1 Introduction

This study is situated within the framework of Talmy’s motion typology (Reference Talmy and Shopen1985) and Slobin’s (Reference Slobin, Sven and Verhoeven2004) following expansion, which classify languages based on how they encode path of motion in motion events. Path refers to the trajectory or direction followed by the figure during the motion, and manner describes how the figure moves, detailing qualities intrinsically linked to the figure’s properties, such as speed, style, or method of movement (Talmy, Reference Talmy2000, p. 25). Satellite-framed languages (S-framed), such as English, typically encode the path of motion outside the main verb in satellites such as particles or prepositions, while the manner of motion is usually encoded in the verb. Verb-framed languages (V-framed), such as Spanish, often encode the path of motion in the verb, often omitting the manner or expressing it through adjuncts. Equipollently framed languages (E-framed), such as Chinese, usually encode both the path and manner of motion in serial verbs of equal status. For the ‘thinking-for-translating’ hypothesis (Slobin, Reference Slobin, Ravid and Shyldkrot2005), these typological differences between source and target languages would impact the translators’ cognitive processing of motion information.

For example, a study of English–Spanish translation has shown that manner information is frequently omitted when translating from English to Spanish but is often retained or even added when translating from Spanish to English (Cifuentes-Férez & Molés-Cases, Reference Cifuentes-Férez and Molés-Cases2020, p. 93). While research on manner encoding in translation is well-established, the investigation of manner expressions in interpreting under high cognitive load remains less explored. An exception is a recent study adopting an onomasiological approach to cross-domain manner encoding in simultaneous interpreting (SI) (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024); the findings of which also suggest more effective manner processing when translating into English. The aim of this study is to replicate the approach outlined in this previous work (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024) and address existing research gaps in several areas.

Firstly, while research on manner encoding has been explored in SI, consecutive interpreting (CI) remains under-researched despite its generally higher cognitive demands (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Fang, Lv and Liu2017; Lv & Liang, Reference Lv and Liang2019). Secondly, this study will implement a more refined control of task-related, environment-related and interpreter-related factors that influence cognitive load. This includes managing task difficulty by assigning the same task to multiple interpreters under consistent interpreting conditions and ensuring that all participants share a similar bilingual profile, with Chinese as their first language. Such an approach allows for further testing of whether interpreters with similar linguistic backgrounds and cognitive loads could process and convey manner information more efficiently when interpreting into a S-framed language (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024, p. 26).

Thirdly, there is a notable gap concerning E-framed languages. Chinese, which is classified as an E-framed language (Chen & Guo, Reference Chen and Guo2009), has been rarely addressed in research on manner expressions in high-cognitive-load interpreting. Fourthly, while the use of speech rate serves as an indirect indicator of cognitive load (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024, p. 25), the use of other measures, such as performance-based indicators, may be also effective to assess cognitive demand (Paas et al., Reference Paas, Tuovinen, Tabbers and Van Gerven2003; Seeber, Reference Seeber2013).

This study, therefore, aims to analyse how typological differences, operationalized with directionality, and cognitive load, as reflected in interpreting performance, impact the cognitive processing of manner information in CI between an E-framed language (Chinese) and an S-framed language (English). The research will examine the diversity of manner encoding under varying cognitive loads (§4.1, §6.1, §7.1), explore the effects of typological differences on manner transfer (§4.2, §6.2, §7.2), the impact of cognitive load on manner processing (§4.3, §6.3, §7.3), and investigate how typological differences affect the resistance to cognitive load in the processing of manner information (§4.4, §6.4, §7.4).

Section 2 introduces an onomasiological approach to manner analysis, setting the analytical framework for the study. In Section 3, the magnitude of cognitive load in CI is discussed, along with the factors that influence it and the methods used to measure it. Section 4 outlines the hypotheses on manner processing, directionality and cognitive load. Methodology is detailed in Section 5, where the corpus data and the coding principles applied for analysis are described. Sections 6 and 7 present and discuss the results for each of the four hypotheses. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper by summarizing the main findings, their implications and suggesting directions for future research.

2 An onomasiological approach to manner analysis

Manner has been more commonly conceptualized as an optional ‘co-event’ that can be expressed alongside the primary components of spatial events such as path and ground (Talmy, Reference Talmy2000). A precise definition of manner, however, has been generally absent in the literature, leaving the term conceptually vague (Slobin, Reference Slobin, Sven and Verhoeven2004). Recent research suggests that manner could be a structuring element in various conceptual domains (Stosic, Reference Stosic2020), and a detailed framework for manner as a cluster concept has been proposed to enable a corpus-based analysis of manner in semantic contexts beyond those centred on motion.

In this framework, manner is defined as ‘an operator of diversification of actions, states and qualities, whose role is to stress the way a given occurrence of these three kinds of entities is qualitatively distinguishable from both their prototypical and their other possible instantiations’ (Stosic, Reference Stosic2020, p. 32). Manner is thus viewed as a cluster concept and a two-level concept operating at different levels of abstraction (Stosic, Reference Stosic2020, p. 32). This study builds on this onomasiological approach to manner analysis (Stosic, Reference Stosic2020) and provides an overview of the framework.

Onomasiology generally refers to the branch of linguistics focused on how concepts or referents are named (Fernández-Domínguez, Reference Fernández-Domínguez and Mark2019, p. 1), and onomasiological models usually focus on how a concept or meaning is expressed in different linguistic forms. As demonstrated by Stosic (Reference Stosic2020, p. 20), this approach recognizes the variety of linguistic devices, including verbs and adjuncts, that can be used to encode the same conceptual meaning of manner. More specifically, an onomasiological approach to corpus data is ‘one which starts from a given concept (here manner) and looks for the linguistic forms that bear this concept’ (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024, p. 3).

According to Stosic (Reference Stosic2020), five formal linguistic devices that encode manner are present: lexical, syntactic, morphological, grammatical and prosodic. Lexically, manner can be encoded through nouns, verbs and adverbs. Syntactic constructions further expand the ways in which manner can be encoded. Adverbs, prepositional phrases, gerunds and subordinate clauses all serve to convey the manner of an action. Morphological encoding of manner covers the use of affixes and word formations. Grammatical devices for manner expression are less varied but include words such as ‘how’ or ‘like’.

