Introduction

Proponents of fundamental climate action contend that a radical shift toward a decarbonized world economy can help mitigate global climate risks while unlocking potential for a great surge of development (Chomsky and Pollin, Reference Chomsky and Pollin2020). Massive global investment in low-carbon technologies can trigger feedback loops across the economy and provide the necessary infrastructure for a techno-economic paradigm shift (Mazzucato and Perez, Reference Mazzucato and Perez2023). In that capacity, the climate transition is not merely about radically reducing materials and energy consumption, but also about stimulating growth and redistributing wealth across the world’s population (Chomsky and Pollin, Reference Chomsky and Pollin2020).

However, under conditions of financialized capitalism, financial geographers and political economists question the feasibility of such a transition to a decarbonized world economy (Hickel and Kallis, Reference Hickel and Kallis2020; Baines and Hager, Reference Baines and Hager2022). With global profits accruing primarily through financial channels, mission-oriented investment in the real economy is lagging (Krippner, Reference Krippner2012; Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2021). Besides, global imbalances between Northern and Southern countries and continued resource extraction and commodity production further challenge an inclusive climate transition (Hickel et al., Reference Hickel, Sullivan and Zoomkawala2021). How then can the shift to a green and de-financialized world economy be facilitated? How can institutional, financial, and political barriers be overcome, and what role does the state play in this process?

To address these questions, we engage with neo-Schumpeterian perspectives on de-financialized, innovation-driven green growth (Perez, Reference Perez2003; Kedward et al., Reference Kedward, Gabor and Ryan-Collins2024; Mazzucato and Perez, Reference Mazzucato and Perez2023). First, we introduce a broader conceptual framework on why financializing tendencies in the world economy make it difficult to redirect capital from the financial sector into green investments. Second, we present our de-financialization paradigm and provide examples of how green de-financialization can serve as a global policy direction for tilting the world economy toward sustainability ambitions. Finally, we discuss recommendations to amplify the pace and impact of this transition.

Central to our analysis is that global markets and finance expand beyond their original limits and require state intervention to solve their crises of over-accumulation (Harvey, Reference Harvey2014). De-financialization is understood here as a shift in economic gravity from accumulation through finance to accumulation through the production and trade of socially necessary goods and services, and ‘the re-embedding of finance in a more regulated form’ within the economy and society (Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2021: 1289). It involves reducing the influence of financial markets on economies, shifting from short-term, speculative investments in financial assets to longer-term investments in the productive and green economy, and reducing debt-fueled consumption and asset price inflation as a driver of growth (Christophers, Reference Christophers2015; Norris and Lawson, Reference Norris and Lawson2023). Nevertheless, states operate within a larger capitalist world system and rely on international collaboration to make such transitions happen. Therefore, this article not only focuses on national, macro-economic policy regimes, but also on how these regimes are embedded within an unevenly developed world system where systemic inequalities, competing world powers, and vested interests complicate transitioned-financialization along green lines (Warlenius et al., Reference Warlenius, Pierce and Ramasar2015; Braun, Reference Braun2022; Hickel et al., Reference Hickel, Sullivan and Zoomkawala2021). In doing so, the article embraces green de-financialization as a global policy direction (World Bank, 2012), but also questions the viability of this agenda, not least because continued resource reliance makes it difficult to achieve climate targets even if a new technological revolution is initiated (Hickel and Kallis, Reference Hickel and Kallis2020).

While recognizing that de-financialization is a variegated and uneven process (Aalbers et al., Reference Aalbers, Fernandez, Wijburg, Mader, Mertens and van der Zwan2020; Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2021), we present three broad operationalizations of this paradigm. The first relates to re-embedding finance in the productive, green economy by shifting financial profits into mission-oriented investments contributing to green infrastructures and public value creation (Mazzucato et al., Reference Mazzucato, Kattel and Ryan-Collins2020; Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins, Reference Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins2022). The second is about reforming finance by curtailing unsustainable regimes of corporate governance and restoring global balances so that ecological debts cannot be transferred from core countries to peripheral countries (Hickel et al., Reference Hickel, Sullivan and Zoomkawala2021; Latouche, Reference Latouche2009). Finally, the third operationalization is about restraining finance and imposing limits to unsustainable forms of accumulation, and how this relates to managing climate reparations and economic activity within the balance (Hickel, Reference Hickel2020; Jackson, Reference Jackson2009; Chlebna et al., Reference Chlebna, Evenhuis and Morales2024).

In the next section, we discuss the concept of financialization and how it relates to the Schumpeterian analysis of technological revolutions initiated by Carlota Perez (Reference Perez2003) and Mariana Mazzucato (Reference Mazzucato2021). Thereafter, we discuss Keynesian and Marxian arguments for why such a technological revolution has hitherto not occurred, drawing on Daniela Gabor and Benjamin Braun’s (Reference Gabor and Braun2023) work on the ‘de-risking state’ and ‘green financial regimes’. Finally, we focus on the three operationalizations of our green de-financialization paradigm. Although abstract reasoning is required to develop some of our macro-economic observations, we draw on concrete examples from policy analysis and climate transition studies. We conclude with reflections on theory and practice, and how a global agenda for de-financialized and inclusive green development might be unfurled at a faster pace.

Financialization and the green world economy

Financialization, here understood as a ‘pattern of accumulation in which profit making occurs increasingly through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production’ (Krippner, Reference Krippner2005: 174), has become a key concept for understanding the current expansion in global financial markets. Since the 1970s, many developed and developing countries have stimulated their economic trajectory by injecting debt and liquidity into the economy and liberalizing financial markets (Streeck, Reference Streeck2013). Consequently, economic growth is no longer tied to material production but increasingly to asset classes like stocks, bonds, and real estate (Krippner, Reference Krippner2012; Aalbers et al., Reference Aalbers, Fernandez, Wijburg, Mader, Mertens and van der Zwan2020). However, while debt-fueled investments ultimately contribute to asset price bubbles, financialization actually reinforces, rather than reverses, cycles of declining growth (Mader et al., Reference Mader, Mertens and Van der Zwan2020; Van der Zwan, Reference Van der Zwan2014). Because finance crowds out investment in the real economy, less capital is allocated to productive investments, like renewable energy and green infrastructures (Perez, Reference Perez, Jacobs and Mazzucato2016). While stock markets boom, fixed investment in the economy lags behind (Mazzucato and Perez, Reference Mazzucato and Perez2023).

Hitherto, the relationship between financialization and the global climate transition remain under-researched, although the available evidence suggests that insufficient investment in new technologies restrains potential progress (Chomsky and Pollin, Reference Chomsky and Pollin2020). Joseph Baines and Sandy Brian Hager (Reference Baines and Hager2022, 1053) contend that global asset managers typically seek to maximize short-term shareholder value while disregarding the ‘long-term environmental and social consequences of their operations’. More generally, financialization scholarship demonstrates that investment in financial markets generates higher annual returns than investments in trade, production, or green technology (Knuth, Reference Knuth2018). For that reason, corporate and institutional actors invest in financial assets and commodities, including fossil fuels, rather than in the productive functions of the green economy (Gabor, Reference Gabor2021; Christophers, Reference Christophers2022a). Even when corporations and financial institutions commit to sustainability narratives, it often amounts to symbolic greenwashing rather than structural environmental change (Kenis and Lievens, Reference Kenis and Lievens2016; Braun, Reference Braun2022).

