In 1991, the Soviet Union imploded and a ‘third wave’ of liberal democracy was supposedly advancing. (The first wave was the expansion of the franchise in the nineteenth century, the second decolonisation after 1945). Not just in the former communist world, but amongst former client states of the Cold War, where autocrats could no longer rely on being propped up by Moscow or Washington. Academic fashion shifted from defining the preconditions of democracy, and setting a pretty high barrier, to an analysis of decision-making. With the right moves, any country could become a democracy. Thirty years later, not only was democracy long dead in Russia; its previously unthinkable demise was feared in the United States and elsewhere.

What did these erosions of democracy in places as disparate as Russia, the United States, Hungary and India have in common? This book is about a different type of decision-making: not round-tables to introduce democracy, but political manipulation to dismantle or undermine democracy. And it is about political manipulation under an unfamiliar name – political technology. The term originates in Russia, where it is ubiquitous and readily understood. Political technology is how elections are fixed; it is about how propaganda is organised; it is how neighbouring states are undermined. The ubiquity of political technology has created a system where everything political is totally controlled, and all politicians are actors. Its efficacy has made political technology the leading edge of Russian foreign policy, infecting neighbours and rival powers alike. But the argument of this book is that political technology is also shaping politics throughout the world. Others may not use the term in the same way as in Russia, but it is there without being named. Moreover, there are many common types of political manipulation – many of the same plays, if not necessarily the same complete playbook – and this book aims to provide a typology. What Russians call the use of ‘administrative resources’ to control the vote, is ‘voter suppression’ in the West. Manipulating the news agenda to change the story is ‘switching the tracks’ (perevod strelki) in Russian, and ‘wagging the dog’ or ‘dead cat’ in the West. The spin doctor in the West is the stsenarist in Russia, meaning scene-writer or scene-setter. Vbrosy, ‘toss-in’ stories, fake drama or arresting emotional attention-grabbers, are now wrzutki in Poland, or in America, well, that would be Donald Trump’s one-time Twitter account.

What Is Political Technology?

I asked some Russian acquaintances for their definition of political technology. According to analyst Valery Solovey, it is ‘the methods, means and techniques of realising politics’.Footnote 1 ‘In essence, politics as the art of power cannot be separated from the means and methods of achieving the goal. Means and ends become practically one and the same’.Footnote 2 The definition of the leading Ukrainian expert Georgiy Pocheptsov, who might have been expected to be more critical, is that political technology is any ‘way of organising information, semantic and human resources to achieve political goals’.Footnote 3 For Russian political scientist Vladimir Gelman, ‘political technology is a complex set of actions, aimed at achievement of certain political goals through making an effect on changing behaviour of some political actors (elites, leaders, parties, etc.) and/or of mass public, who would behave otherwise without the use of political technology’.Footnote 4

All of these definitions include and instrumentalise almost everything political. In Russian, the two words in ‘political technology’ are without nuance, and imply an obvious pair. Politics is technology. The two words are practically synonyms. All politics is manipulation. This is not true; not all politics is manipulation. But there are words missing in English, elements that are not clear from the literal translation. And defining all politics as political technology doesn’t get us very far. It doesn’t define a new subject for study. However, it does tell us that Russians are cynical if they view all politics as manipulation. This is also often the world-view of political technologists themselves – but, again, that is circular.

There are academic definitions, if not of political technology, then of political manipulation. Geoffrey Whitfield, for example, posits two political subjects. Then ‘an act of manipulation is any intentional attempt by an agent (A) to cause another agent (B) to will/prefer/intend/act other than what A takes B’s will, preference or intention to be, where A does so utilizing methods that obscure and render deniable A’s intentions vis a vis B’.Footnote 5 A might prevail over B in decision-making, in agenda-setting, or by manipulating what B actually wants.Footnote 6 Political technology has this type of manipulation of political subjects at its core, but it is also the whole broader process of engineering the political environment to shape the decisions of B – the ordinary citizen or voter.

So my definition is that political technology is not the same thing as politics. Political technology is that part of politics which views politics as (mere) technology. It sees politics as artifice, manipulation, engineering or programming. Some forms of political programming might be neutral or broadly positive. The Arab Spring in 2011 initially promised online empowerment, which many saw again in the ‘first social media war’,Footnote 7 Russia against Ukraine in 2022. Aleksey Navalny’s ‘smart voting’ campaign in the 2021 Russian elections – if your party is banned, vote for the least bad Kremlin party – was a type of political engineering. So in this book, political technology is defined as malign: engineering the system in the service of partisan interests, narrow minorities, oligarchies or captured states. Political technology is political engineering that is dark and covert, non-transparent and often fraudulent.

The shortest definition of political technology would therefore be the supply-side engineering of the political system for partisan interests. Democracy is supposed to be all about demand. Direct or representative democracy is about the expression or articulation of popular demand. Political technology, on the other hand, aims to shape, control, channel or fake popular demand. Political technology creates artificial structures. In Russia and many other post-Soviet states, it means that the entire party and political system is engineered and scripted. In the United States, it means that parties and politicians are not the primary political actors they should be; that role is increasingly taken over by an artificial universe of Political Action Committees, dark money and astroturfing or artificial grass-roots campaigns. Politicians knowingly dive into that world for the services they need, but they are increasingly just frontmen and women.

Political technology is not an organic part of politics or a natural offshoot. Its biological metaphor is a virus. Political technology enters the body politic from the outside. Its mechanical metaphor is leverage. Political technology is a post-modern adaption of the traditional Trotskyist tactic of entryism – the infiltration of a party or institution by outsiders seeking to take over a weakened host or subvert its purpose for their own. Political technology is the engineering version of Gramsci’s ‘long march through the institutions’ – but no longer a gradual process of infiltration by individuals, but the applications of jump leads.

Political technology is professional. It is organised. Political technologists work as individuals, in companies and for the state. Brexit and Trump triumphed in 2016 because they exploited conspiracy theories: but many attributed their success to actual conspirators, like Cambridge Analytica, Steve Bannon or Russia. Certainly, there are dangers in accepting the myth of all-powerful covert actors like Cambridge Analytica at face value – not its public face, but the face it was all too happy to present to clients in private, of a master manipulator company for hire. Individuals and individual companies are not all-powerful; they will come and go or sell snake oil. The idea that Cambridge Analytica was solely responsible for Brexit or Trump’s election is a comfort blanket for many liberals. But there is truth in the broader point: there are companies like Cambridge Analytica proliferating everywhere. And they are political technology operations. According to former employee turned whistle-blower Christopher Wylie, ‘it’s incorrect to call Cambridge Analytica a purely sort of data science company, or an algorithm, you know, company; it is a full-service propaganda machine’.Footnote 8 In this book, we will hear about the Foundation for Effective Politics in Russia, Silver Touch in India, Webegg and Casaleggio Associates in Italy and Black Cube in Israel. There are hundreds of companies throughout the world that meet the above definitions of political technology. There are huge numbers of more shadowy operations, not necessarily organised under a single company roof. The Oxford Internet Institute, looking just at ‘formal organisations … using social media algorithms to distribute disinformation’, and not at my broader definition of political technology companies, found them in 28 countries in 2017, 48 in 2018, 70 in 2019Footnote 9 and 81 in 2020.Footnote 10 This book will examine the myth and reality of powerful political technologists, notorious individual fixers in many countries: Gleb Pavlovsky and Vladislav Surkov in Russia, Steve Bannon and Roger Stone in the United States, Gábor Kubatov and Árpád Habony in Hungary. Collectively, there is a growing market for manipulation services that politicians and private interests are prepared to pay for, and which, crudely enough, work.

