Introduction

Education is increasingly identified as the master variable structuring an emerging political divide between the new left and radical right (Abou-Chadi and Hix Reference Abou-Chadi and Hix2021; Attewell Reference Attewell2022; Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010; Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2024; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008; Marks et al. Reference Marks2023; Stubager Reference Stubager2009). Essentially decoupling its explanatory power from income or occupation, educational attainment has become a strong predictor of attitudes and voting on a newer, more socio-cultural dimension of political conflict (referred to variously as GAL–TAN, libertarian–authoritarian, universalism–particularism, etc.).Footnote 1 It plays a leading part in accounts of electoral realignment, whereby university graduates increasingly support new left parties while the radical right mobilizes successfully among the lower-educated (Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann, Kriesi and Beramendi2015; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019; Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Kitschelt, Rehm, Beramendi, Silja, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2022; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). This has even led some observers to identify emerging electoral conflicts as an overarching ‘educational cleavage’ (Stubager Reference Stubager2010; Marks et al. Reference Marks2023).

This paper takes a cleavage perspective on educational divides an important step further by considering education not only as an individual-level attribute but as a feature of individuals’ social networks (complementing a recent study by de Jong and Kamphorst Reference de Jong and Kamphorst2024). We are interested in whether electoral, identity, and attitudinal differences along a new cleavage are magnified when comparing individuals whose networks mirror their own education, as opposed to ‘cross-pressured’ individuals in countervailing networks. We define networks here as individuals’ non-familial close ties (friends, coworkers, etc.), while integrating parents and romantic partners in supplementary analyses. We thus proxy the notion of milieus central to cleavage theory and develop theoretical links from social network research to cleavage-related concepts such as collective identity.

Our approach goes beyond existing work on contemporary educational divides, which tends to treat education as an individual-level characteristic, whether as a marker of skill endowment (Hall Reference Hall2022, 21; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008, 7), an experience instilling values (see, for example, Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010, 24, 63; Cavaillé and Marshall Reference Cavaillé and Marshall2019; Gelepithis and Giani Reference Gelepithis and Giani2022; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994, 17, 281; Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2022, 5; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008, 7; Stubager Reference Stubager2008), or the consequence of self-selection based on previous socialization experiences (see, for example, Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Kamphorst2025; Kuhn et al. Reference Kuhn, Lancee and Sarrasin2021; Lancee and Sarrasin Reference Lancee and Sarrasin2015). We draw on older strands of cleavage research (Bartolini and Mair Reference Bartolini and Mair1990; Lipset Reference Lipset1959; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1999) and other studies that recognize individuals’ social context as central to understanding their worldviews, attitudes, and voting behavior (Hall and Lamont Reference Hall and Lamont2013; Lazarsfeld et al. Reference Lazarsfeld, Berelson and Gaudet1944; Lindh et al. Reference Lindh, Andersson and Volker2021; Zuckerman Reference Zuckerman2005). Contemporary work on educational divides has yet to fully take this into account, despite evidence of segregating dynamics in knowledge-based societies (Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019).

Beyond applying old political-sociological theories to a transformed context, considering networks helps us address a fundamental puzzle in contemporary cleavage research: how a new cleavage achieves its structuring power in the absence of a clearly identifiable organizational basis. Historical accounts of cleavage formation emphasize the importance of unions or religious organizations in mobilizing social groups politically (Bartolini Reference Bartolini2000; Bellucci and Heath Reference Bellucci and Heath2012; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas1998; Korpi Reference Korpi1983; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1999). Such organizations also ‘encapsulated’ voters in their everyday lives (say, through social clubs), institutionalizing their embeddedness in specific milieus (Dassonneville Reference Dassonneville2023; Lorwin Reference Lorwin1971; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1977).

Yet today, there are no powerful member-organizations articulating the competing political interests of, for example, the vocationally educated or university graduates. New left and radical right parties mobilizing an emerging conflict lack obvious institutionalized links rooting them in everyday social interactions. We suggest networks emanating from educational and subsequent occupational trajectories may provide a partial substitute for such formalized associational understructures of political mobilization, especially in modern knowledge economies where educational groups are segregated in both workplaces and neighborhoods (Card et al. Reference Card, Heining and Kline2013; Consiglio and van Staalduinen Reference Consiglio and van Staalduinen2024; Ford and Jennings Reference Ford and Jennings2020, 307–8; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019; Mijs and Roe Reference Mijs and Roe2021). Our account contrasts with (early) arguments that educational expansion would fuel political dealignment through ‘cognitive mobilization’ (Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Flanagan and Beck1984; see also Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Kitschelt, Rehm, Beramendi, Silja, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015, 183).

We fielded a survey in Germany, Switzerland, and the UK, in which we used a name generator to ask respondents about four of their closest contacts. The case selection spans very different education systems (UK versus Germany and Switzerland; see, for example, Busemeyer Reference Busemeyer2015) and countries at advanced versus earlier stages of electoral realignment (Switzerland versus the UK and Germany) (Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021; Reference Bornschier2024). This allows us to demonstrate common patterns in how networks relate to a new cleavage across advanced knowledge societies with different institutions and historical conflict structures.

The main innovations of the survey lie, first, in measuring network composition in terms of education level and field (expanding on Damhuis Reference Damhuis2020 and Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Kamphorst2025). This is relevant because field of study is gaining attention as graduates expand and diversify as a group. Second, beyond standard political outcome variables (for example vote choice), our survey includes measures of potential mechanisms informed by cleavage theory (political attitudes and group identification), thus complementing recent work by de Jong and Kamphorst (Reference de Jong and Kamphorst2024) and building on research highlighting the importance of collective identities for cleavage stablization. We also provide rich descriptive evidence on where respondents met their closest contacts and how frequently they talk about politics.

Our central finding is that individual-level educational divides are absent in the presence of strong countervailing networks but amplified when network composition reinforces individual-level education. This applies to educational level and (to a lesser extent) field. The finding is remarkably consistent across various outcome variables related to the newer ‘universalism–particularism’ conflict, ranging from vote preference to universalist identities and immigration attitudes. We generally do not find the same pattern for outcomes associated with the ‘older’ state–market divide, supporting the notion that the educational composition of networks contributes to the formation of a new cleavage structure. We theorize interlocking processes of self-selection into networks over the life course and direct network effects that reinforce predispositions, provide lifestyle templates, cement worldviews and identities, and crystallize attitudes and opinions (for example through prevalent norms, imitation, status preservation, conversation, etc.) as underpinning these main results.

