Introduction

European integration has facilitated migration between countries. Free movement is a fundamental principle of the European Union (EU) that allows citizens of one member state to take up employment in any other member state. With the 2004 and 2007 eastern enlargement of the EU, this policy led to a substantial increase in EU‐internal migration and allowed many citizens of the new member states to find work and settle in the old member states to the West. Between 2013 and 2019, the number of Europeans from new member states living in old member states almost doubled, from 5.6 million to 8.9 million.Footnote 1

Researchers and policy advisors often discuss the effects of free movement within the EU on society and economy (Dixon, Reference Dixon2010; Kroh, Reference Kroh2005; Moravcsik & Vachudova, Reference Moravcsik and Vachudova2005). Most agree that it has overall positive economic effects,Footnote 2 but there are concerns about increased competition for jobs, working standards, misuse of welfare and difficulty in integrating cultures in the countries that receive the most migrants (see, e.g., Benton & Patuzzi, Reference Benton and Patuzzi2017). A major concern in these discussions is the possibility of public backlash to immigration in the receiving countries, which could lead to negative views of the EU and support for parties that are against the EU (Jeannet, Reference Jeannet2020a). Some scholars argue that migration within the EU played a significant role in the decision of the United Kingdom to leave the EU in the 2016 referendum (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley2017).

Existing research regarding the impact of immigration influx from new European Union member states on immigration concerns within established member states yields inconclusive findings. Studies have proposed various mechanisms that determine whether and how the increase in immigrant population affects opposition to immigration within the host country (for overviews, see Ceobanu & Escandell, Reference Ceobanu and Escandell2010; Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). One line of argumentation suggests that new arrivals may be perceived as a cultural and economic threat, leading to a decreasing support for immigration. Few studies have been able to rigorously demonstrate that these threat perceptions are triggered by increasing immigration levels and in turn lead to increasing concerns about immigration (for a synthesis of the literature, see Hainmueller & Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010). It has been suggested that concerns about immigration may only be fuelled under specific circumstances (for a recent meta‐study, see Pottie‐Sherman & Wilkes, Reference Pottie‐Sherman and Wilkes2017).Footnote 3 Given these inconsistencies in previous findings, it is unclear whether and to what extent the theoretical argument carries over to the context of intra‐EU migration (Markaki & Longhi, Reference Markaki and Longhi2013).

In fact, the specific circumstances of the EU eastern enlargement make it unlikely that the resulting influx of immigrants created an average attitudinal backlash. EU migrants are often well integrated into the labour market and are perceived as culturally similar. For example, Eastern and Central European male immigrants in Germany have high employment rates and are perceived as culturally proximate, leading to less negative stereotypes (see, e.g., Geis, Reference Geis2017; Kaasa et al., Reference Kaasa, Vadi and Varblane2016). Natives also often possess a European identity, which contributes to the perception of EU‐internal migrants as part of the European ‘in‐group' (Lutz et al., Reference Lutz, Kritzinger and Skirbekk2006). To what extent the specific conditions of the EU eastern enlargement play a role has not been thoroughly studied. As the only study, Jeannet (Reference Jeannet2020b) reports on a correlation between the presence of Central and Eastern European immigrants in Western EU countries and perceptions of immigration as an economic threat, but this correlation may be skewed by the non‐random selection of migrants in receiving countries.

Backlash can come from segments of the population who feel threatened by the cultural and economic changes brought by internal EU migration. Factors such as the value orientation and labour market position can play a significant role in moderating reactions to EU‐internal migration from the new member states. Cultural threat perceptions might be pronounced among parts of the population who hold materialist values. Individuals with materialist values have a need for individual safety and support traditional cultural norms, which can lead to an attitudinal backlash in light of an increasing number of immigrants from the new EU member states (see, e.g., Davidov & Meuleman, Reference Davidov and Meuleman2012; Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1977). Furthermore, parts of the working population can find themselves in labour market competition with the new immigrants and react negatively because of the inherent materialist threat from immigrants with similar skill levels (see, e.g., Borjas, Reference Borjas1999; Scheve & Slaughter, Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001). In how far these two aspects are relevant in conditioning the effect of an increasing influx of EU immigrants has not been empirically evaluated.

In this paper, we estimate the average and conditional causal effects of EU‐internal migration in the context of the 2004 and 2007 eastern enlargement of the EU on concerns about immigration in Germany. The EU's eastern enlargement increased internal migration considerably, and Germany is among the old member states that received a large share of migrants from the new EU member states.Footnote 4 To study how this affects concerns about immigration, we merge 20 years of county‐level register‐based annual immigration statistics on EU citizens with longitudinal survey data on individual attitudes from the Socio‐Economic Panel Study (SOEP). This creates a rich data source with fine‐grained regional data and repeated observations of the same respondents’ immigration attitudes. Furthermore, the increase in EU‐internal immigration is unevenly distributed across German counties. We take migrants' decisions on where to settle into account and use the gradual expansion of the freedom of movement policy combined with previously existing immigrant settlements to instrument the EU‐internal migration statistics. EU migrants from the new member states are particularly likely to settle in counties with existing ethnic networks, such that the increase in immigrants due to the loosening of immigration restrictions is unevenly distributed across counties. The research design based on instrumental variable estimation leverages this and provides rigorous evidence of how immigration as part of the European integration project has brought about changes in anti‐immigration attitudes.

Our results show that migration from new EU member states to Germany has unclear average effects on concerns about immigration. It aligns with the expectation that EU‐internal migration represents an unlikely case to exert average effects. We find support for conditional effects when investigating which part of society exhibits signs of backlash. The results indicate that especially natives with materialist‐survival values show signs of backlash and react negatively to increasing levels of immigrants from the new EU member states. This underlines that the perception of a cultural threat emanating from arriving immigrants is conditional on respondents' value systems. It is further the case that respondents with postmaterialist self‐expression values generally react less negatively to higher levels. We do not find evidence of an overall backlash to increasing levels among natives who are in stronger labour market competition with the arrivals from the new member states. The results still indicate that the labour market position conditions the effect, which hints at the potential role of economic threat perceptions. The effect on concerns about immigration among natives, who face labour market competition from newly arriving immigrants, is higher compared to their counterparts who do not face the same level of competition.

