Introduction

The concept of “racial capitalism” is back with a vengeance—particularly in the American academy. But the term itself is not distinctively American, emerging as it did from debates surrounding anticolonial struggles in the 1970s. Hardly an academic matter, this concept was rooted in strategic debates across much of the colonial world: was it sufficient for movements to target colonial and apartheid racisms directly? Or conversely, were these outgrowths of particular models of capitalist development? Would targeting racism directly, in other words, adequately address its root causes? Or would antiracist struggles be treading water as the various fractions of capital supported a growth model anchored in a racialized division of labor, with violence deployed to lower the cost of Black labor-power?

This is one origin story of the concept of racial capitalism. More typically, commentators attribute the term to Cedric Robinson’s Reference Robinson1983 book Black Marxism—despite the fact that the concept only appears a half dozen times over the course of more than 300 pages. Unfortunately, many contemporary social scientists have begun to evacuate the term of its radical origins, citing Robinson whenever economic inequality appears to be racialized—as if “inequality” is what Robinson meant by capitalism, or as if Black Marxism were a book about the political economy of racialized accumulation. In this paper, we insist that Robinson engaged the term in the context of anticolonial strategic debates in Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere. But we focus our analysis on the development of these debates in one particular national context: South Africa. While these debates certainly occurred in a wide variety of national contexts, from the United States to Jamaica to Tanzania, nowhere were they as sustained as in South Africa, where they were central to the strategy of the anti-apartheid movement.

American academics are increasingly recognizing this fact. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor (Reference Taylor2022) insists that “we would be better served by going back to the development of the idea of racial capitalism, which was not in Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism, but in the Marxist tradition in South Africa” (p. 17). Nikhil Pal Singh (Reference Singh, Lye and Nealon2022) identifies South African debates as “[o]ne of the earliest uses of the concept,” and points out that Robinson had “an eye on the South African debates” while writing Black Marxism (p. 28). Peter James Hudson (Reference Hudson2017) highlights Robinson’s familiarity with the anti-apartheid movement, pointing to that body of thought as “another lineage…that predates Robinson” (p. 59). And Destin Jenkins and Justin Leroy (Reference Jenkins, Leroy, Jenkins and Leroy2021) argue similarly that “the term first cohered” in the anti-apartheid context and that these debates informed Robinson’s thinking (p. 4).

These claims are important starting points, but in this paper, we want to push a bit further. Singh (Reference Singh, Lye and Nealon2022), for example, describes the debate as one between the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), describing key theorist Neville Alexander as an ANC member. He was not. Meanwhile, the PAC was fairly marginal to these debates at the time. Jenkins and Leroy (Reference Jenkins, Leroy, Jenkins and Leroy2021) get closer, but they focus singularly on the term itself. As we argue here, the term was never central to the South African debates; it was the broader problematic of racial capitalism that mattered. Focusing only on the term and not on the wider debates it captures obscures some of the nuances in these discussions. Taylor (Reference Taylor2022) comes the closest of the bunch, rightly identifying the debates over racial capitalism with dissident Marxist responses to the South African Communist Party’s (SACP) understanding. SACP theorists believed that the fight against racism should be waged separately from the struggle against capitalism: first a “national democratic” stage and then the fight for socialism. By contrast, organizers from various independent radical formations—Trotskyist, Maoist, Black Consciousness, and many others—insisted that neither capitalism nor racism could be challenged independently; a successful strategy required taking them on simultaneously and in their specific contexts. This is why Hudson (Reference Hudson2017) can argue, much as we do in what follows, that “[w]hile the South Africans particularize, Robinson universalizes” (p. 62).Footnote 1

In this paper, we trace the development of the “racial capitalism” concept as it moved from South Africa to the United States and back again. We show that the term had two heydays, one in the 1970s and 1980s, and another following the 2008 crisis. While the first heyday centered on South Africa, we are not arguing that the origins of all thinking on racial capitalism must be routed through that country. As we demonstrate, radical academics were using the term simultaneously—and even earlier—elsewhere in Africa and in the United States. Rather, we are interested in how the broader problematic of racial capitalism took on a particular significance in the anti-apartheid movement—a significance that clearly resonated with debates in another settler colony: the United States. And these discussions, in turn, would impact South African disputes over racial capitalism in the post-apartheid period, a claim which we substantiate toward the end of this piece. Our central argument is that to make sense of racial capitalism, we must contend with three dialectics: between core and periphery, between activism and the academy, and between the term racial capitalism and the broader problematic to which it refers. We begin by elaborating these three dialectics and then show how they emerge within the lineage of thinking about racial capitalism: from the South African debates of the 1970s and 1980s to Robinson’s intervention in Black Marxism and, finally, to analyses of racial capitalism in post-apartheid South Africa.

