Winner of the Roman Society PGCE Research Prize 2017 (King's College London)

‘We should read as the Romans did: in the Roman author's word order. To skip around in a sentence only makes it harder to read the Latin’ (McCaffrey, Reference McCaffrey2009, p.65)

For countless students of Latin (myself included), prevailing memories of Latin instruction involve being taught to unpick Latin sentences by racing towards the verb and securing the meaning of the main clause before piecing together the rest. However, this ‘hunt the verb’ approach, where one's eyes are jumping back and forth in search of the resolution of ambiguity, is not necessarily conducive to fluent reading of Latin (Hoyos, 1993). If, as so many textbooks and teachers vouch, we are aiming to unlock Roman authors for all students to read, then we need to furnish them with the skills to be able to read Latin fluently, automatically and with enjoyment, not engender in them a process more akin to puzzle-breaking. I chose to experiment with teaching students to read Latin in order, firstly because, as Markus and Ross (Reference Markus and Ross2004) point out, the Romans themselves must necessarily have been able to understand Latin in the order in which it was composed as so much of their sharing of literature happened orally. Indeed, as Kuhner (Reference Kuhner2016) and others who promote the continuation of spoken Latin have argued, this is still a very real possibility today. And secondly, because it is a skill which I, and others, believe to be teachable (Hansen, Reference Hansen1999; Markus & Ross, Reference Markus and Ross2004; Hoyos, Reference Hoyos2006; McCaffrey, Reference McCaffrey2009). Not only that, but whatever our starting point, Wegenhart (Reference Wegenhart2015) believes that by encouraging these reading skills early, we can encourage our students to be ‘expert’ readers who will be able to enjoy reading Latin long after they have been through their exams.

Literature Review

In order to inform the planning of my lessons I looked into what happens during the reading process itself before uncovering how and why this research can be used to inform the teaching of Latin reading. I then explored why teachers have veered students away from the process of linear, left-right reading towards a more disjointed approach, before explaining the benefits of reading Latin in order and practical ways of teaching this process in the classroom. The inspiration for this sequence of lessons arose from McCaffrey's chapter in the US book When Dead Tongues Speak (Gruber-Miller, 2006, pp. 113–133). Further literature for this review was located by following leads from this starting point supplemented by an internet search engine. Although much of the most influential research stems from countries other than the UK (Dexter Hoyos in New Zealand and Richard Hamilton in the United States), I found that this had no difference in impact on the British classroom experience. Most of the research cited has been conducted between the early 1990s and the present and is still very applicable today. Some of the research is rooted in modern languages teaching; however, this makes no significant impact on findings as the expectations of what students are to extrapolate from these target language texts are very similar.

What do we do when we read?

Reading is a complex process and one which we find difficult to explain once it has become intuitive. The differences between skilled readers and novices can seem stark, although exactly what predicates these differences is difficult to outline. Hamilton (Reference Hamilton1991), using cognitive reading research, breaks down the process of reading into sub-tasks. He identifies the stages of decoding, literal comprehension, inferential comprehension, and comprehension as the necessary steps towards reading for understanding. He explains how students can vary in attainment at these different stages and furthermore, the same student can fluctuate between different levels of attainment from day to day and from task to task. He argues that, though many of the circumstances surrounding the reading environment are beyond the control of the teacher, he or she is still able to manipulate certain factors (such as the purpose of reading) to facilitate the best comprehension from students.

Wegenhart (Reference Wegenhart2015), in a different approach to Hamilton, uses research based on learning to read English to inform the teaching of Latin and Greek. He advocates the Reading Rope and Cognitive Reading maps to help teachers identify at which point students are being held back in their reading comprehension and adapting their teaching accordingly. He argues that the basis of phonic recognition and manipulation must be present before the recognition and recall of words and sentences can be expected. This in itself is a reason to further promote speaking Latin out loud as discussed further below. By working back to the very basics and mechanics of reading, and not assuming that our Latin classes are in fact full of fluent readers of English, he argues that teachers are able to situate their instruction more appropriately to the needs of their students and provide them with the tools to become expert readers.

McCaffrey (Reference McCaffrey and Gruber-Miller2006) bases his analysis of different reading approaches (skimming, scanning, extensive reading and analytical reading) on the word-by-word decision-making process of reading as identified by von Berkum et al. (1999). He explains how students need to be able to construct meaning as the sentence evolves in order to read efficiently and in order to do this they need a strong grammatical grounding which is already well-developed in their native language.

In order to achieve this fluency, Wegenhart (Reference Wegenhart2015) makes explicit how important a large working vocabulary is to reading Latin. He identifies students' phonic awareness as an indicator of their ability to recall vocabulary. As a result, he advocates speaking words aloud (even as simple as using imperatives) as a means of vocabulary retention and recall. Hamilton (199, p.8) also cites phonemic awareness as critical to students understanding Latin, suggesting that students should hear Latin before they ever try to read it; Dixon (Reference Dixon1993) also suggests reading aloud as a means of helping students to read whole phrases at a time. Rea (Reference Rea2006) proposes reading Latin out loud as a means of embedding the connections between sounds and sight. It is for this reason that I have built into my planning a number of opportunities for myself and the students to read Latin aloud as a stage in the understanding process.

How has reading Latin been taught in the past?

