“Mistakes have histories, but no beginning—like, I suppose, history?”

—Elizabeth Bowen, The Little GirlsHalfway through Elizabeth Bowen's late, neglected novel, The Little Girls (1963), the brouhaha of a children's picnic by the sea pauses with the arrival of the much-anticipated birthday cake. Children who were building sandcastles and wading in the water rush back to the picnic spot. The birthday girl, Olive, eagerly leans over the cake to read her name. Everyone “surrounded the cake in a dense circle,” and the narrative builds up to the moment of the cake's unveiling: “All in silence looked down upon the inscription, written in curling pink sugar handwriting on the white iced top. Some had to decipher it upside down” (153). An image of the cake is intercalated between sections of the text (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. An illustration from Elizabeth Bowen's novel The Little Girls (153).

After much fumbling, party guests erect a makeshift barrier with coats to protect the cake from the wind, and Olive manages to light and blow out the candles. A flurry of violent activity then ensues. “Something about the destruction (for so it seemed) of the moment of the candles let loose not exactly disorder but an element of scrimmage about the party,” Bowen writes. Boys begin to tussle “cautiously but repeatedly,” and a girl “suddenly kicked [another] in the kidneys” (154). Eventually, the cake makes its rounds, and the grown-ups, who had been watching the events in stillness like “figures in a tableau,” become animated once again (155).

The temporal suspension brought on by the cake, and the brief but sudden “destruction” it causes, is a benign moment. Which child would not be temporarily agitated and get carried away by the promise of cake, in the most important moment of any birthday party? But the details are conspicuous and telling. Olive's birthday is less than one month after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, whom the main character, Dicey Delacroix, mistakenly and innocently calls “that Australian duke” (162). The party takes place five days before Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia—an event fearfully anticipated by Dicey's mother, Mrs Piggott, who asks another parent, “But there is not going to be a war, is there?” (158). The war is also foreshadowed by the narrator's pointed remark that, of the fathers present at the party, “[a]ll were civilians” rather than soldiers (151). The birthday party takes place in a mobilizing world, one whose tensions are coded and partially released through the outbreak of the children's localized violence.

The cake, whose icing suggests a “sort of victory wreath,” is also part of a retrospective wartime iconography, even while the wish of “many happy returns” takes on a hint of menace (153). The representation of wartime here is one of belatedness or future pastness, and it is further complicated by the way this scene is situated in the novel, wedged between two other sections set in the future. In the tripartite structure of The Little Girls, parts 1 and 3 take place in the 1960s, with middle-aged Dicey, now called Dinah, putting together a time capsule to “leave posterity some clues” (11). She then realizes that she had buried a coffer of secret objects with two childhood friends, Sheila Beaker and Clare Burkin-Jones, in a thicket of trees on the grounds of their school, St Agatha's, half a century earlier. Part 2 is a flashback to that pre–First World War past—or a narrative time capsule in which that past emerges in the mid-century present. Here, the novel details the burying of the coffer and the girls’ schooldays, including Olive's birthday party by the sea; the party is revealed to be the scene of the girls’ final parting, along with that of Clare's father and Dinah's mother, who share an unspoken romance. In part 3, the women, reunited in late middle age, return to disinter the buried coffer, only to find it inexplicably empty.

The Little Girls, then, is not about the conflict of 1914–18 specifically but about an understanding of modern wartime that is somehow imminent, recursive, recurring, and ongoing, all at once. This is driven home by the way Bowen layers other wartimes onto the pre–First World War past, including the Second World War, in which St Agatha's is blitzed “[i]nto thin air” (76), and the Cold War, when nuclear apocalypse is held tenuously at bay. As Dinah surmises while assembling her time capsule, “Those early races probably never thought; or what I suppose is still more likely, never really expected they would vanish. But we would be odd—don't you agree?—if the idea'd never occurred to us” (11). Her companion, Frank, echoes these sentiments: “We may all go out with the same bang” (13). The Little Girls was published months after the tense period of the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, and its themes and historical surround concern “a peace that is no peace,” in George Orwell's famous phrase (26).Footnote 1 A text that is as much about the past as it is about the future, it is about wars begetting other wars, about a condition of always expecting future wars that will have happened.

This vexed temporality is captured by Olive's birthday cake, intertwined with the strange emphasis of the cake's inscription on the anxiety of interpretation and reading. For the cake not only evokes the iconography of the First World War. If we are to “decipher” the cake upside down, as some of the party guests do, the image presented is eerily evocative of one belonging to the Cold War instead: a mushroom cloud.

Affects of Lateness: Between Late Modern Wartime and Anthropocene Time

Bowen's text continually gestures toward temporalities outside its narrative present, and this has consequences for the text's interpretation in its future—our present. The relationship between the time of writing and the time of reading is something that preoccupied Bowen herself: “For the writer, writing is eventful; one may say it is in itself eventfulness. … Reading is eventful also” (Afterthoughts 9). Although critics have typically focused on the “eventfulness” of her notoriously belabored prose, on the way her writing's jerky rhythms and grammatical contortions themselves constitute a formal reading event, this article layers that understanding of eventfulness, particularly in relation to Bowen's late prose, with two others.Footnote 2 First, if an event is an event because it punctuates, in some measure, the flow of everyday time, then literature is itself a medium for a particular kind of transtemporal encounter.Footnote 3 How does the event of reading transform that which is already written, and how does the already written take on different afterlives? Second, as Gilles Deleuze has argued, an event can only be understood as evental in anticipatory or retrospective terms; that is, the temporal significance of an event derives from our ability to see it outside its own present. “What is going to happen? What has just happened?” he writes in The Logic of Sense. The event is “always and at the same time something which has just happened and something which is about to happen; never something which is happening” (73). For Deleuze, a relationship to futurity is at the heart of the event.

How do these three ways of understanding eventfulness—as the labor of reading and interpretation, as a meeting between the time of writing and the time of reading, and as that which enfolds futurity, whether imminent or distant—characterize our encounter with Bowen's novel, in our contemporary present of environmental crisis? I begin with the novel's preoccupation with a belated wartime, not necessarily to “prove” that Bowen had indeed intended to invoke the mushroom cloud through the birthday cake, but to consider how and why the novel's style lends itself to such strange evocations of temporal porosity: moments when the writing seems to stretch beyond a single context and time, its meaning multiplied, remade, and folded back onto itself. I argue that this quality makes The Little Girls, in its concern with an extended late modern wartime and its search for a posthuman narrative form, uncannily expressive of the temporal fears of our own age of the Anthropocene, as we ourselves grapple with the environmental legacies of the mushroom cloud.

