Introduction

About 477,000 Canadians live with a diagnosis of dementia, with those aged 80 and older being 6 times more likely to be diagnosed with this condition (Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC], 2024). Older adults living with dementia, as well as their caregivers, may experience challenges hindering their ability to remain within their home, such as the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). BPSDs consist of non-cognitive symptoms and behaviours affecting the person’s functionality, such as agitation, anxiety, irritability, apathy, disinhibition, delusions, and sleep changes (Cerejeira et al., Reference Cerejeira, Lagarto and Mukaetova-Ladinska2012). As a result, more than 40% of older adults being diagnosed with dementia are living or will be relocated in long-term care (LTC) (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2024), notably due to higher care needs and/or worsening BPSD (Cepoiu-Martin et al., Reference Cepoiu-Martin, Tam-Tham, Patten, Maxwell and Hogan2016; Protecteur du citoyen, 2021). As care transitions may have a detrimental impact on older adults’ physical and psychological health (Abraham et al., Reference Abraham, Kannampallil and Patel2012; Ryman et al., Reference Ryman, Erisman, Darvey, Osborne, Swartsenburg and Syurina2019; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Sahadevan and Ding2006) and well-being (Stones & Gullifer, Reference Stones and Gullifer2016), it is important to prevent or delay relocations in LTC.

A Canadian report estimated that around 10% of relocations in LTC could have been avoided with adequate support (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2025). Thus, providing adaptive and evolving care and environment for older adults to engage in daily activities in accordance with their own abilities and preferences could enable older adults to age-in-place as desired, within an environment of their choice (Binette & Farago, Reference Binette and Farago2021). Seniors’ residences (SR), such as those providing assisted living, are a promising environment as they promote engagement in leisure and social interactions and offer support for instrumental and basic activities of daily living (e.g., prepared meals, housekeeping, personal aid) (Boubaker et al., Reference Boubaker, Negron-Poblete and Morales2021). As a collective dwelling, SRs can accommodate a variety of older adults presenting physical and functional limitations, such as those living with chronic illnesses or cognitive impairment. SRs could also act upon and reduce older adults’ vulnerabilities, like risks of falls and medical issues (Boubaker et al., Reference Boubaker, Negron-Poblete and Morales2021), reflecting the care and services already provided to older adults living in SRs. Considering that about 27% of people aged 75 and older live in a SR in the province of Quebec (Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être, 2021), which is significantly higher than in other provinces (Hou & Ngo, Reference Hou and Ngo2021), SRs could be promising to provide adaptive and evolving care and consequently reduce future care transitions in LTC.

Based on this premise, a partnership involving the public home care services, a private SR, and our research team was put in place to co-develop and assess a new approach called ‘Vieillir chez soi’ (VCS, i.e., age at home in English) to provide evolving care in order to prevent or delay relocations in LTC. Inspired by continuing care retirement communities, which consist of various levels of care delivered in different floors or settings (Shippee, Reference Shippee2009), the study aimed to adapt an existing SR into an evolutive environment allowing residents to age in place despite loss of independence and increasing assistance needs. To our knowledge, no studies have developed such an approach within (a) an existing setting, while (b) promoting interactions and openness between residents from different levels of care. Integrating a person- and family-centred approach, the study aimed to (1) adapt and (2) implement best and innovative practices within the SR to provide adaptative care based on the increasing older adults’ assistance needs; and (3) document the effect of the VCS approach on the residents’ functional autonomy profile, relocations in LTC, emergency visits, and hospitalizations. More specifically, we hypothesize that the VCS approach could enable residents with higher functional autonomy profile to age-in-place, delay relocations in LTC of at least 6 months, and promote returns to the SR following a hospitalization or emergency visit.

Methodology

Study design

A living lab (LL) approach was employed to co-develop, implement, and evaluate the VCS approach within the SR. LLs are a relevant methodology for co-developing and implementing complex interventions in real-life settings, as they equally involve stakeholders in a co-creative and collaborative approach (Dubé et al., Reference Dubé, Sarrailh, Billebaud, Grillet, Zingraff and Kostecki2014). By engaging end-users as active co-producers (Hyysalo & Hakkarainen, Reference Hyysalo and Hakkarainen2014), LLs enable the documentation of their evolving needs, motivations, knowledge, and experiences regarding the interventions to implement (Pierson & Lievens, Reference Pierson and Lievens2005). Through this detailed understanding of end-users’ perspectives, along with their evaluation of proposed solutions within real-life settings, LLs foster the development and ‘shaping’ of innovations tailored to their specific context (Logghe & Schuurman, Reference Logghe and Schuurman2017; Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Freeman, Koopmans, Ross and McAloney2021).

More specifically, an Interrupted Time Series Analysis (ITSA) was used to explore the impact of the VCS approach on the residents’ functional autonomy profile. ITSA is a statistical approach evaluating the immediate and sustained impact of an intervention or policy (i.e., interruption) on time series data using segmented linear regression (Bernal et al., Reference Bernal, Cummins and Gasparrini2016). This study was approved by the Ethical Board of the CIUSSS de l’Estrie – CHUS (2023-4741). All stakeholders provided informed consent and approved for their participation and input to be documented as part of the project.

Co-development of the care approach

Context of implementation

The VCS approach was co-developed and implemented in collaboration with a private residence for semi-independent seniors situated in a rural town in the province of Quebec (Canada). The SR included 111 rooms distributed on three free-access levels. Residents were free to walk around the residence, as well as access an enclosed outdoor garden in the summer. Before the study and the implementation of the VCS approach, residents who required physical or cognitive assistance to eat or move safely were relocated to LTC. Residents demonstrating BPSDs, such as aggressive behaviours, intrusive wandering, public incontinence, or high resistance to care, were also relocated. As nursing care provided on-site was limited, residents requiring regular nursing care, such as those in palliative care, had to be relocated to ensure continuity of care.

