After a new pregnancy was announced, families threw themselves into preparations for the birth and speculated about what the baby would be like; whether it would be a boy or girl, whether it would be large or small, and whether it would be good natured or ‘dull’. In the same ways that elite married women wilfully interpreted certain bodily signs to mean they were pregnant and calculate when they were going to deliver, this same prognosticating impulse was turned to looking for outward signs that would reveal the unborn child’s nature. Women’s bodies, like the records that families kept of conception and pregnancy, and the material items they gathered for the birth and after-birth period, were part of an embodied culture of display in which swelling bellies and the imagined large lusty infants contained within them were thought to represent families’ burgeoning prospects. Individuals engaged in a process of collective imagining, which defined the emotional and social boundaries of the family and household, and simultaneously policed women’s conduct. To refuse gifted or lent items or fail to participate in the written practices of predicting threatened to open rifts within families. The things that households gathered and the written records that they created during this phase formed an important body of tangible things that defined the family in question as godly, reputable and fruitful, and placed childbirth right at the centre of domestic life. As with reckoning, male family members were very much active participants in this imaginative and material preparation for new life.

By placing written accounts alongside material culture – linens, expenditure on food and drink, infant clothes and birthing stools – which have featured prominently in histories of childbirth previously, we might better see them as part of a larger impulse to embed unborn children within familial contexts and narratives. For some historians, the objects that women were given or gathered prior to birth was a mechanism of temporary seclusion from the domestic unit. For Adrian Wilson and others, these items and the practices associated with them served to literally and figuratively sequester women away from the rest of the (male) household during birth and helped to create a relatively egalitarian space in which class, religious denomination and other markers mattered less than they normally would. The birthing woman occupied a room that had been specially designated for the birth and the month afterwards, called her lying-in. She was surrounded by other women she had invited and the ritualistic, and at times talismanic, items she had chosen for up to a month, and this period was far more of a social and community ritual than a familial one in this argument. Once this month, or lying-in, was up, she went to church to give thanks and was supposedly reabsorbed into the family and its priorities.Footnote 1 Thus, Patricia Crawford described the ceremony of childbirth as the ‘female rite of passage par excellance’. For Linda Pollock, although women did not invariably support one another during pregnancy and labour, birth was a nonetheless wholly female event in which material culture played a central role in creating and solidifying female solidarity.Footnote 2 Things and the reorganisation and demarcation of space have been central to this argument that stresses childbirth and particularly this late stage of pregnancy was a unique and subversive time in the gender order of households. This chapter finds quite the opposite. The preparations in the later stages of childbirth did not sequester women away from family and the household. They served to make childbirth a family affair and in keeping with the argument of this book, although women took on the bulk of work in generation, they did so in ways that was set out and circumscribed by male priorities. Although husbands, brothers, fathers and uncles may not have been literally present in the room when birth occurred, the items that they had carefully selected and procured were, and they were only metres away in practical and culturally significant ways.

Growing Big

Early modern correspondence is awash with reflections on pregnant women’s ‘big bellies’, and they were celebrated in the same way that announcements and reckonings were. This was chiefly because the bigger the belly, the more likely it seemed that the baby would be large, healthy and potentially male. In writing about pregnant stomachs, families collectively and vocally hoped for positive procreative outcomes, but also simultaneously made the birth of ‘lusty’ infants seem inevitable within narratives about how ascendant the family was. In October 1695, Margaret, Countess of Wemyss, wrote to her pregnant daughter asking if she had ‘grown bige yit’ and if she was nauseous – did she ‘keep’ her ‘meat’. She hoped she would ‘grow stronge’ and ‘be better & better’ with every pregnancy until she had the twenty children she ‘usid to wish for’ when she was a child.Footnote 3 A month later, she wanted to know again ‘if you be grown bige’.Footnote 4 Lord Broghill gleefully told his father-in-law, Richard, in January 1667 that his wife, Mary, was ‘verry bigg’ despite the fact she was not due to deliver until the ‘Latter end of Aprill’. These signs pointed to the impending birth of a ‘Lusty Sonne’.Footnote 5 This was not the first mention of Mary’s belly since getting married. In March 1666, Broghill’s father expressed to Richard that he wanted nothing more than for her to have ‘a great belly’, which he invited Richard to now ‘Come & see’ it.Footnote 6 Frances Sackville’s husband, George Lane, wrote to Lady Frances Cranfield, his mother-in-law, describing how her ‘great Belly’ was ‘very pleaseing’.Footnote 7 Henry, Earl of Bath, passed on the well wishes of John Finch, chief justice, to his wife, Rachel, ‘for you and particularly for your Belly’, meaning her burgeoning bump.Footnote 8

The interest in pregnant bellies at times appears to have been prurient and potentially erotic. Women’s swelling bellies were a visually interesting representation of male virility and sexuality. They were looked at in ways that confuse relief with the healthy progression of pregnancy with desire. If we recall how the husband in The Ten Pleasures of Marriage gleefully recorded his wife’s pregnancy in his almanac, he now focused his attentions on the sight of her apron, which ‘day from day rose’. Now, ‘all the World may plainly see you have behaved your self like a man, and every one acknowledge that you are both good for the sport’.Footnote 9 The wife in the parody suddenly becomes more affectionate, potentially even libidinous in response to the sight of her burgeoning stomach as a visual representation of her husband’s virility. She ‘imbraces and kisses’ her husband because he had ‘furnish’d her shop so well’. The author impresses upon the reader that ‘the procreating of children, makes the band of wedlock much stronger, and increaseth the affections’, but we see that there was a prevailing cultural idea in these jokes that women’s pregnant bodies would display men’s sexual skill and the couple’s ascendancy.Footnote 10 This was a common metaphor in cheap print of the period: that the furnishing of women with their baby bumps was similar to the way husbands furnished wives with clothes, linens, food, medicine, shelter and other domestic items. Pregnant women were like ships, the anonymous author of Fifteen Real Comforts of Matrimony jested, and they ‘never looks so handsome’ as when they were ‘completely rigg’d and trimm’d’ with a pregnant stomach.Footnote 11 Conversely for some, the sight of a burgeoning belly in others could provoke shame and sadness. When Samuel Pepys saw his sister ‘fat gone’ in her pregnancy in May 1669, he noted in his diary that ‘I know not whether it did more trouble or please me, having no great care for my friends to have children; though I love other peopl’s.’Footnote 12 The joy he felt for his sister and her husband, John Jackson, was tempered by his own childlessness. Big bellies were potent social symbols for men and women, for they tangibly and visibly reflected what prior to this point families had only wished for or imagined in their correspondence.

