‘coolies’ that slept in the pondok were also Chinese, as the word ‘coolie’ is a Chinese word.

However, at some point, we moved from the East Coast of Sumatra and went to the West Coast, to the hinterlands of Padang, near Bukittinggi, at the time called Fort de Kock. There, my father went to work on a plantation called Ofir (as in the Bible, the land where King Solomon sent his sailors to fetch gold). But in modern times, the gold there was palm oil.

Gold is also associated with the word samatra, meaning gold, and people thought that the mountain behind the plantation, also called Ofir, was rich in mineral resources. But of course, the word ofir meant nothing to the Indonesians, who pronounced it as oebier or opeer. Furthermore, they had no association with the biblical context, although the place was valuable to them as well as a place of historical memories of gold extraction. During the time when there was gold in the mountain, the Indonesians called the river that streamed down the mountain Passaman, with the syllable sam – meaning gold – being identical in the earlier name Samatra (Sumatra). I remember that on the banks of the river there were always Indonesian women, with very long hair, tied up in a konde (bun) at the back. If they let it down, it could reach down to their knees. They would then stand with their legs wide apart in the river, and let their hair flutter for a while. When it dried, they could brush it out and the gold dust fell onto a mat or onto a piece of paper. Men could not do that.

But this life came to halt in 1942.

The day after my tenth birthday, 8 March 1942, the Royal Dutch Indies Army (KNIL) surrendered to Japan. The Japanese held out until September 1945 and in that year atomic bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and their time was over.

What happened to you and your family after the invasion?

Less than one month after the arrival of the Japanese, they took the women and the children first to the compound of a Christian mission in Fort de Kock (later named Bukittinggi) and then to the penitentiary in Padang. At the same time, the men built the women's camp in Bangkinang, in the very centre of the island. When it was completed, two or three months later, we were sent to Bangkinang. My father was forced to work like all his colleagues. There were around one thousand men in the old factory, turned into a men's camp and two and half thousand in the women's camp the male prisoners had built, among women and children.

The Japanese internment camps were close to Bangkinang, off Pakanbaroe. In Pakanbaroe there was an airport and the town was accessible by river for large ships. That is where the Japanese kept the European prisoners of war from the KNIL. They wanted to use the KNIL as forced labour to build a railway from there to Sawahlunto to better access the coal mines. The coal mines had a railway to the West Coast and Pakanbaroe had a seaport, at the mouth of the river Siak (on the East Coast). So, the Japanese wanted an intermediate railway between the mines and the port. Because the Allies were everywhere at sea with their torpedo boats, they made shipping impossible around the island. Land routes and the railways became important. So, the KNIL prisoners of war worked on the railway between the coal mines and the coast and the Europeans worked on the intermediate segment between the former and Pakanbaroe. These works became known as the infamous Pakanbaroe railway.

In the women's camp, the barracks were more or less identical to the sheds of the workers on the plantations. The camps had Indonesian guards who lived on site. There were also Indonesian police officers who had been deployed by the Japanese alongside the guards. We could talk to the Indonesian guards in Malay and they were often favourable to us, even when at the service of the Japanese.

When I was twelve or thirteen, I moved to the men's camp and stayed there for two and half to three years. We were allowed to gather firewood at a nearby former rubber plantation. We felled and cut the rubber trees into pieces. This was the work for the children. We had to cut the rubber logs finely because we used it as firewood for cooking in little portable stoves that we called angelo. I still have the machete I used to cut the rubber trees with. I acquired that machete when I traded it secretly against my shirt with an Indonesian road worker, as the guards and the locals had a great shortage of textiles.

But that means that your family was kept separate.

Yes, we were immediately separated. My father on one side, while my mother, my sister, and I remained together. Boys who were about eleven or twelve years old had to be transferred from the women's camp to the men's camp. That was the rule. So, when that time came, we had to go through that separation. But at those moments, we thought about the many boys whose fathers were soldiers and were not at the men's camp but working on the Pakanbaroe or on the Burma railway. They were alone, while we at least knew that we would leave our mothers but go to meet our fathers. Those other boys were placed under a sort of guardianship in the camp. Our fathers would look after them as well.

The day I left the women's camp, I wore a shirt with short sleeves. My mother had made a fold in it. In that fold, she had placed a tiny, folded note. I was not allowed to tell or show it to anyone. Nobody found out either. I gave the note to my dad, and in it, my mom probably wrote all sorts of things about who I was and what she thought I needed extra care for. After all that time, I was still able to recognize my father as soon as I entered the men's camp.

What my parents did not know is that the women's and the men's camps were about two or three kilometres apart and at a walking distance. There was a river in between, with a little bridge. However, there was no contact possible between both camps.