Two Heydays, Three Dialectics

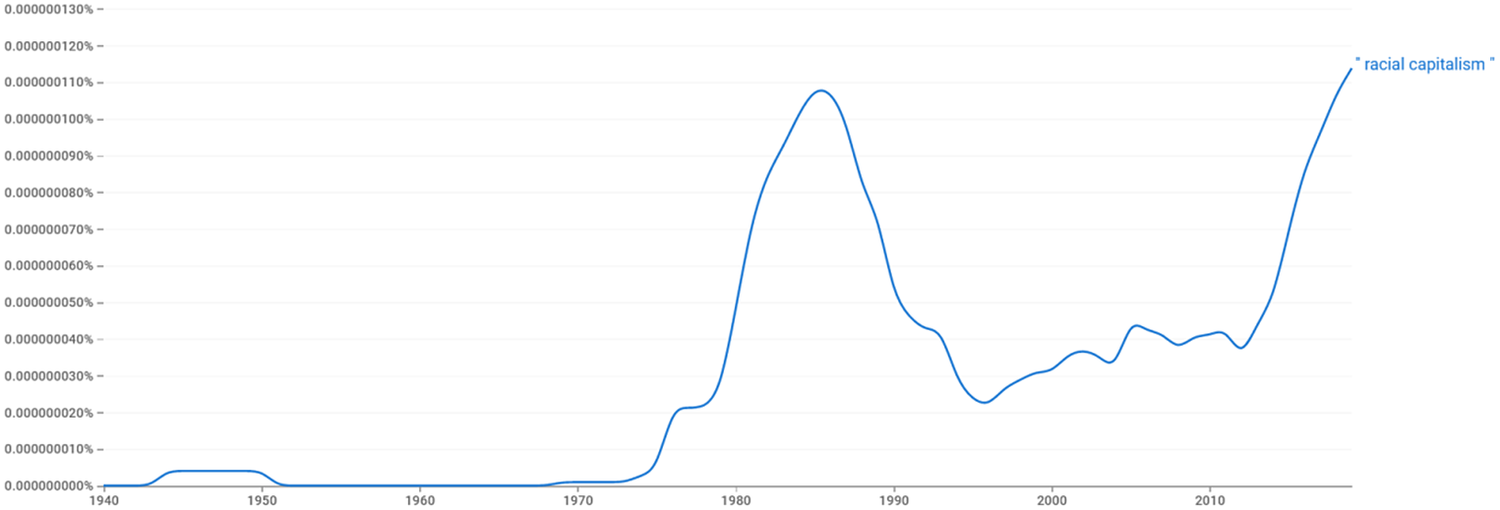

The current popularity of the concept “racial capitalism” risks overshadowing an earlier history, which of course predated the publication of Black Marxism. We do not need to choose between them, however; the term enjoyed two heydays. Most recently, beginning in the early 2010s, invocation of the term took off, surpassing any previous peak by the time the George Floyd uprisings in the United States were in full swing during the summer of 2020. This latest resurgence is often attributed to the reissuing of Cedric Robinson’s classic book Black Marxism in 2000, with a widely circulated foreword by Robin Kelley (Reference Kelley and Robinson2000). But as Figure 1 demonstrates, it would take another dozen years for the term to fully explode.

Fig. 1. Number of occurrences of the term “racial capitalism” in books, 1940–2020

This is because the concept has always been inseparable from struggle. And the 2010s were unquestionably a decade of upheaval following the 2008 financial crisis: from a smattering of anti-police brutality protests and anti-austerity struggles coalescing into the Occupy movement in 2011; to the Arab Spring proliferating across the Maghreb and western Asia; to militant protests in Lebanon, Sudan, Chile, and France; to the first wave of Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in 2014-2015, followed by a revived antifascist movement in the wake of Donald Trump’s election in 2016; to the International Women’s Strikes of 2017 and 2018, drawing inspiration from feminist struggles in Argentina; and, ultimately, the largest and most geographically extensive set of protests the United States has ever known: the BLM protests of 2020. It was in this context, we argue, that the term’s invocation truly took off. It was in trying to comprehend the apparent inextricability of two trajectories of struggle—one anti-capitalist, one anti-racist—that racial capitalism’s utility came into view. Were racist violence and worsening economic inequality just happening to coincide, or were they fundamentally linked? Calling attention to this question was precisely the utility of the term. Indeed, in the United States, explicit critiques of racial capitalism have been central to the BLM movement (Issar Reference Issar2021; Movement for Black Lives 2016; Ransby Reference Ransby2018).

Racial capitalism’s first heyday, spanning roughly the mid 1970s through the late 1980s (see Figure 1), was equally a time of struggle. This was the peak of the movement against apartheid in South Africa, which entered its most militant phase against the backdrop of successful independence movements across Lusophone Africa and ongoing anticolonial struggles in Southwest Africa (Namibia) and Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). In every one of these movements, activists came to understand colonial racism as inextricably linked to continued profitability, violently extracted and spirited away to the metropole. It is no coincidence, after all, that pan-Africanist and Marxist movements in many of these (anti)colonial contexts began to reach common ground in understanding colonial intransigence as a problem of racial capitalism. And it was in this context that the term took off, traveling back and forth across the Atlantic.

These linked geographies of racial capitalism mean that we need to take special care not to simply map each peak onto a different continent, a southern African 1970s followed by a distinctly American 2010s. Rather, we want to suggest that racial capitalism needs to be understood through the lens of three dialectics. First, even during its initial heyday, the term was hardly limited to southern Africa. Racial capitalism has always been characterized by a dialectic of center and periphery. The American sociologist Robert Blauner (Reference Blauner1972) invoked the term before it ever appeared in print in South Africa, and others in the U.S. academy came quite close to doing so. And after these debates came to prominence in South Africa, they quickly made their way abroad. For example, one of the key theorists of racial capitalism in South Africa, Neville Alexander, engaged with A. Sivanandan in the United Kingdom, the central figure in the circles in which Cedric Robinson would find himself in the late 1970s (Myers Reference Myers2021; cf. Kelley Reference Kelley2017). Other Black radical academics from the United States also took part in these British debates, including Manning Marable; it is no coincidence that his work from this period consistently references a “racist/capitalist state” (Marable Reference Marable1983). And it also must be remembered that many of the South Africans involved in these debates, not least among them Harold Wolpe and Martin Legassick, were themselves in exile in the United Kingdom during this period. When the term finally did find its way into Robinson’s Black Marxism in 1983, this was only after he had already published a pair of essays on the South African situation a few years before—including, as Peter James Hudson (Reference Hudson2017) points out, a reference to “apartheid capitalism.” Yet this was hardly his first engagement with southern Africa, ranging from a 1962 pan-Africanist trip that brought him to Rhodesia and elsewhere, about which he wrote a short essay (Al-Bulushi Reference Al-Bulushi2022), and subsequently during his time at SUNY Binghamton in the 1970s, where he worked with a number of Marxist Africanists (Al-Bulushi Reference Al-Bulushi2022; Myers Reference Myers2021). The point is that the term racial capitalism circulated across continents during racial capitalism’s first heyday, developing new meanings in each national context.

The same might be said for the current resurgence, what we are calling racial capitalism’s second heyday. Re-articulated, as the term was, in the context of largely American struggles, it quickly made its way back to South Africa, where student activists began to use the concept to make sense of the #FeesMustFall movement then catching fire on campuses across the country. Student activists looked to American theorists of racial capitalism like Robin Kelley, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Angela Davis, whose visits to South African campuses were notable events. Rather than mapping each heyday onto a specific geographical location, then, we want to suggest that this is the first dialectic of racial capitalism: the process of intellectual development as concepts and ideas move between and within societies, akin to what Said (Reference Said1982; cf. Burawoy Reference Burawoy, Burawoy and von Holdt2012) calls “traveling theory.” No singular location can contain these processes, which necessarily exceed their geographical bounds. But we also want to take great care to emphasize that this does not mean that an amorphous concept of racial capitalism enveloped the globe. Rather, it circulated across multiple concrete contexts, each shaping the significance of the term for particular forms of resistance. In other words, our analysis is necessarily conjunctural.