Elite women often sought to display and highlight their changing parturient forms, so much so that Mary of Modena, wife of James II, was suspected to have fashioned a fake belly to pretend she was pregnant in 1688.Footnote 13 Mary Tudor wore a stomacher that emphasised her ‘belly laid out, that all men might see she was with child’.Footnote 14 Some elite women bought new stomachers with matching sleeves, soft stays or had their existing stays altered to include side lace-up panels during pregnancy.Footnote 15 Honor Grenville, Viscountess Lisle, an aristocratic Cornish woman whose life in the sixteenth century is exceptionally well-recorded in the Lisle papers, was offered a stomacher cloth of gold by William Lock, a mercer, in 1536, when he found out she was pregnant. Jane Seymour, Henry VIII’s third wife, was ‘open-laced with stomacher’ when she was pregnant.Footnote 16 Such garments did not hide parturient bodies but drew attention to them.Footnote 17 Pepys described Catherine of Braganza, then queen of England, wearing a ‘white pinner and apern [apron], like a woman with child’, a suggestion that wearing aprons and pinners (pinafores) had become a kind of maternity dress in themselves, albeit one potentially more often of convenience rather than fashion.Footnote 18

For other women, buying new clothes to accommodate their changing shape was financially impossible. In the ballad The Lass of Lyn’s sorrowful Lamentation for the loss of her Maidenhead c. 1657–1696, the young woman who got pregnant out of wedlock fretted that ‘My Petticoats which I wore,/and likewise my Aprons too,/Alas! they are all too short before,/I cannot tell what to do.’Footnote 19 It was not just the prohibitive expense of buying new clothes to accommodate her pregnant form but the fact that she had conceived out of wedlock that the lass of Lynn sought to conceal. Even wealthy women like Sarah Churchill, duchess of Marlborough (1660–1744), might make do by adapting existing clothing. She reflected in a letter to her granddaughter, Diana, that three months before her ‘reckoning’, she could not ‘endure to wear any bodice at all, but wore a warm waistcoat wrapped about me like a man’s and tied my petticoats on top of it. And from that time never went abroad but with a long black scarf to hide me, I was so prodigeous big.’Footnote 20 One might say even writing this was a form of displaying her pregnant form in lieu of clothes. It was not until the nineteenth century that specific pregnancy corsets and dresses were manufactured.Footnote 21 Bellies and the way they were noticed, written about, clothed and, as we shall see, depicted, were part of a system of signs of bodily, financial, religious and social fortune, which men were equally if not more invested in than women. Whilst this symbolism is not so obvious to us now, it was seemingly immediately apparent to early modern individuals, so much that it appears in a wealth of different kinds of printed and manuscript material.

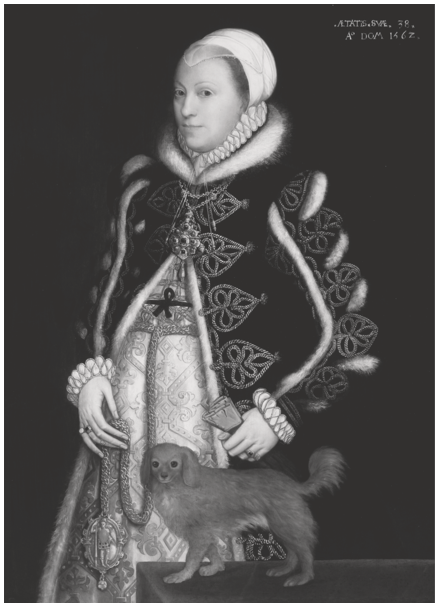

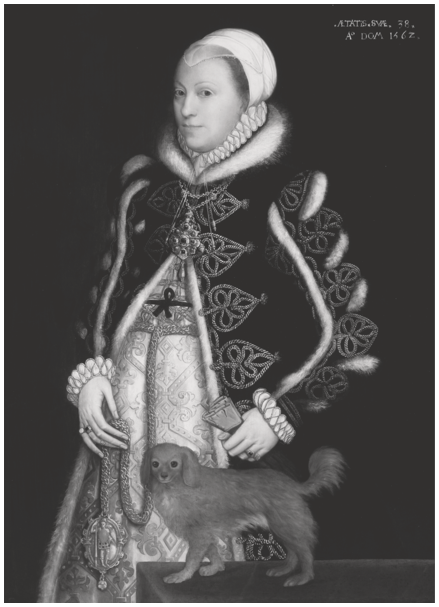

Pregnant stomachs were also celebrated in portraits of aristocratic women in the sixteenth century. Catherine Carey’s (Lady Knollys’) large belly protrudes from beneath her dress in her picture (Figure 3.1). She carries a gold girdle chain and large oval tablet representing the god Mars, armed with a spear and shield, gesturing to the Greek proverb ‘Be prepared’.Footnote 22 Her dog stares unflinchingly out of the portrait, a symbol of marital fidelity.Footnote 23 Karen Hearn has described how works like this and others by the Dutch painter, Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, of English aristocratic women acted as a ‘form of visual evidence of anticipated dynastic success’.Footnote 24 ‘Pregnancy portraits’ such as that of Lady Knollys (1562), Portrait of an Unknown Lady, c. 1595 (Tate T07699) and Portrait of a Woman in Red, 1620 (T03456), the latter, believed to be a member of the Constable family, repeated the bigness and fecundity of these women’s ‘bellies’ in a similar way as correspondence.Footnote 25 The women painted in this way were in their late thirties, already having borne several children, and carrying their last or penultimate child. The portraits were not celebrations of youthful fertility but rather of continuity, obvious ascendancy and the permanence of these families. The portrait of Mildred Coke, Lady Burghley, painted in c. 1563, highlights rather than disguises her maturity. Hearn suggests that cultural anxieties about succession and the queen’s waning fertility provoked families to commission these tangible reflections of maternal travail for the family and its title.Footnote 26 Although there was a little boom in these portraits in the late sixteenth century, generally it is very difficult to find obviously parturient bodies in European art of the period because this was supposedly deemed unseemly or vulgar.Footnote 27

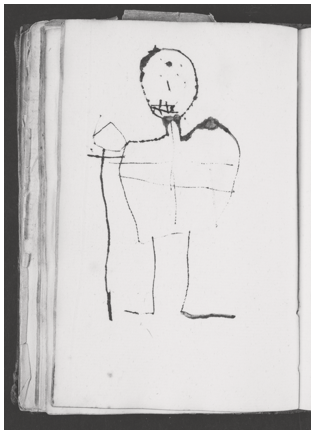

The medical and culinary recipe book of an anonymous early eighteenth-century English or Scottish family suggests that obviously pregnant bodies could also be a source of fascination and celebration in very domestic contexts too. The book contains numerous remedies relevant to generation such as ‘A Very good Receipt against miscaringe’, ‘A present Remidie for a Woeman with childe, wch hath taken hurt by a fall or fright or any Mischanc to staye the Child and to Comfort it’ and ‘For the falling doune of the Matrix after Child birth’.Footnote 28 It includes a series of naïve images, perhaps the work of a child, drawing his or her family members. First there is what we might gather is a male figure carrying maybe a riding crop, spade or rod for disciplining children and servants (Figure 3.2a). Then there is what appears to be a female figure – she wearing a dress (Figure 3.2b). The next page possibly depicts a baby. The figure is substantially smaller than the others and its dress is distinctively cross-hatched, a possible representation of swaddling bands (Figure 3.2c). On the next page, the drawer has made another figure with a big, distended, possibly pregnant, belly (Figure 3.d). On the following page, using the bleed-through, this belly becomes breasts, with a bigger, rounder belly drawn in below (Figure 3.2e). The identity of the drawer and their intentions are irrecoverable, and yet the prominence of big bellies within a book that is primarily concerned with domestic wellbeing and order points to the ways these concerns overlapped within households. Perhaps more than their composition, it is that they have been kept and not erased or removed that reveal the meaning behind visibly pregnant bodies in the construction of family identity in the period.