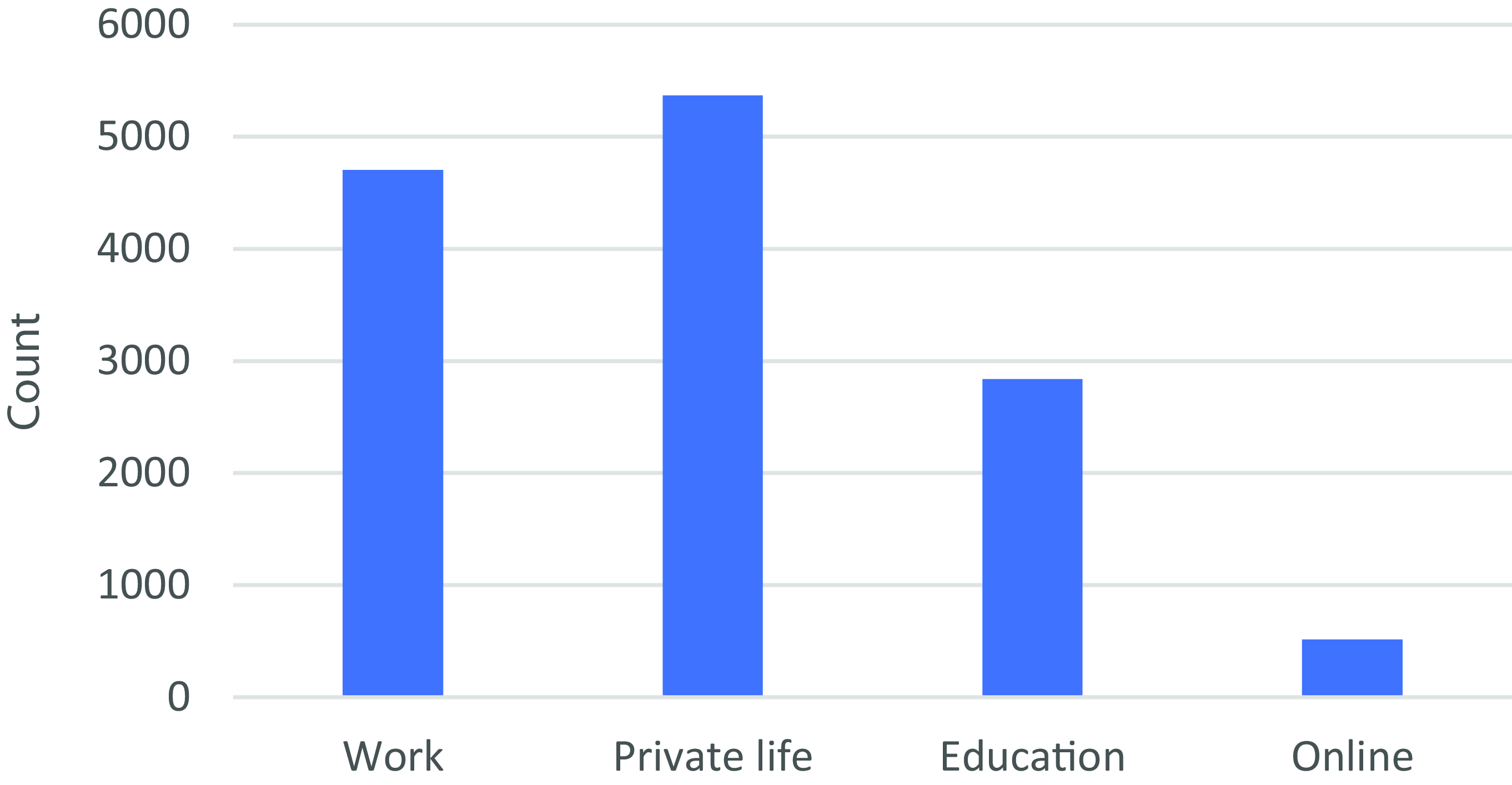

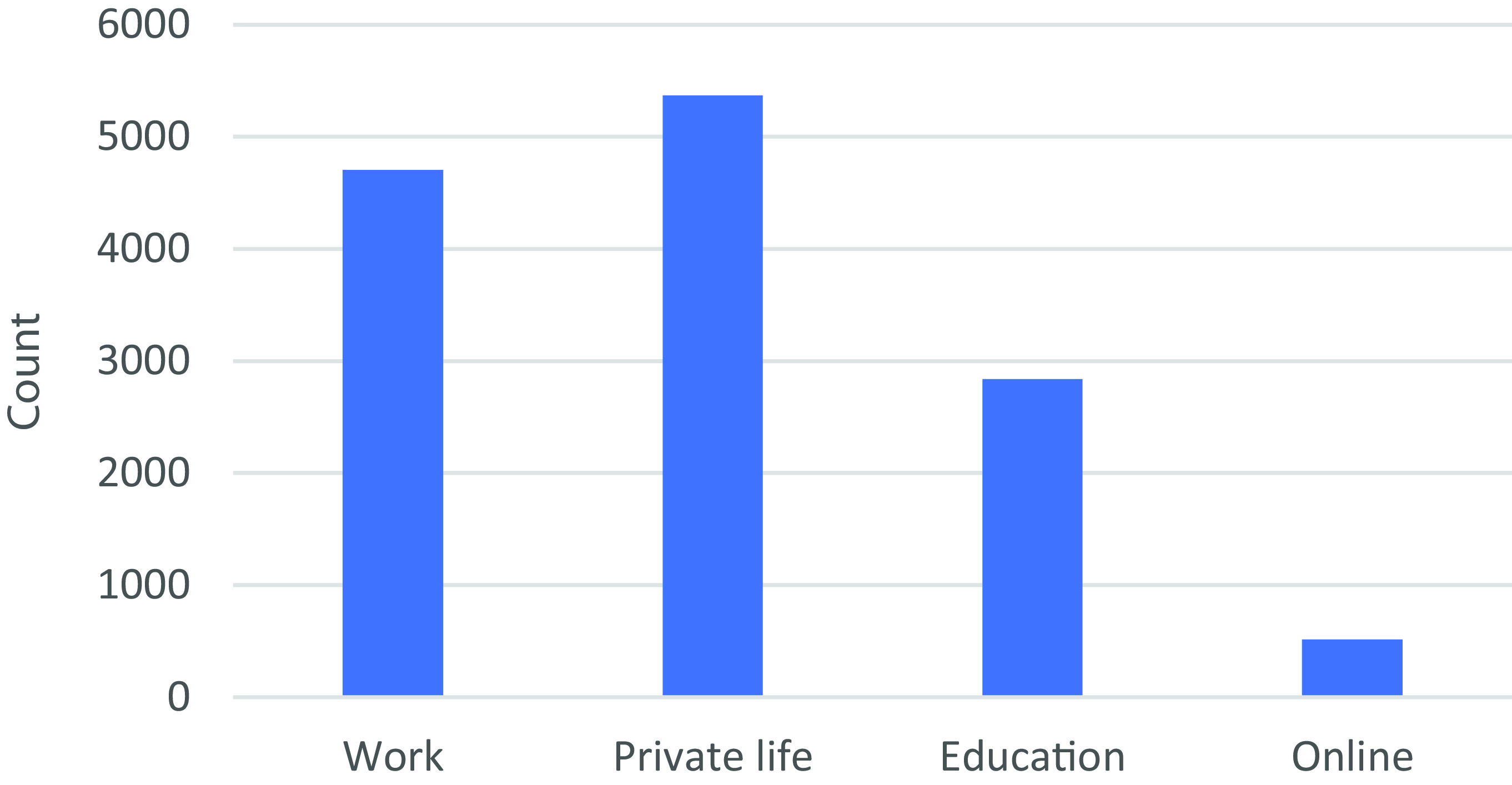

Our data indicates that – even in an age of increasing online interactions – the physical space remains central to social embeddedness and cleavage structures. Few respondents named online acquaintances among their main contacts. Private life, the workplace, or school/university appear much more formative for close social networks. Our data also reveal significant segregation by educational level, but also to a lesser degree by field. While social media bubbles might matter for political divides, a more old-fashioned perspective on social milieus has not lost importance.

We want to clarify two things that this paper does not aspire to do. First, working with cross-sectional observational data, we cannot empirically separate causal effects of educational networks from self-selection into educational networks.Footnote 2 This is not just the case for our study, but for most literature on individual-level education effects. However, for the puzzle of what provides the lifelong ‘glue’ anchoring individuals politically in the absence of formal organizations, the question of causality is less concerning to us. Even if ideological inclinations from early in life were decisive, we are interested in the structures stabilizing these predispositions and anchoring them politically as new issues arise and party systems fragment and change.

From a political–sociological perspective, we also do not aim to quantify how networks stemming from school or university matter more than, say, networks related to occupation or family background. Rather than conceiving of occupational versus educational network characteristics in a horse-race framework, we think of educational trajectories as particularly relevant precisely because they shape the private and professional contacts individuals have in later life.