The possible contact with the outside world entailed smuggling. And my dad started to take part in smuggling as well. In the men's camp, there was the possibility of working outside the camp, in a rice huller site. There, you had the chance to make deals with the Indonesians. My father smuggled mostly small green peas or raw peanuts, that he paid with money and textiles that were by then not being produced anymore. He would return from work with small bags under his armpits or in his belt. The peas and the peanuts were extra nutrition (fat, vitamins) and ideal to add to the very poor sago porridge we got from the Japanese. They were worth more than gold! One pea or one peanut a day kept you going.

What were the main differences between the women's and the men's camp?

A male society and a female society. Female societies are always chatter, quarrel, warmongering. Women quarrelled with- and over the children all the time. We also had people from very different backgrounds. There was a lady from Madagascar with a French colonial background and another one from Martinique. She spoke French and she had a son named Raoul. One time she was very upset, and she called Raoul and told him, ‘Whet your parang (machete). I will beat that ugly witch's face to a pulp,’ referring to one of the Kamsma sisters, who originated from Rotterdam and had been primary school teachers and very strict. This happens when a lot of people live in very close quarters.

The men's camp was much calmer. Women were probably more emotional because they had to watch over their small children. When there were fights between the children or between the women, they escalated quickly. Moreover, everyone was irritated because the camp was filthy and there were dirty animals everywhere. And they were hungry.

The inner camp was guarded by Indonesians. Then you had Japanese guards, but we hardly ever saw them. For each camp, right next to the gate, there was a small office building. Inside were the lower-ranking military officers who held the command at the time. That was always a Japanese. The Japanese were not always hostile or difficult. It is just that we could not talk to them. But the Japanese, in turn, and at times, could be nice, friendly, and humane. There was less problems with the Indonesians. But when two young Japanese (soldiers) had to patrol amidst a crowd of two and half thousand women and children, they probably felt highly threatened. They were nervous and on edge and were easily provoked to hit. As soon as they felt threatened, their restraints were off. And they were very young and conscripted into the army. Furthermore, Japanese culture also forced them to blindly obey their Japanese commanders. But those Japanese young soldiers, they were also people.

You seem to be able to bring some understanding for the Japanese young soldiers. Why?

Let me tell you why. My mother, my sister, and I were transported from the coastal area of Sumatra to the inland, to Bangkinang, on Japanese trucks. Each truck took forty to fifty people, who sat on the back. For each truck, there were two drivers, both Japanese, in the front seat. They drove us into the mountains, through zigzag roads, with very short breaks for the women and children to pee of between a quarter and half hour. I have always been very prone to motion sickness, so I vomited my guts out. During one of the pee breaks, I stood on the roadside like a damn, sick worm, vomiting. The Japanese driver and his mate took pity on me. They grabbed me by the collar of my shirt, and put me between them, on the front seat of that truck. My mother was shocked to death and screamed, but those Japanese men were only humane and friendly to me. I was allowed to sit between them, I was given water from their canteen, and they took care of me like fathers to their children. And I will never forget that. The ‘Jap’ was the enemy. But the same ‘Jap’ could also be friendly. But the language barrier made us stand at a long distance of each other's humanity.

I never felt the enmity of the Indonesians, perhaps because we could speak the same language. Communicating in Malay, we were able to speak with each other in equal terms. There were around sixty of so Indonesian military, former police personnel of the Dutch government, in the camp. They still wore their old Dutch police uniforms. We were not afraid of them at all. There were also half-Indonesian ladies in that camp who flirted with them, just below the guard towers. Those young ladies and young men probably were spending the best years of their lives in that camp.

What was the moment in the women's camp that you remember the most?

There was a summer evening, when we returned from gathering firewood. I was walking alongside an Indonesian policeman who I knew well. His duty was supervising the children's return to the camp. It was a beautiful evening and everything smelled of peace and loveliness and coziness and goodness, like only summer evenings in Sumatra can offer. The Indonesian policeman saw my bewilderment and allowed all children to continue to the camp but took me off the path and showed me the beautiful spring than ran down the mountain, behind the camp. The sound was astounding and the smell of summer everywhere. At that moment, I was fundamentally happy. Just after sundown, he took me back to the front gate, where my mother was standing very worried. I told her about what had happened and how thankful I was. She was totally out of her mind and promptly reported what she called ‘the incident’ to the camp management. The camp manager was a European lady, and she reported it immediately to the Japanese commander, who promptly summoned all Indonesian guards, made them stand in a long line, and I had to walk past to point out who had taken me off path. I knew, at twelve years old, that if I would point him out, he would be slaughtered. So, I decided then that I would not recognize him. I refused to single him out. He was a good person. He had been kind and humane to me. He had treated me in a fatherly way and, because of my mother's fears, I was being forced to single him out for the Japanese. So, I did not identify him. As a punishment, I was put in the office of the Japanese gate commander. There was a kind of trash can, a stool with four legs. It was turned over and I had to stand between those four legs and wait there for a long time until I would talk.