Nonetheless, emerging political economic scholarship argues that financial, tax, and corporate governance reforms can contribute to different state-market entanglements where ‘finance becomes once again a ‘modest helper’ of the real economy’ (see Sweezy, Reference Sweezy1994, as quoted in Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2021: 1289) and no longer seeks growth in unsustainable financial bubbles (Mazzucato and Perez, Reference Mazzucato and Perez2023). Indeed, by redirecting financial investments to mission-oriented sectors of the economy, national and local governments can steer new rounds of global development where de-financialized, productive growth creates transformative synergies across multiple and disparate industries (Perez, Reference Perez, Jacobs and Mazzucato2016: 18). This, in turn, can reduce financial risks and global inequalities as new markets will emerge which trigger ‘dynamic demand for both capital equipment and consumer goods between advanced, emerging and advancing countries’ (Perez, Reference Perez, Jacobs and Mazzucato2016: 18).

This redirecting of finance into the productive economy is commonly associated with long-term business cycles, or technological revolutions (Kondratieff, 1922/Reference Kondratieff1984; Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1939). Carlota Perez (Reference Perez2003) identifies five technological revolutions where finance capital was successfully linked to the productive real economy. The last two revolutions marked the contemporary world economy, where in 1908 Ford’s T-Model launched the automobile age in the United States and the mass production and consumption of oil and plastics, while in 1971 Intel’s microprocessor initiated a revolution in information technology that transformed the social foundations of the world economy.

The transition into a green, decarbonized economy may launch a seventh technological revolution, along with investment in digital technologies and artificial intelligence (Van Meeteren et al., Reference Van Meeteren, Trincado-Munoz, Rubin and Vorley2022). However, Carlota Perez (Reference Perez2003) identifies two necessary stages before a new techno-economic paradigm can become the dominant growth model. During the installation period there is fierce competition when finance capital explores competing technologies, selectively funds emerging entrepreneurs, and overrides existing powers to find the best investments (but see Knuth, Reference Knuth2018). While it is uncertain which technology will mature, finance capital will seek short-term returns in the speculative trade of stocks, bonds, and real estate (Aalbers et al., Reference Aalbers, Fernandez, Wijburg, Mader, Mertens and van der Zwan2020). Therefore, the installation period usually ends in a crash or depression due to reckless investment and inertia from economic sectors to respond to technological changes (Perez, Reference Perez2003). Yet, once the effects of this creative destruction have been realized, possibilities for a new socio-technological order begin to emerge (Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1939).

During the deployment period, ‘the basic infrastructure and technologies of the new paradigm have been installed so that the full growth potential of the revolution [can] be realized across the entire economy’ (Perez, Reference Perez, Jacobs and Mazzucato2016: 10). This is when governments step in to reshape supporting institutions like the welfare state, industrial policy, credit systems, and other institutional innovations (Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2021). The deployment period not only unlocks technological potential across economic sectors but also serves as a fix for capitalism itself (Harvey, Reference Harvey2014). Rather than going through seemingly endless crises and financial bubbles, finance capital gets redirected into mission-oriented outlets providing stable returns with immediate societal impact (Mazzucato and Perez, Reference Mazzucato and Perez2023). In the current epoch, this would look like states, capital, and labor working actively together to build a lasting green macro-economic regime (Gabor and Braun, Reference Gabor and Braun2023).

It follows that after prolonged periods of stagnation and falling profitability, markets and states have a tendency to transform the ecology of capitalism so that a new cycle of technological progress can be launched (Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1939). However, limits to such a technological resurgence surface when we consider the present conditions of financialized capitalism. Due to a glut of global investment opportunities, owners of capital can move money around and ignore the needs for ‘creative destruction’ in productive economies (Harvey, Reference Harvey2014; Haberly and Wójcik, Reference Haberly and Wójcik2022). Additionally, Harry Magdoff and Paul Sweezy (Reference Magdoff and Sweezy1987) observe that stagnation and periodic financial explosions are not necessarily indicating the end of the business cycle but rather have become the business cycle itself. Manuel Aalbers (Reference Aalbers and Aalbers2016) attributes the development of this contradictory phenomenon to the rise of a ‘quaternary circuit of capital’.

Another limit to the resurgence of long-term growth cycles relates to the role of government. Although the state occasionally steps in to rescue capitalism, it may not necessarily do so effectively (Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2025). Following decades of neoliberalization, state priorities have shifted to protecting financial profits over real investments in the productive economy (Harvey, Reference Harvey2014). Globalization and cross-border capital flows make it harder for governments to regulate financial and commodity markets, not least due to increased competition and geopolitical tensions among emerging world powers (Alami et al., Reference Alami, Dixon, Gonzalez-Vicente, Babic, Lee, Medby and Graaff2022; Petry, Reference Petry2024). But even on a national or local level, state interests are often captured by the owners of capital, meaning that the financialization of markets tends to extend into domains of the state (Schwan et al., Reference Schwan, Trampusch and Fastenrath2021; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Brill, Deruytter and Pike2024). Before we introduce our de-financialization paradigm, we must therefore first reflect on these two limits to a global and inclusive climate transition.

Financial obstacles to the green economy

When Joseph Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1939) developed his theory of creative destruction and technological revolutions, he assumed that capitalism was operating under the condition of price-oriented competition. However, Paul A. Baran and Paul Sweezy (Reference Baran and Sweezy1966) demonstrate this is no longer the case because corporations have the ability to squeeze labor profits and artificially boost the capital surplus to rise. Rather than rely on technological innovation to lower prices and stay competitive, corporations can simply maintain price points, and therefore profits, without reinvesting in costly equipment. Therefore, under monopoly capitalism, ‘there will be a slower rate of introduction of innovations than under competitive criteria’ (Baran and Sweezy, Reference Baran and Sweezy1966: 95). This ‘tendency of the surplus to rise’ rather than fall describes financialization at its root. David Harvey (Reference Harvey2014: 260) sees this quasi-monopolistic financialization as a major threat to a global climate transition, where a global rentier class appropriates ‘all wealth and income without paying any mind to production’, and with little incentive to change capitalist modes of production. Inertia is further caused by patents on green innovations which make it difficult to roll-out inventions on a global scale, particularly in the Global South where climate impacts from agriculture, industry, and resource extraction are disproportionally high (Hickel et al., Reference Hickel, Sullivan and Zoomkawala2021; Arboleda et al., Reference Arboleda, Purcell and Roblero2024).

But even for willing companies, Brett Christophers (Reference Christophers2022a) convincingly demonstrates that the investment logic for transitioning to green energy production is weak, and the returns are modest. While governments previously alleviated the capital-intensive nature of renewable energy projects, and subsidized production costs, the result was to stimulate competition, which led to declining energy prices and dwindling margins. A diminishing stock of sufficiently large, investible projects has further contributed to falling investor appetite. Risks to profitability are amplified by the very large capital costs of infrastructure, long payback periods, declining prices, and subsidy supports (Christophers, Reference Christophers2022b). Higher interest rates in the post-QE economy have raised financing costs, which impacts clean energy projects to a greater extent due to their already unfavorable risk assessments by commercial banks.

