The speed, geographic reach, and volume of human mobility have radically accelerated in the past five centuries. Further, mobility in the modern era is rarely unidirectional; dense webs and recursive loops enable some social actors to develop and maintain multiple “home bases” and cultivate spatially extensive relationships. Archaeological research on diaspora communities poses specific challenges, because transnational kinship networks, social organizations, property ownership, and economic remittances create distributed material footprints. In diasporic contexts, archaeologists investigating single locales capture only fractions of the material worlds of the people they study.

This study contributes to the archaeology of diaspora through an investigation of a nineteenth-century Chinese qiaoxiang (桥乡; migrants’ home village) in the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong Province. Through collaboration among archaeologists, historians, architectural historians, and folk life specialists in the United States and China, we interrogate the relationship between “home” and material practices. Specifically, we compare the material culture recovered from the qiaoxiang with the results of archaeological investigations of Chinese diaspora communities in the United States.

Archaeologists often interpret the presence of China-produced material culture in diaspora contexts as evidence of continuity with Chinese tradition and the maintenance of Chinese identity. However, our research reveals that China-produced goods found in US Chinese diaspora sites were not always the same as those in qiaoxiang. Nonstate actors, especially import-export firms called jinshanzhuang (金山庄; Gold Mountain firms), played a powerful role in creating difference between the material worlds of qiaoxiang and those in the diaspora. Additionally, qiaoxiang residents also participated in transnational flows of material culture, as evidenced by the presence of products manufactured in the United States and Europe. Interethnic collaborations in the diaspora also generated new cultural forms that circulated back to qiaoxiang. We analyze these findings to propose a multidimensional framework for the transnational analysis of the materiality of diaspora communities, in both migrants’ originating homelands and their new homes in their adopted countries.

Homeland Research in the Archaeology of Diaspora

Although the term diaspora was originally applied to Jews expelled from the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, since the 1960s the concept has expanded to include other populations that are dispersed from a small homeland, resettled in multiple international locations, and linked by a shared sense of identity maintained in reference to their former homeland. Diasporas may be generated through involuntary causes (exile, enslavement, natural disasters, famine, and political or religious persecution) as well as through volitional migrations to flee difficult political, economic, and social conditions.

Most archaeological research on diaspora focuses on international migrants in the Americas, Australia, and other settler colonies and postcolonies. Cipolla's (Reference Cipolla2013) research on the identity formation and migration of the Brothertown Indians demonstrates that diaspora can also be productively used to understand relocations within national borders. Lilley (Reference Lilley2006) suggests that the shared experience of displacement may provide a methodological foundation for integrating archaeological research on indigenous, enslaved, settler, and immigrant populations in colonial and postcolonial contexts.

The archaeology of diasporic homelands first developed in research on the African diaspora, and it includes the cultural and geographic roots of enslaved Africans and Afro-descendants and the routes taken during forced transport. The initial focus on identifying “Africanisms” has expanded to include investigations of how the slave trade impacted political, cultural, and economic formations of West African societies. This provides important information about the formation of political power in coastal African states, the material and spiritual practices of communities targeted by slavers, historical changes in daily life in rural African villages, and the impact of enslavement on those who remained (Blakey Reference Blakey2001; DeCorse Reference DeCorse1992, Reference DeCorse2001; Hicks Reference Hicks2005; Kelley Reference Kelley, Reid and Lane2004, Reference Kelley, Mitchell and Lane2013; Monroe Reference Monroe2011, Reference Monroe2013; Ogundiran and Falola Reference Ogundiran and Falola2007; Schramm Reference Schramm, de Jong and Rowlands2007; Singleton Reference Singleton1995; Stahl Reference Stahl, Ogundiran and Falola2007). Brighton's (Reference Brighton2009) transnational investigation of the Irish diaspora provides an example of research on voluntary migration under conditions of economic and political duress. Brighton compares artifacts from archaeological deposits in Ballykilcline, Ireland, with those from Irish diaspora households in Patterson, New Jersey, and New York City, New York, to trace the “diachronic relationality” of material practices across homeland and diaspora communities, calling attention to internal differences within diaspora communities.

Until the present study, archaeological research on the Chinese diaspora focused exclusively on diasporic settlements, giving little attention to the specifics of migration and change in China itself. Emigration from southeast China began in the 1600s with large-scale resettlement to South Asia and eastern Africa. In the nineteenth century, more than 2.5 million additional Chinese resettled to locations throughout the world (Pan Reference Pan1999). Most of those who migrated to the United States came from the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong Province (Figure 1; Hsu Reference Hsu2000; Takaki Reference Takaki1998). Chinn and associates’ (Reference Chinn, Lai and Choy1969:20) analysis of the geographic origins of Chinese migrants in California estimated that by 1876, 82% (124,000) were from the Siyi (四邑; Four Counties) District, composed of Taishan, Kaiping, Xinhui, and Enping Counties; 7.9% (12,000) were from nearby Zhongshan County; and 7.3% (11,000) were from the Sanyi (三邑; Three Counties) District, composed of Nanhai, Panyu, and Shunde Counties (Figure 2). The remaining 2.8% (4,300) were ethnic Hakkas, most likely from Heshan County. These figures are likely indicative of the general proportions of geographic origins for nineteenth-century Chinese migrants throughout the United States.

Figure 1. Map of China showing Guangdong Province (drawing by Katie Johnson).

Figure 2. Map of the Guangzhou region showing Siyi (Four Counties area), Sanyi (Three Counties area), and Zhongshan County (drawing by Stella D'Oro and Katie Johnson; adapted from Hsu Reference Hsu2000:Map 1; Pan Reference Pan1999:Map 1.9).