Morgan (Reference Morgan1997) points to the fact that in the Middle Ages people learnt Latin not by drills, but by reading, starting at the beginning of the Aeneid and learning each new word and construction as it came up. He acknowledges that, as a method of learning to read Latin, this still exists in books such as Øberg's lingua latina per se illustrata, but recognises that this approach demands highly motivated students who are already fluent readers in their own language. As a result of this, he is in favour of the ‘horizontal’ method of reading Latin where, as exemplified by the Cambridge Latin Course, cases are introduced one at a time so that, for example, students are confident using the nominative and accusative before the genitive is introduced. This is in direct contrast to the ‘vertical’ method where students are exposed to all cases at once and, after learning them without context, will later be introduced the significance of each.

The form of ‘hunting the verb’ reading which we are so familiar with, then, seems to be a more recent, Anglo-centric phenomenon, where our need for a subject-verb-object sentence structure overcomes our natural left-to-right reading habits. Hansen (Reference Hansen1999), McFadden (2008) and Hoyos (2009) recognise that this tendency in reading Latin is a result of our impatience to resolve ambiguities. We rush to conclude the main clause before adding in any subordinate information. McCaffrey (Reference McCaffrey2009) suggests that it may be borne also out of a realistic appreciation of the fact that the verb contains a great deal of information that can avoid erroneous, ungrammatical understandings of earlier information. Rea (Reference Rea2006) admits, however, that often this jigsaw approach to Latin can be engendered by the ever-dwindling timetable hours allocated to Latin, indicating that perhaps the pressure put on schools to get their students to a certain level in a short space of time has been influential in the promulgation of this method. I agree with their assertions and am interested to see whether reading Latin in order can in fact increase reading speed and confidence.

Why should we teach students to read in Latin word order?

The main reason that McCaffrey states for reading Latin in order is that reading it out of order is in fact harder than sticking to the original text (2009, p.62). He adds that skipping over the bulk of the sentence ignores the careful literary crafting of Latin prose and poetry, a thought echoed by Hansen (Reference Hansen1999, p.174). Hoyos goes further, saying that it can develop a view of the text as ‘a sea of chaotic harassments requiring careful decipherment’ (2006, p.24).

McCaffrey arrived at his statement through a systematic survey of popular set texts (Ovid, Virgil, Cicero and Tacitus) where he analysed how many words it took for an ambiguous Latin word (for example naves which could be either nominative or accusative plural) to be resolved by an adjective, verb or preposition. He found that over 65% of the time the trigger word was already present, so the ambiguity could be resolved immediately and, in over 80% of cases, the trigger word would follow on directly from the ambiguous one (2009, p.65). Even before the numerically analytical research of McCaffrey, Hoyos makes a case for Latin authors being considerate of the reader's position and putting information in chronological and logical arrangement (1993). This is a point which Markus and Ross emphasise, too, when they make clear that students need ‘important psychological reassurance’ that texts are not designed to surprise us at every turn (2004, p.86).

Furthermore, they argue that single-word recognition is one of the most overt indicators of reading ability (2004, p.85). Rea (Reference Rea2006, p.3) and Hoyos (Reference Hoyos2006, p.8) both highlight how, by reading in order, the grammatical information becomes not a hindrance (as it can sometimes appear to the intermediate Latin student), but a help to reading. Similarly, Hamilton notes that teaching Latin word order from the beginning of Latin instruction means that grammatical information is seen as a vital part of the comprehension process (1991, p.168). He adds that this is crucial in Latin as meaning is often withheld to the end of the sentence meaning more contextual clues are contained in the early parts of the sentence.

Markus and Ross (Reference Markus and Ross2004) state that a further reason for which we should advocate reading Latin words as they emerge in the sentence is that those with lower skill levels in low-level processing (such as decoding and phoneme recognition) are more likely to revert to relying on higher-level thinking (such as contextual and background knowledge) to understand texts. I would agree that, for students who have internalised fewer words and grammar points, often this hunt-the-verb phenomenon is a useful crutch as it enables them to identify the most basic structure of the sentence. They are then able to surmise more easily what may be encoded in the intervening words. This can often lead to ungrammatical translations which ignore syntactical structures. Of course, at times when the reader is struggling with a decontextualised piece of writing, this can be a useful process, but this does not mean that as teachers we should encourage it for every instance. Hamilton, however, disagrees, saying that in the crucial ‘integration’ stage of the comprehension process, students who are only granted the ‘patchy coverage’ of Roman civilisation during language lessons are not sufficiently equipped to unlock Roman texts efficiently (1991, p.171).

How should we teach reading in Latin word order?

As alluded to above, many scholars agree that reading in Latin word order necessitates being able to store information about possible meanings of ambiguous words in a sentence whilst waiting for clarifying ideas to emerge and weighing these alongside their predictions (Hansen, Reference Hansen1999; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1991). It is therefore this skill of juggling and then prioritising possible grammatical interpretations as they appear that the teacher ought to train his or her students to master. In order to do this, students must, as far as possible, be able to recognise automatically the various inflections of Latin words (Hansen, 1991; Frederickson, 1981; Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1991; McCaffrey, Reference McCaffrey and Gruber-Miller2006). There are a variety of strategies offered by research to begin cultivating this skill. I will deal with each in turn.

Latin Reading Rules

Hoyos (Reference Hoyos2006) and Markus and Ross (Reference Markus and Ross2004) advocate teaching students some of the basic principles of what to expect from reading Latin (see Appendix 1 and 2) and asking them to learn these by heart. Since I am not teaching the focus class from the beginning and only for a short period of time, I will not expect that they learn these or, indeed, be given them all at once. I will, however, emphasise some of the more basic ones (to do with noun / verb and noun/adjective agreement).