In court settings, calling a woman ‘big’ and drawing attention to the size of their pregnant stomach was often used to signify how close a woman was to delivery, as well as their performance of godly maternity. It was used to stress pregnant women’s vulnerability and their need for social and legal protection. Crimes committed against pregnant women were deemed more barbaric and ungodly, especially so at this later stage of parturiency. Describing women as ‘big’ emphasised not only their bodily infirmity but also the maturity of the babies they carried; these infants were just on the cusp of outside life and therefore to rid them of the possibility of it was more morally reprehensible. Big bellies recurred as a trope in sensationalist murder pamphlets to emphasise the depravity of criminals. In A True and Perfect Relation of A Horrible Murther (c. 1678–1680), an unnamed man brutally murdered his ‘neighbour’ who is ‘full bigg with Child’. The child was delivered after its mother died and lived on to avenge the death.Footnote 29 The wife of David Williams was ‘most big with child to bee’ when she was cruelly murdered by three soldiers.Footnote 30 In assault cases, Jenine Hurl argues victims drew attention to their pregnant states where relevant to ‘increase their appearance of vulnerability before the court and command its sympathy’.Footnote 31 In France, the penalty for assaulting a pregnant woman was adapted in accordance with how close she was to delivery – if the child had quickened, the perpetrator was executed, if not, a fine was levied.Footnote 32 Being pregnant excused women from execution across Europe in this period. Women who ‘plead the belly’ were interrogated and inspected by a jury of matrons to attest to whether they were telling the truth.Footnote 33 Pamphlets similarly played on the idea that seeing a pregnant belly elicited sympathy and the desire to protect. The sight of a ‘bigge belly’ of a ‘handsome, and decently apparelled’ ‘wandring yong woman’ in one ballad provoked such pity in Mother Watts that she offered her a room for the night, ‘sucker [succour], helpe and furtherance … at the painefull hower of her deliuerie’. The woman delivered a monstrous and misshapen child that night, but her vulnerable appearance had convinced Mother Watts to take her in despite her better judgement.Footnote 34

Although being big was often celebrated, for pregnant women themselves, particularly unmarried ones, the word could also be used to signify a stage of pregnancy that was cumbersome and difficult. Female writers, therefore, often used the term to describe the moment when their pregnant state made life uncomfortable, when delivery was imminent and their child had reached a certain level of maturity. Frances Hutton, in a letter to her husband Christopher, relayed how ‘Mrs Allen’, possibly a midwife or nurse, thought she was carrying a ‘very great child’ because of her size. Hutton wondered whether she night be carrying twins, ‘I am so exceeding big’. Her size and recurring pains meant she could no longer walk.Footnote 35 In this exchange, being ‘big’ conveyed how much the infant had grown, how imminent delivery would be and how taxing bearing children could be. The next day, Francis was still struggling; she was in ‘Every hour in expectation of my labour’ and her condition tied her to her bed and ‘chamber above this three weeks. Mrs Allen will not let me stir out of it I am so extreme big.’Footnote 36 Alice Thornton similarly gestured to her size to emphasise that she was ready to give birth. In her second pregnancy, a month before she assumed she would give birth, she grew ‘bigge’ and ‘was in a wearish condition’. When pregnant with her third child, ‘a week before my full time’, she was ‘in much paine through the heavinesse of my Childe; haveing the midwife in constant expectation each houre’, exacerbated by her mother’s absence. Again, in her fourth pregnancy, she was ‘heavy, bigge, & weary’ and ‘Full of paine; & the labour each day’.Footnote 37 At other times, bigness was used by others to gesture to how imminent delivery was. Thomas Busbridge in a 1682 letter to his sister, Anna Farnden, described his wife’s struggles to get home to give birth – she was ‘big with child’, the roads tricky and ‘not well in a coach’.Footnote 38 In 1645, Isabella Twysden recorded in her almanac that she had ridden on horseback to Peckham ‘great with child’ and was grateful to ‘land no hurt’.Footnote 39 Lady L’Estrange was ‘very well & is as bigg as if she were near Lying downe’ or going into labour, ‘& so I suppose she is’.Footnote 40 Penelope Mordaunt appealed to her husband to return home from Walton and Bedford because she ‘begin to groe big’, ‘biger and heavear’ than with any of her previous children.Footnote 41

Although being big was something that was celebrated when women conceived within wedlock, for unmarried women, this was often the moment when their bodies began to betray their indiscretions. Single women were surveyed by neighbours, and when they were suspected of having pre-marital sex and being pregnant, their stomachs and breasts were watched for signs of conception.Footnote 42 The neighbours of Gertrude Law of Rotherham thought she might be pregnant in 1671 when she got big and then ‘suddenly grown less in her body’. A man said ‘thou was with child but thou art swampe [flat] now’.Footnote 43 Five months later, the body of a baby was discovered in a well on her street, cementing their suspicions that she had had a child out of wedlock. When women were accused of having illegitimate children and committing infanticide, they often claimed that their big stomachs were caused by something other than being pregnant. Showing they were unaware of their pregnancies, or that their stomachs were swelling because they were unwell or had eaten too much, could save them from being hanged. These claims might allow them to circumvent the part of the 1624 law that held them automatically responsible for the baby’s death if they had not shared their pregnancy with anyone: how could they tell anyone they were pregnant if they did not know they were? Isabel Barton, who was suspected of infanticide in Yorkshire in 1663, told the court she had been ‘ravished’ by a man in June and that her body ‘grew big’ but she had no idea she was with child until she miscarried in December.Footnote 44 In these court cases, the size of women’s bellies was used as evidence that either incriminated them or helped to exonerate them, and supports the suggestion by historians that the term being or growing ‘big’ had contemporary parlance as signifying a stage when pregnancy was visually verifiable.Footnote 45 For elite married women, however, this was an act of display more than a fraught process of visual verification. Big bellies helped families furnish accounts of what the unborn child would be like. Noticing, depicting and writing about big stomachs was part of this same attentive culture of record-keeping and sought to impose order and a sense of processual predictability to pregnancy. That bellies could swell for all kinds of other purposes was often left out of elite correspondence and instead celebrated as being a portent of positive procreative outcomes to come.

The ‘Litle One Within’

Pregnant bellies were important to families primarily because they suggested that the child was alive and well within, and helped to imagine it as part of the household already. When William Chaytor sent a letter to his pregnant wife, Peregrina, in 1691, he offered well wishes to her as well as ‘the litle one within’.Footnote 46 Interpreting the signs and symptoms of pregnancy to engage in these imaginative and speculative ventures was one of the ways families imposed certainty on the process of childbearing. It also made the unborn child part of the family before its birth. This kind of specificity was similar to the ways in which women and families proffered particular dates when they thought they might give birth or their reckoning that we have heard about in Chapter 2.

