I took pieces of the Negro’s skin from several parts, his buttocks, his arm, and foot sole &c. and let them soak in cold water for a week.Footnote 1

In February 1744, the Swedish physician Abraham Bäck (1713–95), often remembered as Carl Linnaeus’s best friend, dissected the cadaver of an unidentified sub-Saharan African man who had died at the Hôpital de la Charité in Paris.Footnote 2 Cadavers of sub-Saharan Africans were sought after by European anatomists because of their relative scarcity on the dissection boards of eighteenth-century Europe.Footnote 3 This was not due to a lack of African presence on the continent: recent scholarship estimates that there were more than 2.5 million enslaved Africans living across Europe between 1500 and 1800, with high concentrations in the Iberian peninsula.Footnote 4 In the last quarter of the eighteenth century, between 4,000 and 5,000 Afro-descendants – not all of them enslaved – were estimated to be living in France, mostly in the Paris area; in England, their number was even higher and estimated around 15,000.Footnote 5 However, like native Europeans, most Afro-descendants were baptized Christians and lived within households or small communities who safeguarded their remains from dissection.Footnote 6 As a result, African cadavers remained rare in the anatomical theatres of cities like Paris and London, despite the relatively common presence of Africans in these cities.

African cadavers were even rarer in northern European countries which neither had colonial possessions nor directly partook in the slave trade, as was the case for the kingdom of Sweden between 1663 and 1784.Footnote 7 Bäck’s first known encounter with an African body thus occurred abroad, on a Parisian dissection board.Footnote 8 Most eighteenth-century physicians travelled across Europe to train in anatomy and dissection in the Netherlands, England, the Venetian Republic, or France, with Paris being especially popular during this period for its hands-on approach. Bäck was no exception and spent four years travelling for his studies (1741–5), with residencies in Leiden, London, and Paris, after which he returned to Sweden and pursued a brilliant career as a medical reformer, anatomy professor, royal court physician, and president of his country’s foremost medical institution, the Collegium Medicum.Footnote 9

Although Bäck’s experiments on the remains of an African man have received little attention from his biographersFootnote 10 – possibly due to their controversial nature – they reflect his interest in one of the most popular topics of the era during a formative time in his career. Despite the limited posterity of his work outside Sweden, his transnational networks and training also shed light on a wider, neglected dimension of eighteenth-century racial medicine: the impact of first-hand dissections of rare African cadavers on the making of medical authority by European physicians.Footnote 11 The scarcity of dark-skinned African cadavers for dissections turned them into valuable medical commodities for European doctors. Scarcity offers a fresh lens through which to understand some of the material factors at play behind the early rise of racial anatomy. Empirical anatomists in the period were often propelled by chance encounters with ‘remarkable’ cadavers: that is, bodies that were considered exceptional due to their rarity or physical traits. Scarce cadavers of dark-skinned Africans were no exception and allowed European anatomists to tackle increasingly popular issues of heredity, differences, and race, which in turn could help them gain status within their respective medical and scientific circles. As Hannah Murphy has shown, social dynamics of career advancement acted as powerful motivators for conducting medical research on skin colour in the early European Enlightenment.Footnote 12

This is not to deny that the motivations behind such dissections varied considerably. Anatomists were drawn to the topics of human variation, race, and skin colour for a number of reasons beyond careerism, including, but not limited to, scholarly curiosity, religious commitments, and prejudice. Still, these remain insufficient to explain why individuals like Bäck studied the physiology of skin colour in the first place. As we will see, Bäck shared a genuine curiosity for the topic of human differences with several close collaborators, including his friend Linnaeus. Bäck’s research on ‘Ethiopian’ skin, based on exoticized bodies unavailable in Sweden at the time, helped him cement his medical authority at home, during a period when international medical credentials represented a valuable form of professional capital. While no direct causal link can be ascertained between his experiments on skin and his rapid professional advancement, it is enough to point out that his work on race was published in the prestigious Transactions of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences in the spring of 1748, an annus mirabilis during which Bäck was appointed chief physician of Stockholm and junior physician to the Swedish royal court.Footnote 13 More broadly, this article explores how the scarcity of African cadavers shaped the social production of medical knowledge on skin colour during the early European Enlightenment. I argue that, in this period, racialized anatomy ought to be understood not only in terms of ideology or science but also through the dual lens of professional ambition and resource scarcity.

The exploitation of African cadavers in early modern medicine has, of course, a longer history. Scientific racism has long been traced to a crucial turn in the middle of the eighteenth century, with Craig Koslofsky and Nicholas Hudson characterizing the period in terms of how the conjectures of Linnaean science on humoral imbalance and taxonomy supplanted earlier notions of skin colour.Footnote 14 Building on the works of Colin Kidd, Roxann Wheeler, Nancy Leys Stepan, and Hanna Augstein, Sadiah Qureshi has distinguished the rise of ‘anti-climatic racial thinking’ from a more pro-‘environmentalist’ medical literature which emerged from colonial settings.Footnote 15 Carlos López Beltrán further noted how adherence to ‘solidist’ models of the body in eighteenth-century France paradoxically ‘left open the door for a humoralist revival’, which ultimately ushered in a more racist biological turn in the second half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 16

Most of the scholars listed above have also noted how socially constructed contemporary notions of ‘blackness’ (including its recent capitalizations) were discussed in equivocal terms by historical actors in the period. In this article, I rely on early modern categories as much as possible, without trying to retrospectively harmonize their frequent ambiguity.Footnote 17 The presence of African cadavers on the dissection boards of the Atlantic world has more broadly been analysed in scholarship on the early modern market valuation of human remains and enslaved corpses.Footnote 18 The use of human remains (corpses, skin, skulls, and bones) from African individuals has long been identified as a central aspect of nineteenth-century scientific racism and racial science.Footnote 19 Such dissections gradually increased with the intensification of the slave trade, especially in the early United States, where cadavers of Afro-descendant individuals became commonly used for the anatomical training of medical students through exhumations from segregated slave cemeteries.Footnote 20 In this context, Rana Hogarth has highlighted how the bodies of dark-skinned individuals became ‘unwilling repositories’ for doctors to ‘generate new kinds of professional knowledge’.Footnote 21

This article focuses on the relatively overlooked European side of this phenomenon. As debates on the causes of ‘Ethiopian’ skin colour gained traction in Europe in the first half of the eighteenth century, empirical anatomists started to compete with traditional accounts from travellers, explorers, and naturalists. They did so by leveraging their access to African cadavers as an advantageous epistemic position within the wider competitive knowledge-building culture of the Enlightenment. As we will see in the first section of the article, this led anatomists to co-produce socially constructed notions of ‘black skin’, which tended to reject climatic adaptation in favour of innate differences that their empirical skills supposedly uncovered. The few European anatomists who accessed human remains of African origin tended to favour opportunistic explanations which best showcased their observational skills, and made sensationalist claims which, because of scarcity, often went unchallenged.

