Introduction

Do historical disputes between South Korea (Republic of Korea, hereafter Korea) and Japan generate political effects in domestic politics? Despite the fact that Korea and Japan maintain close and cooperative economic and foreign policy relations, there are high levels of mutual animosity and emotional confrontation between these two states.Footnote 1 Most of this animosity or anger on both sides originates from historical disputes, including mutual territorial claims over the Dokdo/Takeshima Islands (hereafter Dokdo).Footnote 2 For instance, according to surveys conducted in 2014, 59.7 percent of Japanese respondents expressed negative views of Korea, while only 14.3 percent showed positive views of Korea (Kang Reference Kang2015).Footnote 3 Similarly, 79 percent of Korean respondents expressed their negative views of Japan. Rising nationalism in Japan and Korea alike also feeds the countries’ negative sentiments toward each other and aggravates bilateral relations.

What roles do the historical disputes between Korea and Japan and the associated emotional tensions play in Korean domestic politics? According to the rally-round-the-flag effect theory, external crises, especially territorial disputes with other states, can easily stimulate nationalist sentiments among citizens, increase internal solidarity around leaders, and hence positively affect political leaders’ popularity. Since colonial legacies and their shadows loom especially large in Korea, such rally effects of historical disputes with Japan seem likely in Korea. Yet, virtually no empirical studies have examined how historical disputes and associated animosity affect Korean domestic politics.

Our findings show that Korean presidents are likely to enjoy higher levels of popularity when they engage in historical disputes with Japan, as demonstrated by higher public opinion poll ratings. We first examine historical disputes in Korean-Japanese relations. Next, we outline the rally-round-the-flag effect theory and explore how bilateral historical disputes can generate rally effects in Korea, providing some illustrations of rally effects. We then discuss our research design, the data, and variables used in this article, as well as the empirical results and our thoughts on them. Finally, we conclude with a summary of the findings and their implications.

Korea-Japan Historical Disputes

The level of animosity between Korea and Japan can be attributed to historical experiences and the colonizer-colonized state relations that occurred between 1910 and 1945. Numerous issues are disputed between the two neighboring states, many of which are related to the debate about whether Japan has provided sufficient acknowledgement and apologies for atrocities experienced in Korea during its colonial occupation. Specific disputed issues include Japanese textbooks that either avoid or minimize Japan's treatment of Koreans during the colonial period; the unresolved issue of the Japanese military's use of Korean “comfort women” during that time; visits by Japanese prime ministers and other high-ranking officials to the Yasukuni Shrine, where Japanese war criminals are memorialized; and, most visibly, the dispute over ownership of the Dokdo Islands. All of these issues are generally bundled together as related factors that negatively influence Korea's bilateral relations with Japan. Of these disputed issues, the islands are “perhaps most notable” (Kang, Leheny, and Cha Reference Kang, Leheny and Cha2013, 234), and they cannot be treated outside of the context of the other historic disputes. In essence, Japan's claim of the islands acted as “the proverbial straw that broke the camel's back,” which “ignited deeply ingrained collective memory of past injustice” (Khalil Reference Khalil2012, 337). Therefore, since all the historic disputes are perceived as interrelated, it is almost impossible to discuss Japan's claim on Dokdo without referring to accusations of past Japanese atrocities. An example of this is the rallies about Dokdo hosted by civic groups that are held on dates commemorating Korea's resistance and independence from Japanese colonization (Wiegand Reference Wiegand2015).

The combined historical disputes resulting from colonial legacies remain a sharp thorn in Korean-Japanese relations. Due to colonial legacies and unresolved historical issues, including mutual claims of sovereignty over Dokdo and apologies and compensation to comfort women, the level of emotional animosity or anger toward Japan is relatively high in Korea. Since the territorial dispute over Dokdo is one of the most salient and most visible disputed issues in their relations, we focus on this issue in our analysis of rally effects. Disputes over territory that can be easily connected to military confrontations are very likely stir patriotic sentiments, mobilize people under national flags, and hence positively affect the popularity of political leaders. In addition, in comparison to other historical disputes, the Japanese government has maintained a very firm position on the Dokdo issue, continuously claiming its sovereignty over the islands.

