Introduction

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Sandakan and Jesselton were small ports in a quiet corner of the British empire.Footnote 1 Yet they were the largest urban centres in North Borneo, which was then a protectorate governed by a chartered company and is now the East Malaysian state of Sabah. Although they were located on opposite coasts of the territory – separated by more than 300 kilometres of shoreline – the two towns had remarkably similar multiethnic societies composed primarily of migrant peoples. In a 1922 guidebook, a former government official described their myriad inhabitants: Arab traders, Chinese cooks, Filipino barbers, Japanese demimondaines, Javanese labourers and Sikh policemen. In Jesselton, the gambling house was ‘as cosmopolitan as a continental casino’.Footnote 2 Using less discerning language, a visiting Australian photojournalist depicted Sandakan as ‘a seething mass of Asiatics, Chinese predominating, with Japanese and Indians intermingled’.Footnote 3 Although there were people of European ancestry present, such accounts focused on the astonishing diversity of Asians in these colonial towns. Beneath these exoticized impressions was an undercurrent of curiosity about this medley of people. What held these societies together? How did various social groups live in proximity together? How was urban life in small colonial towns organized?

This article investigates the origins, morphology and everyday experiences in Sandakan and Jesselton to offer a history of colonial urbanism through one of its most overlooked spaces: the neighbourhood. At first sight, neighbourhoods might not seem to be relevant units of study in smaller urban centres. The literature on neighbourhoods in urban history generally focuses on major cities.Footnote 4 Indeed, neighbourhoods might not appear to exist in the towns of North Borneo because the term was never used by their inhabitants or the colonial government. The compact size of Sandakan and Jesselton meant that they did not contain districts that were separately administered. This article argues, however, that there were socio-spatial quarters within both towns analogous to neighbourhoods. The boundaries of these quarters were based on informal perceptions of urban space that partially reflected ethnic divisions in society, making them meaningful subjects of study. At the same time, because of their unofficial and legally undefined nature, the socio-spatial boundaries of Sandakan and Jesselton were arguably more easily transgressed than in larger urban centres. Overall, the construction and lived experience of ‘neighbourhoods’ in these towns reveal that life in the smaller centres of empire was different. The likelihood and intensity of cross-communal encounters was higher. Depending on the circumstances, this proximity could result in a keener sense of difference, prejudice, wariness, amity or tolerance. These were spaces of fluid, rather than fixed, social boundaries and interactions. This article examines Sandakan and Jesselton together not only because of their pronounced similarities but also to demonstrate that their experiences of colonial urbanism were neither unique nor exceptional.

Within the historiography of urban life in colonial settings, places like Sandakan and Jesselton occupy a marginal place. With few exceptions, the existing literature focuses on cities, especially those embedded in regions that were considered economically or politically significant, rather than towns. Here, the actual definition of what constitutes a city or town is less crucial than what these labels indicate about positions within a given urban hierarchy. Under most circumstances, a town will always be smaller, more isolated and regarded as less important than a city. Yet it is precisely because of their relatively small sizes and remote locations that colonial towns – on the margins of empires and the scholarship about them – are poised to broaden perspectives on colonial urbanism. As far back as 1967, Terry McGee, the pioneering scholar of Southeast Asian urban studies, made a similar case for studying ‘the multiplicity of other colonial urban types’. He regarded smaller urban centres as vital sites of colonial power:

While it is the remarkable growth of the large multi-functional port-towns, such as Saigon-Cholon, Singapore, Batavia, Manila, Rangoon and Bangkok, which dominate the pattern of city growth in the nineteenth century, the proliferation of the smaller urban centres should not be ignored because of their important role in helping the colonial machine operate so effectively; the railway junction town, the small coastal port, the mining settlement, and the district headquarters enabled the colonial powers to build up their control over the traditional economy and societies of Southeast Asia.Footnote 5

The European colonial project in the region relied not only on its primate cities but on entire urban hierarchies that included numerous centres of every size and function. The scholarship on the relationship between colonialism and urbanism would be incomplete without histories of smaller centres.

Importantly, colonial towns are also ideal sites to examine urban proximity in colonial societies. Studying neighbour relations in colonial cities comes with the task of defining a neighbourhood. In large centres, neighbours might or might not have had more than ‘a fragment of geography’ in common with each other, but locating the boundaries of a given neighbourhood is a contentious subject.Footnote 6 Whose definitions of the neighbourhood should be prioritized? How did its shape change over time? The tension between municipal authorities, social elites and the poor over the demarcation of urban space has probably been around for as long as cities have. On the other hand, smaller centres might not have been large enough to contain neighbourhoods or districts that were governed separately. But even these urban environments were organized and demarcated in their own ways that require further scrutiny. Moreover, the compact size of colonial towns made everyday encounters and interactions between different social groups frequent and inevitable. Indeed, in her study of Malaya, Lynn Lees noted that the ‘small scale’ of certain towns encouraged socialization among wealthy Chinese and Europeans.Footnote 7 The small size of colonial towns presents scholars with an opportunity to set aside concerns about defining neighbourhoods and focus on other crucial questions about the social history of urban proximity.

