1 Introduction

The exact origins of the aphorism ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ are difficult to trace. It is sometimes attributed to advertising executive Frederick R. Barnard, who used a similar phrase, ‘One Look Is Worth A Thousand Words’, in the trade journal Printers’ Ink in 1921. However, in 1918 an advert for a pictorial magazine called San Antonio Light contained the phrase ‘One Picture is Worth A Thousand Words’, and a similar phrase appears in a 1913 advert for the Piqua Auto Supply House, in Ohio. Even further back, an article in 1911 in the Post-Standard about a banquet held by the Syracuse Advertising Men’s Club quotes the newspaper editor Arthur Brisbane as saying ‘Use a picture. It’s worth a thousand words.’ We could go further back in time to hear the same sentiment expressed by Leonardo da Vinci, who said that a poet would be overcome by sleep and hunger before being able to describe with words what a painter could do in an instant. Even Confucius (c. 551–c. 479 BCE) has been credited with the phrase, having said 百闻不如一见 (‘hearing something a hundred times isn’t better than seeing it once’).

No matter who came up with the idea or turned it into an aphorism, its meaning is clear – a message can be conveyed much more effectively in an image than in a verbal description. As Kress and van Leeuwen (Reference Kress and van Leeuwen2020: 16) put it, ‘we see images of whatever kind as entirely within the realm of the realisations and institutions of ideology, as means – always – for the articulation of ideological positions’. Images in news discourse are particularly powerful. Rafiee et al. (Reference Rafiee, Spooren and Sanders2021) write that such images ‘call attention and raise awareness with an immediacy that text cannot easily achieve’ as well as increasing the ‘mass audience’s emotional reaction toward social events’ (1). The claim brings to mind an experiment by McClure et al. (Reference McClure, Puhl and Heuer2011), who found that image selection accompanying a relatively neutral news story had an impact on audience attitudes.

Images have tended to be disregarded in corpus linguistics research. Although a range of different frameworks exists for interpreting meaning in images (e.g. Kress and Van Leeuwen 1996, Peez Reference Peez, Marotzki and Niesyto2006, Mey and Dietrich Reference Mey and Dietrich2017), there is no agreed-upon standard, and the application of a framework would need to be carried out by the analyst, image by image; the equivalent of grammatically tagging a corpus by hand. Even if this was achieved, there are few tools which allow researchers to conduct an analysis of a large set of images or a combined set of images and written text.

However, this situation is changing due to advances in artificial intelligence (AI) which have enabled automatic taggers to work with images, assigning labels to them which describe their content. For example, Google Cloud’s Vertex AI uses machine learning to identify images from models pre-trained on huge datasets of images. The Open Images Dataset v7, from 2022, contains nine million annotated images which span 20,638 label classes.Footnote 1 In Baker and Collins (Reference Baker and Collins2023), a pilot study was carried out using Google Cloud Vision, a Vertex AI predecessor, with a small corpus (approximately 100,000 words) consisting of one month’s worth of British national newspaper articles referring to obesity. Google Cloud Vision automatically tagged the 358 images in the articles with labels like Rectangle, Shoulder, Sitting and Event, resulting in around 29 tags per image on average. The tags were integrated into corpus files which contained the written text, and the pilot study analysed the resulting corpus with WordSmith Tools (Scott Reference Scott2024), identifying both the keywords (i.e. words that are significantly more frequent in one set of texts when compared against another set) and the key image tags associated with each newspaper. A multimodal analysis was also carried out on the most frequent image tags. For example, the tag Event was found to co-occur in articles that also contained a lot of first-person pronouns. Qualitative analysis of these articles found that they tended to involve stories containing first-person narratives about people who had struggled with their weight and that such sympathetic representations were enhanced by photographs of them wearing smart clothes at public events.

Baker and Collins’ (Reference Baker and Collins2023) study indicated that it was feasible to build and analyse a multimodal corpus, although its small size meant that it was difficult to obtain many meaningful results. Also, as the corpus texts were collected manually, the process used was not one which could be recommended for building larger corpora. It was also difficult to locate and view multiple images (e.g. all images tagged as Event) or images which co-occurred with particular text (e.g. all images occurring near text containing a first-person pronoun). Identifying such images also had to be carried out manually and was a time-consuming process. Furthermore, during the analysis, numerous tagging errors were logged, raising questions about whether the image tagger was actually worth using. Additionally, we should bear in mind that the set of tags for each image only gave a partial account of its meaning. The tagger was not perfect and tended to prioritise the tags it was most confident about. Even then, it was sometimes incorrect. Finally, some tags that might be useful for analysis (such as information about a person’s sex) simply weren’t part of the system. This meant the tagging system could not produce a set of tags which would tell us the overall message of each image. Instead, through analysis of repeated tags, the authors identified how particular aspects of an image can appear repeatedly in articles which have certain uses of language.

The aim of this Element is therefore to carry out a more comprehensive study, addressing the issues that were raised in the pilot study. Specifically, we wanted to (a) automate the process of building a multimodal news corpus; (b) identify the level of tagging accuracy of the images and find ways to improve accuracy if required; (c) develop a tool which would allow images to be surveyed if they appeared with certain tags or in newspapers that contained certain words; and (d) carry out a multimodal analysis on representations in a much larger news corpus in order to ascertain whether the visual and multimodal aspects of the analysis were able to bring new and useful insights to discourse analysis of newspapers as opposed to confirming a traditional analysis of the written text. Nikolajeva and Scott (Reference Nikolajeva and Scott2000) discuss the ‘dynamics of word/image’ interaction, noting how relationships between the two can be complementary (e.g. each giving similar information or where one mode amplifies or expands on the meaning of the other) or counterpointing (e.g. where words and images provide alternative information or contradict one another). While both kinds of relationship can be useful, it would be hoped that aspects of a visual analysis would provide more than a simple confirmation of the findings of an analysis of written text.

Rather than examining a larger corpus of news articles about obesity, it was decided to choose a different topic: Muslims and Islam. This is a topic which one of the authors had worked on previously, although only through examining written text corpora (e.g. Baker et al. Reference Baker, Gabrielatos and McEnery2013). In that study a 143-million-word corpus containing news articles from 12 newspapers about Muslims and Islam published between 1998 and 2009 was built and analysed. In one part of the analysis the authors compared the newspapers together by identifying the keywords most strongly associated with each one. It was decided to replicate that analysis on a similar corpus, using more recent articles that included images.

Our research questions are:

1. To what extent does analysis of image tags provide new insights above the linguistic analysis?

2. What are the distinctive representations of Islam and Muslims in nine UK national newspapers between December 2022 and November 2023?

As a byproduct of the analysis, we also considered the extent to which representations had changed or remained the same, compared to the Baker et al. Reference Baker, Gabrielatos and McEnery2013 study.

In Sections 2 and 3 we provide literature reviews, focussing first on research which has tried to carry out analysis of images or which has combined analysis of image and text together. The second literature review looks at news studies relating to the representation of Muslims and Islam, with a particular focus on corpus-related research. In Sections 4 and 5 we provide an account of how we created the corpus for this study and how we carried out the analysis. In Section 6 we outline the six stages of analysis that we performed on the corpus, which involved analysing distinctive words and images separately and together as well as comparing the findings of different parts of the analysis against one another. Finally, the Element has a concluding section which critically considers the value of building and analysing a multimodal corpus, along with directions for future research.

2 Integrating Images in Corpus Linguistics

A multimodal corpus can be broadly defined as one which contains more than one semiotic system (such as sound and moving images). Consideration of all of the different forms of multimodality is beyond the scope of this Element, and we are specifically concerned with those which contain written text and still images. Multimodal corpus analysis has required developments both in visual analysis and corpus linguistics, two fields which did not initially acknowledge one another very often. An early study, by Smith et al. (Reference Smith, McEnery and Ivanic1998), described the creation of a corpus of children’s writing, which contained a combination of text and drawings. In order to integrate the images into the corpus, the researchers coded each image with a single tag: <FIGURE>. Although no further information was provided about the images, there were hypertext links to online scans of the original texts so that the images could be viewed by analysts if required.

Prior to the emergence of online image taggers, images tended to be analysed by hand with user-defined categorisation schemes. Kress and van Leeuwen (Reference Heuer, McClure and Puhl1996) describe a detailed, multi-dimensional way of categorising images, considering phenomena like participants, processes, structures, colour, position of the viewer, modality and composition. It is unlikely that every aspect of the scheme could be feasibly implemented, especially on a large dataset, so more typically, analysts would need to decide which elements were most relevant to their research questions and the set of images they wished to analyse.

Some studies of news discourse have identified features that are not based on a generalisable scheme but on a small number of criteria that are relevant to a particular research focus. For example, Heuer et al. (Reference Heuer, McClure and Puhl2011) analysed photographs in articles relating to obesity from news websites, classifying them according to five criteria which were deemed to denote stigmatisation, such as images showing people eating unhealthily or images where heads and faces were not shown. Similarly, Collins (Reference Collins, Rüdiger and Dayter2020) created a simple classification scheme for images within Facebook posts, as well as annotating emoji. In his study, such labels could be counted as ‘tokens’ within keyword or collocation analyses.

