“We don’t think of ourselves as a secessionist movement. We see ourselves as a self-determination movement….The political tension does not come because Portland’s doing something. The political tension comes when Portland does something and says we have to do the same thing. It doesn’t work for us.”

Matt McCaw, Greater Idaho movement activist

“We are very different people….The rules and regulations that they’re making, that makes sense in the city, don’t make sense out here. The people here haven’t changed. Portland’s changed. Salem’s changed. Eugene has changed.”

Sandie Gilson, Greater Idaho movement board member Footnote 1

Scholars have long examined secessionist and irredentist movements in Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe, and South Asia but rarely in the United States. Nonetheless, the United States has a storied history of separatism, beginning with the secession of 11 states that led to the American Civil War, as well as more contemporary cases of independence movements in Alaska, California, and Texas. There also have been smaller movements such as the libertarian Free State Project in New Hampshire and the rural Pacific State of Jefferson.

As of April 2025, 13 Oregon counties have passed advisory ballot measures to break off from the liberal state of Oregon to join the conservative state of Idaho. This so-called Greater Idaho movement is animated by the fact that Republicans have become a permanent political minority east of the Cascade Mountains. Excluded from state politics, the state Republican Party has affiliated increasingly with right-wing militia groups such as the Oath Keepers, the Three Percenters, and the Sovereign Citizens Movement. In 2020, a group calling itself “Move Oregon’s Border for a Greater Idaho” began to lobby on several fronts to leave Oregon and join Idaho, where the Republican Party has long dominated state politics. If it achieves its goal, more than 12 counties in Eastern and Southern Oregon would be annexed by Idaho. These events have attracted relatively little attention in the national press due to their low probability of success. Interstate border adjustments require the assent of affected state assemblies as well as the US Congress; these adjustments are regulated by the Admissions Clause of the United States Constitution in Article 4, Section 3, Clause 1. Historically, however, separatist movements rarely have been deterred by the infeasibility or illegality of their aims. This means that we ignore them at our peril.

The Greater Idaho movement may be understood as a separatist movement. “Separatism,” as defined by Horowitz (Reference Horowitz1981, 168), is any collective movement that seeks to achieve greater territorial independence from the state center. This broad definition serves as an umbrella concept encompassing more moderate autonomy movements as well as more extreme forms, such as secessionism and irredentism.

“Secessionism” is a subset of separatism that involves breaking off territory from an existing state to form a new independent state. “Irredentism” refers to a movement by one state to separate and reclaim territory from another state, usually on ethnic grounds (Kornprobst Reference Kornprobst2008, 9; Siroky and Hale Reference Siroky and Hale2017, 117). The Greater Idaho movement represents a case of intrastate separatism rather than a full secessionist or a traditional irredentist movement. Unlike secessionist movements in Scotland, Quebec, and Catalonia that aim to create independent sovereign states or the irredentist campaigns to separate Crimea from Ukraine and attach it to Russia or separate Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and join it to the Republic of Ireland, the Greater Idaho movement seeks to change an internal federal border within the United States. If successful, the counties involved would exit Oregon and join Idaho while remaining part of the sovereign United States. Therefore, the Greater Idaho movement bears more similarity to cases of separatist border changes, such as the formation of West Virginia during the Civil War, the Jura question in Switzerland (Siroky, Mueller, and Hechter Reference Siroky, Mueller and Hechter2017), and the campaign to separate the Nagorno–Karabakh region from the Azerbaijan Republic and join the Armenian Republic in the late 1980s Soviet Union. Visualized as a Venn diagram, secessionism, irredentism, and internal border changes such as the Greater Idaho movement are all subsets of separatism. Although these terms are contested and defined differently by various scholars (Pavković Reference Pavković, Kingsbury and Laoutides2015), we find that this conceptualization most accurately matches the features of this case.

Whereas the Greater Idaho movement differs from secessionist and irredentist campaigns to alter international borders, we argue that theories developed to explain such movements provide valuable insight into the motivation behind all forms of territorial separation. Our study therefore applies theories from the broader literature on separatism to the case of the Greater Idaho movement. These theories are relevant to the movement because they all seek to explain the impulse for territorial separation, which are features of secessionist, irredentist, and internal border change movements alike. Our goal is to illuminate the attitudinal motivations propelling Eastern Oregonians to support separation from Western Oregon, despite the fact that the ultimate goal is merely an interstate border adjustment rather than sovereign independence.