Our results reveal that EU enlargement and increasing EU‐internal migration have brought about a backlash in certain parts of the German population: those who subscribe to materialist‐survival values. EU migration policies, hence, have resulted in increasing polarization of the German population around migration issues, with certain parts reacting negatively due to their value orientations. In contrast to many existing empirical studies, the results of this paper are in line with theoretical expectations that the attitudinal backlash depends on individual characteristics in predictable ways. This highlights the importance of using appropriate designs to investigate the endogenous link between attitudes and immigration numbers. The results further align with the observation that, beginning in 2014, Germany experienced a considerable backlash against migration that took the form of increased support for the anti‐immigration and Eurosceptic political party Alternative for Germany (AfD). In this respect, our analysis contributes to the current debate on the rise of Eurosceptic movements and anti‐immigration sentiments in Europe.

EU internal migration and attitudes towards immigration

In the following section, we derive expectations about the effect of increasing levels of EU‐internal migration on attitudes. First, we describe general factors that influence attitudes towards immigration. Second, we describe the policies of free movement and the EU eastern enlargement. Third, we formulate expectations about average and conditional effects of EU‐internal migration on concerns about immigration.

Threat perceptions and attitudes towards immigration

The academic literature focuses on two threat perceptions that breed anti‐immigration attitudes. The first focuses on cultural aspects such as values, group identities and ideological views. The second studies economic self‐interest regarding increased competition in the labour market.

Research has consistently shown that cultural aspects shape immigration attitudes (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Hainmueller & Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2007; Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2005). Using data from the European Social Survey, Sides and Citrin (Reference Sides and Citrin2007) find that the desire for cultural homogeneity is a strong predictor of immigration attitudes. The idea that cultural homogeneity is an intrinsic factor in this is also a part of Card et al.'s Reference Card, Dustmann and Preston2012 study, which shows that immigration's impact on a country's culture and social life is a predictor of anti‐immigration attitudes. Experimental research by Sniderman et al. (Reference Sniderman, Peri, de Figueiredo and Piazza2002) highlights that out‐group categorization of immigrant groups plays a central role in this process. In this regard, cultural threat perceptions appear to be particularly important in understanding anti‐immigration attitudes (Enos, Reference Enos2014; Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004).

The economic self‐interest perspective argues that nationals of a country might oppose immigration due to the perceived threat of increased labour market competition from immigrants with similar skills (Freeman & Kessler, Reference Freeman and Kessler2008; Mayda, Reference Mayda2006; Scheve & Slaughter, Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001). A large body of empirical literature has failed to unambiguously answer whether perceptions of labour market competition drive anti‐immigrant sentiments. For instance, Markaki and Longhi (Reference Markaki and Longhi2013) find little empirical support for the hypothesis of conflict between equally qualified immigrants and natives. Ortega and Polavieja (Reference Ortega and Polavieja2009) point out the highly endogenous nature of the relationship between immigration numbers and anti‐immigrantion attitudes in ordinary cross‐sectional estimates. However, Naumann et al. (Reference Naumann, Stoetzer and Pietrantuono2018) present evidence from a survey experiment in Europe that challenges the labour market competition model (see also Hainmueller & Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010; Helbling & Kriesi, Reference Helbling and Kriesi2014). Some empirical work, nonetheless, confirms that the labour market can act as a consideration in situations where migrant workers substantially increase competition (Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Margalit and Mo2013).

An underlying corollary of both approaches is that the size and increase of the immigrant population should, ceteris paribus, increase group conflict and thus anti‐immigrantion attitudes in natives because rising immigration numbers either intensify competition on the labour market or fuel fears of an out‐group threatening cultural homogeneity. Some studies find empirical support for this hypothesis in longitudinal data (Heath & Richards, Reference Heath and Richards2016; Markaki and Longhi, Reference Markaki and Longhi2013; Schlueter & Wagner, Reference Schlueter and Wagner2008), but many studies find no or even inconsistent effects on anti‐immigration attitudes (Hjerm, Reference Hjerm2009; Hooghe & De Vroome, Reference Hooghe and De Vroome2015; Pettigrew & Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006; Rustenbach, Reference Rustenbach2010; Strabac & Listhaug, Reference Strabac and Listhaug2008; Van Oorschot & Uunk, Reference Van Oorschot and Uunk2007). In their meta‐analysis of existing research, Pottie‐Sherman and Wilkes (Reference Pottie‐Sherman and Wilkes2017) conclude that there is little support for the hypothesis that immigration numbers increase anti‐immigrant prejudice.

One initial explanation of the mixed results is purely methodological: Many of the studies mentioned above rely on observational longitudinal data analysis. One challenge with this type of analysis is that migration settlements are far from random (Ravenstein, Reference Ravenstein1885). In many countries, migrants can choose where they want to live and they tend to prefer places where they will be able to find a job and where people are likely to be more welcoming (see, e.g., Palmer & Pytlikova, Reference Palmer and Pytlikova2015; Tanis, Reference Tanis2018). Not taking these decisions into account can confound the figures on immigrants and anti‐immigration attitudes. If migrants settle mainly in pro‐immigration regions, a regression drawing on observational data would result in a downward bias in the relationship between the number of immigrants and the level of anti‐immigration attitudes, even if the rising numbers of immigrants trigger anti‐immigration attitudes.

Furthermore, two theoretical explanations have been put forward to explain this puzzling finding. The first line of argument is based on the so‐called contact hypothesis (Allport, Reference Allport1954), which states that increased personal interaction between two groups improves attitudes (for an overview, see Pettigrew & Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006). Personal interaction between natives and immigrants may reduce pre‐existing stereotypes and thereby decrease anti‐immigration attitudes (Enos, Reference Enos2014; Fetzer, Reference Fetzer2000; McLaren, Reference McLaren2003). A second line of argument is that contextual factors moderate the extent to which increased numbers of immigrants elicit negative attitudes in the public and see the portrayal of immigrant groups by parties and the mass media as a central moderating factor (e.g. Branton et al., Reference Branton, Cassese, Jones and Westerland2011; Hainmueller & Hangartner, Reference Hainmueller and Hangartner2013; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010).

Overall, the cultural homogeneity theory and labour market theory suggest that, first, noticeable increases in immigration numbers should increase concerns about immigration in the public. Second, the magnitude of the public response to immigration should depend on various factors, including people's economic position and their resulting vulnerability to changes in the labour market, and the extent to which they deem cultural homogeneity within their country an important policy goal.

Free movement of people, EU eastern enlargement and immigration

The free movement of people is an inherent value underlying the EU constitution and EU economic and labour market policies and is enshrined in multiple European treaties and council directives. It is one of the four economic freedoms that the EU guarantees, along with the free movement of goods, the free movement of capital and the freedom to establish and provide services. Together, these principles lead to strong labour market integration that allows EU workers to settle freely within the EU.