Family members were particularly interested to know whether the baby was a boy or girl. When Lord Broghill wrote to his father-in-law to announce that his wife had quickened, he noted ‘they tell me by all signes yt will bee a Boy’.Footnote 47 When Grace Wallington gave birth, her husband, Nehemiah, recorded in his diary that when she had a ‘man child’, they were surprised because this was ‘contrary to our expectation.Footnote 48 Jane, wife of Ralph Josselin, claimed that one of her births was ‘very strange to her’ because it was a daughter, ‘contrary to all her former experience and thought’.Footnote 49 Isabella Wentworth wrote to her son, Thomas, to ask him to buy lace to make a ‘cressning [christening] suit’ fit to dress a boy but expressed her suspicions that his wife was carrying a girl.Footnote 50 Thomas only agreed to pay an exorbitant fee for a man-midwife (100 guinneys) because he was convinced it would be a boy. He was ultimately disappointed when Isabella’s hunch proved right. The astrologer-physicians, Richard Napier and Simon Forman, were often asked to determine whether women were carrying a boy or a girl. Mary Robinson asked Forman in 1599 whether she would have a boy or girl.Footnote 51 Likewise, Elizabeth Scarlet who was ‘neere upon her tyme’ asked when she would give birth and whether it would be male or female.Footnote 52 This was at times motivated by anxieties about procuring an heir. Vere Bouth asked whether she ‘shall have an hayre’, having previously had a little girl that died.Footnote 53 Sir Thomas Middleton asked whether he would have a son.Footnote 54 Lady Elizabeth Dacre also asked whether she would have a boy, suggesting she was concerned with primogeniture.Footnote 55

It seems that parents were not making these guesses randomly, but they might have drawn on extensive guidance in childbearing guides about how to read bodily signs to discover the sex of unborn babies. Carrying a girl was described as much more taxing on maternal health than carrying a boy, and therefore women who felt weak and sick during their pregnancies were assumed to be having a ‘wench’. Jane Sharp explained that ‘If it be a boy she is better coloured’ and she would be ‘more cheerful and in better health, her pains are not so often nor so great’.Footnote 56 Jacques Guillemeau suggested that women who were pregnant with girls would be ‘wayward, fretfull, and sad’ due to the excess of moisture produced by female children.Footnote 57 Girls were bred on the left side of the womb, where it was colder and moister, and boys on the right, where it was hot and dry. This supposedly led to bodily asymmetry that could be read to discover the sex of unborn children. If movement was felt only on one side of the womb; if one breast ‘rise and swell beyond’ the other;Footnote 58 this would reveal the sex of the baby.Footnote 59 Thomas Chamberlayne and Jane Sharp recommended observing how a pregnant woman moved. If she put her right foot forwards, ‘and in rising she eases all she can her right side sooner than her left’, she was carrying a boy.Footnote 60 Even the milk that came into a woman’s breasts in the latter months or weeks of pregnancy might reveal the sex. Sharp suggested women expressed a drop into a basin of water – ‘if it swim on the top it is a Boy, if it sink in round drops judge the contrary’.Footnote 61

These findings challenge the prevailing idea that children remained largely ungendered until they reached a certain level of maturity. In particular, historians of medicine have noted that unlike the ways sex and gender conditioned the diagnosis and treatment of adult bodies, for children, sex made little difference in terms of diagnosis and treatment of disease.Footnote 62 Hannah Newton argues that sex was not ‘as significant as other variables’ in understanding children’s bodies and their medical needs,Footnote 63 nor was it important in informing medical treatment.Footnote 64 It was only when children reached a certain age that gender was imposed upon them, chiefly through dress and the practice of breeching when boys were around six.Footnote 65 Yet, the interest in working out whether babies were boys or girls when it seemed they might not live long, and the ways in which people sought to assign sex to infants when this was not immediately apparent, points to a pressure to classify newborns as decidedly male or female within families, as well as a belief that male and female babies must be humorally distinct enough to have a different impact in gestation on the maternal body. Goody Marshall’s child was ‘Christnd for a wench’ in 1624, despite being described by Richard Napier as a ‘hermaphrodite’ and living only a week.Footnote 66 Scientific, alchemical and philosophical works were keenly interested in intersex individuals or ‘hermaphrodites’.Footnote 67 This interest was often as much prurient as it was intellectual and served to sustain sexual and gender boundaries.Footnote 68 In medical texts, physicians adjudicated whether their patients would live their lives as men or women, a decision that was enforced by authorities.Footnote 69 Family members, medical practitioners and pregnant women engaged in an important and symbolic cultural ritual in imagining infants in which their sex was central. Although treatment for infants may not have diverged significantly for boys and girls, their bodies were already thought to be humorally male or female, which would have different impacts on their mothers during pregnancy, in ways that confirm the work of other scholars who have suggested that gender and sex were important categories of difference over the medieval and early modern period.Footnote 70

In addition to working out the sex of babies before they were born, some parents named their children prior to delivery. This practice perhaps more than any others strongly suggests the desire to knit infant lives into larger familial narratives. Robert Woodford, a Northamptonshire lawyer, relayed in his diary how on the day of his son’s baptism, he forgot to instruct the chosen godparents that the ‘name should be John’. Godparents were in charge of holding and naming infants at baptism ceremonies in early modern England, usually in consultation with parents.Footnote 71 This practice was common enough that Alice Kenyon’s mother, Jane, joked with her that she should find ‘convenient godmothers’ who would promise to call her daughter ‘Anne or Alice’ and definitely not Jane.Footnote 72 One of baby Woodford’s godparents, Mr Readinge, in a flash of divine inspiration. judged the child to be called John. This was not an uncommon narrative for godparents to name children from divine inspiration. Elias Ashmole was named because his godfather, Thomas Ottely, had an epiphany to cease the family tradition of naming boys after their fathers. However, where the Woodford narrative departs is that Robert noted that not only was John the name he had hoped for, but it was ‘the name by which I and my wife used to call it before it was born’.Footnote 73 Another touching glimpse into this practice can be found in a letter from Eliza Cope, of the Dorset Sackville family, who told her sister that for the entire pregnancy and the two weeks since she had given birth she and her husband had been calling their son ‘little Cakebread’. He would have a new more formal name at his christening.Footnote 74

How the baby moved within the womb might also reveal things about its future character. Wemyss asked her daughter how her little ‘devil sturred’.Footnote 75 Thornton compared the ways that her different children felt in the womb. Her fourth child, Katherine, was ‘more weighty & not so nimble as naly & betty’. Katherine was ‘very liuely’ in the womb, which made Alice ‘uery feauorish & hot, causing much sicknesse’. Sometimes such sensations were used to direct medical care. Alice had her blood let and described how the baby ‘sprange in my wombe’. She was healthier and stronger from this point onwards.Footnote 76 These efforts to understand and visualise the infant imbued the infant with an identity – a sex, personality and even name – in a collaborative process with other family members. Many of these exchanges insisted on the specificity of the experience of pregnancy to the mother and the child. When Althea Talbot, Countess of Arundel, was pregnant in 1608, her mother-in-law noted to her father, Gilbert, that ‘all children were not bred alik[e]’.Footnote 77 It was comforting for families to imagine that their infant’s personality was already fully formed and imagine the ways that it might resemble its ancestors.