The notion of segregation has long pervaded the study of colonial societies and cities. Histories of colonialism in Southeast Asia commonly evoke John S. Furnivall’s concept of the ‘plural society’ to explain the existence and persistence of ethnic stratification.Footnote 8 This concept refers to an inherently unstable society where different ethnic groups lived ‘side by side, but separately, within the same political unit’, only brought together to oil the wheels of the colonial economy.Footnote 9 Since Furnivall introduced this concept in 1948, other scholars have observed how physical space in colonial regimes, particularly in urban areas, was sectionalized by ethnicity. Janet Abu-Lughod was one of the first to explain how a colonial city – specifically nineteenth-century Cairo – consisted of ‘two distinct physical communities’: an ‘old native city’ and a ‘new westernized city’.Footnote 10 According to Anthony King, the segregation of urban space was an ‘instrument of control’ that minimized contact between colonial and colonized people. It enabled the former group to preserve its own identity, which was ‘essential in the performance of its role within the colonial social and political system’.Footnote 11 This sort of separation could also make it easier to govern members of different ethnic groups. In his study of Kuching, the capital of the Raj of Sarawak, Craig Lockard discussed how the White Rajahs practised a system of indirect rule, in which Chinese and Malay communities were governed separately by their own elites. This form of urban governance, which drew a legal distinction between people based on their ethnicity, had ‘the effect of segregating the various ethnic groups and further segmenting urban society along ethnic lines’.Footnote 12 More recently, Carl Nightingale observed that the practice of segregation in the colonial cities of Asia was contingent on evolving ideas of racial difference.Footnote 13

On the other hand, a new wave of empirical studies has challenged the idea that there were hard boundaries between different social groups in colonial cities. In her 2016 book, Su Lin Lewis explored the cross-cultural interactions of ‘middle-class’ Asians in Bangkok, Penang and Rangoon, at sites such as cinemas, civic associations and schools. This history of ‘urban cosmopolitanism’ demonstrates how these people shared interests and practices that spanned ethnic divisions.Footnote 14 Similarly, Lees wrote about how ‘Asian men of middle status’ became part of a multiethnic civil society in the urban centres of nineteenth-century Malaya. Intermingling in common social spaces, like clubs and offices, helped with ‘blurring categories of difference’ between these men.Footnote 15 Defying the rudimentary racial categories imposed by colonial regimes, some mestizo or mixed-race communities were able to drift between different social circles because of their multiple heritages. In her study of the Macanese diaspora in British Hong Kong, Catherine Chan detailed how these ‘Luso-descendentes with Macau roots’ had ties to several civic and ethnic associations.Footnote 16 Although not without their critics, such histories offer an alternative to narratives of communal division that appear to characterize a previous generation of scholarship.

This article diverges from the historiography by emphasizing the ambiguity and contingency of colonial urban life. It demonstrates that Europeans and various Asian communities created their own social worlds in Sandakan and Jesselton with neighbourhood-like boundaries that were distinct but permeable. Even as the smallness of these towns likely fostered a slightly higher degree of interaction between individuals of different social groups compared to major colonial cities, multiple forms of discrimination remained widespread. It might be too imprecise, therefore, to simply characterize Sandakan and Jesselton as either sites of segregation or cosmopolitanism. Instead, life in these small towns at the fringes of the empire was complex. The ability of individuals to navigate the socio-spatial boundaries of the ‘neighbourhoods’ in these towns varied not only according to their ethnicity but also factors such as class, gender and language proficiency. At the same time, there were certain occasions and locations that allowed townspeople from different social groups to mingle more freely. In essence, what this article offers is an invitation to further complicate histories of colonial urban life.

This article contains three main sections. The first explores how the demographics of Sandakan and Jesselton were directly related to their function in the colonial economy of North Borneo. The following section traces where the spatial and social boundaries between different ethnic groups in the towns lay – akin to neighbourhoods – showing the existence of several distinct social spheres. Finally, the third section probes the porosity of the socio-spatial divides in Sandakan and Jesselton, examining who was able to transgress them and when.

Capitals of a colonial economy

The ethnic composition of Sandakan and Jesselton was an outcome of the role they played in the economy of North Borneo. The towns were service centres that supported the extraction of natural resources: distributing supplies and labour, dispensing financial assistance, processing goods and maintaining communications with the world. Within this economic system, there was a division between urban and rural functions, with certain ethnic groups dominating each sector. Founded in 1879, Sandakan was one of the oldest urban settlements in North Borneo. Through a coastal and riverine transport system, it came to dominate the economy of the eastern coast, exporting a wide range of cultivated and wild-collected commodities, including timber, tobacco and trepang. Jesselton was established in 1899 as the terminus for a pioneering railway on the western coast of the territory.Footnote 17 Caught by the rubber-planting craze sweeping Southeast Asia, it specialized in and grew wealthy from the export of rubber from the 1910s. As the chief commercial centres of North Borneo, the towns attracted migrants from across Asia, which gave rise to their multiethnic populations.

Despite their significance in the territory, Sandakan and Jesselton were relatively small urban centres in Southeast Asia.Footnote 18 According to official census records, the largest recorded population size for the towns, including their suburbs, before World War II was about 25,000 people each in 1931. However, without their suburbs – an intermediate zone between the towns and their hinterlands – they would appear even more diminutive. There were 13,723 inhabitants in ‘Sandakan Town’ and merely 4,594 inhabitants in ‘Jesselton Town’Footnote 19 Although the Great Depression reportedly caused a decrease in the towns’ population when the census was carried out, this remains the most accurate estimate.Footnote 20 In comparison, the major cities in the region had populations tens of times larger than Sandakan and Jesselton. In 1930, the largest city in Southeast Asia was probably Singapore, with an estimated population of 558,000. This was followed closely by Bangkok and Batavia, which respectively had populations of 490,000 and 437,000.Footnote 21