Our findings have implications for how polarization associated with a new cleavage might be mitigated. In line with an old idea in cleavage theory, our evidence points to how cross-cutting networks might dampen identity-based animosities. In the context of ongoing debates on partisan affective polarization (Gidron et al Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Wagner Reference Wagner2021) or social media echo chambers (Sunstein Reference Sunstein2018; Terren and Borge-Bravo Reference Terren and Borge-Bravo2021), we stress the role of social structure and stratifying institutions. Managing cleavage conflict is not a matter of one-off interventions designed to foster deliberation or ’seeing the other side’, for example in the online space. Education, labor market, and housing policies shape segregation in social networks. This study suggests that such policies are not only consequential for the inequalities underpinning a new cleavage, but also for whether its democratic negotiation takes a more or less polarized and acrimonious form.

Education as an Individual-Level Characteristic

Political divides between people with and without higher education have deepened across advanced democracies. Educational attainment has become a robust predictor of support for radical right versus new left parties. Higher-educated individuals also consistently adopt more progressive positions on social issues such as immigration, gender equality, minority rights, or climate protection (Abou-Chadi and Hix Reference Abou-Chadi and Hix2021; Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi2015; Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010; Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021; Reference Bornschier2024; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2022; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008; Marks et al. Reference Marks2023). Thus, education – or the related distinction between a lower-educated working and ‘old’ middle class as opposed to a higher-educated ‘new’ middle class – is considered essential for understanding the emergence of a more socio-cultural dimension of political conflict.

Education as an individual-level determinant of political behavior has drawn attention because it plays a central role in electoral realignment, whereby the traditional working class has become overrepresented in the radical right electorate, and highly educated middle class voters increasingly support new left parties (Gingrich and Häusermann Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015; Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Kitschelt, Rehm, Beramendi, Silja, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2022; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). As a result, educational divides have become less closely tied to traditional patterns of class conflict. In the mid-twentieth century, education and income were strongly correlated in their effects on political behavior, with higher education associated with voting for right-wing parties and lower education associated with voting for the left (Gethin et al. Reference Gethin, Martínez-Toledano and Piketty2022, 16). Today, this pattern has reversed in almost all developed democracies, driven by educational groups’ ties to new left and radical right party families (Abou-Chadi and Hix Reference Abou-Chadi and Hix2021).

A well-developed literature offers different mechanisms linking education as an individual-level characteristic to political attitudes, which are likely simultaneously at play. From a political economy perspective, educational attainment has become key for life chances in post-industrial economies (Garritzmann et al. Reference Garritzmann, Garritzmann, Häusermann and Palier2022; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019). The share of the population with a tertiary degree has expanded massively as technological change has increased the demand for cognitive, interpersonal, and creative skills. The higher-educated have long been identified as relative ‘winners’ of modernization, while those with lower-to-medium education are considered among the ‘losers’, their skills devalued. Education hence determines who is equipped to benefit from the opportunities offered by the knowledge economy, as well as who feels well-placed to adapt to this fast-changing environment (Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi2015; Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008; Kurer Reference Kurer2020; McNeil and Simon Reference McNeil and Simon2024). From this perspective, there is a rational, self-interested element to educational groups’ varying propensity to support the radical right, which promises to turn back the clock on social change. A vast body of literature links education not just to immediate material outcomes but to concerns about status and identity as important drivers of political behavior (Attewell Reference Attewell2022; Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2024; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Zollinger2023; Kurer and van Staalduinen Reference Kurer and van Staalduinen2022; Mutz Reference Mutz2018).

Other theoretical perspectives link higher education to values underpinning greater acceptance of progressive societal change. Some argue that education itself socializes students into a set of social and political perspectives, either directly via classroom instruction (Cavaillé and Marshall Reference Cavaillé and Marshall2019; Gelepithis and Giani Reference Gelepithis and Giani2022; Stubager Reference Stubager2009, 329–32) or through interactions with classmates (Mendelberg et al. Reference Mendelberg, McCabe and Thal2017). The idea that educational experiences have a ‘liberalizing effect’ has figured prominently in accounts of electoral realignment (Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2022, 5, 38–9; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008, 7). Relatedly, direct exposure to different social realities through interpersonal professions later in life (as a teacher, psychologist, social worker, etc.) may foster other-oriented values and perceptions of marginalized groups as deserving (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994, 199; Oesch Reference Oesch2006).

From another perspective, education effects on political attitudes about immigration (Lancee and Sarrasin Reference Lancee and Sarrasin2015), European integration (Kuhn et al. Reference Kuhn, Lancee and Sarrasin2021; Kunst et al. Reference Kunst, Kuhn and van de Werfhorst2020), or gender attitudes (Simon Reference Simon2022) are due simply to selection into education. These panel data analyses show individuals do not become more cosmopolitan while in education; they instead self-select into or out of education based on parental background. Those who pursue higher education tend to have educated parents and are socialized into a more cosmopolitan, progressive value structure, and vice versa for particularist lower-educated groups. Taking this into account, recent studies adopt a life course perspective, suggesting that while self-selection based on parental background plays an important role, value divides between educational groups widen during and after education (Ares and van Ditmars Reference Ares and van Ditmars2024; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Kamphorst2025).

Increasingly, this research pays attention not just to level but also field of education, both in terms of socialization and self-selection effects. A degree in business (or having parents with one) exposes individuals to a different normative environment to a degree in sociology (Damhuis Reference Damhuis2020; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Kamphorst2025; Ladd and Lipset Reference Ladd and Lipset1975; van de Werfhorst and Graaf Reference van de Werfhorst and de Graaf2004; van de Werfhorst and Kraaykamp Reference van de Werfhorst and Kraaykamp2001). Using a Bourdieusian framework, Damhuis (Reference Damhuis2020, 209) distinguishes degrees cultivating general/theoretical cultural capital (for example humanities, science/mathematics/etc., social sciences) from degrees focused on applied cultural capital (for example technical and engineering, economics and business, public order and safety, law). Educational fields associated with general/theoretical cultural capital are more closely linked to voting for new left parties, while educational fields associated with applied cultural capital are linked to voting for parties of the (radical) right. Relatedly, others focus on fields’ so-called Cultural, Economic, Communicative, Technical (CECT) content – whether they reward economic/business or cultural/artistic expertise, and whether they are communicative or technical – showing that people with cultural–communicative education tend to be to the left of and more progressive than those with more economic–technocratic education (Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2024; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Kamphorst2025; van de Werfhorst and Graaf Reference van de Werfhorst and de Graaf2004).

While this literature tends to treat education as an individual-level characteristic – whether as a labor market asset, a direct source of progressive values, or an indication of predispositions formed early on in life – each of these mechanisms could imply some degree of educationally distinct social networks. Our interest is hence not in disentangling these mechanisms, but in taking this literature as our starting point to study education as a feature of individuals’ social circles.

A relational perspective makes sense if we take claims about an educational divide solidifying into a fully fledged new ‘cleavage’ seriously, since this implies a deeply political–sociological perspective. Although much of the above-discussed literature is framed in precisely these terms (see, for example, Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010; Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021; Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2024; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008; Marks et al. Reference Marks2023; Stubager Reference Stubager2010), the literature on educational divides has yet to fully consider the role networks might play in contemporary cleavage formation. While some of the theoretical arguments above clearly go beyond conceptualizations of individuals as atomistic entities (for example, by considering socialization experiences or parental background), they typically do not make networks themselves a theoretical and empirical object of study. As we argue next, doing so can help address a major puzzle about how a new cleavage achieves its structuring power, compared to the major twentieth-century cleavages of religion or class.

Education as a Feature of Social Networks

Claims about educational divides representing a full-blown new ‘cleavage’ predict an element of stability in political conflict (Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021; Reference Bornschier2024; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, 126–7; Westheuser Reference Westheuser2021; Westheuser and Zollinger Reference Westheuser and Zollinger2024). Work in the cleavage tradition draws a comparison to the classic class or religious cleavages that reportedly ‘froze’ into place for decades, at least in terms of their party-political representation (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2009). The dominant twentieth-century cleavages only gradually started to lose their structuring power in the face of fundamental socio-economic transformations ushered in by the postindustrial era.