Pre-Reading and Annotation

McFadden (2008) and Markus and Ross (Reference Markus and Ross2004) both suggest that, instead of being asked to prepare texts by translating them before class, students are asked to annotate all grammatical features either on tablets or other non-permanent means so that they can be corrected in class. McFadden argues that, in this way, errors can be more easily learnt from once corrected. He also argues that this removes dependency on paralinguistic knowledge and other assumptions which students often rely upon to translate. Markus and Ross (Reference Markus and Ross2004) suggest using visual metaphors to inform these annotations and illustrate the structure of complex sentences. They suggest images such as beaded jewellery or buildings as effective similes for the component parts of a long sentence.

As aforementioned, Rea (Reference Rea2006) advocates pre-reading in diverse forms involving many different activities which engage students in active learning and encourage them to think about what they are going to be doing before they actually do it. She argues that by doing this, students are given a framework of the kinds of questions they should be asking themselves when approaching a text. Morgan (Reference Morgan1997), however, veers away from this suggestion, arguing that, if we would like students to approach and read passages in a manner as similar as possible to that which they adopt in reading English, then we should leave the Latin uncluttered and free from notes (which should at least be relegated to the other side of the page). I will incorporate some pre-reading strategies into my planning in an attempt to increase students' reading comprehension speed as I have noticed in previous lessons that their reading speed is such that they easily lose the gist of the passage.

Prediction Drills

Hansen (Reference Hansen1999) and Markus and Ross (Reference Markus and Ross2004) advocate prediction drills whereby the teacher, whilst slowly revealing consecutive words or phrases of the sentence, asks students for suggestions on what the grammar implies will be coming next. They suggest that the teacher encourages students to look backwards rather than skipping forwards for clarification. They promote these drills as useful for set texts, but, as the class I am teaching have not started these yet, I will perform similar exercises using the textbook stories.

Summarising for meaning

Markus and Ross (Reference Markus and Ross2004) and Rea (Reference Rea2006) both suggest asking students to summarise what they have read at regular intervals to ensure that, amidst the grammar, they have understood and are able to visualise what is happening. They highlight how crucial it is that students are aware of the ramifications of texts in a historical context, a process which is best facilitated through class discussion. Hansen goes further, and, in an effort to veer away from translating to thorough comprehension, recommends asking students to summarise what they have read in a way which would be clear to someone who has no knowledge of Latin or the Romans at all (2000, p.78). Hamilton, too, suggests stepping back from the text and summarising as a means of monitoring comprehension (1991). As this is something I do already, I will continue to focus on this in my lesson sequence.

Prose composition and grammar manipulation drills

Hoyos (Reference Hoyos2006) advises setting students work which involves the manipulation of grammar (for example from direct to indirect speech and vice versa). He also advocates grammatical annotation of passages, though, unlike McFadden (2009) and Rea (Reference Rea2006), thinks this should best be done with easier passages. He and Morgan (Reference Morgan1997) suggest asking questions in Latin which are to be responded to in Latin (for example, quis Romam ibat?) as this automatically doubles the amount of Latin language which students encounter in the classroom and encourages them to think carefully about their own written Latin word order. Markus and Ross (Reference Markus and Ross2004) also suggest converting complex sentences into simple ones, explaining Latin using Latin synonyms and converting poetic language to prose. With the new GCSE specification demanding either syntactical questions or simple English-to-Latin sentences, these exercises which demand the production of Latin look to be increasingly helpful.

Vocalising of reading process

Markus and Ross (Reference Markus and Ross2004) suggest asking students to explain out loud how they are going about reading so as to make the teacher aware of their uncertainties and, as an additional benefit, to make it clear to students what strategies one can adopt to extract meaning more efficiently from the text. I will use this as a focus question in one lesson and monitor how the students themselves verbalise their reading process across the sequence.

Conclusion of the Literature Review

The available literature offers a great breadth of reasons why reading Latin in the order that it is written is more beneficial than leaping about to stick religiously to an Anglo-centric subject-verb-object word order. Reading as such, scholars argue, is both an easier and richer experience as it alerts students to the deliberate stylistic techniques Roman writers used. The authors also include several possible classroom techniques to engender this good practice in students, many of which I will adapt in my planning. However, what the research currently lacks is an assessment of how successful these practices are in encouraging students to read in order, and whether they will naturally revert to finding the verb. It also does not analyse whether or not stylistic features are in fact best appreciated when reading as opposed to being identified post-translation. My research questions, therefore, will be i) how useful are these techniques for an intermediate GCSE Latin class? and ii) does reading like a Roman improve students' awareness of grammar (and literary techniques)? I will assess their own confidence in reading by issuing an identical self-assessment questionnaire at the beginning and end of the sequence. During the various prediction exercises I will assess individual strengths by targeted questioning and circulating. As Black outlines, it is crucial to observe ‘the actions through which pupils develop and display the state of their understanding’ (2001, p.7) and so I will ask the observer to listen to how the students evaluate their learning and I will also ask them for written feedback on the process. During Parents' Evening I will provide a mixture of task-focused, process-focused and self-regulation feedback as I ask them to reflect on their learning (Hattie & Temperley, 2007). As a majority of the work undertaken in the sequence will be whole-class based, I will try to reduce the factors which limit students reaching for their own feedback (losing face, lack of effort, confusion) to maximise the opportunities they have to become more certain in their knowledge in an unthreatening environment (Hattie & Temperley, 2000). Finally, I will set a written homework to assess how their accuracy of grammatical perception matches up to their ability to translate.