The second section explores how dissections of ‘Ethiopian’ cadavers were conducted unsystematically from one corpse to the next. Experiments were often carried out on small samples of skin rather than on entire cadavers, due to the corpses’ infrequent availability, market value, and short dissection window.Footnote 22 These issues, pertaining to the conditions of production of early modern anatomical knowledge, were not specific to cadavers of African origin: they applied to all bodies that ended up on dissection boards. As we will see, poor and marginalized individuals, including enslaved people, were to various degrees all vulnerable to such exploitative body trafficking, both during their life and in death. As shown in the third section, a recurring feature of dissections of ‘Ethiopian’ cadavers such as Bäck’s was the frequent racialization of putrefaction artefacts, exemplified by Malpighi’s enduring myth of an elusive ‘black’ membrane, based on a dark viscous fluid generated by inner dermal decomposition.Footnote 23 Other elusive differences included claims of excessive bile or phlegm, mysterious dark cerebral fluids, and fanciful accounts of bodily degeneration. The true cause of skin colour resisted consensus up until the late nineteenth century, when melanin became observable at the cellular level.Footnote 24

Curran, Malcolmson, and Koslofsky have all noted how the study of skin colour seemed to predispose doctors to assert ‘profound difference’, as if to support the heretical doctrine of polygenesis.Footnote 25 However, polygenesis remained both marginal and unacceptable for most Christians, and Andrew Curran and Justin H. Smith have both shown how it remained a fringe view in eighteenth-century European medical circles.Footnote 26 In line with these assessments, Bäck’s empiricist research on skin colour in the 1740s positioned him as an early overlooked Linnaean monogenist, connecting the earlier research of seventeenth-century microscopists of skin with the late eighteenth-century anthropological racism of physicians like Blumenbach. More broadly, Bäck’s experiments help us see that the tendency to assert profound difference based on equivocal empirical evidence cannot be reduced to racial prejudice, nor solely explained by an ontology of scientific observation, but rather by also factoring in the social and market dynamics which structured the growing anatomical culture of the period.Footnote 27

I

In October 1743 Abraham Bäck arrived in Paris, where he stayed for a year to collect botanical specimens and train himself in anatomy.Footnote 28 At thirty-one years old, it was his first stay in the French metropolis, a city in which he ended up enjoying himself ‘immensely’.Footnote 29 In Paris, he served as an early propagator of Linnaeanism towards French scholars such as the naturalist René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur and the botanist Bernard de Jussieu.Footnote 30 With the support of Linnaeus and his anatomical credentials garnered in Leiden, London, and Paris, Bäck would eventually become one of the most prominent medical scholars of his home country.Footnote 31 Yet, while most of his exchanges in Paris were concerned with botany, publications, and the polyp controversy, the young Swede had started to develop a side interest in one of the most heated debates of the eighteenth century: the origin and causes of the darker skin colour of ‘Africans’.Footnote 32

As Colin Kidd has shown, although the questions of race and skin colour were overwhelmingly discussed as theological problems from the seventeenth century to the nineteenth, the eighteenth century saw a strong movement to explain such issues in naturalistic terms.Footnote 33 The 1740s in particular were a decade of heightened scholarly interest, exemplified by a famous prize contest run by the Académie de Bordeaux in France in 1740, calling for proposals to elucidate ‘the physical cause of the colour of negroes, the quality of their hair, and the degeneration of the first or the other’.Footnote 34 Despite sixteen anonymous submissions from all over Europe, the contest was deemed inconclusive and closed without a winner.Footnote 35 From the late seventeenth century onwards, many anatomists, philosophers, and theologians challenged the classical, ‘soft-hereditarian’ consensus that inherited variations in skin colour, hair, and other characteristics were caused by a gradual adaptation to environmental conditions.Footnote 36 Such challenges took place within broader debates which contrasted traditional biblical monogenetic narratives of humankind with polygenesis, a heretical doctrine which postulated that certain human populations did not descend from the primordial Adamic couple.Footnote 37 While we may categorize such conjectures as being concerned with ‘race’ for purposes of historical contextualization, it is worth noting that the concept of race was not yet solidified at the time, and that, just like Linnaeus, Bäck did not use the term ‘race’ in his writings.Footnote 38

This article is concerned with the social emergence of an empirical medical culture within these wider debates. In the realm of natural science and medicine, discussions on the causes and nature of ‘black’ skin colour led to the emergence of new forms of medical authority, in which the highest form of expertise rested on rare first-hand dissections of dark-skinned cadavers. In contrast to the travelogues of lay explorers such as Nils Matsson Kiöping (1630–67), who discussed skin colour and albinism without speculating on their physiological causes, French travelling doctors such as François Bernier (1620–88) often ventured into the anatomical side of the debate.Footnote 39 Bernier, who had met many sub-Saharan Africans during his travels across the globe, had loosely chosen to classify Africans as ‘one of four or five’ different human races or espèces in a popular essay, Nouvelle division de la terre (1684, republished in 1722).Footnote 40 However, he still limited his conjectures to easily observable bodily fluids and characteristics as he never dissected cadavers of Africans. Their distinct skin colour, Bernier wrote, stemmed from ‘the particular contexture of their body, their semen, or their blood’, although he noted that their blood and semen was paradoxically ‘of the same colour as anywhere else’ (‘de la mesme couleur que partout ailleurs’).Footnote 41