With the eastern enlargement of the EU in 2004 and 2007, EU‐internal migration increased considerably. The largest expansion of the EU took place in 2004, with eight Central and Eastern European countries (plus Cyprus and Malta) joining the EU. The old member states subsequently allowed the free movement of workers, with some member states introducing transitional restrictions up to 1 May 2011. In 2007, Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU, further increasing internal EU immigration from the new member states to the old member states. In our analysis below, we focus on Germany, which received a substantial share of new EU migrants. In 2018, net immigration to Germany was highest from Romania, Croatia, Bulgaria and Poland.

What do the fundamental aspects of anti‐immigration attitudes imply for EU eastern enlargement? On the one hand, the free movement of labour relates to classic theories of labour market competition, which postulate increasing hostility among parts of the population that see their labour market position as being threatened by newly arriving immigrants. If a large share of the population of the old member states faces such competition, we would expect an overall negative effect. On the other hand, the perspective of cultural value orientations relates to the cultural homogeneity of countries within the EU if free movement policies are in place. The implications here are less clear, as this depends on whether the newly arriving immigrants are perceived as part of the in‐group or an out‐group and thus a cultural threat.

At first glance, both aspects make EU eastern enlargement an unlikely case to find overall effects. EU immigrants from the new member states to Germany are generally well integrated into the labour market. Even though Central and Eastern European migrants hold lower qualifications than their Southern and Western European counterparts, they have high employment rates in Germany, particularly among men (Geis, Reference Geis2017). Moreover, EU‐internal migration can be described as immigration of people who are culturally proximate (Kaasa et al., Reference Kaasa, Vadi and Varblane2016). This means, for example, that Germans have less negative stereotypes about Polish immigrants than about immigrant groups from non‐European countries (Froehlich & Schulte, Reference Froehlich and Schulte2019). Additionally, many EU citizens embrace a European identity in addition to their national identity (Lutz et al., Reference Lutz, Kritzinger and Skirbekk2006), which may lead to EU migrants being perceived as part of the European ‘in‐group’ rather than the foreign ‘out‐group’. In some contexts, however, immigrants from the new member states have been portrayed as a cultural threat by right‐wing parties and media (Spigelman, Reference Spigelman2013). The overall conditions still lead us to formulate a null hypothesis that there is no average effect, due to the high levels of economic integration and perceived cultural proximity.

H0: Increasing levels of immigration in a local area does not affect concerns about immigration in the receiving country.

Only a few existing studies focus explicitly on the effect of increasing internal EU‐migration from new member states on anti‐immigration attitudes. Markaki and Longhi (Reference Markaki and Longhi2013) find that levels of immigration from EU countries do not relate to anti‐immigration attitudes, while levels of immigration from non‐EU countries do. The study does not distinguish, however, between new and old EU member states. Jeannet (Reference Jeannet2020b), in contrast, evaluates the effects of immigrant populations from new member states on public opinion in the old member states using longitudinal data. The findings suggest that the share of foreigners from new member states increases western Europeans' perceptions of immigration as an economic threat but provide little evidence that this increases the perception of immigration as a cultural threat. However, the analysis might be compromised by some of the aforementioned methodological issues, such as the active selection of migrants into more immigrant‐friendly countries. A study that takes migration selection into account is a working paper by Becker and Fetzer (Reference Becker and Fetzer2016). Becker and Fetzer study the increasing migration from eastern European countries to the United Kingdom after the 2004 enlargement of the EU. They find that support for the far‐right UKIP party increased in areas with large numbers of migrants from Eastern Europe. While this does not provide evidence of the effects on anti‐immigration attitudes per se, it still suggests the influx could have triggered anti‐immigration sentiments, which fed into increased support for anti‐immigrant parties (see also Barone et al., Reference Barone, D'Ignazio, de Blasio and Naticchioni2016; Halla et al., Reference Halla, Wagner and Zweimüller2017; Harmon, Reference Harmon2018). With this evidence that EU‐internal migration inflows can create negative public reactions, we formulate our first hypothesis:

H1: Increasing levels of immigration in a local area increase concerns about immigration in the receiving country.

Backlash in immigration attitudes among parts of the population

The attitudinal backlash against immigration might be stronger in the receiving countries among certain parts of the population.

A second set of hypotheses originates from the perception of cultural threat. Research on intercultural belief systems suggests that the ideal of cultural homogeneity develops as part of people's early socialization and finds expression in general trait‐like orientations. In their seminal work ‘The Authoritarian Personality’, Adorno et al. (Reference Adorno, Frenkel‐Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950) argued from a psychological perspective that attitudinal phenomena such as ethnocentrism and hierarchical thinking are elements of the more general personality traits of authoritarianism. Later psychological research has suggested similarly that ideologies of group‐based inequalities are rooted in a trait‐like social dominance orientation (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Sidanius, Kteily, Sheehy‐Skeffington, Pratto, Henkel, Foels and Stewart2015).

Whereas the concept of personality is used infrequently in the social sciences, human value orientations are often treated as omnibus and trait‐like constructs that inform more specific attitudes. Value orientations are relevant for anti‐immigration attitudes, as these attitudes can have consequences for ideals such as the ideal of cultural homogeneity (Sagiv & Schwartz, Reference Sagiv and Schwartz1995). Schwartz's understanding of human values (Reference Schwartz1994), which has been receiving increasing scholarly attention in recent years, has been used to examine anti‐immigration attitudes. The same is true for Inglehart and Welzel's (Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005) conceptualization of values. In a study referring to Schwartz's concept of human values, Davidov et al. (Reference Davidov, Meuleman, Billiet and Schmidt2008, p. 583) show that exclusionist attitudes towards migration are more widespread among individuals with conservation values. Inglehart and Welzel (Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005) argue that ethnocentrism is linked to (materialist) survival values and tolerance of foreigners to (postmaterialist) self‐expression values, two opposite poles of the value dimension.Footnote 5 In an early work on the topic, Inglehart (Reference Inglehart1977, p. 320) documents an association between materialism and anti‐immigrantion attitudes.

Inglehart (Reference Inglehart1977) argues that feelings of insecurity fuel parochialism and xenophobia in individuals who support materialist‐survival values. Materialism‐security orientations are related to needs for individual safety and support for traditional cultural norms. Contact with immigrants can result in insecurities about these needs, which are thereby a central source of xenophobia (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1977). Hence, we would expect that materialist‐survival values are positively related to anti‐immigration attitudes. Postmaterialist self‐expression values and the emphasis on higher needs such as freedom and tolerance can have a negative relationship to anti‐immigration attitudes.