The global dispersal of Pearl River Delta residents resulted in part from religious, economic, and military European imperialism. The British Opium Wars (1839–1842 and 1856–1860) resulted in massive internal displacement as coastal residents were forced inland. The concurrent Punti-Hakka Wars (1855–1867) further destabilized the region. Financial crises, floods, and crop failures intensified rural poverty. Such conditions made the prospect of better wages and business opportunities abroad attractive to people who were struggling to survive. The region's connections with international markets via Hong Kong, Macao, and Guangzhou made massive out-migration possible (Chang Reference Chang2003:1–19, 30–33; Hsu Reference Hsu2000:17–18; Kuhn Reference Kuhn2008; Liu Reference Liu2004; Pan Reference Pan1999; Takaki Reference Takaki1998:31–42).

Whether nineteenth-century migrants from China should be characterized as living in “diaspora” is debated. Some scholars raise concerns that the diaspora concept homogenizes the diversity of experiences of Chinese migrants and disregards new identities formed outside of China. Ross (Reference Ross2013a, Reference Ross2017) suggests that the diaspora concept can be productively applied to ethnic Chinese communities living outside of China

if we view diaspora as a process rather than a fixed ethnicity and approach it in a comparative manner that seeks to explore difference as well as similarity . . . and recognize the role of both ancestral and adopted homes in defining one's sense of self [2017: 10–11].

Although archaeologists have studied Chinese diaspora settlements for more than 50 years (Ross Reference Ross and Smith2013b; Staski Reference Staski, Majewski and Gaimster2009; Voss Reference Voss2015; Voss and Allen Reference Voss and Allen2008), until the present study there have been no comparable investigations of qiaoxiang. In this absence, most archaeological studies of Chinese diaspora communities have interpreted artifacts through concepts such as acculturation, tradition, ethnic boundary maintenance, syncretism, hybridity, and identity. These interpretations often rely on generalized and at times stereotyped notions of “Chineseness” that are used as a reference point for interpreting recovered materials. Transnational approaches that build on historic and ethnohistoric research have provided alternatives to conventional studies of change and continuity (e.g., Byrne Reference Byrne2016; Chung and Wegars Reference Chung and Wegars2005; Fong Reference Fong2013; González-Tennant Reference González-Tennant2011; Heffner Reference Heffner2015; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2015; Kraus-Friedberg Reference Kraus-Friedberg2008; Lydon Reference Lydon1999; Molenda Reference Molenda2015a, Reference Molenda, Leone and Knauf2015b; Ross Reference Ross2011a, Reference Ross2013a; Voss Reference Voss2016), but the absence of comparable archaeological data from qiaoxiang continues to hamper development of the field. Interpreting Chinese diaspora sites requires both the development of a comparable body of evidence from qiaoxiang and an understanding of the ways in which China-produced goods were distributed to diaspora communities.

Nonstate Actors in the Nineteenth-Century Chinese Diaspora

Scholars in Asian American studies and qiaoxiang studies have pointed to the centrality of nonstate actors, including clans, mutual aid associations, and jinshanzhuang, in the formation and maintenance of both qiaoxiang and Chinese diaspora communities. The settling of the Pearl River Delta by Han Chinese during circa AD 500–1300 was accomplished largely through clan-based expansion, with each new agricultural village associated with a particular clan. Patrilocal residence patterns have prevailed, with sons typically inheriting houses and land rights and daughters marrying into villages established by other clans. In this manner multigenerational households are connected to the village's ancestral founder and to other clan villages. Villages are not only places of residence for the living but also sites for honoring clan and family ancestors. The common idiom luo ye gui gen (落葉歸根; falling leaves return to their roots) expresses the ideology that clan members remain connected to their ancestral villages, regardless of how far away they may live (Faure Reference Faure1986, Reference Faure2007; Faure and Siu Reference Faure and Siu1995; Watson and Ebrey Reference Watson and Ebrey1991; Wolf Reference Wolf1980).

International migration from the Pearl River Delta in the nineteenth century can be understood as a strategy for ensuring the continuity of clan life in the face of military invasions and political and economic stress. Migrants extended the social and economic reach of the clan internationally, adapting practices used in clan territorial expansions in earlier eras. Clans developed new mutual aid associations—gongsuo (公馆; kinship associations), huiguan (会馆; district or “native place” associations), and sometimes smaller fang (房; subclan associations)—that supported migrants in foreign settings and kept migrants connected to their home villages. In the diaspora, these associations welcomed new arrivals, provided short-term room and board, connected migrants with employers, and provided venues for socializing and worship. Fang and huiguan were also models for other non-kin-based mutual aid institutions in the Chinese diaspora, including tongs (堂; business associations) as well as fraternal organizations, occupational guilds, burial associations, and political advocacy groups such as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (Liu Reference Liu1998; Mei and Guan Reference Zefeng2010; Pan Reference Pan1990, Reference Pan1999; Wang Reference Ke2011).

While mutual aid associations fostered a dynamic and recursive transnational flow of information, jinshanzhuang were for-profit import-export firms that moved people, materials, and money between China and the Chinese diaspora. Anchored in Hong Kong, these companies had branches in port cities throughout the world and also supported extensive land-based mercantile networks that stretched throughout the Pearl River Delta and to inland settlements wherever large numbers of Chinese migrants settled. Along with delivering China-produced goods to diaspora communities and shipping commodities produced in the diaspora back to China, jinshanzhuang served as emigration brokers and labor recruiters; delivered mail, newspapers, and magazines; and provided banking services to both qiaoxiang and diaspora communities, especially offering financing for migrants’ passage fees and transmitting remittances from migrants back to qiaoxiang. Fang and huiguan also depended on jinshanzhuang to maintain connections between qiaoxiang and clan members in the diaspora. Jinshanzhuang and their affiliated suppliers and merchants operated in spaces of power and charity (Sinn Reference Sinn2003), both profiting from and sustaining the lives of Chinese migrants throughout the world (Chan Reference Chan2005; Hsu Reference Hsu2000:34–40, Reference Hsu and Chan2005; Pan Reference Pan1999; Sinn Reference Sinn, Gabaccia and Hoerder2001, Reference Sinn2003).