Kiöping’s and Bernier’s limited testimonies reflect a widening gap between traditional early modern travel accounts and a new literature produced by a small group of European physicians who dissected such cadavers. In the 1740s, the French physician Pierre Barrère (1690–1755), a former botanist and royal physician in Cayenne, was one of the few anatomists who had dissected cadavers of Afro-descending people, dating back to his years spent in French Guiana. Barrère had submitted the results of his experiments to the inconclusive Bordeaux contest. The only known participant with empirical medical experience on the subject, Barrère also became the sole scholar to publish his contest essay. In his Dissertation sur la cause physique de la couleur des nègres (Paris, 1741), he highlighted his authoritative empirical experience, which had led ‘illustrious Academicians and other persons of recognized capacity’ to judge his results ‘still worthy of being printed’.Footnote 42 As noted by Andrew Curran, Barrère sought to approach ‘la couleur des nègres’ as a physiological whole rather than as the superficial product of environmental influence located at skin level. He presented his numerous empirical dissections as a strength, and he was part of a wider movement of medical empiricists who sought to gain scholarly recognition from their experiments on skin colour.Footnote 43

Such a group seems to have included only a handful of empiricist scholars over a period of two hundred years. Before Barrère, the early French physician Jean Riolan the younger (1577–1657) and the Dane Thomas Bartholin (1616–80) both focused on producing fresh accounts of the structure of ‘Ethiopian’ skin. As we will see when examining the scholars cited by Bäck more closely, the next generations of empirical anatomists saw the English physician Thomas Browne (1602–82), the Italian Marcello Malphigi (1628–94), and the German Dutch anatomist Johann Nicolas Pechlin (1646–1706) produce more nuanced assessments of ‘Ethiopian’ skin structure. Their research was amplified – and occasionally challenged – by the Dutch anatomist Govard Bidloo (1649–1713), the microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), and three French anatomists: Alexis Littré (1654–1725), Jacques-François-Marie Duverney (1661–1748), and Claude-Nicolas Le Cat (1700–68), who were closely followed by the German-born Dutch anatomist Bernhard Siegfried Albinus (1697–1770) and the German anatomist Johann Friedrich Meckel the elder (1724–74).Footnote 44

Most of these scholars focused on the structure of the skin, while Le Cat and Meckel wrote extensively about supposed differences in the cerebral anatomy of ‘Ethiopians’: Le Cat, for instance, claimed that the inner parts of the brains of the nègres he dissected possessed a darker bluish (bleuâtre) colour, caused by an elusive cerebral fluid, which he called ‘Oethiops’.Footnote 45 Most empirical anatomists, from Malpighi on, debated the role of humoral imbalance which they supposedly observed in the tissues of dark-skinned Africans, as claimed the English naval surgeon John Atkins (1685–1757).Footnote 46 The research of these scholars only partially aligned with the dissection of the cadaver of Saartje Baartman (1789–1815), the famous ‘Hottentot Venus’, by the French anatomists Georges Cuvier (1769–1832) and Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (1777–1850), since neither Cuvier nor de Blainville was interested in the specific issue of locating skin colour.Footnote 47

Overall, the small number of documented anatomists who dissected African cadavers suggests that the practice remained marginal in Europe until at least the last third of the eighteenth century. In his extensive survey of early modern literature on physical anthropology, Renato Mazzolini identified over four hundred publications (excluding dictionaries and encyclopaedias) which discussed the problem of skin colour – or used it for human classification – across a wide variety of fields from 1640 to 1849.Footnote 48 Mazzolini’s quantitative study shows how scientific discussions started to overtake the general literature on skin and race in volume during the first decade of the eighteenth century; this trend continued from the 1730s to the late 1750s, before peaking from the last third of the eighteenth century until the middle of the nineteenth.Footnote 49 Within this corpus, Mazzolini found at least thirty-eight dissections of African human remains in Europe during the period 1675 to 1810, carried out by an unspecified number of scholars; my own survey, which include the little-known dissections by Bäck and Duverney, identified at least fifteen of these dissectors.Footnote 50 Combining these estimates suggests that dissections of ‘Ethiopian’ human remains accounted for only about 4–10 per cent of the vast early modern European corpus on race.

Bäck was about to become part of this small community and, as we will see, he even trained with several of its members. Most Swedes at the time had to travel abroad to receive hands-on – that is, ‘empirical’ – training in anatomy.Footnote 51 Like most northern Europeans, Bäck had never seen an individual of African descent until leaving his home country. Sub-Saharan Africans were rarer in Sweden than in many other European countries, and Bäck recorded that ‘Africans only rarely travelled to Sweden’, a fact which must have made the cadaver in Paris even more valuable in his eyes.Footnote 52

Bäck’s interest in skin colour originated from his studies in Leiden in the spring and summer of 1742 under the famous empirical anatomist Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, one of the leading European experts on ‘Ethiopian’ skin in the period and himself a student of the anatomists Govard Bidloo, Fredrik Ruysch, and Herman Boerhaave.Footnote 53 An alumnus of the Jardin du Roi, Albinus had secured for himself access to an unidentified female ‘Ethiopian’ cadaver in Leiden, which he dissected in 1737 and published about in a famous eighteen-page in quarto dissertation, On the cause and location of the colour of Ethiopians and other humans.Footnote 54 Albinus’s dissertation typically leveraged his empirical experiments to tackle the problem of skin tone variation. He had noted that, even when factoring in regional differences, no consensus seemed to exist between ‘illustrious anatomists’ on the overall complexion of ‘Ethiopian skin’: Malpighi had previously described the outer skin (epidermis) of ‘Ethiopians’ as ‘white’ (albam), while Ruysch described it as ‘grey’ (cineream), and the Venetian anatomist Santorius Santorio as ‘black’ (nigram).Footnote 55