A bit later, you moved to the men's camp. How was living there?

It was less emotional and quieter. My dad was a kind man. I had marched for three kilometres, with other boys of twelve, from the women's camp to the men's camp. Even after three years in the camp, we could recognize each other. In the men's camp, young boys had tasks like insect and pest control (mostly mice and rats). However, we were not allowed to catch the rats. That was an adult's job. Besides, they were too cunning for us. When caught, the rats were taken to a special cooking team working at the hospital, where they were used to make rat broth for the sick. It was a taboo speaking of the rat broth, but many in the hospital were saved by it.

There were also cockroaches, mosquitoes, flies, lice. But the worse was the thousands of flies that gathered around the coffins after people died. The younger boys were then tasked with catching the flies. We would catch the flies from behind, then catch them, put then in a box and when there were about twenty or so, we received a small chili pepper in the box and kept it to eat later. That was a treat. It was a kind of candy.

Besides all the tasks, did you receive schooling in the camp?

There were many Roman Catholic clergymen in the camp, from different religious orders. Many of the priests had been teachers of some sort before the Japanese arrived. So, they were the teachers at the men's camp. At the women's camp, we had the primary school teachers from Fort de Kock, who were nuns. There were even school reports in the camps. Mrs Breemer and Brother Ernestus also taught in the camps. Mrs Breemer awarded me eight for Dutch, eight for algebra, seven for geography, seven for history. However, in the men's camp, under Brother Ernestus, all my marks went up to eights and nines.Footnote 1 We did not have books, pencils or paper, so we worked from memory and we got little slates that we made of scrap wood that came from the ever busy coffin-factory on camp. We wrote on those slates with pointed pieces of bamboo with a small stub that lasted forever, as we were not able to get pencils. When the slate was full, you went back to the workshop and a layer was planned off and then you had a clean slate again. Education stopped though at about seventeen or eighteen. At that point, you were not considered a child anymore. By then, you had to take to work as an adult. Education was important and the leadership of the camps made sure we kept learning. It was also a good way to keep us busy and mentally fit. Idleness is condemning people to wither and die.

When did you know that the war was over?

The Japanese barracks were next to a stream, upstream, next to the camp. In that camp was a kitchen only for the Japanese. The food that was delivered there had been packaged and this was done in newspapers. Those were both Japanese and Indonesian newspapers where vegetables and meats were wrapped. After unpacking, the newspapers were discarded onto the river. The newspapers flowed downstream. On the bend of the river, there was an observation point to fish out the remnants of the newspapers and that is how we got snap shots of the news once in a while. The younger children were particularly good at it. Many of the older men could read Indonesian, while there was also Mr Meijer who could read Japanese. There was a pigeon loft in the old factory with an attic reserved for Mr Meijer, where he secretly received and puzzled the scraps for translation. Note that these were scraps, but we could recognize the geographical names, and we could see that the Allies were coming via the Pacific towards New Guinea. Every time we saw a new geographical name, we noticed that they were getting closer. When Mr Meijer was done with the translations, Mr Ebeling, a man with a big red beard, would come into the sheds at night, stand under a petroleum lamp and convey the translated news.

And at some point the war is over. How did you discover that? Did the Japanese leave the camp?

No, the Japanese did not leave and the camp was never empty. We were far too removed from civilization. Transport had to be arranged and foraging had to be taken care of. The foraging was largely done by the Chinese, who were on our side, but they could only do that after the war. However, at some point, we got double portions of rice. That is when we got very suspicious, gossip and rumours ran wild up to the point that the camp commander had to stand on a table and declare in Malay - he could speak a bit of Malay – habis perang (the war is over). An interpreter translated afterwards into Indonesian. He continued, ‘I hope you continue to behave exemplary. For the time being, I am still your commander.’ Notwithstanding the words, we were given more food, I think, so that we would not rebel. At some point, the Chinese showed tremendous solidarity with us and sent us a cow to be slaughtered to feed all prisoners. Mr Gosens, who had owned a butcher shop in Padang before the war, knew how to kill the cow and clean the meat.

When did the Japanese leave?

The Japanese were initially ordered by the Allies to maintain law and order in the camp. In other words, they kept their jobs, but the power dynamics changed and our fear for them as enemies disappeared. At that point, they were defeated. There was a moment in the women's camp, when ‘habis perang’ was announced, a woman called Miss De Groot stood up from the crowd, marched towards a Japanese officer and slapped him in the face. That was not appreciated, not even by all the other Dutch women in the camp. This was not done.