If the educational cleavage today shares key qualities with these older cleavages, we would expect it to be similarly ’sticky’ and slow to fade. In many countries, new left and radical right parties have built consolidated, socially structured electorates (Abou-Chadi and Hix Reference Abou-Chadi and Hix2021; Bornschier and Kriesi Reference Bornschier, Kriesi and Rydgren2013; Dolezal Reference Dolezal2010; Marks et al. Reference Marks2023; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). Universalist–particularist conflict has become a staple of political competition, initially centered on socio-cultural issues but spilling over into distributive conflicts (Attewell Reference Attewell2021; Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021; Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann, Kriesi and Beramendi2015). It persists across elections and shapes how newly arising issues become politicized. The structuring power of this new cleavage seems comparable to that of past cleavages (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2025).

Yet the comparison to older cleavages focalizes a puzzle about the sources of this long-term structuring power in a twenty-first-century context. Historical accounts of cleavage formation and stability emphasize the role of unions and religious organizations in mobilizing social groups and forging group consciousness (Amat et al. Reference Amat2020; Bartolini Reference Bartolini2000; Bellucci and Heath Reference Bellucci and Heath2012; Korpi Reference Korpi1983; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas1998; Lorwin Reference Lorwin1971; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1977). Such organizations also ‘encapsulated’ voters in a more mundane sense, institutionalizing their embeddedness in social milieus. Full societal pillarization, with ‘competing networks of schools, communications media, interest groups, leisure time associations, and political parties along segmented lines’ (Lorwin Reference Lorwin1971, 142), represents an ideal-typical example. Even short of this extreme level of social closure, the central notion is that individuals’ everyday interactions, shared activities, and conversations used to be structured by formal organizations.Footnote 3 One of the most established observations of the realignment literature is of a decline – even collapse – of these mass organizations that shaped social and political life in the twentieth century.

Today, it is unclear what exactly holds the new cleavage together. It has an identifiable structural basis (see, for example, Abou-Chadi and Hix Reference Abou-Chadi and Hix2021; Marks et al. Reference Marks2023; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018) and identity element (Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021; Reference Bornschier2024; Steiner et al. Reference Steiner, Mader and Schoen2024; Stubager Reference Stubager2009; Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024a; Reference Zollinger2024b), but there are no powerful member-organizations articulating the competing political interests of, for example, the vocationally educated or university graduates. The parties mobilizing an emerging conflict lack obvious institutionalized links anchoring them in voters’ everyday lives, particularly given the decline of party membership (van Biezen et al. Reference Van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke2012; Scarrow Reference Scarrow2000). Although some may point to an individualization of modern societies, we can point to clubs or leisure activities associated with typically radical right or new left lifestyles (Flemmen et al. Reference Flemmen, Jarness, Rosenlund and Blasius2019; Florida Reference Florida2012; Savage et al. Reference Savage2013; Westheuser Reference Westheuser and Zollinger2024),Footnote 4 or with social movements and activist groups linked to these political camps (see, for example, Hunger and Hutter Reference Hunger and Hutter2021; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kriesi Reference Kriesi and Marks1999, Mierke-Zatwarnicki et al. Reference Mierke-Zatwarnicki, Borbáth and Hutter2025). Some might also point to the role of social media ‘echo chambers’ (Sunstein Reference Sunstein2018; Terren and Borge-Bravo Reference Terren and Borge-Bravo2021). Still, there are no obvious substitutes for the class- or religion-based organizations of the past, if we consider these institutions’ encompassing nature, their penetration into social life, and their formalized links to party politics (Dassonneville Reference Dassonneville2023; Westheuser and Zollinger Reference Westheuser and Zollinger2024).

From the perspective of this puzzle, we think it worthwhile to (re)consider less formalized (physical) social networks as alternative forms of cleavage ‘glue’. Pioneering cleavage scholars laid out two broad forms of social closure: one based on organization-building by parties, and one rooted more ‘naturally’ in social structure.Footnote 5 On the one hand, Lipset (Reference Lipset1959, 86–7) highlights partisans’ active endeavors to intensify and formalize intragroup interactions, with Catholics and Socialists attempting ‘to increase intra-religious or intra-class communications by creating a network of social and economic organizations within which their followers could live their entire lives’. On the other, he argues social structure may itself ‘isolate naturally individuals or groups with the same political outlook from contact with those who hold different view’ (1959, 86–7). Political cohesion can thus emerge from social structures fostering intragroup communication while hindering intergroup communication (1959, 248–9).Footnote 6 , Footnote 7

Renewing our focus on the role of social networks can help us to address the puzzle of cleavage formation and stability. Many have observed ‘centripetal’ forces at work in post-industrial knowledge economies fostering highly segregated social networks (Ford and Jennings Reference Ford and Jennings2020; Gingrich and Ansell Reference Gingrich and Ansell2014; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2019; Mijs and Roe Reference Mijs and Roe2021; Mijs Reference Mijs2023). The literature on deepening geographical inequalities in advanced democracies has proliferated in recent years (Hobolt and Tilley Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016; Huijsmans et al. Reference Huijsmans2021; Patana Reference Patana2022; Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018). The clustering of highly educated knowledge workers in urban innovation hubs appears to be an important factor driving residential segregation and inequality, pricing especially people without tertiary education out of the most attractive cities and neighborhoods (Adler and Ansell Reference Adler and Ansell2020; Moretti Reference Moretti2012). Workplaces, too, have become less integrated across skill-levels, as technological change has reduced complementarities between workers with high and middling skill-levels (Card et al. Reference Card, Heining and Kline2013; Consiglio and van Staalduinen Reference Consiglio and van Staalduinen2024; Iversen and Soskice Reference Iversen and Soskice2019; Mijs and Roe Reference Mijs and Roe2021). Lastly, education itself has become an ever more important part of early adult life, and hence for the formation of social networks – one that tends to cement pre-existing differences in parental background (Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2024, chap. 3; Garritzmann et al. Reference Garritzmann, Garritzmann, Häusermann and Palier2022; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Kamphorst2025; de Jong and Kamphorst Reference de Jong and Kamphorst2024,Stevens et al. Reference Stevens and Armstrong2008).

Cleavage Stabilization through Educational Networks

From a social closure perspective, we can think of education as having direct consequences for social networks, as perpetuating the effects of family ties and early childhood socialization, and as laying out a path for social network formation in adult life. While some network studies focus on empirically isolating specific causal effects of social influence (see Jackson Reference Jackson2009, 496–8), we theoretically build on sociological work that shows self-selection into educational (and occupational) paths and socialization effects to be mutually reinforcing. Recent evidence of progressively deepening attitudinal divides over the life course is compatible with viewing self-selection into socializing environments (jobs, friendship networks, etc.) at one point in life as affected by socialization earlier in life, reaching as far back as childhood predispositions (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Kamphorst2025, Ares and Van Ditmars Reference Ares and van Ditmars2024, see also Lindh et al. 2001, 698–9).

In our account, this implies an amplification of previously discussed individual-level mechanisms linking education to political attitudes (for level and field, see Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Kamphorst2025, 4–5). In a knowledge-based economy, people will tend to make friends with, be in relationships with, and work with others who share their skill endowments and broad set of life chances. Their social circles will also, on average, be made up of people who developed shared values due to similar socializing experiences on their educational trajectory – because they went to school or university together, because co-workers pursued similar degrees, or because friends of friends might have similar educational (and subsequently occupational) backgrounds. By shaping adult social networks, education may also contribute to stabilizing attitudinal predispositions that form earlier in life, as we continuously interact with others who might have self-selected into a similar educational path.

