1. Introduction

Gambling disorder (GD) is a behavioural addiction characterised by an excessive and interfering pattern of gambling, leading to significant clinical symptoms and social impairments [Reference American Psychiatric Association1]. It is also described as a rather heterogeneous disorder [Reference Calado and Griffiths2] that presents high rates of treatment dropouts and relapses [3–Reference Jimenez-murcia, Aymam, Alvarez-moya, Santamar, Fern and Granero5]. An important source of heterogeneity is gambling modality, which is commonly grouped into two broad categories: strategic gambling (a structured approach or attempt to use knowledge of the game to influence or predict the outcome and produce a profit, e.g.: poker cards, dice, sports betting or stock market) and non-strategic gambling (a non-structured approach which involves little or no decision making or skill; gamblers cannot influence the outcome, e.g. lotteries, slots-machines or bingo) [Reference Odlaug, Marsh, Kim and Grant6]. Studies have found that strategic gamblers show more severe problems and poorer clinical outcomes than non-strategic gamblers for still unclear reasons [Reference Moragas, Granero, Stinchfield, Fernández-Aranda, Fröberg and Aymamí7]. Heterogeneity has further increased with the growth of online gambling modalities (in contrast to the offline ones), for which we are still developing standard models of care [Reference Mccormack, Shorter, Griffiths, Mccormack, Shorter and Griffiths8], based on the patients’ gambling activity and the perception of impairment related to each modality [Reference Hubert and Griffiths9]. Identifying the cognitive drivers of these different GD phenotypes, which can lead to develop personalized treatment approaches, has been deemed essential to navigate this heterogeneity with the aim of improving the outcomes of current interventions [Reference Yücel, Oldenhof, Ahmed, Belin, Billieux and Bowden-Jones10]. Elevated impulsivity and gambling-related cognitive distortions are key cognitive mechanisms of GD and sensitive to individual differences, but it is still unclear how they contribute to different GD phenotypes.

Impulsivity is a multifaceted construct that reflects the tendency to act quickly without sufficient consideration of the consequences of actions. People with GD generally show high levels of impulsivity and its role in treatment response has been widely acknowledged [11–Reference Jara-Rizzo, Navas, Steward, López-Gómez, Jiménez-Murcia and Fernández-Aranda14]. Impulsivity is highly linked to different impairments across multiple cognitive domains [Reference Grant, Odlaug and Chamberlain15]. For instance, literature on addictive behaviours (including substance use disorder and GD) report the presence of alterations on inhibitory control, lack of goal maintenance and difficulties when anticipating long-term outcomes [Reference van Holst, van den Brink, Veltman and AEG16, Reference Bühringer, Wittchen, Gottlebe, Kufeld and Goschke17]. Moreover, different studies highlight the association between affective impulsivity (i.e. the tendency to engage in impulsive behaviours when experiencing certain emotions) and GD severity [Reference Billieux, Lagrange, Van Der Linden, Lançon, Adida and Jeanningros18, Reference Yan, Zhang, Lan, Li and Sui19]. Cognitive distortions are irrational beliefs about gambling outcomes and the capacity to influence them [Reference Clark, Averbeck, Payer, Sescousse, Winstanley and Xue20, Reference Lévesque, Sévigny, Giroux and Jacques21], such as beliefs that one can control gambling related wins or that continued gambling will recoup lost money [Reference Leonard and Williams22, Reference Ciccarelli, Griffiths, Nigro and Cosenza23]. The causality of these distortions in GD is believed to be bidirectional as they seem to be risk factors for both the development and maintenance of the disorder and to remit spontaneously with the disorder even when not directly treated [Reference Del Prete, Steward, Navas, Fernández-Aranda, Jiménez-Murcia and Oei24]. It should be noted that cognitive distortions are a transdiagnostic feature for the occurrence and maintenance of mental disorders -such as depression [Reference BECK25], anxiety [Reference Kaczkurkin and Foa26], obsessive compulsive disorder [Reference Hezel and McNally27], eating disorders [Reference Strauss and Ryan28], among others. Furthermore, impulsivity and cognitive distortions seem to have overlapping neural substrates, as individual variations in both of these domains are linked to dopamine availability in striatal regions [Reference van Holst, Sescousse, Janssen, Janssen, Berry and Jagust29, Reference Pettorruso, Martinotti, Cocciolillo, De Risio, Cinquino and Di Nicola30]. Although impulsivity and cognitive distortions are meaningfully interrelated [Reference Mallorquí-Bagué, Mestre-Bach, Lozano-Madrid, Fernandez-Aranda, Granero and Vintró-Alcaraz13], few studies have concurrently assessed them. So far, studies have reported elevated cognitive distortions and trait impulsivity in patients with GD compared to healthy controls [Reference Michalczuk, Bowden-Jones, Verdejo-Garcia and Clark12] and specific associations between cognitive distortions and some facets of impulsivity (i.e.: urgency and sensation seeking) but not others (i.e.: lack of premeditation and lack of perseverance) [Reference Del Prete, Steward, Navas, Fernández-Aranda, Jiménez-Murcia and Oei24]. Moreover, Navas et al. (2017), classified recreational and problematic gamblers according to their gambling preference (strategic vs. non-strategic) and found higher cognitive distortions among those who preferred strategic games, whilst no differences were found for trait impulsivity [Reference Navas, Billieux, Perandrés-Gómez, López-Torrecillas, Cándido and Perales31].