The Dokdo Islands dispute began in January 1952, when the Japanese government lodged a protest against the Korean proclamation of the “Peace Line,” which claimed Korean sovereignty over much of the East Sea, including the waters surrounding the islands. Korea has maintained effective control and occupation of the islets since 1954, with the presence of coast guard units based on the islands. Japan's claim for the islands is mainly based on the claim of terra nullius dating from 1905, when the Japanese government incorporated them into Shimane Prefecture. This lasted until the Japanese occupation of Korea ended in 1945 (Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke2007). One reason why the dispute over Dokdo became salient and not easily resolvable in Korea-Japan relations is the San Francisco Treaty of 1952. According to diplomatic documents, the United States rejected Korea's request to add Dokdo to the territories to be renounced by Japan in the process of drafting the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Based on the documents, Japan argues that Korea's claim over the islands is invalid. Korea's position on the dispute is that “no territorial dispute exists regarding Dokdo and Dokdo is not a matter to be dealt with through diplomatic negotiations or judicial settlement,” and the government “exercises Korea's irrefutable territorial sovereignty over Dokdo” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade 2012, n.p.). This position is based on the historic evidence of ownership dating to 512 CE.

For much of Korean society, “Dokdo is not simply an easternmost island. It is a Korean national symbol and a reminder of Japan's past aggression” (Choi Reference Choi2005, 471). Because of strong domestic mobilization, the islands have gained significant nationalist and symbolic value among Koreans. The symbolism associated with Dokdo is particularly powerful because the islands were the first Korean territory Japan annexed in 1905 during the Russo-Japanese War. As observers of the dispute note about Dokdo, “to try to understand South Korea-Japan relations by focusing on the dynamics of the contemporary relationship is to get things upside-down.… [F]rom the South Korean perspective, the dispute over these rocky outcrops is the big picture” (Park and Chubb Reference Park and Chubb2011).

For instance, in 2005, when Japan's Shimane Prefecture announced a “Takeshima Day,” which unilaterally claimed and celebrated that Takeshima (Dokdo) belonged under the jurisdiction of Shimane Prefecture starting in 1905, it prompted strong protests from Korea. In April 2006, in response to the dispatch of Japanese research vessels to the Dokdo area, Korea dispatched twenty gunboats to the area. In 2008, Korea withdrew its ambassador to Japan when the Tokyo government ordered textbook publishers to assert Japanese ownership of the islands (Koo Reference Koo2010). President Lee Myung-bak visited Dokdo in 2012, making him the first Korean president to pay a visit to the islands. Nevertheless, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirms that its position on the islands is inalterable, and members of the ruling party have attended the celebration of Takeshima Day since 2011, followed later by Japanese cabinet members.

Given continuous tensions regarding the islands, other historical issues, and rising nationalism, it is not hard to observe that historical disputes impede bilateral relations between Korea and Japan. For example, although both governments engaged in talks about signing an agreement for mutual security information sharing in 2012, they could not finalize the agreement due to public opposition (Wiegand Reference Wiegand2015).Footnote 4 Similarly, when both governments signed a joint fisheries agreement that established a compromise joint-use fishing zone around Dokdo in 1998, the Seoul government faced serious political backlash from the public.

High levels of emotional tension arising from external historical disputes can easily penetrate citizens’ minds and hearts. In particular, the Dokdo dispute stands out in antagonistic Korea-Japan relations as being a highly salient issue for the people of Korea, and public opinion polls in recent years demonstrate that the Dokdo dispute remains a significant impediment to relations with Japan (Asan Institute for Policy Studies 2016). In fact, “it would not be an exaggeration to say that matters concerning the past history involving the two countries and the Dokdo issue are ‘minefields’ for bilateral relations” (Gong Reference Gong and Dae-song2008, 378).

The issue is so sensitive that “the combination of Korean anger over colonial legacies, territorial conflicts, and multiple unresolved bi-lateral and regional issues, many of them legacies of Cold War/hot war conflicts, assures that the matter will continue to be contentious.… [F]or Koreans, the seizure of Dokdo is inseparable from the subjugation and humiliation of the nation at the hands of Japan, a trauma that remains vivid to this day” (Selden Reference Selden2011, 1). The Dokdo Islands serve as a representation of Korea's frustration with Japan's continuing lack of recognition, apology, and ultimately compensation for its actions during the colonial and wartime occupation. As such, it is clear that the Dokdo Islands remain salient to many Koreans: “Dokdo occupies a prominent place in the collective heart of the Korean nation; a maritime sacred cow, if you will” (Launius Reference Launius and Park2009, 178). In fact, as recently as 2015, polling of Korean citizens found that 83 percent of respondents thought that Korea's relationship with Japan had worsened, and as noted earlier, 79 percent of respondents expressed negative views of Japan. With such high numbers, it is not surprising that Korean-Japanese relations impact domestic politics. In this regard, it is important to understand how external historical disputes between Korea and Japan affect political leadership and domestic policies.

