1. Introduction

The propulsion of floating objects due to auto-generated surface-tension gradients, also known as Marangoni surfing, stands as a fascinating phenomenon observed in the world of living organisms while also bearing promising potential for robotic applications. For example, in nature, this mode of locomotion is employed by water-walking insects for speedy movement in emergency situations (Linsenmair & Jander Reference Linsenmair and Jander1963; Andersen Reference Andersen1976; Schildknecht Reference Schildknecht1976; Bush & Hu Reference Bush and Hu2006; Bush, Hu & Prakash Reference Bush, Hu and Prakash2007; Lang, Seifert & Dettner Reference Lang, Seifert and Dettner2012) and by certain bacterial swarms for rapid interfacial migration toward nutrient-rich regions for further colonisation (Harshey Reference Harshey2003; Daniels et al. Reference Daniels2006; Angelini et al. Reference Angelini, Roper, Kolter, Weitz and Brenner2009; Kearns Reference Kearns2010; Fauvart et al. Reference Fauvart, Phillips, Bachaspatimayum, Verstraeten, Fransaer, Michiels and Vermant2012). In the realm of human-made systems, arguably, the most basic form of Marangoni surfing is realised in a camphor/soap boat, where the gradual dissolution of a camphor/soap piece attached to the back of a boat (representative of a floating object) creates a fore–aft surface-tension asymmetry (with associated Marangoni flows) that leads to the self-propulsion of the craft. Over the years, various adaptations of this rudimentary surfer concept have been developed, with sizes ranging from a few micrometres to more than ten centimetres (Kitahata et al. Reference Kitahata, Hiromatsu, Doi, Nakata and Rafiqul Islam2004; Su Reference Su2007; Bassik, Abebe & Gracias Reference Bassik, Abebe and Gracias2008; Soh, Bishop & Grzybowski Reference Soh, Bishop and Grzybowski2008; Shibuya & Matsushita Reference Shibuya and Matsushita2009; Nakata & Murakami Reference Nakata and Murakami2010; Suematsu et al. Reference Suematsu, Nakata, Awazu and Nishimori2010; Soh, Branicki & Grzybowski Reference Soh, Branicki and Grzybowski2011; Jin et al. Reference Jin, Marmur, Ikkala and Ras2012; Li et al. Reference Li, Qiao, Liu and Luo2012; Luo et al. Reference Luo, Li, Qiao and Liu2012; Qiao et al. Reference Qiao, Xiao, Lu and Luo2012; Sharma, Chang & Velev Reference Sharma, Chang and Velev2012; Zhao & Pumera Reference Zhao and Pumera2012; Bansagi et al. Reference Bánsági, Wrobel, Scott and Taylor2013; Renney, Brewer & Mooibroek Reference Renney, Brewer and Mooibroek2013; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Duan, Liu and Sen2013; Burton, Cheng & Bush Reference Burton, Cheng and Bush2014; Pimienta & Antoine Reference Pimienta and Antoine2014; Xiao, Jiang & Shi Reference Xiao, Jiang and Shi2014; Maggi et al. Reference Maggi, Saglimbeni, Dipalo, De Angelis and Di Leonardo2015; Ooi et al. Reference Ooi, Van Nguyen, Evans, Gendelman, Bormashenko and Nguyen2015; Satterwhite-Warden et al. Reference Satterwhite-Warden, Kondepudi, Dixon and Rusling2015; Srinivasan et al. Reference Srinivasan, Roche, Ravaine and Kuhn2015; Girot et al. Reference Girot, Danne, Würger, Bickel, Ren, Loudet and Pouligny2016; Liakos et al. Reference Liakos, Salvagnini, Scarpellini, Carzino, Beltran, Mele, Murino and Athanassiou2016; Musin et al. Reference Musin, Grynyov, Frenkel and Bormashenko2016; Srivastava & Schmidt Reference Srivastava and Schmidt2016; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Yuan, Lu, Tan, Liu, Yu, He and Liu2016; Frenkel et al. Reference Frenkel, Multanen, Grynyov, Musin, Bormashenko and Bormashenko2017; Koyano et al. Reference Koyano, Gryciuk, Skrobanska, Malecki, Sumino, Kitahata and Gorecki2017; Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Corcoran, Garoff, Przybycien and Tilton2017; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Yuan, Qiu, Zhang, Chen and Huang2017; Ivanov & Nikolov Reference Ivanov and Nikolov2019; Löffler et al. Reference Löffler, Hanczyc and Gorecki2019; Morohashi, Imai & Toyota Reference Morohashi, Imai and Toyota2019; Sur, Masoud & Rothstein Reference Sur, Masoud and Rothstein2019; Pena-Francesch, Giltinan & Sitti Reference Pena-Francesch, Giltinan and Sitti2019; Dietrich et al. Reference Dietrich, Jaensson, Buttinoni, Volpe and Isa2020; Sur et al. Reference Sur, Uvanovic, Masoud and Rothstein2021). Notably, some of the more recent and sophisticated versions, such as the robots engineered by Kwak & Bae (Reference Kwak and Bae2017), Kwak, Choi & Bae (Reference Kwak, Choi and Bae2020), Kwak et al. (Reference Kwak, Choi, Maeng and Bae2021), Basualdo et al. (Reference Basualdo, Bolopion, Gauthier and Lambert2021), Timm et al. (Reference Timm, Jafari Kang, Rothstein and Masoud2021) and Bechard et al. (Reference Bechard, Timm, Masoud and Rothstein2023), have demonstrated capabilities applicable to a wide range of tasks, including environmental sensing and monitoring, microfluidic manipulation and self-assembly.

In order to drive continued progress in the development of advanced surfing robots powered by the Marangoni effect, it is imperative to establish a comprehensive understanding of Marangoni propulsion across a spectrum of operating conditions. Among the fundamental research conducted on this subject to date (Kitahata et al. Reference Kitahata, Hiromatsu, Doi, Nakata and Rafiqul Islam2004; Nagayama et al. Reference Nagayama, Nakata, Doi and Hayashima2004; Soh et al. Reference Soh, Bishop and Grzybowski2008; Lauga & Davis Reference Lauga and Davis2012; Masoud & Shelley Reference Masoud and Stone2014; Masoud & Stone Reference Masoud and Stone2014; Würger Reference Würger2014; Malgaretti, Popescu & Dietrich Reference Malgaretti, Popescu and Dietrich2016; Vandadi, Jafari Kang & Masoud Reference Vandadi, Jafari Kang and Masoud2017; Domínguez & Popescu Reference Domínguez and Popescu2018; Boniface et al. Reference Boniface, Cottin-Bizonne, Kervil, Ybert and Detcheverry2019; Gidituri, Panchagnula & Pototsky Reference Gidituri, Panchagnula and Pototsky2019; Crowdy Reference Crowdy2020, Reference Crowdy2021; Jafari Kang et al. Reference Jafari Kang, Sur, Rothstein and Masoud2020; Boniface et al. Reference Boniface, Cottin-Bizonne, Detcheverry and Ybert2021; Ender & Kierfeld Reference Ender and Kierfeld2021), the predominant focus of the theoretical efforts has been centred on cases characterised by negligible advective transport of mass (or heat) and momentum, where the Péclet and Reynolds numbers (represented by

![]() $\textit{Pe}$

and

$\textit{Pe}$

and

![]() $\textit{Re}$

, respectively) approach zero. However, many practical scenarios do not conform to such idealised conditions. Consequently, there is a need for further theoretical insights to inform the design of robots capable of efficiently navigating in these non-ideal regimes.

$\textit{Re}$

, respectively) approach zero. However, many practical scenarios do not conform to such idealised conditions. Consequently, there is a need for further theoretical insights to inform the design of robots capable of efficiently navigating in these non-ideal regimes.

To address the aforementioned demand, we examine the Marangoni-driven motion of a chemically active particle along a flat liquid–gas interface. First, we use the reciprocal theorem to derive a generally valid formula relating the propulsion speed of the active surfer to surface and volume integrals involving, respectively, the concentration and velocity fields around it. We then employ the perturbation theory to evaluate those integrals in the limits of small Péclet and Reynolds numbers and show, to the leading order, how the speed of a purely translating surfer changes as a result of non-zero

![]() $\textit{Pe}$

and

$\textit{Pe}$

and

![]() $\textit{Re}$

. Motivated by our theoretical findings, next, we consider a representative spherical surfer and study its propulsion behaviour over a broad span of

$\textit{Re}$

. Motivated by our theoretical findings, next, we consider a representative spherical surfer and study its propulsion behaviour over a broad span of

![]() $\textit{Pe}$

and

$\textit{Pe}$

and

![]() $\textit{Re}$

values (well beyond the validity range of the theory) via detailed numerical simulations. The results of our calculations are presented in the form of performance regime maps that pinpoint optimal surfing scenarios. Below, we present our theoretical derivations (§ 2), followed by the description of our computational approach (§ 3). The outcomes of our investigation are discussed afterward (§ 4), and concluding remarks are given at the end (§ 5).