But the globalisation of political technology is more important than particular notorious companies or individuals. It would also be a mistake to focus too much on pure technology. We have got used to hearing about trolls, bots, micro-targeting and AI, but these are all just tools of the trade. The trade is what matters – and there is a booming trade out there, a whole political culture of manipulating political culture, that has been developing since long before Brexit and the election of Donald Trump in 2016, before the fake news tsunami over Ukraine in 2014 and before the introduction of the smartphone in 2007. Russia has had what it calls political technology since at least the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. America has had ‘political consulting’ since the 1970s – but ‘consulting’ is a woefully out-of-date label for the range of manipulation services available in the free market wholesale bazaar of American politics. There are many studies of political consulting, but none that look systematically at those parts of the political consulting business that fit the definition of political technology given above. Political ‘technologists’ and political ‘consultants’ are often doing the same things. They do more than just play a role in politics; they seek to shape the architecture, the tectonics, and the toolkit of politics. They mould the narratives that drive politics. A political technologist is everything: according to Russian political technologist Aleksey Sitnikov, they are ‘campaign manager + political consultant + PR’.Footnote 11 Political technology is more than ‘spin’. ‘Spin-doctor’ was pretty accurate in the bygone era when the aim was to influence how the media writes about politics, rather than create political realities themselves. ‘Spin’ was only a precursor to political technology. But we don’t have a good definition in the West for what came after spin.

Political technology in Russia and political consulting in the West increasingly interact. American political consultants have been working abroad since the 1970s and 1980s. There was blowback: winning elections and reputation laundering for disreputable clients in the developing world changed the nature of politics back home. As did interacting with the post-communist world from the 1990s onwards. In the words of one observer of both worlds the journalist Vladislav Davidzon, ‘in the post-Cold War context, American capitalist consultants and political operatives began to both teach and learn new skill sets from their post-Soviet patrons and it morphed into a mutually clientelistic relationship’.Footnote 12

One thesis of this book is that what is called political consultancy increasingly uses the techniques of political technology; both at home and abroad. Not everything is political technology. Political technology is not why everything happens. Political technology is only one part of the world of normal politics. But in that world, the amount of artifice and engineering is on the increase. At different rates in different places: Russia and (almost) Hungary are countries completely taken over by political technology. America went to the brink with the Capitol insurrection in January 2021.

Not every political consultant in the West would meet my definition of engaging political technology. The normal business of politics, such as campaigning, building and marketing political parties, is not political technology. Organising astroturfing or voter suppression is. Conversely, because the Russian definition is too broad, not everything political in Russia is political technology. Building a normal political party is not political technology. In fact, political technology often competes with real politics and seeks to displace it.

Three Types of Virtual Politics

Political technology involves three types of engineering, creating three types of virtual politics. First, political subjectivity can be engineered. Political technology in Russia in the 1990s began by creating virtual subjects to compete with the real, fake and manipulated parties and politicians.Footnote 13 Next those virtual subjects were placed and moved in virtual political geometry. Political technologists increasingly controlled the rules of interaction and the overall script. The virtual defeated the real. So that finally all key political subjects – the left, the right and centre, government supporters and opposition – were artificial. Some such fakes existed only on TV, online or in social media. Other mediatised proxies and surrogates had some life of their own, but it was the mediatised reality that led the real-world performance.

If the Russian model is ‘theatre politics’, the US model can be called proxy politics. The core of the political system is real, but a lot of the moving parts around it are artificial. Real politics is not replaced by theatre but is surrounded by an alternative world of proxies, surrogates and fakes, astroturfing or artificial grass-roots, (im)personation and masquerade. The two main political parties, Republicans and Democrats, coexist with the world created by political consultants and outside interests, that both serve and direct the parties. Many of the moving parts in this system are real, but many are artificial. There are two types of artifice. One is the power of money acting through Political Action Committees and other dark money channels. The other is the surrogate universe: since the 1990s the Republican Party has created an outrage machine that combines real groups like the National Rifle Association and Christian fundamentalists alongside astroturf organisations designed to whip up grassroots grievance and anger. This type of political technology is an instrument of partisan or state power, though it can still have feedback loops. The real world can participate in the production of the fake. If an artificial party is successful, people will join it. The #StopTheSteal campaign in America in 2020 has been described as elites ‘inspiring the rank and file to produce false narratives’ of election fraud, ‘and then echo that frame back to them’.Footnote 14

The third type of engineering is shaping the narratives that political subjects use and are guided by. Politics has always been about narrative, but because its traditional forms, like ideology, religion or other meta-narratives, are in decline, political technologists have more freedom to shape how people think about politics. In so far as our definition of political technology includes manipulation, this does not include all narrative politics, but narratives that are false, and/or create an impression of popularity of belief or credibility. Political technology, therefore, includes misinformation and disinformation, for which I follow the definitions of Philip Howard of the Oxford Internet Institute (OII). Misinformation is ‘contested information that reflects political disagreement and deviation from expert consensus, scientific knowledge or lived experience’. Disinformation ‘is purposely crafted and strategically placed information that deceives someone – tricks them – into believing a lie or taking action that serves someone else’s political interests’. The OII also talks of junk news, which they define as ‘political news and information that is sensational, extremist, conspiratorial, severely biased, or commentary masked as news’.Footnote 15 What makes misinformation or disinformation take off, however, is creating the impression of widespread support or credibility of a particular narrative. This requires delivery systems created by political technology that first launch the narrative, followed by white streaming, moving narratives into cleaner sources, grey streaming, moving them into ambiguous sources, and mainstreaming, moving narratives into mainstream mass media. Political technology is therefore about lies, but also about ‘lie machines’, which the OII defines as ‘a system of people and technologies that delivers false messages in the service of a political agenda’.Footnote 16 Ukrainian practitioner Taras Berezovets’s definition of political technology concentrates on media: ‘a complex of tools to shape public opinion, meddling in the election, often election fraud in order to win campaigns; but especially in media, with half-truth or significant part of lies and manipulation with facts and quotes’.Footnote 17

Narratives need boundaries. The third type of virtual politics can be called ‘Matrix politics’. A majority of the population, or a large segment of it, is trapped in a narrative it does not want to or cannot leave. This is not totalitarianism, where all are required to believe. The boundaries of the Matrix are soft; more often derived from the logic of the sect and in-group solidarity than from coercing the ability to leave. The most effective type of narrative capture is structured around one trope that creates an emotionalised us-them narrative: like Fortress Russia, Brexit, or the survival of ‘white America’.

Political technology makes extensive use of media, but it is about more than media. This is why ‘spin’ is only partly political technology (see Chapter 4). Spin is narrative control, one of the three forms of engineering listed above. So spin only scores one out of three. However, if political operators who happen to be called spin doctors also set up artificial structures or subjects, they are more like political technologists. Someone like Roger Stone in America, a self-confessed ‘dirty trickster’, is a political technologist. He has spun opposition research and conspiracy theories. He helped organise the fake ‘Brooks Brothers riot’ in 2000, a bunch of Republican operatives posing as ordinary citizens trying to stop the vote recount in Florida during the Al Gore versus George Bush election. That said, spin is a precursor of political technology, especially in the high age of spin in the late 1990s and early 2000s (see Chapter 4). It created an ‘audience democracy’:Footnote 18 voters consumed their prepared diet, politics became a solipsistic world where spin doctors chose the subjects and terms of the debate. Other issues were forced off-stage – at least until the populists whom this empowered brought said issues back.

Is Political Technology New?

Some would claim that political technology is just a new term for an old phenomenon. The black arts are universal. Power, corruption and lies are an eternal trinity. This book argues that five factors make it new. First, a political service class has grown up alongside conventional politicians and increasingly pulls their strings. The political consulting industry in the United States dates back to the 1930s but mushroomed from the 1970s and in the UK in the 1980s. The political technology industry in Russia developed in the 1990s. All have globalised since. The second factor was the decline of traditional mass politics – of which the rise of the political service class was both cause and effect – creating areas of vacuum for political manipulators to exploit. The third factor was the consequent global cross-fertilisation of techniques and personnel. Not a globalisation of ideologies, but one in service of the twin raisons d’être of money and victory. Fourth, by the 1990s, political technology was using new technologies that increased reach and effect. A lone propagandist is almost an oxymoron (though individuals can have quite an impact by gaming social media algorithms). Propaganda needs what the OII calls ‘Lie Machines’, which are built by political technology.Footnote 19 Fifth is the deep mediatisation of societies that enables this narrative reach, which in the West was largely a post-war phenomenon and in the developing world more often post-millennium.