Consistent evidence shows that strategic versus non-strategic and online versus offline gambling modalities reflect distinctive clinical phenotypes. GD patients with strategic gambling are described to be younger, with higher levels of psychopathology and alexithymia [Reference Moragas, Granero, Stinchfield, Fernández-Aranda, Fröberg and Aymamí7, Reference Bonnaire, Barrault, Aïte, Cassotti, Moutier and Varescon32],elevated cognitive distortions [Reference Lévesque, Sévigny, Giroux and Jacques33, Reference Toneatto, Blitz-Miller, Calderwood, Dragonetti and Tsanos34] and greater disinhibition and sensation seeking than those with non-strategic gambling [Reference Bonnaire, Barrault, Aïte, Cassotti, Moutier and Varescon32]. Non-strategic gamblers tend to process information in a more automatic way and are more inclined to trust their intuition than the strategic gamblers [Reference Mouneyrac, Lemercier, Le Floch, Challet-Bouju, Moreau and Jacques35]. With regard to offline versus online gamblers, the latter tend to be younger, more educated and present more co-occurring alcohol and cannabis use [Reference Del Prete, Steward, Navas, Fernández-Aranda, Jiménez-Murcia and Oei24, 29–Reference Navas, Billieux, Perandrés-Gómez, López-Torrecillas, Cándido and Perales31]. Since impulsivity and cognitive distortions contribute to GD development and maintenance, they are likely to differ among these clinical phenotypes and contribute to different treatment pathways [Reference Navas, Billieux, Perandrés-Gómez, López-Torrecillas, Cándido and Perales31, Reference Chrétien, Giroux, Goulet, Jacques and Bouchard37]. However, there is a dearth of research on the role of impulsivity and cognitive distortions in different GD clinical phenotypes and related treatment outcomes [Reference Bonnaire, Barrault, Aïte, Cassotti, Moutier and Varescon32, Reference Loree, Lundahl and Ledgerwood38, Reference Verdejo-García, Lawrence and Clark39].

This study sought to characterise profiles of impulsivity and cognitive distortions in the strategic/non-strategic and online/offline GD clinical phenotypes, and the longitudinal association between these profiles and treatment outcomes. Thus, our first aim was to compare strategic vs. non-strategic gamblers and online vs. offline gamblers on multidimensional measures of impulsivity and cognitive distortions. Our second aim was to examine the association between individual variation in impulsivity and cognitive distortions (at treatment onset) and clinical outcomes following GD treatment (3-months follow-up). Based on previous studies exploring cognitive distortions as a function of gambling preferences [Reference Navas, Billieux, Perandrés-Gómez, López-Torrecillas, Cándido and Perales31], we hypothesised that strategic and online gamblers would have generally higher cognitive distortions than non-strategic and offline gamblers, and that elevated distortions and impulsivity (particularly, negative urgency, which have been linked to poorer outcomes in substance addictions) would predict higher treatment dropouts and relapses.