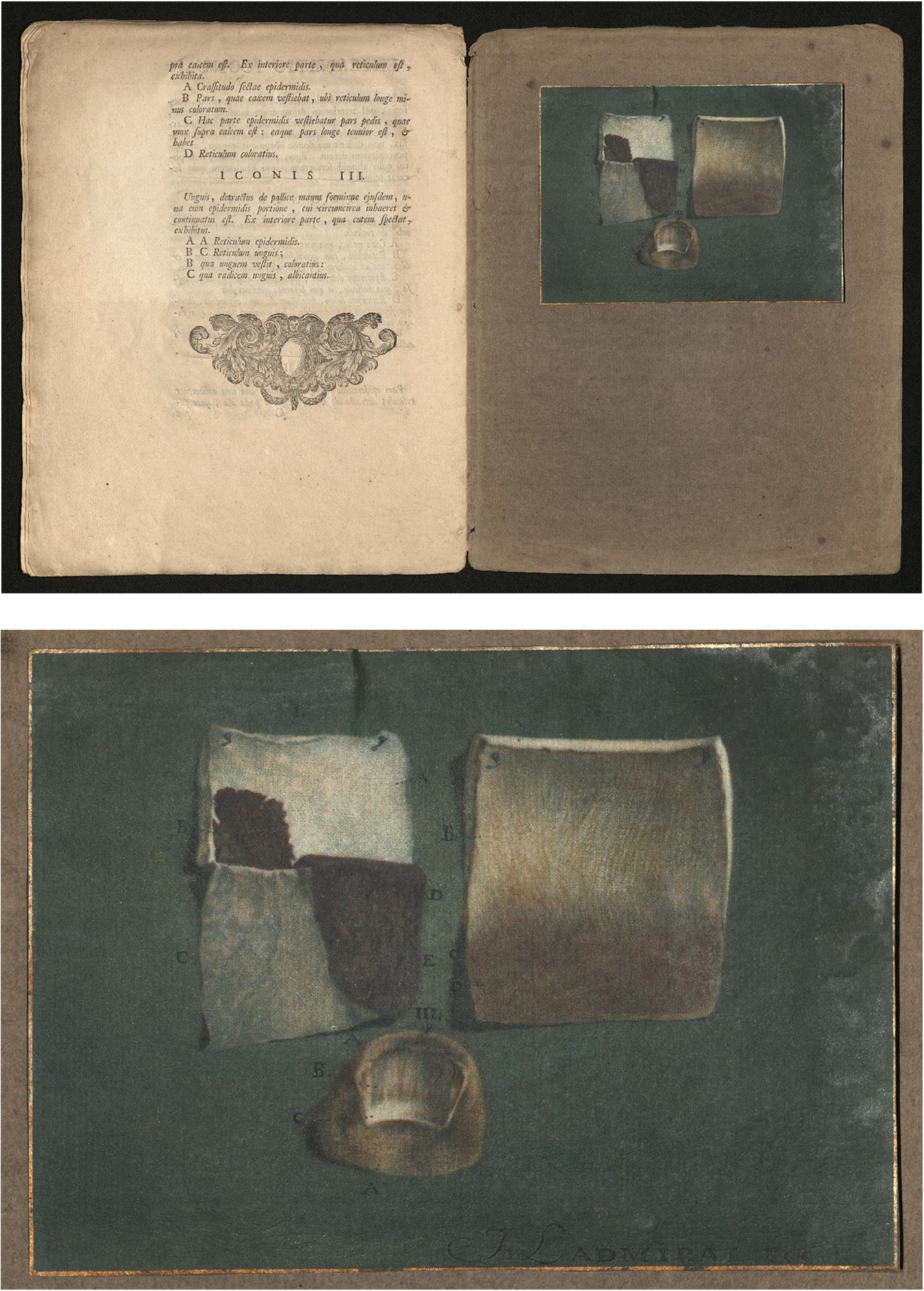

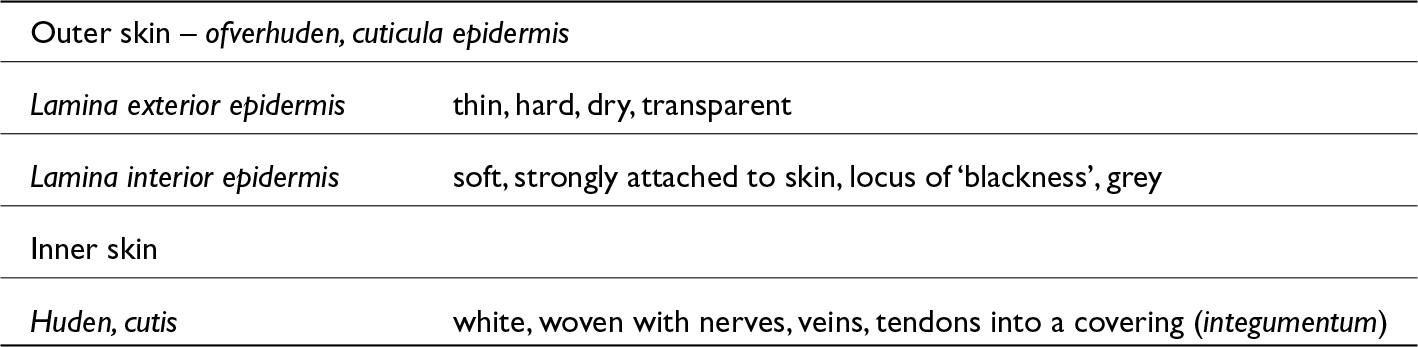

These disagreements reflected a double tension: as noted by Richard Bellis, epistemically, not all anatomists believed that the consistency of their sensory perception would be ensured by God.Footnote 56 Materially, the few northern European anatomists who dissected ‘Ethiopian’ cadavers operated on bodies with different skin tones, while paintings and black-and-white engravings of dark-skinned people were often considered sceptically by anatomists, due to the perceived unreliability of pigments and the subjectivity of artistic licence.Footnote 57 To enhance his claims, Albinus commissioned his engraver Jan l’Admiral (1698–1773) to produce the first coloured prints of ‘Ethiopian’ skin samples, from the breast, heel, and thumb, using the rare, pioneering trichrome mezzotint printing technique developed by l’Admiral’s master, the German printer Jacob Christoph Le Blon (1667–1741) (Figure 1).Footnote 58

