Introduction

In modern society, the advancement of technology has transformed communication patterns, and the majority of human interaction is mediated through mobile technologies (Michel & Stiefenhöfer, Reference Michel, Stiefenhöfer, Sato and Loewen2019). Mobile technologies have emerged as an essential mediating tool for second language (L2) teaching and learning (Jung, Reference Jung2018). This study investigates mobile chat interaction during L2 Korean pedagogical tasks from the perspective of linguistic alignment, which refers to “the development of aligned representations via an automatic psycholinguistic priming mechanism that acts on every level of linguistic representation” (Branigan et al., Reference Branigan, Garrod, Pickering, Brooks and Kempe2014, p. 13). Specifically, alignment occurs when interlocutors reproduce or demonstrate faster processing of previously heard or read linguistic constructions at various levels including lexical, grammatical, and phonological features, and it functions as either an intentional joint activity during dialogue or reflects automatic implicit processes (Garrod & Pickering, Reference Garrod and Pickering2009). The following exchange illustrates alignment, where after encountering a relative clause with a stranded preposition (line #1), the student reproduced the same construction when describing a photo (line #2) in the subsequent turn during the picture description task (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Jung and Skalicky2019, p. 947).

-

1. Researcher: This is something you dry dishes on. (Prime)

-

2. Student: Dish rack. This is something you cook on. [A picture of a “stove” and the verb “cook” were provided]

-

3. Researcher: Stove.

Previous L2 linguistic alignment research demonstrated both occurrence and facilitative effects of alignment in interaction-driven L2 learning (see Kim & Michel, Reference Kim and Michel2023 for a review). In a recent review article, Kim and Michel (Reference Kim and Michel2023) identified oral interactions as the major communication medium in L2 alignment research, with an increasing number of studies examining alignment during synchronous computer-mediated communication (SCMC; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Jung and Skalicky2019; Michel & Stiefenhöfer, Reference Michel, Stiefenhöfer, Sato and Loewen2019). Despite the pervasiveness of mobile-mediated interactions, little is known about linguistic alignment during mobile text-chats, or how various learner characteristics (e.g., L2 proficiency, mobile literacy) affect alignment. Moreover, whether the source of alignment during interaction (i.e., the provision of primes or recast primes) affects the degree of alignment and subsequent learning remains to be examined.

Furthermore, previous research has predominantly investigated three types of linguistic alignment—syntactic, lexical, and phonological alignment—without systematic investigations at other linguistic levels such as pragmatics (see Kim & Michel, Reference Kim and Michel2023). Given the critical role of pragmatics in communication, investigating linguistic alignment at the level of pragmatics merits attention. This is particularly relevant for languages such as Korean that require honorific expressions depending on interlocutors’ social distance and power relations. Understanding the extent of pragmatic alignment during joint dialogues and potential of alignment-based instructional interventions to facilitate pragmatics development warrants further investigation. Additionally, previous interaction-driven alignment research has primarily examined dialogic interaction, leaving group interactions with more than two people underexplored (e.g., McDonough & Kim, Reference McDonough and Kim2009; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Skalicky and Jung2020).

To fill the aforementioned gaps in the literature, the goal of the current study is twofold: (1) to examine how the source of alignment (prime vs. recast prime), L2 proficiency, prior knowledge of the target feature, mobile literacy, and Korean typing skills influence the occurrence of pragmatic alignment during group mobile text-chat tasks among L2 Korean learners; and (2) to investigate the effects of the source of alignment (prime vs. recast prime), L2 proficiency, and prior knowledge of the target feature on both immediate and delayed pragmatic development.

Literature review

L2 alignment during text-chat

Most L2 alignment research has examined oral interactions in face-to-face (FTF) contexts (e.g., Conroy & Antón-Méndez, Reference Conroy and Antón-Méndez2015; McDonough & Chaikitmongkol, Reference McDonough and Chaikitmongkol2010; McDonough & Kim, Reference McDonough and Kim2009). With the widespread use of technology-mediated communication, many studies have examined L2 linguistic alignment during digitally mediated interaction (e.g., Collentine & Collentine, Reference Collentine and Collentine2013; Coumel et al., Reference Coumel, Ushioda and Messenger2022; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Jung and Skalicky2019; Michel & Cappellini, Reference Michel and Cappellini2019), particularly during SCMC (i.e., text-chat). Linguistic alignment during text-chat has attracted L2 researchers’ attention due to its facilitative features for L2 development, such as visual salience, permanence of chat logs, and sufficient time to compose and review production (see Michel & Stiefenhöfer, Reference Michel, Stiefenhöfer, Sato and Loewen2019, for a review of text-chat characteristics supporting L2 learning).

Previous studies examining alignment during text-chat have addressed whether linguistic alignment occurs in SCMC contexts, whether FTF and SCMC alignment manifests similarly or differently, and how linguistic alignment emerges in two different settings of SCMC (e.g., videoconferencing vs. text-chat). For instance, Uzum (Reference Uzum2010) analyzed interactions among 18 speakers of English (native, advanced, and intermediate levels) and found alignment in the areas of fluency, typing speed, accuracy, and lexical and grammatical features. Collentine and Collentine (Reference Collentine and Collentine2013) documented 53 L2 Spanish learners’ convergences with nominal-clause syntax during text-chats in a 3D virtual environment.

Considering the different characteristics of FTF and SCMC settings, which produce qualitatively different interactional patterns affecting linguistic alignment, Kim and colleagues compared syntactic alignment effects in FTF and SCMC settings. Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Jung and Skalicky2019) examined the occurrence of linguistic alignment among Korean college learners of English and its impact on subsequent learning of stranded prepositions. They found that learners aligned their use of the target structures in both environments, but alignment occurred significantly more in the SCMC context than in the FTF context. Regarding learning outcomes, no significant differences between SCMC and FTF contexts emerged. In another study, Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Skalicky and Jung2020) examined different constructions (wh-questions with inversion/direct questions vs. indirect wh-questions). Their findings revealed that while learners exhibited more alignment with direct questions in the SCMC context compared to the FTF context, no significant modality effect emerged with indirect questions. This differential pattern may be attributed to structural differences between direct and indirect questions.

Michel and Cappellini (Reference Michel and Cappellini2019) investigated two different SCMC modes—videoconferencing (oral context) and text-chat (written context)—and their influence on linguistic alignment. Drawing on data from 10 hours of online interactions among L2 learners, their analysis revealed the presence of syntactic alignment in both settings. However, more frequent linguistic alignment occurred in text-chat than in videoconferencing, indicating the possible contribution of heightened salience in written text-chat.

Recent alignment studies extended the existing linguistic alignment literature by investigating the potential of text-chat-based alignment in L2 pedagogy. Coumel et al. (Reference Coumel, Ushioda and Messenger2022) demonstrated how alignment during text-chat facilitates the learning of multiple simultaneously targeted L2 structures. Forty-seven Spanish learners of English performed a chat-based alignment task with a researcher, which targeted three English constructions (of genitives, passive sentences, and double object datives). Results documented the L2 learners’ alignment during text-chat, demonstrating that alignment-driven learning extended to multiple target structures.

In the body of research on text-chat-based alignment, the majority of studies have concentrated on syntactic alignment, with relatively few addressing lexical alignment. Operationalized as “the reuse of a partner’s lexical choices of three or more consecutive words” (Michel & O’Rourke, Reference Michel and O’Rourke2019, p. 53), Michel and colleagues analyzed lexical alignment among L2 learners and found that lexical alignment occurs during digitally mediated communication (Michel & O’Rourke, Reference Michel and O’Rourke2019; Michel & Smith, Reference Michel, Smith, Gass, Spinner and Behney2018).

