I. INTRODUCTION

This article follows the two in which we published all the ink writing-tablets from Vindolanda discovered in the excavation seasons 2001, 2002 and 2003.Footnote 1 It presents four of the longest and most important texts among some 24 groups of fragments discovered in the season of 2017, which have been chosen because they all relate to Iulius Verecundus, prefect of the First Cohort of Tungrians, but also to anticipate the projected fourth volume of Vindolanda writing-tablets (Tabulae Vindolandenses IV).Footnote 2 First, the archaeological context.

II. THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTEXT

By A. Birley and A. Meyer

In 2017, the Vindolanda excavations were entering the final year in a five-year research project entitled ‘Frontier in Transition’. The purpose of the project was to untangle and learn more about the variations in the lifestyles and lived experiences of those on the edge of the Roman Empire through the nine substantial periods of occupation at the site. Each of those periods is defined by a comprehensive demolition and subsequent rebuild of the fort and settlement. The first six periods of occupation, c. a.d. 85–160, were principally constructed in timber and the final three, c. a.d. 160–400, more substantially with stone.Footnote 3 The level of preservation and depth of material from each layer of occupation varies across the site depending on three principal factors: the original topography of the site; the process of demolition and whether this demolition was thorough and methodical or had been hastily done; and the material used for subsequent foundations or constructions. The latter is crucial in sealing earlier occupation and creating anaerobic, or oxygen-free, deposits. The best-preserved layers are restricted to the earliest phases of occupation, each associated with one of four timber forts occupied during c. a.d. 85–120. The maximum depth of Roman occupation, influenced by the range of factors described above, may be 3 to 7 metres below the current grass level on the site. An important part of the archaeological process is to establish where the first Roman levels interfaced with the pre-Roman Iron Age landscape, which allows the archaeological team to study the complete narrative of occupation from the beginning to the end of the Roman period.

In June 2017, the excavation team encountered a remarkably well-preserved and tightly-packed deposit of documents in a build-up of fill on a street outside the western perimeter of the first fort at the site. The team was working in a narrow 4 m-wide corridor between two previously consolidated stone barracks, dating to the early third century and later repurposed as foundations for extramural buildings after the Severan occupation. Below this, they encountered the remains of an anaerobically preserved mid-second-century workshop, situated above an anaerobically preserved timber Hadrianic cookhouse. The foundations of the cookhouse, complete with a large and well-preserved clay oven, had been placed over the demolished remains of three periods of wooden barracks dating to Periods II–IV (c. a.d. 90–120). These timber barracks, defined by small birch posts and wattle walls, had floors of hard-packed clay covered by compressed heather, bracken and straw. A similar floor material is characteristic of early occupation levels at the site and is often referred to as laminated material.Footnote 4 The occupational layers of the barracks and the laminated floors produced large quantities of broken pottery and animal bone, and a variety of everyday artefacts ranging from small bone-handled knives to leather shoes, wooden bath clogs and wooden bowls and spoons. Below the remains of the Hadrianic cookhouse there were no intrusive archaeological features apart from the small posts used to build each of the earlier barracks, and a wooden water pipe from Period IV (c. a.d. 105–120) first encountered to the west of this area in the 2003 excavations.Footnote 5 The floor of each of the barracks had been laid in typical style with hard-packed clay and was constructed directly above debris from the earlier phases. This greatly facilitated the separation and preservation of material from each phase of the building.

The final stage of the excavation involved lifting the primary clay floor of the earliest barrack in the area, dated to Period II (c. a.d. 90–100) to establish the pre-Roman ground level of extramural phases to the west of the ditches defending the perimeter of the smaller Period I fort, which was situated some 30 m to the east of the excavation area (fig. 1). The excavators found the remains of a narrow extramural path or street and an associated drain, with a cobbled surface, that had been cut into the natural boulder clay bank of the hillside. Those features had then been filled and levelled with debris and rubbish to create even foundations, 35–50 cm higher than the previous occupation, for the new barracks of the larger Period II fort. Unlike the laminated carpet material from inside the occupied barracks, the fill material was a mixture of straw, turf and mud. Although it contained a great deal of animal bone waste, there was relatively little pottery or other material that one would normally find in an occupational deposit.

FIG. 1. Period I and II Vindolanda in relation to the third-century fort with the excavation area marked.

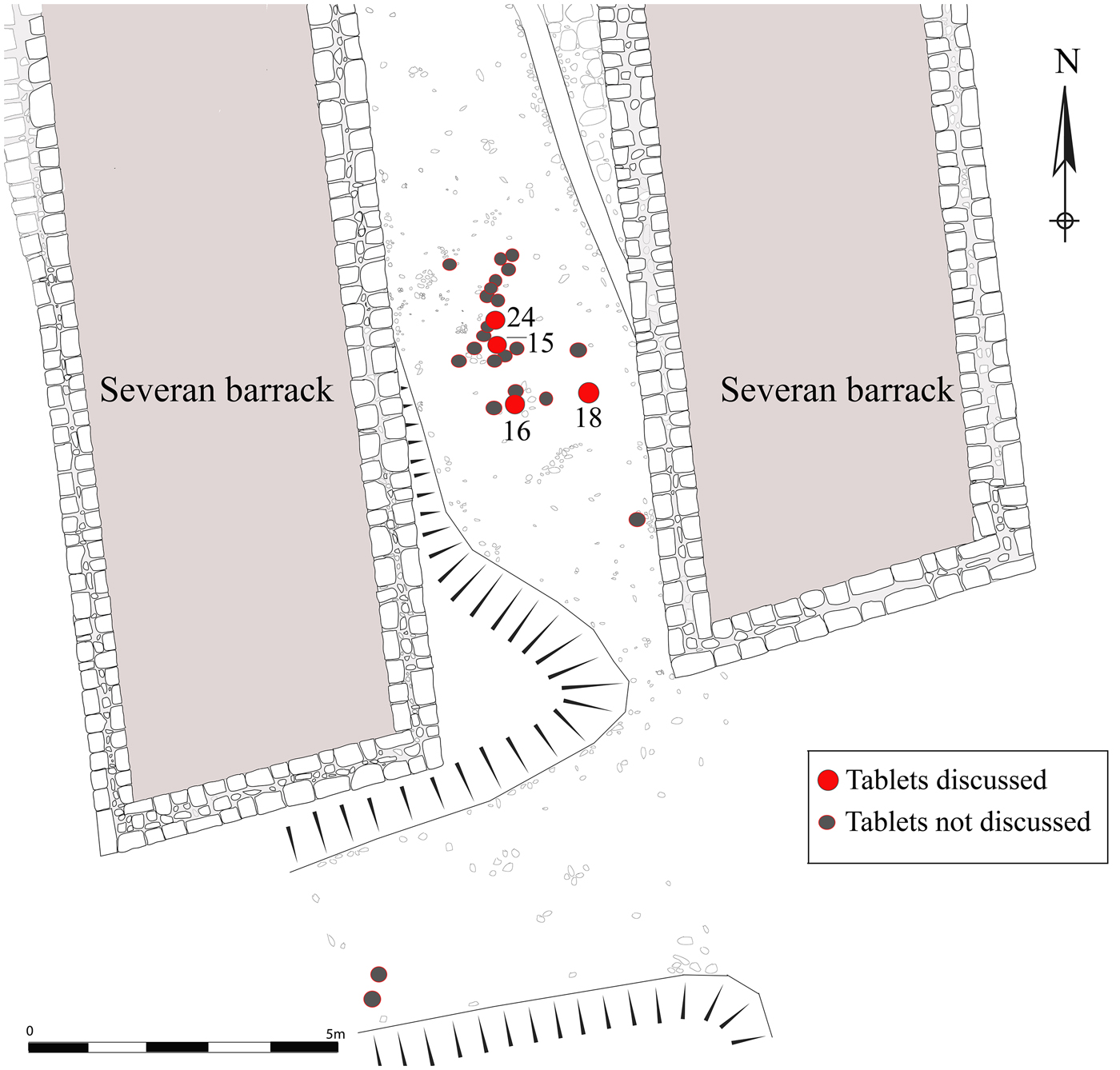

Situated some 10–15 cm above the cobbled Period I extramural road, in the middle layer of this landfill deposit were 24 ink writing-tablet fragments and two stylus tablet fragments. fig. 2 shows the location of each fragment in relation to the others and their corresponding site numbers. The level from which the tablets came, site context code V17-52B, was deliberately built up to accommodate the new barrack above and represented either a ‘single act’ of deposition or rapid formation, rather than an organically filled deposit that built up gradually over time with the natural use of the space. Refuse deposits which formed over many months or years have been encountered in other parts of the site and in multiple periods. Deposits of this type have a different formation process and character than does V17-52B.Footnote 6 However, there was no dark earth, silt layer or any other indicator of a gap in the occupation in the area between Periods I and II, and there was no discernible difference between the material holding the tablets in place and the fill immediately above and below them.