$\textit{Re}$

values (well beyond the validity range of the theory) via detailed numerical simulations. The results of our calculations are presented in the form of performance regime maps that pinpoint optimal surfing scenarios. Below, we present our theoretical derivations (§ 2), followed by the description of our computational approach (§ 3). The outcomes of our investigation are discussed afterward (§ 4), and concluding remarks are given at the end (§ 5).

Figure 1. Schematic of a half-submerged spherical surfer located atop an (ideally) unbounded liquid layer. The active area of the surfer is coloured red, and the colour map and vector plots represent the concentration distribution and liquid velocity field in the vicinity of the surfer, respectively.

2. Problem statement and perturbation solution

2.1. Assumptions and governing equations

Consider the motion of a particle located at an interface between a semi-infinite layer of gas and an identical layer of liquid with density

![]() $\varrho$

, viscosity

$\varrho$

, viscosity

![]() $\mu$

and surface tension

$\mu$

and surface tension

![]() $\gamma$

. The movement of the particle is caused by an asymmetric release of a chemical species, with diffusivity

$\gamma$

. The movement of the particle is caused by an asymmetric release of a chemical species, with diffusivity

![]() $\mathscr{D}$

, from the particle’s surface (see, e.g. figure 1). Our initial goal is to formulate a theoretical expression for the self-propulsion speed of the particle in the limits of small Péclet and Reynolds numbers. To reduce the complexity of the derivation, we assume that (i) the liquid–gas interface is flat, (ii) the effect of flow in the gas phase is negligible, (iii) the released chemical species is soluble in the bulk of the liquid layer, (iv) the liquid is at rest and contains no amount of the chemical species far from the particle, (v) the liquid is Newtonian with constant density and viscosity that are unaffected by the presence of the solute, (vi) the surface tension of the liquid varies linearly with the concentration of the chemical species, (vii) no velocity slip occurs on the wetted surface of the surfer due to tangential concentration gradients and (viii) the particle undergoes a pure translational motion along a straight line parallel to the interface.

$\mathscr{D}$

, from the particle’s surface (see, e.g. figure 1). Our initial goal is to formulate a theoretical expression for the self-propulsion speed of the particle in the limits of small Péclet and Reynolds numbers. To reduce the complexity of the derivation, we assume that (i) the liquid–gas interface is flat, (ii) the effect of flow in the gas phase is negligible, (iii) the released chemical species is soluble in the bulk of the liquid layer, (iv) the liquid is at rest and contains no amount of the chemical species far from the particle, (v) the liquid is Newtonian with constant density and viscosity that are unaffected by the presence of the solute, (vi) the surface tension of the liquid varies linearly with the concentration of the chemical species, (vii) no velocity slip occurs on the wetted surface of the surfer due to tangential concentration gradients and (viii) the particle undergoes a pure translational motion along a straight line parallel to the interface.

Let

![]() $\boldsymbol{r} = x \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + y \boldsymbol{e\!}_y + z \boldsymbol{e}_z$

be the position vector with

$\boldsymbol{r} = x \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + y \boldsymbol{e\!}_y + z \boldsymbol{e}_z$

be the position vector with

![]() $r = |\boldsymbol{r}|$

in the Cartesian coordinate system

$r = |\boldsymbol{r}|$

in the Cartesian coordinate system

![]() $(x,y,z)$

, with the unit vectors

$(x,y,z)$

, with the unit vectors

![]() $\boldsymbol{e\!}_x$

,

$\boldsymbol{e\!}_x$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{e\!}_y$

and

$\boldsymbol{e\!}_y$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{e}_z$

such that

$\boldsymbol{e}_z$

such that

![]() $\boldsymbol{e\!}_x$

is aligned with the propulsion direction of the surfer,

$\boldsymbol{e\!}_x$

is aligned with the propulsion direction of the surfer,

![]() $\boldsymbol{e}_z$

is normal to the interface pointing away from the liquid and the origin of the coordinates coincides with the geometrical centre of the three-phase contact line denoted by

$\boldsymbol{e}_z$

is normal to the interface pointing away from the liquid and the origin of the coordinates coincides with the geometrical centre of the three-phase contact line denoted by

![]() $l_{\!p}$

(see figure 1). Also, let

$l_{\!p}$

(see figure 1). Also, let

![]() $c$

,

$c$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{u} = u_x \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + u_y \boldsymbol{e\!}_y + u_z \boldsymbol{e}_z$

and

$\boldsymbol{u} = u_x \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + u_y \boldsymbol{e\!}_y + u_z \boldsymbol{e}_z$

and

![]() $p$

, represent, respectively, the dimensionless, steady-state concentration field of the chemical species and the velocity and pressure fields of the liquid. With these definitions and the above-mentioned assumptions, the equations that govern the distributions of

$p$

, represent, respectively, the dimensionless, steady-state concentration field of the chemical species and the velocity and pressure fields of the liquid. With these definitions and the above-mentioned assumptions, the equations that govern the distributions of

![]() $c$

,

$c$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

and

$\boldsymbol{u}$

and

![]() $p$

in a coordinate system attached to the particle are (see, e.g. Masoud & Stone Reference Masoud and Stone2019, p. 37)

$p$

in a coordinate system attached to the particle are (see, e.g. Masoud & Stone Reference Masoud and Stone2019, p. 37)

with the boundary conditions

and

with the boundary conditions

Here,

![]() $S_i$

,

$S_i$

,

![]() $S_{\!p}$

,

$S_{\!p}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\sigma } = - p \boldsymbol{I} + \mu [ \boldsymbol{\nabla } \boldsymbol{u} + ( \boldsymbol{\nabla } \boldsymbol{u} )^T ]$

,

$\boldsymbol{\sigma } = - p \boldsymbol{I} + \mu [ \boldsymbol{\nabla } \boldsymbol{u} + ( \boldsymbol{\nabla } \boldsymbol{u} )^T ]$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{I}$

,

$\boldsymbol{I}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}$

and

$\boldsymbol{n}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i}$

denote the liquid–gas interface, the wet surface of the surfer, the stress tensor, the identity tensor, the unit normal vector and the surface gradient operator taking effect along

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i}$

denote the liquid–gas interface, the wet surface of the surfer, the stress tensor, the identity tensor, the unit normal vector and the surface gradient operator taking effect along

![]() $S_i$

, respectively. Also,

$S_i$

, respectively. Also,

where

![]() $\ell$

is the radius of the smallest sphere that encloses the surfer,

$\ell$

is the radius of the smallest sphere that encloses the surfer,

![]() $\underset {\tilde {}}{\boldsymbol{U}} = \underset {\tilde {}}{U} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x$

is the (dimensional) propulsion velocity of the surfer and

$\underset {\tilde {}}{\boldsymbol{U}} = \underset {\tilde {}}{U} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x$

is the (dimensional) propulsion velocity of the surfer and

![]() $U^\star$

represents the value of

$U^\star$

represents the value of

![]() $\underset {\tilde {}}{U}$

in the absence of advective effects (i.e. when the concentration and flow fields are governed by diffusion and Stokes equations, respectively). Note that we intentionally refrained from specifying a boundary condition for

$\underset {\tilde {}}{U}$

in the absence of advective effects (i.e. when the concentration and flow fields are governed by diffusion and Stokes equations, respectively). Note that we intentionally refrained from specifying a boundary condition for

![]() $c$

on

$c$

on

![]() $S_{\!p}$

in order to avoid constraining the problem to a particular release mechanism.

$S_{\!p}$

in order to avoid constraining the problem to a particular release mechanism.

2.2. An integral formulation for the propulsion speed

Consider the auxiliary problem of Stokes flow around the same surfer travelling with velocity

![]() ${\underset {\tilde {}}{U}}{}_{\!a} = {\underset {\tilde {}}{U}}{}_{\!a} {\boldsymbol{e}}_x$

(where

${\underset {\tilde {}}{U}}{}_{\!a} = {\underset {\tilde {}}{U}}{}_{\!a} {\boldsymbol{e}}_x$

(where

![]() ${\underset {\tilde {}}{U}}{}_{\!a} = |{\underset {\tilde {}}{U}}{}_{\!a}|$

) when no surface-tension gradients (i.e. Marangoni stresses) are present. The (dimensionless) velocity and the stress fields, in this case, follow

${\underset {\tilde {}}{U}}{}_{\!a} = |{\underset {\tilde {}}{U}}{}_{\!a}|$

) when no surface-tension gradients (i.e. Marangoni stresses) are present. The (dimensionless) velocity and the stress fields, in this case, follow

with the boundary conditions

According to Lamb’s general solution of the Stokes equations (Lamb Reference Lamb1932, see also Brenner & Cox Reference Brenner and Cox1963), far from the surfer,

