Introduction

We address a long-running dispute about the historical disappearance of a large Maine coastal mink, Neogale macrodon (Prentiss, Reference Prentiss1903), often referred to as the sea mink. Since its discovery in the early twentieth century, as science has become increasingly concerned with threats to North American wildlife (e.g., Leopold, Reference Leopold1936), many researchers have offered ideas about this recent extinction. The dispute has revolved around whether published archaeological samples include two species of mink, or merely sexual dimorphs of a large variant of the extant Neogale vison (Schreber, Reference Schreber and W. Walther1777).

We shifted focus from skulls to a large number of identified specimens (NISP) of archaeological mink bones (NISP > 1200), comparing them to modern specimens which we evaluated for maturity, sexual dimorphism and diet. Our analysis led us to support the two-species resolution, agreeing with Hardy (Reference Hardy1903, p. 125) that these samples include two sexually dimorphic forms that overlap in size (i.e., N. vison males and N. macrodon females). We conclude that N. macrodon was an emerging marine fissiped, transitioning from an N. vison ancestor, in a way similar to the polar bear (Ursus maritimus) and sea otter (Enhydra lutris).

Historical summary

Bernard Gilpin (Reference Gilpin1867, p. 12) first published a description of very large mink pelts found at Halifax, NS, fur markets:

The largest mink skins measure from the tip of the fore-finger (the arm being extended) to the ear of a man; the smaller to the bend of the arm. The hunters readily allow two kinds.

The largest measured was total length to tip of tail 32½ inches, tail 9½ inches; the smallest measured 23 inches total, tail 6½ inches. These skins may be somewhat stretched, the tails contracted, the colour varies from nearly fawn to brown, brownish black, black, and finally, when in the highest condition of winter pelage, to an indescribable shining bluish black, with a glorious lustre. The lower parts are lighter than the back. The tip of the chin is often white, the throat and between the fore-legs always white, with frequently a white line down the belly. I have seen two or three specimens with white tip to the tail, the smaller species is usually the darker. The feet are half webbed, very large, and have the soles naked. The head is round and truncated, the eyes very near the nose, ear round and short, back high, and hairy tail. The hair much finer and shorter than the martins.

Because these markets dealt in local furs, we regard Gilpin’s (Reference Gilpin1867) report as evidence that the range of N. macrodon extended eastward at least to Nova Scotia.

Prentiss (Reference Prentiss1903) was first to publish archaeological evidence of the large mink based on a partial skull (Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History Cat. No. 115178) that he excavated “on the western shore of Blue Hill Bay” in 1897 (Fig. 1). Prentiss (Reference Prentiss1903, p. 887) named it Lutreola macrodon, placing it in same genus as European mink [Lutreola = Mustela lutreola], stating:

The resemblance of this species to L. [Lutreola] v. [vison] lutreocephalus is very striking, but the difference in size of the teeth, the angle of the nasals and the position of the carnassials justify me, I believe, in the absence of intermediate forms, in describing it as a new species.

Lutreola macrodon is now referred to as Neogale macrodon. Comparative measurements for L. v. lutreocephalus (a historically recognized subspecific form of N. vison) and N. macrodon are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Coastal Maine location map showing Penobscot Bay and Blue Hill Bay, with sites used in this analysis, along with historically noted places where sea mink were trapped historically or recovered archaeologically.

Table 1. Historic measurements for Neogle macrodon and *Lutra v. lutreocephalis [Neogale vison] noted by Prentiss, Reference Prentiss1903, for comparison.

Fur dealer Manly Hardy (Reference Hardy1903, p. 125) of Brewer apparently read a preprint of Prentiss’ report and made the link between Prentiss’ (Reference Prentiss1903) archaeological discovery and a large Maine coastal mink he was personally familiar with. Here we quote his description of the “sea mink:”

Some seventy-five years ago, and for many years thereafter, my father, who was a fur-buyer, used to have nearly all the furs taken on the islands of Penobscot Bay, from the mouth of the Penobscot eastward to Frenchman’s Bay. Many of the mink, especially from Swan’s Island and Marshall’s Island, were fully twice as large as the mink from inland, the smallest of them being as large as the largest inland mink and the largest fully twice the size of their inland relatives. I remember frequently hearing them spoken of as being “as large as small cats.” Later I saw and handled many of these mink. Their fur was much coarser and was of a more reddish color than that of the inland, or as they were then called, the “woods mink,” to distinguish them from the “sea mink.” These sea mink were usually extremely fat, and the skins had an entirely different smell from that of the woods mink. I could with my eyes shut pick them out from the woods mink by their peculiar smell. In the old days, when mink were judged by size instead of by fineness and color, as was done later, these sea mink used to bring considerably more than others on account of their great size. On this account they were persistently hunted. Yet scarcely any were trapped on the islands. Instead, they were shot or hunted with dogs trained for the purpose. [A firsthand account of this kind of mink hunting can be heard in a voice recording preserved at the Fogler Library, University of Maine, which begins at 15:24: https://library.umaine.edu/content/NAFOH/audio/mfc_na0991_t0997_01.mp3] As the price of mink rose, they were hunted more and grew scarcer, till in the sixties, when mink skins brought eight or ten dollars apiece, parties who made a business of hunting nearly or quite exterminated the race. Some of these men went from island to island, hunting any small ledge where a mink could live. They carried their dogs with them, and, besides guns, shovels, pick-axes and crow-bars, took a good supply of pepper and brimstone [sulfur]. If they took refuge in holes or cracks of the ledges, they were usually dislodged by working with shovels and crow-bars, and the dogs caught them when they came out. If they were in crevices of the rocks where they could not be got at and their eyes could be seen to shine, they were shot and pulled out by means of an iron rod with a screw at the end. If they could not be seen, they were usually driven out by firing in charges of pepper. If this failed, then they were smoked with brimstone, in which case they either came out or were suffocated in their holes. Thus in a short time they were nearly or quite exterminated… The mink which are now taken on our seacoast along Penobscot Bay are quite large and the fur is coarse, but we get none of the great sea mink like those taken 40 or more years ago.

Hardy’s (Reference Hardy1903) account contributes four important facts regarding the sea mink: (1) it was coastal and quite distinct from the small “inland” or “woods” mink; (2) it had disappeared during his lifetime; (3) it was “fully twice as large as the mink from inland” and “extremely fat;” and (4) its coat was “much coarser” than the inland/woods mink and could be identified by its smell alone.

In 1909, Loomis (Reference Loomis1911, p. 227) recovered a partial skull and 45 sea mink mandibles from sites in Harpswell, Boothbay, Sorrento, and Winter Harbor, Maine. He also recovered “numerous individuals about 20 per cent smaller, but otherwise with the same characteristics, which I take to be the females, as there is in this family usually about this difference between the sexes.” His reasoning was parsimonious, reflecting the high frequency of sexual dimorphism in mammals, but it implicitly challenged Prentiss (Reference Prentiss1903) by characterizing his larger bones merely as a “form” [subspecies] of Lutreola vison antiquus (i.e., the modern mink, N. vision). It is noteworthy that although Loomis collected mink postcranial bones, he made no mention of them in his paper.

Hollister (Reference Hollister1913, p. 478–479) agreed with Prentiss that the sea mink should be considered a separate species:

The skull of this species is readily distinguishable from skulls of all the subspecies of [N.] vison by its large size and by the much larger teeth. The difference is so great that direct comparison or measurements are unnecessary, to separate it from all existing minks … It seems more than probable, therefore, that this species flourished on the Maine islands until comparatively late years, and was exterminated, in its limited distribution, by the modern fur trade.

Seton’s (Reference Seton1929, v. 2, pt. 2, p. 562–563) Lives of Game Animals … gave “probable measurements” for the sea mink (Table 1) and, like Hollister (Reference Hollister1913), supported Prentiss’s (Reference Prentiss1903) separate species view:

This seems to have been the species of Mink that was known in the Bay of Fundy as the Sea-mink or Big Mink and which became extinct about 1860. All that is known concerning it is D. W. Prentiss’ description of the fragmentary skull, and Manly Hardy’s memory of when it was common.

