12.1 Introduction

This chapter responds to the vision for a more holistic and open-minded approach to thinking about science and its relationship with spirituality. There is an urgent need to create safe spaces for children to explore and grapple with the deeper questions in life – those that go beyond the existing curriculum. Where is home? What is eternity? Is forgiveness always possible? Why am I alive?

Annabel, an experienced primary class teacher and religious education expert, with expertise in developing philosophical thinking and practices in primary schools, shares her reflections and considers how we might develop more wholesome, open-ended responses to the big philosophical questions – both scientific and spiritual.

12.2 Practitioner Wisdom from Cambridge, UK

Although not top of typical teacher’s job description, one of the greatest joys and privileges of being an educator is to hold a space for children to wrestle with life’s big questions – questions that sit at the heart of every person. Teaching our children numeracy and literacy is essential; yet if we do not create room for them to grow their ‘inner worlds’, we do them a disservice. Providing children with these spaces for exploration may also have benefits beyond the school walls. I fully agree with Karl Hanson (Reference Hanson2015, p. 427), who says children are ‘capable of making productive contributions towards increasing our understanding not only of their own lifeworlds but also of society as a whole’. With these things in mind, is it not imperative that we carve out time and space in our overcrowded curricula?

I believe philosophy is an appropriate vehicle for this exploration. As outlined in Chapter 11, philosophy is able to combine the rigour and logic of science with profound aspects of spirituality, thus building a bridge between these two areas of study. ‘Inclusive in nature, providing opportunities for children’s authentic voices’ (Cassidy, Conrad and de Figueiroa-Rego, Reference Cassidy, Conrad and de Figueiroa-Rego2019, p. 2) – philosophical discourse can break down barriers and open up thoughtful conversation. It allows children a safe space to ask questions, to think deeply, to respectfully challenge and to be challenged in turn. By promoting critical thinking and reasoning, philosophy can help us navigate the complex relationship between science and spirituality. Through philosophy, we can ask questions about the nature of existence, consciousness and the link between our actions and ethics.

Philosophy with children is practical rather than academic, requiring teachers to act as facilitators of a structured and collaborative dialogue that is philosophical in nature. There is a lot of research about the impact of philosophy in the classroom. For example the Education Endowment Foundation (2014) found that children taking part in the Philosophy for Children (P4C) approach made approximately two months’ accelerated progress in reading and maths, while children from disadvantaged backgrounds made almost double that progress. Regularly taking part in philosophy sessions was also found to positively affect pupils’ confidence, communication and listening skills, as well as their self-esteem and behaviour. Philosophy within the classroom seems a worthwhile endeavour on many fronts.

In the case study that follows, I focus on how my school has sought to enable philosophical discourse in the classroom. This builds on some of the principles in the manifesto chapter, making them tangible and applicable for practitioners.

12.3 Case Study: Enabling Philosophical Discourse in the Classroom

Context

At the University of Cambridge Primary School, we have extended our initial curriculum from religious education (RE) to philosophy, religion and ethics (PRE). Our school aims to nurture compassionate citizens through exemplary teaching and learning. The continued development of our PRE curriculum is one way we seek to achieve this.

Aims and Objectives

The primary aim of extending the RE curriculum to include philosophy and ethics was to provide a dedicated space and opportunity for philosophical discourse to take place in classrooms, allowing children to explore and consider the deep questions of life. We also wanted to ensure that these vital questions were closely connected to the rest of the curriculum. This has been achieved in two ways: firstly, by using philosophy lessons to launch units of learning across the year and across the curriculum; and secondly, by making PRE a ‘spotlight’ subject for one half term in the year with a special emphasis on philosophy.

Launching Units of Learning through Philosophy

In all schools, a significant challenge is timetabling, namely how to fit philosophy lessons into an already crowded curriculum. One of our solutions has been to use philosophy lessons as a starting point for different units of learning. RE provides the most obvious opportunity for this, but it can work just as well at the start of any unit of learning in any subject, assuming a key theme can be identified. For example, if the children are due to learn about a world war in history, we might consider an overarching theme within this subject – for example power – and base the philosophy session on this theme to launch the unit of learning. If we are about to read a text in English, we might consider the overarching theme of the book – for example freedom. If the children are about to learn about the Muslim pilgrimage of Hajj, the theme might be ‘journeys’. A unit of learning about Christian belief in the afterlife might have an overarching theme of ‘eternity’. For most units of learning, a key theme can be identified.