In addition to circulating across continents, racial capitalism also moved in and out of the academy. This is the second dialectic of racial capitalism: between strategic concepts forged in struggle and analytic concepts deployed by researchers. This recalls Antonio Gramsci’s (Reference Gramsci1971) famous quip, “All men are intellectuals … but not all men have in society the function of intellectuals,” which is particularly apropos to the field of racial capitalism studies (p. 9). In both the United States and South Africa, organizers have been at the forefront of thinking about articulations of racism and capitalism. From the South African Communist Party and the National Forum in South Africa, to the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, activists have theorized racial capitalism in relation to strategy. For many, it became a way to specify the target or enemy, the state of affairs to be challenged or overthrown. Not limited to an account of accumulation strategies, then, racial capitalism also encompasses a cartography of resistance—but a resistance inseparable from capital’s reliance on racial differentiation for the realization of profit. It should be no surprise, therefore, that the term proliferated during intense bursts of struggle.

Nor should it be surprising that discourses of resistance penetrated the academy. If activists proved to be among the most important thinkers about race and class, those who had “the function of intellectuals” were drawn into the movements of their day (Gramsci Reference Gramsci1971, p. 9). This was especially true in South Africa, where members of the academy were deeply engaged in and shaped by anti-apartheid struggles, giving rise to critical and liberation-oriented scholarship (Burawoy Reference Burawoy2004). It is telling that one of the earliest uses of the term racial capitalism (Legassick and Hemson, Reference Legassick and Hemson1976) came from the Marxist historian Martin Legassick, who remained a staunch supporter of liberation struggles as he moved through the academy in both South Africa and the United Kingdom. Indeed, Legassick and Hemson’s (Reference Legassick and Hemson1976) early reference to racial capitalism appeared in a brief oriented toward the broader anti-apartheid movement, urging activists to target racial capitalism’s support structures in the imperial metropole. Neville Alexander is a comparable case: a leading theorist of racial capitalism who earned his PhD abroad and taught at the University of Cape Town, but who developed many of his foundational ideas in the context of anti-apartheid organizations and spaces, not to mention apartheid prisons.

Similar processes unfolded in the United States. While many mistakenly assume Robinson’s Black Marxism to be a book about the political economy of racial capitalist regimes, they will search in vain for any such investigation; the book is rather a wide-ranging mapping of a Black radical tradition. Robinson himself was a student activist, and just a few years before the publication of Black Marxism he launched a radio program called the Third World News Review with student journalist Corey Dubin that “attracted a significant following beyond the academy” (Kelley Reference Kelley2016). They also worked with local activist Peter Shapiro, whose previous radio show was called South African Perspectives, and so would have been familiar with debates on the anti-apartheid left (Myers Reference Myers2021). In the United States today, the entanglements of activism and the academy are more widespread. The largely critical scholarship on racial capitalism reveals deep sympathies and engagements with ongoing anti-racist struggles. We thus find that leading thinkers on racial capitalism, such as Barbara Ransby (Reference Ransby2018), Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor (Reference Taylor2019, Reference Taylor2021), Beth Richie (Reference Richie2012), and Angela Davis (Reference Davis2016, Reference Davis, Dent, Meiners and Richie2022) are celebrated both in the academy and within activist circles. This blurring of the line between academic and activist intellectual work is reminiscent of the intellectual scene in apartheid South Africa.

Of course, plenty of South African activists and academics wrote about racial capitalism without actually invoking the term—much like Manning Marable in an American context as described above. As Andrew Nash (Reference Nash2009) puts the point, “racial capitalism” sums up “the thrust of an analysis of apartheid which was crucial for this generation” (p. 166). But this was an analysis that largely preceded the popularity of the term itself. In fact, the majority of contributions to the South African race/class debates of the 1970s and 1980s did not explicitly invoke the concept. This then is the third and final dialectic of racial capitalism: the dialectic between the concept itself and what Gaston Bachelard (Reference Bachelard2012 [1949]; see also Bourdieu et al., Reference Bourdieu, Chamboredon and Passeron1991 [1968]; Maniglier Reference Maniglier2012) famously called the wider problematic: the set of linked questions that define the scientific object. Most of the contributors to these debates in South Africa never deployed the term itself but were certainly debating the problematic of racial capitalism. We might say something comparable in a number of earlier national contexts, from W. E. B. Du Bois’s (Reference Du Bois1935) critique of planter reaction to Eric Williams’ (Reference Williams1944) account of racism’s emergence against the backdrop of British imperialism, and from Oliver Cox’s (Reference Cox1962) capitalist “racialism” to Hubert Harrison’s (Reference Harrison and Perry1911) “white capitalism,” or even Claudia Jones’ (Reference Jones and Davies1949) account of Black women’s “triply-oppressed status” under capitalism. The seeds of racial capitalism were sown, we might say, in the soil of the broader problematic, with the concept germinating in struggle. And it is precisely this tale of germination that we will now proceed to tell, weaving the three dialectics throughout the narrative.

The Origins of Racial Capitalism in Internal Colonialism

The term “racial capitalism” emerged in the 1970s. It became a point of departure for critiques of settler colonialism that moved back and forth across the Atlantic, especially among scholars and activists in the United States, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. While the analysis of the 1970s focused on the connections between race and capitalism in the United States and South Africa, one can also find early mentions of racial capitalism in places such as Namibia (Theodoropoulos Reference Theodoropoulos1978) and Kenya (Van Zwaneberg Reference Van Zwaneberg1974).

It is becoming commonplace to trace the origins of the term “racial capitalism” to South African debates about the relationship between apartheid and capitalism (Go Reference Go2021; Hudson Reference Hudson2017; Jenkins and Leroy, Reference Jenkins, Leroy, Jenkins and Leroy2021; Kelley Reference Kelley2017; Singh Reference Singh, Lye and Nealon2022; Taylor Reference Taylor2022). To our knowledge, however, the first usage of the term racial capitalism appears in Blauner’s Reference Blauner1972 book, Racial Oppression in America. As the title suggests, Blauner was primarily concerned with racial oppression, rather than capitalism. He famously characterized the United States as a situation of “internal colonialism,” in which Black communities were subject to ownership and control by external white forces: businesses, educators, police, social workers, politicians, and others (Blauner Reference Blauner1972, p. 82). Crucially, for Blauner, this dynamic of internal colonialism shaped the contours of popular resistance, namely the urban riots that were spreading across the country as well as demands for “community control” (Blauner Reference Blauner1972, p. 89).