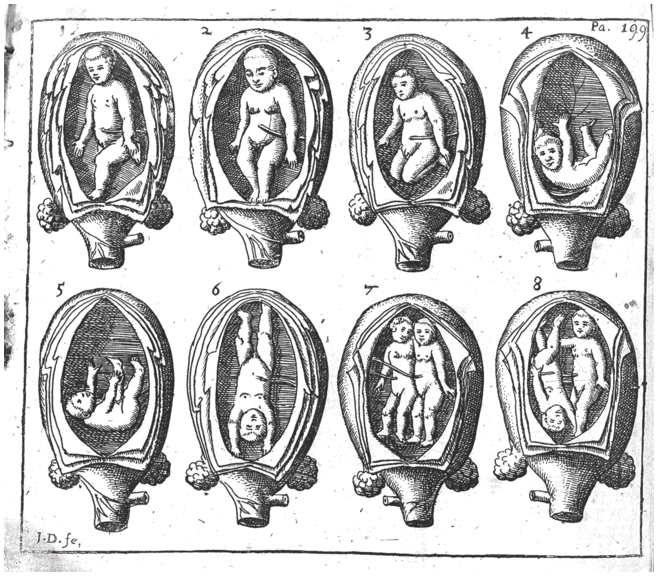

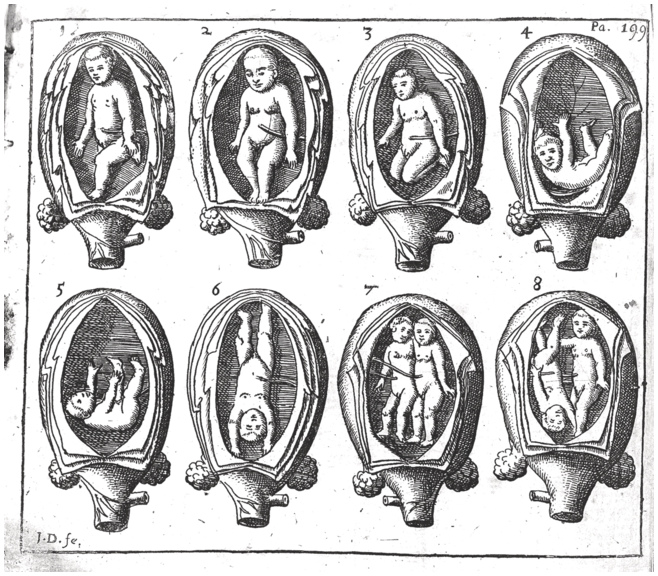

In imagining their unborn babies, early modern English families had a long-standing visual code from which to borrow from – the representations of infants in the womb in printed medical texts. These were useful in two ways. They not only allowed people to understand the basic physiological process of pregnancy, but they depicted babies that would have been comforting to individuals anxiously waiting for the birth of a new family member: these babies all appeared large, lusty and very much cognisant of their surroundings. These sixteenth- and seventeenth-century images bore many similarities to the highly stylised older tradition of babies in Muscio’s Latin treatise from the ninth century that appeared to be suspended in flasks or jars.Footnote 78 Unborn infants were almost always represented as male and they were often pudgy or muscular. This trend remained ‘remarkably constant’ from the medieval period to the eighteenth century.Footnote 79 In Sharp’s Midwives Book, the infants swim in luxurious space, and appear in a variety of lively positions (Figure 3.3). They are large and lusty – they have hair on their heads, their eyes are open and they stare out at the viewer with various facial expressions. Whereas older images depicted the womb as a single membrane, by the seventeenth century, authors and artists were interested in the layers of the womb and in depicting the stones, or female testicles. In these pictures, the womb is represented in isolation as if cut out and separated from the maternal body. Karen Newman and Eve Keller have argued this absence was an act of artistic and intellectual exclusion of maternal effort.Footnote 80 Both suggest that this was part of a deliberate effort by early modern male obstetrical authors to deny, ignore and minimise the action of women’s bodies in generation. These visual changes supposedly signified and enacted a transformation in ideas of personhood too – male authors and infants were imbued with agency, while female generative knowledge and work was undermined. These images made an unborn ‘person … from the first moment of his conception’.Footnote 81

Figure 3.3 Jane Sharp, The Midwives Book Or the Whole Art of Midwifry Discovered. Directing childbearing women how to behave themselves (London: 1671), 199.

Figure 3.3Long description

The illustration presents eight different positions of a fetus in a womb. They are numbered from 1 to 8, where the uterus is in an oval sac-like structure. The fetus' positions are as follows. 1. Standing straight with one leg forward in breech position. 2. Straight with slightly bent knees in breech position. 3. Kneeling in breech position. 4. Lying on its stomach in transverse position. 5. Lying on back in transverse position. 6. Upside down. 7. Twins standing straight in breech position. 8. Twins. One stands in breech position, and another upside down.

Rebecca Whiteley has called for such obstetrical images to be redefined as ‘birth figures’, stressing their discursive purposes as tools of understanding birth positions. She proposes that such images could perform several simultaneous but diverse functions for different audiences. First, images of the unborn in childbearing manuals provided midwives with practical information about how to ensure infants were delivered safely. Secondly, learned readers were engaging in philosophical questions about the nature of creation and the universe. Finally, she suggests that for labouring women, their friends and family, images in midwifery manuals visualised the infant as large and lusty, not ‘fragile, scrawny neonates’ – and that this, rather than an effort to erase the maternal body, led to their highly stylised appearance.Footnote 82 Whiteley suggests that in the same way pregnant or labouring women might avoid troubling or disturbing images that could damage infant health and would instead gaze on pleasing objects and pictures to improve infant health, the babies in bottles in childbearing manuals were a tool in securing positive medical outcomes.Footnote 83 These images presented a hopeful and reassuring visualisation of pregnancy – they focused on the outcome: a baby, just as correspondents did in their letters imagining the size, sex, name and personality of the new family member.

These signs had meaning to early modern families perhaps because of the ways that authors equated the movement of foetuses with maturity and viability. James Wolveridge explained that forty-five days after conception, the infant was ‘divinely infused’ with a soul and therefore ‘receiveth life’ and was ‘no longer called a young one, but an infant’. Robert Barret, borrowing from Hippocrates, similarly suggested an infant was ‘formed’ by day forty-five and this could be doubled to work out quickening and tripled to work out the day in which the infant ‘will make haste to the Birth’.Footnote 84 Jakob Rüff described how after quickening the infant sought to widen his ‘narrow little Cottage’ by moving, and it was this that helped to swell pregnant stomachs. When they could no longer be contained they ‘moved with great force and violence in the womb’ to be born.Footnote 85 Sharp described the ‘violent motion of the child’ that forced the waters to break and that the infant ‘can no longer stay there than a naked man in a heap of snow’.Footnote 86 Medical writers assumed that infants had a certain awareness and that from when they began to move, their character and bodies were largely formed.