Rally Effects of Historical Disputes

The rally-round-the-flag effect theory posits that external crises, especially territorial disputes, have a strong positive impact on political leadership and its popularity (Mueller Reference Mueller1970, Reference Mueller1973). This is because external threats or crises stimulate national pride and increase internal solidarity around political leadership. Especially when the opinion leaders and the media are in favor of political leaders and their international policies, the public is likely to rally around their political leadership (Brody Reference Brody1991; Kam and Ramos Reference Kam and Ramos2008). According to this theory, intended or not, political leaders in Korea and/or Japan may enjoy the rally effects and a boost in short-run support of the leadership as a consequence of bilateral historical disputes.

Governments involved in territorial disputes with nationalist or symbolic value in particular are able to mobilize the public around the dispute. Symbolic, nationalist value that is attributed to disputed territory is often based on longstanding historical antagonisms, such as the historical disputes between Korea and Japan. Sometimes when leaders are domestically vulnerable due to low public opinion, they will take advantage of nationalist sentiment by prioritizing the defense of disputed territory or promising to right an injustice that will result in a shift of territorial ownership (Downs and Saunders Reference Downs and Saunders1996; James, Park, and Choi Reference James, Park and Choi2006; Wiegand Reference Wiegand2011). Korean leaders regularly defend the ownership of the islands and make promises to Koreans that Korea will not compromise, drop its ownership of the disputed islands, or offer any territorial concessions to Japan.

There is much evidence of governments pursuing domestic mobilization of their people around territorial disputes by using nationalist rhetoric and rallying around the flag. When it comes to these attempts, the public generally accepts them when they center on defending or claiming territory that is perceived as rightfully belonging to the state, especially when they are in the interest of the public (Hensel Reference Hensel2001; Kimura and Welch Reference Kimura and Welch1998). This is particularly true when territory is threatened, such as in reaction to Japan's 2012 attempt to bring the Dokdo/Takeshima dispute to the International Court of Justice. When circumstances like this occur, governments and civic groups actively rally the public behind the leadership in defense of “the homeland.” In Korea, historical disputes with Japan play an important part in Korean nationalism (Cha Reference Cha2000).

Increased approval ratings can bring about two primary possible effects in domestic politics. First, thanks to increased job approval ratings and rising nationalism, presidents can divert public attention from domestic issues and reduce pubic criticism of their political leadership. In Korea, like other democratic regimes, leaders are concerned with their public opinion ratings. When Korean-Japanese external crises occur, political leaders who are politically vulnerable can avoid further disapproval. Second, external crises and boosted popularity can create an opportunity for the president to strengthen his or her political base. When the level of public support for the president is very low due to the public's dissatisfaction with the president's job performance, the president may use external crises in order to demonstrate his or her competency in foreign policies, and thus enhance public evaluations among key partisan supporters (Morgan and Bickers Reference Morgan and Bickers1992), independent or undecided voters (Foster and Palmer Reference Foster and Palmer2006), or the mass public in general (Fordham Reference Fordham1998). Therefore, a president whose popularity is boosted as a consequence of external crisis can take advantage of it to solidify his or her political base, advance key policies effectively, or increase the chances of winning an election. We can observe these domestic political effects in several examples in Korea.

An example of the rallying effect around Dokdo, resulting in increased public support of the Korean political leadership, occurred in an April 2006 crisis when the Japanese Coast Guard announced plans to dispatch maritime survey ships to the waters around Dokdo. In response to Japan's actions, Korea deployed twenty naval and coast guard vessels, as well as surveillance planes, to the disputed area to monitor the situation, and even went so far as to threaten the use of force against any Japanese ships in the area. In terms of domestic actions, during the crisis the Korean Ministry of Education also significantly increased the amount of focus in curricula to teach about Korea's ownership of the Dokdo Islands.

In response to Japan's plans, the domestic population of Korea professed a surge of support for Dokdo, which included the production of t-shirts and other things with “I Love Dokdo” on them, mass participation in online commentaries about Dokdo, and even deposits of money into accounts linked to Dokdo (S. Lee Reference Lee2006). Beyond the domestic support for President Roh Moo-hyun's stance on Dokdo, the ruling and opposition parties of Korea, including the Grand National Party (GNP), openly supported the president's stance against Japan (Midford Reference Midford and Söderberg2011). The opposition GNP and ruling Uri Party even announced that they would work together to set up a joint parliamentary task force called a “committee on Dokdo protection and (Japan's) distortion of history” (S. Lee Reference Lee2006).