Following the research of Combe and Stosic (Reference Combe and Stosic2024) on manner transfer in interpreting, this study focuses on lexical and syntactic ways of encoding manner, more specifically manner verbs and manner adjuncts. The manner verbs are ‘accelerate’ (1), ‘improve’ (2), ‘surface’ (3), ‘抒’ (4), ‘纪念’ (5) and ‘献’ (6), all of which are identified from the original source texts used in the interpreting tasks.

-

(1) Accelerate the development of the western provinces: The verb ‘accelerate’ encodes manner by specifying the speed at which the action occurs, implying a process of increasing speed. Here, ‘accelerate’ signals not just the development but the rapid progression of that development.

-

(2) Improve the business environment: The manner verb ‘improve’ encodes a qualitative change, suggesting a positive transformation. The verb suggests a progressive refinement or correction, highlighting upward transformation.

-

(3) Chinese influences which have surfaced in Singapore English: In this context, ‘surfaced’ encodes manner by illustrating how the influences become noticeable. It emphasizes the process through which something that was previously latent becomes apparent, thereby describing a gradual revelation.

-

(4) 各抒己见 (gè shū jǐ jiàn): The verb ‘抒’ conveys manner by indicating the full expression of individual opinions. It encodes a manner of articulation that is unrestrained, reflecting the way opinions are aired without reserve.

-

(5) 以各种形式纪念 (yǐ gè zhǒng xíng shì jì niàn): In comparison with manner-neutral verbs such as ‘记忆’ (memorize) or ‘想起’ (recall), the verb ‘纪念’ encodes the manner in which remembrance is carried out, often involving formal or ceremonial activities.

-

(6) 献计献策 (xiàn jì xiàn cè): The verb ‘献’ in this phrase encodes manner by highlighting the act of offering ideas and strategies in a constructive and voluntary manner.

Six manner adjuncts are analysed in this study, three of which are in English source texts and three of which are in Chinese source texts. The manner adjuncts are ‘nearly’ (7), ‘together’ (8), ‘upon these foundations’ (9), ‘大踏步’ (10), ‘共同’ (11) and ‘忘我’ (12).

-

(7) Has nearly doubled: In this phrase, ‘nearly’ functions as a manner adjunct that specifies the extent or degree of the doubling. It modifies the verb ‘doubled’ by describing how the action of doubling occurred, namely almost reaching a complete doubling but not quite.

-

(8) We can only tackle global problems if we work together: The word ‘together’ functions as a manner adjunct here, specifying the way in which the action of tackling global problems should be accomplished.

-

(9) Upon these foundations, I want to build a modern relationship with China: The phrase ‘upon these foundations’ emphasizes the manner in which the relationship is to be developed – starting from the established groundwork or principles.

-

(10) 大踏步前进 (dà tà bù qián jìn): Here, ‘大踏步’ literally means ‘big strides’ and functions as a manner adjunct describing how the action of advancing is performed. It conveys that the progress or movement is characterized by large, bold steps, indicating a significant and assertive approach to advancing forward.

-

(11) 共同完成 (gòng tóng wán chéng): The term ‘共同’ means ‘together’ or ‘jointly’, serving as a manner adjunct that specifies how the action of completing something is carried out, indicating that completion of tasks involves cooperation.

-

(12) 忘我工作 (wàng wǒ gōng zuò): The term ‘忘我’ translates to ‘selflessly’ or ‘with disregard for oneself’ and acts as a manner adjunct detailing how the work is performed. It emphasizes the intensity and dedication with which the work is done.

As demonstrated in previous studies, the manner expressions cover a wide range of semantic values (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024; Stosic, Reference Stosic, Aurnague and Stosic2019, Reference Stosic2020). The semantic values of the 12 manner verbs and manner adjuncts explored in this study reflect a certain level of diversity. For the manner adjuncts, ‘nearly’ reflects intensity, specifying the degree to which an action or state has progressed. ‘Together’ and ‘upon these foundations’ denote means within the context of social interactions and collaborative creation. ‘大踏步’ (dà tà bù), meaning to make great strides, can indicate speed or intensity in the manner of progression. The adjuncts ‘共同’ (gòng tóng) and ‘忘我’ (wàng wǒ) also relate to means, particularly in terms of social interactions and collective effort.

For the manner verbs, the verb ‘accelerate’ exemplifies the semantic value of speed by indicating the rate at which an action progresses. ‘Improve’ falls under judgement of choice because it implies an enhancement or betterment based on evaluative criteria. Similarly, ‘献’ (to contribute) also pertains to judgement and choice. ‘Surface’ relates to gradual creation, reflecting the emergence or development of something over time. The verb ‘抒’ (shū) fits into the domain of communication, specifically referring to the complete expression of emotions or thoughts. ‘纪念’ (jìniàn), meaning ‘to commemorate’, is associated with social interactions and focused on the social context of remembering or honouring.

3 Cognitive load in CI

While a number of studies based on the Talmy’s typology have analysed manner expressions across languages with elicitation tasks (Hendriks & Hickmann, Reference Hendriks and Hickmann2015; Ji & Hohenstein, Reference Ji and Hohenstein2014; Tusun, Reference Tusun2022) and translation tasks (Alonso, Reference Alonso2011; Cifuentes-Férez & Rojo, Reference Cifuentes-Férez and Rojo2015; Lester, Reference Lester2017), relatively few studies have examined interpreting, particularly CI. A notable exception is the work of Combe and Stosic (Reference Combe and Stosic2024), which focuses on SI.

While SI is generally thought to involve heavy cognitive load (Seeber, Reference Seeber2013), in comparing the cognitive load associated with SI and CI, research generally indicates that CI could impose even greater cognitive demands. For instance, Liang et al. (Reference Liang, Fang, Lv and Liu2017) demonstrate that CI results in shorter dependency distances than SI, indicating the heavier cognitive demands placed on CI. Additionally, Lv and Liang (Reference Lv and Liang2019) report that CI output is often more simplified than SI output, which further suggests that CI’s cognitive load is as high as, if not higher than, that of SI. Further supporting this view, Lin and Liang (Reference Lin and Liang2023) show that CI output entails higher word entropy and lower word repeat rates than SI, reflecting a challenging cognitive equilibrium between production economy and comprehension sufficiency during CI. In conclusion, the cumulative evidence suggests that CI involves significant cognitive load, which, contrary to earlier assumptions, may exceed that of SI (Jia & Liang, Reference Jia and Liang2020).