Co-development process

Stakeholders from the SR, the local home care services (provided by the public healthcare system) and our interdisciplinary research team, were invited to participate in the co-development of the VCS approach. Stakeholders from the SR included family caregivers, staff (e.g., personal support worker [PSWs], nursing staff, support staff, and leisure technicians), managers, and the owners. Family caregivers and staff were invited to participate using posters installed in the SR and an invitation email sent by one of the SR managers. Occupational therapists, nurses, social workers, and multi-level supervisors from the home care services, were also involved when needed, depending on their roles with the SR and emerging challenges (e.g., involvement of nurses to support nursing care transitions, inclusion of occupational therapists to optimize the integration of specialized intervention plans for challenging behaviours). Our research team comprised experts from diverse fields, such as health sciences (e.g., occupational therapy, nursing, social work), computer sciences, management, and law.

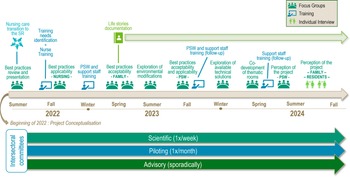

Initiated in January 2022, the co-development process was conducted over a 3-year period, during which three levels of inter-sectoral committees continuously met to promote collaboration and inter-connectedness between stakeholders. These committees included:

-

(a) Scientific committee, composed of the main researcher (VP) and the research assistants (n = 4), aimed to supervise the operationalization and scientific requirements of the project. Weekly meetings engaged other stakeholders depending on the meeting’s objectives, such as members of the interdisciplinary research team and specific end-users.

-

(b) Piloting committee, composed of 8 to 10 persons, including members of the research team, supervisors from the local home care services (i.e., nursing, rehabilitation, social work, and management), and the SR management team and owners, met each month to coordinate and monitor each step of the project.

-

(c) Advisory committee, composed of four to five persons, including the main researcher and the higher management of the public home care services, met sporadically to guide the project and its orientations, including future transfer in other contexts.

Methods

Focus groups including three to six participants were conducted with family caregivers (n = 2), the residence staff (e.g., PSWs, nursing staff; n = 3), and clinicians from the home care services (n = 2) to document their perspectives as stakeholders in the VCS approach. Each group was interviewed to understand: (a) their needs as stakeholders providing care to older adults living at the SR; (b) their perspectives regarding various potential interventions that could be implemented within the residence; (c) the strategies that could be used to facilitate their implementation; and (d) the indicators that should be documented during the evaluation phase. Focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed. The timeline of the project is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Timeline of the co-development process for the care approach.

Before each focus group, an interview guide was developed and validated within the team. To facilitate the co-development process, a summary of best practices and innovative interventions identified in the literature was first presented to stakeholders (Chmielewski et al., Reference Chmielewski and EDAC2014; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Topfer and Ford2019; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Cheong, Ong, Fusek, Wee and Yap2021; Marquardt et al., Reference Marquardt, Bueter and Motzek2014; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021; Royston et al., Reference Royston, Mitchell, Sheeran, Strain and Goldsmith2020; Voyer & Allaire, Reference Voyer and Allaire2020). Stakeholders were then questioned regarding the perceived relevance of these interventions within their context, as well as their applicability and acceptability. These considerations guided the prioritization of interventions and strategies to integrate only practices that were deemed pertinent and acceptable for stakeholders. As a result, some interventions initially described as pertinent, such as technological solutions, were found to be inapplicable later. To support prioritization, we used the TRIAGE method, that is, Technique for Research of Information by Animation of a Group of Experts, which is a structured group animation method aiming to obtain a group consensus (Gervais & Pépin, Reference Gervais and Pépin2002). When applicable, minor adaptations and strategies were also proposed based on our research experience to optimize the interventions applicability and facilitate their implementation within the SR, as well as indicators to support their monitoring. Following the prioritization process, interventions were iteratively and progressively implemented within the SR, adapted, and continuously monitored by the inter-sectoral committees using the co-identified indicators. Implemented interventions are described in the Results.

Evaluation of the VCS approach

Following the initial implementation in September 2022, multiple variables were documented retrospectively and throughout the study to explore the effect of the VCS approach on the SR ability to provide evolving care and maintain older adults within their living environment. Data pertaining to all older adults admitted and living at the SR were documented over a 3-year period divided in three phases (Y1: September 2021 to August 2022; Y2: September 2022 to August 2023; Y3: September 2023 to August 2024) using home care services records (e.g., RSIPA) and follow-up from the SR nursing team.

Measures

Functional autonomy profile

ISO-SMAF profile: Considering our hypothesis that the VCS approach could enable residents with higher functional autonomy profiles to age-in-place, the residents’ functional autonomy was documented throughout the study using the ISO-SMAF profile. Composed of 14 profiles based on the person’s level of autonomy in mobility, mental functions, communication, activities of daily living, and instrumental activities of daily living, the ISO-SMAF profile categorizes individuals depending on their difficulties and assistance needs (Dubuc et al., Reference Dubuc, Hébert, Tousignant and Edisem2004). This classification is calculated based on the SMAF score, which has a very high test–retest and inter-rater reliability (Desrosiers et al., Reference Desrosiers, Bravo, Hébert and Dubuc1995) and validity (Hébert, Dubuc, et al., Reference Hébert, Dubuc, Buteau, Desrosiers, Bravo, Trottier, St-Hilaire and Roy2001; Hébert, Guilbault, et al., Reference Hébert, Guilbault, Desrosiers and Dubuc2001). The ISO-SMAF profile classification has a good predictive validity, explaining 80% of the nursing care time and cost (Dubuc et al., Reference Dubuc, Hébert, Desrosiers, Buteau and Trottier2006). This assessment tool is usually completed annually or whenever significant functional changes occur and is integrated within usual care in home care services. In Quebec, individuals with an ISO-SMAF profile of 10 and higher are usually eligible in LTC (Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux, 2023).

For this study, the ISO-SMAF profiles of residents were documented (a) at admission, (b) at departure, and (c) monthly throughout the study. The dates at which residents were scored an ISO-SMAF profile of 10 and higher were also documented to determine the proportion of residents eligible in LTC (which should increase over time considering the initial hypothesis), and the number of days residents stayed at the SR despite being eligible in LTC.