FIG. 2. Location of the tablets in relation to the Period I extramural road and later Severan barracks.

The tablets were relatively tightly grouped together rather than scattered, as shown in fig. 2. The 3 m by 2 m area within which they were found was defined by the cut of the road itself, a steep clay bank to the west and the drain to the east. No texts were recovered from within the steeply cut V-shaped drain to the east of the road or the clay bank to the west. This is an important point when considering the pattern and circumstances of deposition. Had deposition taken place organically over several months, it is highly likely that some of the texts would have been washed into the drain through post-depositional processes. They are light, buoyant and highly portable artefacts which would very quickly degrade if exposed to the elements.

The content of several tablets suggests that they came from the residence of the first known commanding officer at Vindolanda, Iulius Verecundus, who is attested in other tablets discovered at Vindolanda.Footnote 7 The context of their discovery, a clearing of buildings and the demolition of the Period I fort, including the commander's house, made way for a new and much larger Period II fort around a.d. 90. The northern edge of the praetorium of Verecundus in Period II was located some 37 m to the south-east of the location of the current finds, too far for the tablets to have travelled casually or been wind-blown and maintained such a tight grouping. The new evidence neatly confirms what has previously been proposed: that the initial garrison quartered in the Period II fort was the now enlarged First Cohort of Tungrians, still commanded by Iulius Verecundus.Footnote 8 It hardly needs reiterating that the two strength reports of this cohort (154 and 857) belong not to Period II but to Period I, as shown by the findspot of the second one, in the outermost western ditch of the Period II fort.

Although the documents are important texts, their significance as artefacts and as part of a larger dataset of material culture, potentially from the currently unknown location of the praetorium of Period I, cannot be overstated. The context in which the tablets were found (V17-52B) also contained a silver hairpin (SF 21503), an iron leather-working needle (SF 21054), several iron loops (SF 21071 and 21075), an iron spearhead (SF 21078) and an iron key (SF 21085). Other organic finds made from wood included a comb (W2017-58) and two beer mug staves (W2017-57, W2017-63), as well as a fine lady's shoe (L2017-108). None of those artefacts would have been out of place in a praetorium, and many similar finds were recovered from the floors and rooms of the Period II residence associated with Iulius Verecundus and excavated by Robin Birley between 1973 and 1976.Footnote 9

It is worth mentioning here, for the record, the simple but effective methodology used for the recovery of the writing-tablets which was developed successfully by Robin Birley in 1973.Footnote 10 The earth surrounding and containing the documents was carefully cut with a sharp spade, with gentle pressure, into small 20 by 20 cm blocks or bricks which were then passed up from the trench to be hand sorted. The blocks were processed by the application of light pressure by the naked hands of the excavator. This pressure causes a split where the smooth surface of artefacts held within the block differs from the coarse mud or surrounding organic material. The texts were not touched by the excavator and were immediately transferred into a vessel containing trench water, which had a low oxygen content, before being taken to the laboratory to start the cleaning and conservation process within an hour of discovery. This method allowed the area to be methodically excavated without the use of a trowel (which can be highly detrimental to the survival of the tablets because of their fragility) and was vital for the recovery of many of the smaller fragments.

III. IULIUS VERECUNDUS

The texts published here all concern Iulius Verecundus, prefect of the First Cohort of Tungrians, who also received a letter not yet published (Inv. no. WT 2017.34) from the decurion Cornelius Proculus. They need to be interpreted in the context of earlier tablets relating to him, all of them letters except for the two strength reports (154, 857). We refrain from using the term ‘archive’, which in its strictest sense should refer to a group of documents written, received or compiled by the same individual(s).

It is clear from the new tablets that Iulius Verecundus was prefect of the First Cohort of Tungrians during Period I and into Period II. We do not consider here the question of whether it returned later in Period IV under a different prefect, Priscinus (295–8, 636–8, and perhaps 663, 665 and 770). So far as we know, with confirmation from the strength reports, this unit was double-strength (milliaria) and was not part-mounted (equitata).Footnote 11 The correspondence relating to the prefect Verecundus published in earlier volumes (210–212, 302), like the strength reports, almost all derives from the archaeological contexts of Periods I and II. The exception is 313, which is thought to derive from Period III, but is a fragment of a letter referring to Verecundum praef(ectum) in the third person, written in the same hand as 213 from Period II. It should also be noted that Verecundus is a common name which occurs in several other tablets where there is no clear indication that it referred to the prefect.

For the name Verecundus Anthony Birley refers us to OPEL (IV, 157ff.), which lists 167 examples, 33 from northern Italy and 33 from Belgica and the Germanies, and to Lefebvre (Reference Lefebvre, Dondin-Payre and Raepsaet-Charlier2001, 597), who notes that in the Gallic language ver– meant ‘above, strong, or very’ and condo meant ‘reason, intelligence’, so that Verecundus would suggest to a Gaulish-speaker ‘superior intelligence’. By contrast in Latin, the name (like the common adjective uerecundus) would have suggested ‘modest’ or ‘reserved’.

Like other commanders of ethnic units from this region, Verecundus could well have been a Tungrian himself (Tab. Vindol. II, p. 25) or at least have originated from the wider Lower Rhine area, a supposition supported by his gentilicium Iulius. But without clearer evidence we cannot exclude an origin in the wider Gaulish area, or even (but this would be much less likely) in Italy.

IV. THE TEXTS

For editorial conventions used in the editions below, see Tab. Vindol. III, p. 19. All the texts published here are written along the grain of the wood. In the headings we record the overall dimensions in the form ‘(width) × (height)’.

890

Inv. no. WT 2017.15. Dimensions: 212 × 58 mm. Period I. Location: V17-52B, above Period I extramural road (figs 3–4).

FIG. 3. 890 Front. 212 × 58 mm. Letter of Iulius Verecundus to his slave Audax.

FIG. 4. 890 Back. Address of letter of Iulius Verecundus to Audax.

Two facing leaves of a diptych, complete except at the bottom, which is broken. Unusually, it is made of oak. The position of the tie-holes and the notches in the edge of each leaf suggests that there is a substantial amount of loss, probably enough for two lines at the foot of the first column and a corresponding amount of space in the second. The remains of an intercolumnar addition (see note to ii.6) suggest that the text in column (ii) continued to the bottom of the leaf. The front is written in two columns by a practised hand. There is interpunct after most words as noted in the transcript, and probably elsewhere, where it is no longer clearly visible. On the back, towards the bottom of (ii), the abraded remains of an address in elongated letters; (i) is blank.

Iulius Verecundus writes to his slave Audax about the transport of part of a load of vegetables and about the wrong key to a box which Audax has sent.

Front:

i

Ị[u]ḷ[iu]s Vẹrẹcundus Audạci ·

salutem

cumprimum fieri · potuerit

mitte · .aṇ. · paṛṭem · ueṭụ-

5 ram · quam hodie · ad uos ·

dimisi · caḅallis · duobus · s[o]lutịs

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ii

laedatur · ạ uẹḷạtura · in qua

aḍferetur · uiridia · hoc esṭ

cymas · et holorac̣ias · et ṇạpi-

c̣ias · eaque mitte · claueṃ

5 quọque aliam misisti cum

cistạ · quam debueras · haec

enim ḥọrrioli · ḍic̣ịtur

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Back:

Ạ[u]ḍ[a]ci Iuli Ṿ[ere]cun-

ḍị seruo

‘Iulius Verecundus to Audax, greetings. As soon as it will have been possible, send in the morning(?) part of the load which I have today dispatched to you (plural) with two loose horses … lest it be damaged by the conveyance in which the greens will be brought, that is the shoots both of cabbage and of turnip, and send them. Also you sent another key with the box than you should have done, for this is said to be (the key) of the little storeroom …’

[Back] ‘To Audax, the slave of Verecundus.’

