9.1 Introduction

Crises are often perceived as destructive, but they can also offer an opportunity for societal change. They can force rapid (and comprehensive) political decisions, make new resources available, change the discourse on what are considered possible or appropriate social measures, and create openings in the political debate to pave the way toward decarbonization (Reference DolanDolan, 2021; Reference Kivimaa, Laakso, Lonkila and KaljonenKivimaa et al., 2021; Reference Skovgaard, Hildingsson, Johansson, Burns, Tobin and SewerinSkovgaard et al., 2018; Reference StarkStark, 2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic unquestionably disrupted established norms and procedures. Governments worldwide imposed restrictions that affected people’s lives. In April 2020, the UK government announced that it was postponing the climate change conference in Glasgow to 2021 as a result of the “unprecedented global challenge” of the coronavirus (UK government, 2020). At the same time, many people perceived the global health crisis as an opportunity to make significant steps toward decarbonization and green recovery (Reference Le Billon, Lujala, Singh, Culbert and KristoffersenLe Billon et al., 2021; Reference Obergassel, Hermwille and OberthürObergassel et al., 2021). Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic had the potential to disrupt carbon lock-ins (cf. Chapters 2 and 4), facilitate a transformation to a more sustainable society, and open windows of opportunity for more ambitious climate action (Reference Dupont, Oberthür and Von HomeyerDupont et al., 2020; SCPC, 2021; UNEP, 2020). Despite hopes that COVID-19 would open a window of opportunity for decarbonization, the demand for fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas quickly surpassed pre-pandemic levels, and in 2021, global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions also returned to pre-2020 levels (Reference Browning and SharafedinBrowning and Sharafedin, 2021; Reference Friedlingstein, O’Sullivan and JonesFriedlingstein et al., 2022).

Like many other countries, Sweden was heavily impacted by COVID-19. The pandemic struck in a highly collaborative governance setting, in which non-state actors, initiatives, and networks promoting climate action were critical societal actors. An exogenous shock such as COVID-19 can affect voluntary pledges to reduce CO2 emissions and the ability of climate networks to bring about change. Climate networks in Sweden and the associated actors had to adapt to and navigate this dramatic and unpredictable situation that affected both the climate networks themselves and their members. In this chapter, we unpack how the pandemic has influenced the efforts of the different types of climate networks in Sweden. Arguing that COVID-19 can constitute both an opportunity and a risk for non-state climate action, we investigate whether or not the pandemic created a window of opportunity for non-state actors to achieve their voluntary pledges or push the state to adopt more ambitious action, and whether or not the state has been able to mobilize non-state actors, or if it has made it harder for them to mobilize. More specifically, we address three guiding questions: How has COVID-19 affected the climate networks? How have they adapted to the crisis? And what have been the consequences of COVID-19 on the interaction between non-state actors and the state?

The three climate networks in focus here differ regarding their goals, structures, and interaction with the Swedish state. First, Fossil Free Sweden (FFS) is a state-orchestrated initiative to speed up the transition to a carbon-neutral economy in various sectors. FFS comprises numerous non-state and sub-state actors, such as companies, local governments, and environmental organizations that share a common vision of a fossil-free society. There are no formal requirements to participate in the network. Nevertheless, the various actors can voluntarily accept one of the network’s challenges to implement concrete measures to reduce GHG emissions. Second, the Haga Initiative (HI) is a business initiative aimed at leading the way and influencing other businesses to become more sustainable. It solely comprises large companies. The HI also tries to influence national policies and the political agenda by proposing new policy instruments in Sweden and the European Union (EU). Third, Fridays for Future (FFF) is a social movement that challenges the state’s climate politics, mobilizes public support, and aims to influence policymakers. Given the different forms of activities, strategies, goals, and interactions of the three networks with the state (cf. figure 2.1), we cover a small but diverse set of cases. This allows us to draw conclusions based on the significant differences across the networks.

Overall, the pandemic has not led to long-term changes among the actors involved in state and business-led climate networks such as FFS and the HI. There are indications that the network participants have changed their working methods and the way in which they communicate about climate action. Nevertheless, overall efforts regarding climate change and sustainability issues have continued as before, with no significant reduction in output. However, the pandemic affected the ability of social movements to carry out their main activity, at least in the short term, that is, to go out on the streets and demonstrate.

9.2 Sweden’s Response to COVID-19 in a Collaborative Setting

Sweden’s tradition of a consensus-based mode of governance builds on coordination and cooperation between all societal actors to catalyze collaborative action (see Chapter 4 for Sweden’s governance model). This also manifests in contemporary climate governance through collaborative networks between state, sub-state, and non-state actors. In such a collaborative setting, voluntary emission reduction pledges and climate networks become critical instruments as well as binding legislation to achieve Sweden’s climate goals (cf. Chapters 2, 4, and 7). However, highly fossil-fuel-dependent municipalities such as Lysekil demonstrate the complexity of decarbonization efforts and the societal conflicts they entail (see Chapter 8 for details). Sweden is also the birthplace of the climate youth movement Fridays for Future, which is protesting against the lack of government action to tackle climate change.