Evaluation

Context

The four 60-minute lessons were taught to a Year 10 class in a mixed comprehensive school outside of London. Table 1 shows the sequence of four lessons. There are six boys and six girls in the class. The focus group was selected to provide a spectrum of self-professed confidence levels at the beginning of the sequence.

Table 1. | The lesson sequence.

Though most of this research is based on reading Latin authors in the original, I conducted my lessons on the initial stories of Book IV of the Cambridge Latin Course (CLC), revisiting stories from previous books when needed to encourage fluency and boost confidence. It is my view that the step up from Book III to Book IV is significant enough to merit it being seen as a microcosm for the step from textbook Latin to Roman authors themselves.

Lesson 1

Plan

The first lesson of this sequence was designed as an introduction to the main objectives of how to read Latin more like a Roman. I planned to begin by sowing seeds of positivity towards grammar as a help to understanding rather than a hindrance (Markus & Ross, Reference Markus and Ross2004). As part of a class discussion, as well as their own post-it notes on how they read, I planned to ask them how and why certain passages were easier to understand than others. I also planned prediction exercises in both English and Latin using Book 1 stories (Hansen, Reference Hansen1999; Markus & Ross, Reference Markus and Ross2004). After having chosen volunteers to read the Latin captions aloud and asking them to translate them in groups, I planned to ask them to describe the Roman forum as if to an alien as suggested in Wells (2000, p.178).

Evaluation

Students were able to generate interesting ideas regarding why exactly it was that they understood the Book 1 passage when I read it to them and it started them off on a positive note as they realised they were able to understand Latin orally. Students were concentrating hard, and everyone was able to get a general gist of the story. Three students (Phoebe, Ross and Rachel) from the focus group were particularly vocal and thoughtful when I asked them to think about how to predict English and Latin sentences – it appeared to be an activity which they had never done before but which encouraged them to think actively about the reading processes they engage in naturally. When Rachel and Joey from the focus group volunteered to read the captions out loud, it was interesting for me to hear how the stronger of the two (Rachel) was also the more fluent reader of Latin, whilst Joey was much more hesitant. Joey was also the student who came lowest in both the written assessments. This confirmed to me Wegenhart's theory about how phonemic confidence can often reveal a lot about students' comprehension abilities as, if they are unable to sound out words, they are less likely to be able to recall them when they reoccur (2015, p.8). Rachel and Phoebe, two of the higher-attaining part of the focus group were swift to recognise the –ur passive ending and begin to translate it accurately.

Lesson 2

Plan

This lesson was designed to crystallise embryonic thoughts about the passive and to introduce the idea of pre-reading strategies and annotations. After explanations of how the passive works in English and Latin, I then planned to ask students to generate questions they should be asking themselves before starting a new passage (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1991, p.172). Then, I planned to put these into practice by starting to look at a new passage and go through how to annotate a Latin passage for homework by drawing arches above phrases and subordinate clauses to encapsulate complex sentences and linking words that agree in gender, number and case (McFadden, 2008; Lindzey, 1999).

Evaluation

Students were quickly able to recognise the passive in English and how often the language needed to be manipulated to include a subject or a change from singular to plural or vice versa. Despite finding these sentences difficult, students were able to incorporate the cultural information on the forum Romanum that we had studied in a previous lesson to inform how they worked out the meaning of the captions, thus using contextual clues to comprehend unfamiliar language (Markus & Ross, Reference Markus and Ross2004:85).

Though having to work quite hard, students remained in high spirits and Monica, who rated herself lowest in the self-assessment, asked insightful questions about why they had not been introduced to the passive earlier, since it is so commonly used. The students were able to vocalise a whole spectrum of pre-reading questions on texts, and many realised that these were strategies they knew about but frequently omitted when faced with a new piece of Latin. I condensed these onto an A5 sheet for them to refer to in future (Figure 1).

Figure 1. | Pre-Reading Strategies. Information sheet for students.

Leading on from this discussion, I explained the annotation homework to them (McFadden, 2008). This would have been more effective had I been able to project the Latin onto the board and model it for all to see. As it was, I only had a few minutes to explain the task which left them reeling slightly. Overall, this lesson was a little disorganised but stimulating, and revealed a prevalent trend for students to implement contextual knowledge to deduce meaning which, though frequently helpful, when used as a last resort often led to linguistic oversights and inaccuracies (Markus & Ross, Reference Markus and Ross2004).

Lesson 3

Plan

The spine of this lesson centred around using the class annotations prepared in advance to read the text together without translating (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. | Sample of student's annotations of text.

As outlined by McFadden (2008, p.4), this gives students a chance to correct their thinking in a way which allows them to read it more fluently. It also, he argues, improves efficiency, as students are able to make just a few marks of correction, rather than re-writing whole sentences. As well as having the text up on the board to annotate, I also provided questions, below, which I planned to let students discuss in groups, as a means of monitoring comprehension as we went along. As Wegenhart argues, well-asked questions can also draw out student knowledge and encourage students to approach sentences in different ways and think more deeply about literary style (2015, p.12).

Evaluation

It was during this lesson that the greatest improvements in the students' reading could be seen. Monica, who had previously rated herself very low in confidence, was able to give a remarkably fluent translation of a tricky sentence. The class maintained motivation despite admitting to me that they had found it hard. Chandler volunteered to show us his annotations on the board first, showing that his confidence was increased in performing a task which was not simply straight translating. Giving the students time to think about the comprehension and stylistic questions in groups before asking for feedback from individuals meant that interesting ideas were generated and I could hear them all contributing to the discussion.