And who liberated Sumatra?

The English did, because Sumatra was closer to the former British territories. The Americans stayed Eastwards because their main centre of operations had been Midway. The wife of the British supreme commander of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Lady Mountbatten, visited the camps and I have a vivid memory of her entry into our camp. At some point the guarding between the women's and the men's camp withered and we were able to cross. It took a bit for liberation to arrive in the remote inland, so we walked around the camp, we swam in the river and then we would return to the camp. We still lived in that camp because evacuating so many people required organization. The trucks had to drive from Bangkinang to Padang and come back. The transport took about two days and meanwhile, there had to be refuelling. We were in the last group that left the camp to be transported to Padang. The four of us together.

The next phase, of course was bound by ‘he who lives, takes care of himself.’ First you had to come to a port city. Sumatra had become unsafe for the Dutch because of the actions by Indonesian independence fighters. We had to wait for Dutch ships to come, ships that had been former passenger ships. The captains of these ships had been instructed to transport the people that had been in the camps and arrived on the coast, from Aceh, Central Sumatra, and South Sumatra, to Batavia, nowadays Jakarta. Batavia had become the central point for transport to the Netherlands, at least for the people who had Dutch roots. When the situation worsened, even people without roots in the Netherlands, but had long worked for- or were married with a Dutch person, decided to leave for Europe.

Did your family have somewhere to go in the Netherlands?

We arrived in the Netherlands on the Klipfontein. We had no material possessions, except for the clothes we had on. A month aboard the ship, where we had cozy moments with singing and cabarets. Upon arrival in Amsterdam, there were city buses arranged by the government to take people to their destinations. My grandparents lived in Epe, on the Veluwe, so we went there. I remember my grandparents waiting for us in Epe.

My grandparents lived in the Netherlands. My grandfather, on my mother's side, was a wealthy man. He had been a sugar broker. The family had a strong colonial background. My other grandfather had been a military man and a senior officer in the KNIL (Royal Netherlands East Indies Army), but that did not bring him wealth, though. But it was the former sugar broker that made sure that somewhere in the Veluwe a cottage was found for us. Although originally a very basic holiday cottage, that is where we could stay. However, my father did not have a job and we received an allowance from the RAPWI (Rehabilitation of Asian Prisoners of War from Indonesia). The idea was that the allowance would give you some time to find your way.

How did life proceed once in the Veluwe?

I went to school in Epe as of 1946. A school with a Bible, Christian education, and very different customs. Before you knew it, you were ready for secondary education, because also that had been arranged. We entered the last year of elementary school at fourteen or fifteen and were placed in a special education program so that we could immediately transit to secondary school.

For my secondary school education that started in 1947, I went to Bussum and that had also been arranged. I come from a family where education had always been valued and where people were sent to universities. So schooling was very important to my parents. I was sent for evaluation to determine my talents and the type of schooling that would be most appropriate for me. Of course, I came out with an alpha (humanities) profile. For that reason, I briefly attended the Christian Lyceum in Zwolle.

Shortly afterwards, my father got a job in Amsterdam, so we moved and I entered the Montessori Lyceum in Amsterdam, where I attained my diploma at twenty years of age (two years later than a regular Dutch student). The war had hardly delayed me. If my parents had been less conservative when I arrived in the Netherlands, I would have probably made it on time, as I was prepared to go to secondary school, instead of remaining one extra year at the primary school. However, the idea is that we needed rest and that after the camps, we needed to avoid overworking and recover psychologically. That was perhaps a wise choice on my parents’ side.

And then you went to university.

Yes, I went to the University in Utrecht to study Spanish. I could speak Malay, Dutch, French, German, and English. I hesitated for a while and considered studying Law or an Indonesian language. If I had chosen the latter, I would have had a very easy student life. However, I kept thinking about Albert Helman's book, ZZW (South-South-West) that I picked up from a small library in the transit camp where we stayed while in Jakarta awaiting transport to the Netherlands. The book is about Suriname, but holds this mystic relation to what was happening at the time in Brazil. For that reason, I went into the department of Spanish and Portuguese studies in Utrecht.

You graduated university in four years, after a deficient education and four years in an internment camp in Sumatra.

If the dates are correct, I think so. I got my doctoral degree in 1958. Studying Spanish and Portuguese in Utrecht in the 1950s was not easy. There was Professor Van Dam. He was considered a deity in the university life in Utrecht, a sort of a pope. He was however, a very unpleasant person. Furthermore, he was known to flirt with the royal family. He was the court tutor of Prince Bernhard, husband to the future queen. We had morning meetings at his office, around half past eight, then nothing was discussed really, and at some point he would declare, ‘lunch at eleven because at twelve the car will pick me up to go to the palace.’ He was incredibly pretentious.