Bednarek and Caple (Reference Bednarek and Caple2012) describe how images can construct the values by which some events or facts are judged as more newsworthy than others (Galtung and Ruge Reference Galtung and Rüge1965). For example, they note how a news value like negativity can be shown by use of a low camera angle, to indicate the status of the participant in the image, or a high camera angle, which puts the viewer in a dominant position. Negativity can also be represented through pictures of people experiencing emotions like sadness or images of disasters and accidents. Subsequently, the same researchers used an integrated approach to identifying news values, called corpus-assisted multimodal analysis (Bednarek and Caple Reference Bednarek and Caple2014). Corpus analysis techniques enabled the identification of keywords, frequent words and bigrams which pointed to different news values, while the images were analysed separately, then the two sets of analyses were considered together. In Bednarek and Caple (Reference Bednarek and Caple2017) a relational database was created using UAM Corpus Tool (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell2008), where the codings of images and news headlines could be compared.

A similar approach was taken by Sibai and Jaworska (Reference Sibai and Jaworska2024), who analysed representations of Saudi women in UK and Saudi news articles. For the visual analysis, the authors utilised the ‘role allocation’ part of van Leeuwen’s (Reference Van Leeuwen2008) framework, with images classed into four categories: agent (transactive), agent (beneficialised), patient (intransactive) and patient (passive). Chi-square tests were carried out on the category frequencies across newspaper types to identify whether there were significant differences in the representations. Then, separately, a corpus analysis was carried out on the text, which involved deriving and analysing word sketches (grammatically grouped sets of collocates) of terms relating to Saudi women, using the tool Sketch Engine and focussing on role allocation patterns. Subsequently, the two sets of results were compared through triangulation, with the authors finding that UK articles tended to represent Saudi women as driving cars visually more than textually, whereas Saudi articles tended to give equal space to both images and text for this kind of representation. Sibai and Jaworska (Reference Sibai and Jaworska2024) argue that considering just one mode of analysis would have produced partial findings and limited interpretations.

While the above study considered the two modes separately, so could be seen as a ‘mixed-methods’ analysis as opposed to being multimodal, McGlashan (Reference McGlashan2016, Reference McGlashan, Moya-Guijarro and Ventola2021) carried out an analysis of a corpus of children’s books which featured same-sex families, identifying keywords and key clusters and then linking them to the images they occurred with. For example, one key cluster – love each other – was found to relate to descriptions of such families, with members of the families described as loving each other. Examination of the pictures which occurred in the vicinity of this cluster revealed that family members were often depicted as hugging one another, which indicated that the meaning of love each other was implied to involve demonstration of physical affection, a facet which was not mentioned in the accompanying written text. McGlashan (Reference McGlashan, Moya-Guijarro and Ventola2021) uses the term collustration, a portmanteau of concordance and illustration, to consider ‘repeated co-occurrences between representations in linguistic and visual semiotic resources across numerous texts’ (227). This kind of multimodal analysis was carried out by hand, so was restricted to a small number of linguistic items.

The process of tagging an image, either manually or automatically, is somewhat different to employing an encoding scheme to written text. Schemes like CLAWS (Garside Reference Garside, Thomas and Short1996) and USAS (Wilson and Thomas Reference Wilson, Thomas, Garside, Leech and McEnery1997) apply part-of-speech or semantic tags, respectively, to every word in the corpus, and each word receives a single tag (although automatic taggers can sometimes suggest several possible tags in descending order of confidence of accuracy). For example, in the phrase ‘Madonna hits album’, part-of-speech taggers should assign a tag like ‘plural common noun’ to the word hits, although they may mistakenly assign a verb tag instead. In such cases, human annotators would notice the error if they encountered it. Conversely, an image tagging system would typically require multiple tags to be assigned to a single image, and it is not always easy for human raters to agree on their accuracy. For example, Gatt et al. (Reference Gatt, Muscat, Paggio, Farrugia, Borg, Camilleri, Rosner and van der Plas2018) report on a study which used crowdsourcing to annotate images of faces. Inter-coder agreement regarding the descriptions of the faces was variable, with coders having lower agreement on facial emotions or whether descriptions contained inferred elements. However, large datasets of images that have been tagged through crowdsourcing can be used to train automatic taggers, and it is in the current decade that we begin to see a new generation of visual analysis studies which have employed such taggers. An example is Christiansen et al. (Reference Christiansen, Dance, Wild, Rüdiger and Dayter2020), who used Google Cloud Vision to tag a large corpus of tweets. They labelled their analysis ‘visual constituent analysis’, and the study used the tags to create downsampled corpora on the basis of specified elements (e.g. tweets which mention Donald Trump vs. tweets which contain images of him). The written elements of the corpora were then analysed through a comparison of their semantic tags.

Todd et al. (2023) used Google Cloud Vision to tag a corpus of online advertisements, analysing it with their own tool (Multimodal Corpus Analysis Tool) to produce frequency counts of codes and to assess the likelihood of the co-occurrence of codes. Among their findings, they reported that there was a preference in the adverts for text to be positioned on the left, while pictures appeared on the right – a finding which went against general accepted theories of information value in multimodal texts. Additionally, most use of colour in the adverts tended to reflect accepted meanings (e.g. red means urgency), apart from blue, which signified familial love.

The pilot study (Baker and Collins Reference Baker and Collins2023) described in Section 1 used WordSmith Tools to integrate analysis of Google Cloud Vision-assigned image tags and text, by analysing the keywords which appeared in articles that contained the most frequent tags in the corpus. As the corpus included image tags in the same position that the images in the articles appeared, it was also possible to carry out collocational analyses, for example, by identifying the words which frequently occurred in the vicinity of images that had been assigned a particular tag. The study in this Element aims to investigate this avenue further by building and analysing a multimodal corpus of news articles about Islam. Although we use the same automatic tagger as Baker and Collins (Reference Baker and Collins2023) – Google Cloud Vision – we should note that it has been integrated into Vertex AI, which is how it will be referred to from this point. However, before we describe our corpus of articles about Islam, it is pertinent to review relevant research which has examined news representations of this topic.

3 Representations of Islam and Muslims in the News

As far back as the 1990s, research on news relating to Islam in countries that do not have Muslim majorities has largely tended to report negative representation. Here we take representation to mean the ways that something is depicted through use of a range of techniques including evaluation, metaphor, narrative, connotation or argumentation strategies. Early studies tended to be small-scale and used a variety of methods, such as counting words deemed to be relevant, identifying topics and themes manually, or conducting qualitative analysis of argumentation patterns and discourses. For example, Awass (Reference Awass1996) examined American articles, finding that Islam was depicted as a threat to Western security as well as being associated with fundamentalism and terror. A 2001 study of Australian newspapers by Dunn (Reference Dunn2001) reported that Muslims were constructed as ‘fanatic, intolerant, fundamentalist, misogynist [and] alien 75% of the time, whereas positive constructions accounted for 25% of cases’ (296). Poole (Reference Poole2002) combined focus group interviews with a quantitative analysis of a corpus of 1990s articles from four British newspapers, finding that British Muslims were frequently represented as criminal, extremist, irrational and antiquated, as a threat to liberal values and democracy, as involved in corruption and crime, and as influenced by Muslims outside the UK. Similarly, Richardson (Reference Richardson2004) carried out a qualitative analysis of British broadsheets published in 1997, focussing on argumentative themes and concluding that processes of separation, differentiation and negativisation ‘predominantly reframe Muslim cultural difference as cultural deviance, and increasingly, it seems, cultural threat’ (232).

Such studies have tended to focus on news text as opposed to images, although an exception is Moore et al. (Reference Moore, Mason and Lewis2008), who considered both aspects in their analysis of British articles published between 2000 and 2008. First, a content analysis (which identified themes and topics through close reading) of the written text focussed on types of stories, for example, finding an increase in stories which reported cultural and religious differences between Muslims and non-Muslims. The three most common discourses around British Muslims framed them as a terrorist threat and as dangerous/irrational and framed Islam as part of multiculturalism. Second, the visual analysis categorised people in images according to their sex, what they were represented as doing, what country was shown, whether people were alone or in groups and what the type of image was (photojournalism, police mug shot, cartoon, graphic, etc.). The authors found widespread use of police mug shots when depicting Muslim men, as well as images taken outside police stations and law courts. Muslim men were shown much more frequently than Muslim women and Muslims were often identified as Muslims rather than as individuals with distinct identities: for example, they were less likely to be shown in terms of their profession. A third part of the analysis involved qualitative case studies of a small number of articles, which identified cases where information had been exaggerated or distorted, such as the claim that parts of Britain were becoming Muslim-only ‘no-go’ areas. The analysis shows the value of considering different modes and methods in a single study.

