“That’s advice, horrible advice!” Asher responded to Mimi who was a member of his training program. Mimi was a call center employee from Manipur, India. She was training to become a trainer, and at this moment, was in the middle of an activity where she was supposed to learn about creating empathy statements. Asher was a master trainer with over a decade and a half of experience in the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry in India. He was the co-owner of One Direction Skill Solutions (ODSS) and ran a Train the Trainer (TTT) program for aspiring call center trainers. Mimi had been given a situation with which to verbally empathize—somebody losing their dog. She was supposed to craft a statement to respond to the situation according to the lessons we had been learning that day. She provided the statement, “well, I’m sure you must have reached out to the police,” which prompted Asher’s beratement that this was not “empathy,” but “advice.”

Emotions do not travel freely between people, across contexts in affective flows. In call centers, talking about emotions is rigorously trained using semiotic frameworks that make emotive statements intelligible and more importantly effective upon foreign customers. Empathy statements show the performative nature of translation in the global workplace. They serve to make the emotional intent of the Indian agent intelligible to the foreign customer, and through learning empathy statements, Indian call center workers learn to interpret expressions of emotion exhibited by customers. On another level, empathy statements also serve as a means through which the customer service agent can restate the customer’s feelings in a “milder,” more ideologically “neutral” form as a way of mitigating the expression of those feelings during a call.

My analysis of the translation of empathy shows the vast amount of semiotic labor that goes into creating emotional and affective effects in the global service industry. Drawing from 18 months of participant observation in the skills training industry in New Delhi, I trace this labor by analyzing the process through which soft skills trainers learn to train agents in empathy statements. In this article, I use meta-discursive behavior typifying empathy statements in call center scripts during the training of “soft skills” trainers to establish the grammatical form of these statements. The form of empathy statements, and the means through which emotions are translated, is enregistered (Agha Reference Agha2005) through rigorous training programs.

This analysis of empathy statements builds off of theories of the incomplete and yet generative nature of translation in the context of post-colonial English, or the “aporia of translation” (Rafael Reference Rafael2016). This is a process of friction (Tsing Reference Tsing2011), and it generates new forms of value and meaning in its wake that take the form of semiotic frameworks. The translation of emotion through these statements is at once a cite of inequality and a cite of resistance as callers use the tools of Western emotional expression to quell unwanted outbursts of anger from irate customers. By stating feelings in the right way, the feelings themselves undergo a translation process that is meant to effectively neutralize or moderate what the client is expressing. These statements are used in customer service interactions in a wide range of fields all over the world creating a translation that is performative rather than complete.

Background

Translating soft skills, affect, and empathy

“Soft skills” is not a term that was familiar to the trainees. The terms of training were rarely translated into local languages, but rather translated in different registers of English. An exception was when Asher introduced trainees to the Soft Skills training module; he wrote on the whiteboard the Hindi words मुलायम कलाएँ (mulaayam kalaaye), or “soft arts,” to the confusion of the trainees. The term makes little sense in Hindi. The fact that there is no easy translation of the noun phrase “soft skills” in Hindi and the literal translation of these words was meant to be humorous and elicited confusion from the group, was an allegory for the way that the types of behavior that were covered in soft skills training were often at odds to the intuitive ways that the trainees would normally engage with each other and talk about emotion in an Indian context. The work of translation required hours and hours of practice and technical theories about other nouns, like “empathy.” Engaging in talk about feeling in this way was far from natural in this context; it was a skill to be acquired. The commensuration of empathy required semiotic frameworks that could render words like skill and kalaaye translatable, expanding the semiotic domain of soft skills for the trainees.

