Introduction

Unlike other parts of the world, in Western Europe the evidence of society's increasingly low reliance on supranational beliefs, matched by a dwindling proportion of churchgoers, is so strong that current academic debates do not revolve around the existence of secularisation but, rather, around its causes and actual significance (Norris & Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2004: 83−110). Given that the politics of most advanced democracies has been shaped by the religious/secular cleavage, it has often been assumed that religious identity and beliefs would soon cease to impact West Europeans’ voting behaviour. This assumption rests upon two mechanisms that have not always received clear support in empirical research. First, it is argued that, as the number of religious citizens decreases, parties that used to rely on their support will be forced to moderate some of their policy stances in order to attract new constituencies (Dalton Reference Dalton, LeDuc, Niemi and Norris2002, p. 201). Second, as religion loses much of its social and political significance, the values and political preferences of religious and non‐religious voters are often expected to become more alike (Evans & Northmore‐Ball Reference Evans, Northmore‐Ball, Fisher, Fieldhouse, Franklin, Gibson, Cantijoch and Wlezien2018). Although there is little doubt that religious voters have become a smaller (and, therefore, also a less influential) group, research into the electoral impact of religion has failed to find consistent evidence of a decline in religious voting. Conservative and Christian Democratic parties continue to perform significantly better than other parties among religious voters in contemporary West European democracies, even though the size of this effect varies substantially across countries (Knutsen Reference Knutsen2018). Many studies have shown that the differences between the party preferences of religious and non‐religious voters have not consistently decreased across most of Western Europe ‐ and, in some cases, they have even increased over time (Knutsen Reference Knutsen2004, Reference Knutsen2018; Elff Reference Elff2007; Van Der Brug et al. Reference Brug, Hobolt and De Vreese2009; Raymond Reference Raymond2011; Tilley Reference Tilley2015). In contrast, other studies analysing a longer (and more recent) time period have found a certain decline in the impact of religion in countries such as Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands, but not in other countries such as Britain (Lachat Reference Lachat2007; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2020). The picture is, therefore, more complicated than it seems. This begs the question, why has secularisation not blurred the differences between the political preferences of religious and non‐religious voters?

A recent approach to this issue questions the simplistic view that the extent or timing of secularisation can, on their own, explain the variation in religious voting across elections and countries. On the contrary, political elites are deemed to be essential for understanding the impact of religion on vote choice. In a nutshell, when differences between religious and non‐religious voters have shrunk it has been because Conservative and Christian Democratic parties have actively sought to converge with other parties on issues, such as traditional morality, that religious voters care about (Elff Reference Elff2009; Jansen et al. Reference Jansen, Graaf and Need2012; de Graaf et al. Reference Graaf, Jansen, Need, Evans and Graaf2013; Evans & de Graaf Reference Evans, Graaf, Evans and Graaf2013a). Although this ‘top‐down’ approach is genuinely promising and more sophisticated than previous approaches, it has so far focused on exploring the role of short‐term changes in parties’ positions between elections rather than their long‐term impact, which seems relevant for explaining the influence of structural factors such as religion. The goal of this piece is therefore not to question the role of parties in activating or deactivating cleavages between elections, but rather to expand this approach by exploring the potential long‐term impact of parties’ past strategic choices on individuals’ electoral behaviour.

This article aims to contribute to the current debates on parties’ ability to shape the effects of structural factors by focusing on the role of generational dynamics. Drawing on the impressionable years literature, which has been widely applied to electoral behaviour theory since at least Campbell et al.’s (Reference Campbell1960) lifelong persistence model, I argue that the relative positions on moral issues held by political parties when voters are aged between 15 and 25 years have a lasting impact on how religiosity influences the latter's vote choices. Evidence supporting this hypothesis is shown using survey data from 19 West European democracies from 2002 to 2018 in combination with party manifesto data on past party positions. The findings have important implications because, besides contributing to our understanding of the role of political parties in activating or deactivating political cleavages, they also help to explain why the effect of religion on vote choice differs across cohorts and its overall impact changes ever so slowly even in contexts of widespread or increasing secularisation.

The first section of this article reviews the literature on the effect of religion on voting. The second section lays out the theoretical background, which integrates the ‘top‐down’ approach to religious voting with the ‘impressionable years’ model of political learning. After describing the dataset and explaining the case selection, the operationalisation of the main variables and the method employed in the third section, the fourth section presents the results. As is customary, the last section then discusses the implications of the findings.

Religion and mainstream conservatism

The relationship between religion and vote choice has long been documented, and was at the core of Lipset and Rokkan's (Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967, p. 19) well‐known State–Church cleavage, which emerged from the conflict over values and cultural identities stemming from the National Revolutions. Conservative parties were among the first parties to appeal to religious voters in Europe because, while they are not confessional, they played a major role in resisting Liberal anticlerical attacks seeking to deprive organised religion from its control over issues such as family and education. In some countries (particularly in those where the Right was not able to stop Liberal reforms), Christian Democratic movements emerged later on as separate organisations seeking the support of religious voters. Although Conservative and Christian Democratic parties competed for some time with each other for the anti‐Liberal vote, in those countries where Christian Democracy was electorally successful and established itself as the main party of the conservative political space, it eventually ended up co‐opting conservative political elites and replacing Conservative parties altogether (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas1996, pp. 222−226). The opposite was nevertheless the case in countries such as France, Spain or Greece, among others, where successful Conservative parties prevented the survival of explicitly confessional platforms.