Whereas the Greater Idaho movement differs from secessionist and irredentist campaigns to alter international borders, we argue that theories developed to explain such movements provide valuable insight into the motivations behind all forms of territorial separation.

It is practically a truism that separatist movements are driven by ethnic differences—whether religious, cultural, racial, or linguistic. In these movements, ethnic minorities mobilize to separate from the majority-controlled political institutions. Because the United States was founded on a civic rather than an ethnic identity, it has long been presumed to be inoculated against such movements. The only serious case of separatism in US history was sectoral: pitting the Southern Confederate States of America against the Union states in the nineteenth-century American Civil War. However, this presumption may be oversimplified. Although we classify the Greater Idaho movement as primarily political rather than ethnic separatism, we acknowledge that the distinction between these categories is not always clearcut because political movements about territorial control may develop ethnic dimensions over time.

In recent years, the United States has witnessed evolving dynamics of political division and regionalism. There has been increasing discussion of civil war due to ideological polarization (Walter Reference Walter2023). However, relatively little attention has been given to the threat of territorial separatism, although some have warned of this possibility (Anderson Reference Anderson2004; Buckley Reference Buckley2020). Regular Americans, however, have been separating with their feet. In the past two decades, there is evidence of increasing territorial segregation in the United States: Republicans are moving to “red” states and Democrats are moving to “blue” states (Brown and Enos Reference Brown and Enos2021). These partisan migrants claim that they are moving to join their co-partisans in states where “their” party dominates local politics. This dynamic has been creating permanent political majorities at the state level, with significant political knock-on effects. Predominantly Democratic states have enacted laws legalizing marijuana, protecting gay and transgender rights, and creating robust environmental and labor protections. Republican states have passed highly restrictive abortion laws, tough-on-crime laws, and highly permissive gun legislation. The result is a growing political divide between red and blue states, further incentivizing people to migrate to politically friendly states in a feedback loop.

To conduct our investigation, we administered a survey to residents of the separatist counties in Eastern Oregon. The survey questions were based on traditional theories of secessionism and irredentism. We administered our survey in September 2023 to people in the 17 Eastern Oregon counties that feasibly could separate from Oregon to join Idaho.

WHY SEPARATE?

We drew on classical theories of separatism to test for the drivers of popular support for the Greater Idaho movement in Eastern Oregon. Several scholars have made valuable contributions to the literature on separatism, examining various aspects including structural conditions (Sorens Reference Sorens2005); violence and conflict dynamics (Cunningham Reference Cunningham2013; Cunningham and Sawyer Reference Cunningham and Sawyer2017; Griffiths Reference Griffiths2016; Griffiths and Wasser Reference Griffiths and Wasser2019); international factors (Fazal and Griffiths Reference Fazal and Griffiths2014); bargaining dynamics (Cetinyan Reference Cetinyan2002; Jenne Reference Jenne2007; Jenne, Saideman, and Lowe Reference Jenne, Saideman and Lowe2007); and ethnic polarization (Balcells and Kuo Reference Balcells and Kuo2023). Whereas these studies provide important insight into the macro-level dynamics of separatist movements, our focus in this article aligns more closely with research that examines individual-level motivations for supporting separatism (e.g., Blais and Nadeau Reference Blais and Nadeau1992; Hierro and Queralt Reference Hierro and Queralt2021; Muro and Vlaskamp Reference Muro and Vlaskamp2016). However, these individual-level studies predominantly focused on regions with distinctive ethnic or linguistic identities. In contrast, scholarship that focuses specifically on individual-level separatist attitudes in regions that lack distinctive group identities, as in the case of Eastern Oregon, is less common. Therefore, our study constitutes a plausibility probe into whether classical theories of separatism can illuminate the drivers of popular support for the Greater Idaho movement. To develop our survey questions, we distilled each theory into its psychological components. We then adapted these theories to the specifics of this case. The psychological drivers underlying these theories are divided into identity, fears, and economic variants.

