In the early twentieth century, epidemics of rinderpest and sleeping sickness spread throughout western Uganda.Footnote 1 These episodes were, by all accounts, devastating to families in the region. Cattle-keeping families saw their households break apart and contended with hunger and starvation.Footnote 2 A crisis of this magnitude prompted various responses: some traveled long distances to escape the disease; some began dividing up their cattle and sending them to different locations to minimize risk.

Still others—women who are the focus of this article—memorialized these losses, mourned their dead cattle, and narrated the tragedy for future generations through song and accompaniment on a musical nanga instrument. Through song, these women critiqued a negligent colonial government while underscoring their cattle and lands’ importance to their community’s identity.

These nanga songs played important social roles by narrating regional history and shaping ideas about community identity in western Uganda. Yet because of environmental change, population displacement, economic and political marginalization, and colonial and postindependence school curricula that standardized some musical traditions while ignoring others, the practice of nanga performances in Busongora has waned throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Only in recent years, propped up by development efforts seeking to preserve and protect “heritage,” has nanga-playing been the focus of programming that standardized and “protected” its narratives, albeit with emphases shaped by twenty-first-century themes and priorities.

A focus on these songs reveals two related arguments. First, these nanga (also written “enanga”) songs contain valuable information that historians can—and should—use to understand histories of environmental catastrophes, cattle-keeping practices, land conflict, community norms, and elite politics from the perspective of non-elite observers. The accounts provide different perspectives on well-known events as well as new information on lesser-known events that evaded the written archive. Second, this knowledge is important not just as a font of primary source information but also as evidence of women’s roles as public intellectuals who helped communities mourn disease, celebrate victory, and establish social norms. By ignoring this knowledge, we overlook women intellectuals’ vital social roles and their participation in identity formation and community building. Centering these songs and their performers reveals an example of women-led historical narratives that served as important affective spaces for their communities.

Music, Affect, and Identity in Africanist Scholarship

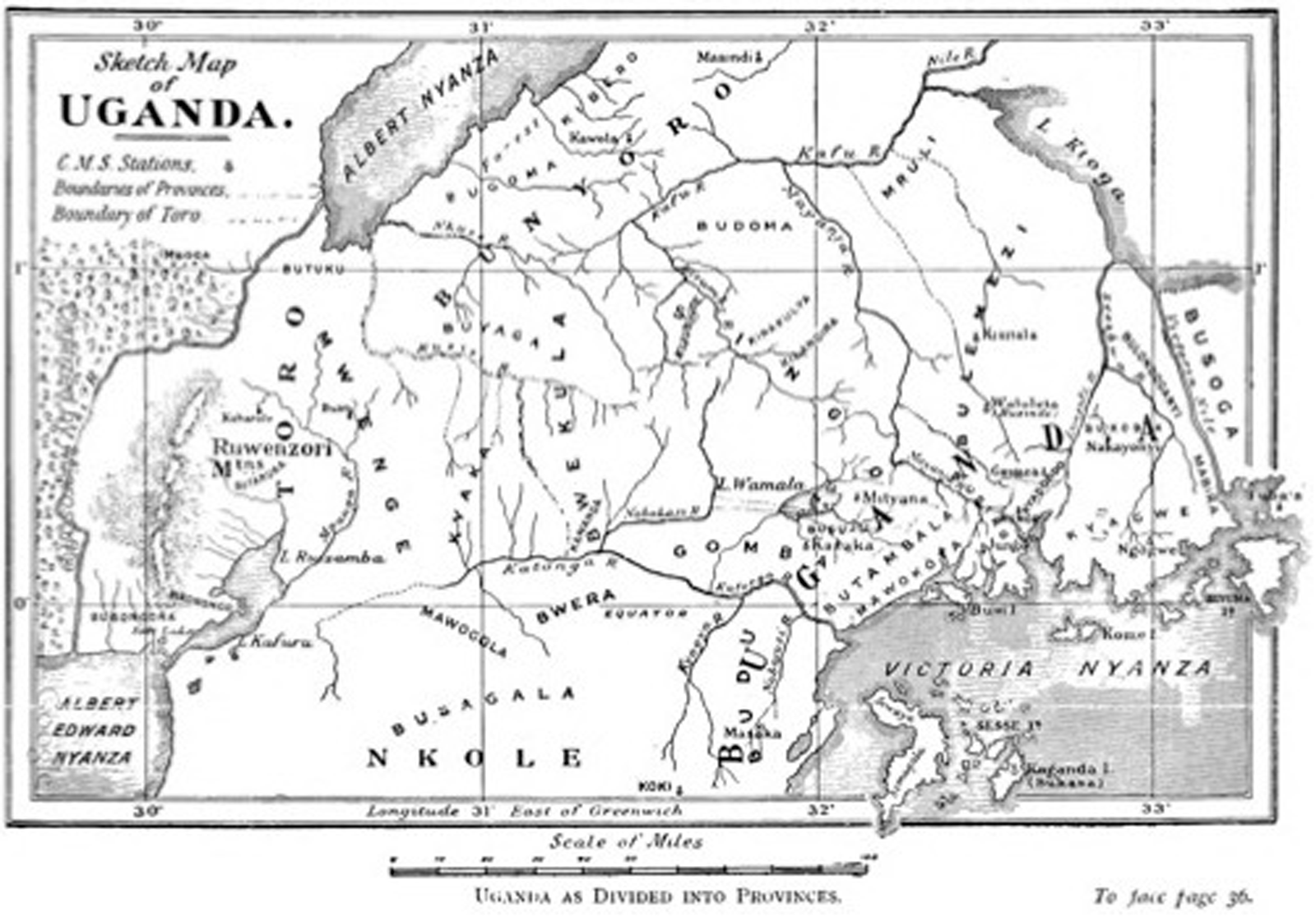

While variations of the nanga harps are found across the region (see Fig. 1, below) and the continent, this article focuses on regions of western Uganda where nanga is played exclusively by women: primarily Busongora, but also Toro and Ankole regions (Fig. 2, below).Footnote 3

Figure 1. Depictions of the different kinds of Ugandan zithers–often called nanga.