Relocation

To document the VCS approach ability to prevent or delay relocations in LTC, three variables were documented: delay between the notice of exceeding care service offer and the resident’s departure, the causes of departure, and the number of days between relocation in LTC and end of life.

Delay between the notice of Exceeding Care Service Offer and departure: In Quebec, private seniors’ residences are required to send a notice of exceeding service offer to home care services when a resident requires more assistance than what they can provide within their service offer and would benefit from a relocation in another living context (e.g., LTC) (Regulation respecting the certification of private seniors’ residences. RLRQ, S-4.2 r. 0.01, art. 51). To assess the potential impact of the VCS approach on delaying relocation, the number of days between the issuance of a notice and the subsequent relocation was documented retrospectively for the year preceding implementation (Y1). For Y2 and Y3, the moment a notice would have been sent using the same criteria as before (i.e., in comparison to the services offered before the project) was documented monthly in collaboration with the nursing chief of the SR. Using this reference date, the number of days between notice of exceeding service offer and relocation was calculated and compared to the data documented for Y1.

Causes of departure: The nature (e.g., death, relocation, other) and causes (e.g., financial reasons) of departures were documented for each resident and phases (Y1, Y2, Y3).

Number of days between the relocation in LTC and death: The number of days between the relocation in LTC and end of life was documented and compared between each phase to explore whether relocations occurred later in life with the VCS approach.

Emergency visits and hospitalization

Data about emergency visits and hospitalizations were documented over the 3-year study to compare (a) the number of emergency visits and hospitalizations; (b) duration of hospitalizations and instances in which a patient is occupying a bed but does not require the intensity of services provided (i.e., alternate level of care [ALC]); and (c) the proportion of residents returning at the SR following a hospitalization or an emergency visit.

Data analysis

Qualitative data: Notes taken during the inter-sectoral committees and transcripts from the focus groups were iteratively reviewed and analysed by the research team using the method described by Miles et al. (Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldaña2019) to (a) identify the interventions that were the most applicable and acceptable within the context; (b) define the co-developed adaptations and implementation strategies to facilitate the integration of best practices, and (c) explore the factors hindering or facilitating the implementation of the VCS approach. All notes and transcripts were first carefully reviewed by two members of the research team (SR and SN) to identify relevant codes (e.g., proposed strategies and adaptations, factors). Obtained codes were then merge into categories and presented to stakeholders in the piloting committee to support the implementation and improvement of the VCS approach within the SR.

Quantitative data: Data documented over the three study periods were analysed using two methods. First, data pertaining to the residents’ functional autonomy profile and collected monthly over the study (e.g., mean ISO-SMAF profile, percentage of residents eligible in LTC) were analysed using ITSA. For this study, ITSA was conducted using ordinary least squares regression (OLS) and interruptions were defined as the implementation (and change) of the financial model.

Second, other variables were grouped by phases (Y1, Y2, Y3) and described using descriptive analysis. Comparison between study phases was then conducted: ANOVA for continuous variables (e.g., delays and number of days, ISO-SMAF profile at admission and departure), and chi-square tests for categorical variables and proportions (e.g., proportion of returns to the SR following hospitalization or emergency visit). When differences were significant, a post hoc Tukey’s test was completed to compare groups.

