1. Introduction

The investigation of microchannel flows has attracted significant interest owing to their broad applications in microfluidic devices, lab-on-a-chip devices, microfluidic cooling systems, heat exchangers, microfluidic-based drug delivery systems, DNA sequencing and single-molecule detection. The use of slip microchannel flows in these applications highlights their importance in advancing innovation and improving performance across various micro- and nanofluidic technologies (Madou et al. Reference Madou, Zoval, Jia, Kido, Kim and Kim2006). Rotating micro-ducts with superhydrophobic walls have recently gained much attention because of their growing use in microfluidic devices (Chakraborty, Madou & Chakborty Reference Chakraborty, Madou and Chakborty2011), microreactor systems and point-of-care diagnostics (Hugo et al. Reference Hugo, Land, Madou and Kido2014). In such devices, rotation is often used to improve fluid mixing (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Lee, Lee, Prakash, Kim, Cho and Lee2022), particle movement and chemical reactions. Superhydrophobic surfaces (Amjad et al. Reference Amjad, Nguir, Ma and Wen2025) are commonly chosen as they reduce wall friction, resist chemical reactions and prevent fouling. The combined effect of wall slip and rotation (Chikkam & Kumar Reference Chikkam and Kumar2019) produces complex flow behaviour, which can greatly affect the onset of flow instability and transition. In these confined microchannel flows, the aspect ratio (ratio of channel height to width) also plays an important role in controlling the flow pattern and its stability. Therefore, it is essential to study the combined influence of aspect ratio, slip and rotation to achieve better design and stable performance in microfluidic systems and superhydrophobic devices (Sajjan & Raju Reference Sajjan and Raju2024). Since flow stability governs the onset of transition and mixing in such systems, a linear stability analysis provides a fundamental framework for predicting the early stages of flow disturbances and understanding their physical mechanisms.

Aspect ratio is a fundamental parameter that shapes the flow pattern in microchannels. It influences the velocity profile (Zheng & Silber-Li Reference Zheng and Silber-Li2008; Elsnab et al. Reference Elsnab, Maynes, Klewicki and Ameel2010; Prohm & Stark Reference Prohm and Stark2014), shear stress distribution and flow instabilities ( Norouzi & Biglari Reference Norouzi and Biglari2013; Jouin, Robinet & Cherubini Reference Jouin, Robinet and Cherubini2024) that may develop. The aspect ratio (

![]() $\delta$

) is a key geometrical parameter in the design and analysis of liquid mixing in the microchannels. Microchannels are often classified as narrow or wide based on their aspect ratio, which is defined as the ratio of height to width. In the limit of a large aspect ratio, the flow approaches plane Poiseuille flow, which becomes unstable at a critical Reynolds number of

$\delta$

) is a key geometrical parameter in the design and analysis of liquid mixing in the microchannels. Microchannels are often classified as narrow or wide based on their aspect ratio, which is defined as the ratio of height to width. In the limit of a large aspect ratio, the flow approaches plane Poiseuille flow, which becomes unstable at a critical Reynolds number of

![]() $ Re_c \approx 3848$

(based on the centreline velocity, which is

$ Re_c \approx 3848$

(based on the centreline velocity, which is

![]() $1.5$

times the bulk velocity), as reported by Orszag (Reference Orszag1970). The first direct observation of flow instability was conducted by Kao & Park (Reference Kao and Park1970) using advanced experimental techniques, revealing a critical Reynolds number of approximately

$1.5$

times the bulk velocity), as reported by Orszag (Reference Orszag1970). The first direct observation of flow instability was conducted by Kao & Park (Reference Kao and Park1970) using advanced experimental techniques, revealing a critical Reynolds number of approximately

![]() $2600$

when

$2600$

when

![]() $\delta =8$

, which is significantly lower than the theoretical predictions. Tatsumi & Yoshimura (Reference Tatsumi and Yoshimura1990) depicted that duct flow becomes unstable for

$\delta =8$

, which is significantly lower than the theoretical predictions. Tatsumi & Yoshimura (Reference Tatsumi and Yoshimura1990) depicted that duct flow becomes unstable for

![]() $ \delta \gt 3.2$

, while it remains stable for

$ \delta \gt 3.2$

, while it remains stable for

![]() $ \delta \lt 3.2$

, indicating a critical aspect ratio. Their results show convergence to a plane Poiseuille instability as

$ \delta \lt 3.2$

, indicating a critical aspect ratio. Their results show convergence to a plane Poiseuille instability as

![]() $ \delta \to \infty$

. Similarly, Adachi (Reference Adachi2013) reported a critical aspect ratio of

$ \delta \to \infty$

. Similarly, Adachi (Reference Adachi2013) reported a critical aspect ratio of

![]() $ \delta = 3.19$

for rectangular ducts using bifurcation analysis. The influence of aspect ratio on the development of secondary currents in an open channel flow was also examined by Shinneeb, Nasif & Balachandar (Reference Shinneeb, Nasif and Balachandar2021), highlighting its significance in flow structure evolution. Variations in aspect ratio can alter shear distribution, boundary layer development and secondary flow patterns, all of which are critical in determining the onset and nature of flow instabilities. However, the aspect ratio in conjunction with rotation and slip effects, in the context of stability analysis, has not been examined so far.

$ \delta = 3.19$

for rectangular ducts using bifurcation analysis. The influence of aspect ratio on the development of secondary currents in an open channel flow was also examined by Shinneeb, Nasif & Balachandar (Reference Shinneeb, Nasif and Balachandar2021), highlighting its significance in flow structure evolution. Variations in aspect ratio can alter shear distribution, boundary layer development and secondary flow patterns, all of which are critical in determining the onset and nature of flow instabilities. However, the aspect ratio in conjunction with rotation and slip effects, in the context of stability analysis, has not been examined so far.

Superhydrophobic coatings are a promising way to reduce drag in applications where liquids flow over solid surfaces, spanning a broad range of Reynolds numbers from laminar to turbulent flows. In microreactors, superhydrophobic surfaces are commonly used not only because they reduce friction but also due to their strong chemical resistance. When such systems are rotated, the mixing can improve considerably, which in turn influences the residence time distribution and the consistency of the final product. Although the utilisation of microfabrication techniques employing polymeric or silicon-based materials has yielded profound insights into fluid behaviour at small scales (Ho & Tai Reference Ho and Tai1998; Stone, Stroock & Ajdari Reference Stone, Stroock and Ajdari2004), a notable phenomenon on superhydrophobic surfaces is the occurrence of velocity slip, where air trapped in micro-and nanostructures induces slip at the liquid–air interfaces for which the slip boundary condition should be adopted in modelling the problem (Choi & Kim Reference Choi and Kim2006; Lee & Kim Reference Lee and Kim2011). This slip behaviour is quantified by the effective slip length parameter, which, despite being typically minute on conventional surfaces, has been experimentally observed to reach dimensions on the order of hundreds of microns. Accurate quantification of interfacial slip was investigated by Vega-Sánchez & Neto (Reference Vega-Sánchez and Neto2022) using the pressure drop versus flow rate method. Extensive numerical and theoretical investigations have been undertaken to model velocity slip on superhydrophobic surfaces and to discern its implications for fluid transport across laminar and fully turbulent flows (Vinogradova Reference Vinogradova1999; Lauga & Stone Reference Lauga and Stone2003; Bazant & Vinogradova Reference Bazant and Vinogradova2008; Lee, Choi & Kim Reference Lee, Choi and Kim2008; Park, Park & Kim Reference Park, Park and Kim2013; Rowin & Ghaemi Reference Rowin and Ghaemi2019).

In linear stability analysis a commonly used approach is the Navier slip boundary condition, which is applied in various channel flow problems (Lauga & Cossu Reference Lauga and Cossu2005; Min & Kim Reference Min and Kim2005; Ghosh, Usha & Sahu Reference Ghosh, Usha and Sahu2014; Seo & Mani Reference Seo and Mani2016; Chai & Song Reference Chai and Song2019; Ceccacci et al. Reference Ceccacci, Calabretto, Thomas and Denier2022). Typically, slip length is considered to be uniform and isotropic, which does not vary with position or direction on the wall. Several studies have found that velocity slip stabilises the flow, thereby significantly increasing the critical Reynolds number (Lauga & Cossu Reference Lauga and Cossu2005; Min & Kim Reference Min and Kim2005; Ghosh et al. Reference Ghosh, Usha and Sahu2014). However, recent studies suggest that velocity slip can also destabilise the flow in the case of an anisotropic slip (Pralits, Alinovi & Bottaro Reference Pralits, Alinovi and Bottaro2017; Chai & Song Reference Chai and Song2019; Xiong & Tao Reference Xiong and Tao2020; Chen & Song Reference Chen and Song2021; Zhai, Chen & Song Reference Zhai, Chen and Song2023; Sengupta & Chakraborty Reference Sengupta and Chakraborty2024). Specifically, Chai & Song (Reference Chai and Song2019) revisited previous studies by Lauga & Cossu (Reference Lauga and Cossu2005) and Min & Kim (Reference Min and Kim2005), examining channel flow stability with separate streamwise and spanwise slip velocities. They demonstrated through modal and non-modal analysis that a large slip in either direction triggers three-dimensional instabilities.

Rotation of a system of fluid flow, having applications in centrifugal microfluidic devices, can enhance the instability (Alfredsson & Persson Reference Alfredsson and Persson1989; Matsson & Alfredsson Reference Matsson and Alfredsson1990; Wallin, Grundestam & Johansson Reference Wallin, Grundestam and Johansson2013; Sengupta et al. Reference Sengupta, Ghosh, Saha and Chakraborty2019a

,

Reference Sengupta, Ghosh, Saha and Chakrabortyb

, Reference Sengupta, Ghosh and Chakraborty2020). They reported that the critical Reynolds number decreased to below

![]() $100$

due to the consideration of a spanwise rotation system. Whereas Bera et al. (Reference Bera, Shit, Reza and Drese2024) illustrated the critical Reynolds number to be

$100$

due to the consideration of a spanwise rotation system. Whereas Bera et al. (Reference Bera, Shit, Reza and Drese2024) illustrated the critical Reynolds number to be

![]() $44$

at

$44$

at

![]() $Ro=0.26$

using rotating curved microchannel flows. In such systems, rotation-induced Coriolis and centrifugal forces play a pivotal role in controlling mixing, stability and transport phenomena at the microscale. Non-modal stability analyses have been carried out by Reddy & Henningson (Reference Reddy and Henningson1993), Schmid (Reference Schmid2000), Satish & Alison (Reference Satish and Alison2005), Pralits, Alinovi & Bottaro (Reference Pralits, Alinovi and Bottaro2017), Schmid, De Pando & Peake (Reference Schmid, De Pando and Peake2017), Chai & Song (Reference Chai and Song2019) and Jouin et al. (Reference Jouin, Robinet and Cherubini2024) using eigenvalues and eigenvectors to illustrate the short-term behaviour of the disturbance in terms of the transient energy growth function. These analyses give deeper insight into the disturbance, as it cannot identify any unstable modes through modal analysis.

$Ro=0.26$

using rotating curved microchannel flows. In such systems, rotation-induced Coriolis and centrifugal forces play a pivotal role in controlling mixing, stability and transport phenomena at the microscale. Non-modal stability analyses have been carried out by Reddy & Henningson (Reference Reddy and Henningson1993), Schmid (Reference Schmid2000), Satish & Alison (Reference Satish and Alison2005), Pralits, Alinovi & Bottaro (Reference Pralits, Alinovi and Bottaro2017), Schmid, De Pando & Peake (Reference Schmid, De Pando and Peake2017), Chai & Song (Reference Chai and Song2019) and Jouin et al. (Reference Jouin, Robinet and Cherubini2024) using eigenvalues and eigenvectors to illustrate the short-term behaviour of the disturbance in terms of the transient energy growth function. These analyses give deeper insight into the disturbance, as it cannot identify any unstable modes through modal analysis.