Overall, text-chat-based alignment studies have established that linguistic alignment occurs more frequently in the SCMC context than in the FTF context. This heightened alignment may stem from affordances of text-chat (e.g., more time to formulate sentences, availability of produced output during interaction, having characteristics of both oral and written modality (including spoken-like interaction and written output), which reduces learners’ cognitive load, enabling learners to pay attention to linguistic forms (noticing; Jung, Reference Jung2018; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Jung and Skalicky2019, Reference Kim, Skalicky and Jung2020; Michel & Stiefenhöfer, Reference Michel, Stiefenhöfer, Sato and Loewen2019). Previous research demonstrates that both syntactic and lexical alignment emerge among L2 learners during digitally mediated communication.

Given text-chat’s prevalence with mobile devices, investigating text-chat-based linguistic alignment in a mobile environment (e.g., smartphones) warrants attention. In the current digital era, mobile phones are virtually ubiquitous, and L2 learners are intimately familiar with mobile text-chats; examining the interactional features of mobile text-chats such as alignment and their subsequent learning outcomes is timely. A pioneering study by Jung (Reference Jung2018) compared FTF and synchronous mobile-mediated communication (SMMC) examining syntactic and lexical alignment, and alignment-driven L2 development. Jung demonstrated that while alignment occurred in both FTF and SMMC modes, the SMMC interaction elicited significantly more syntactic alignment than FTF interactions. No significant difference emerged for lexical alignment. These results supporting SMMC interaction necessitate further research examining linguistic alignment during SMMC interactions.

As L2 linguistic alignment studies have examined three main areas: syntactic, lexical, and phonological alignment (Kim & Michel, Reference Kim and Michel2023), existing literature lacks investigations into other types of linguistic alignment, such as pragmatics. Given that pragmatics plays an essential role in facilitating mutual understanding among interlocutors and promoting convergence, examining alignment at the level of pragmatics is warranted.

Recast as a source of alignment

The effects of recasts (i.e., an interlocutor’s provision of correct forms in response to an individual’s incorrect utterance) as oral corrective feedback in L2 acquisition have been examined widely (see Goo Reference Goo2020 for a review). Notably, previous studies tended to focus on grammar, and the limited research has shown the benefits of recasts in learning L2 pragmatics, particularly when compared to no feedback condition (c.f. Fukuya & Zhang, Reference Fukuya and Zhang2002; Fukuya & Hill, Reference Fukuya and Hill2006; Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Pham and Pham2012). L2 alignment researchers demonstrate that recasts function as a source of alignment provided by the teacher in response to an L2 learner’s non-target-like utterance (Michel & Cappellini, Reference Michel and Cappellini2019; Trofimovich et al., Reference Trofimovich, McDonough and Foote2014). In previous L2 alignment studies, recasts have been conceptualized as a form of prime, and a learner’s uptake (i.e., a learner’s response to corrective feedback, Lyster & Ranta, Reference Lyster and Ranta1997) has been considered as primed production, as seen in the following example (McDonough & Mackey, Reference McDonough and Mackey2006, p. 705). More specifically, a native speaker provides a recast by reformulating a non-target-like component in response to a learner’s incorrect utterance (line #1); thus, recasts model a target-like form (line #2). In the following turn when the learner produces a new utterance using the same structure that appeared in the recast, this learner’s response to the recast is seen as primed production (line #3) (McDonough & Mackey, Reference McDonough and Mackey2006).

-

1 Learner: Why he hit the deer?

-

2 Native speaker: Why did he hit the deer? [recast prime] He was driving home and the deer ran out in front of his car.

-

3 Learner: What did he do after that? [primed production]

McDonough and Mackey argued that this type of response to recasts remains fundamentally different from immediate repetitions of a recast (i.e., simple imitations) because in primed productions, learners generate novel utterances using the same structure but with different lexical verbs and nouns, which impacts L2 learning and development.

Through examining linguistic alignment, McDonough and Mackey (Reference McDonough and Mackey2006) investigated the relationship between the development of L2 English questions, recasts, and learners’ responses to recasts. By conceptualizing recasts as a prime provision condition and learners’ responses to recasts as either repetition or primed production, they found a significant association between primed production of developmentally advanced question structures and L2 English question development. Their findings revealed that linguistic alignment emerged when recasts were given during interactions between an L2 learner and a native speaker interlocutor.

Corrective feedback research indicates that text-based SCMC enhances the effect of recasts on L2 development due to increased detection of the intents of recasts, decreased cognitive load, and enhanced cognitive comparison (Smith, Reference Smith and Hult2010, Reference Smith2012; Smith & Renaud, Reference Smith, Renaud, McDonough and Mackey2013; Yilmaz, Reference Yilmaz2012; Yilmaz & Yuksel, Reference Yilmaz and Yuksel2011). Specifically, the re-readability of learners’ non-target-like utterances and written recasts and the resulting greater processing time facilitate the detection of corrective intent in recasts among learners (Yilmaz, Reference Yilmaz2012), while heightened visual saliency enhances cognitive comparison between learner production and recast (Smith, Reference Smith and Hult2010).

From the perspective of evidence availability in input, recasts carry both positive and negative evidence as they provide model examples through reformulation of non-target-like elements (i.e., positive evidence). Furthermore, recasts are offered after a learner’s incorrect production, suggesting that the learner’s utterance has a non-target-like component (i.e., negative evidence). Following this conceptualization of recasts, this study views recasts as a source of alignment along with primes, which are intentionally provided prior to targets in tightly controlled L2 alignment research.

Factors affecting L2 alignment: L2 proficiency, prior knowledge, and digital literacy

In addition to scholarly efforts to examine L2 learning via linguistic alignment as a learning condition, researchers have begun to investigate individual differences to understand why alignment does not always occur with all learners and why the degree of alignment differs among learners (Jackson, Reference Jackson2018). Current alignment literature suggests that such differences are associated with learner characteristics, such as L2 proficiency and prior knowledge of target linguistic elements (Michel & Stiefenhöfer, Reference Michel, Stiefenhöfer, Sato and Loewen2019). L2 proficiency has attracted considerable attention from L2 alignment researchers due to empirical evidence from the studies that demonstrate the positive role of L2 proficiency in cross-linguistic syntactic alignment (Bernolet et al., Reference Bernolet, Hartsuiker and Pickering2013; Schoonbaert et al., Reference Schoonbaert, Hartsuiker and Pickering2007).

For example, Kim and McDonough (Reference Kim and McDonough2008) examined how L2 proficiency affects Korean EFL learners’ aligned production of English passives during a collaborative alignment activity. Their analysis revealed that learners with higher L2 proficiency produced more of the target structures during the alignment activity, demonstrating the positive influence of L2 proficiency on linguistic alignment. Similar results were found in a later study by Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Jung and Skalicky2019), which examined syntactic alignment with stranded prepositions in relative clauses among EFL college students. Kim and colleagues found that learners with high proficiency produced a greater number of stranded prepositions than learners with low proficiency during SCMC performance. However, other studies did not find such positive associations between L2 proficiency and linguistic alignment. For example, Jung (Reference Jung2018) examined whether Korean EFL learners’ L2 proficiency correlated with the strength of syntactic alignment, but no modulating effect of L2 proficiency was found.

L2 linguistic alignment research indicates that prior knowledge of target constructions can play a facilitative role in alignment (e.g., McDonough, Reference McDonough2006). McDonough and Fulga (Reference McDonough and Fulga2015) investigated the role of L2 learners’ detection of a novel structure (i.e., the Esperanto transitive construction) in alignment and demonstrated the positive effects of detection (i.e., prior knowledge) on alignment. Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Jung and Skalicky2019) examined whether prior knowledge of target structures (i.e., English stranded prepositions) influenced the degree of linguistic alignment and alignment-driven learning of target features. Their analysis revealed the positive impact of prior knowledge on aligned production during interaction and subsequent learning. However, a follow-up study by Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Skalicky and Jung2020) did not find such a significant relationship between prior knowledge and alignment for English question forms. More recently, Coumel et al. (Reference Coumel, Ushioda and Messenger2022) reported supporting evidence for the positive role of prior knowledge in alignment, showing that participants with a higher level of prior knowledge of of-genitives more frequently aligned during an alignment task.