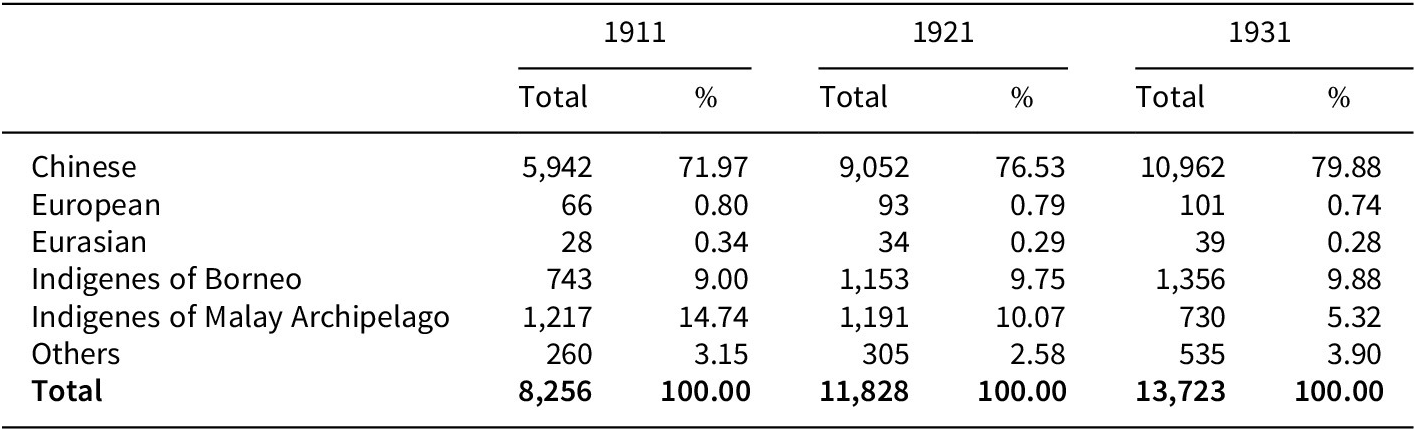

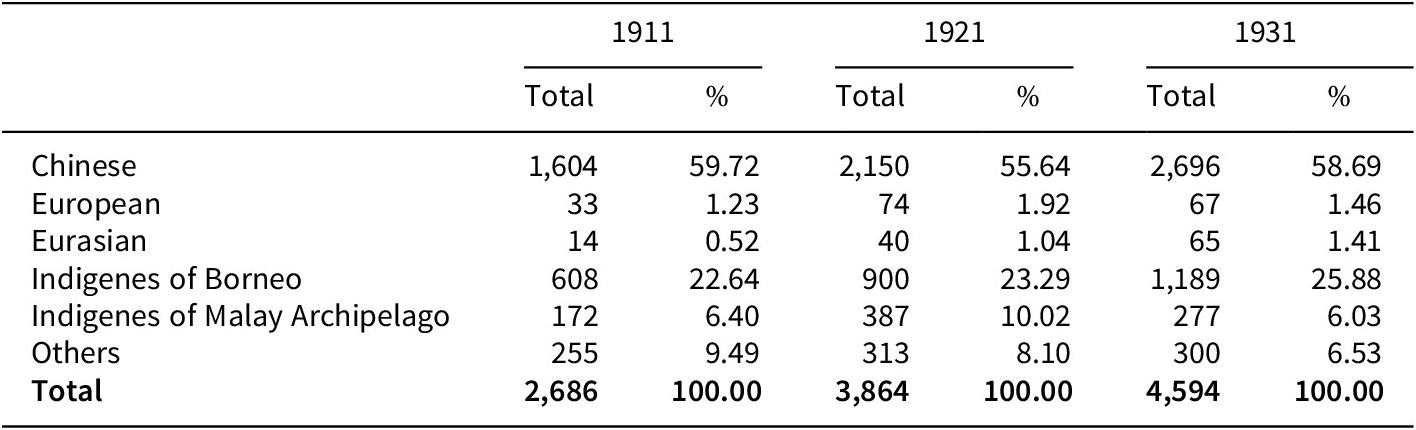

Nevertheless, the ethnic compositions of Sandakan and Jesselton were comparable to major colonial centres in Southeast Asia, not only in terms of ethnic diversity but also the predominance of non-indigenous people. In 1931, slightly less than a third of the population in Rangoon consisted of indigenous people – identified by census officials as the Burmese, the Karens and ‘other indigenous races’. Most of the city’s population were Indian people belonging to various ethnolinguistic groups, and there were substantial minorities of Chinese, European and mixed-race people. The fact that half of the population was born outside of Burma led census officials to conclude that ‘the population of Rangoon is largely composed of immigrant races’.Footnote 22 Sandakan and Jesselton were similarly inhabited by a majority of non-indigenous people, as shown in Table 1 and Table 2. In the early twentieth century, indigenous Borneans – which referred to Bajau, Brunei, Dusun, Murut and Suluk people – formed less than a quarter of Jesselton’s population. In Sandakan, less than a tenth of the population was made up of indigenous Borneans. Chinese people of several ethnolinguistic groups – the most prominent of which were the Cantonese, Hokkiens and Teochews – formed the largest ethnic class in both towns.Footnote 23 By 1931, about 80 per cent and 60 per cent of the populations in Sandakan and Jesselton, respectively, were Chinese. The other non-indigenous ethnic groups in the towns were placed under general, and occasionally confusing, classifications. Individuals from the Malay Peninsula and the Netherlands East Indies were regarded as the indigenous people of the Malay Archipelago, while individuals from the Philippines were included under the catchall heading of ‘Others’, which included Arab, Indian and Japanese people.Footnote 24 Despite their small numbers, Europeans – which included Australians, New Zealanders and North Americans – and Eurasians were placed in their own ethnic categories. The ethnic classifications used in the censuses for North Borneo were flawed in the same ways that other colonial censuses were. As Charles Hirschman argued, these ever-changing systems of classification first reflected an ignorance of the Asian population by European administrators and then, from the start of the twentieth century, an adoption of an ideology on racial difference and hierarchy.Footnote 25 What the census data for North Borneo undeniably indicates, however, is that Sandakan and Jesselton were spaces principally created by and for non-indigenous groups.