Identity Theories

Identity theories hold that significant ethnic differences between the majority and minority motivate support for political independence. To apply this logic to the Greater Idaho movement, we first operationalized regional identification as the conscious belief among residents of Eastern Oregon that they possess a distinct culture setting them apart from the rest of Oregon. Second, we measured “entitativity,” which is the degree to which respondents perceive the state as a unified whole (Campbell Reference Campbell1958). To test for this, we asked the survey respondents whether Oregon has a cohesive identity. Third, in-group bias may be associated with political separatism. Macauley (Reference Macauley2019) found that in-group linguistic favoritism in Quebec correlated positively with support for secession. To capture positive exceptionalism in our survey, we asked respondents if they view their region as superior to other parts of Oregon. Fourth, studies have shown that people want to separate from the majority when they believe it is subverting their identity (Sani and Reicher Reference Sani and Reicher1999; Sani and Todman Reference Sani and Todman2002). Separatism also may be correlated with the belief that the state’s dominant norms and practices are antithetical to those of the minority. To test for this, we asked respondents whether the values and shared norms of the state of Oregon no longer correspond to their identity, specifically because Oregon’s current identity deviates from its original identity. Fifth, separatism may be driven by the belief that members of a minority cannot properly voice disagreements, grievances, and divergent opinions within the political system. Sani (Reference Sani2005) found that those who believe they can voice dissent are less inclined to seek exit. Conversely, those who perceive that they are denied a voice are more likely to desire political independence. This aligns with the Remedial Right Only justification for secession, the theory that secession is a legitimate option only when a group has been subjected to serious injustices by the state from which it seeks to separate (Buchanan Reference Buchanan1997). To test for this, we asked respondents whether their voices are marginalized in Oregon state politics.

Fears Theories

The second set of separatist theories relates to group insecurity—specifically, fears of domination, persecution, or assimilation by the ethnic majority. Fears-based theories of secession hold that individuals support political exit if they perceive significant threats to the group’s autonomy, identity, physical safety, or way of life. They also may favor separation if they believe that they cannot properly protect the region from internal or external dangers (Birch Reference Birch1984). Sudden changes or long-term shifts in political dynamics within a state can cause particular groups and regions to reevaluate whether they can continue to thrive in the existing state framework (Levy Reference Levy1997; Posen Reference Posen1993; Weingast Reference Weingast, Haufler, Soltan and Uslaner1998). To test whether threat perceptions motivate support for the Greater Idaho movement, we asked residents whether they fear Oregon state authorities—specifically, whether they believe that the state poses dangers to their cultural and physical well-being.

A second fears-based driver for separatism is the perception of oppression, inequality, discrimination, disrespect, and prejudice. In Quebec, a sense of unequal treatment and disrespect by Anglophones against Francophones played a role in galvanizing support for Francophone separatism (Mendelsohn Reference Mendelsohn2003; Pinard and Hamilton Reference Pinard and Hamilton1986; Yale and Durand Reference Yale and Durand2011). To capture these sentiments in the Eastern Oregon survey, we asked respondents to evaluate the quality of intergroup relations between themselves and Western Oregonians.

Economic Theories

The third set of theories relates to economic motives for separatism. Economic motivations typically are categorized as either rich-region (“greed”) or poor-region (“need”) separatism (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Howe Reference Howe1998). The “need” logic pertains more to economically disadvantaged groups that view themselves as victims of discriminatory policies. This means that separatism is driven by perceived economic neglect or exploitation by the state. By contrast, the “greed” logic pertains more to economically successful groups whose members believe that they are subsidizing poorer parts of the state, which represents a drain on regional resources. Either way, economic grievances are rooted in the belief that the group’s economic interests are better served outside of the existing state framework. We tested for both economic motives by asking Eastern Oregonian respondents about their perceived economic exploitation by the rest of the state and whether they believe that the state government protects their economic interests.

DATA AND METHODS

The Greater Idaho movement aims to fully detach 13 Eastern Oregon counties and partially detach another four counties from Oregon and join them to Idaho by moving the Oregon–Idaho border westward. The 17 surveyed counties have a combined population of 413,223 adult residents. To ensure external validity, our survey respondents included only voting-age US citizens who were residents of those counties (Dzebo, Jenne, and Littvay Reference Dzebo, Jenne and Littvay2025).