In the context of the religious cleavage, many researchers make a conceptual distinction between denominational identities (which are associated with denominational voting) and the secular–religious conflict (which is associated with what tends to be called religious voting) (Wolf Reference Wolf1996; Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Nieuwbeerta and Manza2006; Elff & Roßteutscher Reference Elff and Roßteutscher2011). Even though the main differences in contemporary voting behaviour are found between religious and non‐religious voters, significant denominational differences are still present in many European countries (Knutsen Reference Knutsen2018, pp. 131−141).Footnote 1 Denominational voting rests upon identarian bonds between particular religious groups and political parties that are contingent on countries’ historical developments. Conservative and Christian Democratic parties usually forged long‐term alliances with the major religious groups that stood in opposition to Liberal anticlericalism (Lipset & Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967, pp. 33−41). In countries dominated by Catholicism this was the Catholic Church, whereas in majority‐Protestant countries, such as Britain and the Nordic countries, conservative parties’ interests became intertwined with those of the dominant national church, and therefore smaller groups of voters such as non‐conformist Protestants (and Catholics in Britain) became aligned with non‐conservative forces (Lipset & Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967, p. 38; Madeley Reference Madeley1982).Footnote 2 In religiously mixed countries, where Protestants often allied with the nation‐builders to limit the influence of the Catholic Church, the interests of conservative forces aligned closely with those of Catholics (and other anti‐Liberal groups like Calvinists in countries such as the Netherlands).

Although patterns of denominational voting vary across countries, the differences between religious and non‐religious voters are much more consistent. Religious voting has an important identity component, but it is also guided by individuals’ wider religious orientations and values (Langsæther Reference Langsæther2019). Religious voters, regardless of their denomination, are not only more likely than their less religious counterparts to have morally conservative attitudes, but their opinions on moral issues also have a stronger influence on their vote, making them more likely to vote for Conservative and Christian Democratic parties (Stegmueller et al. Reference Stegmueller2012; Stegmueller Reference Stegmueller2013). Religious orientations have a separate impact on vote choice that tends to affect individuals across all major Christian denominations, and this can be seen in countries such as Britain, where Tilley (Reference Tilley2015, p. 919) finds religious practice to decrease support for the Labour party among all three main denominations (Church of England, Catholic and non‐conformist), or in Germany, where again church attendance increases voters’ probability to vote for the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) regardless of their denominational affiliation (Elff & Roßteutscher Reference Elff and Roßteutscher2011).

Bottom‐up and top‐down approaches

Religious voting has received much attention in the last decades in the context of the secularisation process that has affected virtually all West European democracies (Norris & Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2004, pp. 84−92; Voas Reference Voas2009). Secularisation entails a steady decrease in religious beliefs and church attendance for all religious groups, but also the individualisation of religious orientations and, therefore, the separation between individuals’ religious beliefs and their political preferences (Knutsen Reference Knutsen2018, pp. 73−75). In this context, it is somewhat surprising that religious orientations continue to be an important predictor of support for mainstream conservatism (often simply referred to as centre‐right)Footnote 3 in contemporary West European democracies (Duncan Reference Duncan2015; Tilley Reference Tilley2015; Knutsen Reference Knutsen2018). Yet, as Lachat (Reference Lachat2007) argues, political dealignment can take place through two different mechanisms: structural change and behavioural change. In the context of secularisation, structural change refers to the reduction in size of the group of religious voters. Scholars such as Best (Reference Best2011) contend that the numerical decline of religious voters has significant political implications because it entails a more or less irreversible reduction in their contribution to party vote shares and, therefore, pushes parties to compensate for that loss by attempting to attract non‐religious voters. Of course, religious voters have not disappeared from the face of Earth and, in fact, there is evidence that religious decline has already bottomed out in early‐declining countries, where there is a baseline of between 40 and 50 per cent of the population who consider themselves members of an organised religion (Kaufmann et al. Reference Kaufmann, Goujon and Skirbekk2012). In many proportional systems, securing the support of the majority of a group of this size could still guarantee a party's victory in a general election. However, there is little doubt that this group has become less decisive than it used to be, and, as a consequence, religion may have also become a less important factor for electoral competition. The second mechanism of dealignment is behavioural change. The political preferences of religious and non‐religious voters have been argued to become more alike as a result of secularisation, partly because of the decreasing social and political influence of religious groups (Dalton Reference Dalton1984). The loss of relevance of religion in the public sphere is often expected to entail wider societal acceptance of previously contentious issues such as sexual morality, even among religious individuals (Finke & Adamczyk Reference Finke and Adamczyk2008). However, it has also been argued that secularisation may have increased the distinctiveness of those who remain religious (Evans Reference Evans2010, p. 643), and could even be associated with greater religious polarisation (Ribberink et al. Reference Ribberink, Achterberg and Houtman2018). Overall, the evidence that secularisation has brought about behavioural dealignment (or realignment) in Western Europe is mixed. Knutsen (Reference Knutsen2004) finds no consistent trend in the effect of both religious identity and religious orientations on vote choice in eight West European countries between 1970 and 1997, with statistically significant declines in Denmark and Italy but fairly stable patterns in Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Ireland (see also Raymond Reference Raymond2011, who finds no decline in religious voting between the 1960s and the 1990s in Germany and Britain). Similarly, Van der Brug et al. (Reference Brug, Hobolt and De Vreese2009) find no clear downward trend in the explanatory power of religion on party preferences in Europe between 1989 and 2004, with early decreases followed by an increase in the 2000s. In contrast, other studies that analyse longer (and more recent) time series have found a decreasing effect of religion in Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands, although not in Britain (Lachat Reference Lachat2007; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2020).

