Introduction

This paper explores the role of domestic gardens within the everyday lives of people living with dementia and their households. The importance of domestic gardens and outdoor spaces for wellbeing is now widely recognised and has been brought to the fore during the COVID-19 global pandemic (Corley et al., Reference Corley, Okely, Taylor, Page, Welstead, Skarabela, Redmond, Cox and Russ2021), still ongoing at the time of writing. The significance of domestic gardens for wellbeing continues into later life (Scott et al., Reference Scott, Masser and Pachana2020) and, in the United Kingdom (UK), gardening is most popular among older age groups (Seddon, Reference Seddon2011).

However, little is known about how living with dementia affects everyday experiences of domestic gardens (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Keady, Tsekleves and Obe2021). This contrasts with a growing body of research in care home and community contexts which highlights the ongoing significance of gardens for supporting wellbeing, identity and social relationships (for review, see Whear et al., Reference Whear, Thompson Coon, Bethel, Abbott, Stein and Garside2014; Barrett and Evans, Reference Barrett and Evans2019). There is a tendency in some previous literature on dementia and gardens to focus on gardening activities as supporting the maintenance of identity and personhood versus a loss of identity in relation to the impairment of gardening abilities (e.g. Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Skovdahl and Engstrom2013; Chung et al., Reference Chung, Ellis-Hill and Coleman2017). This often entails a focus specifically on gardening, rather than multiple garden practices and ways of encountering gardens. There is also a tendency in some previous literature to represent garden use as an individualised activity (Raisborough and Bhatti, Reference Raisborough and Bhatti2007), where safety, risk and individual ‘outcomes’ take priority over the relational dimensions which shape garden practices (Rendell and Carroll, Reference Rendell and Carroll2015; Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Courtney-Pratt and Campbell2018). As such, little is known about how household relationships enable or constrain the garden practices of people living with dementia (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Keady, Tsekleves and Obe2021).

To begin to remedy this picture, this paper draws on practice and relational approaches. Rather than viewing identity as something that is lost or maintained, these approaches emphasise that identities are always in a process of becoming, emerging from everyday actions and interactions between human and non-human actors (Lovatt, Reference Lovatt2018). Drawing on Bourdieu's theory of social practice, Kontos (Reference Kontos2004) describes embodied agency and spontaneity in people living with dementia's engagement with their social and material environments. However, she emphasises that these embodied ways of being-in-the-world are also shaped by habitus – ingrained, tacit dispositions that reflect social location. More recently, Kontos et al. (Reference Kontos, Miller and Kontos2017a: 182) have called for attention to ‘relational citizenship’ in the context of dementia, recognising the ‘reciprocal nature of engagement and the centrality of capacities, senses, and experiences of bodies to the exercise of human agency and interconnectedness’. Building on these theoretical insights, this paper examines the relational nature of domestic garden uses when living with dementia, exploring different ‘ways of being’ in the garden, categorised as: doing and working in the garden; being in and sensing; and playing, empowerment and agency.

The sociology of domestic gardens

Domestic gardens have been described as an extension of the home, situated within everyday practices of home-making; ‘daily routines and activities (necessarily embodied, gendered, and aged) rooted in time and space that contribute towards the creation and re-creation of the domestic sphere’ (Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006: 321). The garden, like the home, is a space that is unfinished, always in a state of ‘becoming’ (Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006) and ‘movement’ (Pink, Reference Pink2012) as the garden changes over time. Domestic gardens are part of the temporal and spatial ordering of home, but also the construction of home as a ‘state of being’ and a phenomenological sense of ‘being at home’ in the world (Jackson, Reference Jackson1995). Like the home, the garden is a space for the ‘construction and projection of identity’ (Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006: 323) through material connections to memories and biographies, and implications for status and distinction through the display of gardens (Taylor, Reference Taylor2008). Anthropological literature has also highlighted the garden as a sensory space and gardening as a practice that involves embodied and tacit ways of knowing (Pink, Reference Pink2012).

Gardens have a socio-cultural order (Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006) in terms of household relationships and the wider neighbourhood, and their location within shifting social divisions in wider society. Garden practices in the UK have been historically gendered: growing vegetables and maintaining lawns is associated with masculinity; whilst growing plants and herbs is regarded as the ‘decorative’ aspect of gardening, associated with femininity (Taylor, Reference Taylor2008). Allotments especially have been associated with working-class masculinity. Gardening has also been examined within gendered meanings of work and leisure. For instance, for many women the home and garden represent a space of unpaid work and reflect challenges in carving out time and space for leisure (see e.g. Deem, Reference Deem, Wimbush and Talbot1988; Green et al., Reference Green, Hebron and Woodward1990). Gendered meanings of the home and garden have changed over time, reflecting shifting gender relations in wider society (Bhatti and Church, Reference Bhatti and Church2000). Yet, research suggests that gendered divisions of labour remain among heterosexual couples, with men being more likely to do gardening work with machinery and tools, carrying out ‘heavy’ tasks, in ways which support and aspire towards images of hegemonic masculinity (Taylor, Reference Taylor2008).

Research on gardens also highlights changing embodied and relational experiences of domestic gardens over the lifecourse. Gardens have been depicted as a site of play and imagination during childhood, a site of family leisure in adulthood and a hobby during retirement (Milligan and Bingley, Reference Milligan, Bingley, Twigg and Martin2015). In the context of later life, gardens can represent a site of resistance, where older people can continue to express their identity and agency (Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006). However, with the onset of ‘fourth age’ and experiences of illness or impairment in later life, the relationship to gardens can become troubled, and difficulties maintaining gardens can become a reminder of changes associated with the ageing body (Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Gatrell and Bingley2004; Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006). Literature on ageing and gardens reflects a tension between gardens as a site where identity is maintained in later life, and a site where it is diminished or disrupted (Milligan and Bingley, Reference Milligan, Bingley, Twigg and Martin2015).

Dementia and gardens

There is a growing body of research on the benefits of gardens for the wellbeing and quality of life of people living with dementia (Whear et al., Reference Whear, Thompson Coon, Bethel, Abbott, Stein and Garside2014; Barrett and Evans, Reference Barrett and Evans2019; Newton et al., Reference Newton, Keady, Tsekleves and Obe2021). The potential of gardens to support continuity in identity and personhood has been a key theme in this literature (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Keady, Tsekleves and Obe2021). For example, Chalfont and Rodiek (Reference Chalfont and Rodiek2005) describe the possibilities for enacting previous identities in care home gardens, and for connecting to memories and biographies. In their research on community gardens, Noone and Jenkins (Reference Noone and Jenkins2018) emphasise the significance of gardening activities as part of enacting embodied selfhood. Chung et al. (Reference Chung, Ellis-Hill and Coleman2017) explored the role of family carers in supporting the agency and personhood of people living with dementia, including an example of a family carer enabling a person living with dementia to continue gardening. However, Olsson et al. (Reference Olsson, Skovdahl and Engstrom2013) highlight the tension between outdoor activities confirming identity and independence for people living with dementia versus a loss of previous abilities and activities.

Gardens have potential for facilitating social ties and sensory connections to nature for people living with dementia (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Keady, Tsekleves and Obe2021). Research in care home and community gardens demonstrates the sensory enjoyment of outdoor spaces and ‘getting outside’, for instance, the feel of fresh air, the visual appearance and texture of plants, and the sound of birds singing (Chalfont and Rodiek, Reference Chalfont and Rodiek2005; Duggan et al., Reference Duggan, Blackman, Martyr and Van Schaik2008; Barrett and Evans, Reference Barrett and Evans2019). Previous research in care homes describes residents with dementia engaging in ‘social walking’ (McAllister and Silverman, Reference McAllister and Silverman1999) or sitting together in the garden (Hernandez, Reference Hernandez2007), and the use of gardens as a space to meet with visiting friends and relatives (Whear et al., Reference Whear, Thompson Coon, Bethel, Abbott, Stein and Garside2014). Noone and Jenkins (Reference Noone and Jenkins2018) describe the potential of community gardens for facilitating new friendships between people living with dementia, while research on outdoor spaces and neighbourhoods illustrates how gardens can facilitate social connections with the wider neighbourhood (Li et al., Reference Li, Keady and Ward2021).

