Domestic violence is a major public health issue: 20% of women from England and Wales report physical and sexual assault by a current or former partner; Reference Walby and Allen1 when financial and emotional abuse and threats of abuse are included, this increases to 25% of women. Two women are murdered by their partner or ex-partner every week in England and Wales Reference Walby and Allen1 and similar figures are reported internationally. One in seven men in the UK also report experiencing physical assault by a current/former partner, although these incidents are generally less serious than those reported by women. Reference Walby and Allen1 Domestic violence is associated with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, insomnia, alcohol and drug misuse, suicide attempts Reference Golding2 and exacerbation of psychotic symptoms. Reference Neria, Bromet, Carlson and Naz3 It is therefore not surprising that higher rates of domestic violence are experienced by mental health service users compared with the general population. Reference Howard, Trevillion, Khalifeh, Woodall, Agnew-Davies and Feder4 However, experiences of violence are underdetected in clinical settings and service users are reluctant to disclose such experiences in the absence of direct questioning. Reference Howard, Trevillion, Khalifeh, Woodall, Agnew-Davies and Feder4–Reference Rose, Peabody and Stratigeas6

There has been little research in mental health settings on the professional barriers to enquiry about, and service user barriers to disclosure of, domestic violence. There has however been more research into barriers to disclosure of childhood abuse experienced by mental health service users. These studies have identified lack of training and confidence, severity of psychological disturbance and fear of exacerbating disturbance and clinicians’ beliefs about the reliability of clients’ accounts as barriers to routine enquiry about childhood abuse; Reference Little and Hamby7–Reference Young, Read, Barker-Collo and Harrison11 these may also be relevant to enquiry about domestic violence. The aim of this study was to explore mental health service user and professional views on routine enquiry about domestic violence and to articulate facilitators and barriers to disclosure from both mental health service user and professional perspectives.

Method

This study was a cross-sectional semi-structured interview study. Two topic guides, developed specifically for the project, were used to focus the interview on service user and professional attitudes towards routine enquiry about domestic violence, their experiences of being asked/asking and discussing violence and their views on what interventions had been or would be helpful; the latter will be discussed in another publication. Following consultation with an expert reference group, consisting of qualitative researchers (including service user researchers) and senior mental health clinicians, the two draft topic guides (see online supplements DS1 and DS2) were piloted with three service user and four professional participants. Participants were interviewed individually by K.T. or A.W., who had received specialist training from D.R. on conducting interviews with this client group. Quality and consistency of interviews were checked by D.R. and L.H. Professionals and service users were told that domestic violence was defined as abuse by another person either psychologically, physically, sexually, financially or emotionally, within their home or relationships. Recruitment continued until saturation of themes had been achieved, i.e. no new themes were emerging from the data.

After piloting, the main interviews were carried out between May and December 2008 and were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Interviews lasted between 30 min to 1 h. The majority of interviews with service users were carried out in a private room within local community mental health team bases unless the participant explicitly stated concerns about the location. In these instances, after assessing the level of risk within the client's home or local community centre, if appropriate, interviews were conducted in these alternative locations. Service users were given £20 for their time and expenses.

Participants

Service users

Our inclusion criteria for the study were service users in contact with community mental health teams (CMHTs) or who had been in such contact and were now only in contact with the local mental health voluntary sector. Service users deemed by clinicians to be too unwell to enter the study were excluded. Participants were recruited in three ways: advertisements placed on notice boards in local south London community mental health centres; an advertisement in a local voluntary sector newsletter; and care coordinators (case managers with a background in nursing or social work) asked service users in routine appointments if they would be interested in participating. A purposive sample of service users was recruited to ensure diversity in age, ethnicity, diagnosis and experience (or not) of domestic violence. In this analysis of barriers and facilitators to disclosure, only service users who had experienced domestic violence are included (n = 18); 16 were female and 2 were male. Nine were White British, one was European and eight self-ascribed their ethnicity as Black Caribbean (n = 3), Black British (n = 1), Black African (n = 1), Asian (n = 1), Mixed Race (n = 1) and Latin American (n = 1). The ethnic background of the sample reflected that of the local population as a whole as identified in the 2001 census. 12 The mean age of the service users was 41 (range 19–59, s.d. = 8.7). The following diagnoses were identified: depression (n = 6), bipolar disorder (n = 5), schizophrenia (n = 2), schizoaffective disorder (n = 1), borderline personality disorder (n = 1), adjustment disorder (n = 1), substance use problems (n = 1) and not assigned (n = 1). In total, 12 participants reported having children. Two male and three female participants also reported perpetrating domestic violence. All other participants reported only experiencing domestic violence.

