1. Introduction

The purpose of this article is to explore the representation of electric guitarists on Instagram. It will examine the ways in which the practices of various women electric guitarists are represented – the nature and frequency of their posts featuring performances, skills and tips, and related aspects such as equipment. It will also survey the representation of their self-images – the ways in which gender roles and gender expression are represented and the extent to which they draw on or reject stereotypical norms and expectations related to beauty and femininity. The analysis will also consider the interconnectedness between these representations and their significance. The findings in this article are based on textual analysis of the social media content of sixteen electric guitarists of varying ages, success levels, and career stages.

In the interest of clarity, it is necessary to define the terms that frame the subjects of this study. This article follows Mary Celeste Kearney (Reference Kearney2017) in her statements about and approach to the study of gender and popular music. At the most fundamental, ‘gender’ is defined as a ‘social system’ (Kearney Reference Kearney2017, p. xvi) that ascribes meaning to all bodies (p. xx) and is ‘socially constructed and contested in numerous sites in rock culture rather than inherent in individual bodies, objects, practices, or institutions’ (p. xviii). Further, it takes the position that ‘“gender” is not equivalent to “women”’ (p. xx) and works to recognise the various gender discourses within rock and popular music culture (p. xix). The view taken throughout this article is inclusive and accounts for diversity: the experiences of women and women-identifying, non-binary, gender non-conforming, and transgender individuals, as well as people of diverse sexual orientations. At times, particularly in discussions of existing literature on gender and the electric guitar, this article does use the term ‘women’. The use of the term is due to ‘women’ being the subject and operative word in those studies. The term ‘guitarist’ refers to someone who plays the guitar as a primary component of their musical practice. They may play lead or rhythm guitar. This study covers electric guitarists in particular, though these musicians may also play acoustic guitar.

This article will demonstrate that Instagram is an important site of analysis in its ability to contribute to shaping the discourses around electric guitarists and the normalisation of diverse identities in this role. It will do so by situating the analysis of these social media representations in relation to existing scholarly literature on women and the electric guitar and in view of the nature of the dominant discourses and representations that have shaped the understanding of electric guitarists. The research findings presented here will show that Instagram is a platform through which a multiplicity of representations of electric guitarists – in terms of musical practice and gender expression – can be observed. In doing so, it will illuminate that representations on Instagram reveal tensions in existing research, particularly in relation to the intersection of femininity and the instrument. These findings provide further support for a more balanced and inclusive approach to the study of gender within popular music studies. These factors can contribute to a deeper, more nuanced understanding and expand the narrative about gender and the electric guitar.

This article begins with a short overview of the existing literature about women and the electric guitar and introduces the role and significance of the internet and social media in relation to electric guitar practice and representations of gender. It then outlines the approach and methodology utilised in this study. From there, this article examines the Instagram content of the sixteen electric guitarists in the research sample. The presentation of findings and analysis is organised first by the representation of electric guitar practice, which includes the categories of live performance, performances of songs recorded specifically for social media, promotion, and working. Second, it examines self-representation and femininity along with the interconnectedness between these two areas of representation. The analysis considers the significance of representation on Instagram in relation to existing research and the longer history of gender and the electric guitar. This article will then move to a conclusion and summary.

2. Women and the electric guitar: Discourse, barriers, and the possibilities of the internet

It is well established in the academic literature and can be easily observed in the media and the music press, that men have been the dominant and expected figures aligned with the electric guitar and that the instrument has been commonly associated with masculinity and male sexuality (Bayton Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997; Bourdage Reference Bourdage2010; Herbst and Menze Reference Herbst and Menze2021; Waksman Reference Waksman2001a) throughout the history of rock and popular music. The physical shape of the instrument has been described as being designed for and an extension of the male body (Bayton Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997, pp. 43–44; Carson et al. Reference Carson, Lewis and Shaw2004, p. 11; Crespo Reference Crespo2010; Herbst and Menze Reference Herbst and Menze2021, pp. 71–72; Waksman Reference Waksman2001a; Vesey Reference Vesey2020). In contrast, women have historically been marginalised and overlooked as electric guitarists and have struggled to be taken seriously (Bayton Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997; Bourdage Reference Bourdage2010; Carson et al. Reference Carson, Lewis and Shaw2004; Kearney Reference Kearney2017; Leonard Reference Leonard2017 [2007]).

The literature on women and the electric guitar is small but important and has addressed a variety of topics and issues (Fourie Reference Fourie2020; Kelly Reference Kelly2009; Lewis Reference Lewis2018; Matabane Reference Matabane2014). Most of the research was conducted prior to the proliferation of the internet and social media or did not consider it in any depth. For the purposes of this article, only the most relevant aspects will be addressed here to provide context for and situate the research findings. Gender has been shown to shape women’s experiences as electric guitarists – or prevent it – through the expectations and pressures associated with femininity. Bayton (Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997) and Bourdage (Reference Bourdage2010) identified social expectations around femininity as among the barriers women encounter in becoming electric guitarists. Among them are norms and expectations around traditional femininity and coupling, time constraints related to motherhood, the aforementioned masculine association of the electric guitar and technology more generally, and a relative absence of female role models (Bayton Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997; Bourdage Reference Bourdage2010).

Further, due to these norms, expectations, and associated pressures, these scholars state that women who play the electric guitar effectively break the gender code due to its masculine association. However, one of the limitations of this view is that it can represent a normative and binary view of gender and associated roles and expectations and can be seen to assume that women musicians want to adhere to them. Though this may be accurate at times, such a perspective takes normative understandings of femininity for granted without accounting for diversity in terms of gender expression. Some women electric guitarists may distance themselves from such expectations or have diverse gender expressions. While research has begun to show the ways in which women challenge or ‘subvert […] gendered stereotypes and expectations of guitarists’, it remains a minimally explored area (Rogerson-Berry Reference Rogerson-Berry2020, p. 1; cf. also Vesey Reference Vesey2020). In contrast, women who have rejected norms and expectations are often dismissed as trying to ‘be one of the boys’ or attempting to emulate men (see, e.g., Clawson Reference Clawson1999; Davies Reference Davies2001). Such statements are made in response to women’s more masculine performance style, clothing style, or attitude. These critiques have been made without accounting for the intricacies of these women’s identities. They also suggest that women musicians consistently struggle to avoid being undermined or marginalised whether they adhere to the expectations of gender or not. This sets up a seemingly irreconcilable situation in which women musicians consistently encounter criticism on the basis of gender regardless of how they choose to express their gender.