More recently, large-scale corpus studies have been carried out on news representations of Islam, using software to identify patterns based on millions of words of data. For example, Baker et al. (Reference Baker, Gabrielatos and McEnery2013) conducted a corpus analysis of 143 million words of British news articles about Islam and Muslims over a decade. Methods used included analyses of the collocational patterns of the words Muslim and Islam, and keyword comparisons of different newspapers and time periods. A key finding was that references to conflict were highly frequent throughout the corpus, with Muslims regularly represented as involved in violence, crime and terrorism, showing anger toward others, or being attacked or discriminated against. Terms relating to terrorism were actually higher than those relating to Islam, even though the Islam-related terms were the ones used to identify the articles to appear in the corpus. Articles tended to strongly focus on the news value of negativity, with few ‘good news’ stories or stories which reported on Islamic culture and traditions. Muslims were described as separate from other people, while there was evidence that conservative tabloid discourses around Muslims had influenced broadsheet reporting over time.

It is worth reporting on a couple of more recent studies, to obtain a better sense of the contemporary context that the current research occurs in. For example, Brookes and Curry (Reference Brookes and Curry2024) created small corpora of news texts relating to Islamophobia in British broadsheets, taken from the years 2005, 2010, 2013 and 2021. They then identified keywords that were shared across each period, as well as those which had newly emerged, when compared to the previous period. They found that while there was initially scepticism about the extent of Islamophobia in the UK, and concerns about over-reporting, by 2010 there were moves towards equating Islamophobia with right-wing extremism and racism, with 2021 showing reference to institutional Islamophobia. While this study indicates a gradual improvement on one aspect of representation related to Islam, another diachronic study by Baker (Reference Baker and Al-Azami2023a) presents a more mixed picture. This study considered use of words relating to terror and strength of belief (e.g, extremist, devout and moderate) over time in British articles about Islam. While such words tended to decrease over time when they collocated with Muslim(s) and Islamic, collocations of the extreme words with Islam and Islamist increased over time, indicating that newspapers had become more sensitive about associating extremism with the religious identity but were increasingly likely to connect the religion to extremism – a subtle but important distinction. These recent studies indicate a more mixed picture in terms of representation (at least for the UK), which raises a question relating to the extent to which there are differences between newspapers, as well as the role of images in news representations of Islam, both of which the present study seeks to address.

4 Data Collection

The corpus for this study consists of articles about Islam from the British national press, published between 1 December 2022 and 30 November 2023. Before describing how the corpus was collected, it is pertinent to consider relevant context and events, both internationally and in the UK, which help to frame the kinds of stories that were reported on around Muslims and Islam during the period under examination.

For example, 2023 saw the coronation of a new king, Charles III, after the death of his mother, Elizabeth II, in September 2023. The same year also saw the UK anticipating an election, with opinion polls putting left-of-centre opposition party, the Labour Party (under Sir Keir Starmer), in the lead, following increasing dissatisfaction with the ruling party, the Conservative Party, which had recently appointed its fifth leader, Rishi Sunak, in 12 years. In the election that took place in 2024, the Express, Daily Mail and Telegraph supported the Conservative Party while the Mirror, Guardian, Independent and Sun supported Labour. The Daily Star and Times did not back either party.

In terms of prominent stories relating to Islam, in Scotland, a Muslim, Humza Yousaf, served as first minister and leader of the Scottish National Party (SNP) from March 2023 to May 2024. At the time of his appointment he was the first Muslim leader of any Western nation. And on 7 October 2023, during the Jewish religious holiday Simchat Torah, the militant resistance group Hamas led an attack on an area controlled by Israel called the Gaza Envelope, using at least 3,000 rockets and paraglider incursions and killing 1,139 people. Of these, 364 were killed while attending a music festival, and 250 people (soldiers and civilians) were taken hostage. At least 44 countries labelled the attacks as terrorism, including the UK. Israel retaliated with attacks on the Palestinian territory called the Gaza Strip, bombing and killing members of Hamas and, as reported in the UN impact snapshot (UN-OCHA 2024), 15,207 civilians by the end of November 2023. The conflict led to protests around the world, including in the UK. Although these events occurred 10 months into our collection period, stories relating to them dominated the corpus, with the 10 most frequent lexical words across the entire corpus being Muslim, Israel, police, Hamas, Gaza, year, Islamic, told, Israeli and years.

When creating a news corpus it is common to identify a search term, consisting of words and phrases, so that articles containing those terms can be included. For this corpus, the search term was reasonably simple, consisting of just two words – Islam and Muslim. A more complex search term (involving 35 words and phrases) had been used in the Baker et al. (Reference Baker, Gabrielatos and McEnery2013) study, although it was found that this resulted in a number of unwanted articles appearing in the corpus (e.g. the longer search term retrieved all articles containing the word Sunni and any related terms, and this resulted in unwanted articles which mentioned the village of Sunningdale appearing in the corpus). Even the term Islam resulted in unwanted articles, due to the fact that Islam is a surname, so when building the present corpus, concordance analyses of all instances of Islam were undertaken and 14 articles were removed.

In Baker et al. (Reference Baker, Gabrielatos and McEnery2013), articles were collected from 12 British newspapers, and it was decided to replicate this model. However, one newspaper was no longer in print (the Business), whereas another (the People) was now published on the Mirror website. We also classed the Observer as a Sunday edition of the Guardian, as its stories appeared on the Guardian’s website. Therefore, we collected articles from the websites of nine newspapers: the Daily Mail, the Daily Star, the Express, the Guardian, the Independent, the Mirror, the Sun, the Telegraph and the Times.

An advanced Google search was used to display all indexed pages on a given domain that contained the search terms. A model search for the Telegraph was as follows: site:https://www.telegraph.co.uk “muslim” OR “islam”. Additionally, the search selected the time span as being between 1 December 2022 and 30 November 2023. After identifying all URLs linking to articles containing the search terms from each of the nine newspaper websites using this approach, the URLs were scraped using custom Python scripts. As part of this process, the structure of each newspaper website was analysed and unwanted elements such as ‘read more’ or links to related stories, as well as overview pages and image galleries with no text, were removed. As part of the quality control on the scraped documents, several articles were identified that, despite being published on the dailymail.co.uk domain, contained Australian reporting. This is due to the fact that the Daily Mail hosts Australian articles on www.dailymail.co.uk/auhome rather than on a separate Australian domain. All such Australian articles were consequently removed. The last step of the data cleaning process identified articles mentioning Islam exclusively in the context of the name of martial artist Islam Makhachev and these were excluded also. When downloading the files, the full html was preserved and used as the basis for downloading all embedded images. Placeholders for the images at the relevant positions within the article were created, the downloaded images were named accordingly, and then the remaining html elements were removed. Alongside the articles, wherever possible the publication date as well as the names of the author(s) were recorded.

The resulting corpus comprised just over 1.5 million tokens and 1,890 articles. There were 8,546 images across these articles, which (after some tags had been removed, during the process described in Section 5) received 89,133 image tags in total. Compared to the earlier pilot study (Baker and Collins Reference Baker and Collins2023), which utilised a corpus of 104,118 words and 358 images, this corpus is 15 times larger and contains 23 times as many images.

A detailed breakdown of the corpus is shown in Table 1. We have coded each newspaper with letters which indicate if they predominantly take a conservative (c) or liberal (l) political perspective, and whether they are broadsheets (b) or tabloid (t) format. We note higher numbers of articles in the Telegraph and Times (the two right-leaning broadsheets), along with relatively low numbers of images per article. However, the Guardian (a left-leaning broadsheet) has the fewest articles and fewest images per article. The Daily Mail has the most images per article and the most images in all (about a quarter of the total), while the Sun also has a high number of images. (Both are right-leaning tabloids.) The Daily Mail and Times have the longest articles (on average), while the shortest ones are from the Express, Independent and Mirror.