The factors that influence cognitive load in CI are multifaceted, ranging from the characteristics of the interpreting task itself to external environmental conditions and the interpreter’s cognitive abilities (Chen, Reference Chen2017). Chen (Reference Chen2017, p. 643) identifies several task characteristics that affect the cognitive burden: the interpreting mode (simultaneous or consecutive), the language pair, interpreting direction, features of the speech (such as length, speed and complexity) and the speaker’s characteristics (e.g., accent or fluency). For example, interpreting into a non-native language can amplify the load by increasing the effort needed to achieve accurate comprehension and produce reformulation (Moratto & Yang, Reference Moratto and Yang2023). Environmental factors also play a role in shaping cognitive load. As Chen (Reference Chen2017, p. 645) notes, conditions such as noise, seating arrangement, lighting and the visibility of the speaker or audience can affect an interpreter’s performance. The interpreter’s individual characteristics are crucial in determining cognitive load as well, such as cognitive abilities, motivation, experience and the interpreter’s arousal or activation level (Chen, Reference Chen2017, p. 646).

Seeber (Reference Seeber2013, p. 19) defines cognitive load as ‘the amount of capacity the performance of a cognitive task occupies in an inherently capacity-limited system’. To measure cognitive load in interpreting, four methods have been generally proposed (Paas et al., Reference Paas, Tuovinen, Tabbers and Van Gerven2003; Seeber, Reference Seeber2013): analytical, subjective, performance and psycho-physiological methods. Analytical methods, for instance, involve task analysis to estimate the cognitive demands. Subjective methods use self-reports or questionnaires to quantify the interpreter’s perceived cognitive load. Psycho-physiological methods measure biological indicators, such as heart rate or pupil dilation, to gauge cognitive effort. Performance methods involve analysing the accuracy and fluency of the interpreted speech as indicators of cognitive load.

This study generally uses a performance-based measure of cognitive load with the results of interpreting tests. The rationale is that a decline in the quality of performance is likely to be linked with an increase in cognitive load (Chen, Reference Chen2017, p. 647). For example, advanced interpreting students are found to retain and interpret more propositions than beginning interpreting students, indicating better memory retention and encoding strategies in interpreting (Zou & Guo, Reference Zou and Guo2024). Another factor influencing cognitive load analysed by this study is directionality. Moratto and Yang (Reference Moratto and Yang2023) reveal that interpreting from Chinese to English is associated with higher cognitive load, as indicated by an increase in disfluencies compared to interpreting from English to Chinese. More specifically, Chen (Reference Chen2020) reports that interpreting from an L2 to an L1 imposes a higher cognitive burden during the note-taking phase, leading interpreters to adopt more detailed notes with fewer symbols. However, the production phase is less demanding in this direction, resulting in a more fluent target speech, though it may be less accurate. This study focuses on the cognitive effects of interpreting performance and directionality on manner transfer rates in CI, while generally controlling for other task-related and environmental factors. All participants interpret the same segment in the same environment, minimizing external influences on cognitive performance.

4 Hypotheses

4.1 A diversity of encoding ways of manner with varying levels of cognitive load

The first hypothesis of this study is that interpreters experiencing different levels of cognitive load will exhibit a diversity of encoding ways when interpreting manner verbs and manner adjuncts. Based on previous research that highlights the flexible encoding of manner in different languages (Slobin, Reference Slobin, Sven and Verhoeven2004), it is expected that the different levels of cognitive load will lead to variability in how manner verbs and adjuncts are transferred. In other words, the interpreters, under different levels of cognitive load, may display different target forms of the same source form. This hypothesis aligns with the idea that encoding ways are influenced by linguistic competence and the cognitive effort required to process manner information in the target language.

4.2 Directionality and manner transfer

The hypothesis regarding directionality suggests that the transfer rates of manner verbs and adjuncts will differ depending on whether the translation is from Chinese to English (CE) or from English to Chinese (EC). Drawing from typological differences between S-framed and E-framed languages (Chen & Guo, Reference Chen and Guo2009; Ji et al., Reference Ji, Hendriks and Hickmann2011) the findings of manner transfer in French–English interpreting (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024), it is expected that manner verbs will be more frequently transferred in the CE direction due to English’s tendency to encode manner through verbs. Conversely, manner adjuncts are expected to show higher transfer rates in the EC direction due to Chinese’s tendency to encode manner in more flexible positions (Ji & Hohenstein, Reference Ji and Hohenstein2014).

4.3 Effects of interpreting performance on manner transfer

The third hypothesis posits that reduced cognitive load will result in higher transfer rates for both manner adjuncts and manner verbs in CI. Research indicates that higher interpreting performance correlates with reduced cognitive load during interpreting tasks (Paas et al., Reference Paas, Tuovinen, Tabbers and Van Gerven2003; Seeber, Reference Seeber2013), which should enable more frequent transfer of manner information. In addition, as interpreting performance improves, interpreters are expected to more readily encode manner in the target language by drawing on a larger vocabulary and better understanding of language-specific manner encoding patterns. This hypothesis is based on the previous research showing that interpreters’ working memory is supported by L2 vocabulary (Elisabet Service & Simard, Reference Simard, Schwieter and (Edward) Wen2022) and language proficiency (Tzou et al., Reference Tzou, Eslami, Chen and Vaid2012) and that working memory is related to enhanced interpreting performance (Zheng & Kuang, Reference Zheng, Kuang, Schwieter and (Edward) Wen2022).