Although archaeologists have acknowledged the role of jinshanzhuang (e.g., Sando and Felton Reference Sando, Felton and Wegars1993), their full impact on migrants’ material worlds remains critically understudied. However, recent comparative research for the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project indicates that at times jinshanzhuang and their associated mercantile distribution networks exerted quasi-monopolistic control of trade in Chinese diaspora settlements, especially in rural and frontier work camps (Voss Reference Voss2018a, Reference Voss, Chang and Fishkin2018b). Thus, interpretations of artifacts recovered from Chinese diaspora settlements must consider the interplay between the influence exerted by nonstate actors such as jinshanzhuang and cultural factors such as tradition and ethnic or national identities.

Qiaoxiang as Transnational Communities

Although qiaoxiang is commonly translated as “migrants’ home villages,” the term more precisely references the transformation of village life due to emigration. Three common characteristics of qiaoxiang are (1) the transformation of kinship structures resulting from the out-migration of large numbers of boys and young men, (2) economic dependence on remittances, and (3) the transformation of the built environment through remittances and new aesthetic influences and spatial practices.

The transformation of kinship structures in rural villages resulted from the out-migration of primarily men and boys, the desire to maintain patrilocal and clan-based residence patterns, and the effects of racist immigration laws that restricted Chinese women's immigration to the United States and other countries. Many Chinese migrants formed transnational “split households,” created by marriages between men living abroad and women residing in qiaoxiang. The husband living abroad sent remittances to support his wife, their children, and extended family and clan members. If the husband could not return to sire children himself, his wife could adopt children to maintain the husband's family and clan lineage. Often, grown male offspring joined their fathers overseas, forming intergenerational ladders of split households (Hsu Reference Hsu2000; Peffer Reference Peffer1999; Yung Reference Yung1995).

Remittances not only supported families but also contributed to village- and clan-level infrastructure, including mansions, ancestral halls, diaolou (碉楼; watchtowers), schools, hospitals, roads, railroads, and irrigation and electrification projects. The resulting transformation of the built environment included both technological and aesthetic innovations, fusing local Chinese traditions with international influences (Tan Reference Tan2013a, Reference Tan2013b). In Kaiping County, where Cangdong Village is located, the resulting distinctive landscape has been designated the Kaiping Diaolou and Villages District, a UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2014) World Heritage Site.

Just as Chinese diaspora communities remained connected to home villages through mutual aid associations and jinshanzhuang, qiaoxiang residents were equally enmeshed in long-distance kinship- and clan-based networks that extended throughout the world. The high rates of migration from the region normalized transnational relationships as routine aspects of daily life. These relationships contributed to distinctive identities simultaneously rooted in the Pearl River Delta and abroad, a dynamic that mirrored the experiences of those living in diaspora.

Toward the Archaeology of Qiaoxiang: The Cangdong Village Archaeology Project

Cangdong Village (仓东村) is a qiaoxiang located in the Siyi area, in Kaiping County, Guangdong Province (Figure 3). It was established about 740 years ago by Xie Rongshan (谢荣山), a member of the Xie (谢) Clan, as Cangqian Village (仓前村). After three generations, Cangqian Village was divided into two connected sections, Cangxi (仓西) and Cangdong (仓东). Cangdong Village is also considered to be the ancestral home of about 50 other Xie Clan villages in the region. The present Cangdong Village head, Mr. Xie Xuenuan (谢雪暖), is the thirtieth lineal descendant of Xie Rongshan.

Figure 3. Cangdong Village (photo courtesy of the Cangdong Village Archaeology Project).

In the early nineteenth century, the village housed approximately 400 residents; however, international and internal migration reduced the permanent population to around 50 to 60 people by the early 1900s. Remittance payments from abroad enabled the construction of new homes, ancestral halls, and village infrastructure, along with a regional market and multiple area schools. Both historically and today, Cangdong Village has been a center for returning Xie Clan migrants and their descendants who come to the village to visit relatives, see their family home, and honor their ancestors (Tan Reference Tan2013a, Reference Tan2013c). Cangdong Village is also the site of the Cangdong Village Heritage Education Project, which researches and interprets qiaoxiang history and culture (Tan Reference Tan2013c).

The Cangdong Village Archaeology Project was developed to bring archaeology to qiaoxiang research and to bring qiaoxiang research to Chinese diaspora archaeology. The first field project, conducted in December 2016, was a pedestrian survey and artifact collection (Voss and Kennedy Reference Voss and Kennedy2017). Survey focused on open areas between houses and other buildings, as well as the forested hillside behind the village. Historic maps, village archives, oral history, and interviews with village residents provided information about historic and modern land-use practices. In consultation with village head Mr. Xie Xuenuan, researchers defined seven survey zones ranging in size from 40 m2 to 1,272 m2, totaling 2,677 m2 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Map of Cangdong Village showing boundaries of all survey zones (adapted from Voss and Kennedy Reference Voss and Kennedy2017:Map 3.1).

In each zone, archaeologists walked transects spaced at 2 m across each survey zone and observed the ground surface for the presence of artifacts or archaeological features. Artifacts were individually mapped and collected from low-density areas (<5 artifacts/m2). In high-density areas with >5 artifacts/m2, archaeologists established a 2-×-2-m grid and collected artifacts within each grid square. In order to maximize the collection of diagnostic historic (pre-1949) artifacts, archaeologists collected (1) all household and tableware ceramic sherds; (2) rim sherds, base sherds, and large (>5 cm diameter) body sherds of ceramic storage vessels; (3) glass bottle finishes, bases, mold seam shards, and shards with labels; (4) shell and animal bone that appeared to be historic in origin; and (5) any other potentially diagnostic historic artifacts, including metal tool fragments, glass objects, and mineral artifacts such as slate tablets.