These five factors in combination have created new potentialities for political manipulation. Many individual technologies discussed in this book have a history. But the use of so much manipulation in combination – the Russian term is kombinatsiya – creates something qualitatively different and more pernicious. Kombinatsiya creates synergies and is itself one reason why political technology is effective.

The Spread of Political Technology

This book argues that common patterns of political technology can be found throughout the world. Not just troll farms or fake websites, although these are important tools; but whole industries of political manipulation. I suggest four reasons why this is the case. First, political technology can be found in all types of political regimes: authoritarian states, democracies and hybrid regimes. Each type has a different pallet of techniques, but those techniques overlap. Political technologists appear in all countries. Some are native and some cross borders. Logically, their number should be fewer in ‘pure’ democratic or authoritarian states and concentrated in the grey zone of deteriorating democracy and imaginative authoritarianism. The two are therefore perhaps becoming more alike, in so far as democracies are increasingly using some of the techniques of autocracy and vice versa. ‘Convergence’ would be the wrong word, however. There is no actual meeting point. So-called ‘smart authoritarian’ states want to stay authoritarian. In deteriorating democracies such techniques are used to win elections and to keep elites in power, but without much thought about the consequences or about where democracy might be headed in the long run.

Second, there are the many channels of globalisation, that determine how given practices emerge in parallel throughout the world or are exported or imported. The globalisation of political technology takes many forms. One possibility is common inspiration, often intellectual. According to the leading Russian political technologist Gleb Pavlovsky: ‘in the ’80s and even in the ’70s, I read translations of American specialists in propaganda, early ones such as Lippman, Bernays. And I had a very, very vivid interest in how they applied the findings to politics’.Footnote 20 Pavlovsky also liked to cite the work of James Burnham (1905–87), the elitist American prophet of a society of managers and planners.Footnote 21

A related case would be distance learning; there are many cases of political operators in the West who have studied or admired Russian techniques and imported or adapted them. This type of learning does not have to involve personal contact, although it might; and the learning process could be selective or adaptive. It can also happen in the opposite direction. Russia can learn from the West. Autocracies can copy one another. Democracies can copy from autocracies. Autocracies can copy from democracies. Deteriorating democracies can learn from each other. The Russian government flew in Michal Kosinski, an expert in the ‘psychometrics’ used by Cambridge Analytica, in 2017.Footnote 22 Cambridge Analytica data was accessed from Russia.Footnote 23 When the UK House of Commons produced a report on fake news and disinformation in 2019, ‘more people in Moscow (19.8% of visitors) had read it than those in London (17.8%)’.Footnote 24

Another possibility is parallel development. It just happens to be the case that Western and Russian political operatives have ended up using the same technologies in the same way, largely because the technology is the same or similar. Anyone can use the same technologies, which usually have low barriers to entry.

Globalisation is also driven by the exchange of personnel, either informally or contractually. The story of Paul Manafort is told in Chapters 4 and 6: a Republican political consultant who lobbied in Washington for foreign autocrats, moved to Ukraine in 2005 to work for the eventually ousted President Viktor Yanukovych, briefly ran Donald Trump’s campaign in 2016, and then ended up in prison for not paying taxes on his work in Ukraine. But Manafort wasn’t just going back-and-forth. There was a learning spiral: his vision, aims and tactics changed at each stage in his personal globalisation story.

The third reason for the spread of political technology involves general trends that affect how politics works, regardless of whether a given state is democratic, authoritarian or hybrid. The increasing mediatisation of politics, the growing power of narrative over material interests and the rise of cultural politics have all allowed political technology to flourish.

I have left the fourth reason till last, the actual technology in political technology. This book is not primarily about bots or social media platforms, although they all feature. When Russian political ‘technology’ emerged in the 1990s, it was really political manipulation dressed up in the language of faux-professional ‘technology’. It was more a product of local political culture than technology. But that was the analogue world, the world of images and image-makers. In the digital world, the proper effect of technology is clearly more important. There are elements of technological determinism going on: anyone can use the same manipulation techniques, anywhere in the world. Global social media platforms are precisely that; the interface and the algorithm are the same everywhere. But not too much technological determinism. Technology’s effects depend on circumstance and choice. Technology shapes politics, but politics and political choices affect how technology works.Footnote 25 As with all globalisation, local context is hugely important. Fake news can challenge the traditional media in the United States because traditional party loyalties are so strong; in fact, they are growing stronger. India is developing an extraordinary culture of viral propaganda that looks like Bollywood. This book is about ‘technologies’, the palette of techniques available in a globalising world to both authoritarian and democratic states. But the book is less about technology per se and more about political culture. More exactly, it is about the culture, practice and terminology of technology in manipulating democracy. Individual strategies, techniques and technologies come and go. TV, social media, Big Data, AI and bio-surveillance have all been heralded for revolutionising politics. Some technologies do indeed bring about radical change, but some are just the latest brand of snake oil. Political technologists and consultants are always hoping to find the latest technique. So something else is going on.

Different Genres of Political Technology

With all types of globalisation, political technology looks and operates differently in different countries and under different types of regimes. The United States had early leads in image-making on TV and then in Big Data. After its successful interference in the 2016 US elections, Russia seemed to have a comparative advantage in social media operations. According to the Ukrainian writer Oksana Zabuzhko, ‘Russia has crossed the Lubyanka with Hollywood (Orwell with Huxley, Big Brother with the entertainment industry)’.Footnote 26 She meant that the KGB (Committee of State Security) playbook of active measures, surveillance, infiltration and control had been married to modern propaganda methods. Russian TV, and to a lesser extent Kremlin social media operations, know their medium well and push emotional and identity buttons with some skill.

Some states are just the Lubyanka – traditional authoritarian states but with elements of political technology. Some are just Hollywood. The United States has a powerful security-surveillance state, but its political consulting industry was more influenced by Madison Avenue (hence the ‘consulting’), before moving to K Street (in Washington, just a few blocks from the Capitol and the White House). The United States is therefore K Street + money; except K Street itself is all about the money. The Israeli school specialises in high-tech surveillance. The Indian school uses very visual Bollywood-style propaganda on WhatsApp. Nativisation is always part of globalisation. Then new hybrids come along. Globalisation is plural and works in many directions. Romanian consultants work in Moldova and Albania. Israeli consultants are everywhere and were themselves influenced by Americans from the 1990s and Russians in the 2000s.

Does Political Technology Work?

Part of the case for looking at political technology is that it is crudely effective. After examining various country case studies, Chapter 9 looks in more detail at the question of when and how political technology actually works. It is argued that examples are numerous enough to be grouped into separate categories. There is political technology that creates closed systems of control, political technology in deteriorating democracies, and political technology as the defining feature of what is called ‘competitive authoritarianism’; that is, authoritarian states that allow some political competition but make sure that it is unfair. Political technology is most obviously effective if you have control of an entire political system, as in Russia under Putin. Political technology can also shift political systems towards greater control, by creating negentropy or reverse entropy, as in Hungary since 2010. Tightening control creates the possibility for even more control. Political technology widens or opens up the fissures in defective or deteriorating democracies. Either all the way to (different types of) autocracy or making democracy more defective than it otherwise was.