Table 1. Ethnic composition of Sandakan town, 1911–31

Source: The National Archives (TNA), CO 874/646, secretary, British North Borneo Company, to undersecretary of state, Colonial Office, 31 Oct. 1911; D.R. Maxwell, State of North Borneo: Census Report, 24th April, 1921 (Sandakan, c. 1921), 13; A.N.M. Garry, Report on the Census of the State of North Borneo, Taken on the Night of 26th April, 1931 (Hong Kong, 1931), 13.

Table 2. Ethnic composition of Jesselton town, 1911–31

Source: TNA, CO 874/646, secretary, British North Borneo Company, to undersecretary of state, Colonial Office, 31 Oct. 1911; Maxwell, Census Report, 1921, 13; Garry, Report on the Census, 1931, 13.

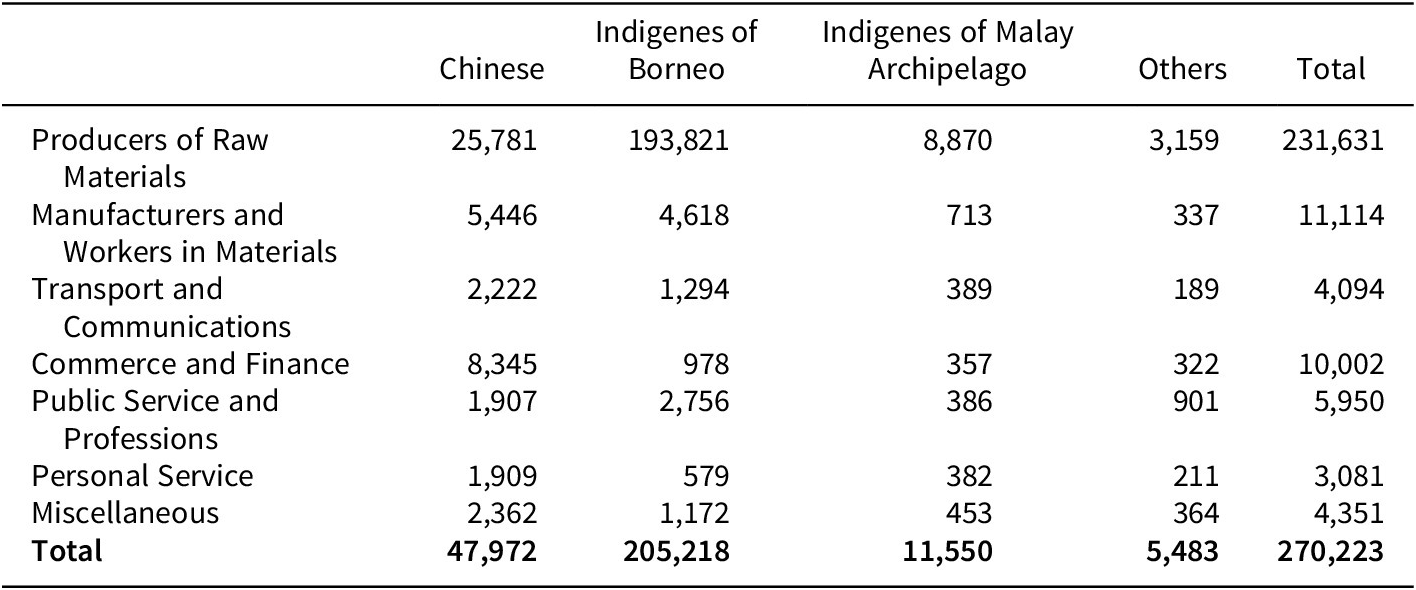

Although official censuses did not include occupational data for the towns in the early twentieth century, the available data suggests that there was a rough ethnic division of labour across the territory.Footnote 26 Table 3 shows that, in 1931, the Chinese held the greatest number of jobs classified under the headings of ‘Manufacturers and Workers in Materials’, ‘Transport and Communications’ and ‘Commerce and Finance’. These were urban occupations that were overwhelmingly concentrated in Sandakan and Jesselton. In comparison, the indigenous people of Borneo, which formed most of the population in the territory, held the greatest number of jobs classified under the headings of ‘Producers of Raw Materials’ and ‘Public Service and Professions’. The former heading refers to occupations, such as agricultural workers, forestry workers and fishermen, that were in rural areas. Moreover, the dominance of indigenous Borneans in the latter category is not as consequential as it appears because they were largely employed as ‘government labourers’ in the hinterlands.Footnote 27 A significant number of people from other ethnic groups, classified as ‘Others’ in Table 3, also held jobs that tended to be located in the two towns. In other words, urban economic activity in North Borneo was oriented towards non-indigenous people, which resulted in indigenous Borneans having a smaller presence in Sandakan and Jesselton. As with their ethnic compositions, the economies of the two towns also shared similar characteristics to colonial cities in the region. McGee noted that indigenous Southeast Asians occupied a marginal place in the economies of colonial cities, being primarily engaged in rural work, while ‘alien Asian communities’ held the most urban occupations to a staggering degree.Footnote 28

Table 3. Seven principal types of occupations by main ethnic divisions for the whole state of North Borneo, 1931

Source: Garry, Report on the Census, 1931, 79.

Circumstantial evidence also suggests that there was an ethnic division of labour within the towns. Occupational records for Sandakan in 1891, one of a few existing sources with such data, indicate that non-indigenous Asians – like Chinese, Indian and Japanese people – worked in a diverse array of occupations, from attap-makers and coolies to clerks and traders. Europeans, however, worked almost exclusively in higher-paying occupations, typically in the civil service or commerce.Footnote 29 The occupational structure in Sandakan and Jesselton probably only changed slightly in later decades, as the government encouraged a degree of ethnic specialization in the economy. From its earliest years, the British North Borneo Company had planned to develop the territory through a combination of European corporate administration and Asian, especially Chinese, labour and capital. At a shareholder meeting in London in 1883, the company’s chairman stated that the two conditions for North Borneo’s prosperity were ‘the rapid inflow of an industrious population from China and the adjoining territories of Sulu and Brunei’ and ‘a large investment in capital’ from Australia, Britain and China.Footnote 30 In turn, the ethnic-based divisions of the economy and society ran in parallel.