There was also a lecturer of Portuguese, Mr Houwens-Post. Like me, he was also a Dutch Indies boy. We kind of spoke the same language. We shared a bit of the same atmosphere. I found Portuguese much more pleasant, enjoyable and intimate than Spanish, so I shifted my focus, my sentimental and emotional focus from Spanish to Portuguese. That is how I ended up teaching Portuguese at various universities in the Netherlands.

What happened when you finished your degree in Utrecht?

I had to serve in the military. Military service was compulsory. I had to serve for two years. Initially, I was recruited for the special forces (the commandos). However, after reading my curriculum vitae and my life story, the army switched me to the SMID (School for Military Intelligence) in Harderwijk. I was then assigned to learn Russian. That was wonderful! I got to study a new language, for free while in the military! The daily program was learning Russian in the barracks, with Russian tutors. It was absolutely amazing. In a nutshell, I sat with intellectuals like myself, the whole day learning languages, meeting people who later moved to academic careers as well. One of my colleagues in Harderwijk became later the Rector of the University of Amsterdam, while someone else became a full professor at the University in Wageningen. While I was learning Russian and serving, my first article came out, published in Portugal, dated 1961, about the historical meaning of the D. Francisco Manuel de Mello's writings.

So, what happened when you finished your military service? Did you think about writing a PhD?

I returned to Utrecht and I was appointed at the university as a student assistant at the Institute for Spanish and Portuguese Studies. That is when the idea of writing a PhD arose. You see, my conflict with Professor Van Dam endured and I had to compromise by working on D. Francisco Manuel de Mello because he had a Portuguese father and a Spanish mother. Van Dam did not want students to work on Portuguese subjects, so this was the compromise. He was a very obnoxious man and unaware of the value of Portuguese language and literary production for the understanding of worlds outside of Europe.

My problems with Van Dam continued, though. I wrote my book about D. Francisco Manuel de Mello in Dutch (not in Spanish or Portuguese) because I believed it was important to write in my own language and to disseminate my work and findings about this fascinating figure to the Dutch public. When it came to the publication of a Spanish version of my book, I resorted to the work of a translator of Spanish and refused to make the translation myself. Van Dam was furious. His vision of erudition was a closed, elitist idea of separation between academic knowledge and the rest of the world. I always thought that knowledge is rather part of the common good and should be as accessible to all as possible. Our different visions remained up to the day he passed away.

As Pedro Calderón de la Barca stated in his poem, ‘pompa y alegria’ - that was Van Dam.Footnote 2 As professor, of course, he punished me by making my career in Utrecht impossible. He demoted me to library assistant at the Institute, where I was only allowed to become a cataloguer. I endured the humiliation and awaited my chance. I continued, of course, to do my research in Portuguese literature and its historical impact and underlined my intellectual positioning by taking up a fellowship at the University of Coimbra, where at the time (1960s) there was the first attempt to work in a multidisciplinary team of historians, philologists, philosophers, linguists and sociologists on subjects regarding Portuguese history, particularly the history of the empire and the ultramarine provinces (as the colonies were then referred to). In the discussions in that group, my curiosity and passion for the history of the peoples without written languages arose. I guess that is what scholarship now calls peoples without voices. The entry point were the enslaved, particularly in Brazil, but quickly my focus became the Indigenous nations of Brazil and the way Brazilian, Angolan, and Portuguese writers saw these nations through the ages.

However, while you were finding a new passion and redirecting your research for an interdisciplinary history of the peoples without voices, you were still cataloguing books at an institute's library. That was a waste of human capital, do you not think?

Knowledge never goes to waste and I never saw my research as capital. And after bidding my time, and in a rather unexpected turn of events, I saw a job advertisement in the newspaper. The library of the University of Groningen was looking for someone to bring order into their collection of Russian books and manuscripts. They had recently received and added an extensive collection and had nobody to organize the old collection and add the new. I applied not with my Utrecht credentials holding a PhD, but rather with my military service credentials where the Dutch state had been so kind as to make me proficient in a language without financial burden.

I was very happy to be appointed in Groningen. I had no idea about what was happening at the university and I barely knew the town. I had the best years of my life there and I never felt as welcome and as recognized in my work as when I worked there. Although I was hired by the library (1965), when the Faculty of Arts found out my new research interests, they offered me a joint position as a lecturer at the Institute of Spanish and Portuguese Studies (1967), where I got a permanent position and where I was advanced to senior lecturer. I stayed in Groningen until 1978.

So, end of the 1970s, you leave Groningen and take up a job at the University of Leiden.