A total of 1,071 archaeological specimens, weighing 47,111 g, were collected during the archaeological surface survey of Cangdong Village (Table 1). The collected artifacts date from the seventeenth century to the present day, including the late Qing dynasty (ca. AD 1800–1912), when international migration was at its peak, and the Republic of China (AD 1912–1949), the period when diaspora communities were most heavily investing in qiaoxiang. Over 90% (n = 967) of the collected artifacts were ceramic sherds from tableware and storage vessels. The preponderance of ceramics is unsurprising, given that organic materials rapidly decompose in open-air conditions and glass and metal objects are commonly reused or recycled. As a result, the collected artifact assemblage strongly represents food-related material practices. Additionally, historic glass artifacts, although few in number, represent material practices related to medicine and grooming.

Table 1. Quantity of Collected Artifacts by Survey Zone.

Transnational Analysis of Collected Artifacts

For the purposes of transnational analysis, the artifacts collected during the December 2016 survey are considered a single, site-level assemblage. This approach reveals broad trends in qiaoxiang material practices that can be generally compared with those from Chinese diaspora sites abroad. Specific comparisons are also made with the San Jose, California, Market Street Chinatown (Voss et al. Reference Voss, Kwock, Yu, Gong-Guy, Bray and Kane2013) and with archaeological evidence aggregated for the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project (Maniery et al. Reference Maniery, Allen and Heffner2016; Voss Reference Voss2015, Reference Voss2018a, Reference Voss, Chang and Fishkin2018b). Living in a large urban settlement close to San Francisco—a major port used by jinshanzhuang—residents of the Market Street Chinatown had full access to China-produced goods for sale in the United States. In contrast, Chinese railroad work camps were short-term settlements located in frontier and wilderness areas, providing a counterpoint to the urban Chinese diaspora communities exemplified by the Market Street Chinatown.

Making Home away from Home

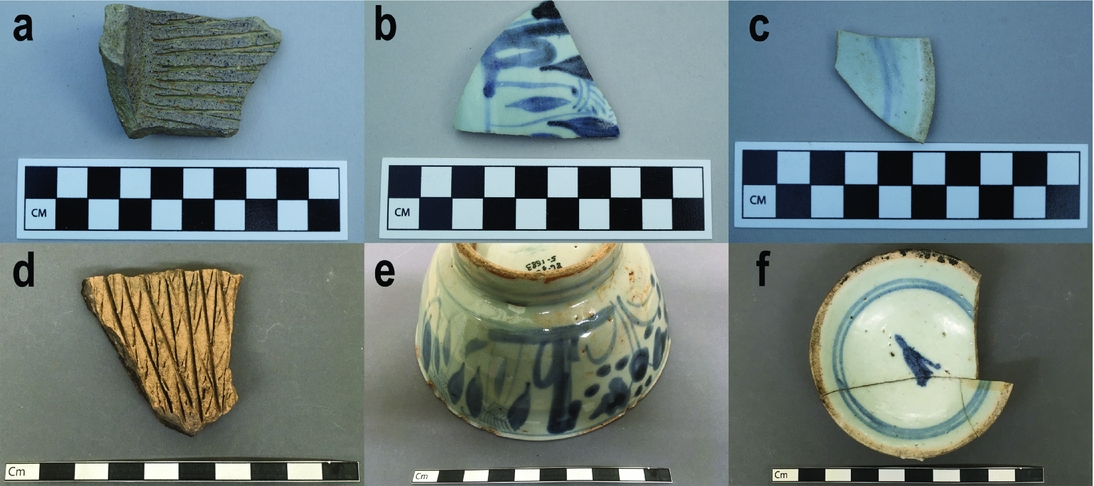

Several of the artifacts found in Cangdong Village are identical to those commonly found at Chinese diaspora sites. Figure 5 presents side-by-side images of three artifacts found in the 2016 survey of Cangdong Village (Figure 5a–c) and others recovered during the 1985–1988 excavation of the Market Street Chinatown in San Jose, California (Figure 5d–f): stoneware grater bowls; Bamboo pattern medium bowls, commonly called “rice bowls”; and porcelaneous stoneware oil lamp dishes used in home altars, temples, and shrines. These exact artifacts have also been found on Chinese railroad worker sites throughout the North American west (Maniery et al. Reference Maniery, Allen and Heffner2016; Voss Reference Voss2015, Reference Voss2018a, Reference Voss, Chang and Fishkin2018b). Other artifacts matched between Cangdong Village and Chinese diaspora sites include handled ceramic cooking pots, Chinese brown-glazed stoneware spouted jars and wine bottles, oil lamp stands, incense burners, and stoneware opium pipe bowls.

Figure 5. Identical nineteenth-century artifacts from Cangdong Village, Guangdong Province (a–c), and the San Jose, California, Market Street Chinatown collection (d–f): (a) stoneware grater bowl sherd; (b) Bamboo pattern rice bowl sherd; (c) porcelaneous stoneware oil lamp dish sherd; (d) stoneware grater bowl sherd; (e) Bamboo pattern rice bowl sherd; (f) porcelaneous stoneware oil lamp dish sherd (photos courtesy of the Cangdong Village Archaeology Project and Market Street Chinatown Archaeology Project).

These matched artifacts represent diverse realms of material practice—food preparation, dining, ritual practices, and drug consumption. They suggest the use of material culture to create a “home away from home.” Whether migrants were engaging in the mundane task of grating vegetables, eating meals, or lighting ritual oil lamps, these objects provided them with visual, tactile, and haptic continuity in new social and physical environments. The use of identical objects in both homeland and diaspora contexts may have also eased reentry for migrants returning to China. Their shared distribution enabled the physical extension of “home” from qiaoxiang to faraway locations across the diaspora.

Consuming China at Home and Abroad

Alongside artifacts matched between Cangdong Village and Chinese diaspora settlements, there are many others that reveal points of difference. This is especially true of China-produced ceramic tablewares dating to the late Qing dynasty (ca. 1800–1912) and Republic of China (1912–1949) periods.

Functionally, the late Qing dynasty China-produced ceramic tablewares found in Cangdong Village are similar to those found at Chinese diaspora settlements. The Cangdong Village assemblage is dominated by medium-sized bowls and other hollowwares such as large serving bowls, small and medium handleless cups, and teapots. Others have observed the same general pattern in Chinese diaspora settlements throughout North America (Ross Reference Ross2011b, Reference Ross2013a). This suggests that residents of both qiaoxiang and diaspora settlements purchased China-produced ceramic tablewares for similar functions.