Unfortunately, due to a last minute change of classroom, I was unable to do the annotations on the interactive whiteboard and so the students had to demonstrate their markings using the editing features on PowerPoint as best they could. This significantly slowed things down, and meant that the annotations could not be as clear and smooth as planned. Despite this, when I circulated, I saw that everybody in the class was taking comprehensive notes during the lesson of new grammar features and vocabulary as well as correcting their annotations.

Lesson 4

Plan

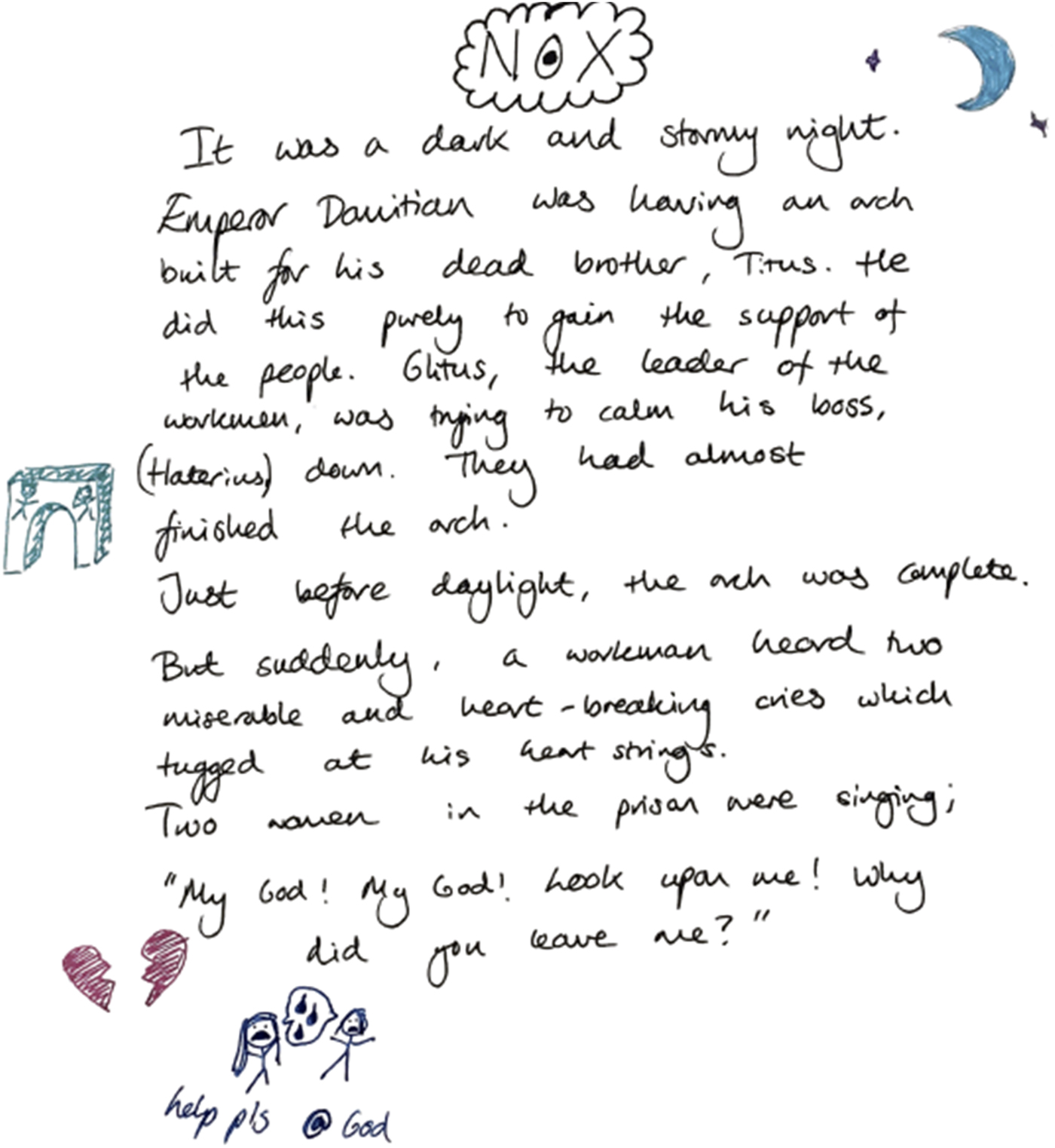

The final lesson in the sequence focused on summarising the passage they had just read together through visuals and their own words (Markus & Ross, Reference Markus and Ross2004) (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. | Sample of student's visualisation of the narrative.

Figure 4. | Sample of student's own version of the narrative.

My intention was that by using their pre-reading strategy sheets (generated collaboratively in a previous lesson) and their annotated texts, they would be able to stand back from the passage and comprehend the meaning through the grammar and the context (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1991; Rea, Reference Rea2006). In an effort to end the lesson on a fun note, I planned to play some games involving quickly recognising word endings and encouraging more automatic reactions, as recommended by Hamilton (Reference Hamilton1991).

Evaluation

From my point of view, when I asked students to explain what a sentence meant in English after we had annotated them as a class, it seemed as if their reading was a lot more accurate and sensible, rather than the frequent guessing I was accustomed to hearing from them. Even when the meaning of a sentence had not quite clicked with them, they were able to read from the annotations what the general structure should be and work from there. The observer also noted that Joey was asking astute questions about grammar which he may not have considered before, for example; ‘Do all command verbs take the dative?’

The summarising activity had to be fitted into less time than I had planned but the students coped with this admirably and it was very effective to continue the forward momentum of the lesson and consolidate their understanding to themselves and to me. I gave them instructions to summarise the story including any visuals they would use, as in a film. In a short space of time they came up with detailed storyboards of the passage (Figure 5).