(i)

1, I[u]l[iu]s Verecundus. Verecundus’ gentilicium is very abraded (only the final s is clear), but it can be read in the address on the back. Although his rank is not explicit, even if implied, this is undoubtedly the prefect Iulius Verecundus.

1, Audaci. The recipient is identified on the reverse as the slave of Iulius Verecundus, which would explain the peremptory tone of his letter: Verecundus does not add suo to the recipient's name, and twice uses the abrupt imperative mitte. Audax is not a common cognomen, probably because the adjective was used in a pejorative sense (‘over-bold’), but it is quite understandable as a slave's name. It is found at Corbridge (RIB II.6, 2494.104 and Britannia 49 (2018), 446, no. 39), for example, but there is no reason to think this is the same man. It also occurs twice at Vindolanda, in 186 (an account, in which ‘Audax’ provides quantities of salt and meat) and in 590.2 (an inventory). Neither is readily identifiable with the Audax of the present text: 186 is much later, being explicitly dated by the consuls of a.d. 111, while the period from which 590 derives is uncertain.

3, cumprimum. Written as a single word (there is no space after cum, let alone interpunct). The tall p is noteworthy (contrast that in partem and napicias): a ‘capital’ letter, anticipating the New Roman Cursive form.

4, mitte. The horizontal stroke of t is quite short, as elsewhere in this hand. Verecundus does not say where the part-load (see next note) is to be sent. The natural implication would be that it should be sent to himself, but this cannot be so, since he has just ‘dispatched’ (dimisi) the whole ‘load’ (ueturam) to Audax. Instead, he must be alluding to an arrangement they have previously made, that ‘part’ (partem) is to be sent on to another destination. Since Audax already knew where this was, Verecundus felt no need to spell it out.

4, .an. partem. Reading and interpretation are difficult. The two words are separated by an interpunct, and the second is quite acceptable as partem, given that p and r, despite being unlike the bold p and r in cumprimum (3) above, are conventional in form. (For p, compare the first letter of potuerit.) We then follow Adams (Reference Adams2019) in seeing partem ueturam, not as a mistake for partem ueturae, but with the accusative ueturam in partitive apposition to partem; the meaning would be the same, a ‘part-load’.

The problem is whether this ‘part’ was qualified in any way. For the problematic first word (4 letters, possibly 5) we have considered the readings hanc (‘this’) and even ferme (‘almost’), but we think it must be mane (‘in the morning’). It begins with two downstrokes, which might be seen as h which has lost its cross-stroke, but this would not explain the short horizontal stroke which links the second downstroke to the downstroke of the next letter, which is certainly a. Instead, we think the first letter must be m which has lost its second stroke. It is followed by a, as we have said, which itself is followed by n, unless the rather faint horizontal stroke to its right be taken as the fourth stroke of m. But this stroke extends across the next (and final) letter, making it e rather than c. c could only be read by taking the stroke as part of m, which would then preclude c as the next letter.

4–5, ueturam. This substandard form of uecturam, with ct assimilated to t (Adams Reference Adams2013, 166–9), has already occurred in 600.ii.2. The ‘correct’ form uectura is also found at Vindolanda, in 649.ii.13 and in two stylus tablets (Inv. nos 836 and 975, for which see Bowman and Tomlin Reference Bowman, Tomlin, Bowman and Brady2005, 10–11), as well as in a London writing-tablet (Tab. Lond. Bloomberg 45.6); but all these instances are abstract in meaning, ‘carriage’ in the sense of ‘transport-charge’. In the present context ueturam, as the object of the verbs dimisi and (probably) mitte, must be concrete in meaning: a ‘carriage’ or ‘wagon’; and by extension, a ‘load’. At Vindolanda the term carrulum is used for a ‘wagon’ (315.2, 316.1), where the editors note its association with uectura in the Digest 17.2.52.15, carrulorum uecturas.

5, uos. This letter is addressed to a single recipient (compare mitte in 4), and the shift to the second-person plural pronoun implies ‘you and the others associated with you’ (Adams Reference Adams2003, 550). uos is used thus in 622.b.2 and 643.back.3, greetings addressed to a single person.

6, caballis duobus s[o]lutis. caballus as usual in the tablets (182.13, 632.2, 647.5) is the term for ‘horse’, with no instance yet of equus (Adams Reference Adams2003, 563–4). In duobus, the final u has been ligatured to s. This is immediately followed by a second s, and a space (in which we restore o, of which there is now no trace), before lutis which extends into (ii). There is no good trace of the downward diagonal of l, but this is true also of l in salutem (2), and the l of laedatur (ii.1) shows it would have been slight in any case. The verb soluere is used of ‘unharnessing’ or ‘unyoking’ transport animals (OLD s.v. soluo 5b), so the phrase means ‘(with) two unharnessed horses’. Since the text breaks off at this point, we cannot be sure that caballis duobus solutis should be taken with ueturam … dimisi rather than beginning a new sentence, when it would mean ‘After unharnessing the two horses …’ But it is difficult to see how this would be preliminary to the onward movement implied by uelatura (ii.1), so we prefer to take caballis duobus so[l]utis with dimisi (etc.), even if it is also difficult to see a wagon (or load) being sent to Audax ‘with two loose horses’: surely they would have been pulling it? The explanation may be that Verecundus sent it to him by other means, perhaps by wheeled cart and oxen, and provided the pair of loose horses to take the part-load on further, perhaps even because wheeled traffic would no longer be feasible and pack-horses were needed.

(ii)

1, laedatur. The beginning of this new sentence has been lost with the bottom of column (i), and its content can only be guessed. The subjunctive suggests a final clause: Verecundus was guarding against damage in transit, [ne] laedatur, ‘lest it be damaged’.

1, uelatura. This is the third instance of the word from Vindolanda, the others being 649.ii.11 and 13, where the editors do not commit themselves to a translation but cite the only instances in Classical Latin (Varro, Ling. 5.44; Rust. 1.2.14), where it means ‘transport’, ‘carriage’. Since it is followed here by in qua adferetur, its present meaning must be concrete: the ‘conveyance’ in which the part-load (presumably) is brought.

2, uiridia. ‘Green things’, in the sense of ‘vegetables’ (OLD s.v. uiridis 4b) which are then (3–4) specified. uiridia is neuter plural in form, but is evidently singular here as the subject of adferetur: neuter plurals sometimes switch number and gender to feminine singular while retaining a collective meaning (Adams Reference Adams2013, 415–17).

3–4, cymas et holoracias et napicias. OLD translates cyma as ‘the spring shoots of a cabbage or similar vegetable’; it is a Greek loan-word which, although neuter, is often treated as feminine in Latin. Here cymas is accusative plural, and two varieties are defined by adjectives derived from the vegetables concerned. They are fully discussed by Adams (Reference Adams2019), who derives holoracias from holus (‘vegetable’, especially ‘green vegetable’) and napicias from napus (‘swede’, ‘turnip’).

4, eaque mitte. We follow Adams (Reference Adams2019) in taking ea as a resumptive pronoun summarising the items listed, followed by a repetition of the imperative mitte (i.4). clauem (ii.4) might ‘also’ (quoque) be the object of mitte, with aliam misisti (etc.) beginning a new sentence to explain why the key should be sent, but the syntax would be rather abrupt. It is easier to understand quoque as ‘joining clauses or sentences, the adverb attaching to the whole rather than any individual word’ (OLD s.v. quoque 2c), so that clauem introduces a new sentence and a new topic (the wrong key).