Table 1 Breakdown of the corpus by newspaper

| Total tokens | Total articles | Average length of article (words) | Total images | Total image tags | Average number of images per article | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Mail (c,t) | 237,044 | 208 | 1139.63 | 2,350 | 23,155 | 11.29 |

| Daily Star (c,t) | 72,422 | 101 | 717.05 | 583 | 6,664 | 5.77 |

| The Express (c,t) | 119,123 | 197 | 604.68 | 843 | 6,694 | 4.27 |

| The Guardian (l,b) | 82,930 | 99 | 837.67 | 195 | 1,937 | 1.96 |

| The Independent (l,b) | 162,839 | 251 | 648.76 | 464 | 4,684 | 1.84 |

| The Mirror (l,t) | 153,412 | 221 | 694.17 | 922 | 10,151 | 4.17 |

| The Sun (c,t) | 171,919 | 241 | 713.35 | 1,493 | 17,518 | 6.19 |

| The Telegraph (c,b) | 228,087 | 283 | 805.96 | 633 | 6,996 | 2.23 |

| The Times (c,b) | 323,817 | 289 | 1120.47 | 1,063 | 11,334 | 3.67 |

| Total | 1,551,593 | 1,890 | 820.94 | 8,546 | 89,133 | 4.52 |

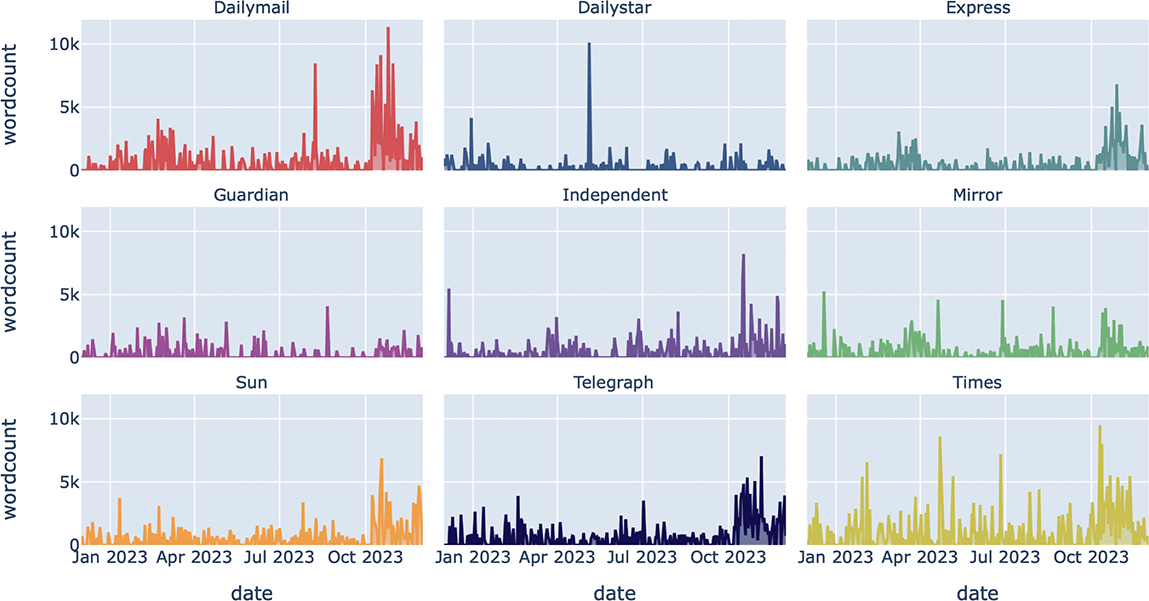

Figure 1 provides plots which show the number of words published on Muslims and Islam each day, for the nine newspapers. It can be seen, for example, that several newspapers (especially the Daily Mail, Express, Independent, Sun, Telegraph and Times) started showing more interest in Islam in the last few months of our data collection period (which coincides with the conflict between Hamas and Israel).

Figure 1 Overview of timelines showing the number of words in the corpus per day and per newspaper.

Figure 1Long description

Several newspapers show peaks towards the last few weeks of data collection, including The Daily Mail, The Express, The Independent, The Sun, The Telegraph and The Times.

A final general methodological point worth mentioning here is that transforming multimedia articles into a format suitable for corpus compilation necessitates placing the image between blocks of text when, in fact, the true layout might place the image to the right or left of a paragraph, and have text flowing around the image. While it is theoretically possible to include information about the page layout in the image metadata within the corpus, this runs the risk of misrepresenting true use cases since most websites have different display options based on the screen size of the device they are being viewed from.

5 Tagging the Images

Each image was saved separately and then run through Vertex AI, receiving a set of image tags. This, again, was achieved using a custom Python script. This script instantiates an ImageAnnotatorClient and tags each image individually. The maximum number of tags per image was set to 50 to mirror settings that had been used by CloudVision in the Baker and Collins (Reference Baker and Collins2023) study, and Vertex AI confidence ratings were obtained alongside each tag. After signing up for an account, the first 1,000 images were tagged for free, while it cost $1.50 to tag each subsequent set of 1,000 images.Footnote 2

Vertex AI makes use of different classes of tags. For example, LANDMARK detects the presence of particular landmarks (like the Eiffel Tower), LOGO identifies logos (like Coca-Cola), SAFESEARCH identifies the likelihood of content that could be rated as adult, spoof, medical, violence and racy, and IMAGE PROPERTIES gives the dominant colours in the image. Having experimented with different categories in Baker and Collins (Reference Baker and Collins2023), we had decided that a category of tag referred to as LABEL was the most useful for analysing our corpus. This class involves a range of labels being assigned to each image (as mentioned earlier, there are over 20,000 label types), with each label being a generalised textual description of the content of the image. A confidence score (from 0 to 1) is also automatically assigned to each label, with the default cut-off point being 0.5, so Vertex AI only returns labels where it is at least 50% confident that the label is correct.

In the pilot study (Baker and Collins Reference Baker and Collins2023) the default 50% confidence level was maintained when building the corpus. However, as noted earlier, during the analysis part of that study some tagging errors were noted, so for this study it was decided to carry out a more systematic analysis of tagging accuracy, aiming to improve it if too many errors were found.

In order to determine the extent to which Vertex AI’s label tagging was accurate, we took 100 images at random from the corpus and then two human raters independently assessed the accuracy of all of the tags assigned to each image. This resulted in the assessment of 2,530 tags, or 25.3 tags per image on average. Table 2 shows the distribution of confidence levels that Vertex AI assigned each tag. The average confidence score assigned to an image was 0.7.

Table 2 Number of tags assigned to each confidence level by Vertex AI

| Confidence level | Number of tags |

|---|---|

| 49−60 | 697 |

| 60−70 | 637 |

| 70−80 | 583 |

| 80−90 | 374 |

| 90−100 | 239 |

Inter-rater consistency was reasonably good. The raters agreed that 1,508 tags had been correctly assigned, and also agreed that 508 tags were incorrect. There were 498 cases where they disagreed (so overall there was an average agreement of 79.6%). The 10 tags where there was most disagreement were: Electric_blue, Portrait, Advertising, Businessperson, Spokesperson, Flash_photography, Luggage_and_bags, Coat and Cap.Footnote 3 It was found that occasionally, the tagger assigned the same tag twice to a single image, and for the final version of the corpus, such duplicate tags were removed.

Based on the average error ratings it was found that Vertex AI was accurate 70% of the time. This figure was deemed to be not high enough to warrant using the image tags in the corpus, so experiments were carried out by raising the confidence threshold to a number higher than 0.5 in order to see how that would impact on overall accuracy. It was found that by raising the confidence level to 0.7, around half of the original tags would be removed, but overall accuracy would increase to 82%. This was an improvement on 70% accuracy but was still deemed to be too low.

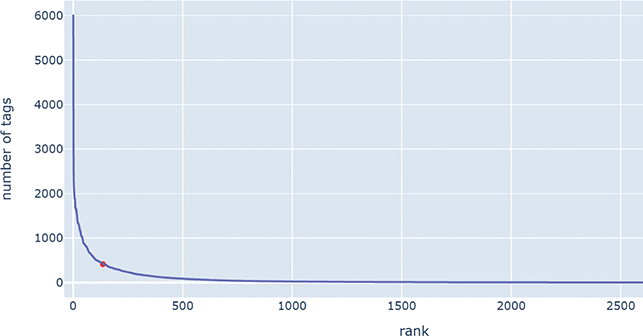

It was then decided to identify the high-frequency tags and subject each one to a further analysis by looking at 15 images which contained such a tag. High-frequency tags which were assigned inaccurately most of the time could then be removed from all of the images. In order to determine what counted as a high-frequency tag, we plotted the number of tags against their frequencies. For example, there were six tags (AlloyWheel, Balloon, ContactSport, CosmeticDentistry, Dishware and Floristry) which occurred six times each in the corpus, whereas there were two tags (Infrastructure and Leg) which occurred 99 times each. Figure 2 plots these sets of figures for all the tags in the corpus, with the x-axis showing the number of occurrences of a tag, and the y-axis showing the number of tags which have that occurrence. The curve in Figure 2 shows that the majority of the tags in the corpus only appeared a very small number of times, and conversely, there were a small number of very frequent tags (10 tags occurred at least 1,680 times each in the corpus). The point where the slope increases most strongly in the figure is at the tag that occurred 414 times (Bag) – marked as a dot in the figure. There were 135 tags that were more frequent than Bag, so we took all of these (plus Bag), and for each of these tags we selected 15 images at random that had been assigned that tag. This gave us 2,040 images to examine.

Figure 2 Number of occurrences of image tags.

Again, two independent raters assessed the accuracy of each tag. Inter-rater consistency was found to be reasonably high, with an average percentage overlap of agreement of 0.79. The most accurately assigned high-frequency tags in the dataset were Building, Chin, Car, Human and Protest, whereas the least accurately assigned ones were Winter, Gesture, FashionDesign, AutomotiveDesign and Rebellion. This suggests that the tagger was somewhat better at identifying concrete phenomena (e.g. things that can be touched) as opposed to abstract or conceptual phenomena. From our sample, it was found that 96 of the 136 high-frequency tags were accurately assigned less than 70% of the time, so it was decided to remove all instances of them from the whole corpus. The accuracy of three of these tags (Beard, Moustache and Military) was slightly under 70%, but instead of removing them it was deemed that they were likely to be relevant to the analysis of the representation of Islam. These tags were included in the corpus, and in subsequent analyses we were careful to consider the possibility of tagging errors around them. The other 37 highly accurate tags were retained in the corpus, even in the cases where Vertex AI had assigned them a confidence level of lower than 70%. Having made these additional tweaks, we estimate that the overall average accuracy of tags had increased to around 90%, which was deemed to be acceptable to carry out an analysis.