In this context, it makes sense why family members were particularly interested in how unborn children moved and also why big babies were thought to be particularly healthy infants. We might say that this process of understanding the infant body through reading a patchwork of signs is similar to the one that Olivia Weisser describes early modern people doing for other kinds of illness including boils, pustules and wheals on bodies.Footnote 87 Richelle Munkhoff describes the ways plague searchers engaged in ‘acts of interpretation’ when they looked at dead and alive bodies for signs of the plague.Footnote 88 Family members interpreted a mess of bodily, religious and social signs to create an identity for the baby before it was born and were careful to write these predictions in a variety of different kinds of paperwork. This culture of investing in and imagining the future life of the babies from elite families intensified with the process of gifting, borrowing and gathering things for the new child. These items, like the accounts written about babies and their mother’s big bellies, formed part of a familial ritual of display that was largely inaccessible to unmarried and vulnerable women.

Some Things to Be Had

As well as imagining what the baby would look like, these months of pregnancy, when families were sure a child was on its way, were dominated by the process of buying and gathering things for delivery such as bed linen, clouts, cloths for swaddling the newborn, cradles and sometimes birthing stools and negotiating these gifts, loans and purchases. Food and alcohol were needed to feed and entertain the women who attended the birth, the men sitting anxiously waiting downstairs and for both the baptism and churching ceremonies. Indeed, gifting women with things to prepare for birth was so ubiquitous it was inscribed in the title of John Oliver’s 1688 popular text for childbearing women – A present to be given to teeming women, by their husbands or friends Containing Scripture. Footnote 89 In 1697, a heavily pregnant Peregrina Chaytor wrote to her husband requesting twenty pounds and ‘to bring me down and buy som things which must be had’ for her impending delivery.Footnote 90 Peregrina was in temporary lodgings in London, while her husband was at their home in Croft, North Yorkshire. She asked for:

| 3 paire of good sheets 2 paire of such as the boyes lye in 5 pair of pillobear [pillowcase] 3 towells the rest of the huggaback napkins to what are at London the broad Diaper Napkins and table cloath one duzen and half of the course huggaback napkins 2 table claoth of huggaback or linen the [destroyed] huggaback table cloath Holland in her trunk [destroyed] to make sleeues either here or be sent up some more holland left their and any old linen of hers or mine for night close for the child half a dozen of De mask napkins and table cloath The dressing glasse and boxe The silk mantles and quilt 4 silver spoons and forks | 2 silver salts 1 silver podinger the cup wth the cover or tankerd bacon hams and tongue and cheses salt butter a firkin of salt butter [destroyed] bushels of wheat flour Aile [ale] 3 litle pillows laced pillowbeers one or two dimothy pillows w[hi]ch came from Richmond |

Although most early modern family paperwork was not quite as detailed in their record-keeping of the materials gathered for birth, Peregrina’s letters to her husband point to the variation of expensive, cheap, repurposed and borrowed items that were key to this practice. Peregrina sought to gather pricy items like the silver porringer (a shallow silver dish often given for christenings), some cheaper items (like flour) and others repurposed (like the holland linen in her trunk). Some things, which Peregrina hints at in her request for ‘linnen of hers or mine for night close for the child’, were borrowed or gifted by other family members. Perhaps most notably of all, Peregrina negotiated with her husband the gathering of these materials rather than approaching her female friends. Janelle Day Jenstadt explains that childbearing furnishings appear in account books less often than other domestic goods because they were often borrowed and returned rather than purchased. Added to this, childbearing items did not often appear in probate inventories because they had other uses and because constant use rendered the linen used for birth substantially less valuable.Footnote 91 This was not because aristocratic families could not afford a set of their own, although in the 1690s the Chaytors perceived themselves to be in dire financial stakes, but a careful and deliberate practice of exchange helped to solidify friendships and alliances between families.

Some of these exchanges and negotiations must have happened orally and so the extent of this material culture of exchange is irretrievable from family paperwork. When individuals did write to either request or offer items in the lead up to a birth, these written accounts served as yet another material stamp of investment and involvement of the family in its perpetuation by young and fertile members and sat alongside almanacs, letters and diaries that attested to women’s godly conduct through pregnancy and occasionally portraits. Anne Holles wrote to her ‘good friend’ Mrs Marris, requesting the return of a ‘mydwyves Chaire’ in 1632. Presumably this was not enough to identify the object, for Anne continued, describing it as a ‘dutch Chaire all of wood, and when it came downe was not sett together, but one side of it layd cloce [close] to the other, and soe packed up in Canvas’. With it, she asked for the return of two wooden boxes, possibly storage boxes for childbed linen.Footnote 92 This was possibly one of several chairs Marris had received or accumulated. Importantly, the chair and boxes were not Anne’s originally but her ‘daughter haughtons’ or ‘her mothers’ – she could not remember which.Footnote 93 She needed them close because she expected that ‘my daughter may have use of it ere long’.Footnote 94 Jane Cavendish kept ‘A note of my childbed linen’ in her commonplace book consisting of seven sheets, 120 double cloths, swaddling clothes for the newborn along with ‘26 pillowberes [pillowcases] course & fine, 1 torn for rags. These are in the childbed linen trunk.’Footnote 95 The fact that Cavendish used torn pillowcases to make ‘rags’ hints at the ways less wealthy women might have dealt with the mess of delivery, staunch bleeding after birth and fashion nappies.Footnote 96 Linen and bedsheets were, as Sasha Handley has shown, particularly emotive and affective objects within early modern households and often kept for their meaning across generations.Footnote 97 Sarah Fox notes that this culture of borrowing (which in the eighteenth century became institutionalised when poorer mothers could apply to charities to receive bundles of linens) was a flexible and adaptive practice that survived well into the eighteenth century.Footnote 98

Lady Lisle obtained an extensive list of items of clothing and bedding for her and her unborn child between 1536 and 1537, all negotiated by her chief servant, John Husee.Footnote 99 These items were not always borrowed because the family were unable to afford to buy their own but the material letter detailing a loan and the objects themselves ‘cemented social and political relationships’.Footnote 100 Sometimes, however, women wrote expressing real need for objects that they could not afford or find themselves. In 1590, Elizabeth Molyns was worried about her heavily pregnant daughter and wrote to Cicely, Lady Buckhurst, Countess of Dorset, hoping she would be ‘allow & p[ro]vyde for her that ys mete for a woman in her case’. Molyns’ son-in-law had commited ‘wronges vexations & Inspeakable Inyuryes’ through his ‘crueltie & wyckednes’ to her daughter, chiefly by denying her items needed for her impending delivery. Molyns asked Buckhurst to find her daughter some ‘honest matrons’ to accompany her in her delivery ‘as may be for her saffetie’. It was ‘evident’, she wrote, that her husband ‘hathe no car[e] for the p[r]esvacion of her Lyffe’.Footnote 101 Thomas Peyton wrote telling Henry Oxinden that his daughter was ‘towards lying in’ and that her husband was so uncaring that he paid as much attention as if it was his cow that was calving, rather than his wife giving birth. ‘Shee’, he cautioned, ‘is as unprouided as one that walks ye highwaies’. Peyton lamented that the beginning of the marriage was as ‘unblessed’ as its current ‘incesant troubles’.Footnote 102 This was most likely Margaret Oxinden, who married the wayward John Hobart in August 1649, plunging Henry into lawsuits on his son-in-law’s behalf.Footnote 103 Men were severely judged for not providing for their wives at other times too, but this was particularly reprehensible during pregnancy and birth.