One of the reasons why there is no unequivocal evidence of behavioural dealignment in Western Europe may lie in the role of parties’ strategic choices. Religious voters’ greater degree of moral conservatism is key for understanding their support for centre‐right parties (Stegmueller Reference Stegmueller2013). However, as Evans and de Graaf (Reference Evans, Graaf, Evans and Graaf2013a) argue, even though voters’ political preferences are shaped by socio‐demographic variables, their electoral choices are constrained by the existing party platforms. Although social cues are particularly relevant in contexts where political parties differ greatly on the issues that are associated with individuals’ social position, when party platforms converge around those issues voters are compelled to base their voting decisions on other matters. One of the expectations of the secularisation process and the decreased relevance of religious groups was precisely greater convergence between parties on moral issues. Yet, even though mentions of traditional morality are now less frequent than they used to be for many centre‐right parties (Euchner Reference Euchner2019, pp. 28−30), linear declines are not found everywhere (de Graaf, Jansen & Need Reference Graaf, Jansen, Need, Evans and Graaf2013). This could therefore explain the variation in the impact of religiosity on voting across Western Europe.Footnote 4

This supply‐side (or top‐down) approach to religious voting has found empirical support in several studies. De Graaf et al. (Reference Graaf, Jansen, Need, Evans and Graaf2013) and Jansen et al. (Reference Jansen, Graaf and Need2012) analysed religious voting in the Netherlands between 1976 and 2001, and found that the effect of religion increased when Christian Democratic parties emphasised moral traditionalism in their manifestos. In a similar vein, Elff's (Reference Elff2009) study, which focuses on Belgium, Denmark, France, Great Britain, Italy and the Netherlands over a period of 28 years (1974–2002), finds that moral traditionalism increases parties’ electoral support among regular churchgoers and decreases it among non‐churchgoers. Top‐down patterns of change in religious voting have also been found in case studies of countries such as Italy and France, although the evidence is either modest or inexistent for countries such as Germany or Spain, among others (Evans & de Graaf Reference Evans, Graaf, Evans and Graaf2013c).

Long‐term change and the top‐down approaches to religious voting

Part of the appeal of the top‐down approach to religious voting is that, contrary to the bottom‐up approach, it can also explain short‐term changes in the electoral strength of religiosity. Nonetheless, it would be wrong to conclude that long‐term changes are always fully explained by bottom‐up forces. As explained earlier, one of the reasons why secularisation is thought to lead to behavioural changes is because parties that drew much of their electoral support from religious individuals are expected to moderate their stances on moral issues to make their policies more palatable to the growing group of secular voters. Yet we know that some voters respond more swiftly than others to political changes – especially when these are not abrupt and radical. Therefore, it may take years before such changes fully bear fruit.

The decline of cleavage voting has been a very gradual process, not least because older generations of voters have continued to be strongly influenced by social loyalties such as class and religion (Franklin Reference Franklin, Franklin, Mackie and Valen2009). Research has shown that certain aspects of human central beliefs and dispositions, including values, identities and political orientations such as ideology and party identification, are most susceptible to external influence when individuals are young but crystallise and become fairly stable once people reach a certain age (Jennings Reference Jennings, Jennings and Deth1990; Alwin & Krosnick Reference Alwin and Krosnick1991). This empirical regularity provides support for what social psychologists have labelled the ‘impressionable years’ model of political learning (Alwin & McCammon Reference Alwin, McCammon, Mortimer and Shanahan2003). The ‘impressionable years’ model poses that people's core political beliefs are acquired through a learning process that is influenced by a wide range of experiences (interactions with family, friends, personal events, but also the general political and social context). Political learning seems to start early on in life, but is accelerated (at least in Western societies) during emerging adulthood (Delli Carpini Reference Delli Carpini and Sigel1989). This period is so important that adults tend to disproportionately recall memories of events that occurred during early adolescence and the early adult years (Rubin et al. Reference Rubin, Rahhal and Poon1998; Schroots et al. Reference Schroots, Van Dijkum and Assink2004). During this time, which Alwin and McCammon (Reference Alwin, McCammon, Mortimer and Shanahan2003, p. 38) characterise as a period of ‘sorting and sifting’, individuals gather a large amount of new political information, and sometimes change their views quite dramatically. However, as individuals learn more about politics, they form political predispositions and become less susceptible to changing their core political attitudes. This is consistent with Zaller's (Reference Zaller1992) ‘resistance axiom’, which states that individuals assess every new bit of information against their predispositions, and explains why people's political views do not change all the time. Under normal circumstances, political predispositions are formed during the period of emerging adulthood and become highly persistent thereafter (Sears & Funk Reference Sears and Funk1999).