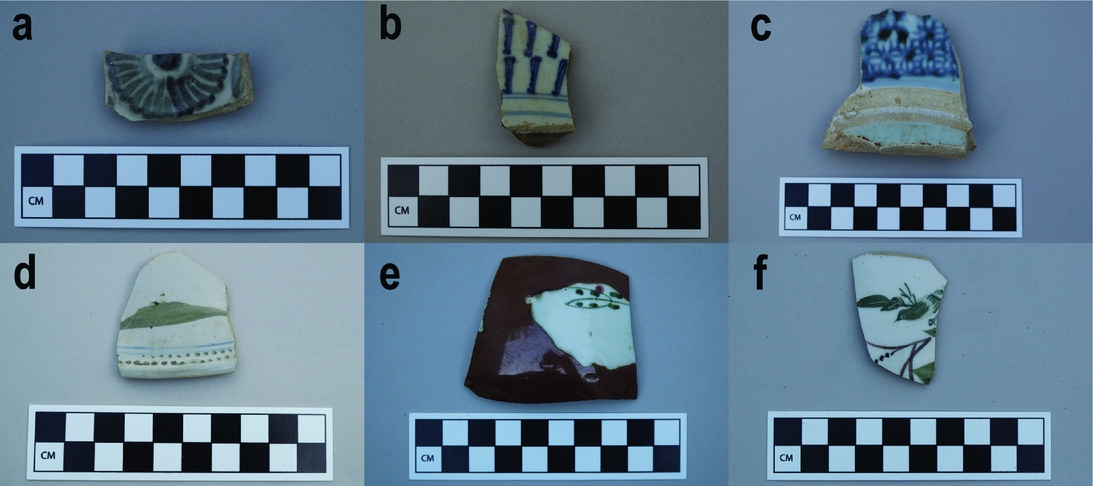

However, the decorative patterns on the China-produced ceramics are quite different. In Chinese diaspora settlements, China-produced ceramic tableware assemblages are dominated by five patterns: Double Happiness, Bamboo, Four Season Flowers, Winter Green, and Sweet Pea/Simple Flower (Figure 6). These vessels were manufactured in two large-scale proto-industrial kilns in ceramic-producing districts: Gaopizhen, in eastern Guangdong Province (about 550 km from Kaiping County), produced Bamboo and Double Happiness patterns; and Jingdezhen, in Jiangxi Province (about 1,000 km from Kaiping County), produced Four Season Flowers, Winter Green, and Sweet Pea/Simple Flower (Choy Reference Choy2014).

Figure 6. China-produced ceramic tableware patterns commonly found at Chinese diaspora settlements: (a) Bamboo; (b) Winter Green; (c) Four Season Flowers; (d) Double Happiness (photo courtesy of the Market Street Chinatown Archaeology Project).

In the Market Street Chinatown collection, these five patterns account for 99.84% of the 4,310 identifiable China-produced tableware ceramic sherds. Similar distributions of decorative patterns have been observed at Chinese railroad work camps (Maniery et al. Reference Maniery, Allen and Heffner2016; Voss Reference Voss2018a, Reference Voss, Chang and Fishkin2018b) and in analyses of ledgers from a Chinese general store in California (Sando and Felton Reference Sando, Felton and Wegars1993). In contrast, in Cangdong Village these five patterns account for only 66.90% of identifiable late Qing dynasty China-produced ceramic tablewares (Table 2).

Table 2. Late Qing Dynasty China-Produced Tableware Porcelain, Market Street Chinatown and Cangdong Village.

a Market Street Chinatown collection: 4,310 of 4,728 ceramic tableware sherds were identified to pattern.

b Cangdong Village collection: 145 of 555 ceramic tableware sherds were identified to patterns produced in the late Qing dynasty.

The majority of tableware ceramics found in Cangdong Village are Double Happiness medium-sized bowls (n = 82; 56.55%). However, the Double Happiness specimens recovered in Cangdong Village are noticeably different from the Gaopizhen-produced bowls found in Chinese diaspora sites in the United States. The Cangdong Village vessels are larger in size, are thicker-walled, and have a coarser paste, and their decorations are more freely applied (Figure 7). Comparison with historic collections indicates that the Double Happiness bowls found in Cangdong Village were most likely manufactured in Tai Po, Hong Kong, rather than in Gaopizhen (Guo 2017). Outside of the Double Happiness bowls, only 10.35% of the collected China-produced tableware sherds from Cangdong Village match with those from the Market Street Chinatown: six Bamboo pattern sherds and nine Winter Green sherds. Four Season Flowers and Sweet Pea/Simple Flower are completely absent from the Cangdong Village collection.

Figure 7. Comparison of Double Happiness rice bowl sherds found in (a) Cangdong Village and (b) the Market Street Chinatown (photos courtesy of the Cangdong Village Archaeology Project and Market Street Chinatown Archaeology Project).

Two interrelated dynamics appear to be generating the differences between the China-produced tableware ceramics used in Cangdong Village and in Chinese diaspora settlements. First, while only a limited number of decorative patterns were available in the diaspora, Cangdong Village residents used China-produced ceramics with a wider variety of decorations. Interestingly, these include several decorative patterns that North American archaeologists typically classify as “Chinese Export Porcelains” under the belief that they were manufactured primarily for sale to non-Chinese consumers in the West. These include Scrolled Chrysanthemum, Crown, Neoclassical, Worm Trail, and Batavian Brown (also called Capuchin Ware or Tzu Chin). These patterns have been archaeologically recovered in Dutch colonial South Africa, Indonesia, and Malaysia; British colonial Singapore and the American colonies; the early-republic United States; and London (Figure 8; Klose and Schrire Reference Klose, Schrire and Schrire2015; Madsen and White Reference Madsen and White2011:116–119, 123–128; Mudge Reference Mudge1986:187; Willits and Lim Reference Willits and Lim1982). However, the results of the Cangdong Village survey indicate that many of these so-called export wares were also distributed to the domestic market in southern China's rural villages.