6, cista. There are traces of ink in the margin to the left (corresponding to others in the line below), as if the line were extended left in ekthesis to mark a new sentence. But 5 ends with the preposition cum, which anticipates cista. These traces should therefore be read at right-angles, as an intercolumnar addition (see, for example, 643 and 645), and be understood as the beginning of a word m[ which was added in the left margin because the writer had run out of space at the bottom. cista is a ‘box or chest’, but is also used in the special sense of one ‘for holding sacred objects used in celebration of mysteries, etc.’ (OLD s.v. cista b). See further, next note.

7, horrioli. The reading and interpretation are difficult. The first two letters are incomplete, but the first consists of a downstroke, a horizontal, and a second downstroke, just like h in haec (6) above; the second letter is a short downstroke which might be either part of o, or the downstroke of a without the second, diagonal stroke. We have considered two possibilities: horrioli as a diminutive of horreum (‘storehouse’) with e>i in hiatus, uniquely attested in Valerius Maximus 7.1.2; and harrioli, which is unattested, but conceivably a variant spelling of hariolus (‘soothsayer’) in the genitive case. The association with cista (see previous note) prompts the idea that Verecundus was referring to a particular box or chest known to his household (including his slave Audax) by a facetious term for which he apologises, as it were, by putting it within quotation marks (dicitur): the key of the ‘soothsayer's box’. But Adams (Reference Adams2019) would expect the explanatory sentence introduced by enim (7) to refer back to the subject of the previous sentence (the key) rather than to a prepositional expression within it, and we prefer the easier and less fanciful interpretation, that the (wrong) key is that ‘of the small storeroom’. Verecundus’ phrase recalls Pliny's reference (Hist.Nat. 14.89) to ‘the keys of the wine cellar’ (claues cellae uinariae). Müller illustrates a wide range of keys and locks, including a well-preserved wooden chest with lock-plate (Reference Müller, Reuter and Schiavone2011, 33, Abb. 13) which Verecundus’ cista might have resembled.

Back

The address is abraded, but the remaining traces are altogether consistent with the inner text. In the first line, only the lower tip survives of the exaggerated downstroke of a, which reaches to the left of the second line. It is the first letter of Audaci, its exaggerated length marking it as the beginning of the address. Iuli is quite well preserved, and so is un at the end of the line, preceded by the ascending diagonal of c. The second line begins with di, then quite a wide space, and a well-preserved seruo (‘slave’) with possible trace of an apex above and to the right of o. Since the tablet is broken here, it is impossible to tell whether the address continued further, for example with a Iulio Verecundo praef(ecto) (‘from the prefect Iulius Verecundus’).

891

Inv. no. WT 2017.16. Dimensions: 185 × 56 mm. Period I. Location: V17-52B, above Period I extramural road (fig. 5).

FIG. 5. 891 Front. 185 × 56 mm. Letter of Andangius and Vel[…] to Verecundus.

Five joining fragments of a diptych. The left- and right-hand edges are complete, to judge by the symmetrical placing of the tie-holes and notches, and the space left at the end of the last line (12). The top and bottom edges survive to left and right, but are lost in the middle.

The back is blank, except for possible traces on the back of the upper piece of (i): they might be lettering, but if so, they are very smudged and faint. The front is written in two columns, in a rather crude hand which exaggerates the diagonal of a and n, and extends the upper diagonal of e and s. This is most evident in the first word, the name of the first author, Andangius (see further, note to 1). There appears to be no instance of ligature or interpunct.

Andangius and a colleague write to Verecundus, asking for a favour for the mensor Crispus.

(i)

Andangius et Veḷ[

rogamus te domin[e]

Verecunde per notis-

simam iustitiam tuaṃ

5 dignos nos habẹ[a]s [et]

praestes ut c̣ị[uem et]

(ii)

[amicum] nostrum nomi-

[ne] C̣rispum mensorem

facias ụt p̣ossịṭ bene-

10 ficio tuo ḷẹuius miḷitare

ẹ[t] genio tuo gratias age-

[re d]ẹḅeṃụṣ uacat

‘Andangius and Vel[…] (we) ask you, lord Verecundus, by your very well known justice, to consider us worthy and to undertake that you make it that our [fellow-countryman and friend], by name Crispus the mensor, may be able by your kindness to have a lighter military service; and we (will) owe thanks to your genius.’

(i)

1. The first line is in ekthesis, as is common in personal letters; here it is imposed by the tie-hole. Andangius is a Germanic name attested in the Rhineland by CIL xiii 7086 (Mainz), Gamuxpero Andangi (filio); compare CIL xiii 2945 (Sens), Andangianius Tertinus, a veteran married to a woman from Cologne. It is already attested at Vindolanda by Britannia 34 (2003), 379, no. 40, the owner's name Andangiu[s] scratched on a South Gaulish samian bowl (Drag. 37). Since this vessel is Flavian, he is probably the same man, but the hands cannot be closely compared since the graffito is in capitals, although G looks quite similar. The association of the name with Gamuxperus in CIL xiii 7086 suggests that [Gamu]xperus, not [U]xperus, should be restored in 184.23.

1, et Vel[…]. Of the second author's name, only the first two letters are certain. The third terminated in a short rightward hook appropriate to l (compare that in militare, 10), but also to p or t. However, names in Vep– are almost unknown and there is no sign of the leftward horizontal of t. Vel– would suggest a Germanic name like Vel(de)deius or Velbuteius, both found at Vindolanda (310).

2, domin[e]. There is trace of ink after n, but it is not much like e; however, in this context the vocative domine is inevitable. A short space must have followed, the writer preferring to begin Verecunde in the next line.

4, tuam. The apparent trace of m is very slight, and it is possible that the letter was omitted by mistake.

2–5. The formulation recalls that of requests for leave (commeatus, 166–76) with their formulaic phrases rogo domine and dignum me habeas, but this is clearly not the case here. Instead, the authors have adopted these formulas and reinforced them with an appeal to the ‘justice’ of Verecundus, so as to ask a favour for their friend Crispus. Although this amounts to a letter of recommendation, it is not cast in epistolary form with salutem (etc.) at the beginning and good wishes at the end; it is a petition like the requests for leave, which are likewise headed by the petitioner's name but not addressed to the prefect directly in the dative case; instead he is invoked by the phrase rogamus te domin[e] (2). The use of beneficio tuo (9–10) and genio tuo (11) reinforces this sense of petition.

6, ci[uem et]. After ut there is quite good trace of c like that in Verecunde (3), rather than p, s or t, and it is followed by the tip of a short vertical stroke. To judge by the lines above, 4–5 more letters have been lost. See further, next note.

(ii)

7, [amicum] nostrum. 6–7 letters have been lost before nostrum, to judge by lines 9 and 10. collegam would be too long, but amicum is an easy restoration: for the phrase ci[uem et amicum] nostrum, compare 650.5–8, saluta (names) et omnes ciues et amecos [sic] (‘Greet the persons named and all my fellow-countrymen and friends’). The editors there note that ciues is well attested with the meaning ‘fellow-countrymen’, ‘compatriots’, but add that it is normally used with the possessive, ciues meos, nostros. It is thus used here: Andangius and Vel[…] mean that Crispus is their ‘fellow-(Tungrian)’, and by also calling him their ‘friend’, they explain their interest in him. Compare 892.2 with note.

7–8, nomi|[ne] Crispum. 2–3 letters have been lost before Crispum. Photographs suggest they ended in a faint diagonal, but inspection of the original shows that this is only a ‘step’ in the broken edge. Crispus is a common Latin cognomen, but a man of this name in the First Cohort of Tungrians is named in 295.3 as bearing letters to the governor; the identification is tempting and perhaps not to be ruled out, even though 295 is from the later Period IV. The term of military service, after all, was 25 years.

8, mensorem. Crispus is called a ‘measurer’, without the full meaning being made explicit. For Vegetius (2.7), the legionary mensor was a surveyor of land or buildings; his duties would have included the layout of camps and forts, making maps and planning the course of roads (Sherk Reference Sherk, Temporini and Haas1974, 544–58). But an anonymous reviewer reminds us that the Carvoran modius (RIB II.2, 2415.56) dates from this period (a.d. 90–91), and suggests that Crispus may have been a mensor frumentarius responsible for measuring the corn-ration: at least four legionaries are thus identified, for example the veteran Lucius Titius (ILS 2423). OLD defines mensor as ‘One who measures or computes; esp. (b) a land-surveyor / surveyor of building works; (c) one who measures out grain’.