President Roh's reaction to the Japanese survey ships occurred a week after a leaked report from the Japanese Foreign Ministry stated that Roh and his administration were using the dispute in an attempt to shore up domestic support, as well as improve the low public opinion ratings of his administration. The report stated that “[t]he Roh Moo-hyun administration is expected to continue with its anti-Japanese policy to raise its low approval rating,” and that “[t]he Roh administration is fanning nationalism by bringing up disputes over the Dokdo islets [Takeshima in Japan]” (Ye and Park Reference Ye and Seung-hee2006). The report presented Roh's approval ratings as being on average only 20 percent, though this leaped to 40 percent once he made a speech about Japan and Dokdo at the March 1 Independence Movement Day (Agence France Presse 2006). Especially convenient for Roh, the April crisis dominated public discourse and the news, effectively sweeping the leaked Japanese report under the rug.

During the week following the end of the crisis, Roh stated on a live Korean television broadcast that he had followed the will of the people in regard to Dokdo: “To our people, Dokdo is the symbol of our full restoration of sovereignty,” he said, warning Japanese leaders to “stop insulting acts against the sovereignty and pride of Koreans” (Agence France Presse 2006). Roh also noted that Korea had the right to call the islands and sea by Korean names, and that Dokdo would become part of Korea's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) following planned negotiations with Japan on EEZs. As a result of his strong nationalistic response and his demonstration of competency in foreign policy, President Roh saw a substantial improvement in his approval ratings, though his Uri Party still ended up losing local elections in May (Wiegand Reference Wiegand2015).

Another example occurred when Korean President Lee visited Dokdo in August 2012. As a consequence of his surprise visit and Japan's negative reaction to it, the president enjoyed about a 10-point increase in his popularity in Korea. Approaching the end of his term, Lee had been experiencing low public opinion ratings for several months as a result of corruption scandals involving his relatives and associates, as well as a scandal in which the executive branch was conducting illegal surveillance of civilians. In the months before the cancellation of the joint military cooperation treaty signing with Japan, Lee's public approval ratings saw a low of 27.6 percent in January 2012 and only rose to 30.4 percent in April (Kim and Friedhoff Reference Kim and Friedhoff2012). Any leader in Lee's domestically vulnerable position would likely have done what Lee did by calling off the signing in favor of seeking to improve domestic approval ratings, which occurred when he visited the Dokdo Islands. Within weeks of the public outcry against the potential joint military cooperation with Japan—a plan to sign an information-sharing agreement with Japan in July 2012—Lee became the first Korean leader to visit the islands, a visit timed to occur just days before Liberation Day (celebrating Korean independence from Japanese rule) in August. Thanks to this visit, Lee could divert public attention from domestic political issues, reduce criticism of his leadership, and especially reduce his pro-Japanese image to some extent. Unlike his approval ratings in previous months prior to the cancelation of the joint military treaty with Japan, the approval rating of Lee's visit to Dokdo reached as high as 83.6 percent (Kim and Friedhoff Reference Kim and Friedhoff2012; Kim, Friedhoff, and Kang Reference Kim, Friedhoff and Kang2012).

In addition to using disputed territory to rally domestic mobilization and avoid criticism, leaders also need to consider policy choices’ possible effects on their public opinion ratings, their own reputations, and those of their political parties, or if elections are upcoming, on the incumbent leader's ability to be reelected (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Morrow, Siverson and Smith2003; Fearon Reference Fearon1994). In the Korean political context, support for the president is often positively associated with support for the governing party. In this regard, President Lee's Dokdo visit promoted nationalist sentiments among Koreans, diluted the pro-Japanese image of his party, and energized conservative voters, which eventually contributed to Park Geun-hye's victory in the presidential election in December of that year to some extent. Similarly, for conservative Japanese politicians such as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, territorial disputes over Dokdo/Takeshima or Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands can be viewed as an effective tool or opportunity to strengthen their political bases in Japanese domestic politics, hence accelerating their military buildup or the Peace Constitution revision plans (Hwang and Nishikawa Reference Hwang and Nishikawa2017; Yokota Reference Yokota2012).

In Korea, like in other democratic regimes, leaders are concerned with their public opinion ratings, so when they are politically vulnerable they will often consider the opinions of their constituents on foreign and domestic decision making with the hope that further disapproval is avoided. A leader's concern that he or she will be punished by the opposition, selectorate (those who actually influence political decision making like the military and elite), or the public will generally influence foreign policy decision making and create an incentive to utilize external crises to promote leadership popularity (Buena de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Morrow, Siverson and Smith2003; Fearon Reference Fearon1994; Gelpi and Grieco Reference Gelpi and Grieco2001).

