Impact statement

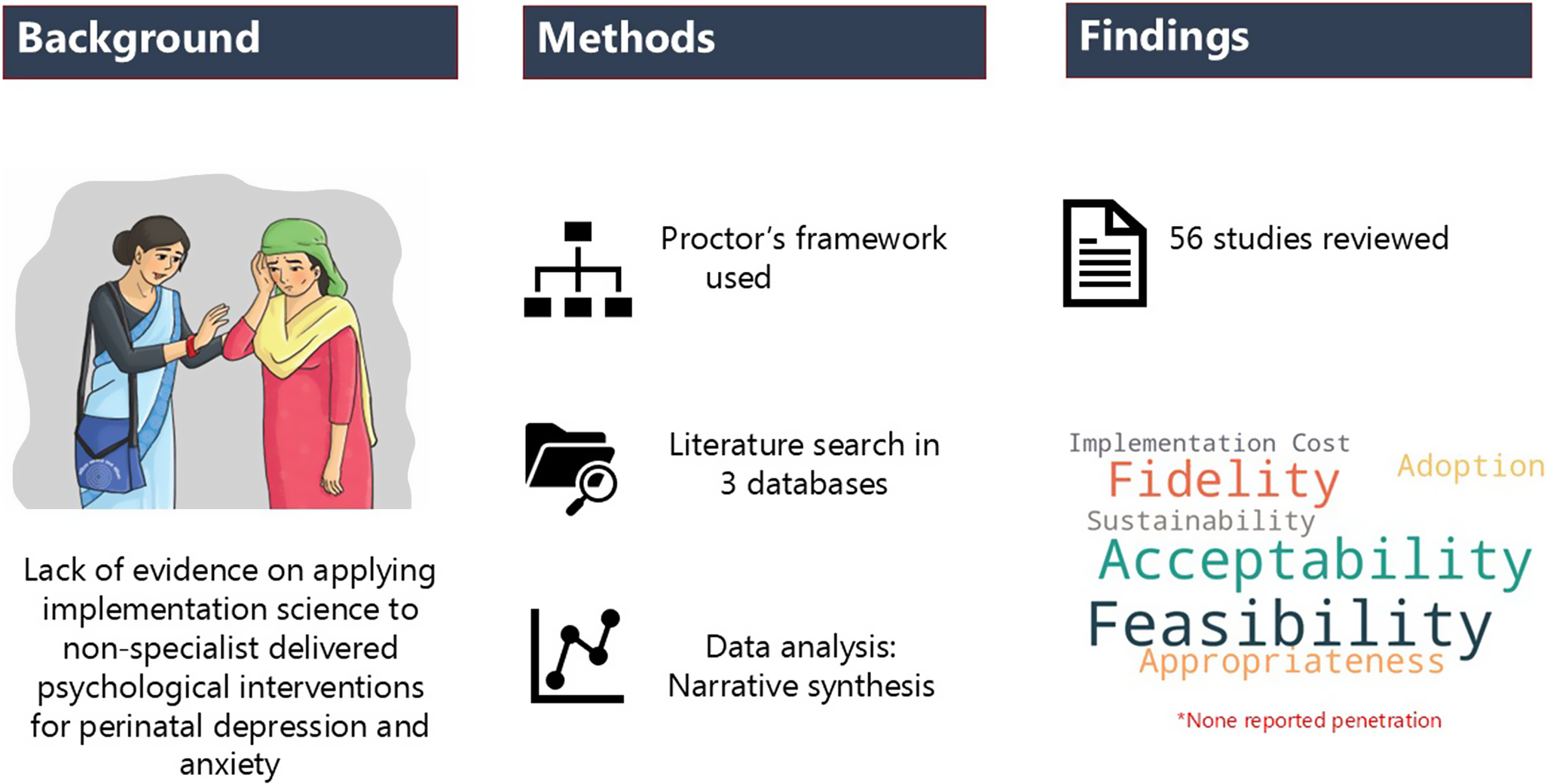

This review synthesizes evidence on the implementation of psychological interventions for perinatal depression and anxiety delivered by nonspecialist health workers (NSHWs). Using Proctor’s framework, it highlights the successes, challenges and processes involved in these interventions offering insights for policymakers, healthcare administrators and practitioners to improve perinatal mental health programs. The review finds that NSHWs can deliver psychological intervention effectively if they are well-trained, supervised and properly incentivized. These interventions are more successful when they fit well with the local culture and integrated within the existing system. However, there is a critical gap in understanding the larger systems that affect the long-term success of these interventions. The review highlights the need for further research on how these programs can be integrated and sustained within the system.

Introduction

Depression and anxiety are the most common perinatal (pregnancy up to 1 year postnatal) mental disorders (Waqas et al., Reference Waqas, Zafar, Meraj, Tariq, Naveed, Fatima and Rahman2022). Approximately 15% and 25% of women suffer from perinatal anxiety and depression and the burden is higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) compared to high-income countries (HICs) (Nielsen-Scott et al., Reference Nielsen-Scott, Fellmeth, Opondo and Alderdice2022; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Gordon, Lindquist, Walker, Homer, Middleton and Hastie2023). Perinatal mental disorders are associated with maternal suicide, poor uptake of health services, delayed social, emotional and cognitive development in infants, and marital discord (Dagher et al., Reference Dagher, Bruckheim, Colpe, Edwards and White2021; Kroh and Lim, Reference Kroh and Lim2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Qiu and Xiao2021; Stewart and Payne, Reference Stewart and Payne2023). Despite its debilitating effects on the woman, her infant and her social relationships, detection and treatment of perinatal depression remains a challenge (Gelaye et al., Reference Gelaye, Rondon, Araya and Williams2016). Evidence suggests that more than 80% of women with perinatal depression are out of care (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Sowa, Meltzer-Brody and Gaynes2016) and less than 40% intend to seek help (Daehn et al., Reference Daehn, Rudolf, Pawils and Renneberg2022). This “treatment gap,” the gap between the need and access to treatment, is more prominent in marginalized populations such as women in rural areas, from ethnic minorities, or with poor socioeconomic status ( Stirling et al., Reference Stirling, Wilson and McConnachie2001; Price and Proctor, Reference Price and Proctor2009; Prady et al., Reference Prady, Endacott, Dickerson, Bywater and Blower2021).