This was a theory shaped by resistance. Notions of “domestic” or “internal” colonialism emerged in the 1960s in the context of Latin American dependency theory, as well as the emergent Black Power and Chicano movements (Gutierrez Reference Gutiérrez2004). Such origins reflected the global context and particularly identification of American activists with liberation struggles in the so-called “Third World”: “By studying national liberation struggles Blacks and Chicanos began to imagine themselves as oppressed nations that soon would be liberated through overt revolutionary struggle as part of the larger worldwide decolonization movements” (Gutierrez Reference Gutiérrez2004, p. 284). As a professor at Berkeley, Blauner was right next door to the Black Panther Party in Oakland, which was having its own heyday in the late 1960s. Indeed, in a footnote to his first article elaborating the internal colonialism argument, Blauner (Reference Blauner1969) acknowledges debts to Frantz Fanon, Stokely Carmichael, “and especially such contributors to the Black Panther Party (Oakland) newspaper,” from whom he derived much of his thinking (p. 393). Like racial capitalism, the idea of internal colonialism reflected the dialectics of both core-periphery and activism-academy.

With the internal colonialism framework, Blauner (Reference Blauner1972) aimed to improve upon what he viewed as flawed sociological approaches to race, focused as they were on assimilation, prejudice, economic reductionism, and a problematic analogy with European immigration. Yet, his turn to racial capitalism—itself more fleeting than central—reflected discomfort with what he viewed as his own insufficient attention to dynamics of capitalism and class. He hints, briefly, at the need for a more totalizing framework that brings together “colonial theory” and “Marxist models of capitalism” (Blauner Reference Blauner1972, p. 13). This was necessary, he argued, because the United States was “clearly a mixed society that might be termed colonial capitalist or racial capitalist” (Blauner Reference Blauner1972, p. 13). Further, drawing a parallel between the United States and countries outside the West, he hoped that “[t]hird world militancy” might help to spark “political consciousness of the oppressive dynamics of racial capitalism,” which he understood as a “prerequisite for effective mass movements of social transformation” (Blauner Reference Blauner1972, p. 45).

A similar analysis emerged from the anti-apartheid opposition in South Africa, and particularly two of its most prominent movements, the African National Congress (ANC) and the South African Communist Party (SACP). Pushed into exile in the 1950s (SACP) and 1960s (ANC) by the apartheid state, the two organizations formally aligned with each other, and together they developed an armed militant organization called uMkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation). Parallel to Blauner’s internal colonialism thesis, they understood South Africa as “Colonialism of a Special Type” (CST): a situation of settler colonialism defined by the total merger of capitalist exploitation and racial domination, where white/colonizer/capitalist and Black/colonized/worker lived in the same society. Laying out this thesis in 1962, in a document titled The Road to South African Freedom, the SACP proposed that opposing CST required a two-stage transition, first to a national democratic society and second to socialism. The immediate goal of the first stage was “to unite all sections and classes of oppressed and democratic people for a national democratic revolution [NDR] to destroy White domination.”

The ANC officially adopted the goal of a National Democratic Revolution (NDR) in 1969, at its first conference in exile in Morogoro, Tanzania (Filatova Reference Filatova2012).Footnote 2 NDR became the guiding principle of the dominant wing of the national liberation movement, and also the ruling Alliance after the transition to democracy in 1994, including the ANC, the SACP, and the Congress of South African Trade Unions. The CST and NDR concepts, however, did not go uncontested. In the South African context, it was precisely from opponents of internal colonialism—critics of the ANC and the SACP—that the concept of racial capitalism took hold.

Racial Capitalism as Strategic Critique

Debate raged in and around South Africa about how to characterize the apartheid regime. The interventions were strategic, as different analyses of apartheid called for different approaches to resistance. Opponents of the dominant CST/NDR line of thinking associated with the ANC and SACP were especially critical of the two-stage approach, which effectively separated struggles against racism from struggles against capitalism. This critique emerged from two corners: white socialists with close ties to the academy, and a multi-racial group of socialists associated with the burgeoning Black Consciousness (BC) movement. We take each in turn.

Within the first camp, the celebrated scholar and activist Harold Wolpe famously rooted apartheid within the long-standing system of cheap labor. Wolpe (Reference Wolpe1972) argued that South Africa’s migrant labor system—in place well before apartheid—enabled low wages because non-capitalist economies in the rural areas, where workers returned periodically to their families, subsidized the costs of living and familial reproduction. The racist policies and practices of apartheid, then, represented an attempt to maintain the migrant labor system—and thus, cheap labor—despite the decline of rural economies, urbanization, and growing unrest. Wolpe was a loyal supporter of the ANC and the SACP, though he remained critical of their theories and programs. In a scathing critique of the internal colonialism thesis, Wolpe (Reference Wolpe, Oxhaal, Barnett and Booth1975) criticizes both Blauner and the SACP for failing to account for class relations, the mode of production, and the historically contingent relationship between class and race. Twenty years later, at the very beginning of the democratic era, Wolpe (Reference Wolpe1995) remained critical of the movement but never wavered in his political commitments (on the contradictions between Wolpe’s theory and practice, see Burawoy Reference Burawoy2004; Friedman Reference Friedman2015).

Though Wolpe is perhaps the best-known theorist of racial capitalism in South Africa, to our knowledge he never used the term. This was left to his colleague and sometimes collaborator, Martin Legassick (Legassick and Wolpe, Reference Martin and Wolpe1976). In 1976, Legassick and David Hemson, his comrade in the Marxist Workers Tendency of the ANC, published the pamphlet Foreign Investment and the Reproduction of Racial Capitalism in South Africa. For Legassick and Hemson (Reference Legassick and Hemson1976), racial capitalism in South Africa revolved around four key elements: 1) domination by foreign British capital, which shaped domestic policy; 2) racial divisions both between and within classes, including various fractions of white capital as well as white workers and Black workers; 3) official state policies of racial exclusion, including segregation and the migrant labor system, to facilitate capital accumulation; and finally, 4) racialized class struggle, including both the racially exclusive nationalism of white workers, and the various class forces within the national liberation movement. Their strategy for responding to racial capitalism was, in other words, rooted in international worker solidarity to improve the conditions of Black workers. By the late 1970s, other white academics and white student activists also began to use the term (Nupen Reference Nupen1978; Saul and Gelb, Reference Saul and Stephen1981; Webster Reference Webster1978).