Norton (Reference Norton1930, p. 31) reported on mink skulls excavated in 1866 by Charles B. Fuller at Goose Island in Casco Bay, Maine, a site excavated by Loomis (Reference Loomis1911), but also commented upon large modern specimens, possibly of N. macrodon, from the eastern Maine coast that may have postdated Hardy’s (Reference Hardy1903) presumed extinction date of “forty or more years ago” (around 1860–1870).

Norton (Reference Norton1930, p. 31–32) also discussed a mounted specimen (the Clark specimen, referred to below), which was supposed to have been taken about 1894 on Campobello Island, New Brunswick but related to the sea mink he concluded:

The pronounced cranial characters of this mink indicate a species quite distinct from its congeners, while its massive bones, its large size, fat body and limited range indicate a sedentary species of specialized habits. This animal was evidently of ancient origin, representing a matured specific branch of the mink group, a relic type, like the lamented Labrador duck and the great auk. Though the range of this mink was probably more extensive than is at present known, it seems at best to have been confined in Quaternary time to a small habitat.

Allen (Reference Allen1942, p. 181–183) published on faunal remains excavated in 1913 by Warren K. Moorehead (Morehead, Reference Moorehead1922, p. 163–66) and concluded:

It seems probable that this big animal was the only form of mink to be found in the eastern part of the Gulf of Maine in earlier times. That it also ranged to Nova Scotia seems likely from the account by J.B. Gilpin (Reference Gilpin1867) [quoted above] … At the present day the mink occurring along the Maine coast represents Mustela vison mink [N. v. mink], the more southern race, of which a large male will seldom measure over 23 inches. Evidently this latter race, which has somewhat of a liking for seacoasts, has taken the place formerly held by the now extinct sea mink. Possibly, too, circumstances favorable to this eastward spread within the last century contributed to the driving out of the larger animal.

Manville (Reference Manville1966, p. 6–7) published an extensive reevaluation in “The Extinct Sea Mink, with Taxonomic Notes,” where he sided with Loomis against a separate species designation for the sea mink, but also paid considerable attention to the mounted “Clark specimen,” recording its smaller measurements as compared to Seton’s (Reference Seton1929, table 1). Related to sea mink, Manville (Reference Manville1966, p. 9–10) concluded:

I perceive in it no highly significant differences when compared with the other two specimens. The traits mentioned by Prentiss (Reference Prentiss1903), Hollister (Reference Hollister1913), and Norton (Reference Norton1930) — wide rostrum, large infraorbital foramen, low audital bullae, rugose parietal, basioccipital with strong knob—appear to me to be relatively minor in nature, and not of the magnitude generally considered as distinguishing species …

As attested by Hardy (Reference Hardy1903), a number of recognizably different forms of mink occurred along the New England coast a century ago. Many of the differences were probably attributable to individual or sexual variation. One of these forms, more distinct than others because of its large size, was pursued avidly for its pelt. Its seashore habitat rendered it relatively easy to capture. Overly zealous hunting, and possibly other factors of which we are unaware, led to its decline and, ultimately, to its complete replacement by other, smaller forms of mink.

All the evidence indicates to me that the sea mink is most realistically considered as a subspecies, now extinct, of the prevalent mink, Mustela vison [N. vison], of today. This view is strengthened if, as seems possible, the Clark specimen was indeed an intergrade between two other forms of mink. Accordingly, the sea mink should properly be known as follows: Mustela vison macrodon [Neogale vison macrodon] (Prentiss).

McAlpine et al. (Reference McAlpine, Huynh and Pavey2024, p. 171) have now settled the taxonomic status of the Clark specimen which has DNA sequence fragments that are “an exact match to N. vison.” Manville (Reference Manville1966, p. 3) repeated a claim by Waters and Ray (Reference Waters and Ray1961) of:

… remains of [N.] macrodon from an archeological site at Assawompset Pond in Middleboro, Mass. The bones were in excellent condition, although fire blackened. They have not been radiocarbon dated, although the excavator, Maurice Robbins suggested that they were associated with charcoal radiocarbon dated to 4300 ± 300 years.

We have examined these bones from the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ:Mamm:51076–51077) and question both their identification and their origin at this archaeological site. First, the left radius (MCZ:Mamm:51076) is not that of a mink but one of a much larger carnivore, a river otter (Lontra canadensis; Fig. 2). Second, because Manville’s (Reference Manville1966) publication was the first to identify mink using postcranial bones, we question the absence of metric data upon which that judgment was based. Third, our archaeological experience in New England indicates these bones were not burned but rather stained by soil humates. Carbonized bone can be durable in sandy acid soils such as those of the Assawompset Pond area, but unburned bones would have dissolved quickly. We therefore consider these bones to be among many objects putatively recovered from the site that other evidence suggests were not.

Figure 2. (A) Neogale vison mink ventral aspect of skull pictured with left radius 29.9.m785 from Turner Farm site. (B) Neogale macrodon sea mink; solid white outline, ventral aspect of fragment from base of skull, pictured with left radius 29.9.m454 from Turner Farm Site. (C) Lontra canadensis, North American river otter, ventral aspect of modern skull pictured with a modern left radius. Modified from Norton (Reference Norton1930, p. 29) for size comparison.

Black et al. (Reference Black, Reading and Savage1998) reported on large mink bones recovered from the Weir site on the Bliss Islands of coastal New Brunswick, which they considered to be N. macrodon (Black et al., Reference Black, Reading and Savage1998, p. 46) and concluded:

That Sea Mink bones have not been identified previously in the Quoddy region, despite a long history of archaeological research and extensive excavations … supports the interpretation that populations of Sea Mink were not present in the region in the past. The Bold Coast between Machias Bay and the Quoddy region, 30 km of rugged high-gradient shoreline unbroken by estuaries, may have served as a barrier limiting the northeastern distribution of the Sea Mink.

However, as we have seen from Gilpin (Reference Gilpin1867, p. 12), cited above, there is reason to think that the range of the sea mink did extend into the Canadian Maritime Provinces.

Nearly a century after Prentiss, Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000) revisited the dispute using a large sample of skulls from across North America, which they compared to Maine archaeological specimens, including some from sites we sampled (Mead et al., Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, p. 255). They also assessed a limited sample of postcranial bones using t-tests to compare their archaeological dataset to various modern N. vision subspecies. They concluded that the sea mink was “significantly larger than any of the living forms of the American mink, including the island-dweller of northwestern coastal North America” which led them to consider (Mead et al., Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, p. 256–257) two “readily apparent” alternative hypotheses: (1) two subspecies of Mustela [Neogale] existed in Maine: (1) a small coastal form indistinguishable from the living form today (M. v. mink) [N. v. mink], and (2) an unusually large subspecies, M. v. macrodon [N. v. macrodon], found predominantly on coastal islands; and (2) two species of Mustela [Neogale] existed in coastal Maine during the Middle and Late Holocene. A small species (M. v. mink) [N. v. mink] that lived in both interior and coastal regions, and a decidedly larger species (M. macrodon) [N. macrodon] that was isolated or restricted to islands off the coast.

Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, p. 258) concluded that “coastal and island remains of N. macrodon are more robust and significantly larger than all living forms of N. vison, and it should be retained as a separate species” and, specifically from their cranial data (Mead et al., Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, p. 259), that:

The distinctly large overall size, robustness, large external nares, and the proportionately large dental region in comparison to the bullae region warrant the designation of Mustela macrodon [N. macrodon] as a separate species.