Challenges pertaining to the treatment gap can be broadly categorized into demand and supply-side challenges. Lack of awareness about depression, its treatment options, treatment availability, stigma, time constraints and the practice of “wait and get it over naturally” are common barriers impeding women to seek help (Dagher et al., Reference Dagher, Bruckheim, Colpe, Edwards and White2021; Iturralde et al., Reference Iturralde, Hsiao, Nkemere, Kubo, Sterling, Flanagan and Avalos2021). Further, poor investment in mental health, scarcity of skilled and trained human resources, ill-equipped health facilities, stigma and lack of health professionals’ awareness contribute to the expanding treatment gap (Lasater et al., Reference Lasater, Beebe, Gresh, Blomberg and Warren2017; Dagher et al., Reference Dagher, Bruckheim, Colpe, Edwards and White2021). The World Health Organization (WHO) (2021) reports that 50% of the world’s population lives in a place where there is less than one psychiatrist for 100,000 population. The WHO advocates for a task-sharing approach whereby expert knowledge and skills are transferred to nonspecialist health workers (NSHWs) (WHO, 2016). Psychological interventions are a first-line treatment recommended for perinatal depression. There is a well-established evidence base that shows psychological interventions delivered by NSHWs are effective both at preventing (Prina et al., Reference Prina, Ceccarelli, Abdulmalik, Amaddeo, Cadorin, Papola and Purgato2023) and treating perinatal depression (Singla, Lawson, et al., Reference Singla, Lawson, Kohrt, Jung, Meng, Ratjen and Patel2021), but they do not adequately address the questions of “how” interventions can be successfully integrated and adopted across diverse contexts.

A review by Munodawafa (Reference Munodawafa, Mall, Lund and Schneider2018) discusses the context and mechanisms of successful implementation of interventions for perinatal depression. Additional evidence on intervention content for perinatal depression and its delivery in LMICs (Chowdhary et al., Reference Chowdhary, Sikander, Atif, Singh, Ahmad, Fuhr and Patel2014) and HICs (Singla, Lawson, et al., Reference Singla, Lawson, Kohrt, Jung, Meng, Ratjen and Patel2021) also exists; however, a combined global evidence on the evaluation of these interventions using implementation science constructs is still lacking. As NSHWs continue to be an important cadre for delivering services for perinatal depression, it is important to understand how best they can be mobilized. Proctor et al (Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger and Hensley2011) have proposed eight constructs for documenting implementation outcomes, namely: acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, penetration and sustainability. The current systematic review thus aims to synthesize evidence on the implementation process of NSHW-delivered psychosocial interventions for the management of perinatal depression and anxiety, as well as implementation outcomes based on the Proctor’s framework (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger and Hensley2011). The findings from this review will be valuable to policymakers, practitioners and academics working on task-sharing interventions to address perinatal mental health concerns.

Methods

The protocol for this review was registered in the National Institute for Health Research with the PROSPERO registration No. CRD42022306566 on March 10, 2022. This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review guidelines for reporting (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow and Moher2021).

Search strategy

The first (PS1) and second author (PS2) performed the search in three databases: PubMed, Web of Science and Cochrane Center Register of Controlled Trials. Search strategies were developed for each database using terms for five broad responses: “perinatal,” “common mental disorders,” “psychological interventions,” “nonspecialist” and “implementation” and filtered by date (1 January 2000 and 1 January 2022) (see Table 1). Full search strategy tailored to each database can be found in Supplementary File 1.

Table 1. Search strategy adapted for PubMed database

Screening

Two reviewers, PS1 and PS2, independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies identified through the database search. The full text of each article was then reviewed for eligibility.

Data extraction

Data relevant to this review were extracted from selected papers into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. In the first step, the selected papers were evenly distributed between the two reviewers, PS1 and PS2. Each reviewer independently extracted relevant information and categorized it under the following headings: author, year, setting, design, intervention details, delivery agents, training, supervision, feasibility, acceptability, fidelity, barriers, facilitators, appropriateness, adoption, implementation cost, penetration and sustainability. In the subsequent step, PS1 and PS2 cross-reviewed each other’s data extraction tables to verify their accuracy and completeness. Any disagreements between the reviewers were discussed with AW.

Quality assessment

PS1 appraised all studies and discussed any confusion with AW. The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist was used for qualitative studies (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018). The CASP checklist examines methods, study design, positionality, data collection and analysis procedures where studies are rated “yes,” “no,” “insufficient” or “not applicable.” For quantitative and mixed-method studies, an assessment tool designed and used by Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Mohammed, Shanthosh, News, Laba, Hackett and Jan2019) was used. Studies were rated as “yes,” “no,” “partially,” “unclear” or “not applicable” under domains such as planning, design and conduct and reporting stages. Both the checklists do not use any quantitative scoring system.

Data synthesis

Narrative synthesis was used to synthesize data on intervention implementation (Popay et al., Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers and Duffy2006). We initiated a preliminary synthesis of the data as per the eight constructs of Proctor’s framework (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger and Hensley2011) and explored relationships based on the intervention characteristics and study design. Where information was missing under certain outcomes, additional articles from the same studies were examined. Six additional articles (Glavin et al., Reference Glavin, Smith, Sorum and Ellefsen2010a; Segre et al., Reference Segre, Stasik, O’Hara and Arndt2010; Segre et al., Reference Segre, Brock and O’Hara2015; Lund et al., Reference Lund, Schneider, Garman, Davies, Munodawafa, Honikman and Susser2020; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Lund and Schneider2022; Yator et al., Reference Yator, Khasakhala, Stewart and Kumar2022) related to the included studies (Glavin et al., Reference Glavin, Smith, Sorum and Ellefsen2010b; Brock et al., Reference Brock, O’Hara and Segre2017; Boisits et al., Reference Boisits, Abrahams, Schneider, Honikman, Kaminer and Lund2021; Yator et al., Reference Yator, Kagoya, Khasakhala, John-Stewart and Kumar2021) were reviewed for additional data. This review focused on the implementation process outcomes; hence, a meta-analysis was not conducted.

Results

Study selection

A total of 885 studies were retrieved, with 117 duplicates. After screening the titles/abstracts, 128 studies were reviewed in full and 56 met the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion included inappropriate interventions, study design, specialist-delivered, hospital settings or language other than English (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Quality assessment

Altogether, 15 qualitative studies were assessed based on the CASP checklist. While most qualitative studies provided clear objectives, methodology and findings, there was inadequate reporting on the researcher’s positionality (60%), the value of the research (46.66%) and ethical issues (40%). A few studies focused on process documentation (Eappen et al., Reference Eappen, Aguilar, Ramos, Contreras, Prom, Scorza and Galea2018; Yator et al., Reference Yator, Kagoya, Khasakhala, John-Stewart and Kumar2021), adaptation and development of interventions (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, McKee and Jankowski2004); therefore, the study methods and data analysis were not applicable.

Overall, studies employing quantitative and mixed methods (n = 41) had adequately described their purpose (n = 39), interventions (n = 38) and study methods (n = 34). Implementation outcomes as per Proctor’s framework were reported partially by 36 studies with most examining feasibility, training and supervision outcomes. The included trials and pilot studies poorly reported on study team (n = 11), transparency of data analysis (n = 9) and protocol registration (n = 13) (see Supplementary File 2).

