In this book we investigate variation and change in intensifier usage in Late Modern English (LModE), more specifically in a setting where one’s life can be at stake and where every word may count, namely in the courtroom at the Old Bailey in London. A variety of factors are at work in such speech situations, among them the speaker’s role in the judicial procedure (whether a defendant, witness, victim, lawyer, or judge), the speaker’s sociohistorical background (e.g., their gender and social class), and, not least, the strategic choices they make to convey their message in the most forceful way possible to serve their purposes. Thus, for instance, the defence’s stance on aggravating evidence presented could be to belittle it, as in example (1) with two instances of the booster very. Refuting this, the prosecution can hit back, persisting on the seriousness of offences, as in example (2) with the maximizers extremely and infinitely (for further discussion, see Chapter 10).

(1) The letter being found in the office, shews they thought it of very little importance: and let me add too, they thought of very little importance the other letters that had been sent; (t17810711-1,Footnote 1 lawyer, m, higher)

(2) I do not say that is proved upon De la Motte: I only say that such a thing has happened; and it is obvious that such intelligence must be extremely important to the enemies of this country, and infinitely detrimental to us. (t17810711-1, lawyer, m, higher)

Intensifiers are not exactly an understudied field. Searches in the MLA bibliography at present yield 112 items with ‘intensifier/s’ in the title and 372 hits with ‘intensifier’ as a subject term (searched on 31 December 2022). A seminal work by Bolinger (Degree words, 1972) has been devoted to the entire field of intensification in Modern English, while Reference PetersPeters (1993) has provided a long-scale historical treatment of boosters, a subtype of amplifying intensifiers. A spate of articles has covered recent developments of intensifiers in various varieties (e.g., Reference Ito and TagliamonteIto and Tagliamonte 2003; Reference Tagliamonte and RobertsTagliamonte and Roberts 2005; Reference TagliamonteTagliamonte 2008; Reference Barnfield and BuchstallerBarnfield and Buchstaller 2010; Reference Fuchs, Ulrike and PichlerFuchs and Gut 2016; Reference Hessner and GawlitzekHessner and Gawlitzek 2017, just to name a few) as well as their historical changes (e.g., Reference Méndez-NayaMéndez-Naya 2008; Reference Méndez-Naya, Pahta, Taavitsainen and PahtaMéndez-Naya and Pahta 2010; Reference Nevalainen, Rissanen, Tyrkkö, Timofeeva and SaleniusNevalainen and Rissanen 2013). In spite of this, there are still very significant gaps in our knowledge of intensifiers and particularly their history. The aim of the present volume is to fill a few of these gaps.

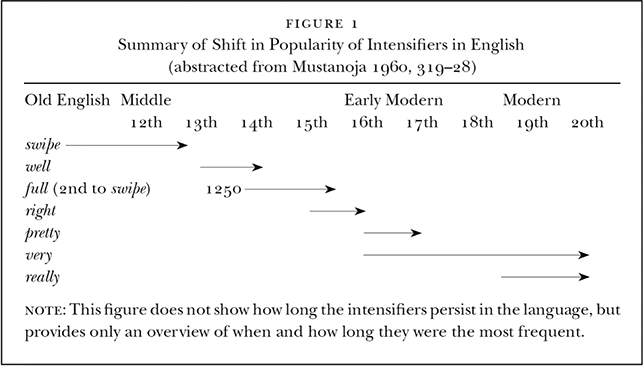

Intensifiers are of linguistic interest for various reasons. One is their behaviour in language change, the intensifier area having been subject to an often quoted ‘fevered invention and competition’ (Reference BolingerBolinger 1972: 18) across time. Reference Tagliamonte and RobertsTagliamonte and Roberts (2005: 282), drawing on Reference MustanojaMustanoja (1960: 319–28), and on Reference Ito and TagliamonteIto and Tagliamonte (2003: 260), have shown the resulting overhaul of prominent and fashionable intensifier items in a nutshell in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Popular intensifiers across time

While some intensifiers become extinct (e.g., swiþe), others wax and wane, undergoing revivals (e.g., well, even if not thus depicted in Figure 1.1) and still others have an extremely long life (e.g., very). Very, really, and pretty from Figure 1.1 also show up in the top-five items in most modern sociolinguistic research on intensifiers, as in Table 1.1 from Reference WagnerWagner (2017: 65); another ubiquitous top-runner there is so. Other items among the twelve items contained in these lists are more restricted as to popularity in certain varieties (e.g., absolutely, bloody (both British English), dead (Tyneside English), just (Canadian English), quite (New Zealand English)) or at certain times (e.g., rather (1960s), totally (1990s)).