4.4 Directionality and effects of interpreting performance on manner transfer

The final hypothesis addresses the interaction between interpreting direction and interpreting performance, suggesting that interpreting performance will have varying effects depending on the directionality. This hypothesis builds on research suggesting that typological differences between languages influence how interpreters manage cognitive load and transfer manner information across directions (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024). Specifically, it is expected that the transfer of manner adjuncts will show greater resilience to cognitive load in the EC direction, given Chinese’s flexible manner-encoding locus. On the other hand, interpreting performance is hypothesized to have a weaker effect on the transfer of manner verbs in the CE direction, where English’s S-framed structure makes manner verbs more codable and salient.

5 Methods

5.1 Corpus data

The Parallel Corpus of Chinese EFL Learners (PACCEL) is the first learner corpus in China focusing on English–Chinese and Chinese–English interpreting and translation (Wen & Wang, Reference Wen and Wang2008). It collects interpreting and translation data from Chinese university students majoring in English in their Band-8 Tests for English Majors (TEM-8). The level of difficulty is generally consistent across all source texts, as the TEM-8 aims to evaluate the implementation of the syllabus, specifically the comprehensive language skills and communicative competence required at the Band-8 level, which refers to the level of English proficiency expected for English-major students in their eighth term of studies. PACCEL is divided into two sub-corpora: the Parallel Corpus of Chinese EFL Learners-Spoken (PACCEL-S) and the Parallel Corpus of Chinese EFL Learners-Written (PACCEL-W).

For this study, PACCEL-S is used. This sub-corpus includes the parallel data from the Chinese–English and English–Chinese interpreting components of the TEM-8 tests for 5 years, spanning from 2003 to 2007. The corpus compilation process for the PACCEL involves sample selection, conversion of tape recordings to MP3 format, manual transcription, proofreading, single-item scoring computation, metadata annotation, alignment of bilingual texts and part-of-speech tagging (Wen & Wang, Reference Wen and Wang2008). The TEM-8 interpreting test requires students to respond to questions based on recorded prompts and record their answers. Task I involves interpreting from English into Chinese, with speech materials covering topics in social, political, economic and cultural domains, while Task II requires interpreting from Chinese into English with Chinese speech materials on similar topics. The speeches are 2–3 min long, with around 300 English words for Task I and 400 Chinese characters for Task II (Wen & Wang, Reference Wen and Wang2008, p. 15). While the full speeches are played, participants are required to only interpret approximately 150 English words for Task I and 200 Chinese characters for Task II. During playback, participants are allowed to take notes and are provided with guidance prompts to aid their segmented interpretation of the content.

In this study, the Chinese and English source texts across the 5 years in PACCEL-S (totalling around 1,500 words) are scanned for three manner verbs and three manner adjuncts in each interpreting direction, totalling 12 manner expressions. Each piece of source text has between 174 and 191 responses, varying slightly depending on the number of students covered by PACCEL in each year. In the metadata, the ‘level’ indicates the within-group rank. To ensure that interpreting performance levels are comparable across groups, each group in the PACCEL is formed through a stratified random sampling process, addressing the uneven distribution of participants from various types of schools. Each group consists of around 32 test sessions, and this sample size was determined to ensure that each group reliably reflects the overall proficiency distribution of all examinees (Wen & Wang, Reference Wen and Wang2008, p. 12). Within each group, the ‘level’ indicates the relative ranking of interpreting scores, with each response assigned a level based on its within-group rank (Wen & Wang, Reference Wen and Wang2008, p. 17). In the ranking structure, Level 1 (L1) indicates the highest level of performance; Level 2 (L2) refers to the intermediate level, and Level 3 (L3) suggests the lowest level of performance. The score refers to the score points achieved in the interpreting test. For each source form in CE and EC, Table 1 presents the number of responses and the number of English words and Chinese characters across different levels of interpreting performance.

Table 1. Corpus overview

The scoring of interpreting performance emphasizes the completeness, accuracy and fluency of information transference, with ‘excellent’ denoting accurate translation of the majority of the speech with fluent expression, ‘good’ indicating accurate translation of most content with relatively fluent expression, ‘pass’ suggesting translation of basic content with fair accuracy and basic fluency and ‘fail’ pointing to significant omissions, errors and lack of fluency in expression (Wen & Wang, Reference Wen and Wang2008, p. 11). The evaluation process is divided into six steps to ensure reliability and validity: random grouping of cassette tapes using stratified sampling, scorer training sessions focusing on scoring guidelines and criteria discussion, independent scoring by two individuals for each tape, reconciliation of scores for discrepancies between scorers by a quality control team, averaging final scores assigned by each pair of scorers and verification of potential outstanding or failing candidates’ tapes by a quality control team after individual tape reviews.

5.2 Coding principles

This study aims to replicate the manner coding framework used in the previous studies (Stosic, Reference Stosic, Aurnague and Stosic2019, Reference Stosic2020), ensuring continuity with established methodology for cross-domain manner coding. The identification of manner verbs and manner adjuncts in this study follows the framework outlined by Stosic (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024), and the recognition of specific expressions as manner adverbs or verbs is grounded in scholarly precedents. For example, the verb ‘纪念’ (to commemorate) is categorized as a manner verb in Combe and Stosic’s (Reference Combe and Stosic2024) analysis. In addition, the typological research on Chinese manner expressions is also drawn on to ensure a valid coding. An example is the manner adverb ‘大踏步’ (with strides), which is classified as a manner adjunct in the study by Chen and Guo (Reference Chen and Guo2009, p. 1764).

The determination of whether each source form is transferred or non-transferred is based on the presence of manner information. Supplementary Table 1 presents a detailed display of whether each target form under the same source form is categorized as transferred or non-transferred. To assess the reliability of the coding process, the interpreting of manner is coded at two time points separated by 2 weeks with the same coder. The two coding results are analysed for reliability calculations. The resulting Cohen’s kappa coefficient is calculated to be 0.987 with a 95% confidence interval of [0.981, 0.994], indicating a high level of agreement between the two coding instances. The Holsti coefficient is 0.997, which underlines the high degree of consistency. These results suggest that the coding process is generally consistent and reliable, with minimal discrepancies between the coding instances. The statistical analysis is completed with JASP 0.18.3.0 (JASP Team, 2024).

