Introduction

Meta-analytical evidence suggests that cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is effective in treating depression in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders, Purgato and Barbui2018). Despite this encouraging data supporting the efficacy of CBT, little progress has been made in implementing the wide-scale delivery of CBT in LMICs. A lack of awareness of modern psychotherapies, restricted resources, social and cultural norms, and services mainly located in bigger cities contribute to this. CBT also requires a person to be literate. Pakistan has a literacy rate of 60% (www.pbs.gov.pk). There is a need to develop low-cost interventions that can address the ‘educational literacy barrier’ in LMICs to improve access to evidence-based interventions such as CBT for marginalized populations. To address this gap, we developed an animated ‘Shorts’ (short videos) series on stories from a previously developed culturally adapted CBT-based self-help book, Khushi or Khatoon (www.pact.com.pk), for people with low or no educational literacy. This preliminary study aimed to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the intervention.

Objectives and hypothesis

Primary objective

To assess the feasibility and acceptability of the culturally adapted (CaCBT) Shorts intervention to treat anxiety and depression in persons with low or no education in Pakistan.

Primary hypothesis

A CaCBT Short intervention will be feasible to deliver and acceptable to the participants.

Secondary objectives

To gather preliminary data on clinical variables, including changes in depression scores, that can inform sample size calculations for a future efficacy trial.

Secondary hypotheses

CaCBT Shorts intervention will be associated with improvements in depression, anxiety and functioning compared to TAU at 3 months, providing preliminary signals to inform the design of a future efficacy trial.

Method

Study design

This randomized, rater-blind trial assessed the feasibility and acceptability of an animated Shorts series. The study was conducted between September 2022 and November 2023. Participants meeting the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to one of the groups: an animated Shorts series plus TAU (intervention group) or TAU (control group) in a 1:1 ratio.

Study setting and participants

Primary care physicians recruited participants from rural health centres on the outskirts of Lahore. None of the individuals had a previous diagnosis of a mental illness, and no one had prior contact with mental health services. Participants were assessed at baseline and the end of the intervention at 12 weeks by trained clinical research assistants (RAs) blinded to treatment allocation. All assessments were performed over WhatsApp calls. WhatsApp was also used for weekly check-ins to provide guided support. They were supervised by M.G.