However, as they are unable to predict the effects of controversial foreign policies on the populace, leaders become cautious about their policy decisions, particularly when they wish to keep themselves and their parties in power (Huth and Allee Reference Huth and Allee2002). This being the case, leaders should be cautious in pursuing policies that oppose nationalist rhetoric, since this could damage their credibility, harm their reputation, and give rise to the possibility of domestic punishment (Wiegand Reference Wiegand2011). When leaders are more vulnerable domestically, they will become less likely to pursue strategies that are viewed as unpopular, and this might lead to public unrest and domestic punishment of the leaders’ base of support. This is particularly problematic when it comes to South–North Korean conflict. External crises with North Korea often generated rally effects in South Korea prior to its transition to democracy. Since democratization, however, such rally effects have not been observed. On the contrary, South Korean presidents’ popularity often goes down as a consequence of South–North Korean conflict. For example, President Lee Myung-bak's approval ratings went down from 50 percent to 39 percent right after South and North Koreans exchanged gunfire along the Northern Limit Line (NLL) in November 2009. This is probably because the South Korean public may perceive military crises with North Korea as a signal of the president's incompetency in foreign policy (Lee and Hwang Reference Lee and Hwang2015).

In contrast, Korea-Japan historical disputes became more salient than before in domestic politics in democratized Korea, and these disputes remain strong rally points. We argue that this trend is associated with democratization and rising nationalism in Korea. The experience of democratization has promoted Koreans’ national pride and self-confidence in their ability to control their own destiny. The demand from the Korean public to redefine Korea's foreign relations with neighboring states and rectify historical issues has risen. Consequently, due to unresolved historical issues that include mutual claims of sovereignty over Dokdo and apologies and compensation to comfort women, the level of emotional animosity toward Japan is relatively high in Korea. In addition, while rising nationalism creates positive sentiments toward the other half of Korea in the peninsula, it feeds negative sentiments toward Japan over historical issues, and easily mobilizes South Koreans under their national flag.

Another interesting observation with respect to the rally effects is that Korean-Japanese crises have a significant impact on public mobilization, especially among young people. It is generally thought that young people in their twenties and thirties are apathetic and indifferent to politics and thus less likely than older people to engage in political participation in contemporary Korean politics. However, when it comes to Korean-Japanese historical disputes, young people are not different from other Koreans, and even they are strongly motivated and politically active. In this regard, analyzing the impact of Korean-Japanese historical disputes on public mobilization is important and unique in understanding contemporary Korean politics.

In sum, we expect that Korean political leaders will enjoy rally effects and boosts in short-run support of their leadership as a consequence of external crises, as the rally-round-the-flag effect theory explains. The Dokdo dispute and other historical disputes with Japan are expected to generate such positive rally effects in Korea. Thus, our hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 1a:

When a crisis related to a historical dispute with Japan occurs, Korean presidential job approval ratings are likely to soar.

Hypothesis 1b:

When a crisis with Japan over Dokdo occurs, Korean presidential job approval ratings are likely to increase.

Research Design: The Empirical Strategy of Testing the Rally-Round-the-Flag Effect

As a way of evaluating the impact of Korea-Japan historical disputes on the popularity of political leadership, this article examines Korean presidential approval ratings between 1993 and 2016.Footnote 5 The dependent variable in this analysis is presidential job approval ratings collected by Research & Research, one of Korea's top survey institutes. The institute conducted telephone surveys (N = 800) on a monthly basis. Samples in the surveys are randomly selected across regions and evenly distributed across different groups of people in terms of age and gender by assigning weights. Accordingly, the survey results are not likely to be biased or influenced by specific groups of people. The unit of analysis is presidential rating per month.

The key explanatory variable is Historical Disputes, which is coded 1 for any crises between Korea and Japan concerning historical issues such as the declaration of Takeshima Day in March 2005, and 0 for no crisis (see table 1A in the appendix for detailed information on crises and events). This variable is coded 1 for the month a crisis occurs (and the following month) and 0 otherwise. Territorial disputes are supposed to generate stronger rally effects than other historical disputes. To see how the Dokdo issue alone produces rally effects, we also create a variable for Dokdo Crisis, which is coded 1 for the occurrence of a dispute over Dokdo and 0 otherwise.

Several control variables explain presidential popularity and are also associated with historical disputes, including Dokdo crises. The first is South–North Korean disputes. Since the Korean War ended in 1953, the two Koreas have remained under the Armistice Agreement and have occasionally engaged in militarized disputes. Since this issue looms large over Korean politics, we include this factor to examine the influence of inter-Korean military conflict on presidential popularity in South Korea. Military Conflict is coded 1 for an inter-Korean military conflict and 0 otherwise.