We contracted with Cint—a digital sample-management platform that maintains a large panel of potential US survey participants—to obtain an adequate sample size for our online survey of the 17 counties. Cint adheres to rigorous industry standards for data quality control and fraud detection. Between July 27 and September 14, 2023, it recruited almost 300 respondents from the region (of which 193 were included in our analysis).Footnote 2 Respondents were told that the study was intended to investigate “public opinion about current issues.”

Power analysis for bivariate correlations shows that our sample size (N=193) is adequate for yielding significant results for an effect size of r=0.2 (4% of the variance explained), with 95% confidence in a two-tailed test, 80% of the time. Therefore, we have the traditionally used 80% power to find 95%-significant results for any relationship with a reasonable effect size of r=0.2.

We measured our dependent variable of support for the Greater Idaho movement using the following question: “If offered the chance, how likely are you to vote for Eastern Oregon to leave Oregon and join Idaho?” Response options were presented on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “very unlikely” to “very likely.”

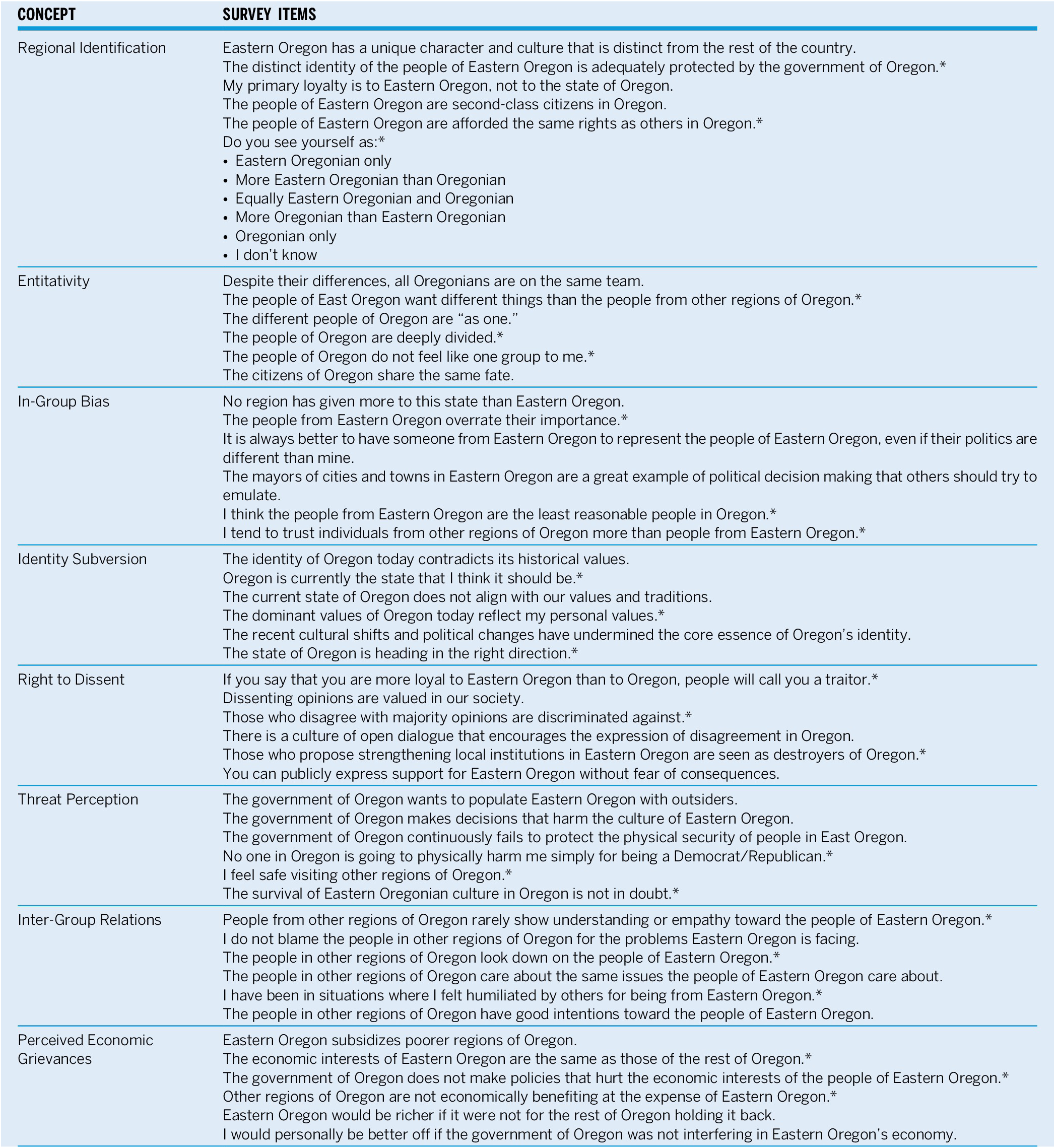

We measured the key motivations for separatism (i.e., our independent variables or predictors) using eight constructs, each assessed by six survey items. All items used a five-category agree/disagree Likert scale, with the exception of the Linz-Moreno question (ID6r). Half of the items were reverse-coded. Table 1 contains the full list of survey items used to measure each concept.Footnote 3 We averaged the responses for each construct and rescaled them to range from 0 to 1. In our sample, 39 cases (20.2%) had one response of