Once the theme has been identified, the class then creates an initial ‘enquiry question’ in response to the theme. You’ll see an example of this later in the chapter. We then find a hook or stimulus to provoke thinking around this area. This could be anything: a short story or a film, a game, a piece of music, a quote, an object, a scenario or a provocative image. The aim of this stimulus is to generate interest in the theme and provoke dialogue, which carries on beyond the initial session into the rest of the unit of learning. We have found that children are much more likely to engage in subsequent learning if they begin with an interesting, and often more open, philosophical starting point.

Philosophy for Children (P4C)

Once the theme and stimulus have been decided, we follow the ten-step P4C enquiry structure. This approach, founded in the 1970s by Professor Matthew Lipman, was created in reaction to the perceived lack of reasoning skills in his undergraduate students (see e.g. Lipman, Reference Lipman1976). We have found it to be a highly effective way to bring philosophy into the classroom. The ten stages of the P4C enquiry are as follows:

1) Get set. Children begin by sitting in a circle. The ground rules for discussion are established.

2) Stimulus. Children are shown the stimulus.

3) Thinking time. Children are given time to independently and quietly reflect on the stimulus.

4) Question making. Children in small groups create questions they have about the stimulus. This could be done in three stages:

My first question is …

Which leads me to think …

Which makes me wonder …

By staging the questions like this, children’s third question is often deeper and broader and will lead to richer discussion.

5) Question airing. Children share their best question with the class, laying them down on the floor so the other children can see them.

6) Question choosing. Children vote for their favourite question and the one that they would like to discuss the most.

7) First thoughts. Children from the group whose question was chosen begin the discussion, sharing the rationale behind their question and their initial thoughts.

8) Building thoughts. Children from other groups engage in discussion. Stem sentences can be displayed during this part:

I agree because …

I disagree because …

While I agree with you on this part, I believe …

Building on what ——— said, …

I’d like to challenge what ——— said.

Throughout, teachers act as unbiased facilitators, summarising the discussion where necessary.

9) Last thoughts. This is a chance for pupils to offer their thoughts on what has been discussed.

10) Review. Reflections on the discussion: what went well and what could have been better. Reference to the ground rules might be made. Suggestions for further lines of enquiry are also invited.

Although at first glance the P4C structure may seem onerous, in practice it flows logically, and after a few enquiries, children become used to the structure and anticipate the flow of the discussion.

Philosophy as a Spotlight Subject

As well as using philosophy lessons to launch units of learning, in the final half term of summer, we turn PRE into a spotlight subject, creating additional lessons for each PRE unit – with a particular focus on philosophy and ethics – to raise the subject’s profile. Each year group has an overarching ethical or philosophical question for the half term. For example, in Year 6, children explore the question, Can we be certain of anything? In Year 4, children consider, What does it mean to live a good life? Towards the end of the unit, children are given extended time to creatively and collaboratively respond to their cohort’s overarching question.

As an example of a spotlight unit plan, here is a brief outline for Year 3, based on the Hindu belief of karma:

Lesson 1: P4C session based on a theme of choices and consequences and exploration of the question

What is the link between choices and consequences?

Lesson 2: Further philosophical discussion related to the question

Children explore various moral dilemmas and their responses

Lessons 3–5: Connecting the question to the main teaching content from the PRE curriculum

Children learn about the Hindu beliefs of karma and relate this back to the question.

Lesson 6: Assessment

Children share their learning about Hindu beliefs on the afterlife.

They consider their own personal views on life after death and evaluate the link between choices and consequences.

Lessons 7–10: Creative outcome as a response to learning

Children design and create their own high-quality board game inspired by snakes and ladders – a game inspired by the Hindu belief of karma, showcasing their learning from the unit

The Philosophy Corner

To generate further interest in PRE, both at school and at home, we also launched the ‘Philosophy Corner’. Each week during the final half term of the school year, a member of our school community (teacher, teaching assistant, child, governor) filmed a short video from a part of the world that inspired them to ask a big question. For example one of our Year 6 children created a video standing by a big oak tree in the corner of their neighbourhood. Commenting on how long the tree must have stood there, she asked the question, ‘Which things never change?’ Our executive headteacher filmed a video sitting by a piano, asking, ‘Can we really live without music?’ Our Forest School lead, sitting in the corner of a beautiful forest, asked, ‘Are the best things in life free?’ These videos were sent out to teachers each week during the half term, as well as to parents in newsletters. In doing so, all children from nursery to Year 6 were able to discuss the same question each week at home and at school.