We can think of homophily with regard to all of these education-related traits as largely driven by structure and institutions (the workings of the knowledge economy, stratifying and segregating effects of educational and labor market institutions, etc.) but intensified by individuals choosing to interact, make friends, work, and start romantic relationships with others who resemble them – sometimes opting out of ties with those who do not (McPherson et al. Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001, Smith et al. Reference Smith, McPherson and Smith-Lovin2014). While social closure research emphasizes how such patterns may reflect efforts to draw symbolic boundaries and protect status (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984, Reference Bourdieu1987, 5–6, Lamont and Molnár Reference Lamont and Molnár2002, Mijs and Roe Reference Mijs and Roe2021, 3; also see Lindh et al. Reference Lindh and Andersson2024, 3), shared information, ease of communication, or common cultural tastes are additional self-selection mechanisms plausibly at work (McPherson et al. Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001: 435–6, Smith et al. Reference Smith, McPherson and Smith-Lovin2014, 434–7, Mijs Reference Mijs2023, 3, Christakis and Fowler Reference Christakis and Fowler2009, Jackson Reference Jackson2021).

All this leads us to expect a high degree of segregation in people’s close social networks, not just in terms of educational level but also in terms of field of study.

HYPOTHESIS 1 (segregation): Individuals’ level and field of education is reflected in the educational composition (level and field) of their close social networks.

We view close social ties as a proxy for the ‘milieu’ that has been the focus of cleavage research. While, for example, university-educated individuals are likely to count lower-educated contacts among their weak social ties,Footnote 8 we are most interested in the stronger ties that are particularly likely to influence individuals with respect to identities, attitudes, and vote choice. Especially if we consider that these forms of influence in social networks – over attitudes, behaviors, etc. – tend to spread across connections up to three degrees (friends’ friends’ friends’) (Christakis and Fowler Reference Christakis and Fowler2009, 27–30), we are approximating the notion of a milieu.

Existing literature points not only towards overt political discussion, but also a more subtle set of micro-mechanisms through which people imitate each other; sanction or endorse norms of behavior; share information, aspirations, narratives, or emotions; consolidate worldviews; shape one another’s opportunities; cultivate notions of (dis)similarity and group belonging; and help crystallize views on current affairs (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1987, 5–6, Lindh et al. Reference Lindh, Andersson and Volker2021, 968, Mijs Reference Mijs2023, 3, McPherson et al. Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001, 435–6, Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Kamphorst2025, 4, Jackson Reference Jackson2009, 503–6, Jackson Reference Jackson2021,Christakis and Fowler Reference Christakis and Fowler2009, for example 20–4, ch6, Hall and Lamont Reference Hall and Lamont2013, 7–10) – all against the background of earlier socialization experiences (Jennings and Niemi Reference Jennings and Niemi1968, Kuhn et al. Reference Kuhn, Lancee and Sarrasin2021, Lancee and Sarrasin Reference Lancee and Sarrasin2015).Footnote 9 In short, even if early life experiences are responsible for setting people on a path associated with radical right/new left voting, these mechanisms hold the theoretical key to the puzzle of contemporary cleavage stabilization: the question of how a new cleavage might consolidate, durably anchoring individuals and structuring political competition in predictable ways.

If, for an emerging universalism–particularism cleavage, these networks indeed fulfill some of the stabilizing functions that unions or church-related organizations once did, their composition should condition individuals’ anchoring within political divides. Highly educated individuals in homogeneously higher-educated networks should be particularly likely to support new left parties, and vice versa for the lower-educated and radical right parties. The well-known individual-level associations between educational attainment and voting should be reinforced in homogeneous networks, while voters in more heterogeneous networks are exposed to countervailing, less consistent social influence (Mutz Reference Mutz2002, Hobolt et al. Reference Hobolt, Lawall and Tilley2024, see also Dassonneville Reference Dassonneville2023, 2–3, Roccas and Bewer Reference Roccas and Brewer2002, Christakis and Fowler Reference Christakis and Fowler2009, 117). Again, this is plausibly due first to structural conditions and self-selection into more homogenous or mixed networks, but then perpetuated by exposure to those networks. Similarly, the association between educational degrees that are cultural/artistic/communicative in content with the new left on the one hand, and that between technical/economic/business degrees and the radical right on the other should be amplified in the presence of homogeneous networks.

HYPOTHESIS 2 (vote preference): Educational differences (level and field) in radical right and new left support are amplified (reduced) in the presence of reinforcing (countervailing) educational networks.

Beyond voting, networks should be related to attitudes and identity formation along the new cleavage. This follows from our discussion of micro-mechanisms, which we envision as more encompassing than individuals simply following their close ties’ votes in any given election. It is also implied by a cleavage perspective, which points towards a deeper permeation of the universalist–particularist logic into voters’ lives, identities, and worldviews. Our social closure argument relies on individuals developing notions of ‘us’ versus ‘them’. This group consciousness, once linked to a particular political camp, is what ‘narrows mobilization markets’ (see Rokkan Reference Rokkan1999; think of a working class identity historically linked to social democracy). Voters with strong social identities and distinct political attitudes become less available for alternative forms of mobilization.

For our puzzle about cleavage stability, networks help explain how core new left and radical right electorates come to form well-articulated group identities such as nationalist, rural, locally rooted as opposed to cosmopolitan, urban, feminist etc. (Stubager Reference Stubager2009; Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021; Reference Bornschier2024; Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024a). Network dynamics (shared norms, imitation, information flows, idea-sharing, etc.) may continually crystallize, say, what it means to lead a cosmopolitan urban life, how this manifests in perceptions of self and of others, and how individuals come to make sense of new political issues in consistently patterned ways – even amid economic, social, and political transformations. Homogeneous networks reinforce predispositions in terms of identity and outlook, supplying the templates for, and entrenching the expression of, those identities and the translation of worldviews into concrete opinions.

HYPOTHESIS 3 (identities): Educational differences (level and field) in universalist–particularist identities are amplified (reduced) in the presence of reinforcing (countervailing) educational networks.

HYPOTHESIS 4 (attitudes): Educational differences (level and field) in socio-cultural attitudes are amplified (reduced) in the presence of reinforcing (countervailing) educational networks.

The important flipside to this expectation is that political divides will be muted among individuals whose networks do not mirror their own educational characteristics. Even with strong segregating forces in the knowledge society, there is still room for cross-pressures (see Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1999). People move to go to university or for jobs but might retain childhood/youth contacts; they might pursue degrees allowing for a broad variety of occupational choices; or their occupational biographies might unfold in a non-linear manner. This is precisely the variation that interests us in assessing the anchoring role of social closure in a new cleavage.

If education indeed plays a particular role for a newer universalism–particularism divide, we should find that the association of educational networks with political outcomes is stronger when we look at this cleavage than when we consider the traditional state–market divide still associated with established mainstream parties. As discussed above, education has become decoupled from traditional class conflict, even as it has emerged as a key factor underpinning the successes of new left and radical right parties. In particular, the emergence of a new segment of highly educated middle class professionals who care about social justice, support redistribution, and demand social investment (Abou-Chadi and Hix Reference Abou-Chadi and Hix2021; Attewell Reference Attewell2022; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018) should blur the association between education and traditional forms of economic-redistributive conflict, including as a feature of networks. This should be particularly pronounced for network composition by educational attainment, since it is at graduate level (more than within fields of study) that higher-educated voters have become heterogeneous in terms of their economic-redistributive stances.

HYPOTHESIS 5 (new versus old cleavage): The moderating effect of educational networks and vote choice/attitudes/identities is stronger for the ‘new’ socio-cultural cleavage than for the ‘old’ socio-economic cleavage.

Case Selection, Data, and Methods

We fielded an online survey in Germany, Switzerland, and BritainFootnote 10 between 2022 and 2023. The motivation for our case selection is twofold. We cover a range of different political-economic and skill regimes – liberal in Britain, coordinated in Germany and Switzerland (Busemeyer Reference Busemeyer2015). This allows us to test whether there is evidence of network-reinforced cleavage formation across knowledge societies with very different political–economic institutions. Notably, vocational training systems with strong employer involvement in Germany and Switzerland are known to have directly stratifying effects, since early tracking reproduces inequalities in parental background. Meanwhile, the liberal education system (and broader liberal market economy) of Britain stratifies and segregates more indirectly, through market logics evident, for example, in the importance of private education spending (Iversen and Stephens Reference Iversen and Huber2008, Busemeyer Reference Busemeyer2015, Thelen Reference Thelen2014).