The conflicting findings from previous studies are difficult to explain, but Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Skalicky and Jung2020) attributed these variations to the different measures of prior knowledge. While Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Jung and Skalicky2019) measured prior knowledge using a grammaticality judgment test, which drew on both implicit and explicit knowledge, Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Skalicky and Jung2020) assessed learners’ previous knowledge of question forms using an oral production test, which assessed implicit knowledge in the production mode.

Several studies have examined linguistic alignment in a computer-mediated text-chat environment (e.g., Coumel et al., Reference Coumel, Ushioda and Messenger2022; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Jung and Skalicky2019, Reference Kim, Skalicky and Jung2020; Michel & Smith, Reference Michel, Smith, Gass, Spinner and Behney2018; Michel & O’Rourke, Reference Michel and O’Rourke2019). Because text-chat communication depends on digital competencies such as mobile, computer, and typing literacy, learners’ varying levels of digital proficiency may influence the extent of linguistic alignment during text-chat interactions. However, despite its possible mediating role in linguistic alignment, no previous studies have systematically investigated how digital literacy influences the occurrence of alignment and alignment-driven L2 development. Furthermore, as the Korean language has a unique syllabic writing system, proficiency in typing Korean characters could play a mediating role. Hence, in this study, mobile literacy and Korean typing skills were examined as two subconstructs of digital literacy.

In conclusion, previous L2 linguistic alignment research has presented mixed findings regarding the mediating effects of L2 proficiency and prior knowledge of target structures on linguistic alignment. Considering that only a small number of studies investigated the role of individual differences in L2 linguistic alignment effects, more alignment studies should examine less-commonly-taught languages and diverse learning contexts. Regarding alignment studies addressing text-chat in SCMC or SMMC contexts, investigating learners’ digital literacy as a modulating factor provides new insights into understanding linguistic alignment.

The current study

To address the research gaps discussed in the previous section, this study investigates the following research questions:

-

1. To what extent do source of alignment, Korean proficiency, prior knowledge of target features, mobile literacy, and Korean typing skills predict the occurrence of pragmatic alignment in Korean honorific request-making expressions during four group chat tasks?

-

2. To what extent do source of alignment, Korean proficiency, and prior knowledge of target features predict short-term and long-term alignment-driven learning of honorific request-making expressions in Korean?

Methods

Participants

The participants in this study were undergraduate students enrolled in Korean degree programs at four universities in the UK. A total of 87 students volunteered to participate in this study. The gender distribution was highly skewed (76 female, 9 male, 2 non-binary), and the mean age was 21.02 (SD = 3.01). While the participants’ first language (L1) backgrounds were diverse (e.g., Bulgarian, Cantonese, Croatian, Italian), the majority were native English speakers (n = 71). Their proficiency level was between beginner and intermediate, and we included Korean proficiency as one of the variables in the study. Participants (n = 86) also reported studying Korean for an average of 29.34 months, or approximately 2.4 years (SD = 22.52), with a range of 4 to 139 months. Moreover, most participants had never visited Korea (n = 72), while 12 had visited once, 1 had visited twice, and 2 had visited more than four times. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three experimental conditions: Prime (n = 28), Recast Prime (n = 30), or Control (n = 29).

Target feature: honorific request speech acts in Korean

The target feature is request speech acts in Korean that employ different degrees of politeness, linguistically signaled by honorific morphemes and indirectness. Although requests reflect social factors, that is, power (status) and distance (familiarity) (Blum-Kulka et al., Reference Blum-Kulka, House and Kasper1989; Brown & Levinson, Reference Brown and Levinson1987), request strategies differ cross-linguistically, especially between English and Korean (Sohn, Reference Sohn1986). The current study implemented Korean-specific expressions for honorific request speech acts based on Byon (Reference Byon2006). Request expressions comprise the request head act and the request supportive move.

Drawing from the request head acts from the L2 Korean discourse completion task (DCT) in Byon (Reference Byon2004, Reference Byon2006), the query-preparatory strategy (e.g., 저에게 그것을 빌려주실 수 있으세요? Ceeykey ku kesul pillyecwusil swu issuseyyo? “Would it be possible to lend it to me?”) was chosen because it is one of the most common request strategies used by Korean native speakers and Korean as a Foreign Language (KFL) learners (Byon, Reference Byon2004, Reference Byon2006). To make an appropriate honorific request form, the speaker applies the honorific suffix -(으)시- -(u)si- to both the auxiliary verb -어/아 주다 -e/a cwuta (‘to do something for someone else’s benefit’) and the auxiliary verb -ㄹ 수 있다 -ㄹ swu issta (‘can’). The auxiliary verb -어/아 주다 -e/a cwuta becomes -어/아 주시다 -e/a cwusita, and the auxiliary verb -ㄹ 수 있다 -ㄹ swu issta becomes -ㄹ 수 있으시다 -ㄹ swu issusita. Therefore, the query-preparatory form involves double honorific suffixation in a single phrase. Honorific markers involve not only a morphological process but also semantic and pragmatic considerations and thus they have been recognized as a challenging linguistic feature for Korean language learners (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kim and Kim2025).

Beyond the honorific head act, regarding the request supportive moves, three peripheral elements were chosen as target features: preparator, disarmer, and apology based on Byon (Reference Byon2004, p. 1685). The selection of target features was based on the frequency of strategies, suitability of expressions to the conversational context, and participants’ proficiency in Korean. These three external modifiers were equally distributed in primes. Additionally, the internal modifier 혹시 hoksi (perhaps) was included as a request support move, as it downplays the request’s force, thus adding indirectness to the statement. Table 1 summarizes the three elements of request-making expressions in Korean targeted in the current study.

Table 1. Target elements of honorific request-making speech acts

Note: HON = honorific; POL = politeness; CON = connective; NOM = nominal; MOD = modifier.

Materials

Background survey

The background survey included questions addressing learners’ demographic background, language background, motivation, and digital literacy. This study analyzed learners’ responses to two items measuring mobile literacy and Korean typing skills. Regarding mobile literacy, learners self-assessed their skills in using nine mobile features on a six-point Likert scale (1—Don’t know what this function is, 6—Very skillfully): 1) KakaoTalk messaging (https://www.kakaocorp.com/page/service/service/KakaoTalk; the most widely used instant messaging application in Korea), 2) dictionary, 3) email, 4) internet search, 5) phone call, 6) social media, 7) text message, 8) video-chat, and 9) editing photos. Each feature received an independent rating. Means and standard deviations for these variables are presented in Table 2. For Korean typing skills, learners self-assessed their proficiency in Korean typing on mobile phones using a six-point Likert scale (1—Very poor, 6—Very good).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of mobile literacy self-ratings skill levels (1–6): mean (SD)

Alignment tasks

The experimental treatment consisted of four scenario-based alignment tasks where learners engaged in group text-chats with two native Korean speakers (i.e., a total of three people in one chat room on mobile KakaoTalk application). One Korean speaker performed someone who is older and has a higher position than the participant (e.g., internship coordinator, international student office assistant, lecturer, homestay mother) and the other Korean speaker performed someone who is at the equal position as the participant (e.g., friend). As participants were required to study abroad in Korea as part of the degree program, scenarios selected for the tasks reflected situations commonly encountered during study abroad experiences in Korea (see Table 3).

Table 3. Scenarios in the four alignment tasks

While scenario topics remained consistent across groups, experimental conditions varied systematically. Table 4 presents sample text-chats for each condition, illustrating a prime-target pair for the prime group, recast prime followed by erroneous target for the recast prime group, and a target condition without prime for the control group. Model productions were provided by a native Korean speaker (line 1) prior to target productions, which participants were expected to produce using target features (line 3). Each scenario incorporated a total of five prime-target pairs for target honorific requests were incorporated during the tasks. For the recast prime group, recasts were provided by a native Korean speaker (line 7) when a participant’s utterances contained linguistic errors or inappropriate components related to the target features as well as any other non-target features (line 6). To avoid interrupting the flow of conversation, recasts followed a consistent discourse pattern. Specifically, after a participant made a request (line 6; requesting a recommendation letter), a Korean speaker acting as a peer indicated she also wished to make the same request (line 7; requesting a recommendation letter). Another Korean speaker responded to the request (line 8). While there was no immediate uptake opportunity during the conversation, learners’ primed production of the target feature shed light on the effects of recasts in subsequent productions.