Although these items took on an important emotional and social significance within households, women were very careful to ensure they were only requesting what was ‘mete’ or ‘fitting’ for their deliveries.Footnote 104 Bridget Willoughby, for example, reassured her pregnant daughter Elizabeth in 1611 that she would be ‘readye to supplye you with any thinge that shall be fittinge, as yor occasions shall requueyre’.Footnote 105 Elizabeth Molyns stressed that her daughter only needed what was ‘mete’, nothing more. Obtaining only what was strictly necessary, and never excessive, tapped into a dominant religious cultural discourse in the early modern period of moderation. While this duty to consume food, drink, material goods, sex and company with care was configured in prescriptive texts as important for men and women, plays, satires and even some conduct manuals suggested that it was women alone who often spent too much in the lead up to delivery. The preacher Richard Adams, for example, noted that women should gather simple linens that were ‘fine’, ‘clean’ and ‘white’ and refrain from purchasing ornate, expensive or decorated objects. He chastised women who ‘find you have conceiv’d, and grow pregnant, are highly concern’d to put on, and use these Ornaments’, which they all too readily involved their ‘mates’ in.Footnote 106 This was a culture that local authorities were also keen to regulate. As early as 1540, the Chester Assembly Book expressed concern about the ‘great excess’ of food and drink at childbed gatherings, churchings and christenings.Footnote 107 The material culture of childbirth was consistently represented as being bequeathed to women by their husbands, the Church and state to ease and support their childbearing but it was conditional on their godly and moral conduct.

The stereotype that wives used parturition as an excuse to trick their hard-working husbands out of money to buy frivolities was regularly referenced and satirized in plays and cheap print of the period.Footnote 108 Thomas Middleton’s A Chaste Maid in Cheapside, written in 1613 and published in 1630, parodied the pregnancies of middling sort women who sought to emulate the increasingly lavish lying-ins of elite women. Alan Brissenden has suggested that Middleton was directly mocking the lavish lying-in of the countess of Salisbury, wife of William Cecil, who John Chamberlin reported had her chamber hung with ‘white satin, embroidered with gold (or silver) and perle’ valued at £14,000.Footnote 109 In the play, Mrs Allwit is ridiculed for the excess of ‘embossings,/Embroiderings, spanglings, and I know not what,/As if she lay with all the gaudy shops’.Footnote 110 Allwit equates the toll of spending that men undertook with the emotional and bodily work of breeding a child for women: he tells the audience that it was more often husbands’ backs that broke through their wives spending, rather than wives’ through birthing.Footnote 111

Ten Pleasures of Marriage mocked the first-time mother-to-be who acquired so much stuff that ‘the Child-bed linnen alone, is a thing that would make ones head full of dizziness, it consists of so many sorts of knick knacks; I will not so much as name all the other jinkombobs that are dependances to it.’Footnote 112 Whilst the expectant mother was meant to devote herself to ensuring her body and soul were prepared for delivery, the woman parodied in Ten Pleasures instead turned herself to diligently measuring ‘Beds, Bellibands, Navel clouts, shirts, and all other trincom, trancoms!’ as if ‘she had gone seven years to school to learn casting of an account’.Footnote 113 In such satirical texts, the work of pregnancy is equated with, even outstripped by, the labour and exhaustion husbands endured to buy things for their wives. Within this account, it is not just her excessive spending but also the fact that she does so without her husband’s supervision or other family involvement that makes it reproachable. Husbands in The Bachelers Banquet saw their wives’ bellies growing big although they had been cuckolded and the child was begot ‘by the helpe of some other friend’, but they were foolishly bothered about getting only the best things for their wives’ lying-ins.Footnote 114 The husband had to ‘trot up and down day and night, far and near, to get with great cost that his wife longs for’. When his wife gives birth, he must entertain her friends visiting for half the day, while ‘the poor man’ is ‘handled behind his back’ with salacious gossip.Footnote 115

These pamphlets reveal the subtle but pervasive links between the material culture of childbirth and the legitimacy of conception and the ways in which men perceived themselves as giving their wives things in a way that was dependent on their good conduct. This in turn complemented and sat alongside manuscript accounts of the experience of bearing children in family archives. In the Lass of Lynns, it is only once the midwife has reassured the sceptical father-to-be that the child is his that he grants his wife and her gossips ‘a Barrel of stout Ale,/and send for a Groaning Cake’ to ‘us Merry make’.Footnote 116 His purchasing and celebrating is only mocked by the gossips and audience who know full well that the child is not his. Moderate and abstemious pregnant women were idolised as the ideal. It was not necessarily that women like Peregrina, for example, were really surviving with the bare minimum, but it was advantageous to the family’s pious reputation to be seen to be doing so. Print culture’s intensive focus on women being good mothers meant that some were discarded as ‘lewd and vnnatural women, as leaue their new-borne children vnder stalls’, and others perceived as selfish and ungodly for their immoderate gathering of baby things.Footnote 117

Whereas Peregrina Chaytor might have considered her list a reduction of her normal and expected means, the vast majority of early modern women would not have owned, been able to borrow or purchase this plethora of expensive pieces. One family’s definition of ‘mete’ or ‘fitting’ could be quite different from another’s. Poorer early modern women might have borrowed heavily from family and friends to make up a full set of childbearing linen and would suffice with fewer, plainer and cheaper pieces.Footnote 118 Low-status women might use a straw bed instead of the increasingly fashionable pallet bed, a mattress or bed that was lower to the floor. The straw could be burned after delivery to save on the cost of linen.Footnote 119 Since providing proof of preparation for birth could be crucial evidence in exonerating women from infanticide,Footnote 120 one might expect details of a lower-status lending culture to feature prominently in the court cases of unmarried mothers, this appears to have been an uncommon defence. This may have been because this material culture of childbirth was so firmly bound up with male involvement and legitimate pregnancy to make it seem wholly unnecessary to single mothers proving to courts that they had intended to keep their children. Only two women out of a surviving seventy cases of neonatal infanticide tried at the Northern Circuit Assizes between 1642 and 1680 used this as a defence.Footnote 121 These pregnancies were normally concealed from family, friends, masters, mistresses and fellow servants. Unmarried mothers did not have the immediate support of a husband and family. They were additionally excluded from the emotional and practical support of fellow women. Aiding an unmarried pregnant woman could lead to legal ramifications: one woman was prosecuted for ‘keeping of whores and lewd women in childbed and suffering of men to come in and lie with them before they be churched’.Footnote 122 Another woman tried at the Old Bailey for infanticide in 1691 asked a midwife in Stepney whether she could ‘Lye In in private, which the Midwife promised she should’ if she could provide for the child. Instead, the mother ‘made away with the Child, throwing it into a Puddle of Water on the backside of the House’.Footnote 123 In this way, although many of the rituals and practices of delivery were female-only, they were culturally directed and bestowed upon them by men. The discussions of illegitimate motherhood displays how central the family project was in structuring the experience of bearing children.