Results

Description of the ‘Vieillir chez soi’ approach of care

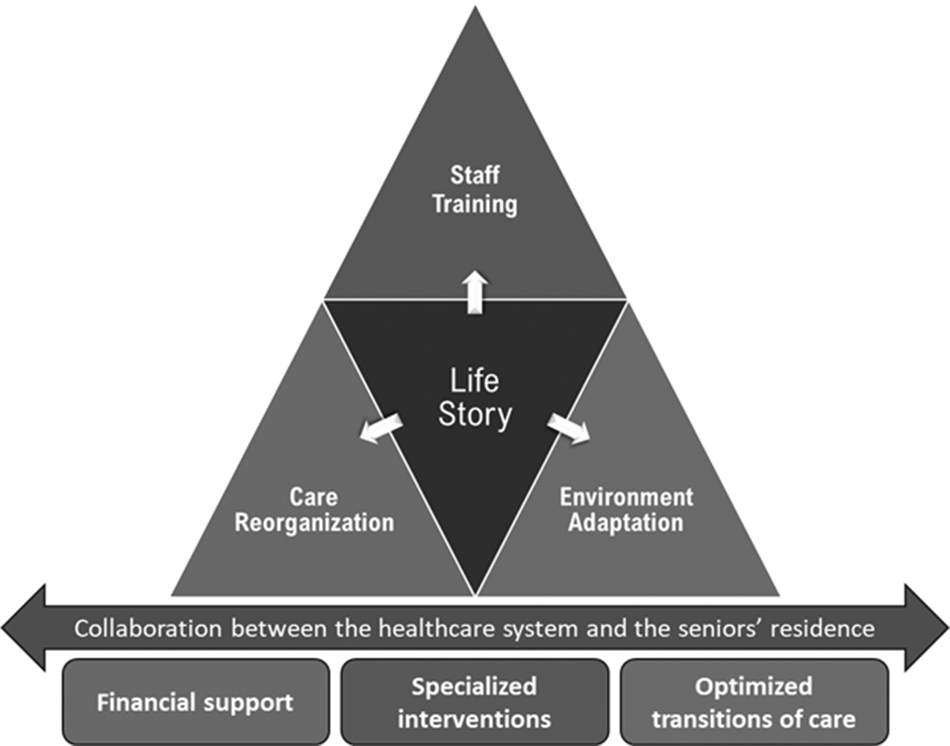

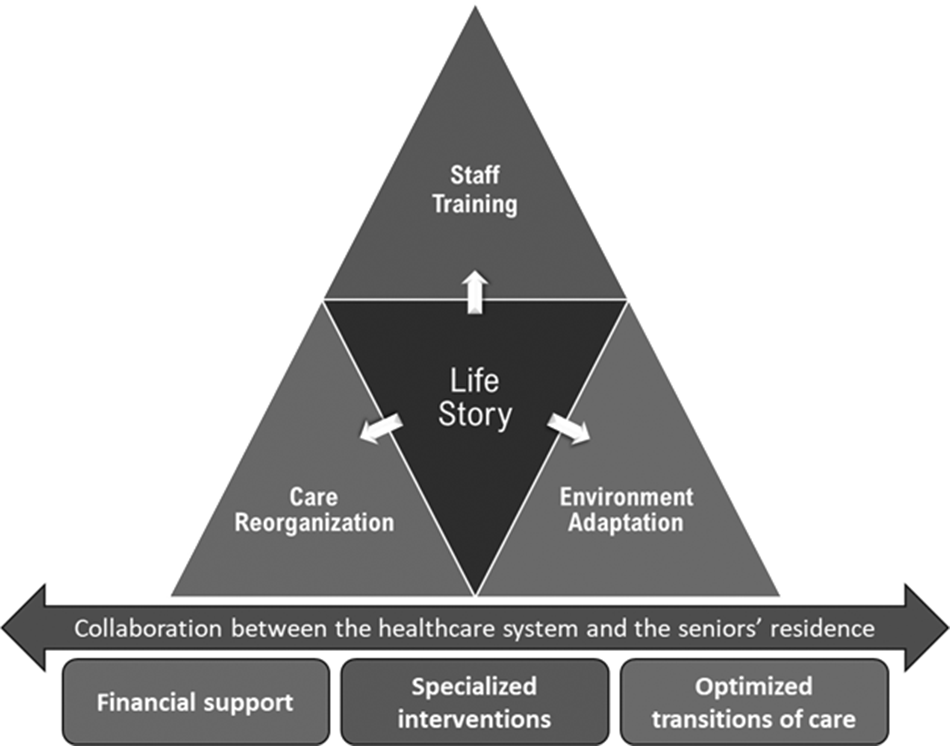

Considering the objective of promoting aging-in-place among older adults living in a SR, four priority domains of intervention were identified and implemented to provide evolving and personalized care: (a) documenting the life story of residents; (b) reorganizing care and services; (c) staff training; and (d) adapting the environment to create engaging and stimulating spaces.

As depicted in Figure 2, these four domains were supported by a continuous and optimized collaboration between home care services and the SR to ensure (a) financial support to enable residents to remain in their homes despite increasing assistance needs and associated costs; (b) specialized and personalized intervention plans for specific issues such as BPSD (e.g., aggressive behaviours, resistance to care), high fall risks, and pressure sores; and (c) optimized communications to facilitate transitions of care, including those related to hospitalizations and, when necessary, relocations in LTC.

Figure 2. Domains of intervention in the VCS approach of care to support aging-in-place.

Documenting the residents’ life story

Documenting residents’ life stories was identified as one of the most applicable interventions for the SR, while being central to a personalized approach of care based on the residents’ preferences and previous life habits. Prior to the study, data concerning the residents (e.g., preferences, interests, life habits, and previous occupations) were already documented, though its utilization was limited due to lack of access by PSWs. Therefore, facilitating access to this information was identified as a priority by stakeholders to promote personalized care within the SR. A three-page life story questionnaire and a condensed one-page version were co-developed in collaboration with stakeholders (e.g., PSWs, nursing staff, family caregivers) to document relevant data about the residents. Upon admission, the questionnaire was provided to the family for completion at home. For residents already living at the residence, an electronic version of the life story questionnaire was emailed to family members, followed by two reminders. The completed questionnaires were then collected by a trained staff member to share the most relevant personalized information using the one-page version. The one-page summary was displayed in the residents’ room or wardrobe so that PSWs could refer to it when needed and ensure privacy. The longer versions were compiled in a binder, also easily accessible to the care staff.

To facilitate the life story implementation and sustainability, a member of the research team and the staff member met multiple times to identify the best information to share through the one-page questionnaire. In total, 86 life stories were documented, displaying of 58.3% of the residents’ life stories 1 year after implementation. While approximately 53% of the families who received the questionnaire via email completed it, this percentage increased to about two thirds for those who received it at admission, suggesting that over time, more residents’ life story will be documented and displayed in their rooms. Overall, the one-page version of the residents’ life story was described as helpful and easy to use by PSWs, as it allowed for a personalized approach to care while providing potential ideas of diversions in case of challenging behaviours.

Care reorganization

Based on evidence (Alderson et al., Reference Alderson, Morin, Rhéaume, Saint-Jean and Ouellet2005; Aubry et al., Reference Aubry, Couturier and Lemay2020), a reorganization of care and services was implemented in an iterative and evolving manner to facilitate staff adaptation and training, while addressing the growing needs for assistance. One of the initial changes involved transferring nursing care to the SR. Previously provided by the public healthcare system, it was deemed essential to have onsite nursing care due to the heightened complexity and severity of residents’ needs. A nurse and an additional auxiliary nurse were hired, ensuring onsite nursing coverage during the day (7 days a week) and on-call availability in the evenings and nights. A head nurse was also appointed to oversee nursing staff and support the implementation of specialized intervention plans developed by the home care services.

Several adjustments were made for PSWs, including revising their schedules and runs to optimize efficiency, allowing more time for meaningful activities, assigning PSWs to specific floors and residents (pairing), reducing the resident-to-PSW ratio, creating new positions, and extending working hours. Specifically, the number of PSWs working from 6:00 a.m. to 9:30 p.m. doubled from 5 to 10, with two supervisory PSWs per shift. An additional PSW was hired for the night shift. These adjustments allowed the care staff to meet the residents’ increasing assistance needs, while promoting positive and meaningful interactions. They also felt validated through these changes, as mentioned by one of the PSWs: ‘What I find [meaningful is] the fact that… You’ve done something, you finish your day, you know you’ve done good for someone, you’ve made someone happy, you’ve given love’. Furthermore, a support staff member assisted with meals, as an increasing number of residents required feeding assistance. Inter-shifts meetings were introduced to facilitate communication between shifts and ensure continuity of care. Teamwork and communication between the care team were also promoted (i.e., identification of dyads within PSWs to facilitate mutual support during work shifts).