Table 1.1 Intensifier ranks in different studies (from Reference WagnerWagner 2017: 65)Footnote 3

While Table 1.1 shows both stability (especially very, really, so) and variation, Reference PetersPeters (1993) more drastically documents the great changes in the boosters inventory over the history of English. Regarding intensifier types, he documents a clear rise from 55 items in Old English (OE) via 86 in Middle English (ME) to 168 in Early Modern English (EModE).Footnote 4 The source domains of intensifiers are shown to diversify as well, for example, with items originally from the domains ‘terrible’ and ‘excess’ (cf. example (2) above) becoming more relevant in EModE (Reference PetersPeters 1993: 275).

Although Reference PetersPeters (1993) covers the history of English, his study nevertheless reveals an omission: between his last EModE letter collection from 1614 to 1629 and the twentieth-century conversations from, for example, the London-Lund Corpus, there is no LModE data (and his eighteenth-century data is taken from OED examples). This is not specific to Reference PetersPeters (1993), but characteristic of most intensifier research: there are studies on intensifiers or intensification in OE (e.g., Reference LenkerLenker 2008; Reference Méndez-NayaMéndez-Naya 2021), in ME (e.g., Reference Pahta, Dossena and TaavitsainenPahta 2006a; Reference LenkerLenker 2008), and in EModE (e.g., Reference Peters and KastovskyPeters 1994; Reference NevalainenNevalainen 2008; Reference Nevalainen, Rissanen, Tyrkkö, Timofeeva and SaleniusNevalainen and Rissanen 2013), but papers on LModE are still rare and mostly deal with specific individual authors and/or only a part of the period (Reference BrorströmBrorström 1987 on Jonathan Swift, Reference Clifford-AmosClifford-Amos 1995 on Jane Austen, Reference CacchianiCacchiani 2006 on Samuel Johnson’s dictionary, and Reference HiltunenHiltunen 2021 on the eighteenth century). It is exactly this gap that the data of the present work will fill, as our data from the Old Bailey courtroom collected in the Old Bailey Corpus (version 2.0, henceforth the OBC) covers the period from 1720 to 1913. This data, spanning almost 200 years, allows both close-up synchronic snapshots as well as charting language change in real time.

The expressive need of speakers apparently driving the inventiveness and resulting variation mentioned above stands in some contrast to the observation by Reference TagliamonteTagliamonte (2016: 82) that ‘the vast majority of the time people don’t use intensifiers at all, even though they could’, or in other words that intensifiers are in fact relatively infrequent overall. However, the infrequency points to the important aspect of choice: speakers use intensifiers when it suits their purposes in communicative contexts, such as expressing their emotive stance more forcefully, sounding more convinced and thus also more persuasive. Due to this aspect, intensifiers are also distributed differently across communicative contexts. In Reference BiberBiber’s (1988: 106, 247–69) multidimensional analysis, amplifiers are found to be characteristic of more oral and more involved contexts, which has also been corroborated by further research (e.g., Reference VartiainenVartiainen 2021: 246). This makes our speech-based courtroom data a promising source, although the involvement that can be expected by attitudes to the crime and the high stakes for some courtroom participants is moderated by the overall formality of the situation. Intensifiers generally and in this context are often not necessary, but they are interesting speaker choices. In (3), for example, only items (a) and (f) cause an important propositional effect (i.e., are necessary), while (b)–(e) rather add to a general impression of the speaker’s attitude. Here, a doctor giving testimony on a dead patient, a probable murder victim, is clearly keen on presenting things as not being out of the ordinary.