Mead et al.’s (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000) data do show two non-overlapping size groupings representing N. v. mink and N. macrodon, but this distribution is obscured in Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, Figs. 9–13) by the inclusion of other mink subspecies of intermediate size, which give the appearance of size spectra and mask the discrete data clusters of large N. macrodon versus small N. v. mink. Moreover, Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, Figs. 10–13) failed to include N. v. mink data. Upon close inspection, Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, Fig. 9) shows that N. macrodon is the largest mink in their sample, and N. vison mink the smallest, with a size difference much larger, for example, than that between two Illinois subspecies reported by Peters et al. (Reference Peters, Axtell and Kohn2010).

Graham (Reference Graham2001, p. 419) nevertheless concluded “it is more parsimonious to assume that all of the specimens from a specific site are derived from a single local population.” Citing Humphrey and Seltzer (Reference Humphrey and Setzer1989), he noted “differences in size are one of the primary features distinguishing most of the modern subspecies of M. vison,” and “there is considerable overlap between the fossil and modern populations,” which he attributed to “sexual dimorphism that is prevalent in most modern mustelids.” In Graham’s (Reference Graham2001) opinion, Loomis (Reference Loomis1911) made “better ecological, evolutionary, and taxonomic sense,” and that even this wide range of metric variability is “not the result of the mixing of mainland and island populations.” Graham (Reference Graham2001, p. 420) concluded:

… the only real difference between the N. macrodon specimens and the modern subspecies of N. vison is the tendency toward a larger size for N. macrodon… Consequently, I believe that it is more reasonable to assign the macrodon phenon to M. vison macrodon as originally done by Manville (Reference Manville1966).

Sealfon (Reference Sealfon2007) approached the dispute using metrics on the dentition of 111 mature mink mandibles and maxillae from the Turner Farm archaeological site and from extant and fossil Musteloidea from the American Museum of Natural History (158 specimens), along with 84 specimens published by Popowics (Reference Popowics2003). Sealfon (Reference Sealfon2007, p. 377) found:

…numerous significant differences between the known specimens of N. macrodon and the known specimens of N. vison … For example, N. macrodon possessed broader upper and lower carnassial teeth and shorter upper carnassial blades, independently of body size and allometric scaling. When corrected for size and allometry, the dental differences between the sea mink and N. vison were much greater than those between sexes of N. vison or between subspecies of N. vison. The morphological distance between N. macrodon and N. vison, as assessed by dental proportions, was comparable to the distance between pairs of known musteloid species in the same subfamily. Thus … this study supports recognition of the sea mink (N. macrodon) as a species separate from N. vison.

Materials

Our archaeological mink data set (NISP >1200) included samples recovered from archaeological sites in the Penobscot Bay area (Fig. 1) that date between 4000 to about 400 14C yr BP (radiocarbon years before present). The largest was recovered from the Turner Farm site on North Haven, Maine (Spiess and Lewis, Reference Spiess and Lewis2001, p. 34–38, 73–75, 101). Others came from sites on Bar Island (ME Site 18.4), and Lairey’s Island (ME Site 29.65) near Vinalhaven Island. For comparative purposes, we added modern samples from locations elsewhere in New England, including 14 field collected specimens of the N. v. mink (common mink) and two specimens of the N. v. vison (eastern or little black mink), as identified by the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), Harvard University. The sex and age of all had been determined before being skeletonized. Of the 14 MCZ N. v. mink specimens, five came from Belfast, Maine (MCZ62555 male; MCZ62556 male; MCZ62557 male; MCZ62581 female; and MCZ62582 female) and nine came from Gardner, Massachusetts (all males MCZ61826; MCZ61835; MCZ61836; MCZ61837; MCZ61838; MCZ61839; MCZ61840; MCZ61851; and MCZ61864). The N. v. vison specimens came from Amherst, New Hampshire (MCZ904 male) and Upton, Maine (MCZ1170).

Methods

Since Prentiss (Reference Prentiss1903), analyses of sea mink bones have focused upon skulls. However, archaeologically recovered skulls have two disadvantages. First, skulls recovered from archaeological contexts are rare and usually badly fragmented. Second, they lack sexually diagnostic features. Moreover, the skulls in the collection used by Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000) have no provenience and included several ranch mink of unknown ancestry. We also excluded modern mink from North Haven, Maine, because they may descend from ranch mink released from an island mink farm that closed in the 1950s.

We chose to focus upon postcranial bones because they (1) are far more numerous in archaeological samples; (2) have been underutilized in morphometric analysis; (3) are ubiquitous in regional archaeological contexts; (4) possess metrics that reflect both sexual dimorphism and maturation rates, which are crucial in this taxonomic dispute; and (5) include the baculum, which identifies males. While previous archaeological mink bone studies have assumed the presence of females, their focus upon skulls made it difficult for them to identify females or to quantify sexual dimorphism. Our focus upon postcrania avoided these difficulties and allowed us to make maturity and sex assessments.

Archaeological postcrania are less fragile than mink skulls, but they too are often fragmentary and, in all our samples, are commingled in such a way that we can rarely associate two elements with any single individual. Therefore, we chose to analyze elements that were both abundant and indicative of maturity, or sex, or both, including humerus, radius, ulna, tibia, femur, pelvis, and baculum. To enhance sample sizes, we sought metrics that could be taken from both whole and fragmentary bones. All our measurements followed von den Driesch (Reference von den Driesch1976) unless otherwise stipulated.

Maturity

For sexually dimorphic species, identifying juveniles is important because their smaller size can cause them to be assigned to the wrong sex or even species. For example, a juvenile N. macrodon might plot metrically as an adult N. vison female, while a N. macrodon female might plot metrically as an N. vison male.

We consulted modern behavioral studies of mink as an aid in understanding the seasonality of capture. Mink have only a single annual litter born, in the northern hemisphere, between late April and very early May (Enders, Reference Enders1952, p. 719; Dunston, Reference Dunston1993, p. 146; DeGraaf and Yamasaki, Reference DeGraaf and Yamasaki2001, p. 351). Thus, long-bone fusion patterns can reveal the season of capture (death).

According to Petrides (Reference Petrides1950, p. 370), mink forepaw x-rays show possible differences in the ossification of the distal radius between the young and adults, but he mentioned little about fusion. Our observations on modern mink showed fully fused long bones in juveniles captured in November and December, indicating they had reached full adult size. Thus, specimen MSM 64 (Maine State Museum 64), aged at 2 months (July) based on tooth eruption, has a fused proximal radius and a closed fusion line on the proximal ulna, while the proximal humerus, distal radius, distal ulna, femur, and tibia remain unfused. Specimen MCZ 61571, collected on September 8, has a fused radius, ulna, and distal tibia, while the proximal tibia has a closed fusion line. The distal femur and proximal humerus both remain unfused. Thus, the fusion sequence timing for mink appears to be: radius → ulna → proximal femur → distal tibia → proximal tibia → proximal humerus. We applied these criteria to all long-bone elements, noting the presence of long-bone fusion lines, or absence of epiphyses. Representative juvenile elements are shown in Figure 3. Additional juvenile markers for the femur, pelvis, and baculum are addressed below.

Figure 3. Representative unfused (juvenile-aged) elements compared to adult specimens of the same bones from Turner Farm site (A–E) along with the pelvic ischium bone (modern and archaeological) as an indicator for adult males (F, G). (A) Humerus 29.9m250a with unfused proximal end, adult specimen 29.9.m198. (B) Radius 29.9m450 with unfused distal end, adult specimen 29.9.m475. (C) Ulna 29.9.m422 with unfused distal end, adult specimen 29.9.m396. (D) Tibia 29.9.m714 and 29.9.m719 with unfused proximal ends, adult specimen 29.9.m692. (E) Ilium 29.9.m748 with unfused iliac crest, adult male specimen 29.9m750 (F) Pelvis (MCZ 61838 adult male N. v. mink) showing ischium deposits common on adult males. (G) Two views of the posterior surface of ischium 29.9m6c showing additional deposits common on adult male mink. The far-right view includes the ilium 29.9.m6c separated by a post-depositional break.

