To the Editor—Reports of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission resulting directly from a conjunctival blood splash are extraordinarily rare and are limited by an inability to exclude other exposures and an absence of any phylogenetics, linking the source and recipient’s viruses.1–Reference Joyce, Kuhar and Brooks6 The risk of acquiring HIV infection from a nongenital mucosal blood splash, is based on distant and very limited data and is stated to be <0.09%.Reference Nwaiwu, Egro, Smith, Harper and Spiess2,Reference Kuhar, Henderson and Struble7 We have, however, identified and confirmed, through phylogenetic analysis and supportive laboratory evidence, an acute HIV infection following conjunctival blood exposure. This report is provided with informed patient consent (caregiver) and their full support to increase knowledge to reduce the future risk to others from such exposures.

The source patient, an adult female, with severe nonverbal autism, had acquired HIV infection through blood transfusions during early childhood. Following confirmation of the source patient’s HIV diagnosis, education was provided to family members with ongoing discussion on the importance of avoiding needle sticks, bites, and all blood exposures on open skin. After 20 years of medical care, due to the irreversible nature of multiple medical conditions, intolerance to and unwillingness to take multiple different antiretroviral regimens and following extensive consultations, the source patient was placed on comfort-focused medical care that did not include antiretroviral therapy (ART). In the home, no needles were present, and gloves were used when handling blood or providing hygiene. All razors, toothbrushes, sponges, and other hygiene implements were kept specific to the source patient and were never shared.

An elderly family caregiver had provided full support to the source patient for >20 years. She presented to her family physician complaining of a 7-day history of increasing headache, confusion, backache, profound lethargy, dysphagia, abdominal pain and weight loss. HIV testing demonstrated an acute HIV seroconversion pattern progressing over 10 days from antigenemia and viremia to antibody seroconversion. Following initiation of ART, HIV replication in the caregiver became suppressed and immunity returned to normal. The source patient’s viral load was 113,000 copies/mL and her CD4 count was 81 cells/mm3 (13%) at the time of the caregiver’s HIV diagnosis. The HIV serology of the caregiver’s husband was negative.

At presentation, when questioned about possible HIV risk exposures, the caregiver reported that she had been regularly providing oral hygiene twice daily to the source patient who, after a dental extraction, had experienced ongoing gum bleeding. Gloves were used on every occasion when blood was visible and/or when fingers were in the mouth, but no eye protection was used. She clearly recalled that ~15 days earlier, she had experienced a single small blood splash to one eye while providing oral hygiene to the source patient. She had not considered the exposure to be significant at the time and did not seek medical attention or postexposure HIV prophylaxis.