Figure 1. First trichrome representation of ‘Ethiopian’ skin published, crafted by Jan l’Admiral with the mezzotint technique and delineated with gold. Commissioned by Bernhard Siegfried Albinus for his Dissertatio secunda de sede et causa coloris Aethiopum et caeterorum hominum; accedunt icones coloribus distinctae (Leiden and Amsterdam, 1737). The letters and numbers separate the different layers of the skin: III.A. the bare skin (cutis; dermis); I.B. the bare reticulum adhering to the skin and freed from the epidermis; I.C. the epidermis pulled back; I.D. the (fictitious) ‘black’ rete mucosum alone, separated from the skin and likewise from the epidermis; I.E. the roots of the hairs, protracted from the skin and still clinging to the reticulum. Description based on Koslofsky, ‘Superficial Blackness’, p. 149. Plate scanned by, and reproduced with courtesy of, the Hagströmer Library, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

The resulting ground-breaking coloured prints were praised by many anatomists, and represented a pivotal, yet short-lived, moment in the history of anatomical printing during which human flesh was represented in colour with exceptional nuance over two decades (1721–42).Footnote 59 Nevertheless, the most striking feature of the ‘Ethiopian’ colour print is that the intermediary dark viscous membrane (rete mucosum) depicted (see Figure 1, letters D and E) does not, in fact, exist anatomically, a blatant case of the very artistic licence that Albinus had denounced. Still, the plate didactically represented the dominant view of ‘black’ skin structure in the period and, as we will see in part III, it served as a template for Bäck’s article.

II

Less than a year after his studies in Leiden, Bäck resumed his anatomical training at the Jardin du Roi. The Jardin was one of Paris’s leading anatomical and botanical institutions, and one of several institutions to host public anatomical dissections within a dedicated amphitheatre, led in Bäck’s time by famous physicians such as Jacob Bénigne Winslow (1659–1760).Footnote 60 Lessons at the Jardin were popular among foreigners like Bäck, as they were open to all, given in French rather than Latin, and allowed visitors to pursue their training by taking private lessons with the demonstrators. Bäck’s untranslated diaries reveal that he attended a series of six dissection sessions in February 1744, led by Winslow and the elderly Jacques-François-Marie Duverney (1661–1748), the first titular démonstrateur d’anatomie at the Jardin du Roi, and a member of the famous Duverney family.Footnote 61

The eighty-three-year-old Duverney strikingly led the first lesson, during which Bäck witnessed for the first time the dissection of an unidentified male cadaver ‘from Ethiopia’ (ex Aethiope).Footnote 62 This must have made a strong impression on Bäck, since he soon acquired (possibly for an unknown sum) several samples of skin from the arm, sole of the foot, and buttocks of the cadaver, and recorded that he conducted experiments on these remains for at least a week.Footnote 63 The preservation of human remains from decay was a major issue of anatomical science until the generalization of formaldehyde in the 1880s.Footnote 64 In Bäck’s time, a cadaver was ideally to be dissected within twenty-four hours after death, although small fragments of skin could be used for longer if kept in water or alcohol solutions.Footnote 65 Bäck was familiar with these techniques, and several of his experiments involved soaking skin samples in various liquids to better untangle their structure:

When the Negro’s skin has been soaked for a long time, and the epidermis is removed, this blackness is to some extent dissolved and colours the water blackish, so that drops remain on paper, as if from a very weak ink. If you keep some preparations of the Negro’s skin in brandy, over time a pile of jet black will fall to the bottom of the glass, and the blackness of the Negro’s skin will decrease … Long soaking also loosens the hair, which is found over all the human body, albeit in different lengths.Footnote 66

As we will see, Bäck even kept dried samples of the cadaver’s skin to be brought back to Sweden.Footnote 67

Paris was an ideal place for Bäck to conduct such experiments: during the first decades of the eighteenth century, the French metropolis was renowned for allowing students to dissect ‘in the Paris manner’ instead of merely watching professors.Footnote 68 As shown by Rafael Mandressi, by law the faculty of medicine of Paris held a monopoly for the dissection of cadavers, supplied from executed prisoners and the graves of the unclaimed poor. In practice, however, students also dissected at the Collège Royal, the Hôtel Dieu, the Collège Saint Côme, and the Hôpital de la Charité; various rivalries and tensions arose between these institutions due to the limited supply of available corpses.Footnote 69 Prominent anatomists from those medical institutions also conducted private dissections at home for profit, using their institutional connections to secure the necessary bodies; famous examples include Winslow, Jean-Joseph Sue le Père (1710–92), César Verdier (1685–1759), and Antoine Ferrein (1693–1769); but there were also numerous amateurs and student groups, who dissected cadavers of dubious freshness in precarious and hazardous hygienic conditions.Footnote 70

As Mandressi has shown, such was the success of the empirical Paris manner that the official quotas of cadavers were largely insufficient to meet growing demand, a situation which led to an extensive underground economy of corpse trafficking in Paris.Footnote 71 Body snatching and corpse trafficking had been rampant in the French capital since the seventeenth century and, as the city’s reputation as a centre for hands-on anatomical training grew in Europe, the phenomenon increased further in the first decades of the eighteenth century.Footnote 72 According to Mandressi, it was not rare to see fresh corpses be snatched by force from the hands of executioners; indigent individuals were often coerced into selling their future corpse by contract, a situation which led the famous writer and philosopher Louis-Sébastien Mercier (1740–1814) to denounce the iniquitous exploitation of the remains of the poor after their death, in his popular book Tableau de Paris (1781).Footnote 73 It was commonplace for doctors to bribe gravediggers for fresh corpses entombed in unnamed graves, while traffickers raided cemeteries to resell even half-rotten corpses at astronomical prices in times of high demand during the academic year, with the average price of a corpse fetching up to 100 livres, and up to 150 livres on the underground market.Footnote 74