Description of studies

Twenty-four studies were published in HICs, followed by LMICs (n = 23) and upper middle-income countries (n = 9). Most studies were quantitative (n = 30), followed by qualitative (n = 15) and mixed methods (n = 10). Studies ranged from intervention development to implementation and effectiveness testing. One study reported it as a prevention intervention (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, McKee and Jankowski2004), but the reference article (Miranda and Muñoz, Reference Miranda and Muñoz1994) clarified that it targeted mild depression, justifying its inclusion. Details are given in Table 2.

Table 2. Study description and key characteristics of intervention

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; IPT, interpersonal therapy; N/A, not available.

Implementation process

Intervention details

Most interventions targeted postnatal depression (n = 26), followed by perinatal (n = 22), antenatal (n = 5) and maternal depression (n = 3). Anxiety (Prendergast and Austin, Reference Prendergast and Austin2001; Boisits et al., Reference Boisits, Abrahams, Schneider, Honikman, Kaminer and Lund2021), parenting (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Kaim, Le, McDonald, Mittinty, Lynch and Sawyer2019; Husain et al., Reference Husain, Kiran, Fatima, Chaudhry, Husain, Shah and Chaudhry2021), infant development (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, McKee and Jankowski2004) and mother–infant relationship (Horowitz et al., Reference Horowitz, Murphy, Gregory, Wojcik, Pulcini and Solon2013; Atif, Bibi, et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters and Rahman2019) were also addressed in some interventions. Cognitive behavioral therapy was the most widely used approach (n = 28), followed by problem-solving therapy (n = 5) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) (n = 4). Telephone-based interventions provided peer support (n = 4), psychoeducation (n = 1) or IPT sessions (n = 2). Most interventions (six studies missing information) were delivered in-person at home, health facilities or community centers (n = 40), followed by remote (n = 8) and hybrid sessions (n = 2). Session lasted between 15 min and 2 h, with individual sessions generally being shorter. Refer to Table 2 for further details.

Delivery agents and their characteristics

Nurses/midwives (n = 24) were the most common cadres, followed by peers (n = 15), community health workers (CHWs) (n = 14), school teachers/local priests (n = 1) (Notiar et al., Reference Notiar, Jidong, Hawa, Lunat, Shah, Bassett and Husain2021) and graduate students (n = 1) (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, McKee and Jankowski2004). One study on intervention development did not mention the occupations of the NSHWs (Ng’oma et al., Reference Ng’oma, Meltzer-Brody, Chirwa and Stewart2019). Nurses/midwives typically held diplomas or master’s degrees or had extensive nursing experience, but no mental health training. Peers in LMICs were local married women sharing similar culture and socioeconomic status (Atif, Bibi, et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters and Rahman2019; Atif, Nisar, et al., Reference Atif, Nisar, Bibi, Khan, Zulfiqar, Ahmad and Rahman2019; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla and Patel2019; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Waqas, Nisar, Nazir, Sikander and Atif2021). Peers in HICs were matched by lived experience of perinatal depression (Dennis, Reference Dennis2003, Reference Dennis2010, Reference Dennis2013, Reference Dennis2014; Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011; Amani et al., Reference Amani, Merza, Savoy, Streiner, Bieling, Ferro and Van Lieshout2021). In Zimbabwe, health facilities providing prevention services for mother-to-child HIV transmission trained and mobilized HIV-infected women as peer counselors (Chibanda et al., Reference Chibanda, Shetty, Tshimanga, Woelk, Stranix-Chibanda and Rusakaniko2014). CHWs were often local females, with at least secondary education and 2.5 years of work experience in maternal and child health programs.

Training

Forty-three studies reported details on the training for the NSHWs, while information from two studies (Brock et al., Reference Brock, O’Hara and Segre2017; Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Kaim, Le, McDonald, Mittinty, Lynch and Sawyer2019) were obtained from secondary publications (Segre et al., Reference Segre, Brock and O’Hara2015). Training duration ranged from 4 h to 2weeks, some with follow-up sessions and refresher training. Lectures, audiovisuals and discussions were common methods used for theoretical content delivery, alongside role play, session observation (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Grigoriadis, Zupancic, Kiss and Ravitz2020; Layton et al., Reference Layton, Bendo, Amani, Bieling and Van Lieshout2020) or internships (Chibanda et al., Reference Chibanda, Shetty, Tshimanga, Woelk, Stranix-Chibanda and Rusakaniko2014; Atif, Bibi, et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters and Rahman2019; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla and Patel2019) to enhance skills. The use of technology such as telephones and tablets for training was also described in some studies (Dennis, Reference Dennis2003, Reference Dennis2010, Reference Dennis2013, Reference Dennis2014; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Akhtar, Hamdani, Atif, Nazir, Uddin and Zafar2019; Nisar et al., Reference Nisar, Yin, Yiping, Lanting, Zhang, Wang and Li2020; Nisar et al., Reference Nisar, Yin, Nan, Luo, Han, Yang and Li2022). Training content focused on the assessment and treatment of mental health conditions based on a structured manual/protocol and was usually delivered by psychiatrists, psychologists or specialists.