In care home and sometimes community contexts, positive experiences of gardens are in tension with concerns about risk (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Keady, Tsekleves and Obe2021). Staff concerns about risk sometimes lead to access to gardens being restricted in care homes, even when gardens are designed to be safe and secure (Chalfont, Reference Chalfont2013; Buse et al., Reference Buse, Martin and Nettleton2018). In care homes, the potential benefits of gardens are further constrained by a lack of staff time to support people living with dementia with accessing gardens (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Winsall, Dyer, Breen, Gresham and Crotty2020). In one study of a community garden project, volunteers and care staff supporting people living with dementia similarly expressed concerns about risk, however, there was a greater emphasis on supporting positive risk taking (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Courtney-Pratt and Campbell2018). It is unknown whether these concerns about risk continue to constrain garden use in domestic gardens (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Keady, Tsekleves and Obe2021), or how the social relationships in domestic households shape everyday experiences of using gardens.

The majority of this research has taken place in care home settings or community gardens, and there is very little research on the implications of domestic gardens for people with dementia who are living at home. This lack of research extends to the design literature where the focus has been on care home or health-care settings and sensory design for dementia (e.g. Chalfont and Walker, Reference Chalfont and Walker2013; University of Worcester, 2021). A recent systematic narrative review of the literature on this topic area (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Keady, Tsekleves and Obe2021) identified only six papers from around the world that examined domestic gardens in relation to lived experience of dementia. However, even then, none of the six articles focused exclusively on the domestic garden and all were part of broader studies on outdoor spaces and neighbourhoods (Duggan et al., Reference Duggan, Blackman, Martyr and Van Schaik2008; Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Skovdahl and Engstrom2013; Li et al., Reference Li, Keady and Ward2021), home adaptations (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Cain and Meyer2019) or carer experiences (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Ellis-Hill and Coleman2017; Silverman, Reference Silverman2018). Worryingly, the review also found that further research is needed to foreground the person with dementia's lived experience of domestic gardens as their involvement in study design and reporting was lacking (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Keady, Tsekleves and Obe2021; see also Barrett and Evans, Reference Barrett and Evans2019). There is, therefore, a need for further examination of how people with dementia who are living at home use their gardens, and the location of garden practices within social relationships, temporalities and material arrangements of domestic spaces. The study that we will now share is, to the best of our knowledge, the first in the world to address this overlooked area.

The study

The My Home, My Garden Story project aimed to examine the role of domestic gardens in the everyday lives of people with dementia who are living at home, using creative qualitative methods to capture the multi-sensory and embodied aspects of interactions with place (Ward and Campbell, Reference Ward and Campbell2013). The researcher (Swift) carried out repeat visits and creative interviews with six people living with dementia and members of their household (see Table 1). The research took place in northern England between March and July 2020. The first visit involved a qualitative sit-down interview in participants' homes and a filmed walking interview in their garden. Walking around gardens can act as a springboard for reflections and memories (Hitchings and Jones, Reference Hitchings and Jones2004) and filming the walking interviews helped to capture the embodied and sensory aspects of interactions with gardens (Keady et al., Reference Keady, Hyden, Johnson, Swarbrick, Keady, Hyden, Johnson and Swarbrick2018). During the walking interviews the researcher (Swift) used the materiality of the garden as a prompt for discussion and observed how the person living with dementia interacted with plants, pets and materialities as they walked around the garden. Following the interview, participants were invited to complete a diary of their garden use for a week, using the format that best suited their interests and abilities (including photo-diaries, written diaries and filmed diaries), or a combination of methods. Diaries enable activities to be recorded as they occur, helping to overcome difficulties with memory recall (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett2011), and shedding light on mundane and tacit aspects of everyday life (Pilcher et al., Reference Pilcher, Martin and Williams2016). Following the completion of diaries, the second visit involved a follow-up interview to explore the meanings of diaries with participants.

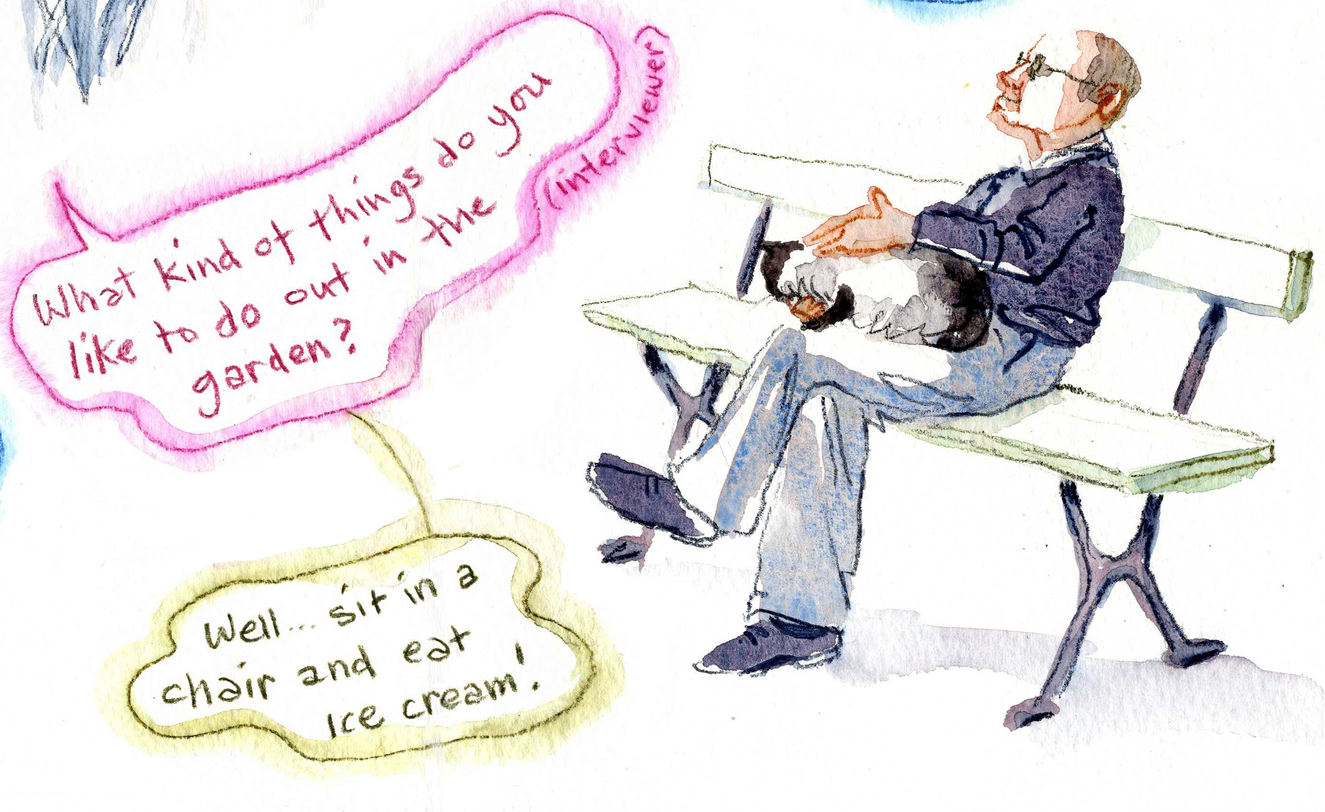

Table 1. Participant information

During fieldwork the methods had to be altered due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so later visits were conducted remotely using Zoom.Footnote 1 This included the sit-down component of initial interviews and follow-up interviews, and the walking interviews, which became filmed garden tours led by the participants, using their own tablet computers. Conducting interviews via Zoom still gave some important insights into people's experiences of their gardens, and the Zoom garden tours enabled the research team (all the authors) to explore the visual and sensory aspects of the gardens remotely. However, there were challenges and limitations, e.g. some participants living with dementia were less comfortable with remote video communications and one household instead opted to take part in their follow-up interview via telephone (see Table 1). It must be noted that all our participants were in couples, whereas reliance on remote video communications may be more challenging for some people living with dementia who are living alone and need support with these technologies, which was an issue in our working group (see below).