The data from this paper come from a soft skills training module that I observed from 2018 to 2019. My field site, ODSS, was a company that worked with the BPOs in the National Capital Region of India to supply them with labor and training. By working with ODSS, I was able to observe their work with multiple BPOs and hundreds of workers and potential workers over the course of my 18 months of ethnographic fieldwork that lasted from 2016 to 2019. For this paper, I will be focusing on the portion of my research that involved participating in and observing a program for training call center trainers called Train the Trainer Training (TTT). I observed the training of two batches of future BPO trainers which met once a day for 6 hours every week. I collected over 70 hours of audio and video recordings of these training sessions. Upon certification, the new trainers would go on to work at call centers training new employees to work at BPOs.

Empathy statements belong to a type of training, called “soft skills training.” “Soft skill” is a nebulous category that Asher distinguished from “hard skill” in that soft skills are formulated as not the overt task that a worker does to earn their wage. Rather, “soft skills” often refer to the unwritten rules of interpersonal conduct that overlay every social interaction in which a worker engages. “Soft skill” often describes the general “niceness” or “politeness” of a person’s behavior, and it ideally results in similarly “pleasant” responses in the next turn behavior of a customer. The rise of this kind of emotive or affective aspect of workplace activities is central to the work of BPO workers, as it is for many people in workplaces across the globe (Mankekar and Gupta Reference Mankekar and Gupta2016).

“Soft skills,” according to Asher, were about interacting with customers “professionally and politely.” Throughout this training module, trainees were expected to learn how to build rapport, actively listen, give a polite refusal, and apologize, such that American customers would respond positively to their mannerisms and give employees good customer satisfaction scores. Despite their juxtaposition to “hard” skills, not only were soft skills deceptively tricky, but I observed through this training that “soft skills” were explicitly laid out, formulated, and constituted a central part of call center work. Rather than unwritten rules that are less central than “hard skills,” these rules were explicit and treated as just as important as other aspects of call center routines. Ironically, soft skills were hard on both of these levels: they were not easy to obtain, and they were a central part of how employee labor was commodified in call centers.

The types of things associated with soft skills, navigating emotional situations, being perceived as “nice,” making customers “feel things,” are one reason why scholars such as Mankekar and Gupta (Reference Mankekar and Gupta2016) argue that call center customer service work is “affective labor” with the call center floor being a space characterized by a kind of “raw energy” (15). Drawing from Massumi (Reference Massumi1995), they discuss how affect is pre-internalized emotion, and it is intersubjective rather than internal:

In contrast, in our characterization of the labor of call center agents as affective labor, we theorize affect as a field of intensities that circulates between bodies and objects and between and across bodies; as existing alongside, barely beneath, and in excess of cognition; and as transgressing binaries of mind versus body, and private feeling versus collective sentiment. (Mankekar and Gupta Reference Mankekar and Gupta2016, 24)

Empathy is often spoken about as something that is felt with others, rather than on one’s own. Empathy is talked about as something outside of and in excess to language and cognition. This builds off an understanding of language developed by Deleuze and Guattrari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1980) where language exists separate from raw experience in a plane of reference. Scholars who study affect often look to exceed or get beyond representation (Stewart Reference Stewart2007; Tomkins Reference Tomkins2008; Melissa and Seigworth Reference Melissa and Seigworth2010). However, empathy in call centers is inextricably embedded in learning linguistic expressions.

Empathy requires translation in that the feelings of at least two people are held to be tokens of the same type. Empathy has a relatively recent translative history. The word “empathy” itself entered the English language as a translation from the German einfühlung [in-feeling] in 1909, by American Psychologist Edward Titchener from the work of German Psychologist Theodor Lipps (Jahoda Reference Jahoda2005; Cuff et al. Reference Cuff, Brown, Taylor and Howat2016). The German term was adapted, defined, and cast into a trajectory in American psychology that eventually led to its being the center of the discussion between Asher and his trainees.