Figure 8. China-produced late Qing dynasty and early Republic of China–period ceramic tablewares recovered during the survey of Cangdong Village: (a) Scrolled Chrysanthemum; (b) Sino-Sanskrit; (c) Crown; (d) Neoclassical; (e) Tzu Chin; (f) Fragrant Flowers and Calling Birds (photos courtesy of the Cangdong Village Archaeology Project). For ceramic classifications, see Klose and Schrire Reference Klose, Schrire and Schrire2015; Lister and Lister Reference Lister and Lister1989; Madsen and White Reference Madsen and White2011; Willits and Lim Reference Willits and Lim1982.

Second, it appears that Cangdong Village residents relied heavily on local ceramic kilns. As noted above, the Double Happiness bowls found at Cangdong Village were likely manufactured in Tai Po, Hong Kong. Additionally, 17.61% (n = 25) of the Cangdong Village China-produced tableware assemblage consisted of blue-on-white hand-painted wares with an unglazed reserve. These compare favorably with historic examples from kilns in neighboring Taishan and Xinhui Counties (Deng 2017). The absence of Four Season Flowers and Sweet Pea/Simple Flower in the Cangdong Village assemblage is especially notable because both these decorative types are associated with the Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi Province. Residents of Cangdong Village may not have had access to these Jingdezhen-produced ceramics or may have preferred not to use them.

Taken together, these findings indicate that late Qing dynasty residents of Cangdong Village had access to a greater variety of ceramics than were used in Chinese diaspora settlements and also primarily used locally produced wares made in adjacent counties. In contrast, Chinese diaspora residents throughout North America and in parts of Australia and New Zealand primarily used China-produced tableware ceramics decorated in only five patterns. This indicates the powerful role that jinshanzhuang played in shaping the material worlds of Chinese migrants through the selective procurement and distribution of China-produced material culture. The uniformity and homogeneity of China-produced ceramic tablewares in the diaspora suggests that jinshanzhuang probably had high-volume contracts with specific manufacturers for standardized goods. We suspect that jinshanzhuang similarly influenced the composition of other categories of supplies shipped to diaspora communities. For example, sherds of brown-glazed stoneware storage vessels recovered during the Cangdong Village survey included a wider range of vessel forms, vessel sizes, paste composition, and surface treatment than those typically found in North American Chinese diaspora sites (Voss and Kennedy Reference Voss and Kennedy2017:80–83).

The finding that the China-produced material culture used in diaspora contexts generated difference alongside familiarity raises important conceptual questions in the interpretation of material culture on diasporic sites. Which attributes of any given object were of primary significance to users? Specifically, did it matter to Chinese migrants if the rice bowls they used in the United States were a slightly different shape or size, had a different feel due to paste and glaze differences, or had different decorations than the rice bowls they had used in their home village?

While migrants’ responses to material culture introduced by jinshanzhuang undoubtedly varied within and across diaspora communities, we suspect that the attributes of China-produced tablewares likely had significance beyond their functional qualities. The vessels’ elaborately painted decorations had symbolic as well as aesthetic significance (e.g., Choy Reference Choy2014; Ho Reference Ho, Scott and Hunt1987; Welch Reference Welch2008; Willits and Lim Reference Willits and Lim1982). For example, the Bamboo pattern in Figure 5 contains motifs that reference resilience, health, and long life in the face of adversity (Choy Reference Choy2014). The Four Season Flowers vessels (Figure 6c) present floral elements representing the four seasons (peony, lotus, chrysanthemum, and plum), circling a peach motif representing longevity: as one bloom fades with the passage of time, another plant buds and blossoms, in an eternal cycle.

During consultations related to our community-based archaeology research in the United States, present-day descendants of nineteenth-century Chinese migrants frequently commented on the meanings of Bamboo, Four Season Flowers, and other patterns. A few descendants shared that their personal childhood rice bowl was a Four Season Flowers bowl, often handed down to them from an older relative, a material practice that resonates with the symbolism of the bowl's decorations. Notably, although Four Season Flowers vessels are found in almost all Chinese diaspora sites in the United States, this pattern was completely absent from the Cangdong Village survey collection. These anecdotal accounts suggest that some residents in the Chinese diaspora attended to the aesthetic, as well as the functional, qualities of jinshanzhuang-supplied China-produced material culture.

Consuming the West

While the China-produced tablewares found at Cangdong Village indicate a preference for or reliance on locally produced goods, other artifacts reveal that qiaoxiang residents were also participating in global marketplaces. Nine sherds of British refined earthenwares, three US-produced glass bottles, and a four-hole Bakelite button all indicate villagers’ use of “Western” material culture.

British refined earthenwares, also colloquially called “whitewares,” were primarily manufactured in Staffordshire, England, and had a wide global distribution throughout the nineteenth century (Majewski and O'Brien Reference Majewski and O'Brien1987). Exhibits at the Guangdong Provincial Museum in Guangzhou and the Jiangmen Wuyi Museum of Overseas Chinese include specimens of British refined earthenwares to illustrate the presence of foreign merchants and missionaries in nineteenth-century Guangdong Province port cities. The Cangdong Village survey provides the first material evidence of British refined earthenware use by rural villagers in the Pearl River Delta.

The nine specimens recovered in the Cangdong Village survey are all classified as “improved whiteware” due to paste hardness greater than 5.5 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness. Improved whitewares were introduced in the 1840s and were in peak production through the 1890s (Majewski and O'Brien Reference Majewski and O'Brien1987). Four of these are undecorated, three are hand-painted (two with floral motifs and one with rim banding), one is transfer-printed with a floral motif, and one is decal-printed with hand-painted accents, also in a floral motif. These decorative techniques and styles are consistent with British refined earthenwares produced and marketed throughout the 1850s–1890s. The prominence of floral motifs and rim banding is notable, as these decorations may have been aesthetically harmonious with China-produced porcelain vessels (Figure 9).