Rotating microchannel flows can lead to linear instability even at low Reynolds numbers due to the interplay between Coriolis and inertial forces. This raises an important question: Can rotation induce instability in channels with low aspect ratios (

![]() $ \delta \lt 3.19$

), which are typically stable in the non-rotating case? Additionally, anisotropy in slip lengths where streamwise and spanwise slip differ may further influence these instabilities, potentially lowering the critical Reynolds number compared with uniformly rotating microchannels. The above-mentioned literature survey reveals a gap in the study of rotating microchannel flows, specifically in considering both the aspect ratio and wall slip simultaneously. Most earlier works focused on non-rotating flows or high-aspect-ratio channels, without considering slip effects. In this study we address this issue by analysing microchannel flows and examining how both low and high aspect ratios, as well as wall slip, affect flow stability under rotation. We employ both modal and non-modal linear stability methods. Modal analysis examines eigenvalues to determine when instability begins, while non-modal analysis investigates how disturbance energy evolves over a short time. Previous investigators mostly studied these effects separately. Following earlier works like Min & Kim (Reference Min and Kim2005), Chai & Song (Reference Chai and Song2019) and Chen & Song (Reference Chen and Song2021), we consider streamwise and spanwise slip as limiting cases of anisotropic slip, which was not considered by Sengupta & Chakraborty (Reference Sengupta and Chakraborty2024) in their recent work. To our knowledge, this is the first combined study of wall slip and aspect ratio effects on the stability of a rotating microchannel flow, and we report lower critical Reynolds numbers than those previously reported.

$ \delta \lt 3.19$

), which are typically stable in the non-rotating case? Additionally, anisotropy in slip lengths where streamwise and spanwise slip differ may further influence these instabilities, potentially lowering the critical Reynolds number compared with uniformly rotating microchannels. The above-mentioned literature survey reveals a gap in the study of rotating microchannel flows, specifically in considering both the aspect ratio and wall slip simultaneously. Most earlier works focused on non-rotating flows or high-aspect-ratio channels, without considering slip effects. In this study we address this issue by analysing microchannel flows and examining how both low and high aspect ratios, as well as wall slip, affect flow stability under rotation. We employ both modal and non-modal linear stability methods. Modal analysis examines eigenvalues to determine when instability begins, while non-modal analysis investigates how disturbance energy evolves over a short time. Previous investigators mostly studied these effects separately. Following earlier works like Min & Kim (Reference Min and Kim2005), Chai & Song (Reference Chai and Song2019) and Chen & Song (Reference Chen and Song2021), we consider streamwise and spanwise slip as limiting cases of anisotropic slip, which was not considered by Sengupta & Chakraborty (Reference Sengupta and Chakraborty2024) in their recent work. To our knowledge, this is the first combined study of wall slip and aspect ratio effects on the stability of a rotating microchannel flow, and we report lower critical Reynolds numbers than those previously reported.

2. Flow configuration and mathematical framework

We examine the stability analysis of an incompressible and rotating slip microchannel laminar flow subject to spanwise rotation. We assume that the microchannel has a half-width and half-height denoted by

![]() $d$

and

$d$

and

![]() $h$

, respectively. We use a Cartesian coordinate system

$h$

, respectively. We use a Cartesian coordinate system

![]() $(x^*, y^*, z^*)$

, where the

$(x^*, y^*, z^*)$

, where the

![]() $x^*$

axis corresponds to the streamwise direction and the

$x^*$

axis corresponds to the streamwise direction and the

![]() $y^*$

axis corresponds to the wall-normal direction. The entire system rotates about the spanwise

$y^*$

axis corresponds to the wall-normal direction. The entire system rotates about the spanwise

![]() $z^*$

direction, with a rotational velocity

$z^*$

direction, with a rotational velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{\varOmega ^*} = (0, 0, \varOmega ^*)$

. The rotation of the microchannel system introduces the Coriolis force, represented as

$\boldsymbol{\varOmega ^*} = (0, 0, \varOmega ^*)$

. The rotation of the microchannel system introduces the Coriolis force, represented as

![]() $-2\varOmega ^* \times \mathfrak{u}^*$

, which acts as a body force. Meanwhile, the centrifugal force

$-2\varOmega ^* \times \mathfrak{u}^*$

, which acts as a body force. Meanwhile, the centrifugal force

![]() $-\varOmega ^* \times (\varOmega ^* \times r^*)$

, where

$-\varOmega ^* \times (\varOmega ^* \times r^*)$

, where

![]() $r^*$

is the position vector from the axis of rotation, is considered as a modified pressure

$r^*$

is the position vector from the axis of rotation, is considered as a modified pressure

![]() $p_m^*$

. The physical configuration of the problem is illustrated in figure 1. According to the above-mentioned assumptions, the Navier–Stokes equations system for an incompressible flow in the dimensional form is taken as

$p_m^*$

. The physical configuration of the problem is illustrated in figure 1. According to the above-mentioned assumptions, the Navier–Stokes equations system for an incompressible flow in the dimensional form is taken as

Figure 1. Schematic diagram depicting a rotating slip microchannel flow (slip length is not possible to show due to the three-dimensional view) with a width of

![]() $2d$

and a height of

$2d$

and a height of

![]() $2h$

in figure 1(a). The mean flow is directed along the

$2h$

in figure 1(a). The mean flow is directed along the

![]() $x^*$

axis, while the entire system rotates about the

$x^*$

axis, while the entire system rotates about the

![]() $z^*$

axis. Slip lengths along both the flow (streamwise) and across the flow (spanwise and wall-normal) directions are considered due to superhydrophobicity walls, but only the streamwise slip length (

$z^*$

axis. Slip lengths along both the flow (streamwise) and across the flow (spanwise and wall-normal) directions are considered due to superhydrophobicity walls, but only the streamwise slip length (

![]() $l_{x^*}$

) is shown as it can be clearly represented in the cross-sectional view (figure 1

b,c). Figure 1(b) displays the cross-section along

$l_{x^*}$

) is shown as it can be clearly represented in the cross-sectional view (figure 1

b,c). Figure 1(b) displays the cross-section along

![]() $y^*$

at

$y^*$

at

![]() $z^* = 0$

, showing the dimensional base-state velocity

$z^* = 0$

, showing the dimensional base-state velocity

![]() $U_1^*(y^*)$

, while figure 1(c) presents the cross-section along

$U_1^*(y^*)$

, while figure 1(c) presents the cross-section along

![]() $z^*$

at

$z^*$

at

![]() $y^* = 0$

, showing the dimensional base-state velocity

$y^* = 0$

, showing the dimensional base-state velocity

![]() $U_2^*(z^*)$

.

$U_2^*(z^*)$

.

where

![]() $\mathfrak{u}^*=(u^*,v^*,w^*)$

denotes the velocity vector and

$\mathfrak{u}^*=(u^*,v^*,w^*)$

denotes the velocity vector and

![]() $p_m^{*}=p^*-{\varOmega ^*}^2(x^{*^2}+y^{*^2})$

the modified pressure.

$p_m^{*}=p^*-{\varOmega ^*}^2(x^{*^2}+y^{*^2})$

the modified pressure.

In the presence of hydrophobic walls, we employ the following Navier slip boundary conditions for velocity components:

\begin{align}& u^*\pm l_{x^*}\frac {\partial u^*}{\partial y^*}=0,\qquad w^*\pm l_{z^*}\frac {\partial w^*}{\partial y^*}=0\quad \mbox{and}\quad v^*=0 \hspace {0.5cm} \mbox{at} \,\, y^*=\pm d,\nonumber \\& u^*\pm l_{x^*}\frac {\partial u^*}{\partial z^*}=0,\qquad v^*\pm l_{y^*}\frac {\partial v^*}{\partial z^*}=0\quad\mbox{and}\quad w^*=0 \hspace {0.5cm} \mbox{at}\,\, z^*=\pm h. \end{align}

\begin{align}& u^*\pm l_{x^*}\frac {\partial u^*}{\partial y^*}=0,\qquad w^*\pm l_{z^*}\frac {\partial w^*}{\partial y^*}=0\quad \mbox{and}\quad v^*=0 \hspace {0.5cm} \mbox{at} \,\, y^*=\pm d,\nonumber \\& u^*\pm l_{x^*}\frac {\partial u^*}{\partial z^*}=0,\qquad v^*\pm l_{y^*}\frac {\partial v^*}{\partial z^*}=0\quad\mbox{and}\quad w^*=0 \hspace {0.5cm} \mbox{at}\,\, z^*=\pm h. \end{align}

Here

![]() $l_{x^*}$

,

$l_{x^*}$

,

![]() $l_{y^*}$

and

$l_{y^*}$

and

![]() $l_{z^*}$

are the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise slip lengths, and they are independent of each other. Here, we consider the symmetric slip lengths, which are the same on all the walls.

$l_{z^*}$

are the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise slip lengths, and they are independent of each other. Here, we consider the symmetric slip lengths, which are the same on all the walls.

2.1. Base flow characteristics

Owing to the above-mentioned flow configuration, we decompose the velocity and pressure into steady and unsteady disturbances of a fully developed base flow as

where the variables with

![]() $(^*)$

define the dimensional perturbed quantities in which

$(^*)$

define the dimensional perturbed quantities in which

![]() $\tilde {\mathfrak{u}}^*(\tilde {u}^*,\tilde {v}^*,\tilde {w}^*)$

and

$\tilde {\mathfrak{u}}^*(\tilde {u}^*,\tilde {v}^*,\tilde {w}^*)$

and

![]() $\tilde {p}^*$

are very small. We express the governing equations in non-dimensional form using the scaling variables

$\tilde {p}^*$

are very small. We express the governing equations in non-dimensional form using the scaling variables

\begin{align} &\mathfrak{u}=\frac {\tilde {\mathfrak{u}}^*}{U_b},\quad U=\frac {U^*}{U_b},\quad l_x=\frac {l_{x^*}}{D_H},\quad l_{\!y}=\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\frac {l_{y^*}}{D_H},\quad l_z=\frac {2}{1+\delta }\frac {l_{z^*}}{D_H},\quad \delta =\frac {h}{d}, \hspace {0cm}\nonumber \\& x=\frac {x^*}{D_H}, \quad y=\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\frac {y^*}{D_H}, \quad z=\frac {2}{1+\delta }\frac {z^*}{D_H}, \quad t=\frac {t^*}{T}, \quad p=\frac {\tilde {p}^*}{\rho U_b^2},\end{align}

\begin{align} &\mathfrak{u}=\frac {\tilde {\mathfrak{u}}^*}{U_b},\quad U=\frac {U^*}{U_b},\quad l_x=\frac {l_{x^*}}{D_H},\quad l_{\!y}=\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\frac {l_{y^*}}{D_H},\quad l_z=\frac {2}{1+\delta }\frac {l_{z^*}}{D_H},\quad \delta =\frac {h}{d}, \hspace {0cm}\nonumber \\& x=\frac {x^*}{D_H}, \quad y=\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\frac {y^*}{D_H}, \quad z=\frac {2}{1+\delta }\frac {z^*}{D_H}, \quad t=\frac {t^*}{T}, \quad p=\frac {\tilde {p}^*}{\rho U_b^2},\end{align}

where

![]() $\delta$

is the aspect ratio of the rectangular channel and

$\delta$

is the aspect ratio of the rectangular channel and

![]() $D_H= 2hd/({h+d} )$

is the hydraulic diameter of the channel,

$D_H= 2hd/({h+d} )$

is the hydraulic diameter of the channel,

![]() $l_x$

,

$l_x$

,

![]() $l_{\!y}$

and

$l_{\!y}$

and

![]() $l_z$

represent the dimensionless slip lengths (Knudsen number) in the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions, respectively;

$l_z$

represent the dimensionless slip lengths (Knudsen number) in the streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise directions, respectively;

![]() $T$

is the real mixing time and

$T$

is the real mixing time and

![]() $U_b$

denotes the bulk (or mean) velocity. It is important to note that the base-state velocity is influenced only by the streamwise slip

$U_b$

denotes the bulk (or mean) velocity. It is important to note that the base-state velocity is influenced only by the streamwise slip

![]() $l_x$

(Chai & Song Reference Chai and Song2019; Chen & Song Reference Chen and Song2021).