In a sense, these remote methods were more participant-led, as participants held the tablet during the Zoom garden tour and guided the filming and discussion. However, it was often the carer who conducted the filming during garden tours, and sometimes the person living with dementia walked away from the camera and their interactions were lost. During in situ walking interviews, it was easier to involve the person living with dementia, using the garden as material prompt, and observing their embodied interactions with gardens. This is particularly important for people who struggle with verbal communication, although embodied interactions were recorded during sit-down interviews through Swift's fieldnotes and were captured on some Zoom garden tours (see e.g. the example below of Lynne and Karen). While in sit-down interviews both participants remained in front of the camera, engagements with the materialities of the home and garden (e.g. discussing the view through the window or participants showing the researcher photographs of their garden) were somewhat diminished in Zoom interviews. The diary component of the research was least affected by COVID-19, as a method that is conducted ‘remotely’ away from the researcher, although participants stated that diaries reflected changes in their activities during the pandemic, with more time spent at home and within the garden.

Some aspects of the methods were more significantly altered due to COVID-19 restrictions. Originally, the study planned to use ethnographic observations of garden practices in addition to the above methods, but this was unable to take place. We planned to record these observations using sketch reportage, working with artist Lynne Chapman. Sketch reportage involves sketching visual and verbal practices in situ, using long ‘concertina sketchbooks’ to record events in sequence as they unfold (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Buse, Pottinger, Baron, Barron, Browne, Ehgartner, Hall, Pottinger and Ritson2021). Sketching can provide a method of ‘concentrated seeing’, enabling places and interactions to be distilled, and capturing atmosphere and meaning beyond what can be seen visually (Heath et al., Reference Heath and Chapman2018). However, this method had to be adapted to Lynne sketching remotely from films of the garden tours. Providing participants with a copy of the sketches gave them a more immediate record of what was said in the interviews, and why it is significant, and enabled the researchers to ‘give something back’ to participants in the short term (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Buse, Pottinger, Baron, Barron, Browne, Ehgartner, Hall, Pottinger and Ritson2021).

Collaboration with people living with dementia

During the study we worked with a local working group of older people living with dementia as our project partner, aiming to embed their involvement into the design and development of the study. Buse (principal investigator) and Swift (researcher) met with the working group during the early stages of the project to discuss our plans for the research. We conducted a further meeting towards the end of fieldwork to share our emerging data and themes and invite their feedback, aiming for this to inform the analysis and writing up of findings, and the design of our future research on this topic. As with data collection, collaboration had to be adapted during the pandemic, and our second meeting was conducted via Zoom. Zoom was the technology used by this working group for their regular meetings and was therefore familiar, although one participant who was living alone required support from the group facilitator (who was in her support bubbleFootnote 2) to set up Zoom. One participant living with dementia dropped out of the second meeting, due to finding group discussions on Zoom difficult to follow. During the project we also worked with a project advisory group of gardeners, designers and landscape architects to inform the design and development of the research and explore implications for design and practice.

Study participants

Six households in the north of England participated in the fieldwork; each included a person living with dementia and their partner or spouse (see Table 1). Participants were recruited with support from the working group and through a voluntary-sector organisation supporting people living with dementia. Participants were sampled purposively, according to whether they met the study inclusion criteria, namely being a person with dementia with capacity who is living at home; uses and can access a garden (including gardens, yards and balconies adjacent to the home); lives in the same household as another person; and has capacity to give consent.

Ethics

Capacity to consent was assessed in discussion with the person with dementia according to the principles of the Mental Capacity Act (2005). As this study was conducted over an extended period of time, consent was viewed as an ongoing process throughout the study (Dewing, Reference Dewing2007), and attention was paid to any verbal or non-verbal signs of dissent, indicating the person no longer wished to participate (Black et al., Reference Black, Rabins, Sugarman and Karlawish2010). To facilitate the consent process, easy-to-read versions of the information sheet and consent form were prepared in accordance with guidance on dementia-friendly information (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project, 2013), and the study was also explained verbally by the researcher visiting the household. Ethical approval was granted by Economics, Law, Management, Politics and Sociology (ELMPS) Research Ethics Committee at the University of York.

Analysis

Data were analysed thematically, and the analysis was informed by a sensitivity to embodied and sensory aspects of interactions with gardens (Pink, Reference Pink2015) and to stories and narratives (Riessman, Reference Riessman2008). While examining themes and patterns in data across households, in keeping with narrative thematic analysis we started with analysis of different forms of data from individual households, and retained sensitivity to biographical narratives and reoccurring stories, and their implications for identity construction (Riessman, Reference Riessman2008). Analysis involved exploring dialogue between different forms of data, viewing video data alongside transcripts, diaries and visual images. Watching video data provides a way to revisit and reconstruct the sensory and embodied experiences of places and interactions (Pink, Reference Pink2015). The research team met regularly online to discuss and analyse data from films, transcripts and photographs. Emergent themes were also discussed with the working group of people living with dementia, and with project advisors including landscape architects and garden designers (see above). Initial thematic categories were then reviewed and organised into larger themes. The more formal coding of data was assisted by NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software, applying themes developed by the research team to coding the data. The themes presented in the paper focus on three ‘ways of being’ in the garden: working in and doing the garden; being in and sensing; and play, empowerment and agency. They also incorporate data from cross-cutting themes around biographies, identity, change and adaptation.