Even though individuals are never completely ‘set in their ways’ and changes do occur later in life, the lasting influence of the ‘impressionable years’ (a loosely defined period which seems to peak at around 15–16 and 21–22 years of age) on people's voting behaviour is remarkable (Neundorf & Smets Reference Neundorf and Smets2017). It also explains why generational replacement is one of the most important driving forces of long‐term political change, as older voters are less likely to respond to normal political events by switching political allegiances (Hooghe Reference Hooghe2004). Accounting for the political context during people's ‘impressionable years’ is essential for understanding, at least partly, the differences in voting behaviour across individuals born at different points in time. Research has demonstrated that political scandals and wars can have a lasting effect on the political preferences of very young voters (Erikson & Stoker Reference Erikson and Stoker2011; Dinas Reference Dinas2013), but other more mundane short‐term factors, such as the structure of political supply, can also have distinct long‐lasting effects on voters (Smets & Neundorf Reference Smets and Neundorf2014). This has important implications for the study of the effect of religion on party choice. As political preferences are shaped by the political context that individuals experience during emerging adulthood, parties’ stances on moral issues could leave a significant imprint on the way in which religious beliefs inform young voters’ electoral choices. We can therefore speculate that religious differences in voting will be weaker for voters who are socialised into politics at times when parties converge on moral issues, and vice versa when parties’ platforms are very different from each other. So, while religiosity increases the probability of voting for centre‐right parties, its effect should be even greater for those voters who are exposed during their impressionable years to centre‐right policy platforms that are distinctively more traditionalist on moral issues than those of their competitors.

The idea that structural factors could be a more influential factor for some generations of voters than for others has found empirical support in several studies. Van der Brug (Reference Brug2010), for instance, found that religion and social class play a more important role for understanding the party preferences of Europeans socialised before the 1970s (i.e., during the ‘heyday’ of cleavage politics). Similarly, Van der Brug et al. (Reference Brug, Hobolt and De Vreese2009) found (non‐linear) cohort differences in the impact of religion on party preferences in Europe. Although differences between age cohorts have not always been corroborated by studies of specific countries, this may largely be due to the different trajectories of political parties’ efforts to mobilise the religious issue. Thus, while there is some evidence that support for the German CDU/CSU has deteriorated among younger churchgoers in recent elections (Elff & Roßteutscher Reference Elff and Roßteutscher2017), in the Netherlands, where Christian Democratic parties’ traditionalism has only been subject to timid changes and there is no evidence of a decline over time (de Graaf, Jansen & Need Reference Graaf, Jansen, Need, Evans and Graaf2013), differences in the effect of religion across cohorts are rather small (van der Brug & Rekker Reference Brug and Rekker2020).

Data, operationalisation and methods

To test the hypothesis outlined above, this study employs data from waves 1 to 9 of the European Social Survey (ESS), fielded biennially between 2002 and 2018 (European Social Survey Cumulative File, EES 1‐9 (2020)). The analysis will focus on 19 West European democracies. Post‐communist countries, Turkey and Israel are excluded from the analysis to maximise comparability across widely similar political and social contexts.Footnote 5

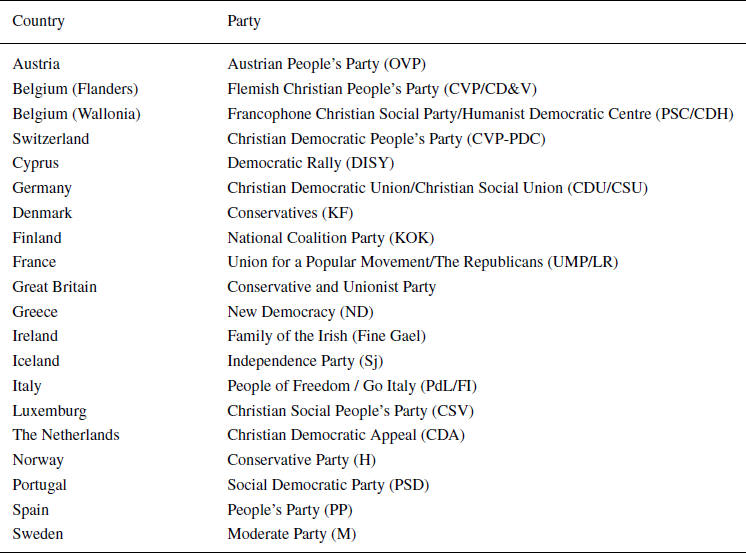

The operationalisation of the main variables is as follows. The dependent variable is a dichotomous indicator measuring whether respondents voted for the main Conservative/Christian Democratic party in the most recent legislative election (1) or for any other party (0).Footnote 6 A list of the parties included in each country can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. List of countries and centre‐right parties included in the analysis

Note: In Ireland, both Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael can be categorised as centre‐right parties, although the former has a more populist outlook, favours more economic interventionism and some of its leaders have sometimes referred to the party's fuzzy ideology as ‘left of centre’ (Puirséil Reference Puirséil2017). It will be tested if results remain robust when Fianna Fáil rather than Fine Gael is considered as the main centre‐right party.

The main independent variable is a measure of the centre‐right's divergence on moral issues (in relation to other parties) when individuals were aged between 15 and 25 years. This variable was created using information from the Manifesto Project (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens2019) measuring positive and negative mentions of traditional moral issues in party manifestos. The Manifesto Project codes as ‘traditional morality’ policy statements referring to traditional and/or religious moral values, including the stability and maintenance of the traditional family (as opposed to supporting modern family structures, same‐sex marriage, divorce, abortion, and so on), the suppression of immorality and unseemly behaviour, and the role of religion and churches in state and society (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens2019, p. 19). To the best of my knowledge, this is the only available data source that tracks parties’ positions on moral issues over a sufficiently long period of time. It also has the advantage that it is an objective indicator based on parties’ own documents (Bakker & Hobolt Reference Bakker, Hobolt, Evans and Graaf2013).