On the other hand, although political technologists sell the myth of their own power and potency, the new Masters of the Universe are not omnipotent. Artificial projects that smell too much of the resources or money behind them can be the victim of their own over-prominence. Political technology may be swimming against too strong a tide. Voter suppression in the 2020 American elections, for example, was substantial but dwarfed by a huge increase in turnout, of 10.4% compared to 2016. Chapter 9 looks at when political technology does and does not work – the cases of failure can be as illustrative as the cases of success.

How Talking about Political Technology Helps to Explain Politics

Talking about political technology brings a pertinent analytical perspective to many cognate issues. Many analyses of Russia use an IR (International Relations) lens – arguing that Russia has tightened domestic control and taken aggressive foreign policy measures because of the threats to its security from the West, NATO expansion in particular. A political technology perspective puts the desire to achieve domestic control first. Russia’s military actions against Georgia (2008) and Ukraine (2014 plus) came after the consolidation of domestic control in Putin’s second presidency (2004–08). The exact timing of diversionary war may not always match declining ratings;Footnote 27 but it meets a strategic need periodically to reshape domestic politics. The NATO ‘threat’ has been episodic; Russia’s passive-aggressive foreign policy and the hyper-reality of its TV propaganda are permanent features. Diversionary war can be found throughout the world;Footnote 28 studies have shown that it can even be more common in democracies because of the barriers to more prosaic forms of domestic success.Footnote 29

A focus on political technology helps to explain how ‘hybrid war’ works – as it is in large part a transfer of techniques from domestic to foreign politics. A focus on political technology helps explain how hybrid regimes work. One of the most common definitions of such regimes, which are part-democratic and part authoritarian, is that political competition is on an uneven playing field.Footnote 30 Political technology is what makes it uneven.

A focus on political technology helps explain the speed of democratic deterioration in previously stable liberal democracies. Democratic deterioration is due to many things, cynical elites and social change. But political technology provides leverage. A burglary could be blamed on the perpetrator or the householder’s inadequate security measures, but the burglar wouldn’t have gotten in the house without the crowbar. The use of political technology explains how and why democracy has been dismantled so quickly in Hungary (since 2010) and how Poland is catching up (since 2015). Political technology explains when spin or political ‘consulting’ becomes something else. The use of political technology is what to look for to check whether autocrats have changed their spots. They may introduce elections but use political technology to corrupt them under the radar.

Realpolitik

Political technologists often justify their trade as not just old but universal. The notorious Russian political fixer Gleb Pavlosky, for example, tries to normalise his work as follows: ‘I do not know politics without manipulation. Even Gandhi manipulated politics [he doesn’t say how]. The problem is dosage’.Footnote 31 One of Russia’s most conservative political technology companies brands itself after Niccolo Machiavelli. Indian political technologists have claimed inspiration from their own Machiavelli, the Brahmin Chanakya, who advocated realpolitik in his treatise Arthashastra (roughly the ‘Science of Politics’) eighteen hundred years earlier (see Figure I.1).

Figure I.1 Inspirations: Machiavelli and Chanakya.

Another excuse is the ‘professionalisation’ of politics. Techniques from business, advertising and marketing were transferred to politics in the 1960s and 1970s. The technologists see themselves as the importers of wisdom, and their cutting-edge methods as transcending the tedious limits and limitations of traditional politics. Politicians used to bring ideology, class or social cleavage solidarity, their previous careers to legislatures and government. But the political elite is increasingly a clerisy that knows nothing but politics. It sees politics as a craft, and technology comes naturally.

Another rationale in self-defence was given by the political consultant Sam Patten, indicted by the Mueller Enquiry, who observed of the United States, ‘I’ve worked for Ukraine, Iraq, I’ve worked in deeply corrupt countries, and our system, isn’t very different’.Footnote 32 This overlaps with the private thoughts of Nigel Oakes, founder of Cambridge Analytica’s parent company SCL: ‘frequently people come to us and say “we’ve got so many dirty tricks against us, we now need to know the dirty tricks to go back”. Or “we need to know how to counter the dirty tricks and you guys seem to know how to do it”’.Footnote 33 When Russian political technologists were working in Madagascar in 2019, one of them said: ‘Do you think that we’re disgracing our country?’ ‘Or devaluing her name?’ The colleague told him not to worry. ‘If you think about it’, she replied, ‘the whole planet is disgraced. Not the planet, precisely, but humanity’.Footnote 34

But the dismissal of democracy as a façade for realpolitik is too trite. Yes, some have always preferred a rigged election to a free choice. Power-holders have always resisted democratic attempts to disperse power. We should never take the self-proclaimed virtues of democracy for granted. But no, if there is a cynical assertion that democracy is impossible, or always and everywhere equally imperfect, or if we want to chart the rise and fall of democracy. Established democracies like Britain, France and the United States are unquestionably more democratic today than they were around 1800 or 1890. The franchise back then was limited; representative institutions shared power with monarchies, or were ‘checked’ and ‘balanced’ by a Senate, an electoral college or a House of Lords. But democracies have lost ground since around 1980.

Smart Authoritarianism

Why would different types of regimes use political technology? This is perhaps least obvious in the case of authoritarian states. They impose their power, imprison their opponents, and throw away the key. Political technology is not needed when authoritarian regimes already have effective mechanisms of control. But most of the traditional props of authoritarian power are in short supply. What Max Weber called ‘traditional authority’, the unthinking acceptance of customary forms of rule, is becoming increasingly rare. Monarchies are less common. Clerisies, both religious and lay, are in decline; if not in many Islamic states. The Communist Party of China still rules, but other monopoly parties are gone, like the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, or no longer rule, like the Institutional Revolutionary Party in Mexico. Authoritarianism justified by projects of social transformation is much less common. As is the imposition of a prescriptive and intrusive moral code, as in Franco’s Spain, although Iran or the Islamic State would again be exceptions. Authoritarian regimes are rarely truly fascist, in the sense of the historical fascism of the 1930s. A cult of violence and the use of militias and mobs is less prevalent on the far right. Though again Islamic State would be an exception. A political technology ‘of the streets’ can organise and exploit demonstrations, crowds and mobs. But this is not the rule through mass violence of old.

The other longstanding props of authoritarian rule, like coercion and incarceration, carry increasing reputational costs in a globalised world. Autocrats increasingly use, and corrupt, the language of democracy. The internet and social media create instant exposure costs for the use of state violence. Sergei Guriev and Daniel Treisman have used the term ‘Spin Dictators’. They argue that, instead of ruling through fear and violent repression, most modern authoritarian states ‘rule through deception’. ‘Violence is concealed to preserve [the] image of enlightened leadership, “censorship [is] covert”, there is “no official ideology” and “more subtle propaganda to foster [the] image of leader competence” and some “pretence of democracy”’.Footnote 35 Pretence works. Even highly manipulated elections provide an outlet; authoritarian states who hold them face fewer coup attempts. They are as long-lasting as those who do not.Footnote 36

There are exceptions. In Belarus in 2020, Aliaksandr Lukashenka chose to unleash the biggest wave of repression in Europe since 1989 to try and end post-election protests. Over 30,000 were arrested in three months. Russia’s rulers in 2021 faced the dilemma of whether ‘smart’ authoritarianism was enough to contain a new wave of popular protests after the arrest of anti-corruption campaigner Aleksey Navalny or whether cruder forms of coercion were a more effective fall-back.