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_a$

behaves as

$\boldsymbol{u}_a$

behaves as

where

Next, apply the reciprocal theorem between the velocity–stress pairs

![]() $ ( \boldsymbol{u} , \boldsymbol{\sigma } )$

and

$ ( \boldsymbol{u} , \boldsymbol{\sigma } )$

and

![]() $ ( \boldsymbol{u}_a , \boldsymbol{\sigma }_{\!a} )$

(see, e.g. Masoud & Stone Reference Masoud and Stone2019, p. 14) to arrive at

$ ( \boldsymbol{u}_a , \boldsymbol{\sigma }_{\!a} )$

(see, e.g. Masoud & Stone Reference Masoud and Stone2019, p. 14) to arrive at

where

![]() $V$

and

$V$

and

![]() $S = S_i + S_{\!p} + S_\infty$

represent the volume and outer surface of the entire liquid domain, respectively. The integrals over

$S = S_i + S_{\!p} + S_\infty$

represent the volume and outer surface of the entire liquid domain, respectively. The integrals over

![]() $S_\infty$

(the bounding surfaces at very large distances) are zero since the velocities decay at least as fast as

$S_\infty$

(the bounding surfaces at very large distances) are zero since the velocities decay at least as fast as

![]() $1 / r$

. Hence, we have

$1 / r$

. Hence, we have

\begin{align} & \int _{S_i} \boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\sigma } \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}_a \; {\textrm {d}S} + \int _{S_{\!p}} \boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\sigma } \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}_a \; {\textrm {d}S}- \int _{S_i} \boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\sigma }_{\!a} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; {\textrm {d}S} \notag \\ & -\! \int _{S_{\!p}} \boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\sigma }_{\!a} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; {\textrm {d}S}= \textit{Re} \int _V\! \left ( \mathscr{U} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x - \boldsymbol{u} \right ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla } \boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}_a \; \textrm {d}V. \end{align}

\begin{align} & \int _{S_i} \boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\sigma } \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}_a \; {\textrm {d}S} + \int _{S_{\!p}} \boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\sigma } \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}_a \; {\textrm {d}S}- \int _{S_i} \boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\sigma }_{\!a} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; {\textrm {d}S} \notag \\ & -\! \int _{S_{\!p}} \boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\sigma }_{\!a} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; {\textrm {d}S}= \textit{Re} \int _V\! \left ( \mathscr{U} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x - \boldsymbol{u} \right ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla } \boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}_a \; \textrm {d}V. \end{align}

From the force balance on the surfer and the boundary conditions described by (2.2c )–(2.2), (2.1b ) and (2.1c ), we infer

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{t}$

is the unit vector tangent to

$\boldsymbol{t}$

is the unit vector tangent to

![]() $S_i$

and normal to

$S_i$

and normal to

![]() $l_{\!p}$

, and

$l_{\!p}$

, and

![]() $F_{\!a}$

is non-dimensionalised by

$F_{\!a}$

is non-dimensionalised by

![]() $\mu {\underset {\tilde {}}{U}}{}_a \ell$

. Therefore, we can write

$\mu {\underset {\tilde {}}{U}}{}_a \ell$

. Therefore, we can write

which leads to

The above integral relation for the propulsion speed can be expressed alternatively as

\begin{align} \mathscr{U} &= -\! \int _{S_i}\! \left ( \gamma - \gamma _0 \right ) \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \; {\textrm {d}S} \notag \\ &\quad+ \textit{Re}\! \left [ \int _V \boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; \textrm {d}V - \mathscr{U} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\int _V \boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; \textrm {d}V \right ]\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \mathscr{U} &= -\! \int _{S_i}\! \left ( \gamma - \gamma _0 \right ) \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \; {\textrm {d}S} \notag \\ &\quad+ \textit{Re}\! \left [ \int _V \boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; \textrm {d}V - \mathscr{U} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\int _V \boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; \textrm {d}V \right ]\!, \end{align}

given that

and that

2.3. Singular perturbation expansions of the velocity and concentration fields

Suppose

![]() $\textit{Pe} \ll 1$

and

$\textit{Pe} \ll 1$

and

![]() $\textit{Re} \ll 1$

, and let

$\textit{Re} \ll 1$

, and let

where

![]() $\gamma _0$

is a non-dimensional constant and

$\gamma _0$

is a non-dimensional constant and

![]() $\dot {m}^\star$

is the release rate of the chemical species when the concentration field is governed solely by diffusion. Here,

$\dot {m}^\star$

is the release rate of the chemical species when the concentration field is governed solely by diffusion. Here,

![]() $\gamma$

and

$\gamma$

and

![]() $c$

are made dimensionless by

$c$

are made dimensionless by

![]() $\mu U^\star$

and

$\mu U^\star$

and

![]() $\dot {m}^\star / 2 \pi \mathscr{D} \ell$

, respectively. To evaluate (2.10c

) in the limits of small Péclet and Reynolds numbers, we proceed with perturbation expansions of

$\dot {m}^\star / 2 \pi \mathscr{D} \ell$

, respectively. To evaluate (2.10c

) in the limits of small Péclet and Reynolds numbers, we proceed with perturbation expansions of

![]() $c$

and

$c$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

in terms of

$\boldsymbol{u}$

in terms of

![]() $\textit{Pe}$

and

$\textit{Pe}$

and

![]() $\textit{Re}$

. It is widely known that regular expansions fail to deliver satisfactory approximations due to the far-field behaviour of the concentration and velocity distributions in the purely diffusive and purely viscous limits. Therefore, we adopt the singular perturbation technique, which involves distinct expansions for regions in proximity to and distant from the particle, referred to as the inner and outer regions, respectively (see, e.g. Lagerstrom & Cole Reference Lagerstrom and Cole1955; Kaplun Reference Kaplun1957; Kaplun & Lagerstrom Reference Kaplun and Lagerstrom1957; Proudman & Pearson Reference Proudman and Pearson1957; Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke1964; Hinch Reference Hinch1991; Leal Reference Leal2007). The inner and outer expansions are asymptotically matched in an intermediate region, where both of them are applicable. As demonstrated by Lovalenti & Brady (Reference Lovalenti and Brady1993), these regional expansions can be merged (while carefully avoiding duplication of overlapping regions) to form approximations that remain uniformly valid across the domain

$\textit{Re}$

. It is widely known that regular expansions fail to deliver satisfactory approximations due to the far-field behaviour of the concentration and velocity distributions in the purely diffusive and purely viscous limits. Therefore, we adopt the singular perturbation technique, which involves distinct expansions for regions in proximity to and distant from the particle, referred to as the inner and outer regions, respectively (see, e.g. Lagerstrom & Cole Reference Lagerstrom and Cole1955; Kaplun Reference Kaplun1957; Kaplun & Lagerstrom Reference Kaplun and Lagerstrom1957; Proudman & Pearson Reference Proudman and Pearson1957; Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke1964; Hinch Reference Hinch1991; Leal Reference Leal2007). The inner and outer expansions are asymptotically matched in an intermediate region, where both of them are applicable. As demonstrated by Lovalenti & Brady (Reference Lovalenti and Brady1993), these regional expansions can be merged (while carefully avoiding duplication of overlapping regions) to form approximations that remain uniformly valid across the domain

![]() $V$

(see also Dehdashti & Masoud Reference Dehdashti and Masoud2020). Following this approach,

$V$

(see also Dehdashti & Masoud Reference Dehdashti and Masoud2020). Following this approach,

![]() $c$

and

$c$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

can be expressed as

$\boldsymbol{u}$

can be expressed as

\begin{align} c &= \underbrace {c^{(0,0)}}_{\substack {\text{zeroth-order}\\\text{solution}}} + \underbrace {\textit{Pe} \, c^{(1,0)} }_{\substack {\text{First-order inner}\\\text{approximation}}} + \underbrace {\textit{Pe} \, \check {c}^{(1,0)}}_{\substack {\text{First-order outer}\\\text{approximation}}} - \underbrace {\left ( c^{(0,0)}_\infty + \textit{Pe} \, c^{(1,0)}_\infty \right )}_{\text{Overlapping terms}} \notag \\ &\quad+ \mathscr{O}\big(\textit{Pe}^2 \ln \textit{Pe}\big) + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe} \, \textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re}), \end{align}

\begin{align} c &= \underbrace {c^{(0,0)}}_{\substack {\text{zeroth-order}\\\text{solution}}} + \underbrace {\textit{Pe} \, c^{(1,0)} }_{\substack {\text{First-order inner}\\\text{approximation}}} + \underbrace {\textit{Pe} \, \check {c}^{(1,0)}}_{\substack {\text{First-order outer}\\\text{approximation}}} - \underbrace {\left ( c^{(0,0)}_\infty + \textit{Pe} \, c^{(1,0)}_\infty \right )}_{\text{Overlapping terms}} \notag \\ &\quad+ \mathscr{O}\big(\textit{Pe}^2 \ln \textit{Pe}\big) + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe} \, \textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re}), \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{u} &= \underbrace {\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}}_{\substack {\text{zeroth-order}\\\text{solution}}} + \underbrace { \textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re} \, \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,1)} + \textit{Re} \, \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,2)}}_{\substack {\text{First- and second-order}\\\text{inner approximations}}} + \underbrace {\textit{Re} \, {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)}}_{\substack {\text{First-order outer}\\\text{approximation}}} \notag \\ &\quad- \underbrace {\left ( \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}_\infty + \textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re} \, \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,1)}_\infty + \textit{Re} \, \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,2)}_\infty \right )}_{\text{Overlapping terms}} + \, \mathscr{O}\big(\textit{Re}^2 \ln \textit{Re}\big) + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe} \ln \textit{Pe}), \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{u} &= \underbrace {\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}}_{\substack {\text{zeroth-order}\\\text{solution}}} + \underbrace { \textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re} \, \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,1)} + \textit{Re} \, \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,2)}}_{\substack {\text{First- and second-order}\\\text{inner approximations}}} + \underbrace {\textit{Re} \, {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)}}_{\substack {\text{First-order outer}\\\text{approximation}}} \notag \\ &\quad- \underbrace {\left ( \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}_\infty + \textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re} \, \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,1)}_\infty + \textit{Re} \, \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,2)}_\infty \right )}_{\text{Overlapping terms}} + \, \mathscr{O}\big(\textit{Re}^2 \ln \textit{Re}\big) + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe} \ln \textit{Pe}), \end{align}

where the infinity subscript denotes the leading-order contributions to the corresponding terms in the limit that