Aside from monopoly capital and corporate governance regimes, other obstacles to the climate transition must be considered. The previous section explained why a new green institutional compromise requires a coherent techno-economic paradigm because technological revolutions do not unfold spontaneously. Rather, they are contingent on very specific state-market constellations and government policies incentivizing the right, mission-oriented investments, and supporting those investments with broader institutions and regulations. This is where the entrepreneurial state enters the frame to not only regulate markets but also to reshape them in ways that dynamic capabilities can emerge ‘within the context of the pursuit of societal missions’ (Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins, Reference Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins2022: 356). Otherwise, with states taking a more passive, ‘market-fixing’ stance and finance capital primarily investing in what is most profitable, potential for a global and inclusive climate transition will be missed (Christophers, Reference Christophers2022a).

In critical theory, the Schumpeterian state is often conceptualized as an initiator of private competition within, and across, the quasi-public sector (Jessop, Reference Jessop1993). Moreover, it is associated with the demise of the Keynesian welfare state and neoliberalism avant la lettre (Peck and Tickell, Reference Peck, Tickell and Amin1994). Nonetheless, in a truer Schumpeterian sense, the entrepreneurial state is not about ‘de-risking and leveling the playing field but [about] tilting the playing field in the direction of desired societal goals’ (Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins, Reference Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins2022: 421). Therefore, its prime focus is on setting the direction of growth by creating strategic infrastructures and investment policies, which provide the conditions for rapid, technological change.

While potential exists for a new investment cycle in the green economy, such a regime of accumulation also faces entrenched barriers. The first of these is the governance strategy for decarbonization, or the constellation of state-financial institutions, policies, and credit relations that will dictate the speed and nature of transition. At present, Daniela Gabor and Benjamin Braun (Reference Gabor and Braun2023) contend that the de-risking state typifies the main approach. Here, the state avoids the direct provision of green infrastructure and services, in favor of fiscal and regulatory tools (e.g., green bonds, carbon pricing tools, and P3 contracts) to crowd in private finance and enhance the financial viability of investible assets for institutional capital pools. Moreover, the authors argue that the de-risking state overlooks structural issues that constrain the supply of green credit, and the limitations of relying on a private sector-led regime of decarbonization. Open market price signaling and central bank portfolio management are unlikely to deliver a financial system-wide reallocation of capital away from fossil fuel-dependent industries to green tech, while the most profitable corporate bonds and securities will be targeted, disciplinary sanctions for unsustainable investment and financing are weak and environmental costs will be externalized to keep (carbon) prices artificially low (Kedward et al., Reference Kedward, Gabor and Ryan-Collins2022; Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2025).

A second limitation stems from central bank policy. Climate considerations have entered central bank discourses, and many have sought to steer their portfolios toward climate-conscious investments while addressing informational deficits that would allow the proper pricing of climate risks (Thiemann et al., Reference Thiemann, Büttner and Kessler2023). However, it is the financial stability implications of climate change that central banks are concerned with, rather than the environmental impacts per se. Ensuring financial institutions can withstand climate-induced financial shocks and that the (capitalist) global money supply remains intact is their raison d’être. Furthermore, central banks continue to lend directly and indirectly (via QE supports) to fossil fuel-led industries, often without any form of conditionality regarding sustainability (Stephens and Sokol, Reference Stephens and Sokol2023). By adhering to market neutrality principles, they buttress a global financial system that exacerbates climate inequalities, particularly regarding the Global South.

The global capitalist system itself, with its logic of extractive growth and permanent inequality (Hickel, Reference Hickel2020; Spash, Reference Spash2021), is another restricting factor. Within an unevenly developed world economy, green-oriented technological change requires international collaboration to alter global patterns of production, consumption, and innovation (Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2024). Potentially, a global and inclusive climate transition can create trade and service flows to benefit core, semi-peripheral, and peripheral countries (Perez, Reference Perez, Jacobs and Mazzucato2016). Yet, with core countries trading their carbon emissions with the periphery, and profiting substantially from unequal exchange and resource extraction (Warlenius et al., Reference Warlenius, Pierce and Ramasar2015; Hickel et al., Reference Hickel, Sullivan and Zoomkawala2021), such a global economic system is unlikely to materialize (Chagnon et al., Reference Chagnon, Durante, Gills, Hagolani-Albov, Hokkanen, Kangasluoma, Konttinen, Kröger, Lafleur and Ollinaho2022; Nirmal and Rocheleau, Reference Nirmal and Rocheleau2019). Furthermore, competition and trade wars between world powers like the United States, the European Union, Russia, and China, or actual wars in Ukraine and Gaza, demonstrate that geopolitical priorities are not necessarily aligned with ecological goals (Alami et al., Reference Alami, Dixon, Gonzalez-Vicente, Babic, Lee, Medby and Graaff2022; Petry, Reference Petry2024).

Further barriers relate to the speed and depth of the transition required. Jason Hickel and Giorgos Kallis (Reference Hickel and Kallis2020: 480) demonstrate that global finance’s hypothetical commitment to finding profitable solutions in climate transition ‘is unlikely to happen fast enough to respect the carbon budgets for 1.5°C and 2°C against a background of continued economic growth’. Similarly, Clive Spash (Reference Spash2021: 1135) argues that the emphasis on green growth represents little more than political marketing to ‘[reframe] policy within terms that protect and enhance capitalism’. There is in fact strong evidence that renewable energy is not being used to lower material footprints, but rather to spur additional consumption and resource extraction (Jackson, Reference Jackson2009; Latouche, Reference Latouche2009; Dunlap, Reference Dunlap, Batel and Rudolph2021). Furthermore, to build a renewable energy infrastructure, Jean-Baptiste Fressoz (Reference Fressoz2024) deconstructs how the world still relies on the additional burning of wood, coal, and carbon. Gertjan Wijburg (Reference Wijburg2024) associates this counterproductive trend with a regressive cycle of ‘undevelopment’. Despite being the bearer of an unprecedented ‘wealth of nations’, global capitalism has an in-built tendency towards over-accumulation, inequality, debt global imbalance, and ecological destruction (Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2024). In a Polanyian sense, this means that capitalism expands beyond its embedded domains and therefore tends to destroy itself.

Precisely because of these entrenched barriers and challenges, we argue that a radical de-financialization is needed to fundamentally transform the world economy. Only by encouraging green investments and punishing dirty ones can a global and inclusive climate transition be achieved (Chomsky and Pollin, Reference Chomsky and Pollin2020). Otherwise, attempts to save the planet will run into the limits of the de-risking state. Against the odds, a bold and radical turn towards green and de-financialized growth is not unthinkable. The global pandemic demonstrated how quickly states can intervene when under threat. From a different angle, the war in Ukraine and boycott of Russian energy demonstrates how countries like Germany can rapidly ramp up renewable energy production when required. Before going into such details, the next section will briefly foreground the substantive framework of our de-financialization paradigm.

Towards a de-financialization paradigm

Hitherto, we have analyzed the financial complexities surrounding a global and inclusive climate transition. While under competitive capitalism of the nineteenth century such a transitioning was part of recurring installation and deployment periods (Perez, Reference Perez2003), under monopoly conditions of the present age this ‘creative destruction’ of the global economic system has proven to be difficult, not least due to financialization and the myriad ways in which it inhibits meaningful market and state transformation (Harvey, Reference Harvey2014).