Women electric guitarists have also long been subject to either problematic representation or underrepresentation in the music press and media (Fincher Reference Fincher2024; see also Davies Reference Davies2001; Dibben Reference Dibben1999) and have faced pressure to maintain particular standards. Women musicians’ physical appearance took greater centrality with the advent of MTV. The video content broadcast on the network ‘gave a new spin to the looks of performers, who up to then had primarily been voices on the radio and, occasionally, concert artists’ (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Lewis and Shaw2004, p. 116). MTV created ‘new ways’ of packaging and marketing women’s physical beauty and image ‘became everything […] in the eyes of the music industry’ (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Lewis and Shaw2004, p. 127). Due to the ways in which appearance is so interconnected with gender for women, they are ‘constrained, penalised, or rewarded based on their approximations of culturally appropriate standards of beauty’ and are evaluated on the basis of what they wear and look like ‘rather than the quality of their music’ (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Lewis and Shaw2004, p. 134). Such an emphasis is another way in which women’s musical contributions are positioned in a secondary role.

There has been quite a bit of attention to advertisements and visual representation. This is due to the long history of highly problematic representation of women in the music and guitar press, and technology-related magazines more generally (Berkers and Eeckelaer Reference Berkers and Eeckelaer2014; Davies Reference Davies2001; Dibben Reference Dibben1999; Leonard Reference Leonard2017 [2007]; Théberge Reference Théberge1997). A common practice in guitar and technology magazines was to feature women as models for equipment rather than including coverage of them in their roles as musicians or producers. A significant shift occurred in 2016 when Guitar World decided to end the publication of its gear guide, which was one such example of women being portrayed as sexualised models rather than as musicians. A year prior, in 2015, a social media post featured the cover of Guitar World’s gear guide next to a cover of She Shreds, a magazine created for and directed to women musicians, which went viral. She Shreds stated in a blog post that the ‘juxtaposition was a wake-up call to both media consumers and companies about the reality of our presence. Women are musicians, and we deserve to be represented as such’ (Reyna Reference Reyna2016, n.p.). In 2016, Guitar World’s publisher announced they would do away with the bikini models, stating they were ‘outdated’, that they ‘didn’t want to associate the brand with what could easily be viewed as sexist’, as a ‘misrepresentation of women guitar players, or that women in general, may find offensive’, and they stated they wanted to support women readers and create content that attracts them (Reyna Reference Reyna2016, n.p.).

It is significant that this decision was the result of a social media post. Social media, and the internet more broadly, is a somewhat contested space for women musicians. It was once seen for its utopian possibilities and has been found to be the site of the reproduction of off-line social issues (e.g., Berkers and Schaap Reference Berkers and Schaap2015). However, the internet has been effective in creating greater visibility, generating exposure and establishing credibility for women electric guitarists in a historically male-dominated field. It has also been found to be a significant space for women electric guitarists to acquire skills (Crespo Reference Crespo2010) and build communities.

3. Examining representations: Approach and methodology

Several research questions formed the basis for the study and analysis: How do women electric guitarists represent their practice as instrumentalists? How do they represent themselves and their own identities? To what extent do these images draw on the norms and expectations related to beauty and femininity? To what extent does the nature of self-representation distract from understanding these individuals as guitarists? (Choi Reference Choi2017, p. 476).

This study examines the Instagram content posted by women electric guitarists. The choice of Instagram as the site of analysis was due to it being a ‘visually driven’ platform through which musicians can ‘represent their identities and communicate their experiences’ (Tofoletti and Thorpe Reference Tofoletti and Thorpe2018, p. 20). As its point of departure, this study draws on existing research on the significance of online spaces and the role of social media in specifically gendered representations. Instagram—and the images and videos posted to the platform—can, on the one hand, be a ‘tool for reinforcing women’s agency’ or for ‘reinforcing and reproducing existing social norms’ (Caldeira et al. Reference Caldeira, De Ridder and Van Bauwel2018, p. 26). Among the ‘technologies of gender’, representations on Instagram ‘produce and reproduce specific gender conceptions that are linked to broader sociocultural discourses’ (Caldeira et al. Reference Caldeira, De Ridder and Van Bauwel2018, p. 27, in reference to de Lauretis Reference De Lauretis1987, pp. 18–19). Specifically, in the context of music, Instagram can ‘reaffirm women’s stereotypical image as sexual objects and distract others from knowing about these women as musicians’ (Choi Reference Choi2017, p. 476).

It is important to offer some reflection here on the research questions and approach. Initially, this study intended to focus on norms, expectations, and stereotypes related to beauty and femininity. However, the findings that emerged revealed that the more significant considerations had less to do with stereotypical norms and expectations and more to do with the diversity of representation. While these considerations are part of the study, an approach that solely focuses on asking questions about beauty, traditional femininity, and stereotypes also comes with the risk of overlooking different perspectives. This suggested that an analysis centred on gender stereotypes would not capture the most significant aspect of these social media accounts.

Social media is also an essential area of investigation in popular music studies as it has altered and shaped the dynamic between musicians and their audiences with expectations for the former to be more accessible by offering greater visibility of their careers and everyday lives (Baym Reference Baym2018). In these ways, Instagram is an important site for analysis in its ability to contribute to shaping the discourses around women electric guitarists and their normalisation in this role.