Second, we include in our sample countries where new left versus radical right opposition varies in terms of strength and consolidation. Switzerland is an example of an entrenched, socially structured, polarized divide between the new left and radical right (Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021, Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024a). The consolidation of a new cleavage at the level of party politics is comparatively less advanced but nevertheless visible in Germany and Britain (Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2024).

We recruited 5,100 respondents via the social research company Bilendi/Rispondi. Our sample includes respondents between 18 and 65, since elderly respondents would have been socialized in contexts predating mass educational expansion and the emergence of the educational divide.Footnote 11 We employed crossed gender, education, and age quotas to recruit a sample matching the 18–65-year-old population of each country, based on Eurostat data.

Measuring Network Composition

Following Lindh et al. (Reference Lindh, Andersson and Volker2021)’s measurement of class network segregation, we use a ‘name generator’ to study educational network segregation. We prompt respondents to reflect on an average week in their life, and ask ‘Who do you spend the most time with? Who do you do things with most often? Who do you have conversations with most often?’ Footnote 12 Existing work suggests this well-established wording elicits a mix of friends, coworkers, schoolmates, neighbors, etc. (Christakis and Fowler Reference Christakis and Fowler2009, 18; also see our Figure 2). We then ask about the level and field of education for each close tie. We ask about four close ties,Footnote 13 which our survey data indicates closely approximates the median number of close contacts respondents report having (consistent with previous research; see Christakis and Fowler Reference Christakis and Fowler2009, 18). This allows us to generate variables containing the share of close ties respondents have in each educational level and CECT group.

Key Independent Variables: Respondent Education and Educational Network Composition

For our initial descriptive analyses on network segregation, we code the education level of respondents and each of their close ties into an ordinal low/medium/high education measure. For the main regression models featured in our plots, we use a simpler binary measure of higher education (1 = university degree) v. lower education (0 = no university degree), to make our data visualization more legible.

To measure respondents’ educational field and the field composition of their network, we use CECT scores, which classify educational fields according to a dimension running from economic–technical (for example commerce, engineering) to cultural–communicative (for example, pedagogy, arts) fields. We assign each respondent and close tie a CECT score, using data from Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Marks and Kamphorst2025: Appendix pp. 5). Divides in educational fields lack the same theoretically clear break-point we observe with respect to education level. In our analyses, we thus code both respondents and their close ties as belonging to low, medium, or high CECT groups (see Appendix A for details). Our main analyses foreground the contrast between low and high CECT respondents, both for ease of presentation and because this is plausibly where political divisions may be strongest.

We are interested in how network homogeneity conditions the association between respondents’ education level (field) and our political outcome variables. Our measure of network homogeneity is the share of close ties with the same level (CECT group) of education as the respondent, ranging from 0 to 1. A value of 0 means all close ties have a different education level (CECT group) from the respondent, while 1 means all close ties share the respondent’s education level (CECT group). Key in our regression models is the interaction of respondents’ education*network homogeneity.

Dependent Variable 1: Vote Preference

Our main outcome variable as cleavage theorists is voting behavior. Our survey measures this in two ways: asking respondents who they voted for in the prior national election, and asking a 0–10 propensity to vote (PTV) question for each main party in the country, where 0 means ‘I would never vote for this party’ and 10 means ‘I would definitely vote for this party’. The pattern of network effects across both variables is similar. In the main analyses below, we report results of PTV scores for party families to pool results across our three countries and maximize our N. Of particular interest is propensity to vote for new left or radical right parties, which form the poles of the education cleavage (Attewell Reference Attewell2021; Dolezal Reference Dolezal2010; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Marks et al. Reference Marks2023; Stubager Reference Stubager2010).Footnote 14 We also present results in Appendix D for the Center-Right as a benchmark to compare effects of network homogeneity on preferences for a party family associated with older cleavages of class and religion. After analyzing vote preferences, we then assess how network composition conditions the association between education and two other dependent variables theorized to underpin cleavages: social identities and political attitudes.

Dependent Variable 2: Universalist Identity

Collective identities are the glue that cleavage theorists argue connects social groups to stable voting patterns. There is some evidence that individuals with different levels of education have education-based group identities (Kuppens et al. Reference Kuppens, Easterbook, Spears and Manstead2015; Stubager Reference Stubager2009). More indirectly, objective differences between educational groups have been shown to translate into antagonistic notions of group belonging, for example, into subjective differences between national versus cosmopolitan group belonging, ‘down-to-earthness’ versus ‘open-mindedness’, etc. (Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021; Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024a). Prior work has shown that closeness to different social groups associated with this universalism–particularism divide undergirds opposition between new left and radical right parties (Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2021; Bornschier et al. Reference Bornschier2024; Zollinger Reference Zollinger2024a).

To shed light on the relationship between collective identities and the educational composition of social networks, we include itemsFootnote 15 tapping the closeness of respondents to different groups associated with universalistic identities. Specifically, we included a reduced battery of identity items shown to be politically divisive along the lines of a new cleavage by Bornschier et al. (Reference Bornschier2021; Reference Bornschier2024), namely items asking about identification with/demarcation from university-educated people, cosmopolitans, people with a migration background, and feminists. We create an additive index out of these items (α=0.72); for ease of interpretation, we standardize the resulting index variable, universalist identity (mean = 0, SD = 1).Footnote 16 Positive values indicate feeling close to groups associated with universalism, while negative values indicate distance from these groups. For comparison with a more traditionally defined class conflict centered on redistributive politics (Hypothesis 5), we also asked about closeness to people with humble financial means.

Dependent Variable 3: Political Attitudes

The next set of dependent variables measures political attitudes along two key dimensions. We first report results on immigration attitudes, which are emblematic of educational divides on the universalism–particularism dimension. Immigration attitudes are captured by the item ‘Do you agree or disagree that immigration is bad for [German/Swiss/British] society?’, which ranges from 1 (‘Don’t agree at all’) to 7 (‘Very much agree’). As a benchmark, we also report attitudes related to income differences, a question representative of ‘first dimension’ attitudes related to state–market conflict (Hypothesis 5). The item wording is ‘Do you agree or disagree: for society to be fair, income differences should be small’ (again ranging from 1 (‘Don’t agree at all’ to 7 ‘Very much agree’).

Modeling and Controls

We estimate OLS regression models controlling for self-reported household income insecurity (an ordinal measure ranging from ‘very comfortable to live on current income’ to ‘very difficult to make ends meet’), rural/urban location (rural, suburbs or small town, or urban), gender, age, number of close ties reported (three or four), network size (a count of how many close friends respondents report having in total), father’s education level or CECT-tercile (to partially account for selection into networks), and country fixed effects. The general form of our models is:

Where for different models:

-

Y is either vote preference (PTV), identities, or political attitudes.

-

Respondent_education is either our binary education level or CECT (field) tercile.

-

Network homogeneity is the share of close ties with the same level or field of education.

-

β3 is our key parameter of interest.

In keeping with Clark and Golder’s recommendations for best practices in interpreting interaction models (Clark and Golder Reference Clark and Golder2023, 103), we do not focus on regression coefficients. Instead, we present predicted values of the dependent variable for university degree v. non-degree holders or low v. high CECT respondents, across the range of network homogeneity. We include full regression tables in Appendix B.

Results

Descriptive Evidence of Close Network Homogeneity

First, we look descriptively at network homogeneity in terms of education level and field. The top panel of Figure 1 shows the mean share of tertiary-educated close ties by the respondent’s own education level. The bottom panel of Figure 1 shows the mean share of high-CECT close ties by the respondent’s own CECT group.

Figure 1. Network homogeneity by education level (top) and field (bottom).