The centre‐right's divergence on moral issues (from here onwards also referred to as ‘moral divergence’) is measured as the relative position of the main Conservative/Christian Democratic party (which is the party that the dependent variable refers to) in relation to all other parties represented in parliament. This indicator was constructed for every election since the end of WW2 in the following manner:Footnote 7

• First, each party's position on moral issues was estimated by using the log ratio of positive to negative mentions of traditional morality in their manifestos (see Lowe et al. Reference Lowe2011 for more details about the procedure).Footnote 8 This indicator correlates highly (Pearson's r = 0.7) with the ‘social lifestyle’ variable from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, Liesbet, Seth, Gary, Jonathan, Jan, Marco and Milada2020), which measures parties’ positions on issues such as rights for homosexuals and gender equality.

• Next, I calculated the difference between the position of the main Conservative/Christian Democratic party and the mean position of all the other parties represented in parliament (weighted by their relative electoral strength).Footnote 9 Thus, the indicator takes on positive values when Conservative/Christian Democratic parties are more traditionalist than their average competitor, whereas a value of 0 indicates that they all share a similar position (a ‘convergence’ scenario). Conversely, negative values signify that Conservative/Christian parties adopt less traditionalist stances on moral issues than their average competitor (either because the former adopt liberal views on these issues or because their competitors emphasise traditional moral values even more strongly than they do). Overall, the data show different trajectories across countries rather than uniform party‐system convergence on moral issues over time (see Figure 1a of the Appendix in the Supporting Information).

After computing the centre‐right's ‘moral divergence’ indicator for each election, individuals in the sample were assigned the average value of those elections that took place when they were aged between 15 and 25 years.Footnote 10 Although the period between the ages of 15 and 25 is very often used in the literature, there is no consensus about the precise age range that constitutes the impressionable years, with some (but not all) authors claiming that it starts earlier than 18 and others showing that it can continue until individuals are at least 30 years old (Fox et al. Reference Fox2019, p. 384). Therefore, the robustness of results will also be checked against alternative age ranges (18–25 and 15–30).

The next key independent variable, religiosity, is an index that comprises religious orientations and church integration – two concepts that tend to be strongly correlated (Jagodzinski & Dobbelaere Reference Jagodzinski, Dobbelaere, Deth and Scarbrough1995). The index was created using principal component factor analysis with three variables: frequency of church attendance (a 7‐point scale ranging from never to weekly), frequency of prayer (a 7‐point scale ranging from never to every day) and subjective religiosity (an 11‐point scale ranging from not at all religious to very religious).Footnote 11 A potential problem is that religiosity is measured at the time that the survey was conducted rather than during voters’ impressionable years. This problem is, nevertheless, minimised by two factors. First, although individuals’ religious beliefs could potentially change later on in life, there is evidence that these, too, tend to settle and remain fairly stable after people reach their mid‐20s (Voas & Doebler Reference Voas and Doebler2011). Second, the main mechanism described in this article assumes that the political context during individuals’ impressionable years moderates the effect of religion on voting, and that this effect will remain visible for decades because political preferences tend to crystallise shortly thereafter. This moderating effect of the political context on religiosity, however, will not be observable with cross‐sectional data if religious beliefs change later on in life in a substantial manner but party preferences do not change accordingly (or vice versa). Therefore, measuring religiosity at the time when the survey was conducted can only lead to an underestimation of the influence of the political context during individuals’ formative years.

With regard to other independent variables, the models control for cohort‐level religiosity (measured as the mean of the religiosity index for each electoral cohort within each country) and the centre‐right's moral divergence at the last election. The purpose of the first control is capturing structural differences between generations (e.g., because religiosity might play a less important role in the electoral behaviour of individuals belonging to a very secular generation). The second control is introduced to capture the moderation effect of parties’ contemporary positions on moral issues on people's religiosity. Although the data do not allow for a proper test of short‐term changes (policy shifts) on moral issue policy positions, the introduction of this control will make sure that the effect of past policy positions during individuals’ impressionable years is not fully explained by parties’ current stances on moral issues. Other controls include individuals’ age (divided by 10, as otherwise coefficients were too small), left–right self‐placement (a 11‐point scale ranging from extreme left, 0, to extreme right, 10), gender (male = 0, female = 1), educational attainment (4‐point scale including primary education or less, lower secondary education, higher secondary education and tertiary education), urbanisation of respondents’ place of residence (village, town, city/suburbs) and a five‐category indicator of social class based on Oesch's (Reference Oesch2008) schema. Finally, denominational differences are captured by three dichotomous variables measuring whether individuals identify themselves as Roman Catholic, Protestant, Christian Orthodox, or none (the reference category).Footnote 12 Given the uneven distribution of denominations across countries and the different levels of religiosity across denominations, denominational effects are problematic to analyse in comparative research. Denomination is not an accurate indicator of religiosity in countries that are virtually monoreligious, and its use can lead to over‐estimating religiosity in countries with high levels of nominal affiliation (Evans & Northmore‐Ball Reference Evans, Northmore‐Ball, Fisher, Fieldhouse, Franklin, Gibson, Cantijoch and Wlezien2018). Moreover, as Stegmueller (Reference Stegmueller2013) shows, once the effect of religiosity and other variables is taken into account, the differences in party and issue preferences between denominations are much smaller than the differences between Christians and the non‐affiliated. Nevertheless, a control needs to be introduced to account for denominational differences in voting behaviour that are unrelated to individuals’ degree of religiosity.Footnote 13