Humerus

Distal humerus fragments are abundant, perhaps due to their greater density (Lyman, Reference Lyman1994) or, judging from numerous butchering cut marks on the bone, to their separation from the pelt during the skinning process. To compare humerus size across our samples, we measured breadth of distal end (Bd) versus least diameter (LD) (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Scatterplots of metric comparisons for elements: humerus, radius, ulna, tibia, femur, and pelvic ilium. Cluster A: modern female Neogale vison; Cluster B: modern male N. vison and archaeological cf. N. vison; Cluster C: N. macrodon for various postcranial skeletal elements.

Radius

We measured breadth of proximal end (Bp) versus depth of the proximal end (Dp) (Fig. 4B).

Ulna

We measured breadth across the coronoid process (BPC) versus depth across the anconeal process (DPA). Both are found on the most robust part of the ulna and thus were well represented (Fig. 4C).

Tibia

We used the proximal end of the tibia because it is much more abundant than the distal end. We measured breadth of the proximal end (Bp) versus the depth of the proximal end (Dp) (Fig. 4D).

Femur

We measured femur size by greatest length (GL) versus least diameter (LD; Fig. 4E), and identified juveniles by the size of the lateral supra-sesamoid tuberosity and by surface porosity of the cortex (Lechleitner, Reference Lechleitner1954, p. 498, pl. 1; Greer, Reference Greer1957, p. 320–321, pl. 1).

Pelvis

For size assessment we focused on the ilium shaft (Fig. 4F), comparing the smallest shaft height (SH) to smallest shaft breadth (SB). This comparison allowed us to avoid the distal blade portion of this bone, which is often damaged. The presence of juveniles was indicated by the unfused epiphysis of the iliac crest (Fig. 3E).

Some ilium specimens included the attached ischium, which allows separation of adult male mink from juveniles. The posterior surface of the ischium has a smooth edge in juveniles of both sexes, as well as in adult females, but becomes roughened in adult males (Figs. 3F and 3G). Bone deposition begins with yearlings, and becomes more pronounced with age (Greer, Reference Greer1957, p. 322, pl. 2; Birney and Fleharty, Reference Birney and Fleharty1968, p. 278). We identified those with a buildup on the posterior surface as adult males (Fig. 3G).

Baculum

Our baculum sample is highly fragmented, so we focused upon the proximal end, which is more robust than the distal end, and undergoes ontogenetic change. Here, we provide a new measurement taking the height of shaft (HS) versus breadth of shaft (BS) where the urethral groove terminates (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Baculum scatterplots. Left side of figure shows representative specimens as follows: Group A: Neogale vison MCZ 61840 juvenile. Group B: modern N. vison MCZ 61838 adult and archaeological specimens 18.4.m2, 29.65.m7, 29.65.m6, 29.9.m725. Group C: archaeological specimens 29.65.m3, 18.4.m1, and 29.65.m5. Group D: archaeological specimens 29.65.m2, 29.65.m1, and 29.65.m4. Right side of figure shows clusters as follows: Cluster A: modern juvenile N. vison; Cluster B: modern N. vison and cf. N. vison adult; Cluster C: N. macrodon juvenile and young adults; Cluster D: N. macrodon aged adults.

Elder (Reference Elder1951, p. 45) identified juveniles using total baculum length and weight. In juveniles, the baculum is slender and gracile, and the proximal end is very small, while in adults the proximal end becomes highly developed and the shaft considerably more robust. By January of the first year (eighth month?), the proximal end also begins to develop a circular ridge and a dorsal tip process (Petrides, Reference Petrides1950, p. 371; Elder, Reference Elder1951, p. 49; Birney and Fleharty, Reference Birney and Fleharty1968, p 276–277).

Isotopic analysis to determining diet

Both Mead and Spiess (Reference Mead and Spiess2001) and Graham (Reference Graham2001) suggested that diet may have played a role in the divergence between some mink subspecies, and perhaps it played a role in the emergence of the sea mink. To assess this hypothesis, we undertook an analysis of isotopic ratios of nitrogen (15N/14N, δ15N) and carbon (13C/12C, δ13C), including specimens that represented different ages and sexes. All samples were prepared after Burton et al. (Reference Burton, Snodgrass, Gifford-Gonzalez, Guilderson, Brown and Koch2001). Each bone was scoured with a Dremel tool to remove surface contamination, demineralized in 0.2 M HCl at 4°C for 2–10 days, and rinsed extensively in deionized water. Samples were then soaked in 0.25 M NaOH after decalcification for 24 hours to remove humic acids and other exogenous organic matter that contaminate the collagen, and then rinsed repeatedly in deionized water. Modern and archaeological bone collagen samples were lyophilized and stored in a desiccator until analyzed for stable isotopic composition.

Between 0.5 and 1.0 mg of each lyophilized bone collagen sample was analyzed for δ13C using a Thermo Delta V Advantage stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) interfaced to a Costech ECS4010 elemental analyzer (EA) via the Conflo III combustion interface, in the Department of Earth and Climate Sciences, at Bates College. All isotope compositions are reported in delta notation:

δ(‰) = ([Rsample/Rstandard] − 1) × 1000

where R = 15N:14N or 13C:12C. The δ15N standard is atmospheric air (AIR) and the δ13C standard is Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB). Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope compositions were calibrated relative to AIR and VPDB using National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standards (SRM 8540, SRM 8542, SRM 8537, SRM 8548, and USGS 40). Internal working standards (USGS 40: glutamic acid, acetanilide and freeze-dried cod muscle tissue) were calibrated to VPDB and AIR with the NIST standards and were used to monitor analytical uncertainty and the external precision. The external precision was determined by multiple analyses of a working standard (acetanilide: C8H9NO run every sixth sample) is ± 0.2‰ for both δ15N and δ13C.