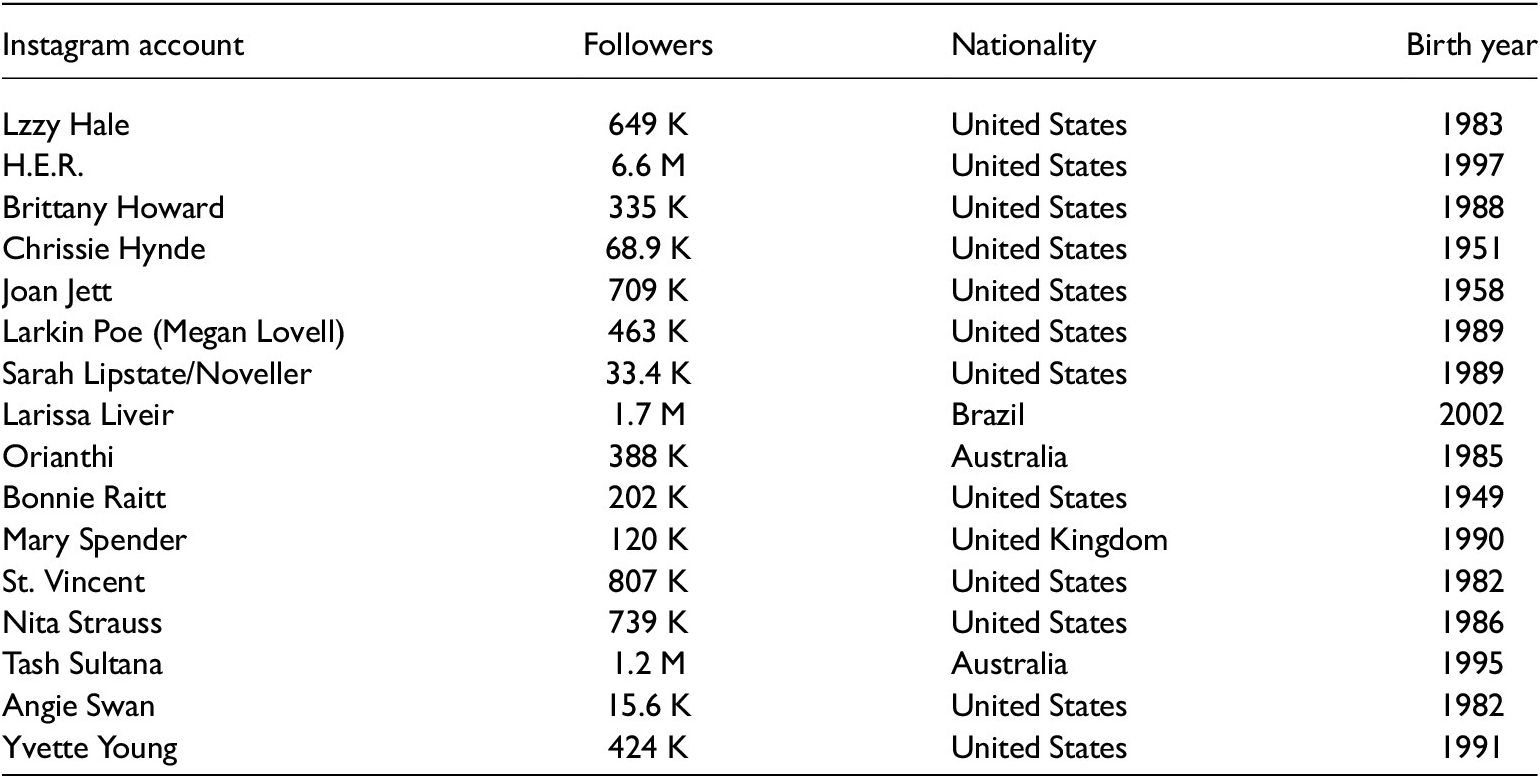

The study was based on the Instagram content of a sample of sixteen electric guitarists. The cases represent a selection of the most recognisable electric guitarists from the 1970s to the present. Table 1 provides an overview of the cases in the sample.

Table 1. Instagram accounts analysed in this study (February 2025)

The sample was designed to account for variations in career length, age, and relative success. As this study focuses specifically on online representation, it was important to examine a group of guitarists with different experiences in establishing their careers. That is, whether they made their names through online platforms or through more traditional conventions such as acquiring a record deal and attendant forms of industry support and promotion. This selection of cases aimed to provide insights into the patterns and characteristics of online use in view of generational and career-related similarities and differences. The extent to which these particular Instagram accounts featured guitar practice and the nature of self-representation was not known in advance, and the selection of cases came with the possibility that some musicians may not post content relevant to this study. In this way, variation and inconsistency in the frequency and nature of the posts are useful in themselves, as they demonstrate a range of preferences among women electric guitarists regarding applicable social media usage.

The names of the musicians associated with these Instagram accounts are named in this study. The social media accounts of musicians are largely informational and promotional and can be deemed ‘intentionally public’ (UK Research and Innovation 2025). As public figures, they can be understood to be ‘seeking to share their data as widely as possible’ and may be considered exceptions regarding anonymity (Townsend and Wallace Reference Townsend and Wallace2016, p. 13). This decision follows other research on Instagram and social media (Caldeira et al. Reference Caldeira, De Ridder and Van Bauwel2018; Roberti Reference Roberti2022; Tofoletti and Thorpe Reference Tofoletti and Thorpe2018) about influencers, well-known or high-profile individuals in which the names are identified. In this study as well as in the others, who the people are is directly relevant to the research objectives. The practices and identities of electric guitarists, individually and collectively, shape the understanding of their positioning within and contributions to popular music history and culture. Anonymising these accounts would also dilute the meaning and significance of some of the content of the Instagram posts, as will be evident in the analysis. The intent of this study and analysis is in no way to criticise, judge, or question the ways in which women electric guitarists represent themselves or their musical practices on Instagram. Rather, it is to demonstrate the diversity among musicians and its significance in understanding the electric guitar and its relation to gender.