Supervision

The majority of the studies (n = 35) reported on supervision, with details of two studies retrieved (Brock et al., Reference Brock, O’Hara and Segre2017; Leocata, Kleinman, et al., Reference Leocata, Kleinman and Patel2021) from secondary publications (Singla et al., Reference Singla, Lazarus, Atif, Sikander, Bhatia, Ahmad and Rahman2014; Segre et al., Reference Segre, Brock and O’Hara2015; Atif et al., Reference Atif, Krishna, Sikander, Lazarus, Nisar, Ahmad and Rahman2017). Supervision primarily occurred face-to-face in-group settings on a weekly (n = 10), fortnightly (n = 1) or monthly (n = 11) basis or by need (n = 3) (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Judd and Hodgins2005; Van Lieshout et al., Reference Van Lieshout, Layton, Feller, Ferro, Biscaro and Bieling2020; Ransing et al., Reference Ransing, Kukreti, Raghuveer, Mahadevaiah, Puri, Pemde and Deshpande2021). Electronic mediums such as telephones (Morrell et al., Reference Morrell, Slade, Warner, Paley, Dixon, Walters and Nicholl2009; Dennis, Reference Dennis2013, Reference Dennis2014; Posmontier et al., Reference Posmontier, Neugebauer, Stuart, Chittams and Shaughnessy2016; Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Grigoriadis, Zupancic, Kiss and Ravitz2020), emails (Dennis, Reference Dennis2014) and apps (Eappen et al., Reference Eappen, Aguilar, Ramos, Contreras, Prom, Scorza and Galea2018; Atif, Nisar, et al., Reference Atif, Nisar, Bibi, Khan, Zulfiqar, Ahmad and Rahman2019; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Akhtar, Hamdani, Atif, Nazir, Uddin and Zafar2019; Yator et al., Reference Yator, Kagoya, Khasakhala, John-Stewart and Kumar2021) were also utilized. Supervision details (duration, frequency or content) were missing in nine studies (Slade et al., Reference Slade, Morrell, Rigby, Ricci, Spittlehouse and Brugha2010; Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Cust and Boath2020; Layton et al., Reference Layton, Bendo, Amani, Bieling and Van Lieshout2020; Leocata, Kleinman, et al., Reference Leocata, Kleinman and Patel2021; Leocata, Kaiser, et al., Reference Leocata, Kaiser and Puffer2021; Notiar et al., Reference Notiar, Jidong, Hawa, Lunat, Shah, Bassett and Husain2021; Singla, MacKinnon, et al., Reference Singla, MacKinnon, Fuhr, Sikander, Rahman and Patel2021; Van Lieshout et al., Reference Van Lieshout, Layton, Savoy, Haber, Feller, Biscaro and Ferro2022). Supervisors were predominantly mental health professionals, although peer-led supervision was common in studies involving peers as NSHWs. Some studies (n = 6) adopted a cascade model, where experts supervised local trainers who then supervised implementers (Atif et al., Reference Atif, Lovell, Husain, Sikander, Patel and Rahman2016; Atif, Bibi, et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters and Rahman2019; Atif, Nisar, et al., Reference Atif, Nisar, Bibi, Khan, Zulfiqar, Ahmad and Rahman2019; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Akhtar, Hamdani, Atif, Nazir, Uddin and Zafar2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss and Rahman2019; Leocata, Kleinman, et al., Reference Leocata, Kleinman and Patel2021). Supervision sessions mainly focused on reviewing intervention content, followed by practice sessions through role play, discussion on challenges faced during service delivery and potential strategies to manage burnout.

Implementation outcomes based on Proctor’s framework

An overview of the outcomes is provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Implementation outcomes as per the Proctor’s Framework

Note: Texts written in bold were extracted from secondary article.

Abbreviations: BDI – Beck’s Depression Inventory; CES-D – Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; EPDS – Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; IPT – Interpersonal Therapy; N/A – Not available; NSHW – Nonspecialist health worker; PHQ-9 – Patient Health Questionnaire-9; THP – Thinking Healthy Program.

Feasibility of interventions

Proctor’s framework defines feasibility in terms of recruitment, retention and adherence to treatment. Altogether, 32 studies reported feasibility outcomes. Additionally, seven secondary articles were reviewed to extract data on feasibility.

Recruitment and retention of service users

Recruitment of perinatal women primarily occurred at the health facility, but social media and advertisements were also utilized. Out of 43 studies that reported screening tools, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was the most common (n = 24), followed by the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (n = 10), Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (n = 2), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (n = 2), Beck’s Depression Inventory (n = 2), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (n = 1), Self-Reporting Questionnaire (n = 1) and Whooley’s questionnaire (n = 1). Studies were able to recruit between 67 and 94% of the total eligible women. A secondary article reported the lowest recruitment rate of 19% and cited language barriers, presence of comorbid conditions and experience of pregnancy loss as reasons for poor recruitment (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Schneider, Garman, Davies, Munodawafa, Honikman and Susser2020). Strict inclusion criteria often made recruitment a challenging and slow process (Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011), which was further exacerbated by unprecedented events such as COVID-19 (Amani et al., Reference Amani, Merza, Savoy, Streiner, Bieling, Ferro and Van Lieshout2021).

Studies collecting data at multiple time-points generally had a 15–38% dropout at end line, but in some cases, dropout was as high as 91% (Husain et al., Reference Husain, Kiran, Fatima, Chaudhry, Husain, Shah and Chaudhry2021). Retention was especially poor in studies that extended over 6 months in duration and studies involving urban minority low-income population (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, McKee and Jankowski2004; Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Kaim, Le, McDonald, Mittinty, Lynch and Sawyer2019). Common reasons for poor retention were contact loss, hospitalization, time/interest constraints and program discontinuation.

Recruitment and retention of service providers

Five included articles (Roman et al., Reference Roman, Gardiner, Lindsay, Moore, Luo, Baer and Paneth2009; Atif, Nisar, et al., Reference Atif, Nisar, Bibi, Khan, Zulfiqar, Ahmad and Rahman2019; Van Lieshout et al., Reference Van Lieshout, Layton, Feller, Ferro, Biscaro and Bieling2020; Nakku et al., Reference Nakku, Nalwadda, Garman, Honikman, Hanlon, Kigozi and Lund2021; Ransing et al., Reference Ransing, Kukreti, Raghuveer, Mahadevaiah, Puri, Pemde and Deshpande2021) and one secondary article (Atif et al., Reference Atif, Krishna, Sikander, Lazarus, Nisar, Ahmad and Rahman2017) reported the feasibility of recruiting, training and retaining the NSHWs. The feasibility of training and retaining NSHWs ranged from 67% to 100% (Roman et al., Reference Roman, Gardiner, Lindsay, Moore, Luo, Baer and Paneth2009; Van Lieshout et al., Reference Van Lieshout, Layton, Feller, Ferro, Biscaro and Bieling2020; Nakku et al., Reference Nakku, Nalwadda, Garman, Honikman, Hanlon, Kigozi and Lund2021; Nisar et al., Reference Nisar, Yin, Nan, Luo, Han, Yang and Li2022). Common challenges pertaining to the retention of NSHWs included workload, transfer to different health facility, poor competency, migration, personal circumstances and poor acceptance by service users.

Service users’ adherence to treatment

The treatment completion rate ranged from 31 to 100%. A study conducted in Afghanistan had the lowest treatment participation and retention, citing household commitments, refusal from family, dissatisfaction and unavailability of health staff (Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Chaudhery, Ahmadzai, Rodriguez Gomez, Rodriguez Gomez, van Heyningen and Chopra2020). An individual-focused intervention that had six sessions delivered at home had a treatment completion rate as high as 100% (Prendergast and Austin, Reference Prendergast and Austin2001). Adherence was higher (95%) in a health facility-based intervention when embedded within regular postnatal visits (Chibanda et al., Reference Chibanda, Shetty, Tshimanga, Woelk, Stranix-Chibanda and Rusakaniko2014). For a telephone-based intervention, the treatment completion rate was as high as 98% once the treatment was initiated (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Grigoriadis, Zupancic, Kiss and Ravitz2020). This was the opposite for an app-based intervention where the user engagement reduced over time (from 64% to 14% over 16 weeks) (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Kaim, Le, McDonald, Mittinty, Lynch and Sawyer2019).