But it is often argued that so-called smart authoritarian states are more likely to use political technology alongside traditional hard power, police or military. In the place of traditional authority, authoritarian states also ‘manufacture consent’. Consent is passive, not expressed through the ballot box; but a country like Saudi Arabia, which does not have elections, can still use political technology to create or exaggerate the appearance of passive consent. And to troll opponents.Footnote 37 The royal court’s social media tsar Saud al-Qahtani has been labelled as the ‘troll master’, ‘Mr Hashtag’ and ‘lord of the flies’.Footnote 38 The activist film maker Bryan Fogel in his documentary The Dissident describes how Twitter is ‘the parliament of Saudi Arabia’,Footnote 39 an arena of struggle between government ‘flies’ and dissident ‘bees’. If there is more politics online than in authoritarian public space, then ‘digital repression’ – censoring and filtering the internet and social media, using bots and trolls to flood online information space, and using AI for citizen surveillance – is a complement to, if not an alternative to, traditional physical coercion.Footnote 40

China is a different type of authoritarian exemplar, even a political system that is reviving some of the ‘total’ control aspects of totalitarianism. China uses a range of interlocking technologies for grid rather than nodal control. China’s aim is mass surveillance not just dissident control; mass behaviour control and a ‘harmonious society’ (hexie shehui) rather than just pre-empting ‘mass incidents’ (quinti shijiàn) and preventing connective action leading to collective action. But this is not strictly political technology, given the definition above. Political technology is about manipulating manipulable systems. The purpose of Chinese digital authoritarianism is not to control politics or the political system, as there is no real public politics. Its purpose is control. Though some features of the Chinese system, such as the ‘50 Cent army’ of online trolls, fit the definition of (im)personation and message manipulation above. India is a better example of the use of political technology to manipulate the world’s largest democracy.

Political technology authoritarianisms, on the other hand, seek to undermine oppositional subjectivity in more subtle ways: by surrounding, isolating, confusing, drowning and faking opposition voices. This is the Russian model of patchwork control, which may be cheaper and more exportable to other authoritarian states than the Chinese model.Footnote 41

Other aspects of so-called ‘smart’ authoritarianism involve mimicking aspects of open politics. Having suppressed civil society and bottom-up structures in the past, political technology can recreate them from above. Authoritarian states also tend to be characterised by a general sense of anomie and an aversion to collective action. This helps smart authoritarian states to surround relatively isolated individuals with soft reintermediated structures. When authoritarian states allow some public debate but attempt to manipulate and control it, that would count as political technology. When authoritarian states create GONGOs (the oxymoron of ‘Government-Organised Non-Government Organisations’) or pseudo-independent political parties or organise pro-government rallies that are supposed to look real and independent, that would count as political technology too.

Hybrid Regimes

Academics like to talk about ‘hybrid’ regimes, somewhere between authoritarianism and democracy. One such model, developed by Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way, is ‘competitive authoritarianism’, meaning states that are still authoritarian, but that allow some carefully managed competition for power. ‘Such regimes are competitive, in that democratic institutions are not merely a façade: opposition parties use them to seriously contest for power; but they are authoritarian in that opposition forces are handicapped by a highly uneven—and sometimes dangerous—playing field. Competition is thus real but unfair’.Footnote 42 Political technology fits perfectly into this definition – the use of all means to make such carefully managed competition unfair.

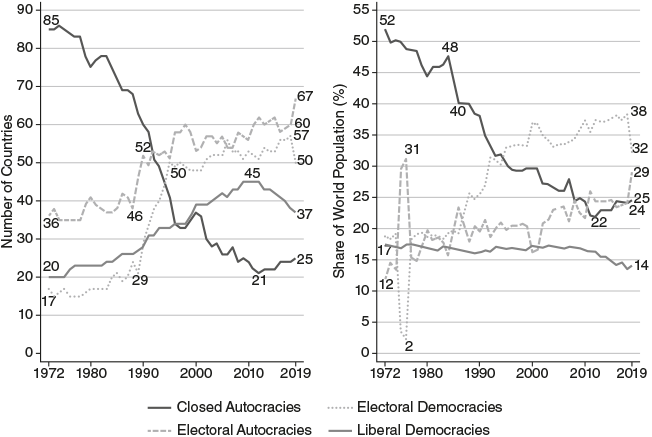

This book therefore argues that political technology is most common under competitive authoritarianism. And competitive authoritarianism is itself increasingly common. There are advantages to appearing to be democratic; pretending to democratise is much preferable to actually democratising. Throughout the world, the number of fake democratic ‘openings’ is higher than the number of real democratisations. Levitsky and Way counted 32 states as competitive authoritarian in 2019.Footnote 43 Since the Economist Intelligence Unit began its Index of Democracy in 2006, classifications have changed as follows (by 2019): the number of full ‘democracies’ had dropped from 28 to 20, but the number of ‘flawed democracies’ had barely changed, from 54 to 55; the number of ‘hybrid regimes’ saw a big leap from 30 to 39; the number of ‘authoritarian regimes’ was down from 55 to 53.Footnote 44 V-Dem uses a different classification; according to which 25 countries with 25% of the world’s population were ‘closed autocracies’, 117 were hybrid regimes, 67 ‘electoral autocracies’ and 50 ‘electoral democracies’, with 29% and 32% of the world’s population, and 37 were liberal democracies, with 14% of the world’s population.Footnote 45 It was hybrid regimes that had expanded to become the majority between 1972 and 2019 (Figure I.2).

Figure I.2 Regime types

On the other hand, competitive authoritarianism may be an unstable condition.Footnote 46 Managed competition may get out of control, leading to regime defeat or coercive over-reaction. One study shows that one in four rigged elections in competitive authoritarian regimes led to post-election protests.Footnote 47 The Political Instability Task Force showed back in the 1990s that significant and often obvious bias in ‘anocracies’, states with both democratic and authoritarian features, meant that they had twice the level of political instability or civil war as autocracies and three times that of democracies.Footnote 48 Political technology is therefore also one way of trying to maintain equilibrium – an equilibrium favouring the authorities – and prevent the loss of control. Authoritarianism under challenge may also resort to political technology. In the 2000s and 2010s, Belarus was an electoral authoritarian state that didn’t use much political technology. But mass protests against rigged elections in 2020 meant that it imported Russian methods to restore control, though the regime also used unprecedented levels of coercion (see page 362–4).

Hollow Democracies

Political technology also flourishes in deteriorating democracies; and democracies are decaying everywhere. Democracies are decaying at the bottom, with the decline of the cleavage solidarity that used to drive political beliefs, commitment and engagement. Many commentators have noted a decline in the institutions of civil society, like churches and clubs and particularly blue collar society, mutual, building societies and cooperatives. However, others see this as a consequence of greater female participation in the workforce and see activism moving elsewhere, particularly online.

Democracies are decaying in the middle. The classic institutions of mass democracy – political parties, popular participation, the mass media’s ‘fourth estate’ – are all in decline. ‘Disintermediation’ is the decline of intermediary institutions, the key buttresses of public politics. That decline is due first of all to long-term social and economic trends. Political parties no longer have mass memberships, nor do the trade unions and churches that used to feed them. Politics is increasingly personalised and individualised. There is also disintermediation actively sought. Some have sought to bypass parties in the name of participatory democracy, bypass the hegemony of the mainstream media that only ‘manufactures consent’ for capitalist oligarchy,Footnote 49 or empower diversity. The advent of the internet and social media has only accelerated that process. The social media generation only consumes free media, in relatively narrow bandwidth.

Germans talk of Parteienverdrossenheit – disenchantment with political parties. Their membership is falling; their ancillary institutions are declining or going their own way. The idea of a Volkspartei – a catch-all mass party, now sounds old-fashioned. Mass parties became TV parties and then digital parties. Germans also talk of Politikverdrossenheit – disenchantment with politics in general. Voter turnout is in long-term decline. According to research by the think tank International IDEA, average turnout in elections globally has declined from 78% in the 1940s to 66% in 2011–15.Footnote 50 Voters ‘trust in parties, political institutions, politicians and the mass media are all in decline. According to Pew data, trust in government in the United States dropped from 77% in 1964 to 28% in 1980, before falling further to 19% in 2017’.Footnote 51 As this decline is so steep and cumulative, its causes are many. There are cultural explanations (the decline of deference), economic factors (the end of the post-war boom years), and ideational changes (declining faith in elite managerial expertise). Governments themselves have actively destroyed trust, from Watergate to Iraq.