III

Nearly four years after his experiments, Bäck published his conclusions, following a well-received presentation during which he produced dried skin samples for members of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences.Footnote 75 His article was swiftly published in the academy’s Transactions – Sweden’s most prestigious scientific journal – under the title ‘Opinion on the black skin of negroes’ (‘Rön om negrernas svarta hud’). This short essay (six and a half pages in octavo) featured a summary of the dominant conjectures on ‘black skin’, covering both climatic and humoral theory, skin structure, and Judaeo-Christian theology. The article more broadly aimed to showcase Bäck’s mastery of international literature, his dissecting skills, and his empirical experiments on a scarce anatomical resource. While his skin research only represented a small part of his overall output, the article crucially showed that Bäck possessed all the desirable qualities of a modern empirical anatomist. Many of his colleagues envied his impressive foreign credentials and expertise gained abroad.Footnote 76

Bäck began the article with his views on the structure of human skin. The skin’s ternary division had long been disputed in the early modern period, being classically divided in two since antiquity.Footnote 77 Disagreements over the location of dermal ‘blackness’ partly arose from competing anatomical views about skin structure: those who regarded skin as composed of only two parts, such as the early Montpelier physician Jean Riolan the younger or the Dane Thomas Bartholin, had identified the outer skin as ‘black’ and the inner skin as ‘white’.Footnote 78 Bäck, however, claimed that such errors resulted from the improper use of boiling water, which made dark pigments artificially fuse with the inner part of the skin.Footnote 79 As shown by Craig Koslofsky, since the experiments on ‘Ethiopian’ skin of Malpighi’s De externo tactus organo anatomica observatio in 1665 and Johannes Pechlin’s De habitu et colore Aethiopum in 1677, anatomists with a more complex understanding of skin structure had been claiming to observe an intermediary layer, which Albinus had ‘highlighted’ in his trichrome illustrations (see Figure 1, letters D and E) as distinct from the transparent cuticle (see Figure 1, letter C). Malpighi had named this layer rete mucosum, and had theorized that it was filled with a dark mucous liquid (mucosum) which allegedly gave it its dark colour.Footnote 80 Although this layer was a mere viscous fluid of the decomposing lower epidermis, the myth of a dark inner layer persisted until it was definitively supplanted by the cell theory in the nineteenth century.Footnote 81 In the meantime, the myth was popularized further by Voltaire in the second half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 82 Overall, the case of the Malpighian rete mucosum provides a telling example of how empirical anatomists racialized bodily putrefaction, claiming to observe a membrane which did not exist.Footnote 83

Despite its growing influence, the myth of the ‘black’ inner layer actually did little to settle the question: while anatomists such as Johannes Pechlin used the rete mucosum as evidence that skin colour must be a mere superficial layer that had nothing to do with the composition of the blood, others like Barrère and Buffon argued that the so-called dark mucosum liquid probably originated from humoral imbalance, noting, as Koslosfky has shown, that anatomists who claimed to have solved the problem ‘Why is African skin black?’ merely shifted the question to ‘Why is their blood or bile black?’Footnote 84 Although the classical temperaments distinguished between a healthy preponderance of humours and the pathological notion of imbalance, the idea that a perpetual influx of black bile could turn someone’s skin ‘black’ implied a state of constant imbalance, in the same way that jaundice could temporarily turn someone ‘yellow’. The notion of innate humoral imbalance thus seemed to provide a simple enough answer to the question and often emphasized heredity at the expense of climate, even though these positions were not always regarded as contradictory.

Bäck’s neo-humoralist views were in line with this shifting consensus: in agreement with Malpighi and Albinus, he identified the lamina interior epidermis as an intermediary layer which he regarded as the true location of dermal colour. Using a microscope, he observed that colour did not seem to lie in the greyish external layer of the epidermis (lamina exterior epidermis), nor in the ‘white’ cutis or dermis, the thick layer of tissue below the epidermis which forms the skin and contains capillaries, nerves, sweat glands, and follicles.Footnote 85 Bäck’s skin model acknowledged tradition while keeping up with contemporary knowledge: it divided human skin into two main parts, while further subdividing the outer part into two sub-layers, effectively splitting the skin in three, as Malpighi, Pechlin, and Albinus had done (see Table 1).

Table 1. The structure of the human skin, according to Abraham Bäck

Source: based on Bäck, ‘Rön om negrernas’.

Although Bäck subscribed to the dominant myth of a viscous inner dark membrane, like his former teacher Albinus, he noted disagreements among anatomists over its supposed colour, recording that Riolan and Santorio believed the mucosum to be ‘black’ (svart) whereas Malpighi, Littré, and Boerhaave thought it to be ‘white’ (hvitt).Footnote 86 Bäck in fact sided with Ruysch and Albinus in declaring that the layer actually looked ‘grey’ (grått) to the naked eye, but he was puzzled that the Paris cadaver’s eyeballs were ‘white’, that the inner layers of the skin were also ‘white’, and even that its blood was similar in colour and texture to blood found in European cadavers: Bäck considered all these features to be inherently characteristic of non-African people.Footnote 87 In line with Linnaeus’s taxonomic method, Bäck relied on identifying similarities, variations, and differences to outline his normative human type. However, like Buffon, he also perceived ‘Ethiopian’ skin colour as a distinct hereditary variation from a normative ‘white’ spectrum dominant across the globe: ‘I cannot avoid mentioning on this occasion the question, which no one has yet been able to answer, how is it that one or another people are and remain in all their families black, when the rest of the masses of men are white, at least to some degree.’Footnote 88

As we have seen, Bäck argued that ‘whiteness’ could be restored via simple experiments, such as a prolonged rubbing with or immersion in alcohol (which bleached the higher layers of the epidermis), an effect long identified as a consequence of ethylic preservation of skin tissues.Footnote 89 Nevertheless, the hereditary nature of the dark skin colour of ‘Ethiopians’ called for a theory capable of explaining its transmission. On this point, most early modern scholars oscillated between predominantly climatic, sanguine, or humoral explanations. Cristina Malcolmson has shown how the Royal Society favoured research which emphasized neo-humoral theory and human differences in dark-skinned Africans.Footnote 90 Quoting works published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Bäck similarly noted that ‘maybe some mixing takes place in their bags of Vitriolic and bitter [humors] … whatever stands best to reason. Those who hereafter have the opportunity to open Negros know to not forget to notice that their bile is always black.’Footnote 91