The value orientation should particularly influence how people react to immigration inflows. An increasing number of immigrants should increase the relevance of certain pre‐existing values for immigration attitudes. If more immigrants settle in a region, people with certain values perceive a threat and place a stronger emphasis on this threat when developing their attitudes. We expect that people with materialist‐survival values and a need for security exhibit a stronger increase in concerns about immigration when the number of immigrants is increasing than individuals who are more tolerant of change and who hold postmaterialist self‐expression values. Based on this, we formulate a hypothesis on the conditional effect of increasing levels of immigration in our context:

H2: Increasing levels of immigration at the local level increase anti‐immigration views among individuals with materialist‐survival values.

The perspective also suggests that there is a difference in the way individuals react to increasing levels of immigration based on their value‐orientations:

H2a: Increasing levels of immigration at the local level increase concerns about immigration less strongly among individuals with postmaterialist self‐expression values, compared to individuals with materialist‐survival values.

In these hypotheses, the value trait takes the role of a moderator that is not influenced by increasing levels of immigration. This conceptualization is based on postmaterialism as a long‐standing value orientation developed during early socialization, with minimal changes over time (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1971) and supported by sibling studies (Kroh, Reference Kroh2009). Due to the perceived cultural proximity between migrants from Eastern Europe and natives, we expect this conditional effect to matter in the case of EU‐internal migration.

Our third set of hypotheses is rooted in the perspective of economic threat, in particular in labour market competition. The original models focused on labour competition among workers at different skill levels. Newly arriving immigrants increase the supply of ‘factors of production' (Borjas, Reference Borjas1999) in low‐ and high‐skilled labour markets, which puts natives under increased pressure for jobs. This implies that low‐skilled natives would prefer highly skilled immigrants and that highly skilled natives would prefer low‐skilled immigrants.

While the first economic argument posits a heterogeneous reaction based on the skill level of natives, empirical research has employed different measures of labour market competition with arriving immigrants. Earlier studies used education as a proxy for skill level (see, e.g., Helbling & Kriesi, Reference Helbling and Kriesi2014; Hainmueller & Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010), whereas later publications used the share of immigrants who work in the same occupation as natives (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hiscox and Margalit2015; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Margalit and Mo2013; Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Stoetzer and Pietrantuono2018), resulting in a more direct measure of increasing supply and labour market competition between natives and newly arriving immigrants. The labour market perspective leads us to the conditional Hypothesis 3:

H3: Increasing levels of immigration at the local level increase concerns about immigration among individuals who face labour market competition with the newly arriving immigrants.

Next to the hypothesis about the overall effect in the group of individuals who face labour market competition, the perspective also suggests that the reaction between individuals in low and high labour market competition differs in predictable ways.

H3a: Increasing levels of immigration at the local level increase concerns about immigration more strongly among individuals who face labour market competition, compared to individuals who face lower competition.

Due to the high economic integration of migrants from Eastern Europe, we expect this conditional effect to be important in the case of EU‐internal migration. Only under competition will natives show signs of backlash.

Research design

Enlargement of the European Union, 2004 and 2007

In 2004, 10 new countries joined the European Union: Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. The right to free movement in the EU would have automatically been extended to the new members, but with most of the new members having substantially lower GDP, concerns about high levels of East–West migration were part of the debate. This led to the introduction of transitional periods with restrictions on free movement for up to 7 years. Germany initially restricted free movement, requiring work permits and bilateral quotas, but gradually loosened the restrictions (with changes in 2006, 2009 and 2011), making it easier for people from the new member states to find work in Germany. Other member states such as the United Kingdom imposed no restrictions. By May 2011, the restrictions on these new members had been lifted across the EU. Romania and Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007, with another transitional period for implementing free movement, meaning that workers from these two countries did not have unrestricted access to the German labour market. In January 2014, Germany lifted all restrictions on workers from Bulgaria and Romania.

Even with the transitional periods, the number of people from new member states steadily increased as soon as these countries acceded in 2004. The number of immigrants from the new member states steadily increased (see Figure SM2 in the supplementary materials (SM)). The relative increase in the number of immigrants from new member states living in Germany in 2006, 2012 and 2015 is also notable, and it highlights the crucial role of the free movement policy.

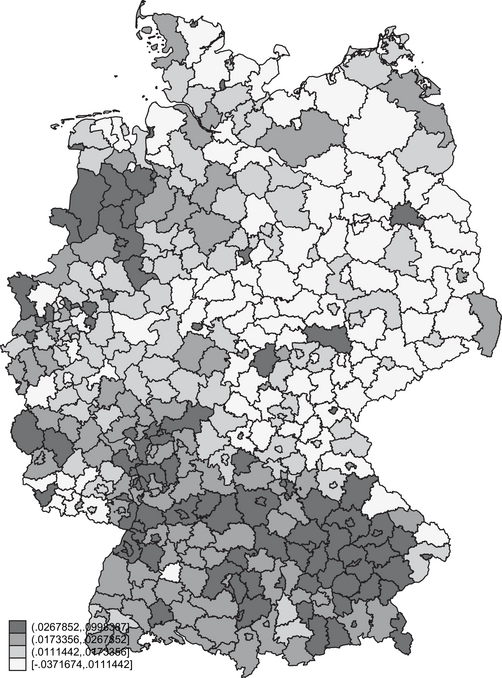

The geographical distribution in Figure 1 further highlights that most of the migrants from the new member states settled in the wealthy, industrial areas of Western Germany. The percentage point increase over the study period, from 2000 to 2019, is high around Munich, in the southwest and in West Germany. Figure SM4 in the SM shows that these patterns are comparable for 5‐year intervals. What is important, is that the patterns of settlement are not random. Migrants actively settled, for instance, in wealthy areas where they were likely to find jobs (Tanis, Reference Tanis2018). This underscores the importance of taking settling decisions into account when estimating the effect of increasing migration levels.

Figure 1. Increases of immigrants from the new member states from 2000 to 2019 in German counties, in percentage points.

SOEP data

We use data from the German SOEP (Goebel et al., Reference Goebel, Grabka, Liebig, Kroh, Richter, Schröder and Schupp2019). The SOEP is an ongoing annual representative survey of private households in the former East and West German states. We use the panel waves from 2000 to 2019 to cover the entire period from the accession of Eastern European countries to the end of restrictions on the free movement of labour. We limit the sample to respondents who were born in Germany, as the theoretical mechanisms apply primarily to natives.