Democracies are decaying at the top. The core institutions of democracies have surrendered functions to an increasing number of rivals. First to international organisations like the EU. Yascha Mounk has written that ‘Liberal’ and ‘democracy’ are no longer co-equal.Footnote 52 Illiberal democracy is on the rise in countries like Poland; but there is also ‘undemocratic liberalism’ – economic and/or social liberalism cannot be challenged because it is enshrined in legal orders and/or international systems. According to Yanis Varoufakis, the intellectual Finance Minister of Greece at the height of the debut crisis, his counterpart German finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble said in negotiations: ‘Elections cannot be allowed to change economic policy’.Footnote 53

Democracies have lost power to technocracy, with the rise of independent central banks and rules-based, independent regulators, immune from democratic interference. In 2000, Colin Crouch called this ‘Post-Democracy’: the progressively narrowing number of decisions taken by mandated politicians rather than business, bureaucrats and technocrats.Footnote 54

Democracies have lost power to markets. Wolfgang Streek has argued that the post-war West managed to combine two representations, or markets and voters, until the 1970s. Since then markets have won out; and the activist ‘tax state’ has been replaced by a roll back of public goods, welfare, regulation and trade unions.Footnote 55 In 2007 Alan Greenspan, a year after his two decades as head of the US Federal Reserve, declared that we ‘are fortunate that, thanks to globalisation, policy decisions in the US have been largely replaced by global market forces. National security aside, it hardly makes any difference who will be the next president’.Footnote 56 The global economic crisis a year later revived demand for an activist state; but austerity accelerated the retreat of the state in other areas. The Coronavirus pandemic also had both effects.

Democracies have lost powers to judiciaries, both national and international. International law and human rights law is increasingly extra-territorial. As of 2022, the post-Brexit UK was still subject to the European Court of Human Rights; Russia had to be expelled. In the UK, long the home of parliamentary supremacy and the common law, judicial review has become an established principle; despite populist push-back against ‘judgeocracy’.

Democracies have lost power to international corporations, who pay little tax, and to international supply chains and geographically mobile businesses. Democracies have lost power to the international rich. Globalisation has accelerated the cannibalisation of the state in the West and assisted the growth of oligarchies. According to Gabriel Zucman, the amount of missing money held offshore in 2015 was $7.6 trillion, or 8% of all global assets.Footnote 57

Benjamin Bratton has argued that ‘the Stack’, the global meta-structure of the internet, is rivalling and even substituting for older forms of government and notions of sovereignty.Footnote 58 Governments have lost power to US-based but transnational social media platforms. Arguably, they themselves would meet the definition of political technology as ‘supply-side engineering of the political system’ given above. Internet and social media platforms are mentioned frequently in this book but have been excluded as objects of study in themselves for no other reason than space.

The political systems of the West were also weakened by the 2008 economic crisis; and have begun to display many of the same symptoms as the post-communist or developing worlds. Terms like ‘oligarchy’, ‘rent-seeking’ and ‘state capture’ were often Orientalised. But the same phenomena can increasingly be observed in the West. Trump and his clan privatised parts of the American state, foreign policy and justice systems. They reversed the always patronising assumption that the West helps countries like Ukraine to democratise. Rudy Giuliani’s activities in Ukraine encouraged corruption in the prosecution service, to seek kompromat on domestic American opponents, and sought to reverse corporate governance reforms in the energy sector by promoting corrupt business proxies.

Wherever the architecture of democracy is crumbling, political technology can exploit the vacuum by putting soft structures back up. One word that crops up throughout this study is ‘proxy’: artificial parties and artificial NGOs, astroturfing, trolls and sock-puppets online, third-party websites. Proxies can be created by direct engineering, when an engineer works on an object, but there is also reverse engineering, where you get the object to work on itself. You give people a version of what they come to think they want, but you manipulate them first. Reintermediation, putting structures back up, is what political technologists do. They set up alternative structures, proxies and channels that flourish in a vacuum. They might use technologies to overcome the gap between elites and masses to create new majorities, but they might just as easily seek to maintain the gap and elites’ freedom of manoeuvre. Political technologists are not the only actors in the apparent vacuum, but they are privileged and powerful, and often operate unseen.

The Mediatisation of Politics

One reason for the decline of institutions is that politics is now deeply mediatised. Daniel Boorstin argued that we had developed a media-centric culture as far back as 1962 in The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America. Jean Baudrillard provocatively argued that The Gulf War Did Not Take Place in 1991. It did; real events really happened. But Baudrillard argued that most people only experienced the media version of reality, which was just as real for them. Life as experienced through media is even more real than reality. The reality of physical perception has been replaced by the simulacra that make up hyperreality, the mediatised signs, symbols and representations that either never had an original referent or have lost touch with it.

Politics-as-media has been around long enough to go through several life-cycles. Dramatic changes have followed not just the advent of online media, but the changing technology and structure of that media. The 1990s era of desktop computers, dial-up modems and chatrooms was superseded by smart phones, Google, global platforms and algorithms. The 1990s Internet was good at conspiracy but not at mass propaganda. According to David Karpf from the School of Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University, ‘the exposure rate, the traceability, and the lateral impact of misinformation’Footnote 59 is now much higher in the age of global search and linkage, and social media. The remonopolisation of the internet in the 2000s has given the giant platforms ‘more profit and power in online disinformation’.Footnote 60 Moreover, in this second age of the Internet and social media, propaganda is no longer on the sidelines. Social media and mainstream media are intertwined: mainstream media comments on what is said online and is often led by it. Constructed hyperreality can attack reality. Anyone can own their own hyperreality. The online world is full of messagers ‘decrying the lack of coverage in mainstream outlets and demanding coverage of “both sides” of the manufactured controversy’.Footnote 61

Cultural Politics

As well as declining institutions, there has been a decline in the old ‘estates’. Voters are increasingly aligned by culture rather than by social position or class. Voting is driven more by education and by identity groups. ‘Voting patterns’ is either an anachronistic phrase, or the patterns are kaleidoscopic. Most radically, in Steve Bannon’s phrase, ‘politics is downstream from culture’. Culture is zero-sum, so cultural politics is, by definition, culture war. And war needs weaponry or political technology. Culture war is the new Leninism; the cultural vanguard is the driving force that aligns or realigns the slow-moving behemoths of old-fashioned Fordist politics. And politics is about telling stories that appeal to cultural groups, which privileges storytellers, many of whom are manipulators. Culture and cultural markers and boundaries are easier to manipulate than class or socio-economic conditions.

Quantum Politics

With weaker institutions and declining voter loyalties, politics is no longer as firmly anchored as it was. Structures are weaker. Vacuum is one metaphor. Another is the Italian writer Giuliano da Empoli’s idea of ‘quantum politics’. ‘Newtonian politics’, he argued, ‘was adapted to a more or less rational, controllable world, in which an action corresponded to a reaction and where voters could be considered as atoms endowed with ideological, class or territorial belonging, from which definite and constant political choices were derived’. ‘Liberal democracy’ was also ‘a Newtonian construction, based on the separation of powers and on the idea that it is possible for the rulers and the governed to make rational decisions, based on a more or less objective reality’. Under quantum politics, however, ‘objective reality does not exist. Everything is defined, temporarily, in relation to something else and, above all, each observer determines his own reality’. As da Empoli pointed out, US politician Daniel Patrick Moynihan famous claim in 1983 that ‘everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts’ was therefore outdated.Footnote 62

The old Newtonian world of reaction and counter-reactionand stable political parties and institutions has given way to a world of fluidity and perpetual recombination. Countries that look stable, like the UK before 2016, are vulnerable to disruptive technology, in this case the Brexit referendum that turned everything upside down. After the 2008 global economic crisis, there was much talk, mainly amongst the Western left, about the shifting of the ‘Overton Window’, the idea that public opinion might be radicalised, redefining the centre of what is regarded as ‘normal’ or even acceptable political discourse. Or, to put it another way, that the articulation of ‘hegemony’ might shift. This can happen when the public conversation shifts for long-term social, economic or cultural reasons, but that shift can also be organised from the top. Brexit shows how the political possibility set can suddenly be utterly transformed. Though the apparent beneficiary, the UK Conservative Party, was also disrupted. Weak institutions are particularly vulnerable. When the Conservative Party was the party of UK business, it would never have been taken over by the ideological Brexit cabal.Footnote 63 Before and after Brexit, it was led by the nose by proxy forces, while not one but two ‘entryist’ operations saw its depleted membership swelled by outsiders who then played a crucial role in the 2019 party leadership election, the 2019 general election and the Brexit dénouement (see page 245). The decline of traditional institutions and parties can lead to ‘PASOKification’ – overnight disappearance, as happened to the traditional Greek left-wing party PASOK after the 2008 debt crisis. New ‘pop-up’ parties might take their place, but also provide more opportunities for political technologists to exploit.