2. Methods

2.1 Design

This study analyses cross-sectional and longitudinal data. At baseline, the concurrence (covariance) of trait impulsivity and cognitive distortions was estimated, as well as the comparison of these traits according to gambling preferences (strategic vs. non-strategic and online vs. offline). Afterwards, patients received cognitive behavioural group therapy (CBT) and the longitudinal predictive capacity of the pre-treatment measures (independent variables: trait impulsivity and cognitive distortions) on treatment efficiency (outcomes: dropout and relapses) was estimated.

2.2 Participants

The study was comprised of 245 male consecutive treatment seeking patients diagnosed with GD according to DSM-5 criteria [Reference American Psychiatric Association1] and who attended to a GD unit, which belongs to a general public health hospital, between july-2016 and august-2018. Due to missing data and inability to complete the whole assessment, 40 participants were excluded from the sample. The final sample consisted of 205 participants (mean age = 42.38 years, S.D = 13.55, age range = 18–77). The participants were enrolled in the study when they first attended the GD unit for its assessment before starting treatment (CBT group therapy). After accepting to be part of the study and completing the whole assessment (at baseline), 27 participants did not start the assigned treatment and 78 participants have either not yet been assigned to treatment (waiting list) or presented missing data thus they have not been included in the treatment outcome analyses (i.e.: treatment dropout and relapse rates). For this specific longitudinal analysis the sample was comprised of 100 participants (mean age = 43.2years, S.D = 13.4, age range = 19–77). All participants were recruited from the GD Unit within the Department of Psychiatry at Bellvitge University Hospital. This hospital oversees the treatment of very complex cases as it is certified as a tertiary care centre for the treatment of behavioural addictions. Only patients who sought treatment for GD as their primary health concern were admitted to this study. GD is more frequent in men than women [Reference Granero, Penelo, Martínez-Giménez, Álvarez-Moya, Gómez-Peña and Aymamí40, Reference Martins, Tavares, da Silva Lobo, Galetti and Gentil41] thus very few women seek treatment for GD at our unit; consequently, only males were included in this study and data from women will be included in a future study once the sample has achieved enough statistical and clinical power. Exclusion criterion for being part of the treatment protocol were: (a)history of chronic medical illness or neurological condition that might affect the assessment; (b)brain trauma, a learning disability or intellectual disabilities; (c)age under 18.

Written informed consent was obtained before participation in the study, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital of Bellvitge in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 1983 (reference number PR095/16). Participants received no additional compensation for being part of the study.

2.3 Cognitive behavioural therapy intervention

Participants received the protocolized CBT outpatient treatment of our unit which consisted on a 16 weekly group sessions lasting 90 min each. This treatment protocol has previously been described and it has shown an adequate effectiveness for GD in both short and medium terms [42–Reference Jiménez-Murcia, Aymamí-Sanromà, Gómez-Peña, Álvarez-Moya and Vallejo44]. The main goal of the intervention is to eventually arrive at full abstinence by training the patients to implement CBT strategies in order to minimize GD maladaptive behaviours. The key topics covered during treatment are: psychoeducation (GD definition, course and vulnerability factors, etc.), stimulus control (such as money management and avoidance of potential triggers), reinforcement and self-reinforcement, response prevention, cognitive restructuring focused on illusions of control over gambling, problem solving and relapse prevention techniques. CBT groups were conducted by an experienced clinical psychologist and a clinically trained co-therapist. Only patients who do not have other severe comorbid psychiatric disorders and that need GD treatment can be part of the group therapy, otherwise patients follow individual therapy.

2.4 Measures

GD diagnosis and GD severity: Patients were assessed with the DSM-5 criteria [Reference American Psychiatric Association1] via a face-to-face clinical interview and the Spanish validation of SOGS [Reference Lesieur and Blume45, Reference Echeburúa, Báez, Fernández and Páez46], which is a 20-item diagnostic questionnaire that discriminates between probable pathological, problem and non-problem gamblers. Internal consistency in our sample was of 0.715. Demographic and social variables related to gambling were also measured in all participants.