Findings

Theme 1: Working in and ‘doing’ the garden

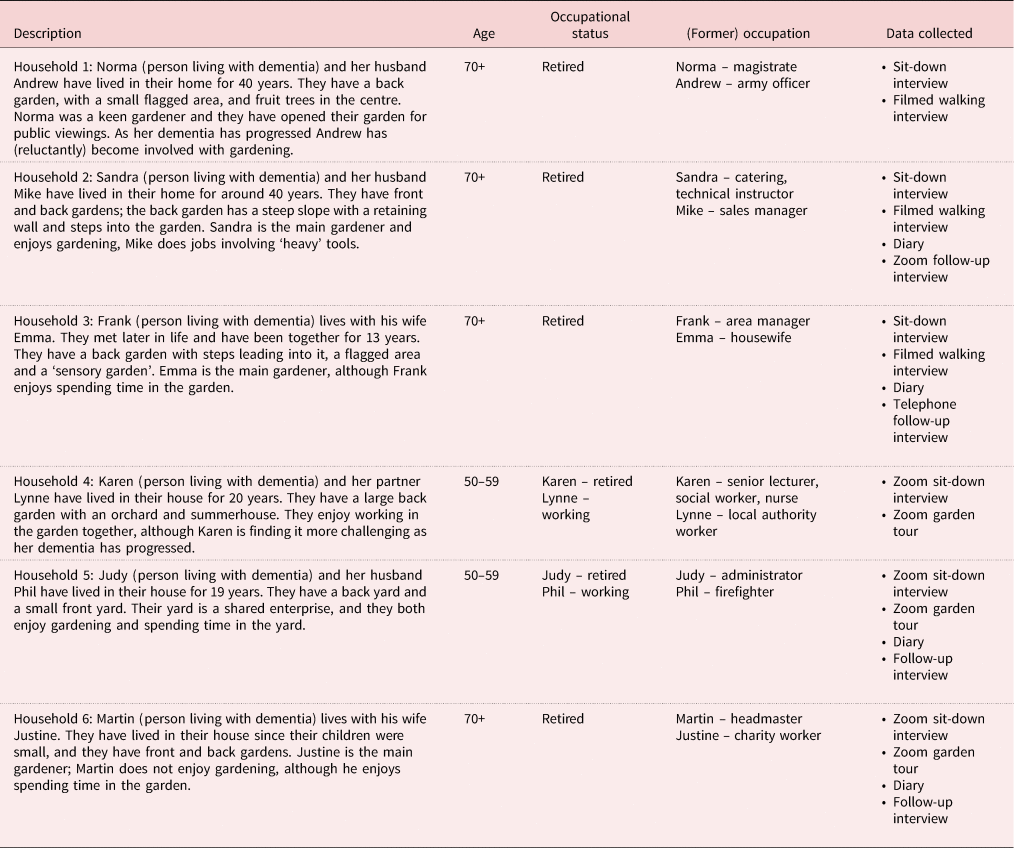

In participants' interviews and diaries, the garden emerged as a space that needs ongoing work and is always in flux. As one participant Emma (family carer, household 3) said, ‘it's still a work in progress – all gardens are really’. Activities such as weeding, raking, tidying, watering, digging and pruning were part of participants' everyday routines, as well as being situated within the cycles of the seasons. During the walking interview, Sandra (person living with dementia, household 2) was continually tidying up the garden and removing dead heads from plants. Her tidying and adjusting of the garden are captured in the sketch in Figure 1, illustrating how as she walked around the garden she was regularly bending down to pull off dead heads or pull out weeds, explaining ‘I'll just take that bit off and put it in the bin’ or ‘wait a minute, get those dead leaves off’. The fluid, sketchy lines reflect Sandra's constant movement during the walking interview. Her walking interview took place in spring and as she walked around she pointed out where the ‘snowdrops [are] growing through the heather’ and the ‘little daffodils’, as well as plants that were still ‘coming through’.

Figure 1. Sandra doing the gardening.

Source: Sketch by Lynne Chapman.

For Sandra, doing the garden is central to enacting her identity, reflecting embodied biographies (Williams, Reference Williams2000), dispositions and skills acquired over a lifetime (Kontos, Reference Kontos2004). Sandra had always been ‘the gardener’ in her household. Mike (family carer, household 2) described how she became ‘more fully involved’ with the gardening because he was often away working, while she was at home with their son, reflecting gendered biographies and divisions of labour (Taylor, Reference Taylor2008). Verbally she distanced herself from any claims to be an expert gardener saying ‘I couldn't say that I'm a perfect gardener’, but she enacted this role through embodied practice.

Sandra and Mike's diary illustrated how she continued to take responsibility for the majority of physical labour in the garden, and the physicality of ‘doing’ the gardening was central to her enjoyment of it, as discussed in the follow-up interview:

Mike: And you could tell [in the diary] that Sandra did most of the work … Sandra never sits down in the garden…

Sandra: Just keeping on top of it … Raking the lawn, that's mostly it. And it's just developing.

Mike: Yeah, she did, with a lawn rake, rake the lawn. That's hard work.

Sandra: No, that's good fun! (Sandra (family carer) and Mike (person living with dementia), household 2)

Here Sandra corrected Mike when he suggested that raking is ‘hard work’, pointing out her enjoyment of it, evidencing the subjective and complex meanings of the garden as a space of work and leisure (Deem, Reference Deem, Wimbush and Talbot1988; Green et al., Reference Green, Hebron and Woodward1990). This reflects gendered and classed habitus (Kontos, Reference Kontos2004) – for working-class women, there is often an emphasis on gardening in terms of ordering and tidying, rather than on cultivating a particular aesthetic (Taylor, Reference Taylor2008). The physical labour of gardening is part of ‘enabling … authority to enjoy and control the space that she creates’ (Raisborough and Bhatti, Reference Raisborough and Bhatti2007: 471), illustrating how people living with dementia can continue to enact agency and identity through embodied practices of gardening (Noone and Jenkins, Reference Noone and Jenkins2018) which are pleasurable.

Yet while gardening is situated within biographical continuity at an embodied level, it also reflects changes associated with dementia and within life more broadly, requiring ongoing adjustments to practices, identities and material arrangements. Mike talked about how he and Sandra spend more time in the garden together now and ‘it's very rare one of us works in the garden [without] the other’. This partly reflects the fact that he is now retired, but also their shared concerns about one of them falling on the steps if they are working out there alone. Spending more time in the garden together emerged as a theme across other couples, providing a way to support enabled risk (Rendell and Carroll, Reference Rendell and Carroll2015; Noone, Reference Noone2018).

For other participants, working in the garden was situated within processes of renegotiating and reconstructing identities and relationships in the context of living with dementia (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2002), rather than as part of biographical continuity (Williams, Reference Williams2000). Martin (person living with dementia, household 6) had never been interested in gardening and referred to Justine (family carer, household 6) as the ‘expert’ gardener, saying ‘certainly Justine is the one that knows about the gardening’. Martin states he has ‘never chosen’ to do the gardening, reflecting household divisions of expertise where Justine is ‘so keen on it, and I can't keep up with that’. However, he observed that ‘obviously that's got even worse as the dementia's crept in’ and he described himself ‘walking behind’ Justine when assisting in the garden so that he did not ‘do things wrong’. Spending time with Justine in the garden had become more frequent since the onset of his dementia, and retiring from his job as a headmaster:

It must be a part of dementia, is that once you realise you've got it … you can't control it, but you know when to actually stand back and when you can be involved. And that's been a terrific learning curve for me over the last couple of years … And I find it quite hard to be in company now … because of what I was, in terms of headteacher, and we had a very vibrant school, great reputation … And that's all gone. I couldn't, I couldn't actually risk any of those sort of things now … I'll stand behind Justine [in the garden], poor old Justine has to get all the wrongs put right, don't you! (Martin (person living with dementia), household 6)

‘Walking behind’, ‘standing back’ or ‘following behind’ are very powerful metaphors in Martin's description of how dementia creates challenges for contributing to everyday tasks such as gardening, and getting things ‘right’. As Martin said, ‘poor old Justine has to get all the wrongs put right’. There is a sense of sadness in terms of the loss of Martin's work identity, and the status associated with this, felt especially in contrast to challenges he now experiences with everyday practices. Martin explained how he needs clear instruction from Justine when helping with tasks in the garden ‘because I can just lose it in the moment’ and ‘I'm finding short term I can easily forget things'.

However, Martin's discussions of the garden also suggest readjustment to new ways of being together in the garden and carving out new identities. Identities are constructed through habitual daily activities and when these activities are disrupted due to illness, this necessitates their reconstruction (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2002). The couple now spend more time in the garden together and Martin reflected that ‘I'm quite happy to go out if Justine will give me a chore, something to do out there’, suggesting that being in the garden with Justine in this way might be giving him a new sense of purpose and ‘replacement work’ (Milligan and Bingley, Reference Milligan, Bingley, Twigg and Martin2015: 327). He described ‘walking behind’ as a deliberate adjustment of his practice to support Justine, because ‘I'm aware that if I do things wrong it's going to make it twice as hard for Justine’. At the same time, he referred to himself more actively as the ‘digger man’, constructing a new identity through physical labour, perhaps associated with hegemonic masculinity, such as digging, clearing out the shed or mowing the lawn (Taylor, Reference Taylor2008). Their diary depicts an occasion when Martin became absorbed in the task of mowing the lawn:

After lunch I had some things to do indoors and Martin wanted to cut the grass. It was good to have some space from each other and he managed fine. It began to rain briefly just as he finished. He did come in eventually! (Extract from Martin (person living with dementia) and Justine's (family carer) diary, household 6, Sunday 26 April 2020)

This extract illustrates Martin's determination to finish mowing the lawn, and the garden as a site for enabling space and time apart, as well as new ways of being together.