Table 4. Sample text-chats for each condition

Note 1: R indicates a researcher. Note 2: ![]() is an emoji to refer to email.

is an emoji to refer to email.

The control group performed four alignment tasks based on the same scenarios; however, they received neither primes nor recast primes but produced the same total number of targets in obligatory contexts during the tasks (line 10). Table 4 illustrates one instance of target production for each condition, and each task included five different contexts requiring honorific request-making expressions (obligatory contexts). To ensure consistent obligatory contexts, although the tasks required open conversation, participants completed specified request-making acts following the task directions: e.g., Ask Ms. Lee if she can send some sample application forms; Ask Ms. Lee if she can correct any Korean grammar mistakes on your application form (full task materials can be found in IRIS).

Participants completed the four tasks in counterbalanced sequence to mitigate any task sequence effects, yielding a total of 20 obligatory contexts for target honorific request-making expressions. Across conditions and tasks, verbs and predicates (i.e., grammatical units that function similarly to adjectives in English) were not repeated (see Supplemental Materials A for the list of target verbs and adjectives). To provide authentic text-chat contexts, participants and the Korean native speakers could use emojis (e.g., ![]() ), voice memos, and images during the text-chat conversations. Additionally, other than the required prime-target pairs, they were encouraged to expand the text-chat contents.

), voice memos, and images during the text-chat conversations. Additionally, other than the required prime-target pairs, they were encouraged to expand the text-chat contents.

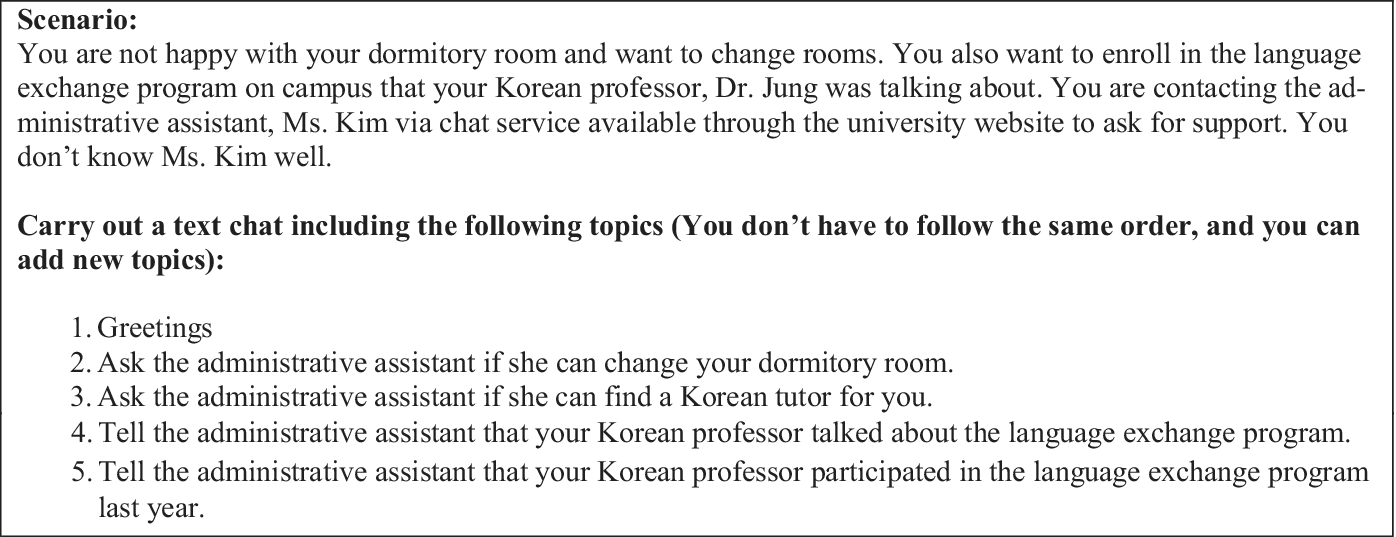

Production tests

Three production tests were developed and administered as pretest, immediate posttest, and delayed posttest, and were systematically counterbalanced to control for ordering effects. The production tests employed a DCT format, with each test comprising seven scenarios where participants exchanged texts with a native Korean speaker through mobile text-chat. Consistent with the alignment tasks, scenarios in the production tests reflected students’ future study abroad experiences. In one scenario, participants text-chatted with an administrative assistant to request a dormitory room change (see Figure 1 for a sample item). Of the seven scenarios, four elicited eight Korean honorific requests (two request situations per item), and three scenarios served as distractors requiring Korean non-honorifics (e.g., text-chat between close friends to give advice). Among the 24 verbs and predicates, six verbs and adjectives were identical to those used in the alignment tasks (see Supplemental Materials B for the list of target verbs and adjectives).

Figure 1. Sample production test item.

Korean proficiency test

Given the text-based nature of the interactions, reading comprehension constituted a critical component in language competence. Due to the established psychometric properties of the standardized Korean test, participants’ L2 Korean proficiency was measured by using the Test of Proficiency in Korean (TOPIK). Participants completed the reading section of TOPIK I, which consists of 40 multiple-choice questions, within one hour (https://www.topik.go.kr). Following standardized scoring guidelines, the total possible score was 100. The mean score was 65.83 (SD = 19.05), ranging from 18 to 100. A one-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences among the prime (M = 66.55, SD = 16.28), recast prime (M = 62.80, SD = 20.12), and control (M = 68.24, SD = 20.65) groups, indicating the three groups were homogenous in their Korean proficiency level (p = 0.54).

KakaoTalk application

Participants had the group chats via KakaoTalk, which is the most popular mobile messaging application in South Korea (https://www.kakaocorp.com). The KakaoTalk platform enables users to send and receive multimodal messages, including text, emoticons, photos, voice memos, and videos.

Procedure

Participants engaged in individual sessions with the researchers over six online sessions via Microsoft Teams. Each participant used both a mobile phone and laptop during data collection. During tasks and production tests, participants accessed KakaoTalk via mobile phones, while utilizing laptops for task worksheets. Throughout each session, participants screen-shared their mobile phone, with text-chat interactions being recorded. This allowed the research team to monitor participants’ use of other resources such as online translation tools.

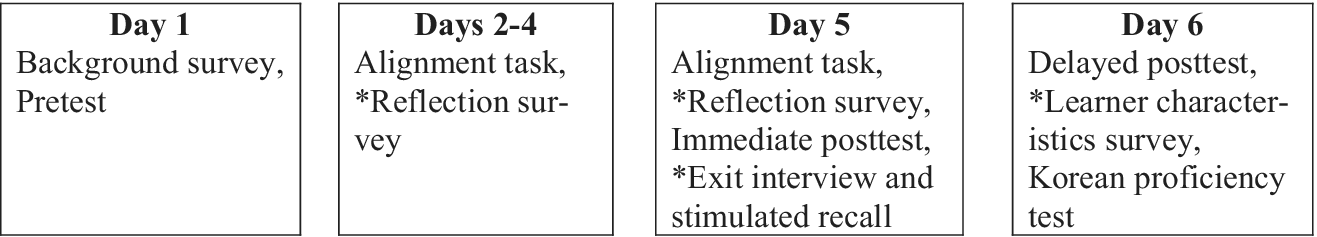

Following the research timeline presented in Figure 2, participants completed the background survey and pretest on Day 1. During Days 2, 3, and 4, each participant performed one alignment task with two native Korean-speaking researchers in a group of three. Prior to each task, participants received seven minutes of planning time to review material and consult the dictionary. Participants could reference words via online dictionaries during the task; however, translation tools were not allowed. Day 5 consisted of participants completing the final alignment task and reflection survey, followed by an immediate posttest, and an exit interview as well as stimulated recalls. The first five sessions (Days 1–5) occurred within a period of two weeks. The final session (Day 6), where participants completed a delayed posttest, learner characteristics survey, and Korean proficiency test, took place two weeks after Day 5. While a reflection survey, exit interview, and learner characteristics survey were conducted as shown in Figure 2, they were not included in the current study and therefore are not described in the Materials section.