6 Results

6.1 A diversity of encoding ways of manner with varying levels of cognitive load

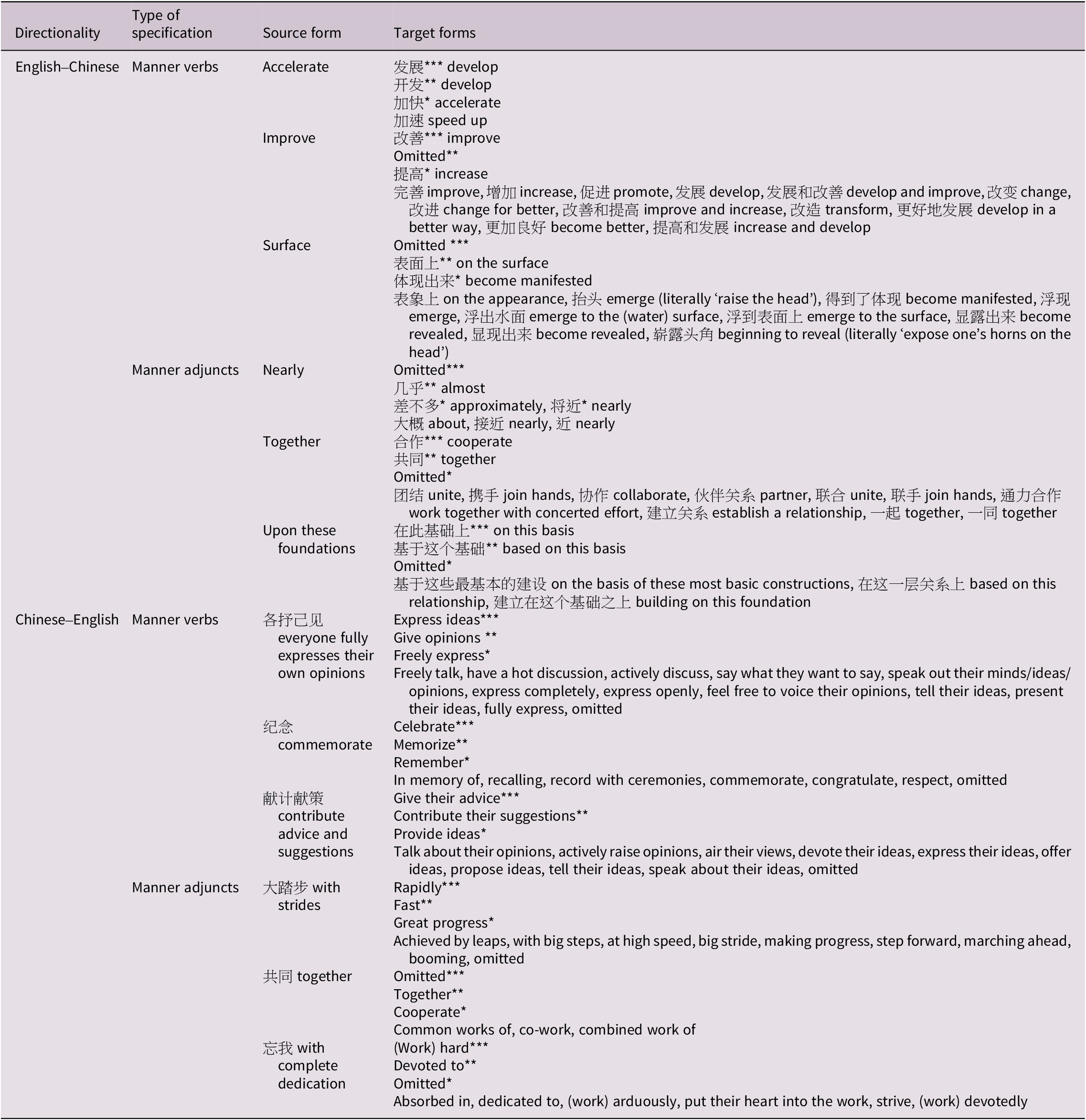

When examining the translations of manner verbs and manner adjuncts in EC and CE directions, this study observes a diverse array of target forms corresponding to specific source forms. This diversity is displayed in Table 2, where various translations of each manner verb and each manner adjunct are listed. For example, the translations of the manner verb ‘surface’ illustrates the complexity involved in the transfer of conceptual content across languages. It can be omitted or rendered as ‘表面上’ (on the surface), ‘表象上’ (on the appearance), ‘抬头’ (literally ‘raise the head’, figuratively ‘emerge’), ‘体现出来’ (become manifested), ‘得到了体现’ (become manifested), ‘浮现’ (emerge), ‘浮出水面’ (emerge to the water surface), ‘浮到表面上’ (emerge to the surface), ‘显露出来’ (become revealed), ‘显现出来’ (become revealed) and ‘崭露头角’ (literally ‘expose one’s horns on the head’, meaning beginning to reveal). ‘Omitted’ indicates cases where the source form is entirely left untranslated. For example, in the translation of ‘has nearly doubled’ into ‘达到双倍’ (has doubled), the manner adjunct ‘nearly’ is entirely omitted in the target text. To clarify frequency trends, the three most frequent target forms for each source form are highlighted. The most frequent form is marked with ***, the second most frequent with ** and the third most frequent with *.

Table 2. Diverse target forms of manner verbs and manner adjuncts in Chinese–English and English–Chinese interpreting

6.2 Directionality and manner transfer

As shown in Table 3, a marginal difference between CE and EC is observed in the transfer rates of manner adjuncts, with CE exhibiting slightly higher transfer rates at 60.39% than 59.31% in EC. Regarding manner verbs, the disparity between the two directionalities becomes more pronounced. Once again, CE displays higher transfer rates at 43.84%, outperforming EC (36.94%). Overall, the tendency to transfer manner expressions is more prevalent in CE (52.23%) than in EC (48.05%). The results of the Chi-squared tests indicate no significant difference between the two language directionalities for manner adjuncts (χ 2 (1) = 0.136, p = 0.713) but a statistically significant difference for manner verbs (χ 2 (1) = 5.479, p = 0.019). Similarly, the overall transfer rates of manner expressions differ significantly between CE and EC (χ 2 (1) = 3.886, p = 0.049).