A colonial society, for Frantz Fanon, was a ‘system of compartments’ bisected into ‘native quarters’ and ‘European quarters’. In this Manichean world that reflected his experience in Algiers, those who held governing power were ‘first and foremost those who come from elsewhere’.Footnote 31 Despite its immense significance, however, Fanon’s conceptualization of colonial urbanism does not wholly fit the context of Sandakan and Jesselton, where the colonial economy produced multiethnic migrant populations of subjects. Nor, for that matter, does it work well in many colonial urban places in Southeast Asia with similar ethnic compositions. In North Borneo, the interplay of colonial policies, ethnicity and labour shaped the morphology, daily life and neighbour relations of the two towns in ways different from Fanon’s colonial city.

Socio-spatial boundaries

There were several social worlds in Sandakan and Jesselton, each of which had their own communities, institutions and festivities. Although they were not entirely closed to outsiders, these worlds had perceptible spatial and social boundaries that resembled neighbourhood spaces. This was perhaps most visible in the morphology of the towns, which were literally organized into a hierarchy for different ethnic groups. Sandakan and Jesselton had similar geographies; both were built on narrow strips of land between the sea and the hills. Asian communities lived and worked in the undesirable low-lying areas of the towns next to the shoreline, while commercial, government and public buildings – including the parade ground, that ubiquitous feature of British colonial settlements – were in the foothills. Europeans, occupying the apex of these colonial societies, lived in houses on the hills.

Arriving by ship, the dramatic layout of the towns was often the first thing that visitors noticed. During a brief stopover in 1920, the American writer E. Alexander Powell wrote about the appearance of Sandakan in detail:

Sandakan itself straggles up a steep wooded hill, the Chinese and native quarters at its base wallowing amid a network of foul-smelling and incredibly filthy sewers and canals or built on rickety wooden platforms which extend for half a mile or more along the harbor’s edge. A little higher up, fronting on a parade ground which looks from the distance like a huge green rug spread in the sun to air, are the government offices, low structures of frame and plaster, designed so as to admit a maximum of air and a minimum of heat; the long, low building of the Planters Club, encircled by deep, cool verandahs; a Chinese joss-house, its facade enlivened by grotesque and brilliantly colored carvings; and a down-at-heels hotel…At the summit of the hill, reached by a steeply winding carriage road, are the bungalows of the Europeans, their white walls, smothered in crimson masses of bougainvillea and shaded by stately palms and blazing fire-trees, peeping out from a wilderness of tropic vegetation.Footnote 32

In Jesselton, where there was less land, the town was not only built vertically from the water’s edge to higher ground but also stretched across the coast. This gave it a sprawling form, as described by a former district officer:

The Government offices and European bungalows upon the hills stand above the quaint houses of the Malay village below – a cluster of huts built of sago palm leaves over the mangrove swamp…Jesselton is a straggling little town, for each house is perched upon its separate hill. Government House and the Secretariat stand on a magnificent site overlooking Gaya Bay, two miles from the shops; a mile farther, at Batu Tiga, are Victoria Barracks, the head-quarters of the Constabulary, and the Jesselton golf links.Footnote 33

Both these descriptions took note of how the European quarters, comprising offices and homes, overlooked the other parts of the towns. From the hills, the Asian people who inhabited these areas might have appeared small, distant and unimportant. Indeed, Thomas J. McMahon – the photojournalist cited at the beginning of this article – compared Sandakan’s ‘Asiatic town’ to an ‘ant-bed’, scarcely concealing his racist indifference.Footnote 34

Stretching from the shoreline to the foothills, the Asian quarters were a distinct part of the towns. This area contained several rows of shophouses and separate wet markets for fish, pork and vegetables. The Asian quarters were also known as the ‘business quarters’ because of their importance to daily commercial life in Sandakan and Jesselton.Footnote 35 An astonishing array of businesses were located on the streets of these ‘neighbourhoods’, including bakeries, bootmakers, coffeeshops, dentists, opium dens, pawnshops, photo studios and tailors.Footnote 36 The ubiquitous shophouses that contained these establishments, like those in Malaya and Singapore, incorporated the architectural feature of the ‘five-foot way’ or verandah – a sheltered walkway running continuously along the front of adjoining buildings.Footnote 37 In April 1906, the British North Borneo Herald, the territory’s English-language newspaper, published a note urging the municipal authorities in Jesselton ‘to persuade those towkays who pack their rubber for shipment in the five-foot ways’ to make room for pedestrians.Footnote 38 Just as Brenda Yeoh depicted in colonial Singapore, the two towns’ five-foot ways were congested and contested spaces, where municipal authorities and Asian shopkeepers jostled for control.Footnote 39 The Asian quarters were thus perceptibly different from the rest of Sandakan and Jesselton.

Besides the European preference to live apart from other ethnic groups, various Asian communities were left to settle in the lowlands of the towns because it was crowded, dangerous and noisy. Housing was scarce in Sandakan and Jesselton, and large numbers of Asians lived in cramped shophouses.Footnote 40 Motor vehicles with engines loud enough to disrupt radio operators drove through the streets, sometimes straining to climb steep inclines.Footnote 41 The towns’ waterfronts were especially unpleasant places because they were the nexus of economic and industrial activity, where all sorts of cargo were loaded and unloaded by Asian labourers. Moreover, raw sewage was commonly disposed of along the seashore through a system of public latrines and night-soil collectors. At low tide, the receding sea sometimes revealed miasmic deposits of sludge.Footnote 42 This was drastically different from life in the spacious bungalows that dotted the nearby hills.