We merge the SOEP data with official statistics on immigrant settlement patterns from the Federal Statistical Office (Statistische Bundesamt) and other regional information from the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (Bundesinstitut für Bau‐, Stadt‐ und Raumforschung, 2015) on the county level.Footnote 6 We combine the SOEP survey data with the official statistics from the previous year, as SOEP fieldwork starts at the beginning of each year. The SOEP data v37.1 include a total of around 749,221 interviews between 1984 and 2020, or between 10,000 and 33,000 in the different survey years. These interviews pertain to 105,287 adult respondents sampled in the original and refreshment samples representative of the residents of Germany (See SM A.1 for descriptive statistics).Footnote 7

The central dependent variable for our analysis is a question regarding concerns about immigration. It asks respondents how concerned they are about immigration to Germany on an ordinal level, ranging from very concerned to somewhat concerned to not concerned. To make it easier to interpret the results, we create our dependent variable as an indicator that a respondent is very concerned about immigration.Footnote 8 The share of immigrants from the new member states in a respondent's county is the main independent variable. The share of Central and Eastern European immigrants increases over time (see Figure SM6 in the SM). The mean value lies around 2 per cent with outliers as high as 8 per cent and 10 per cent (see Figure SM3 in the SM).

Of further importance is the measure of the two moderators in our analysis: labour market competition and materialist‐survival values. The share of immigrants from the new member states in the same occupation group as SOEP respondents serve as the indicator for labour market competition. To identify the occupation groups, we rely on the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) and Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community (NACE) codes in the SOEP and calculate the share of Central and Eastern Europeans working in these occupation groups from the German Microcensus of 2015. Based on this, we calculate a time‐invariant measure of labour competition in this year for each respondent. This measurement strategy extends recent publications in the field by creating a more fine‐grained measure that combines ISCO and NACE categories (see, e.g., Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hiscox and Margalit2015; Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Stoetzer and Pietrantuono2018). We rely on an index of materialist‐survival values versus postmaterialist self‐expression values available in the SOEP to capture the moderating role of values of cultural homogeneity. Since 1984, the SOEP includes a short version of the original postmaterialism measure proposed by Inglehart (Reference Inglehart1971). The question asks respondents to rank four policy goals. Based on respondent's ranking of materialist‐survival items (maintaining order in the nation, fighting rising prices) versus postmaterialist self‐expression items (giving people more say in government decisions, protecting freedom of speech), we construct a value index (see, e.g., Kroh, Reference Kroh2009). Our measure of the value index is time‐invariant and based on the SOEP wave from 2016. To simplify the interpretation of the effect estimates for the moderators, we split the values index and the labour market competition index into three categories: respondents with low values, middle values and high values. We also report on linear interaction effect models in the SM E.5.

Statistical model and causal identification

For the identification of the causal effect, we rely on a modelling strategy that combines fixed effects with instrumental variables regressions to identify the effect of immigration inflows on concerns about immigration. The panel structure permits us to control for unobserved factors that influence both concerns about immigration and the immigration level in a given county. Controlling for unobserved factors can be valuable, if respondents’ location in a county with varying levels of immigration is related to their immigration attitudes. For instance, anti‐immigration natives may choose to reside in areas with high cultural homogeneity and low immigration levels, while pro‐immigration natives may settle in cities with a high concentration of immigrants. Recent research confirms that this type of selection pattern matters (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2019). Fixed‐effects models control for unobserved confounding and are, thereby, able to address a shortcoming of comparative analysis of the impact of local migration levels (see, e.g., Ceobanu & Escandell, Reference Ceobanu and Escandell2010). The fixed effects model also controls for time‐constant individual confounders.

The fixed effects approach still has a shortcoming in our application: it does not take the settling decisions of newly arriving immigrants into account. If the locations where migrants choose to settle depend on past concerns about immigration within the population, this violates a central assumption of the fixed effects model that past outcomes should not influence treatment (Imai & Kim, Reference Imai and Kim2019). One possible way to address this is to condition county‐level controls (unemployment rate, GDP growth, educational attainment, etc.) that mimic the location decisions of immigrants (see, e.g., Quillian, Reference Quillian1995). An alternative is to turn to instrumental variables that induce exogenous variation in migration levels (see, e.g., Halla et al., Reference Halla, Wagner and Zweimüller2017). The instrumental variable approach is better suited to account for decisions about where immigrants settle but comes at the cost of increasing estimation uncertainty and a set of additional assumptions. To weigh the benefits and drawbacks, we present two model specifications: (a) fixed effects with county‐level controls and (b) fixed effects, county‐level controls plus instrumental variable estimation in our analysis.

As the instrumental variable, we rely on the gradual expansion of the freedom of movement for workers in the EU, which gives us exogenous variation that we can leverage. We use 2005 (accession of first 10 countries), 2011 (all resections for 10 member states lifted) and 2014 (all restrictions lifted) as the three steps that increased the number of eastern EU immigrants in the counties. The gradual expansion increased the overall number of immigrants in Germany, but it does not alone induce exogenous variation on the county level. For this, we rely on pre‐existing immigration settlements from the new member states in 1999 (prior to our study). We expect that immigrants tended to settle in places where immigrants from the same country had settled before. We create a categorical variable by splitting the share of immigrants from the new member states in 1999 into five, evenly sized, categories. The categories indicate counties with very low, low, medium, high and very high shares of prior settlements. The interaction between the categorical immigration settlements and the policy reforms represents the instrument. Research in economics uses similar instruments for regional immigration levels (Altonji & Card, Reference Altonji and Card1991; Cortes & Tessada, Reference Cortes and Tessada2011; Halla et al., Reference Halla, Wagner and Zweimüller2017). We discuss central assumptions (independence assumption, the exclusion restriction, instrument strength, and SUTVA) for the instrumental variables approach in detail in SM C.1.Footnote 9

We control for a set of observable variables, on the individual respondent level and the county level. On the respondent level, we control for age, marital status, education, occupational position, log household income, years of full‐time employment experience and unemployment experience in years.Footnote 10 On the county level, we control for the population size, migration balance, average age of the population, unemployment rate, long‐term unemployment, rate of unemployed foreigners, GDP per capita, mean household income, share with education entrance qualification, share of students and the net internal education migration. Our specifications also control for the share of immigrants from other countries, separating between the old EU member states and Schengen countries on the one hand and third countries on the other hand. In addition, we control for a linear time trend and the lagged dependent variable.Footnote 11 Finally, we report on clustered standard errors at the county level. As the share of immigrants from the new member states, the main dependent variable, varies at the county level, it is sensible to cluster the standard errors at this level, as ‘clusters of units, rather than units, are assigned to a treatment' (Abadie et al., Reference Abadie, Athey, Imbens and Wooldridge2017, p. 1).