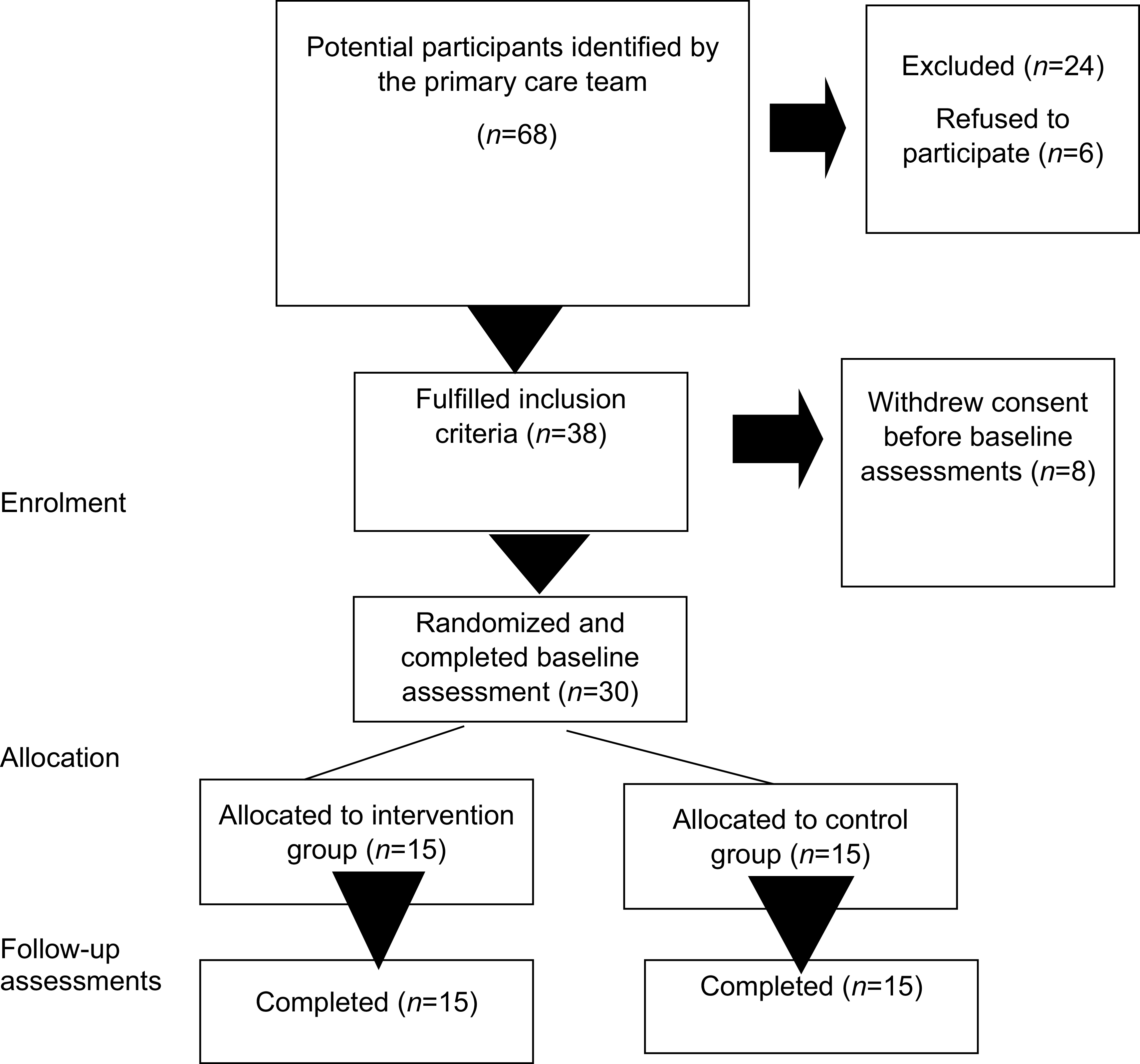

The trial was conducted in Lahore, Pakistan. Individuals aged ≥18, with less than 5 years of schooling, having access to a mobile device with a messaging app to receive videos and a secure and reliable internet connection, who scored ≥8 on the anxiety or depression subscale of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale were recruited from primary care clinics in Lahore. Information about the study was provided in a video format. Individuals who consented to participate in the study were assessed for suitability in the trial by RAs who were blind to the intervention arm. We aimed to recruit 30 participants, to account for a potential 50% loss to follow-up. Given that the primary aim of this study was to establish feasibility, no power calculation was conducted. The sample size was informed by published guidance that a sample size of at least 12 participants in each arm of a pilot/feasibility randomized controlled trial (RCT) is necessary (Julious, Reference Julious2005). Participants meeting the inclusion criteria were randomly allocated to one of the groups. Randomization was conducted using the Sealed Envelope platform (https://www.sealedenvelope.com/) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT flow diagram of the trial.

The interventions

Participants in the intervention group received a culturally adapted animated Shorts series as guided self-help and TAU. Participants in the control group received only TAU. Animation videos of 3–5 minutes duration were created using online software (vimeo.com) and can be accessed on our YouTube channel (https://www.youtube.com/@pactpakistan1934). Participants received 1–2 videos per week via a secure WhatsApp connection over 12 weeks. RAs supervised by a senior member of the team called participants once a week for 15–20 minutes to discuss the current week, gain feedback from the previous session and discuss homework assignments. They also sent two reminder messages per week to each participant. Participants in the TAU group received the intervention at the end of the study period.

The animated Shorts series tells the stories of a man and a woman who use CBT techniques to address symptoms of depression and anxiety. The intervention focuses on cognitive restructuring, problem-solving, behavioural activation, conflict management, interpersonal relationships, mental health well-being, and self-care. The intervention incorporates culturally relevant stories, illustrations, folklore examples, and religious context to convey CBT concepts appropriately.

Treatment as usual (TAU)

This consisted of standard care under the responsible family physician, which usually involves pharmacological therapy with anti-depressant medication and follow-up in an out-patient clinic. None of the participants in either arm was receiving a mental health intervention.