Within elite families, the boundary between what was perceived as necessity and decadence was often debated. Isabella Wentworth, who served as lady of the bedchamber to Mary of Modena, for example, was particularly adamant that her daughter-in-law should have only the finest childbed accoutrement. This concern was not an aberration. She took an avid interest in her son’s life, and particularly his marital prospects. Prior to his marriage to Anne Johnson in 1711, Isabella expressed what can only be described as desperation that her son wed and produce an heir. When Anne was pregnant with her first child in 1713, Isabella was similarly heavy-handed in her involvement. Isabella was dismayed that Anne was not interested in the ‘new fation’ for cradles and sumptuous birthing linens. Isabella took it upon herself to find and present Anne with new trends but Anne, Isabella wrote to her son in disappointment, liked ‘her own fancy much better then any elc’. She told Thomas how she ‘durst not’ suggest anything else to Anne other than what she perceived as the bare necessities for birth – she protested ‘thear is nothing of ffancy in them’, and yet Anne still turned up her nose.Footnote 124 When Thomas sent his wife bedding and linen for the baby’s arrival, Isabella told her son that Anne was insufficiently grateful. Isabella, in contrast, was delighted and gushed that he had sent ‘enough for fower or five times Lying in’. She liked the ‘clouts very well’ and a quilt was ‘very handsom’.Footnote 125 The tension between the two women is palpable, with Thomas as the mediator, and crucially the one who gave permission for purchases for both his wife and mother for the impending birth. Isabella told her son in one letter that she doubted Anne even loved her.Footnote 126 By rejecting Isabella’s offers to procure and provide material things, Anne was also rejecting her involvement in the project of multiplying the family.

Indeed, men were often asked explicitly for their permission when women wanted things to prepare for birth. When in Barbados, William Swynsen wrote to his brother John requesting that he bring childbed linen with him for his pregnant wife.Footnote 127 The chief servant of Lady Honor Lisle was responsible for negotiating the purchase and borrowing of items needed for Lady Lisle’s pregnancy and delivery in 1537, and it was he that had to write to donors when the baby was stillborn and never ‘occupiede’ the swaddling clothes that had been obtained.Footnote 128 William Chaytor, if we recall, was in charge of gathering and purchasing ‘some things to be had’ for Peregrina’s birth. Wives updated their husbands on the process of preparing for birth. Penelope Mordaunt wrote to her husband, Sir John Mordaunt, in October 1699 while heavily pregnant that she felt increasingly uneasy ‘now a days as well as nights’, which made her send to a ‘Mrs Barnes for blankets and things for the Child, Lest I should be cate [caught]’, with the suggestion being that he too might work to procure her some necessary items.Footnote 129 Lettice, the wife of Framlingham Gawdy of West Harling, Norfolk, wrote to her father, Sir Robert Knollys, c. 1617, asking him to negotiate with ‘my lady’, possibly her mother-in-law, Ann Framlingham, on his visit to her in Oxfordshire for ‘some clouts’ for her upcoming delivery.Footnote 130 ‘Clouts’, like the aforementioned ‘rags’, were pieces of fabric that were often used for hygiene purposes, explicitly for managing menstruation or for babies’ nappies.Footnote 131 The woman in question had promised Lettice clouts during her first pregnancy but Lettice explained ‘I was so well provided that I thought to reserve them till I had need of them, which is now.’ Her eight children took a toll on her stash of linens. She told her father that she had had ‘so many children that they have worn through all my things and therefore I must try my friends again’. She asked her father to search for ‘some old shirts in a corner for me or some old things’, which presumably she might be able to tear up as clouts, thanked him for his gift of two ‘wrought stools’, which her husband had collected from him. Her final request was for him to send a ‘yellow taffeta quilt’ that she perceived he no longer needed.Footnote 132 Lettice’s exchange with her father shows that male family members were often intimately involved in the process of procuring materials for delivery – both her husband and father were key in acquiring and moving goods, but it also mattered that she would deliver her baby on a stool used by other family members. This also hints that there was a subtle etiquette to these material exchanges – a face-to-face request was politer, and possibly, one from a man was more authoritative.

In turn, men framed the things that women asked for and needed for birth as conditional on the performance of godly maternity and their sexual fidelity. Men engaged with domestic material culture in ways that constituted family relationships,Footnote 133 and childbirth accoutrement and materials were no different. The linens and baby clothes, like other items of dress, mirrored the ways men as heads of household clothed their wives, children and servants to signal their own ‘personal prestige and honour’.Footnote 134 Giving gifts was rarely entirely about need or altruism in early modern England but defined a relationship between the giver and the receiver that was symbolised in the material object.Footnote 135 These items alongside paperwork confirming assiduous and careful conduct of women during pregnancy formed part of a family archive. Men framed their contribution to successful procreative outcomes as procuring and paying for material things, making it difficult to see the period shortly before, during and after delivery as one in which women challenged patriarchal structures and separated themselves from the household and men. In fact, childbirth and the material culture surrounding it reinforced and re-enacted many of the tropes and cultural expectations of the early modern home.

Conclusion

During pregnancy, women and their families were interested in understanding and predicting what the unborn infant would be like. The size of women’s stomachs and their symptoms throughout pregnancy promised to reveal whether the baby would be a boy or a girl, big or small, or lively or dull, and this all helped to impose order and certainty on generation. When women were ‘big’, they were undeniably pregnant, something that was celebrated and displayed when the woman in question was married, and particularly middling or elite. Correspondence, conduct manuals and popular print played on the idea that men furnished, trimmed or rigged their wives with their conceptions, big (pregnant) bellies and then the stuff to deliver safely. But for women themselves, this moment of growing big could be troublesome. For unmarried women, it might betray their condition and lose them their job and livelihood. Even for married women, the later stage of pregnancy might be accompanied by pain and immobility. The material goods that women borrowed and purchased were not just essential but involved in a larger culture of the display of respectability. The stuff of childbearing was represented as being gifted to women but was conditional on the perceived legitimacy of the pregnancy and their good conduct. Paradoxically, although some men were criticised for failing to provide for their wives properly, the anxiety around women’s conduct during pregnancy, what the child would look like and the dates women proffered matched up, reveal how men’s domestic and fiscal honour was carefully intertwined with the performance of women’s bodies, as well as how central childbirth was in defining and cementing familial relationships and identity.