In addition, adjustments were made to the residents’ schedule. Previously, some residents were awakened at 5:00 a.m. for breakfast, but changes were implemented to delay the morning routine to 6:30 a.m. These adjustments proved beneficial as fewer residents needed to be awakened to begin their routine and they were more cooperative, aligning better with their previous life habits. Suggestions based on residents’ life stories were also made to the care team, though not always adopted by the SR staff, such as allowing residents to eat breakfast in pyjama and involve them in simple and repetitive productive tasks (e.g., preparing envelopes for family members or holiday baskets for staff members).

Staff training

Given the growing complexity of residents’ needs, stakeholders promptly emphasized the need to train care staff, particularly in delivering and adapting care for residents with BPSD. Training was conducted in multiple stages, depending on available resources and priorities. First, two 1.5-hour training sessions were conducted by the research team to address more urgent training needs, with nine and seven volunteers, respectively (PSWs and a secretary). These sessions focused on BPSD management, supporting morning routines, and integrating activities into daily tasks. A series of short video clips were also shared with the entire care team and support staff (e.g., secretaries, kitchen helpers) as reminders of best practices when interacting with residents with BPSD. Fact sheets presenting these recommendations were displayed in various locations around the SR, including staff rooms, stairwells, and PSW carts. Additionally, two members of the research team – an occupational therapist and an expert PSW with a master’s in gerontology – were available to mentor the care and support staff with any questions. For instance, they conducted mentoring sessions for a secretary who faced challenges with specific residents exhibiting BPSD.

Training was also provided by the public healthcare system. As nursing care transitioned from home support services to the SR, continuous training was provided to nursing staff (e.g., nurse and auxiliary nurses) to help them meet the increasingly complex and severe needs of residents. Furthermore, a comprehensive and mandatory 12-hours training program was implemented for PSWs. This four-session training covered fundamental caregiving approaches, understanding cognitive disorders and potential BPSD, managing these behaviours, and incorporating meaningful activities. Overall, the training and materials were found to be helpful, as the SR staff felt more competent in their work and ability to find a balance between the residents’ needs, the family desires, and the service offer’s limits.

Adapting the environment to create engaging and stimulating spaces

As residents’ ability to move safely and comfortably around the SR declined over time, several issues arose regarding the optimal spaces for stimulating and engaging with residents. Initially, residents were grouped on the ground floor near the dining room and front entrance of the residence. While this arrangement provided constant supervision, it also exacerbated challenging behaviours due to overstimulation and a lack of seating. Two new engaging and stimulating spaces were thus developed where residents could spend time with PSW, as well as with their families. First, a little-used room on the second floor was transformed into a living room inspired by a 1950s ice cream shop. This theme was chosen for its attractive colours, decorations, and nostalgic appeal to the residents’ younger years (i.e., potential for reminiscence). The room was decorated with a wallpaper depicting an ice cream shop, comfortable chairs and tables were added, and a smart television was installed to play videos and music based on the residents’ life stories and preferences. Additionally, a jukebox was introduced.

Second, a small farmhouse and garden were built in the backyard of the residence. This area housed chickens, rabbits, and little goats, stimulating interactions as residents enjoyed engaging with the animals. The garden was also popular, allowing residents to smell and snack on vegetables during the day. Residents participated alongside PSWs and support staff in maintaining the farmhouse and garden, creating opportunities for meaningful activities.

Financial support

Financial support was provided by the public healthcare system to enable residents to remain in their current living environment despite their inability to cover rising costs, thereby preventing relocations in LTC solely due to financial constraints. Financial support was allocated directly to the SR for all residents with an ISO-SMAF profile of 7 or higher, in order to address the increased care and service requirements. The support was calculated as a daily cost of care, based on each residents’ level of independence. Initially, the public healthcare system covered a percentage of this cost – for example, 40% for residents with a profile of 7 and 60% for those with a profile of 8 and higher. However, a small number of residents faced financial difficulties and preferred to relocate in LTC. Consequently, a new financial support scheme was proposed and implemented in October 2023, setting a maximum amount similar to costs in LTC for all residents with profiles of 7 and higher. This ensures that residents pay a uniform amount, regardless of their increasing assistance needs.

Support from the home care services to implement specialized and personalized intervention plans

Through ongoing collaboration between the home care services and the SR, specialized interventions were provided to residents experiencing specific issues such as BPSD, high risks of falls, and pressure sores. When residents required specialized interventions, they were referred to a liaison worker who ensured the request was directed to appropriate clinicians (e.g., occupational therapist, physical therapist, nutritionist, social worker, nurse). These clinicians then contacted the SR to conduct their evaluation and collaboratively implement intervention plans through regular follow-ups. To streamline communications, specific clinicians were assigned to the SR, allowing residents to be consistently supported by the same one or two professionals. Annual evaluations using ISO-SMAF profiles were also conducted by the liaison worker and/or the assigned clinicians to adjust financial support provided by the public healthcare system to residents’ functional autonomy and assistance needs.

Optimized communications to facilitate transitions of care

Collaboration with the public healthcare system also optimized care transitions through better communications and further understanding of each other roles and responsibilities. First, communications following hospitalization were improved, as the project emphasized the need for written feedback to ensure all stakeholders shared a consistent understanding of residents’ independence levels and needs upon their return to the SR. Additionally, other documents were developed through the project to establish a common understanding of the criteria for residents’ return to the SR and the resources they might require. Second, recognizing that a small percentage of relocations in LTC may be unavoidable, the project highlighted the importance of ongoing and robust collaboration between the residence and home care services to facilitate the identification of residents needing relocation, implement interventions to delay or prevent those when feasible, and provide necessary resources while awaiting relocation.

Evaluation of the VCS approach of care

Over the 3-year period, 245 older adults have lived at the SR. Of those, 68.6% were women, with ISO-SMAF profiles varying from 1 to 14, demonstrating a wide spectrum of level of independence. At admission, included older adults were in average 83.4 years old (58–98), and had lived at the residence 834.4 days, ranging from 13 days to more than 19 years. A large number of residents were initially admitted to the SR due to cognitive difficulties hindering their ability to complete daily activities, and need for daily care and supervision.