Postnatal sessions were frequently missed, partly due to the tradition of mothers returning to their maternal home for postnatal recovery. As this often involved relocation, home-based sessions became logistically challenging (Leocata, Kleinman, et al., Reference Leocata, Kleinman and Patel2021). One secondary article found as low as 28% attendance in postnatal sessions (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Schneider, Garman, Davies, Munodawafa, Honikman and Susser2020). Sickness, experiencing loss, lack of time, stigma, fear of breaking confidentiality and dissatisfaction with the services or NSHWs were cited as reasons for not engaging in care.

Acceptability

Twenty-four reviewed studies and seven secondary studies reported on acceptability.

Service providers

Self-driven, empathic and competent NSHWs were identified as key drivers to the intervention’s success. NSHWs delivering interventions in person or electronically reported positive experiences, viewing the intervention delivery as an opportunity to serve others and expand their social network (Singla et al., Reference Singla, Ratjen, Krishna, Fuhr and Patel2020). They also perceived that the training and intervention delivery experience enhanced their knowledge, skills and confidence, contributing to personal development (Appleby et al., Reference Appleby, Hirst, Marshall, Keeling, Brind, Butterworth and Lole2003; Dennis, Reference Dennis2013; Glavin et al., Reference Glavin, Smith, Sorum and Ellefsen2010b; Layton et al., Reference Layton, Bendo, Amani, Bieling and Van Lieshout2020; Boisits et al., Reference Boisits, Abrahams, Schneider, Honikman, Kaminer and Lund2021; Kukreti et al., Reference Kukreti, Ransing, Raghuveer, Mahdevaiah, Deshpande, Kataria and Garg2022). Group supervision and tailored feedback helped address challenges and build confidence. Peer supervision, although beneficial, was less effective than expert supervision (Singla et al., Reference Singla, Ratjen, Krishna, Fuhr and Patel2020). Overall, NSHWs expressed satisfaction and willingness to engage in the future. Lack of confidence (Munodawafa et al., Reference Munodawafa, Lund and Schneider2017; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Cust and Boath2020), emotional burden (Dennis, Reference Dennis2013; Munodawafa et al., Reference Munodawafa, Lund and Schneider2017) and resistance from family (Atif et al., Reference Atif, Lovell, Husain, Sikander, Patel and Rahman2016) hindered implementation.

Culturally appropriate content, illustrations and scripted guides better enabled NSHWs to deliver sessions (Dennis, Reference Dennis2014; Boisits et al., Reference Boisits, Abrahams, Schneider, Honikman, Kaminer and Lund2021; Leocata, Kaiser, et al., Reference Leocata, Kaiser and Puffer2021). However, one study found that the violence-focused content was only beneficial for a specific demographic, suggesting its potential unsuitability as a universal intervention component (Ransing et al., Reference Ransing, Kukreti, Raghuveer, Mahadevaiah, Puri, Pemde and Deshpande2021).

Service users

Engaging in the intervention yielded both physical and emotional benefits in service users. They expressed satisfaction with the NSHWs assigned to them. Educated, middle-aged females sharing similar language and culture were mostly preferred as NSHWs (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, McKee and Jankowski2004; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Lazarus, Atif, Sikander, Bhatia, Ahmad and Rahman2014; Nyatsanza et al., Reference Nyatsanza, Schneider, Davies and Lund2016). A strong match with the NSHW led to higher receptivity, trust and a strong bond (Dennis, Reference Dennis2010; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Cust and Boath2020). Nurses were perceived as competent by 99% of the service users in one study (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Grigoriadis, Zupancic, Kiss and Ravitz2020). However, NSHWs who read from manuals instead of engaging, did not give time, made invalidating remarks or set unrealistic hopes were seen as unhelpful (Slade et al., Reference Slade, Morrell, Rigby, Ricci, Spittlehouse and Brugha2010; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Lund and Schneider2022).

Community-based health facility interventions were acceptable, and the provision of childcare eased attendance (Van Lieshout et al., Reference Van Lieshout, Layton, Feller, Ferro, Biscaro and Bieling2020). Challenges included ill-equipped facilities and long waiting hours (Nyatsanza et al., Reference Nyatsanza, Schneider, Davies and Lund2016). Telephone-based support was accessible and alleviated concerns about transportation, time and childcare (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Sawatphanit, Suwansujarid, Stidham, Drew and Creswell2013; Posmontier et al., Reference Posmontier, Neugebauer, Stuart, Chittams and Shaughnessy2016). For a mobile app-based intervention, a chat page where participants could communicate with NSHWs was the most used feature compared to a mood tracker or video content (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Kaim, Le, McDonald, Mittinty, Lynch and Sawyer2019).

Appropriateness

Small group training with a mix of classroom-based and practical sessions was perceived as most beneficial by the NSHWs (Layton et al., Reference Layton, Bendo, Amani, Bieling and Van Lieshout2020). Both electronic-based and in-person training were deemed useful (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Akhtar, Hamdani, Atif, Nazir, Uddin and Zafar2019; Nisar et al., Reference Nisar, Yin, Nan, Luo, Han, Yang and Li2022). NSHWs felt that these trainings enhanced their knowledge, confidence and readiness for their role (Dennis, Reference Dennis2014; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Aubry, Rider, Mazzeo and Kinser2020; Yator et al., Reference Yator, Kagoya, Khasakhala, John-Stewart and Kumar2021).

Interventions complementing the existing system and tailored to contextual issues were deemed more appropriate (Nyatsanza et al., Reference Nyatsanza, Schneider, Davies and Lund2016; Ransing et al., Reference Ransing, Kukreti, Raghuveer, Mahadevaiah, Puri, Pemde and Deshpande2021). NSHWs reported difficulty with issues outside the intervention’s focus (Munodawafa et al., Reference Munodawafa, Lund and Schneider2017; Leocata, Kaiser, et al., Reference Leocata, Kaiser and Puffer2021). Scripts provided structure, but some NSHWs found them constraining, highlighting a need for flexibility. Individual sessions allowed for discussing personal concerns and receiving tailored support (Slade et al., Reference Slade, Morrell, Rigby, Ricci, Spittlehouse and Brugha2010), while group sessions fostered connections and normalized problems (Rahman, Reference Rahman2007; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Aubry, Rider, Mazzeo and Kinser2020; Van Lieshout et al., Reference Van Lieshout, Layton, Feller, Ferro, Biscaro and Bieling2020). Service users preferred small groups and hesitated to engage in larger groups (Notiar et al., Reference Notiar, Jidong, Hawa, Lunat, Shah, Bassett and Husain2021).