Yes, I went to Leiden in 1979 and this move, like so many things in my life, was determined by my time at the Japanese camp in Sumatra. I was doing very well in Groningen. However, I needed some intellectual challenges and I wanted so much to continue pursuing my idea of bridging literary and historical studies of Brazilian Indigenous nations. By chance, I met Jan Lechner, a Hispanist and at the time professor of Spanish studies in Leiden. Lechner was also an East India boy like myself and also he had been interned in a Japanese camp, for him it was Java. As camp people so often do, we had a ‘fluttering silent conversation’ about my research and he told me that I could come to Leiden if I wanted to. He was willing to give me the space and the resources to continue my research. The offer was for the TCLA (Talen en Culturen van Latijns Amerika – Languages and Cultures of Latin America).

I took a leap of faith and that was the worst mistake of my professional life. Upon arrival in Leiden, I was caught in what became known as the TCLA-trap. Lecturers at the institute were welcomed into an ongoing conflict between Erica Garcia with her ‘Columbia’ like mannersFootnote 3 (and her entourage) and Jan Lechner (and his clique). While Garcia was prone to conflict, Lechner was a weakling, whose only goal was to avoid conflict and smoothing out sores, all to the grievance and chagrin of the rest of the institute's employees. I left a peaceful and amicable department in Groningen to enter the lion's den in TCLA.

TCLA seems to have had a long history of bickering between members of the staff though.

Yes and that is rather regrettable and a shame, really, as TCLA never lacked high quality researchers and good tutors, which makes it all the more strange. However, at some point, the internal strive spilled into the public arena, with the publication of a news report in a national newspaper. The title read: ‘Department of Languages and Cultures of Latin America After Restructuring: Our Department is Growing Back into Unity.’ This was, of course, the sign that things had gotten out of hand several times before.

Of course, the bickering was mostly between the Hispanists. But then, there was also the idea that Spanish was the leading discipline, whilst Portuguese was subservient and tolerated in the department. This was common to all departments I worked at. Portuguese as a language and culture were seen as less important. The history of Portugal and of the Portuguese speaking colonies (later countries) were secondary. What is curious, however, is that the photograph that was used for the article in the newspaper depicted all Hispanists (and the rest of the department) standing before a map of Brazil, where the territories of the indigenous nations were delineated as well. Their haughtiness precluded them from actually noticing this curious detail. My problem remained, since nobody seemed to know much about Portuguese and the Portuguese worlds or even have the intellectual curiosity to find out. What Lechner or Garcia knew was of quantité négligeable.

What drew you to studies of Portuguese and of the Portuguese speaking worlds, particularly of the peoples living in Portuguese claimed territories, without being of Portuguese heritage?

You know the words mágico or meigo?Footnote 4 For me this is how I define Portuguese as language in its multiple contemporary and historical forms and variations (including the so-called ‘creoles’ which emerged in Africa, Asia and Brazil). Portuguese is a language of affection and sympathetic. In its creole forms, Portuguese reminds me of Malay and ‘tropical Portuguese’ resembles and translates into a very similar Malay-speaking culture of encounters. The atmosphere of these languages, in its diasporic forms is identical. They encompass a world that has been lost, and found anew, reinvented, but never forgotten. All forms of Portuguese and Malay stand as testimonies of a resilience of pluri-culturalism that survived violence, injustices, inequalities, or even the total negligence of the most basic human rights throughout history. You can hardly claim this for Spanish, French, or English.

The best of Spanish literature remains the one written in Galaico-Portuguese, rather than Castilian. Those early texts are worldly and encompassing of pluralities (of peoples, customs, ideas), even if most were produced during the Medieval Peninsular wars against the Islamic empire. This tradition, full of contradictions and historical hardships, continues in Portuguese in Europe and elsewhere in the world, whilst Galaico retracts and Castilian becomes the language of the ‘Great Empire.’ The best example is perhaps the Cantares de Santa Maria. In the end, it all comes down to the living cultural experiences of saudade, understood as what has been lost, what was never there, what is not, and what will never be. In all these variations, exploited peoples (from the enslaved Africans to the indigenous populations), colonists, religious orders, and so on experienced life and history and have poured those experiences into the emotions of a language. Retracing these emotions and these living experiences is thus inextricably related to profoundly and unconditionally understanding a language.