When I speak of late modern wartime, I am referring to wartime in the period of late modernism, which, according to critics, spans from the interwar period up to the late twentieth century.Footnote 4 Despite covering many decades and several global conflicts, late modern wartime is characterized by an undercurrent of anxious anticipation. This observation is typical of the Cold War, which was “defined in reference to an imaginary,” Mary Dudziak writes, because its full substantiation would mean nothing less than apocalypse (69). Recent works, however, have taken the imaginary itself as the structure of feeling that provides a through line for thinking across modernist wartime and Cold War time, rather than as a point of departure between the two. Jan Mieszkowski in Watching War, for example, has linked the aftermath of the First World War to the Cold War by tracing the intertwining of economic and military realms with the discourse of total war. Paul Saint-Amour in Tense Future has identified the injurious effects of anticipation as central to interwar modernism, thus connecting it to the temporal dread associated with the Cold War. Teasing out the idea of a “Cold War modernism,” Marina MacKay writes, “[T]o think about modernism, war, and violence is to consider not simply how literature responds to past events but its orientation toward events to come” (141). An overall affect of late modern wartime concerns a vexed relationship to the future.

Yet there is a distinct kind of historical pressure on the mid-century moment. Saint-Amour's formulation of the “perpetual interwar”—“the real-time experience of remembering a past war while waiting and theorizing a future one”—captures some of this sentiment, since the First World War led to the Second World War, which in turn mutated into a chilly third (305). But with technological advancements in nuclear weaponry, the phenomenology of violence in mid-century wartime tipped into longer timescales. This became most apparent with the principle of mutually assured destruction, which inflected mid-century wartime with a profound sense of posthumanism. Jacques Derrida remarked that any future after total nuclear destruction is unwitnessable: by “being-for-the-first-time-and-being-for-the-last-time,” nuclear war can only be imagined, but there can be no possibility of retrospection, and no “symbolicity” (26, 30). This more extensive temporal reach of Cold War time—which involves imagining (or trying to imagine) a literally posthuman future, a future after humanity as we have known it—needs to be reckoned with in accounts of late modern wartime.

The mid-century feeling of temporal finitude relates to what Joseph Masco calls “the nuclear uncanny”: “a psychic effect produced, on the one hand, by living within the temporal ellipsis separating a nuclear attack and the actual end of the world and, on the other, by inhabiting an environmental space threatened by military-industrial radiation” (29). While the end of the world may no longer feel as imminent as it once did, we are currently faced with another temporal ellipsis, another psychosocial and material space, brought on by perceptions of a tightening noose instigated by our own geological footprint—an anthropogenic uncanny. As Ian Baucom observes, contemporary climate reporting involves scales that shift back and forth between our present moment and its relationship to deep time, but it always tends “toward a catastrophic result” and a “ruinous future direction” (5). In Roy Scranton's words in Learning to Die in the Anthropocene (2015), “We're fucked. The only questions are how soon and how badly” (16). We are used to thinking of our future as already imperiled and compromised, our present crisis as already belated.

Affects of lateness, therefore, undergird the confluences between late modern wartime and Anthropocene time.Footnote 5 In fact, Saint-Amour's other memorable turn of phrase is instructive for thinking about why this is, when he suggests that perpetual wartime involves a kind of “pre-traumatic stress syndrome” (7–8). The psychological effects of future trauma are figured in similar ways by critics of our planetary condition. In her book Climate Trauma, E. Ann Kaplan highlights the idea of “pre-trauma” or “pre-traumatic stress syndrome” (PreTSS), arguing that PreTSS's symptoms—including hallucinations, paranoia, and depression—populate a spate of contemporary dystopian works seeking to represent “a kind of ‘memory of the future’” (3).Footnote 6 Building on Kaplan, Michael Richardson examines the affective ways that contemporary cultural production, through aesthetic form, perceives “the rupturing arrival of an apocalyptic futurity” to make sense, in the here and now, of the climatological future we will inhabit (3). Both late modern wartime and Anthropocene time genuflect to a version of trauma that departs from the psychoanalytic model of ruptural past events, instead zeroing in on the psychological debilitations of the future as felt in the present.

The conjunctions between late modern wartime and Anthropocene time emerge as more than just the result of ecocritical interpretation, however. Certainly, Baucom and others have forcefully argued that the world situation has necessitated a rethinking of existing methods of critique. Since the Anthropocene “is more than a name for a new chronology or a new set of historical dates,” but indeed a kind of historical consciousness and a way of being in the world, the argument goes, it makes certain demands on the way we do literary criticism (Baucom 50).Footnote 7 But the historical context and stylistics of Bowen's novel point to more specific ways in which the text is affectively, if anticipatorily, about the Anthropocene. While Anthropocene literature tends to be understood in terms of science fiction, there is striking resonance in Bowen's ostensibly realist melodrama for the “urgent new historiographic regime” of how we read and inhabit the Anthropocene (Baucom 46). This has to do with the second dimension of the nuclear uncanny identified by Masco: the material space and atmosphere of late modern wartime, when mid-century life came to be contaminated, both imaginatively and phenomenally, by military-industrial radiation. In The Little Girls, the problem of radiation appears as a problem of spatial and temporal imagination, as the relationship between the human and nonhuman, and as what can and cannot be articulated, affectively and formally, in Bowen's late style.