Nevertheless, to find a way out of this environment-undermining cycle, we present here the substantive framework for what we call a green de-financialization paradigm. So far, the concept of de-financialization has circulated within housing and financial studies (Christophers, Reference Christophers2015; Stellinga, Reference Stellinga2024, although definitions have not become widespread. By reverting Greta Krippner’s original definition of financialization, Gertjan Wijburg (Reference Wijburg2021: 1289) operationalizes de-financialization as (i) ‘the re-embedding of finance in a more regulated [productive] form’, and (ii) ‘the negation of any form of finance’. While this gives some definitional direction, it also hits a central contradiction. Whereas the first definition entails the ‘taming of financialization’ (Norris and Lawson, Reference Norris and Lawson2023), the second is about curtailing, or even transcending, it. Moreover, there is a Keynesian tradition where regulated finance still has a productive use, and a more critical Marxian tradition where finance is perceived as inherently extractive and unproductive.

Thomas Marois (Reference Marois2021) argues that the social relations underpinning finance are crucial for understanding the spread and depth of both financialization and de-financialization. It is not necessarily about who controls capital and finance (public authorities or private markets) but about the circumstances under which finance is being deployed, and with what democratic purposes. Against that backdrop, we must also consider that finance and financialization are not necessarily equals (Christophers, Reference Christophers2015), and that there’s only financialization when finance is used for the extractive purpose of ‘profiting without producing’ (Lapavitsas, Reference Lapavitsas2014), and particularly in non-financial domains of the economy (Van der Zwan, Reference Van der Zwan2014). Another key point is that financialization becomes manifest through the rent-seeking investments made by financial market actors, global asset managers, and institutional investors. Corporations can also be financialized when they prioritize the creation of shareholder value (e.g., through stock buybacks) over actually earned and socially produced value (van der Zwan, Reference Van der Zwan2014; Dutta, Reference Dutta, Braun and Koddenbrock2022). In climate finance, this translates to hindering innovations by holding onto fossil fuels and not reinvesting corporate profits in sustainable practices (van der Zwan and van der Heide, Reference Van der Zwan and van der Heide2024: 17; see also Dörry and Schulz, Reference Dörry and Schulz2024). Lastly, financialization must be seen as a fundamentally multi-scalar process which on the macro-level manifests itself predominantly in and through global financial and commodity markets. On the meso-level it trickles down to the agency of corporations and governments. On the local-level it becomes manifest in embedded practices of global and local extractivism (Chagnon et al., Reference Chagnon, Durante, Gills, Hagolani-Albov, Hokkanen, Kangasluoma, Konttinen, Kröger, Lafleur and Ollinaho2022).

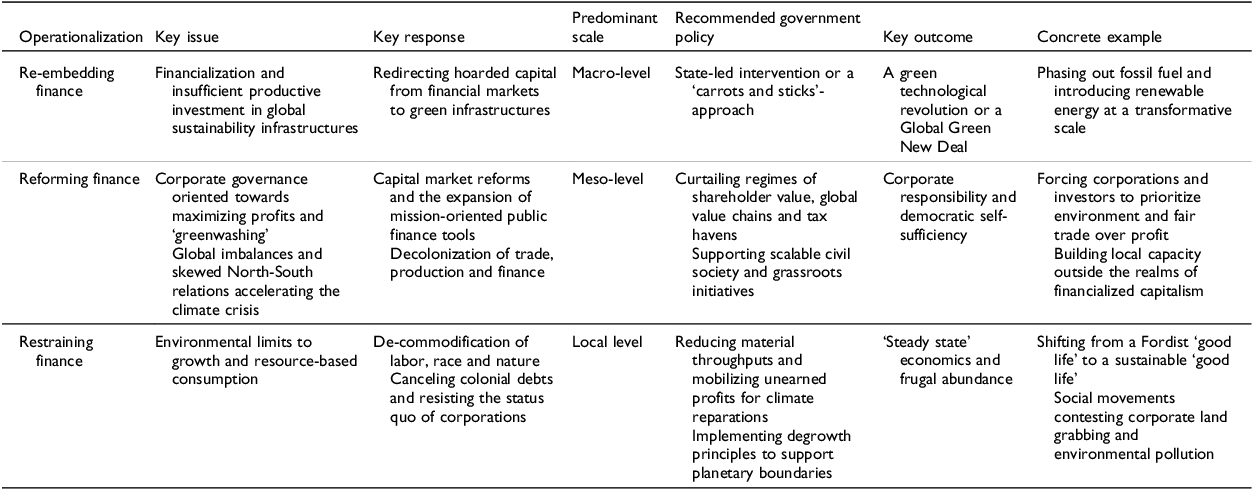

Table 1 presents an overview of how these macro-economic observations are related to our paradigm of ‘green’ de-financialization. The first operationalization refers to the re-embedding of finance within a mission-oriented framework of the productive, green economy. It is Schumpeterian and Keynesian in its analytical scope and aims at targeting credit to democratic interests like climate infrastructure and biodiversity (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence2014). The second operationalization borrows from Keynesian and Marxian perspectives and entails the reforming of finance by curtailing unsustainable corporate governance regimes and restoring global balances and ecological debts. It also refers to stricter public scrutiny and potential modes of re-municipalization and democratic governance. Finally, the third operationalization is about restraining finance and imposing limits to its inherent tendencies to expand beyond socio-ecological domains. This is grounded in ecological economics and relates to managing material throughputs and economic activity within the balance (Hickel, Reference Hickel2020; Chlebna et al., Reference Chlebna, Evenhuis and Morales2024). In addition, it is associated with enforcing climate and debt justice through climate reparation, debt cancelation, and social protests against the hegemony of financial and corporate powers (Perry, Reference Perry2021; Ojeda et al., Reference Ojeda, Nirmal, Rocheleau and Emel2022; Webber et al., Reference Webber, Nelson, Millington, Bryant and Bigger2022).

Table 1. Green de-financialization and its three different manifestations.

Source: Authors’ own

These three operational definitions are mutually inclusive and at times complement or contest each other. For example, the first two operationalizations suggest that through financial market and corporate governance reform, a global and inclusive climate transition can materialize. Yet the third operationalization leans toward a post-capitalist world system where production, consumption, and ‘commodity fetishism’ are radically scaled down (Spash, Reference Spash2021), and the ‘money form of capitalism’ is transcended (Harvey, Reference Harvey2014). In this regard, Sophie Webber et al. (Reference Webber, Nelson, Millington, Bryant and Bigger2022) speak of ‘reparative climate infrastructures’, which can be implemented within a capitalist system but nonetheless shift economic gravity to more democratic and autonomous forms of management and democratic control. Despite these differences, all three operationalizations must be examined to understand the complexities of climate transitioning. In the remainder of this article, we will focus on each aspect of de-financialization and then provide policy recommendations to help them come to fruition.

De-financialization I: Re-embedding finance

Decades of stagnation and financialization have contributed to lagging investment in innovative segments of the productive economy. Rather than stimulating productive gains and cross-sectoral feedbacks, capitalist world dynamics currently revolve around extracting unproductive value from the inflation of asset prices (Adkins et al., Reference Adkins, Cooper and Konings2020). Consequently, mission-oriented engagement to rapidly introduce green infrastructures and sustainable modes of production is low compared to previous technological revolutions. Capital’s profitability expectation is one reason for lagging investment (Christophers, Reference Christophers2022a). Government’s rather passive role is another. Although the de-risking state utilizes green industrial policy to identify ‘strategic industrial sectors where it wants to promote capital investment’ (Gabor and Braun, Reference Gabor and Braun2023: 2), it primarily does so by tweaking risk-return profiles in favor of capital interests. Moreover, the implementation of quantifiable emission targets (e.g., a reduction of 45 percent by 2030), or the phasing out of polluting industries, is not on the political agenda (Gabor and Braun, Reference Gabor and Braun2023). This is problematic because markets themselves do not steer towards socially-needed end results (Chomsky and Pollin, Reference Chomsky and Pollin2020). Central banks further encourage this inertia by narrowly focusing on monetary stimulus and market neutrality, while overlooking more interventionist measures, like a green fiscal stimulus (Thiemann et al., Reference Thiemann, Büttner and Kessler2023).