The problem is that the term was used without qualification. At least ten inscriptions identify individual legionaries as mensor, but only three or four explicitly as agrimensor or similar, for example ILS 2422a, me(n)sor agrari[us]. 16 mensores are listed by name in Legion III Augusta (AE 1904, 72), and in Legion VII Claudia they amounted to an association (schola mensorum): a dedication to its genius was made by the disp(ensator) horr(eorum), his ‘supervision of the granaries’ implying they were responsible for the corn-ration (AE 1973, 471, compare CIL iii 12656). On the other hand, there is ample support for Vegetius’ assumption that the mensor was a surveyor. In Britain itself, apart from 650 (back 2), which is addressed to a mensor whose name is now lost, the only instance is RIB 1024 (Piercebridge), an altar dedicated by a men(sor) euoc(atus): he was a Praetorian who had been retained in service as an expert, like Iulius Victor, who was consulted by a proconsul to settle a boundary-dispute, adhibito a me Iulio Victore euocato Augusti mensore (ILS 5947a). At least five Praetorians are named in inscriptions from Rome as mensor without qualification. Vespasian, to settle another boundary-dispute, wrote to the procurator of Corsica and ‘sent a surveyor’ (mensorem misi, CIL x 8038); and the younger Pliny, to check on building contracts in Bithynia, asked Trajan in Rome for a mensor, only to be told they were available in every province (Ep. 10.17b and 18).

There is little evidence of mensores in auxiliary units, perhaps only mensor coh(ortis) I Asturum (CIL xiii 6538) and me(n)s(or) c(o)h[o]rtis Hispanorum, a cavalryman (AE 1983, 941 with 1985, 343), but note Aurelius Malchus, disc(ens) mens[orem] in cohors XX Palmyrenorum (RMR 50 i 3, 9), since he was a trainee with the implication that this was a skilled post. See further, next note.

9–10, ut possit beneficio tuo leuius militare. Much the same phrase is used by a would-be soldier writing to the prefect of Egypt: u[t po]ssim beneficio tuo … mili[tar]e (Speidel and Seider Reference Speidel and Seider1988); and indeed by the prefect Cerialis in thanking his own patron for making his military service pleasant: ut beneficio tuo militiam [po]ssim iucundam experiri (225.22–4). It is conceivable that Andangius and Vel[…] are asking that Crispus be made a specialist excused heavy duties, their reference to ‘lighter service’ (leuius militare) being echoed by the preamble to a second-century list of immunes preserved by the Digest (50.6.7), incidentally headed by mensores: certain soldiers are ‘granted by their conditions of service some exemption from the heavier fatigues’ (quibusdam aliquam uacationem munerum grauiorum condicio tribuit, ut sunt mensores …). But would Andangius and Vel[…] have ventured to recommend their friend on the grounds that the post was an easy option? Also it is most unlikely that a prefect could simply ‘make’ someone a surveyor, since the post required special expertise; some are even identified as trainees (discens), like Aurelius Malchus just mentioned. On balance we prefer Adams’ explanation (Reference Adams2019) that Crispum mensorem is a proleptic accusative, ‘in effect the subject of the verb in the dependent clause (here possit)’, whose conditions of service are to be improved.

11–12, genio tuo gratias age[re]. Again, this phrase is used by the would-be soldier in Egypt (Speidel and Seider Reference Speidel and Seider1988, citing parallels): genioque tuo gratias ag[am]. As Adams (Reference Adams2019) observes, the language is deferential: the authors are writing to their military superior, but since they are asking for a favour, they use the language of clients to their patron.

12, [d]ebemus. Syntactically the subjunctive [d]ebeamus or [d]ebeatur might be expected here, dependent on ut (9) like possit, but the traces do not support it. The second e is located by the distinctive leftward hook of b above the broken edge to its left. The letter after this e most resembles e again, but can be taken as the first element of m smudged upwards, especially since it is followed by reasonable traces of the second element and then of u and s. a would require a bold diagonal, of which there is no sign. debemus might be a slip for debeamus, but we follow Adams (Reference Adams2019) in understanding this present (indicative) as referring to the future, with the verb debere gaining a transitional sense from ‘ought’ to ‘will’.

892

Inv. no. WT 2017.24 + 26. Dimensions: 222 × 66 mm. Period I. Location: V17-52B, above Period I extramural road (figs 6–7).

FIG. 6. 892 Front. 222 × 66 mm. Letter of Masclus to Iulius Verecundus.

FIG. 7. 892 Back. Address of letter of Masclus to Verecundus.

A complete diptych, with the usual notches and tie-holes, each half broken into four pieces. The letter is complete and there is an address to Verecundus on the back of the right-hand leaf (ii), with the name of the sender at the bottom left, but no sign of a destination place-name at the top left. Found with it was a detached fragment (Inv. no. WT 2017.26), 40 by 15 mm, with the remains of two lines of writing on one face, which does not belong to 892. It is not published here.

The hand is a well-formed cursive of the kind common at Vindolanda, with the letters (no unusual forms) clearly formed without ligatures, and with occasional use of interpunct. The text on the front is all written by one hand, with the possible exception of the concluding uale (15), a hand probably responsible also for the address on the back. The format of the opening address on the front is unusual, since it is all written in one line with sal(utem) (1) abbreviated (see note). The sender is the decurion Masc(u)lus who also appears in 628, 586.ii.4 and perhaps 505. The main text of 892 is definitely not by the same hand as 628, but it might have been written by Masclus himself; this, however, would not be so if the closing greeting uale (15) were in a second hand, but this is not certain.

The dating of the tablets relating to Masclus, the nature of his command, the relationship between him and Verecundus, all present problems which we cannot resolve. It would seem that Verecundus received this letter at Vindolanda, and that Masclus was stationed somewhere nearby in command of a cavalry vexillation, but we cannot go further than this without resorting to pure speculation.

Of the three other tablets which certainly attest Masclus, 586 (an account) and 628 (a letter) belong to Period III, when the unit based at Vindolanda was the Ninth Cohort of Batavians, and Appendix 505 (an address) to Period II. The letter (628) from the decurion Masclus to the prefect Flauius Cerialis (addressed as regi suo) was the main basis for the editors’ conclusion that the Ninth Cohort was by then part-mounted (equitata) and probably double-strength (milliaria). It is not impossible that Masclus was present and in post in Periods II and III, but it is more difficult to explain the present letter (892) from Masclus the decurion to Verecundus the prefect of a unit (‘domino suo’) which was not part-mounted, and therefore did not have decurions. We should perhaps be more ready to envisage correspondence of this sort between officers of different units and different ranks. We note that another of Verecundus’ correspondents was the decurion Cornelius Proculus (Inv. no. WT 2017.34, not yet published).

A further complication is that Masclus requests leave from Verecundus for five men who are neither Tungrians nor Batavians — two Raetians and three Vocontians — all of whom he describes to Verecundus as being ‘under your charge’ (sub cura tua). This description, and his failure to specify their unit(s), suggests either that they were members of the Tungrian cohort (see further, below) or that they somehow fell under Verecundus’ authority without actually being members of his (or Masclus’) unit. Perhaps they had been detached from other places or units in the area, which would support the idea that the deployment of individual soldiers and groups, and the bureaucratic procedures for requesting and granting leave (166–177 with Tab. Vindol. II, pp. 77–8), were much more flexible than has previously been thought.

Masclus writes on two subjects. First, a request for leave for five men. Having begun with three names, he then crossed out the numeral and replaced trium with quinque (below the line), crossed out one of the names and added three others. Second, he requests the return of a cleaving-knife and reports that he has sent Verecundus some plant cuttings.