UPPS-P Impulsive behaviour scale [Reference Whiteside, Lynam, Miller and Reynolds47] is a 59-item questionnaire to assess five different features of trait impulsivity: Lack of Perseverance, Lack of Premeditation, Sensation Seeking, Negative Urgency and Positive Urgency. The UPPS-P has satisfactory psychometric properties, which have also been proven in its Spanish adaptation [Reference Verdejo-García, Lozano, Moya, Alcázar and Pérez-García48]. The α values for the different UPPS-P scales in our sample ranged from 0.756 to 0.940.

Gambling-related cognitions scale (GRCS; [Reference Raylu and Oei49]) is a 23-item questionnaire to assess a variety of gambling-related cognitions both in the general population and in disordered gambling. It measures five different cognitive domains: interpretive bias (GRCS‐IB; e.g.“Relating my winnings to my skill and ability makes me continue gambling”), illusion of control (GRCS-IC; e.g. “I have specific rituals and behaviours that increase my chances of winning”), predictive control (GRCS‐PC; e.g. “Losses when gambling are bound to be followed by a series of wins”), gambling-related expectancies (GRCS‐GE; e.g.“Gambling makes things seem better”) and perceived inability to stop gambling (GRCS‐IS; e.g. “I’m not strong enough to stop gambling”). The GRCS, has adequate psychometric properties both in its original version and in its Spanish adaptation [Reference kum and Oei50]. The α values for the different GRCS sub-scales in our sample ranged from 0.767 to 0.933.

Treatment dropout and relapse rates: Dropout and relapse rates were considered as indicators of treatment outcomes. A relapse indicates that the patient presented a full gambling episode once CBT treatment started, regardless of whether the relapse occurs with the specific type of the gambling preference or another. That means any gambling episode constitutes a relapse in the present study. A dropout was established if the patient missed a treatment session on three or more occasions without prior notifying the clinician.

2.5 Analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out with Stata15 for Windows. For the cross-sectional analysis (baseline measures) we explored the associations between different gambling related variables (severity, cognitive distortions and trait impulsivity) through partial correlation coefficients (R) adjusted by age and GD duration. Due to the strong association between the statistical significance of R-coefficients and the sample size, the partial correlation effect sizes were established as follow: poor-low |R|>0.10, moderate-medium |R|>0.24 and large-high |R|>0.37. These thresholds correspond to a Cohen’s-d of 0.20, 0.50 and 0.80 respectively [Reference Rosnow and Rosenthal51]. The baseline clinical profile comparison based on gambling preference (non-strategic vs. strategic and offline vs. online) was conducted with analysis of variance (ANOVA) adjusted by the covariates age and GD duration. The mean difference of the effect size was estimated with Cohen’s-d coefficient: poor-low |d|>0.20, moderate-medium |d|>0.5 and large-high |d|>0.8 [Reference Kelley and Preacher52]. In order to control for multiple comparisons type-I error [Reference Simes53] the Simes’ method was implemented, which is included in the Family wise error rate stepwise system and is more powerful than the classical Bonferroni correction.

Also, we longitudinally assessed the predictive capacity of trait impulsivity and cognitive distortions (independent variables) on CBT outcomes (dependent variables: presence of relapses during treatment and dropout of treatment) through multiple binary logistic regressions adjusted by age and GD duration. The modeling was defined in two blocks: block 1 entered and fixed the covariates (age and GD duration), block 2 added and tested the independent variables (i.e.: trait impulsivity and cognitive distortions). The fitting of the final logistic regressions was tested with Hosmer-Leme show (goodness-of-fit was considered ifp >.05), and the global capacity of the predictors with the Nagelkerke’s pseudo-R2 coefficient increase (ΔR2), comparing blocks 1 and 2 of the logistics.