Sweden followed the aim of most countries to prevent and combat the spread of COVID-19 but implemented somewhat different measures to achieve that aim. While many countries introduced (strict) lockdowns, Sweden prioritized government recommendations and voluntary action based on personal responsibility. However, stringent regulations were also introduced, and while these were never as harsh as in countries such as Germany or the UK, regulations were introduced and maintained throughout 2021 (Reference Hale, Angrist and GoldszmidtHale et al., 2021). In March 2020, the limit on public gatherings was set to 50 people, which was lowered to eight people in November 2020. Elderly homes were closed to visitors on April 1, 2020. People from non-EU/European Economic Area countries were stopped from entering Sweden, starting March 19, 2020, and the consumption of food and drink in restaurants and bars was only allowed while seated. Distance education was introduced for upper secondary and university students, while primary and lower secondary schools remained open. The Public Health Agency of Sweden also issued general advice on public behavior, which should not be viewed as tips or suggestions but are interpretations of the Communicable Diseases Act.

These government recommendations have had significant consequences on the ability of people to gather or mobilize public action. In March 2020, Greta Thunberg encouraged her fellow FFF protestors to move their #climatestrike online in order to comply with the regulations on social distancing. Given their reliance on mass meetings and advocacy, climate activists and climate networks have had to adapt in various ways to continue their efforts to tackle the climate crisis.

9.3 The Effects of a Crisis: COVID-19 and Climate Change Mobilization

Exogenous shocks such as large-scale crises can create a new mindset in which genuine change becomes possible (Reference StarkStark, 2018). They can facilitate or accelerate societal transitions (Reference Kivimaa, Laakso, Lonkila and KaljonenKivimaa et al., 2021). A crisis may hinder or strengthen environmental policy (Reference Skovgaard, Hildingsson, Johansson, Burns, Tobin and SewerinSkovgaard et al., 2018). It is not uncommon for extreme weather events to be seen as a window of opportunity, for example adopting policies aimed at adapting to long-term climate change (Reference DolanDolan, 2021) or initiating an institutional change that leads to improved outcomes for the population (Reference McSweeney and CoomesMcSweeney and Coomes, 2011). The impact of a crisis depends on what kind of crisis it is. For example, climate change could be considered a “fundamental crisis” that is hard to predict and influence in contrast to a “conventional crisis,” which is predictable and which has many opportunities to influence (Reference GundelGundel, 2005).

Crises can also influence public debates, change the political agenda, and promote the emergence of new narratives. For example, COVID-19 demonstrated what is possible by showing that we can make drastic changes and quickly change our lives if necessary (Reference Herrero and ThorntonHerrero and Thornton, 2020), and that “governments can intervene decisively once the scale of an emergency is clear and public support is present” (Reference Hepburn, O’Callaghan, Stern, Stiglitz and ZenghelisHepburn et al., 2020, p. 4). Crises can also provide fertile ground for regressive policies that affect civic engagement, participation, and democracy (Reference Cretney and NissenCretney and Nissen, 2019). The use of excessive emergency powers and restrictions on media freedom has affected democratic values in several countries since the start of the pandemic (Reference Maerz, Lührmann, Lachapelle and EdgellMaerz et al., 2020).

Scholars hoped that the pandemic would act as a catalyst for transformation and facilitate the transition of society away from fossil fuels to a more sustainable path. Not least, the extensive recovery programs in Sweden and the EU have been highlighted as an opportunity to increase the speed of the transition (Reference Lehmann, de Brito and GawelLehmann et al., 2021; Reference Maniatis, Chiaramonti and van den HeuvelManiatis et al., 2021; Reference Rosenbloom and MarkardRosenbloom and Markard, 2020). At the same time, COVID-19 and the subsequent economic challenges pose a risk of shifting the focus away from the climate crisis and the urgent need to implement emission reduction measures (Reference Hepburn, O’Callaghan, Stern, Stiglitz and ZenghelisHepburn et al., 2020). COVID-19 might not have entirely changed the adoption of policies but instead seems to have had the potential in some policy areas to affect the speed of change. Such a “path clearing punctuation,” as Reference Hogan, Howlett and MurphyHogan et al. (2022) call it, serves as an accelerator that can lead to change where change is already underway. In the UK, the overhaul of the rail franchise system had long been proposed but took a long time to implement. Then, the pandemic accelerated the overhaul (Reference Hogan, Howlett and MurphyHogan et al., 2022).