The debates around how to characterize the relationship between racism and capitalism in South Africa was contentious, most crucially because these concepts were enmeshed in intense popular struggle marked by fierce differences over strategy and tactics. In October 1979, the UK-based Maoist journal Ikwezi: A Black Liberation Journal of South African and Southern African Political Analysis, published an essay on “Neo-Marxism and the Bogus Theory of ‘Racial Capitalism.’” It was an impassioned critique of the SACP, Wolpe, and especially the 1976 pamphlet by Legassick and Hemson. Anticipating Robinson’s (Reference Robinson1983) emphasis on racialism as precursor to capitalism, the polemic argues that “the contention that racialism is a creation of capitalism and can only be overthrown by a proletarian revolution is a load of shit” (Neo-Marxism 1979, p. 17). Debates also exploded within the ambit of the ANC and SACP. In the same year as the Ikwezi essay, Legassick, Hemson, Paula Ensor and Rob Peterson—all white South African socialists and members of the ANC—published a pamphlet, The Workers’ Movement, SACTU, and the ANC: A Struggle for Marxist Policies, seeking to convince the ANC to reorient towards socialist revolution (Friedman Reference Friedman2012). As Legassick (Reference Legassick, Webster and Pampallis2017) later recounted, they were not opposed to the CST’s theory of internal colonialism, but rather the conclusion that it demanded a two-stage transition. Instead, operating as part of the Marxist Workers Tendency (MWT), they drew from Trotsky’s theory of “permanent revolution” and pushed for working-class leadership within the national liberation movement. The pamphlet sparked their suspension and eventual expulsion from the ANC, though the MWT remained active.

The second camp, of socialists linked to the BC movement in various ways, was less tied to the academy and operated fully outside the ANC and SACP. A key figure was Neville Alexander, a Cape Town activist who spent a decade on Robben Island as a political prisoner, from 1964 to 1974. After his release from prison, Alexander (Reference Alexander1979) published a scathing critique of the national liberation movement for failure to adequately theorize the nation and racial/national difference. He took clear aim at the ANC and SACP for reinforcing racial/national divisions. Indeed, the “Congress” tradition within South Africa maintained divisions between “African” (African National Congress), Indian (South African Indian Congress), “Coloured” (Coloured People’s Congress), and white (Congress of Democrats) activists. Alexander also worried about class divisions within racial groups, and particularly the possibility that the Black middle class would facilitate the cooptation of the movement. He thus emphasized the need for working-class leadership of the national liberation struggle.

In the late 1970s, members of Alexander’s group constituted themselves as the National Liberation Front (NLF), though this remained a clandestine organization. But through participation in other political initiatives and independent trade unions, this circle began to associate with young activists from the BC movement—a political tendency completely distinct from the ANC/SACP alliance, led by the young activist Steve Biko. While the BC tradition emphasized racial domination and the centrality of a Black political subject, the movement increasingly incorporated ideas about class, capitalism, exploitation, and the need for socialism (Fatton Reference Fatton1986; Reddy Reference Reddy, Kagwanja and Kondlo2009). This fusion took place largely within the Azanian People’s Organization (AZAPO), founded in 1979 as a merger of various Black Consciousness organizations. In February 1983, Alexander participated in the fifth AZAPO national conference, and warned specifically of the dangers of racial capitalism:

The rulers of South Africa are faced with the most severe crisis that their system of racial capitalism has yet to contend with … the alliance with the white workers is to be downplayed in importance. Instead, the junior partners in the new alliance are to be the black middle class (Gibson Reference Gibson1988, p. 16, emphasis added).

At this very same conference, AZAPO called for the creation of the National Forum to help build a united front of forces against apartheid. Taking place in June 1983, the historic National Forum conference brought together 800 delegates from 200 different organizations (Gibson Reference Gibson1988, p. 14). On the last night of the conference, Alexander was tasked with drafting a public statement, drawing from the various resolutions submitted at the conference (Alexander Reference Alexander, Mngxitama, Alexander and Gibson2008). After some revisions, this statement became the Manifesto of the Azanian People, or the Azanian Manifesto. Representing a convergence of BC and socialist forces, the Azanian Manifesto identifies racial capitalism as the central problematic in South Africa:

Our struggle for national liberation is directed against the system of racial capitalism which holds the people of Azania in bondage for the benefit of the small minority of white capitalists and their allies, the white workers and the reactionary sections of the black middle class. The struggle against apartheid is no more than the point of departure for our liberation efforts. Apartheid will be eradicated with the system of racial capitalism (Alexander Reference Alexander, Mngxitama, Alexander and Gibson2008, p. 168).

This is probably the best-known reference to racial capitalism in South African history. At the second National Forum in 1984, there was some debate over the term “racial capitalism,” with some participants questioning the politics of the concept, insisting that it implied support for a non-racial capitalism. These critics wanted to see “the system of racial capitalism” changed to “the historically evolved system of racism and capitalism” (Gibson Reference Gibson1988, p. 15), though our understanding is that the delegates never formally altered the wording.

The National Forum represented one collective response to South African racial capitalism. The United Democratic Front (UDF), an umbrella of anti-apartheid organizations, was another. Both emerged in the context of increasingly vibrant and militant struggles, which reached new heights during the township uprisings of 1984-1986, as well as maneuvers by the apartheid state to divide and coopt popular resistance. Yet they had different emphases and political leanings. The UDF emphasized civil rights, democratization, and at its most radical, people’s power, national liberation, and white expulsion (Seekings Reference Seekings2000, pp. 6-8, 17-21). It also aligned with the ANC, and to a certain degree acted as a “front” for the exiled liberation movement. In contrast, the National Forum was increasingly critical of the ANC and the SACP, and stood for socialism and the overthrow of racial capitalism.

Black Marxism: Racial Capitalism Returns to the United States

It is in the broader context of these South African debates about apartheid, capitalism, and resistance strategy that Cedric Robinson (Reference Robinson1983) published the foundational Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Robinson does not pay much attention to South Africa or the ongoing debates taking place in that country in this foundational text, but he was certainly aware of them, as noted above.Footnote 3 Robinson’s usage of the term, however, differed sharply from his South African counterparts. In South Africa, scholars and activists used the term to identify a particular and historically specific configuration of capitalism and racial domination. In contrast, Robinson sought to develop a more generalized theory of capitalism, which for him has always been necessarily racial—all capitalism, in other words, is racial capitalism.