Post-Agora Politics

Disintermediation clears the ground for political technology. Pure direct democracy can only be glanced in the rear-view mirror. Modern democracies are large. The new paradigm is not George Orwell and information rationing and control, but Borges and Calvino – too much information overwhelming the isolated individual. One result is theatrokratia, ‘theatrocracy’ or ‘audience democracy’ in the words of Peter Mair – politics as spectator sport, in which we watch others perform.Footnote 64 Politics is also the rule of opinion, but the art of expressing opinion is what matters, the act of like or dislike and of condemnation or denunciation. But ‘democracy doesn’t really work if everyone wants to be an individual’.Footnote 65 It destroys the possibility of a public conversation, a res publica, an agora. Plato thought this effect would come from entertainment taking over politics, and it has.Footnote 66 The Bulgarian political scientist Ivan Krastev has talked of a ‘a democracy of fans … zealous, unthinking, and unswerving … rowdy adoration. Those who refuse to applaud are traitors, and any statement of fact becomes a declaration of belonging’.Footnote 67 Politics works like reality TV; all that matters is engagement. ‘Populists separate campaigning from governance. Their leaders are selected not for any governing skills but strictly for their ability to drive engagement’.Footnote 68 If all that matters is reaffirming group identities, then there is no general political conversation.

When we do act in the new media age, everyone wants to control their own narrative. The French gilets jaunes got angry that reporters were giving their own version of their ‘Acts’ and their selves. ‘The gilets jaunes spurned any narrative they weren’t in charge of, with thousands of hours of crowd-sourced uploads swelling their own radiant news bubble. They were the story and only they would tell it. This dislike of any mediation other than their own had a wild, hubristic edge’.Footnote 69 The key political value is authenticity, which is easy to fake. Truth has been replaced by ‘credibility’ or ‘truthiness’. Politics has become an open system. People from show-business compete with traditional politicians, because traditional politicians became technocrats and became boring.Footnote 70 Mass culture, comedy culture beats political culture. Politics has become performance art. Politics first became about ways to grab attention, then it became only about grabbing attention – the true nature of Trumpism. Boris Johnson had said, ‘If you’re not noisy, you’re politically dead’.Footnote 71

The silo effect of the internet and social media is well-known. People congregate with the like-minded. But more broadly the relationship between politicians and public is no longer conversational. The dissolution of the ‘myth of the attentive public’Footnote 72 gives politicians a radical new freedom. The audience in theatre politics is also manipulated. The characteristic art form of our age is the ‘Theatre of the Real’ – drama that blurs the boundaries between the stage and the ‘real world’: post-dramatic theatre, using documentary elements on stage, blending fiction and non-fiction in biopics or having both actors and the participants they play reminiscing in films like I, Tonya (2017) and American Animals (2018). This is predicated on the audience’s complicity in blurring the boundary between life and representation.

The new theatre politics follows a simple set of rules. The most important is to define yourself: your brand is your essence, so play a part. Donald Trump played the part of a successful businessman; though, as is often remarked, he is the poor man’s idea of a rich guy. Boris Johnson’s pitch is that he is from the elite, but not the part of the elite that hates you, the ordinary woman or man. The man whose birth certificate says Volodymyr Zelensky won the 2019 Ukrainian election, but really it was Vasiliy Holoborodko, the everyman history teacher he played in the hit TV series Servant of the People. Your chosen part should be larger than life, loud enough to drown out rival definitions of you and your politics. That is why so many new populists are quite literally loudmouths, with ‘a narrative of one noble individual versus their adversaries’.Footnote 73 The part that you play must also validate your supporters – you are OK. Hence the difficulty that commentators have in defining the new populism, which seems to be an empty signifier. This type of politics is not about content. Contemporary populism is performance art.

If politicians are performance artists, the next rule is therefore to stay away from traditional media, or they will define you. They will disrupt your performance. Use your own media instead: Twitter and Fox for Trump, Facebook and Instagram for Zelensky and The Daily Telegraph for Boris Johnson. You should also enlist cheerleaders; participatory propaganda is free propaganda. Only then might physical technology, bots, etc., be important for a final phase of amplification. The final rule is that none of this is any guarantee that you will be a success in office. So ignore the rules and carry on campaigning anyway.

The Politics of Narrative

One of the oldest truths known to man is the power of story-telling. In modern parlance, this is ‘narrative’. Everything needs a narrative nowadays, including political manipulation. Voter suppression is dressed up as ‘preventing vote fraud’. When Trump set up a ‘Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity’ after the 2016 US election, it was nothing but a counter-narrative to deflect attention away from voter suppression of legitimate citizens towards a myth of widespread voting by illegal migrants. It had no other substantive purpose.

A successful narrative is built on the abovementioned factors of emotive effect and in-group solidarity.Footnote 74 Disinformation, particularly conspiracy theory, has a certain pull; the thrill of privileged access to inside information or the identity politics of standing against the crowd, the ‘sheeple’. Narrative has momentum. It is the enemy of empiricism, even of fact. Like all globalisations, there is a winner-takes-all effect.

According to Boris Johnson, ‘people live by narrative’.Footnote 75 His foreign policy adviser John Bew has revived the Hegelian idea of zeitgeist – the dominant narrative of a nation at a given time.Footnote 76 Adam McKay and Adam Curtis have claimed that: ‘Information warfare is where we’re living now. More specifically, its story warfare’. Ironically, after the age of spin, ‘politicians have given up telling stories. They have nothing to say any longer’. ‘They’ve become managers’.Footnote 77 But the right has an advantage. It is happy to talk about power: ‘Left and liberals’ ‘have given up talking about power’. ‘They talk about polling and market testing, like they’re bad network executives. I have to tell them [Democrats]: the second you do that, you’re dead.’Footnote 78 The right are now the post-modernists, and have the stories that remain, or rather that have been revived: like nation and community. The emotional messages. ‘The left is scared of powerful narratives’.Footnote 79 It’s partly snobbery. They’re afraid of being crude and emotive. ‘But it’s also fear of the consequences’.Footnote 80 Nationalism didn’t turn out well.Footnote 81 The left used to use the language and cadences of the gospel, both in Britain and the United States. The famous quote that British socialism was about ‘Methodism not Marx’ was about style as well as ideology.