Previous scholarship argues that several other variables are important in the analysis of presidential approval ratings. Presidential popularity tends to decline over time (Brace and Hinckley Reference Brace and Hinckley1992; Eisenstein and Witting Reference Eisenstein and Witting2000; Stimson Reference Stimson1976). To control for popularity decay effects, we employ two variables, Time in Office and Honeymoon. Time in Office, which captures gradual erosion in presidential approval, is coded 1 for the first year, 2 for the second year, and so on, up to 5 for the last year of each presidency. Since presidents typically enjoy a honeymoon period immediately following their election, we include a dummy variable, Honeymoon, which is coded 1 for the first six months of each president's term in office and 0 otherwise. The baseline presidential popularity and the probability of having external crises may differ across different political leadership. To control for presidents’ unique characteristics, we also include four dummy variables, Kim Dae-jung, Roh Moo-hyun, Lee Myung-bak, and Park Geun-hye, leaving Kim Young-sam as the reference category in the models.

To control for economic conditions that reward or punish the incumbent president (Baum and Kernell Reference Baum and Kernell2001; Chappell and Keech Reference Chappell and Keech1985; Lewis-Beck Reference Lewis-Beck2006), we use unemployment and inflation rate variables collected by Statistics Korea. Unemployment and inflation are expected to have a negative relationship with presidential popularity. Individuals’ perceptions about the economy may also affect presidential popularity (Clarke and Stewart Reference Clarke and Stewart1994; Norpoth Reference Norpoth1996). We use Retrospective Pocketbook and Prospective Pocketbook variables in the Consumer Sentiment Index, assembled by the Samsung Economic Research Institute and the Bank of Korea, to measure individuals’ evaluations of present and future economic conditions. These two variables are expected to have a positive impact on presidential popularity.

Trust in government is essential in explaining public support for the president. A high level of trust in government is likely to promote presidential popularity.Footnote 6 Trust in government data comes from the Korean Social Science Data and the Edelman Trust Barometer. The variable varies from 1 (little) to 4 (a lot). Present or former scandals can affect public support for the president (Ostrom and Simon Reference Ostrom and Simon1985; Smyth and Taylor Reference Smyth and Taylor2003). When a former president's or his or her family members’ scandals are detected and prosecuted, the incumbent president is expected to enjoy a boost in his or her popularity as a reformer. In contrast, a president's approval ratings are expected to decline when the incumbent or his or her family members fall under legal indictment or are involved in corruption. The dummy variables of Ex-scandals and Present Scandals are coded 1 for the occurrence of a scandal and 0 otherwise.

We also control for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout and the impeachment trial of President Roh Moo-hyun since the financial crisis in Korea, called the IMF crisis in November 1997, significantly dropped President Kim Young-sam's popularity. The dummy variable of The IMF Bailout equals 1 for the last four months of the Kim Young-sam presidency and 0 otherwise. The impeachment trial of President Roh Moo-hyun by the National Assembly in March 2004 boosted the president's approval rating. The dummy variable of Impeachment Trial is coded 1 in the period of March–May 2004, and 0 otherwise. We expect that the IMF bailout variable has a negative impact, while the impeachment trial has a positive impact on presidential popularity. Finally, we control for two inter-Korean summit conferences in 2002 and 2008. The dummy variable of Summit Meeting is coded 1 for the conference event and 0 for no event. For descriptive statistics of the data, see table 2A in the appendix. To address the potential autocorrelation problem in the analysis, we estimate the models using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with Newey-West standard errors (Newey and West Reference Newey and West1987).