If the current de-risking economy cannot provide the needed infrastructure for green de-financialization, a state-orchestrated ‘mission economy’ becomes a desirable alternative (Mazzucato and Perez, Reference Mazzucato and Perez2023). Against this background, we recommend a set of policy changes which radically break with de-risking and market neutrality, and advocate for what Katie Kedward et al. (Reference Kedward, Gabor and Ryan-Collins2022) call an ‘allocative green credit policy regime’. Instead of using price signaling, de-risking, and monetary dominance as the principal decarbonization strategy (Thiemann et al., Reference Thiemann, Büttner and Kessler2023), we call for a state-led industrial policy directing credit to priority sectors and reshaping market characteristics along de-financialized, green lines (see also Lawrence, Reference Lawrence2014). Much like green Keynesianism, such an allocative credit policy is therefore (i) dictated by the priorities of greening (public) infrastructure, (ii) disciplining dirty sectors and market-based finance, and (iii) involving central banks to play a promotional (rather than prudential) role.

In the best-case scenario, this agenda of green de-financialization is implemented at the supranational level, where collaborating green states collectively reshape financial markets around principles of public value creation and global sustainability (Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins, Reference Mazzucato and Ryan-Collins2022). In doing so, we see potential to dismantle offshore financial networks, introduce new wealth taxes, and redirect public and private resources from dirty or financial sectors to investments in cleantech and renewables (Chomsky and Pollin, Reference Chomsky and Pollin2020). As the climate crisis worsens, green states can also discipline private capital by (i) introducing more absolutist forms of state ownership, (ii) expropriating carbon assets, and (iii) enforcing harder emission caps. Rather than making green innovations ‘investible’ for private capital (Taggart and Power, Reference Taggart and Power2024), such green states thus intervene in the functioning of markets while also allocate an increasing percentage of global GDP to industrial policy favoring green infrastructures, resource efficiency and climate mitigation (Chomsky and Pollin, Reference Chomsky and Pollin2020). Alternatively, when fiscal regimes are tight, they can provide Public Sustainable Finance to publicly controlled Climate- and Transformation funds and crowd in private investment under mission-oriented guidelines (Golka et al., Reference Golka, Murau and Thie2024). Tax neutral innovation policy is another instrument to incentivize green development. For example, a land value tax system rewarding ecological innovation and labor, but penalizing pollution and rent extraction from unimproved land, can shift economic decision-making from pursuing quick and dirty profits to realizing sustainable and intangible growth (Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2025).

However, a ‘Global Green New Deal’-like approach only works when collaborating nation-states have the capacity and political willpower to do so. Therefore, we acknowledge that a more pragmatic stance on the green, de-financialization paradigm is also needed, not least to forge complex institutional compromises across economic sectors and stakeholders (Gabor and Braun, Reference Gabor and Braun2023). Rather than merely risk-proofing private and institutional investment, we propose a holistic ‘sticks-and-carrots approach’ where financial markets are both incentivized and disciplined to finance green investments (Kedward et al., Reference Kedward, Gabor and Ryan-Collins2024). This requires greater coordination between monetary, fiscal, and credit policy so that every regulatory and planning tool within the state apparatus is used to change global market directions (Stephens and Sokol, Reference Stephens and Sokol2023). For example, while green bonds, green investment funds, and carbon offsetting platforms have grown exponentially, we propose more aggressive forms of ‘green quantitative easing’ to phase out asset purchases connected to carbon-led industries and tilt the market into a more decisive, green direction (Dafermos et al., Reference Dafermos, Nikolaidi and Galanis2018). In addition, central banks could offer preferential interest rates to renewable-led industries, while imposing higher capital requirements and leverage ratios on lenders to polluting industries. They could also mandate credit allocations to sectors that require enhanced access to green capital. For example, a percentage share of mortgage lending could be mandated into retrofitting programs (Kedward et al., Reference Kedward, Gabor and Ryan-Collins2022), as well as a percentage of institutional investors’ portfolio holdings.

On the flipside, we contend that stronger regulations and transparency in the ESG ratings market are required to ensure providers do not over-inflate the sustainability profile of companies and therefore internalize rather than externalize climate costs (Thiemann et al., Reference Thiemann, Büttner and Kessler2023). For example, the European Union has proposed new rules requiring the authorization and supervision of ‘Environmental, Social and Governance’ (ESG) ratings providers, and fines of up to 10% of net turnover for noncompliance (Jones, Reference Jones2024). A stronger policing of assets within institutional investors’ portfolios, and the mandatory exclusion of assets linked to polluting industries, could prompt greater levels of divestment while new transparency commitments forces pension providers to issue information on whether their funds are invested in fossil fuel industries and provide clients with alternatives (In and Schumacher, Reference In and Schumacher2021). Restricting the use of fossil fuel assets as collateral, and the securitization of loans linked to fossil fuel industries, could reduce polluters’ ability to leverage their existing assets to access credit (Kedward et al., Reference Kedward, Gabor and Ryan-Collins2022). We also consider it critical that any ‘green’ financial market regulation aligns with overarching state-led industrial policy so that capacity-building investment is promoted in those economic sectors where the global stock of capital is currently not well-positioned.

Nonetheless, amid a world economy characterized by shifting geopolitical interests and political volatility, it cannot be denied that even the sticks-and-carrots approach faces challenges (Alami et al., Reference Alami, Alves, Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner, Koddenbrock, Kvangraven and Powell2023). For example, following the concern for new economic priorities, the United States is now actively rolling back its green ambitions and environmental regulations. Although China is legitimately perceived a ‘big green state’ for its state-led investment in renewable and green technologies (Gabor and Braun, Reference Gabor and Braun2023), Mathias Lund Larsen (Reference Larsen2024) rightly observes that many of its climate targets are not in line with the Paris agreements. Besides, China remains a big consumer of coal and applies in its overseas investments the lowest environmental standards possible (Larsen, Reference Larsen2024).

Despite these barriers, we recognize that a green, de-financialization paradigm can still be implemented. Once the rising costs of environmental degradation and finite fossil fuels are no longer economic, even the least climate-friendly national government will have no choice but to coordinate at least a socially destructive form of ‘carbon shock therapy’ (Gabor and Braun, Reference Gabor and Braun2023). Trade wars and tariffs, although not driven by green priorities per se, may eventually lead to the dismantling of global supply chains, which in turn will lower global emissions through lesser consumption, or through less transport-dependent local production. This is not to say that a coordinated climate transition will necessarily and always happen. Rather it is that capitalism ultimately relies on a socio-ecological fix to reproduce itself. Otherwise, too many stranded assets will lose their value without alternative investment options. David Harvey (Reference Harvey2014: 255) notes that capital also thrives upon environmental disasters and turns catastrophe into a business opportunity serving as a ‘convenient mask to hide its own failings’.