This, Bäck argued, might be the true cause of their colour, as it was well known that humours could change the colour of the skin, from red bursts of anger to a sickish yellow or extreme paleness. In doing so, he challenged earlier anatomists such as Riolan the younger, who had concluded against the predominance of dark humours in sub-Saharan Africans and espoused the classical climatic views of Aristotle, Aristobolus, Strabo, or the Renaissance geographer Abraham Ortelius (1527–98), all of which Bäck rejected in his article.Footnote 92 Reducing skin pigmentation to prolonged exposure to warm sunlight seemed unlikely to Bäck, as Africans obviously did not lose their skin colour when moving to colder latitudes, an argument popularized earlier by Bernier.Footnote 93 Like most eighteenth-century anatomists, Bäck tended to discuss ‘black skin’ as a bodily disorder or a disease: at the end of his article he compared it to recurring streaks of smallpox on a ‘fair Englishman from Dover’, whose skin regularly became ‘black’ and covered in dark fluid-filled blisters, which, when dry, formed a ‘black crust’ that seemed to ‘always come back’, despite all known treatments.Footnote 94 Bäck thus viewed the ‘black’ skin of ‘Ethiopians’ as a largely inescapable condition transmitted hereditarily and rooted in humoral temperaments, an increasingly popular view in the French anatomical circles in which he was trained.Footnote 95

At this juncture, it is important to consider how Bäck’s ideas on human differences related to his Christian faith, especially since, as we have seen, theology was the main framework through which race was discussed in the early modern period.Footnote 96 After all, his emphasis on heredity was partly rooted in his Lutheranism, and his neo-humoralist views did not necessarily push him towards polygenism, nor did they place him in tension with mainstream Christianity. Before turning his efforts to anatomy, Bäck had contemplated priesthood and, although he did not proceed to ordination, he later became an early member of the Societas Svecana pro Fide et Christianismo (the Swedish Society for Faith and Christian Life), a religious institution involved in Christian evangelization and education which was modelled after the British Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.Footnote 97

In his article for the Transactions, Bäck regarded the curse of Ham given by Noah to the descendants of Canaan as a more plausible cause of black skin than classical climatic and geographical explanations.Footnote 98 The curse of Ham had been a widespread trope since the seventeenth century, presenting dark-skinned Africans as the descendants of Canaan, subjugated by the Egyptians and the Hebrews as the result of a curse.Footnote 99 Perhaps aware of the recurring objections that no mention of skin colour was explicitly found in the biblical text itself, Bäck speculated that ‘black skin’ might be a mere physical manifestation resulting from the ‘progenitors’ imagination’ that a curse had been bestowed upon their ancestors long ago, and then transmitted by the mother: ‘It is still easier to situate their explanation as belief, that the Negroes’ blackness came from the curse that God let fall on the descendants of Cham, or that the imagination of the progenitors caused this blackness to become an inheritance in the family.’Footnote 100

This was an original stance, which echoed widely held beliefs that thoughts from the pregnant mother could influence the skin colour of a child, and even manifest as birthmarks on foetuses.Footnote 101 It also echoed the conclusions of Robert Boyle in his Experiments and considerations touching colours (1664), in which Boyle had concluded that ‘black skin’ was ‘some peculiar and seminal impression’ which could not be reduced to climate.Footnote 102 While Bäck’s medical interpretation of the curse did not interfere with his monogenism, it still stood at odds with some of his academy colleagues: Linnaeus did not write on biblical conjectures used to justify racial inferiority like the curse of Ham, while others such as the philosopher and theologian Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) started producing detailed exegetical refutations of the curse of Ham in the 1740s, contending that ‘Africans’ were actually superior to all other peoples.Footnote 103 Most of the essayists of the Bordeaux contest also rejected the validity of the curse of Ham, including the Swede Eric Molin (1709–?), who had drawn on Swedenborg’s physico-theology for his essay The origins of blackness in the Moors (1742).Footnote 104 Bäck’s medical explanation of the curse of Ham, though quite typical for the period, thus represented one of the most original aspects of his views on race.

IV

Bäck’s experiments on skin colour were received enthusiastically by his Swedish peers. Before presenting his results to the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, he likely shared his findings with his old teacher, the Swedish physician Nils Rosén von Rosenstein (1706–73), a former rival of Linnaeus.Footnote 105 Bäck had been a student of Rosén von Rosenstein before his Grand Tour, regularly corresponded with him, and was said to have acquired his strong empirical taste from him.Footnote 106 Although mostly remembered today as a founder of paediatrics – and, like Bäck, as a reformer of public health – Rosén von Rosenstein was an important promoter of medical empiricism in Sweden during Bäck’s time, and personally supported the latter’s results for publication in the Transactions of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences.Footnote 107

Bäck’s article quickly cemented his own reputation as one of the leading medical empiricists of his home country. Nevertheless, in line with most dissections of African cadavers in the eighteenth century, his technical research on skin colour attracted few readers. Its most overlooked legacy is as a possible influence on the humoral taxonomic turn of Carl Linnaeus, which took place from 1748 to 1758. The tenth edition of Linnaeus’s Systema naturae, published in Stockholm in 1758, marked the most extensive update of Linnaeus’s human classification: in this edition, the famous naturalist added innate humoral temperaments and dismissive behavioural inclinations to his four main ‘human varieties’ (Americanus rubescens, ‘reddish American, choleric and straight’; Europæus albus, ‘white European, sanguine, muscular’; Asiaticus fuscus, ‘tawny/brown Asian, melancholic, stiff’; Africanus niger, ‘black African, phlegmatic, slack/lazy’) in relation to their supposed geographical spread across the globe.Footnote 108 However, as shown by Isabelle Charmantier, the beginning of Linnaeus’s humoral turn can be traced to ten years earlier, back to his Anthropomorpha manuscript started in 1748, the same year as Bäck’s article was published.Footnote 109 As an active founding member of the academy, Linnaeus must have been aware of his best friend’s publication in the Transactions, and their personal correspondence shows that Linnaeus spent two evenings in Stockholm with Bäck discussing their latest research shortly before the article’s publication.Footnote 110