In what way are climate networks affected by a crisis in a collaborative governance setting? Studies have evaluated the extent to which collaborative governance has been helpful in combating COVID-19 (Reference Cyr, Bianchi, González and PeriniCyr et al., 2021; Reference Schmidt, Schalk and RidderSchmidt et al., 2022) or how crises can act as catalyst for co-management/collaborative governance (Reference Prado, Seixas and TrimblePrado et al., 2022). However, there is a gap in how crises affect existing collaborative governance settings. This chapter aims to fill this gap.

9.4 Methods and Material

In order to explore how the pandemic affected climate networks in Sweden, we carried out an online survey and conducted 17 interviews. The interviewees were from the secretariats of two of the networks (FFS and the HI), and activists from the civil society organizations, local governments, and companies. They were all members of or actors in at least one of the three climate networks. One hundred and twenty-three individuals responded to the survey in 2021 (26 percent response rate), most of whom were members of FFS. For FFF, local groups were asked to respond. FFS dominated the survey as a result of the size of the network compared to the number of HI member companies and local FFF groups. The respondents worked at either a business (61), municipality (21), trade association (17), civil society organization (5), national agency (4), university/college/research institute (3), or as an elected representative in local government (2). Around two-thirds of the respondents primarily worked with climate and sustainability action. We asked how COVID-19 affected their organization’s work with climate change and their goals for reducing emissions. We also asked whether COVID-19 had affected the way in which their organization communicated and whether they had learned any lessons from how they had responded to COVID-19 in relation to their work on decarbonization. We also asked how they viewed the role of their current initiative and their perception of how COVID-19 had affected the significance of climate change on the political agenda.

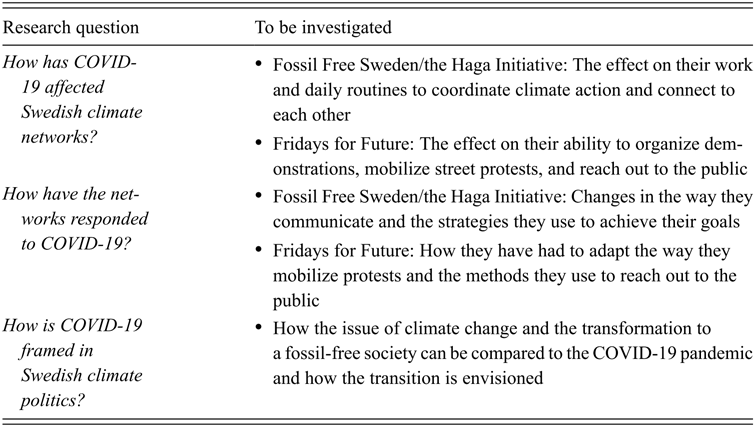

We conducted 17 semi-structured interviews in spring 2022 in order to understand better if, how, and why the different actors have changed or adapted their goals, strategies, and arguments in response to COVID-19, and the subsequent political situation. A combination of both structured and unstructured questions guided the interviews in order to obtain information about the effects of COVID-19, gain a deeper understanding of the respondents’ experiences and perceptions of the COVID-19 crisis, and elaborate on whether or not it created windows of opportunity (Reference Halperin and HeathHalperin and Heath, 2020). After 17 interviews, a certain saturation point was reached (Reference Baker and EdwardsBaker and Edwards, 2012; Reference SandelowskiSandelowski, 1995), with considerable consensus among the interviewees about the effects of the pandemic. The experiences of the pandemic differed between FFS and the HI on the one hand and FFF on the other. Table 9.1Footnote 1 summarizes the three questions that guided the analysis.

Table 9.1 Analyzing the effects of COVID-19 on climate networks

| Research question | To be investigated |

|---|---|

| How has COVID-19 affected Swedish climate networks? |

|

| How have the networks responded to COVID-19? |

|

| How is COVID-19 framed in Swedish climate politics? |

|

We carried out this study while the pandemic was still ongoing, with the survey being conducted during the spring and early fall of 2021 and the interviews conducted one year later. Since this time, vaccines have made it possible to return to pre-pandemic life, although the pandemic’s long-term effect on climate politics is yet to be seen.

9.5 Navigating through a Crisis: Swedish Climate Networks and Their Response to COVID-19

A short time after COVID-19 was discovered, it quickly became a global health crisis that governments around the world responded to by introducing strict measures. In the field of climate change, scholars expressed the hope that green recovery plans would lead to more ambitious climate action in the aftermath of the pandemic (Reference BostonBoston, 2020; Reference Pollin, Garrett-Peltier, Heintz and ScharberPollin et al., 2008; Reference Pons, Borchers-Gasnier and LeturcqPons et al., 2020; UNEP, 2020). However, there was also fear that the momentum of climate action fueled by increased protests and pressure would halt as a result of the pandemic (Reference FigueresFigueres, 2020; Reference Hook and WisniewskaHook and Wisniewska, 2020). Our findings suggest that while members of climate networks articulate both perspectives, they only cover part of the story.