The Matter of Radioactive Time

Many have noted that The Little Girls sits oddly within Bowen's oeuvre as a follow-up to the apparent apex of her literary career, A World of Love (1955). Spencer Curtis Brown (Bowen's literary executor) and Neil Corcoran have suggested that Bowen's writing climaxes with A World of Love; these and other critics have argued that The Little Girls evinces a style that departs from her earlier work.Footnote 8 Her penultimate novel appears to represent a turn toward late style in the Saidian and Adornian sense of a writing defined by “intransigence, difficulty, [and] unresolved contradiction” (Said 3).Footnote 9 However, the question of late Bowen and her “evental” late style is imbricated with her apprehension of lateness as a condition of historical self-understanding in the 1960s, when “predictions of apocalypse were a significant milestone in the development of environmentalism” (Bramwell 54).Footnote 10

My epigraph from Bowen suggests that mistakes have multiple histories but no clear beginning; The Little Girls intersects with one beginning, out of many beginnings, of the Anthropocene. The Anthropocene Working Group—the body tasked with examining the Anthropocene as a potential addition to the Geological Time Scale by the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy—notes two periods of deep anthropogenic impact: an “early” Anthropocene, which dates back to 1750 BCE and early agricultural practices, and another tied to the dawn of the Industrial Revolution around the beginning of the nineteenth century. But it is the “Great Acceleration” of the mid–twentieth century that appears to be the most unprecedented in terms of speed and extent of change (Zalasiewicz et al.). The latter witnessed an enormous amount of human activity with environmental impacts, including the creation and widespread dispersal of human-made materials like plastic and aluminum. The Working Group, though, is most concerned with the spread of radionuclides from nuclear testing. Marking the boundary between the Holocene and the Anthropocene, the mushroom cloud continues to accrue new significance, new affective anxiety, in our present.

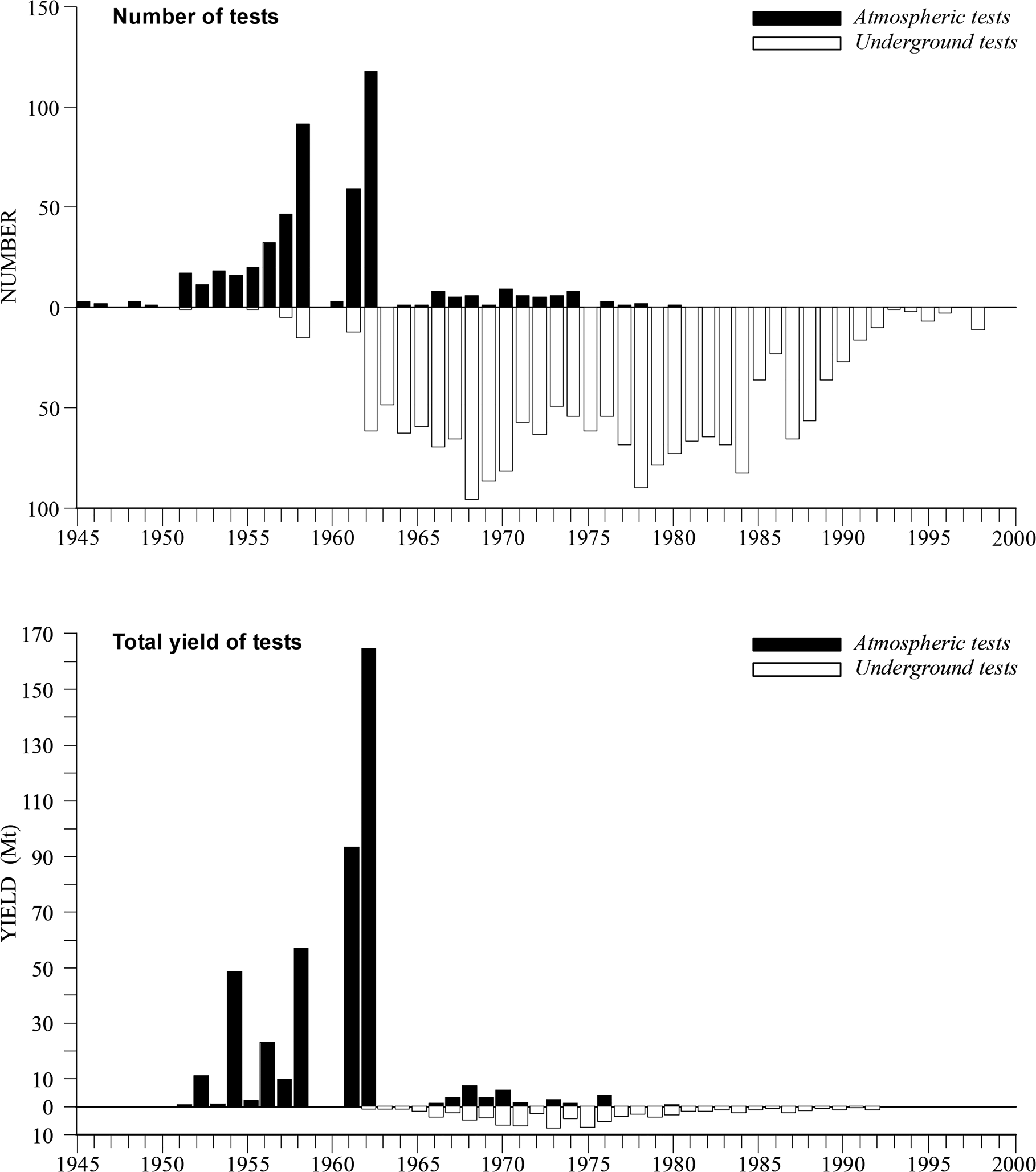

The environmental impacts of nuclear testing have been well documented. Although “only” two nuclear bombs were detonated at Nagasaki and Hiroshima, the United States exploded sixty-six nuclear devices between 1946 and 1958 in the Marshall Islands and elsewhere in the Pacific Ocean. Some one hundred aboveground detonations occurred between 1951 and 1963 at the Nevada Test Site, not to mention the 828 underground detonations that took place in the same site, up until 1992 (Beck 178 [fig. 2]). A huge effort surrounding uranium extraction characterized these decades, as the material was essential for the nuclear transformation of matter. And like the bombs produced out of it, uranium mining creates radioactive dust that is airborne—a fact corroborated by the Project Sunshine research reports of the 1950s, which aimed to examine the long-term effects of radiation on the biosphere. Project Sunshine found evidence of radioactive isotopes in the tissues and bones of the deceased around the world, among the other impacts of fallout.Footnote 11

Fig. 2. Time line of the frequency of atmospheric and underground nuclear weapons testing from the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR). Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation, vol. 1, United Nations, 2000, www.unscear.org/unscear/en/publications/2000_1.html.