Observed Impact

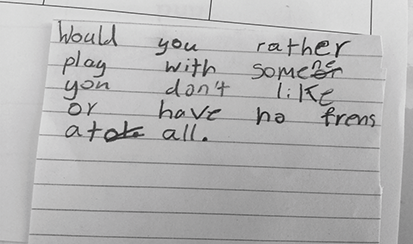

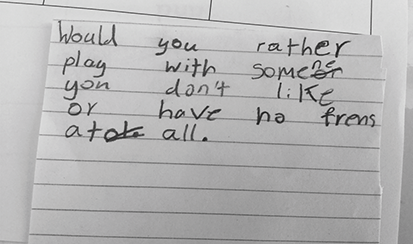

Feedback from teachers and pupils about philosophy in school has been overwhelmingly positive. Children enjoy having time to think and discuss interesting topics together. Staff have noted how philosophical discourse has impacted the development of children’s oracy and dialogue skills, as they have learned to agree, disagree and build on each other’s ideas. A couple of teachers commented that children who wouldn’t normally contribute to class discussion felt comfortable offering their views during philosophy discussions. Two of our Year 1 children were so inspired by the Philosophy Corner that they came up with their own big question, requesting that it be discussed within school: ‘Would you rather play with someone you don’t like or have no friends at all?’ – a powerful question for our children to settle in their own hearts and minds (Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1 Question from two of our children in Year 1.

Final Reflections

Creating time for philosophy in school has had incredible benefits. It has opened up a space for children to wrestle with some of the deeper questions in life. It has allowed them to develop their oracy and dialogue skills, to think for themselves and to think deeply about issues important to them. Children who often struggle to speak out have found their voices within these sessions, and teachers have appreciated having the time and space necessary to hear about the issues close to the children’s hearts. Philosophy has enriched our curriculum, in science and spirituality and beyond, and we are all the better for it. I fully expect that these subjective benefits, felt throughout our school community, to ultimately influence the objective progress data (test results, Ofsted reports) in the coming years.

Over to You

In the manifesto, the driver is to connect different ways of knowing, bridging these in a way not dissimilar to the transdisciplinary manifesto written by Pamela Burnard (Chapter 7). How do we know what we know? How do we come to know? Is there a hierarchy of knowledge? Or of ways of knowing? For example it is common for teachers in the UK to talk of the science of learning – and yet science develops and evolves, so what we know now about cognitive load theory, for example, may be a thing of the past in the future! A number of ideas and questions arise, which we share for the reader to consider:

If you haven’t been persuaded about the power of incorporating philosophy into the curriculum, can I offer a final thought: why not take just one half term this year to experiment with some of these ideas? Come up with a plan for your own classroom, and watch and see what happens. What have you got to lose?

Begin by looking at your school curriculum and, for each subject area, consider your units of learning.

Can you discuss what really matters in learning? What are the big themes in life? Can an overarching theme be identified (e.g. love, loss, power, friendship, journeys)? If so, try using the first lesson in that unit as a philosophy lesson. Next, find an engaging stimulus. It should relate to your theme in some way and ought to be thought-provoking and interesting enough to generate class discussion. The Philosophy Foundation (2024) provides an array of excellent stimuli for nursery to secondary school, with links across the curriculum. Once the theme has been identified and the stimulus found, you can simply follow the ten-step P4C structure within your lessons. Children quickly get used to the structure and move through each part of the enquiry with ease. Including philosophy like this as a launch pad into units of learning is an easy and effective way to weave philosophical discussion into the fabric of your curriculum.

How do you create space for dialogue? Creating space for philosophical discussion in the classroom needs intention and thought, but it does not need to be onerous or time intensive. By carving out short pockets of time, we hold a much-needed space for our children to grapple with the big questions in life. We do this in a safe, open forum, developing and deepening the themes that are already being explored in science, RE and other areas of the curriculum. In doing so, we nurture thoughtful, compassionate and ethically aware individuals. We build their confidence, allowing them to explore, critique and defend different perspectives. We empower them to think deeply, ask questions, use critical reasoning and stay open-hearted – vital skills that will serve to enrich them and the world around them, both now and in the years to come.