![]() $r \to \infty$

. Also,

$r \to \infty$

. Also,

![]() $\vee$

and

$\vee$

and

![]() $\sim$

overbars denote that the concentration and velocity fields, as well as the

$\sim$

overbars denote that the concentration and velocity fields, as well as the

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }$

and

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }$

and

![]() ${\nabla} ^2$

operators in the following equations, are written in terms of the stretched (rescaled) position vectors

${\nabla} ^2$

operators in the following equations, are written in terms of the stretched (rescaled) position vectors

![]() $\check {\boldsymbol{r}} = \textit{Pe} \, \boldsymbol{r}$

and

$\check {\boldsymbol{r}} = \textit{Pe} \, \boldsymbol{r}$

and

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{r}} = \textit{Re} \, \boldsymbol{r}$

, respectively. Note that the coefficients of the expansion terms in (2.14) and (2.15) are not strictly required to be simple powers of the perturbation parameters (i.e.

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{r}} = \textit{Re} \, \boldsymbol{r}$

, respectively. Note that the coefficients of the expansion terms in (2.14) and (2.15) are not strictly required to be simple powers of the perturbation parameters (i.e.

![]() $\textit{Re}$

and

$\textit{Re}$

and

![]() $\textit{Pe}$

). Instead, they are determined by the boundary and matching conditions, as will become evident shortly.

$\textit{Pe}$

). Instead, they are determined by the boundary and matching conditions, as will become evident shortly.

2.3.1. Zeroth- and first-order approximations for the concentration field

Substituting the zeroth-order term along with the inner and outer expansions from (2.14) into (2.1) and equating like powers of

![]() $\textit{Pe}$

, we arrive at the following boundary value problems:

$\textit{Pe}$

, we arrive at the following boundary value problems:

Following Brenner (Reference Brenner1963), the asymptotic solutions to (2.15)–(2.17) in the limits of

![]() $r \gg 1$

and

$r \gg 1$

and

![]() $\check {r} \ll 1$

are given by

$\check {r} \ll 1$

are given by

A key parameter for assessing the propulsion efficiency of the surfer (defined either as the distance travelled per unit mass of ‘fuel’ released or as the speed achieved per unit rate of fuel consumed) is the total release rate of the chemical species, expressed as

where a tilde underbar indicates dimensional variables and operators. Adopting an approach akin to that of Brenner (Reference Brenner1963) (see also Dehdashti & Masoud Reference Dehdashti and Masoud2020), it can be shown that the Sherwood number (denoted by

![]() $\textit{Sh}$

), takes the form

$\textit{Sh}$

), takes the form

with

valid for the special case where the wet surface of the surfer is divided into an active region,

![]() $S_{\!p}^{a}$

, maintained at a uniform (dimensional) concentration

$S_{\!p}^{a}$

, maintained at a uniform (dimensional) concentration

![]() ${\underset{\tilde{}}{c}}{}_s$

, and an inactive region,

${\underset{\tilde{}}{c}}{}_s$

, and an inactive region,

![]() $S_{\!p}^{ia}$

, on which a no-flux condition (

$S_{\!p}^{ia}$

, on which a no-flux condition (

![]() $\boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} c = 0$

) is imposed (see, e.g. Masoud & Rothstein Reference Masoud and Rothstein2022).

$\boldsymbol{n} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} c = 0$

) is imposed (see, e.g. Masoud & Rothstein Reference Masoud and Rothstein2022).

2.3.2. Zeroth- and first-order outer approximations for the velocity field

Similarly, substituting the expansion (2.15) into the Navier–Stokes equations (2.2) and collecting terms of equal powers in

![]() $\textit{Re}$

yield the following governing equations for the leading-order inner and outer velocity fields:

$\textit{Re}$

yield the following governing equations for the leading-order inner and outer velocity fields:

\begin{align} &u^{(0,0)}_z = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad \left ( \frac {\partial u^{(0,0)}_x}{\partial z} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + \frac {\partial u^{(0,0)}_y}{\partial z} \boldsymbol{e\!}_y \right ) = \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \gamma ^{(0,0)} \quad \text{ for } \quad \boldsymbol{r} \in S_i, \end{align}

\begin{align} &u^{(0,0)}_z = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad \left ( \frac {\partial u^{(0,0)}_x}{\partial z} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + \frac {\partial u^{(0,0)}_y}{\partial z} \boldsymbol{e\!}_y \right ) = \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \gamma ^{(0,0)} \quad \text{ for } \quad \boldsymbol{r} \in S_i, \end{align}

\begin{align} &\tilde {u}^{(0,1)}_z = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad \left ( \frac {\partial \tilde {u}^{(0,1)}_x}{\partial \tilde {z}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + \frac {\partial \tilde {u}^{(0,1)}_y}{\partial \tilde {z}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_y \right ) = \tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }}_{\!S_i} \tilde {\gamma }_\infty ^{(0,0)} \quad \text{ for } \quad \tilde {\boldsymbol{r}} \in S_i. \end{align}

\begin{align} &\tilde {u}^{(0,1)}_z = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad \left ( \frac {\partial \tilde {u}^{(0,1)}_x}{\partial \tilde {z}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + \frac {\partial \tilde {u}^{(0,1)}_y}{\partial \tilde {z}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_y \right ) = \tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }}_{\!S_i} \tilde {\gamma }_\infty ^{(0,0)} \quad \text{ for } \quad \tilde {\boldsymbol{r}} \in S_i. \end{align}

Note that the boundary condition at the interface in (2.26) also ensures that

Let

![]() $_{-1} \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}$

be the solution to (2.25) correct to

$_{-1} \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}$

be the solution to (2.25) correct to

![]() $\mathscr{O}(r^{-1})$

. This velocity field corresponds to the monopolar contribution of the zeroth-order concentration field, denoted henceforth by

$\mathscr{O}(r^{-1})$

. This velocity field corresponds to the monopolar contribution of the zeroth-order concentration field, denoted henceforth by

![]() $_{-1} c^{(0,0)} = 1 / r$

(see (2.19)). As described below,

$_{-1} c^{(0,0)} = 1 / r$

(see (2.19)). As described below,

![]() ${_{-1} \boldsymbol{u}}^{(0,0)}$

can be calculated by applying the Fourier transform in the

${_{-1} \boldsymbol{u}}^{(0,0)}$

can be calculated by applying the Fourier transform in the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane.

$y$

plane.

