Introduction

Mental health is ‘a state of mental well-being that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realize their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community’ (World Health Organisation, 2025). A mental illness or mental disorder is a condition that is clinically diagnosable and significantly impacts one’s ability to think, feel, and interact with others (Department of Health and Aged Care, 2012). Whilst there are individual risk factors which contribute to a person’s mental health, the COVID-19 global pandemic highlighted that mental health is significantly impacted by external social factors. The pandemic also highlighted the need to shift away from institutional-based care to community care, with a need for integrated interdisciplinary care to deliver prevention and early intervention and coordinated care for chronic conditions (Murtagh et al., Reference Murtagh, McCombe, Broughan, Carroll, Casey, Harrold, Dennehy, Fawsitt and Cullen2021).

Primary healthcare is an inclusive, cost-effective strategy that aims to organize and improve national health systems so that health and well-being services are easily accessible to all communities (Bolt et al., Reference Bolt, Ikking, Baaijen and Saenger2019a; World Health Organization, 2024). It follows a non-diagnostic, holistic view of a person and their care, which aligns with the values of occupational therapy (Muir, Reference Muir2012). Primary care is a subset of primary healthcare. It serves as the first point of contact an individual has with a health system (The World Health Organization, 2024). Primary care encompasses a wide range of public, private, and non-government services. Primary care providers include general practitioners, nurses, and allied health providers (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2025), including occupational therapy. This report considers the setting of primary care rather than the broader concept of primary healthcare.

Primary care is the ideal practice context for using an integrated, non-reductionist and multidisciplinary approach to a person’s health. This holistic view of a person can be highly effective in therapy (Ee et al., Reference Ee, Lake, Firth, Hargraves, de Manincor, Meade, Marx and Sarris2020). Occupational therapists work with people and communities to enhance their ability to engage in their desired occupation, that is the things they want to do, need to do or are expected to do, which give their life meaning and purpose (WFOT, 2012). Two recent reviews considered the role of occupational therapy in primary care (Bolt et al., Reference Bolt, Ikking, Baaijen and Saenger2019b; Donnelly et al., Reference Donnelly, Leclair, Hand, Wener and Letts2023). Both these reviews concluded that there is a role for occupational therapy in primary care, but further work is needed to define and promote the role, with potential to shift from an individual intervention focus to a preventive, community-based approach. Neither of the reviews drew specific conclusions regarding the occupational therapy’s role in primary care in supporting people with their mental health.

Occupational therapists work with people with mental health challenges to support full participation in life. Occupational therapists may also use their skills to work in generic roles such as case managers and group facilitators (Sammells et al., Reference Sammells, Logan and Sheppard2022). When assuming these roles, occupational therapists retain their occupational focus, prioritizing their client’s daily activities and emphasizing practical aspects of role performance and well-being while helping them overcome practical barriers and to develop skills (Occupational Therapy Australia, 2023). Occupational therapy’s unique contribution to mental health services lies in recognizing the complex interplay between client factors, activity demands, and environmental contexts and in examining the relationship between physical and mental health (Burson et al., Reference Burson, Fette and Kannenberg2017). Occupational therapy has historically been challenging to define in general mental health settings (Wilding, Reference Wilding2009; Parker, Reference Parker2001) and in specific settings such as primary care.

Methods

The broad research question for this report was: What is the role of occupational therapy in providing mental health services in primary care? To provide a structured search strategy, the authors followed Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping study framework (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) excluding the final optional step of consultation which has been deferred until the research identified through this review is conducted. Due to the limited literature available, Levac et al.’s (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien2010) recommended approach of an iterative approach to identifying studies and extracting data was followed, resulting in a narrative review of the included literature.