Evolution of the residents’ functional autonomy profile

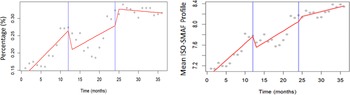

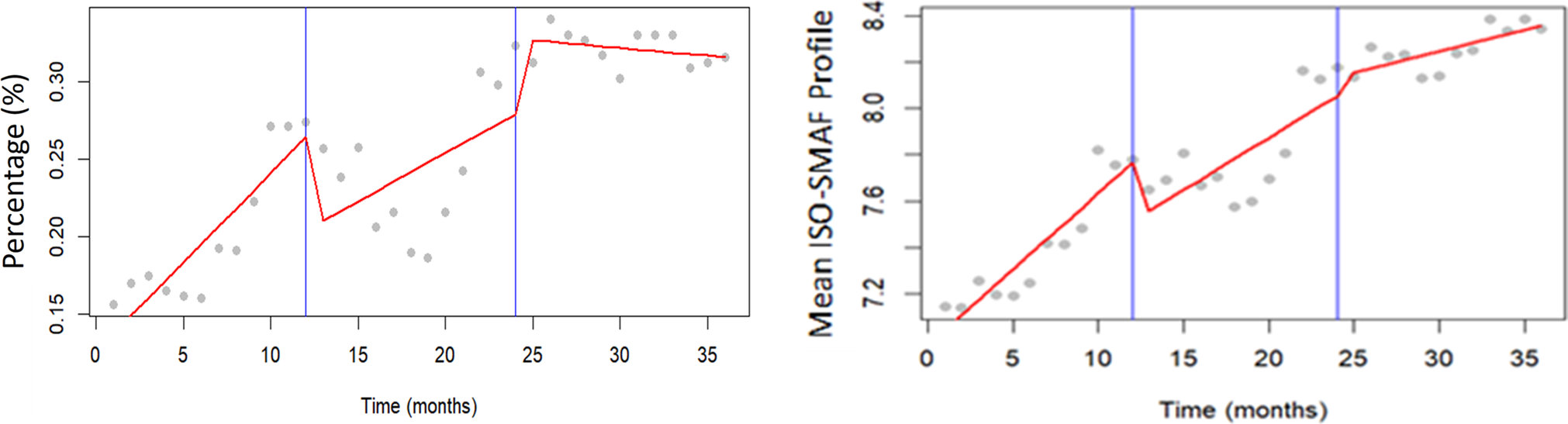

Considering the initial impact of the financial model on the number of relocations, two times of intervention were defined: in September 2022 with the first financial model, and in September 2023, with the second one. As depicted in Figure 3, both the mean ISO-SMAF profile and the percentage of residents eligible for LTC had a positive and statistically significant tendency over the first year, that is, before the first financial model and the VCS approach. In fact, the mean profile increased to 0.07 points (p < 0.001), while the percentage of residents increased to 1.1% each month (p < 0.001). For both variables, the financial model implemented in 2022 had an immediate and negative impact, with decreases in, respectively, 0.25 points (p = 0.0120) and 6.0% (p = 0.0138), justifying the need to change the financial model. Despite the initial negative impact of the first financial model, both variables tended to increase during the second year, though the sustained effect (i.e., compared to the year preceding the implementation) was not statistically significant. As hoped, the change of financial model had an immediate positive and statistically significant impact on the percentage of residents eligible in LTC, with an increase of 4.9% (p = 0.0414), though its impact on the mean ISO-SMAF profile was not significant. Finally, the sustained impact of the second financial model was negative, though small (0.03, p = 0.0621 and −0.7%, p = 0.0358).

Figure 3. Evolution of the percentage of residents eligible in LTC and the mean ISO-SMAF profile during the study.

It should, however, be noted that though the first financial model was implemented in September 2022, discussions with the stakeholders began numerous months before. Consequently, some residents who would have been relocated before the project could have stayed at the SR to allow them to age-in-place. The tendency observed in the year preceding the study could thus have been biased. For example, the percentage of resident eligible in the months preceding the study was around 10%.

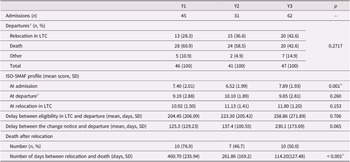

Over the study period, 138 residents were admitted to the SR. As indicated in Table 1, a statistically significant difference was noted between phases regarding the mean ISO-SMAF profile of residents at the time of admission, with a significant difference between Y2 and Y3 (p = 0.007). However, no statistically significant difference was noted at departure, all causes included, though it tended to increase for relocation in LTC, suggesting that residents presented a lower functional autonomy profile at the time of relocations.

Table 1. Admissions and departures of residents by study period

a Departures include all underlying causes for leaving the seniors’ residence, such as relocation in LTC, death, and transfer to another seniors’ residence.

b Significant (p < 0.05).

Ability to prevent or delay relocations in LTC

As presented in Table 1, the results suggest that the VCS approach delayed relocations of an average of 3.5 months between Y1 (the year preceding the VCS approach) and Y3 (the second year of the approach), though the difference was not statistically significant. However, it should be noted that 30 residents currently living at the residence (27%) would have been relocated or waiting for a relocation before the VCS approach. This trend was also observed among residents potentially eligible for relocation to LTC, as the number of days they had an ISO-SMAF profile of 10 or higher before leaving the SR tended to increase during the study, though the change was not statistically significant. However, 33 residents with such a profile were living at the residence at the end of the study for an average of 406.8 days, ranging from 12 days to 8.1 years.

Additionally, the percentage of departures due to relocation in LTC tended to increase over time. Nonetheless, the delay between relocation and death was statistically smaller with the VCS approach of care, with a significant reduction between the year preceding the approach (Y1) and the second year (Y3; p < 0.001).

Overall, the main causes of relocation in the 2-year implementation of the VCS approach included financial limitations from the family (n = 9), aggressive behaviours against other residents and/or with staff during care routines (n = 6), high medical needs such as in palliative care (n = 5), and independence loss, which put the person at high risk of falling (n = 5), and/or requiring two PSWs for transfers (n = 6). Almost 43% of the relocations were requested by the family.