Starting in the spring of 2024, Instagram content from the preceding two years was reviewed for each guitarist, including images and videos. Posts specifically related to electric guitar practice and self-representation were identified for closer examination. In some cases, there were limitations related to the number of available posts, as guitarists did not maintain all previous posts and apparently deleted older posts. The content of the images and videos was analysed using textual analysis, a method that ‘involves understanding language, symbols, and/or pictures present in texts to gain information regarding how people make sense of and communicate life and life experiences’ (Hawkins Reference Hawkins and Allen2017, p. 1754). The content of texts is generally ‘understood as influenced by and reflective of larger social structures’ (Hawkins Reference Hawkins and Allen2017, p. 1754). Textual analysis is a means of gaining an understanding of the ways in which electric guitarists ‘make sense of who they are, and of how they fit into the world in which they live’ (McKee Reference McKee2003, p. 1). In the research process, the ways in which these musicians represent their practice as electric guitarists on the platform were first explored. The analysis looked at the types of activities that musicians engage in related to the electric guitar – that is, the nature and frequency of their posts that feature performances, skills and tips, and related aspects such as equipment – and identified themes based on them. In addition, the number of posts related to electric guitar practice was accounted for. Second, the study surveyed the representation of self-image. In looking at the manner in which guitarists represent themselves, the analysis considered the extent to which photos and videos that were focused on the guitarists’ self-images were featured over the 2-year time frame, how these images could be understood in terms of gender expression and the extent to which they draw on – or reject – stereotypical norms and expectations related to beauty and femininity. The purpose of the images (e.g., promotion) and the ways in which the images highlighted specific qualities of the particular musicians’ personas and careers were also analysed. Third, the analysis considered the interconnectedness between the representations of electric guitar practice and self-image. Collectively, the goal was to locate patterns of electric guitar practice and understand what social media self-representation demonstrates about guitar playing and femininity broadly and about the significance of individual musicians more specifically.

4. The representation of women’s electric guitar practice

It is first necessary to highlight the range of electric guitarists featured in this sample. The sample is comprised of variations in style, technique, and musical expression. The majority of musicians play lead guitar (e.g., Brittany Howard and Nita Strauss) and utilise virtuosity (e.g., Orianthi and Yvette Young), while the rest of the sample is constituted by rhythm guitarists (e.g., Chrissie Hynde and Joan Jett), as well as lap steel (Megan Lovell) and slide guitarists (Bonnie Raitt). The sample also represents great diversity in terms of age. At the time the research was conducted, the age range varied from 21 (Larissa Liveir) to 74 (Bonnie Raitt). Within this group, there are musicians who built careers prior to the proliferation of the internet and others who came of age with social media and utilised it extensively for promotion and to establish themselves. Several guitarists are considered ‘pioneers’ who paved the way for others, and some are perceived as among the contemporary innovators of the instrument. Taken together, this multigenerational representation is indicative of the consistent presence of diversity in terms of gender expression among electric guitarists throughout rock and popular music history.

Turning to the content of Instagram accounts, the number of posts that these electric guitarists made in a 2-year time frame varied substantially. Some guitarists were highly active and posted frequently; others engaged much less. The lowest number of posts was 30, and the highest was upwards of 1,500. The average was 294. The frequency of posts does not seem to correlate with generational differences and perceived norms of social media activity. Across the sixteen Instagram accounts, the presence of content related to the electric guitar was not consistent. Not all musicians strongly feature the electric guitar or instrumental practice, though all of them include some related content. On the low end, the percentage of posts that featured the electric guitar was 3% and the highest was 94%. The average across all sixteen musicians was 33% or approximately one-third of the content. This number should be contextualised with the view that musicians engage in a variety of musical and professional activities, of which playing guitar is only one part.

It is important to highlight possible limitations in terms of data. These statistics are limited by inconsistencies in the number of posts per account and the 2-year time frame for analysis. More significantly, the nature of the posts may be subject to these musicians’ particular career activities occurring during the time – or are the product of a potential period of inactivity. Instagram posts also do not highlight intent, and interviews would provide more insight into the use and perception of social media for guitarists.

It is of note that several musicians who are strongly aligned with the guitar, such as St. Vincent and H.E.R., and those who largely established themselves as guitarists in an online context, such as Mary Spender, post guitar-related content on Instagram the least frequently of the sample. This factor could suggest that more established electric guitarists may not feel the same need or pressure to promote this aspect of their careers at this stage. The fact that these musicians maintain a strong association as electric guitarists without continuous representation on social media is also indicative of the establishment of their credibility and contributions. The research conducted for these sixteen Instagram accounts identified several patterns of representations of electric guitar practice. The patterns are live performance, performances of songs recorded specifically for social media, promotion, and working in other musical capacities. Each will be discussed individually here.

4.1. Live performance

A major aspect of the representation of electric guitar practice is images and videos of live performances at concerts. Photos of electric guitarists playing the instrument live onstage are a feature of all sixteen Instagram accounts comprising the sample in this study. These musicians highlight a range of performance clips – and therefore individual skills and techniques – associated with their practice and identities as electric guitarists. For example, Brittany Howard posted a video from the Coachella festival in 2024 during which she played a guitar solo and then altered the tunings of the strings at the song’s closing. In the post, Howard added the text ‘Shredchella’ to characterise the event in direct relation to her performance technique on the guitar (Howard Reference Howard2024a). She similarly posted a video of a ‘Glast-O-shred’ following her performance at the festival (Howard Reference Howard2024b). Joan Jett posted a clip of her playing ‘Do You Want to Touch Me’ onstage with a multi-split screen that emphasised her rhythm style and sound (Jett Reference Jett2024).