Table 3. The transfer rates of manner verbs and manner adjuncts in Chinese–English and English–Chinese interpreting

A closer look at the transfer rates of specific source forms in CE and EC interpreting is presented in Table 4. In CE interpreting, one manner verb, ‘纪念’ (commemorate), and two manner adjuncts, ‘忘我’ (selflessly) and ‘大踏步’ (with strides), display high transfer rates, all exceeding 65%. The transfer rates for the manner verbs ‘献计献策’ (contribute suggestions) and ‘各抒己见’ (each fully expressing ideas) and the manner adjunct ‘共同’ (together) are much lower, ranging from approximately 30% to 40%.

Table 4. The transfer rates of 12 source forms in Chinese–English and English–Chinese interpreting

In EC interpreting, two manner adjuncts (‘upon these foundations’ and ‘together’) and one manner verb (‘improve’) exhibit transfer rates above 75%, indicating a strong tendency to transfer these expressions in translation. The transfer rates for other manner verbs and adjuncts are considerably lower. The manner verbs ‘accelerate’ and ‘surface’ have transfer rates of only 32.97% and 4.19%. The manner adjunct ‘nearly’ shows a markedly low transfer rate of 6.90% than two other adjuncts.

6.3 Effects of interpreting performance on manner transfer

The transfer rates of manner expressions increase with the rise in the performance of interpreters. The patterns of change in transfer rates are consistent across manner adjuncts, manner verbs and the total transfer rate (Figure 1). The results of the Chi-squared tests indicate that the differences in transfer rates between different scores in interpreting tests are statistically significant for manner adjuncts (χ 2 (2) = 28.536, p < 0.001), manner verbs (χ 2 (2) = 33.779, p < 0.001) and the total manner expressions (χ 2 (2) = 60.475, p < 0.001).

Figure 1. The changes of lexical, syntactic and general transfer rates with levels of interpreting performance.

Shapiro–Wilk tests are used to assess the normality of the distribution, and the results suggest deviations from normality. Therefore, Mann–Whitney U tests are used to compare the scores of interpreters producing transferred and non-transferred expressions. The statistical comparison of interpreters’ scores reveals that interpreters who transfer manner adjuncts (p < 0.001) and manner verbs (p < 0.001) achieve significantly higher TEM-8 interpreting scores and demonstrate better interpreting performance.

The effect sizes, measured by rank–biserial correlation, are −0.159 for manner adjuncts and −0.326 for manner verbs. These values indicate a moderate effect size for manner verbs in contrast with a small effect size for manner adjuncts. This finding is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows raincloud plots depicting the scores of interpreters delivering transferred versus non-transferred manner verbs and adjuncts.

Figure 2. Raincloud plots showing the scores of the interpreters delivering transferred and non-transferred manner.

6.4 Directionality and effects of interpreting performance on manner transfer

Figure 3 presents the changes in lexical and syntactic transfer rates by levels of interpreting performance for both CE and EC interpreting. The transfer rates of manner adjuncts decrease more sharply with declined interpreting performance in CE interpreting than EC interpreting. As the interpreters with lower levels of interpreting performance experience increased cognitive load when interpreting the same source texts, this pattern suggests that EC interpreters display greater resistance to the increase in cognitive load.

Figure 3. The changes of lexical and syntactic transfer rates with levels of interpreting performance in English–Chinese and Chinese–English interpreting.

For manner verbs, the decline in transfer rates with decreasing interpreting performance is more moderate in CE interpreting, whereas there is a steeper decline in EC interpreting. This pattern implies that CE interpreting is more resistant to increased cognitive demands. At the lowest level of interpreting performance (L3), transfer rates for EC are around 20%, lower than the 40% observed in CE. At intermediate interpreting performance (L2), the gap narrows but persists, and at the highest level of interpreting performance (L1), EC transfer rates surpass those of CE.

Chi-squared tests indicate significant differences in manner adjunct transfer rates across levels of interpreting performance in CE (χ 2 (2) = 17.255, p = 0.003) and EC (χ 2 (2) = 11.741, p < 0.001) interpreting, and for manner verbs in EC interpreting (χ 2 (2) = 37.178, p < 0.001). However, the performance-level differences for manner verbs in CE interpreting are not statistically significant (χ 2 (2) = 4.931, p = 0.085).

Mann–Whitney U tests further examined the score differences between transferred and non-transferred expressions. The results are consistent with Chi-squared tests for differences across interpreting performance levels. No significant score difference is found in EC interpreting of manner adjuncts (p = 0.072). Significant differences in the other groups have effect sizes of −0.162 for CE manner verbs, −0.239 for CE manner adjuncts and −0.457 for EC manner verbs. These differences are illustrated in Figure 4, which highlights the largest score differences in EC interpreting of manner verbs.

Figure 4. Raincloud plots showing the scores of the interpreters delivering transferred and non-transferred manner in Chinese–English and English–Chinese interpreting.

7 Discussion

7.1 A diversity of encoding ways of manner with varying levels of cognitive load

The variety of target forms observed in the translation of manner verbs and adjuncts may reflect the cognitive processes involved in interpreting conceptual structures between two languages, one of which is E-framed and the other S-framed, with some areas of overlap in manner expressions. Translating manner expressions requires interpreters to not only capture the surface meaning of the source form but also reconstruct its underlying conceptual schema in a target language that may not place the same focus or emphasis on manner. The differences in translations may be attributed to the varying degrees of cognitive demand faced by interpreters of different levels of interpreting performance. This variation could offer insights into how cognitive load influences interpreting choices in tasks involving the translation of manner expressions.

7.2 Direction and manner transfer

As the differences in transfer rates for manner adjuncts between the two directionalities (CE and EC) are not statistically significant, the primary focus of the following discussion is on the transfer differences in manner verbs. The results of the study show that manner verb transfer rates are significantly higher in CE interpreting than in EC interpreting. Supporting Talmy’s hypothesis (Talmy, Reference Talmy2000, p. 128) of greater cognitive salience and accessibility of manner in English, this pattern can be explained by the typological differences in the levels of verbal manner codability between two languages.