Front:

i

Masclus Verecundo suo sal(utem)

petierunt a me ciues · Reti · ut

peterem abs te · commiatum 〚trium〛 ̀quinqué

Retorum qui sub cura tua

5 sunt Litucci · 〚Vitalis〛 et Vict-

oris · et de Vocontis · Augusta-

num · Cusium · Bellicum

ii

et rogo domine · ut iubeas re-

ddi · cultrum scissorium qui

10 penis · Ṭalampum (centuriae) Nobilis

quia nobis necessarius est

missi tibi · plantas ịị

. per Talionem tur(ma) Pere-

griniana · opto te · felicem et tuos

15 uacat (?m 2) uale uacat

Back:

Iulio Verecundo

prefecto

ab Masclo dec(urione)

‘Masclus to his Verecundus, greetings. The Raetian (tribes)men have asked me to request from you leave for 〚three〛 five (men); of the Raetians who are under your charge, Lituccus 〚Vitalis〛 and Victor, and from the Vocontii, Augustanus, Cusius, Bellicus. And I ask, my lord, that you order the return of the cleaving-knife which is in the possession of Talampus, of the century of Nobilis, because it is needed by us. I have sent you the plants, 2 … through Talio, of the Peregriniana troop. I hope that you and yours enjoy good fortune. (?2nd hand) Farewell.’

[Back] ‘To Iulius Verecundus, prefect, from Masclus, decurion.’

1, Masclus Verecundo. For the name Verecundus, see above. For the name Masclus, meaning ‘masculine’, OPEL (III, 63, without the Vindolanda tablets) lists 67 examples, with the spelling almost equally divided between Masclus and Masculus. The main distribution is: 28 from Noricum, 9 in Narbonensis and 8 in Belgica and the Germanies.

1, sal(utem). This abbreviation also occurs in 871.2, where we note that it is ‘extremely unusual in the tablets, though common enough in MSS’; the only other possible example at Vindolanda seems to be 298.a.2. It also occurs in Tab. Lond. Bloomberg 27.2, where it is noted that Cugusi cites nine instances in CEL.

2, ciues Reti. The term civis here does not mean they were Roman citizens. It is frequent in the epitaphs of auxiliary soldiers, with the addition of the tribe from which they come, for example on the Lancaster tombstone (RIB III, 3185), cive(s) Trever; compare RIB I, 108, ciues Raur(icus) and 159, ciues Hisp(anus). An exact parallel is a third-century legionary's tombstone from Italy (AE 1982, 258), civis Retus. The spelling Retus<Raetus is one of many instances of the diphthong ae being written as e since the pronunciation was the same.

This is the earliest evidence of Raetians serving in Britain, but the cohors V Raetorum is attested there by the diploma of a.d. 122 (CIL xv 69) and cohors VI Raetorum by lead sealings (RIB II.2, 2411.147–51) and in a.d. 166–9 at Great Chesters (RIB I, 1737). Also in the Antonine period, Raetians were serving in the Second Cohort of Tungrians at Birrens, c(iues) Raeti milit(antes) in coh(orte) II Tungr(orum) (RIB I, 2100). It is quite conceivable that, although much earlier, there were Raetians in Verecundus’ cohort also.

3. Adams (Reference Adams2019) comments on the use of abs for ab, and commiatus for commeatus.

3, quinque. As already noted, this is a correction for trium. Such corrections are normally written above the line but (unusually) this one is below the line.

3, commiatum (for commeatum with closing of e in hiatus). Other Vindolanda applications for leave (166–77, invariably commeatum) are made by the soldier concerned, but for another instance of leave being sought on someone else's behalf Konrad Stauner (pers. comm. to Anthony Birley) compares an ostracon from the fort of Didymoi in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, in which Numerius offers to ask for leave on behalf of Longinus (O. Did. 344).

5–6, Litucci … et Vict|oris. OPEL (III, 29) cites only three instances of the name Lituccus, from Italy, Gallia Belgica and Narbonensis. Victor is very common. The word-division of Vict|oris between the lines is unexpected (Vic|toris would be normal) and it is noticeable that the t is raised above the line, as often with the last letter of an abbreviation. Perhaps Vic|oris was written first by mistake, and then corrected by the insertion of t. For other examples of false word-division see 225.11–12 and 343.32–3.

6, de Vocontis. The Vocontii are presumably members of the ala Vocontiorum, first attested in the army of Britain by the diploma of a.d. 122 (CIL xvi 69), but likely to have been there earlier (compare CIL xiii 8805). The word occurs in 316.i.6 and margin.1, where it might be understood either as a personal name or the eponym of a centuria.

7, Cusium Bellicum. Recognition that three names were corrected to five requires us to take Cusium and Bellicum as separate names. Bellicus is a common cognomen. Cusius is more often found as a gentilicium, but does occur by itself as a cognomen in Lusitania (OPEL II, 89) and Raetia (AE 1999, 1178, as corrected in AE 2014, 961). It is also the name of a samian potter at Rheinzabern (Hartley and Dickinson Reference Hartley and Dickinson2008, III, 228 s.v. Cusius).

9, cultrum scissorium. The adjective is previously unattested, but must derive from scissor (‘carver’), which has already occurred in 680.a.1 but in an unknown context. We follow Adams (Reference Adams2019) in seeing it as a ‘cleaving-knife’ used for taking plant-cuttings; compare Virgil's use of the related verb abscindere in referring to the process (Georgics 2.23–4): hic plantas tenero abscindens de corpore matrum | deposuit sulcis. The word used by Pliny (Hist.Nat. 17.119) for a grafting-knife is scalprum, and it is appropriately associated with an axe and gaiters in the Ratcliffe-on-Soar curse tablet (Britannia 35 (2004), 336, no. 3), but Masclus must have been referring to a particularly long and heavy knife. Manning is careful to distinguish between ‘cleavers intended for chopping rather than knives used for slicing’ (Reference Manning1985, 120), but something like his Type 17 or 18b (Reference Manning1985, 116–17) may have been meant.

10, penis Talampum. penis is a misspelling of penes, as Adams (Reference Adams2019) notes: the reading is certain, with i clearly differentiated from e. We are also confident of Talampum, although the name is unparalleled: the first letter is t with its horizontal stroke incompletely made, not c (which in this hand is usually curved). It might be a variant of the common name Thalamus, with t for th as in Ta[la]mus (CIL vi 35945); the femine form Talame is cited in a note to ILCV 2810 E.

12–13, plantas ii| . per Talionem. We follow Adams (Reference Adams2019) in understanding plantas as ‘plants’, in the sense of ‘a young shoot detached from the parent-plant for propagation’ (OLD s.v. planta, second entry). But the quantity sent by Masclus remains a serious difficulty. At the end of line 12, we considered reading a large n with a suprascript bar for n(umero) (‘in number’), but there is no sign of the diagonal stroke required, and the obvious reading is two digits with a suprascript bar for ‘2’, even though ‘two plants’ seems a trivial consignment. The real problem is the trace of one letter, possibly two, at the beginning of line 13 before per Talionem: if the preceding numeral ‘2’ is correct, nothing is needed here at all. We cannot read this trace as m for m(odii) (‘bushels’), which in any case should always precede the numeral. p for p(ondo) (‘by weight’) looks better palaeographically, but it would likewise be in the wrong position and would make no better sense.

13, Talionem. The name Talio is uncommon, but is found at Vindolanda as a graffito on samian (RIB II.7, 2501.532); however, this is not the same man, since the vessel is late Antonine. The name is also found in RIB III, 3231 (Brougham).

13–14, tur(ma) Pere|griniana. Cavalrymen were identified by their troop, with turma (often abbreviated, as here) in the ablative case (as here) or genitive. The adjectival form Peregriniana means that Peregrinus was the last troop-commander (decurion), but there was none at the time of writing. The duplicarius would have been second-in-command, but it is likely that Masclus, as a decurion, was commanding a vexillation consisting of two turmae, his own and another.

14, opto te felicem et tuos. The infinitive esse is easily understood; there is no need to suppose it has been lost below. We have not found an exact parallel for the phrase, but compare CEL 141.35–6, bene ualere te opto multis annis cum tuis omnibus.