According to Asher, “empathy” is differentiated from sympathy in the fact that it is situation- and solution-oriented rather than simply mirroring feelings. This definition aligns with how professional registers of empathy are talked about in marketing and medical literature. Solution-driven empathy statements are widely popular in the United States and have been developed for training in American medicine, where doctors continue to use them to deliver bad news to patients, but in recent decades they have come to be used widely in a range of service industries, including the Indian call center (Coulehan et al. Reference Coulehan, Platt, Egener, Frankel, Lin, Lown and Salazar2001; Hardee Reference Hardee2003). Empathy statements are often used and studied for the purpose of customer interactions (e.g., Coulehan et al. Reference Coulehan, Platt, Egener, Frankel, Lin, Lown and Salazar2001; Silvia De et al. Reference Silvia De, Borrè, Marchiori, Cantoni, Tussyadiah and Inversini2015; Packard, Moore, and McFerran Reference Grant, Moore and McFerran2018; Van Herck et al. Reference Van Herck, Decock, De Clerck and Hudders2023). Through codified “empathy statements” doctors and call center workers, alike, attempt to make patients and clients feel understood and cared for, or, at the very least, respond as if they feel cared for. This definition of “empathy” might seem strange to the reader who isn’t already familiar with this type of professionalized empathy.Footnote 1 Through the global workplace, this kind of efficient, solution-driven approach to feelings has spread the world over.

BPOs, ODSS, translation, and new capitalism

International call centers have emerged as workplaces under what scholars have called “globalization,” “global capitalism,” “neoliberalism,” “transnationalism,” or “globalism.” Business processes exist across nation-boundaries. The nature of work is changing and this is reflected in scholarship that highlights the parallel changes in how we talk in and about the workplace. Under global capitalism, language has become both a commodity itself (Heller Reference Heller2010) and is the means through which commodities are formulated (Agha Reference Agha2011a). Urciuoli (Reference Urciuoli2008) talks about how “skills talk” reduces workers to bundles of cultural shifters that market CV writers as the “right kind of person” without being grounded semantically. The alienation of language from meaning is central to work in “McJobs” (Ritzer Reference Ritzer2013) or “bullshit jobs” (Graeber Reference Graeber2018) that utilize “bullshit genres” (Gershon Reference Gershon2023). Within this kind of workplace, emotional labor, or labor characterized by the commodification of emotion, has emerged as a central part of most customer-facing industries (Hochschild Reference Hochschild2012), and soft skills is a codification of this kind of labor.

BPO companies have become a common business model since the expansion of the internet and telecommunications in the 1980s and arrived in India in the 1990s after the opening of the Indian economy to foreign investors in 1991. The BPO business model is premised on a third-party company taking on some aspect of another company’s business (also known as a “process”) in order to cut costs for the other company. This often happens across national borders to take advantage of the lower cost of labor in former colonies. In India, the international call center has become somewhat of a poster child for the BPO industry, where multinational companies hire BPOs to handle everything from insurance claims to debt collection. Research on BPOs in India have focused on accent training (Friginal Reference Friginal2007; Rahman Reference Rahman2009; Krishnamurthy Reference Krishnamurthy and Kothari2011; Mirchandani Reference Mirchandani2012; Aneesh Reference Aneesh2015), broader societal impacts (Patel Reference Patel2010; Shelly and Vigneswara Ilavarasan Reference Shelly and Vigneswara Ilavarasan2011), and the emergence of a class of global professionals (Noronha and D’Cruz Reference Noronha and D’Cruz2009; Nadeem Reference Nadeem2013; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2022).

The training received in call centers is a form of translation in that norms of language intelligible and suitable for the customer must be learned and equated to the norms of new trainees. Asher often said that as trainers you “start with what they [the Indian trainees] know and bring them to what they don’t know.” During TTT, the trainees needed to not only learn how people in the United States and England used language, but they had to learn how to get their own future trainees to take on manners of speech that would be intelligible to future foreign customers. This ranged from speech sounds to the subject of this paper: talk about emotion.