Outcome measures

The primary measures were feasibility (recruitment, retention, adherence to treatment and trial processes) and acceptability (drop-outs and participants’ feedback on helpful or unhelpful sessions and suggestions to improve the intervention). The secondary outcomes included the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond and Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983) and the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2 (WHODAS 2) (Üstün et al., Reference Üstün, Chatterji, Kostanjsek, Rehm, Kennedy, Epping-Jordan, Saxena, von Korff and Pull2010). All assessments were carried out over the telephone. The HADS is a self-rating scale consisting of 14 items, seven of which are designed to measure anxiety (HADS-A) and seven for depression (HADS-D). The sum of the individual items provides subscale scores on the HADS-D and the HADS-A, which may range between 0 and 21. A cut-off point of ≥8 for each constituent subscale indicates probable caseness. The WHODAS 2 assesses disability resulting from physical and psychological issues. Both instruments have been used extensively in Pakistan.

Statistical analysis

The analyses were carried out using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 28. Continuous variables were summarised using means, standard deviations, medians, and interquartile ranges as appropriate. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. Baseline comparisons were made using chi-squared and t-tests. Comparisons between two groups at two time points in psychopathology and disability were measured using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to account for differences at baseline.

Results

The primary care physicians identified 68 individuals; 30 participants met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 provides a summary of the included participants’ baseline characteristics. We recruited the required number of participants within the target time. There were no drop-outs from either arm of the study, and we had a 100% retention. Participants who completed less than 5 of the 7-week program were considered drop-outs. The intervention group showed excellent adherence, with 80% (12/15) completing all the 7 weeks. Two participants completed 6 weeks, and one completed 5 weeks. All participants were available for end-of-intervention assessments at 12 weeks. All those who completed the study reported the intervention as easy to understand and easy to use. At the end of the intervention, participants were called by the RAs, who asked them three questions: (1) which part of the intervention did you like the most?; (2) which part you did not like?; and (3) how can we improve this intervention? Participants reported that breathing exercises (12/15), food and mood (12/15), problem-solving (9/15), activities (9/15), and dealing with thoughts (8/15) were helpful. Ten participants emphasized the need for a local language, such as Punjabi, rather than the national language, Urdu. Three participants said they would like the main characters to be real human beings.

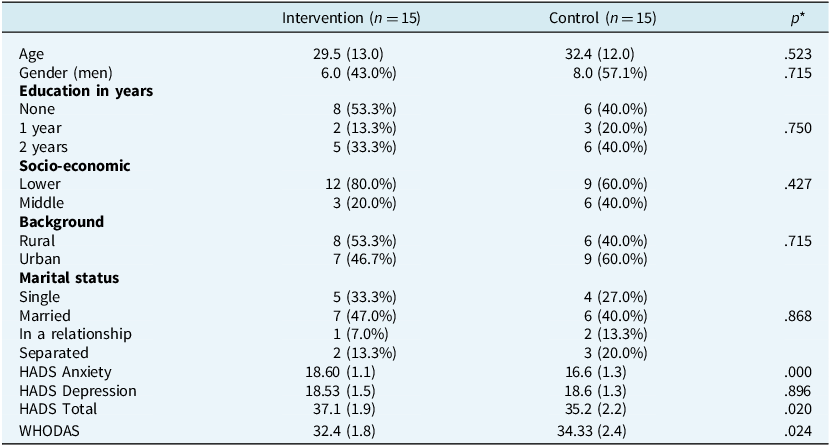

Table 1. Differences in demographic variables and psychopathology between the intervention and the control groups at baseline

The figures for demographic details are mean (standard deviation) for age and clinical metrics, while the rest are sample size (% within treatment group). *p-values calculated using, non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables (age and clinical metrics) and Fisher’s exact test for the rest of variables which were categorical.

There were statistically significant differences between the two time points in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and disability in favour of the intervention arm after controlling for the baseline differences. Participants in the intervention group showed significantly more improvements in depression (HADS-Depression subscale) [mean difference=3.65, CI (2.6–4.7), p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.79], anxiety (HADS-Anxiety subscale) [mean difference=4.2 CI (2.8–5.6), p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.8], total depression and anxiety (HADS-Total) [mean difference=7.9, CI (6.3–9.5), p<0.0010, Cohen’s d=0.89] and disability (WHODAS 2) [ mean difference=3.7, CI (2.0–5.3), p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.69] from baseline compared with the participants in the control group at 12 weeks.

Discussion

This is the first report of a culturally adapted CBT-based animated Shorts series intervention to address depression and anxiety for people with no or low literacy. The feasibility of conducting an RCT for our intervention was established by excellent recruitment and retention rates, strong adherence to the intervention, and no challenges in completing our clinical assessment schedule. Participants gave positive feedback, and the intervention demonstrated preliminary clinical efficacy. The intervention reduced symptoms of depression, anxiety, and disability. As far as we know, no CBT intervention using the dramatization of a story in a video format has been developed or tested to address the educational literacy barrier.