Live performance videos also highlight the passion, enthusiasm, and joy associated with playing the guitar. Tash Sultana posted a clip of a live performance in which they are seen jumping across parts of the stage and performance space while soloing (Sultana Reference Sultana2024a). They then move to the barrier to perform directly with the crowd, who cheer and pat them on the back as Sultana closes their eyes and moves to the beat. In the latter two instances, these posts had the dual function of also promoting a forthcoming tour. In Jett’s case, the post functioned as a countdown until the start of the tour. For Sultana, it was an announcement that they would be performing live again and a means to provide information to followers so that they would not miss out. The central positioning of the guitar in relation to generating excitement about high-profile events and anticipation about upcoming live performances positions the instrument as an essential component of these musicians’ musical identities and appeal.

Another prominent aspect of the representation of live performance is photos of the electric guitarist with respective band members or collaborators during concerts. For example, Angie Swan features photos of her playing guitar onstage with David Byrne, with whom she toured extensively (Swan Reference Swan2023). Chrissie Hynde posted images of her and Johnny Marr playing guitar onstage with The Pretenders at the Isle of Wight festival (Hynde Reference Hynde2024). Marr had briefly been in the band in the late 1980s and made a guest appearance at the Glastonbury Festival in 2023. These live collaborations indicate the reach of these musicians’ musical contributions and function as a form of validation and credibility. For Swan, one photo in particular depicts her with her head back in the midst of a solo with Byrne appearing to cheer her on and positions her as the central musical figure. For Hynde, such collaboration illuminates her status as a bandleader and rock icon with influence and the ability to invite high-profile guests to her stage. Such posts are consistent with and emblematic of the significance of live music to musicians’ careers as both remuneration and promotion and as an indicator of authenticity (Auslander Reference Auslander2008; Black et al. Reference Black, Fox and Kochanowski2007; Laing and Shepherd Reference Laing, Shepherd, Shepherd, Horn, Laing, Oliver and Wicke2003, p. 567).

4.2. Performances of songs recorded specifically for social media

Aside from live performances that are filmed in the context of a concert event, Instagram accounts also feature performances of songs on the guitar that are custom-made for the purpose of dissemination on social media. These types of posts include filmed performances of both cover versions and original pieces of music. One guitarist, Larissa Liveir, whose Instagram features the highest percentage of guitar-centric content from this sample, makes such performances the focus of her entire account. She is typically seen sitting on a chair or sofa and plays a different song, usually a cover, in each post. In the text of the post, she also includes the type of guitar she plays and the amplifier. In some cases, these types of posts feature an interactive component that functions to foster engagement with followers. In another example, Megan Lovell of Larkin Poe performed a cover of Sting’s ‘Fields of Gold’ on lap steel (Larkin Poe 2024). Over the video, the question ‘True or false: everybody knows this song’ was written in an effort to generate a response and interaction with followers.

Instagram content from this sample also features guitar performances that highlight the guitarist’s use of and appreciation for particular types of gear. Yvette Young posted a video in which she demonstrates how she wrote a loop using a Line 6 HX (Young Reference Young2023). The video features a split screen that showcases both her guitar playing and her feet controlling the pedal. In the text, she provides specific details about the attributes of the pedal that she particularly prefers, how it helped her to achieve her sound, and expressed enthusiasm for and enjoyment of using this pedal. Existing research has overwhelmingly shown how the masculinisation and male dominance of technology have functioned as a barrier to women becoming electric guitarists. Previous work has also shown a pattern of technophobia among women electric guitarists, including those who had been playing for many years (Bayton Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997, p. 42; Herbst and Menze Reference Herbst and Menze2021, pp. 64–65) and among women in higher education music technology courses more generally (Born and Devine Reference Born and Devine2015). Scholars (Bayton Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997; Bourdage Reference Bourdage2010) have argued that masculinity is linked to competence and confidence with technology, while femininity is marked by incompetence. This argument is based on the ways in which ‘women are often alienated from the essential technical aspects of rock’ (Bayton Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997, p. 42). Young’s demonstration in this video is useful for highlighting her confidence in using music technologies and positioning her as competent with technology. This is enhanced by the way in which the thoughtful arrangement of Young’s video can also serve as a form of instruction for others interested in similar practices. Further, it allows followers to know Young as a musician. As Herbst and Menze (Reference Herbst and Menze2021, p. 98) have noted, gear choice functions as a ‘badge of identity’. Equipment has been shown to be ‘more than just a tool for making music’ (Herbst and Menze Reference Herbst and Menze2021, p. 97). Rather, it is a significant component of musicians’ ‘self-image […] and thus part of their musical identity’ (Hargreaves et al. Reference Hargreaves, MacDonald, Miell, Hallam, Cross and Thaut2016; Herbst and Menze Reference Herbst and Menze2021, p. 97; North and Hargreaves Reference North and Hargreaves1999).

All of these videos demonstrate a range of skillsets from these guitarists, from arranging and performing cover versions to utilising technology to enhance musical composition. In being deliberately designed for social media activity and engagement, they reinforce these musicians’ agency, generate more visibility of their abilities, and highlight competence in the use of the guitar and technology.

4.3. Promotion

This article has shown that publicising concert tours is a feature of the Instagram content of the electric guitarists in this sample. This section will discuss the use of Instagram to promote other aspects of their careers, such as the release of signature guitars, public appearances, and events. A signature guitar is a special-edition guitar featuring the name of a particular high-profile, established artist that is designed according to particular specifications, technical design, sound, and look. These guitars are created based on a collaboration between an artist and a specific guitar company, such as Gibson or Fender. Signature guitars place importance on the musician, the design of the instrument, and its technical specifications, as well as its meaning in music culture. The most important aspect of a signature model is the recognition and status that artists receive – a signature guitar is a symbol of legitimacy. Waksman (Reference Waksman, Bennett and Dawe2001b, p. 125) has stated that the signature guitar is ‘perhaps the ultimate prestige’. Several guitarists in the research sample have had signature guitars released (though the promotional periods for several were outside the time frame of this study), including Bonnie Raitt (the first woman to receive one in 1986), Chrissie Hynde, Yvette Young, Nita Strauss, St. Vincent, Orianthi, and Tash Sultana.