Still, with no extant reference to Bäck’s article in Linnaeus, it would be difficult to prove that the famous naturalist borrowed from his friend’s work. Linnaeus’s final human taxonomic model, which has been studied extensively by Gunnar Broberg, Isabelle Charmantier, and Staffan Müller-Wille, also exhibited notable differences from Bäck’s: Linnaeus attributed the dominance of black bile not to Africans but to Asiaticus fuscus, and phlegm to Africanus niger, two ‘human varieties’ whom he regarded as both possessing darker skin tones.Footnote 111 This also allowed Linnaeus to fit widespread literary accounts of the supposed ‘laziness’ of ‘Africans’ with their alleged ‘phlegmatic’ temperament.Footnote 112 This article is, however, less concerned with the narrow question of influence than with highlighting a growing European interest in human differences and ‘black’ skin colour across the fields of natural history, empirical anatomy, and theology; in this regard, it is already significant that such debates existed in Sweden during Bäck’s time, as they pre-dated the country’s involvement in the slave trade by nearly four decades.

The connections between Linnaeus’s and Bäck’s research also highlight the new dimension taken by Bäck’s medical expertise upon his return to Sweden. Linnaeus was not the leading expert on skin colour, humoralism, and race in Sweden: his best friend, Abraham Bäck, was. Although research on human differences only represented a small part of their respective oeuvres, Linnaeus continued to seek Bäck’s input on the subject, for instance on his revised Anthropomorpha dissertation on the classification of quasi-human simian types, defended at Uppsala in the year 1760.Footnote 113 Despite this, Bäck’s research on skin received only little exposure in European periodicals.Footnote 114 One reason behind this lack of international impact was the limited reach of the Swedish Transactions at the time. According to the academy’s co-founder Mårten Triewald (1691–1747), the Transactions were in Swedish because they were meant ‘not so much to benefit foreigners as to benefit our own countrymen’.Footnote 115 Notices and translations mostly appeared in learned journals from Germany and Holland, the countries then most aligned with Swedish intellectual culture.Footnote 116 Interest in the topic was also strong in France and Holland in the 1740s, meaning that francophone recensions of Bäck’s research would have been crucial to maximize its international impact.Footnote 117 However, due to an untimely change of print policy in the famous Bibliothèque raisonnée, Bäck’s research was mentioned in only one minor francophone journal, dedicated to northern European scholarship.Footnote 118 Two translated reprints were later published in Venice and Holland, but both were part of wider catalogue reissues of the Swedish Academy’s Transactions.Footnote 119

This did not concern Bäck, who made little effort to promote his research on skin further. Having already gained recognition from his Swedish peers and satisfied his curiosity at a time when Sweden was still largely uninvolved in the slave trade, he never published again on the subject.

V

The debate about the origins and causes of ‘Ethiopian’ skin colour was one of the most unsettling of the Enlightenment: it led to dehumanizing experiments and bizarre anatomical claims, while remaining widely contested. This article has explored how Abraham Bäck, as a young anatomist from Sweden, came to develop an interest in race and human differences while travelling across Europe. By re-tracing the trajectory of his research on skin, we have seen more broadly how a small group of early modern European empiricists exploited the scarce human remains of African individuals within a growing culture of empirical anatomical training and competitive knowledge-building. Although the early modern fascination with skin and race extended well beyond the circles of empirical anatomists, I hope to have underlined a key aspect of the social and material aspects which shaped their studies.

By looking at the rise of Bäck’s experimental culture of racial anatomy within the wider early modern fascination with human differences, we also get a better understanding of what prompted the emergence of such a practice in the first place. As we have seen, dissections of African cadavers remained statistically marginal in early modern Europe, yet they played a crucial role in supporting the demise of older climatic explanations and the rise of neo-humoral theories of racial heredity. Bäck’s case represents a telling illustration of this phenomenon. His unsettling experiments on African human remains, while little known, foreshadowed Carl Linnaeus’s humoral turn, and live on in the early history of scientific racism. More broadly, Bäck’s training networks open pathways for further investigations, with more work to be done on the links between medical empiricism, colonial collecting, and racial science in northern Europe.

Finally, Bäck’s experiments help us shift how we think about medical racial science in the period: African cadavers were sought after to produce new medical knowledge in Europe partly because of their scarcity within medical circles. The emergence of an empiricist racial science in Europe was thus made materially possible by the wider socio-economic structures which underpinned the marketization of early modern anatomical dissection, along with its intersection with the slave trade. In this increasingly exploitative landscape, the anatomists’ varied motivations proved easily reconcilable with incentives to identify human differences for personal gain.

Acknowledgements

My gratitude to the reviewers, editors, and scholars who provided me with insights and materials for this research, especially Maria Asp, Karl Grandin, Lo Barck, Hjalmar Fors, Eva Århen, Michael Sappol, Petter Hellström, Hanna Hodacs, Linda Andersson Burnett, Marie-Christine Skuncke, Staffan Müller-Wille, Arthur Asseraf, Benoît Pouget, John Lidwell-Durnin, Erica Charters, Rob Iliffe, Meleisa Ono-George, Craig Koslofsky, Andrew Curran, Carl Wennerlind, and Fredrik Albritton Jonsson.

Funding statement

This research has received funding from the British Arts and Humanities Research Council at the University of Oxford, the Catarina och Sven Hagströmers Stiftelse at Karolinska Institutet, and the European Research Council (ERC ‘DEPE’, 101088549 funded by the European Union) at the University of Jyväskylä. Views and opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders, the European Union, or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authorities can be held responsible for them.

Competing interests

The author declares none.