9.5.1 How COVID-19 Has Affected Swedish Climate Networks

Based on the interviews and the survey, most organizations involved in either FFS or the Haga Initiative have not reported significant changes in how they worked toward decarbonization as a result of COVID-19. Only 17 percent of the organizations stated that they had been forced to prioritize other issues at the expense of climate work, and only 9 percent of the organizations said that it had meant fewer financial resourses to dedicate to climate action. This is supported by the interviews. Despite some initial disruption in the spring of 2020, the networks and associated organizations were able to continue with their regular work:

During the first weeks of March/April 2020, a lot of stuff slowed down and got canceled or postponed. I think most people thought they would be home for two to three weeks and then everyone would return to work. […] But when it started to dawn on people that it would last longer than expected, they increasingly started to work online. (Interview, FFS company representative)

None of the interviewees from FFS and the Haga Initiative reported significant disruption to their work. The interviewees from the Haga Initiative even felt it was easier to reach out to politicians:

[I]t worked great with our webinars. A lot of people came and listened, and we achieved a greater participation from … all over Sweden. It was very international, too; more international during the pandemic than before it. Then we have the politicians; the politicians were easy to reach. We had a conference during the fall, a year before the election, and had the climate policy spokespersons from each party. It was a webinar. We had more individual meetings with politicians online. It hasn’t been a problem. (Interview, HI)

A municipal worker stated that they had to cancel or postpone external activities or do them differently. Nevertheless, in the end, it has been “business as usual.” Another municipal worker stated:

Nevertheless, in many ways we were able to work as we usually do – we’ve just had to find other ways. But we’ve managed to do most things, anyway. […] We probably used some of our resources on the Covid issue. The communicators we have used in our environmental work have been fully occupied with Covid. An occupational study trip had to be canceled. Otherwise, we have just continued and quickly switched from regular meetings to online meetings. (Interview, municipality in FFS)

The commitment to climate action of politicians in the municipalities we investigated does not appear to have been affected. Those politicians who were already engaged have maintained their commitment. While internal communication has been as good as before the crisis or improved as a result of digitalization, interaction with actors outside the network became more challenging when public gatherings were no longer permitted. While the pandemic did not impact the commitment to climate targets among those people who were already engaged, some of them stated that they found it harder to reach out to new people.

Recovery packages can significantly impact whether or not globally agreed climate goals are met (Reference Hepburn, O’Callaghan, Stern, Stiglitz and ZenghelisHepburn et al., 2020). A representative of FFS believed that the pandemic had made it possible to unashamedly demand more significant investments to decarbonize. In the business sector, this was seen as an opportunity to attract funding for the transformation (Interview, FFS).

The survey respondents found it difficult to assess how the pandemic had affected the climate networks they belong to, with 53 percent of them stating that they did not know. Of those respondents who had an opinion, most of them said that COVID-19 had impacted their efforts toward achieving climate targets and decarbonization. The interviews provide some insights into why the “don’t know” response option might be so prevalent. Many interviewees had minimal interaction with FFS and were more passive recipients of information from them rather than actively engaging. Of those interviewees who had been involved in the production of the roadmaps for fossil-free competitiveness (cf. Chapters 4, 7), this work had already been completed by the time COVID-19 hit.

While the pandemic did not have a major impact on FFS and the Haga Initiative, it did impact FFF , particularly concerning the movement’s weekly demonstrations. When the pandemic struck, many people stopped attending the demonstrations and the large-scale global protests ceased. In Sweden, restrictions were gradually introduced on the maximum number of people who could gather in public. In spring 2020, it was set at a maximum of 50 people, and later in the fall it was reduced to eight people. This directly impacted the opportunity to conduct even socially distant demonstrations. One interviewee recalls a situation when the police strictly enforced the eight-people rule – enacted on November 24, 2020 – although they had rarely checked on the protests before:

We had organized it so that when […] there were nine people, then [the ninth] person had to stand somewhere in the square, so that the group did not become larger than eight people. But [the police] interpretation, the legally harsh interpretation then, was like, “no, it’s the same gathering, so it is not valid to do it that way.” […] I mean, what could we do? We belong to the good guys of the climate movement and we don’t break the law in order to bring about change. We work within the law together with all the positive forces in society. (Interview, FFF)

According to Reference Grant and SmithGrant and Smith (2021), the pandemic may have recalibrated the personal risks and benefits associated with protest. This raises ethical questions about how activism should be carried out. Is it possible to demonstrate in favor of evidence-based climate policymaking while complying with the scientifically based regulations on social distancing? Scientific evidence – listening to the scientists – is at the core of FFF, and this seems to have made its members particularly aware of how they dealt with issues regarding social distancing. They wanted to ensure that their gatherings would not allow other people to accuse FFF of not believing in science or that they would be compared to, for example, vaccine opponents. One interviewee also hesitated about becoming involved early in the pandemic as a result of moral issues related to the spread of the infection. The interviewee herself was not in a risk group but did not want to risk infecting others. One interviewee described their dilemma in this situation: “We are also people who believe in science, so we pursue that line of argument, which means we cannot […] risk being labeled as a group people who do not believe in science” (Interview, FFF).