De-financialization II: Reforming finance

Secondly, on the meso level, obstacles to a de-financialized, green economy are deeply engrained in corporate governance regimes and networks. Private companies maximize shareholder value and therefore respond slowly, if at all, to socio-ecological challenges (Baines and Hager, Reference Baines and Hager2022). At the same time, financial supervisors often lack regulatory powers to enforce global sustainability standards. A clear barrier to financing the green transition is the operation of vested interests in setting the ESG agenda, and shaping how green assets are defined, quantified, and priced (Langley et al., Reference Langley, Bridge, Bulkeley and Van Veelen2021). In other cases, industry lobbying has sought to minimize the political risks associated with regulatory expansion. The literature on regulatory capture highlights the importance to corporate actors of cultivating access to policymakers to influence regulatory standards and define what assets may be deemed green-investment worthy. Benjamin Braun (Reference Braun2022) outlines how corporate interests often walk a political tightrope between ensuring they do just enough on environmental stewardship to satisfy progressive demands while minimizing actions that might aggravate conservative interests. For example, he points at the regional variation in the shareholder voting patterns of BlackRock, who supported 87% of shareholder proposals on ESG in Europe but voted against 84% of proposals in North America.

The introduction of greater accountability and stronger corporate governance is key for the green de-financialization paradigm. The current asset manager model relegates corporate governance to a secondary concern that is considered only to the extent that it impacts asset values, fee income, and profitability (Baines and Hager, Reference Baines and Hager2022). For that reason, we plead for incorporating ecological goals and resource constraints into market regulations and corporate governance or ESG-inspired models (Jackson, Reference Jackson2009). Ideally, supranational institutions like the World Trade Organization would enforce these regulations, thereby evening the playing field for developing countries and emerging market economies (Hickel, Reference Hickel2020, see also next section). In addition, there is a necessary role for public purpose alternatives to asset managers, including employee equity ownership trusts, activist shareholders, or government-owned shares, that would provide a stronger collective voice in corporate governance decisions within large companies (Palladino, Reference Palladino2022). Katie Kedward et al. (Reference Kedward, Gabor and Ryan-Collins2022) present a convincing case for restricting corporate greenwashing through ‘regulatory arbitrage’. Indeed, with almost unrestricted access to shadow banking systems, private equity and hedge firms have access to off-balance sheet financing structures, making it difficult to penalize them for dirty investments (Haberly and Wójcik, Reference Haberly and Wójcik2022). A return to a bank-based financial system where assets stay on the balance sheets of corporations may therefore be desirable (Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2025).

Of course, in the absence of greater market reforms, we assert that upscaling noncommercial forms of finance could be an alternative strategy to constituting green de-financialization (Block, Reference Block2014, McCarthy, Reference McCarthy2019). Reducing the power of ‘too big to fail’ banks and developing de-centered, locally oriented forms of finance could help develop more sustainable forms of economic growth. There is a long history of nonprofit lending within capitalism, both through credit unions and mutual banks, who have a strong record of performance at addressing financing gaps in under-served communities and sectors (Lawrence, Reference Lawrence2014).

Although in recent decades many public and cooperative banks have been coaxed into serving private sector interests (Mertens and Thiemann, Reference Mertens and Thiemann2019), their combined resources still account for a quarter of all banking assets, or almost $35 trillion (Marois, Reference Marois2017: 4). Therefore, Thomas Marois (Reference Marois2017) contends that they are better suited for financing the operational strategies of green transformation than their commercial counterparts. Pointing at the efforts of Costa Rica’s Bank of Popular and Community Development and Germany’s Reconstruction Credit Institute, he demonstrates that public banks can prioritize social goals over private profits and take (i) the lead in developing innovative, green, supportive lending, (ii) promote a public ethos around a just, green future and (iii) build internal expertise to support transformation. In theory, such a ‘public mission’ approach also applies to sovereign wealth funds and state-owned enterprises that own trillions of assets worldwide (Clifton and Díaz Fuentes, Reference Clifton and Díaz Fuentes2023). Besides, through sharing risks and rewards with the private sector para-public entities can create multiple public benefits (e.g., revenue streams and co-ownership of green infrastructures) which de-risking approaches typically do not offer (Gabor and Braun, Reference Gabor and Braun2023). Alternatively, Jan Fichtner et al. (Reference Fichtner, Schairer, Haufe, Aguila, Baioni, Urban and Wullweber2025) acknowledge the ‘channels of influence’ through which sustainable finance can change global corporate practices.

Building up a significant nonprofit banking sector to invest in community-led energy projects and local infrastructure at lower or forgivable rates of interest is another key step toward a green, de-financialized paradigm. Serge Latouche (Reference Latouche1993) contends that in the developing world, roughly two thirds of the economy is run by informal entrepreneurs and self-sustaining communities with little access to global financial systems. Without subsuming these communities into private debt (Mader, Reference Mader2018), we recognize ‘reparative climate infrastructure’ as an emerging phenomenon to spearhead an eco-friendlier, democratization of banking, ownership, and control (Webber et al., Reference Webber, Nelson, Millington, Bryant and Bigger2022). Sophie Webber et al. (Reference Webber, Nelson, Millington, Bryant and Bigger2022: 940), for that matter, identify numerous not-for-profit projects funded to support the socio-ecological transition, including a labor-owned electricity cooperative in Australia, the re-municipalization of water supply in Brazil, and Indigenous carbon offsetting projects in Northern Australia and California. Such interim projects are crucial until more substantial and ambitious policies or regulatory tools are available. They can also be used to scale up capacity-building in economic sectors that are traditionally underfunded (Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2025).

Nonetheless, it is undeniable that systemic power disparities and global imbalances slow down a global and inclusive climate transition in various ways. A new green, de-financialized paradigm must therefore also address the skewed North-South relations that perpetuate the ever-worsening climate crisis. Indeed, colonialism, unequal exchange, and rapacious extractivism have resulted in persistent patterns of combined and uneven development fueling environmental degradation through the ‘development of underdevelopment’ (Bond, Reference Bond2013; Hickel, Reference Hickel2020). Decolonizing international trade and corporate law, introducing fair market prices, curtailing the power of global supply chains, and prohibiting the over-exploitation of land, resources, and labor are just a few interventions needed to restore global balance (Alami et al., Reference Alami, Alves, Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner, Koddenbrock, Kvangraven and Powell2023; Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2024). The cancelation of debt, and particularly the surcharge debts of Global South countries, is a further proposed mechanism that would alleviate the pressures on developing countries to further exploit their natural resources and rebalance the costs of climate-related debts (Perry, Reference Perry2021). Jason Hickel (Reference Hickel2020: 237–240) proposes altering colonial institutions (e.g., tax havens and offshore financial centers) and using forfeited revenue streams to pay climate reparations. In the best-case scenario, such efforts also counteract environmental injustices. Indeed, the concept of ‘ecological debt’ reveals how core countries often hypocritically lower their material emissions by outsourcing them – including their direct environmental impacts – to peripheral countries (Chagnon et al., Reference Chagnon, Durante, Gills, Hagolani-Albov, Hokkanen, Kangasluoma, Konttinen, Kröger, Lafleur and Ollinaho2022; Nirmal and Rocheleau, Reference Nirmal and Rocheleau2019).