Figure 5. | Sample of student's storyboard of the narrative.

I was impressed to hear Chandler and Ross reminding themselves of the meaning of certain Latin sentences so that they could include them, demonstrating their ability to read the Latin afresh without having memorised a translation (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1991).

The class voted to play BINGO of passive endings and, after going over the meanings of each of the verbs in turn before we started, they enjoyed a relaxed end to the lesson. By reading out the Latin for them, it is hoped that this helped them again to keep sounding out the Latin accurately in their heads to aid recall of vocabulary.

Student feedback on the sequence

I asked the students to write a WIN (What went well, Improvements, Next steps) on the sequence of lessons, saying what they had enjoyed, had not enjoyed, and anything in particular that they had learnt (Donka & Ross, 2004, p.87). Students were well accustomed to writing this sort of WIN feedback about their own personal performance and so a few wrote about their own knowledge rather than the sequence of lessons. However, despite this, their revelations seem quite raw and honest with many offering erudite diagnoses of their own stage in Latin learning.

The annotation lesson seems to have been a favourite of many, with one student, Phoebe, remarking:

I think I now know how to break apart sentences better and work out the subject and case … annotating nox II was helpful and proved everything I have to think about.

Monica said:

I also liked the Latin text we annotated which I found helpful to do in class because I struggled slightly at home with it.

Monica was the one who gave a surprisingly confident translation of a complex sentence in class once we had annotated it together. As one of the weaker students in the class, this showed me that for her, knowing how the Latin fits together and correcting this before being asked to translate it, means that she was able to gain much more from the passage than had I asked her to translate it cold (Lindzey, 1999; McFadden, 2008). The annotations helped the Latin make sense to her so that she could read it fluently. She also noted, however, that ‘I feel like some of the interactive stuff put me on the spot, which I very much struggle with. I understand that it is part of teaching but I was worried by the idea of annotating text at the front of the class’. This was intended to be a collaborative activity with one student wielding the pen and the others offering suggestions for annotations. However, in just two lessons (one in which the board wasn't working!), this did not get a chance to get into full flow. One would hope that the practice of being the class annotator would in future become more routine and everyday once they start studying their set texts. Rachel remarked that she ‘didn't enjoy the annotation work, it was complex’. This student is one who is a strong reader anyway, and so perhaps found the microscopic lens slowed her down. It is hoped, perhaps, that in this case, by slowing her down and securing the syntax and grammar of every word in a sentence, she will be better equipped to deal with more idiomatic Latin outside of the textbook. This student also noted that she thought she was ‘not particularly good at annotating passages – I didn't put enough detail in’ showing that perhaps her perceived lack of success in this task, compared to her usual swift understanding of Latin through context and logic, had knocked her confidence. To make it simpler, I could have specified more exactly what I wanted them to annotate rather than giving them guidelines only. She may have then felt she had more success in this process.

There were very promising comments from a number of students who seemed to have begun to think much more carefully about how they read the Latin. ‘I have a better approach to translating a passage, looking and finding clues’; ‘I have learnt how to approach a new passage and how to quickly spot agreements between words. I have learnt how to predict Latin sentences’; ‘I've gotten better [sic] at matching nouns and adjectives etc.’ and ‘I think I now know how to break apart sentences better and work out the subject and case’.

As their points for improvement, most students acknowledged their need to memorise more endings so that they are able to be confident in their knowledge and more automatic in recognising grammatical patterns as advocated by Hamilton (Reference Hamilton1991).

Some students referred to a Grammar A&E lesson which we had done prior to this particular sequence of lessons. Here they did a carousel activity on three different grammar points which I had chosen based on those which they revealed they felt least confident of in their self-assessment questionnaire. They were then allocated a grammar point in pairs on which to write a poster which I then combined into a booklet for them to revise from. A number of students requested that we do more of this kind of lesson as a means of them recapping and solidifying things they may not have internalised the first or second time round. Their desire to use class time to internalise basic language tables is something which will have to be balanced carefully in future.

Students' vocalisation of reading processes

At the beginning of the sequence, I asked students to write down how they read on a post-it and compared this with how they verbalised their reading process in Latin at the end of the sequence (Markus & Ross, Reference Markus and Ross2004, p.84). At the beginning they focused on reading left to right, concentrating on reading letters to make sounds which then form words. Many wrote about how they sound aloud the letters to form words. Chandler noted how often only the first and last letters are needed to recognise words in English (which may explain his fairly slap-dash, hurried approach to Latin!). Only four students took the step back to include how the sentence should make sense and how we need to look at how the words relate to each other. Interestingly, those who came near the bottom of the self-assessment in terms of confidence (Monica and Phoebe) had the most basic explanations of reading processes, and those who rated themselves as being more confident (Rachel and Ross) were able to vocalise more sophisticated approaches to reading before we began the sequence.

At the end of the sequence, everyone was able to give fairly detailed accounts of their Latin reading processes. Though some expressed how they try to ‘piece it together’ and ‘put it together’, showing perhaps some evidence of the jigsaw puzzle method, I was impressed to see that they had this as the last stage in a progression from looking at vocabulary and grammar, working out the subject and the adjective pairings before finally stringing it together. Monica, who seemed to struggle most at the start, said that she now tries to ‘scan the sentence for any vocab and endings I recognised, then try to fill in the gaps’ – pre-reading strategies have helped her greatly. Rachel, the most confident reader said that her approach to reading Latin is to ‘go with the flow’ – a wonderful description of reading the words as they come, showing how she is able to appreciate the language as it unfolds.