Despite the modest size of Sandakan and Jesselton, their different Asian communities were spatially segregated. As detailed in the preceding section, the towns were spaces predominantly occupied by non-indigenous peoples. Census and newspaper records suggest that so-called ‘native’ or indigenous peoples lived in villages at the town’s edge in Sandakan, separate from the non-indigenous Asians that inhabited the Asian quarter.Footnote 43 In ‘straggling’ Jesselton, so many Chinese people lived in the shophouses near the pier that it was identified as ‘the Chinese town’ at times. Just south of this area was a place known as Kampung Air, which was often clumsily described as ‘the native kampong’. It consisted of a row of houses, built on stilts along the shore, which were inhabited by a sea-oriented community of indigenous Bajau people.Footnote 44 Some evidence also indicates the Asian quarters of the towns were themselves segregated, with people from the same ethnic group tending to live near each other. In 1933, government surveyors drew a layout of a section of Sandakan’s waterfront, which detailed the location of several residential houses and the names of their inhabitants. The layout showed that people with Arabic and Malay names lived in the western portion of the depicted sector. Separated by the old wharf and boatyard, the eastern portion of the sector was inhabited by people with Chinese names.Footnote 45 While these residential patterns did not necessarily inhibit interethnic interaction, they do indicate that different Asians occupied separate parts of the towns and their suburbs that were comparable to neighbourhoods.

Social life in Sandakan and Jesselton mirrored their spatial divisions. Even if communities were only set apart by a building, a hillside or a street, these boundaries symbolized a divided world. Danny Wong went as far as to state that the towns’ various ethnic groups ‘normally stayed in their respective quarters, leaving very little room for interaction’.Footnote 46 While cross-communal interactions did exist in the towns, there were also clear boundaries, as evidenced by the types of social clubs and civic associations that operated there.

Clubs were an important aspect of social life for individuals of moderate and elite status – such as clerks, government officials, merchants, planters and teachers – regardless of their ethnicity. However, many were highly exclusive, with memberships that were restricted by ethnicity. In the colonies of South and Southeast Asia, clubs were originally created as private spaces where Europeans could unwind and socialize over a drink.Footnote 47 Likewise, the European community in North Borneo also had their own clubs. The oldest in the territory was the Sandakan Club, which was established in 1884. It was the heart of European life on the eastern coast, offering members access to modest but familiar comforts: a bar, a reading room and dining facilities. The Sandakan Club also hosted dances and dinners, especially when important visitors, like British naval officers, were in port.Footnote 48 In 1903, the Jesselton Sports Club, known also as the Jesselton Club, was founded to fulfil the same social functions for the European community on the western coast. It was where they privately gathered to celebrate festive occasions like Christmas and New Year’s Eve. Even when the Jesselton Club hosted a children’s Christmas party in 1927, only European children were invited.Footnote 49 There were also other clubs, usually organized around a sport, such as the Sandakan Tennis Club and the Jesselton Golf Club.Footnote 50 Nonetheless, membership in these clubs was also solely reserved for Europeans, although the occasion of World War I resulted in some changes. According to the rules of the Sandakan Club in 1915, ‘[p]ersons of German, Austrian and Turkish nationality, Asiatics and Eurasians’ were not allowed to be members.Footnote 51 Seen in another light, the club was so particular about ethnicity that Asian and Eurasian people were treated the same as enemy aliens.

Excluded from these Europeans-only clubs, the Asian communities of the towns founded their own associations and clubs. They emulated the British model of club life in the same fashion that Asians in urban Malaya did.Footnote 52 As the largest ethnic group in the towns, the Chinese had numerous societies in Sandakan and Jesselton, like clan associations, reading clubs and social clubs. The oldest Chinese club in Sandakan was the Yee Lok Kee Low, which was probably founded in the 1880s or 1890s.Footnote 53 In the 1930s, the most prominent Chinese club in Jesselton was the Yi Yi Club, which was located on the second floor of the local Chinese Chamber of Commerce. Its members consisted of shopkeepers, planters and ‘eminent members’ of the Chinese community.Footnote 54 Like their European counterparts, these clubs hosted celebrations and gatherings. In 1922, on the tenth anniversary of the establishment of the Chinese Republic, the Chinese community in Sandakan held ‘dinners at all the Chinese Clubs’.Footnote 55 Some of the reading clubs – including the Chung Hwa Reading Club in Sandakan and the Ming Sim Reading Club in Jesselton – also operated as propaganda centres for the anti-Qing Tongmenghui (Revolutionary Alliance).Footnote 56 The presence of so many Chinese clubs aroused the misgivings of the government on occasion. When gambling was outlawed in the territory in the early 1930s, the constabulary surveilled several Chinese clubs and suspected many of being gambling houses.Footnote 57 Not only did this reflect some tension between the community and the government, but also the fact that the latter was shut out from the spaces of these Chinese clubs.

Other Asian communities also had their own exclusive clubs, at least in Jesselton. Founded in 1929, the Japanese Society of Jesselton had a membership that was ‘confined to local Japanese’. It typically held celebrations that were centred on its own community, such as the birthday of Emperor Hirohito.Footnote 58 The Jesselton Muslim Club, which presumably only counted the faithful among its members, opened on Hari Raya Puasa (Eid al-Fitr) in 1933. That same year, it hosted the famed Khalid Sheldrake – an English manufacturer and Muslim convert – who gave a lecture at the club.Footnote 59 Although Sandakan had sizeable non-Chinese Asian communities, they appeared not to have formed their own exclusive associations.