Mental health professionals

Our inclusion criteria were for mental healthcare professionals working in CMHTs in the same catchment area. A purposive sample of mental healthcare professionals was sought with respect to age, ethnicity and professional background from local CMHTs. In total, 20 professionals were recruited; 10 were female and 10 male. Five were psychiatrists, three dual diagnosis practitioners (with counselling (n = 2) and nursing (n = 1) backgrounds), one was a team manager (with a social work background), one a psychologist and ten were care coordinators (with social work (n = 2) and nursing (n = 8) backgrounds). The mean age of the professionals was 37 (range 27–58, s.d. = 6.9). The average number of years qualified was 11.9 (range 4–29, s.d. = 7).

Ethical approval

This study received ethical approval from the Joint South London and the Maudsley and the Institute of Psychiatry NHS Research Ethics Committee (ref 07/H0807/66).

Analysis

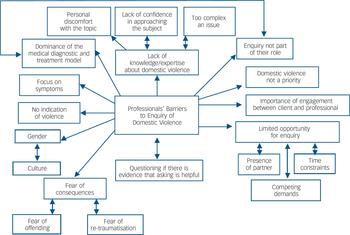

Interviews were analysed thematically. Reference Braun and Clarke13–Reference Attride-Sterling15 It was not assumed that themes would ‘emerge’ from the data but that interpretive work would be needed to identify them. The analysis began with identification of patterns in the data that were coded by two raters (A.W. and K.T.). An initial coding frame was developed by the two raters based on simultaneous coding of five service user and five professional transcripts and supplemented by codes taken from the interview schedule. The appropriateness of the coding frame was checked through progressive iterations and reapplied to earlier transcripts as it developed. In total, 20% of the coding was cross-checked to ensure reliability and 81% agreement attained by the two raters. Nvivo 8 (2008, QSR International Pty Ltd, www.qsrinternational.com) on MS Windows was used for indexing material and for retrieval of text chunks pertaining to the same or similar codes. Data that did not seem to fit into the coding frame were actively sought and multiple coding conducted by two raters. Reference Barbour16 Codes with similar information were merged and pruning of irrelevant codes and an initial identification of themes was conducted. Subsequently, these themes were themselves interrogated and a final level of abstraction was reached in the form of interpretive themes, with a complementary deviant case analysis where individual transcripts were interrogated for information that seemed to be discrepant with our overall analysis. At each step, it was ensured that saturation of themes had been reached. Concept maps were developed to represent the data in a visual format. The diagrammatic representations in the maps reflect the superordinate themes and subthemes that emerged from the data after repeated coding and refinement of the framework.

Results

Saturation of themes was obtained after recruitment of 18 service users and 20 mental healthcare professionals.

Dominant themes

The dominant themes from the interviews concerned disclosure of domestic violence. The two conceptual maps representing the two interpretive themes and their associated subthemes are given in Figs1 and2. For service users, the dominant theme was barriers to disclosure of domestic violence. For professionals the dominant interpretive theme was barriers to enquiry about domestic violence. The presentation of results will be given in the following order: themes from the data supplied by service users; themes arising from the interviews with professionals; and themes which overlap between the two groups.

Service users

As can be seen from the conceptual map (Fig. 1), fear is an important and multifaceted subtheme for service users when considering disclosure of domestic violence to mental health professionals. It encompasses fear of Social Services involvement; fear that disclosure will not be believed; fear that disclosure will result in further violence; fear of disruption to family life; and fear of the consequences for immigration status. Some illustrative quotes follow.