We begin by taking the Fourier transform of

![]() $_{-1} c^{(0,0)}$

:

$_{-1} c^{(0,0)}$

:

\begin{align} \mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \big \{ _{-1} c^{(0,0)}\big \} = _{-1} {\widehat {c}} ^{(0,0)} &= \int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _{-\infty }^\infty \frac {\exp \big [- i \big ( k_x x + k_y y \big ) \big ]}{\sqrt {x^2 + y^2 + z^2}} \; \textrm {d}x \, \textrm {d}y \notag \\[5pt] &= 2 \pi \int _0^\infty \frac {J_0(k \rho )}{\sqrt {\rho ^2 + z^2}} \, \rho \; \textrm {d}\rho = 2 \pi \frac {\exp ( k z )}{k}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \big \{ _{-1} c^{(0,0)}\big \} = _{-1} {\widehat {c}} ^{(0,0)} &= \int _{-\infty }^\infty \int _{-\infty }^\infty \frac {\exp \big [- i \big ( k_x x + k_y y \big ) \big ]}{\sqrt {x^2 + y^2 + z^2}} \; \textrm {d}x \, \textrm {d}y \notag \\[5pt] &= 2 \pi \int _0^\infty \frac {J_0(k \rho )}{\sqrt {\rho ^2 + z^2}} \, \rho \; \textrm {d}\rho = 2 \pi \frac {\exp ( k z )}{k}, \end{align}

where

![]() $i^2 = -1$

,

$i^2 = -1$

,

![]() $k = |\boldsymbol{k}|$

with

$k = |\boldsymbol{k}|$

with

![]() $\boldsymbol{k} = ( k_x, k_y )$

being the in-plane wave vector,

$\boldsymbol{k} = ( k_x, k_y )$

being the in-plane wave vector,

![]() $J_0$

the zeroth-order Bessel function of the first kind and

$J_0$

the zeroth-order Bessel function of the first kind and

![]() $\rho = \sqrt {x^2 + y^2}$

(see Gradshteyn & Ryzhik Reference Gradshteyn and Ryzhik2007; Baddour Reference Baddour2011, 6.565-2). Note that

$\rho = \sqrt {x^2 + y^2}$

(see Gradshteyn & Ryzhik Reference Gradshteyn and Ryzhik2007; Baddour Reference Baddour2011, 6.565-2). Note that

![]() $z \lt 0$

in the liquid phase beneath the interface, as illustrated in figure 1. Combining the result from (2.28) with the derivation presented in the supplementary material of Masoud & Shelley (Reference Masoud and Shelley2014) for Marangoni-driven Stokes flow, we obtain

$z \lt 0$

in the liquid phase beneath the interface, as illustrated in figure 1. Combining the result from (2.28) with the derivation presented in the supplementary material of Masoud & Shelley (Reference Masoud and Shelley2014) for Marangoni-driven Stokes flow, we obtain

Taking the inverse Fourier transform of (2.29), we then find (see again, Gradshteyn & Ryzhik Reference Gradshteyn and Ryzhik2007; Baddour Reference Baddour2011, 6.611-1,6.621-4)

\begin{align} &{_{-1}\boldsymbol{u}}^{(0,0)} \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{4 \pi \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right )^{-1} = - 2 \pi \, \mathfrak{F}^{-1}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \exp ( k z ) \left [ \frac {i \boldsymbol{k}}{k^2} \left ( 1 + k z \right ) + z \, \boldsymbol{e}_z \right ] \right \} \notag \\[5pt] &\,= - 2 \pi \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} \, \mathfrak{F}^{-1}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \exp ( k z ) \left ( \frac {1 + k z}{k^2} \right ) \right \} - 2 \pi \, \mathfrak{F}^{-1}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \exp ( k z ) z \right \} \boldsymbol{e}_z \notag \\[5pt] &\,= - \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} \int _0^\infty \frac {\exp ( k z ) \left ( 1 + k z \right ) }{k^2} J_0 ( k \rho ) \, k \; \textrm {d}k - z \int _0^\infty \exp ( k z ) \, J_0 ( k \rho ) \, k \; \textrm {d}k \, \boldsymbol{e}_z \notag \\[5pt] &\,= - \int _0^\infty \frac {\exp ( k z ) \left ( 1 + k z \right ) }{k^2} \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} J_0 ( k \rho ) \, k \; \textrm {d}k + \frac {z^2}{r^3} \, \boldsymbol{e}_z \notag \\[5pt] &\,= \int _0^\infty \exp ( k z ) \left ( 1 + k z \right ) J_1 ( k \rho )\; \textrm {d}k \, \boldsymbol{e\!}_\rho + \frac {z^2}{r^3} \boldsymbol{e}_z \notag \\[5pt] &\,= \left [ \frac {1}{\rho } \left ( 1 + \frac {z}{r} \right ) + \frac {\rho z}{r^3} \right ] \boldsymbol{e\!}_\rho + \frac {z^2}{r^3} \, \boldsymbol{e}_z = \frac {1}{r} \left [ \left ( 1 + 2 \cos \theta \right ) \boldsymbol{e}_r + \frac {\sin \theta \cos \theta }{ 1 - \cos \theta } \boldsymbol{e}_\theta \right ]\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} &{_{-1}\boldsymbol{u}}^{(0,0)} \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{4 \pi \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right )^{-1} = - 2 \pi \, \mathfrak{F}^{-1}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \exp ( k z ) \left [ \frac {i \boldsymbol{k}}{k^2} \left ( 1 + k z \right ) + z \, \boldsymbol{e}_z \right ] \right \} \notag \\[5pt] &\,= - 2 \pi \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} \, \mathfrak{F}^{-1}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \exp ( k z ) \left ( \frac {1 + k z}{k^2} \right ) \right \} - 2 \pi \, \mathfrak{F}^{-1}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \exp ( k z ) z \right \} \boldsymbol{e}_z \notag \\[5pt] &\,= - \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} \int _0^\infty \frac {\exp ( k z ) \left ( 1 + k z \right ) }{k^2} J_0 ( k \rho ) \, k \; \textrm {d}k - z \int _0^\infty \exp ( k z ) \, J_0 ( k \rho ) \, k \; \textrm {d}k \, \boldsymbol{e}_z \notag \\[5pt] &\,= - \int _0^\infty \frac {\exp ( k z ) \left ( 1 + k z \right ) }{k^2} \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} J_0 ( k \rho ) \, k \; \textrm {d}k + \frac {z^2}{r^3} \, \boldsymbol{e}_z \notag \\[5pt] &\,= \int _0^\infty \exp ( k z ) \left ( 1 + k z \right ) J_1 ( k \rho )\; \textrm {d}k \, \boldsymbol{e\!}_\rho + \frac {z^2}{r^3} \boldsymbol{e}_z \notag \\[5pt] &\,= \left [ \frac {1}{\rho } \left ( 1 + \frac {z}{r} \right ) + \frac {\rho z}{r^3} \right ] \boldsymbol{e\!}_\rho + \frac {z^2}{r^3} \, \boldsymbol{e}_z = \frac {1}{r} \left [ \left ( 1 + 2 \cos \theta \right ) \boldsymbol{e}_r + \frac {\sin \theta \cos \theta }{ 1 - \cos \theta } \boldsymbol{e}_\theta \right ]\!, \end{align}

where

and

![]() $J_1$

is the first-order Bessel function of the first kind. Here, we have expressed the velocity field in both cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems,

$J_1$

is the first-order Bessel function of the first kind. Here, we have expressed the velocity field in both cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems,

![]() $(\rho , \varphi , z)$

and

$(\rho , \varphi , z)$

and

![]() $(r , \theta , \varphi )$

, respectively. The associated unit vectors

$(r , \theta , \varphi )$

, respectively. The associated unit vectors

![]() $(\boldsymbol{e\!}_\rho , \boldsymbol{e}_\varphi , \boldsymbol{e}_z)$

and

$(\boldsymbol{e\!}_\rho , \boldsymbol{e}_\varphi , \boldsymbol{e}_z)$

and

![]() $(\boldsymbol{e}_r, \boldsymbol{e}_\theta , \boldsymbol{e}_\varphi )$

are related to the Cartesian basis via

$(\boldsymbol{e}_r, \boldsymbol{e}_\theta , \boldsymbol{e}_\varphi )$

are related to the Cartesian basis via

Hence, the zeroth-order velocity field admits the following asymptotic representation:

which agrees with the expression reported by Würger (Reference Würger2014).

Next, we seek the solution of (2.24) for

![]() ${\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)}$

. As will become clear shortly, it is advantageous to again work in the Fourier space. Hence, following Masoud & Shelley (Reference Masoud and Shelley2014), we rewrite the governing equations as

${\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)}$

. As will become clear shortly, it is advantageous to again work in the Fourier space. Hence, following Masoud & Shelley (Reference Masoud and Shelley2014), we rewrite the governing equations as

\begin{align} \left ( \frac {\partial ^2 }{\partial \tilde {z}^2} - \tilde {k}^{2} + \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \right ) \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_z &= \frac {\partial \widehat {\tilde {p}}^{(0,1)}}{\partial \tilde {z}}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \left ( \frac {\partial ^2 }{\partial \tilde {z}^2} - \tilde {k}^{2} + \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \right ) \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_z &= \frac {\partial \widehat {\tilde {p}}^{(0,1)}}{\partial \tilde {z}}, \end{align}

subject to the boundary conditions

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_x}{\partial \tilde {z}} \bigg |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + \frac {\partial \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_y}{\partial \tilde {z}} \bigg |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_y &= -\! \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_x}{\partial \tilde {z}} \bigg |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + \frac {\partial \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_y}{\partial \tilde {z}} \bigg |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_y &= -\! \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k}}. \end{align}

The solutions to this coupled system can be expressed in terms of the interfacial velocity,

![]() $\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)} = \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_x \big |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + \widehat {\tilde {u}}\big |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_y$

:

$\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)} = \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_x \big |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + \widehat {\tilde {u}}\big |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_y$