Guitarist H.E.R., who has two signature guitars, used the platform to promote the release of the second one, called the Fender Limited Edition H.E.R. Signature Stratocaster Electric Guitar in Blue Marlin. In a post that featured five images and a video, she highlighted the key physical aspects of the signature guitar, her nameplate on the back of the instrument and representations of herself playing the guitar (H.E.R. 2023). An exuberant text alongside the images expressed the meaning the guitar held for her and her excitement about its release. The visibility of these signature guitars on Instagram is important not only as a promotion for a singular artist but also due to how women and gender-diverse individuals are significantly underrepresented in this area. As of 2022, less than 6% of signature guitars were designed for women and non-binary guitarists (Horsley Reference Horsley2022). These guitars at once affirm an artist’s talent and contributions to guitar and popular music history and grant them a place among the instrument’s most important and influential figures. It highlights that these artists are not only in the ranks as the best and most iconic players and performers but also that the design and individual style of their instruments are emblematic and exemplary of popular music’s material culture.

In addition to signature guitars, musicians in this sample also promote their partnerships with guitar companies. Sarah Lipstate posted about her collaboration with Guitar Center and Fender where she discussed playing the Vintera II 70’s Jaguar (Lipstate Reference Lipstate2023). A common feature of Lipstate’s technique is that she uses a bow to play the electric guitar. In the video, she demonstrates this performance style on the Jaguar and discusses in an interview the merits of that particular guitar in relation to her preferred technique. The interview also highlights her enthusiasm for experimenting with new guitars, a process she cites as among the reasons she loves being a guitarist. Nita Strauss’ Instagram account includes content about the guitar clinics she conducts. These guitar clinics take place at guitar shops in various cities and include performances, demonstrations, and question-and-answer sessions with the audience. Strauss often posts a selfie taken with the crowd at an event to thank those who attended. Instagram content that highlights promotional activities functions as a form of validation for these musicians in how they show the nature and extent of their professional activities as well as their influence and contributions as guitarists.

4.4. Working

While live performance is among the most significant aspects of musicians’ professional lives, they are also involved in a number of musical activities, including writing, recording, and rehearsing. Working as a musician means having a career marked by a ‘particularly relentless routine of touring and recording’ (Frith et al. Reference Frith, Brennan, Cloonan and Webster2019, p. 166). Posts on Instagram show women electric guitarists working as musicians in a variety of capacities. Such content includes images in recording studios and rehearsal spaces, or videos detailing these processes and practices.

Instagram accounts highlight the use of the instrument in the recording process and demonstrate the musicians’ skill with recording technologies, sound, and production. St. Vincent included an explanation of how she developed a guitar part on her recent album (St. Vincent Reference Vincent2024). Sitting in front of a recording console and computer, she described the process of reworking a vocal melody suggested by collaborator Cate Le Bon into a guitar part for the same song and played that section of the track to demonstrate for viewers. Video content also establishes guitar performance as a process, as something that requires learning and consistent attention. Tash Sultana captured the experience of starting to practice the guitar again after an extended period of time away from the instrument (Sultana Reference Sultana2024b). Brittany Howard posted a glimpse into the rehearsal space with her band (Howard Reference Howard2024c). She featured a new release from (at the time) a forthcoming album and particularly highlighted her guitar work in the video. These types of Instagram posts show these guitarists in the process of developing and refining their practices and allow insights into the activities that shape their specific sounds, styles, and performances. They also highlight these guitarists’ knowledge and competence in relation to the wider scope of their musical careers.

These posts illustrate the varied nature of women’s practices and experiences as electric guitarists. Taken together, a review of these Instagram accounts indicates a variety of activities but also consistent patterns in terms of guitar representation and practice. The guitar-related content of these sixteen guitarists provides evidence of the distinction between them in terms of style, technique, and music contributions. It allows followers to understand these women and non-binary individuals as guitarists and the patterns that emerge through the content of their posts function to unify them as guitarists rather than on the basis of gender. It works against the problematic notion that there is an ‘essentially feminine style’ of music-making and performance (Bourdage Reference Bourdage2010, p. 6).

This type of representation is additionally significant, given the ways in which women have often been perceived as consumers of music rather than producers (e.g., Frith and McRobbie Reference Frith, McRobbie, Frith and Goodwin1990 [1978]). Instagram content serves as extensive evidence of women in the latter role and the varied associated activities. In this way, Instagram can be seen as a platform that reinforces agency not only in the specifics of the content they post but also for the broader understanding it generates. The significance of these posts is not only in their content but also in what that content allows access to – greater visibility and knowledge of their musical practices and contributions and the potential to work towards normalising them in this role and therefore take them seriously as guitarists. By serving as a space in which differences can be highlighted and recognised and the individual character of these players can be readily observed, identified, and emphasised, Instagram is a platform that can help advance the narrative of these musicians.

Scholars have observed that social media has led to greater prominence of women musicians (Choi Reference Choi2017, p. 477). In particular, performing their music online to a ‘global audience … helps put more emphasis on their music and on their musicianship’ (Choi Reference Choi2017, p. 477). Following this, it is important to note that Instagram accounts are not subject to the same type of curating and categorising found in more traditional media and within cultural institutions. This suggests that women guitarists can avoid or overcome representation solely through the labels that marginalise or exclude them (e.g., ‘women in rock’). Similar to the ways the internet has created a space for women to bypass traditional modes of learning and industry conventions that may have functioned as obstacles or barriers, social media creates an alternate approach to representation. However, this does not come without potential issues.

5. Self-representation and femininity

Outside of representations of guitar performance and practice, additional content on the Instagram accounts of the musicians in this sample demonstrates that some guitarists give strong attention to appearance. Based on the specific nature of the content, it can be said that some of these images and representations demonstrate and reproduce stereotypical norms and expectations related to beauty and femininity – particularly those posts that make the body and appearance an overt feature, draw on traditional expectations of femininity, or feature sexualised images. These observations are not value statements or judgements about the ways in which women choose to represent themselves or express their gender; they are observations of the nature of content and what that can signify in the world.