The authors of “When Did the Anthropocene Begin?” identify 16 July 1945, 5:29:21 Mountain War Time, as the beginning of the Anthropocene. This was the moment when the Trinity A-bomb detonated at Alamogordo, New Mexico (Zalasiewicz et al.). While other scientists have quibbled over the specific year, they also corroborate that nuclear testing is a significant temporal marker for the Anthropocene. The authors of “Can Nuclear Weapons Fallout Mark the Beginning of the Anthropocene Epoch?,” for example, suggest that the Alamogordo test marks the beginning of the nuclear age but lacks a radiogenic signature in the geological record. For them, the Anthropocene begins, not with the detonation of the bomb, but with nuclear weapons fallout, and the pronounced rise in plutonium dispersal that is detectable over the entire Earth, from around 1952 (Waters et al.).

These contexts need to be considered in relation to Bowen's novel, which appeared at the height of the Cold War and shortly after the Project Sunshine reports. One can say that The Little Girls is set during a period with a very different relationship to “airmindedness” (Bowen, To the North 142). Bowen had coined that term in the 1930s, in her novel To the North (1933), to refer to a consciousness about aeriality and the aerial view enabled by developments in military and civil aviation. Air continued to be a crucial image and trope in her writing of the Second World War, when aerial bombardment concretized a modern culture of “atmo-terrorism” in which war is waged by, through, and with significant impacts on the air (Sloterdijk 23). From short stories like “Sunday Afternoon” (1945), where the cold air menacingly “fretted the edge of things” in neutral Ireland (616), to the opening scene of The Heat of the Day (1949), where music travels through an open-air theater, connecting characters in a blitzed London where “you breathed in all that was most malarial” (92)—in Bowen's writing of the 1940s, to be airminded is to be ever conscious of how air can be both life-sustaining and damaging. By the late Bowen of the 1960s, airmindedness would become a phenomenal and primordial concern, and what Peter Sloterdijk calls the “explication” and violation of one's own “lifeworld” would be at the heart of environmental politics (47). The Little Girls even alludes to, or foreshadows, nuclear fallout when the girls leave the site of the buried coffer: “The outside world, when they had left it, had been extinct rather than, yet, dark. On the ledged hill, as for the last time they looked down, a rain of ashes might have descended” (146).

Late Bowen, though, takes the anxiety underground. The Little Girls is far more preoccupied with the earth as its elemental image and metaphor. Dinah's time capsule is variously described as a “bear pit,” “a shallow cave or a deep recess—or possibly, unadorned grotto” (3), a place where “one does get forlorn …, though without noticing” (16). The mysteries of the novel lie not in the atmosphere of ashes, but in the world of the subterranean and entombed where the empty coffer would be discovered. This anxiety echoes an attendant switch from above to below, from aerial to sepulchral, in the sociocultural imagination, which figure 2 documents. The switch occurs in the same year that the novel was published, the year of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963, when surface-level A-bomb testing ceded to underground testing.Footnote 12 Part of this was a result of Project Sunshine, which proved not only that radiation was airborne but also that its effects, given radioactive isotopes’ long half-life, could last for tens of thousands of years.

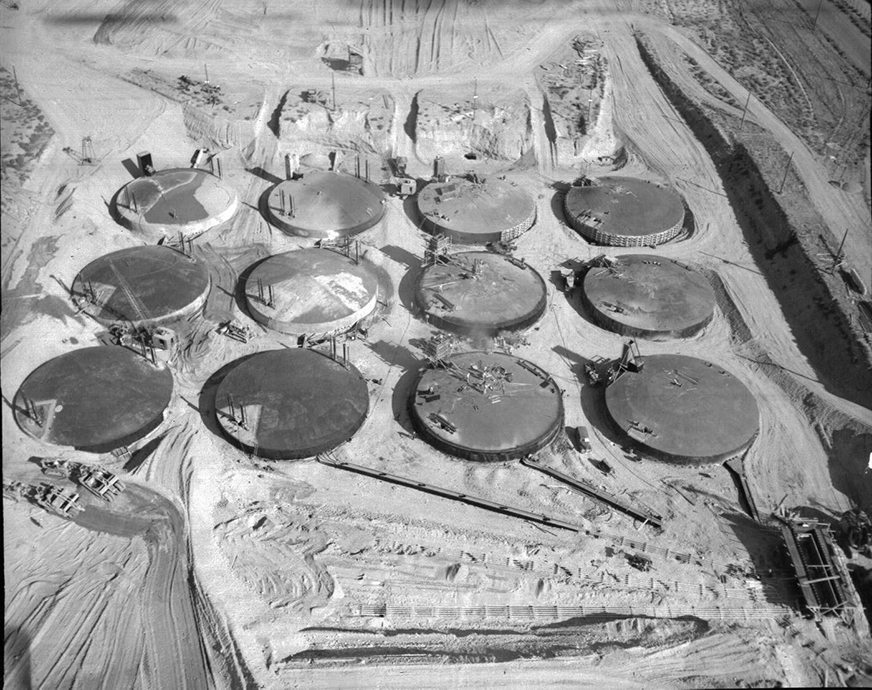

The move to underground testing did nothing to eliminate the deep effects of radiation: it only covered them up. There was also the related problem of underground nuclear waste repositories, which contained, but could not eradicate, the effects of radioactivity. For example, the most contaminated radioactive reservation in the United States, Hanford, in Washington State, was home to nine nuclear reactors from 1944 to 1987. These reactors produced plutonium for making atomic weapons, and some 177 underground waste storage tanks still contain extremely radioactive nuclear material (fig. 3). The tanks continue to be leak-prone: more than a million gallons have already leaked over the decades, and at least one has been actively leaking since 2013. Because the site is located near the Columbia River, the largest in the Pacific Northwest, its nuclear waste continually threatens water supplies and agriculture in the region (Johnson; Habad et al.).

Fig. 3. Hanford's underground storage tanks. Source: United States Department of Energy, 2013.

Although the menace shifted from the atmospheric to the subterranean, it actually meant that one understanding of injurious time was replaced with another: the human time in which atmospheric fallout could at least be partly evidenced was succeeded by the deep time of the geological, when the earth itself became a radioactive burial site concealed from contemporary eyes. Underground testing not only created immediate problems, ranging from radiation contamination of groundwater supplies to earthquakes and tidal waves stemming from underground explosions; it also, given the long half-life of radioactive isotopes, created a deadly fate for generations in the deep future who may not know of the “ancient” radioactive material buried underground. In nuclear testing, both the air and the earth contain the matter of what Adam Piette calls “radioactive time” (102).Footnote 13 The aerial and sepulchral imaginaries of Bowen's novel speak to an anxious period when wartime effects went from “global” to “planetary”—planetary in the least metaphoric, and most ordinary, sense. It was the period when weapons testing meant mobilizing for war as well as maintaining peace, and when its effects extended beyond the geopolitical to the geological.