:

\begin{align} \widehat {\tilde {p}}^{(0,1)} &= \frac {\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k}} \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)}}{\sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} - \tilde {k}} \exp ( \tilde {k} \tilde {z} ), \end{align}

\begin{align} \widehat {\tilde {p}}^{(0,1)} &= \frac {\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k}} \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)}}{\sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} - \tilde {k}} \exp ( \tilde {k} \tilde {z} ), \end{align}

\begin{align} \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_z &= \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)}}{\sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} - \tilde {k}} \left [ \exp ( \tilde {k} z ) - \exp \!\left ( \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} \, \tilde {z} \right ) \right ]\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_z &= \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)}}{\sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} - \tilde {k}} \left [ \exp ( \tilde {k} z ) - \exp \!\left ( \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} \, \tilde {z} \right ) \right ]\!, \end{align}

Taking the derivative of the in-plane velocity and evaluating it at

![]() $\tilde {z} = 0$

, we obtain

$\tilde {z} = 0$

, we obtain

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_x}{\partial \tilde {z}} \bigg |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + \frac {\partial \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_y}{\partial \tilde {z}} \bigg |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_y &= \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} } \left ( \boldsymbol{I} + \frac {\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k} \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}} \right ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)} \notag \\[5pt] &= -\! \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_x}{\partial \tilde {z}} \bigg |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x + \frac {\partial \widehat {\tilde {u}}^{(0,1)}_y}{\partial \tilde {z}} \bigg |_{\tilde {z}=0} \boldsymbol{e\!}_y &= \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} } \left ( \boldsymbol{I} + \frac {\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k} \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}} \right ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)} \notag \\[5pt] &= -\! \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k}}. \end{align}

Solving for

![]() $\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)}$

, we find

$\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)}$

, we find

\begin{align} \widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)} &= \left \{ \frac {1}{\sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}} \left [ \boldsymbol{I} - \frac {\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k} \left ( \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} + \tilde {k} \right )} \right ] \right \} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\left [\! -\! \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{k} \right ] \notag \\[5pt] &= - \!\left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \frac {1}{\sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} + \tilde {k}} \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}_{\!s}^{(0,1)} &= \left \{ \frac {1}{\sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}} \left [ \boldsymbol{I} - \frac {\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k} \left ( \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} + \tilde {k} \right )} \right ] \right \} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\left [\! -\! \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{k} \right ] \notag \\[5pt] &= - \!\left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \frac {1}{\sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} + \tilde {k}} \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k}}. \end{align}

Finally, substituting back into (2.45) and (2.46), the full velocity field is given by

\begin{align} {\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}^{(0,1)} = - \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \frac {1}{\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} &\Bigg \{ i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \left [ \exp ( \tilde {k} \tilde {z} ) - \sqrt { 1 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} / \tilde {k}^2 } \exp \! \left ( \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} \, \tilde {z} \right ) \right ] \notag \\ & + \tilde {k} \left [ \exp ( \tilde {k} \tilde {z} ) - \exp \! \left ( \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} \, \tilde {z} \right ) \right ] \boldsymbol{e}_z \Bigg \}. \end{align}

\begin{align} {\widehat {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}^{(0,1)} = - \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \frac {1}{\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} &\Bigg \{ i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \left [ \exp ( \tilde {k} \tilde {z} ) - \sqrt { 1 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} / \tilde {k}^2 } \exp \! \left ( \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} \, \tilde {z} \right ) \right ] \notag \\ & + \tilde {k} \left [ \exp ( \tilde {k} \tilde {z} ) - \exp \! \left ( \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 - \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} \, \tilde {z} \right ) \right ] \boldsymbol{e}_z \Bigg \}. \end{align}

The conversion to real space for this velocity correction is not needed, as the subsequent integrals involving this velocity in the evaluation of the propulsion speed are performed in Fourier space.

2.4. Behaviour of the propulsion speed in the limits of low Péclet and Reynolds numbers

By substituting the auxiliary velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_a$

, along with the asymptotic expansions for the concentration and velocity fields, into (2.10c

), we obtain an asymptotic expression for the normalised propulsion speed of the surfer

$\boldsymbol{u}_a$

, along with the asymptotic expansions for the concentration and velocity fields, into (2.10c

), we obtain an asymptotic expression for the normalised propulsion speed of the surfer

\begin{align} \mathscr{U} &= \mathscr{U}^{(0,0)} + \textit{Pe} \ln \textit{Pe} \, \mathscr{U}^{(1,0)} + \textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re} \, \mathscr{U}^{(0,1)} + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe}) + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Re}) \notag \\ &= 1 - \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{32 \pi \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \left ( 2 \, \textit{Pe} \ln \textit{Pe} + \textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re} \right ) + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe}) + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Re}). \end{align}

\begin{align} \mathscr{U} &= \mathscr{U}^{(0,0)} + \textit{Pe} \ln \textit{Pe} \, \mathscr{U}^{(1,0)} + \textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re} \, \mathscr{U}^{(0,1)} + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe}) + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Re}) \notag \\ &= 1 - \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{32 \pi \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \left ( 2 \, \textit{Pe} \ln \textit{Pe} + \textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re} \right ) + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe}) + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Re}). \end{align}

In what follows, we outline the derivation of the leading-order correction terms that appear in (2.50).

2.4.1. Derivation of the leading-order

$\textit{Pe}$

correction

$\textit{Pe}$

correction

To isolate the leading-order correction due to

![]() $\textit{Pe}$

, we begin by setting

$\textit{Pe}$

, we begin by setting

![]() $\textit{Re} = 0$

, which reduces (2.10c

) to

$\textit{Re} = 0$

, which reduces (2.10c

) to

Next, we replace for

![]() $\gamma - \gamma _0$

from (2.13), (2.14), and (2.19)–(2.21) to arrive at

$\gamma - \gamma _0$

from (2.13), (2.14), and (2.19)–(2.21) to arrive at

\begin{align} \mathscr{U} = 1 + \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star \textit{Pe}}{2 \pi \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \, &\bigg [ \int _{S_i} c^{(1,0)} \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, {\textrm {d}S} \notag \\ &+ \int _{S_i} \left ( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \right ) \check {\boldsymbol{\nabla }}_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\check {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, \textrm {d}\check {S}\bigg ] + {\cdots} , \end{align}

\begin{align} \mathscr{U} = 1 + \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star \textit{Pe}}{2 \pi \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \, &\bigg [ \int _{S_i} c^{(1,0)} \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, {\textrm {d}S} \notag \\ &+ \int _{S_i} \left ( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \right ) \check {\boldsymbol{\nabla }}_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\check {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, \textrm {d}\check {S}\bigg ] + {\cdots} , \end{align}

where the ellipsis denotes terms of higher order in

![]() $\textit{Pe}$

beyond those explicitly retained, and the base speed

$\textit{Pe}$

beyond those explicitly retained, and the base speed

![]() $U^{\star }$

is determined by

$U^{\star }$

is determined by

Additionally, we use the relation

The integral involving

![]() $c^{(1,0)}$

can be split into two parts: one over the region between the closed contour

$c^{(1,0)}$

can be split into two parts: one over the region between the closed contour

![]() $l_{\!p}$

and a circle of radius 1 (denoted by

$l_{\!p}$

and a circle of radius 1 (denoted by

![]() $S_i^{(\rho \lt 1)}$

), and the other over the annular region extending from radius 1 to

$S_i^{(\rho \lt 1)}$

), and the other over the annular region extending from radius 1 to

![]() $\infty$

. Making this division and noting that

$\infty$

. Making this division and noting that

we reach

\begin{align} \int _{S_i} c^{(1,0)} \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, {\textrm {d}S} &= \int _{S_i^{(\rho \lt 1)}} c^{(1,0)} \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, {\textrm {d}S} \notag \\[5pt] &+ \int _1^\infty \int _0^{2\pi } \left [ c^{(1,0)} \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \right ]_{z = 0} \rho \; \textrm {d}\varphi \, \textrm {d}\rho \notag \\[5pt] &= \frac {1}{8} \int _1^{\infty } \frac {1}{\rho } \; \textrm {d}\rho + \mathscr{O}(1). \end{align}

\begin{align} \int _{S_i} c^{(1,0)} \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, {\textrm {d}S} &= \int _{S_i^{(\rho \lt 1)}} c^{(1,0)} \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, {\textrm {d}S} \notag \\[5pt] &+ \int _1^\infty \int _0^{2\pi } \left [ c^{(1,0)} \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \right ]_{z = 0} \rho \; \textrm {d}\varphi \, \textrm {d}\rho \notag \\[5pt] &= \frac {1}{8} \int _1^{\infty } \frac {1}{\rho } \; \textrm {d}\rho + \mathscr{O}(1). \end{align}

The near-field integral is

![]() $\mathscr{O}(1)$

because all quantities appearing in the integrand remain finite in the near-field region, and the integration domain itself is bounded. Similarly, the second integral on the right-hand side of (2.52) can be simplified to