Taken together, the socio-spatial boundaries present in Sandakan and Jesselton indicate the presence of neighbourhood-like spaces that were fractured along ethnic lines. Civic and commercial collaboration between different groups existed, especially between the Chinese and European communities, but this did not result in social integration. This was somewhat similar to social life in colonial Hong Kong, where Chinese and British elites – despite sharing the common goal of creating a stable and thriving economy – ‘led largely separate lives and built parallel clubs and associations’. Theirs was thus a collaboration that, according to John Carroll, occurred within ‘a system of social segregation’.Footnote 60

Moving between boundaries

Even though they were a palpable presence, the socio-spatial boundaries of the ‘neighbourhoods’ in Sandakan and Jesselton were never so rigidly enforced as to be impermeable. There were opportunities for interaction between different ethnic and social groups – what mattered was where and when they took place, and who was involved. The porosity of these social and spatial divisions was a feature of life in the two colonial towns.

While most of the clubs in the towns had ethnic restrictions, associations like the Sandakan Recreation Club and the Jesselton Recreation Club were open to men regardless of their ethnicity, although they remained closed to women. Respectively established in the late 1880s and the mid-1910s, these recreation clubs were meant for the non-European staff of the government and commercial firms in North Borneo. They had bar facilities where members – which included Chinese, Eurasian, Japanese, Malay and South Asian people – could socialize over drinks.Footnote 61 The recreation clubs also organized sports games for their members, often sending teams to compete in matches, usually cricket or football, against local and visiting teams. They so frequently assisted in organizing entertainment or sports matches for the crew of visiting ships that the government even regarded the clubs as a ‘valuable institution’.Footnote 62 The personal bonds of the recreation club members, which cut across communal divides, could be profound. When the chief cashier of the Sandakan treasury, a Chinese man, retired after 25 years of service in 1928, his Eurasian and Japanese friends at the Sandakan Recreation Club organized a farewell party for him.Footnote 63

Beyond the insular walls of clubs, the towns’ eateries served as sites of interaction between people of various ethnicities. After retiring as North Borneo’s chief opium farmer in 1905, Lim Paik Kiew hosted a farewell dinner at a restaurant in Sandakan for a party of 2 Chinese and 13 European men. The opulent 15-course dinner consisted of delicacies such as bird’s nest soup, shark fin stew and suckling pig.Footnote 64 The inclusion of pork on the menu, however, would have precluded the participation of practising Jews and Muslims. E.N. van der Straaten, a Eurasian government clerk, wrote that ‘Chinese tea kedeis’ – literally translated as tea shops – were ‘the hubs of the town life of the native population’. In these places, ‘the raw Dusun and Bajow rubs shoulders with the Chinese and Malay’, exchanging gossip and discussing news over coffee, tea or cigarettes.Footnote 65 In these eateries, in full view of the public, the social worlds of Sandakan and Jesselton overlapped, if only just barely. Yet, like the recreation clubs, they were mostly masculine spaces.

Socialization between individuals of different ethnicities, such as the men in tea kadeis depicted by van der Straaten, was made possible by a shared knowledge of the Malay language. Malay was the lingua franca in the towns, as it was throughout the territory, although levels of fluency varied.Footnote 66 This was also reflected by the widespread popularity of Malay-language travelling theatres, especially bangsawan companies from Malaya or toneel troupes from the Netherlands East Indies, that frequented Sandakan and Jesselton during the early twentieth century. In 1932, the British North Borneo Herald reported that all of Sandakan was enchanted by four weeks of performances by Miss Riboet’s Malay Theatre Company (Maleisch Toonel Gezelschap): ‘It is also to be expected that the Malay version of Marseillaise will soon be Sandakan’s popular song.’Footnote 67 Malay was thus vital for cross-cultural communication and connection in the towns, especially for people outside the colonial elite.

Townspeople also had opportunities to move between communal boundaries during public celebrations, festivals and sports meets. From the 1880s to the 1930s, Sandakan hosted numerous flower shows – often around the Lunar New Year – boasting boat races, exhibits for local products, horticultural competitions and various sports competitions.Footnote 68 These shows began as a scheme to encourage the people in and around the growing settlement to produce food and potential export crops, but they gradually became a general holiday enjoyed by the whole town. The British North Borneo Herald reported the names of various people – Chinese, European, Filipino, indigenous and Malay – who won prizes for categories such as ‘best display of jungle produce’, ‘the fattest pig’ and ‘sugar cane, best 10 stalks’.Footnote 69 In Jesselton, pony racing was a wildly popular multiethnic sporting event, drawing large crowds of Chinese European and indigenous peoples, some of whom would travel from the hinterland for races. Since its opening in 1910, several annual and irregular races took place at the Jesselton race course, located in the outskirts of the town.Footnote 70 Wealthy individuals and companies, both Asian and European, even funded prizes for these races.Footnote 71

In both towns, certain festivals staged by the government were meant to include everyone regardless of their ethnicity, including Christmas, Empire Day and even celebrations in honour of the British royal family. During the Silver Jubilee of George V in 1935, large celebrations were held across North Borneo. Government officials, Europeans, leading members of Asian communities and school children were present for a morning parade in Jesselton, before the town held a day-long programme of sports, processions and shows. Organized by a multiethnic committee, the Jubilee celebrations in Sandakan were held all weekend, consisting of a ‘Chinese dragon procession’, a march-past, ‘native dancing’, a schoolchildren’s parade and numerous sports matches – cricket, football and tennis.Footnote 72 On the first day of each November, the government observed a holiday called Charter Day, being a commemoration of the day that the British North Borneo Company was granted its royal charter. Plenty of Asian and European merrymakers participated in the parades, fairs and sports competitions that were held in both towns. During the 50th anniversary of Charter Day in 1931, ‘a large gathering of Europeans, Chinese and Natives’ were present at the ceremonial parade in Jesselton.Footnote 73 Nevertheless, these were events that took place in orchestrated sites and moments. Despite their festive atmosphere, the gatherings of these cosmopolitan crowds largely served as a means of celebrating and cultivating respect for the British imperial project.