Figure 2. The procedure of the current study.

Note: *The data from these measures were not included in the current study.

Data coding

For Research Question 1, we focused on learners’ production data during the four tasks. We analyzed the production of three request-making components for suppliance, following previous alignment research (e.g., Kim et al., Reference Kim, Jung and Skalicky2019; McDonough & Kim, Reference McDonough and Kim2009): honorific request head acts, external modifiers (request supportive moves), and internal modifiers (hedging). We operationalized pragmatic alignment as the production of honorific request-making expressions (pragmalinguistics) as we assumed that the production of pragmalinguistic forms could help us infer learners’ sociopragmatic knowledge (“knowledge of the social rules and norms that govern language use” (Roever, Reference Roever2021, p. 8).

To examine how different request-making expressions (honorific request head act, external modifier, and internal modifier) were aligned compared to each other in one statistical model, we used uniform coding: suppliance of the target form. Each request head act incorporated two auxiliary verbs (-어/아 주다-e/a cwuta, -ㄹ 수 있다 -ㄹ swu issta) conjugated with the mandatory honorific suffix (-(으)시 –(u)si). We first coded the suppliance of the two auxiliary verbs, respectively. For each target honorific head act, if students supplied at least one honorific suffix in the target request form, we coded it as 1 for suppliance and 0 for non-suppliance. This decision was made because one suffix adequately conveyed honorific meaning in the head acts, and this fulfills the suppliance of honorific head act expression. For external modifiers, if students produced one of the three forms, we coded it as 1 for suppliance. This criterion was applied for the internal modifier (1 for suppliance, 0 for non-suppliance) as well.

For Research Question 2, which addressed the learning of honorific request-making expressions, we used learners’ production data from the pre- and posttests. Specifically, as this was for examining the degree of learning, we examined the accuracy of the three target features in Korean request-making. For the honorific request head act involving two auxiliary verb conjugations, we used three coding options: (1) a score of 2 if both verbs were accurately conjugated; (2) a score of 1 if one verb was not accurately conjugated; and (3) a score of 0 if both verbs were not accurately conjugated. For the external and internal modifiers, a correct production of the target feature was given a score of 1 and an incorrect or absent production of the target feature was given a score of 0.

Approximately 20% of the treatment and pretest/posttest data were coded by two raters independently after several rounds of training while reassuring that the coding scheme is appropriate for the current data. The inter-rater reliability was calculated using the exact agreement percentage, and it was 99.09%.

The Korean proficiency test followed scoring guidelines accompanying the sample test, and the total possible score was 100. For digital literacy, as there were nine items assessing digital literacy, we ran a Principal Component Analysis and used the composite score. For the Korean typing skills test, as there was only one item assessing Korean typing skills, each participant’s Likert-scale rating was used for the statistical analyses.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed our data in R (version 4.2.2; R Core Team, 2022). Bayesian multilevel models were fit using the brms (version 2.18.0, Bürkner, Reference Bürkner2017) package. We opted to use Bayesian models for practicality—our exploratory modeling indicated that some combinations of group and target structures were close to reaching complete separation, meaning that certain combinations of variables nearly perfectly predicted primed production or accuracy. For example, the control group produced close to zero external modifiers across all four time points, leading to inflated odds ratios when comparing the other two groups against the control group. Following recent recommendations regarding such situations, we fit constrained priors on our effects using Bayesian multilevel models (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Blanchard, Hui, Tian and Woods2023) to specify penalized prior distributions for the predictor variables following a normal distribution with a standard deviation of 0.5.

For Research Question 1, we fit a logistic model with a binary outcome variable indicating whether the participant produced the target structure (honorific request head act, external modifier, or internal modifier) during the tasks. The model included interactions between groups (prime, recast prime, and control), structure (honorific request, external modifier, and internal modifier), text-chat task order (task 1–4), Korean L2 proficiency, pretest suppliance score, digital literacy, and Korean typing skills. Participants and items were entered as crossed random effects, with a random slope of text-chat task order for both participants and items.

For Research Question 2, which examined alignment-driven learning, participant accuracy for each structure on each test was fit as the dependent variable. Because this variable was zero-inflated, we implemented a hurdle lognormal model that combines two components: (1) a logistic prediction between a score of zero or not zero, and (2) a continuous prediction of scores above zero. A maximal model was defined with interactions among group, structure, test order (pre, immediate post, delayed post), Korean L2 proficiency, and total pretest suppliance score (the same structure was fit for both the logistic and continuous components of the hurdle model). Due to convergence problems, only participants were entered as random effects, with test order being fit as a random slope for participants.

All effects of interest were modeled using the emmeans package (version 1.10.0; Lenth, Reference Lenth2024). We subjected the prior distribution of each effect or contrast to a Region of Practical Equivalence (ROPE) test using the bayestestR package version 0.13.1 (Makowski et al., Reference Makowski, Ben-Shachar and Lüdecke2019). A ROPE test calculates the amount of overlap between the posterior distribution and a region centered around zero (containing zero or close enough to be equivalent). An effect is considered to be meaningful (or statistically significant) if a relatively high proportion of the 95% credible interval falls outside of the ROPE. We considered any ROPE value lower than 2.5% to be evidence of a significant effect. We used the rope_range() function to determine ROPE thresholds for each model.Footnote 1

Results

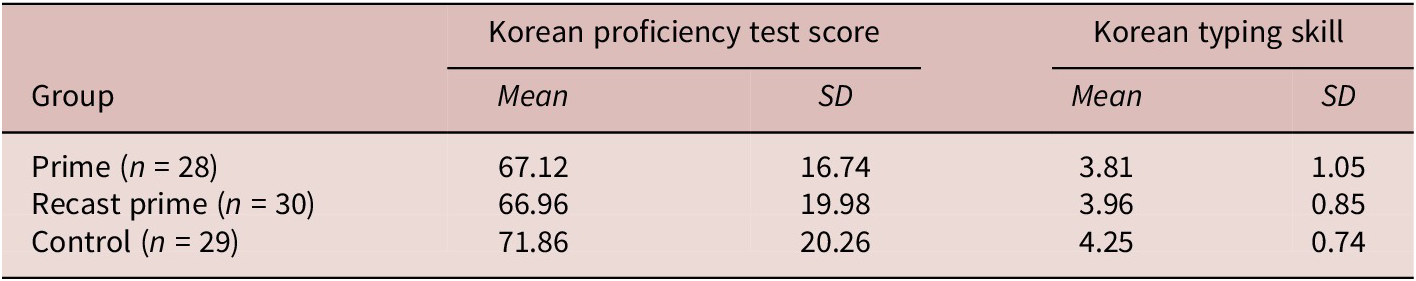

Prior to addressing the research questions, descriptive statistics for the variables in the current study are reported in Table 5 (pretest suppliance for the three structures) and Table 6 (Korean proficiency test scores, Korean typing skills rating). To assess learners’ prior knowledge, we analyzed suppliance scores on the production pretest. As can be seen in Table 5, very few responses on the pretest included the external modifier structures. All three groups produced a higher number of internal modifier or honorific request head act structures in their responses. The data revealed notable variation in the production of these structures, with participants in the Prime group producing fewer of these structures compared to the Recast Prime and Control groups.

Table 5. Frequency (%) and mean (SD) of suppliance for three target structures on the pretest

Note. Freq is the total number (and percentage) of structures produced by participants in each group. Percentage was calculated as the frequency of occurrence of target feature divided by the total number of targets elicited on pretest. Mean shows the average number of each target produced per person in each group.