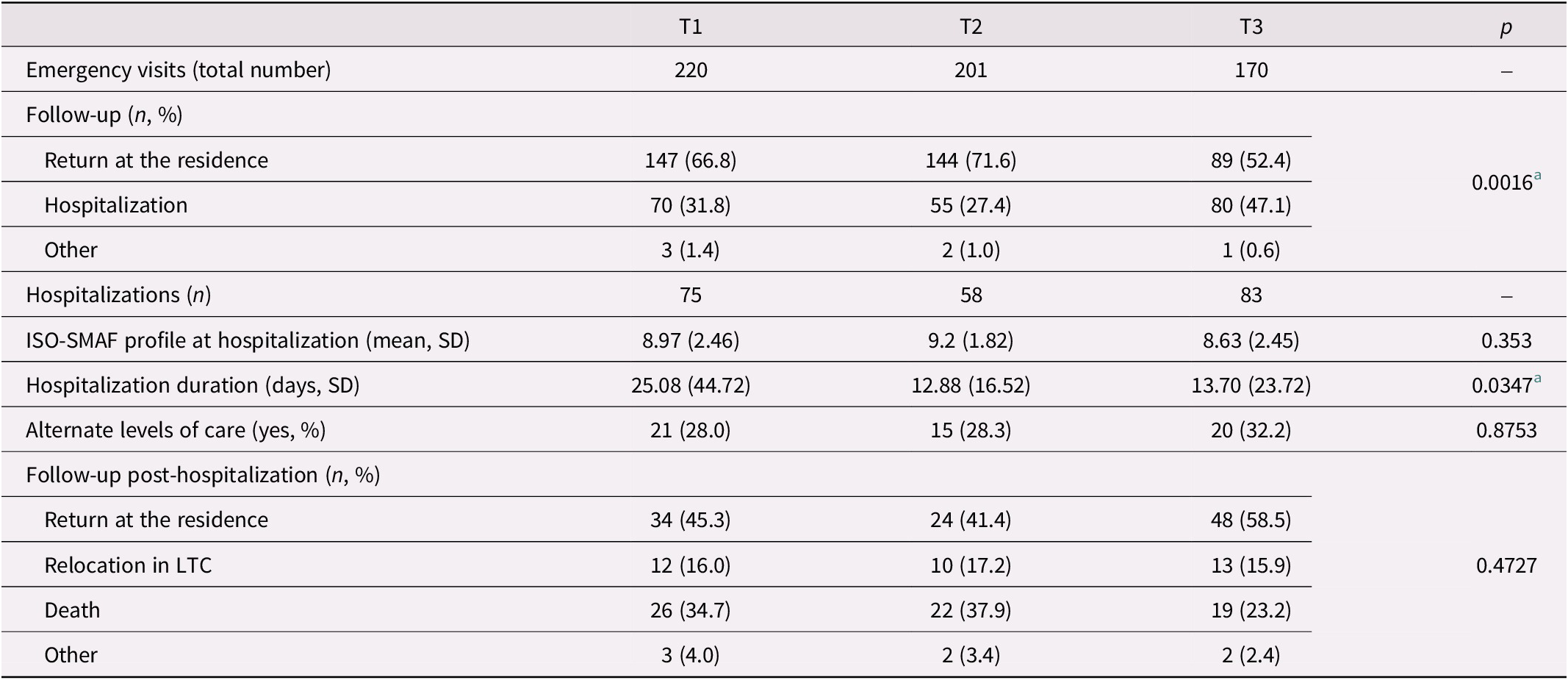

Emergency visits and hospitalizations

As presented in Table 2, the number of emergency visits decreased over the 3 years of the study, though the proportion of residents hospitalized significantly increased in Y3 (p = 0.0016). While the number of hospitalizations remained high, their duration decreased with the VCS approach (p = 0.0697 for Y1–Y2 and p = 0.0625 for Y1–Y3). Moreover, although the difference was not statistically significant, our results suggest that a higher percentage of residents returned to the residence following a hospitalization during the last year compared to the previous two. Interestingly, despite increased relocations during Y3 (n = 20), a similar number of relocations from the hospital was documented throughout the study, suggesting that more residents were transferred to LTC directly from the SR without being hospitalized beforehand.

Table 2. Emergency visits and hospitalizations of residents by study period

a Significant (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Using a LL approach, our team was able to co-develop, in collaboration with the public home care services and a private seniors’ residence, a new approach of care named ‘Vieillir chez soi’ aiming to provide adaptative care, reduce and delay relocations in LTC. Based on best practices (Chmielewski et al., Reference Chmielewski and EDAC2014; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Topfer and Ford2019; Ho et al., Reference Ho, Cheong, Ong, Fusek, Wee and Yap2021; Marquardt et al., Reference Marquardt, Bueter and Motzek2014; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021; Royston et al., Reference Royston, Mitchell, Sheeran, Strain and Goldsmith2020; Voyer & Allaire, Reference Voyer and Allaire2020), this approach promoted a person-centred view of care through the documentation and sharing of residents’ life stories (Grøndahl et al., Reference Grøndahl, Persenius, Bååth and Helgesen2017; Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2020), and staff training to foster more positive and personalized management of BPSD and care (Rijnaard et al., Reference Rijnaard, van Hoof, Janssen, Verbeek, Pocornie, Eijkelenboom, Beerens, Molony and Wouters2016). Care and services were also reorganized to increase staff efficiency while better respecting residents’ previous life habits and preferences (e.g., postpone wake-up time). Moreover, stimulating spaces, such as a small farm, were co-developed to engage residents in meaningful activities. Supported by an ongoing collaboration with the home care services, financial support, monitoring, and specialized interventions were provided within the SR setting. According to our results, this approach of care ultimately allowed the SR to admit older adults with higher assistance needs and maintain them within their new living environment, thus delaying future relocations in LTC.