$l_x$

(Chai & Song Reference Chai and Song2019; Chen & Song Reference Chen and Song2021).

By considering

![]() $\mathfrak{u}^*=(U^*(y^*,z^*),0,0)$

, which satisfies the continuity equation (2.1) automatically and then applying the dimensionless quantities defined in (2.5) into the momentum (2.2), the governing equation for base flow for an incompressible and steady flow reads

$\mathfrak{u}^*=(U^*(y^*,z^*),0,0)$

, which satisfies the continuity equation (2.1) automatically and then applying the dimensionless quantities defined in (2.5) into the momentum (2.2), the governing equation for base flow for an incompressible and steady flow reads

which is then transformed to

The boundary conditions (see (2.3)) for the base flow become

\begin{align}& U+l_x\frac {\partial U}{\partial y}=0\quad\mbox{at}\ y= 1;\qquad U-l_x\frac {\partial U}{\partial y}=0 \hspace {0.5cm} \mbox{at}\,\, y=-1,\nonumber \\& U+l_x \frac {\partial U}{\partial z}=0\quad \mbox{at}\ z= 1;\qquad U-l_x\frac {\partial U}{\partial z}=0 \hspace {0.5cm} \mbox{at}\,\, z=-1, \end{align}

\begin{align}& U+l_x\frac {\partial U}{\partial y}=0\quad\mbox{at}\ y= 1;\qquad U-l_x\frac {\partial U}{\partial y}=0 \hspace {0.5cm} \mbox{at}\,\, y=-1,\nonumber \\& U+l_x \frac {\partial U}{\partial z}=0\quad \mbox{at}\ z= 1;\qquad U-l_x\frac {\partial U}{\partial z}=0 \hspace {0.5cm} \mbox{at}\,\, z=-1, \end{align}

where the Reynolds number is defined as

![]() ${\textit{Re}}=(U_bD_H)/{\nu }$

. In order to solve (2.7) subject to the boundary condition (2.8), we use the Chebyshev differentiation matrix (Trefethen Reference Trefethen2000) along with the tensor product from linear algebra, the left-hand side of (2.7) follows

${\textit{Re}}=(U_bD_H)/{\nu }$

. In order to solve (2.7) subject to the boundary condition (2.8), we use the Chebyshev differentiation matrix (Trefethen Reference Trefethen2000) along with the tensor product from linear algebra, the left-hand side of (2.7) follows

where

![]() $\mathcal{D}^2$

represents the second-order Chebyshev differentiation matrix. Using the matrix inversion method, we solve (2.7) and extract a cross-sectional profile along the line

$\mathcal{D}^2$

represents the second-order Chebyshev differentiation matrix. Using the matrix inversion method, we solve (2.7) and extract a cross-sectional profile along the line

![]() $z=0$

, which varies with the wall-normal direction

$z=0$

, which varies with the wall-normal direction

![]() $y$

as well as along the line

$y$

as well as along the line

![]() $y=0$

, which varies along the direction

$y=0$

, which varies along the direction

![]() $z$

. We reduce the resulting steady base flow in dimensionless form using the mean velocity and use the same length scales of

$z$

. We reduce the resulting steady base flow in dimensionless form using the mean velocity and use the same length scales of

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

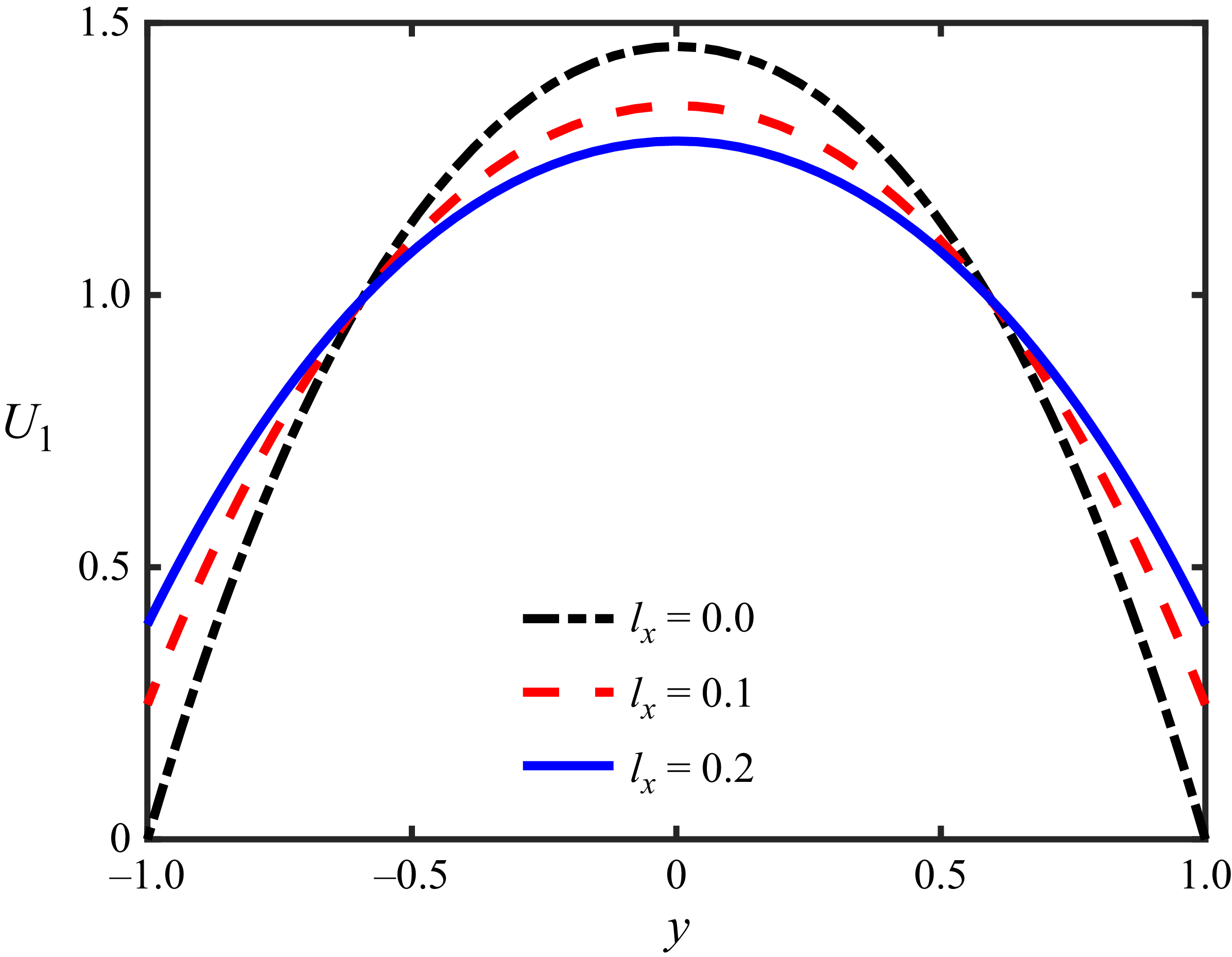

as depicted in figure 2(a) depending on

$z$

as depicted in figure 2(a) depending on

![]() $y$

, and in figure 2(b) depending on

$y$

, and in figure 2(b) depending on

![]() $z$

with a varying aspect ratio (

$z$

with a varying aspect ratio (

![]() $\delta$

). To make the scales comparable for plotting

$\delta$

). To make the scales comparable for plotting

![]() $U_1$

and

$U_1$

and

![]() $U_2$

, we normalise the length scales to

$U_2$

, we normalise the length scales to

![]() $[-1,1]$

. As a result of this rescaling, the maximum values of

$[-1,1]$

. As a result of this rescaling, the maximum values of

![]() $U_1$

and

$U_1$

and

![]() $U_2$

appear different even for the same aspect ratio. This difference arises solely from the normalisation of the axes for comparison and does not affect the physical behaviour of the base flow. Since the base flow is non-dimensionalised using the mean velocity, the maximum velocity becomes

$U_2$

appear different even for the same aspect ratio. This difference arises solely from the normalisation of the axes for comparison and does not affect the physical behaviour of the base flow. Since the base flow is non-dimensionalised using the mean velocity, the maximum velocity becomes

![]() $\approx 1.5$

. From both the figures, we state that the aspect ratio (

$\approx 1.5$

. From both the figures, we state that the aspect ratio (

![]() $\delta = h/d$

) plays a crucial role in shaping the base flow velocity profiles

$\delta = h/d$

) plays a crucial role in shaping the base flow velocity profiles

![]() $U_1(y)$

and

$U_1(y)$

and

![]() $U_2(z)$

for fully developed laminar flow in a channel and thereby impacts the stability of the flow. At low aspect ratios (

$U_2(z)$

for fully developed laminar flow in a channel and thereby impacts the stability of the flow. At low aspect ratios (

![]() $\delta \lt 1$

), the channel is wide and shallow. In this case, the velocity profile becomes flattened along

$\delta \lt 1$

), the channel is wide and shallow. In this case, the velocity profile becomes flattened along

![]() $y$

due to the weaker influence of the vertical boundaries, while along

$y$

due to the weaker influence of the vertical boundaries, while along

![]() $z$

, the velocity profile becomes parabolic-like, similar to that of an infinite parallel plate, due to the strong viscous effects of the horizontal boundaries. On the other hand, when the aspect ratio is greater than one (

$z$

, the velocity profile becomes parabolic-like, similar to that of an infinite parallel plate, due to the strong viscous effects of the horizontal boundaries. On the other hand, when the aspect ratio is greater than one (

![]() $\delta \gt 1$

), the channel deepens. Here, we observe exactly the opposite trend in the velocity profile due to the stronger viscous effect of the vertical walls, which exhibits a parabolic profile along

$\delta \gt 1$

), the channel deepens. Here, we observe exactly the opposite trend in the velocity profile due to the stronger viscous effect of the vertical walls, which exhibits a parabolic profile along

![]() $y$

that flattens along

$y$

that flattens along

![]() $z$

. This may have a different effect on the stability of rotating microchannel flows.

$z$

. This may have a different effect on the stability of rotating microchannel flows.

Figure 2. The base-state velocity profile, incorporating streamwise slip (

![]() $l_x = 0.02$

), is plotted for different aspect ratios (

$l_x = 0.02$

), is plotted for different aspect ratios (

![]() $\delta = h/d$

). Specifically, panel (a) represents the wall-normal base flow by setting

$\delta = h/d$

). Specifically, panel (a) represents the wall-normal base flow by setting

![]() $ z = 0$

, while panel (b) corresponds to the spanwise base flow by setting

$ z = 0$

, while panel (b) corresponds to the spanwise base flow by setting

![]() $ y = 0$

. These profiles provide insights into the influence of aspect ratio on the base-state velocity distribution under slip conditions. The discrepancy in the magnitude of velocity between (a) and (b) is due to the reduction of the length scale along the

$ y = 0$

. These profiles provide insights into the influence of aspect ratio on the base-state velocity distribution under slip conditions. The discrepancy in the magnitude of velocity between (a) and (b) is due to the reduction of the length scale along the

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

directions to

$z$

directions to

![]() $[-1,1]$

.

$[-1,1]$

.