During the follow-up interview, Martin read a poem he had written – this excerpt captures something of the complexity of his experience of working in the garden, in a creative, evocative fashion:

Our garden … Days, weeks, months, years, how time passes, tears for fears.

Our garden … needs to be done, don't agonise, it might be fun.

Procrastination rules my head, I've other things to do instead, with planning out perfect plots, of rearranging plants and pots, to where I think they need to grow, to make our plot a flower show.

Yet need to be done, the challenge set, soil is stable, not too wet, spade and fork then hoe hoe hoe, it's off to work I go go go.

…Oh dear, a vicious circle looms, time to gather pots and brooms, store those forks, hang high the spade, reflect the tiny change you've made.

This poem captures the garden as a space that is always ‘becoming’ (Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006), describing how ‘days, weeks, months’ pass in the garden, yet a considerable amount of work only manifests in ‘tiny change’. It illustrates Martin's ambivalence about working in the garden – his statement the garden ‘needs to be done’ suggests a reluctance to work in the garden, which is then softened by the statement ‘it might be fun’. The poem also moves between Martin's first-person voice and the perspective of the couple, mixing his internal monologue with a voice from his relationship. This reflects the relational experience of working in the garden together, and the reconfiguration of the couples' relationship and roles in the garden. The invocation of ‘perfection’ and ‘flower show’ in Martin's poem points to a tension between working in the garden as an end in itself, and the domestic garden as a semi-public space, subject to external judgements by visitors and neighbours. This creates additional pressures around ‘getting it right’ when doing the garden.

Theme 2: ‘Being in’ and ‘sensing’

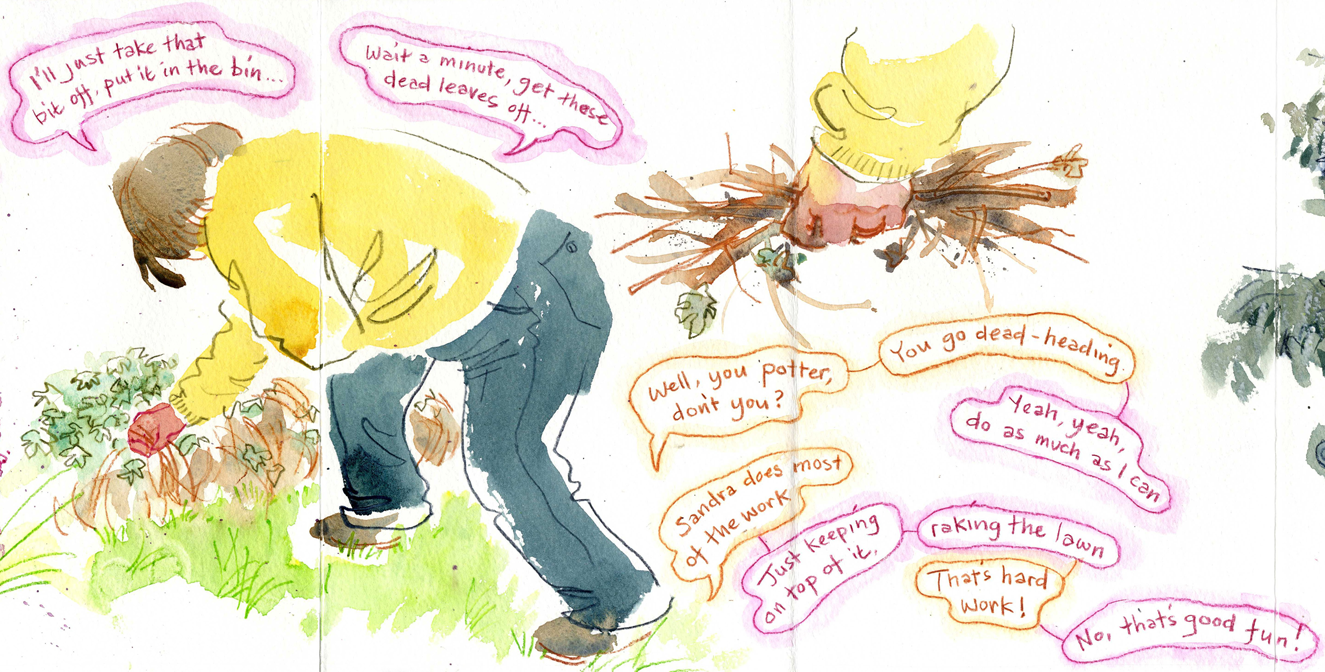

For some participants, enjoying the garden was not about the physicality of ‘doing’ the gardening, but the sensory experience of ‘being in’ the garden. In some literature on gardens and dementia or ageing there is a tendency to distinguish between ‘active’ and ‘passive’ garden practices (e.g. Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006; Newton et al., Reference Newton, Keady, Tsekleves and Obe2021). However, the walking interviews revealed how sitting in the garden can involve an active engagement with the sensory experience of the garden and ‘being in the moment’. This is captured by a sketch of Frank (person living with dementia, household 3) during the walking interview, in a moment where he sat on the bench enjoying the feel of the warm sunshine and the sensory experience of stroking one of their ragdoll cats (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Frank enjoying the sensory experience of the garden.

Source: Sketch by Lynne Chapman.

Far from being ‘passive’, the sketch illustrates how Frank actively initiates a moment of sensory and embodied engagement with his surroundings, and a moment of connection with his cat. As suggested by the image (Figure 2), ‘being in’ the garden also involves ‘being alongside’ (Latimer, Reference Latimer2013) at a multi-sensory level – spending time with partners, friends and family, and also with plants, pets and wildlife, whilst engaging in other activities like eating (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2017).

For Frank, a focus on ‘being in’ the garden reflected his biography – he has never enjoyed doing the gardening, but he enjoys sitting outside in the garden, particularly with an ice cream or coffee. Similarly, while Martin (person living with dementia, household 6) was not confident about ‘making a garden look like a garden’, he stated: ‘I love being in the garden, love being outside.’ However, for other participants there was an increased emphasis on ‘being’ rather than ‘doing’ the garden in response to changes associated with dementia and the ageing body. Lynne (family carer, household 4) and Karen (person living dementia, household 4) reflected that they worked in the garden and ‘did absolutely everything’ together but that ‘it's a little trickier now’ as Karen's dementia had progressed. Lynne described how ‘Karen's derived a lot of peace and relaxation’ from the sensory experience of ‘being in’ the garden:

And she [Karen] loves being outside in the garden, and it's that open space, the sound of the birds. We have lots of nesting birds, as well as chickens, and we have two dogs … we both find, in separate ways, a lot of comfort and space out there. (Lynne (family carer), household 4)

This quote captures how the sensory enjoyment of being in the garden involves listening to the birds, and ‘being alongside’ their chickens and two dogs. As Lynne noted, being in the garden was important to them both, creating time together and apart. Karen struggled with verbal communication, however, during the Zoom garden tour we observed her walking over and sitting in ‘her chair’ in the sunshine, stroking their dog, demonstrating her enjoyment of ‘being in’ and ‘being alongside’.