Of the accounts examined for this study, those of Larissa Liveir, Orianthi, Nita Strauss, and H.E.R. featured such representations most prominently. Larissa Liveir is a guitarist based in Brazil who, as mentioned, utilises Instagram primarily to perform instrumental songs on the electric guitar. A consistent and noticeable feature of her performance posts is the manner in which she is dressed. She typically wears clothing that draws attention to her body and reveals her cleavage, arms, and legs. She also regularly smiles at the camera. Orianthi is an Australian guitarist who previously toured with Michael Jackson. Representations of beauty, appearance, and femininity are regular elements of her Instagram. She is often seen heavily made up and positions herself in poses that suggest she is the subject of the gaze. Nita Strauss, known for being the touring guitarist for Alice Cooper, similarly utilises such types of content and body positioning. Strauss emphasises the body in a variety of ways, such as in demonstrations about workouts or clips of her preparing her appearance before a concert. She also highlights her personal life and marriage to her manager/drummer, which are often underpinned by romantic or sexual tones. H.E.R.’s Instagram content is heavily centred on images that emphasise beauty and appearance. She frequently includes posts of close-ups of her face and images that are focused on her clothing and body.

In other Instagram accounts in this sample, such content is present but more minimally. For example, Lzzy Hale of the band Halestorm posted a video in which she asked her followers to let her know what they wanted her to wear on the upcoming tour (Hale Reference Hale2024a). The post features her modelling an array of styles and outfits from which followers could choose. The notion of her followers essentially dressing her represents a level of pleasing and being the subject of the gaze and an absence of agency and authenticity.

For the musicians who draw on more traditional femininity, beauty, and sexuality in their self-representation, it is hard to claim completely that such images fully distract from knowing them as musicians due to their interconnectedness with guitar practice. Representations that focus on appearance or suggest a sense of passivity are countered or balanced by the more active content of guitar performance and musical activity. In many instances, these types of representations are seen together. These factors are interesting in thinking about previous research on women and the electric guitar. As noted, Bayton and Bourdage identified expectations around femininity as among the social barriers to women becoming electric guitarists and discussed the view that women guitarists break the gender code due to its masculine association. However, representations on Instagram show an integration of beauty and femininity into their identities as guitarists. These examples illuminate limitations in previous work and confer that adhering to or expressing more traditional femininity does not necessarily inhibit a woman from becoming a guitarist. Rather, such types of femininity can coexist with electric guitar performance. The intersection of femininity and the electric guitar can be interpreted in various ways. On one hand, women’s femininity can be seen in opposition and as a way to overcome or reject the masculine association of the electric guitar. On the other, it can be seen as a means to compensate for the masculine association. By placing emphasis on beauty and femininity, women can be seen to distance themselves from such associations and thereby make them more acceptable.

Style and appearance are also addressed and expressed in different and creative ways on Instagram accounts. Joan Jett’s longevity and influence are apparent in the way in which it is presented in a fun and playful manner, which also functions as a type of tribute and shows her influence. Jett posted a Halloween costume contest called ‘dresslikeJett’ for her followers in which they were asked to send their impersonation of their ‘best’ Joan Jett looks (Jett Reference Jett2022). The images of participants included wigs, her iconic blazers, and leather trousers, and some of the costumes included the presence of the electric guitar. These posts, and her ability to generate such interest, attest to the iconic status of her style and position it as a highly recognisable feature of her musical identity. So many entries were received that three winners were selected rather than one.

An interesting aspect of this celebratory view of Jett’s style is the ways in which she has always maintained a more masculine-coded or non-traditionally feminine image and performance style. Along with Chrissie Hynde, she and Jett have been described as the aforementioned ‘trying to be one of the boys’ or perceived as deliberately employing masculine style and performance techniques to fit in as electric guitarists. A view that has been largely overlooked is that such a form of expression is connected to identity and personal comfort with non-traditional femininity and expression. To reject that is to place normative standards and expectations onto women who may not adhere to those views in their own identities. Jett and Hynde have both spoken about this in interviews and have self-identified as ‘tomboys’ among other characterisations. Philip Auslander (Reference Auslander2006, p. 212) has utilised the term ‘female masculinity’ to account for such gender expression. He argues that this style is ‘not simply the emulation of masculine-coded musical gestures’ (Haddon Reference Haddon2019, p. 179) but more ‘a refusal on the part of … women to repress that aspect of themselves in favour of the masquerade of normative femininity’ (Auslander Reference Auslander2006, p. 212; see also Haddon Reference Haddon2019, p. 179). In this way, Jett is among the electric guitarists in this sample who are shown to reject stereotypical expectations of gender and femininity and put forward personal style and expression.

While the content of Instagram accounts does indicate some emphasis on beauty and femininity, overall, this study observed a range and diversity in self-image. The sample shows that women electric guitarists ultimately exemplify unique and personal style that functions to distinguish them. The unique image and personal style of the two members of Larkin Poe, Angie Swan, Yvette Young, Bonnie Raitt, Brittany Howard, and Tash Sultana, as examples, indicate diversity in self-expression among women and non-binary individuals who play the electric guitar. Rendering such differences visible expands the spectrum of images, identities, and gender expression in relation to the electric guitar. This suggests that norms and expectations around femininity do not necessarily enable or constrain pursuing the instrument and that the guitar is accessible to individuals regardless of how they express their gender and style.

In addition to appearance, expression, and questions of femininity, gender features as a discussion topic in the Instagram accounts of electric guitarists, which highlight interactions with issues and experiences related to gender. For example, Tash Sultana, who identifies as gender fluid and uses they/them pronouns, regularly posts content to raise awareness about gender non-conformity and the transgender community and started a charity for support and activism. Yvette Young has highlighted how some of her experiences as a musician – such as the view that she needs help carrying her own equipment – have been shaped by gender and has rejected such stereotypes and expectations through social media content (Young Reference Young2022). Women also engage in humour to describe their experiences as musicians, such as Lzzy Hale’s reflection on the perks of being the only woman at a festival is having the bathrooms to herself (Hale Reference Hale2024b).