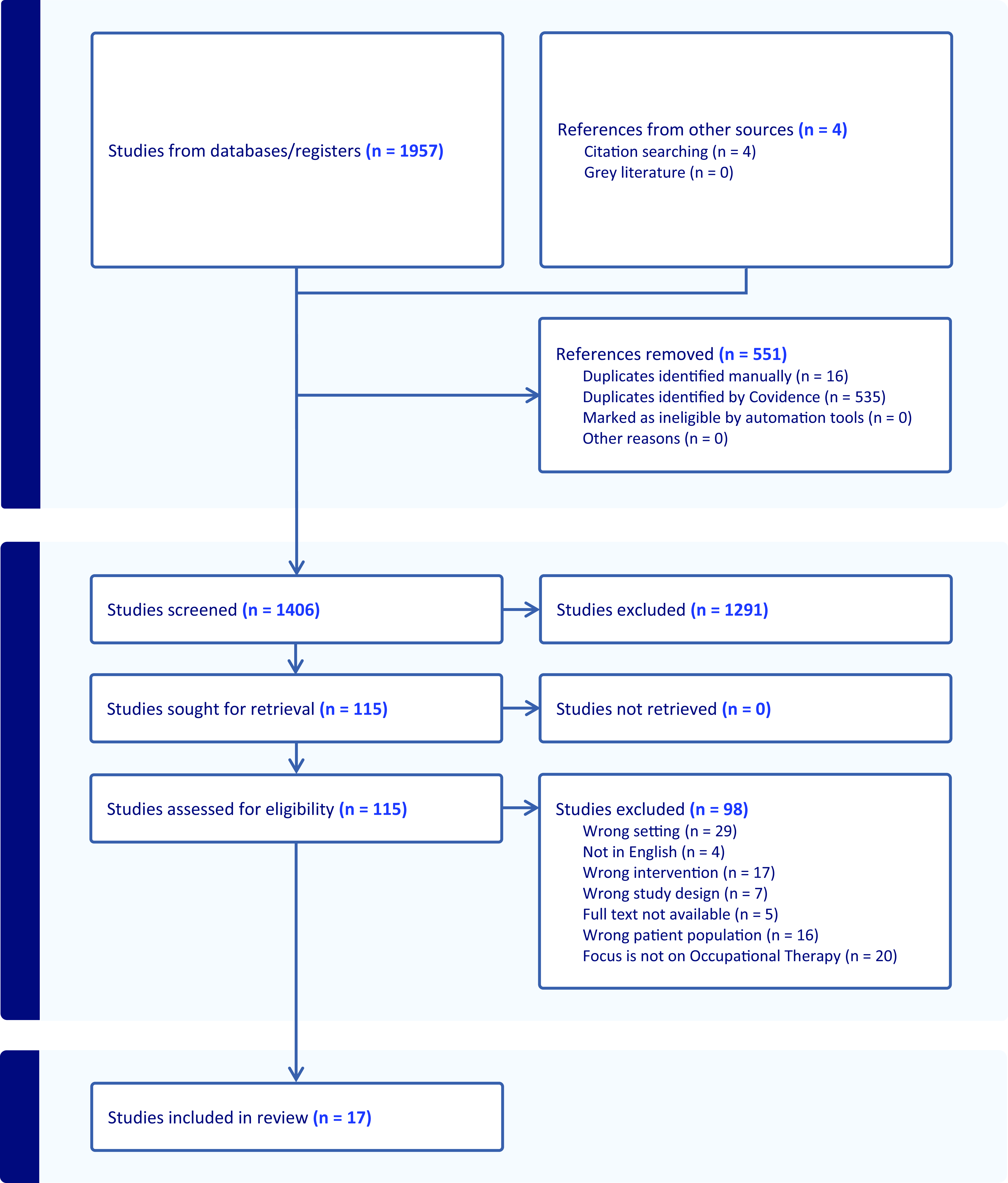

Online databases CINAHL Plus, Medline, Academic Search Ultimate, APA PsycInfo, and Web of Science were used to gather relevant literature. Articles not published in English and abstracts for which no full text was available were excluded. No limitations were placed on an article’s publication date or country of origin. Search terms used in this literature review are as follows: ((‘occupation* therap*’ OR ‘occupation* science’) AND (mental OR psychological OR psychiatric OR anxiety OR depression OR psychosis) AND (‘primary health care’ OR ‘primary health care’ OR ‘primary care’ OR ‘public health care’ OR ‘community care’)). Studies were included if they considered the role of occupational therapy with clients of all ages, with mental health issue, in a primary care context. The articles were screened by the first author and checked by the second author. The screening process is summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2024 flowchart of articles identified and screened in Covidence (n.d).

Results

A total of seventeen articles were included in the final review. A summary of the articles can be found in Table 1. Four common themes were identified across the included literature: 1. Variation in the definition of primary care used by occupational therapists; 2. Balancing generic and profession-specific roles; 3. Prioritization of physical health; and 4. Common interventions

Table 1. Articles included in review

Variation in definition of primary care used by occupational therapists

An exploration of available research indicated a discrepancy in how primary care was defined in relation to the role of occupational therapy. Two case study designs examining the categorization of generic and profession-specific interventions and the engagement of people with enduring psychotic conditions (respectively), used the terms ‘primary care’ and ‘community mental health care’ interchangeably (Cook, Reference Cook2003; Cook and Howe, Reference Cook and Howe2003).

More recent articles have echoed this difficulty with the definition and use of ‘primary care’. Donnelly et al. (Reference Donnelly, Leclair, Hand, Wener and Letts2023) addressed this issue using a scoping review format to examine occupational therapy services in primary care. The article described the apparent discrepancy in how occupational therapy defines and understands primary care. Gallagher et al. (Reference Gallagher, Lyons, Houston and Cummins2016) was the only article that actively discriminated between primary care and community mental health care, examining the differences in roles and perceived barriers and enablers to occupational therapists in Irish care settings working with clients with a diagnosis of depression.