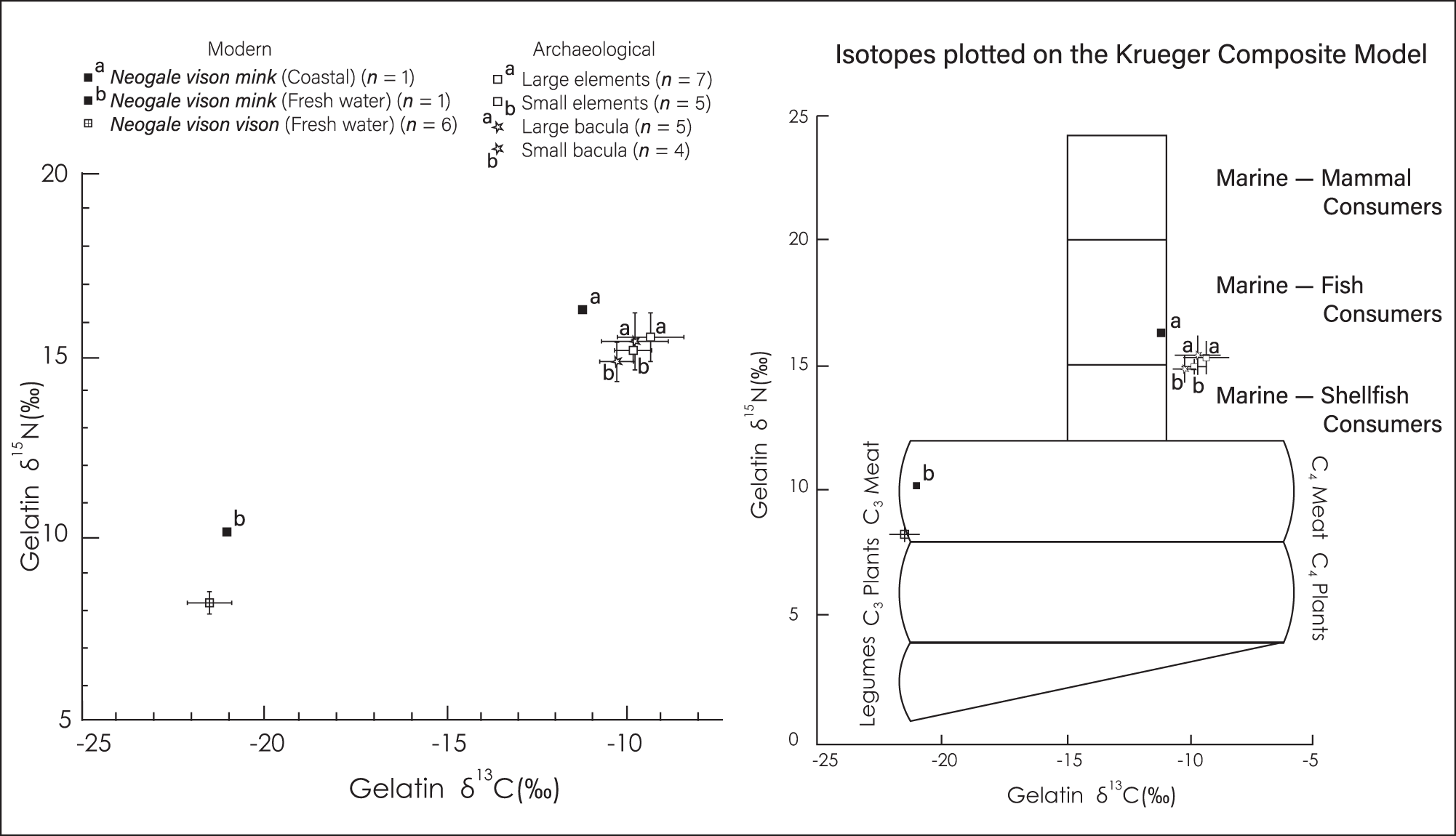

Our analysis included both modern and archaeological bones. Modern samples included eight mandibles, from specimens in the MSM collections: six N. v. vison (2004.64.1599sk, 1602sk, 1603sk, 1604sk, 1605sk, 1611sk) and two N. v. mink (2004.64.1598sk and 05434sk). Stable isotope values showing the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of δ¹⁵N and δ¹³C were plotted (Fig. 6) and presented on the Krueger Composite Model template (Bourque and Krueger, Reference Bourque and Krueger1994).

Figure 6. Left side: stable isotope biplot showing the mean ± SD δ¹⁵N and δ¹³C values for modern Neogale vison mink, N. v. vision, and archaeological samples. Right side: Same isotopes plotted on the Krueger Composite Model template (Bourque and Krueger, Reference Bourque and Krueger1994).

Our archaeological samples included six mandibles and six humeri from the Turner Farm site (29.9.m42, m108, m110, m366, m515, m546) and (29.9.m203, m210, m217, m217b, m241, and m251), respectively. We analyzed two bacula from Bar island (18.4m1, 1834m2), seven from Lairey’s Island (29.65.m1–m7), and one from the Turner Farm site (29.9.m725).

Graham (Reference Graham2001) suggested that strontium isotope analysis of archaeological bones would be a useful way to assess differential marine dietary protein intake. However, our past attempts to apply this technique to archaeological bones from the Maine coast failed because seawater spray and mist have contaminated island and near-coastal terrestrial soils, giving them a marine strontium isotopic signature (Krueger Reference Krueger1985; see also Alonzi et al., Reference Alonzi, Pacheco-Forés, Gordon, Kuijt and Knudson2020).

Results

We found isomorphic agreement (Fig. 4) in our metrics for the humerus, radius, ulna, tibia, femur, and ilium scatterplots. However, since the baculum scatterplot reflects only the presence of males, it shows a paired bimodality (Fig. 5).

Isotopic results

Figure 6 compares δ15N and δ13C values for the archaeological and modern samples. Sample sizes are listed for each group and are plotted with one standard deviation. For comparison, these same values are also plotted on the Krueger Composite Model template, as presented in Bourque and Krueger (Reference Bourque and Krueger1994) and Bourque (Reference Bourque1995, p. 140).

Discussion

Figure 6 shows isotopic signatures for two subspecies of modern mink (N. v. mink, common mink, and N. v. vision, eastern or little black mink), which co-occur in Maine, along with the isotopic signatures for the large archaeological mandibles and humeri, which we interpret as N. macrodon. This comparison could possibly include females but, as we explain below, we doubt their presence. The inclusion of bacula ensures a male-to-male comparison.

All archaeological samples show strong similarities in protein intake, particularly in their elevated ratios of δ15N, which is the more sensitive indicator of marine protein intake (Schoeninger et al., Reference Schoeninger, DeNiro and Tauber1983, p. 1381; Schoeninger and DeNiro, Reference Schoeninger and DeNiro1984). This similarity indicates that both large and small groupings reflect very similar proportions of marine dietary protein intake while, in contrast, samples from modern mink reveal a clear difference between coastal and inland diets.

Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000) and Graham (Reference Graham2001) differ slightly in how dietary differences might explain the size difference between the sea mink and N. vison. Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, p. 257) suggested a strong coastal versus island dichotomy where “two species of mink lived along coastal Maine during the middle and late Holocene, the smaller (M. v. mink) living in interior and coastal regions, while the decidedly larger species (M. macrodon) was isolated or restricted to islands off the coast. Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, p. 247) were influenced by a Pacific analog:

Many habitat-related parallels exist between coastal island mink of the Gulf of Maine and those of the Alexander Archipelago, southeastern Alaska, where the overall largest living subspecies of mink is found (M. v. neosolestes). [N. v. nesolestes, “island mink”].

Graham (Reference Graham2001, p. 421), on the other hand, cites the more modest analog between coastal and interior Alaskan brown bears, which was perhaps only sufficient to have caused a subspecies-level differentiation:

Variations in diet might suggest the best explanation. Brown bears (Ursus arctos) show clinal variation in body size throughout their modern range with the largest ones along the Alaskan coast and nearby islands, especially Kodiak Island (Kurtén, Reference Kurtén1973). The diet of these large individuals primarily consists of fish, especially salmonids (Pasitschniak-Arts, Reference Pasitschniak-Arts1993). McNab (Reference McNab1971) has shown the higher the protein content of an animal’s diet the larger size it will attain. Therefore, it is quite possible N. macrodon was a fish/mollusk eating mustelid.

We disagree with both Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000) and Graham (Reference Graham2001) for three reasons. First, interisland distances in the Alexander Archipelago often exceed five miles, and thus may be large enough to inhibit interbreeding. In coastal Maine (and especially Penobscot Bay), however, interisland distances are much smaller and unlikely to create a similar breeding barrier. Today, even non-aquatic deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and moose (Alces alces) routinely cross between the mainland and even the most remote offshore islands. Even some species of mice make such crossings (Crowell, Reference Crowell1973, p. 546–549). Moreover, the lower sea levels that prevailed in the past would have appreciably lessened these small interisland distances. Instead, our view is that the only habitat dichotomy useful in this discussion is between the island–coastal zone, where marine diets prevailed, and an interior one where such diets were absent. We acknowledge our samples come from island sites but view this selection as merely due to the relatively better preservation of island shell middens, protected as they are from modern development, which has destroyed so many mainland sites.

Second, our isotopic data reveal a story of dietary similarity between the large and small forms, not dietary difference. All our coastal mink, both large and small, archaeological and modern (Fig. 6) had diets in the range of marine fish and mollusk eaters while our inland mink exhibit diets that are distinctly non-marine. This dichotomy accords well with Hardy’s (Reference Hardy1903) characterization of two forms, the “sea mink” and the “woods mink.” Finally, our baculum sample, which includes both adult N. vison and the larger N. macrodon (Fig. 5), exhibits no dietary difference between the large and small groupings (Fig. 6).