15, uale. As already noted, this may have been written by a second hand, but there is too little left to be sure. If by a second hand, it would have been written by Masclus himself.

Back

As usual the name of the sender is written on a slant. There might be a diagonal abbreviation stroke after dec.

893

Inv. no. WT 2017.18. Dimensions: 192 × 32 mm. Period I. Location: V17-52B, above Period I extramural road (figs 8–9).

FIG. 8. 893 Front. 192 × 32 mm. Letter of Caecilius Secundus to Iulius Verecundus.

FIG. 9. 893 Back. Address of letter of Secundus to Verecundus.

Four joining fragments of the upper half of a diptych, its two incomplete leaves consisting of two joining fragments each. The placing of the leaves is confirmed by the wood-grain extending from one to the other, and by the protracted fourth stroke of m in salutem (i.2) extending into (ii), where it is cut by d, the first letter of ii.3. The top edge of both leaves is original, and so is the left edge of (i) and the right edge of (ii), but the bottom edge of both is broken. Slight notches on either side, 23 mm below the top edge, presumably mark the binding-cord; and if central, they would suggest that about three lines have been lost at the bottom of each leaf. The front is written in two columns, (i) and (ii); and on the back of (ii) is one line of the address written in elongated letters. The back of (i) is blank.

Found with these four fragments (and sharing the same inventory number) were three very small fragments, not conjoining or inscribed; and a larger fragment with writing (Descriptum, below), which belonged to another tablet.

The final s of Caecilius (i.1) runs into the initial s of Secundus, but otherwise there is interpunct between most words in (i) and (ii), the exceptions being sciret se id (i.4) and de qua re commodius (ii.3). This is remarkably consistent by Vindolanda standards. There is an apex above o in Verecundo (i.1), suo (i.2) and Decumino (i.3), and on the back, above o in Iulio and Verecundo.

Front:

i

Caecilius Secụṇḍus · Vẹrecuṇḍó

suó · salutem

Decuminó · (centurioni) · ti[li]ạs · quas · mihi · scri-

4 pseras · ostẹ[ndi ut] sciret se id

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ii

corporis · sed · iracuṇd ̀í olae · quae · cas-

ṭigatiọnem · a seṇioribus ·merèńtur

de qua re commod[i]us · est · ut tecum

praesens · ạ[ga]m · in · praesentia ·

5 scito · omṇ[es] ḍecuriones · huius · numeri

traces [

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Back:

Iulió Vẹṛecundó

. . . . . . . . . . . .

‘Caecilius Secundus to his Verecundus, greetings. The tablets which you had written to me I have shown to the centurion Decuminus, that he might know that he … it […] || [… ?not] of body […] but little outbursts of anger which merit castigation by one's seniors. Concerning which matter, it is more convenient that I discuss it with you in person. For the moment know that all the decurions of this unit …’

[Back] ‘To Iulius Verecundus […]’

(i)

1, Caecilius Secundus. l is very short, with rightward extension at top and bottom; quite unlike the very long l of salutem (2), but like the l of iracundiolae (ii.1). As already noted, the final s of Caecilius runs into the initial s of Secundus. At the end of both names, u is linked to s, as in senioribus (ii.2) and huius (ii.5).

Caecilius Secundus refers to ‘all the decurions of this unit’ (ii.5, omn[es] decuriones huius numeri), which must have been an ala or a cohors equitata. His emphasis on ‘all’ the decurions suggests that it was an ala with 16 decurions rather than a cohors equitata with only four. He can hardly have been a decurion himself representing the consensus of his colleagues to Verecundus, since he writes to him without any of the deference accorded to Verecundus by decurions in their letters (891, 892, Inv. no. WT 2017.34). He treats him as an equal with whom he will have a man-to-man discussion (ii.3–4); he was surely a prefect himself. Other persons called ‘Caecilius Secundus’ are known, including Pliny the younger, but an attractive and plausible identification is with the patron to whom Martial dedicates Book 7 of his Epigrams (7.84). This Caecilius Secundus ‘holds’ a conquered area near the mouth of the Danube (haec loca perdomitis gentibus ille tenet), probably in Domitian's Sarmatian War of a.d. 92. He was probably an equestrian officer (Devijver C24, fortasse). If he is indeed the same man, he must have been transferred there after holding a prefecture in Britain contemporary with that of Verecundus (c. a.d. 85–92).

3, Decumino (centurioni). The downstroke of c was made twice, as if to correct a mistake. The name is in the dative, governed by oste[ndi], and followed by a centurial sign, its position indicating that it means ‘centurion’, not ‘century’, which would have preceded the name in the genitive case like (centuria) Nobilis in 892.10. Decuminus was evidently subordinate to Verecundus (see further below), but whether he should also be identified with the centurion Decmus in the Descriptum (below) is discussed there.

3, ti[li]as. ‘Limewood’, in the sense of ink wooden leaf tablets: for other instances of this term, see Tab. Vindol. III, p. 13, and 589, 643 (with note to a.ii.4), 707, Appendix 259.

4, [… ut] sciret se id […]. The text breaks off here, but probably continued by specifying the action required of Decuminus by Verecundus, in language such as id [quod volebas facturum esse si …], ‘… that he might know he would be doing what you wanted if he …’. Secundus is apparently passing on instructions from Verecundus to Decuminus as a centurion of Verecundus’ unit.

(ii)

1, corporis. The antecedent is lost, but since it is contrasted with iracundiolae it was probably a plural noun such as iniuriae (‘insults’); Secundus is complaining, not of actual physical affront, but of words spoken in temper. The second i of iracundiolae was supplied by insertion afterwards above the line, like n in merentur (2). This diminutive of iracundia (‘anger’), although it is found in Gassendi's Letters (Reference Gassendi1727, VI, p. 41), is probably an early modern re-coinage; it is unattested in Classical Latin. Adams (Reference Adams2019) suggests that it means ‘little outbursts of anger’. Secundus himself may have been confused by the syntax, since he first wrote meretur (singular) as if iracundiolae were genitive singular like corporis, before realising that he intended a plural subject with merentur.

1–2, castigationem. o is only a flick of the pen, little more than an interpunct in appearance.

2, a senioribus. Although senior and iunior are occasionally found in military documents to distinguish homonyms (Tab. Luguval. 16.9, with note), there is no instance of seniores used collectively as ‘senior officers’, whereas it is often used in Classical and later Latin in the sense of ‘elders’. It might therefore be intended to have general application, but in this military context it is tempting to understand it as referring to higher-ranking officers.

3. de qua re is extended left in ekthesis, to mark a new sentence.

4. praesens is echoed by in praesentia, but in praesentia has to be treated as introducing a new sentence (Adams Reference Adams2019).

5, omn[es] decuriones huius numeri. As noted above, the ‘unit’ was probably a cavalry ala. We may guess that its officers were affronted by something which Decuminus, a centurion of infantry in another unit, had said or done, or left undone. There is no knowing what this was, but Secundus was evidently trying to put things right, and also (probably) to get Decuminus into trouble with his commanding officer.

6. The break has removed all of this line except for the tips of the first c. 5 letters. The first is c or s, with c more likely (compare the initial c of Caecilius (i.1) and corporis (ii.1)); and there is a similar stroke further to the right. These traces are consistent with conco[rditer] (‘in agreement’), but they are too slight for this to be more than a possibility.

Back

Only the first line of the address is preserved, written in elongated ‘address script’ except for the last two letters, which may have been reduced to ordinary cursive because space was running out. On the lower half of the leaf, now lost, Verecundus was probably identified as praefecto (dative); and the sender's name would have followed (ab Caecilio Secundo), probably followed by his rank or position.

DESCRIPTUM

Inv. no. WT2017.18 add. Dimensions 92 × 18 mm. Period I. Location: V17-52B, above Period I extramural road (fig. 10).

FIG. 10. Descriptum, both faces. 92 × 18 mm. (Above) ‘Front’; (below) ‘Back’.

This fragment was found with 893 and shares the same inventory number, but it does not conjoin. Since both side edges are original, its width (92 mm) is certain; but this is 4 mm less than the width of either leaf of 893, so it must be part of another tablet. We have distinguished it by adding ‘add(endum)’ to the inventory number, and treat it as a Descriptum to be given a final number only in the full publication of the new tablets.