Results

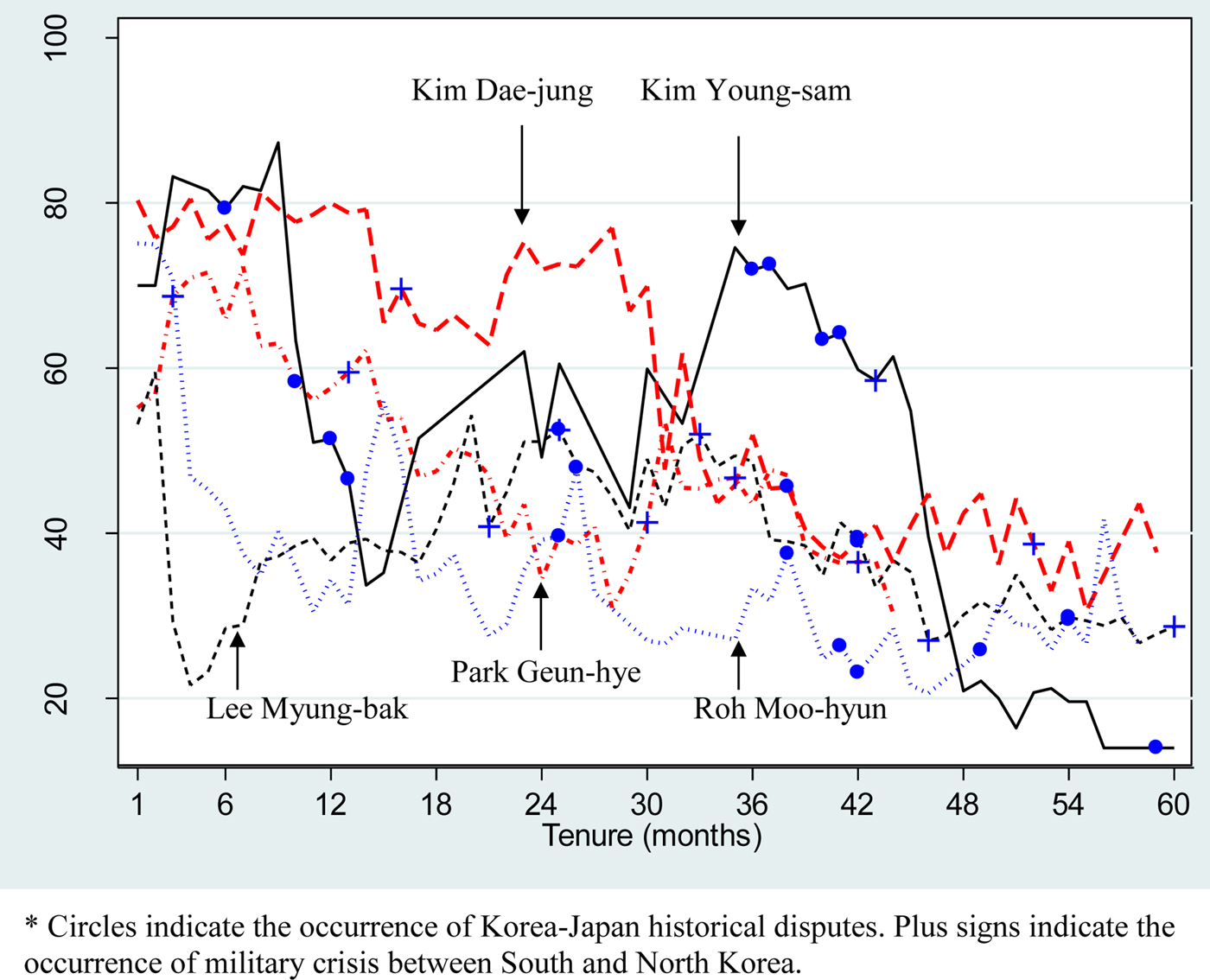

We start our results with figure 1, which shows the changes in presidential job approval ratings over time for five presidents, and the occurrence of Korea-Japan historical disputes (circle symbols). Although a clear pattern is not observed with respect to the influence of historical disputes on approval ratings, in general a crisis occurs when the approval rating is in a descending trend, and the approval rating tends to go up after the crisis. These findings provide initial support for the hypotheses.

Figure 1. Presidential approval ratings in South Korea (1993~2013). Circles indicate the occurrence of Korea-Japan historical disputes. Plus signs indicate the occurrence of military crises between South and North Korea.

We now turn to results of the OLS regression of the rally effects of historical disputes in Korea, reported in table 1. Model 1 examines the occurrence of crises specifically about the Dokdo Islands dispute, along with military conflict between North and South Korea, and time in office variables. The main finding in this model is that a crisis regarding Dokdo has a statistically significant and positive effect on presidential approval ratings. Holding other variables constant, the occurrence of a Dokdo crisis is likely to increase the Korean presidential approval rating by about 9.3 percent.

Table 1. Presidential approval ratings in South Korea (1993–2016).†

† OLS estimates with Newey-West standard errors (lag = 4); two-tailed tests; ***p ≤ 0.01, **p ≤ 0.05, *p ≤ 0.10.