Our evidence suggests that N. macrodon and N. vison co-occurred prehistorically on the coast and on the nearby islands, with N. macrodon dominating our coastal samples because it was more abundant there. Neogale vison was probably also present, contributing a few individuals to our samples, but was probably the lone inhabitant of the forested interior, as suggested by Hardy’s (Reference Hardy1903) use of the term “woods mink.” Its absence from the coast and islands during Hardy’s lifetime may have been due to the near total deforestation of that zone for agricultural purposes, mainly sheep raising.

Interbreeding mink subspecies are well known to intergrade (Hollister, Reference Hollister1913, p. 473–476; Whitaker and Hamilton, Reference Whitaker and Hamilton1998, p. 460; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Axtell and Kohn2010, p. 1464), a property exploited by ranchers to produce mink that are thought to be derived from “many if not almost all of these eleven known subspecies” (Shackleford, Reference Shackelford1949, p. 12). This fact, along with the presence of a natural hybrid/intergrade zone described by Peters et al. (Reference Peters, Axtell and Kohn2010), leads us to expect that mink hybridization between two distinct size classes would result in intermediate-sized offspring. A similar pattern of size intergradation is well established among canids, which suggests that this is a general property of carnivores (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019).

Like previous researchers, we initially assumed that females would be present in our sample. If so, we expected that our results should exhibit one of three patterns: (1) bimodal male versus female clusters resulting from a single sexually dimorphic form; (2) trimodal clusters including a large and a small form with a middle cluster (cluster B) comprised of females and perhaps juveniles of the large form and large males of the small form; or (3) a continuum between the largest and smallest bones, lacking discrete clustering, suggesting the presence of intergrades or hybrids between two forms.

At first glance, all data clusters in Figure 5 appear to share an isomorphic trimodal pattern, which seems a good fit with number 2, above. However, this apparently is not the best interpretation of our data because we think that females are absent, or nearly so, due to the seasonality of prehistoric mink procurement.

We considered the possibility that females were excluded by chance but rejected it on the basis of our large sample size (NISP > 1200). Female absence is also suggested by the near absence of juveniles (only 14 juvenile bones) recovered from the total sample (NISP > 1200), which remain close to their mothers until they disperse upon approaching maturity (Craik, Reference Craik2008, p. 58). We also reject the notion that the hunting catchment areas of prehistoric times may have been focused in a way that managed to avoid females. Granted that females have smaller home ranges than males and do not range widely following parturition, but the ranges of both sexes are small enough that they must have been easily encompassed by prehistoric mink hunting patterns. Instead, our analysis strongly favors a combination of prehistoric human hunting patterns and mink seasonal behaviors to explain the absence of females.

Speiss and Lewis (Reference Spiess and Lewis2001, p. 76, 154–158) showed that between 4000 to about 400 14C yr BP (radiocarbon years before present) mink were taken with remarkable consistency between February and May, with only one instance as late as June. We have no comparable analysis of the Lairey’s and Bar island samples, but assume a similar seasonality because, like the Turner Farm sample, very few juveniles are included, with only 14 juvenile bones recovered from the total sample (NISP > 1200).

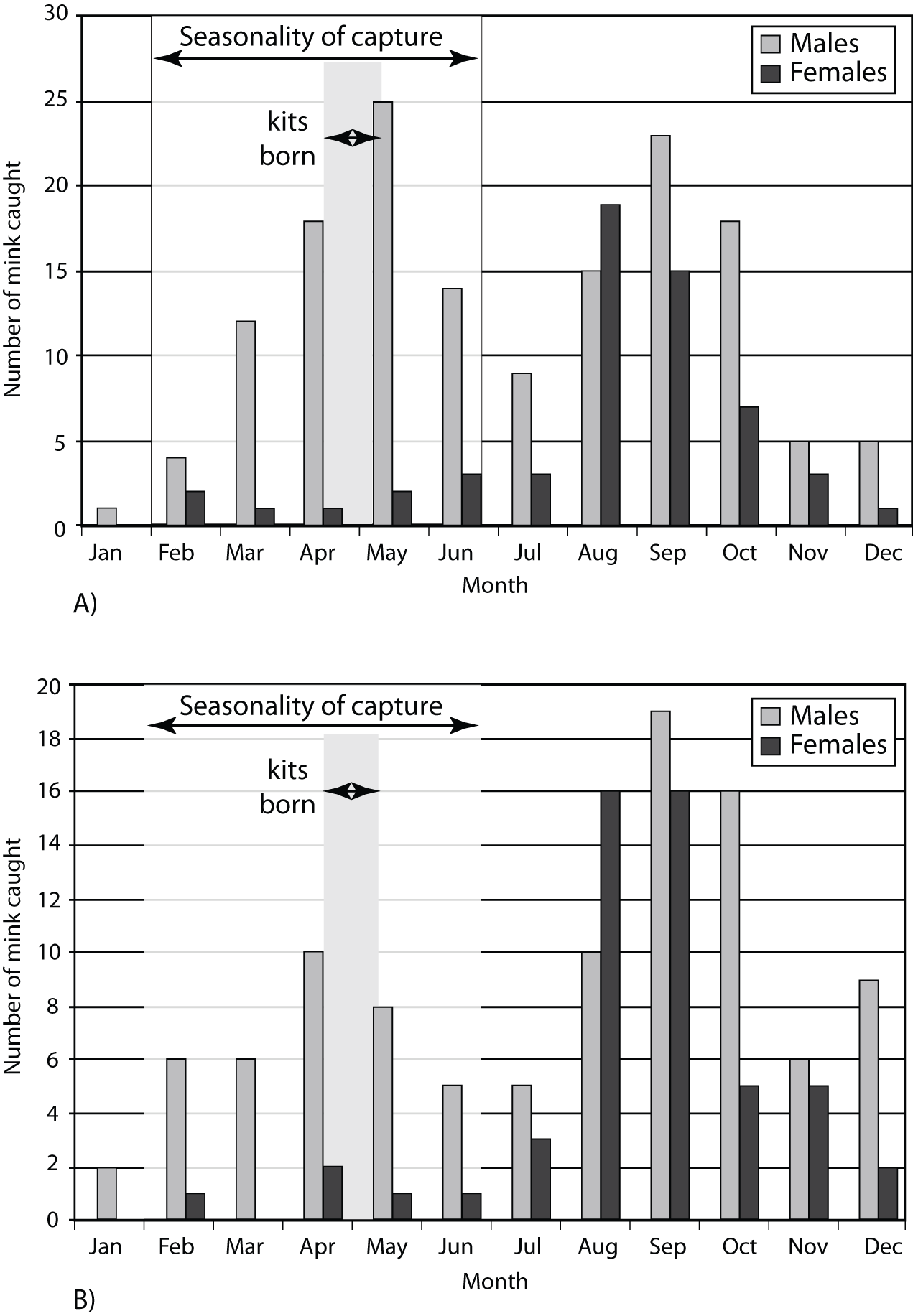

Observations of modern mink trapping reveal the likely reasons for the absence of females under such a hunting pattern. Lyman (Reference Lyman2007) noted that, for mustelids generally, more males than females are trapped, and that this imbalance is mainly due to behavioral differences between the sexes. Regarding N. vison specifically, Craik (Reference Craik2008) described trapping efforts in Scotland over a 10-year period (Fig. 7A and 7B), with most females captured in August–September, when the sex ratio was close to parity, but where, during the rest of the year, the catch was heavily biased towards males. Overall, Craik’s (Reference Craik2008) catch yielded an eight-fold difference in favor of males.

Figure 7. Timing of mink kits for Neogale vison, and the prehistoric to contact-period season of capture for our analyzed archaeological sites (A) overlain on data collected from 10 sites off the coast of West Scotland, 2003–2005 (modified from Craik, Reference Craik2008, figure 1) and (B) overlain on data collected from 5 sites, 1997–2006 (modified from Craik, Reference Craik2008, figure 2) for lower graph.