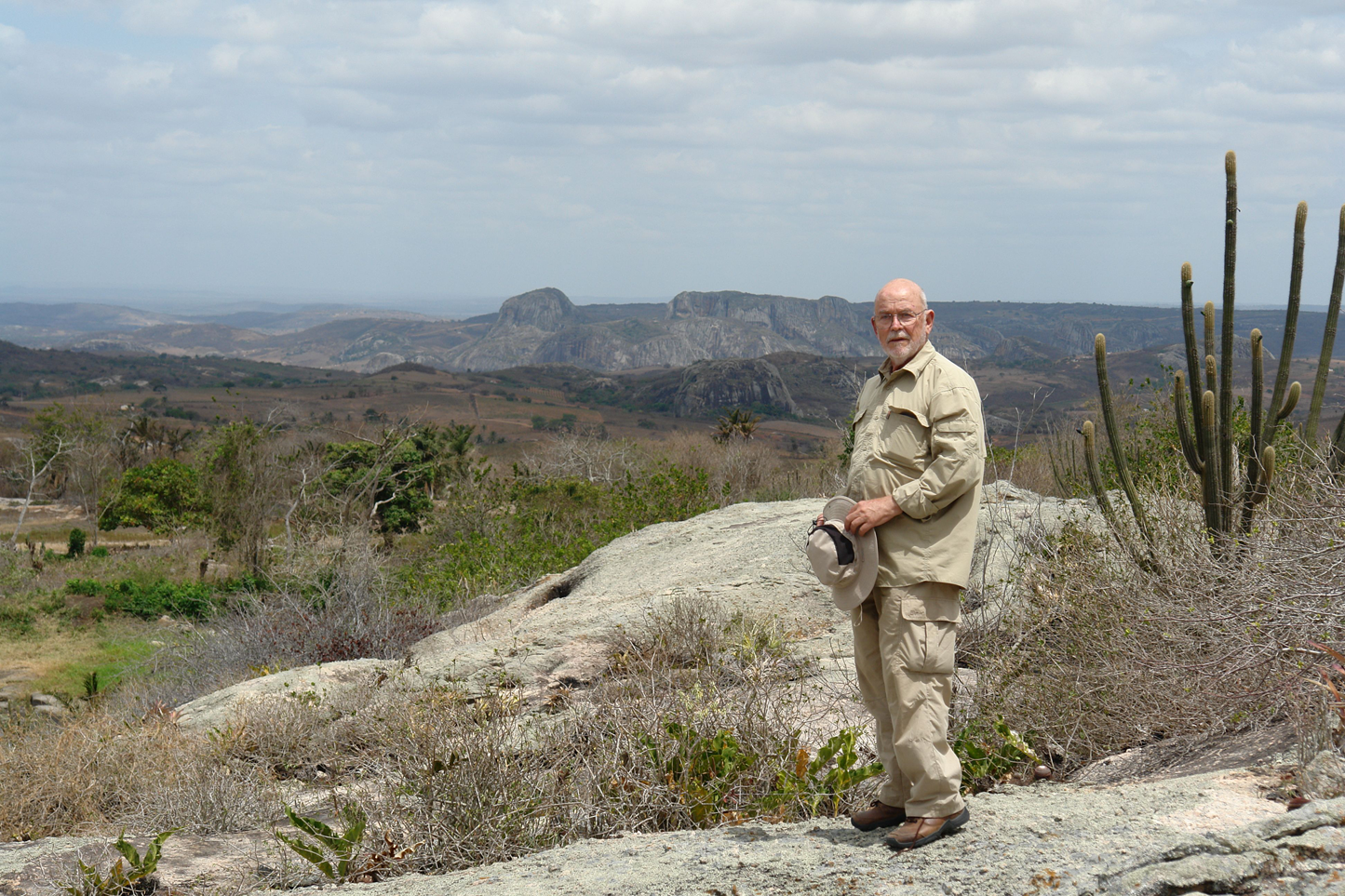

When you look back at your academic career, what in your view is the greatest contribution you have made to the knowledge of the historiography, history, culture and language of these Portuguese worlds, especially of Brazil and particularly of the indigenous peoples (índios)? Writing about the sertão, from a historical and literary perspective, for the daily experiences of the diverse peoples that live there is a challenge if you arrive from an urban, very organized, and controlled society. How do you immerse yourself so deeply in the object of your study, particularly when you have worked extensively in- and about the Amazon?

Well, there are a few tricks I developed over the years. When I travel to Brazil for research, I land at an airport, usually Recife or São Paulo, two very large cities. The first thing I do is spend one night next to the central bus station. I wake up as early as possible the next morning and I get an intra-regional bus and go as far into the countryside as possible. For example, when I land in São Paulo or Recife, I take the bus to Xique-Xique on the São Francisco River. It takes me about one and half day to get there and all the way I look out the window and wonder about the lives of the people living there. When I get to the municipality of Xique-Xique, I usually get off at one of the small villages and I rent a bike to go further into the sertão. I never go by car (even when other colleagues travel with me). This is the only way I have to observe the nature, the plants, the animals and, of course, the people. In certain stretches, I even walk, usually barefoot (for a bit, because I am getting older now) so that you feel the temperature, the smells, and the earth beneath your feet.