In Model 2, which controls for multiple economic and political factors, a Dokdo crisis is again statistically significant and positive. The substantive effect is that Dokdo crises promote presidential approval ratings by about 6.4 percent. In Model 3, which combines all occurrences of crises about any Korea-Japan historical dispute, including Dokdo crises, we find that historical disputes are also statistically significant and positively correlated with higher presidential approval ratings. The actual effect is an increase in presidential approval ratings by about 4.4 percent.Footnote 7 These increases in the approval ratings are fairly substantively significant.Footnote 8 This suggests that, whether or not intended by political leaders, historical disputes with Japan, especially Dokdo crises, tend to stir nationalistic sentiments and hence boost support for the Korean political leadership, at least in the short run. For example, when the Japanese prefecture of Shimane declared “Takeshima Day” in March 2005 and the Japanese history textbook controversy occurred in the following month, massive public protests in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, which engaged in burning Japanese flags and pictures of Japan's prime minister, were observed. Anti-Japanese sentiments spurred Koreans to suspend a great number of exchange programs with Japan. The Korean presidential approval ratings improved from 35.6 percent in January to 39.6 percent and 47.9 percent in March and April of that year respectively.

These results imply that, in particular, Dokdo crises can be utilized by political leaders as a tool for rally effects. Therefore, we find strong support for both of our hypotheses about how historical disputes between Korea and Japan impact presidential approval ratings for Korean leaders.

The results in table 1 also show that other control variables have their expected effects on presidential popularity. Inter-Korean military conflict does not appear to generate rally effects in Models 2 and 3. This is probably because the prolonged history of tension and conflict with North Korea may generate fatigue among South Koreans and hence the occurrence of occasional inter-Korean military conflict may be viewed by South Koreans as a signal of weak political leadership or the president's foreign policy incompetence. Thus, it fails to unite and rally them under patriotism. This also may be because the information cue in South Korea has been recently diversified and thus the influence of opinion elites on citizens has been limited (Lee and Hwang Reference Lee and Hwang2015).

All models also identify the existence of the popularity decay and honeymoon effects. Although presidents tend to enjoy strong public support at the beginning of their term in office, the presidential approval ratings are likely to decline as time goes by. Every year in office, presidential approval ratings decline by about 4.4 percent. Inflation tends to negatively affect presidential job approval. One percentage increase in the inflation rate decreases the approval ratings by about 2 percent. Models 2 and 3 show that the higher the expectation for self-interest is, the higher the presidential job approval ratings are. On the other hand, the Retrospective Pocketbook variable does not have a statistically meaningful impact on approval ratings. Present scandals such as the indictment of a president's son are likely to lower presidential popularity, while former scandals such as the prosecution of the former president(s) tend to increase the job approval of the incumbent president, although only the effects of present scandals are statistically significant. The IMF bailout had a strong negative impact on presidential popularity, causing about a 25 percent decline in the approval ratings, while trust in government and summit meetings positively influence presidential job approval (about 14 and 20 percent increases respectively).

To evaluate the statistical significance of differences in approval ratings between presidents, we re-estimated the models by rotating the reference category among all five presidents. Holding other variables constant, Kim Young-sam followed by Kim Dae-jung and Park Geun-hye enjoy higher approval ratings than other presidents. Although Lee Myung-bak has the lowest, there is no statistically meaningful difference between Lee Myung-bak and Roh Moo-hyun in their approval ratings.

Conclusions

This article started with a theoretically intriguing research question: Do Korea-Japan historical disputes generate presidential rally effects? The empirical results of the models of Korean presidential job approval ratings confirm the existence of such effects in Korea. That is, regardless of their intent, Korean political leaders can enjoy increased popularity domestically to a great extent as historical disputes, especially Dokdo crises, with Japan erupt. Since colonial legacies, unresolved historical disputes such as Dokdo and comfort women, and their shadows remain significant in Korea, nationalist sentiments can easily mobilize people and boost internal solidarity around political leadership in Korea, as the rally-round-the-flag effect theory explains.

Our claims and findings suggest that the occurrence or consequence of historical disputes can be analyzed from the view of domestic politics. Based on the positive correlations of the Dokdo crises and historical disputes with increased presidential approval ratings, we can conclude that these disputed issues between Korea and Japan not only affect Korean-Japanese bilateral relations, but also significantly impact Korean domestic politics. Even with the threat of North Korea looming large over South Korea, concerns about the economy and unemployment, and corruption issues tied to political leaders in Korea, the historical disputes with Japan continue to impact presidential approval ratings more than seven decades after the end of Japanese colonial control of Korea. There is little doubt that the issues disputed between Korea and Japan will continue to impact domestic politics in Korea, unless major strides are made in resolving the disputes over ownership of the Dokdo Islands, the status and recognition of Korean comfort women during the Second World War, and several related historical disputes that continue to influence animosity between these two states.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Academy of Korean Studies (KSPS) Grant funded by the Korean Government (MEST) (AKS-2012-AAZ-2101).

Appendix: External Crises and Descriptive Statistics

Table 1A. External crises, March 1993–October 2016.

Table 2A. Descriptive statistics (1993~2016).