‘You're a bit scared to tell anyone in case you lose; I lost two children.’ (SU1, female)

‘You're living in fear until people believe you. You're left feeling dirty and like you've been let down again by the system, cause there is a lack of support and lack of people believing you.’ (SU22, female)

‘They're more scared of their boyfriend or husband, if they ever found out that you have been speaking about them… because otherwise that could cause…more domestic violence.’ (SU3, female)

A further cluster of subthemes concerns blaming attitudes of others, self-blame, and shame and embarrassment, which again makes victims reluctant to disclose abuse.

Fig. 1 Service users’ barriers to disclosure of domestic violence.

‘My mother said to me “well you're an idiot, you asked for it because you put up with it”. There's always that victim blame “oh she must be weak to put up with it, why did she let it happen?”’ (SU14, female)

‘You really feel it's you. The more they hit you… you convince yourself that it's you… I convinced myself “well look, this is the third violent relationship I've had, it can't be them it must be me, it must be something I'm doing wrong”.’ (SU23, female)

‘I was feeling a bit embarrassed because something like that had happened to me.’ (SU5, female)

Unsurprisingly, this was linked to psychological distress.

‘They were asking me if I was ok, if anybody was harassing me or if I was being stalked but by then things were getting out of hand and I didn't even know who to trust or who to talk to. So I was, kind of like, locked up everything inside me.’ (SU5, female)

A further cluster of subthemes concerned not recognising the behaviours as abusive.

‘The same with the domestic violence…the way that they work[the abuser] is that they, you're not supposed to know you're being abused… one of the things about domestic violence is that you don't realise…you're being abused until you're way down the line.’ (SU21, female)

‘If you haven't got a straight thing in your mind “no this is wrong and this shouldn't be happening” and “no you're not going to allow that man to do that to you”, that's what I lacked… I suppose you just think it's normal sometimes.’ (SU17, female)

Service users talked about perpetrators’ actions to prevent disclosure and about how this could isolate them from friends and family as the perpetrator did not want them to know about the abuse.

‘I was taken to the GP. I'd initially gone in to see the GP on my own and he burst in to her office and started telling her “oh she's taken overdoses, she's done this, she's done that”.’ (SU10, female)

‘I've been isolated from family and friends… I'd make friends with people and then he'd [the abuser] phone them up and tell them not to call this number again.’ (SU16, female)

Service users were critical of services’ failure to respond to signs of abuse and on the other hand they stressed the importance of engagement between professionals and service users if disclosure was going to be possible. This theme emerged in the professional data as well and is dealt with below.

Mental health professionals

As with service users, the interpretive theme that emerged was also disclosure, with an emphasis on barriers to asking clients about any abuse that they have experienced (Fig. 2). The dominant subthemes in this data are clear and are to do with whether enquiry about domestic violence is part of their role and within their competence.

The issue of professional roles is often linked to a medical diagnostic and treatment model in the sense that the professionals sought to focus on mental health symptoms.

‘It's not in my list of things that I now have to cover… I suppose my first response to that is, should we be addressing this? Because I think so many things are coming under the role of psychiatry to sort out when actually they are not mental health problems… suppose I struggle a bit with us taking on things that aren't mental health problems… perhaps we should be directing people elsewhere.’ (P20, female, psychiatrist)

In the following quote, a psychologist states that enquiry about domestic violence is not part of their role.

‘On the whole it is not seen as the remit of a community mental health team to be dealing with domestic violence unless there's diagnostic mental health problems as well.’ (P17, female, psychologist)

A contrasting view is described in the quote below from a consultant psychiatrist.

‘Another aspect is they might not see it as their role but, you know, we take a broader view that our role is to help people live healthier lifestyles.’ (P12, male, psychiatrist)

Competing demands, time constraints and the presence of the partner at consultations were all also mentioned as hindering enquiry into domestic abuse in a client's life. Many professionals talked about the importance of competency, and training, which many felt they had not received, as well as the boundaries of their role.