(3) I told Miss Barrow if she did not take her medicine I should have to send her into the hospital. She was (a) somewhat deaf, but understood me. The sickness continued, but the diarrhoea was not (b) so bad. […] Her mental condition was never (c) very good. Nothing was said about her making a will. She was (d) quite capable of doing that if it was properly explained to her. […] While I attended her the temperature was up to 101 deg. on one day; other days (e) fairly normal, or (f) a little up. (t19120227-48, witness, m, higher)Footnote 5

The sociopragmatic annotation of the OBC allows focusing in on speaker groups such as defendants, lawyers, women, or lower-class speakers. The male, higher-class witness in (3) thus contributes to insights into not only the sociolinguistic categories of gender and class but also into the sociopragmatic category of speakers’ roles in the courtroom. While gender has played a role in many intensifier studies, consideration of class has been very rare (Reference MacaulayMacaulay 2002) and the study of speakers’ functional roles virtually non-existent.

Almost all the studies referenced so far have taken clearly delimited foci on intensifiers, be they on specific lexemes, on subgroups of intensifiers such as amplifiers, or on the specific context of the intensification of adjectives. In contrast, the approach taken in the present study is more comprehensive, targeting a wide range of intensifiers across the degree spectrum from amplifying to downtoning. Downtoners, in particular, have not received much attention in the literature so far (some exceptions are Reference Rissanen, Hasselgård and OksefjellRissanen 1999b, Reference Rissanen2008a; Reference BrintonBrinton 2021; Reference Claridge, Jonsson and KytöClaridge, Jonsson, and Kytö 2021). As individual intensifiers will provide the entry point in this study, the intensified contexts remain unrestricted up front. This allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how intensification operates in language use. In line with our focus on usage patterns, the semantic change and grammaticalization undergone by intensifiers will not be the centre of attention in this study (cf., e.g., Reference Breban and DavidseBreban and Davidse 2016, on the development of very).

Researching a wide range of intensifiers in the authentic, speech-based as well as specialized legal courtroom context of the late modern period in England will allow us to delve into and answer the following research questions:

1. How frequent are intensifiers in Late Modern British English? How many or how few speakers use them?

2. What is the inventory of intensifiers, that is, which forms occur at all and how are they distributed across subgroups such as maximizers, boosters, and downtoners? Which of those forms gain ground and which forms are on their way out? This may help establish links from our data to findings on earlier and later periods.

3. What targets do speakers in the courtroom modify by using intensifiers? Are adjectives indeed the most important targets, as previous literature implies? What do the targets indicate about the intensifier types or about the specifics of the communicative context?

4. How restricted or flexible are individual intensifier types, that is, are there specific collocational preferences and do these change over time? Recent research (e.g., Reference WagnerWagner 2017) has pointed to the relevance of highly bonded intensifier-target combinations.

5. What are the distributions of the forms across speaker groups?

a. In terms of speakers’ functional roles (e.g., judge, witness), thus providing a first subregister profile of intensifier usage in spoken legal discourse.

b. In terms of speakers’ social characteristics (gender and social class), thus complementing and expanding on previous sociolinguistic intensifier research.

We will address the above questions across the upcoming chapters as follows: Questions 1 and 2 are answered in descriptive terms in Chapters 5 (maximizers), 6 (boosters), and 7 (downtoners), and within a multivariate statistical framework in Chapter 8. Questions 3 and 4 will also be considered in Chapters 5, 6, and 7. Question 5 is of major interest to the study and will be addressed, in particular, in Chapters 9, 10, and 11.

We conclude the present chapter by providing a survey of the structure and organization of the book. Chapter 2 is devoted to the theoretical and methodological issues relevant to the study. The material and the corpus linguistic approach are introduced along with the analytical framework of historical (socio)pragmatics, as well as the implications of the courtroom setting and the use of records of past spoken interaction as data. We also discuss how our investigation relates to the study of language variation and change, and of grammaticalization and pragmatic-semantic change. In Chapter 3, we deal with the notions of intensification, degree, and related phenomena, and discuss the forms, features, and functions of the items we have included in our analyses. We also present the classification of intensifiers we have adopted for the study, that is, amplifiers comprising maximizers and boosters, and downtoners comprising moderators, diminishers, and minimizers, and introduce the principles we apply to classify their meanings as well as syntactic and lexical patterns. The chapter concludes with a discussion of pragmatic contexts and functions of intensifiers and a summary of the characteristics of our intensifiers and their contexts of use.