In sum, the February–May hunting pattern apparent in our sample assures that female captures were likely absent or nearly so. The reasons for such a seasonal pattern probably lies in sex differences in seasonal behavior. Marshall (Reference Marshall1936, p. 388) noted that males range widely during winter, while females tend to be far more restricted while rearing their young. Only in August–September, as juveniles disperse upon approaching maturity and females begin to establish winter territories, do both begin to be trapped along with males (Craik, Reference Craik2008, p. 58).

In essence, the consistent February to May hunt seasonality apparent in our data would likely have eliminated female mink from the sample. Figure 7 combines our seasonality data with Craik’s (Reference Craik2008) two sampling periods (2003–2005 and 1997–2006) to show how his 8:1 capture pattern (male to female ratio), and its near absence of juveniles conforms well to our seasonality reconstruction.

Size reduction in N. vison

Although incidental to our main research goals, we note that Figures 5 and 6 show a size reduction between archaeological and modern N. vison samples. If females are absent, as we have argued, their presence cannot explain this size difference, which leaves us without explanations to offer. We note that understanding variation in mink body size remains elusive. As Stevens and Kennedy (Reference Stevens and Kennedy2006, p. 149–150) stated:

Previous investigations of size variation in mammals have suggested that body size could be affected by productivity and seasonality of climate … These do not appear to be significant in mink … It appears that no single proposed or previously discussed cause can explain variation in the body size of mink. Variation in the body size of semi-aquatic mammals such as mink is likely the result of more than one factor …

Food or fur

Loomis (Reference Loomis1911, p. 227) suggested “In every case the mink had served as food for the aboriginal campers, so that the carcass had been pulled to pieces and the bones thrown away in various directions.” Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, p. 257) also suggested the “large local forms were preferentially selected as subsistence resources by prehistoric peoples, which in effect eliminated them from the local population through time.”

We disagree with these inferences for two reasons. First, the skeletal dismemberment and the scattering of bones is the general pattern for faunal remains recovered from Maine shell middens, whether for consumption as food, or for recovery of the hide/pelt. Second, human consumption of terrestrial carnivore meat is universally uncommon, and even if mink meat had been routinely consumed by prehistoric mink hunters, its tiny dietary contribution must have been trivial. Rather, because Spiess and Lewis (Reference Spiess and Lewis2001, p. 34) reported mink skeletal elements routinely show cut-marks that indicate skinning, we think mink were taken mainly for their pelts, although Loomis’ (Reference Loomis1911, p. 227) statement that “Every skull has the brain case broken and lost, the brain having been used for food” is probably correct.

Extinction

Prehistoric people in the study area captured sea mink in abundance over several millennia, whereas the kind of hunting described by Hardy (Reference Hardy1903) led to its extinction in little more than a century. How was the prehistoric hunting pattern sustained over time while the latter so quickly led to extinction?

As mentioned above, aboriginal exploitation of mink was probably not for food but rather to obtain pelt skins for clothing and accouterments. Likewise, the motivation for historic hunting and trapping of mink was to procure furs for garments. However, the former pattern likely operated mainly at a local subsistence level, whereas the latter fed a large international luxury market. Yet the magnitude of hunting pressure alone may be inadequate to explain the rapid extinction of the sea mink because the habitat they occupied was so rapidly repopulated by N. vison. Recalling Craik’s (Reference Craik2008) observations on N. vison trapping in Scotland, we suspect the crucial difference may have been the trapping bias of prehistoric times that captured all or mostly males, leaving intact the female population, and therefore the reproductive potential of the species.

Phylogenetic status

From the outset, we suspected that finding a fully satisfactory taxonomic status for the sea mink would prove difficult (i.e., whether it should properly be designated a subspecies, an ecomorph, or a separate new species). This difficulty is due in large part to a current discipline-wide uncertainty regarding a proper understanding of the species issue (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019).

However, turning finally to the phylogenetic implications of our analyses, we draw attention to the isomorphic similarities among our Figure 4 scatterplots, all of which show three distinct data-point clusters, which, since prehistoric females are absent, we infer to be Group C, N. macrodon (archaeological, males); Group B, N. vison (archaeological and modern, males); and Group A, N. vison (modern, females, species and sex confirmed by provenience). We posit the overall isomorphism of our scatterplots, along with the clear morphometric separation of our data clusters, rule out the presence of size intergrades that could suggest interbreeding between the large and small forms.

Moreover, these data demonstrate scales of difference appropriate to two distinct species, and thus suggest, from prehistoric time until the late nineteenth century, from Mid-coast Maine perhaps as far to the northeast as Nova Scotia, there existed two distinct forms of mink: the larger identified as N. macrodon (Prentiss, Reference Prentiss1903) and the smaller identified as identical to the surviving N. vison.

Modern literature classifies N. vison as having high phenotypic plasticity (Zalewski and Bartoszewicz, Reference Zalewski and Bartoszewicz2012, p. 681; Mucha et al., Reference Mucha, Zatoń-Dobrowolska, Moska, Wierzbicki, Dziech, Bukaciński and Bukacińska2021, p. 2), of which N. macrodon could be an extinct ecomorph. Our research, however, supports the views of Prentiss (Reference Prentiss1903) and Sealfon (Reference Sealfon2007) that N. macrodon meets the criteria for species status based upon (1) its distinct large size, (2) its marine-oriented habitat, and (3) the absence of any intermediate-sized animals that would suggest interbreeding between N. macrodon and N. vison (Figs. 4 and 5).

Finally, we suspect the disappearance of sea mink from the Gulf of Maine’s rocky coastline may have had a significant effect upon the region’s avifauna. Craik (Reference Craik1998) and Mavor et al. (Reference Mavor, Parsons, Heubeck and Schmitt2006) showed that the introduction of N. vison caused a significant reduction in the breeding success of gulls and terns. This was the motivation for the mink trapping programs they described. Their outcome, where mink were successfully removed, was the resumption of island birds normal breeding along with maintained or increased populations.

In this regard, we find it worth mentioning that Larids, which today are superabundant on the Maine coast, are absent from Maine shell midden faunal assemblages. If the diminutive N. vison can depress the breeding success of these birds when introduced, we suspect the presence of the much larger N. macrodon might have prevented their successful breeding throughout its range. Turning to historical accounts, the most comprehensive is Denys (Reference Denys1908, p. 375) who in 1674 listed gulls as present in eastern Maine and the Canadian Maritimes. However, while claiming to describe wildlife in all of Acadia (then all eastern Maine and the Canadian Maritime Provinces), he was actually based on Cape Breton Island, far to the east of any identified N. macrodon remains, where Larids may have thrived.

Evolutionary history

Mink studies (Enders Reference Enders1952, p. 693; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Axtell and Kohn2010, p. 1464) show that interbreeding often persists among modern North American mink forms that may have evolved in place. Our research, however, demonstrates that, although N. macrodon and N. vison occupied the same range and shared similar diets, their skeletal remains show no evidence of size intergrades, the outcome we would expect if the two forms had interbred.

Regarding evolutionary history, Mead et al. (Reference Mead, Spiess and Sobolik2000, p. 260) suggested “The sea mink progenitor, N. vison, probably arrived in the Gulf of Maine region from the south, along with the poplar woodland landscape, about 13,000 years ago. A ‘true’ N. macrodon may not predate 7000–6000 yr B.P.” We suspect that more probably N. macrodon diverged from ancestral N. vison somewhere to the south of Wisconsin glaciation to an extent that led to their reproductive isolation when their ranges converged in the Maine region during the Holocene. The available data also suggest the aquatic N. macrodon was more coastally adapted (Fig. 8) and, when it entered its historical range, it partially displaced the semi-aquatic N. vison, which remained the sole or dominant interior form. This scenario would be similar to that described by Peters et al. (Reference Peters, Axtell and Kohn2010, p. 1464) of two size-differentiated mink populations that apparently expanded in Illinois after the Wisconsin glaciation, but maintained an intergrade/hybrid zone, except that in Maine the two size-differentiated forms had become sufficiently differentiated to prevent hybridization.