As well as sitting in the garden, ‘sensing’ and ‘being in’ can involve walking around the garden. Pink (Reference Pink2012: 95) has described how gardeners articulate their ‘way of being with plants’ by walking through the garden, touching plants and talking about them. Although Sandra (person living with dementia, household 2) ‘never sits’ in the garden, walking through the garden is part of her everyday practice of inhabiting the space. During the walking interview, Sandra pointed to and touched various plants and trees that she had grown, demonstrating her expertise, for instance: ‘that's viburnum, isn't it. That pink one’. As she was walking around, seeing and hearing birds in the garden also prompted memories:

I love the birds. Because I used to have a grandad that was very good. He used to drive horse and carriages in London. And he was lovely … he kept chickens! (Sandra (person living with dementia), household 2)

Other participants talked about ‘pottering’ as a way of ‘being in’ the garden. For instance, while Norma (person living with dementia, household 1) struggled to keep up with maintaining her garden as a space of display, ‘pottering’ was central to her ongoing enjoyment of the garden. The walking practices of people living with dementia are often pathologised as ‘wandering’ and viewed as risky (Wigg, Reference Wigg2010). In our study, participants made material adjustments to their gardens to enable safe ‘pottering’ or walking. For instance, Andrew (family carer, household 1) had put ‘green eye guards’ on top of posts in the garden, in case Norma fell and caught herself on them – an idea suggested by their niece's husband. During the walking interview, Emma (family carer, household 3) was continually assessing and adjusting the garden to manage potential risks, for instance, moving a pot that Frank (person living with dementia, household 3) might fall over and considering where they might put in a handrail by the steps, in anticipation of future risks of falling.

The garden became part of not only ‘being in the moment’ for people living with dementia and their families, but of curating a series of meaningful moments (Keady et al., Reference Keady, Campbell, Clark, Dowlen, Elvish, Jones, Kindell, Swarbrick and Williams2022) throughout the day. Keady et al. (Reference Keady, Campbell, Clark, Dowlen, Elvish, Jones, Kindell, Swarbrick and Williams2022: 687) describe ‘being in the moment’ as: ‘the multi-sensory processes involved in a personal or relational interaction and embodied engagement’. Sometimes these moments emerged spontaneously, but the material arrangements of the garden – the positioning of seating, food and drink, proximity to pets or loved ones – could also be deliberately organised to support enjoyable moments. Frank follows the sun around the garden during the day and sits on different seats to catch the sun at different times, as his wife Emma describes:

We've got seating for different times of the day. Sometimes you want the blue seat at the end, just right for an early morning cup of coffee, because that's the first place to catch the sun. And in the end of the day the bench here catches the sun, so that's a nice place to sit later in the day. (Emma (family carer), household 3)

Emma described deliberately curating these moments ‘I'm much more aware of making it a pleasant place to draw Frank out … to sit in the garden … have his cup of tea out here instead of indoors.’ She tried to create a space that was inviting at a sensory level, planting flowers with vivid colours and fragrances, and brightly coloured garden furniture. This reflects an extension of practices of home-making in the context of dementia (Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006: 321), and an ongoing process of tinkering to facilitate Frank's engagement with the garden.

The carefully curated materiality of the garden could be disrupted by the changing weather and seasons. The significance of the weather in shaping moments of ‘being in’ the garden was prominent in participants' diaries:

Sunday 19 April 2020

Lovely sunny day today so we both sat outside in the back garden listening to the neighbours pottering about in their garden. It got a little windy so we came in about 12.15 to make some lunch.

In the afternoon we sat out in the garden for a cup of tea, but again it was a bit too windy so we didn't stay out for long. (Extract from Judy (person living with dementia) and Phil's (family carer) diary, household 5)

This extract illustrates the sensory experience of ‘being in’ the garden, enjoying the sunshine, listening to the neighbours pottering about next door. Keady et al. (Reference Keady, Campbell, Clark, Dowlen, Elvish, Jones, Kindell, Swarbrick and Williams2022) describe how ‘moments’ may be ended by the person living with dementia, or by others involved in the interaction – in this case the moment was ended by the windy weather. On rainy days participants reported that they did not go out much, or limited garden activities to essential tasks and the garden became more of a ‘chore’. Enjoyment of ‘being in’ the garden also declined during the winter, as Emma (family carer, household 3) said she would just go out for a ‘quick tidy up now and again’. Judy (person living with dementia, household 5) and Phil (family carer, household 5) do not use their yard much in the winter, because ‘it's only a small space, it just becomes more utility really in the winter’. However, for some participants, in bad weather the sensory experience of ‘being in’ the garden could be recreated from a window or conservatory, as Emma said, ‘the big window overlooks the garden … even in the winter … you can see the sky and the birds, things growing’. For Karen (person living with dementia, household 4) and Lynne (family carer, household 4), their summerhouse provided a space to enjoy the garden all year around. However, the ability to enjoy the garden in all weathers can be constrained by the garden design and amount of available space.

Theme 3: Playing, enjoyment and agency

For some people living with dementia, playing was central to their experience of the garden, and provided opportunities to reassert a sense of everyday creativity and agency (Bellass et al., Reference Bellass, Balmer, May, Keady, Buse, Capstick, Burke, Bartlett and Hodgson2018). Kontos et al. (Reference Kontos, Miller, Mitchell and Stirling-Twist2017b: 58) highlight the significance of play as part of ‘relational presence’, encapsulating the abilities of people living with dementia to ‘initiate, modify and co-construct exquisite moments of engagement … through affective relationality, reciprocal playfulness and co-constructed imagination’. While Martin's (person living with dementia, household 6) experience of gardening (as discussed above) reflected a loss of work identity, and a lack of confidence, through playing table tennis games in the garden Martin was able to exercise a sense of competency, enjoyment and humour. Martin co-wrote his diary with Justine (family carer, household 6) and they included jokes about him repeatedly winning table tennis games and her trying to catch up with and beat him:

Friday 24 April 2020

Having completed and cleared our meal we considered a game of table tennis on our front drive. This has become quite a regular activity during these lockdown days and there is absolutely no doubt that I am keen to demonstrate my ‘ping-ponging’ is, in the not too distant future, going to overcome Martin's casual expectation to win every time! In fact, in spite of disconcerting breezy conditions I won two out of four games, which is my best result so far!

Tuesday 28 April 2020

We played table tennis after lunch. Justine won two games (Her words – it doesn't happen very often!) (Extract from Martin (person living with dementia) and Justine's (family carer) diary, household 6)

Through playing table tennis, Martin is able to reassert a sense of agency. Their discussions of table tennis also demonstrate a reciprocal playfulness between the couple (Kontos et al., Reference Kontos, Miller, Mitchell and Stirling-Twist2017b).