The interviewees did not critique the COVID-19 restrictions. They did reflect on how the police interpreted the restrictions, which made it hard for them to demonstrate, even when they tried to come up with new ways of protesting that did not include large gatherings. The restrictions affected the various local groups differently as some demonstrations rarely exceeded the legal limit and, therefore, had a more limited effect.

9.5.2 Responding to the Pandemic: Goals, Arguments, and Strategies

For the actors involved in FFS, adapting to the crisis mainly meant changing communication patterns due to the increased number of online meetings.

One of the practical lessons from the pandemic was the need to find a balance between having physical and online meetings. Communication with already-established networks and colleagues has improved through digital means. In other situations, the pandemic created challenges. For example, it became more difficult to communicate with the general public because public events had to be canceled or postponed: “I guess that’s what I feel strongest about, that the interactions with [citizens] has been changed” (Interview, municipality in FFS).

Companies that are part of the Haga Initiative aim to become fossil-free by 2030, meaning that their emissions will be at least 85 percent lower than 1990 levels, and the remaining 15 percent can be achieved with emission reductions abroad. FFS has launched four challenges for concrete climate action for corporations, municipalities, regions, and organizations. The challenges focus on actions that these corporations, municipalities, regions, and organizations can implement to lower their carbon footprint. For example, the transport challenge means establishing a goal for domestic transport to be fossil-free by 2030. The overall assessment was that the pandemic had not affected the output and the ability of the actors involved in FFS and the Haga Initiative to achieve their climate goals.

The fact that none of the interviewees expressed concern that their goal achievement would be negatively affected is also supported by the survey results, in which 67 percent of the interviewees did not think that COVID-19 had impacted how fast they were able to achieve their goals. If anything, there was a sense that the pandemic had made it easier to achieve the emission reduction targets in the transport sector if the changes in our travel patterns could be sustained. The way we have changed our travel patterns is the area in which the effects of the pandemic are mainly talked about in terms of a window of opportunity to speed up the transformation to a fossil-free society, as exemplified by how COVID-19 has accelerated digitalization and hence decreased the need for travel.

Two actors involved in FFS saw opportunities to learn from the pandemic. One of the actors reflected how a pandemic that lasted two years has demonstrated the power of joint action and has made it easier for individuals to see their role in the bigger picture of society. The other actor pointed to the high level of trust in public authorities in Sweden, and how this can be used to transform society by enabling public agencies to be more active. Several interviewees pointed out that COVID-19 measures demonstrated that it is possible to adapt quickly and that massive changes can happen. This is in line with what Reference Herrero and ThorntonHerrero and Thornton (2020) described as an opportunity that resulted from COVID-19. The pandemic, they argue, affects what we perceive as possible by showing us that we can make far-reaching changes and quickly change our lives if needed.

FFF activists responded to the challenges that arose from the pandemic by moving to the digital realm, both as an alternative to demonstrating on the streets and as a way of staying connected with each other in the movement in times of social distancing. Some activists also tested new ways of engaging people and learned some practical lessons from this time. One activist explained how they had focused on specific projects when there were not so many opportunities to demonstrate and that it was a lesson learned that other activities, such as participating in meetings, could also help them work toward their goals. The activist also pointed out that it is more challenging to conduct activities online as it makes it more difficult to create the sense that you are fighting for the same goal when you do not meet physically.

The interviewees suggested that the pandemic gave the young movement time to focus on internal work and enhance the connection between activists in different cities. Another critical question was about how to get people engaged and keep them involved. Some activists became less involved, especially in the most acute phase of the pandemic. One of the activists stated that it had been more difficult to recruit new members because, understandably, people wanted to be more careful.

Some early studies have shown how FFF has changed what and how it communicates as a result of COVID-19. The number of tweets using #fridaysforfuture decreased sharply and the tweets increasingly focused on thematic discourses and debates around the legitimacy of FFF rather than calls for mobilization (Haßler et al., 2021). FFF activists had to rethink their communication strategies and engage “with the new discursive opportunity structure” as a result of COVID-19 (Reference Sorce and DumitricaSorce and Dumitrica, 2021, p. 5). They adapted their communication, and while trying to maintain a level of climate activism online, compliance with government regulations was promoted by leading figures such as Greta Thunberg. Globally, FFF “collectives shared posts with a compliance frame, including statements such as ‘stay at home’ (Romania), ‘wash your hands’ (Finland), or practice ‘social distancing’ (Germany)” (Reference Sorce and DumitricaSorce and Dumitrica, 2021, p. 7).