Inscrutable Time: Elizabeth Bowen's Time Capsules

The deep timescale of radioactivity puts a certain kind of pressure on literary narrative for Bowen, and the complex relationship between temporality and narrative is freighted with meaning in The Little Girls, which is about late modern wartime, extinction, and lateness but also about what recent critics have identified as an obsession of contemporary Anthropocene texts: the narrative capacity to express finitude on posthuman scales, and the pretraumatic stress that this entails. Pieter Vermeulen identifies “two lines of thinking about the future of the human” in the Anthropocene: one that embraces “speculative realisms, object-oriented ontologies” and another that focuses on the “agential force of humans on their environments” to intensify “human responsibility” (868). For him, a key problem is narrative, which seems “fatally anthropocentric, and … out of sync with the nonhuman rhythms of the Anthropocene” because it is “intrinsically connected to the all too human desire to make sense of things” by sequence or pattern (868). (We might think here, for instance, of Paul Ricoeur's classic declaration “Time becomes human time to the extent that it is organized after the manner of a narrative; narrative, in turn, is meaningful to the extent that it portrays the features of temporal existence” [3]). These three things—the nonhuman, the human, and the mediating role of narrative—are not new in Bowen's oeuvre by any means.Footnote 14 But they come together in unique ways in mid-century wartime, or mid-century wartime changes what the relationship between them means.

The question of the human is crucial to understanding how the nuclear uncanny intersects with the anthropogenic uncanny, and why literary histories of the Cold War and the Anthropocene are intertwined. Early nuclear writing by American authors, such as John Hersey's classic Hiroshima (1946), often called “the first nonfiction novel,” focused on the atomic bomb's physical and psychological effects as they were felt by a handful of survivors; in doing so, this writing humanized the devastation for its American audiences at a time when the Japanese perspective was still neglected in the United States (Lemann). By the 1960s and the height of the Cold War, nuclear writing became connected to issues of ecological disaster and global warming, and the human experience was seen as increasingly inconsequential, given the scale of the catastrophe anticipated. J. G. Ballard's The Drowned World (1962), for instance—a founding text of “cli-fi” published one year before Bowen's novel—is set in the postapocalyptic future of 2145. It is notable not only for its setting—a world pervaded by floods and tropical temperatures—but also for a coolly detached narrative style in which the characters’ agency is repeatedly undercut by the enormity of the ecological devastation that surrounds them. In her reading of the text, Rachele Dini suggests that Ballard “approaches ecological disaster as a narrative problem,” since “the human's role in the aftermath of anthropogenic disaster is fundamentally irrelevant.” Focusing on Ballard's representation of waste, she writes, “[I]t is the stuff that [people] leave behind, what happens to it even after its producers have vanished, that warrants attention” (3).

Both of these aspects, the material by-products of human activity and humanity's feared irrelevance, underpin Bowen's novel, and they are most obvious of course in the central conceit of the time capsule—a trope recycled throughout her oeuvre. It appears, most explicitly, in “The Happy Autumn Fields” (1944), in which a box from the Victorian past is blasted into view by a blitz bomb. Other, more abstract iterations of time capsule–like objects abound, especially as letters that are misdirected, misread, or recovered across time, like those in the envelopes discovered by Leopold in The House in Paris (1935); those in “The Demon Lover” (1945), which instigate an extended flashback to the First World War; or those from the First World War that then appear in the mid-century setting of A World of Love.Footnote 15 The time capsule provides a through line for reading Bowen not only within the earlier modernist contexts for which she is best known—Anglo-Irish decline, the two world wars—but also within the nascent posthumanism of the mid-century. Although many of her earlier works echo one another, The Little Girls is especially conspicuous in its recirculation of the author's narrative preoccupations. It revolves around mainstays of Bowen's oeuvre, such as female companionships, parental relationships, and childhood themes, which are key to texts like The Last September (1929) and The House in Paris. Like the latter novel and many of her short stories from the 1930s and 1940s, The Little Girls concerns the trauma and legacies of the First World War, often brought to the surface through flashback. And again like The House in Paris, it features a three-part time-capsule structure where narratives of the present or future bookend a central section set in the past.Footnote 16