It is a bit curious that many have come to view Robinson as the founding theorist of racial capitalism, not only because of the earlier usages mentioned above, but also because he does not use the term very often. Nonetheless, Robinson does use the term in the title for the important first chapter of Black Marxism, which highlights the prevalence of racism and “racialism” within feudal Europe, prior to the emergence of capitalism. As a result, he argues, capitalism necessarily drew upon race:

The development, organization, and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions, so too did social ideology. As a material force, then, it could be expected that racialism would inevitably permeate the social structures emergent from capitalism. I have used the term “racial capitalism” to refer to this development and to the subsequent structure as a historical agency (Robinson Reference Robinson2000, p. 2).

As others have noted (e.g. Go Reference Go2021; Jenkins and Leroy Reference Jenkins, Leroy, Jenkins and Leroy2021), there is some ambiguity in Robinson’s analysis about the differences between race and other concepts, such as ethnicity and culture, as well as the role of capitalism in the origins of racial division. He remarks:

The bourgeoisie that led the development of capitalism were drawn from particular ethnic and cultural groups; the European proletariats and the mercenaries of the leading states from others; its peasants from still other cultures; and its slaves from entirely different worlds. The tendency of European civilization through capitalism was thus not to homogenize but to differentiate—to exaggerate regional, subcultural, and dialectical differences into “racial” ones (Robinson Reference Robinson2000, p. 26).

On the one hand, Robinson is suggesting that as the bourgeoisie and proletariat emerged in Europe, they tended to come from pre-existing ethno-racial groups. This racialized system of stratification, he insists, preexisted the emergence of capitalism and thus permeated it. As Robin Kelley (Reference Kelley2020) puts the point, “Capitalism emerged in Europe within a feudal system already built on racial hierarchy” (p. 17). On the other hand, Robinson implies that capitalism itself is what does the differentiating, transforming phenotypic, cultural, and linguistic difference into an immutable and biological conception of “race” rooted in eugenic hereditary descent, or what Sylvia Wynter (Reference Wynter, Hyatt and Nettleford1995) calls “a new status criterion of eugenicity” (p. 40). Thus, it remains unclear in Robinson whether race in its modern senseFootnote 4 was fully autonomous from and preexisted capitalism, or whether capitalism was the force that brought racism into being in the first place.

Despite these ambiguities, scholars have drawn on Robinson to underscore the close linkages between race, class, and processes of capitalist accumulation. The response to the original 1983 publication was lackluster. As Kelley notes in his foreword to the second edition of the book, “Black Marxism … garnered no major reviews and very little notice in scholarly publications. The few reviews it did receive were mainly from left-leaning publications or very specialized journals” (Robinson Reference Robinson2000, p. xviii). The 2000 reissue, however, may have helped to spark interest in the book, not the least due to Kelley’s glowing endorsement. Today, references to Robinson are obligatory in discussions of racial capitalism. The University of North Carolina Press published a third edition of Black Marxism in 2021 (Robinson Reference Robinson2021), and a biography of Robinson, Cedric Robinson: The Time of the Black Radical Tradition, was released the same year (Myers Reference Myers2021).

A group of American historians writing under the banner of the “New History of Capitalism” has fairly consistently drawn upon Robinson’s formulation, though not without reproducing some of the ambiguities we have identified in his work. Broadly construed, the project is to move beyond “Marxist theorizations that separate slavery and capitalism into antithetical modes of production,” instead thinking about the inextricability of racialized coercion and capital accumulation (Beckert and Rockman, Reference Beckert, Rockman, Beckert and Rockman2016, p. 9). But how to theorize the relationship between the two? This is where things get a bit more ambiguous. Walter Johnson (Reference Johnson2013) describes “the science of political economy, the practicalities of the cotton market, and the exigencies of racial domination [as] entangled with one another”—what he calls the problematic of “slave racial capitalism” (p. 14). But he refrains from specifying precisely how they are interrelated. Likewise, in more recent work, Johnson (Reference Johnson2020) invokes Robinson to argue that the very fact of racism and capitalism’s “combination” is “something unprecedented” (p. 6). The relationship between them is “intertwined,” which, much like being “entangled,” tells us that they are related but never specifies how. Similarly, for Jennifer Morgan (Reference Morgan2021), who also invokes Robinson, racial capitalism relates racism and profitability, but their precise relationship remains unspecified. She argues that racist practices of dehumanization explain the origin of value itself, but she also suggests that racism and profitability are “co-constituted,” that is, that they emerge in tandem (Morgan Reference Morgan2021, p. 10). As in Johnson, the precise mechanism through which racism and capital accumulation are articulated is left unstated. And when historians do make the mechanisms explicit, they can sometimes end up invoking Robinson to make a decidedly non-Robinsonian argument. So, for example, Kris Manjapra (Reference Manjapra, Beckert and Desan2018) cites Robinson to suggest a fundamental linkage between accumulation and “a racialized system of dispossession and exploitation, dehumanizing some groups for the material benefit of others” (p. 365). For him, “capitalism relies on racialized and gendered designations,” suggesting that racialization emerges because it is profitable and facilitates the expanded reproduction of capital (p. 365). This is, of course, a far cry from Robinson’s argument about racism preceding the birth of capitalism in medieval Europe.

Neoliberal Apartheid: Back to South Africa

With the recent resurgence of interest in racial capitalism, particularly in the United States, the term has been slowly making its way back to South Africa. One of the most significant contributions is Andy Clarno’s (Reference Clarno2017) Neoliberal Apartheid, which simultaneously brings the racial capitalism framework to bear on post-apartheid South Africa and draws a parallel with Palestine/Israel. Notably, Clarno emphasizes the importance of uniting an understanding of racial capitalism with the kindred concept of settler colonialism. The latter, he argues, emphasizes the trifecta of land, race, and the state: control of land via dispossession and settlement; the use of racial projects to dehumanize “native” populations; and the state as a “racialized structure of settler domination” that enables dispossession (Clarno Reference Clarno2017, p. 5). In South Africa, he suggests, it is crucial to make the connection between the colonial control of land (settler colonialism) and the exploitation of labor (racial capitalism). In doing so, Clarno hints at a possible reason for the resonance of racial capitalism in the United States and South Africa: their parallel histories of settler colonialism. He further suggests that a parallel history of settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel makes the concept of racial capitalism relevant in that context as well.