$\mathscr{O}(1)$

because all quantities appearing in the integrand remain finite in the near-field region, and the integration domain itself is bounded. Similarly, the second integral on the right-hand side of (2.52) can be simplified to

\begin{align} &\int _{S_i} \big ( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \big ) \check {\boldsymbol{\nabla }}_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\check {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, \textrm {d}\check {S} \notag \\[5pt] &\,= \int _{S_i^{(\rho \lt 1)}} \big ( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \big ) \check {\boldsymbol{\nabla }}_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\check {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, \textrm {d}\check {S} \notag \\[5pt] &\,- \frac {1}{4 \pi } \int _{\textit{Pe}}^\infty\! \int _{0}^{2 \pi } \big ( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \big ) \frac {\cos \varphi }{\check {\rho }} \; \textrm {d}\varphi \, \textrm {d}\check {\rho } \notag \\[5pt] &\,= - \frac {1}{4 \pi } \int _{0}^\infty\! \int _{0}^{2 \pi } \big ( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \big ) \frac {\cos \varphi }{\check {\rho }} \; \textrm {d}\varphi \, \textrm {d}\check {\rho } + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe}) \notag \\[5pt] &\,= - \frac {1}{8} \int _1^{\infty } \frac {1}{\check {\rho }} \; \textrm {d}\check {\rho } + \mathscr{O}(1) = - \frac {1}{8} \int _{1 / \textit{Pe}}^{\infty } \frac {1}{\rho } \; \textrm {d}\rho + \mathscr{O}(1). \end{align}

\begin{align} &\int _{S_i} \big ( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \big ) \check {\boldsymbol{\nabla }}_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\check {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, \textrm {d}\check {S} \notag \\[5pt] &\,= \int _{S_i^{(\rho \lt 1)}} \big ( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \big ) \check {\boldsymbol{\nabla }}_{\!S_i} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\check {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \, \textrm {d}\check {S} \notag \\[5pt] &\,- \frac {1}{4 \pi } \int _{\textit{Pe}}^\infty\! \int _{0}^{2 \pi } \big ( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \big ) \frac {\cos \varphi }{\check {\rho }} \; \textrm {d}\varphi \, \textrm {d}\check {\rho } \notag \\[5pt] &\,= - \frac {1}{4 \pi } \int _{0}^\infty\! \int _{0}^{2 \pi } \big ( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \big ) \frac {\cos \varphi }{\check {\rho }} \; \textrm {d}\varphi \, \textrm {d}\check {\rho } + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe}) \notag \\[5pt] &\,= - \frac {1}{8} \int _1^{\infty } \frac {1}{\check {\rho }} \; \textrm {d}\check {\rho } + \mathscr{O}(1) = - \frac {1}{8} \int _{1 / \textit{Pe}}^{\infty } \frac {1}{\rho } \; \textrm {d}\rho + \mathscr{O}(1). \end{align}

Note that, when transitioning from the third to the fourth line, the lower limit of integration with respect to

![]() $\check {\rho }$

is extended from

$\check {\rho }$

is extended from

![]() $\textit{Pe}$

to

$\textit{Pe}$

to

![]() $0$

. The resulting contribution from the added interval

$0$

. The resulting contribution from the added interval

![]() $0 \leqslant \check {\rho } \lt \textit{Pe}$

(which also includes the integral in the second line) is

$0 \leqslant \check {\rho } \lt \textit{Pe}$

(which also includes the integral in the second line) is

![]() $\mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe})$

, since

$\mathscr{O}(\textit{Pe})$

, since

![]() $\left( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \right) \sim \mathscr{O}(\check {\rho })$

as

$\left( \check {c}^{(1,0)} - \check {c}^{(0,0)}_\infty - \check {c}^{(1,0)}_\infty \right) \sim \mathscr{O}(\check {\rho })$

as

![]() $\check {\rho } \to 0$

. Substituting (2.56) and (2.57) into (2.52), it follows that

$\check {\rho } \to 0$

. Substituting (2.56) and (2.57) into (2.52), it follows that

2.4.2. Derivation of the leading-order

$\textit{Re}$

correction

$\textit{Re}$

correction

Once again, we invoke the integral identity in (2.10c

), this time setting

![]() $\textit{Pe} = 0$

, which simplifies the expression to

$\textit{Pe} = 0$

, which simplifies the expression to

To evaluate the above integrals, we insert the velocity expansion from (2.15). Considering the far-field behaviour of

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}$

from (2.37), for the first integral, we find

$\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}$

from (2.37), for the first integral, we find

\begin{align} \int _V \boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; \textrm {d}V = \underbrace {\int _V \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)} \; \textrm {d}V}_{\mathscr{O}(1)} + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re}). \end{align}

\begin{align} \int _V \boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; \textrm {d}V = \underbrace {\int _V \boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)} \; \textrm {d}V}_{\mathscr{O}(1)} + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re}). \end{align}

Proceeding to the second integral, we obtain

\begin{align} \mathscr{U} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\int _V \boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; \textrm {d}V &= \underbrace { \int _V \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\left [ \boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)} - \boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}\boldsymbol{u}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}_\infty \right ] \textrm {d}V }_{\mathscr{O}(1)} \notag \\ &\,+\int _V \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V} + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re}), \end{align}

\begin{align} \mathscr{U} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\int _V \boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u} \; \textrm {d}V &= \underbrace { \int _V \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\left [ \boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {\boldsymbol{u}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)} - \boldsymbol{\nabla } \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}\boldsymbol{u}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}_\infty \right ] \textrm {d}V }_{\mathscr{O}(1)} \notag \\ &\,+\int _V \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V} + \mathscr{O}(\textit{Re} \ln \textit{Re}), \end{align}

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}_\infty = {_{-1} \boldsymbol{u}}^{(0,0)}$

. The second integral on the right-hand side of (2.61) can be recast as

$\boldsymbol{u}^{(0,0)}_\infty = {_{-1} \boldsymbol{u}}^{(0,0)}$

. The second integral on the right-hand side of (2.61) can be recast as

\begin{align} \int _V \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V} &= - \int _{\mathscr{V\,}^{(r \lt 1)}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V} \notag \\[5pt] &\,+ \int _{\mathscr{V}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V} \notag \\[5pt] &\,+ \underbrace {\int _{V^{(r \lt 1)}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V}}_{\mathscr{O}(1)}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \int _V \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V} &= - \int _{\mathscr{V\,}^{(r \lt 1)}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V} \notag \\[5pt] &\,+ \int _{\mathscr{V}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V} \notag \\[5pt] &\,+ \underbrace {\int _{V^{(r \lt 1)}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V}}_{\mathscr{O}(1)}, \end{align}

with

\begin{align} \mathscr{V} &= \{ \boldsymbol{r} \in \mathbb{R}^3 : z \leqslant 0 \}, \notag \\ \mathscr{V\,}^{(r \lt 1)} &= \{ \boldsymbol{r} \in \mathbb{R}^3 : z \leqslant 0, r \lt 1 \}, \notag \\ V^{(r \lt 1)} &= \{ \boldsymbol{r} \in V : r \lt 1 \}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \mathscr{V} &= \{ \boldsymbol{r} \in \mathbb{R}^3 : z \leqslant 0 \}, \notag \\ \mathscr{V\,}^{(r \lt 1)} &= \{ \boldsymbol{r} \in \mathbb{R}^3 : z \leqslant 0, r \lt 1 \}, \notag \\ V^{(r \lt 1)} &= \{ \boldsymbol{r} \in V : r \lt 1 \}. \end{align}

Recalling the matching condition (2.27), the first term on the right-hand side of (2.62) becomes

where, given that

the right-hand-side integral equals to

\begin{align} &\left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{16 \pi ^2 \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \int _0^1 \int _0^{2 \pi } \int _{\pi /2}^\pi \left ( 1 - 3 \sin ^2 \theta \cos ^2 \varphi \right ) \frac {\sin \theta + \sin 2 \theta }{r} \; \textrm {d}\theta \, \textrm {d}\varphi \, \textrm {d}r \notag \\[5pt] &\,= -\! \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{32 \pi \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \int _0^1 \frac {1}{r} \; \textrm {d}r = -\! \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{32 \pi \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \int _1^\infty \frac {1}{r} \; \textrm {d}r. \end{align}

\begin{align} &\left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{16 \pi ^2 \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \int _0^1 \int _0^{2 \pi } \int _{\pi /2}^\pi \left ( 1 - 3 \sin ^2 \theta \cos ^2 \varphi \right ) \frac {\sin \theta + \sin 2 \theta }{r} \; \textrm {d}\theta \, \textrm {d}\varphi \, \textrm {d}r \notag \\[5pt] &\,= -\! \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{32 \pi \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \int _0^1 \frac {1}{r} \; \textrm {d}r = -\! \left ( \frac {\alpha \dot {m}^\star }{32 \pi \mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell } \right ) \int _1^\infty \frac {1}{r} \; \textrm {d}r. \end{align}