So, to sum up, for the final version of the corpus, we first removed high-frequency tags that were less than 70% accurate. Then, tags with less than 0.7 confidence were removed, unless they were high-frequency tags which we had manually rated as more than 70% accurate. Overall, 20% of the tags in the corpus were below the 70% confidence level, but these were all high-frequency tags which had previously been deemed to have a high accuracy.

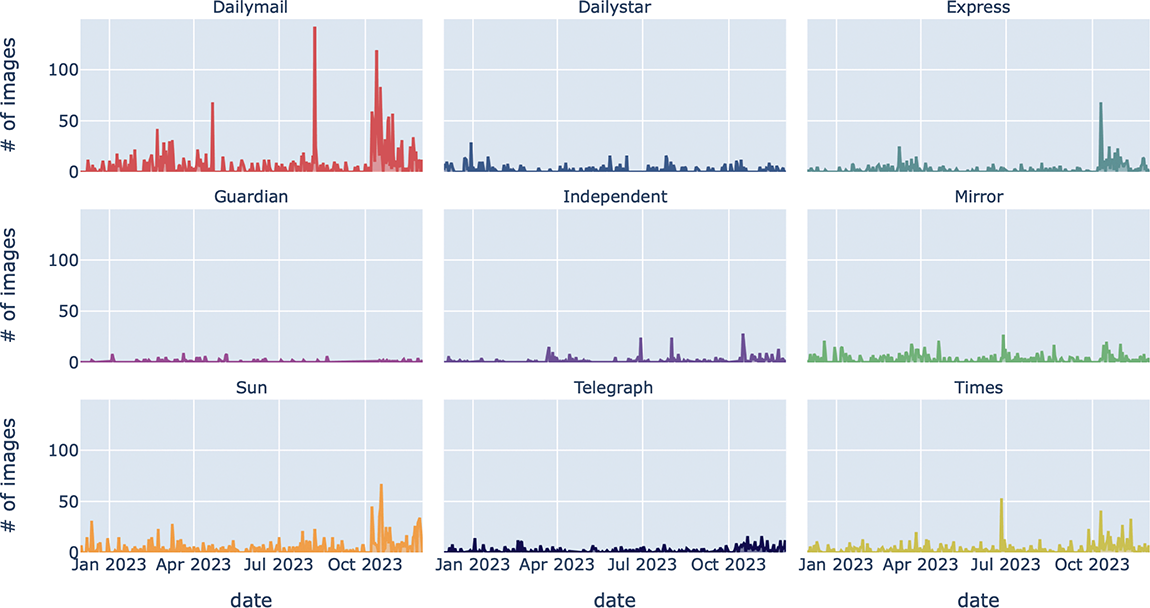

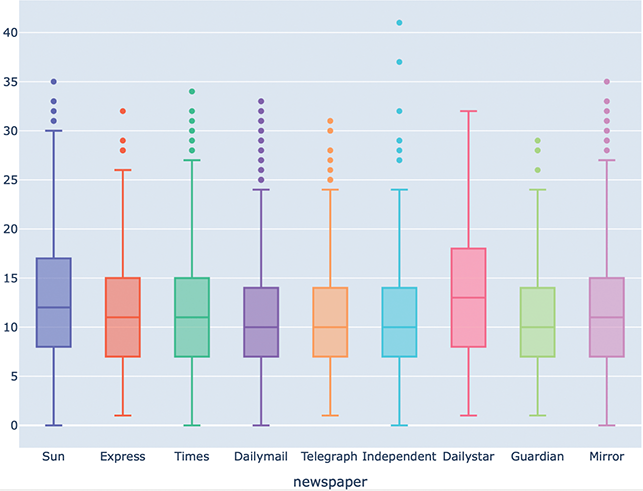

Figure 3 shows the number of images per day for each newspaper. It can be seen that the Daily Mail contributed more images than other newspapers, while the Guardian, Independent and Telegraph had fewer images. There are spikes for the Daily Mail, Express, Sun and Times in the latter months of the corpus (which coincide with the conflict between Hamas and Israel). Figure 4 shows the average number of image tags per image for each newspaper, with the Daily Star having images that were assigned more tags, generally, than other newspapers. As we will see later, this newspaper tended to have a high number of images containing people, so tags referring to body parts and clothing were frequent for this newspaper. Also, body parts and clothing tended to be easier for the tagger to accurately identify. In contrast, other newspapers might have been more likely to have had other kinds of tags, which were removed from the analysis because they were likely to be inaccurate.

Figure 3 Overview of timelines showing the number of images contained in the corpus per day and per newspaper.

Figure 4 Boxplot showing the number of tags per image for each of the nine newspapers.

Figure 4Long description

In contrast, newspapers such as The Daily Mail, The Telegraph, The Independent and The Guardian tended to assign fewer tags per image.

Due to the multimodal nature of the corpus and the file requirements of state-of-the-art corpus software, it was necessary to store the image data in separate files containing the image tags alongside different versions of the traditional text-based components. CSV files containing the tags only were created, since it is recommended practice to run the image tagger only once and store the results in CSV or JSON files, for example, due to the environmental and financial cost of running the tagger.

An example of the structure of these CSV files is presented below, with each line containing an image tag, followed by its confidence level assigned by the tagger.

Face, 0.9832

Smile, 0.9771

Red, 0.8102

Beauty, 0.7497

LongHair, 0.7382

CompetitionEvent, 0.7234

HumanLeg, 0.6843

Chest, 0.6817

Sports, 0.6588

Grass, 0.6266

For the first textual version of the corpus, henceforth referred to as the ‘development version’, each newspaper website was accessed to identify the web layouts used and extract the textual elements relevant to the project. This entailed accessing the title, subtitles, captions where possible, and the body of the text, while excluding elements such as advertisements and links to further articles. Authorship and date information was also retained and stored separately for use in the XML version of the corpus, as discussed in the following paragraphs. In the development version, only the textual elements were retained, alongside placeholders pointing to the corresponding image files, as in the following excerpt:

.@@@Dailymail_2022–12–09_RachMusl_0_IMG_0@@@.

<title>Muslim nations ‘proposed Islamophobia World Cup armband’</title>

After identifying appropriate thresholds for retaining or discarding tags on the basis of accuracy evaluations, a second version of the corpus, the WordSmith version, was created. Since WordSmith does not allow XML metadata to be imported, this version contains the text of each article with lists of image tags in place of the images, using a simplified format, as shown in the following example:

Shocking footage showed the moment a teacher kicked the hands of Muslim students who were praying as she dismissed it as ‘magic’. The students appeared to remain calm when the teacher entered the classroom and started to blow her whistle at them. Despite her attempt to disrupt their prayer time, they continued. RELATED ARTICLES.

<xxxWater>

<xxxLight>

<xxxSnapshot>

<xxxTree>

.

<xxxWater>

<xxxBuilding>

<xxxVehicle>

<xxxTree>

<xxxCity>

<xxxUrbanDesign>

<xxxAsphalt>

<xxxRoad>

<xxxGrass>

<xxxStreet>

.

In the excerpt above, after some initial text, there are two images, with their respective tags delimited by full stops. This enabled us to identify collocates of image tags within a single image in WordSmith, by treating each string of tags as a ‘sentence’ and specifying that a collocate search should not run over sentence boundaries. We assigned the letters xxx to the start of each tag to make them more easily distinguishable from their equivalent word in the corpus and to aid searches within WordSmith. (Note, however, that the xxx prefix has been removed from the tags given in all subsequent examples.) The news article files were saved as text only and were used with WordSmith when analysing just the written aspects of the corpus, to carry out concordances, identify collocates of words and create wordlists and keyword lists. This approach was taken to ensure compatibility with the pilot study.

The third version of the corpus consisted of XML files containing the full metadata (such as author, date and newspaper) and all text enclosed in <p> and </p> tags (indicating paragraphs). The image tags and their confidence levels are represented as follows in this version:

<img>< tag type=”tag” weight=”0.8814”>Building</tag>

<tag type=”tag” weight=”0.7807”>Gas</tag>

<tag type=”tag” weight=”0.7696”>Heat</tag>

<tag type=”tag” weight=”0.6423”>City</tag>

<tag type=”tag” weight=”0.617”>Tree</tag>

<tag type=”tag” weight=”0.5664”>Sky</tag>

<tag type=”tag” weight=”0.52”>Asphalt</tag>

</img>

For this project, a simple application (called Image Tag Explorer) was created, which allowed the user to identify all of the images from a particular newspaper which occurred (or didn’t occur) in articles that contained a particular set of words or had been tagged with a particular set of tags.