3. Results

3.1 Characteristics of the sample at baseline

Table 1 includes the descriptive data of the sample (before starting CBT treatment). The majority of participants were born in Spain (almost 93%), were single (46.3%) or lived with a stable partner (41.0%), had primary education (62.9%), were in active employment (61.0%) and their socioeconomic status (measured by the Hollingshead index; [Reference Hollingshead54]) was low (87.8%). The mean age of GD was 22.8 years (SD = 10.0) and the mean duration of GD was 15.1 years (SD = 12.3). The prevalence of tobacco use was 54.6%, alcohol use 27.8% and other illegal drugs 10.7%, and 30.2% of the sample reported problems due to other psychiatric disorders. See Table 1 for frequency distributions of trait impulsivity, cognitive distortions and other gambling related variables.

Table 1 Descriptive for the cross-sectional sample (n = 205).

Note. SD: standard deviation. Cronbach’s alpha in the sample.

Non-strategic gamblers were younger (p =.002), with an earlier age of onset (p <.001) and a longer duration of the GD (p =.001) than strategic gamblers. No differences were found between these two groups when comparing the rest of the sociodemographic variables (p > 0.05 for all the variables). Differences also emerged comparing the offline vs. online gamblers in: age (younger age in online gambling; p <.001), duration of problematic gambling (lower duration in online gambling; p =.003), civil status (online gamblers were predominantly single -61.5%- whereas offline gamblers were mainly married or divorced -58.8%-; p =.039) and education (online gambling was more frequent in patients with higher education; p =.002).

3.2 Association between gambling variables

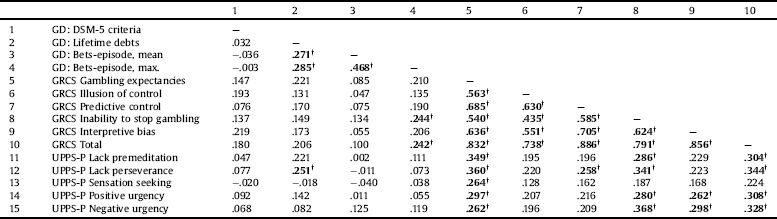

Table 2 contains the partial correlation matrix (adjusted by age and GD duration). Considering GD severity (DSM-5 criteria, lifetime debts and bets per gambling-episode), positive correlations were found between lifetime debts and lack of perseverance, as well as between maximum bets-per gambling episode and GRCS-IS and GRCS-total. Many positive correlations were also found between cognitive distortions (GRCS scores) and trait impulsivity (UPPS-P scores). Namely, GRCS-GE correlated with all trait impulsivity measures; GRCS-total and GRCS-IS correlated with all trait impulsivity subscales but sensation seeking; GRCS-IB correlated with positive and negative urgency, GRCS-PC only correlated with lack of perseverance.

Table 2 Partial correlations (adjusted by age and duration of the gambling) (n = 205).

Note1.

† Bold: effect size into the moderate (|r|>0.24) to high range (|r|>0.30).

3.3 Comparison of the impulsivity/cognitive distortions profile based on clinical phenotypes

Table 3 contains the comparison of cognitive distortions and trait impulsivity in patients with non-strategic gambling vs. strategic gambling as well as offline vs. online gambling (ANOVA adjusted by age and GD duration). Statistical differences between strategic and non-strategic gamblers were as follow: higher mean scores of GRCS-GE, GRCS-IC, GRCS-total and lack of perseverance in patients with strategic gambling than in patients with non-strategic gambling. All these associations presented a mean difference of effect size within the low range. Regarding offline vs. online gamblers, statistical differences with effect sizes into the medium-moderate range were found in all the GRCS scales (i.e.: online gamblers had higher GRCS means) but in GRCS-IS, which achieved statistical significance but low effect size.

Table 3 Comparison of the clinical profile based on the gambling subtype: ANOVA adjusted by age and duration of the gambling.

Note. SD: standard deviation.

* Bold: significant comparison (.05 level).

† Bold: effect size into the moderate (|d|>0.50) to high range (|d|>0.80).