To better capture the effects of aspect ratio and its interaction with rotation, we formulate the linear stability equations separately in terms of the

![]() $ y$

and

$ y$

and

![]() $ z$

directions. For aspect ratios

$ z$

directions. For aspect ratios

![]() $\delta \gt 1$

, the computational domain is defined as

$\delta \gt 1$

, the computational domain is defined as

![]() $[-1,1] \times [-\delta , \delta ]$

, whereas for

$[-1,1] \times [-\delta , \delta ]$

, whereas for

![]() $\delta \lt 1$

, the domain is chosen as

$\delta \lt 1$

, the domain is chosen as

![]() $[-(1/\delta), ( {1}/{\delta })] \times [-1,1]$

. For the unit aspect ratio case (

$[-(1/\delta), ( {1}/{\delta })] \times [-1,1]$

. For the unit aspect ratio case (

![]() $\delta = 1$

), we present results using one-dimensional base states along both wall-normal and spanwise directions. These represent two orthogonal shear configurations in a square duct. The close agreement in the qualitative stability trends obtained from these two independent analyses gives confidence in the physical interpretation of the results. However, we note that a full two-dimensional base flow may be required for more precise quantitative results near

$\delta = 1$

), we present results using one-dimensional base states along both wall-normal and spanwise directions. These represent two orthogonal shear configurations in a square duct. The close agreement in the qualitative stability trends obtained from these two independent analyses gives confidence in the physical interpretation of the results. However, we note that a full two-dimensional base flow may be required for more precise quantitative results near

![]() $\delta \approx 1$

. This approach ensures that the hydraulic diameter of the channel remains unchanged, while allowing for a more precise analysis of stability characteristics across different aspect ratios.

$\delta \approx 1$

. This approach ensures that the hydraulic diameter of the channel remains unchanged, while allowing for a more precise analysis of stability characteristics across different aspect ratios.

2.2. Wall-normal linear stability equations

Taking into account the viscous effects of the walls at

![]() $ y^* = -d$

and

$ y^* = -d$

and

![]() $ y^* = +d$

, we consider the wall-normal base velocity

$ y^* = +d$

, we consider the wall-normal base velocity

![]() $ U_1^*(y^*)$

. In this case, the base-state velocity is treated as a function of

$ U_1^*(y^*)$

. In this case, the base-state velocity is treated as a function of

![]() $ y^* \in [-d,d]$

only, as illustrated in figure 2(a). Then with a small disturbance

$ y^* \in [-d,d]$

only, as illustrated in figure 2(a). Then with a small disturbance

![]() $(\tilde {u}^*,\tilde {v}^*,\tilde {w}^*)$

the fully developed base velocity

$(\tilde {u}^*,\tilde {v}^*,\tilde {w}^*)$

the fully developed base velocity

![]() $(U_1^*(y^*),0,0)$

changes to

$(U_1^*(y^*),0,0)$

changes to

![]() $(U_1^*(y^*)+\tilde {u}^*,\tilde {v}^*,\tilde {w}^*)$

. By substituting the perturbed velocity into the governing equations (2.1) and (2.2) and linearising the equations for the small disturbance, we obtain the following dimensionless mass and momentum balance equations that govern the perturbed flow in the reference frame of the rotating microchannel:

$(U_1^*(y^*)+\tilde {u}^*,\tilde {v}^*,\tilde {w}^*)$

. By substituting the perturbed velocity into the governing equations (2.1) and (2.2) and linearising the equations for the small disturbance, we obtain the following dimensionless mass and momentum balance equations that govern the perturbed flow in the reference frame of the rotating microchannel:

\begin{align}& \frac {\partial u}{\partial t}+U_1\frac {\partial u}{\partial x}+ \frac {\partial U_1}{\partial y}v=-\frac {\partial p}{\partial x} +\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial x^2}+\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial y^2}+\left (\frac {2}{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial z^2}\right ]+({\textit{Ro}})v, \end{align}

\begin{align}& \frac {\partial u}{\partial t}+U_1\frac {\partial u}{\partial x}+ \frac {\partial U_1}{\partial y}v=-\frac {\partial p}{\partial x} +\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial x^2}+\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial y^2}+\left (\frac {2}{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial z^2}\right ]+({\textit{Ro}})v, \end{align}

\begin{align}&\qquad \frac {\partial v}{\partial t}+U_1\frac {\partial v}{\partial x}=-\frac {\partial p}{\partial y} +\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial x^2}+ \frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial y^2}+\left (\frac {2}{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial z^2}\right ]-({\textit{Ro}}) u, \end{align}

\begin{align}&\qquad \frac {\partial v}{\partial t}+U_1\frac {\partial v}{\partial x}=-\frac {\partial p}{\partial y} +\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial x^2}+ \frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial y^2}+\left (\frac {2}{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial z^2}\right ]-({\textit{Ro}}) u, \end{align}

\begin{align}&\quad \frac {\partial w}{\partial t}+U_1\frac {\partial w}{\partial x} =-\left (\frac {2}{1+\delta }\right )\frac {\partial p}{\partial z}+\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial x^2}+ \frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial y^2}+\left (\frac {2}{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial z^2}\right ]\!. \\[9pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align}&\quad \frac {\partial w}{\partial t}+U_1\frac {\partial w}{\partial x} =-\left (\frac {2}{1+\delta }\right )\frac {\partial p}{\partial z}+\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial x^2}+ \frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial y^2}+\left (\frac {2}{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial z^2}\right ]\!. \\[9pt] \nonumber \end{align}

Then

![]() $y\in [-1,1]$

and the slip boundary conditions at the walls

$y\in [-1,1]$

and the slip boundary conditions at the walls

![]() $(y=\pm 1$

) reduce to

$(y=\pm 1$

) reduce to

\begin{align}& u+l_x \frac {\partial u}{\partial y}=0,\qquad w+l_z \frac {\partial w}{\partial y}=0\quad \mbox{and}\quad v=0 \mbox{ at }y=1, \nonumber \\& u-l_x \frac {\partial u}{\partial y}=0,\qquad w-l_z \frac {\partial w}{\partial y}=0\quad \mbox{and}\quad v=0 \mbox{ at } y=-1. \end{align}

\begin{align}& u+l_x \frac {\partial u}{\partial y}=0,\qquad w+l_z \frac {\partial w}{\partial y}=0\quad \mbox{and}\quad v=0 \mbox{ at }y=1, \nonumber \\& u-l_x \frac {\partial u}{\partial y}=0,\qquad w-l_z \frac {\partial w}{\partial y}=0\quad \mbox{and}\quad v=0 \mbox{ at } y=-1. \end{align}

Now (2.10)–(2.13) reform into a set of coupled differential equations in terms of velocity

![]() $v$

and vorticity

$v$

and vorticity

![]() $\eta =( {\partial u}/{\partial z})-( {\partial w}/{\partial x})$

, i.e.

$\eta =( {\partial u}/{\partial z})-( {\partial w}/{\partial x})$

, i.e.

with the following revised boundary conditions in terms of

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $\eta$

:

$\eta$

:

Here

![]() $l=l_x=l_z$

is the isotropic and symmetric slip length. The derivative operator

$l=l_x=l_z$

is the isotropic and symmetric slip length. The derivative operator

![]() $D_1$

along

$D_1$

along

![]() $y$

, Reynolds number (

$y$

, Reynolds number (

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

) and rotation number (

${\textit{Re}}$

) and rotation number (

![]() $Ro$

) are respectively defined as:

$Ro$

) are respectively defined as:

For linear stability analysis of the present study, we introduce the normal mode assumption in the form

where the variables

![]() $\tilde v$

and

$\tilde v$

and

![]() $\tilde \eta$

denote the amplitude corresponding to the perturbation wave of wall-normal velocity and vorticity. Moreover,

$\tilde \eta$

denote the amplitude corresponding to the perturbation wave of wall-normal velocity and vorticity. Moreover,

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $\beta _1$

represent the streamwise and spanwise wavenumbers, respectively. To ensure a proper fit to the chosen domain based on the aspect ratio, the spanwise wavenumber

$\beta _1$

represent the streamwise and spanwise wavenumbers, respectively. To ensure a proper fit to the chosen domain based on the aspect ratio, the spanwise wavenumber

![]() $\beta _1$

is scaled by a factor of

$\beta _1$

is scaled by a factor of

![]() $ (1+\delta)/{2\delta }$

. This scaling accounts for variations in the domain size, ensuring consistency in the representation of spanwise disturbances across different aspect ratios. The temporal frequency is

$ (1+\delta)/{2\delta }$

. This scaling accounts for variations in the domain size, ensuring consistency in the representation of spanwise disturbances across different aspect ratios. The temporal frequency is

![]() $\omega (\alpha ,\beta _1)$

, where

$\omega (\alpha ,\beta _1)$

, where

![]() $(\omega =\omega _r +i\omega _i)$

is the frequency of the disturbance. Applying the normal mode of variables

$(\omega =\omega _r +i\omega _i)$

is the frequency of the disturbance. Applying the normal mode of variables

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $\eta$

defined in (2.19) into (2.15) and (2.16). Then, a coupled Orr–Sommerfield–Squire system is obtained in the matrix form given by

$\eta$

defined in (2.19) into (2.15) and (2.16). Then, a coupled Orr–Sommerfield–Squire system is obtained in the matrix form given by

\begin{equation} -i\omega \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} B^1_{11} & 0 \\ 0 & B^1_{22} \end{pmatrix}}_{B_1} \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} \tilde v \\ \tilde {\eta } \end{pmatrix}}_{q_1} =\underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} A^1_{11} & A^1_{12}\\ A^1_{21} & A^1_{22} \end{pmatrix}}_{A_1} \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} \tilde v \\ \tilde {\eta } \end{pmatrix}}_{q_1}\!. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} -i\omega \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} B^1_{11} & 0 \\ 0 & B^1_{22} \end{pmatrix}}_{B_1} \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} \tilde v \\ \tilde {\eta } \end{pmatrix}}_{q_1} =\underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} A^1_{11} & A^1_{12}\\ A^1_{21} & A^1_{22} \end{pmatrix}}_{A_1} \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} \tilde v \\ \tilde {\eta } \end{pmatrix}}_{q_1}\!. \end{equation}

The above-mentioned operators are defined as

\begin{gather} A^1_{11}=\frac {\varDelta _1^2}{\textit{Re}}-i\alpha U_1\varDelta _1 +i\alpha U_1'';\qquad A^1_{12}=-i\frac {1}{\delta }\beta _1 Ro, \nonumber \\ A^1_{21}=i\frac {1}{\delta }\beta _1\left [Ro- U_1'\right ];\qquad A^1_{22}=\frac {\varDelta _1}{\textit{Re}}-i\alpha U_1,\qquad \nonumber \\ B^1_{11}=\varDelta _1 ;\qquad B^1_{22}=I, \end{gather}

\begin{gather} A^1_{11}=\frac {\varDelta _1^2}{\textit{Re}}-i\alpha U_1\varDelta _1 +i\alpha U_1'';\qquad A^1_{12}=-i\frac {1}{\delta }\beta _1 Ro, \nonumber \\ A^1_{21}=i\frac {1}{\delta }\beta _1\left [Ro- U_1'\right ];\qquad A^1_{22}=\frac {\varDelta _1}{\textit{Re}}-i\alpha U_1,\qquad \nonumber \\ B^1_{11}=\varDelta _1 ;\qquad B^1_{22}=I, \end{gather}

where

![]() $\varDelta _1^2=D_1^2-(\alpha ^2+({ {\beta _1^2}/{\delta ^2}}))$

and

$\varDelta _1^2=D_1^2-(\alpha ^2+({ {\beta _1^2}/{\delta ^2}}))$

and

![]() $I$

are the identity matrices. The matrix equation (2.20) along with the six boundary conditions (2.17) provided a fourth-order eigenvalue problem and has the representation of the form

$I$

are the identity matrices. The matrix equation (2.20) along with the six boundary conditions (2.17) provided a fourth-order eigenvalue problem and has the representation of the form

![]() $-i\omega B_1q_1=A_1q_1$

. This eigenvalue problem is solved by the Chebyshev spectral collocation method (Schmid & Henningson Reference Schmid and Henningson2001).