Two core beliefs of FFF were promoted concerning both climate change and the pandemic: the need to follow the recommendations of scientists and to act in solidarity with others, thereby reaffirming the need to listen to scientists and emphasize that we need to change our behavior when faced with a crisis and that change is possible. However, the “extent to which a movement can take advantage of crises on a discursive level may remain limited” (Reference Sorce and DumitricaSorce and Dumitrica, 2021, p. 10). Not only the narratives but also the people behind FFF changed. According to Reference Gardner and NeuberGardner and Neuber (2021), protestors have become younger and more politically engaged. These changes have occurred in line with an increasing “dissonance between perceptions that the state is capable of enforcing science-based regulations in crisis scenarios and concerns that they will not be applied to the climate crisis” (Reference Gardner and NeuberGardner and Neuber, 2021, p. 24).

9.5.3 Framing COVID-19 in Swedish Climate Politics: Risk or Opportunity?

A crisis like COVID-19 can be framed as an opportunity to adopt new measures or accelerate the pace of decarbonization. At the same time, it poses a risk of backsliding or slowing down climate action as the economy, public health, and security are prioritized. The interviewees from FFS and the Haga Initiative did not state that COVID-19 had caused them to slow down or cease any of their climate actions. Instead, the dominant framing among members of both networks was that the pandemic had not significantly impacted their climate action or targets. COVID-19 had not slowed down or led to activities being canceled, nor had it been mobilized as an opportunity to speed up and ramp up action. Almost all the interviewees provided examples of how it had been “business as usual” with some minor adjustments in order to engage in more online activities.

Some study trips have been canceled, but otherwise, we have just continued and quickly switched from regular meetings to online meetings. (Interview, FFS)

When the pandemic struck, and with the measures taken to deal with it, parallels were drawn between how climate change and COVID-19 are handled – or not. The FFF interviewees stressed the need to tackle both crises in a similar way, which had also been emphasized by Greta Thunberg (Reference AlestigAlestig, 2020). This was heeded by some national and local governments who declared a climate emergency. In Germany, various cities made this declaration following a request from FFF. They were supported by the Green Party and the Social Democrats (Reference Ruiz-Campillo, Castán Broto and WestmanRuiz-Campillo et al., 2021). The expected outcomes of these declarations vary from purely symbolic to constituting a commitment to action, linking it to a “way of doing climate politics aligning climate change and biodiversity concerns” (Reference Ruiz-Campillo, Castán Broto and WestmanRuiz-Campillo et al., 2021, p. 23). This framing occurred in an interaction between governments and civil society. However, when the interviewees discussed the crisis narrative on climate change, a warning was raised about relying on a crisis narrative and adopting measures such as making decisions faster, as it could jeopardize democratic decision-making. Such measures may be reasonable in an emergency or an acute crisis but must not be too protracted and do not apply to a crisis such as climate change, which has an entirely different time frame than the pandemic.

[In a crisis] you should be able to make decisions quickly without having to engage with all the usual political bodies. It is very important to preserve democracy in this period of societal transition due to climate change. (Interview, municipality FFS)

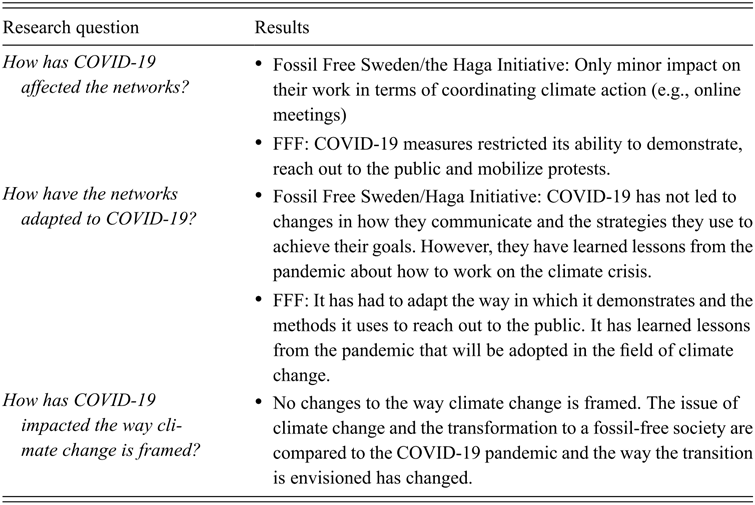

Table 9.2 summarizes how COVID-19 has affected the climate change networks, how these networks adapted to the crisis, and how COVID-10 impacted the way climate change is framed.