For Clarno, racial capitalism revolves around two interwoven processes: accumulation by dispossession and coercive labor, the latter of which may involve either exploitation or job exclusion and abandonment. Thus, “While white supremacy may intensify exploitation by devaluing Black labor, it can also generate ‘necropolitical’ projects that equate the security of the white population with the elimination of Black, indigenous, or other devalued populations” (Clarno Reference Clarno2017, p. 9). Within these processes, he argues, race is autonomous from but constitutive of capitalism, which operates through race. At its core, he suggests, is the way in which racial capitalism draws from processes of human differentiation: “capitalism consistently operates through racial projects that assign differential value to human life and labor” (Clarno Reference Clarno2017, p. 9). This idea comes from Gilmore (Reference Gilmore2007), who defines racism as the “state-sanctioned or extra-legal production and exploitation of group differentiated vulnerability to premature death,” (p. 28) and Clarno (Reference Clarno2017) adds that racialization attaches “symbolic differences” to “unequal power and value” (p. 209).Footnote 5

Like the earlier South African debates of the 1970s and 1980s, Clarno uses the notion of racial capitalism to illuminate historically specific configurations or articulations of race, class, and profit. He uses detailed ethnography in South Africa and Palestine/Israel to illuminate contemporary processes of securitization and racialized marginalization, which exclude the poor and contain them in slums, refugee camps, and informal settlements. More recent contributions place a similar emphasis on particular configurations of racial capitalism in contemporary South Africa: Erin Torkelson (Reference Torkelson2021) shows how predatory lenders subject “Coloured” cash transfer recipients to dispossession and debt, and Christopher Webb (Reference Webb2021) reveals how working-class Black students suffer from a “black tax” due to their obligations to support extended family members. For both Torkelson (Reference Torkelson2021) and Webb (Reference Webb2021), the racial component of post-apartheid racial capitalism stems primarily from legacies of racialized dispossession, exploitation, and domination. Despite the abolition of official state racism, contemporary realities reinforce longstanding racial inequalities.

Crucially, these interventions emerge from the North: Clarno, Torkelson, and Webb all completed their PhDs in the United States or Canada, and all three are currently based in North America or the United Kingdom. Back in South Africa, invocations of the term are scattered, but they are growing in number. Khwezi Mabasa (Reference Mabasa, Ndlovu-Gatsheni and Ndlovu2022) uses it to think through the co-constitution of Marxism and decolonial politics, straddling multiple approaches. Opening with a nod to Robinson, he suggests that colonial capitalism emerged as preexisting racism shaped the development of capitalism, though he soon pivots in two ways. First, he broadens the category of racism to include other modes of social differentiation; and second, he roots the emergence of colonial racism in the political economy of capitalism itself, drawing heavily on the work of Bernard Magubane, Williams, and Cox, among others. Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni’s (Reference Ndlovu-Gatsheni2020a) recent work likewise links racial capitalism to colonialism, defining the former as the central “economic extractive technology” of the latter (p. 190). The critique of racial capitalism, therefore, emerges at the “intersections of Marxism and decoloniality” (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Reference Ndlovu-Gatsheni2021, p. 50). As in Robinson, the emergence of Black insurgency should be understood in relation to the racial capitalist context of its emergence (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Reference Ndlovu-Gatsheni2021, p. 63), though elsewhere Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Reference Ndlovu-Gatsheni2020b) suggests that racial capitalism is a catchall for capitalism’s drive to differentiate populations, “creat[ing] a gendered, racialized, classified, and even ethnicized workforce”—and citing Robinson to make that point (p. 371).

Other South African writers straightforwardly invoke the term to signal the enemy: racialized profit-seeking. Mondli Hlatshwayo (Reference Hlatshwayo2018), for example, uses the term to capture the context in which workers must organize, pointing to the colonial history of its emergence. For him, racial capitalism is what workers struggle against. This is likewise the case for Kelly Gillespie and Leigh-Ann Naidoo (Reference Gillespie and Naidoo2019), who use racial capitalism to capture the trajectory of racialized accumulation in South Africa, from settler colonization through post-apartheid “nonracialism.” Above all, they use the term in the way it has long been used in South Africa, to explain how racism is a strategy to maintain profitability: “outsourced black workers, Marikana, the privatization of education at the moment of racial democratization, the black township itself” (Gillespie and Naidoo, Reference Gillespie and Naidoo2019, p. 235).

One thing to note about many of the invocations of racial capitalism in the context of post-apartheid struggles is that it is rarely developed as a central concept, instead providing the backdrop against which movements arise. But there is little attempt to resolve the ambiguity in Robinson: whether this is a preexisting racism that helps constitute capitalism, or whether racist differentiation is an effect of capitalism itself. The same is true in accounts of recent protests. Racial capitalism captures both the particularity of the post-apartheid political economy and potentially describes “the creation of an economy that favours white people over black people,” implying that racism shaped capitalism’s emergence in this context (Tshikota Reference Tshikota2021, p. 27). For Kristi Heather Kenyon and Tshepo Madlingosi (Reference Kenyon and Madlingosi2022), racial capitalism, as understood by student protesters, entails a two-front battle against both “white supremacy and socio-economic domination” (p. 7). Another account of student protests (Sooliman Reference Sooliman2019) relies on Nancy Leong’s (Reference Leong2013) definition of the term, which explicitly identifies racism as a strategy of profitability.

Against approaches that root racial capitalism in South Africa’s settler colonial trajectory of accumulation, Hylton White (Reference White2020) leans towards Robinson’s more generalized account of racial capitalism. He recounts the formative South African debates, particularly Wolpe (Reference Wolpe1972) and Alexander (Reference Alexander1979), but ultimately seeks a broader model that is not rooted in South African specificity. Building on Robinson (Reference Robinson2000), as well as Postone’s (Reference Postone, Postone and Santner2003) theory of antisemitism and Fanon’s (Reference Fanon1952) theory of antiblackness, White (Reference White2020) aims to link race and racism to the fetishized value forms of capitalist antagonism: antisemitism represents a reaction to the corruption of capital, while antiblackness is a reaction to the “biological energy” and “animal vigor” of labor. As with Robinson, these symbolic representations of and reactions to global capitalism reflect a racism that “transcends local histories of capitalist development” (White Reference White2020, p. 33). With White, then, we have come full circle, touching on specific South African debates but also, like Robinson, aspiring to global relevance and applicability. It is difficult to do both, and White leans towards the general. What is sacrificed in this account is the kind of fine-grained analysis of contemporary racial capitalism that is evident in those who describe the material conditions of racial capitalism on the ground in contemporary South Africa.