Figure 2. Map showing both Busongora and Toro in western Uganda, published in 1900.

In these regions, the instrument usually has six strings, strung across the length of an oval-shaped trough. Performers often rest the body of the instrument on top of a circular object, like a pot or gourd, to amplify the sound.Footnote 4 Several mentions of nanga-playing in the written record confirm that it was women from cattle-keeping families who led these performances in the western part of Uganda. This set these regions apart from other regions studied by scholars—including the Haya region examined by M. M. Mulokozi.Footnote 5 Writing in The Uganda Journal in 1938, F. Lukyn Williams assessed that among “Hima” women in this area, nanga songs “are only sung as a rule by the older women, who are proficient in the harp.”Footnote 6 In the same year, Klaus Wachsmann, who later collected dozens of nanga songs in his career as an ethnomusicologist, wrote that in the royal courts of Toro and Bunyoro, as well as among the cattle-keepers of Ankole, “only women” are allowed to play the instrument.Footnote 7 Margaret Davis’s Runyoro-Runyankole dictionary defines the nanga specifically as a song sung by women.Footnote 8 During my 2019 fieldwork, I was repeatedly told that only women perform the nanga, while men have their own separate kind of musical performances.Footnote 9

This article uses these musical performances, oral history interviews, and archival sources to build upon important research on the role of musical performance in crafting national, ethnic, or communal identity.Footnote 10 Africanist scholars have analyzed musical and oral performances to access emotions, narratives, and cultural practices that evaded traditional colonial archives, and these performances have provided insight into continuities and ruptures of cultural practices in the wake of destructive imperial conquest or control.Footnote 11 In particular, Kelly Askew has shown how musical performances in Tanzania helped negotiate ideas about nationalism and identity, while Moses Chikowero has explored struggles over musical performances during colonial rule in Zimbabwe.Footnote 12 Others, including Laura Fair, have examined how music shaped women’s influence in politics, identity formation, and nationalism.Footnote 13 In analyzing the social role of nanga performances, I follow Askew’s focus on identity, Fair’s examination of “pastimes”’ influence on politics, and Chikowero’s emphasis on the affective “moral codes” and “societal values” to explore how nanga players’ historical narratives helped participants and audience members grapple with past events, critique political leadership, and think of themselves as a community.Footnote 14

Yet by also insisting on these songs’ place within intellectual history, my analysis moves nanga songs into a scholarly category that has often been the domain of male elites and literate intellectuals. Extant scholarship in African history has shown how historical knowledge contributes to ideas about ethnicity, nation, and race. Whether historicizing ethnic violence, exploring indigeneity claims amidst conflict over land, or charting the rise of widespread nationalist commitments, this scholarship has shown that ethnicity was neither a static biological reality nor was it simply invented by European colonists and imposed unilaterally. Rather, African intellectuals took an active part in these intellectual processes, often using history as a fundamental ingredient in doing so.Footnote 15 To this end, scholarship has described “ethnic patriots” who defended their secessionist cause with detailed historical research about the mistreatment they had suffered from neighboring kingdoms or “activist historians” who used history to justify challenging those with power.Footnote 16 Still others—”homespun historians” who crafted historical narratives, weaving together oral and written sources—produced narratives that gave rise to “imagined communities.”Footnote 17Recently in Ugandan studies in particular, Jonathon Earle has articulated how intellectuals reimagined political futures on the eve of independence and Patrick Otim has shown the role that overlooked intellectuals played in mediating the transition to colonial rule.Footnote 18 Yet, as many scholars who have studied these intellectuals have acknowledged, virtually all those examined in this literature are men.Footnote 19 Following Otim’s compelling call to expand our category of intellectual actors, this article introduces an important additional (and previously overlooked) group. Women who narrated history through nanga songs also produced histories that contributed to group identity—yet that historical production, in this case, took the form of songs and musical performances rather than written histories or petitions.

Drawing on Jan Shetler and Heidi Gengenbach’s work that began to correct for this trend and emphasize the community-building role of women’s knowledge, I show how nanga songs played similar roles through chronicling important regional histories.Footnote 20 That nanga characteristics differed from the kind of historical knowledge that attracted attention of both colonial and contemporary scholars is part of a larger story, delineated by Nancy Rose Hunt, about intellectual history’s tendency to “bifurcate” intellectual history and considerations of affect and emotion. Hunt argues that extant scholarship places the two “seemingly at odds with each other.” In order to better account for various forms of intellectual production—and also in order to bring women into accounts of Africanist intellectual history—she argues that it is “crucial to seek ways to cross and combine” studies of affect and intellectual history.Footnote 21 This article responds to Hunt’s call, bringing together the affective dimension of nanga songs and taking seriously the intellectual content and function these performances played to show how they articulated a shared past that emphasized a communal identity.