Table 9.2 Summary of results: How COVID-19 affected climate networks

| Research question | Results |

|---|---|

| How has COVID-19 affected the networks? |

|

| How have the networks adapted to COVID-19? |

|

| How has COVID-19 impacted the way climate change is framed? |

|

9.6 Discussion

This chapter illuminates how the pandemic affected a business network, a government-led multi-stakeholder platform, and a social movement and how they adapted to the global health crisis resulting from COVID-19. Our findings indicate that thus far the pandemic has not led to deeper changes, neither in the climate debate in Sweden nor in the climate work of individual actors. The members of climate networks have changed their working procedures and modified their communication strategies when it comes to climate action. Most of them have also stated that as a result of digitalization, more actors have been able to become involved in their sustainability work. The extent to which these trends translate into lower carbon emissions is yet to be determined. While some changes are noticeable, particularly in the use of digital tools, the pandemic has not significantly disrupted their work, nor has it impacted the climate initiative or the work of the actors in the initiative. In sum, the pandemic has not caused any major changes for FFS participants or the network secretariat itself.

We can interpret this in two ways: First, participants of FFS and members of the Haga Initiative described their work as resilient to an external crisis such as COVID-19. According to them, the pandemic had no decisive implications for their climate work. The fact that they made a commitment when they joined a network and established working methods that will steer them toward the climate goals would ensure that their work will continue, even if external pressures have impacted their organization. Secondly, the COVID-19 pandemic was considered a lost window of opportunity for making more substantial changes to our way of life. The expectations and hopes that were presented at the beginning of the pandemic, with a strong focus on a green recovery, have not materialized in Sweden. The governance mode of orchestration seems to have continued without any significant disruption. This was facilitated by the fact that FFS had already come a long way in its work and, for example, had completed the 22 roadmaps to decarbonization. In many ways, the network seems to have been able to continue as before. Also, the Haga Initiative’s role as an agenda setter was not impacted. If anything, it found it easier to gain access to politicians during COVID-19, as online meetings created opportunities to conduct individual sessions and larger seminars.

It is important to note that the actors studied here are actors that have shown an interest in climate action. Among the organizations that were already, to some extent, engaged in climate action, the effects of the pandemic were marginal, and the achievement of their climate goals has not been significantly impacted.

In contrast, members of business-oriented and multi-stakeholder networks stated that COVID-19 has shown that changes can be implemented collectively and rapidly, that digitalization can facilitate work, but that a balance must be struck between physical and online meetings. One interviewee stated that the public at large has a high level of trust in Sweden’s authorities; this can be positive and enable public authorities to be more active. There was also a sense of empowerment that if the state uses its authority properly, it might be easier to make the individual feel committed and part of the transition. The high level of political trust in Sweden (e.g., Reference Kumlin, Haugsgjerd, Zmerli and van der MeerKumlin and Haugsgjerd, 2017) can be an asset when attempting to use a collaborative mode of governance during the process of societal decarbonization.

The pandemic affected the ability of social movements to carry out their main activity, namely protesting on the streets. Several interviewees testified that the police strictly interpreted the law, making it difficult for them to continue protesting. One activist also stated that they used this time to focus on internal work. Besides, the movement was keen to keep up with research and comply with the existing recommendations. Consequently, they did not challenge or oppose the recommendations. These findings somewhat contradict the studies of patterns of political and civic engagement in other countries. Reference Pressman and Choi-FitzpatrickPressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick (2021) found that the COVID-19 pandemic did not cause a dramatic change in protest behavior in the United States. Street protests (including marching, carrying signs, chanting, and speeches) continued to be the main activity. Looking at political and civic engagement, Reference Borbáth, Hunger, Hutter and OanaBorbáth et al. (2021) showed a persistence of pre-existing patterns of political and civic engagement in seven Western European countries. A large part of the engagement related to the pandemic, helping the local neighborhood, and donating money.

Looking at the role of civil society, we observe that the critical watchdog position – or the role of contestation and protest – has been most significantly affected by the pandemic. The pandemic has also affected the ability to demonstrate and has made it harder to put focus on climate change through the media. Forms of contestation and open criticism of the lack of ambition in the government’s climate policies were more significantly affected by the pandemic compared to lobbying activities by networks of business actors, such as the Haga Initiative.

COVID-19 was described as having little impact on the goals and climate targets adopted by FFS and the Haga Initiative. Instead, their work can be characterized as “business as usual” in Sweden’s collaborative governance setting (see Chapter 4). Our findings indicate that there are established procedures for working with climate change at the local level and in companies in which specific people responsible for climate work. This form of institutionalization seems to prevent the deprioritization of and decrease in sustainability work during a crisis. Reference Skovgaard, Hildingsson, Johansson, Burns, Tobin and SewerinSkovgaard and colleagues (2018) reached a similar conclusion when investigating the economic crisis of 2008/2009.