The significance of the intersection between representing guitar practice and self-image is also relevant to another aspect of the scholarly literature on women and the electric guitar: that of role models. Previous research (Bayton Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997; Bourdage Reference Bourdage2010) has highlighted the limited number of female role models as another barrier women encounter in becoming electric guitarists, and we can observe much wider awareness of this concept in other male-dominated occupations. The argument put forth is that having relatively few women role models leads to a lack of self-identification and inspiration (Bayton Reference Bayton and Whiteley1997). The implication of a male-dominated field is that it can function as a barrier to women occupying the same role. Women interested in the instrument may feel inhibited due to an inability to see themselves occupying such a role. Other scholarship has shown that women musicians cite extra-musical qualities in their female mentors and heroes, such as how ‘powerful and strong’ Bonnie Raitt was in concert, as well as what could be learned from her (Carson et al. Reference Carson, Lewis and Shaw2004, pp. 161–62). In other words, women identified aspects of musicians as inspiring and influential that were not solely linked to their roles as instrumentalists. For example, their style, appearance, and perceived attitudes were cited as reasons for identifying with a role model and being inspired to play the guitar. In view of the historically masculine association of the electric guitar as a potential barrier to women, diversity of representation may be important in attracting future generations of electric guitarists.

6. Conclusion

In reviewing and examining the Instagram accounts of sixteen electric guitarists, the findings that emerged showed diverse representation in terms of guitar practice, self-image, and presentation. Representations of electric guitar practice highlight a diversity in terms of style and technique and those of self-representation indicate a range of self-expression and style. These electric guitarists do not solely rely on traditional norms and expectations around beauty and femininity in their Instagram accounts. The diversity of representation offers important insights into and more nuanced interpretations of the interaction between femininity and the electric guitar that was articulated in previous studies.

The male-dominated history and masculine association of the electric guitar have often led to the underrepresentation of more diverse forms of gender expressions in relation to the instrument. It has also meant that particular bodies have been imbued with authority over guitar style and technique. In this way, Instagram is a platform through which greater visibility and awareness can be generated and observed. The affordances of Instagram to disseminate visual imagery that highlights a range of skills, techniques, and performances work to integrate diverse practices into the narrative of the instrument. In doing so, it works to normalise a more inclusive group of musicians through the evidence of their abilities as electric guitarists. The connection between the range of skills on display and the individuals performing them destabilises the male-centric dominion of guitar technique, innovation, and virtuosity. In establishing the wide range of musical skills, styles, and contributions that women and gender-diverse electric guitarists make, Instagram content enables a better understanding of who can play the guitar while also validating the importance of the many types of guitar performance.

The ability to self-represent on Instagram also allows electric guitarists to be understood outside of the editorialising and discursive constructs of other forms of media. These findings are particularly important in view of the discourses and representations that have historically categorised women on the basis of gender and ultimately limited their understanding. Instagram is a platform through which individual self-expression can be observed in its own context. These Instagram accounts, taken collectively, provide evidence of the variation between women electric guitarists that renders notions of an ‘essentially feminine style’ or discourse that categorises them as ‘women in rock’ as inaccurate terms. These social media accounts of electric guitarists overcome the problematic exceptionalism of ‘women in rock’ discourse that tends to undermine their abilities and achievements through categorisation. Instagram enables access to first-hand accounts of these musicians’ distinctive performance styles without reductionist and essentialist tendencies to foreground or utilise the category of gender as a modifier. The representations featured on Instagram allow access to the process of women’s artistic development and the maintenance of self-identity (Hargreaves et al. Reference Hargreaves, MacDonald, Miell, Hallam, Cross and Thaut2016, p. 126; Herbst and Menze Reference Herbst and Menze2021, pp. 98–99). In generating awareness and visibility of these guitarists’ distinct musical contributions and unique qualities, the content of Instagram posts is a resource for expanding the narrative and developing a larger vocabulary for talking about electric guitarists. Through visual and audio representation, it also affords the possibility of inspiring other people to play the electric guitar.

An analysis of representation is the first step in understanding the relationship between electric guitarists and Instagram content. Further research into this topic could explore the reception of followers on Instagram to women and gender-diverse electric guitarists in online spaces through surveys or by investigating online interactions. Doing so would further gauge the impact of the Instagram posts’ content. Qualitative interviews could be conducted with electric guitarists to gain a deeper understanding of their use of and intent with social media content as well as about the choices they make regarding the representation of their practice and selves. Comparative studies could also be useful for understanding the differences and similarities in the social media experiences and representation of women, men, and gender-diverse electric guitarists. Additionally, the content of social media accounts on other platforms could be explored to expand, nuance, or counter findings based on an analysis of Instagram.

The analysis presented here has not been intended to take a utopian view of the possibilities or affordances of the internet and social media nor does it negate its potential to reproduce stereotypes. The research findings have demonstrated that Instagram is a platform that can both reproduce existing social norms and gendered stereotypes at the same time that it can reinforce women’s agency. However, the accounts examined here also show that Instagram is a platform that does not only reproduce stereotypes. Research has emphasised that the reproduction of stereotypes and normative expectations regarding beauty and femininity generate the most attention and visibility, while at the same time, social media platforms such as Instagram can also serve as an effective space for deconstructing them (Bishop Reference Bishop2018; Duguay Reference Duguay and Papacharissi2018). Further, though the sample of social media accounts discussed here indicates a range of representations among women electric guitarists, scholars have clearly demonstrated that platforms such as Instagram are not diversity-friendly or inclusive digital spaces across identity categories including gender and race (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2019; Noble Reference Noble2018). The aim of the analysis has been to show the significance of these factors and how they operate when being situated within the existing literature on gender and the electric guitar and in view of the barriers, challenges, and historical representation that has shaped musicians’ experiences.