‘The staff member has to be suitably trained and competent to sort of engage in that kind of work. They have to be reminded that it is an important area to look out for.’ (P12, male, psychiatrist)

‘There is a real lack of information or knowledge and of course we don't know anything about housing rights or whatever… and if they are already distressed and whatever it's really difficult.’ (P3, female, care coordinator, nursing background)

However one professional, a team manager, felt that colleagues in the team did have the expertise to identify domestic violence.

Fig. 2 Professionals’ barriers to enquiry of domestic violence.

‘I think the team here are an experienced group… we spend lengthy periods of time working with people… and encompass a kind of holistic approach, when people would generally be picking up on those signs as professionals…so, I mean it would come up I think, in part of the conversation.’ (P19, male, team manager, social work background)

Linked to competency, many staff expressed unease and lack of confidence in dealing with a client's experience of domestic abuse.

‘People are hesitant because they don't feel confident, they don't feel it's their job; they think that somebody else is better equipped to do it.’ (P12, male, psychiatrist)

‘Personally, I think it is something that's quite sensitive; I wouldn't feel comfortable in asking it.’ (P4, male, care coordinator, nursing background)

However, a small number of experienced staff, who had been qualified between 11 and 29 years, described feeling confident in approaching the subject of domestic violence.

‘I am particularly clued up to look in at bumps and scratches and injuries…I would obviously be aware of people who were rowing in front of me… I would be inclined to ask one or other of them as to whether or not, you know, how safe or unsafe they felt with each other.’ (P5, male, care coordinator, social work background)

Further analysis showed that six professionals stated they did enquire about domestic violence on occasion; this was not associated with gender, age, professional background or years qualified. However, these six professionals appeared to differ in their ‘interpretation of their roles’, compared with other professionals.

However, for some professionals, routine enquiry in relation to perpetration of violence was felt to be an easier subject to address with clients than enquiry about the experience of violence.

‘It's easier to ask that question… cause you can wrap it up in various different ways… “your anger, your irritability are symptoms of a particular aspect of mental disorder”, so yeah that's very easy… “have you been violent or intimidating to another person?” If ticked yes then you can explore it.’ (P4, male, care coordinator, nursing background)

Although less evident than in the service user interviews, there was also a cluster of subthemes on the issue of fear. Professionals were worried that clients would be offended if they asked about domestic abuse, that there might be consequences for the victim or that discussing the experience might be traumatising for the client.

‘I don't know at what point you turn around and say “have you been a victim of domestic violence?” I think it has the potential to scare some people off.’ (P4, male, care coordinator, nursing background)

‘I think the disadvantages could be, and perhaps it's just a myth, is that it would kind of open up a can of worms and create perhaps re-traumatisation for the client to, you know, delve into those memories.’ (P14, male, dual diagnosis practitioner)

Professionals, like the service users, also identified factors that could facilitate discussion of domestic violence, including the importance of therapeutic engagement and a supportive relationship.

Overlapping themes between service users and professionals

It has already been seen that the issue of fear is common to service users and professionals although in different ways. A further common theme concerns therapeutic engagement. Both service users and professionals believed that a good and supportive relationship between them and their clients facilitated disclosure and the exploration of domestic abuse.

‘Some people might not even be able to talk about it but if their social worker is asking them, asking them in a nice way, in a gentle way… making sure that there is good contact between them, one day they will open and say “look this is happening to me”.’ (SU5, female)

‘Professionals need to make I suppose a comfortable environment or build up a close enough relationship where the patient actually feels safe enough to actually tell what's going on.’ (P13, male, dual diagnosis practitioner)

Therapeutic engagement is generally conceptualised as something developed over time but there was an example of a service user immediately ‘hitting it off’ with a worker.

‘I was having counselling… I did discuss certain things but it's not in detail like when I've actually told [care coordinator]… [care coordinator] must have been about the only person who has really got a lot out of me… he's got like five pages in like the short time that I met him.’ (SU11, female)

We have already seen that some professionals queried whether asking about domestic abuse was part of their role. They saw themselves as dealing primarily with the client's mental health problems and ensuring stability. Both service users and professionals talk about the influence of the ‘medical diagnostic and treatment model’ on willingness to disclose or ask about domestic violence.