Nanga in Western Ugandan History

Nanga-playing enters the written historical record in the nineteenth century. Developing a comprehensive history of nanga playing presents difficulties, in part because it was rarely a topic of interest for colonial-era observers. During his expedition of the Nile from 1860–63, James Grant wrote about seeing a nanga in the Karagwe kingdom of northwest Tanzania. Though in Karagwe (unlike western Uganda), men and women both performed nanga, Grant’s account confirms nanga’s public, educative, and performative role. He wrote that a famous nanga player performed a song about a favorite dog for him, attracting “a crowd of admirers,” but was more dismissive of the woman who performed next: “all the song she could produce was ‘sh,’ ‘sh,’ screwing her mouth, rolling her body, and raising her feet from the ground.”Footnote 22 Many of the songs still sung today begin this way, with a “sh” sound that later leads into more narrative verses, but whether the performer intended to proceed further is unclear. Grant concluded, “It was a miserable performance, and not repeated.”

This dismissiveness reappears in several contemporary accounts: John Roscoe described witnessing women sitting together while “one of them played a harp and sang while the others moved their bodies and arms.”Footnote 23 Roscoe never names the harp as a nanga, but the description of the performance—especially when paired with an image a few pages before, which uses similar language and features a nanga (reproduced below in Fig. 3)—makes it clear that is indeed what he observed. Puzzlingly, in the same paragraph, Roscoe writes that “there was little attempt at music among the pastoral people,” and proceeds to focus more on the (lack of) dancing associated with nanga-playing than the musical compositions.

Figure 3. Image of nanga players.

In the image, which he again describes as featuring “fat women” who are “sitting to dance,” we can see a group of women sitting together, with one playing a nanga on top of a stool. Though Roscoe attributes their sitting to being “too fat to dance,” Linda Cimardi has offered a more nuanced analysis, noting that the “typically feminine sitting position” that involves “legs bent on the side” is in keeping with a performance considered most appropriate for women.Footnote 24 Isaac Tibasima Kiiza has explained this further, noting that traditionally in Toro, women were not supposed to stand before the king.Footnote 25 Elsewhere, Roscoe again wrote that “the Bahima [were] not a musical people as regards instrumental music” and that their “only instrument” was “a harp which the women have and keep for use in the home for accompanying the love-ditties which they sing to their husbands.”Footnote 26 As this paper will show, Roscoe was wrong on several counts: women did not only play nanga at home; their public and educative performances played important social functions. And while affect was indeed a key feature in nanga performances, the seemingly belittling label of “love-ditties” obscures the influence of such emotions that scholars of affect have shown Africanist historians should take seriously.Footnote 27

Shaped by both racism and sexism, this dismissive attitude towards nanga playing may have contributed to a relative paucity of colonial-era sources on nanga player and their performers: the same dismissal is found in Ruth Fisher’s account of music in Bunyoro—a place she misguidedly describes as “a country absolutely void of music.”Footnote 28 She makes a lukewarm exception for the harp: “the only instruments that gives forth a note or something that is not a roar or squeak, is the harp.”Footnote 29

Nanga playing also sometimes accompanied activities suppressed by missionaries and the colonial government, which might have compounded the difficulty of finding mention of the practice in the written record. For example, Paul van Thiel described nanga music that accompanied public healing Cwezi rituals, which featured songs—”mainly fascinating eulogies”—that were “sung simultaneously with the music of the trough zither (enanga), played by the Hima women.”Footnote 30 Women also played nanga at beer drinking parties, which—like the Cwezi rituals—were met with disapproval or outright prohibition from missionaries and later African Christian converts themselves.Footnote 31 In 1912, missionary Arthur Kitching noted repression of musical performances in neighboring Buganda, which likely extended to Toro, writing that “harp playing has been discouraged by Christian opinion in Buganda, as it is considered loud and suggestive.”Footnote 32 This dismissiveness or hostility created archival limitations that, at least in part, prevented nanga from receiving more thorough academic attention.

With time, colonial-era ethnomusicologists took an interest in nanga songs and began recording them, but the colonial context continued to shape the songs even once they entered the archive. Anette Hoffman has written about colonial sound archives that are both fragmented and collected in contexts of violence; both of which are relevant to this study.Footnote 33 Recent research on the songs in the Klaus Wachsmann collection, some of which I analyze below, investigates the conditions under which the recordings were collected and the shortcomings in their preservation and accessibility. Sylvia Nannyonga-Tamusuza and Andrew Weintraub are doing important work to repatriate those songs, hopefully prompting more conversation about these local histories, with audiences whose understanding of them is likely multifaceted and layered.Footnote 34 Even with broader accessibility, some recordings remain difficult to hear clearly, and most of Wachsmann’s recordings (along with those by Peter Cooke and Hugh Tracey) were from the center of Toro, so I conducted interviews myself or relied on lyrics contained in other written sources for songs from Busongora.Footnote 35 More work should be done to analyze and recognize more of these songs: as this article argues, they are promising sources for historical study and powerful examples of women’s role in community identity formation and social protest—including protest of the very colonial regime that originally sanctioned their recording.

Narrating Regional History

Nanga performances in Busongora often grapple with themes related to regional history, frequently emphasizing the region’s history as one of outsiders making repeated claims on the resources and riches of the land. When local trade became increasingly lucrative in the eighteenth century, rulers of neighboring Bunyoro kingdom began trying to exact tribute.Footnote 36 In the nineteenth century, leaders in Bunyoro as well as newly independent Toro, which had seceded from Bunyoro in 1830, competed over control of Busongora.Footnote 37 Control of the region remained contentious through subsequent decades, and in 1893, Henry Morton Stanley wrote that control of Katwe, part of Busongora with lucrative salt reserves, was “a cause of great jealousy.”Footnote 38 Colonial conquest, violence, and administrative rule followed, which placed Busongora within the Toro kingdom. In addition to prompting complaints of Toro negligence in Busongora, this period introduced new tensions over land access with the establishment of Queen Elizabeth Park in Busongora in 1952 and extreme loss and violence due to colonial management (and mismanagement) of diseases like sleeping sickness and rinderpest.Footnote 39