Evaluation of assessment data

There was no marked improvement overall in the students' own assessment of their confidence with certain linguistic features; however, there was a marked improvement in their appreciation of adjectives. This was an important step forwards as it shows that they are now able to use adjectival agreements to help with their reading. A number of factors impacted this result, namely that during the course of the lessons, in moving on to Book IV, we were introduced to a new linguistic feature, (the passive voice) and so did not spend the time wholly on consolidating old material. I view the students' seeming dip in confidence in their knowledge of certain linguistic features as symptomatic of the fact that, by reading complex texts, they were required to apply their knowledge of them in more varied and difficult contexts. It is hoped that this realisation about the different levels of language learning will stand them in good stead to secure their knowledge over the course of the GCSE. A second factor which influenced these self-assessment results was that I had since revealed to them their scores on the written assessment and discussed how this matched up to their self-assessment scores (Monica for example, rated herself very low on confidence but was situated near the middle of the class in the assessment scores and thus seemed buoyed in confidence).

The results of the two assessments showed a marked improvement in students' attainment, as can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2. | Year 10 Assessment Data comparing assessments 1 and 2.

At best, two students displayed an over 25 per cent improvement, with all students but one improving their score by at least five per cent. The greatest improvement in scores was across the grammar questions, showing that students had not only clarified certain grammar points, but that they were also more eagle-eyed when it came to knowing which words to associate. Inevitably, some of this improvement can be related to their knowing what to expect from the assessment, though there were very few instances where a student had remembered and researched specific instances of vocabulary in order to improve their response. The most significant changes in their approach was their looking for meaning from the passage, rather than simply trying to string disparate words together in the hope of gaining marks. All students wrote much more fluent translations the second time round, and had clearly been asking themselves some of the questions which we had been focusing on in lessons. Even in cases where the vocabulary was still a hindrance, students made the effort to write in full sentences with a logical progression, putting the grammar they did identify confidently into practice.

Conclusion

This was an early step in what will be a long march towards Latin fluency, but the outlook is promising. Even the simple notion of asking students to first vocalise their reading process proved to be a hugely influential one in their development as Latin readers, as it cast the spotlight on what had for many been a fairly random activity, quite detached from any of the finely honed reading skills which they employ when reading English. With a supportive reading framework in place, where the goal of the reading is made explicit and the context of the passage has been established with relative certainty, a student is much more likely to appreciate the meaning of what they are reading (Field, 1993; Rea, Reference Rea2006). Reading in this way also necessitates learning grammar by heart, rather than surviving through a scant knowledge of how main clauses fit together and piecing together the rest through inference. This was one of the starkest findings of the students' feedback on the sequence: that they were motivated to go away and learn the grammar that they had done so far (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1991).

Clearly this is not a magic formula for Latin fluency, but in this case, in this school, it seems to have been a highly productive means of reading Latin and one which will only increase in utility as they graduate to authentic Latin texts. It is also important to recognise that, as they progress, students may realise that they require fewer annotations and so, they will, hopefully, need to use them less and less. Reading in order shows up, however, in high relief, the need for a solid linguistic base from which to work. Hamilton's (Reference Hamilton1991) suggestions of isolated word-recognition and matching activities rather than long sentences to translate would provide an excellent starting base for this and I will continue to attempt these in my teaching.

I have been heartened by the very real progress which students seemed to make based on their short introduction to the strategies expounded from the literature. Like the process of reading itself, as long as teachers are able to continually keep their students' feet taking each word step by step in order and not leaping ahead over the bridge, the task of reading Latin will, it is hoped, become much more fluent and enjoyable.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Menu of Basic Expectations

A DIRECT OBJECT raises the expectation of an active verb and of a subject.

A VERB raises the expectation of a subject and possibly a direct object.

A SUBJECT raises the expectation of a verb and possibly a direct object.

A COORDINATING CONJUNCTION raises the expectation of a second syntactic equivalent.

A SUBORDINATING CONJUNCTION raises an expectation of a finite dependent clause in addition to the independent (main) clause.

An INFINITIVE raises an expectation of a verb that governs it.

An ADJECTIVE raises the expectation of a noun to modify in the same case, number, and gender.

A GENITIVE noun raises the expectation of another noun to modify.

A PREPOSITIONAL PHRASE or an ADVERB raises an expectation of a verb, adjective, or another adverb to modify.

A NOUN in the ABLATIVE or DATIVE raises an expectation of a verb, adjective, or rarely an adverb to modify or pattern with.

Markus, D., and Ross, D. (2004) Reading Proficiency in Latin through Expectations and Visualization. The Classical World 98.1, p.79.

Appendix 2

THE TEN BASIC READING RULES FOR LATIN. Hoyos, D. (2008)

RULE 1 A new sentence or passage should be read through completely, several times if necessary, so as to see all its words in context.

RULE 2 As you read, register mentally the ending of every word so as to recognise how the words in the sentence relate to one another.

RULE 3 Recognise the way in which the sentence is structured: its Main Clause(s), subordinate clauses and phrases. Read them in sequence to achieve this recognition and re-read the sentence as often as necessary, without translating it.

RULE 4 Now look up unfamiliar words in the dictionary; and once you know what all the words can mean, re-read the Latin to improve your grasp of the context and so clarify what the words in this sentence do mean.

RULE 5 If translating, translate only when you have seen exactly how the sentence works and what it means. Do not translate in order to find out what the sentence means. Understand first, *then* translate.