English is a S-framed language, where manner is often encoded in the central verb with low cognitive costs. This structure makes manner more salient and central to the verbal meaning, thus facilitating the transfer of manner verbs during interpreting. In contrast, Chinese, as an E-framed language, tends to encode both manner and path in compound verbs, placing equal emphasis on both elements (Ji & Hohenstein, Reference Ji and Hohenstein2018; Spring & Horie, Reference Spring and Horie2013). Chinese’s E-framed structure leads to a less distinct focus on manner verbs, as a ‘Manner–and–Path salience’ cognitive pattern is present in this language (Ji, Reference Ji2019, p. 9). English’s focus on manner in the main verb makes manner information more easily codable and transferable, while Chinese’s equal emphasis on manner and path introduces challenges for interpreters.

For tasks involving manner verbs, interpreters are more likely to prioritize manner when interpreting into English, whereas they may focus on both manner and path when interpreting into Chinese, potentially leading to a dilution of verbal-encoded manner information in the interpreting. When interpreting from Chinese to English, the salience of manner in English, which reduces the cognitive load associated with manner encoding, encourages interpreters to cognitively process and effectively transfer manner verbs. This difference in the salience of manner between the two languages explains the higher transfer rates of manner verbs in CE interpreting and the relatively lower rates in EC interpreting.

For instance, in the CE direction, manner verbs such as ‘献计献策’ (contribute ideas) can be rendered in English through multiple options such as ‘offer’ (1), ‘provide’ (2), ‘contribute’ (3) or ‘devote’ (4), which demonstrates English’s flexibility in encoding manner through verbs. On the other hand, when translating from English into Chinese, manner verbs such as ‘accelerate’ often encounter limitations in the target language. The example of ‘accelerate’ shows that in Chinese, only two options, ‘加快’ (accelerate) or ‘加速’ (speed up), exist to capture this concept (Table 2), and a large portion of these manner verbs (67.03%) are often omitted in the translation process, even by proficient student interpreters (5). This suggests that the codability of manner verbs in Chinese is less versatile than in English, contributing to lower manner verb transfer rates in EC interpreting.

Source texts for (1)–(4):

During the meeting, experts and scholars from different countries and regions freely express their opinions and completely convey their views, and actively contribute advice and suggestions for the protection and renewal of the old city.

Source texts for (5): The Government’s desire to accelerate the development of the western provinces is vital to the success of achieving a sustained growth for China in the long run.

Well, the government, the government’s desire to develop the western regions is crucial for the sustained and stable development of the entire Chinese economy, the sustained and stable development, achieving, achieving success, is very critical. (Level: L1; Score: 80)

The results of this study align with findings from a previous study on English–French and French–English interpreting (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024), which also observes non-significant differences in manner adjuncts between directions of interpreting and significantly higher transfer rates for manner verbs when interpreting into English. This consistency might suggest a broader pattern where the encoding of manner in S-framed languages, such as English, facilitates higher transfer rates for manner verbs, irrespective of the specific source languages. The higher transfer rates in English across different language pairs further support the notion that S-framed languages, by centrally encoding manner in the main verb, offer cognitive advantages for transferring manner information in comparison with E-framed or V-framed languages.

The findings regarding L1-to-L2 and L2-to-L1 interpreting might partially explain the results as well. A study (He et al., Reference He, Hu, Yang, Li and Hu2021) has demonstrated through functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) technology that L1-to-L2 interpreting induces greater cortical brain activity than L2-to-L1 interpreting, reflecting the heightened cognitive load when interpreting into a second language. However, despite the higher cognitive load associated with L1-to-L2 interpreting, the information transferred is often more complete (Chou et al., Reference Chou, Liu and Zhao2021). A review of the research on directionality and interpreting suggests that unbalanced bilingual student interpreters often exhibit better performance in terms of content completeness in the L1-to-L2 direction but greater fluency when interpreting in the L2-to-L1 direction (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Abdullah and Ang2023). In the context of this study, the higher transfer rates of manner verbs in CE interpreting (L1-to-L2) align with previous findings that suggest greater completeness of information transferred in the L1-to-L2 direction. The higher verbal codability of manner in English might potentially mitigate the increased cognitive demands associated with L1-to-L2 interpreting.

7.3 Effects of interpreting performance on manner transfer

The findings of this study suggest that a rise in levels of interpreting performance significantly increases transfer rates of manner expressions. This correlation may be grounded in the performance-based measure of cognitive load; a reduction in cognitive demand, attributable to better interpreting performance, facilitates more effective transfer of manner expressions. The result is consistent with a previous study on French–English SI (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024), which examines cognitive demand through the source language rate of speech. This study supports the perspective from a different angle, demonstrating that the cognitive ease afforded by increased levels of interpreting performance contributes to higher transfer rates of manner expressions.

Vocabulary knowledge likely plays a role in the influence of levels of interpreting performance on transfer rates. For instance, the term ‘surface’ may be misinterpreted as ‘表面上’ (on the surface) by learners with lower level of interpreting performance (6) due to limited vocabulary. As interpreting performance improves, interpreters develop a larger vocabulary and are better able to accurately identify the intended meaning of words, which leads to higher transfer rates. This difference can be observed in the varying transfer rates of ‘surface’ across levels of interpreting performance, with five successful transfers at L1, two at L2, and only one at L3. This pattern suggests that initial misunderstandings or limitations in vocabulary knowledge can be gradually resolved as interpreting performance improves, contributing to more accurate and frequent transfer of meaning.

Uh, however, some, uh, Chinese, uh, English influence is, uh, just some Singapore, regarding some superficial influence on Singapore, and he, uh, just is a, uh, preparing in English aspect.

The findings also indicate that the improvement in levels of interpreting performance has a slightly greater effect on the transfer rates of manner verbs compared to manner adjuncts, with effect sizes of −0.164 and −0.151 respectively. One possible explanation for the small difference is that manner verbs are often more central to the core meaning of a sentence in English, particularly due to the S-framed nature of the language, which emphasizes manner through verbs. As interpreting performance increases, interpreters may become more adept at transferring these manner verbs because they become more familiar with the conceptual pattern in the source language or the target language. In contrast, manner adjuncts, while also important, might not be as central or immediately salient in the transfer process, leading to a slightly smaller effect size in their improvement.