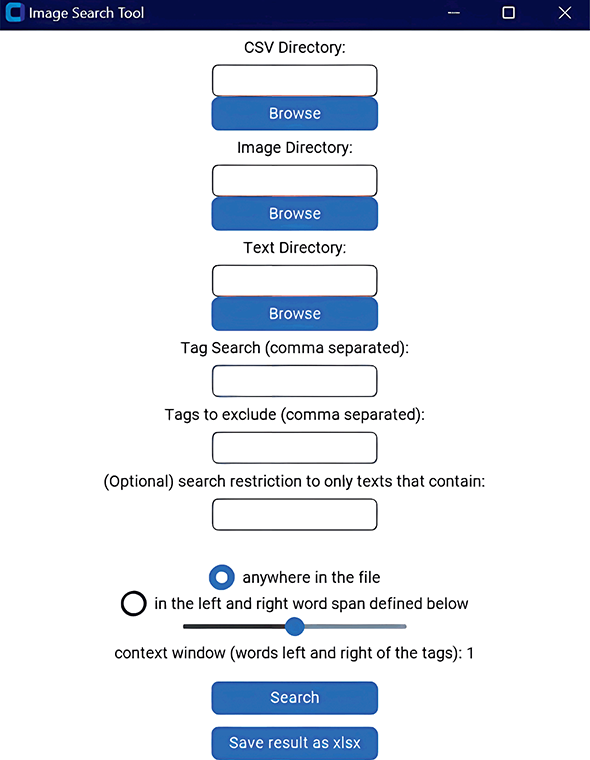

Figure 5 shows the application’s interface. The user specifies where the tags are stored (CSV directory), where the image files are stored (image directory), and where the XML version of the corpus is stored (text directory). Then, the user has the option to search for images with one or more tags, or images not containing one or more tags, as well as searching for textual elements that need to occur alongside the image in an article either anywhere within the file or within a certain span above and/or below the image.

Figure 5 Image Tag Explorer.

Figure 5Long description

The screenshot shows the interface where users enter the file directory paths for stored texts and image tags on their computer. They can specify the image tag they want to search for, exclude certain tags, and optionally filter results to include only news articles containing a specific word.

After pressing the ‘search’ button, the tool shows the images from the corpus which match the filtering criteria, one at a time. The ‘a’ and ‘d’ keys (corresponding to backwards and forwards, respectively) can be used to cycle through the images. The rationale behind designing the Image Tag Explorer was that a manual inspection of AI-tagged materials is paramount in order to ensure their robustness.

6 Analysis

In order to answer the research questions about the most distinctive representations associated with each newspaper, we used the concept of keyness (Scott and Tribble Reference Scott and Tribble2006). Keywords are a concept invented by Mike Scott, the creator of WordSmith, and can be defined as words which appear in a corpus (or section of a corpus) statistically significantly more often than would be expected when compared against a second corpus or section of a corpus (Scott Reference Scott1997: 236). A positive keyword occurs more often than expected, whereas a negative one occurs less often than expected. Keywords do not usually reveal the most frequent forms of language use in a (sub-)corpus but instead give an indication of words which are distinctive of it. A keyness analysis can help to reveal the preoccupations or biases within a set of texts which may be quite subtle and missed by human analysts. In order to obtain a list of keywords, a corpus tool is used to derive frequency lists of all of the words in the two corpora that are being compared. Then a separate statistical test is run on each word, comparing the relative frequencies of the word across the two corpora, as well as taking into account the total number of words in each one. Words are then listed in order of keyness strength, and users are required to impose their own cut-off point to determine what counts as a keyword. Most corpus software uses predefined cut-offs, although they can be altered to reduce or increase the number of keywords found.

There are several techniques that can be employed to calculate keyness, and generally a distinction is made between tests which prioritise the level of confidence that a frequency difference exists (even if it is not necessarily a large difference) and those which prioritise the extent of the difference. The former are sometimes referred to as hypothesis-testing measures, such as the log-likelihood test or the chi-square test, and they tend to result in lists of reasonably high-frequency words (as the higher the frequency of a word, the more ‘evidence’ the test has to go on and the more likely it is that the word will be identified as a keyword). The second type of test, referred to as an effect size measure, prioritises the scale of difference in frequency between a word across two corpora. These tests, like the log ratio test or %diff, may return relatively low-frequency words, where differences in relative frequencies are large. Both measures can be useful: log-likelihood tests can identify high-frequency grammatical phenomena, where even a small relative difference can be meaningful because we would expect all texts to contain grammatical lexis to some extent. On the other hand, %diff can identify extremely distinct, low-frequency items, which may otherwise go unnoticed by human researchers.

Although the term keyword situates keyness within single words, it is possible to extend the concept to consider, for example, key lexical bundles, key morphemes or key sets of words. For the latter, it is possible to conduct keyness tests on automatically annotated corpora (e.g. corpora that have had tags assigned to words to indicate predetermined grammatical or semantic categories). For the purposes of this study, we carried out keyness tests on the words in the corpus, but we also carried out keyness tests on the tags assigned to the images in the corpus, in order to obtain lists of key image tags.

We used WordSmith 9 (Scott, Reference Scott2024) to obtain and analyse keywords. In order to compare newspapers against one another, we derived a set of keywords for each newspaper, comparing it against a sub-corpus consisting of the other eight newspapers. We experimented with different settings in WordSmith in order to ensure that for most cases we could obtain at least 10 keywords for each newspaper, and that keywords would not be too infrequent, while relative frequency differences between the two corpora would not be too small. After our experiments we defined a keyword as a word which had a minimum frequency of 3, appeared in a minimum of 5% of texts and had a p-value (used with the log-likelihood test) of 0.1 or lower, as well as a Bayesian information criterion (BIC) value of at least 2.5, a minimum log ratio of 0.5 and a minimum dispersion of 0.1. The log-likelihood test and the size of the two corpora are used in the BIC formula. Gabrielatos (Reference Gabrielatos, Taylor and Marchi2018) suggests that a BIC of 0–2 indicates a word that is barely worth mentioning, whereas anything from 2 to 6 shows positive evidence of a keyword, and above 6 is strong evidence. When choosing keywords, they were ordered according to log-likelihood score. The same procedure was also carried out on frequency lists which consisted just of the frequencies of the image tags, to identify key image tags.

Once we had obtained keywords we analysed them by examining their collocates (both co-occurring words and image tags), and carried out concordance searches to view them in context. When a keyword occurred more than 100 times, we examined 100 occurrences taken at random to identify the range of uses, as well as typical and rare uses. We also used the Image Tag Explorer to find which images tended to co-occur with particular words, or which images contained various combinations of image tags.

Our analysis involved six stages:

1. Analysis of the written text through keywords;

2. Analysis of the images through key image tags;

3. Comparison of the results of stages 1 and 2 together;

4. Multimodal analysis – identifying words which co-occur with the top image tag in each newspaper;

5. Multimodal analysis – identifying image tags which co-occur with the top keyword in each newspaper;

6. Comparison and evaluation of the results of stages 1 to 5.

We provide details on each of these stages in Sections 6.1 to 6.6.

6.1 Stage 1: Analysis of Written Text Through Keywords

We began the analysis by obtaining the 10 strongest keywords (those with the highest log-likelihood scores) from each newspaper. In WordSmith’s default settings, XML mark-up (i.e. anything which begins with < and ends with >) is ignored, so the frequency lists we created were derived only from the written text in the corpus, not the image tags.

As noted in the previous section, each keyword was examined through consideration of its collocates and concordance lines. (See Baker Reference Baker2023b for details of how this kind of analysis is carried out.) The main questions we tried to bear in mind while conducting these analyses were: (1) what was the function of the keyword (typically) in that newspaper, or what kind of effect did it have in terms, for example, of semantic meaning, evaluation or discourse function? and (2) how did this keyword specifically contribute towards representation of Muslims or Islam? Different keywords called for different kinds of analytical foci. For instance, nouns and proper nouns relating to people or countries could be analysed in terms of social actor representation: what kinds of actions they were shown to be carrying out; what actions were done to them; whether they were evaluated positively or negatively; and, in terms of perspective, how much space was given to them to express their views. Adjective keywords were examined in order to ascertain what they were describing and the extent to which they were used in positive or negative evaluations, while verbs were also linked to social actors. Pronoun keywords were considered in terms of author–reader relationships and gender representation. We also tried to make links between keywords, particularly if they were used in similar ways or collocated with one another. Table 3 shows the top 10 positive and negative keywords for each newspaper, ordered by keyness score. The positive keyness scores range from 576.55 to 42.40 while the negative keyness scores range from −420.37 to −7.51.