But stories still matter. If mainstream politicians don’t tell stories, it leaves the field open for those who do. The story becomes the reality. Take the example of Newt Gingrich at the 2016 Republican convention.

gingrich: The Average American, I will bet you this morning, does not think crime is down, does not think they are safer.

camerota: But we are safer, and it is down.

gingrich: No, that’s your view.

camerota: It’s a fact.

gingrich: I just – no. But what I said is also a fact…. The current view is that liberals have a whole set of statistics which theoretically may be right, but it’s not where human beings are. People are frightened.

gingrich: No, but what I said is equally true. People feel it.

camerota: They feel it, yes, but the facts don’t support it.

gingrich: As a political candidate, I’ll go with how people feel and I’ll let you go with the theoriticians.Footnote 82

According to the political consultant Arthur Finkelstein, in this age of grand illusion ‘the most overwhelming fact in politics is what people do not know, rather than what they do know. And in fact, in politics it’s what you perceive to be true that’s true, not truth’. ‘If I tell you one thing that’s true, you will believe the second thing is true, even though you haven’t a clue whether I’m telling the truth or not. That is the way politicians behave. And a good politician will tell a few things that are true, before he tells you a few things that are not true. Because you will then believe all the things that he has said, true and untrue.’Footnote 83 Donald Trump said ‘I love the poorly educated’.Footnote 84 Anthony Scaramucci, who was White House Director of Communications for all of eleven days in 2017, talked of targeting ‘low-information, emotional voters’.Footnote 85 Once elites no longer believe in the ‘attentive public’, they will act accordingly. According to Finkelstein again, people ‘get elected for the silliest of reasons’.Footnote 86

The Politics of Feeling, The Politics of Blame

No one is trying to persuade voters or citizens, just to play on, and to weaponise, their feelings.Footnote 87 According to former Cambridge Analytica CEO Alexander Nix, ‘it’s no good fighting an election campaign on the facts, because actually it’s all about emotion. The big mistake political parties make is that they attempt to win the argument, rather than locating the emotional centre of the issue concerned and speaking directly to that’.Footnote 88 Modern mobilisation politics is therefore about performance, about connection and about victory. It has very little to do with actual policy delivery. It makes perfect sense that Trump didn’t actually govern much. According to Finkelstein, what matters is emotional identification and rejectionist voting. Politics is ‘not an intellectual discourse’. Especially since 2008. ‘I tell you what we have to do. Throw them out. Get rid of these people. Pick the name of a group’. ‘These people are growing. They are growing on these issues. They will talk about the economy, but it’s not what they’re about. They’re about anger’. ‘Why do we pick one group over another to hate, and why do we single them out for the failures? The point is the economic crisis is severe, it’s creating an energy source, around which these movements take place’.Footnote 89

As the apostle of negative voting Finkelstein believed that most voting was ‘structural’: so loyalties had to be undermined by ‘rejectionist voting’.Footnote 90 Demonising your opponent also helped your base to come out and reject them. Personalise the enemy image: It helps to personify the enemy. It was better to fight ‘not against al-Qaeda, but against Osama bin Laden’.Footnote 91 The 2008 economic crisis, hr agued, created ‘real anger’, but ‘the anger is at the Mexicans. Not even all Hispanics — the Mexicans’.Footnote 92

Russia in particular has relied on successive enemy images to align a 70% ‘Putin majority’. The German theorist and Nazi party member Carl Schmitt is very popular in today’s Kremlin, for his notorious idea that a sovereign state, even the essence of politics, rests on the distinction between friend and enemy. Schmitt is popular in China too.Footnote 93 He is being rediscovered by US Republicans.Footnote 94 In the UK, Thomas Borwick, a key strategist for Vote Leave in the 2016 Brexit referendum, has said, ‘I believe that a well-identified enemy is probably a twenty per cent kicker to your vote. I believe that having a clearly-identifiable baddy is a vital part of increasing cohesion within your voting group, and giving them the impetus to kick someone out’.Footnote 95 ‘Politics is the art of constructing friends and enemies. You can’t do without it’.Footnote 96 Schmitt thought this was all about the collective identities of communities, and it still is. But it is also about the hyper-individualism of modern social media politics. You are no longer stuck with ‘others’. Maybe family, but not necessarily. Politics increasingly turns into a social media story, where you can ‘friend’ or ‘unfriend’ anybody. Brexit is ultimately an unfriending fantasy.

The Politics of Misdirection, The Politics of Conspiracy

Misdirection is another characteristic feature of political technology. The political class can exploit contempt for the political class, but shift it onto someone else, diverting genuine grievances towards the wrong solutions. This can best be done by giving the enemy magical powers. Classic conspiracy theory insists that things are not what they seem and gathers evidence – especially facts ominously withheld by official sources – to tease out secret machinations. The new conspiracism is different. It dispenses with the burden of explanation, imposing its own reality through repetition (exemplified by the Trump catchphrase ‘a lot of people are saying’) and bare assertion (‘rigged!’).Footnote 97 ‘Repetition’ is actually fake backgrounding: a ‘lot of people’ means Donald J. Trump, or the tweet he just read. Or it operates like a cult, inviting what Mike Rothschild called ‘autists’,Footnote 98 audience-researchers, to join the dots and identify secret patterns themselves.

The post-1968 cultural revolution has seen a decline in belief in official narratives and a reaction against ‘manufactured consent’. There is also the Watergate meta-narrative, which ironically is about not-trusting meta-narratives, as well as the assumption of conspiracy and ulterior motive. Initially, this came from the left; but has also been weaponised by the right in its campaign against science and against experts, as documented by Oreskes and Conway, (Merchants of Doubt, 2010) and Tom Nichols (The Death of Expertise, 2017). In the post-communist world, the equivalent narrative is that the system always lied to us, and it still is. Propaganda is now dressed up as ‘freedom from the media’ or ‘news with no agenda’. In the USA the anti-liberal Project Veritas hit on the idea that the public is obsessed with something that looks like a leak. Framing it as such, with covert recording techniques, especially if they are made to look amateurish, will create the story, as much or more than actual content.

The Logic of the Sect

The most powerful political narratives follow the logic of the sect. They have entry criteria and initiation rituals. Anne Applebaum has talked of the ‘Medium Size Lie’, such as the myth-making around the Smolensk tragedy in 2010 that killed the Polish President Lech Kaczyński and ninety-five members of the Polish elite. Not Joseph Goebbels’ big lie, but big enough to get supporters of the ruling party, orchestrated by his twin brother Jarosław Kaczyński, ‘to engage, at least part of the time, with an alternative reality. Sometimes that alternative reality has developed organically; more often, it’s been carefully formulated, with the help of modern marketing techniques, audience segmentation, and social-media campaigns’.Footnote 99

The logic of the ‘medium’ size lie is that it can be a bridge to bigger lies. Once you believe in Brexit or Climate Change Denial, you might believe in anything, but your beliefs are not based on truth. Once you have accepted Trump’s #StopTheSteal lie, that will structure how you look at everything else. You are required to accept the lie, or you are expelled from the sect, labelled as Republican in Name Only. ‘In elections going forward, not trying to steal the election will be seen as RINO behavior.’Footnote 100 Believers are also inoculated against counter-narratives; there is a narrative against those who will try to undermine the narrative.

The Technology in Political Technology

Today’s manipulators can indeed trace a lineage of sorts back to their predecessors in Machiavelli’s or Chanakya’s day. But there is more technology in political technology than there used to be. Dirty tricks used to involve getting your hands actually dirty. The Watergate crisis began in 1972 when actual burglars (nicknamed the ‘plumbers’) had to break into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, and were caught in the act of crude wiretapping. Their modern equivalents in 2016, the Russians who hacked first the DNC and then the Hillary Clinton campaign, didn’t have to leave their computers or their country to steal similar information. Before there was ‘voter suppression’ there were white mobs on voting day in Jim Crow states. Now African-Americans are subject to social media disinformation claiming they can vote at home.

This book will talk about bots and troll farms, about Big Data and psychometrics. But it is not about them alone. It is political technology, as much as actual technology, that is the engine of radicalisation. Political technology is the techniques that autocrats used to hold on to power or populists use to undermine democracy. Political technology benefits from recent technological revolutions; technology gives it more firing power, but political technology is really a culture of manipulation.

Structure of the Book