Even so, with geopolitical interests increasingly shifting beyond aid, we recognize that such world transformations are difficult to coordinate (Mawdsley, Reference Mawdsley2018; Alami et al., Reference Alami, Alves, Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner, Koddenbrock, Kvangraven and Powell2023). This is all the more true when considering that in the current ‘bond-age’ developing countries are often taken advantage of by international banks and institutional investors (Perry, Reference Perry2021). Despite these barriers, Mathias Lund Larsen (Reference Larsen2024: 158) sees unexpected potential for green, albeit suboptimal, de-financialization. Analyzing the de-risking paradigms of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the United States’ Partnership on Global Infrastructure and Investment and the European Union’s Global Gateway, he asserts that developing countries can strategically ‘pick and choose… [climate financing] that shape their ability to use green state tools’. Accordingly, he asserts that they can ‘simultaneously provide a guarantee to de-risk a project to work with the US to mobilise private capital, receive concessional financing for a project from the EU, and take sovereign-backed loan from China to build a Chinese SOE-led project’ (Larsen, Reference Larsen2024: 159). For other funding gaps, we hear the call for an ‘SDG Stimulus Fund’ counterbalancing challenging market conditions like (i) limited access to capital, (ii) high costs of borrowing, (iii) debt distress, and (iv) severe poverty (Sachs et al., Reference Sachs, Lafortune, Cattaneo and Fabregas2023), but also emphasize the enlightened self-interest of core countries to fund climate reparations in the developing world.

De-financialization III: Restraining finance

Thirdly, orchestrated government actions are required to restrain finance and fundamentally change its role in perpetuating existing modes of production (Hickel, Reference Hickel2020). In a post-Fordist context, global production remains dominantly resource-based which is problematic when considering increasing demand at the global level (Latouche, Reference Latouche2009; Hickel and Kallis, Reference Hickel and Kallis2020). Therefore, we contend that government policy should not focus on one-sidedly promoting the decarbonization of global production (Dafermos et al., Reference Dafermos, Nikolaidi and Galanis2018). Across the entire value chain it should promote circular and green innovations which help to ‘preserve and enhance natural capital, optimize resource yields, and minimize system risks by managing finite stocks and renewable flows’ (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2016: 46). In aggregate, such a shift away from planned obsolescence may decrease initial growth due to declining nominal output and longer product life cycles. Yet, it will also compensate for falling growth by adding new jobs in maintenance, recycling, waste management, and product sharing (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2016).

The promise of such a circular economy is that perpetual growth remains possible due to a radical altering of global lifestyles and consumption (Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2024). Fordism promised the good ‘American Life’ with suburban housing, cars, and mass-produced goods, which is unsustainable due to excess (energy) consumption and planned obsolescence (Latouche, Reference Latouche2009). The new ‘good life’ of the green economy favors custom-made goods, sustainable design, renewable materials, and product circularity and sharing (Perez, Reference Perez, Jacobs and Mazzucato2016: 14). Nevertheless, the net gains of such energy-efficient lifestyles are often used to consume more (Jackson, Reference Jackson2009). Besides, even green and sustainable consumer goods or infrastructures (e.g., electric cars and solar panels) require raw materials (Dunlap, Reference Dunlap, Batel and Rudolph2021). In this regard, we recommend far-reaching policies to forcibly reduce consumption in advanced economies, including the phasing out of ‘dirty’ sectors and a ban on the planned obsolescence of products (i.e., intentionally designed products that require replacement), mandating a lengthening of warranties and product guarantees, and enforcing a ‘right to repair’ on household appliances and technological devices (Hickel, Reference Hickel2020). In theory, knowledge-intensive services can also be optimized with machine learning and artificial intelligence that focus on the economizing of intangibles and digital transformation (Van Meeteren et al., Reference Van Meeteren, Trincado-Munoz, Rubin and Vorley2022).

However, to the extent that absolute and relative decoupling from material emissions remains challenging (Hickel and Kallis, Reference Hickel and Kallis2020), we concur with degrowth scholars that besides re-embedding and reforming finance, finance must also be restrained (Spash, Reference Spash2021; Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2024). Rather than financing ever more growth and accumulation, we embrace the idea of ‘frugal abundance’ (Latouche, Reference Latouche2009), which can be defined as an ‘essential balance between material, relational, and spiritual needs of all humans’ (Plomteux, Reference Plomteux2024). In exchange for consuming and producing less, Tim Jackson (Reference Jackson2009) contends that people can also work less and spend more time creatively or in the community. Yet, besides requiring a fundamental restraining of finance and commodity markets, such a global economic system also requires a radical redistribution of global wealth (Hickel, Reference Hickel2020). After all, in future degrowth-led society, economic policymakers can no longer resort to growth to fix crises of inequality or global imbalance (Daly, Reference Daly1974).

In the current political conjecture, we recognize that the execution of such a radical political project seems abstract at best (D’Alisa and Kallis, Reference D’Alisa and Kallis2020). However, there are other ways to encourage the transition towards a green and de-financializing world economy. With social movements and environmental groups causing controversy among democratic voters and electoral groups, we recognize that it is difficult to put degrowth objectives on the political agenda. Even so, by openly challenging the ‘commonsensical’ ideas of political society through engagements in civil society, Giacomo D’Alisa and Giorgos Kallis (Reference D’Alisa and Kallis2020) contend that social progress can still be made, one step at a time. In this regard, it must not be forgotten that even in the least climate-friendly countries, a significant share of voters and consumers still favors progressive market change (Hickel, Reference Hickel2020). Eventually, it is also in the greater interest of corporations and financial lenders to ensure that their businesses are adhering to global sustainability and social responsibility. After all, reputational damage and customer boycotts can lead to drastic declines in financial profit and global market share.

Political movements advocating for de-commodification in developing countries could become another key, albeit somewhat contested, ally in reforming unsustainable practices. Padini Nirmal and Dianne Rocheleau (Reference Nirmal and Rocheleau2019: 465) illustrate how Indigenous groups in Mexico and southern India are actively ‘building economies and ecologies of resurgence while simultaneously resisting growth’. Similarly, Diana Ojeda et al. (Reference Ojeda, Nirmal, Rocheleau and Emel2022: 155) highlight how various social movements across Latin America and Africa, often led by Indigenous women, are effectively resisting corporate land grabs and environmental injustices. The key point here is not that social movements can bring down the hegemony of corporate agriculture and mining. Rather, it is that they reveal how local struggles are embedded in globally integrated ‘commodity- and/or consumption webs’ (Nirmal and Rocheleau, Reference Nirmal and Rocheleau2019: 482). In that capacity, they raise awareness on how seemingly innocent consumption in the Global North not only sustains, but potentially also alters, environment-undermining practices in the Global South. This resonates with Nick Bernards’ (Reference Bernards2024) observation that de-financialization cannot be reduced to reforming financial markets but should instead also address how capitalism fundamentally exploits labor, race, and nature.