Table 3 Top 10 positive and negative keywords for each newspaper (frequencies in brackets)

| Positive keywords | Negative keywords | |

|---|---|---|

| Daily Mail | council (421), pictured (229), Friday (270), city (339), Gaza (641), Israeli (477), Israel’s (104), students (194), her (1,300), Koran (105) | local (61), king (49), British (139), says (115), these (100), still (77), met (63), most (146), much (82), idea (10) |

| Daily Star | her (637), Knoll (62), king (140), Mia (60), fans (101), boxing (49), god (97), she (513), I (578), Croatia (44) | community (22), Friday (7), countries (6), hospital (10), groups (10), forces (8), last (50), clear (5), pro (9), or (108) |

| The Express | remembrance (39), Palestine (127), jihad (108), Sir (106), Keir (91), BBC (74), Mr (205), Met (104), pro (99), weekend (58) | women (45), council (28), him (103), released (22), prison (18), head (30), men (32), Tuesday (14), schools (18), south (20) |

| The Guardian | UK (227), prevent (112), promotion (44), Saunders (27), rightwing (29), coronation (68), review (68), royal (68), Charles (50), extremism (77) | show (15), off (23), me (50), social (20), just (53), ceasefire (11), ban (4), Arab (5), mosque (21), wearing (6) |

| The Independent | Muslim (833), Quran (174), Muslims (373), Mr (388), religious (253), Sweden (157), pilgrims (67), Hajj (74), said (1353), hate (197) | Israeli (73), her (447), Hamas (183), hospital (22), you (237), my (157), Iran (35), prevent (16), children (65), Syria (35) |

| The Mirror | Ramadan (258), Eid (188), fasting (126), you (550), your (215), it’s (139), calendar (55), life (245), fast (101), Isis (129) | Hamas (145), anti (33), Israel (187), political (15), its (155), minister (52), protest (17), pro (19), Palestine (25), right (84) |

| The Sun | cops (86), rocket (119), hospital (224), Hamas (568), IDF (126), hostages (150), her (1,032), released (175), mum (110), blast (74) | that (1,197), Muslims (65), Muslim (268), religious (28), government (68), such (46), Jewish (32), council (31), law (36), protest (20) |

| The Telegraph | Mr (479), Iranian (188), Iran (259), IRGC (133), Iran’s (90), Semitism (75), Islamic (530), its (603), anti (292), regime (111) | her (389), she (451), I (672), you (300), family (102), me (138), my (215), Muslim (421), show (50), life (116) |

| The Times | writes (66), Yousaf (150), Binyamin (34), politics (114), gay (107), church (139), Scottish (104), Scotland (101), political (223), conservative (108) | man (171), death (141), city (142), sun (17), letter (23), streets (43), claimed (86), holiday (20), terrorists (65), hijab (33) |

We began the analysis with a consideration of the Daily Mail’s top 10 keywords, three of which relate to the Israel–Hamas conflict: Gaza, Israeli and Israel’s. To get a better idea regarding evaluation around the two sides of the conflict, we examined concordance lines of Gaza, identifying 100 cases of quotes or reported speech to obtain a sense of the extent that quotes were made either in support of or against either side. Of the quotes we examined, 78 made statements which showed support towards people in Gaza and 22 were against. Quotes against Gaza included those made by Benjamin Netanyahu. For example:

It was barbaric terrorists in Gaza that attacked the hospital in Gaza, not the IDF.

On the other hand, positive quotes tended to focus on attacks on civilians, as the following statement from a group of Labour councillors indicates:

The innocent civilians in Gaza have had nothing to do with this crisis and bear no responsibility for its outcome.

In order to compare this with the way Israel appeared in quotes in the Daily Mail, we decided to examine 100 concordance lines of Israel in which it was not a keyword, but was the equivalent term to Gaza, as opposed to Israeli and Israel’s (which were keywords). For our concordance analysis of Israel, 49 quotes were supportive, while 51 were against. Quotes against Israel tended to focus on its bombardment of Gaza, for example:

Israel continues to indiscriminately rain bullets and bombs on worshippers, murdering the old the young, attacking even funerals and graveyards.

Positive quotes focussed on the terror attack and kidnapping of Israelis by Hamas as well as criticisms of anti-Israel protests by Muslims (referred to as ‘Islamists’ in the second quote below):

We have never before in Israel experienced such a traumatic event, which will take years, if not generations, to overcome.

Islamists on the streets of London made ‘completely reprehensible’ calls for jihad against Israel.

The analysis suggests that the Daily Mail appeared more likely to quote people who were supportive of Gaza as opposed those who were supportive of Israel, at least in the period examined, which covers the first few weeks of the conflict.

The Daily Mail keywords city and council tend to occur together, referring to a number of city councils around the UK (including Birmingham, Leeds, Leicester, Manchester, Nottingham, Sheffield, Wolverhampton and Westminster). A closer examination of these instances indicates that they are from the same two articles, which both reproduce a letter signed by a large number of Muslim Labour councillors, asking the leader of the Labour Party, Keir Starmer, to call for a ceasefire in Gaza. These articles are unusual in that as well as printing the 461-word letter, they also list all of the signatories and their positions, amounting to a further 1,089 words. The publication of the letter thus represents the Labour Party leadership (which was not supported by the Daily Mail) as being in conflict with a large number of Muslim leaders in the UK. We also found during our examination of concordance lines of Gaza and Israel that there were a significant number of references to divisions in the Labour Party involving its stance on the conflict.

Friday stands out as an unusual Daily Mail keyword, as it is the only word in Table 3 which refers to a day of the week. Friday occupies a special place in Islam as it is when a community prayer service is held. The Daily Mail appears to mark cases where protests or other conflicts occur on Fridays:

In the Iranian capital Tehran, hundreds of people marched after Friday prayers during which they burned a Swedish flag.

It is difficult to confidently interpret the significance of the Daily Mail’s use of Friday in such stories, although one possibility is that the intention is to highlight a contrast between the scenes of conflict being described and the fact that they are marked as occurring on a holy day when Muslims carry out one of the most exalted Islamic rituals. The Daily Mail keyword students tends to relate to reports of conflicts at universities involving Muslim students, who are often characterised as taking unreasonable offence, for example:

Muslim students force Minnesota college to close Iranian American artist’s exhibition.

The Daily Mail’s keywords therefore give a mixed picture, representing Islam through a lens of conflict and grievance, while quoting voices who show support for Muslims in Gaza.

Finally, we note the Daily Mail keyword Koran, which is sometimes used to refer to the Qur’an. The Centre for Media Monitoring recommends using Quran or Qur’an, noting that Koran is seen by Muslims as incorrect.Footnote 4 Across the corpus, there is considerable difference in how this word is spelled, as Table 4 indicates. The Daily Mail favours Koran over the other two forms more than any other newspaper (although the Telegraph also shows a weaker preference for Koran). Most of the references to Koran in the Daily Mail relate to protests where it was burnt, kicked or stood on – actions that are seen as blasphemous in Islam. Numerous reports focus on reactions from Muslims at such demonstrations, for example:

demonstrations have raged across the Islamic world after the nordic countries allowed the burning of the Koran under rules protecting free speech.

Such articles describe rather than denounce the attack on Islam and tend to instead focus on Muslims as angry about it.

Table 4 Frequencies of Koran, Quran and Qur’an across the newspapers

| Koran | Quran | Qur’an | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Mail | 105 | 12 | 3 |

| Daily Star | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| The Express | 7 | 35 | 2 |

| The Guardian | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| The Independent | 7 | 173 | 0 |

| The Mirror | 3 | 23 | 6 |

| The Sun | 8 | 6 | 2 |

| The Telegraph | 77 | 17 | 1 |

| The Times | 5 | 60 | 0 |

The Daily Star has three keywords that are pronouns – I, she and her – indicating perhaps more focus on stories about women, as well as those involving a personal perspective. Closer examination of two proper noun keywords, Knoll and Mia, provides further information about the women who are most saliently represented in the newspaper. Knoll refers to the erotic photography model and former Miss Croatia, Ivana Knoll, who is the topic of 11 Daily Star articles about her presence at the 2022 World Cup, which was hosted in Qatar, a Muslim-majority country which has a dress code for women. Knoll is described as having sunbathed naked in Qatar and is quoted as saying:

‘I’m not a Muslim and if we in Europe respect hijab and niqab, I think they need also to respect our way of life, our religion and in the end me wearing dresses, bikinis because I’m Catholic from Croatia who is here because of the World Cup.’

Another Daily Star keyword, Mia, refers to Mia Khalifa, a British Pakistani who is an adult film star. Described as being brought up in a ‘strict Muslim household’ and no longer a practising Muslim, she is reported in the articles for having almost been banned from the social media platform Instagram for posting an almost-nude photograph of herself, and how she caused controversy by launching a new jewellery line called Sheytan, which translates to ‘devil’ in Arabic. Both sets of stories deal with young women who are seen as challenging gendered expectations in Islam through sexualised bodily displays. The articles aren’t explicitly critical of Islam, but in terms of perspectivation they foreground the actions and views of Knoll and Khalifa, who are represented as being in conflict with Islam, through detailed descriptions of the two women, along with lengthy quotes from them.