Due to safety concerns and family resistance, home visits were less preferred by NSHWs (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, McKee and Jankowski2004; Nyatsanza et al., Reference Nyatsanza, Schneider, Davies and Lund2016; Munodawafa et al., Reference Munodawafa, Lund and Schneider2017; Leocata, Kleinman, et al., Reference Leocata, Kleinman and Patel2021). Phone- and app-based interventions were considered useful, user-friendly and less stigmatizing, but women reported discomfort receiving calls in others’ presence and missing each other’s calls (Dennis, Reference Dennis2010; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Sawatphanit, Suwansujarid, Stidham, Drew and Creswell2013). The chat function in apps was particularly useful for asking questions (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Kaim, Le, McDonald, Mittinty, Lynch and Sawyer2019).

For peers, incentives in the forms of financial payments, transportation and communication compensation, gifts or household items were cited as one of the key motivators for engaging in service delivery (Atif, Bibi, et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters and Rahman2019; Ng’oma et al., Reference Ng’oma, Meltzer-Brody, Chirwa and Stewart2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss and Rahman2019; Leocata, Kleinman, et al., Reference Leocata, Kleinman and Patel2021).

Programmatic adoption

Only nine studies reported on programmatic adoption. Brief interventions were easier to integrate into routine service at the health facility (Eappen et al., Reference Eappen, Aguilar, Ramos, Contreras, Prom, Scorza and Galea2018; Boisits et al., Reference Boisits, Abrahams, Schneider, Honikman, Kaminer and Lund2021). Intervention delivery was easier for NSHWs when they linked their affiliation with the health facility (Atif, Nisar, et al., Reference Atif, Nisar, Bibi, Khan, Zulfiqar, Ahmad and Rahman2019). Health facility-based interventions had smooth functioning only when the health workers were cooperative. However, this placed an additional burden on NSHWs, requiring them to manage logistical, administrative and coordination tasks alongside providing psychological support (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, McKee and Jankowski2004; Munodawafa et al., Reference Munodawafa, Lund and Schneider2017; Atif, Bibi, et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters and Rahman2019). Lack of support from health facility staff (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, McKee and Jankowski2004; Munodawafa et al., Reference Munodawafa, Lund and Schneider2017), unequipped and inaccessible health facilities (Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, McKee and Jankowski2004; Eappen et al., Reference Eappen, Aguilar, Ramos, Contreras, Prom, Scorza and Galea2018; Atif, Nisar, et al., Reference Atif, Nisar, Bibi, Khan, Zulfiqar, Ahmad and Rahman2019; Yator et al., Reference Yator, Kagoya, Khasakhala, John-Stewart and Kumar2021), lack of compensation and work burden (Atif, Bibi, et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters and Rahman2019; Atif, Nisar, et al., Reference Atif, Nisar, Bibi, Khan, Zulfiqar, Ahmad and Rahman2019; Ng’oma et al., Reference Ng’oma, Meltzer-Brody, Chirwa and Stewart2019; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Ratjen, Krishna, Fuhr and Patel2020; Yator et al., Reference Yator, Kagoya, Khasakhala, John-Stewart and Kumar2021) hindered the implementation and adoption of the intervention in routine care. On the other hand, developing a maternal mental health guideline and creating a dedicated position within the health system were identified as facilitators for the integration of maternal mental health intervention into the health system (Ng’oma et al., Reference Ng’oma, Meltzer-Brody, Chirwa and Stewart2019).

Fidelity

A total of 18 studies reported on fidelity. Fidelity was assessed through the rating of session observations or audio recordings, or activity logs using guidelines, checklists or tools such as the Therapeutic Quality Scale (Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla and Patel2019; Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss and Rahman2019; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Ratjen, Krishna, Fuhr and Patel2020; Leocata, Kaiser, et al., Reference Leocata, Kaiser and Puffer2021) and Interpersonal Inventory Rating Scale (Yator et al., Reference Yator, Kagoya, Khasakhala, John-Stewart and Kumar2021). Fidelity assessments were mainly done to ensure adherence to the study protocol (Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla and Patel2019), intervention content, use of clinical skills (Prendergast and Austin, Reference Prendergast and Austin2001; Nyatsanza et al., Reference Nyatsanza, Schneider, Davies and Lund2016; Munodawafa et al., Reference Munodawafa, Lund and Schneider2017; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla and Patel2019; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm and Zelkowitz2019) and to identify challenges leading to targeted training/supervision (Rahman, Reference Rahman2007; Munodawafa et al., Reference Munodawafa, Lund and Schneider2017). Higher scores in these assessments meant higher fidelity to the intervention, while lower scores generally indicated a lack of competency to provide care. While many studies reported that NSHWs had good adherence to the intervention (Prendergast and Austin, Reference Prendergast and Austin2001; Slade et al., Reference Slade, Morrell, Rigby, Ricci, Spittlehouse and Brugha2010; Munodawafa et al., Reference Munodawafa, Lund and Schneider2017; Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm and Zelkowitz2019; Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Grigoriadis, Zupancic, Kiss and Ravitz2020), four studies reported challenges such as NSHWs lacking effective communication skills and struggling to adequately explain the intervention component or follow the manual (Eappen et al., Reference Eappen, Aguilar, Ramos, Contreras, Prom, Scorza and Galea2018; Layton et al., Reference Layton, Bendo, Amani, Bieling and Van Lieshout2020; Boisits et al., Reference Boisits, Abrahams, Schneider, Honikman, Kaminer and Lund2021; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Lund and Schneider2022).

Implementation cost

Altogether, five studies in the review reported cost analyses, of which three focused on the cost-effectiveness of the psychological intervention, whereas the other two focused on the training of NSHWs. Two studies reporting on the cost-effectiveness of the THP intervention in Pakistan and India reported that the intervention was highly cost-effective, with an estimation of $1 per beneficiary (Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla and Patel2019) and each unit of improvement on the PHQ-9 score costing between $2 and 20 (Sikander et al., Reference Sikander, Ahmad, Atif, Zaidi, Vanobberghen, Weiss and Rahman2019). Another study in Nigeria comparing high-intensity over low-intensity treatment found no difference in terms of cost effectiveness (Gureje et al., Reference Gureje, Oladeji, Montgomery, Araya, Bello, Chisholm and Zelkowitz2019). A study in the United Kingdom found that training NSHWs improved their skills and led to positive changes in their clinical practices without increasing the overall cost of service delivery (Appleby et al., Reference Appleby, Hirst, Marshall, Keeling, Brind, Butterworth and Lole2003). Another study comparing the cost of technology-assisted training against in-person training found technology-assisted training more cost-effective by 30% (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Akhtar, Hamdani, Atif, Nazir, Uddin and Zafar2019).