Figure 8. Inset taken from (Jackson, Reference Jackson1837, pl. XVII). Based on the timing of the Jackson survey we suspect the animal depicted in this lithograph is a sea mink, observed somewhere between Thomaston and Eastport, Maine (left). To the right a recent photograph of Neogale vision is included for comparison.

Hardy’s (Reference Hardy1903) reference to the sea mink as a coastal dweller, in contrast to his “woods mink,” brings to mind two North American fissipeds (furred marine mammals), the polar bear (Ursus maritimus) and the sea otter (Enhydra lutris), both of which appear to be on an evolutionary trajectory away from a terrestrial adaptation toward a marine one. We suggest the sea mink may have been on a similar evolutionary path toward becoming a true marine fissiped. Mansueti (Reference Mansueti1954), for example, noted that one of his informants, a conservationist from Mount Desert Island, observed that although the sea mink lived coastally, they “stick to fresh water spring brooks.” Similar behavior has been noted among otters (Lutra lutra L.) known to feed in the sea in Scotland. These otters apparently remain sufficiently dependent upon their ancestral freshwater habitat to require maintaining their fur’s underwater insulating capacity by periodic grooming in fresh water (Kruuk and Balharry, Reference Kruuk and Balharry1990).

We agree with both Mead and Spiess (Reference Mead and Spiess2001) and Graham (Reference Graham2001) that a better understanding of North American mink evolutionary history would contribute greatly from a comparative analysis of prehistoric and modern mink DNA. More broadly, such an analysis might add significantly to our understanding of how mammals of all kinds repopulated deglaciated North America following the last Ice Age. At the very least, it would resolve the nagging possibility that a few prehistoric N. macrodon females may be lurking.

Conclusion

We used a series of standard and novel metric and isotopic analyses in an attempt to clarify the long-disputed taxonomic status of the sea mink. Implicit in this dispute has been the assumption that both sexes are represented in archaeologically recovered bone samples from Maine coastal sites. We conclude the bones of females are absent from our faunal samples, and it is this absence that has allowed us to define clear and concordant morphometric age-distinct data clusters among males that distinguish between two size-differentiated groups. When compared to modern male and female Neogale vison, these data clusters overlie our prehistoric smaller group, with the addition of a cluster of even smaller modern females, the smallest of all mink in our study. These results demonstrate the presence of two distinct forms of mink which we equate to the extinct N. macrodon and to N. vison, the modern mink.

Our isotopic analysis found no differences between the marine-weighted diets of the two forms, discrediting the notion their size differences could be explained by diet, but also underscoring the difference in diet between inland and modern coastal mink.

We now judge Prentiss’ (Reference Prentiss1903) separate species designation to be more correct. Nevertheless, because we cannot directly observe ancient mink mating patterns, we cannot give full weight to the separate species status of sea mink. That decision awaits a comprehensive paleogenetic assessment of all North American mink, which, incidentally, would definitively resolve any uncertainty regarding the presence or absence of prehistoric female N. macrodon.

Possible survival?

Finally, while we and most of the authors cited in this paper have written as if the sea mink slipped into extinction sometime during the late nineteenth century, we here offer two fascinating accounts, one from Manville (Reference Manville1966, p. 4–5) related to him by Arthur Stupka, Acadia National Park Naturalist from 1932 to 1935, regarding his interview with Capt. Rodney Sadler of Bar Harbor, and a second from Thomas W. Berube, a retired master taxidermist, lifelong Maine trapper and sportsman.

Sadler

Sadler recalled seeing the “bull mink” as late as perhaps 1920, swimming from one island to another in the Sorrento [Maine] region. It made its home on the oceanfront, among the rocks of a seawall piled up by the surf. Its den always had two entrances. An adult and four young, which Sadler estimated to be 3 or 4 weeks old (8–10 inches long), were seen along the beach of Sister’s Island in August. This was “40 odd years ago.” The young were very attractive, lighter in color than the dark brown adult. The bull mink were said to feed almost entirely on fish; the most common remains about their dens were of toad sculpin and horned pout.

Berube

I bought my 14-foot Grumman boat in 1987. Approximately 3 years later is when the first incident occurred. It was mid-December and my friend and I were going duck hunting on Middle Bay [Brunswick, Maine]. It was a cold but calm morning. My friend likes to hunt black ducks and my favorite species is goldeneye. So, I dropped him off at the house blind located on the northeast side of Birch Island. This is a tidal flat at low tide and frequented by black ducks. I set up a short distance away on Little Birch Island on the east side in deeper water for goldeneye. At the time the limit on black ducks was one bird. The agreement was that he would shoot his one duck, I would go retrieve the duck, him, and his decoys and he would finish the hunt on Little Birch hunting goldeneye. About a half hour to 45 minutes later, on an incoming tide, I heard him shoot and yell. I assumed he had shot his black duck. Then I heard more shooting, and more shooting. I hurried because I thought the duck was wounded. When I arrived, I realized he was shooting at seagulls who were trying to take what I thought was his duck. When I asked him where the duck was, he told me it was a mink. He said it was after his cork decoys and he had to shoot it! I never believed him!! I retrieved from the water the largest mink I had ever seen in my life! He wanted me to tag it for him and I refused because I did not want to be associated with a mink that was illegally harvested. He purchased a trapping license, had the mink tagged and sold it to Ken Gurschick. Ken was the owner of Twin Town Rendering and a lifelong fur buyer. He, too, had never seen a wild mink that large. His take was that it was a ranch mink that somehow got away and became wild.

Approximately 10 years later in early December I was alone hunting an outgoing tide on Middle Bay and had taken my limit of waterfowl. The weather was cool, and the wind was dead calm, and it was bright sun. I had gone back to Lookout Point boat launch to take my boat out of the water. At that point the tide was half out. I took my time just to enjoy the day as I cranked my boat onto the trailer. I observed a waterfowl swimming around the end of Lookout Point very close to shore. I got my boat on the trailer and tried to identify what species of duck it was and realized it was not a duck. As it got close, I thought it had to be an otter. The only thing wrong was it did not dive, and otters spend as much time under water as on top. As I kept watching, it swam close to me and went to a very small island on the other side of the boat launch. A mink climbed out of the water onto the rocks and shook the water off itself and started poking and looking around in the rocks and eventually disappeared onto the island. It was the size of a medium otter. At that moment, I truly believed Sea Mink were not extinct and I not only had held one in my hands but saw a second one alive.

The two animals I observed may not have been Sea Mink, but they were certainly not American Mink, as I have trapped for 58 years and have not seen one that size.

To the best of my recollection, this is what I observed.

Respectfully submitted,

Thomas W. Berube 5/24/2024

If, as these accounts suggest, the sea mink persists in low numbers along the Maine coast, it won’t be the first marine fissiped to have unexpectedly survived a brush with extinction. The southern sea otter (Enhydra lutris nereis) was once thought to have been hunted to extinction for its fur, but a small population was discovered off the coast of Big Sur, California, by lighthouse keeper John W. Astrom in 1915 (Life Magazine Staff Writers, 1938). Since then, this subspecies of sea otter has reclaimed about 13 percent of its historical range.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/qua.2025.2.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, this work would not have been possible without the isotopic analysis provided by Dr. Bev Johnson, Bates College, Maine. We are grateful to the owners of the archaeological sites where we recovered the bone samples used in this analysis. These include Ms. Dorothy Ames and William and Elsie Rice of North Haven, Maine, the family of David Strater of Portland and Vinalhaven, Maine, and Judge Bailey Aldrich of Cambridge, Massachusetts and Tenants Harbor, Maine. Collection access was provided by Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ) Mammalogy Department. Lastly, this manuscript benefited greatly from the efforts of two anonymous reviewers.