On average, higher-educated respondents report that over half their close ties have a university degree. This stands in sharp contrast to medium-educated and even more so lower-educated respondents, who on average report less than a quarter of their close ties having higher education (i.e. they report less than one close tie with a university degree). Differences in network composition by field are also visible, with high-CECT respondents (those whose field of education is high in cultural–communicative content) having about 40 per cent of their close ties being high CECT, in comparison to the 21 to 22 per cent estimated share for low- and medium-CECT respondents. However, networks both look less homogenous overall in terms of CECT and show less stark differences across respondents’ CECT. We thus find support for H1 (segregation), with stronger homogeneity in terms of level compared to field.

We also measure where respondents met their reported contacts. We offered respondents a large set of possible contexts, including an open-ended option. Figure 2 reports aggregated categories, capturing reported close ties for all respondents. In the digital era, the continued dominance of in-person interactions is noteworthy – respondents reported meeting only a tiny percentage of close ties online. Instead, a plurality of reported ties came from respondents’ private lives (neighborhoods, through friends, or various forms of associational life), followed closely by workplaces. Just under one quarter of close ties formed directly at school or university, making them relevant but not dominant contexts for adults’ close network formation.

Figure 2. Sources of close ties.

Close Networks and Vote Choice

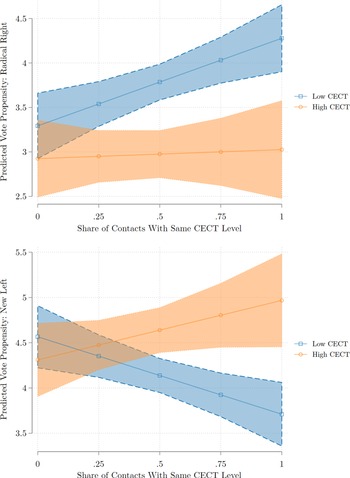

Our core question is how network homogeneity conditions the relationship between education and voting preferences (Hypothesis 2). Figures 3–8 show the predicted value of the dependent variable across the range of network homogeneity, under controls. Predicted values for those without a university degree are in blue (dashed outline), while those for respondents with a university degree are in orange (dotted outline). For analyses of network field composition, predicted values of the dependent variable for low-CECT respondents are in blue (dashed outline), and those of high-CECT respondents are in orange (dotted outline).

Figure 3. Radical right and new left voting by network homogeneity (ed. level).

The top panel of Figure 3 shows the predicted propensity to vote radical right across the range of network homogeneity in terms of education level. The bottom panel shows the equivalent for predicted propensity to vote new left. In both cases, the overall pattern is that the association between education and voting preferences is clearly conditioned by network homogeneity. For those in strongly countervailing networks (respondents with 0 to 25 per cent of close ties with the same level of education), degree divides in propensity to vote radical right or new left are not statistically significant. However, statistically significant differences in voting preferences by education level emerge at intermediate levels of network homogeneity and widen substantially at high levels of homogeneity. Non-university-educated respondents in the most homogenous networks are on average about 0.7 points higher on an eleven-point scale in their propensity to vote for the radical right, relative to university-educated respondents in the most homogenous (higher-educated) networks. In terms of the new left, university-educated respondents in the most homogenous networks are 1.6 points higher in their estimated support than non-university educated respondents in the most homogenous lower-educated networks.

The conditioning effects of network homogeneity in terms of field are similar. In the top panel of Figure 4, we see that differences in radical right voting propensity between low-CECT and high-CECT respondents are not statistically significantly different for those in countervailing networks (for example, respondents with 0 to 25 per cent of close ties with the same CECT level). At the other end of the spectrum, low-CECT respondents in the most homogenous low-CECT networks are on average predicted to have a propensity to vote for the radical right 1.25 points higher than high-CECT respondents in homogenous high-CECT networks.

Figure 4. Radical right and new left voting by network homogeneity (field).

In the bottom panel of Figure 4, we see that network differences by field are similar for new left voting. High-CECT respondents in the most homogenous networks are on average estimated to have a higher propensity to vote for the new left by 1.26 points, relative to low-CECT respondents in the most homogenous (low-CECT) networks.

In sum, our analyses indicate that educational divides in new left and radical right support are sharply weakened in the presence of countervailing or heterogenous networks. By contrast, network homogeneity is associated with amplified educational divides in voting preferences. This evidence is consistent with Hypothesis 2. Appendix D further shows that the moderating effect of educational networks is absent (level) or weaker (field) when we consider center-right support. In other words, today, educational networks appear to matter particularly for electoral choices associated with a new ’socio-cultural’ cleavage. This is a first piece of evidence in line with Hypothesis 5, which we also test in terms of identities and attitudes in the next step.

Close Networks and Identities/Attitudes

We have presented evidence that network homogeneity conditions the association between education and vote preference, and that this dynamic seems to be particularly pronounced for parties anchored in the newer universalism–particularism cleavage. We now analyze the relationship between network homogeneity and social identities (Hypothesis 3) and political attitudes (Hypothesis 4) theorized to underpin cleavages.

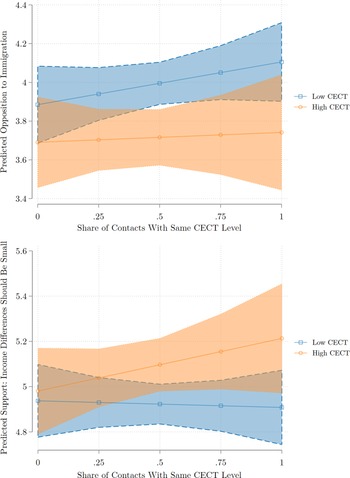

Identities: universalist identity v. closeness to people of humble means (level)

Below, we examine our social identity variable associated with the universalism–particularism divide (Hypothesis 3), and another associated with the older class cleavage (Hypothesis 5). We begin by examining network homogeneity by education level. In parallel to our findings on vote preference, the top panel of Figure 5 shows no statistically significant differences in predicted universalist identity between those with and without a university degree for those respondents with no close ties with the same education level. However, educational differences in universalist identity are wider at greater levels of network homogeneity. For those in the most homogenous networks, educational differences in universalist identity are estimated at half a standard deviation. The gap is driven entirely by university graduates, while the universalist identity of those without a degree does not appear to be sensitive to network homogeneity.

Figure 5. Universalist identity and closeness to people of humble means by network homogeneity (level).

In the bottom panel of Figure 5, we look at the relationship between education level and closeness to people of humble means by network homogeneity. The interaction between respondents’ level of education and network homogeneity in terms of level is weaker – educational divides in closeness to people of humble means reach statistical significance only at 75 per cent or higher network homogeneity, and are moderately sized at about 0.3 points on a seven-point scale.

Identities: universalist identity v. closeness to people of humble means (field)

In Figure 6, we do not find evidence of divides between low and high CECT respondents in either universalist identity or closeness to people of humble means, across the range of network homogeneity in terms of field. There seems to be a moderately negative relationship between network homogeneity and closeness to people of humble means within the high-CECT group. Overall, however, network homogeneity does not yield clearly estimated divides in social identities between people embedded in social circles with different composition in terms of field of education.

Figure 6. Universalist identity and closeness to people of humble means by network homogeneity (field).

Attitudes: first v. second dimension (level)

We now analyze the interaction between network homogeneity in terms of level and political attitudes on the universalism–particularism dimension (Hypothesis 4) and, for comparison, the state–market dimension (Hypothesis 5). As expected, we observe in the top panel of Figure 7 that the immigration attitudes of the university-educated and non-university-educated are not significantly different in countervailing networks. However, educational divides emerge at greater levels of network homogeneity, with the non-university-educated in the most homogenous networks estimated to be on average about 0.7 points more opposed to immigration on a seven-point scale than university-educated respondents in the most homogenous networks. As shown in the bottom panel of Figure 7, and as expected under Hypothesis 5 (comparison to the older state–market divide), we find no similar effect of network homogeneity on educational differences in support for small income differences.

Figure 7. Immigration attitudes and income egalitarianism by network homogeneity (level).