At the upper echelons of colonial society, individuals of high status – whether acquired through official appointments, titles or wealth – had potentially more profound cross-cultural relationships. Governors of North Borneo occasionally invited leaders of Asian communities to private ‘At Home’ parties, likely as a way of maintaining friendly relations with them. During one such occasion in September 1927, the governor invited Europeans and ‘the leading Chinese of Sandakan’ to the Government House for tennis, dancing and card games.Footnote 74 At times, the towns’ European clubs also hosted distinguished Asian guests, although they were not allowed to be regular members. In December 1913, Dr W.T.B. Sia – the first Chinese consul general to North Borneo – and his wife attended a dance at the Jesselton Club.Footnote 75 Likewise, Asian clubs sometimes hosted Europeans and government officials. In June 1932, the Japanese Society of Jesselton threw a retirement party for S.W. Russells, the former government printer.Footnote 76 The Muslim Club held a tea party in August 1934 to honour C.A.V. Lingam, a Ceylonese man who was deeply involved in the civic life of Jesselton.Footnote 77 In a sense, high-status Asians and Europeans almost formed a distinct social group of their own, one in which class mattered as much as, if not more than, ethnicity.

In contrast to the use of Malay by the general population in Sandakan and Jesselton, fraternization between Asian and European elites was the preserve of those with a familiarity with the English language. In these colonial towns, the dynamics of power were such that its subjects found themselves compelled to make accommodations for its functionaries, not the other way round. In this case, it meant speaking in English – instead of the many Asian languages used by the towns’ inhabitants – at the Government House, Europeans-only clubs and private dinners. Even by 1931, however, there were few anglophones in Sandakan and Jesselton, which respectively formed about 9 per cent and 15 per cent of their total populations.Footnote 78 In other words, the sort of interethnic mingling practised by individuals at the higher end of the towns’ social hierarchy was not a widespread phenomenon; it was circumscribed by a proficiency in English. In early twentieth-century Kuching, too, there was a multiethnic class of ‘social brokers’: Westernized Chinese, Dayak, Japanese, Malay and Tamil people who were connected by ‘a fluency in the English language’ and ‘the adoption of some elements of British culture’. Because of this, Lockard argued that the members of this social group only embodied ‘an elite, not a mass, phenomenon’.Footnote 79 The same was true for the colonial towns of North Borneo, where sociability amongst multiethnic elites disregarded vernaculars.

Conclusion

In the colonial towns of North Borneo, the neighbourhood was not a category of space that was recognized by colonial officials or local inhabitants. Yet there were multiple quarters that were analogous to neighbourhoods in both Sandakan and Jesselton. The colonial economy created demographically diverse towns, where class, ethnicity, gender and language were significant categories of difference during the first half of the twentieth century. Deploying the notion of the neighbourhood in studying the two towns reveals how their urban environments were spatially and socially constructed. These quarters had distinct but permeable boundaries, largely drawn along ethnic lines.

Identifying the contours of neighbourhood-like spaces in Sandakan and Jesselton also affords a glimpse to how their boundaries could be transgressed. To begin with, the smallness of the towns made some degree of interethnic contact unavoidable. Each group was acutely aware of the presence and proximity of the others; they could see, hear, smell and walk alongside them. In addition to this, at specific locations and on certain occasions, townspeople were able to pass through the boundaries of their social worlds, perhaps some even felt drawn to do so. Eateries and the recreation clubs served as venues for interethnic interactions, while public celebrations gave different peoples an opportunity to gather. Proficiency in a shared language enabled cross-communal communication and sociability too. What emerges is a complex portrait of social life in two colonial towns in Southeast Asia, one that stubbornly resists clear generalizations.

Several implications can be drawn from this history of Sandakan and Jesselton. First, the neighbourhood is a relevant and meaningful conceptual category, even when examining small colonial centres. Even if they did not exist in the official or vernacular vocabulary, equivalent forms of such spaces were present. At the same time, the ‘neighbourhoods’ of colonial towns were different from their counterparts in larger urban places. They were probably smaller, less likely to be officially recognized and, as this article has demonstrated, more conducive to interethnic engagements.

Second, assessing the degree of segregation or interaction between ethnic groups in the towns is not only difficult, but seems rather pointless. This article has shown that both alienation and association existed alongside each other. The towns were thus spaces of ambiguity, where shifting social contexts and diverse individual identities coloured cross-communal interactions. Instead of using dichotomous frameworks, it is more productive to understand the nature of colonial urban society by asking a series of probing questions. In what ways exactly was a given colonial centre divided? How did it come to be stratified in such a manner? How strictly enforced were these social divisions? Who were able to bridge these divides? When, where and why were they able to do so? The observations derived from these questions promise to capture a sense of the contingency that came with living in colonial urban spaces.

Finally, the article has also revealed that the form of urbanism in North Borneo had analogues elsewhere in the colonial world. Surveying a broader range of urban forms, across varying magnitudes and roles, might yield a fuller appreciation for what exactly the ‘distinct ecology’ of colonial urban centres was.Footnote 80 Exploring the histories of colonial towns will establish the basis for more expansive perspectives on colonial urbanism.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Avner Ofrath, Norman Aselmeyer and the anonymous reviewers for their comments, generosity and insights. In addition, I thank Catherine S. Chan, John Darwin, Bernard Z. Keo, Katon Lee and Michael Montesano for their feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Funding statement

This research was supported by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Academic Research Fund Tier 1 RS06/21. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not reflect the views of the Ministry of Education, Singapore.

Competing interests

The author declares none.