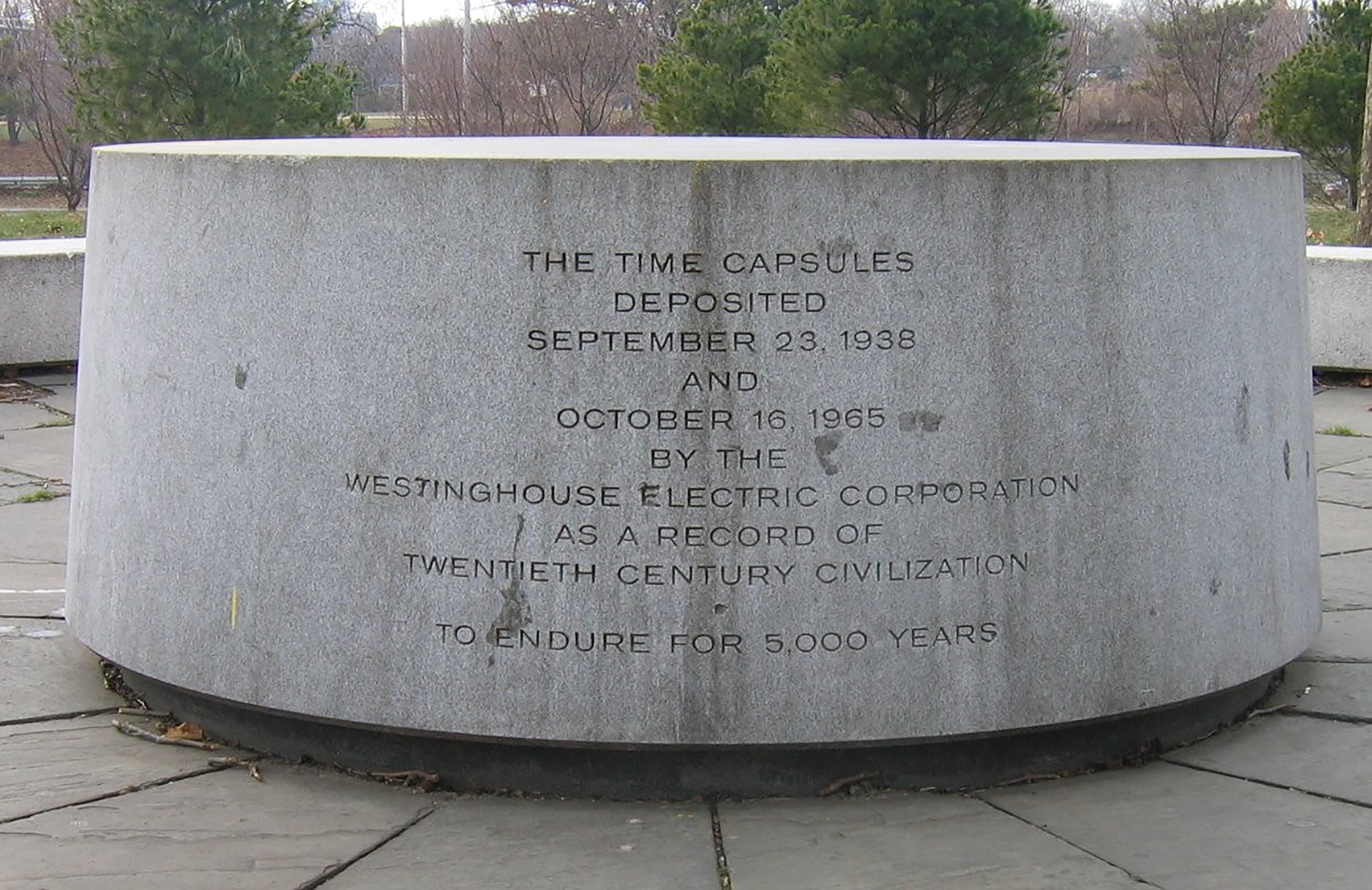

Bowen herself had buried a time capsule at her school as a child, and she claims she did not remember it until she wrote The Little Girls.Footnote 17 However, there is another time capsule, not in Bowen's past, but in her present: Westinghouse Electric's Time Capsule II, which was buried at the 1964 New York World's Fair.Footnote 18 It resides next to its predecessor, the Time Capsule of Cupaloy, buried at the 1939 New York World's Fair. Both are intended to remain undisturbed until the year 6939 (fig. 4). Despite the technocratic futurism of the 1939 New York World's Fair, whose theme was “The World of Tomorrow,” the Time Capsule of Cupaloy bears imprints of the geopolitical instability of the 1930s, including microfilm recordings documenting the mobilizing of the Soviet army, as well as footage of Canton being bombed.Footnote 19 Its ethos was already bleak: “[T]here is no way to read the future of the world: peoples, nations, and cultures move onward into inscrutable time,” its record book states. “In our day it is difficult to conceive of a future less happy, less civilized than our own” (Westinghouse 5). This hope for the future would be almost impossible to sustain by 1964, when the desire to produce a representative record of modern civilization would have more total, and more apocalyptic, implications. Where the earlier time capsule included a message from Albert Einstein to “men of the future,” in which he speaks of his worries about impending war, Time Capsule II featured the physicist's 1939 letter to President Roosevelt describing the endgame of atomic weaponry (Saint-Amour 181). The feeling given by these messages, indeed, is that of belatedness.

Fig. 4. Marker of Westinghouse Time Capsules in New York. Photograph by Doug Coldwell. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike license.

As the antinuclear theorist Günther Anders wrote in 1960:

However long this age may last, even if it should last forever, it is “The Last Age”: for here is no possibility that its “differentia specifica,” the possibility of our self-extinction, can ever end—but by the end itself. … Thus, by its very nature, this age is a “respite,” and our “mode of being” in this age must be defined as “not yet being non-existing,” “not quite yet being non-existing.” (493)

For Anders, living in “The Last Age” means moving toward death—not natural or individual, but violent and collective, one self-inflicted by humankind. Existence is marked by creeping or imminent nonexistence. He therefore meditates upon what, if any, significance human agency has in this inexorable whirlwind toward catastrophe. Titled “Theses for the Atomic Age,” the essay recalls “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940), written during the prior global conflict by Anders's cousin Walter Benjamin. Benjamin's essay propounds historical materialism as a way of understanding the historical past in relation to the present, and Anders expresses a similar kind of commitment to a historically conscious present. The Atomic Age is not just the age of catastrophe but the age in which “[t]he Time of the End could turn into The End of Time” (494). Anders therefore surmises that “we must do everything in our power to make The End Time endless,” to extend the condition of belatedness so that it becomes the new, enabling condition for existence itself (494).

Time Capsule II is one way of attempting to surpass the End of Time, to allow for human time to transcend its own temporal limitations. But while humanity will inevitably end at some point in the future, the planet itself carries on existing in some way. The End of Time is only the End in one sense—that of humanity—for there is another time that is always already endless, the planetary temporality of the nonhuman. This fact bears on contemporary debates about the Anthropocene, which, according to Dipesh Chakrabarty, are often still mistakenly invested in human time. “Anthropocene debate entails a constant conceptual traffic between Earth history and world history,” he writes, “but humanists and social scientists tend to privilege the latter over the former, especially when they speak of the Anthropocene in relation to the impacts of industrial capitalism or the uneven economic histories of modernity” (“Anthropocene Time” 6). However, as Jan Zalasiewicz writes, a “peculiarity of geological time” is “that, at heart, [it] is simply time—albeit in very large amounts”: “A time boundary (whether geochronological or chronostratigraphical) is just an interface in time, of no duration whatsoever—it is less than an instant—between one interval of time (which may be millions of years long) and another” (124). Geological time is a temporality without duration in both the chronological and philosophical sense: a temporality without human meaning, and without what Henri Bergson called la durée.