Table 6. Mean and standard deviation of proficiency and Korean typing skills

Regarding the digital literacy variables (see the Materials section), nine of these variables were reduced into a single linear combination using principal component analysis, which explained 52.3% of the variance in a single factor solution. We considered Korean typing proficiency as a separate construct and retained it as its own independent variable. Table 6 displays the means and standard deviations of the Korean proficiency test scores (0–100) and Korean typing skills (0–6).

To ensure comparability of primes between the prime group and the recast prime group, we additionally analyzed the frequency of recasts provided to the recast prime group. As described in the previous section, all participants in the prime group received a total of five primes per task, totaling 20 primes. Participants in the recast group received an average of 19.13 recasts (SD = 1.83), indicating almost an equal number of primes were provided to both groups. As demonstrated in Table 4, because the researcher responded to the requests immediately, there was no opportunity to produce uptake during the immediate turn after each recast. However, the primed production, which addressed the first research question, shed light on the effects of recasts in the subsequent production of the target forms.

Research question 1: primed production

The first research question examines the production of target honorific request-making expressions during mobile group text-chat tasks, specifically analyzing the suppliance of these target request-making expressions. Table 7 presents the three groups’ production proportion scores for each target honorific expression (i.e., external modifiers, internal modifier, honorific request head act) during the four tasks.

Table 7. Descriptive statistics for request production proportion score during group chat tasks

Within-groups analysis

To show within-group analysis results, the median probabilities, 95% credible intervals, and ROPE overlap percentages of these effects are provided in Table 8 and visualized in Figure 3. The analysis of the posterior distributions indicated that participants in the control group had low probabilities of producing external modifiers and honorific request head act structures across all four text-chat sessions, all under 3% and with strong overlap with the ROPE (see Table 8). In contrast, probabilities ranging around 10% were seen for the internal modifier across all four chat sessions, with low ROPE overlap percentages, indicating a significant effect.

Table 8. Predicted probability of primed production per group and structure across text-chat sessions

Notes: Median represents probability of production; 95% HDI stands for 95% Highest Density Interval.

Figure 3. Posterior distribution of primed production for each group and target structure across four text-chat sessions (T1-T4).

Note: Yellow vertical bar represents the ROPE.

Posterior distributions for the prime group showed a significant probability of production for the internal modifier and honorific head acts during all four text-chat sessions. According to Table 8, these probabilities ranged from around 10 to 15% for the internal modifier and 33 to 70% for honorific head acts (all with 0% ROPE overlap). Notably, these probabilities increased for all structures as the number of task sessions increased, suggesting that production of these structures became more likely as participants completed more text-chat sessions. The analysis revealed no significant production effects for external modifiers.

The recast prime group showed a significant likelihood of production for all three structures. The analysis revealed a significant likelihood of producing external modifiers (around 14%), but only in the third and fourth chat sessions. The likelihood appeared higher for the internal modifier, ranging from 7 to 28%, but these effects proved significant only after the first text-chat session. The strongest effects emerged for honorific request head acts, with a 27% probability of production in the first text-chat session, increasing to over 90% in the third and fourth sessions.

These results offer evidence that the primed production task successfully elicited production of target structures among participants in the prime and recast prime groups. The strength of production also depended on the structure, with significant effects emerging for the recast prime group during later text-chat sessions. For the prime group, only honorific request head acts and internal modifiers showed more production as a result of alignment. Importantly, significant effects emerged in the control group’s production of the internal modifier, but these probabilities remained lower than those of both the prime and recast prime groups and remained stable over time. In contrast, the probabilities of production for the prime and recast prime groups increased over time, suggesting an effect of repeated text-chat sessions.

Between-groups analysis

For the between-group analysis results, the median probabilities, 95% credible intervals, and ROPE overlap percentages for these effects are shown in Table 9 and visualized in Figure 4. Comparisons of posterior distributions among the three groups indicated that for external modifiers, the recast prime group had a significantly higher production percentage (~13%) during the third and fourth text-chat sessions as compared to the control group. Otherwise, there were no significant differences between the prime and control groups or between the prime and recast prime groups for external modifiers. Regarding the internal modifier, there were no significant contrasts among any of the groups during any of the four text-chat sessions.

Table 9. Differences in primed production probability among group and structure during text-chat sessions

Notes: Median represents difference in probability of production.

Figure 4. Posterior distribution of differences in primed production among the three groups and target structures across text-chat sessions (T1–T4).

Note: Yellow vertical bar represents the ROPE.

Both the prime and recast prime groups had a significantly higher production percentage than the control group across all four text-chat sessions for honorific request head acts. For the prime group, these differences ranged from 32% in the first session to 68% in the fourth session, reflecting the general increase in production noted in Table 9. More pronounced differences were noted for the recast prime group, with a 26% difference in the first session increasing to almost 90% in the fourth session when compared to the control group. These contrasts further suggest that the significant probabilities reported in Table 8 for external modifiers and honorific head acts resulted from alignment, because these probabilities were significantly higher than those of the control group.

In addition to contrasts between the experimental and control groups, the recast prime group showed a significantly higher production of the honorific head act when compared to the prime group during the third (26%) and fourth (21%) text-chat sessions. This suggests that alignment effects in the recast prime condition for this structure were stronger than those in the prime condition. There were no other significant contrasts between the prime and recast prime groups.

These comparisons provide additional evidence that the experimental text-chat sessions led to significantly higher primed production for participants in the prime and recast prime groups. This effect was consistent for honorific request head acts across all four text-chat sessions, and the contrasts among all three groups suggest that alignment of this structure was strongest for the recast prime group. Significant contrasts for external modifiers were weaker and only emerged in later text-chat sessions for the recast prime group, further suggesting that these structures required more time before alignment became effective.

To illustrate how recast primes promote primed production during text-chat interactions, particularly in later tasks, we present below example text-chat interactions from Participant 60 (recast prime group) over two tasks.

Task 1

Task 2

Note: TOP = Topic; AC = Accusative; POL = Politeness; HON = Honorific; CON = Connective; LOC = Locative; PAST = Past tense; DAT = Dative; MOD = Modifier.

As this participant performed the group chat tasks, they showed improvement in the use of the honorific head act. In Task 1, the participant did not use any target request-making speech act elements in her earlier productions (line 2); instead, used a less polite and more direct request expression (보낼 수 있어요? ponayl swu isseyo?). Following the participant’s non-target-like production, Researcher 1 immediately provided recast feedback by asking the teacher (Researcher 2) a different request question using the same sentence structure with the correct honorific request head acts (line 3). As the participant was exposed to the recast primes during the group chats, she made an attempt to produce a more polite request head act by conjugating one of the target auxiliary verbs (-ㄹ 수 있다 -ㄹ swu issta) with an honorific suffix (i.e., from 있어요? (line 2) to 있으세요? (line 6-고칠 수 있으세요? kochil swu issuseyyo?)), but still omitted the other auxiliary verb (i.e., -어/아 주다 -e/a cwuta (to give)). The same pattern persisted in the participant’s early production during Task 2 (line 9-만들 수 있으세요? mantul swu issuseyyo?). However, later in Task 2, the participant exhibited progress in the use of honorific head acts for making a polite request. Both target auxiliary verbs (-어/아 주다 -e/a cwuta and -ㄹ 수 있다 -ㄹ swu issta) were used and conjugated correctly, as shown in line 13 (발급해 주실 수 있으세요? palkuphay cwusil swu issuseyyo?). Notably, while the participant showed improvement in the use of honorific head acts, she still did not use hedging or external modifiers despite receiving recast feedback during task performance.