Penetration

Proctor’s framework defines penetration as a level of institutionalization and maintenance of treatment at the systems level, usually occurring in the mid to late stages of implementation. This information was missing in the reviewed studies.

Sustainability

Sustainability as institutionalization of treatment was not reported in the reviewed studies; however, four studies briefly outlined sustainability concerns. For example, engaging in short-lived projects affected NSHWs’ motivation to engage fully (Atif, Bibi, et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters and Rahman2019). Service users and their families expressed similar worries (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Sawatphanit, Suwansujarid, Stidham, Drew and Creswell2013; Atif et al., Reference Atif, Lovell, Husain, Sikander, Patel and Rahman2016; Nyatsanza et al., Reference Nyatsanza, Schneider, Davies and Lund2016). One study reported treatment effects after 8 weeks (Brock et al., Reference Brock, O’Hara and Segre2017), while another reported retention of peer volunteers (68.88%) over 5 years, suggesting the sustainability of local NSHWs (Atif, Bibi, et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters and Rahman2019).

Discussion

There is a growing need for more evidence in implementation science, which focuses on translating theories into practice, identifying facilitators and barriers and developing strategies to overcome challenges (Rapport et al., Reference Rapport, Clay-Williams, Churruca, Shih, Hogden and Braithwaite2018; Bauer and Kirchner, Reference Bauer and Kirchner2020). Qualitative insights to document the implementation process are essential, as they can serve as a guideline to practitioners aiming to integrate perinatal mental health in their programs. We applied Proctor’s framework of implementation science, which outlines implementation constructs and analyzes outcomes in the early, mid and late stages (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger and Hensley2011), to report our findings. Our review found that most studies reported feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness and fidelity outcomes; however, very few evaluated cost, sustainability, adoption and penetration.

Our review indicates that acceptance and adherence were higher for interventions delivered at home or integrated in routine care when the NSHWs had matching characteristics with the service users. A strong bond with NSHWs was crucial, and without it, led to dissatisfaction with the program (Slade et al., Reference Slade, Morrell, Rigby, Ricci, Spittlehouse and Brugha2010). For NSHWs, receiving training and supervision was a capacity-building opportunity, which enhanced their knowledge, confidence and readiness for the helping role (Dennis, Reference Dennis2014; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Aubry, Rider, Mazzeo and Kinser2020). None of the NSHWs had prior experience in mental health, therefore indicating the need for intensive training and supervision to maintain competency, ensure treatment quality, maintain fidelity and address emotional burnout (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Hall, Pedersen, Ottman, Carswell, Van’t Hof and Schafer2021). Incompetency of service providers can cause unintended harm (Dennis, Reference Dennis2010); hence, some studies in our review assessed competency when recruiting the NSHWs (Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Stewart, Dennis, Hegadoren, Duffett-Leger and Watson2011; Dennis, Reference Dennis2013, Reference Dennis2014; Munodawafa et al., Reference Munodawafa, Lund and Schneider2017; Fuhr et al., Reference Fuhr, Weobong, Lazarus, Vanobberghen, Weiss, Singla and Patel2019; Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Grigoriadis, Zupancic, Kiss and Ravitz2020; Singla et al., Reference Singla, Ratjen, Krishna, Fuhr and Patel2020; Singla, MacKinnon, et al., Reference Singla, MacKinnon, Fuhr, Sikander, Rahman and Patel2021). Evidence also highlights the need for competency-based training in mental health to ensure quality and safety of the treatment (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Schafer, Willhoite, Van’t Hof, Pedersen, Watts and van Ommeren2020). A cross-country study in LMICs on Ensuring Quality in Psychological Support (EQUIP), an online platform to assess competency, found that competency-based training was helpful in reducing harmful behaviors and improving helpful behaviors of the NSHWs (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Shrestha, Akellot, Sepulveda, Luitel, Kasujja and Kohrt2023). Breuer et al. (Reference Breuer, Subba, Luitel, Jordans, De Silva, Marchal and Lund2018) found that regular supervision motivated the NSHWs to proactively screen and manage mental health problems. While supervision dosage can vary, quality supervision is arguably more important than the quantity of supervision (Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Petersen, Bhana and Rao2019).

Even when interventions are feasible, acceptable and effective, their adoption in the health system cannot be guaranteed (Bauer and Kirchner, Reference Bauer and Kirchner2020). Very few studies in this review reported on systems-level implementation outcomes, such as adoption or sustainability, and none reported on penetration. NSHWs were often in a voluntary position and were trained to integrate psychosocial intervention into their regular work. While there was a good receptivity of the intervention by the NSHWs, they expressed being demotivated and overburdened without incentives. Further, the temporary nature of these interventions raised concerns about their sustainability, often affecting the motivation of both the service providers and service users to engage in the intervention (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Sawatphanit, Suwansujarid, Stidham, Drew and Creswell2013; Atif et al., Reference Atif, Lovell, Husain, Sikander, Patel and Rahman2016; Nyatsanza et al., Reference Nyatsanza, Schneider, Davies and Lund2016; Atif, Bibi, et al., Reference Atif, Bibi, Nisar, Zulfiqar, Ahmed, LeMasters and Rahman2019).

Poor adoption and sustainability of evidence-based treatments pose significant challenges to address maternal mental health (Bauer and Kirchner, Reference Bauer and Kirchner2020). While Proctor’s framework situates sustainability in the later implementation stages, emerging discourse suggests it is a continuous process spanning pre-, during and post-implementation phases (Pluye et al., Reference Pluye, Potvin and Denis2004; Bergmark et al., Reference Bergmark, Bejerholm and Markström2018; Shelton et al., Reference Shelton, Cooper and Stirman2018). Program designers should proactively incorporate sustainability elements from inception, potentially through continuous stakeholder engagement to foster buy-in and cultivate an environment conducive to implementation. Strategies outlined by Vax et al. (Reference Vax, Gidugu, Farkas and Drainoni2021) offer valuable guidance for implementing interventions.