This kind of temporal understanding is fundamentally impossible to grasp, because it involves imagining the world without us, when such an act cannot occur without our being there to do the imagining. And this is a problem for the “humanising powers of narrative” itself (Vermeulen 878). “In the early twenty-first century,” Vermeulen argues, “narrative has become one of the places in which human life, even while it tries to make sense of its existence, rehearses the inevitability of its extinction, as well as its posthumous readability” (880). He identifies the common trope of the posthumous reader who is left to “read” the traces of past civilization (872). But if we read differently today in the age of the Anthropocene, it is possible to see echoes of our anxiety in earlier narratives. And if literature is an encounter between the time of the written and the time of the read, we can read The Little Girls as an act of historical materialism but also within a historically thick context of the conjunction between the End of Human Time and the time of the Anthropocene's imaginary etonym, Anthropos kainos—“the time of the new man” (Boes and Marshall 62). In this reading, Cold War–specific worries about extinction, belatedness, and posthumanism are brought into relief by present-day anthropogenic belatedness. But as shown by the Doomsday Clock, the histories of the Cold War and the Anthropocene are connected: started by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists in 1947 to measure how close we are to human-made catastrophe, the Doomsday Clock now includes not only nuclear risk but also climate change as the primary threats to continued civilization.Footnote 20

Cold War time and Anthropocene time thus share the predicament of (post)human time and the anxiety of portraying “the features of temporal existence” (Ricoeur 3). This anxiety is at the heart of The Little Girls, because, like Anders, it does not give up on humankind or forfeit the meaning of human life, even though extinction would mark humanity as nothing more than a blip in geological time. Despite the possibility of everyone's going with the same bang, Dinah's time capsule differs from Time Capsule II by insisting on representing individuals, rather than civilization as a whole. She wants “expressive objects,” those that evoke a person's “really raging peculiarity,” and certainly not anything handed down by ancestors. Through her time capsule, she hopes to “leave posterity some clues” from which “to reconstruct us” (11)—not humanity but individual people: “I do think we deserve to be thought of as personalities” (10). Even while assembling this capsule, though, she realizes that, in the far future of her grotto, individuality will not matter: “I suppose the fact is, people are much the same, if one goes down deep,” she admits. “All the variety seems to be on the surface” (9, 4). This tension between individual peculiarity and species generality, between lived time and “simply time”—a time simultaneously prehistoric and posthuman—is articulated through a second hallmark of Bowen's late style, in addition to that of recycled tropes: the attempt to write “externally.”

With The Little Girls, Bowen told Spencer Curtis Brown that “she for the first time deliberately tried … to present characters entirely from the outside. She determined never to tell the reader what her characters were thinking or feeling” (Brown xxxviii). She described the text as “a story told in plain terms, without adumbrations or analysis” (qtd. in Ellmann, Elizabeth Bowen 195). The commitment to externality, to “showing,” is at times extreme. The little girls, for instance, are sometimes referred to by their nicknames, Dicey, Sheikie, and Mumbo, but at other times, they are described impersonally. Clare, in particular, is repeatedly referred to as “the Army child” or “the soldier's child,” both in the pre–First World War section (93) and in the mid-century present (306). She is defined by her relationship to her father and to wartime; her personality appears inconsequential. At other points, characters are depicted as object-like themselves. Part 3 features an extraordinary exchange among the women in which they are described in relation to the objects in the room: “‘Comme ci, comme ça,’ said the occupant of the settee. … The settee's owner said, drily: ‘Comfortable, I hope?’ … The third of them, wheeling round, cried: ‘You are there, Mumbo?’ … ‘We all shall feel better shortly,’ guaranteed the hostess, making for the cabinet in which bottles were kept” (207). We are given clues as to who the characters are—Mumbo is Clare, the hostess is Dinah, but the effect is dehumanizing. Nevertheless, there are still incursions into feelings, histories, and inner dialogue throughout, notably in the novel's conclusion, when the “soldier's child” looks at bedridden Dinah in a moment of reconciliation: “I did not comfort you. Never have I comforted you. Forgive me” (306, 307). Victoria Glendinning is critical of this stylistic “failure”: “Elizabeth could not at the end keep to her policy of not giving her characters’ thoughts” (221).Footnote 21

Bowen's writing style oscillates unevenly between interiority and exteriority, personality and impersonality. The narrative even employs free indirect discourse that ventriloquizes the thoughts both of a character and of the inanimate environment. The scene after Mrs Piggott spots Major Burkin-Jones by the coast, for example, is charged with intense feeling across both human and nonhuman realms:

All the more in the early dusk of the garden stood out the sun-saturated and noble beauty of this man. Everywhere was breathless, heavy syringe bushes increasing the look of hush. … Along or above this coast, one could not both be sheltered and have a view—there now, though, was a view from Feveral Cottage: Major Burkin-Jones. The neglected grass of the lawn, already growing up into seed, created a sort of pallor round his feet: nothing splashed anywhere with colour, except where a meagre delphinium leaned through ferns or ungirt cabbage roses turned purple pink. This came to be a garden like none other—or was it always, perhaps? The moment could, at least, never be again. Or, could it—who knew? Happy this garden would be to have such a revenant, were he ever dead. (103–04)

The treatment of Major Burkin-Jones—the world around him is “breathless” and “hush[ed],” and his golden stature stands out against a dying, weedy lawn—suggests both his vivacity as well as that of Mrs Piggott's erotic longing. It foreshadows the same depth of unspoken feeling at the “wordless inquiry” of the two's final farewell (167). At the same time, the ostensible subject of the passage is not Mrs Piggott at all but the garden that is breathless and heavy, the natural environment that grows around the Major's feet and that honors him with the single delphinium.Footnote 22 The garden became “like none other” with the singularity of his presence, but because of the inevitability that this man will be killed in war, the garden was “always, perhaps” going to be like this. Reversing the relationship between the subject and object as the agent—“happy this garden would be to have such a revenant”—Bowen's diction strains to recuperate human time from nonhuman time but could only end its portrayal of Major Burkin-Jones with that final word, even in life: dead.