3.4 Predictive capacity of impulsivity and gambling-related cognitions on CBT outcome

Table 4 contains the results of the logistic models (adjusted by age and GD duration) measuring the predictive capacity of trait impulsivity and cognitive distortions on treatment outcome. Three different models were computed: a) trait impulsivity dimensions (UPPS-P scales); b)cognitive distortions (GRCS subscales); and c)cognitive distortions total score(GRCS-total). The patients with higher risk of relapses were the ones with higher negative urgency/GRCS-IS, or lower GRCS-IB. Also, patients with higher levels of lack of perseverance presented higher risk of dropout. The predictive capacity of cognitive distortions and trait impulsivity were higher for the presence of relapses than for treatment dropout. The highest increase in the Nagelkerke’s pseudo-R was in GRCS subscales (ΔR2 =.207), followed by the UPPS-P scales (ΔR2 =.207), as predictors of relapses.

Table 4 Predictive capacity of impulsivity and cognitive biases on the CBT outcomes: logistic regression adjusted by age and GD severity at baseline (DSM-5 criteria)(n = 100).

Note.

* Bold: significant parameter (.05 level).

4. Discussion

We showed that patients with GD and online phenotypes have generally higher cognitive distortions than those with offline phenotypes, whereas strategic phenotypes have higher distortions related to gambling expectancies and illusion of control and less perseverance than non-strategic phenotypes. Although differences were of small-medium effect size, individual variations in these features significantly predicted clinical outcomes. Specifically, lack of perseverance predicted dropout and inability to stop and interpretative biases longitudinally predicted risk of relapse. These findings suggest the need to incorporate specific treatment strategies to reappraise biases and reduce impulsivity in strategic/online gamblers.

Broadly higher cognitive distortions in online gamblers suggest that this clinical phenotype is more severe, complex and likely to require specific treatment approaches [Reference Chrétien, Giroux, Goulet, Jacques and Bouchard37, 55–Reference Emond and Marmurek57]. It remains unclear if cognitive distortions precede and influence preferences for online gambling options, or if online gambling modalities disproportionately affect cognitive distortions. Regardless of aetiology, our findings stress the need to specifically target these cognitions during the treatment of these patients. In agreement with previous evidence [Reference Navas, Billieux, Perandrés-Gómez, López-Torrecillas, Cándido and Perales31, Reference Lévesque, Sévigny, Giroux and Jacques33, Reference Toneatto, Blitz-Miller, Calderwood, Dragonetti and Tsanos34] strategic gamblers also showed heightened cognitive distortions, specifically gambling-related expectancies and illusion of control which can act as gambling maintaining factors. We also found for the first time that strategic gamblers had greater lack of perseverance, a facet associated with low conscientiousness and inability to focus on complex tasks, which seems to be at odds with the preference for strategic games. In this context, lack of perseverance may put strategic gamblers at greater risk of accumulating losses [Reference Worhunsky, Potenza and Rogers58]. Cognitive and impulsivity profiles have potential to inform new models of care in the currently evolving GD treatment space. Strategic gamblers are day by day more differentiated from non-strategic gamblers and the rise of online gamblers with the bigger internet use have increased interest of researchers and clinicians alike [Reference Kairouz, Paradis and Nadeau36, Reference Yazdi and Katzian59, Reference Cole, Barrett and Griffiths60].

These findings in strategic and online gamblers are even more relevant given the predictive capacity of cognitive distortions and trait impulsivity on treatment outcomes (i.e.: relapses and dropout of treatment). In terms of impulsivity, a study carried out with online poker players (strategic and online gamblers) found that the inability to stop gambling and the illusion of control were good predictors of pathological gambling [Reference Barrault and Varescon55]. Moreover, sensation seeking and negative urgency were found to be predictors of GD severity [Reference Savvidou, Fagundo, Fernández-aranda, Gómez-peña, Agüera and Tolosa-sola61]. Nevertheless, regarding motor impulsivity, Grant et al. (2012) did not find differences between strategic and non-strategic gamblers [Reference Grant, Odlaug, Chamberlain and Schreiber62]. More specifically, lack of perseverance predicted dropping out of treatment, which reflects that the tendency to not persist in an activity that can be complex –e.g., therapy guidelines for GD– or boring poses a significant challenge for treatment retention. The association between lack of perseverance and dropouts was also found by Mestre-Bach et al., 2018 [Reference Mestre-Bach, Steward, Granero, Fernández-Aranda, Pino-Gutiérrez and Mallorquí-Bagué63], who also reported that negative urgency predicted relapses and found no significant results in sensation seeking, lack of premeditation or positive urgency. Nevertheless, in contrast to what has been found in the current study, elevated punctuations on sensation seeking increased the risk of dropouts [Reference Mestre-Bach, Steward, Granero, Fernández-Aranda, Pino-Gutiérrez and Mallorquí-Bagué63]. Also, severe GD patients that presented high scores in psychopathology, low persistence and low reward dependence at baseline, had poor progress in GD severity during treatment and follow-up compared to other severe patients [Reference Jiménez-Murcia, Granero, Fernández-Aranda, Aymamí, Gómez-Peña and Mestre-Bach64]. Furthermore, beliefs of inability to stop gambling (a cognitive distortions more highly observed in online and strategic gamblers), predicted the number of relapses during treatment. It is known that higher relapses during treatment are associated with poorer abstinent success rates, which predispose patients towards a higher risk of chronicity and prompts the need to specifically target these cognitions during the intervention. The results have important clinical implications for improving current treatment outcomes by personalizing approaches according to specific GD phenotypes.