‘They're more interested in your symptoms, your mental health problems… they don't look into your personal life and I think sometimes they need to do that.’ (SU16, female)

‘It would either be “well here's an antidepressant to help you get through.”.… “here's a tablet to help you sleep. Try eating better”, you know, there was never any talking about it.’ (SU3, female)

‘All the time people were concentrating more on her mental health, obviously she was depressed and everything, but they never ever focused on the things that led her into that situation.’ (P10, female, care coordinator, nursing background)

Issues of gender were evident in the interviews of both service users and professionals. The following male member of staff made his ‘excuses’ on the grounds of lack of gender matching.

‘I've felt very uncomfortable particularly if it's women, obviously, in knowing “how do I address this?”… I've used my excuses and said “perhaps you need to be assessed by a female member of staff”.’ (P4, male, care coordinator, nursing background)

In the following response, issues of both gender and culture appear.

‘It would be very difficult to ask men… I think women would experience it probably as quite a caring question… there are so many different cultures of patients…to ask some of the men from some of the cultures, that would be virtually impossible.’ (P20, male, dual diagnosis practitioner)

Culture appeared as a strong theme in both service user and professional interviews.

‘A lot of Muslim Asians may be getting abused in certain ways but they're not going to tell you and you're not going to see that because it's against their religion. Even in a West Indian culture it's a similar thing, Jamaican culture, you know, their men are meant to be superior to the women.’ (SU11, female)

‘I come from the north of England and I can remember in my teens being told “well there's nothing wrong in giving your wife a slap if she's not doing what she's told”… we're not always aware of what level of acceptance exists between different cultures, and more and more in Britain, and particularly in London, you get so many different cultures that its hard to know.’ (P2, female, care coordinator, nursing background)

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first study to look at the views of both service users and mental health professionals in relation to disclosure of domestic violence. Our main findings were that service users were reluctant to disclose domestic violence because of their concerns about the potential consequences, and mental health professionals reported finding enquiry about domestic violence difficult because of their lack of knowledge and expertise in this area or because they did not think it was part of their role.

For service users an important barrier to disclosure was fear evoked by a number of factors. Men and women were afraid of the potential consequences of disclosure of domestic violence to mental health professionals and other professionals such as general practitioners, other doctors, the police or social workers. Women feared that if they disclosed to health professionals the perpetrator might come to know this and they could be at increased risk of violence or their children would be removed from them. Non-disclosure can therefore be a very rational decision based on the service user's knowledge of the risks and benefits of disclosure. These findings are similar to those reported by service users in other healthcare and non-healthcare settings. Reference Feder, Hutson, Ramsay and Taket17 Service users also feared that they would not be believed if they disclosed domestic abuse because professionals would focus solely on their symptoms. One professional instead expressed concern that her seniors assumed that the client was not ‘telling the truth’. There is, however, evidence that psychiatric patients tend to underreport rather than overreport experiences of violence. Reference Goodman, Thompson, Weinfurt, Corl, Acker and Mueser18 It is common in situations of domestic abuse Reference O'Neill and Kerig19 for women to believe that the abuse must somehow be their fault and we found this in some of our interviews. Self-blame is exacerbated when the victim has a mental health problem as she may see this as part of her own involvement in provoking the abuse.

The main themes for professionals concerned role boundaries, competency and confidence. Professionals queried whether enquiry about domestic abuse was part of their role at all, as an assessment should focus on mental health. One psychiatrist expressed exasperation that so many recommendations were made by different stakeholders that they could not possibly all be accommodated. It is noteworthy that the team manager's view of staff competence in dealing with domestic abuse was in direct contrast to the staff themselves, who expressed a lack of expertise in addressing the topic of domestic violence and called for more training. Quantitative research involving a survey of US clinicians to identify barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in people with severe mental illness, found that these issues of competence and confidence were associated with the percentage of clients with whom trauma and PTSD had been discussed, documented and addressed directly in treatment; Reference Salyers, Evans, Bond and Meyer20 lack of confidence and competence inevitably has implications for the ability of clinicians to address domestic violence. Finally, professionals talked about this being a ‘delicate’ issue with which they felt uncomfortable. Generally, the barriers to enquiry highlighted by the community mental health professionals in this study were similar to those reported in a systematic review of studies of barriers to screening for domestic violence in other healthcare settings: lack of training regarding domestic violence, lack of time, lack of effective interventions and patient-related factors such as non-disclosure and fear of offending the individual. Reference Waalen, Goodwin, Spitz, Petersen and Saltzman21