In the ESS, individuals are nested within years (country–year combinations) and countries.Footnote 14 In addition, as the article focuses on a variable that varies with age, it must be taken into account that members of the same electoral cohort are more alike as they experience a similar political context.Footnote 15 Therefore, I estimate multilevel logistic regression models with random intercepts at four levels: individuals, cohorts, country–years and countries.Footnote 16 Modelling random effects in this way – a strategy adopted by other recent comparative research on the effect of the political context during individuals’ impressionable years (e.g., Dassonneville & McAllister Reference Dassonneville and McAllister2018) – is more flexible than using a cross‐classified model because it allows accounting for the fact that cohorts belonging to different national contexts cannot be assumed to be similar to each other. Nevertheless, I verified the robustness of results when (a) cross‐classified models are used instead, and (b) fixed effects, rather than random effects, are introduced to account for differences between periods and countries.

Findings

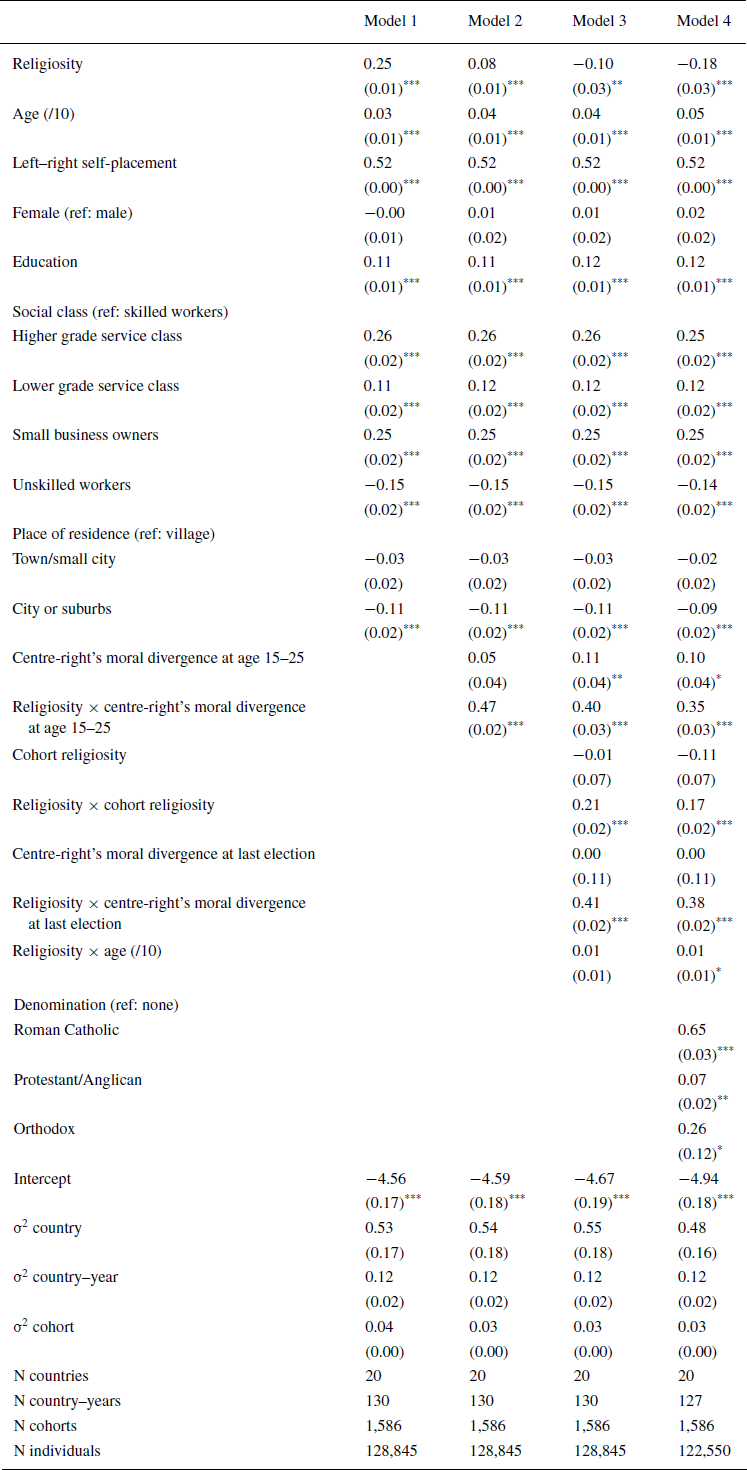

Table 2 shows the results of the main analysis. The first model (Model 1) introduces only variables measured at the individual level without any interactions and can be used as a benchmark against which the size of the effect of religiosity can be assessed. Consistent with previous research, results confirm the importance of religiosity for explaining electoral support for the centre‐right in Western Europe. The positive and statistically significant coefficient for religiosity reflects higher electoral support for centre‐right parties among more religious individuals. On average, a one‐standard deviation increase in religiosity leads to a 4‐percentage‐point increase in the probability to vote for centre‐right parties. With regard to control variables, the probability to vote for the centre‐right increases with educational attainment and, rather unsurprisingly, with right‐wing ideology, but decreases with urbanisation. Moreover, centre‐right parties are relatively more successful among small business owners and the services classes than among skilled and (particularly) unskilled workers. Also, there is no significant gender gap in voting.