Consistent with the previous studies (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024, p. 25), this study also reveals that the processing of manner verbs incurs higher cognitive costs than manner adjuncts, leading to lower transfer rates for manner verbs than manner adjuncts. This contradicts the assumption that manner would be processed at a lower cognitive cost at the verb level compared to adjuncts (Talmy, Reference Talmy2000).

7.4 Direction and effects of interpreting performance on manner transfer

For manner adjuncts, the transfer rates in the EC direction show greater resistance to cognitive load, which might be due to the higher codability of manner adjuncts in Chinese than in English. Among the four groups (CE manner adjuncts, EC manner adjuncts, CE manner verbs and EC manner verbs), only the EC interpreting of manner adjuncts displays non-significant decrease in transfer rates as cognitive load declines. This could be explained by the finding that Chinese encodes manner in adjuncts more frequently than in English (Ji et al., Reference Ji, Hendriks and Hickmann2011, p. 1056; Spring & Horie, Reference Spring and Horie2013, p. 703). The locus of manner information is generally more flexible than English, allowing adjuncts to encode manner more frequently. This flexibility and accessibility make manner adjuncts easier to transfer into Chinese, even under conditions of cognitive pressure, providing greater resilience in the EC direction.

In contrast, the transfer rates of manner verbs demonstrate stronger resistance in the CE direction, where the verbal codability of manner is higher in English. Chi-squared tests show a significant difference (χ 2 (2) = 37.178, p < 0.001) of TEM-8 scores between transferred and non-transferred cases of manner verbs, with an effect size of −0.457. English, as an S-framed language, primarily encodes manner through verbs, making manner verbs more salient and central to its linguistic structure than Chinese (Ji, Reference Ji2019). This salience of manner verbs in English offers interpreters cognitive advantages when processing and transferring manner verbs in this language, even under increased cognitive load, despite the higher cognitive demands of interpreting into a second language.

These findings suggest that in the EC direction, Chinese’s flexible locus of manner information provides greater resilience in transferring manner adjuncts. This pattern may be also partly attributed to the generally lower cognitive load associated with L2-to-L1 interpreting tasks (He et al., Reference He, Hu, Yang, Li and Hu2021). In contrast, in the CE direction, English’s strong verbal codability of manner facilitates a stronger resistance to cognitive load in the transfer rates of manner verbs, underscoring the role of languages’ typological differences in shaping resistance to cognitive load during interpreting tasks.

8 Conclusion

This study provides an analysis of the effects of interpreting directions and cognitive load on the transfer rates of manner adjuncts and manner verbs. For the diversity of encoding ways of manner, this study confirms that for the same source form, translators with varying levels of interpreting performance produce a range of different target forms. For the impact of directionality on manner transfer rates, the analysis reveals that while the differences in transfer rates for manner adjuncts between the CE and EC directions are not significant, the transfer rates for manner verbs are significantly higher in CE than in EC. This discrepancy underscores the influence of typological differences on interpreting performance, with English’s S-framed structure providing a more conducive environment for the transfer of manner verbs. For the effects of interpreting performance on manner transfer rates, the increased levels of interpreting performance are associated with higher transfer rates for both manner adjuncts and manner verbs. The increased English interpreting performance may reduce cognitive load and improve vocabulary use, leading to higher transfer rates of manner expressions. For the effects of direction on resistance to cognitive load, the direction of interpreting influences the resistance of manner transfer rates to cognitive load attributable to interpreting performance. Specifically, manner adjuncts exhibit greater resistance to cognitive load in the EC direction, likely due to the more flexible locus of manner information in Chinese than in English. Conversely, manner verbs show better resistance to cognitive load in the CE direction, attributed to the higher verbal codability of manner in English than in Chinese.

The results underscore the critical role of language-specific ways of organizing manner information in interpreting. More specifically, the inherent codability of manner verbs and adjuncts in the target language influences how effectively manner is transferred during interpreting tasks. It is found in this study that CE interpreters demonstrate cognitive advantages in transferring manner verbs, benefiting from the higher verbal codability of manner in English, which facilitates more robust transfer in the CE direction. These findings highlight how the typological differences in manner encoding affect the cognitive processing of motion under high cognitive pressure, and further research could be conducted to confirm whether similar patterns are present in other language combinations.

This study’s limitations include the potential constraints of diversity in the semantic domains covered in the manner expressions, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. The study relies on levels of interpreting performance as a proxy for cognitive load, which may not fully capture the complexity of cognitive processes in interpreting. The relatively small number of items could be attributed to two main factors. Firstly, the corpus, while extensive in terms of target texts (with 174–191 student interpretations per source text), consists of brief source texts, totalling around 1,500 words across 5 years and two language directions, which limits the number of items available for analysis. Secondly, the corpus is not specifically designed to target manner expressions, resulting in a limited occurrence of such expressions. Future research can address this limitation by designing a task explicitly focused on manner expressions to increase the number of items. Future research may also incorporate more diverse semantic domains of manner expressions, use direct measures of cognitive load such as neuroimaging and explore more other language pairs.

This study, consistent with a previous study (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024), reveals that expressions with higher codability in the target language are more frequently transferred during interpreting. For example, manner verbs, which are more codable in English, are transferred more successfully in the Chinese–English direction. This study aligns with research on S-framed and V-framed languages (Combe & Stosic, Reference Combe and Stosic2024) and confirms similar patterns between E-framed and S-framed languages. Future research could explore whether these patterns hold between E-framed and V-framed languages and examine intra-typological variations to further understand the role of codability in manner transfer during interpreting.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2024.72.

Data availability statement

The coding data and the texts of consecutive interpreting covered in this study can be found at https://osf.io/z948x/. This study uses a sub-corpus of Parallel Corpus of Chinese EFL Learners (PACCEL), which is not under my copyright, and the full corpus can be accessed via the CD-ROM included with the book purchase (Wen & Wang, Reference Wen and Wang2008).

Competing interest

The author declares none.