Contrary to previous findings [Reference Emond and Marmurek57], we found no associations between cognitive distortions and GD severity. However, higher scores in cognitive distortions were linked to higher bets-episodes, a proxy of binge gambling. Additionally, we were able to replicate previous work regarding the associations between cognitive distortions and trait impulsivity together with the role of negative urgency in treatment outcome. This reflects that what is prompting more relapses in our sample is the tendency to act impulsively when experiencing negative affect (e.g., frustration, fear, anxiety or sadness). A recent study exploring different impulsive and compulsive related domains implicated in GD treatment outcome also revealed the relevance of negative urgency in the number of relapses during treatment [Reference Mitchell and Potenza11, Reference Verdejo-García, Lozano, Moya, Alcázar and Pérez-García48]. Although research with GD samples is still scarce, a current meta-analysis of substance-related addictions has proposed that negative urgency is associated with poorer psychotherapy outcomes [Reference Hershberger, Um and Cyders65].

This study has several strengths including a large representative sample of treatment-seeking gamblers who were consecutively recruited across two years, and a longitudinal design that follows the course of a standardized treatment which is the current gold standard for GD. There are also limitations derived from this naturalistic approach. First, the sample was composed of treatment-seeking patients with GD, and findings may not generalize to other community samples or to all levels of disordered gambling from general population. Second, our sample is restricted to male patients with GD because we have comparatively very few female patients and we are recruiting for an extended period to have enough statistical power in future studies. Further studies should include female participants and different community samples. It will be necessary to continue expanding clinical samples of women to explore if the results obtained in men are confirmed or if, given the very specific characteristics of women with GD, the findings suggest the existence of other relationships. Finally, the self-reported nature of some of the data can lead to recall bias.

In conclusion, we provide the first systematic characterization of impulsivity and cognitive distortions profiles in different GD clinical phenotypes and evidence of specific facets and cognitive distortions that predict GD treatment outcomes. Online gamblers have overall higher distortions and strategic gamblers have less perseverance and more irrational expectancies and illusions of control. Cognitive distortions, low perseverance and high emotion-driven impulsivity predicted poorer treatment outcomes. The results are highly relevant for improving current treatments by targeting specific cognitions and traits that can lead to a more successful therapy.

Acknowledgements

Financial support was received through the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (PSI2015-68701-R) and from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) [FIS PI14/00290, FIS PI17/01167, cofounded by FEDER funds/European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), a way to build Europe and 18MSP001 -2017I067 received aid from the Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad]. MINECO is part of Agencia Estatal de Investigación. CIBER Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBERObn) and CIBER Salud Mental (CIBERSam) are both initiatives of ISCIII. We thank CERCA Programme / Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support. CVA and TMM are supported each one by a predoctoral grant of the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (FPU16/01453; FPU16/02087). AVG is funded by an Australian Medical Research Future Fund CDF 2 Fellowship (MRF1141214). GMB is supported by a predoctoral AGAUR grant (2018 FI_B2 00174), co-financed by the European Social Fund, with the support of the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.