Written on both faces, which for convenience have been called ‘Front’ and ‘Back’, without it being evident which text was secondary to the other, nor indeed whether they were even related.

The top edge of both faces looks original, in view of the space between it and the only line of text on the ‘Back’. The bottom edge is certainly broken.

Front:

Iulio Verecunḍ[o]

miḥi karisṣịṃọ

. . . . . . . . . . .

‘To Iulius Verecundus, dearest to me …’

Back:

]decmó (centurioni/e) coh(ortis) I Tung(rorum)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

‘[…] Decmus, centurion of the First Cohort of Tungrians …’

Front

The letters after karis are illegible, but they must surely have completed karissimo. Such an endearment is no part of an address on the back of a diptych, but would suggest an informal letter-heading (the text below now lost) from which the writer has omitted his name. This is hard to parallel, but perhaps it headed a brief ‘note’ which Verecundus was expecting, or one written by an intimate.

Back

There is an apex over the o of ]decmo. The numeral is barred and the unit title abbreviated. It looks as if there was nothing written to the left of ]decmo, which would then be dative (‘to Decmus’), but the break does not quite exclude the possibility of a short preposition such as ab (‘from’) or de (‘concerning’). It is written in ordinary cursive, not the elongated letters of ‘address script’, but may be the first line of an address which has lost the sender's name. However, the ‘Front’ is certainly not part of a letter written to ‘Decmus’.

Decmus is found as a name, but is uncommon. Decimus is quite common, so the omission of i may be only a slip of the pen or even represent a variant spelling: compare RIB I, 240, the tombstone of Decmus Malus[…] who is taken to be Dec(i)mus Malus[ius]. Another possibility which must be considered is that it is an abbreviation of Dec(u)m(in)o, since this scrap was found with 893 which concerns the centurion Decuminus, a subordinate of the prefect Verecundus and thus a centurion of the First Cohort of Tungrians. But despite this coincidence, abbreviation by contraction, not suspension, is most uncommon.

We cannot explain this enigmatic fragment. It would only be a guess to relate it to 893 by suggesting that it was part of an informal note to Verecundus in response to his inquiry about Decuminus, which he or his secretary then marked as ‘concerning Decuminus’.

V. INDEXES

These indexes follow the form and numbering of those attached to Tab. Vindol. IV.2 (Britannia 42 (2011), 141–4), except that there is no ‘Index I: Calendar'. They comprise the four tablets published here (891–93) and the Descriptum to which no number has yet been allotted (Descr.). A line number in square brackets indicates that the word is wholly supplied. Entries of the type ‘890.4n’ mean that the word in question is suggested in the relevant note.

Index II: Personal Names

Andangius 891.1

Audax, seruus 890.i.1, back

Augustanus 892.6

Bellicus 892.7

Caecilius: see Secundus

Crispus, mensor 891.8

Cusius 892.7

Decmus, centurion Descr. back

Decuminus, centurion 893.i.3

Iulius: see Verecundus

Lituccus 892.5

Masclus, decurio 892.1, back.3

Nobilis, centurion 892.10

Peregrinus, decurion: see Index IV s.v. turma

Secundus, Caecilius 893.i.1

Talio 892.13

Talampus 892.10

Vel[ 891.1

Verecundus, Iulius, praefectus 890.i.1, 890, back.1-2, 891.3, 892.1, back, 893.i.1, back, Descr. front

Victor 892.5

Vitalis 892.5 [deleted]

Index III: Geography

R(a)eti 892.2 (Reti), 4 (Retorum)

Tungri: see Index IV s.v. cohors

Vocontii 892.i.6

Index IV: Military and official terms

centuria 892.10

centurio 893.i.3, Descr. back

cohors i Tungrorum Descr. back

decurio 892.back.3, 893.ii.5

numerus 893.ii.5

praefectus 892.back.2 (prefectus)

turma Peregriniana 892.13

Index V: Abbreviations and symbols

coh: cohors Descr. back

dec: decurio 892.back.3

sal: salutem 892.1

tur: turma 892.13

(centuria) 892.10

(centurio) 893.i.3, Descr. back

Index VI: General index of Latin words

a, ab, abs 890.ii.1, 892.2, 3, back.3, 893 ii.2

ad 890.i.5

adfero 890.ii.2

ago

agam 893.ii.4

agere 891.11

alius 890.ii.5

amicus 891.[7]

beneficium 891.9

caballus 890.i.6

carus

karissimo Descr. front

castigatio 893.ii.1

centuria, centurio: see Indexes IV and V

cista 890.ii.6

ciuis 891.6, 892.2

clauis 890.ii.4

commiatus 892.3 (commeatus)

commodus

commodius 893.ii.3

corpus 893.ii.1

culter 892.9

cum 890.ii.5

-cum: tecum, see tu

cumprimum 890.i.3

cura 892.4

cyma 890.ii.3

de 892.6, 893.ii.3

debeo 890.ii.6, 891.12

decurio: see Index IV

dico

dicitur 890.ii.7

dignus 891.5

dimitto

dimisi 890.i.6

dominus 891.2, 892.8

duo 890.i.6

eaque 890.ii.4

ego

me 892.2

mihi 893.i.3, Descr. front

nobis 892.11

nos 891.5

enim 890.ii.7

et 890.ii.3 bis, 891.[5], [6], 11, 892.5, 6, 8, 14

facio

facias 891.9

fieri 890.i.3

felix 892.14

ferme 890.i.4n

genius 891.11

gratia 891.11

habeo 891.5

hic

haec 890.ii.6

hanc 890.i.4n

hoc 890.ii.2

huius 893.ii.5

hodie 890.i.5

holoracius 890.ii.3

horriolum 890.ii.7 (horreolum)

in 890.ii.1, 893.ii.4

iracundiola 893.ii.1

is

id 893.i.4

iubeo 892.8

iustitia 891.4

laedo

laedatur 890.ii.1

leuis

leuius 891.10

mane 890.4n

mensor 891.8

mereor

merentur 893.ii.2

milito

militare 891.10

mitto

misisti 890.ii.5

missi 892.12

mitte 890.i.4, ii.4

napicius 890.ii.3

necessarius 892.11

nomen 891.7

nos: see ego

noster 891.7

notus

notissimus 891.3

numerus 893.ii.5

omnis 893.ii.5

opto 892.14

ostendo 893.i.4

pars 890.i.3

penis 892.10 (penes)

per 891.3, 892.13

peto

peterem 892.3

petierunt 892.2

planta 892.12

possum

possit 891.9

potuerit 890.i.3

praesens 893.ii.4

praesentia 893.ii.4

praesto 891.6

prefectus: see Index IV (praefectus)

primum: see cumprimum

quam (conj.) 890.ii.6

-que: see ea

qui 892.4, 9

qua 890.ii.1, 893.ii.3

quae 893.ii.1

quam 890.5

quas 893.i.3

quia 892.11

quinque 892.3

quoque 890.ii.5

reddo

reddi 892.8

res 893.ii.3

rogo 892.8

rogamus 891.2

salus

sal(utem) 892.1

salutem 890.i.2, 893.ii.2

scio

sciret 893.i.4

scito 893.ii.5

scissorius 892.9

scribo

scripseras 893.i.3

se 893.i.4

sed 893.ii.1

senior 893.ii.2

seruus 890.back.2

solutus 890.i.6

sub 892.4

sum

est 890.ii.2, 892.11, 893.ii.3

sunt 892.5

suus 892.1, 893.i.2

tilia 893.i.3

tres

trium 892.3 [deleted]

tu

te 891.2, 892.3, 14

tecum 893.ii.3

tibi 892.12

uos 890.i.5

turma 892.13

tuus 891.4, 10, 15, 892.4, 14

ualeo

uale 892.15

uelatura 890.ii.1

uetura 890.i.3 (uectura)

uiridia 890.ii.2

uos: see tu

ut 891.6, 9, 892.2, 8, 893.i.[4], ii.3