$-i\omega B_1q_1=A_1q_1$

. This eigenvalue problem is solved by the Chebyshev spectral collocation method (Schmid & Henningson Reference Schmid and Henningson2001).

2.3. Spanwise linear stability equations

Similarly, by accounting for the viscous effects of the vertical walls at

![]() $ z^* = -h$

and

$ z^* = -h$

and

![]() $ z^* = +h$

, we consider the spanwise base velocity

$ z^* = +h$

, we consider the spanwise base velocity

![]() $ {U_2}^*(z^*)$

. Consequently, the base-state velocity is treated as a function of

$ {U_2}^*(z^*)$

. Consequently, the base-state velocity is treated as a function of

![]() $ z^* \in [-h,h]$

only, as illustrated in figure 2(b). Then with a small disturbance

$ z^* \in [-h,h]$

only, as illustrated in figure 2(b). Then with a small disturbance

![]() $(\tilde {u}^*,\tilde {v}^*,\tilde {w}^*)$

the fully developed base velocity

$(\tilde {u}^*,\tilde {v}^*,\tilde {w}^*)$

the fully developed base velocity

![]() $(U_2^*(z^*),0,0)$

changes to

$(U_2^*(z^*),0,0)$

changes to

![]() $(U_2^*(z^*)+\tilde {u}^*,\tilde {v}^*,\tilde {w}^*)$

. By substituting the perturbed velocity into the governing equations (2.1) and (2.2) and linearising the equations for the small disturbance, we obtain the following dimensionless mass and momentum balance equations that govern the perturbed flow in the reference frame of the rotating microchannel:

$(U_2^*(z^*)+\tilde {u}^*,\tilde {v}^*,\tilde {w}^*)$

. By substituting the perturbed velocity into the governing equations (2.1) and (2.2) and linearising the equations for the small disturbance, we obtain the following dimensionless mass and momentum balance equations that govern the perturbed flow in the reference frame of the rotating microchannel:

\begin{align}& \frac {\partial u}{\partial t}+U_2\frac {\partial u}{\partial x}+ \frac {\partial U_2}{\partial z}w=-\frac {\partial p}{\partial x} +\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial x^2}+\left (\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial y^2}+\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial z^2}\right ]+({\textit{Ro}}) v, \end{align}

\begin{align}& \frac {\partial u}{\partial t}+U_2\frac {\partial u}{\partial x}+ \frac {\partial U_2}{\partial z}w=-\frac {\partial p}{\partial x} +\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial x^2}+\left (\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial y^2}+\frac {\partial ^2 u}{\partial z^2}\right ]+({\textit{Ro}}) v, \end{align}

\begin{align}& \frac {\partial v}{\partial t}+U_2\frac {\partial v}{\partial x}=-\left (\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\right )\frac {\partial p}{\partial y} +\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial x^2}+ \left (\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial y^2}+\frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial z^2}\right ]-({\textit{Ro}}) u, \end{align}

\begin{align}& \frac {\partial v}{\partial t}+U_2\frac {\partial v}{\partial x}=-\left (\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\right )\frac {\partial p}{\partial y} +\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial x^2}+ \left (\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial y^2}+\frac {\partial ^2 v}{\partial z^2}\right ]-({\textit{Ro}}) u, \end{align}

\begin{align}&\qquad\qquad \frac {\partial w}{\partial t}+U_2\frac {\partial w}{\partial x} =-\frac {\partial p}{\partial z}+\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial x^2}+ \left (\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial y^2}+\frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial z^2}\right ]\!. \end{align}

\begin{align}&\qquad\qquad \frac {\partial w}{\partial t}+U_2\frac {\partial w}{\partial x} =-\frac {\partial p}{\partial z}+\frac {1}{\textit{Re}}\left [\frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial x^2}+ \left (\frac {2\delta }{1+\delta }\right )^2\frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial y^2}+\frac {\partial ^2 w}{\partial z^2}\right ]\!. \end{align}

Then

![]() $z\in [-1,1]$

and the slip boundary conditions at the walls

$z\in [-1,1]$

and the slip boundary conditions at the walls

![]() $(z=\pm 1$

) reduce to

$(z=\pm 1$

) reduce to

\begin{align}& u+l_x \frac {\partial u}{\partial z}=0,\qquad v+l_{\!y} \frac {\partial v}{\partial z}=0\quad \mbox{and}\quad w=0 \,\mbox{at}\,z=1, \nonumber \\& u-l_x \frac {\partial u}{\partial z}=0,\qquad v-l_{\!y} \frac {\partial v}{\partial z}=0\quad \mbox{and}\quad w=0 \,\mbox{at}\, z=-1. \end{align}

\begin{align}& u+l_x \frac {\partial u}{\partial z}=0,\qquad v+l_{\!y} \frac {\partial v}{\partial z}=0\quad \mbox{and}\quad w=0 \,\mbox{at}\,z=1, \nonumber \\& u-l_x \frac {\partial u}{\partial z}=0,\qquad v-l_{\!y} \frac {\partial v}{\partial z}=0\quad \mbox{and}\quad w=0 \,\mbox{at}\, z=-1. \end{align}

Now (2.22)–(2.25) reform into a set of coupled differential equations in terms of velocity

![]() $w$

and vorticity

$w$

and vorticity

![]() $\zeta =( {\partial v}/{\partial x})-( {\partial u}/{\partial y})$

, i.e.

$\zeta =( {\partial v}/{\partial x})-( {\partial u}/{\partial y})$

, i.e.

with the following revised boundary conditions in terms of

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $\eta$

:

$\eta$

:

Here

![]() $l=l_x=l_{\!y}$

is an isotropic and symmetric slip length. The derivative operator

$l=l_x=l_{\!y}$

is an isotropic and symmetric slip length. The derivative operator

![]() $D_2$

, Reynolds number (

$D_2$

, Reynolds number (

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

) and rotation number (

${\textit{Re}}$

) and rotation number (

![]() $Ro$

) are respectively written as

$Ro$

) are respectively written as

For linear stability analysis of the present study, we introduce the normal mode assumption in the form

where variables

![]() $\tilde w$

and

$\tilde w$

and

![]() $\tilde \zeta$

denote the amplitude corresponding to the perturbation wave of velocity (

$\tilde \zeta$

denote the amplitude corresponding to the perturbation wave of velocity (

![]() $w$

) and vorticity (

$w$

) and vorticity (

![]() $\zeta$

). Moreover,

$\zeta$

). Moreover,

![]() $\beta _2$

represents the spanwise wavenumber, which is scaled by a factor of

$\beta _2$

represents the spanwise wavenumber, which is scaled by a factor of

![]() $ (1+\delta)/{2}$

to ensure consistency with the chosen domain based on the aspect ratio. Additionally, the temporal frequency

$ (1+\delta)/{2}$

to ensure consistency with the chosen domain based on the aspect ratio. Additionally, the temporal frequency

![]() $\omega (\alpha ,\beta _2)$

, (

$\omega (\alpha ,\beta _2)$

, (

![]() $\omega = \omega _r + i\omega _i$

) characterises the disturbance, where

$\omega = \omega _r + i\omega _i$

) characterises the disturbance, where

![]() $\omega _r$

corresponds to the oscillatory behaviour and

$\omega _r$

corresponds to the oscillatory behaviour and

![]() $\omega _i$

determines the growth or decay of the perturbation over time. By applying the normal mode of variables

$\omega _i$

determines the growth or decay of the perturbation over time. By applying the normal mode of variables

![]() $w$

and

$w$

and

![]() $\zeta$

defined in (2.32) into (2.27) and (2.28), a coupled Orr-Sommerfield-Squire system is then obtained in the matrix form

$\zeta$

defined in (2.32) into (2.27) and (2.28), a coupled Orr-Sommerfield-Squire system is then obtained in the matrix form

\begin{equation} -i\omega \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} B^2_{11} & 0 \\ 0 & B^2_{22} \end{pmatrix}}_{B_2} \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} \tilde w \\ \tilde {\zeta } \end{pmatrix}}_{q_2} =\underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} A^2_{11} & A^2_{12}\\ A^2_{21} & A^2_{22} \end{pmatrix}}_{A_2} \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} \tilde w \\ \tilde {\zeta } \end{pmatrix}}_{q_2}\!. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} -i\omega \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} B^2_{11} & 0 \\ 0 & B^2_{22} \end{pmatrix}}_{B_2} \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} \tilde w \\ \tilde {\zeta } \end{pmatrix}}_{q_2} =\underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} A^2_{11} & A^2_{12}\\ A^2_{21} & A^2_{22} \end{pmatrix}}_{A_2} \underbrace {\begin{pmatrix} \tilde w \\ \tilde {\zeta } \end{pmatrix}}_{q_2}\!. \end{equation}

The above-mentioned operators are defined as

\begin{gather} A^2_{11}=\frac {\varDelta _2^2}{\textit{Re}}-i\alpha U_2\varDelta _2+i\alpha U_2'';\qquad A^2_{12}= -RoD_2, \nonumber \\ A^2_{21}=RoD_2+i\delta \beta _2 U_2';\qquad A^2_{22}=\frac {\varDelta _2}{\textit{Re}}-i\alpha U_2, \nonumber \\ B^2_{11}=\varDelta _2 ;\qquad B^2_{22}=I, \end{gather}

\begin{gather} A^2_{11}=\frac {\varDelta _2^2}{\textit{Re}}-i\alpha U_2\varDelta _2+i\alpha U_2'';\qquad A^2_{12}= -RoD_2, \nonumber \\ A^2_{21}=RoD_2+i\delta \beta _2 U_2';\qquad A^2_{22}=\frac {\varDelta _2}{\textit{Re}}-i\alpha U_2, \nonumber \\ B^2_{11}=\varDelta _2 ;\qquad B^2_{22}=I, \end{gather}

where

![]() $\varDelta _2^2=D_2^2-(\alpha ^2+\delta ^2{\beta _2}^2)$

and

$\varDelta _2^2=D_2^2-(\alpha ^2+\delta ^2{\beta _2}^2)$

and

![]() $I$

are the identity matrices. The matrix equation (2.33) along with the six boundary conditions ((2.29), (2.30)) provides a fourth-order eigenvalue problem and has the representation of the form

$I$

are the identity matrices. The matrix equation (2.33) along with the six boundary conditions ((2.29), (2.30)) provides a fourth-order eigenvalue problem and has the representation of the form

![]() $-i\omega B_2q_2=A_2q_2$

. This eigenvalue problem is solved by the Chebyshev spectral collocation method (Schmid & Henningson Reference Schmid and Henningson2001).

$-i\omega B_2q_2=A_2q_2$

. This eigenvalue problem is solved by the Chebyshev spectral collocation method (Schmid & Henningson Reference Schmid and Henningson2001).