If you keep travelling in this fashion to the Northwest, you come across, at some point the town of Santarém. From there, you can take a major road that leads to the Southwest and that links the North, for hundreds of kilometres to the rest of the country. At some point, you are in the middle of the continent, in a place called Rurópolis (Pará), where North meets South and East meets West. Spend the night there and then, in the morning, keep on by bike to the West. Have a chat with the lumberjack, take in the colours and the smells and the warmth. Then you are in contact with Brazil and you can start re-thinking language and history. The good conversations and ad hoc research happens along the rivers, where women wash the clothes and children bathe and in the middle of the untouched jungle. The places over which colonial institutions tried to rule and were forced to yield to the power of nature. Explaining and highlighting this experience over time has been my contribution to both the field of linguists, literature, and culture, and the discipline of History. I try to realize a sound integration in my spiritual, intuitive and physical surroundings.

Historians have stopped going to the places they study. Most people in the large Brazilian and Portuguese universities that work with the sertão and the índios never visited the former or talked to the latter. What do you think about this?

Writing History or studying language, literature and culture is an act of faith in Humanity. However, if you do not try to meet and experience that Humanity, in all its facets, the good and the bad, the violent and the peaceful, how can you call yourself a neutral observer of historical actors? How do you abstain from your century when observing lives, struggles, and conviviality that took place centuries ago and of which we only know very sparsely through written documents? In this sense, the digitization of written sources opens doors to liberalize knowledge, although it incurs the risk that people will be writing and thinking about realities that they neither relate to, nor fundamentally understand today, let alone three or four hundred years ago. The added danger of this dissonance is that young historians seem oblivious to the danger of losing the principle of neutrality to study history and in a very naïve manner allow their work to be used (and abused) by institutions and political parties that can only prosper if history is manipulated and/or altered.

Brazil has been poorly led by economic and intellectual elites. The country industrialized in an almost cannibalistic manner, society has become materialistic over time and nature has been neglected, abandoned or simply extinct, with all the consequences for communities that historically depend on these resources. The only solution I see is the use of the human mind and the traditional resilience and resistance that is inherent to the Brazilian people.

The emotional and passionate way you speak of Brazil, its people and history, is as if you have replaced your childhood attachment to Indonesia with a new tropical space, with similar historical trajectories (colonialism, enslavement, exploitation of indigenous populations, and resources).

I think I have. I have gotten to know Brazil and I added it as a new element to my life, first through work, then through dedication and research. Indonesia remains then as a grateful reservoir of memories and gratitude of the past, with the conscious knowledge that my interest in human cultures was born of my being born in a rainforest in the island of Sumatra, where I learned to listen, smell and celebrate live, experience death and ultimately exist. My study of Brazil and Portuguese has allowed me to let go of Indonesia in a peaceful way, by simply letting it slip away.

I have two last questions. Yesterday, quite coincidentally, the research report of the KITLVFootnote 5 and the NIODFootnote 6 about the Dutch state intervention in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) for the period after the World War II has concluded that there is unequivocal evidence about the use of excessive and consistent violence by Dutch authorities, whether intelligence agencies or military forces, against Indonesians.Footnote 7 How do you view the conclusions of this report as someone born and raised in Indonesia, who has been interned in a Japanese camp and was sent after the war to a country you had never seen?

With great regret and sadness. Such inhumane violence should have never happened, notwithstanding the circumstances or reasons of state. The whole war against our fellow Indonesians should have never taken place. Particularly when in the Netherlands some people had fought against the German occupation. It is only normal that people want their country. The obstruction against Indonesia's independence was wrong by all measurements. Sukarno was right to claim Indonesia for the Indonesians and yet the Dutch decided for an undeclared war. All that violence was unnecessary. All those victims should have been spared. Everyone had suffered enough under the Japanese occupation. It was enough for all of us.

How could the Dutch state expect a different outcome? The European War had just ended and the state decided to enrol farm boys from the Veluwe, or former members of the resistance, and send them to Southeast Asia to punish Indonesian insurrection. This could only lead to human misery all around.

You are now in your nineties. You keep finding new documents about Brazil in the Dutch National Archives in The Hague. You have done a lot, you have published profusely, you have been a life-long activist for the rights of the indigenous populations in Brazil and an active supporter of all forms of Portuguese (including all the creoles spoken in the Portuguese speaking worlds). What do you still want to do?

Daydream. Be free to do my thinking. I walk. I wander on my own pace. I bike in the summer, up to a maximum of twenty kilometres to look at nature (particularly birds). I still take to the marshes in the Autumn to look at the amphibious animal populations. In June, I pay particular attention to the orchids and I map their bloom through the days. In the summer and early Autum, I take to the water. The inner lakes and the open sea. Elysium, Utopia. Besides, I still have the fortune to live quietly in the company of my wife Joana and our dogs… and my books.