These historical contests over land and leadership appear in nanga songs in both Toro and Busongora. One nanga song in Toro, “Kasunsu Nkwanzi,” celebrates their first king, Kaboyo, who broke away from Bunyoro in 1830. The title is Kaboyo’s nickname, meaning “head of princes.”Footnote 40 Both Elizabeth Bagaya and Akiki Nyabongo, each a member of Toro’s royal family, included its lyrics in their books.Footnote 41 The song praises Kaboyo, emphasizing the geographic reach of his new kingdom. As Isaac Kiiza has shown, it tells a history that “authenticates Toro and its existence.”Footnote 42 This song was likely most often played in the heartlands of Toro, rather than in Busongora, which had met Toro rule with either ambivalence or opposition.Footnote 43 Many of the nanga songs played in the Toro palace celebrated the royal family and the kingdom’s past accomplishments. Wachsmann’s recording of a nanga song about the former ruler Kyebambe identifies the performer as a “princess,” again showing these songs’ connection to royal politics.

A few dozen kilometers south of the Toro palaces, nanga songs from Busongora also depict these political histories. However, when produced at the margins of the kingdom, these narratives differ from those created in the royal center and thus provide useful alternatives to accounts of royal power written by the kingdom’s elites. As Kiiza has described, the nanga in Busongora, unlike those further north, often reject incorporation into the Toro kingdom and lament perceived mistreatment at the hands of Toro leaders, resulting in what he calls “a defiance against colonialism of Toro.”Footnote 44 Grievances against the Bunyoro kingdom feature too. When the famous Nyoro king, Kabalega, launched his wars to reincorporate Toro into his kingdom in the 1880s, Busongora’s cattle, ivory, and salt were especially desirable.Footnote 45 One informant born in Busongora in the 1950s recalled learning through nanga songs about Kabalega’s raids in the 1880s, where he invaded their territory and instigated heavy fighting.Footnote 46 One interlocutor described songs about how Kabalega “took many young Busongora girls,” emphasizing this song “became a very common one because he took so many captives here.”Footnote 47

Other songs feature less-famous characters of the region’s past. One in particular details the escape and eventual downfall of Musuuga—the brother of Kasagama, Tooro’s king from 1891 to 1928. Kasagama famously fled to Ankole as a child with his mother and “other princes”; Kasagama and his mother escaped a plot to kill them, but the others in their entourage did not.Footnote 48 Musuuga, presumably, was part of that less-fortunate entourage. The song describes how Musuuga fled from the Bunyoro kingdom’s capital to Ankole, to hide from the wrath of the king, only to be later killed in exile. One section proclaims, “Musuuga, the joy, has been revealed… He got the wrath from the capital/He got the cannon/large gun from his Father’s house.” Footnote 49 A thorough examination of extant written histories about Kasagama’s family reveals little about Musuuga beyond basic biographical details.Footnote 50 Collecting additional versions of this song could reveal more details about the less-elite members of Toro’s history, including more information about their lives, their relationship to elite politics, and their reception and relevance to western Ugandan populations. Meanwhile, other songs move away from political histories and instead shed light on non-elite participation: one woman in Busongora described a nanga composed by a female relative around the year 1910 in honor of her grandfather’s bravery in battle, which is still sung today.Footnote 51

Mourning Disease and Cattle Crises

Especially in Busongora, many songs describe the environmental crises and disease epidemics that shaped the region in the first half of the twentieth century. These were unfortunately frequent occurrences. An 1890s epidemic that “destroy[ed] most of their cattle” recurred a few decades later in 1919.Footnote 52 Sleeping sickness epidemics caused unprecedented death rates in the region.Footnote 53 Some early explorers and colonial records documented these epidemics. When Frederick Lugard traveled through East Africa, he was reportedly struck by the immense devastation, starvation, and suffering he witnessed amongst the “pastoral people.”Footnote 54 Though these chroniclers certainly had reason to exaggerate the desperate conditions they encountered to justify greater colonial presence, scholars have shown that the disruption of colonial conquest itself exacerbated these conditions.Footnote 55

In addition to chronicling rinderpest epidemics, nanga songs shed light on colonialism’s destructive policies towards Ugandan pastoralism that are (often purposefully) avoided in the colonial archive. In one song, women describe a cattle tax imposed by the king of Ankole (known as the mugabe): “the Mugabe told the Bahima to bring in cattle as a tax, but instead they fled.”Footnote 56 Other songs lament the new colonial technologies and medicines that caused loss and hardship in these women’s lives. One song explains that whereas in the past, cows were treated with ghee to protect against ticks, colonial rule in Busongora introduced treatments involving insecticide and spray. As a result, the cattle’s health worsened. One song’s references to “drugs in bottles” that ultimately led to the death of more cows specifically refer to the colonial government’s project of injecting cattle with a drug that was supposed to protect against rinderpest.Footnote 57 The song’s assertion that the effort ultimately hurt more cattle than it helped is one that has been repeated in the years since. The deaths are also attributed to the shot that was given to cattle under chief Ntarishokye—leading to the common explanation of the cattle deaths, “ekikatu kya ntarishokye” or “the shot of Ntarishokye.”Footnote 58