the 48 motivational-factor items that was coded as NA (not available), and one case (0.5%) had two NA responses from different factors. Notably, 30 of these 40 cases were for the Linz-Moreno question, which asked respondents to self-identify on an Eastern Oregonian–Oregonian spectrum. For this particular question, we included the “I don’t know” option, which typically is included due to the potential complexity of regional identity.Footnote 4 All 30 of these cases selected the “I don’t know” option rather than leaving the question unanswered. To ensure that respondents were not excluded for incidental missing data, we averaged all available responses for each construct. This meant that each measure represents the mean of at least five items, even in cases with NA responses.

Table 1 Survey Items for Each Concept

Note: *Indicates reverse-coded items.

We also controlled for age, gender, education, income, race, partisanship, and whether a respondent resides in one of the four partial-secession counties. For independents and third-party supporters, follow-up questions were used to gauge partisan leanings. All predictors were rescaled from 0 to 1. We did not include controls for ethnicity or religiosity because church attendance is relatively low throughout Oregon and the state is racially predominantly white (Newport Reference Newport2015; US Census Bureau 2023). Therefore, there was little reason to believe that support for Greater Idaho in Eastern Oregon was motivated by either religious or racial differences between the East and the West. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics.

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics of Regression Variables

Note: Predictors are scaled 0–1. Outcome (Separatism) is coded 1–5; higher numbers indicate greater support for joining Idaho.