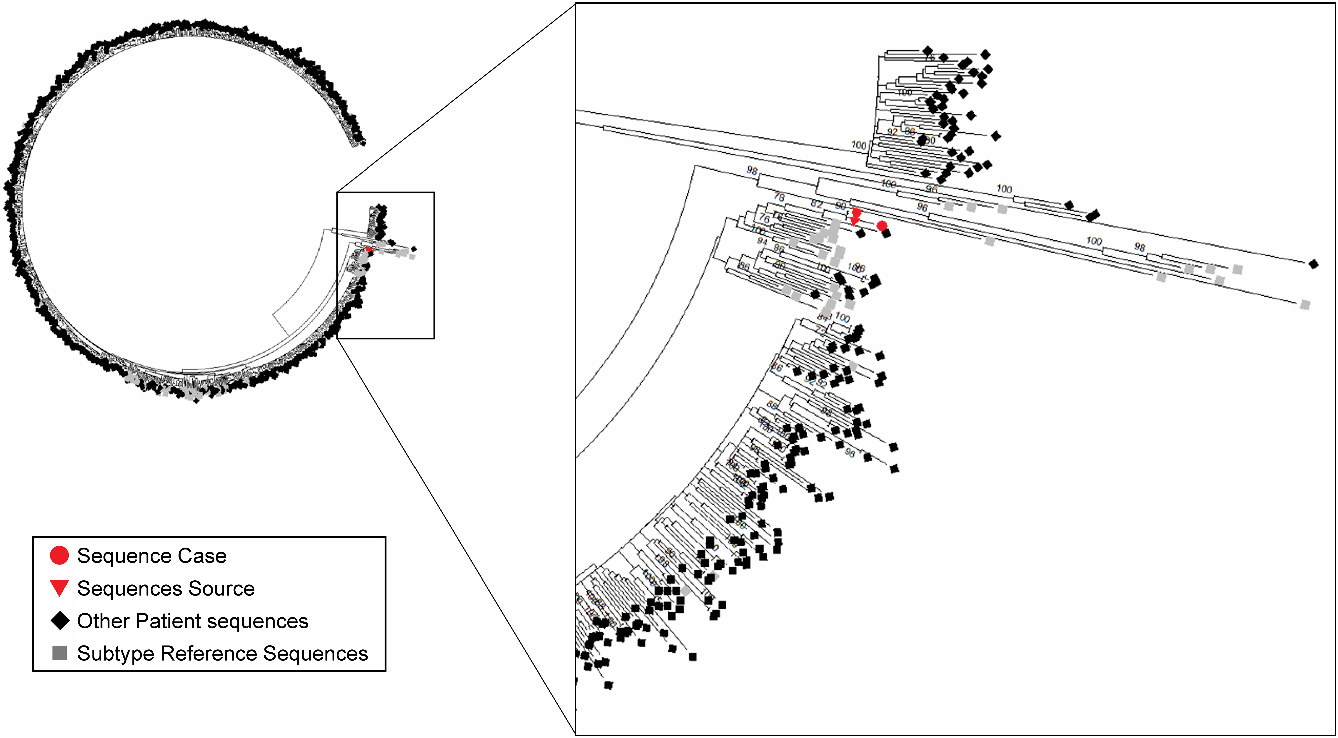

To investigate the transmission event using phylogenetics, HIV sequences obtained from the source patient (for earlier genotypic resistance testing and soon after the transmission event) were compared to the caregiver’s presenting HIV sequence to determine genetic similarities. Multiple sequence alignment and comparison, including RT Protease sequences of other patients stored in our clinic database revealed nearly perfect identity in the nucleic acid sequences of the source (3 sequences from 3 time points: 2014, 2015, and 2019) and caregiver patient’s HIV (1 sequence at presentation). Only 10 unique nucleotide substitutions (with 2014/2015 sequences of the source) and 7 unique nucleotide substitutions (with the 2019 sequences of the source, only one of these changed the amino acid sequence at either time point) were detected between the 2 patients’ sequences. Phylogenetic analysis (maximum likelihood method,) general time reversible model (γ distribution with invariable sites), with bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates) using sequences of 140 reverse transcriptase (RT) protease region sequences from the clinic data clearly indicated a phylogenetic relationship between the sequences (bootstrap value, 99). Repeating this analysis with >1,000 sequences from the clinic resulted in the same result (bootstrap value, 90) (Fig. 1), strongly linking the source and caregiver’s viruses.

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic analysis of sequences of source patient and patient caregiver (ie, cases). Sequences (reverse-transcriptase (RT) protease regions) were used for a phylogenetic analysis (maximum likelihood method, general time reversible model (γ distribution with invariable sites), with bootstrap analysis) against >1,000 patients RT-protease sequences present in the local clinic database. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) subtype reference sequences, as defined by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) HIV genotyping tools, are included. Source patient and caregiver case sequences clustered with bootstrap value of 90, and clustering was also consistent including various HIV subtype reference sequences.

Transmission of HIV to a caregiver is an extraordinarily rare event. A review published in 2017 reported no seroconversions over 13 years among healthcare workers exposed to HIV contaminated body fluids.Reference Nwaiwu, Egro, Smith, Harper and Spiess2 The Centers for Disease Control (CDC), using a robust surveillance system, identified 5 potential occupational HIV transmissions from mucocutaneous exposures between 1985 and 2013, and to our knowledge, no cases have since been described.Reference Joyce, Kuhar and Brooks6 Conjunctival blood exposure leading to HIV transmission has rarely been suggested and nearly all are reported in conjunction with other non–intact skin exposure, and none have been confirmed by phylogenetic analysis.1,Reference Gioannini, Sinicco, Cariti, Lucchini, Paggi and Giachino5,Reference Joyce, Kuhar and Brooks6

This case report carries implications for caregivers, particularly when caring for those with an unknown HIV status or for those not virologically suppressed. Current recommendations for family providing care to persons living with HIV/AIDS are either old or extrapolated from “resource rich” hospital guidelines.Reference Kuhar, Henderson and Struble7,Reference Deuffic-Burban, Delarocque-Astagneau, Abiteboul, Bouvet and Yazdanpanah8 Updated educational standards and resources need to be developed for community care providers, including discussion on risks of mucosal membrane exposure, use of PPE and information and protocols for postexposure HIV prophylaxis, which reduces HIV transmission by 81% after a percutaneous exposure.9

With the use of suppressive ART, the risk of HIV infection through any mucosal surface exposure is deemed nonexistent.Reference Rodger, Cambiano and Bruun10 This medical advance may have resulted in a reduced vigilance in both personal and professional healthcare providers regarding the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and in managing splash exposures, thereby placing caregivers at risk for contracting HIV. We highlight this case to provide evidence of HIV transmission through a conjunctival blood splash and to advocate for updated community infection control training and education regarding HIV risk, PPE importance, and the availability of postexposure HIV prophylaxis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Ian Mitchell for his help, insight, and advice.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.