Effects of prior knowledge of target features, L2 proficiency, mobile literacy, and Korean typing skills

Figure 5 displays the predicted effects of prior knowledge of target features (i.e., pretest suppliance scores), L2 proficiency, mobile literacy, and Korean typing skills on the probability of primed production during the different task sessions. The results indicated that the posterior distributions for mobile literacy, Korean typing skills, and L2 Korean proficiency showed substantial ROPE overlap for all groups and all four text-chat sessions, indicating that these variables did not significantly affect the production of the target structures. Significant effects emerged for pretest suppliance scores, but only for the recast prime and prime groups. For the recast prime group, increased pretest suppliance was associated with increased probabilities of producing the internal modifier during the second (Median = 0.138, 95% CI[0.055, 0.251], ROPE = 0.00%), third (Median = 0.150, 95% CI[0.061, 0.267], ROPE = 0.00%), and fourth (Median = 0.193, 95% CI[0.080, 0.328], ROPE = 0.00%) text-chat sessions. Similarly, higher pretest suppliance correlated with an increased probability of producing honorific request head acts for the prime group across all four text-chat sessions: first (Median = 0.164, 95% CI[0.032, 0.317], ROPE = 1.60%), second (Median = 0.186, 95% CI[0.037, 0.337], ROPE = 0.07%), third (Median = 0.176, 95% CI[0.036, 0.321], ROPE = 0.09%), and fourth (Median = 0.153, 95% CI[0.030, 0.295], ROPE = 1.80%).

Figure 5. Posterior distribution of effects of four covariates on primed production among the prime and recast prime groups across text-chat sessions (T1–T4) for each target structure.

Note: EM = External modifier, IM = Internal Modifier, HHA = Honorific request head act. Yellow vertical bar represents the ROPE.

To summarize the findings of the first research question, the results provided the evidence of primed production for two of the three target structures (external modifiers and honorific request head acts). The effects of external modifiers were observed exclusively for the recast prime group, and only during the latter two text-chat sessions. In contrast, the effects for honorific request head acts were observed for both the prime and recast prime groups across all four text-chat sessions. In all cases, the likelihood of production increased as the text-chat sessions progressed, suggesting a cumulative effect of repeated text-chat sessions. The analysis of the mobile literacy and proficiency variables indicated no significant effects for mobile literacy, Korean typing skills, or L2 Korean proficiency. The study found a significant, positive effect of pretest suppliance scores on primed production for the prime group on honorific request head acts, as well as for the recast prime group for the internal modifier. However, given that there were no overall significant priming effects for the internal modifier in the recast prime group, the current study provides limited evidence for the prior knowledge factor that was proposed in the current study.

Research question 2: production test accuracy

The second research question examines the learning of request-making expressions following group text-chats under three experimental conditions (prime, recast prime, and control). As described in the methods section, accuracy was scored using a scale of 0, 1, or 2. Table 10 presents the frequency of target items receiving each score across the three tests.

Table 10. Frequency of accuracy scores per group and test

Within-group accuracy growth

Analysis of the posterior distribution predicting accuracy growth indicated no significant differences among production tests for the control group across all three structures. In contrast, both the prime and recast prime groups exhibited significant gains on the immediate and delayed posttests compared to the pretest for the internal modifier and honorific head acts. For external modifiers, the recast prime group demonstrated significantly higher predicted accuracy on both the immediate and delayed posttests (vs. the pretest), and the prime group showed significantly higher accuracy on the delayed posttest (vs. the pretest). These results suggest immediate and delayed gains in accuracy for all structures among participants in both the prime and recast prime groups. The median predictions, 95% credible intervals, and ROPE overlap percentages for these contrasts are provided in Table 11 and visualized in Figure 6 (prime and recast prime groups only).

Table 11. Within-group pairwise comparisons of production test accuracy

Notes: Median represents predicted difference in accuracy score.

Figure 6. Posterior distribution of within-group comparisons for accuracy on production tests.

Note. Yellow shaded regions indicate the ROPE. For clarity of visualization, only the prime and recast prime groups are shown (control group had no significant differences).

Between-group differences in accuracy growth

For the between-group analysis results, the median predictions, 95% credible intervals, and ROPE overlap percentages of the contrasts are provided in Table 12 and visualized in Figure 7. Comparisons between groups for changes in accuracy indicated that the prime and recast prime groups had significantly higher accuracy from pretest to both the immediate and delayed posttests when compared to the control group for all three structures. The magnitude of these differences varied by structure and group. The largest differences emerged for honorific request head acts as compared to the other structures, and the gains for the recast prime group relative to the control group were higher than those for the prime group. There were no significant differences between the prime and recast prime groups across all three features.

Table 12. Between-group pairwise comparisons of production test accuracy

Notes: Median represents predicted difference in accuracy score.

Figure 7. Posterior distribution of between-group comparisons for accuracy on production tests.

Note: Yellow shaded regions indicate the ROPE.

Effects of L2 Korean proficiency and prior knowledge of request-making expressions

There were no significant effects for L2 Korean proficiency on production test accuracy across all combinations of group, test, and structure (all ROPE > 2.5%). Increases in pretest suppliance were associated with higher accuracy for the internal modifier on the pretest for both the prime (Median = 1.470, 95% CI[0.507, 3.374], ROPE = 0.00%) and control (Median = 2.127, 95% CI[1.015, 3.814], ROPE = 0.00%) groups, as well as for external modifiers on the immediate posttest for the prime group (Median = 1.743, 95% CI[0.323, 4.08], ROPE = 2.105%). While two of these effects were present on the pretest, the sole effect for the immediate posttest was small and near the threshold of significance. Therefore, there is very little evidence to suggest that L2 Korean proficiency or pretest suppliance scores influenced performance on the production tests.

To summarize the results of the second research question, both the recast prime and prime groups showed immediate as well as delayed learning effects for request-making expressions after completing the four group text-chat tasks across all three features. However, there were no significant differences between the recast prime and prime groups for any features. Additionally, the results indicated that both L2 proficiency and prior knowledge of the target features did not significantly mediate the role of alignment sources on the learning of request-making expressions across all features.

Discussion

Building on previous L2 alignment research, our goal was to expand its scope by examining three aspects: (1) three request speech act features (honorific request head act, external modifiers, and internal modifier), (2) source of alignment (i.e., prime vs. recast prime), and (3) occurrence of alignment in mobile group text-chat settings for learning Korean honorific request expressions. Results revealed that when participants engaged in text-chat conversations within groups of three, they demonstrated alignment in their use of honorific requests after exposure to these forms. Specifically, primes and recast primes were directed to another Korean native speaker, allowing participants to observe one Korean speaker communicating with another Korean speaker in the group interaction.

Dobao (Reference Dobao2014) revealed that pair work, the main context for previous alignment research, may offer more opportunities for individual learners to contribute to the conversation. However, regarding alignment for pragmatics, learners participating in group chats may benefit more than those in dialogic conversations, given their access to a larger pool of knowledge and resources and engagement in more diverse social interactions. When considering dialogue as a joint action (Garrod & Pickering, Reference Garrod and Pickering2009), promoting the learning of honorific request expressions through group chat tasks while facilitating interactive alignment shows considerable promise.

Learning pragmatics involves acquiring both sociopragmatics and pragmalinguistics (Taguchi & Roever, Reference Taguchi, Roever, Halenko and Wang2017), and our findings revealed that alignment occurred at the pragmatic level during group-chat tasks, enabling participants to produce developmentally challenging pragmalinguistic forms as a form of aligned production during group-chat tasks. However, the degree of alignment patterns in the two experimental conditions (prime and recast prime) differed depending on the target features and task repetition frequency. Specifically, honorific request head acts showed stronger alignment than internal and external modifiers. This heightened alignment may stem from head acts being the task-induced essential component of the speech act, making their saliency more prominent than external modifiers and the internal modifier during group text-chat communication (Kim & Taguchi, Reference Kim and Taguchi2015). The three external modifiers proved more linguistically challenging than the internal modifier (hedging, 혹시 hoksi [perhaps]), which is a conventional construction for making requests in Korean (Kim & Yoon, Reference Kim, Yoon and Cho2020), particularly in a polite way (Park, Reference Park2022). Consequently, learners likely found it easier to incorporate internal modifiers, having had more frequent exposure than to external modifiers. Moreover, the presence of three distinct forms of external modifiers during interaction might have contributed to reduced alignment among the prime group.

