Background

Homelessness is an ongoing problem within societies around the world. It is a source of considerable social and political concern, including in this country (Holohan & Holohan, 2000). Considerable resources are allocated by the state here to alleviate it, or aspirationally, to eliminate homelessness (Dublin Homeless Agency, 2007). The reasons for people becoming homeless are multi-factorial. Causes may include personal socio-economic status, relationship breakdown, release from prison, offending history, alcohol or substance misuse, mental illness, other mental health disorders, a history of being raised in institutional care or other adversity (Fazel et al. 2014). As Holohan & Holohan (2000) have identified, there is a significant literature confirming the association between homelessness and mental disorder, although there is well recognised methodological heterogeneity in the research. However, we have been unable to identify previous surveys, in Ireland or elsewhere, of mental disorder in this specific subset of the homeless population.

Homelessness can be defined in different ways. The ETHOS classification system in European Commission (2014) has been adopted by the European Union. In simple terms, however, homelessness can be viewed as on a spectrum of increasing severity from those who are living in ‘inadequate accommodation’, on to individuals staying with friends or relations (comprising ‘sofa surfers’), on to those in homeless services’ accommodation (provided by statutory and non-statutory agencies) and eventually on to those sleeping rough (sleeping openly on the streets, hidden away in parks or down laneways, in abandoned buildings, etc.).

Sleeping rough, therefore, is generally perceived as the most precarious and disadvantaged form of homelessness and probably gives rise to the greatest level of societal concern. Its causes may include lack of access for an individual to homeless services’ accommodation, his/her fear of staying in a hostel due to previous experience such as aggression from other residents, his/her fear or distaste of open drug-taking in such accommodation, personal mental health issues or because of personal priorities. For many homeless people sleeping rough is an occasional, short-term or seasonal occurrence, before gaining access to homeless accommodation or becoming re-domiciled. However, for a small number of people, sleeping rough is a long-term reality.

In the Republic of Ireland, periodic censuses are undertaken. The Dublin Region Homeless Executive found that on the national census night of April 2011, coordinated by it in Dublin, a total of 2375 people were identified as being homeless there, representing 62% of the total for the Republic of Ireland. Over two separate six monthly counts in winter 2010 and spring 2011, our survey’s timeframe, an average of 65 individuals were identified as sleeping rough with ~8% being female (Dublin Region Homeless Executive, Reference Fazel, Geddes and Kushel2014).

In Dublin, a non-statutory agency, Dublin Simon Community, operated the Rough Sleepers Team (RST). The RST visited homeless people sleeping rough in an effort to provide support and assistance, including linking them with health and social services such as primary care, social welfare and accommodation. The RST was therefore the agency best placed to identify individuals sleeping rough in Dublin. During the course of its work, in early 2011, the RST identified 22 people verified to be sleeping rough for a period of 1 year or more. These individuals were defined by the RST as being ‘entrenched rough sleepers’ (ERS). Therefore, the ERS population represented one-third (22/65, 34%) of the total rough sleeping population in Dublin at that time (two-thirds of the people sleeping rough had done so for less than one continuous year).

Self-evidently, this group of long-term rough sleepers, situated at the extreme end of the homelessness spectrum, merits a robust response from a range of agencies. Clearly also, that should be based on evidence of the nature of the problem, including the contribution or otherwise of mental disorder to it.

Methodology

The authors undertook a cross-sectional survey of mental disorder in the ERS population over 3 months in early 2011. They work in Dublin’s two statutory (Health Service Executive) specialist mental health services for homeless people, ACCES and the Programme for the Homeless (College of Psychiatrists in Ireland, Reference Holohan and Holohan2011). These services are Consultant Psychiatrist-led, multi-disciplinary teams employing an assertive outreach approach. F.H. is a Clinical Nurse Specialist and Community Mental Health Nurse (Programme for the Homeless); K.K. (Programme for the Homeless) and J.F. (ACCES), are Consultant Psychiatrists listed on the Medical Council’s specialist register. Each of the authors has a decade or more experience working in these capacities, specifically in the area of homeless mental health.

During the course of the visits to the locales that the RST had identified as the usual ‘pitch’ for each individual, a clinical mental health assessment was attempted. An ICD 10 (World Health Organisation 1992) diagnosis was formulated based on these assessments. In the case of lone assessment by F.H., a nurse who had 15 years’ experience working with this population in Dublin, the diagnosis was arrived at in discussion with K.K. We therefore believe that diagnoses made would have a high level of validity and reliability, commensurate with the experience of the author clinicians.

The use of more standardised, less naturalistic, diagnostic procedures is rarely feasible in the ERS population. Interviews were conducted by day and night in public places in the city, often with subjects who were suspicious and guarded, unable or unwilling to variable extents to tolerate prolonged assessment, sometimes in the presence of inquisitive passers-by, with the surveyors mindful of the subjects’ right to confidentiality. We therefore believe that there is no other practical, superior alternative to the diagnostic procedures employed in this survey of the Dublin ERS population.