Figure 9. British refined earthenware transfer-printed sherd, with an openwork brown floral design (photo courtesy of the Cangdong Village Archaeology Project).

Two glass bottles are colorless cylindrical medicine bottles dating to the late Qing dynasty and Republic of China periods. The first is an unlabeled pill bottle manufactured by the DuBois Glass Company in Massachusetts (1914–1918; Jones and Sullivan Reference Jones and Sullivan1989; Lindsey Reference Lindsey2014, Reference Lindsey, Schulz, Allen, Lindsey and Schultz2016:40). The second bottle, which is very fragmented, has a stopper finish and likely held liquid medicine. It is embossed with both English and Chinese text (Figure 10). The English text, “GREENS // . . . CAL. //,” if complete would likely read “GREENS LUNGS RESTORER / SANTA ABIE // ABIETINE MEDICAL CO // OROVILLE, CAL. U.S.A.” (Fike Reference Fike1987:212). Only two of the four surviving Chinese words are legible: 青 (qing—blue or green) is likely a translation of R. M. Green's last name, and 廠 (chang—factory or mill) likely refers to the Abietine Medical Company, which was in operation from 1885 to 1921 (Mansfield Reference Mansfield1918). This bottle is discussed at greater length in the following section. The third bottle, a colorless embossed rectangular shoe polish bottle, likely was manufactured during 1914–1930. The embossed label, “WHITEMORES [sic] SHOE POLISH,” refers to Whittemore Bros. & Company, a household products company in Boston, Massachusetts (Lindsey Reference Lindsey, Schulz, Allen, Lindsey and Schultz2016; Russell Reference Russell2017; Toulouse Reference Toulouse1971).

Figure 10. Bilingual medicine bottle distributed by the Abietine Medical Company, Oroville, California (photo courtesy of the Cangdong Village Archaeology Project).

Together, these artifacts indicate that residents of Cangdong Village during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were using some industrially produced goods from Europe and the United States. British improved earthenware dishes suggest the use of imported ceramics to augment the China-produced tablewares already in use. The two glass medicine bottles point toward the adoption of US-produced products in personal health and hygiene. The shoe polish bottle and a Bakelite button indicate the adoption of some items of European- and American-style dress.

Emergence of New Cultural Forms

Although the Abietine Medical Company bottle listed above was produced in the United States, it is not necessarily a “Western” commodity. English-labeled Abietine Medical Company bottles are well known to archaeologists and collectors, but the bilingual bottle recovered in Cangdong Village provides the first evidence that the Abietine Medical Company was marketing its products to Chinese-speaking consumers.

The history of the Abietine Medical Company is well known. In 1864, groves of pines suitable for the manufacture of abietine—a distillate of pine sap—were discovered in Butte County near Oroville, California, and in January 1885, Oroville resident R. M. Green founded the Abietine Medical Company to produce and distribute medications made from abietine (Mansfield Reference Mansfield1918:319). Green secured trademarks for use of the Abietine Medical Company name for “Catarrh cure,” “Preparation for lung and throat diseases,” and “Distillation from abietine-gum, and salves, ointments, and other compounds made therefrom” (US Patent Office 1885:109). However, it is unknown how Green developed these new medications. Biographical sources suggest that Green was an entrepreneur without prior medical or scientific training. Along with directing the Abietine Medical Company, Green co-owned a gold mine, was a founder of the Bank of Oroville, established a drug store, managed multiple real estate holdings, and promoted agricultural and irrigation developments throughout Butte County (Aiken Reference Aiken1903:190; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Keyes, Bishop, Lyle and Doolittle1897; Lenhoff Reference Lenhoff2001:52, 60).

Green likely collaborated with Chinese American partners in order to develop and market medicinal products targeting Chinese-speaking consumers. Although there are no written records found to date that document Green's potential Chinese collaborators, a historic photograph on display at the Oroville Chinese Temple (列聖宮) suggests one possible partnership. The photograph, titled Fong Lee Company, 1215 Lincoln Street, Oroville, California, 95965 Butte County, appears in a small exhibit celebrating Chinese herbalist Chun Kong You's contribution to Oroville's history. The exhibit text indicates that this photo was taken in front of Chun's store, the Fong Lee Company, during a Chinese New Year Parade on January 26, 1895. The label identifies Green as one of the people standing with Chun at the front of the store.

Interpretive text accompanying the photograph indicates that Chun (ca. 1840s–1897) first came to the United States in 1867 from Taishan County, Guangdong Province, to work as a railroad laborer. From 1869 to 1879, Chun operated a Chinese herb store in Truckee, California. In the late 1870s, Chun established Oroville's Fong Lee Company, which sold herbal Chinese medicines and also provided international postal services for Chinese migrants. Already well established at the time of the founding of the Abietine Medical Company, Chun and the Fong Lee Company would have been advantageous partners for Green. Chun's knowledge of traditional Chinese medicine may have contributed to the formulation of the Abietine Medical Company's products. The Fong Lee Company's connections with jinshanzhuang—which would have been necessary to import Chinese medicines and to send mail to the Pearl River Delta—would have enabled Green to distribute and market his products not only to Chinese Americans but also to consumers in the Pearl River Delta.

The Abietine Medical Company bottle recovered during the Cangdong Village survey cannot be classified as either “European American” or “Chinese.” It was instead produced and distributed through the complex relationships and exchanges that developed between European-descendant and Chinese-descendant settlers in the nineteenth-century US west. This new commercial product then circulated back to Guangdong Province, bringing innovations from the diaspora back home.