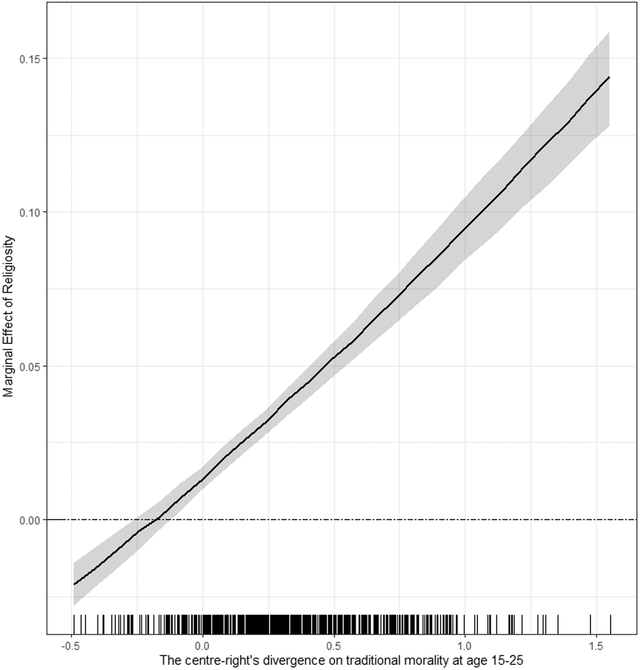

Model 2 introduces an interaction between religiosity and the centre‐right's divergence on traditional morality when individuals were aged between 15 and 25 years. As expected, the interaction is positive and significant, providing support for the main hypothesis of this article, which states that the impact of religiosity on vote choice will be stronger for those individuals who were socialised into politics at a time when the centre‐right adopted a more traditionalist position on moral issues than its average competitor. To better illustrate this finding, Figure 1 shows the effect of increasing religiosity by one standard deviation from the mean on the probability to vote for the main centre‐right party (y‐axis) across different levels of centre‐right parties’ moral divergence during individuals’ formative years (x‐axis).Footnote 17 As a reminder, ‘moral divergence’ is a relative measure that takes on positive values when the main centre‐right party was more traditionalist on moral issues than its average competitor, and negative values when the opposite was the case. Overall, religiosity increases the probability to vote for the centre‐right for every cohort – except for those socialised in contexts where the centre‐right was very liberal (negative values below −0.24 on the x‐axis), but these cases are extremely rare, as can be seen in the rug plot at the bottom of Figure 1. The effect of religiosity, however, is clearly stronger for cohorts who experienced a traditionalist centre‐right party when they were aged between 15 and 25 years. A religious individual (one standard deviation above the mean) socialised in a context of party convergence on moral issues (a value of 0 on the x‐axis) is about 1.3 percentage points more likely to vote for the centre‐right than an individual with an average level of religiosity socialised in the same context. For those socialised in a scenario of greater divergence on moral issues (a value of 0.73 on the x‐axis, which represents one standard deviation from the mean), the difference is 7.2 percentage points.Footnote 18 Considering that this is a long‐term mechanism, the effect is not small.Footnote 19

Figure 1. Effect of religiosity on the probability to vote for the mainstream right across different levels of the centre‐right's divergence on moral issues during individuals’ impressionable years.

Note: Shaded areas are 95 per cent confidence intervals. The rug plot at the bottom of the graph displays the distribution of the centre‐right's divergence on traditional morality at age 15–25.

Model 3 in Table 2 adds three controls: (a) an interaction between religiosity and the age of respondents to control for any possible age effects, (b) an interaction between respondents’ religiosity and the religiosity of their cohort in order to control for the impact of cohort‐level secularisation and (c) an interaction between respondents’ religiosity and the centre‐right's moral distinctiveness at the last election to control for contemporaneous effects of party positions. Results only show a small and statistically non‐significant moderating effect for age entailing a weaker impact of religiosity for younger individuals. In contrast, there is strong evidence that the effect of individuals’ own religiosity is even stronger for those belonging to more religious generations (as reflected by the significant interaction between religiosity and cohort‐level religiosity) and also in contexts where the centre‐right currently holds relatively more traditionalist positions on moral issues (as reflected by the significant interaction between religiosity and centre‐right's moral distinctiveness at the last election). More importantly, though, the coefficient for the interaction between religiosity and the centre‐right's divergence on moral issues during individuals’ impressionable years continues to be positive and significant when these controls are added. Results do not change either when denomination is added as a control (Model 4). As expected, Catholics, Protestants and Orthodox Christians are (in this order) more likely than non‐affiliated individuals to vote for the centre‐right. Overall, results demonstrate the importance of considering parties’ histories, as strategic decisions made in the past can have a lasting effect on individuals’ current vote choices.