These accounts provide insights into Uganda’s economic and social history rarely gleaned from the colonial archive, which is of course unsurprising given a colonial aversion to revealing colonialism’s abuse, violence, and malpractice. However, anthropologist Melvin Perlman, who conducted his fieldwork in the 1950s and 1960s, recorded in his fieldnotes the following interaction with the district veterinary officer in which the official admits colonial culpability: “[He] told me privately, as he put it…that it was probably the fault of the Vernary [sic] Dept. that so many cattle died in the 1920s.” He explained:

The reason for this was that they did not change needles when they were giving injections. They would inject a drug against rinderpest, but at the same time they would probably get some blood from an animal infected with tsetse fly, and then with that same needle–inject another previously tsetse-free animal with tsetse fly, although they injections against rinderpest may well have been effective. But he will not admit this to the local people because he has now spent a long time building up his reputation, and he cannot afford to mar it.Footnote 59

Nanga songs, therefore, publicly narrate a historical event that is otherwise only found buried deep in the archives of the School of Oriental and African Studies. However, in the Ugandan government’s 1920 blue book, the section on “inoculation of cattle against rinderpest” (for which the government charged 1–2 shillings depending on the animals’ age) includes a provision that declares “fees not payable for cattle dying as a result of the inoculation,” suggesting the government was indeed aware that these inoculations posed a risk to the cattle they claimed to be protecting.Footnote 60

Articulating Affective Identity and Belonging

By chronicling these overlooked histories, many of these songs contributed to ideas about identity. Often, they did so by providing lessons about moral ethnicity and civic virtue: telling stories that promoted characteristics defining a particular group and its inward-facing norms or sharing narratives that communicated personal responsibility and communal participation.Footnote 61 The gendered expectations of women and girls learning to great visitors into their homes—observed across the continent—was conveyed in a one nanga song.Footnote 62 The lyrics read: “Let me go to the home of the pure hearted/ the kind…/ Why would I visit the ill hearted people’s homes?” Other songs emphasized the herding identity of the nanga playing women and those (including children they were educating) in the audience:

Kankujume mwaana wa muhuma we iwe, Kowensama

Koija kuseetura okasanga hairungu, Kowensama […]

Koija kuhabura okasanga zakuuka, Kowensama

Let me give you a piece of advice you child of the noble one! Kowensama

By the time you take the cattle to feed, the pasturage will have dried out, Kowensama

By the time you want take the cattle to the well, you will find them gone, KowensamaFootnote 63

Another song highlights ideas about communal responsibility and responsibility through a story about a boy named Rwamutanga who protected cattle in Kasese from a threatening lion:

Rwamutanga nkamurora obwaijweri

Rutanga yange obweramarwa eya Kasese

Aha! Aha! Ah! Ah!

Rwamutanga obweramarwa eya Kasese

Ah! Ah! Ah! Ah!

Rwamutanga akaisa entale omwigo

Ah! Ah! Ah! Ah!

Rwamutanga yayemera yabakira Rutanga yange

Yairuka yabakira

Ah! Ah! Ah! Ah!

Rwamutanga enganzi murole ezi isamira ndaicwa ebisibo nka’enyana ento

I saw Rwamutanga some time ago

When my Grey bull was devoured by the lion of Kasese

Ah! ——_

When the lion of Kasese devoured my bull

Rwamutanga killed it with a single club

Ah! ——

Rwamutanga was the bravest of them all present…

When my Grey Bull was devoured by the lion of Kasese

Ah! ——

Blood-friendship necessitate good calf present

Ah! ——Footnote 64

Solomon Mbabi-Katana proposed this song for use in Ugandan schools in 1972, explaining that Rwamutanga’s father wrote the song so that “his legendary son will always be remembered.”Footnote 65 This song provides details on cattle-keeping history, a historical community member, and regional dangers of wildlife—and illustrates how nanga songs could provide chronicles of local history that were then passed down. The song highlights aspects of civic virtue: the responsibility of sons to family, the respect accorded to those who protect their cattle, and the value of bravery in the face of a threat. Certain elements of the song also would have been more comprehensible to the audience members listening: the name “Rwamutanga,” for example, comes from the root word, “okutanga,” meaning to reject or refuse. Children were sometimes given this name who escaped (“refused”) death at birth, so the use of his name here could reinforce the message of a hero who rejects the death of precious cattle.

Mbabi-Katana describes this song as “A Hamitic Basongora Story song,” but never specifies that it is a nanga. That the father composed the song is curious, as most nanga players described women composing songs (though none ever said it was exclusively so). It is possible that it was not a women’s nanga song—we cannot know conclusively based on the information provided—but it seems likely that it was. The Busongora origin, emphasis on cattle, and label of “Hamite” make it likely, as nanga songs were the most common genre that dealt with these topics. Furthermore, there are several indications from the musical score that women would have sung this: the score shows that the range of notes, tempo, and minor key all match those of a different song in the collection that is confirmed to be meant for women. The range of the notes, too, suggests a high pitch commonly sung by women.Footnote 66

In some cases, nanga songs contributed to identity formation by articulating historical narratives that juxtaposed nanga-playing pastoralists with their non-pastoralist neighbors. Some informants described nanga songs that lament their loss of land by specifically referencing when Konzo populations came down from the hills and settled in good grazing lands.Footnote 67 Another song that Mbabi-Katana recorded—which he this time specified was a women’s song—also focuses on these themes that emphasize difference between pastoralists and their neighbors:

Abairu muror’abo banunka ihaya nk’embuzi Rwanzira Mn

Rwanzira Mn

Banunka ihaya nka embuzi Mn

Banunka ihaya nka embuzi basarra ppe nka etaaba Rwanzira Mn

Rwanzira Mn

Bahuma muror’abo Mn

Bahuma muror’abo Rusasa rwomubarama Rwanzira Mn

Rwanzira Mn

Rusasa rwomubarama Mn

Rusasa rwomubarama Kitabe kya Busongora Rwanzira Mn

Rwanzira Mn

Kitabe kya Busongora Mn

Kitabe kya Busongora Emisole ya Butuku Rwanzira Mn

Rwanzira Mn

Emisole ya Butuku Mn

Emisole ya Butuku Eraza ya Mwenge Rwanzira Mn

Rwanzira Mn

Eraza ya Mwenge Mn

Eraza ya Mwenge Eraza ya Mwenge Rwanzira Mn

Mbabi-Katani summarized and translated these lyrics as:

Agriculturalists [Bairu] smell [like] the odour of goats

Yes Rwanzira, yes

Which tastes as bitter as tobacco,

Yes, Rwanzira, yes.