Conclusion

The analysis above traces the concept of racial capitalism through both of its heydays, one peaking in the 1970s and 1980s, the other emerging in the 2010s and continuing into the present. We argue that to understand these heydays in each respective global conjuncture, one must be aware of and account for three dialectics. The first dialectic, of core and periphery, refers to the way in which the concept and study of racial capitalism circulates across countries and contexts of struggle. We can see this in the way that the concept of racial capitalism, as well as kindred ideas such as internal colonialism, appears simultaneously in South Africa, the United States, and the United Kingdom, with thinkers drawing inspiration from one another. The second dialectic underscores the ways in which racial capitalism spills beyond institutional and movement boundaries, creating dialogues between, as well as within, the academy and activist circles. The two may be quite difficult to separate, especially during periods of heightened struggle as witnessed during both heydays of racial capitalism. Different analyses of racial capitalism have different strategic implications. Under apartheid, for example, the ANC, SACP, and Black Consciousness movement centered race in their analysis, whereas Black trade unions and the movements around Alexander and Legassick emphasized the importance of working-class leadership. Third and finally, the term itself, racial capitalism, could never contain the full breadth of thought concerning the articulations of racism and capitalism. The concept was always an intervention, simultaneously political and intellectual, into a larger field that was diverse and full of alternative interventions. This third dialectic, then, refers to the relationship between the term itself and this broader field, or what we have called its problematic.

Working through these three dialectics illuminates just how expansive the field of racial capitalism actually is. It is a field that extends well beyond any particular historical or geographic context, institutional or social domain, and even the very term itself. Trying to fit racial capitalism into a neat and tidy box, therefore, is a futile exercise and will likely produce distortions or misleading conclusions. It also follows that we have only reached the tip of the iceberg in our account here. There is certainly much more to explore, whether in terms of other countries or regions such as Asia, Latin America, and the rest of Africa; the countless thinkers who have touched on related ideas; or otherwise. One of our primary contributions in this paper is to provide a deeper look into the South African debates around racial capitalism than one can find in most contemporary accounts, despite some acknowledgment of South Africa’s importance to the field. Even here, though, there is a great deal more to explore in the rich South African history of thought. Ours is quite far from a complete story, and indeed, part of our work on racial capitalism moving forward will be to deepen our engagement with South African debates, theorizing, and political strategy.

These limits notwithstanding, our brief tour of racial capitalism’s two heydays and three dialectics points to productive questions and lines of inquiry. One set of questions revolves around the association between racism and profitability, which has been central to both South African debates and the country’s historical trajectory. Foundational work on racial capitalism pointed to the ways in which apartheid racism secured profits, especially for mining and finance capital. At the same time, it was the growing tension between apartheid racism and profitability—the former sparked resistance and instability, which undermined the latter—that helped to usher in South Africa’s democratic transition. Should we still consider racism as essential to the South African accumulation model? Even after the demise of apartheid, of course, inequality remains absolutely racialized, as do labor markets. How should we make sense of this fact nearly thirty years after the demise of apartheid? And what work does racism do today to (re)produce inequality? As Gilmore (Reference Gilmore, Johnson and Lubin2017) famously argues, “Capitalism requires inequality, and racism enshrines it” (p. 240). How precisely then does racism achieve this enshrining? As the popularity of racial capitalism continues to explode globally, we urge activists, academics, and other writers to take the term seriously. “Racial” should not be tacked onto “capitalism” simply because two is better than one, but because the concept can do analytic work. We must demonstrate how it is that racism continues to enshrine inequality, and how this distinctly capitalist mode of differentiation works to augment profitability. Only then do we have any hope of challenging it.

A distinctive feature of the South African writing on racial capitalism, particularly in accounts of migrant labor under apartheid, is the emphasis on the reproduction of labor power. This was central to Wolpe’s (Reference Wolpe1972) classic analysis of apartheid as a cheap labor system, and also laid the foundation for Alexander’s (Reference Alexander1979) analysis of race and working-class formation. Such formulations began to move beyond tidy oppositions between land and labor, settler colonialism and exploitation. The emphasis on reproduction showed that both were crucial: land grabs provided sites of reproduction to lower labor costs, directly linking the settler colonial project to the pursuit of exploitation. What mattered, in other words, were specific articulations of land, labor, and livelihood in particular historical contexts.Footnote 6 Extending such ideas, and keeping in mind the mechanisms that link racism and profitability, we might consider how racism enables—or even generates—the stratification of the labor force into those surviving on wages alone and those forced to supplement their wages (a semi-proletariat). Or we might look instead at how racial capitalism operates at the point of consumption, such as through what Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor (Reference Taylor2019) has called “predatory inclusion,” securing land values for the real estate industry at the expense of livelihood for the Black working class.

These considerations bring us to a final set of questions around the general and the particular. We have been careful to situate thinking about racial capitalism in particular historical contexts, which is crucial given the close connection between the field and concrete struggles. In South Africa, attention to racial capitalism in the 1970s represented a response to, and an attempt to think through, an historically specific and geographically contained political economy. It is perhaps ironic, then, that so many current South African thinkers have turned to Robinson, who instead posits a much more general, transhistorical, and geographically wide-reaching racial capitalism. Such generalized accounts of racial capitalism tend to run against Stuart Hall’s (Reference Hall and Morley1980) warning that “[r]acism is not present, in the same form or degree, in all capitalist formations: it is not necessary to the concrete functioning of all capitalisms” (p. 213). It is perhaps worth noting that this warning appears in a paper in which Hall seriously engages South African debates. The trajectory of thinking about racial capitalism across the two heydays thus leaves us with a number of questions about its specificity or generality. Should we be concerned with a globally dispersed racism, or else with geographically specific racisms? A transhistorical racism or a variety of racisms, each tied to particular capitalisms?

In sum, the two heydays and three dialectics do not represent any satisfying conclusion about racial capitalism. They are, rather, a point of departure. As South African thinkers teach us, we must think about analytic concepts and strategy as two sides of the same coin. And to do this effectively, our analysis must remain conjunctural, relational, and above all, global and internationalist. Only then can we understand the circulation of this deceptively stable concept across multiple political contexts.

Acknowledgements

In addition to both anonymous reviewers, whose feedback was incredibly helpful, we would also like to extend a special thanks to Salim Vally, whose meticulous fact-checking on some of the debates recounted here saved us from obvious embarrassment. We presented the paper, and received valuable feedback, at the American Sociological Association’s annual meeting (Los Angeles, 2022) and the Marx and Philosophy Society’s “Marx and Race” conference (London, 2022).