In the Express, the keywords pro and Palestine tend to occur together, referring to pro-Palestine marches and demonstrations that occurred across cities in the UK. Coverage of the marches tends not to be positive, with marchers being referred to as ‘a mob’ or as ‘leftie’, along with reports that people at the marches chanted ‘jihad’ (also an Express keyword) and that they held placards showing British and Israeli leaders with Hitler moustaches. There are also reports that one of the marches would take place on Remembrance Sunday, a day which commemorates members of the armed forces who died in World War I and all wars since, with the newspaper reporting concerns that the event would be disrupted by pro-Palestine demonstrations.

The Express refers to the public broadcaster the BBC and the London Metropolitan Police (both BBC and Met are keywords), quoting people who claim that the two institutions are biased towards Muslims and Palestine:

Ex-BBC boss warns ‘biased’ broadcaster’s Israel reporting is ‘danger to British Jews’.

Rishi Sunak blasts Met Police for not acting on ‘jihad’ chants.

Finally, the Express carries several articles about Labour Party leader, Sir Keir Starmer, which characterise him as coming into conflict with Muslims:

Sir Keir was criticised for his refusal to call for a full ceasefire and his apparent support for blocking power and water supplies to Gaza.

By representing the Labour Party and Muslims as being in conflict with one another, the Express can further create negative associations of two of its targets at the same time, much as the Daily Mail achieved by reporting on Labour’s position on Gaza being different to that of Muslim councillors.

Three of the Guardian’s keywords tend to be linked to stories relating to the government’s policy on extremism: Prevent, rightwing and review. Prevent is the government’s counter-extremism programme, and the Guardian reports on a review of it which came out in 2023. The Guardian evaluates the review as ‘controversial’, ‘ill-starred’ and ‘much-delayed’ and prints quotes from people who are critical of it, for example:

Britain’s former top counter-terrorism officer has said parts of the government-backed review of Prevent appear to be driven by a rightwing ideology.

Here, then, the Guardian represents Islam as unfairly singled out as a terrorist threat. Three other Guardian keywords, Charles, coronation and royal, refer to the coronation of King Charles III, which occurred on 6 May 2023. Although the articles in the Guardian question the relevance of the royal family and the expense it incurs to the UK, as well as mentioning anti-monarchy protests which coincided with the coronation, the newspaper also refers to the fact that this was the first coronation where representatives of different faiths were involved:

One innovation is a greeting to the king to be delivered in unison by Jewish, Hindu, Sikh and Muslim representatives at the end of the service.

On 30 April 2024, a Muslim MP, Shabana Mahmood, is reported as saying that she ‘had already sworn allegiance to the king on the Qur’an and would be “joining in at the weekend as well”’. While the Guardian presents a somewhat anti-monarchist stance, it uses its reporting around the coronation to represent Muslims and members of other faiths as integrated and supportive of a key aspect of British society.

The Independent’s keywords appear to be more clearly focused on Islam than some of the other newspapers: Muslim, Muslims, Quran, religious, pilgrims and Hajj. These keywords occur in articles which provide readers with information about aspects of Islam. For example, Hajj and pilgrimage appear in an article entitled ‘“Hajj is not Mecca”: Why prayers at Mount Arafat are the spiritual peak of Islamic pilgrimage’. Questions in these kinds of articles frame readers as interested in knowing about the Hajj, for example:

What is the Hajj pilgrimage and what does it mean for Muslims?

Additionally, there is an implicature that the information provided in other articles is there because it is unlikely to be known by readers, for instance:

All able-bodied adults of the Islamic faith are expected to complete Hajj at least once in their lifetimes.

Another Independent keyword, hate, occurs 47% of the time (94 times) as part of the phrase hate crime(s), while 85 out of 100 cases of hate taken at random refer to incidents where Muslims have been targeted, with articles referring particularly to cases of Islamophobia as a result of the conflict between Israel and Hamas. One headline reads:

Viral hate and misinformation amid Israel–Hamas crisis renew fears of real-world violence.

There are also references to incidents where demonstrators publicly burned copies of the Quran (an Independent keyword which, as seen earlier, is a preferred spelling by Muslim groups). Unlike the Daily Mail, which uses the dispreferred spelling, Koran (see Table 4), the Independent does not foreground anger of Muslims in these articles, instead referring 18 times to the burnings as desecrations (a term the Daily Mail uses just four times). The Independent therefore represents Muslims as engaged in religious observance, as well as being targeted for their religion.

Two of the Mirror’s keywords are forms of the second-person pronoun (you, your). A concordance-line analysis of 100 cases of these words taken at random found that seven cases involved a direct address to the reader (e.g. ‘Do you have a story to share?’) while 19 cases involved someone being quoted while addressing another person (e.g. ‘I’m scared you are going to hurt me’). However, the majority of cases (74) involved you being used as a generic, described by Pearce (Reference Pearce2001: 201) as a way of indicating commonality of experience (e.g. ‘There are times in your life when you will be short of things and you have to accept what is happening’). We found that 52 of the 74 cases of generic you (72%) were used in articles which were written by Muslims and provided information about aspects of the religion. This also helps to explain the presence of other Mirror keywords Ramadan, Eid and calendar, which are similarly used in articles that provide explanations around the ninth month in the Islamic calendar, which involves fasting and is viewed as one of the five pillars of Islam. On the one hand, these articles provide an informative, non-judgemental and non-political perspective on Islam. Many of these articles appear to be written for non-Muslims, using the second-person pronoun to discursively exclude the possibility of a Muslim reader (something which was less common in the Independent’s articles which also provided information about Islam). For example, one article is entitled ‘How to support your Muslim colleagues and friends during Ramadan’, offering advice like ‘give your colleagues time to pray’, ‘don’t worry about eating secretly’ and ‘don’t ask why someone isn’t fasting’. Another notes,

In a bid to support Muslim friends throughout Ramadan, you may be observing a fast yourself or celebrating Iftah with them, but another way you can show appreciation and care for Muslims throughout the month is by educating yourself on their culture.

The 2021 national census identified 6.5% of the UK population as being Muslims, so these articles comprise an odd mixture of excluding Muslim readers while representing their culture positively.

Not all of the Mirror articles about Ramadan presuppose a non-Muslim reader. For example, an article entitled ‘Ramadan: How to manage medications and health tests during the holy month’ provides advice from a pharmacist called Ifti Khan, who is described as working at Well Pharmacy. Another article is entitled ‘Best Ramadan chocolate advent calendars 2023 – from Amazon, Asda, and more’. The article goes on to list different kinds of calendars that are available and is written in the style of an advertorial. Therefore, these articles indicate how a positive stance towards Islam is interdiscursively linked to marketing discourse.

The Sun’s keywords tend to relate to war and terrorism, examples being cops, rocket, IDF, hostages, released, Hamas and hospital. Cops tends to be used to refer to suspected terror attacks carried out by Muslims. Hamas and IDF (Israel Defense Forces) relate to the Israel–Hamas conflict, as does rocket, which in 100 out of 100 random cases refers to rockets that were fired by those on the side of Hamas. One of the most commonly mentioned incidents involves a rocket that is described as having hit a hospital in Gaza (explaining why hospital is a keyword). However, this is described as being a ‘failed rocket launch’ by Islamic Jihad, and other Sun articles claim that Palestinians used the attack as propaganda, such as:

Satellite reveals MINIMAL damage to hospital where Hamas claims Israel ‘killed 500’ … after ‘proof’ it was a terror rocket.

The Sun discusses the Israeli hostages who are held by Hamas in Gaza, reporting on cases where they have been released, with particular focus on those who are vulnerable. For instance:

At the moment they are the youngest hostages still remaining in Hamas captivity.

Hostages have been seen in wheelchairs and with bandages on.

Finally, the keyword mum (as well as the pronoun her) tends to relate to dramatic stories, usually involving crime, about mothers who are Muslims. These stories can involve mothers as victims, as being related to terrorists or as a bad parent, as demonstrated in the following three examples:

A neighbour has admitting killing a mum and her two children in a house fire.

The school dropout was reported to the Prevent counter-terrorism programme by his mum, who had noticed a change in his behaviour.

The mum, who converted to Islam as an adult, would allegedly report the children’s ‘bad’ behaviour to her husband when he came home from work.

The Sun’s keywords generally paint a negative picture of Islam, implying that it is linked to war, terror and crime.

Three of the Telegraph’s keywords relate to Iran (Iran, Iranian and Iran’s), while another keyword, regime, collocates 25 times with these words. Iran is represented very negatively in the Telegraph, being described with adjectives like ‘aggressive’, ‘brutal’, ‘cancerous’, ‘decrepit’, ‘extremist’, ‘fanatical’ and ‘hostile’. In terms of carrying out actions, the Telegraph describes Iran as financing terrorism, suppressing women, carrying out executions and creating propaganda. There are eight references in the Telegraph to ‘the Islamic Republic of Iran’, and one article reports the closure of an ‘Islamic centre in London that praised Iran terror general’. An opinion column accuses Iran of spreading conspiracy stories about Jewish people, asking:

I might inquire of the Muslims who accept such stories: is Iran your idea of a worthy Islamic state?