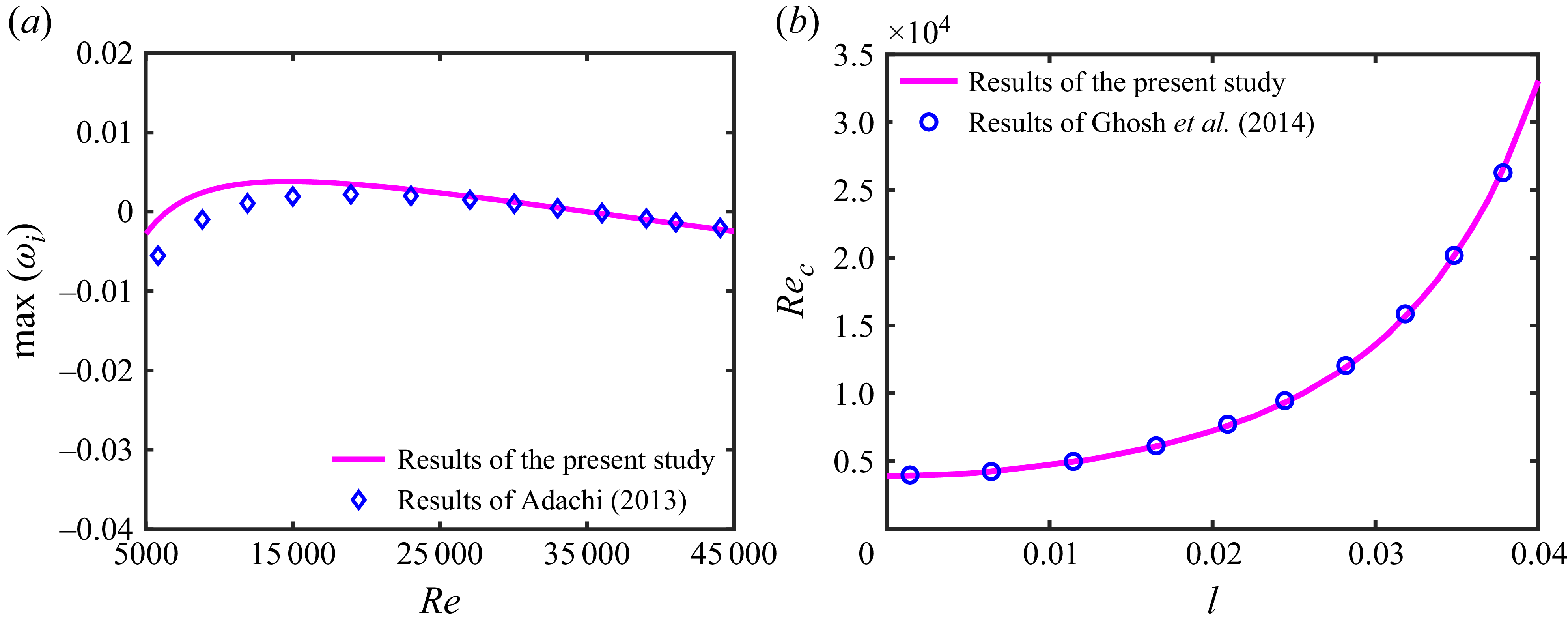

3. Validation of the present results

We solve the eigenvalue problems given in (2.20) and (2.33) numerically to obtain the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the wall-normal and spanwise operators. To validate our numerical code, we compute the growth rate of the most unstable modes for no-slip, non-rotating channel flows with

![]() $\alpha =0.91$

and an aspect ratio of

$\alpha =0.91$

and an aspect ratio of

![]() $\delta =5$

. Then, the computed results are compared with those of Adachi (Reference Adachi2013), as shown in figure 3(a). Figure 3(b) also presents a validation of our computational results incorporating slip boundary conditions at the wall, by comparing them with the findings of Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Usha and Sahu2014) for the non-rotating case (

$\delta =5$

. Then, the computed results are compared with those of Adachi (Reference Adachi2013), as shown in figure 3(a). Figure 3(b) also presents a validation of our computational results incorporating slip boundary conditions at the wall, by comparing them with the findings of Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Usha and Sahu2014) for the non-rotating case (

![]() $Ro = 0.0$

). In both cases, the maximum velocity of the base flow is normalised to unity. These results show a good agreement with those of Adachi (Reference Adachi2013) and Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Usha and Sahu2014), who studied a special case of the present study.

$Ro = 0.0$

). In both cases, the maximum velocity of the base flow is normalised to unity. These results show a good agreement with those of Adachi (Reference Adachi2013) and Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Usha and Sahu2014), who studied a special case of the present study.

Figure 3. (a) Comparison of the maximum growth rate for non-rotating (

![]() $Ro=0.0$

) flow in a microchannel, when we set

$Ro=0.0$

) flow in a microchannel, when we set

![]() $\delta =5,\,\alpha =0.91$

and

$\delta =5,\,\alpha =0.91$

and

![]() $l=0.0$

. (b) Comparison of the critical Reynolds number depending on slip length, with the results of Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Usha and Sahu2014) in the case of a non-rotating system when

$l=0.0$

. (b) Comparison of the critical Reynolds number depending on slip length, with the results of Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Usha and Sahu2014) in the case of a non-rotating system when

![]() $\delta =1$

. In the setting of these parameters in the present computational study, we find physical alignment with those of Adachi (Reference Adachi2013) and Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Usha and Sahu2014).

$\delta =1$

. In the setting of these parameters in the present computational study, we find physical alignment with those of Adachi (Reference Adachi2013) and Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Usha and Sahu2014).

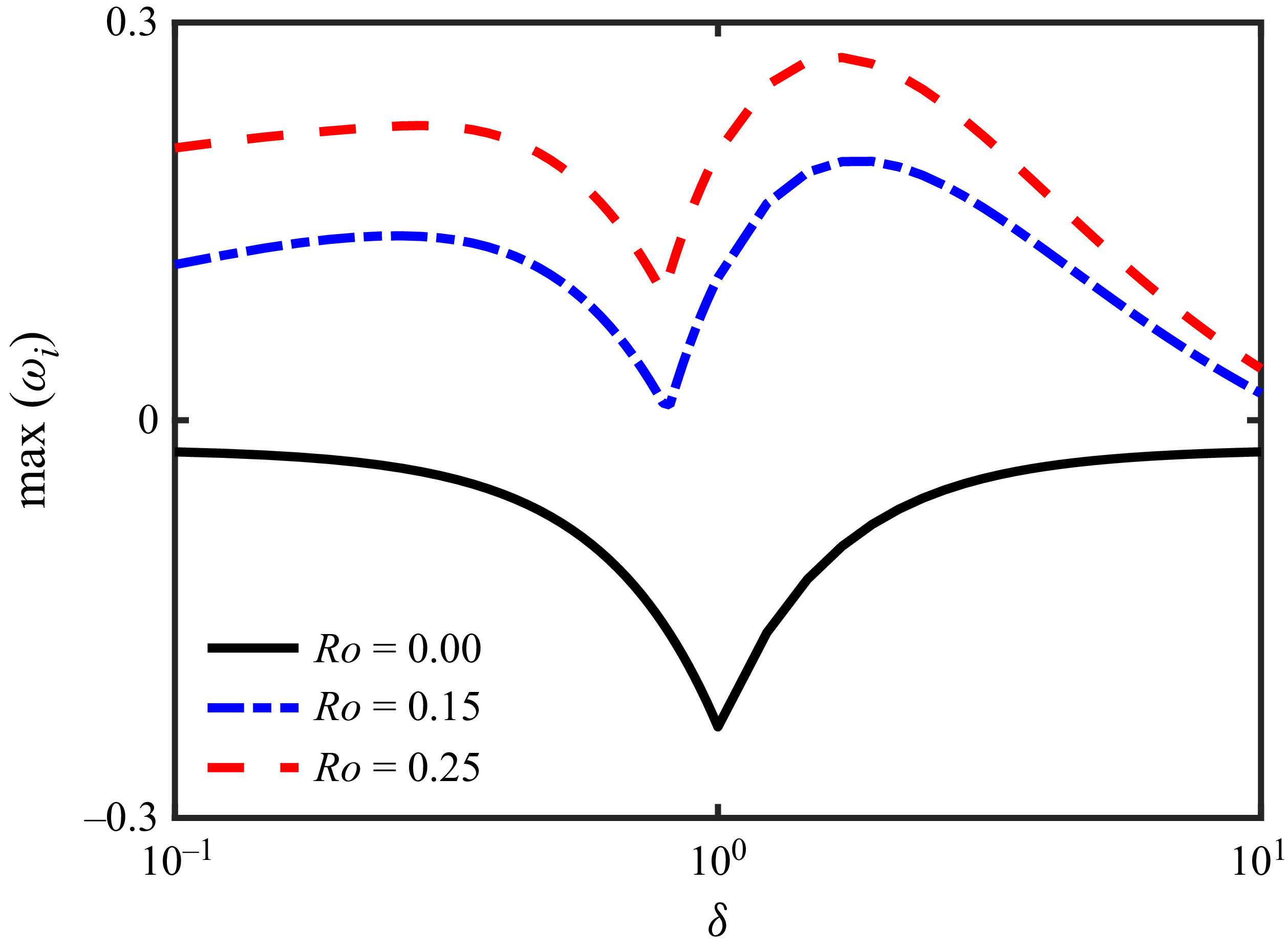

Figure 4. Comparison of the maximum growth rates versus aspect ratio between non-rotating and rotating cases from both wall-normal and spanwise modes at

![]() ${\textit{Re}} = 200$

, when

${\textit{Re}} = 200$

, when

![]() $\beta _1 = \beta _2=6.5$

,

$\beta _1 = \beta _2=6.5$

,

![]() $\alpha = 0.15$

and

$\alpha = 0.15$

and

![]() $l=0.02$

. The maximum growth rate curve shows symmetry about the aspect ratio

$l=0.02$

. The maximum growth rate curve shows symmetry about the aspect ratio

![]() $\delta =1$

in the absence of rotation only.

$\delta =1$

in the absence of rotation only.

4. Insights and interpretation of modal analysis

4.1. Impact of aspect ratio on stability characteristics

The aspect ratio (

![]() $\delta$

) of a channel, defined as the ratio of its height to its width, plays a crucial role in designing the channel geometry and influencing flow structure across different directions. Even for the small disturbances within the flow, the aspect ratio can be significantly affected, resulting in a key factor in the instability of the system. This study focuses on the intricate relationship between aspect ratio and the linear stability of rotating microchannel flows, shedding light on how variations in aspect ratio impact flow behaviour and instability.

$\delta$

) of a channel, defined as the ratio of its height to its width, plays a crucial role in designing the channel geometry and influencing flow structure across different directions. Even for the small disturbances within the flow, the aspect ratio can be significantly affected, resulting in a key factor in the instability of the system. This study focuses on the intricate relationship between aspect ratio and the linear stability of rotating microchannel flows, shedding light on how variations in aspect ratio impact flow behaviour and instability.

The maximum growth rates of the wall-normal and spanwise modes are presented in figure 4 as functions of aspect ratio to compare the rotating and non-rotating cases. For the non-rotating case, a symmetric growth rate curve is observed (black solid lines in figure 4) on either side of

![]() $\delta = 1$

, meaning the growth rates for

$\delta = 1$

, meaning the growth rates for

![]() $\delta \lt 1$

and

$\delta \lt 1$

and

![]() $\delta \gt 1$

are the same. However, this symmetry is lost when spanwise rotation is introduced and the growth rate curve becomes asymmetric. Additionally, a positive temporal growth rate (

$\delta \gt 1$

are the same. However, this symmetry is lost when spanwise rotation is introduced and the growth rate curve becomes asymmetric. Additionally, a positive temporal growth rate (

![]() $\omega_i\gt0$

) indicates the onset of instability. Since rotation causes different growth behaviours for low aspect ratios

$\omega_i\gt0$

) indicates the onset of instability. Since rotation causes different growth behaviours for low aspect ratios

![]() $\delta \in (0.1, 1)$

and high aspect ratios

$\delta \in (0.1, 1)$

and high aspect ratios

![]() $\delta \in (1, 10)$

, we examine this effect in more detail in the next section.

$\delta \in (1, 10)$

, we examine this effect in more detail in the next section.