Results

The RST had identified all known members, 22 in total, of the ERS population in Dublin at the time of the survey. The authors visited 17 out of these 22 individuals in the timeframe indicated, either singly or in combination. Two subjects died before they could be assessed within the survey period, one by physical illness and one by drug overdose, we have established. Three other subjects could not be detected within the survey period. One other subject ‘fled’ from a homeless service café on approach by one of the authors. Therefore, face-to-face assessments were carried out with 16 subjects.

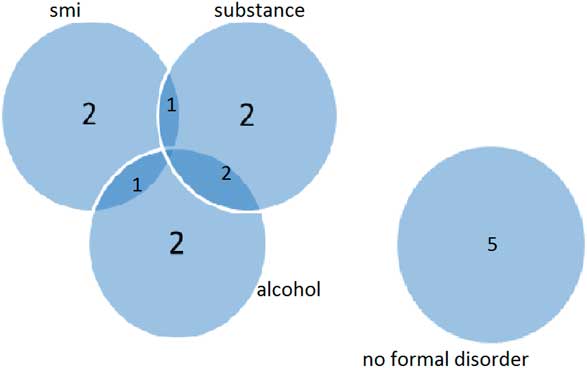

Table 1 sets out the findings regarding the 22 identified ERS. It includes the clinical diagnoses made at the 16 face-to-face assessments. We took the view that we would use only formal syndromal ICD 10 diagnoses in the final analysis (Fig. 1). This is because these findings are likely to have robust reliability. However, we believe readers will also be interested in the less reliable, sub-syndromal or traditional diagnostic constructs that we detected in the group of the 16 assessed subjects. Table 1 also indicates whether subjects were followed up by mental health services, discussed further below.

Fig. 1 Diagnoses. smi, severe mental illness; alcohol, alcohol-related disorder; substance, substance-related disorder.

Table 1 Characteristics of Group

OD, overdose; PH adm, physical healthcare admission; SMI, severe mental illness

We detected only four formal syndromal ICD 10 diagnoses: paranoid schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, alcohol and substance misuse (harmful use and dependence). The combination of severe mental illness (generally taken to mean schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder, bipolar affective disorder and recurrent psychotic depression) and alcohol or substance misuse disorder is often referred to as dual diagnosis.

Mental health follow-up, consisting of subsequent psychiatric review and consideration of necessary interventions were accepted by six subjects. Two subjects with severe mental illness refused to accept the offer of mental health follow-up and did not fit the criteria for consideration under the Mental Health Act 2001 for involuntary detention into hospital. The RST remained involved in all cases as a social care provider and continued to attempt to link these subjects with primary healthcare.

Age

The age range of this identified group was 28–72 years old. The mean age was 45 years old. Half were older and half were younger than 40 years old. There were 11 people aged 25–39 years old (50%), seven people aged 40–64 years old (32%) and four people aged 65 years and over (18%).

Gender

There were three (14%) females and 19 (86%) males in the ERS population.

Mental disorder

Of the 16 individuals assessed, five (31.25%) were diagnosed to have severe mental illness (four with paranoid schizophrenia and one with bipolar affective disorder). Five individuals were dependent on or harmfully using alcohol and five and were dependent on or harmfully using other substances. Two subjects (12.5%) had dual diagnosis. Out of 16, 11 (68.75%) subjects were found to have formal mental disorder, either severe mental illness or alcohol/substance misuse disorder.

We found three of the remaining five subjects had diagnostically ‘softer’ or sub-syndromal difficulties, with evidence for overvalued ideas of religion and dissocial personality traits accompanied by Diogenes syndrome.

Discussion

The survey results demonstrate that there are variable mental health presentations in this population. Age and gender findings were not unexpected as they are in keeping with the homeless and rough sleeping literature.

Nearly one-third of the subjects had severe mental illness (SMI), nearly one-third had alcohol misuse disorder and nearly one-third a substance misuse disorder (see Fig. 1). Two-thirds were identified as having a formal mental disorder of whatever type (SMI or alcohol or substance misuse disorder).

We believe we were able to detect a reasonably large percentage of the ERS group, identified by the most authoritative service (RST) regarding it, despite the difficulties involved. The surveyors are experienced assessors, who used a clinical approach that would be familiar to mental health professionals elsewhere. We therefore believe that formal diagnoses made would have a high level of validity and reliability.

However, we were unable to detect four individuals and two had died before they could be assessed (6 out of 22, 27.2%), even within a survey period of 3 months. Standardised diagnostic procedures cannot be employed with this group, for reasons described above.

Subjects with mental health issues engaged variably with mental health, primary and social care services. It was concluded that none of the 16 assessed individuals were then detainable for treatment under relevant mental health legislation.

Given these results, there is likely to be no standard approach for reducing the challenge of long-term rough sleeping. Instead, case by case, individualised mental health and social care approaches, with collaborative inter-agency working, will be needed. Eradication of this social ill will likely remain challenging for the foreseeable future. There is scope for more research within this minority of long-term rough sleeping population to ascertain the prevalence of mental disorder.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors assert that ethical approval for publication of this study has been provided by their local Ethics Committee.