Regarding the source of alignment, both experimental groups successfully produced aligned production compared to the control condition. More specifically, providing primes in a recast form proved more effective than the simple prime condition, particularly for the honorific request head acts. For external modifiers, primed production (i.e., alignment) occurred significantly more frequently in the recast prime condition compared to the control condition. However, this pattern emerged only during the third and fourth tasks, suggesting that recast prime effects require a longer time and extended exposure to target forms. Since using honorific request head acts with proper honorific suffixes conveys respect to the interlocutor, learners appeared to consider additional supportive moves redundant or unnecessary.

We found notable differences in alignment effects between recast prime and prime conditions in terms of primed production. Long (Reference Long2007) states that “recasts convey needed information about the target language in context, when interlocutors share a joint attentional focus, and when the learner already has prior comprehension of at least part of the message, thereby facilitating form-function mapping” (p. 77). Our findings provided additional empirical evidence for Long’s claims, demonstrating that during group text-chats, participants who observed recasts provided to other Korean group members, rather than receiving them directly, still benefited from observing recasts for the subsequent production of target features (i.e., primed production). This finding aligns with Branigan et al. (Reference Branigan, Pickering, McLean and Cleland2007), whose results showed that participants (L1 English speakers) produced primed utterances even when they were side-participants in the previous interaction (i.e., being exposed to the target feature by observing interactions between two participants). These results extend our understanding of the alignment effects of group interaction among L2 learners.

While research on recasts has increased substantially over the last three decades (see Goo, Reference Goo2020, for a review), their impact on subsequent production (i.e., primed production) in the same conversation has not been systematically examined (cf. McDonough & Mackey, Reference McDonough and Mackey2006). Our study demonstrates that recasts could serve as a type of prime (McDonough & Mackey, Reference McDonough and Mackey2006) and enhance primed production more effectively than simple primes in the same conversation. The superior performance of recast primes suggests that receiving both positive evidence (prime and model examples) and negative evidence (understanding what is not possible in target language) better facilitates primed production than receiving models (positive evidence) alone during group chats. This finding supports the claim for the necessity of both positive and negative evidence in language development (Long, Reference Long, Ritchie and Bhatia1996; Oliver, Reference Oliver and Liontas2018). Furthermore, as Carpenter et al. (Reference Carpenter, Jeon, MacGregor and Mackey2006) argued, receiving recast primes may encourage learners to engage in “cognitive comparisons” between their original production and the recast primes provided by the researcher, representing “an important step that might help learners identify what they still need to learn and might, thus, lead to changes in their interlanguage toward more target-like usage” (p. 229). However, we found only marginal recast effects for external modifiers, while strong effects emerged only with honorific request head acts. This variation in effect strength appears to be related to the degree of students’ noticing of the target pragmalinguistic features.

Regarding learning outcomes, both the prime and recast prime groups outperformed the control group and showed significant gains between the pretest and posttests. Although the recast prime condition elicited more primed production of target features than the prime condition, neither group showed significant differences in learning outcomes for any of the three features. Previous research has documented recasts’ advantage over providing solely negative or positive evidence (Leeman, Reference Leeman2003), and our findings align with those presented in Leeman (Reference Leeman2003) and McDonough and Mackey (Reference McDonough and Mackey2006). More specifically, the current study adds further evidence for the positive role of offering recasts in learning speech acts (e.g., Fukuya & Hill, Reference Fukuya and Hill2006). Furthermore, our study demonstrates the effectiveness of alignment in L2 learning during mobile text-chats, though the source of alignment (recasts vs. primes) did not affect learners’ acquisition of honorific request-making speech acts. These results suggest that the benefits of positive evidence from primes and its combination with positive and negative evidence through recast primes yielded similar outcomes for learning pragmatics.

The study investigated several learner factors: L2 proficiency, prior knowledge of the target features, Korean typing skills, and mobile literacy. Similar to previous research (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Skalicky and Jung2020; McDonough & Fulga, Reference McDonough and Fulga2015), prior knowledge facilitated primed production, particularly for honorific head acts in the prime condition and internal modifiers in recast prime. However, neither prior knowledge of the target features nor L2 proficiency influenced alignment-driven learning. In the current study, L2 proficiency assessment utilized a standardized Korean proficiency test focusing on reading and vocabulary, which are critical for comprehending interlocutors’ chats during text-chat conversations. Our findings suggest that in pragmatics learning, as long as students could comprehend input from other group text-chat members, L2 reading and vocabulary-based proficiency did not seem to play a role. Neither Korean typing skills nor digital literacy emerged as significant factors. We collected self-reported data for these measures, suggesting a ceiling effect, with mean ratings consistently high (above 5 out of 6) across items. Despite hypothesizing that the unique spelling system of the Korean language would make typing skills play an important role, our results showed otherwise. This may be because the group text-chat tasks were not timed, allowing sufficient time for typing responses using the Korean keyboard. Additionally, students could choose between typing their utterances or sending voice messages, potentially explaining the lack of mediating effects of Korean typing skills.

Our findings yield important theoretical and pedagogical implications. This research broadens alignment literature by demonstrating alignment-assisted language learning in group text-chats for pragmatics. Results indicate that recast primes, which provide both negative and positive evidence, are more effective than prime conditions (positive evidence only) for eliciting alignment, as they enhance the salience of the target forms in meaning-oriented interactions. Although this study was not designed to promote immediate uptake (i.e., response to the recast), primed production could indirectly show learners’ noticing of recasts. The emergence of subsequent primed production many turns later and its increase during later tasks provide additional evidence for the benefits of recasts in later conversations. However, various pragmalinguistic forms exhibited varying degrees of primed production, and notably the effects of the recast prime condition appeared later than those of the prime condition. These findings highlight the potential benefits of alignment in L2 pragmatics learning.

Regarding pedagogical implications, our findings provide guidelines for designing mobile-assisted text-chat tasks for pragmatics learning. Students successfully produced and acquired complex sociopragmatics and pragmalinguistics forms without explicit instruction during meaning-focused group text-chat tasks. The combination of authentic communication contexts, which required learners to pay attention to the relationships among group text-chat members, alongside alignment opportunities, enhanced pragmatics learning.

Conclusion

This study advances current L2 alignment research by examining pragmatics in the Korean language, areas previously unexplored in this context. Furthermore, our investigation of alignment during mobile group chats among three people represents a novel context in alignment research. Given that pragmatics is critical for language use in social contexts and that language users typically adapt their language use to match group members, examining alignment during group chats captures authentic language use contexts.

Several limitations warrant consideration for future research. Our examination of only one speech act, honorific request-making, may limit the generalizability of these findings to other pragmatic features. As we introduce the concept of pragmatic alignment, future research should explore various pragmatic features. The influence of others’ language use on speakers’ choices during conversation suggests that the framework of alignment in pragmatics research offers significant potential. While this study focuses only on production knowledge, future research should assess receptive knowledge, as priming involves comprehending input. Additionally, our reliance on self-reported data for mobile literacy and Korean typing skills indicates the need for more fine-grained measures in future studies for these two constructs. In the current digital era, which generates diverse interactions, including those with AI-assisted chatbots, future alignment research should explore these emerging modes of interaction.

Acknowledgments

This research (or publication) was supported by the 2020 Korean Studies Grant Program of the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2020-R-79). We are grateful to Luke Plonsky, Andrea Révész, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Author contribution

YouJin Kim: conceptualization, data collection, data coding, manuscript writing, and manuscript revision; Yeji Han: data collection, data coding, manuscript writing, and manuscript revision; Sanghee Kang: data collection, data coding, and manuscript writing; Yoon Namkung: data collection, data coding, and manuscript writing; Stephen Skalicky: statistical analysis, manuscript writing, and manuscript revision; Hyejin Cho: data collection.