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, 57% of 10-year-olds in LMICs were unable to read and understand a simple text message – the measure for learning poverty (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS). During the pandemic, rates of learning poverty surged dramatically. The total estimation of 10-year-olds who were unable to comprehend an introductory written text, was found to be 70% (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS). Low literacy is associated with several poor health outcomes. Individuals with less education are prone to adopt unhealthy behaviours, struggle in getting chronic disease diagnoses, are unable to manage overall health properly, and eventually have a shorter life expectancy. Low literacy is usually associated with poor mental health (Sentell and Shumway, Reference Sentell and Shumway2003). In addition to these adverse sequelae, low literacy makes it challenging to provide CBT because it requires at least some proficiency in reading and writing to help with homework assignments, filling thought diaries, and reading bibliographic material.

Pakistan is a lower- to middle-income country with a low literacy rate. According to a Pakistani survey conducted in 2018–2019 (www.pbs.gov.pk), the overall literacy rate in Pakistan was 60%, with 69% for males and 51% for females. The highest literacy rate of 64% was reported in the province of Punjab. Sindh has a 56% literacy rate, followed by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (54%) and Baluchistan (41%). More than two-thirds (62.56%) of the population lives in rural areas where the literacy rate is 51%, whereas the urban literacy rate is 74%. However, women are more disadvantaged in rural areas (24 percentage points) than in urban areas (14 percentage points). This poses a significant barrier to providing CBT for a large population in Pakistan. There is a need to address this barrier to provide equal access to disadvantaged populations.

Short videos, popularly termed ‘Shorts’, are popular today on platforms including YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook. Digital video interventions have been used to address three components of mental health literacy: (1) awareness and recognition of mental illness, (2) help-seeking behaviours, and (3) to address stigma related to mental illness. Emerging evidence suggests that video interventions can play a significant role in healthcare. For example, a review of 17 studies showed positive results in favour of video interventions in improving mental health literacy (Ito-Jaeger et al., Reference Ito-Jaeger, Perez Vallejos, Curran, Spors, Long, Liguori, Warwick, Wilson and Crawford2022). However, none of these studies reported an intervention that directly targeted symptoms of mental illness or addressed a lack of educational literacy. The popularity of Shorts is accompanied by online animation-making platforms such as Vimeo (vimeo.com), which provide affordable access to these skills. We decided to use this emerging technology to address the issue of delivering CBT for people with no or low literacy.

Overall, the study’s findings are promising, but replication in a larger confirmatory RCT is required. Future interventions will be modified based on participant feedback. Further research on the cost-effectiveness of low-cost interventions that can be delivered as guided self-help, particularly in LIMC, is essential. Future research should also use formal feasibility, acceptability, and user experience measures.

If the clinical trials of this disability study are validated by a larger population, this low-cost intervention has the potential to play a significant role in managing the symptoms of depression and anxiety in Pakistan and other LMICs which face similar barriers. Given the high prevalence of common mental disorders in these settings, such strategies could help close the substantial mental health treatment gap in LMICs and strengthen public mental health.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465825101173

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/pnx2r/files/jgswr.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Mirrat Gul: Conceptualization (lead), Funding acquisition (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing - original draft (lead); Sadia Abid: Investigation (lead), Methodology (equal), Project administration (lead), Writing - original draft (equal); Nagina Khan: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing - original draft (equal); Madeeha Latif: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing - original draft (equal); Omair Husain: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing - original draft (equal); Falahat Awan: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing - original draft (equal); Muhammad Ishrat Husain: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing - original draft (equal); Mina Husain: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing - original draft (equal); Taj Magsi: Project administration (lead), Software (lead); Saeed Farooq: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal); Muhammad Irfan: Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal); Farooq Naeem: Conceptualization (lead), Funding acquisition (lead), Methodology (lead), Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (lead).

Financial support

Study was supported by an internal grant by Pakistan Association of Cognitive Therapy.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Authors confirm that this research project has conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. We confirm that this study obtained ethics approval from the Pakistan Association of Cognitive Therapy REB Committee (PACT/2023/5052). We confirm that informed consent was obtained from all research participants. Clinical trial Number: NCT05986747. REB Number: PACT/2023/5052.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.