Rather than solely trusting on climate movements and consumer behavior, we also point at additional socio-spatial strategies that can be implemented at various levels of the political process. New approaches to urban planning and development are emerging, particularly where local and state governments lack guidance on the implementation of de-financialization and climate neutral policies (Istrate et al., Reference Istrate, Popartan, Auerbach, Gaspari and Tavangar2023). For example, the European Union aims to deliver 100 climate neutral cities by 2030 to act as innovation hubs to showcase the climate-neutrality concept and support wider institutional and cross-sectoral change. However, such an objective will be difficult to deliver, not least because cities require comprehensive support and guidance on implementation (Huovila and Westerholm, Reference Huovila and Westerholm2022), and must overcome multiple complexities related to governance issues, including policy fragmentation, financial and organizational risks, and the potentially conflicting financial interests of development stakeholders (Waldron, Reference Waldron2019). Maria Kaika et al. (Reference Kaika, Varvarousis, Demaria and March2023) identify five steps on overcoming such barriers and paradigmatic challenges: (1) grounding current degrowth debates within their historical-geographical context; (2) engaging (planning) institutions; (3) examining how urban degrowth coalitions can be scaled up without co-optation; (4) implementing degrowth principles into everyday urban practice; and (5) prefiguring how degrowth agendas can confront the diverse and unequal urban social relations and uneven outcomes in the Global North and South.

In conclusion, we assert that new forms of citizen participation and engagement in policymaking processes are also emerging to further enable the green de-financialization agenda. Citizen assemblies or the participatory budget experiments developed in Porto Alegre, Brazil, where local assemblies of citizens gather to debate, negotiate, and ultimately vote on how to allocate public money, is just one key example (Baiocchi and Ganuza, Reference Baiocchi and Ganuza2014). Citizen juries are another possible mechanism for managing local financial flows through representative bodies chosen from local constituencies (McCarthy, Reference McCarthy2019). Such bodies serve a mandatory term and act as trustees in the management of public finance and ecological transition goals. Such forms of participation would ideally yield innovative forms of local governance to drive inclusion, diversity and spatial justice across sustainable transport, housing, energy and urban ecology. Moreover, by prioritizing public needs over financial returns, they can become an indispensable pillar of a de-financialized and green world economy, even when global capitalism itself is not yet ready for it.

Conclusion

In this article, we argue that the current form of financialized capitalism represents a significant barrier to achieving a global, inclusive climate transition. Financialization, which valorizes growth through financial speculation rather than production, has created a disconnect between capital markets and the real economy that diverts investment away from the green technologies and infrastructure necessary to address the climate crisis. In response, our argument for a green de-financialization paradigm would shift the focus of economic systems from short-term, profit-driven financial gains to long-term, mission-oriented investments that prioritize socio-ecological well-being. However, such a transition requires states to play a proactive role in shaping the necessary policies, regulations, legislative frameworks, fiscal subsidies, and incentives to redirect capital into productive investments in renewable energy, decarbonization, and sustainable infrastructure.

Our primary contribution is to broaden the scope of the de-financialization literature (Christophers, Reference Christophers2015; Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2021) by situating it within the context of green development and the climate transition, and by emphasizing the critical role of financial sector reform in achieving a sustainable and inclusive economic transition. In so doing, we advance three operational strategies necessary for the roll out of a green de-financialization paradigm: re-embedding finance in the productive economy, reforming unsustainable corporate governance practices, and restraining finance’s influence on resource exploitation. The first of these calls for redirecting financial profits into productive investments that contribute to public value, such as renewable energy projects and sustainable infrastructure. The second emphasizes the need to address global imbalances, particularly the ecological debt owed by Northern countries to the Global South. Indeed, a de-financialization agenda must ensure equitable access to green technologies and sustainable development opportunities for all nations. The third operationalization focuses on shifting global lifestyles and consumption patterns and addressing the policy adherence to perpetual growth and resource-based accumulation that underpin the financialized economy. In making these arguments, we further draw on neo-Schumpeterian and Keynesian perspectives to emphasize the state’s role in regulating financial markets and steering the economy toward long-term green development, and we challenge dominant market-led policy narratives, like ‘state de-risking’, which have proven insufficient in mobilizing the necessary investment for decarbonization.

The examples we discuss throughout the article demonstrate the extent of the challenge to fix or transcend global capitalism, save the planet, and reorganize human life in more sustainable ways. Therefore, we emphasize that states must not merely focus on correcting market mechanisms but become actively involved in steering socio-ecological change across the world economy. The impact of such a transformative approach will strongly depend on the agency of capital as well as on the allocation of finance to the green economy (Harvey, Reference Harvey2014). For that reason, a global and inclusive climate transition is as much technological as it is political: vested interests and competing policy regimes currently inhibit a coordinated transition toward global sustainability (Bond, Reference Bond2013).

Neither the de-risking state nor central banks deploy the right tools to combat ecological disaster. Decade-long quantitative easing and public debt creation have triggered various financial bubbles, but mission-oriented, green investment is still lagging (Mazzucato and Perez, Reference Mazzucato and Perez2023). The de-risking of investments by already rich corporate and institutional actors exhausts public capacity to fund the green economy directly through fiscal stimulus. Yet, the failing of macro-economic structures is not the only problem we encounter in studying the challenges of a global and inclusive climate transition (Kenis and Lievens, Reference Kenis and Lievens2016; Dörry and Schulz, Reference Dörry and Schulz2024). Even when such obstacles can be overcome, it is questionable whether technological change will arrive on time. Climate scientists already report that several critical ecological tipping points have been exceeded. Global demand in emerging economies further inhibits ability to reduce energy use to net zero levels (Jackson, Reference Jackson2009). Within the status quo of global de-risking, it is therefore challenging to accomplish any kind of climate transition through orchestrated planning or inter-state governance. More likely it will be delayed by flawed and imperfect market mechanisms. In an extreme event, it can, however, be enforced through an unnecessary painful and anti-social carbon shock therapy (Gabor and Braun, Reference Gabor and Braun2023: 25–28).

A global and inclusive climate transition is difficult to accomplish. Attempts to de-risk green investments are not coercive enough to force capital switching from financial markets to the green economy (Gabor and Braun, Reference Gabor and Braun2023). Due to central banks’ market neutrality, monetary and fiscal interventions have remained limited. But neither is the market sufficiently responding to the climate crisis, instead embracing a slow transition where the factoring in of climate costs and risks is minimal. With the climate crisis worsening every day, it becomes apparent that a radical call to action is needed. De-financialization can align finance and corporate interests with the green transition and tilt the playing field in the direction of desired social goals (Mazzucato et al., Reference Mazzucato, Kattel and Ryan-Collins2020). In addition, it can mobilize a sheer amount of public funds (through taxation, expropriation of carbon assets, or otherwise) and encourage state-led industrial policy and green stimulus as alternative to the de-risking of conservative fiscal regimes.

Within the unevenly developed world-system, this also means that core capitalist countries need to allocate more resources so that peripheral countries can transition evenly, while simultaneously raising domestic living standards (Jackson, Reference Jackson2009; Hickel, Reference Hickel2020). By adhering to global emission targets and addressing unequal exchange, governments in the Global North can reduce levels of domestic consumption without necessarily altering capital flows to the Global South (Latouche, Reference Latouche2009). Either way, deliberately contracted degrowth might risk a global economic depression, leading Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin (Reference Chomsky and Pollin2020: 116–124) to argue for a delicate balance between the degrowth of polluting, nonproductive sectors and the stimulation of green growth sectors. The latter is also important to ensure mass employment and the required social provisioning needed for the green economy of the future. Still, a radical reorientation towards a post-growth economy where resource-based accumulation is not the leading driver of social progress might be advisable (Wijburg, Reference Wijburg2024). Ultimately, on a planet with a dynamic world population, the consumption of finite resources must stay within the socio-ecological balance.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors and referees of this journal for their indispensable feedback and encouragement to become better scholars in this emerging subject. It was a stimulating journey. Needless to say, any mistakes remain our own.