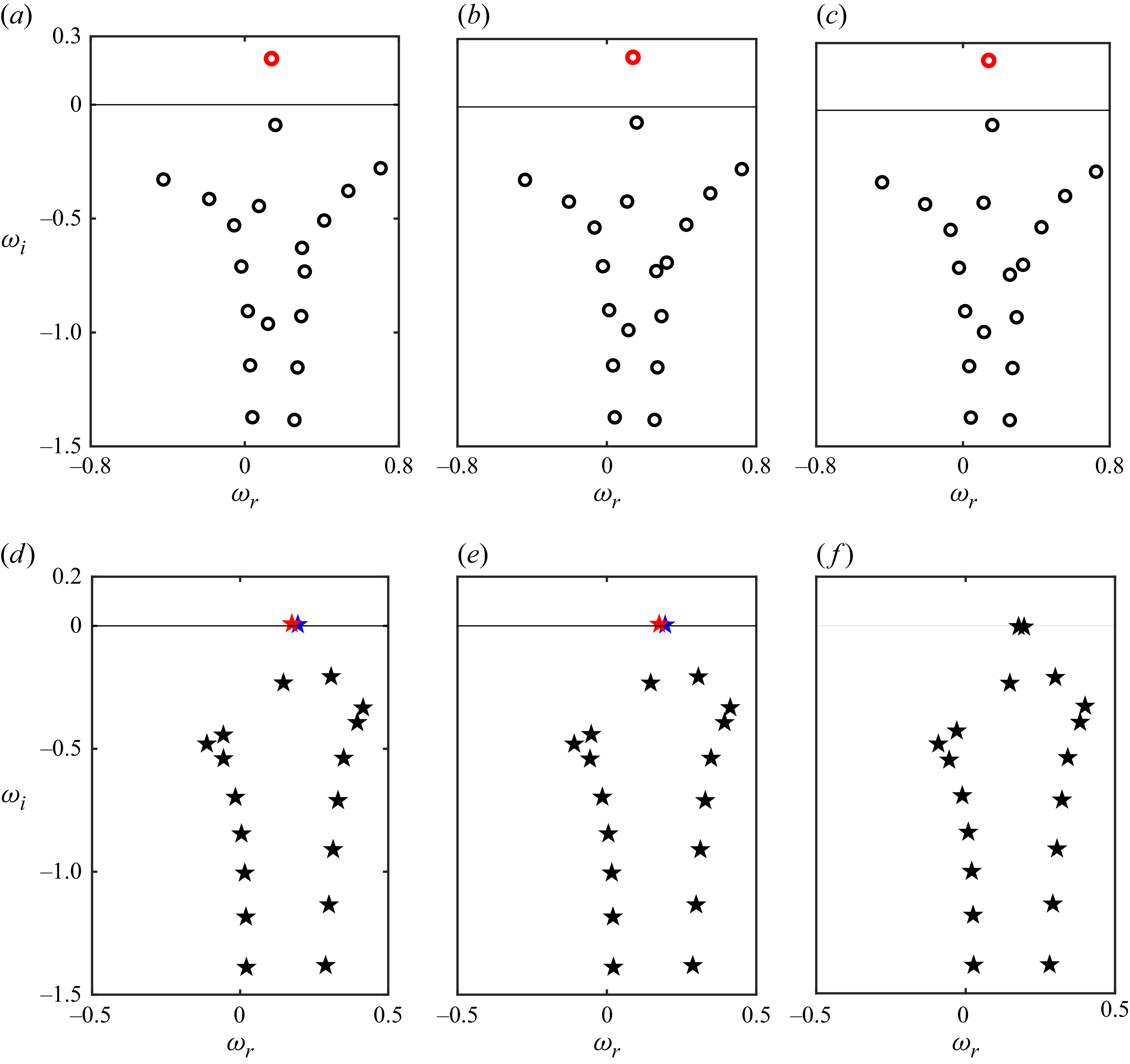

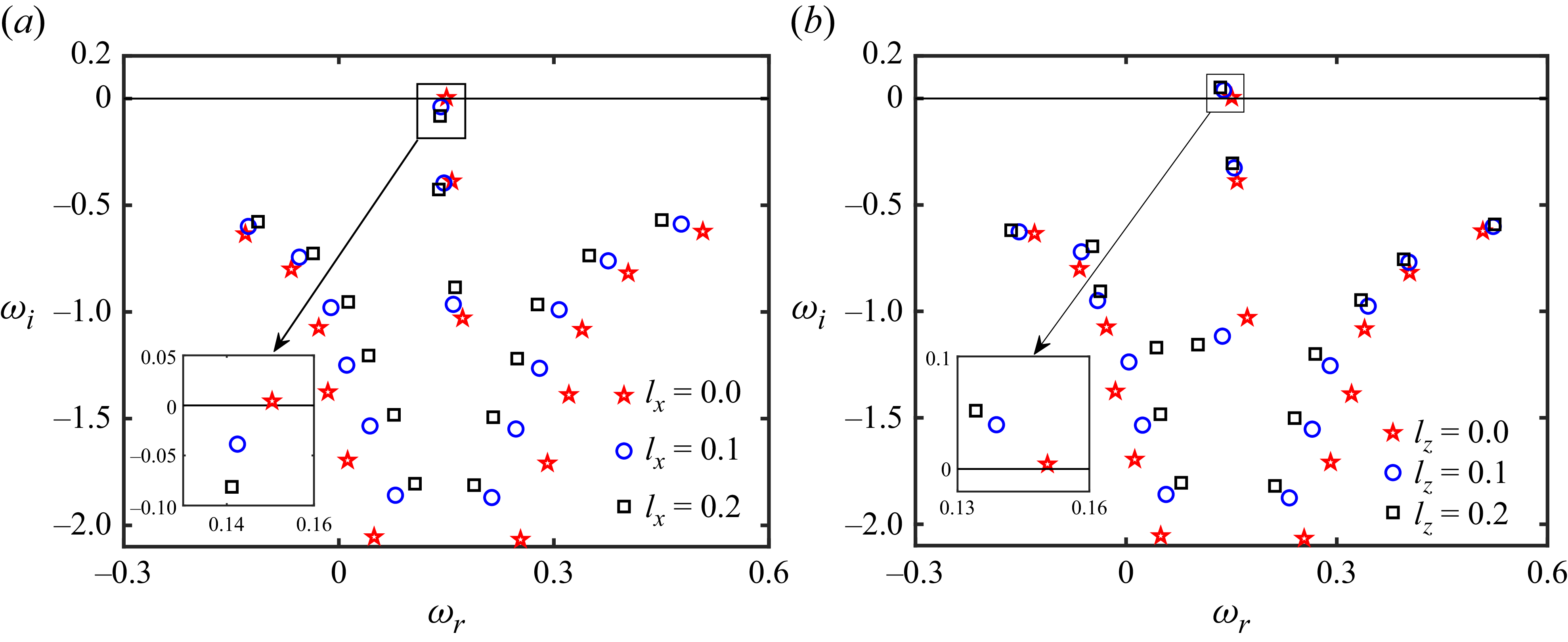

4.1.1. Eigenspectrum analysis for varying aspect ratios

The eigenvalue spectrum provides critical insight into the stability characteristics of the flow by identifying unstable modes and their dependence on flow parameters. In this study we examine how the aspect ratio (

![]() $\delta$

) influences the eigenvalue distribution in the complex plane. The real and imaginary parts of the eigenvalues are plotted separately for wall-normal and spanwise analyses, where black circles represent all stable modes, while red and blue circles indicate the most unstable modes. For

$\delta$

) influences the eigenvalue distribution in the complex plane. The real and imaginary parts of the eigenvalues are plotted separately for wall-normal and spanwise analyses, where black circles represent all stable modes, while red and blue circles indicate the most unstable modes. For

![]() $\delta \geqslant 1$

, the eigenvalue spectrum is plotted for

$\delta \geqslant 1$

, the eigenvalue spectrum is plotted for

![]() $\delta = 1, 2$

and

$\delta = 1, 2$

and

![]() $5$

(see figure 5

a–c). In each case, due to the presence of rotation, at least one unstable mode emerges. However, as the aspect ratio increases from

$5$

(see figure 5

a–c). In each case, due to the presence of rotation, at least one unstable mode emerges. However, as the aspect ratio increases from

![]() $\delta = 1$

to

$\delta = 1$

to

![]() $\delta = 5$

, we observe an increase in the growth rate of the most unstable wall-normal modes. This suggests that a larger aspect ratio enhances instability in the wall-normal direction. On the other hand, for

$\delta = 5$

, we observe an increase in the growth rate of the most unstable wall-normal modes. This suggests that a larger aspect ratio enhances instability in the wall-normal direction. On the other hand, for

![]() $\delta \leqslant 1$

, the eigenvalue spectrum is plotted at

$\delta \leqslant 1$

, the eigenvalue spectrum is plotted at

![]() $\delta = 0.2, 0.5$

and

$\delta = 0.2, 0.5$

and

![]() $1$

(see figure 5

d–f) under the same rotation rates. Unlike the previous case, no unstable modes are observed at

$1$

(see figure 5

d–f) under the same rotation rates. Unlike the previous case, no unstable modes are observed at

![]() $\delta = 1$

, indicating that the flow remains stable in this configuration. However, the wall-normal modes become more pronounced when rotation is applied about the spanwise direction at

$\delta = 1$

, indicating that the flow remains stable in this configuration. However, the wall-normal modes become more pronounced when rotation is applied about the spanwise direction at

![]() $\delta = 1$

. For

$\delta = 1$

. For

![]() $\delta = 0.2$

and

$\delta = 0.2$

and

![]() $\delta = 0.5$

, two distinct pairs of unstable modes appear, denoted by red and blue pentagrams. This instability arises due to spanwise rotation, which amplifies disturbances originating from both walls (

$\delta = 0.5$

, two distinct pairs of unstable modes appear, denoted by red and blue pentagrams. This instability arises due to spanwise rotation, which amplifies disturbances originating from both walls (

![]() $z = \pm 1$

) and subsequently triggers secondary flow structures along the

$z = \pm 1$

) and subsequently triggers secondary flow structures along the

![]() $z$

direction. It is worthwhile to mention here that under the no rotation (

$z$

direction. It is worthwhile to mention here that under the no rotation (

![]() $Ro=0$

) case, for

$Ro=0$

) case, for

![]() $\delta =1$

, the eigenmodes in figures 5(a) and 5( f) are the same (cf. figure 4). Therefore, we can say that, for

$\delta =1$

, the eigenmodes in figures 5(a) and 5( f) are the same (cf. figure 4). Therefore, we can say that, for

![]() $\delta \gt 1$

, the channel topography is tall and narrow, leading to a base flow that is more parabolic along the wall-normal direction (

$\delta \gt 1$

, the channel topography is tall and narrow, leading to a base flow that is more parabolic along the wall-normal direction (

![]() $y$

, width) and relatively flat in the spanwise direction (

$y$

, width) and relatively flat in the spanwise direction (

![]() $z$

, height) (cf. figures 2

a and 2

b). This results in a stronger velocity gradient along

$z$

, height) (cf. figures 2

a and 2

b). This results in a stronger velocity gradient along

![]() $y$

, leading to wall-normal shear-dominant modes and favouring wall-normal instability modes. When rotation is introduced about the spanwise (

$y$

, leading to wall-normal shear-dominant modes and favouring wall-normal instability modes. When rotation is introduced about the spanwise (

![]() $z$

) direction, it modifies the development of wall-normal disturbances and induces secondary flow structures. These secondary flows redistribute momentum within the channel, altering the stability characteristics of the system.

$z$

) direction, it modifies the development of wall-normal disturbances and induces secondary flow structures. These secondary flows redistribute momentum within the channel, altering the stability characteristics of the system.