Pastoralists [“Bahuma”] smell sweetly [literal: “like the perfume made from a tree called rusasa rwomubarama”]

Yes, Rwanzira, Yes

Which taste as delicious as a Busongora dish [literal: Kitabe kya Busongora]

Yes Rwanzira, yes

Also, the scent reminds one of Butuku’s perfume

Yes, Rwanzira, yes

Also, it reminds one of Mwenge’s perfume

Yes, Rwanzira, yes.Footnote 68

This song contains information on gendered comportment, mentioning the type of food they eat (made of milk and butter) and specific perfumes they consider desirable. The reference to Mwenge, long reputed for its good grazing lands for cattle, further connects the song to pastoralism, while conjuring specific smells that audiences would have been familiar with could have lent added emphasis. Furthermore, drawing on the word for “prohibited” or “to be taboo” (-zira), “Rwanzira” as the main name further underscores in-group versus out-group dynamics.Footnote 69 When Hugh Tracey collected and recorded this song in 1950, he noted that it was most often sung at weddings.Footnote 70 This context for this song’s performance is also important: it means that women would have been praising (the presumably pastoralist) groom and validating the bride’s choice of partner. That setting and audience shape our understanding of a song—and that different audiences would understand certain elements while missing others—helps underscore a central observation of many who have studied performance and orality.Footnote 71 Their popularity and longevity can be explained in part by their ability to be interpreted and reinterpreted to fit various present circumstances.

The song engages in what John Lonsdale calls “political tribalism”—defining a group in opposition to another—by including derogatory comments about bad body odor of Bairu neighbors, which Mbabi-Katana translated as “agriculturalists.”Footnote 72 Pastoralism, long a feature of the Rwenzori region, was frequently discussed in early ethnographic works that used the now-discredited Hamitic hypothesis’s racial theory to articulate biological distinctions and explain hierarchy between the region’s agriculturalists and pastoralists.Footnote 73 In recent years, scholars have explored the origins of this racial ideology by looking at its “multiple sources” in the work of both African intellectuals and colonial-era commentators.Footnote 74 Describing this process, Jonathan Glassman has called our attention to how African intellectuals created “new forms of ethnic thought out of indigenous cultural materials.”Footnote 75 These nanga songs provide another kind of “indigenous cultural material” that we can examine to understand how overlooked intellectuals also participated in this process.

Nanga songs that helped articulate particular identities were often also ones that came out of profound loss—whether of cattle, land, or people, during conquest and colonial rule. In his work on historical knowledge and its social role, Paul Connerton has proposed examining cases where “the process of historical change… [is one] in which wisdom has been learned only at the cost of suffering.”Footnote 76 Connerton proposes that we take seriously the mourning of “historical traumas” and the ways that “people turn to histories in order to cope with an otherwise uncontainable experience of loss.” That such narratives also contributed to community belonging also conforms with literature linking grief with identity formation.Footnote 77

Loss and grief—especially of cattle and land—are indeed central themes of many nanga songs. The nanga songs that chronicle Kabalega’s raids and its effect on women in the area lament this history—as do those criticizing Toro’s interference in Busongora during the colonial period. The regional history of land dispossession is also depicted in a nanga song that describes landscapes previously replete with cattle that have since been decimated by disease and land grabs. One nanga song described a specific gathering place for cows where numerous cows used to pass by, but laments the disease that struck the cows (zarwaara, meaning “they fell sick”).Footnote 78 As one section describes, this affected the whole community, leaving hungry children so that they “suckled their teeth” instead of being fed milk:

Bagore bazo basibire nibashasa

Bakama bazo basibire bakingire

Zarwaara

Zarwaara

Zarwaara

Abato batonka amaino

Their women/wives spent their days in pain

Their lords spent their days behind closed doors

They fell sick

They fell sick

They fell sick

The children suckled teeth

The song is as sparse in specifics as it is rich in emotion: as Gengenbach observed in her work in Mozambique, the important emphasis in these narratives is often “not what, when or where but with whom things have happened.”Footnote 79 However, following Leroy Vail and Landeg White’s approach to Tumbuka women’s songs, when placed in their historical context, nanga lyrics like these can provide their perspectives on regional history: the women who performed this song explained that it was written to depict the suffering associated with the colonial period, when a combination of diseases like sleeping sickness and colonial mismanagement devastated Busongora and its herds.Footnote 80 Colonial responses wreaked havoc on residents of the region: they allowed cattle (an identified vector of the disease) to be killed, and they forced the resettlement of populations living in swaths of land impacted by disease. They forbid herding across large portions of territory, and deprived residents of their homeland and grazing fields, some of which were later turned into Queen Elizabeth National Park.Footnote 81 Mismanaged disease resulted in estimated deaths that exceeded more than 20 percent of the people living around Lake Edward and Lake George, while scholars have described these responses to the thoroughly “colonial disease” as some of the most “disruptive colonial public health campaigns of the twentieth century.”Footnote 82