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

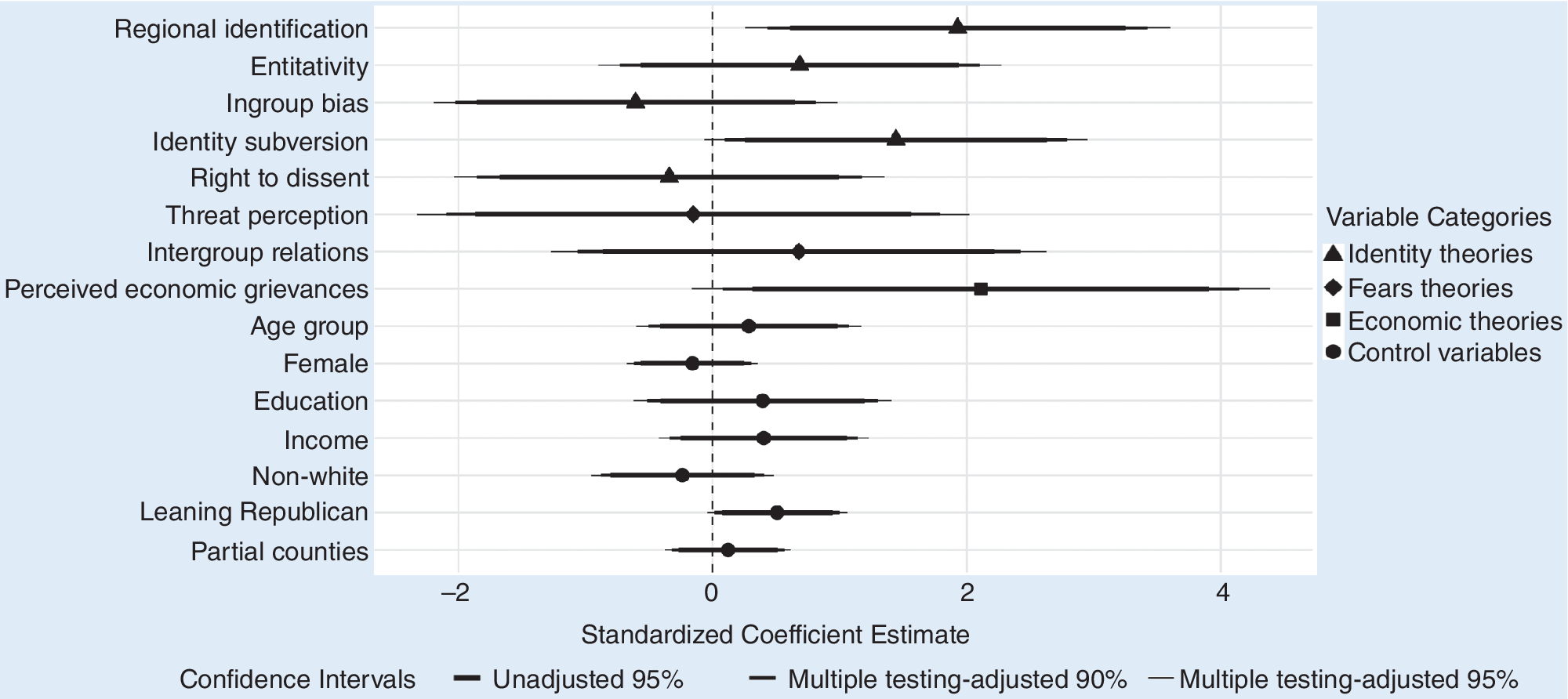

Our regression analysis identified the key drivers of separatist preferences in Eastern Oregon.Footnote 5 Economic grievances emerged as the strongest predictor of separatism (β=2.11, BH p=0.083, Storey’s q=0.025),Footnote 6 which suggests that perceptions of economic exploitation are critical drivers of support for the Greater Idaho movement. Identity-based factors constituted the second-most significant predictors, with both regional identification (β=1.93, BH p=0.067, Storey’s q=0.020) and perceived identity subversion (β=1.44, BH p=0.083, Storey’s q=0.024) showing substantial effects. The strong regional-identification coefficient reflected the importance of a distinct and uniquely Eastern Oregonian identity, and the identity-subversion effect indicated that supporters of the movement believe that Oregon no longer stands for what it used to stand for. Among the control variables, Republican partisan identity was a moderate predictor for redrawing state borders, even after controlling for identity, fears, and economic concerns (β=0.51, BH p=0.083, Storey’s q=0.025).

The results are illustrated in figure 1, which presents both unadjusted (95%) confidence intervals and false coverage rate adjusted intervals (90% and 95%), following the Benjamini and Yekutieli procedure (Reference Benjamini and Yekutieli2005, 73). The multiple testing-correction procedures did not lead to substantively different conclusions from uncorrected results; however, in some cases, the confidence levels dropped to 90%.Footnote 7

Figure 1 Predictors of Separatism in Eastern Oregon

All predictors are standardized to range [0,1]; N=193.

In summary, identity and economic theories of separatism best explain popular support for political separatism in Eastern Oregon. Economic motivations exerted the highest impact, highlighting the importance of perceptions of economic exploitation in driving support for the Greater Idaho movement. Economic discontent also may reflect a broader urban–rural divide, as Eastern Oregonian interests are believed to be subverted to the interests of residents in Western urban centers. This conforms to Horowitz’s (Reference Horowitz1981) “backward region” theory of separatism as well as the ethnographic findings of Cramer (Reference Cramer2016), who studied political consciousness in rural Wisconsin towns in the early 2010s. With growing national polarization tied to place-based identities, we believe that so-called left-behind rural grievances may ignite similar political separatist movements elsewhere in the country.