Results from our study suggest that the approach of care could maintain residents in the SR longer and delay relocations in LTC. Although our results were not statistically significant, it should be noted that residents were admitted with significantly greater assistance needs, including BPSDs. In fact, several older adults would not have been admitted to the SR prior to the study, which may have impacted our results as these individuals were more likely to be relocated afterward. For many residents, waiting at home or in the hospital for relocation to LTC, or paying for an expensive SR, would have been unavoidable due to the lack of acceptable alternatives for older adults with high assistance needs. Furthermore, older adults who were relocated to LTC stayed for significantly less time following the implementation of the VCS approach of care. This finding is particularly relevant as it suggests that for those requiring relocation, the transition to LTC occurred later, that is, significantly closer to the end of life.

Inspired by continuing care retirement communities (Groger & Kinney, Reference Groger and Kinney2007; Shippee, Reference Shippee2009), the VCS approach of care allowed older adults with varying levels of independence to remain within their environment despite loss of independence and increasing assistance needs. In addition to reduce care transitions, which require adaptation through the definition of a new ‘home’ and changes in the level of control (Boubaker et al., Reference Boubaker, Negron-Poblete and Morales2021), our results suggest that the VCS approach may have reduced unjustified healthcare services. Although the number of hospitalizations increased during the study, their duration decreased, as did the number of emergency visits. While residents had overall greater assistance needs, with one third eligible to LTC, several medical issues that previously led to emergency visits could have been managed by the SR. These findings align with previous studies highlighting the potential, but limited, impact of continuing care retirement communities on hospitalizations (Bloomfield et al., Reference Bloomfield, Wu, Boyd, Broad, Hikaka, Peri, Bramley, Tatton, Calvert, Higgins and Connolly2023). Further studies are needed to further document the effects of the care approach on hospitalizations and emergency visits, particularly in light of changes in residents’ independence profiles.

Financial support was pivotal in enabling older adults to age-in-place within the SR. In fact, more than 40% of the relocations were requested by the family, of which a high percentage were due to financial issues. This result is unsurprising as finances are key in selecting a place to live based on the older adults needs (Auriemma et al., Reference Auriemma, Butt, McMillan, Silvestri, Chow, Bahti, Klaiman, Harkins, Karlawish and Halpern2024; Boubaker et al., Reference Boubaker, Negron-Poblete and Morales2021; Roy et al., Reference Roy, Dubé, Després, Freitas and Légaré2018). As highlighted by Auriemma et al. (Reference Auriemma, Butt, McMillan, Silvestri, Chow, Bahti, Klaiman, Harkins, Karlawish and Halpern2024), having the financial resources required to pay for a private seniors’ residence can facilitate more proactive decision making, enabling older adults to choose an acceptable living environment to become their new home. As most relocations due to financial issues happened or were requested following the initial financial model, suggesting its lack of acceptability for residents and their families, a second model was proposed to ensure more control and predictability over financial costs. By ensuring stable costs in the long-term despite loss of independence while proposing overall costs acceptable for older adults and their families, this new financial model enabled residents to select proactively a home where they could potentially stay until the end of their life.

Involving both public and private care providers in a co-development process, this study highlighted the feasibility and relevance of transforming existing resources (i.e., private seniors’ residence) to further embrace the challenges pertaining to providing care to an aging population with complex needs. As resources in LTC are limited, with thousands of older adults currently waiting for their own place, innovative solutions are required to provide safe environments for older adults to live well (Kim & Shin, Reference Kim and Shin2023). Although improvements are still needed to potentially avoid relocations to LTC entirely, the VCS approach of care positions the SR as a suitable environment for older adults who are unable to live independently in the community but do not yet require relocation to LTC, a place they can define as home. Furthermore, by integrating both co-development and evaluation aspects throughout the project, we were able to document obstacles and unplanned results continuously. We were thus able to adjust and adapt interventions accordingly, as exemplified by the new financial model.

While this project had strength such as the strong stakeholders’ involvement in the co-development process, it also had certain limitations. First, the use of the ISO-SMAF profile may have biased the general profile of residents’ autonomy, as evaluations were conducted only once per year or in response to changes. Second, the reliance on change notices to document the number of days relocations were potentially delayed was also subjective. However, since change notices are part of standard practice in SR, using such data allowed us to retrospectively document a key variable. Finally, interrupted time series analysis indicated that the VCS approach of care did not improve the mean ISO-SMAF profile and the percentage of residents eligible for LTC compared to the year prior to the project. Although these results may appear negative, they should be interpreted more positively given that (a) several residents who would have otherwise been relocated remained in the SR during the year preceding the project, thereby increasing the baseline trend; and (b) the project’s goal was not to attain the higher proportion of LTC-eligible residents, but to promote aging-in-place. Consequently, the stabilization of the trend around 33% aligns with this objective, as the SR provides care both for newcomers with lower assistance needs and for long-term residents with increasing loss of autonomy.

Conclusion

Using a LL approach involving both public and private care providers, this project allowed the co-development and evaluation of ‘Vieillir chez soi’, a new approach of care to enable older adults to age-in-place and delay relocations in LTC. Although the approach did not reduce the total number of relocations to LTC, our results suggest that the VCS approach allowed residents eligible for LTC to remain longer in the SR, potentially reduced health services (including facilitating return home after hospitalization or emergency visit), and provided a supportive environment for older adults with varying levels of assistance needs. Through the co-development and implementation of the VCS approach, the SR was able to provide an alternative to LTC for older adults living in the community. Given these initial positive results, further studies are needed to continue refining the care approach, better understand its financial implications for all stakeholders, and explore its application in other settings. In fact, stakeholders from the public healthcare system confirmed the continuation of the VCS approach and the associated financial support, reinforcing the SR’s long-term capacity to support aging in place. Ultimately, we aim to support future SRs adapt their environments to foster engaging and stimulating spaces for older adults, whether in the early stages of illness or with higher levels of support needs, so they can find a home where they feel good and want to live fully.

Acknowledgements

We thank all our collaborators from the private seniors’ residence and the public home care services. We also appreciate the involvement and insightful feedback of Solange Nkulikiyinka and Livia Pinheiro Carvalho on this project. We acknowledge the feedback from the residents and the formal and family caregivers. This project was jointly funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (492219) and the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (339238), as well as the Vitae Foundation and the Research Center on Aging.