Balancing generic and profession-specific roles

The interventions described across the included literature could be categorized as either a generic psychological or support role or an occupational therapy-specific role. This splitting of roles further blurs the perceived work of an occupational therapist in primary mental health care. The generic case management roles often offered to occupational therapists in primary care (Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Lyons, Houston and Cummins2016), which may also be offered to health professionals with a background in various disciplines such as social work and psychology, may allow for a more flexible role for occupational therapists (Scanlan and Hazelton, Reference Scanlan and Hazelton2019). The generic role may give room for substantial work within the multidisciplinary team, ensuring the integration of skills from other professions, such as cognitive behaviour therapy (Harrison, Reference Harrison2003; Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Batten and Richmond2015). Cook and Howe (Reference Cook and Howe2003) distinctly differentiate between care management and occupational therapy, despite both roles being conducted by occupational therapists in the study. Cook (Reference Cook2003) explores the profession-specific or generic role debate in the United Kingdom, investigating the interventions undertaken by occupational therapists in a primary healthcare setting. It was found 40% of tasks fell into the category of generic care management. Cook et al. (Reference Cook, Chambers and Coleman2009) examine occupational therapy treatment in a similar setting, describing components of intervention as generic due to their requirement by all members of the multidisciplinary team. This highlights the necessary nature of some aspects of generic care management, such as risk management (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Chambers and Coleman2009). While older articles, Cook and Howe (Reference Cook and Howe2003), Cook (Reference Cook2003), and Cook et al. (Reference Cook, Chambers and Coleman2009), provide substantial insight into the two often competing aspects of primary care occupational therapy in mental health.

Interestingly, Gallagher et al. (Reference Gallagher, Lyons, Houston and Cummins2016) echoed Cook (Reference Cook2003) in emphasizing the pressure to work generically and the associated role blurring. Gallagher et al. (Reference Gallagher, Lyons, Houston and Cummins2016) found that community mental health occupational therapists view their role as more of a specialist than that of a primary care occupational therapist. Primary care was seen as a general area, with occupational therapists engaging in general care management. In contrast, community mental health and secondary care were seen as a specialist role, addressing complex presentations. Trentham et al. (Reference Trentham, Cockburn and Shin2007) highlight the need for an occupational perspective to inform all aspects of work in occupational therapy, which is often lost when occupational therapists engage in generic roles in mental health.

In a two-part ethnographic study of an occupational therapist working in a newly established community mental health team, Harrison (Reference Harrison2005a; Reference Harrison2005b) uncovered a strong belief that specialized training such as cognitive behavioural therapy gave occupational therapy the credibility that was felt to be much needed with a move away from occupational therapy specific assessments. Harrison (Reference Harrison2005a; Reference Harrison2005b) emphasizes the uncertainty of the role of occupational therapy in primary mental health care, with the use of generic roles to give validity to the work of occupational therapists in this setting.

Prioritization of physical health

Much of the literature described difficulty working with clients with mental health concerns, with primary care not seen as a practice area suited to working solely in mental health. Mental illness is rarely the sole health concern in a person’s life (Bolt et al., Reference Bolt, Ikking, Baaijen and Saenger2019b), with physical illness highly prevalent in primary care spaces (Salisbury, Reference Salisbury2012). This is exemplified in Bolt et al. (Reference Bolt, Ikking, Baaijen and Saenger2019b)’s description of interventions undertaken when working with individuals with mental health concerns and chronic pain. Chamberlain et al. (Reference Chamberlain, Truman, Scallan, Pike and Lyon-Maris2019) described the benefits of the holistic approach often favoured in primary care settings as allowing for an exploration of all aspects of clients while reducing pressure on general practitioner services. The lifestyle intervention practised with individuals with panic disorder is an example of utilizing this holistic approach, focusing on the individual’s fluid intake, diet pattern, exercise, and intake of caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine (Lambert, Reference Lambert2012).

In their review and discussion of emerging practice models in the United States, Muir et al., (Reference Muir, Henderson-Kalb, Eichler, Serfas and Jennison2014) sees primary care as an emerging model of practice fit to address both physical and mental health needs, explaining the role for both as enabling engagement in daily activities. However, Gallagher et al. (Reference Gallagher, Lyons, Houston and Cummins2016) emphasize the difficulties in integrating an occupational therapy practice that focuses on and makes little distinction between physical and mental health. The article, set in an Irish primary care practice context, uncovered issues in prioritizing physical health rather than mental health, with mental health issues seen as more time-consuming and less of a focus of their practice. Despite 90% of primary care occupational therapists interviewed in the study showing strong interest in addressing depression, confidence in assessing and providing intervention to those with depression was low (33.4% and 17.9%, respectively).