In Chapter 4, we drill deeper into the background and characteristics of the source of our data, the OBC, and discuss the principles of our data retrieval and screening criteria. We also present an overview of our data, the nearly 65,000 intensifier tokens we identified in the OBC for inclusion in the study and trace the diachronic development of the full inventory of our items across the 200 years covered by the corpus. After presenting the sociobiographic distribution and word counts of the speakers in the OBC, we take a closer look at the distribution of our intensifiers across the speakers’ gender and social class within the descriptive statistics framework, and also briefly introduce the regression model, or the inferential, multivariate statistical method to be used to disentangle the complex interplay of the sociopragmatic variables of our speakers (time, gender, social class, and the role of the speaker in the courtroom).

Chapters 5, 6, and 7 are devoted to the descriptive findings for our maximizers, boosters, and downtoners, respectively. The chapters start with an inventory of forms comprising an overview of types and tokens, followed by a survey of dual forms, that is, suffixed and suffixless forms. We then describe the semantic inventory of the respective intensifier categories and discuss the semantic input domains and the developmental trajectories of the items. The remainder of each of the three chapters is devoted to the targets of intensification and their collocational features. We look at the general word-class targets and pay attention to the better-represented word classes, among them adjectives and verbs. We also look into the targets of the dual-form words and into the collocates and semantic prosodies of the top-frequency items.

In Chapter 8, we present the results of our regression analysis, displaying the distribution of intensifiers across time and the groups of speakers. The model enables us to estimate the unique contribution of each of our four predictors (time, speaker role, gender, and social class) irrespective of the other predictors, which are held constant. We trace back the diachronic development of intensifiers as a full set and within the categories of maximizers, boosters, and downtoners. We also show which speaker categories use which kind of intensifiers. In Chapter 9, we probe further into the diachrony of development of our intensifiers and their usage across the intensifier categories, time, and the speaker groups. We look into possible factors that might account for the trends of development attested, among them various collocational features, the possible role played by the foreign origin of the terms, the potential interference on the part of the scribes taking down the notes, and stylistic shifts shaping the records for publication. We also look into and explain a few interaction effects of time on the sociopragmatic variables (role, gender, and class) detected with the help of a supplementary regression model.

Chapter 10 zooms in on the discourse-pragmatic functions served by our intensifiers in courtroom interaction. Our discussion revolves around such central phenomena as trials as an activity type with norms and a clearly structured sequence of events to constrain the interaction among the participants. We discuss the specifics of the intensifier usage of victims, defendants, witnesses, lawyers, and judges, all categories with vastly varying representation in the material and varying rates of use across our three intensifier categories. We also present a case study of closing speeches of the defence and prosecution to show how our intensifiers can be used strategically in the interaction between the two opposing interlocutor parties.

In Chapter 11, we turn to the sociolinguistics of intensifier usage. We survey aspects of gender ideology and social stratification in late modern England, outlining differences and similarities regarding gender and class between then and today. We then discuss to what extent such differences may account for the differences attested between the use of intensifiers in the Old Bailey courtroom and the regularities attested for present-day usage in previous research, factoring in differences in societal structures as a contributing factor. We study the exclusive or near-exclusive patterns of intensifier use by male and female speakers; such patterns could be taken to reflect gender-based usage preferences. We then turn to intensifier usage across the social classes distinguished for the OBC and relate our findings to those presented for modern speakers.

In Chapter 12, we summarize the answers to our research questions and view our results in the context of research on intensifiers. We also return to the Old Bailey courtroom to discuss a type of cases where intensifiers contribute to the dynamics of courtroom discourse in a particularly poignant way. Finally, we briefly survey prospects for further study in the area.