Scaccia et al. (Reference Scaccia, Cook, Lamont, Wandersman, Castellow, Katz and Beidas2015) emphasize the importance of assessing and ensuring “organizational readiness,” defined as having the willingness and capacity to implement the innovation for adoption and sustainability. Innovation that fits well with the needs, culture, context and capacity of the organization is more likely to be adopted (Scaccia et al., Reference Scaccia, Cook, Lamont, Wandersman, Castellow, Katz and Beidas2015; Vax et al., Reference Vax, Gidugu, Farkas and Drainoni2021). However, the pervasive stigma associated with mental health poses a threat to adoption. Structural stigma, marked by inadequate policies, political will and investment, limits service availability, (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Othieno, Okeyo, Aruwa, Kingora and Jenkins2013; Livingston, Reference Livingston2020) while community-level stigma delays help-seeking and reduces service utilization (Livingston, Reference Livingston2020). Addressing stigma therefore requires innovative strategies at multiple levels. At the systems level, careful planning, funding and evidence-based advocacy – supported by cost-effectiveness studies – are essential for political buy-in and institutionalization within the health system (Bergmark et al., Reference Bergmark, Bejerholm and Markström2018; Vax et al., Reference Vax, Gidugu, Farkas and Drainoni2021). Meanwhile, at the community level, sensitization and engagement activities can foster awareness and encourage service uptake (Ng’oma et al., Reference Ng’oma, Meltzer-Brody, Chirwa and Stewart2019; Subba et al., Reference Subba, Petersen Williams, Luitel, Jordans and Breuer2024).

The WHO’s guide for integration of perinatal mental health in maternal and child health services provides practical guidance for planners and policymakers on “what” actions can be taken to embed these interventions into routine care (WHO, 2022). However, a deeper understanding of “how” to implement these interventions in real-world settings and “what works and what does not” (including facilitators and barriers) remains essential. Despite the growing prominence of implementation science, the paucity of studies reporting process evaluation and implementation outcomes for perinatal depression interventions hinders the identification, replication and synthesis of evidence. Future studies could address this gap by using frameworks such as the Standard for Reporting Implementation Studies to report their findings, making them more visible and accessible (Pinnock et al., Reference Pinnock, Barwick, Carpenter, Eldridge, Grandes, Griffiths and Sta2017).

Limitations

The limitations of this review include the exclusion of non-English publications, which might have resulted in the omission of relevant articles. Second, this study conducted a narrative synthesis of the implementation constructs. For implementation constructs such as feasibility and fidelity that predominantly use quantitative measures, future research could consider conducting statistical analyses. Third, this review only focused on treatment interventions delivered by the NSHWs to the adult population. Given the wide engagement of NSHWs in prevention and promotion interventions globally and the focus across all age groups, this review could have excluded some important studies involving perinatal adolescents and girls.

Conclusion

This review synthesized evidence on implementation outcomes using Proctor’s framework to gain insights into the process, success and barriers of NSHW-delivered psychosocial interventions. Findings indicate that such interventions are well-accepted, and NSHWs can effectively deliver them when adequately trained, supervised and incentivized. However, there is a notable lack of studies exploring systemic factors influencing adoption, maintenance and sustainability. Further research is needed to elucidate the factors affecting the systems level integration of these interventions. Future implementers would benefit from employing implementation science frameworks to guide planning, execution and sustainability while considering various implementation factors across different stages.

Abbreviations

- CBT

-

cognitive behavioral therapy

- HIC

-

high-income countries

- HIT

-

high-intensity treatment

- IPT

-

interpersonal therapy

- LIT

-

low-intensity treatment

- LMIC

-

low- and middle-income countries

- NSHW

-

nonspecialist health workers

- PRISMA

-

preferred reporting items for systematic review

- WHO

-

World Health Organization

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.10010.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.10010.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, references and/or its supplementary files.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the ENHANCE Collaborative Learning Group members for their continuous support and feedback. The authors would also like to thank Alexandra Blackwell for her valuable assistance with language editing.

Author contribution

SS, AR, NPL and PS1 designed the study, and drafted the protocol. SS and PS1 developed the search strategy. PS1 and PS2 searched, screened title and abstracts, retrieved full texts and performed data extraction. PS1 performed quality assessment of included studies, synthesized data and drafted the manuscript under close supervision from AW. PS2 drafted the methods section. AR, NPL and AW provided initial feedback to the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript and gave approval for submission.

Financial support

This study was supported under financial aid from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), UK’s RIGHT CALL 2 NIHR200817 ENHANCE: Scaling-up Care for Perinatal Depression through Technological Enhancements to the ‘Thinking Healthy Program’ (RIGHT CALL 2 NIHR200817). Further information is available at https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR200817. The funding agency has no role in the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data or the decision to submit the report of publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

Date: 11 August 2024

To:

Prof. Judy Bass and Prof. Dixon Chibanda,

Co-Editors-in-Chief

Global Mental health

Re: Submission of manuscript titled “Feasibility and acceptability of community based psychosocial interventions delivered by non-specialists for perinatal common mental disorders: A systematic review using an implementation science framework”

Dear Prof. Bass and Prof. Chibanda,

My co-authors and I are pleased to submit a manuscript entitled “Feasibility and acceptability of community based psychosocial interventions delivered by non-specialists for perinatal common mental disorders: A systematic review using an implementation science framework” for your consideration for publication in the Global Mental Health.

There is strong evidence that the non-specialist health workers (NSHWs) can effectively deliver psychosocial interventions for perinatal depression and anxiety globally. However, most of these studies have focused on the effectiveness evaluation. Few studies have individually reported lessons, challenges, facilitators and barriers however, a synthesis of these findings from a global perspective is missing.

There is strong evidence that non-specialist health workers (NSHWs) can effectively deliver psychosocial interventions for perinatal depression and anxiety globally. However, most studies have focused on effectiveness evaluation. While some studies have individually reported lessons, challenges, facilitators, and barriers, a synthesis of these findings from a global perspective is missing.

In this review, we examined all original publications relating to the delivery of psychosocial interventions in community and primary healthcare settings without geographical or study design limitations. We used Proctor’s implementation science framework to synthesize findings from 56 reviewed articles under eight constructs: feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness, adoption, cost-effectiveness, fidelity, penetration, and sustainability. Our review shows that NSHWs should not only be trained and supervised but also adequately incentivized. The acceptance of NSHW-delivered interventions was higher when the intervention was culturally appropriate and when the NSHWs were culturally aware and sensitive. Similarly, treatment adherence was higher for individual-focused home-based interventions or when the intervention was embedded in routine healthcare. Few studies reported on cost-effectiveness or addressed institutionalization of the interventions at the systemic level. The insights we’ve gathered into the processes, successes, and barriers of NSHW-delivered interventions can be valuable for policymakers, healthcare administrators, and practitioners in designing more effective and sustainable perinatal mental health programs. Additionally, these findings can guide researchers to focus more on the systemic facilitators and barriers to integration and institutionalization of such programs, addressing a critical gap in the current literature.

We declare that this manuscript represents original data and is not under review at any other journal. All authors have approved the manuscript for submission, and there are no competing interests.

We believe this manuscript will be of interest to Global Mental Health’s readers and request your kind consideration for review and publication in your valued journal.

Sincerely,

Prasansa Subba [Corresponding Author]

University of Liverpool/Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal

Prasansa.Subba@liverpool.ac.uk