Support for the Greater Idaho movement also appears to be rooted in regional identification. Our results demonstrate that backers of the movement view themselves as culturally distinct from Western Oregonians and that they believe state policies do not align with their values. This misalignment appears to have produced a yearning for belonging to a state where conservatives comprise the political majority and therefore can exercise control over legislative and executive institutions. This makes separatism an attractive option for them. Our results indicate that political renegotiation, regional recognition, and mutual respect for values are critical to effective governance of diverse populations. If Greater Idaho supporters believe that Oregon has deviated fundamentally from its original character, this could make political exit more attractive. When groups feel abandoned by the political unit, destructive bids at reaffiliation can emerge if grievances remain unreconciled. Although the partisan findings of our study confirm the links between partisanship and political separatism, economic motivations appear to matter more. This calls into question reductionist narratives that exclusively frame the Greater Idaho movement through a partisan lens. More than “culture wars” or negative partisanship (Abramowitz and McCoy Reference Abramowitz and McCoy2019), our study suggests that separatism in the Pacific Northwest may be driven more by the desire to improve the region’s economic status.

Although the partisan findings of our study confirm the links between partisanship and political separatism, economic motivations appear to matter more.

The most interesting finding of our survey was the limited role of fears in support for the Greater Idaho movement. Eastern Oregonian separatists apparently are not concerned about repression or survival and neither are they motivated by hostility toward the more liberal Westerners—which is contrary to the partisanship hypothesis. Indeed, the insignificance of intergroup animus demonstrates that political separatism in this case is not driven primarily by hostility toward Democrats. Similarly, whereas supporters believe that their voices lack influence, the suppression of dissent non-finding indicates that most Eastern Oregonians believe that they can campaign openly for separatism.

CONCLUSION

Although our study is demographically representative, our findings are based on a relatively small sample.Footnote 8 Further ethnographic research in the region should be used to validate our results and develop a more in-depth understanding of popular support for the Greater Idaho movement.

Overall, the movement seems to have more “pull” than “push” factors. Its supporters appear to believe that joining Idaho would be economically beneficial to them while also affirming their conservative identities. In other words, they are not driven primarily by antagonism toward liberal Oregonians. Together, these results suggest that the Greater Idaho movement is concerned mostly with a crisis of representation in the Eastern half of the state, where conservatives are in the permanent political minority (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2020). What does this mean for policy? We think it suggests that if permanent political minorities, similar to ethnic minorities, are offered a legislative buy-in, they may be less likely to suffer the alienating effects of their minority status. A consociational model, which ensures representation for distinct groups within a shared governance structure, potentially could address these concerns without resorting to territorial separation. Although the Greater Idaho movement currently may not pose a serious threat of instability—much less collective violence—history reminds us that separatist movements should not be ignored. Separatist impulses often are tied to right-wing populism, which emerges in the wake of demographic change and other representational crises (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2017). In these settings, destructive bids for separation may emerge. Responsible policy makers must give voice to self-determination claims within existing institutions to transform zero-sum mentalities into a positive-sum proposition in the state as a whole.

Together, these results suggest that the Greater Idaho movement is concerned mostly with a crisis of representation in the Eastern half of the state, where conservatives are in the permanent minority.

Finally, the results of this study suggest that classical secessionist theories provide insights into the drivers of political separatism. Our findings reveal that economic and identity drivers may be more important than fears and animosities to account for support for the Greater Idaho movement. Although this is only a preliminary study, our approach provides a valuable framework for examining more broadly the drivers of territorial separation. The psychometric investigation used in this study enables more direct testing of competing theories of separatist attitudes through systematic measurement of individual-level motivations. This includes not only cases of secessionism but also irredentism within federal systems and other political contexts worldwide. In short, our study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the varied forms of territorial separation and highlights the need for further research to fully explore the distinctions among different types of separatist movements.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096525000290.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the editor and four anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback and constructive suggestions that improved this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LH6ZIN.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.