Figure 5. The eigenvalues corresponding to the wall-normal and spanwise modes are plotted in the complex plane, shown in the upper and lower rows, respectively. The results are presented in (a–c) with

![]() $\delta =1,2,5$

and in (d–f) with

$\delta =1,2,5$

and in (d–f) with

![]() $\delta =0.2,0.5,1$

for

$\delta =0.2,0.5,1$

for

![]() $ Re = 200$

,

$ Re = 200$

,

![]() $ Ro = 0.25$

,

$ Ro = 0.25$

,

![]() $ \beta _1= 6.5 \delta$

,

$ \beta _1= 6.5 \delta$

,

![]() $ \beta _2= {6.5}/{\delta }$

,

$ \beta _2= {6.5}/{\delta }$

,

![]() $ \alpha = 0.15$

and

$ \alpha = 0.15$

and

![]() $l=0.02$

. In these plots, the black coloured eigenvalues represent stable modes, while the red and blue coloured eigenvalues indicate the most unstable modes. However, the discrepancy between (a) and (f) is due to the rotated orientation point of view.

$l=0.02$

. In these plots, the black coloured eigenvalues represent stable modes, while the red and blue coloured eigenvalues indicate the most unstable modes. However, the discrepancy between (a) and (f) is due to the rotated orientation point of view.

For

![]() $\delta \lt 1$

, the channel topography is wide and short, causing the base flow to be more parabolic in the spanwise direction (

$\delta \lt 1$

, the channel topography is wide and short, causing the base flow to be more parabolic in the spanwise direction (

![]() $z$

) while base flow is flat along the wall-normal direction (

$z$

) while base flow is flat along the wall-normal direction (

![]() $y$

) (cf. figures 2

a and 2

b). In this case, the velocity gradient is stronger along

$y$

) (cf. figures 2

a and 2

b). In this case, the velocity gradient is stronger along

![]() $z$

, making spanwise shear dominant and resulting in spanwise shear-dominant modes. When rotation is applied about the spanwise (

$z$

, making spanwise shear dominant and resulting in spanwise shear-dominant modes. When rotation is applied about the spanwise (

![]() $z$

) direction, it interacts with the spanwise velocity gradient, modifying the evolution of spanwise disturbances. Moreover, the Coriolis force can generate secondary flow in terms of vorticity, further influencing the stability and transition characteristics of the flow.

$z$

) direction, it interacts with the spanwise velocity gradient, modifying the evolution of spanwise disturbances. Moreover, the Coriolis force can generate secondary flow in terms of vorticity, further influencing the stability and transition characteristics of the flow.

Figure 6. The perturbed velocity components in the case of the wall-normal disturbances are illustrated using contour plots for

![]() $ u$

and vector plots for

$ u$

and vector plots for

![]() $ v$

and

$ v$

and

![]() $ w$

, corresponding to the most unstable modes in the wall-normal direction that depend only on

$ w$

, corresponding to the most unstable modes in the wall-normal direction that depend only on

![]() $ y$

. Results are shown for (a)

$ y$

. Results are shown for (a)

![]() $\delta = 5$

, (b)

$\delta = 5$

, (b)

![]() $\delta = 2$

and (c)

$\delta = 2$

and (c)

![]() $\delta = 1$

, while other parameters are fixed at

$\delta = 1$

, while other parameters are fixed at

![]() $ Re = 200$

,

$ Re = 200$

,

![]() $ Ro = 0.25$

,

$ Ro = 0.25$

,

![]() $ \alpha = 0.15$

,

$ \alpha = 0.15$

,

![]() $ \beta _1 = 3.1$

and

$ \beta _1 = 3.1$

and

![]() $l=0.02$

.

$l=0.02$

.

4.1.2. Influence of aspect ratio on perturbed velocity flow structures

We examine the distribution of disturbance components across the channel to analyse the influence of rotation and aspect ratio on the perturbed velocity field. The nature of these disturbances is strongly dependent on the aspect ratio

![]() $\delta$

, which dictates whether wall-normal or spanwise inertial forces dominate, and on the applied rotation, which interacts with these forces to modify the flow instability characteristics. Additionally, rotation plays a crucial role in modifying these perturbations, either amplifying or suppressing specific modes, and inducing secondary flow structures that further influence the stability of the system. We present the optimal disturbance components corresponding to the most unstable wall-normal modes using a combination of vectors and contours in figure 6(a–c) for aspect ratios

$\delta$

, which dictates whether wall-normal or spanwise inertial forces dominate, and on the applied rotation, which interacts with these forces to modify the flow instability characteristics. Additionally, rotation plays a crucial role in modifying these perturbations, either amplifying or suppressing specific modes, and inducing secondary flow structures that further influence the stability of the system. We present the optimal disturbance components corresponding to the most unstable wall-normal modes using a combination of vectors and contours in figure 6(a–c) for aspect ratios

![]() $\delta = 5,2$

and

$\delta = 5,2$

and

![]() $1$

. In each case, we observe counter-rotating vortices, indicating the presence of secondary flow structures in the cross-section (

$1$

. In each case, we observe counter-rotating vortices, indicating the presence of secondary flow structures in the cross-section (

![]() $zy$

plane) of the channel. The size of these vortices transitions from large scale (large arrowhead and large counter-rotating vortices) to small scale (relatively small arrowhead and small counter-rotating vortices) as the aspect ratio decreases. At higher aspect ratios, the increased channel height allows disturbances to develop over a larger scale. However, due to the counter-rotating motion of the system, the vortices tend to remain closer to the inner boundary (

$zy$

plane) of the channel. The size of these vortices transitions from large scale (large arrowhead and large counter-rotating vortices) to small scale (relatively small arrowhead and small counter-rotating vortices) as the aspect ratio decreases. At higher aspect ratios, the increased channel height allows disturbances to develop over a larger scale. However, due to the counter-rotating motion of the system, the vortices tend to remain closer to the inner boundary (

![]() $y = -1$

), as illustrated in figure 6. The channel becomes deeper as the aspect ratio increases, leading to more pronounced perturbations in the velocity field. The contour colours further highlight this behaviour, showing that disturbance velocity is highest at

$y = -1$

), as illustrated in figure 6. The channel becomes deeper as the aspect ratio increases, leading to more pronounced perturbations in the velocity field. The contour colours further highlight this behaviour, showing that disturbance velocity is highest at

![]() $\delta = 5$

(figure 6

a) and significantly weaker at

$\delta = 5$

(figure 6

a) and significantly weaker at

![]() $\delta = 1$

(figure 6

c). Similarly, we plot the perturbed velocity components corresponding to the most unstable spanwise modes in the

$\delta = 1$

(figure 6

c). Similarly, we plot the perturbed velocity components corresponding to the most unstable spanwise modes in the

![]() $zy$

plane in figure 7(a–c) to analyse how disturbances evolve in a wide channel under the combined influence of aspect ratio and Coriolis force. The contour colours reveal that disturbances primarily originate from both walls (

$zy$

plane in figure 7(a–c) to analyse how disturbances evolve in a wide channel under the combined influence of aspect ratio and Coriolis force. The contour colours reveal that disturbances primarily originate from both walls (

![]() $z = \pm 1$

) due to spanwise rotation. This is because the Coriolis force interacts with the base flow, inducing a spanwise redistribution of momentum. Counter-rotating vortices emerge near the centreline of the

$z = \pm 1$

) due to spanwise rotation. This is because the Coriolis force interacts with the base flow, inducing a spanwise redistribution of momentum. Counter-rotating vortices emerge near the centreline of the

![]() $zy$

plane, distinguishing these spanwise modes from the wall-normal modes. This behaviour suggests that the spanwise rotation drives secondary flow structures, redistributing the disturbance energy differently compared with wall-normal instability modes. As the aspect ratio increases from

$zy$

plane, distinguishing these spanwise modes from the wall-normal modes. This behaviour suggests that the spanwise rotation drives secondary flow structures, redistributing the disturbance energy differently compared with wall-normal instability modes. As the aspect ratio increases from

![]() $\delta = 0.2$

to

$\delta = 0.2$

to

![]() $\delta = 1$

, the strength of the velocity vectors decreases, and the size of the vortices gradually reduces. This reduction in vortex strength can be attributed to the limited region available for spanwise disturbances to grow in a wider channel. At smaller aspect ratios, the Coriolis force acts more effectively on the spanwise flow due to the stronger velocity gradients, leading to a pronounced disturbance amplification. However, as

$\delta = 1$

, the strength of the velocity vectors decreases, and the size of the vortices gradually reduces. This reduction in vortex strength can be attributed to the limited region available for spanwise disturbances to grow in a wider channel. At smaller aspect ratios, the Coriolis force acts more effectively on the spanwise flow due to the stronger velocity gradients, leading to a pronounced disturbance amplification. However, as

![]() $\delta$

approaches 1, the velocity gradients in the spanwise direction weaken, causing the vortices to shrink and nearly dissipate at

$\delta$

approaches 1, the velocity gradients in the spanwise direction weaken, causing the vortices to shrink and nearly dissipate at

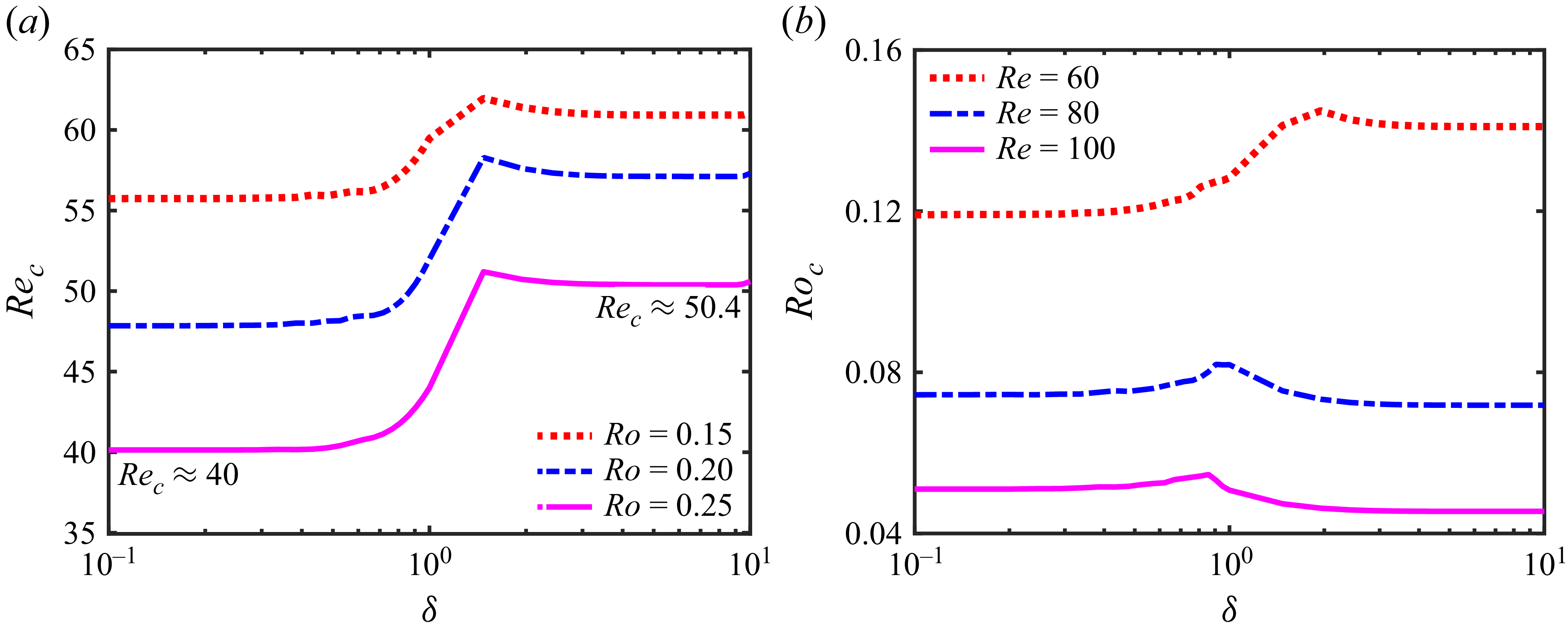

![]() $\delta = 1$