Before we turn to the results, we evaluate the first‐stage estimates for the instrumental variable regression (For regression table and figure, see SM D.1). The instrumentation of the migration levels using the policy changes and the pre‐existing settlements patterns in 1999 seems to work as expected. Changes in free movement policies considerably increase the percentage of immigrants in a county, especially with prior immigration settlements. In a county with very low immigrant settlements in 1999, we estimate no clear increase with the lifting of restrictions in 2005 and 2011. For counties with medium, high and very high prior shares of immigration levels from the new member states, the increase is positive, especially for the 2011 and 2014 abolishment of restrictions. The immigration population in these countries rises significantly stronger with the policy reforms, compared to counties with low prior settlement. The first stage results, thereby, confirm the rationale that migrants tend to settle in regions with pre‐existing networks. It is important to note that this pattern exists even as we control other county aspects such as the GDP per capita, population density, other immigration levels, etc.

Results

The average effect of immigration inflows from new member states

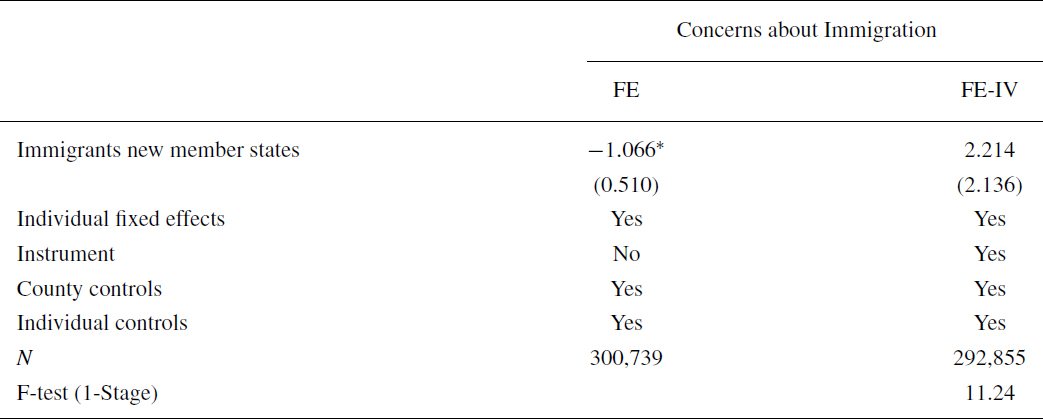

We first discuss the average effects on immigration concerns. Table 1 reports on the fixed effects (FE) and fixed effects instrumental variable (FE‐IV) estimates.Footnote 12

Table 1. Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member states on concerns about immigration

Note: Clustered standard errors by county in parentheses.

Abbreviations: FE, fixed effects; FE‐IV, fixed effects instrumental variable.

![]() $^{*}$

$^{*}$

![]() $p<0.05$,

$p<0.05$,

![]() $^{**}$

$^{**}$

![]() $p<0.01$,

$p<0.01$,

![]() $^{***}$

$^{***}$

![]() $p<0.001$.

$p<0.001$.

The results show opposing estimates from the two model specifications. For the FE estimation, the effect is negative (−1.066, standard error (s.e.) 0.510), suggesting that an increase in the level of immigrants from the new member states actually decreased concerns about immigration. The effect estimate is also statistically significantly different from zero, on a 5 per cent level. The effect estimate from the FE‐IV contrasts this. The estimate is positive (2.214, s.e. 2.136), implying an increase in concerns about immigration. The effect estimates would suggest a small, substantial increase: a one percentage point increase in the share of immigrants from the new member states living in a county increases the concerns of natives by 2.2 per cent points. However, the estimates here are not significantly different from zero on a 5 per cent level. One reason for the discrepancy may be confounding due to migrants’ decisions on where to settle. On the one hand, the FE model does not completely account for the fact that migrants tend to settle in areas with lower concerns about immigration, such as cities and economically prosperous regions. Not taking this into account may bias the estimate. The FE‐IV model induces exogenous variation in the settling patterns and thus produces estimates that are not plagued by this bias. The FE‐IV estimation, on the other hand, is more imprecise, resulting in larger standard errors.

Overall, the analysis here does not provide clear evidence that the increasing level of immigrants affects concerns about immigration on average. With the conflicting and ambiguous estimates, we can not clearly reject the Hypothesis (H0) that there is no effect of increasing immigration levels on concerns about migration at the county level. This aligns with previous mixed findings in the literature and our suggestion that the EU‐internal migration might be an unlikely case to find clear effects.

The conditional effects of immigration inflows from new member states

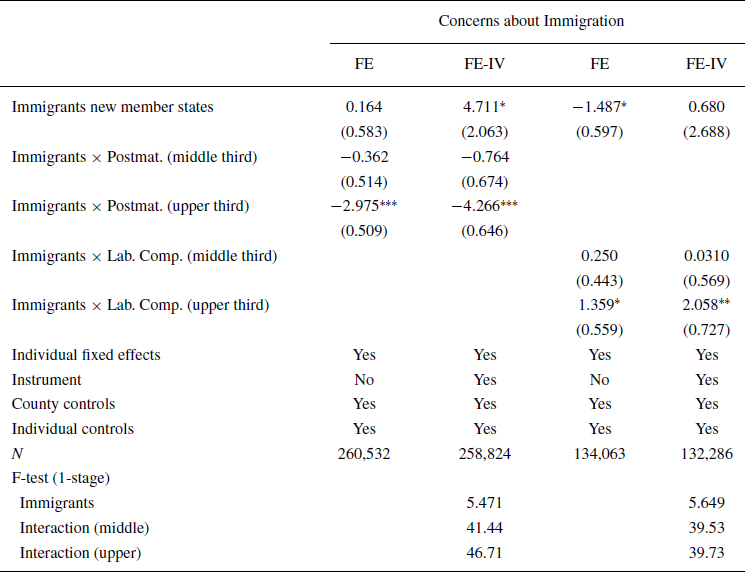

To evaluate our argument that part of the population responds differently, we test the conditional hypotheses. Table 2 presents the estimates from the fixed effects (FE) and instrumental variables (FE‐IV) models, with respective interaction effect terms.

Table 2. Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member states on concerns about immigration. Clustered standard errors are reported in parentheses. Models include interaction effects with postmaterialism and labour market competition index

Note: Clustered standard errors by county in parentheses.

Abbreviations: FE, fixed effects; FE‐IV, fixed effects instrumental variable.