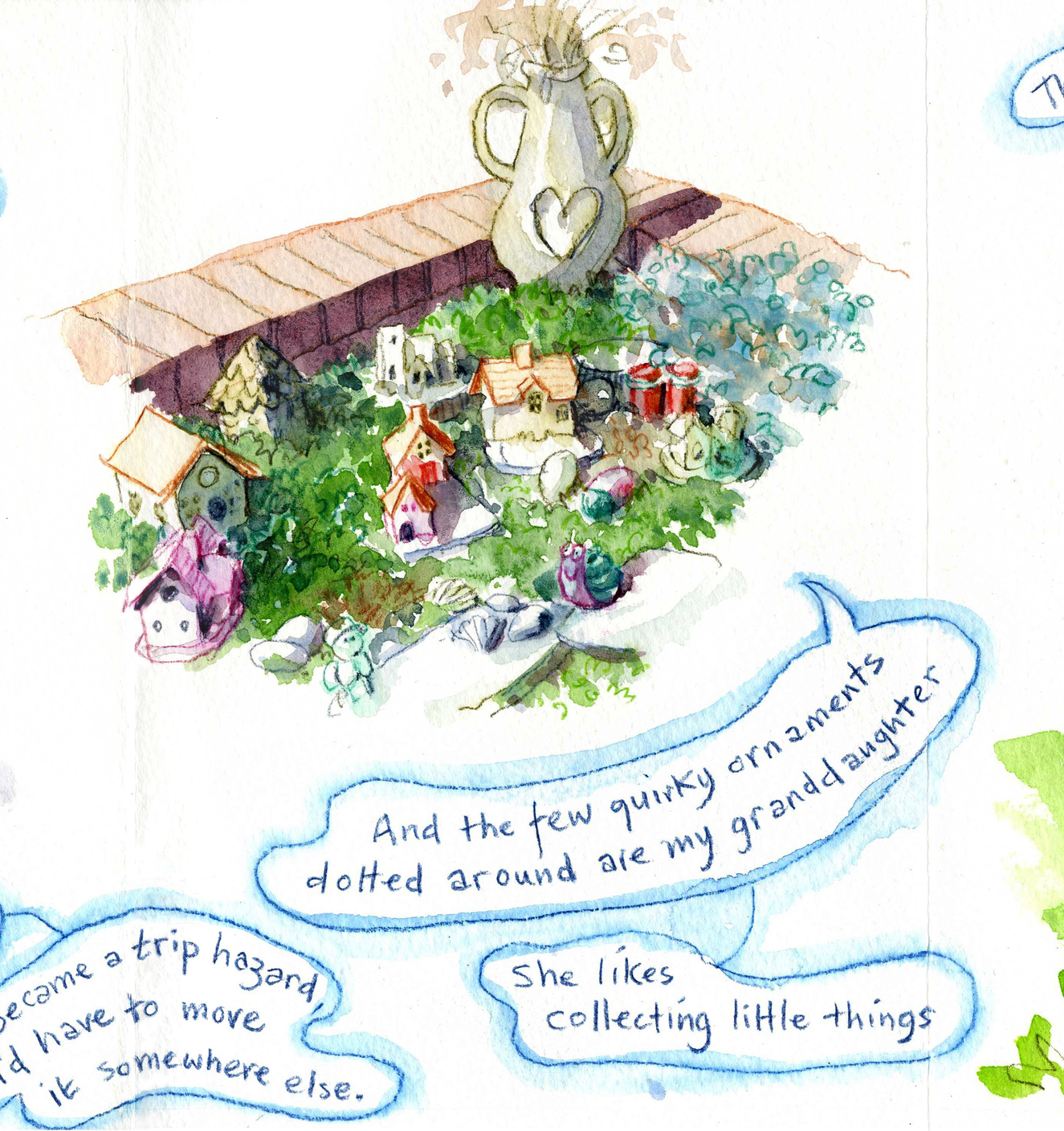

Playing in the garden provided an opportunity for relational presence with other family members. Emma (family carer, household 3) talked about her and Frank (person living with dementia, household 3) enjoying spending time playing outside with their granddaughter, whom they look after on a regular basis. She described how ‘when our granddaughter's around we play out there. He [Frank] plays a game of bowls with her sometimes’. Although Emma acknowledges that Frank's contribution to gardening is limited, she emphasises his central role in helping to look after their granddaughter through playing together. As illustrated by the sketch in Figure 3, their granddaughter had created a magical fairy garden, with ‘quirky ornaments’, illustrating ‘co-constructed’ imagination (Kontos et al., Reference Kontos, Miller, Mitchell and Stirling-Twist2017b). This reflects ongoing relationships of care, in which Frank and Emma have supported their daughter and assisted with child care:

Frank: …we care for our granddaughter. Well, Emma cares for our granddaughter quite a lot. Because her mum's got some problems.

Emma: Yeah, so it's got to be a child-friendly garden, as well as a dementia-friendly garden, hasn't it. (Frank (person living with dementia) and Emma (family carer), household 3)

Figure 3. Fairy garden created by Frank and Emma's granddaughter.

Source: Sketch by Lynne Chapman.

This discussion of Frank and Emma providing support for their granddaughter challenges the portrayal of people living with dementia as passive recipients of care (Kontos et al., Reference Kontos, Miller and Kontos2017a). Elsewhere in the interview, the couple discuss receiving support from their daughter, for instance, in choosing the ragdoll cats as the right breed for sitting in the garden, suggesting a relationship of mutual support. The discussion illustrates how the garden is co-constructed between the needs of family members, adapted to be ‘dementia-friendly’ but also ‘child-friendly’. These adaptations include replacing a rose over the archway into the garden with a thornless rose, as Emma views thorns as a potential ‘hazard’ to her, her husband and their granddaughter.

One of Frank's main hobbies was playing table tennis – at the time of the first interview he went to a dementia support group to play table tennis, and they did not have a table tennis set in the garden. However, they reflected during the interview that this might be ‘an idea’ and Emma stated: ‘it's keeping an open mind of how you can adapt and change your space and make it more usable’. This reflects how garden practices and spaces require ongoing tinkering to facilitate play, as the interests and practices of people living with dementia change over time. By the time they were recording their diary, Emma had ordered a trestle table for playing table tennis in the garden:

Tuesday 7 April 2020

Today has been a bit chillier, so just a bit of brisk weeding and sweeping to tidy up. I'm concerned that Frank isn't getting much exercise at the moment so I was pleased that a plastic trestle table that I ordered weeks ago was delivered today. I plan to set it up in the garden for table tennis. With that and boules he will hopefully get moving a bit more.

Update – June 2020

We've certainly been using the garden far more than usual what with the lockdown and the beautiful weather. Frank is still not getting as much exercise as I would like. The boules and table tennis get an occasional airing but he is outdoors more than ever before … Weather permitting I'm positive Frank will spend more time in the garden, and maybe get a bit of exercise. (Extract from Frank (person living with dementia) and Emma's (family carer) diary, household 3)

The inclusion of a table for table tennis demonstrates ongoing adjustments to make the garden more enjoyable and more useable for Frank, and to reflect his hobbies and interests. But it also suggests a sense of pressure to keep Frank active, reflecting how play is situated within wider discourses around active ageing, and perhaps an attempt to portray an active interest in and use of the garden in the diary (Pilcher et al., Reference Pilcher, Martin and Williams2016). This is situated within the changing seasons, and an attempt to encourage outdoor activity in the spring and summer months.

Like Martin, humour was prominent throughout Frank's interview, illustrating how the garden provided opportunities for jokes and playfulness:

Interviewer: So what kind of things do you like to do out in the garden?

Frank: Well, sit in a chair eating an ice cream is basically my…! Sorry, I'm sorry! I've got this terrible sense of humour! (laughs).

Emma: It gets you your vitamin D in the sunshine, doesn't it?

Frank: Oh very much so.

Emma: Just sitting in the sun having a cup of tea, it's still good for you.

Frank: Oh yes. Watch the old hairyplane going over! Looking at the precocious catophractes. I'm acknowledged as a world expert on that by the way.

Interviewer: Oh, really!

Frank: Oh, haven't lost my … my sense of humour. (Frank (person living with dementia) and Emma (family carer), household 3)

In this extract Frank demonstrates playfulness, spontaneity and creativity, and also the centrality of humour to enacting his identity. Humour as form of play is an area where Frank is able to exercise agency and competency, supported by Emma's adjustments to the materiality of the garden and everyday garden practices, as part of ongoing practices of home-making in the context of dementia (Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006).

There were, however, constraints on the use of the garden for play. In their diary and interview, Justine (family carer, household 6) and Martin (family carer, household 6) were unable to play table tennis on occasions when the weather was windy or wet. For other participants, the size of the garden constrained possibilities, as Judy (person living with dementia, household 5) and Phil (family carer, household 5) discussed in relation to their yard: ‘When the weather's not good … there's not much you can do out here.’ Possibilities for play were also negotiated between household members. Although Emma (family carer, household 3) was continually tinkering with the garden to make it enjoyable and useable for Frank (person living with dementia, household 3), she was less enthusiastic about Frank's proposition for a model railway in the garden:

Frank: Well it should be an old man/model railway-friendly [garden] as well!

Emma: Maybe it should, but it's not likely to happen! (laughs).