Findings are robust to alternative model specifications (see the Appendix in the Supporting Information). In particular, the interaction between religiosity and parties’ stances on moral issues when individuals were aged between 15 and 25 years continues to be positive and statistically significant when (a) fixed effects rather than random effects are used to account for contextual variation (Model 3a in Table 2a, Appendix in the Supporting Information), (b) random effects are estimated using a cross‐classified random‐effects model with cohorts cross‐classified across surveys (country–year) and countries (Model 4a in Table 2a, Appendix in the Supporting Information) and (c) a random effects are estimated using a cross‐classified random‐effects model with separate cohorts by country (Model 5a in Table 2a, Appendix in the Supporting Information). Results are also robust to the introduction of cohort random effects for religiosity (Model 6a in Table 2a, Appendix in the Supporting Information), and to the use of alternative time windows for the ‘impressionable years’ such as 18–25 (Model 9a in Table 4a, Appendix in the Supporting Information) and 15–30 (Model 10a in Table 4a, Appendix in the Supporting Information). Conclusions also remain the same when Fianna Fáil rather than Fine Gael is defined as the main centre‐right party in Ireland (Model 11a in Table 5a, Appendix in the Supporting Information).

Table 2. Estimating the effect of party divergence of moral issues

Note: Coefficients and standard errors (in parentheses) of mixed‐effects logistic regression models shown.

***p < 0.001;

**p < 0.01;

*p < 0.05.

Conclusions

Support for West European centre‐right parties continues to be higher among religious voters than among their non‐religious counterparts in spite of secularisation, but research has shown the strength of this effect to be a function of parties’ strategic choices (Elff Reference Elff2009; Evans & de Graaf Reference Evans and Graaf2013b). When centre‐right parties have converged with other parties on issues related to traditional morality, the role of religiosity has diminished significantly. This article has now provided evidence that party convergence on moral issues, or the lack thereof, has a lasting influence on the way in which individuals use religious orientations to inform their vote choices. In particular, religious differences in party choice are significantly smaller among individuals who are exposed to a context of party convergence on traditional morality at 15–25 years of age.

The implications of this finding are manifold. In the first place, it lends further support to the idea that generational replacement is one of the main driving forces of electoral change, as the impact of the political context in which individuals are socialised during emerging adulthood is still visible several decades later. Furthermore, the mechanisms identified in this piece can help us to better understand the political consequences of the secularisation process in Western Europe. The shrinking number of religious voters in West European democracies led many to expect centre‐right parties to confront a dilemma similar to the one faced by the Social Democrats when the industrial working class waned in size as a result of the emergence of the service classes (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas1996, p. 241). In particular, the centre‐right was expected to adopt more liberal stances on moral issues in order to attract non‐religious voters, which would in turn lead to the decline of religious voting. Thus, the assumption was that structural changes would also entail behavioural changes in voters, but the picture has proved to be more complicated than that. This article sheds more light on this complicated picture because, while it emphasises the role played by political agency in shaping the strength of political cleavages, it also contributes to explaining why it sometimes takes time for the full effect of parties’ actions to be realised. Indeed, the explanatory potential of ‘top‐down’ approaches need not be limited to short‐term changes. We know that individuals respond to short‐term policy shifts, but electoral change cannot be fully understood without reference to longer term forces and generational replacement.

Even though research has found support for the centre‐right to have waned among younger religious voters in some elections and countries (Elff & Roßteutscher Reference Elff and Roßteutscher2017), overall the moderating effect of age found across West European countries in this article was very small once cohort differences were accounted for. This means that at least part of the effect of age may be related to relatively recent strategies enacted by centre‐right parties, which may have affected new religious voters but is unlikely to have had an enormous impact on those who have been supporting such parties for decades.

As is customary, it is worth mentioning some of the limitations of this study. An obvious limitation is that the analysis relies on repeated cross‐sectional data. Although this is the research strategy adopted by the overwhelming majority of cohort studies in the field of electoral behaviour (partly because longitudinal data going back several decades is only available for extremely few countries), future research is necessary to dig more into within‐individual differences, even if that entails focusing on a single country. Second, this article has focused on West European countries. Although the mechanisms explained here could equally apply to similar post‐industrial democracies, the dynamics of religious voting might nevertheless have followed a different path in most post‐communist countries, not least because traditional morality and religious issues in many of such countries have been actively used, and sometimes even ‘owned’, by parties other than the centre‐right (Raymond Reference Raymond2014). The particularities of these cases on both the demand‐ and the supply‐side make them particularly worthy of further exploration.

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by a Leverhulme Trust Research Fellowship. I would like to thank Luca Bernardi for his comments on an earlier version of this article and to all those who participated in the UoL Research Seminar where I first presented the ideas that led to this project. I am also grateful to four anonymous reviewers for their very useful suggestions, and to the journal editors, whose work is essential yet not always visible.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure 1a. Centre‐right's moral divergence across countries and over time.

Figure 2a. Effect of religiosity on the probability to vote for the main centre‐right party across different levels of centre‐right's divergence on moral issues during individuals’ impressionable years (estimation based on Model 4 in Table 2).

Table 1a. Robustness checks excluding pre‐1990 eastern German cohorts (Model 1a) and excluding all pre‐democratic cohorts in eastern Germany, Greece, Portugal and Spain and 1st Republic Italian cohorts (Model 2a)

Table 2a. Robustness checks with different cohort random‐effects specifications (replication based on Model 4, Table 1)

Table 3a. Robustness checks using different definitions of electoral cohorts to model the random effects (replication based on Model 4, Table 1)

Table 4a. Robustness checks using alternative definitions of the ‘impressionable years’ (replication based on Model 4, Table 1)

Table 5a. Replication of Model 4 in Table 1 using Fianna Fail rather than Fine Gail as the main centre‐right party in Ireland