![]() $^{*}$

$^{*}$

![]() $p<0.05$,

$p<0.05$,

![]() $^{**}$

$^{**}$

![]() $p<0.01$,

$p<0.01$,

![]() $^{***}$

$^{***}$

![]() $p<0.001$

$p<0.001$

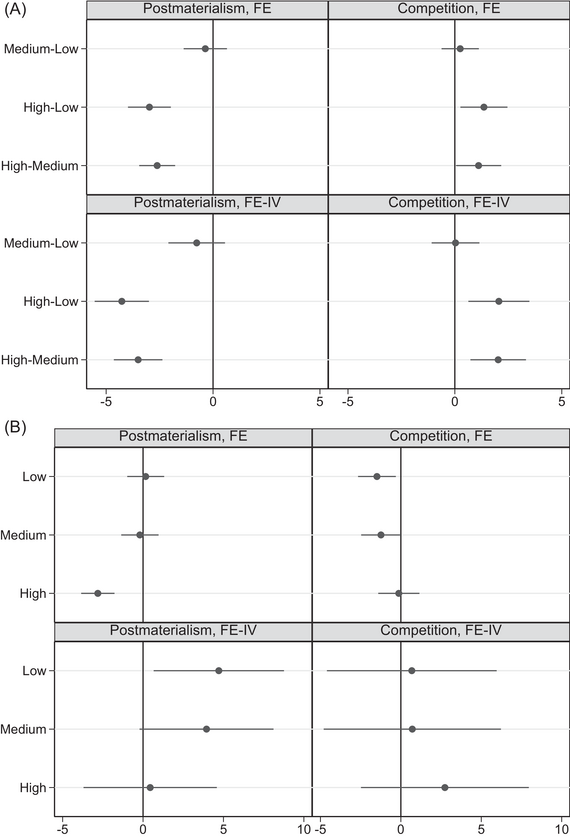

The value explanation helps in understanding the backlash against immigration. The first two columns of Table 2 show a negative and significant interaction effect with the upper third category of the postmaterialist‐self‐expression index, both for the FE (−2.975, s.e. 0.509) and the FE‐IV estimation (−4.266, s.e. 0.646). For the middle category of the postmaterialist‐self‐expression index, the estimate of the interaction effect term is negative, albeit not statistically significant. The direct effect, which pertains to respondents with materialist‐survival values, is positive in both specifications, but only significant for the FE‐IV specification (4.711, s.e. 2.063). The estimates imply two aspects. First, natives with strong postmaterialist self‐expression values react with lower increases in concerns about immigration due to increasing migration from the new member states. This supports the hypothesis about the comparison of groups with different value orientations (H2a). The left column of Figure 2A shows that for both specifications, individuals with high postmaterialist self‐expression values react less positively to increasing immigration levels. Second, this makes natives with materialist‐survival values a group for which we find evidence that they react with increasing concerns due to increasing immigration levels. The calculated marginal effects in the left column of Figure 2B reveal a significant positive effect for natives with low postmaterialist self‐expression values, in the FE‐IV estimation. Supporting H2, natives with materialist‐survival values react to higher levels of immigrants from the new member states with an increase in concerns. In substantive terms, a 1 per cent point increase in the level of immigrants from the new member states increases concerns by about 4.7 per cent points, among natives with materialist‐survival values. The results for the estimates from the FE model do not support this but are again potentially biased by the non‐random selection of migrants. Here, it is only the case that natives with postmaterialist self‐expression values significantly, respond to higher immigration levels with a decrease in concerns.

Figure 2. Moderating effect of postmaterialism and labour market competition on the effect of migration levels from new EU member states on concerns about migration. The figure shows the comparison of the effects and the marginal effects of immigration levels from new member states on concerns about immigration, conditional on categories (low, medium, high) of postmaterialist self‐expression and labour market competition, with 95 per cent confidence intervals. FE, fixed effects; FE‐IV, fixed effects instrumental variable.

There is also some support for the labour market competition explanation and the role of economic threat. The last two columns of Table 2 reveal a positive increase in the effect among respondents in professions with large numbers of immigrant workers from the new member states. The interaction effect with the upper third is positive, for both model specifications (FE: 1.359, s.e. 0.559; FE‐IV: 2.058, s.e. 0.728) which shows that higher labour market competition increases the effect of immigration levels on immigration concerns. These significant estimates imply support for the comparison between groups (H3a). Figure 2A shows that natives who are in labour market competition with the immigrants react with increasing concerns. However, when turning to the marginal effects, we observe no clear evidence for any of the subgroups. The right panel of Figure 2A reveals that the uncertainty in the FE‐IV estimation is too large to reject the null hypothesis that there is no effect among natives in high labour market competition. For the fixed effect models, none of the groups react with increasing concerns. Hence, there is no evidence to support H3.

Overall, the results support the hypothesis that the backlash against increasing immigration numbers comes from segments of society that hold materialist‐survival values. There is some support for the conditional impact based on labour market competition. However, it is clear that natives who are in competition with newly arriving workers react with backlash.

Additional analysis

We further evaluate the effects of immigration levels from the new member states on two related attitudes from the SOEP. First, a SOEP question on concerns about crime is related to the cultural explanation. Crime may be perceived as a threat to social cohesion and cultural traditions. Hence, the perception of immigrants as a cultural threat should be accompanied by increasing concerns about crime. Second, a SOEP question on job security maps onto the labour market competition explanation. Reduced support for immigration as a response to increasing labour market pressures should go hand in hand with increasing concerns about the individual job situation. SM E reports the results for the two outcomes. We find some additional confirmation for the value orientations explanation. Immigration levels have a positive effect on concerns about crime in the instrumental variable estimation, and the value orientations moderate the effect as expected. There is no support for the idea that job security is an intermediate concern, confirming the labour market competition perspective. The estimates are even negative and not moderated by labour market competition as expected. A potential explanation for the lack of evidence is that competition in the labour market may not result in job insecurity, but rather, elicit concerns regarding the effect of migration on salaries and wages. Conversely, the mechanism may be associated with the fiscal burden as labour competition could also be linked to competition for housing, social welfare or access to local services.

We conduct an additional analysis to evaluate the interaction effects when controlling for additional variables. One concern with the interaction effects could be that they are confounded by other relevant aspects. First, educated respondents face less severe labour market competition from newly arriving immigrants and hold more postmaterialist‐survival values. Second, different migration traditions in East and West Germany might trigger differential reactions. To control for this type of confounding, we include education and East interacted with the share of migrants from the new member states as a control. SM E.3 shows that the models estimated the expected interaction effect for value orientations, but not for labour market competition, again, accentuating the robust role of the value orientation, and the unclear evidence for the labour market competition.