Interviewer: …so those are the adaptations that you'd like to make to the garden, to put the model railway in?

Frank: I mean if there's grants in the offing! (laughs). Very much, not sure it'd get past the wife though! (Frank (person living with dementia) and Emma (family carer), household 3)

Play can therefore be a site of negotiation and disagreement, as well as supporting togetherness. However, this discussion again illustrates reciprocal playfulness and humour, and Frank's ongoing ability to imagine what his ideal garden might look like in the future.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper has drawn attention to different ways in which people living with dementia use and experience domestic gardens, focusing on three ‘ways of being’ in the garden: working in and doing; being in and sensing; and playing. The theme ‘doing the garden’ illustrates how people living with dementia and the people they live with might remain actively engaged in gardening as a practice. Doing the garden can be part of enacting embodied selfhood, situated within gendered and classed biographies of domestic space (Taylor, Reference Taylor2008). However, it also reflects change, and the renegotiation of everyday practices and household relationships. There are indications too that the semi-public nature of outdoor spaces leads to some tensions in how people navigate their changing capacities in gardening, as they do the garden for themselves with their own values and needs, but also for the view of others and thus with a public aesthetic of what a garden should look like or be.

In contrast to ‘doing’ the garden, ‘sensing’ and ‘being in’ allows continued enjoyment of the garden without concerns about the end result. The significance of the sensory experience of the garden emerges in previous literature in care contexts (Chalfont and Rodiek, Reference Chalfont and Rodiek2005; Duggan et al., Reference Duggan, Blackman, Martyr and Van Schaik2008; Barrett and Evans, Reference Barrett and Evans2019). Our findings illustrate how these sensory experiences relate to the material and relational dynamics of domestic gardens – listening to the neighbours pottering next door, having a cup of tea with other household members, stroking a pet or catching the sun on a favourite bench. Far from being passive, ‘sensing’ was an active way of connecting and ‘being alongside’ (Latimer, Reference Latimer2013). This has implications for literature on relational citizenship and relational presence, contributing to calls for widening notions of relationships in the context of dementia to include non-human actors (Latimer, Reference Latimer2013; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2017). Experiences of ‘being in’ the garden were shaped by – and shaped – relationships with partners, family, neighbours, pets, wildlife, plants and material objects. Findings illustrate the agency of non-human actors in shaping encounters, for instance the presence of pets or the role of the weather in beginning or ending ‘moments’.

In previous literature, the garden as a space of play and imagination has been associated with childhood (Milligan and Bingley, Reference Milligan, Bingley, Twigg and Martin2015), and has not been explored in connection to later life or dementia. Play is a developing area of research in dementia studies, however, previous scholarship has focused on arts and drama therapies, often in care settings (e.g. Knocker, Reference Knocker2001; Kontos et al., Reference Kontos, Miller, Mitchell and Stirling-Twist2017b; Swinnen and de Medeiros, Reference Swinnen and de Medeiros2018). Our findings illustrate the significance of exploring play in everyday life with dementia, and attending to different spatial and relational contexts in which play, as an aspect of ‘everyday creativity’ (Bellass et al., Reference Bellass, Balmer, May, Keady, Buse, Capstick, Burke, Bartlett and Hodgson2018), occurs and is negotiated. While play has previously been under-researched in the context of dementia and later life due to concerns about infantilisation (Swinnen and de Medeiros, Reference Swinnen and de Medeiros2018), our research suggests that play can provide opportunities for exercising agency in the context of the garden, and for reconstructing new identities and practices. More research is needed to understand the tensions in play in this context, to better connect it to questions of power and agency, as well as to change and embodiment.

These ‘ways of being’ in the garden are also ways of ‘being in place’ (Li et al., Reference Li, Keady and Ward2021) and ‘being at home’. Through ‘doing’, ‘sensing’ and ‘playing’ in the garden, participants are actively engaged in embodied practices of home-making, involving spatial, temporal and social ordering (Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006). The garden was a significant part of household routines, including the ongoing process of ‘doing’ the garden, and daily routines of ‘being’ in the garden, which are entangled with rituals of tea and coffee drinking, as well as the rhythms of the weather and seasons. Practices of engaging with the garden contribute to the ‘entextured’ and sensory experience of feeling ‘at home’ (Angus et al., Reference Angus, Kontos, Dyck, McKeever and Poland2005: 169). Domestic gardens are always in a state of flux (Bhatti, Reference Bhatti2006), and the embodied changes associated with dementia can disrupt a sense of being at home through tacit routines, and the enactment and display of identities. However, by adapting garden practices and the physical space of the garden, participants found new ways of being and feeling at home. The garden also provided a space for reconstructing and adjusting social relationships in the context of dementia, enabling couples to create time and space together and apart in new ways.

This research has implications for policy and for design. There is a growing policy emphasis in the UK on ‘living well’ at home with dementia (Department of Health, 2009, 2016). However, definitions of ‘home’ are not generally extended to encompass domestic gardens. While there is a growing recognition of the need to adapt homes to support people living with illness or disability, including dementia, the emphasis is generally on adapting the inside of the home (Department of Health and Social Care, 2021). Our findings illustrate the importance of domestic gardens for ‘living well’ at home. Findings also illustrate the significance of embedding flexibility in garden design, recognising that gardens are constantly evolving in relation to the changing needs and practices of people living with dementia. Our research supports arguments for locating design for dementia within ‘design interactions’ involving people, contexts, materials and things (Tsekleves and Keady, Reference Tsekleves and Keady2021), and for ‘relationship-centred design’ (Rendell and Carroll, Reference Rendell and Carroll2015). Domestic gardens are shaped by a range of relationships, and were adjusted to be ‘child-friendly’, ‘age-friendly’ and ‘pet/wildlife-friendly’ as well as dementia-friendly. More research is need here again, to explore the ways in which these different ethical and practical commitments are negotiated, how they combine and support each other, or sit uncomfortably or in contradiction, as people with dementia and their families work to adjust their everyday practices.

Findings also have implications for care practice. In care practice, as well as design for dementia, there is often a focus on mitigating risk, particularly in relation to ‘wandering’ (Wigg, Reference Wigg2010), which can lead to restrictions on garden access (Chalfont, Reference Chalfont2013). In our research, rather than prohibiting risk, participants enabled safe walking, ‘pottering’ and playing through ongoing ‘tinkering’ with the material arrangements of the garden. Further research is needed to explore if this ‘safely imaginative’ (Rendell and Carroll, Reference Rendell and Carroll2015: 18) approach is characteristic of domestic households, and if this may change as dementia progresses, or as paid care workers are employed in the home. Recognising the diversity of garden practices is also important for care practice, highlighting the importance of avoiding limiting garden use to prescribed activities, and making room for everyday creativity in the different ways people living with dementia engage with gardens (Bellass et al., Reference Bellass, Balmer, May, Keady, Buse, Capstick, Burke, Bartlett and Hodgson2018).

There are some limitations to the study. Further research is needed to explore these nascent findings using a larger sample incorporating a greater diversity of household and garden types, thereby addressing intersecting divisions around class, gender, race and type of dementia. The study only included people living with dementia who had capacity to consent, however, as dementia progresses this may further alter experiences of using gardens. Conducting the research during the time of COVID-19 resulted in adaptations to methods. As discussed above, the Zoom interviews and garden tours enabled the multi-sensory experience of gardens to be communicated at a distance, and maintained the involvement of people living with dementia as part of the household.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to our project partner, to all the participants, our project advisors and to Lynne Chapman for her beautiful sketches (www.lynnechapman.net).

Financial support

This work was supported by the University of York Pump Priming Fund (January to July 2020): ‘My home, my garden story: exploring how people living with dementia access and use their garden in everyday life’.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was granted by the University of York Economics, Law, Management, Politics and Sociology (ELMPS) Ethics Committee.