Attitudes: first v. second dimension (field)

Finally, in Figure 8 we examine the conditioning effects of network homogeneity in terms of field on educational divides in political attitudes. The overall pattern is similar, but more moderate and not as precisely estimated compared to network differences in education level. Differences in opposition to immigration between low-CECT and high-CECT respondents are muted at low levels of network homogeneity but grow in magnitude at high levels of network homogeneity, to about 0.4 points on a seven-point scale for both immigration and support for small income differences.

Figure 8. Immigration attitudes and income egalitarianism by network homogeneity (field).

Overall, we find strong levels of segregation in the educational composition of people’s close social ties, in keeping with Hypothesis 1. Our results show that social networks condition the association between individual-level education and voting preferences (Hypothesis 2), social identities (Hypothesis 3), and political attitudes (Hypothesis 4). Generally, these dynamics are more pronounced for education level, rather than field, and for parties, identities, and attitudinal dimensions associated with the universalism–particularism divide rather than the class cleavage (Hypothesis 5). Relatively weaker and less consistent moderating effects for field are in line with the literature’s extant focus on a graduate/non-graduate divide underpinning radical right versus new left opposition, and with evidence of weaker closure along the lines of field versus level.Footnote 17

Robustness Probes and Extensions

We now briefly summarize our supplementary analyses, while laying them out in detail in the Appendix. In Appendix C, we conduct a series of robustness tests and sensitivity analyses. Notably, we test the sensitivity of our results to different operationalizations of close ties, including parents and/or romantic partners in Appendix C.4. Including partners in the measure consistently strengthens network effects. Including parents strengthens network effects for immigration attitudes and universalist identities but generally weakens them for voting preferences. In the Appendix, we speculate on how countervailing mechanisms of socialization versus social mobility might partly explain this, as might the fact that similar values/identities could translate differently into vote choice for various generations politicized in rapidly transforming party systems. Taken together, these analyses offer robust evidence of networks’ moderating role in educational divides, while also offering new insights on similarities and differences in the influence of different kinds of close ties across political outcome variables.

Our appendices also explore extensions to our analyses. Appendix D compares the moderating effect of educational networks on vote propensity for the center-right, finding that network effects are absent (level) or weaker (field) than for parties associated with the universalism–particularism divide. The effects that we do find are consistent with accounts of electoral competition in realigned party systems, whereby the center-right is anchored particularly in (low-CECT) technical/managerial professions (see, for example, Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). Appendix E demonstrates that the moderating role of networks is present across the countries in our study, which vary both in terms of educational institutions and the extent of party system transformation.

Beyond propensities to vote, we consider vote choice in the prior election in Appendix F. For Germany and Switzerland, we again find clearer evidence for network effects by level than field. The UK’s predominantly two-party system poses an analytical challenge given small samples of voters for minor parties. We take two avenues to address this. We analyze the relationship of network composition to pooled vote choices for the Greens or Liberal Democrats as expressions of universalism. Next, we analyze the relationship of network composition to Brexit identities as expressions of a new cleavage in the UK (see, for example, Hobolt et al. Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021). Consistent with our main findings, network homogeneity in terms of education level, especially, is associated with sharp divides in political preferences.

Lastly, in Appendix G we test whether network effects are strengthened when restricting our analyses to respondents in relatively active discussion networks (those who reported discussing social/political issues with close ties). For voting propensity and immigration attitudes, we see sharper educational divides in higher-discussion networks. This is not the case for identity, suggesting that network dynamics may operate through explicit political communication or in a more diffuse consolidation of worldviews and outlooks.

Discussion

Taking cleavage perspectives on contemporary educational divides seriously, we investigated how the relationship between individuals’ own education and their voting preferences, attitudes, and identities are conditioned by educationally homogeneous or heterogeneous social networks. In doing so, we seek to address the puzzle of how twenty-first-century cleavage structures are stabilized. In the absence of the highly formalized member-organizations that characterized twentieth-century cleavage politics, we turned our attention to less formalized social ties. We theorized educational networks as consolidating predispositions formed earlier in life, and as emerging from occupational trajectories determined partly by educational choices – thus contributing to stabilizing cleavage structures.

Using a name generator question in an original survey, we asked respondents to provide information on their closest friends/acquaintances. This survey allows us to study the moderating effects of close social ties in Germany, Switzerland, and Britain, countries that vary in terms of their educational systems and regarding the consolidation of a new cleavage at the political level.

We find that while educational differences in terms of voting, attitudes, and identities tend to be insignificant among individuals with heterogeneous networks, differences are wider in homogeneous networks. For example, graduates in homogeneously highly educated networks are particularly likely to hold a universalist identity, adopt pro-immigration attitudes, and support the new left. Such patterns are most pronounced when looking at networks through a lens of educational attainment. A similar set of relationships is also evident yet less pronounced when considering network composition in terms of educational field. While divides among graduates (including in terms of educational field and related networks) could conceivably deepen and become more politically relevant with further educational expansion and generational replacement, our results hence generally support the importance attributed to graduate–non-graduate divides in most literature on the new cleavage. Further, as we would expect, educational networks are overall less clearly associated with traditional class conflict than with newer socio-cultural conflicts. This indicates that educational networks play a particular role in consolidating a newer universalism–particularism cleavage.

The broad similarity of our findings across countries at different stages of electoral realignment and with different educational systems indicates the pervasive nature of these social closure mechanisms. Social sorting by education shapes individual outcomes and social relations (’situational’ and ‘positional’ inequality, in the terminology of social network research; Christakis and Fowler Reference Christakis and Fowler2009: 31, 301–2) across advanced postindustrial knowledge societies, albeit in different ways. We can think of the German and Swiss education systems having direct stratifying effects through early tracking that increases the importance of parental background (Bol and van de Werfhorst Reference Bol and van de Werfhorst2013; Garritzmann and Wehl Reference Garritmann and Wehl2024). Meanwhile, the UK’s liberal economy stratifies and segregates more indirectly through interlocking market logics in schools and housing (see, for example, Gingrich and Ansell Reference Gingrich and Ansell2014).

This study suggests that such policies – by shaping social fabric at a structural level (also see Mijs Reference Mijs2023, 2, 10–11; and Jackson Reference Jackson2021, 19–30) – are not only consequential for the inequalities underpinning a new cleavage, but also for whether this cleavage finds particularly polarized political expression. Where individuals hold more cross-cutting social ties, identity antagonisms will likely remain more moderate, social compromise more possible, and the long-term pacification of a new cleavage more probable. An ‘old-fashioned’ perspective on the physical milieu segregation has not lost any of its importance in an age of transforming cleavage configurations. Yet, it is important to note that informal networks may provide only incomplete substitutes for the incorporating organizations associated with older cleavages: while radical right and new left parties have succeeded in articulating a new conflict without strong member-based partner organizations, it remains to be seen whether they can also eventually broker long-term pacifying compromise across cleavage lines without the channels provided by such allied organizations.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712342510080X.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/B7XTST.

Acknowledgements

The research described in this article was approved by the University of Zurich Ethics Committee for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (Approval No. 22.9.1). We thank participants at the Comparative Politics and Political Economy Seminar at the University of Konstanz, participants at the Cleavage Formation in the 21 st Century at the University of Zurich, participants at the 2023 European Political Science Association meetings in Glasgow, participants at the Cleavage Politics in Western Democracies workshop at the 2024 ECPR joint sessions at Leuphana University, Simone Cremaschi, Anna Kurella, Gary Marks, Liesbet Hooghe, and Marco Steenbergen, as well as editor Ruth Dassonneville and three anonymous reviewers at the British Journal of Political Science for their detailed and constructive feedback.

Financial support

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the URPP Equality of Opportunity Program, University of Zurich, from the ERC-grant TRANSNATIONAL (Nr. 885026), and from the Cluster of Excellence ‘The Politics of Inequality’, University of Konstanz.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.