Swedish climate policy is characterized by a strong optimistic narrative in which economic growth, environmental protection, and climate mitigation are expected to go hand in hand (Reference Lidskog and ElanderLidskog and Elander, 2012). This narrative is very compatible with the business-as-usual framing with its focus on the economic benefits of a transition. This narrative can also be connected to the limited discussion that a recovery after COVID-19 can be mobilized in favor of a transition, but that COVID-19 should not affect the incremental improvements to decarbonize the Swedish economy. Such a narrative leaves less room for contestation. Societal conflicts are toned down through its focus on win-win situations and synergies, and the focus shifts away from the need to discuss winners and losers in the transition. A crisis can lead to pre-existing beliefs and practices being deinstitutionalized, paving the way for competition between actors seeking policy change or preservation of the status quo (Reference Burns, Tobin and SewerinBurns et al., 2018). While the political response to the crisis could have either been shaped or challenged by this policy paradigm, COVID-19 does not appear to have affected this paradigm. FFF attempted to reframe climate change as a crisis which requires a response at least as robust as that to COVID-19. Yet the movement failed to alter the political debate in Sweden on a fundamental level.

In terms of state–non-state relations, COVID-19 did not affect the networks’ ability to impact the agenda or push toward more ambitious action (lobbying). Also, regarding the state’s ability to catalyze cooperation and mobilize non-state actors, we did not observe any major shift (orchestration). However, COVID-19 impeded the ability of climate networks to challenge the state and push for more ambitious action (contestation).

9.7 Conclusion

At the onset of the pandemic, there was a risk that climate targets, advocacy, and efforts to decarbonize undertaken by businesses, civil society, and multi-stakeholder networks could be rolled back. The strict measures taken in response to the pandemic were perceived as a threat to the various climate networks. At the same time, governments and scholars quickly framed COVID-19 as an opportunity to engage in more ambitious climate action. Governments worldwide proposed and initiated green recovery programs to foster a climate-friendly post-COVID-19 era, and scholars compared COVID-19 with the climate crisis. They argued that early action and trust in science are essential lessons to be learned from the pandemic and should be adapted to the climate change issue (Reference Manzanedo and ManningManzanedo and Manning, 2020). A crisis is not a risk or an opportunity per se but is constructed as one by various social and political actors. With that in mind, the actors examined in this chapter have neither chosen to frame COVID-19 as a risk to climate action nor considered it a fundamental opportunity to tackle climate change. Instead, they have created a third framing, business as usual, in which COVID-19 means neither a setback nor a clear turning point to implement more ambitious measures.

To some extent, one way in which the pandemic has been constructed as an opportunity by the Swedish government is through the idea of a “green recovery” (Reference Carp and JonesCarp and Jones, 2021). According to the government, this policy aims to reduce emissions and create new jobs. It is intended to facilitate the transformation to a fossil-free society while also getting us out of the crisis caused by the pandemic. This idea fits well into the Swedish narrative, in which innovative policies, economic development, and climate measures are supposed to go hand in hand. However, the Swedish Climate Policy Council criticized the government’s policy, arguing that only one-tenth of the government’s recovery efforts also contributed to achieving its climate policy goals. Hence, this narrative is no guarantee of effective policies being introduced to tackle climate change.

So what lessons can we learn from COVID-19? Early work has stressed the disruptive effects of COVID-19 and the major transformations it could trigger (Reference Botzen, Duijndam and van BeukeringBotzen et al., 2021; Reference Manzanedo and ManningManzanedo and Manning, 2020; Reference Prideaux, Thompson and PabelPrideaux et al., 2020). Our empirical findings tell a much more cautious story. We have even observed modes of resilience and a “rebound effect” when patterns of production and consumption returned to the pre-pandemic level. Our findings call for more research, not only on ambitious climate action undertaken by climate networks from civil society, industry, and municipalities but also on the obstacles to decarbonization and the forces that uphold carbon lock-ins and continued fossil-fuel dependency, including vested interest groups (cf. Chapter 4).

It could be asked whether COVID-19 was the “wrong” kind of crisis for sparking a more profound transformation toward a fossil-free society. Comparing the oil crises of the 1970s and the financial crisis of 2008, we conclude that a crisis with a direct effect on a fossil dependent system seems to provide a significant opportunity to promote decarbonization. Nevertheless, the indirect effects of financial crises do not have the same outcome. COVID-19 can thus be seen as a temporary crisis without long-term transformative change. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine renewed discussions about the implications of decarbonization efforts in conjunction with energy security, particularly across Europe. While the war has highlighted the EU’s dependency on Russian oil and gas, its long-term effects are yet to be seen. Revived debates about energy independence can either lead to systemic changes to the energy system, in which Russian oil and gas are replaced, or conventional sources of energy such as coal or nuclear power could be revived. The experiences of the COVID-19 crisis at least indicate that external crises do not necessarily transform individual sectors or societies if they are not accompanied by structural changes. What we need is the politically driven transformation of individual sectors, such as the energy or transport sector, and the social, economic, and political system in its entirety.