Nanga songs capture the affective dimensions of this history through both lyrics and performance: while the players usually raise their hands while performing, in this one, they bow their heads in sorrow.Footnote 83 They directly tied the creation of nanga songs to the tragedy of drought, cattle loss, and disease: “cows and people were dying and suffering, so they wrote a nanga.”Footnote 84 The songs themselves explicitly call for people to lament the past and to mourn together, thus providing time for community members to share in a public expression of grief and mourning.Footnote 85

Conversations with nanga players showed that many of the songs about Busongora’s lost land and cattle continue to be repeated because these grievances persist today.Footnote 86 When describing the nanga about a place in Busongora that “no longer belongs to Busongora,” performers listed grievances that began with colonialism but also extended into more recent conflicts with Bakonjo populations over land rights.Footnote 87 Audience members, too, then, could hear these songs and conjure up their own contemporary examples.

Nanga songs conveyed other emotions, too. Nanga players appear in brief mentions of celebratory community gatherings: Perlman described seeing “old women” who “were singing ‘enanga’ “(which he defines as “songs sung by old women”) during wedding celebrations in Bwenzi.Footnote 88 Nyakatura describes the first night when a new wife performs domestic duties in her new home as “a wonderful one” in which people “played the harp (enanga) and sang lovely songs and rejoiced very much.”Footnote 89 Akiki Nyabongo’s dissertation mentions nanga songs during a discussion of Bahima populations in Uganda, stating that “the development of the arts consists chiefly in love songs extemporized to the accompaniment of a harp.”Footnote 90 His other work also describes nanga and emphasizes the primacy of emotions in his categorizations. He includes those to praise kings, those that praise warriors, those that sympathize between wars, those for love songs, and those that he says are for cowards.Footnote 91 Interviews in 2019 also confirmed the happy nature of events known as kutarama events, at which nanga songs are often played: “A kutarama happens when people are happy.”Footnote 92 Another woman emphasized the role of love in nanga songs: “In particular, the word nanga means love… the Basongora have love for cows, can sing about loved ones.”Footnote 93

That affect and emotional responses were crucial components of these nanga was made clear by the way many informants explained these songs to me. At one point, I asked a woman if nanga songs referred to the wars fought by Kasagama—for indeed many that I heard did reference his performance in battle. Her response illustrated the importance of emotion above historical fact in these songs, even though in reality the songs contained aspects of both: “No,” she said, “they don’t talk about the wars; they talk about bravery.”Footnote 94

Highly emotive—and effective precisely because of their affective dimension—nanga songs sometimes articulated defined ideas about an in- and out-group, while other times they focused on using “indigenous cultural material” to articulate communal values and characteristics. Recent scholarship on affect in African history has underscored the potential community-forming role that affect and shared emotions can have.Footnote 95 These analyses therefore complement the intellectual histories of ethnogenesis and community identity formation. Those latter histories have been particularly focused on male intellectuals, in large part because of the kinds of written histories produced by homespun historians and later conveniently archived in universities, newspapers, and tin-truck literacy efforts.Footnote 96

Nanga songs provide alternative perspectives on these regional events as well as overlooked examples of women’s historical narratives’ role in articulating identity. These songs also chronicle the region’s history, shedding light on cattle-raising practices, wars, events, and the populations’ feelings about them—and they were crucial forms of historical education for younger generations. The women who perform them today emphasize nanga’s importance in teaching younger generations about their past: “the purpose is… to learn, educate, tell stories, communicate on the past.… It’s also an act of you teaching your family and friends, trying to transfer information from one generation to another.”Footnote 97 They provide women’s perspectives on land dispossession and environmental change—topics of increasing relevance and recent scholarly interest across the continent.Footnote 98 Their cultural significance for identity and belonging is also apparent in how they were incorporated into important elements of Busongora life: women in the region also often included painted images of nanga instruments in their famous patterns that adorned the walls of their huts.Footnote 99

Nanga in the Postindependence Period

In part because of this social importance, almost all informants lamented the loss of the nanga tradition due to formal schooling, urbanization, and new forms of entertainment. Cimardi also suggests that the practice has dwindled alongside a decline in pastoralist lifestyles and culture.Footnote 100 Many interlocutors also pointed out how the fate of nanga playing has been intertwined with that of Busongora: as colonial abuses, land displacement, and disease scattered the population, their musical traditions weakened. Despite these hardships, many pointed to the nanga as a form of community identity survival through displacement and disease. One man who lost both his parents to the sleeping sickness epidemic of the 1910s recounted his move to Congo when Queen Elizabeth National Park was established.Footnote 101 While he told me that he and his wife did not tell stories once they were in Congo—it was too sad to conjure up past memories—he said they did continue participating in and attending nanga performances.