RULE 6 a. Once a subordinate clause or phrase is begun, it must be completed syntactically before the rest of the sentence can proceed.

b. When one subordinate construction embraces another, the embraced one must be completed before the embracing one can proceed.

c. A Main Clause must be completed before another Main Clause can start.

RULE 7 Normally the words most emphasised by the author are placed at the beginning and end, and all the words in between contribute to the overall sense, including those forming an embraced or dependent word-group.

RULE 8 The words within two or more word-groups are never mixed up together.

RULE 9 All the actions in a narrative sentence are narrated in the order in which they occurred.

RULE 10 Analytical sentences are written with phrases and clauses in the order that is most logical to the author. The sequence of thought is signposted by the placing of word-groups and key words.

RULE 11 (advisory) Practise reading Latin regularly, and as often as possible, applying the Reading Rules throughout. [A Roman baker's decem, obviously!]

Hoyos, D., (2008) “The Ten Basic Rules for Reading Latin.” Latinteach Articles. N.p., 15 Oct. 2008.

Appendix 3

GUIDELINES FOR TRANSLATING Hoyos, D. (2008).

1 The Romans Didn't Know English (this rule is pronounced TRiDiKEe). Since they didn't know English, Latin is not ‘hidden English’ in form or vocabulary or grammar. Don't treat Latin sentences as though they are in the same word order and layout as English. If they are now and then, it's entirely accidental. See Point 2.

2

a Don't try to find an English meaning for each separate Latin word, to see if accumulating the separate words in English gives the meaning of the sentence. This method thinks of a Latin sentence as actually Hidden English, and yet TRiDiKEe.

b Don't believe that a Latin sentence is simply equivalent to English words in a mixed-up order, either. TRiDiKEe.

3

a Phrases, subordinate clauses, and main clauses are all WordGroups. This is a really important concept. Word-Groups are as crucial in a sentence as the individual words. No, they are more crucial.

b The arrangement of word-groups in a sentence is crucial to the meaning.

c The order of words within a Latin word-group obeys logical patterns. Always.

d The order of word-groups in a sentence also obeys logical patterns. Always. e You can *train your eyes* to recognise all these patterns, which are fundamental to the meaning of the sentence. This is how Romans sight-read Latin. (It is also how we sight-read English.) f Read and re-read each sentence so as to understand its structure and its constructions, before you start to translate it.

4

a Each word in a sentence tells you about the grammar and sense of the words around it. Therefore each word is a *signpost* to other words.

b The endings of the words are as important as the beginnings. The endings tell you the grammar of the sentence, i.e. how the words are related to one another. Motto: ‘T h e E n d i n g s C o m e F i r s t.’

5 How to recognise a subordinate clause word-group: - It has to start with a conjunction like cum, ut, postquam or the like, or with a relative word like qui. - It must contain at least 1 finite verb, i.e. a verb with a subject. (Sometimes the subject is implied, not given as a separate word—e.g. libros lego.) - It cannot form a sentence by itself, but is subordinate to a main clause. Sometimes the main clause is implied but not given: e.g. cur fles?—quia capitis dolorem habeo. (= [fleo] quia c.d.h.) - It obeys Point 7 a-d, like all word-groups.

6 How to recognise a phrase:

a A phrase is a word-group that does not have a finite verb. A phrase

[i] may be governed by a preposition, e.g. ex urbe, ab urbe condita, propter gaudium, in Britanniam, ad urbem videndam, multa cum laude

[ii] may consist of words describing a person, thing or event mentioned nearby, e.g. urbem ingressus, librum legentes, capillis longissimis, multis annis, maximae pulchritudinis (attached to puella, for example)

[iii] may be an Ablative Absolute phrase, a gerundival phrase of purpose, or the like. e.g. Cicerone consule, senatu vocato, ad urbem pulcherrimam aedificandam, pacis petendae causa.

b You can easily recognise a phrase if it starts with a preposition, but to recognise other phrases you must practise Point 3 a—f.

7

a A word-group of any kind (main clause, subordinate clause, or phrase), once it has begun, has to be grammatically finished, before the writer can continue with the rest of the sentence whether this is short or long. [This statement is an example in English] For the same reason, a sentence must be grammatically completed before the next one can start.

b The only exception to 7a is that one word-group can ‘embrace’ another one. e.g. Cicero, qui olim consul erat, nunc in senatum raro venit. But 7a still applies: the embraced word-group must be grammatically completed, before the writer can go back to the ‘embracing’ wordgroup. c Note carefully that 7a & 7b are unbreakable rules in Latin, for 7b is not really an exception to 7a: the content of an ‘embraced’ word-group is part of the Message of the embracing word-group. On Message, see Point 9. d A Latin phrase can ‘embrace’ a subordinate clause, and a subordinate clause can ‘embrace’ a phrase. e.g. urbe quae magna erat condita, and ut Romam multis post annis iterum videret. e If one main clause embraces a second, the second one has to be in brackets or between long dashes.

8

a In narrative Latin sentences, all the events are reported in the proper event order, even when the various events are stated in various types of word-groups.

b In descriptive (non-narrative) Latin sentences, the various word groups are written in the order that seems most logical to the author.

9 In Latin, every sentence carries a Message. The Message is not always given by just the grammar and vocabulary of the sentence: it also depends on the context around the sentence, the choice of words in the sentence and the placing of them. The Message is as important as the grammar and vocabulary.

Hoyos, D., (2008) The Ten Basic Rules for Reading Latin. Latinteach Articles. N.p., 15 Oct. 2008.

Appendix 4

End of term Year 10 assessment test.