To calculate the second integral in (2.62), we use the two-dimensional Fourier convolution theorem (see, e.g. Masoud & Stone Reference Masoud and Stone2019, p. 39) as follows:

\begin{align} &\int _{\mathscr{V}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V} = \int _{- \infty }^0 \int _{\mathbb{R}^2} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {\boldsymbol{\rho }} \, \textrm {d}\tilde {z} \notag \\[5pt] &\,= \frac {1}{\left ( 2 \pi \right )^2} \int _{- \infty }^0 \int _{\mathbb{R}^2} \big ( \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \big ) \mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \right \} \!(\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \big \{ {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \big \} (-\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}) \; \textrm {d}\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \, \textrm {d}\tilde {z}, \end{align}

\begin{align} &\int _{\mathscr{V}} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {V} = \int _{- \infty }^0 \int _{\mathbb{R}^2} \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }\tilde {\boldsymbol{\nabla }} \Big ( \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \Big ) \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {\boldsymbol{\rho }} \, \textrm {d}\tilde {z} \notag \\[5pt] &\,= \frac {1}{\left ( 2 \pi \right )^2} \int _{- \infty }^0 \int _{\mathbb{R}^2} \big ( \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \big ) \mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \right \} \!(\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \big \{ {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(0,1)} \big \} (-\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}) \; \textrm {d}\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \, \textrm {d}\tilde {z}, \end{align}

where

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} = \boldsymbol{k} / \textit{Re}$

and the Fourier transform of the auxiliary velocity field is given by

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} = \boldsymbol{k} / \textit{Re}$

and the Fourier transform of the auxiliary velocity field is given by

\begin{align} \mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \right \} = \exp (\tilde {k} \tilde {z}) \left \{ \left [ \boldsymbol{I} + \frac {\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{2 \tilde {k}^2} \big ( \tilde {k} \tilde {z} - 1 \big ) \right ] \boldsymbol{\cdot }\frac {\boldsymbol{e\!}_x}{\tilde {k}} - \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{e\!}_x}{2 \tilde {k}} \tilde {z} \, \boldsymbol{e}_z,\! \right \}\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} \mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \right \} = \exp (\tilde {k} \tilde {z}) \left \{ \left [ \boldsymbol{I} + \frac {\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{2 \tilde {k}^2} \big ( \tilde {k} \tilde {z} - 1 \big ) \right ] \boldsymbol{\cdot }\frac {\boldsymbol{e\!}_x}{\tilde {k}} - \frac {i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{e\!}_x}{2 \tilde {k}} \tilde {z} \, \boldsymbol{e}_z,\! \right \}\!. \end{align}

This expression can be derived by rewriting the

![]() $\mathscr{O}(r^{-1})$

component of the auxiliary velocity field via Bessel integral representations (see Gradshteyn & Ryzhik Reference Gradshteyn and Ryzhik2007; Baddour Reference Baddour2011, 6.611-1,6.621-4,6.623-3)

$\mathscr{O}(r^{-1})$

component of the auxiliary velocity field via Bessel integral representations (see Gradshteyn & Ryzhik Reference Gradshteyn and Ryzhik2007; Baddour Reference Baddour2011, 6.611-1,6.621-4,6.623-3)

\begin{align} \frac {{_{-1}\boldsymbol{u}}_a}{F_{\!a}} = \frac {1}{2 \pi } \Bigg [ &\int _0^\infty \exp ( k z ) J_0 ( k \rho ) \; \textrm {d}k \, \boldsymbol{e\!}_x - \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \int _0^\infty \frac {\exp ( k z ) \left ( k z - 1 \right ) }{2 k^2} J_0 ( k \rho ) \; \textrm {d}k \notag \\ &- \frac {z}{2} \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \int _0^\infty \exp ( k z ) J_0 ( k \rho ) \; \textrm {d}k \, \boldsymbol{e}_z \Bigg ]. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {{_{-1}\boldsymbol{u}}_a}{F_{\!a}} = \frac {1}{2 \pi } \Bigg [ &\int _0^\infty \exp ( k z ) J_0 ( k \rho ) \; \textrm {d}k \, \boldsymbol{e\!}_x - \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \int _0^\infty \frac {\exp ( k z ) \left ( k z - 1 \right ) }{2 k^2} J_0 ( k \rho ) \; \textrm {d}k \notag \\ &- \frac {z}{2} \, \boldsymbol{\nabla }_{\!xy} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \int _0^\infty \exp ( k z ) J_0 ( k \rho ) \; \textrm {d}k \, \boldsymbol{e}_z \Bigg ]. \end{align}

Alternatively, (2.68) may be obtained by employing the approach of Masoud & Shelley (Reference Masoud and Shelley2014) (see also § 2.3.2). Replacing for

![]() $ \mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \{ {_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a / F_{\!a} \}$

in (2.67) from (2.68) and simplifying yields

$ \mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \{ {_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a / F_{\!a} \}$

in (2.67) from (2.68) and simplifying yields

\begin{align} &\left ( \frac {\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell }{\alpha \dot {m}^\star } \right ) \int _{- \infty }^0 \int _{\mathbb{R}^2} \big ( \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \big ) \mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \right \} \!(\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \big\{ {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(1)}\big \} \!(-\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}) \; \textrm {d}\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \, \textrm {d}\tilde {z} \notag \\ &\,= - \frac {1}{2} \, \int _{-\infty }^ 0 \int _{\mathbb{R}^2} \big ( \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \big ) \exp (\tilde {k} \tilde {z}) \notag \\[5pt] &\, \times \left \{ \left ( 2 \tilde {z} + \frac {1}{\tilde {k}} \right ) \exp ( \tilde {k} \tilde {z} ) - \left [ \left ( \tilde {z} + \frac {1}{\tilde {k}} \right ) \frac {\sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 + \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}}{\tilde {k}} +\tilde {z} \right ] \exp \! \left ( \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 + \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} \, \tilde {z} \right ) \right \} \textrm {d}\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \, \textrm {d}\tilde {z}. \end{align}

\begin{align} &\left ( \frac {\mathscr{D} \mu U^\star \ell }{\alpha \dot {m}^\star } \right ) \int _{- \infty }^0 \int _{\mathbb{R}^2} \big ( \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \big ) \mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \! \! \left \{ \frac {{_{-1}{\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}}_a}{F_{\!a}} \right \} \!(\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}) \boldsymbol{\cdot }\mathfrak{F}_{\textit{xy}} \big\{ {\tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}}^{(1)}\big \} \!(-\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}) \; \textrm {d}\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \, \textrm {d}\tilde {z} \notag \\ &\,= - \frac {1}{2} \, \int _{-\infty }^ 0 \int _{\mathbb{R}^2} \big ( \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \big ) \exp (\tilde {k} \tilde {z}) \notag \\[5pt] &\, \times \left \{ \left ( 2 \tilde {z} + \frac {1}{\tilde {k}} \right ) \exp ( \tilde {k} \tilde {z} ) - \left [ \left ( \tilde {z} + \frac {1}{\tilde {k}} \right ) \frac {\sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 + \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}}{\tilde {k}} +\tilde {z} \right ] \exp \! \left ( \sqrt { \tilde {k}^2 + \boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}} \, \tilde {z} \right ) \right \} \textrm {d}\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} \, \textrm {d}\tilde {z}. \end{align}

Carrying out the

![]() $z$

-integration and simplifying further gives

$z$

-integration and simplifying further gives

\begin{align} \int _{\mathbb{R}^2} 1 - \sqrt {1 + \frac {\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k}^2}} + \frac {\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{2 \tilde {k}^2} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} = \int _0^\infty\! \int _0^{2 \pi }\! \left ( 1 - \sqrt {1 + \frac {i \cos \phi }{\tilde {k}}} + \frac {i \cos \phi }{2 \tilde {k}} \right ) \tilde {k} \; \textrm {d}\phi \, \textrm {d}\tilde {k}, \end{align}

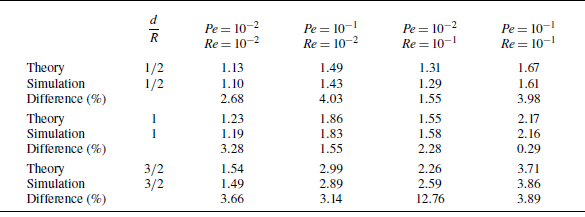

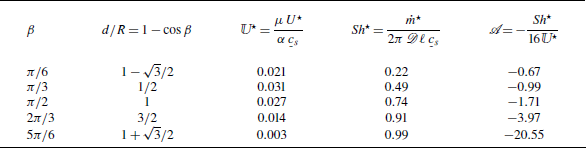

\begin{align} \int _{\mathbb{R}^2} 1 - \sqrt {1 + \frac {\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{\tilde {k}^2}} + \frac {\boldsymbol{e\!}_x \boldsymbol{\cdot }i \tilde {\boldsymbol{k}}}{2 \tilde {k}^2} \; \textrm {d}\tilde {\boldsymbol{k}} = \int _0^\infty\! \int _0^{2 \pi }\! \left ( 1 - \sqrt {1 + \frac {i \cos \phi }{\tilde {k}}} + \frac {i \cos \phi }{2 \tilde {k}} \right ) \tilde {k} \; \textrm {d}\phi \, \textrm {d}\tilde {k}, \end{align}