Pent-up emotions, unconsummated desire, the intrusion of history into private lives, all articulated through contorted syntax: this passage is vintage Bowen. Yet its reversal of subject and object, animate and inanimate, seems to take on new meanings in the End of Time. Furthermore, in the Anthropocene's “time of the new man,” and in the current age of anthropogenic thinking, Bowen's late style gives expression to the ungraspability of extinction and to a particular kind of narrative affect that attempts to reconcile human time with not only nonhuman time but also posthuman time. This is clearest in scenes concerned with the time capsules themselves, like those in Dinah's cave, where Dinah assembles and houses her mid-century receptacle: “Down here … it was some other hour—peculiar, perhaps no hour at all” (5). But even the earlier coffer speaks to the way the radioactive time of the mid-century has altered the longer timescales of which they are a part. When the women return to disinter the coffer, its discovery is described in eerie and posthuman terms, with the women on one side, and the nonhuman narration on the other, of a boxlike void:

“Not that it will be there.” “How do you know?” “How can it be there?” It was there. It was empty. It had been found. (201)

The passage captures that particularly inscrutable but anxious quality of radioactive time, whereby human and nonhuman time are spatialized—the former above, the latter below. The women's search for meaning is underpinned by a narrative that insists on the fact of “simply time,” of a posthuman duration in which things simply happen without explanation or significance. The characters are indistinguishable, rendered as disembodied voices, and the natural and inanimate world responds to their incomprehension: “As the garden descended, a statuette of Pan or some unknown faun … and a shell-shaped bird bath floated one after another on the illuminated darkness. … Dinah, putting down the pick, knocked against a tree which with a creak gave out an ancient shiver” (201–02).

The tree's shiver is anthropomorphic, but it actually suggests something far less human, and far more agential on the part of the natural world. For the shiver has its origins earlier, in the scene when the coffer was first buried by the little girls:

The reader's mask was reflected, monkish, over the lit scroll. The lips parted. One by one, intoned, came forth Unknown syllables. … Someone shivered against a small tree: a tennis ball fell. The reader ceased. The ball, startled, fled down the sloping ground. …

The shiverer, controlling the shiver, asked: “How are we to know this is what we said?”

“Do you want this Unknown, or do you not?”

“Not.”

“All right. Put out the torches.”

They did. Having vanished, she spoke:

‘“We are dead, and all our fathers and mothers. You who find this, Take Care. These are our valuable treasures, and our fetters. They did not kill us, but could kill You. Here are Bones, too. You need not imagine that they are ours, but Watch Out. No wonder you are so puzzled. Truly Yours, the Buriers of This Box.”’

… The tree which again recorded a shiver can have harboured no other tennis ball, for none fell. (147)

The tree has recorded a shiver from one of the little girls, and released it back to them at mid-century. It also appears to have transported and released an object from Bowen's novel three and a half decades earlier, and from another wartime—The Last September, in which socializing rituals such as tennis matches are upheld as distractions by the Irish Ascendency to keep the looming violence of the Irish War of Independence at bay. Of The Last September, Kelly Sullivan observes, “It is the suspense of the non-catastrophe—the anticipated event that never happens—that most urgently permeates Bowen's writing.” The reappearance of the tennis ball in The Little Girls points to the mid-century difference, as the anticipated noncatastrophe suggests belatedness on a different geographic as well as temporal scale. As in the scene of the unearthing, the characters are disembodied, indistinguishable, and interchangeable; any raging peculiarity is lost to the nonhuman world, where torches and tennis balls are participants in the burial as much as the little girls. The misplaced modifier in “Having vanished, she spoke” suggests the girls’ own vanishing along with what they will entomb.

The burial scene has a number of readings and interpretations, not least because we are later told that the box contains a pistol owned by Dinah's father (who, in another instance of traumatic parental death, is revealed to have killed himself by lying under a train before Dinah was born [248]). The pistol represents the future's inheritance of violence from the past, an idea that the novel's Cold War present corroborates. Crucially, because the coffer is revealed to contain nothing, the narrative suggests that the little girls’ previously imagined future from the pre–First World War past has been obliterated or made extinct by mid-century wartime. But if the suggestion is also that the act of burying means bequeathing a premonitory danger to the future, then the message written in blood, “Watch Out,” speaks not only to the future of the First World War, and its begetting of future wars, but also to the radioactive time of the 1960s—and beyond.

For the coffer scene resonates with what is now called nuclear semiotics: an interdisciplinary field of research that aims to produce intelligible and survivable warning messages—with a life span of up to ten thousand years—to deter human interaction with nuclear waste repositories in the far future. In the example of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, located twenty-six miles east of Carlsbad, New Mexico, a “Futures Panel” of interdisciplinary academics convened to decide how best to communicate with future societies about the location and dangers of underground radioactive waste. A “Markers Panel” was also charged with developing design guidelines for warning markers to be placed, since “[t]he evolution of existing cultures and the creation of new ones over the next 10,000 years cannot be known. Thus, a marking system and the messages … [m]ust be rooted in basic human concepts and understanding” (Trauth et al. 3-3). Nuclear semioticians searching for an extralinguistic form of expression to ward off future humans from nuclear sites have turned to various pictogram-based signage systems—such as skull-and-crossbones signs and present-day radiation and emergency-exit symbols—as well as hostile architecture.Footnote 23

Although the little girls’ coffer is meant to be found rather than concealed forever, the girls ruminate on how to communicate with the future; one character even points out that their message may be futile because posterity “may have no language” (148). The problem of writing is linked to the problem of reading. The past is figured here not only as dangerous but as having imparted an injurious legacy—“You who find this, Take Care. … They did not kill us, but could kill You.” Even though the novel is concerned with the recovery of the past, it is also deeply ambivalent about what such a recovery may mean for the far future. And like those Cold War narratives that grapple with how to express extinction and posthumanism in their very forms, Bowen's narrative is concerned with the problem of “posthumous readability” during a very different, yet related, context within the multiple histories and beginnings of the Anthropocene (Vermeulen 880).

Of nuclear waste, John Beck writes, “While nuclear war promises to end time, radiation lasts a long time, and the dilemma of how to imagine the persistence of contaminated matter surviving intact for thousands of years is barely more manageable than conceiving the devastation of nuclear war itself” (179). This joint failure of temporal imagination—the end of one time, the persistence of another, and the human consciousness that “look[s] ahead to when we are a vanished race”—conjoins the pretraumatic affects of late modern wartime and Anthropocene time, and comes back to us, like a disinterred time capsule, in Bowen's late style (Bowen, Little Girls 10). It comes back to us in the novel's meditation on a complex temporal trifecta: a feeling of irreversible catastrophe, a sharpened awareness of deep time, and, in spite or because of this, an obfuscating and confounding relationship between human time and nonhuman time. A kind of miniature time capsule of her prior work, Bowen's novel, and our recovery of it, demonstrates how the time, space, and act of disinterment can alter the meaning of objects from the moment of their original encryption, and how the meaning of our own present is changed in the process.