Service users and professionals expressed similar ideas about facilitators of disclosure. Both believed that a supportive and therapeutic relationship was necessary for enquiry and disclosure so that the issue could be explored further. This has also been stressed by women interviewed in primary care qualitative studies on domestic violence Reference Feder, Ramsay, Dunne, Rose, Arsene and Norman22 and is clearly an important component of effective enquiry in clinical practice. However, research in mental health settings employing standardised screening tools to measure domestic violence suggest the experience of being asked about domestic violence may be sufficient to facilitate disclosure, despite not having an established relationship with the interviewer. Reference Howard, Trevillion, Khalifeh, Woodall, Agnew-Davies and Feder4 Some service users and some professionals believed that the ‘medical diagnostic and treatment model’ was an obstacle to discussion of domestic abuse as the focus was always on symptoms. Gender and culture were subthemes in both sets of interviews, with particular emphasis on the perception that some cultures believed domestic abuse to be acceptable.

One professional made the point that professionals were used to asking people whether they had ever been violent or had a propensity to violence as this is a routine part of a mental health risk assessment but felt that professionals were less comfortable enquiring whether a client had been a victim of violence. The emphasis on the risk of violence by people with severe mental illness rather than on their (higher) risk of experiencing violence appears to be related to the stigma of mental illness, which, it has been suggested, has ‘turned the world on its head’. Reference Eisenberg23 Mental health service users are 11 times more likely to have experienced recent violence than the general population Reference Teplin, McClelland, Abram and Weiner24 and we therefore recommend that risk management should focus more on the risk of experiencing violence. It appears that at present professionals may not routinely enquire about such experiences. In this paper, we have reported some of the barriers and facilitators to enquiry and we are using this data to inform the development of interventions in mental health services to address domestic violence.

Limitations

This study was carried out in a very socioeconomically deprived setting where there is a high proportion of people from Black and minority ethnic groups; our results may not therefore be generalisable to other settings. As with other research, selection bias means the views of those who did not wish to participate in the study are not known and may be different.

Clinical implications

Disclosure of domestic violence is facilitated by a good service user–professional relationship and is likely to be facilitated further by domestic violence training of professionals. Training interventions in healthcare settings can improve identification and specialist referral of people experiencing domestic violence. Reference Ramsay, Feder and Rivas25 A recent UK Department of Health initiative (the Victims of Violence and Abuse Prevention Programme, VVAPP) plans to increase training on abuse throughout mental health services and recommends that all service users are asked about violence and abuse as part of routine assessments. Reference Itzin, Bailey and Bentovim26 However, the focus of the VVAPP is on training to address childhood sexual abuse. Current domestic violence may be more strongly associated with mental health symptoms than childhood sexual abuse Reference Coid, Petruckevitch, Wai-Shan, Richardson, Moorey and Feder27 and will need different interventions if the violence is still occurring.

Training needs to address the deficits in knowledge identified in this study and include practical examples of how to ask about domestic violence, information on the needs of service users and details of local domestic violence support services. The current evidence base for interventions to support mental health service users experiencing domestic violence remains sparse. Reference Howard, Trevillion, Khalifeh, Woodall, Agnew-Davies and Feder4 It is necessary therefore to develop and evaluate clear care pathways, involving the domestic violence sector when appropriate, to help mental health services address this underdetected but potentially life-threatening issue.

Funding

This paper reports independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme. The views expressed by the authors are not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.