Researchers’ fieldnotes also suggest an attrition of nanga traditions. When Peter Cook, a student of Wachsmann, came to Uganda in the 1960s to record various indigenous musical practices, he recorded many nanga songs. Several of his and Wachsmann’s recordings feature the voice of a woman performing without the nanga instrument: the notes to the recordings highlight that these are “unaccompanied.Footnote 102 We can’t know from the available evidence whether this was because nanga instruments have become increasingly rare and hard to afford in difficult economies, but several of the women I spoke with explained that the instruments are expensive and have become increasingly difficult to access.Footnote 103 The Royal Museum of Central Africa describes the original nanga instruments as rarely used now, having been replaced by a similar version of the instrument from a neighboring community.Footnote 104

Certain elements of musical performance received increased attention in the late colonial period when schools brought some local stories and folktales into the curriculum, but I found no evidence of sustained efforts to include nanga songs. Music festivals had been a feature of colonial schools, but their early iterations included only hymns and did not include what would later be labeled “traditional” Ugandan music until Wachsmann revived the festival in the 1940s and added the category.Footnote 105

After independence, the national music festival—newly titled the Uganda Schools’ Music Festival—included categories like the traditional folk song, traditional folk dance, and instrumental composition. Groups were invited from all over Uganda to perform “their” folksongs.Footnote 106 Yet as with all classifications of alleged ethnic or regional identity, the process by which groups were chosen and delineated was not always straightforward, and representation in these festivals required a formal territorial assignment. Despite repeated efforts of Busongora to achieve formal recognition, they do not have a formal territorial assignment under the Ugandan government.Footnote 107 As a result, as Cimardi summarizes it, “Basongora’s musical traditions—so special because of the women’s role in singing accompanied by the through zither nanga—were and are not yet represented in the school music festival.”Footnote 108

Despite (or likely because of) this neglect, Busongora nanga players have begun seeking greater recognition for their craft. The nanga group I interviewed for this research recently began touring in various parts of the country. The results of their efforts—as well as their partnerships with international and cultural organizations—have meant that nanga songs have reappeared as prominent historical narratives.

A local nonprofit, Engabu Za Toro, targets cultural preservation efforts and has embraced the ancient figure of Koogere, as narrated by nanga songs, as one that speaks to contemporary concerns. Koogere appears frequently in accounts of Kitara’s early history alongside other characters described as part of the Tembuzi or subsequent Cwezi dynasties.Footnote 109 Renee Louise Tantala points out that the name of Koogere appears to be a title rather than a name of a specific person—and though she’s often portrayed as a queen, Koogere (and her contemporaries) were more likely public healers, looked to for community well-being and vitality.Footnote 110

In 2015, Engabu Za Toro successfully nominated what they call the “Koogere oral tradition of the Basongora, Banyabindi, and BaToro peoples,” to be included on UNESCO’s “list of intangible cultural heritage in need of urgent safeguarding,” which recognizes intangible cultural heritage “as a mainspring of cultural diversity and a guarantee of sustainable development.”Footnote 111 Engabu Za Toro’s nomination form focused on aspects of nanga playing and storytelling that fit these developmentalist goals, describing Koogere as “a great woman ruler and entrepreneur” whose life shows the “capacity of women in handling social issues and their elevated status in society.”Footnote 112 These efforts likely shaped my interviews in 2019: every time I spoke with a nanga player, Koogere was the first topic mentioned. Often, when pressed about Koogere songs they heard growing up, they did not remember specifics.

The renovation of nanga narratives to emphasize Koogere’s feminist credentials is perhaps just the most recent example of how nanga songs can use history to promote particular identities and causes—and of how these public performances are reshaped in the context of contemporary concerns. Whereas nanga songs of the colonial period lamented cattle loss and disease, performances in recent years have emphasized contemporary conflicts around land access, gender equity, and political representation. What remains consistent, though, is that women nanga players continue to serve as public intellectuals, with social and intellectual influence worthy of further study.

Conclusion

Nanga songs and their intellectual historical content have played important roles in shaping communal identity—whether that identity centered around pastoralism, communal mourning, gendered norms, or women’s empowerment. The songs both complemented and supplemented intellectual material produced by their intellectual male counterparts. In the Toro royal courts, they emphasized centralized kingdoms and their authority—serving a purpose akin to what Connerton describes as “histories of legitimation.”Footnote 113 In the plains of Busongora, they highlighted social and environmental histories, providing a crucial counterpart to the contemporary colonial archives. Though scholars writing about the roots of today’s historical profession often discuss how the social history turn and “history from below” are products of recent intellectual trends, this article reminds us that these kinds of historical narratives were produced through nanga songs around campfires and community festivals in the Global South long before Europe and the United States purportedly discovered them in the latter half of the twentieth century.

By focusing on these nanga songs, we can better understand how Ugandan women understood—and helped their communities through—regional crises and global events, including disease epidemics, state consolidation, migration, demographic changes, colonialism, and environmental change. Emphasizing this educative potential of women’s knowledge also helps us understand women’s role in navigating global events and imperial encounters—from colonialism to climate change. For as recent studies in global gender history have shown, women often shaped the trajectory of global, colonial, and imperial negotiations. Analyses of these encounters emphasize the role of women’s bodies, networks, male relations, and consumption habits in shaping events in places ranging from Texas borderlands to the Cape of Good Hope to the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 114 Yet little attention has been paid to the influence of women’s intellectual undertakings, and even fewer studies consider the intellectual aptitude of non-Western women, as Bonnie Smith did for female historians in the United States.Footnote 115 A focus on these songs therefore reintegrates women—including women not equipped with literacy or elite education—into accounts of imperial and intellectual history.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Busongora nanga group (made up of Beatrice Mande, Joyce Muyogo Ninabrorongo, Jessica Kemigisa, Jane Ruyenje, and Mary Mbabazi) and Stephen Mugabo for first introducing me to these songs. Thank you to colleagues and friends David Schoenbrun, Sean Hanretta, Jonathon Glassman, Linda Cimardi, Christopher Muhoozi, Rebecca Rwakabukoza, and co-panelists and participants at an ASA panel on “Producing Gendered Historical Knowledge” and Northwestern’s Chabraja Center Historical Studies conference on “Crisis and Collapse in History” for their comments and guidance. Funding from Northwestern University and Fulbright IIE made this research possible. Finally, thank you to the journal editors and two generous anonymous readers for the helpful feedback.