Conclusions

The results of archaeological survey of Cangdong Village indicate that the transnational dynamics of material culture use and associated cultural practices were more complex than previous archaeological interpretations of Chinese diaspora sites have recognized. These dynamics can be summarized under three main points:

1. Qiaoxiang and diaspora communities used both similar and different kinds of China-produced goods. While some artifacts found in Cangdong Village are identical to those recovered from Chinese diaspora settlements, other China-produced artifacts show differences between the material culture used in qiaoxiang and that used in diaspora communities. It appears that in the diaspora, Chinese migrants had access to less variety of China-produced goods and to different goods than those used in their home villages. Migrants thus would have encountered both familiarity and difference in the China-produced material culture used in diaspora communities. Migrants returning to China, who had become habituated to the material culture available in the diaspora, would have experienced some level of discontinuity when reentering daily life in their home villages.

2. Qiaoxiang communities were active participants in the global marketplace. Cangdong Village residents acquired British- and US-produced products, including ceramic tablewares, medicines, grooming products, and clothing. They also consumed China-produced ceramic tablewares that North American archaeologists have typically categorized as “export” ceramics because of design features that appealed to “Western” tastes and their distribution to Europe and European colonies and postcolonies. However, it appears that many such “export” ceramics were also produced and distributed to a domestic Chinese market, indicating that consumer taste both in China and abroad was being shaped by international flows of materials and design aesthetics.

3. Interethnic interactions in diaspora contexts generated new cultural forms and consumer products, which circulated not only within the diaspora but also back to qiaoxiang. Although archaeologists studying the Chinese diaspora often classify objects as either “Chinese” or “Western” based on the objects’ location of manufacture, artifacts such as the Abietine Medical Company bottle indicate syncretism arising from interethnic collaboration and commerce.

Lacking comparative data from qiaoxiang, archaeologists studying Chinese diaspora communities have consistently made two paired assumptions: first, that China-produced objects found in diaspora contexts indicate cultural continuity and, second, that European- and US-produced objects indicate either cultural change or expedient acquisition of “Western” goods because they were cheaper or because Chinese goods were not available. The results of the Cangdong Village survey provide an empirical challenge to these assumptions. It is now clear that China-produced material culture distributed to diaspora communities both contributed to the creation of “homes away from home” and simultaneously generated difference between life in the Pearl River Delta and life in the diaspora. Similarly, qiaoxiang residents’ use of US- and European-produced products challenges the assumption that similar objects, when found in diaspora contexts, indicate cultural change. Since these goods were used as part of daily life in the qiaoxiang, the use of these and similar products in diaspora contexts could indicate continuity with, rather than departure from, familiar practices.

At its core, this study draws new attention to the ways in which southern China's qiaoxiang and Chinese diaspora communities were mutually produced through transnational flows of people, objects, and aesthetics. The central role of nonstate actors—especially clans and mutual aid associations—has long been recognized by historians and sociologists studying the Chinese diaspora. This archaeological study indicates that international corporations such as jinshanzhuang were also instrumental in generating the conditions of daily life both in the diaspora and in the Pearl River Delta. In archaeological studies of diaspora communities, the influence of nonstate actors should be examined alongside “cultural” factors such as tradition, hybridity, syncretism, and assimilation. Archaeologists can no longer assume that artifacts manufactured in migrants’ home countries necessarily indicate continuity with homeland material practices. Likewise, rather than being viewed as a repository of tradition, diaspora homelands need to be considered as active and dynamic participants in existing and emerging global networks.

Diasporas are commonly defined through the tension between migrants’ shared connections to and experiences of dislocation from a distant homeland. The results of the Cangdong Village survey serve as an entry point into the study of how homelands themselves were transformed through migration. Rather than serving as a passive repository of tradition, qiaoxiang were actively generated by migrants and their families and clan members through engagement with transnational nonstate actors such as mutual aid associations and import-export firms. These relationships enabled the continuation and evolution of “home” in China as well as the expansion of “home” to locations throughout the globe. Multisite archaeological research, such as the transnational comparative analysis presented here, is necessary in order to investigate the complexities of diaspora formation at home and abroad in the modern world.

Acknowledgments

The Cangdong Village Archaeology Project was conducted under an Intention of Cooperation, signed November 24, 2016, between the Guangdong Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology of the People's Republic of China; the Guangdong Qiaoxiang Cultural Research Center at Wuyi University in Jiangmen City, Guangdong Province; and the Stanford Archaeology Center at Stanford University. The December 2016 survey of Cangdong Village was authorized by Deng Hongwen (Guangdong Provincial Institute) and Xie Xuenuan (Cangdong Village head) and conducted under the supervision of Dr. Zhang Guoxiong (chair, Guangdong Qiaoxiang Cultural Research Center at Wuyi University). Research team members included archaeologists Virginia Popper, Chelsea Rose, Koji Ozawa, Nicole Martensen, and Kimberley Garcia; historians Matthew Sommer, Peter Hick, and Joseph Ng; photographer Barre Fong; cartographers Li Jijin and Katie Johnson-Noggle; and translator Jiajing Wang. Deborah Cohler, Ariana Fong, Marisa Fong, and Royce Fong provided valuable assistance to the research team throughout the survey project. Deng Hongwen, Guo Xuelei, Priscilla Wegars, Leland Bibb, Scott Baxter, and Ray von Wandruzka assisted with post-field artifact identification and analysis. Grace Alexandrino Ocana and Jiajing Wang translated the abstract into Spanish and Chinese, respectively. We are grateful to Robert L. Kelly and two anonymous reviewers for comments that greatly improved this article. Financial and logistical support was generously provided by Wuyi University (Guangdong Qiaoxiang Cultural Research Center), the Cangdong Village Heritage Education Project, and Stanford University (the Office of International Affairs, Institute for Research in the Social Sciences, Freeman-Spogli Institute China Fund, Center for East Asian Studies, Lang Fund for Environmental Anthropology, Department of Anthropology, and Stanford Archaeology Center).

Data Availability Statement

All collected artifacts, field and laboratory records, an inventory of the collection, associated documentation, and the technical report (Voss and Kennedy Reference Voss and Kennedy2017) are archived at the Guangdong Qiaoxiang Cultural Research Center at Wuyi University, Kaiping County, Guangdong Province, China.

Supplemental Materials

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2018.16.

Supplemental Text 1. Spanish Abstract