Common interventions

Many articles discussed common interventions used by occupational therapists working with individuals with mental health concerns; however, these were often either guided by specific diagnoses (Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Lyons, Houston and Cummins2016; Cook, Reference Cook2003; Cook and Howe, Reference Cook and Howe2003; Cook et al., Reference Cook, Chambers and Coleman2009) or were broad and not explicitly focused on primary healthcare (Trentham et al., Reference Trentham, Cockburn and Shin2007; Daaleman et al., Reference Daaleman, Wright and Daaleman2021). Gallagher et al. (Reference Gallagher, Lyons, Houston and Cummins2016) and Eichler and Royeen (Reference Eichler and Royeen2016) discussed the use of formal information-gathering tools and assessments, such as the Model of Human Occupation and the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM). These assessment tools, as well as informal information-gathering processes, are used by occupational therapists to evaluate an individual’s environment, function, and skills. Daaleman et al. (Reference Daaleman, Wright and Daaleman2021) used a systematic review to examine interventions used by occupational therapists in primary care settings. Five studies were examined, which used various interventions, including work-directed rehabilitation through activity analysis, individual counselling to ensure readiness for work, physical activity, diet recommendations, goal setting, and psychoeducation. Similarly, Bolt et al. (Reference Bolt, Ikking, Baaijen and Saenger2019b) identified supported employment as a crucial role of an occupational therapist in primary care. Focussing specifically on mental health, the interventions used included psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, and assertiveness through graded activity training.

While Eichler and Royeen (Reference Eichler and Royeen2016) is a commentary article, it provides interesting information on an informal case study in which a client with heart-related symptoms repeatedly ruled out as a physical condition was referred to an occupational therapist for probable anxiety. The occupational therapist used the COPM to assess his level of function and listened as the client spoke of his difficulties and dissatisfaction with his leisure skills. After developing goals with the occupational therapist, the client and the occupational therapist created a plan for de-escalating anxiety. The occupational therapist worked with him to identify several strategies that could be implemented within his current life and environment and discussed situations where he may apply the strategies. Despite the lower level of evidence, the article provides the most detailed description of a mental health intervention used by an occupational therapist in primary care. Even when compiled with other evidence from this literature review, a solid, well-rounded description of the role of an occupational therapist working with clients with mental health issues is still lacking.

Discussion

While definitions of primary care and primary healthcare exist and are used in a general setting (World Health Organization, 2022), a definition of primary care in an occupational therapy setting has not been discovered in this literature review. Without this comprehensive, widely used, and accepted definition, difficulties in understanding the practice setting of articles lead to further issues in exploring the role of occupational therapists. To help readers understand a study’s findings and relevance to real-world practices, researchers must offer clear descriptions of the primary care setting and provide context about the healthcare models or services being studied. Without this, issues in understanding the role of occupational therapy in these settings and difficulties in researching these settings will remain.

The use of both generic and profession-specific roles in occupational therapy in primary mental health care leads to a further blurring of the role of occupational therapy in primary mental health care. The lack of occupational focus often seen with generic case manager roles creates isolation from the identity of occupational therapy (Ceramidas, Reference Ceramidas2010). It adds to the difficulty in understanding the role of occupational therapists in this setting.

While a holistic approach is a core value of occupational therapy, it is evident that occupational therapists in primary care lack confidence in working with people with mental health concerns. When an intervention is used in mental health, it often falls into a generic lifestyle approach, focusing on diet and exercise, without examining root causes or deeper issues relating to a person’s mental health. This approach when working with people with mental health concerns and the hesitancy in working with these communities often leads to a prioritization of physical illness creates further barriers to a cohesive definition of the role of occupational therapists in primary mental health care settings.

Limitations

This report was based on a descriptive summary of the literature and therefore did not include quality appraisal or risk of bias check.

Conclusion

Primary care settings exemplify ideals of equity, accessibility, and holism, which align with the professional values of occupational therapy. Occupational therapists are well-equipped to work with people with mental health concerns to support their participation in everyday activities that bring them meaning and purpose. This literature review illustrates a clear gap in the understanding of the role of occupational therapists working with people with mental illness in primary care settings, exacerbated by role blurring due to occupational therapists undertaking generic support and case management roles, and the prioritization of physical health in primary care. Further research is indicated which describes how occupational therapy may be most effectively utilized within a primary care setting and which examines any system or structural boundaries to integrating the role.

Funding statement

No funding was received for this research.

Competing interests

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical standards

This research did not require ethical approval.