Finally, we compare the estimates for the level of immigration from new member states to non‐EU and other Schengen countries in our analysis. This is relevant as the settling decisions of these different immigration groups might overlap. The estimates in SM D.2 show that only the level of non‐EU migrants is positively related to concerns about immigration. It underlines our suggestion that, in comparison, the effect of immigration from the new member states is an unlikely case to find effects. What matters more, it seems, is the share of non‐EU migrants. However, these results should not be overstated, as we do not propose identification for the effect of non‐EU migrants. For the immigrants from the new member states, our instrumental variable approach isolates the exogenous variation in the effect, even in cases where settlement patterns overlap with other groups. For the effect estimates of other immigration groups, we do not have an instrumental variable available.

Conclusion

The EU has been under attack, with right‐wing, anti‐European and anti‐immigration parties winning one electoral victory after the other and decreasing support for the European project. What role did the eastern enlargement of the EU and the free movement of people play in this development? In this paper, we show that the increasing number of immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe did not increase concerns about immigration in Germany on average. We find that the increase in concerns occurred mostly among people with materialist‐survival values, and argue that they see migration as a cultural threat. Also, we find some evidence that the labour market concerns that played a role in the policy debates around eastern enlargement conditioned the effect.

While the combination of county‐level and SOEP panel data enables methodological advances over cross‐sectional comparisons, a few limitations of the available measures should be acknowledged. The SOEP only includes a question on concerns about immigration in general, not about immigration from the new member states. It could undermine the interpretation that intra‐EU migration causes concerns about intra‐EU migration if this coincides with other migration flows. Furthermore, our analysis lacks a distinction between reactions to migrants from different countries and ethnicities. Further examination of these differences could offer insights into value‐based explanations. For example, Romani migrants may not be perceived as similar by German natives, leading to a different and broader backlash. Further research that differentiates these effects is crucial for a deeper understanding of EU‐internal migration's impact.

Furthermore, our empirical analysis identifies short‐term effects of increasing immigration levels from the new member states. We do not identify long‐term effects of increased migration levels. On the one hand, it is possible that the long‐term resistance may decrease due to factors such as personal interaction. On the other hand, some groups may still have persistent negative feelings. For example, the anti‐immigration stance of the AfD party may perpetuate cultural and economic fears, resulting in ongoing negative effects for certain groups in society.

The empirical results of this article do not directly address the question of how increased concerns about immigration may impact European politics. To address this question, it would be necessary to further study whether people with increased concerns about immigration turn to Eurosceptic parties, which often promote anti‐immigration policies. Previous studies have identified some effects on support for right‐wing parties and Eurosceptic attitudes (Becker & Fetzer, Reference Becker and Fetzer2016; Jeannet, Reference Jeannet2020a), but it remains questionable if the strengthening of anti‐immigration attitudes as a result of larger inflows of immigrants from new member states is the main channel for this.

The discussion might turn out to be relevant to other regional integration projects that also feature free‐movement policies. For example, the member states of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development recently agreed to promote the free movement of people. Our finding that increased migration resulting from such policies can create immigration attitudinal backlash among certain parts of the native population may be informative for debates around regional integration projects that intend to implement similar policies.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper have been presented at the ECPR General Conference 2020 and the ZEW Mannheim Workshop on Immigration, Integration and Attitudes 2020. We thank Jan Stuhler, Inés Calzada, Steffen Mau and Christian Albrekt Larsen and the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments and suggestions. Research for this contribution is part of the Cluster of Excellence ‘Contestations of the Liberal Script’ (EXC 2055, Project‐ID: 390715649), funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany's Excellence Strategy.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability statement

Data are subject to third‐party restrictions. The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the German Socio‐Economic Panel Study (SOEP, https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.core.v36eu), the German Microcensus, and the openly accessible database Indicators and Maps for Spatial and Urban Development (INKAR) provided by the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR). Restrictions apply to the availability of the SOEP and the German Microcensus, which were used under license agreements for this study. To access data from the SOEP, a license agreement must be obtained from the Research Data Center of the SOEP at the German Institute for Economic Research (FDZ‐SOEP). Similarly, access to German Microcensus data requires a license agreement with the Research Data Centre of the Federal Statistical Office (FDZ‐Bund) or the Statistical Offices of the Länder (FDZ‐Länder). The replication code necessary to reproduce the results of this study based on the data sources is available from the authors upon request.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table SM1: Number of respondents in our sample for SOEP survey years.

Table SM2: Descriptive statistics for the variables of the analysis from the SOEP sample.

Figure SM1: Number of observations over study period 2000‐2019 and the proportion of respondents that are very concerned about immigration.

Table SM3: County level statistics from INKAR for respondent observations in SOEP sample.

Figure SM2: Total number of immigrants from the new member states and the relative increase in Germany from 1999 to 2019.

Figure SM3: Distribution of the share of immigrants from new member states in counties in 2000 ‐2019.

Figure SM4: Increases of immigrants from the new member states between different time years, in percentage points.

Figure SM5: DAG for dynamic relationship between migration level in a county of the respondent

![]() $M_{kit}$ and concerns of

$M_{kit}$ and concerns of

![]() $Y_{it}$.

$Y_{it}$.

Figure SM6: Predicted increase in immigration population size from new member states based on five levels of original share of settlements of immigrants from new member states (in 1999).

Table SM4: First‐Stage regression estimates of share of original share of immigrants from new EU member‐states (5 categories) interacted with EU eastern enlargement policy on share of immigrants from new EU member‐states.

Table SM5: First‐Stage regression estimates of share of original share of immigrants from new EU member‐states (5 categories) interacted with EU eastern enlargement policy on share of immigrants from new EU member‐states for the three levels of the interaction effect model (Immigrants new member states, Immigrants X Postmat. (middle third), and Immigrants X Postmat. (upper third)).

Table SM6: First‐Stage regression estimates of share of original share of immigrants from new EU member‐states (5 categories) interacted with EU eastern enlargement policy on share of immigrants from new EU member‐states for the three levels of the interaction effect model (Immigrants new member states, Immigrants X Labour Competition (middle third), and Immigrants X Labour Competition (upper third)).

Table SM7: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about immigration.

Table SM8: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about immigration.

Table SM9: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about job security.

Table SM10: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about job security.

Table SM11: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of immigration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about crime.

Table SM12: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about crime.

Table SM13: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about immigration.

Table SM14: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about immigration.

Table SM15: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about immigration.

Figure SM7: Moderating effect of postmaterialism and labor market competition on the effect of migration levels from new EU member states on concerns about migration.

Table SM16: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about immigration.

Table SM17: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about immigration.

Table SM18: Fixed effect and instrumental variable estimates of the share of migration population in a county from new EU member‐states on concerns about immigration.