Leidner (1993) calls these kinds of training the “routinization” of service work, where in neoliberal workplaces nearly all conduct has become scripted and highly trained. Routinization, however, is not routine. Woydack’s ethnography of a multilingual call center shows how scripts are socially negotiated by employees and not top-down constructions (Woydack and Rampton Reference Woydack and Rampton2016; Woydack and Lockwood Reference Woydack and Lockwood2017; Woydack Reference Woydack2019). Further, what discussion of training as simply the dispersion of neoliberal scripts misses, is the work of translation that goes into this kind of training. Translation is a generative process that creates new forms of meaning as multiple forms (each with their own context) are equated. Tsing (Reference Tsing2011) calls this process of local interpretation and the generative-ness of globalization “friction.” Under global capitalism, treating processes as scalable and interchangeable is a part of what Tsing (Reference Tsing2015) calls scalability.

These points of international contact require translation. Translation involves an irony that leads to the generation of linguistic frameworks towards the impossible goal of rendering two things interchangeable, an impossible task. Rafael argues for an “aporia of translation” in that the work of translation is never complete, creating a generative effect (Rafael Reference Rafael2016). The incompleteness of the translation of call center language has led to new forms and formulations for the use of language in call centers, from “neutral” accents to scripts riddled with empathy statements. The incompleteness of translation comes from the fact that no two signs are completely interchangeable, rather translation involves semiotic frameworks that render them gradable, commensurate (Carruthers Reference Carruthers2017), and, therefore, comparable.

Making customer service workers intelligible to foreign customers involves creating and utilizing semiotic frameworks that allow for different registers of speech to be compared in a meaningful way. Translation involves processes of enregisterment where registers of interpersonal communication are emblematically associated with formulations of personhood (Agha Reference Agha2005). Translation expands the social domain of registers while also changing their context of interpretation. The remainder of this paper shows the semiotic work and semiotic frameworks that go into rendering two formulations of emotion comparable and therefore translatable.

Grammar of empathy

The grammatical form of empathy statements, while perhaps not explicitly known to most Americans, is a highly recognizable form of speech. “I understand that having a broken computer must be exhausting to deal with for you.” “I can see that you are excited to be celebrating your new job.” “I can tell that being locked out of your account would be frustrating for you.” The form is recognizable and either associated with customer service or couples’ therapy.

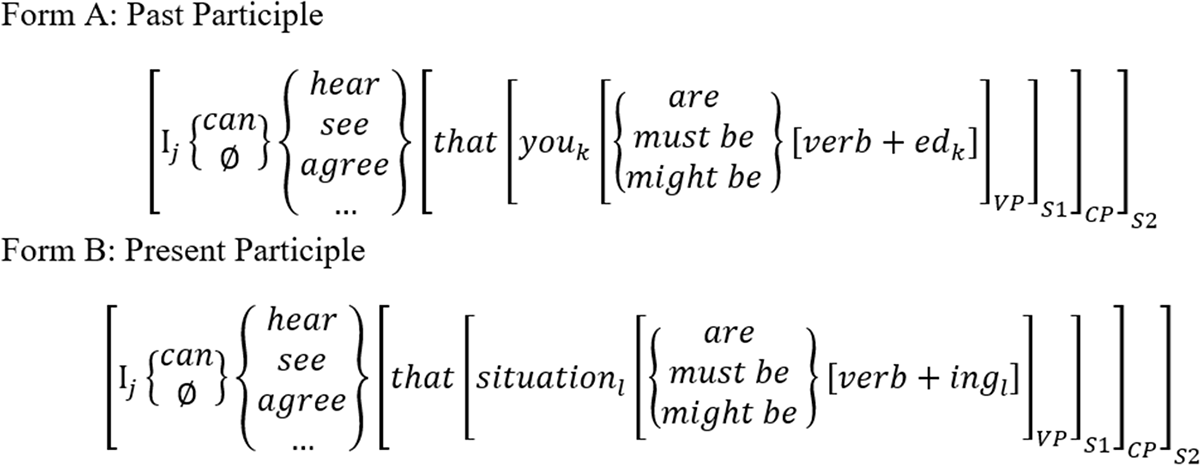

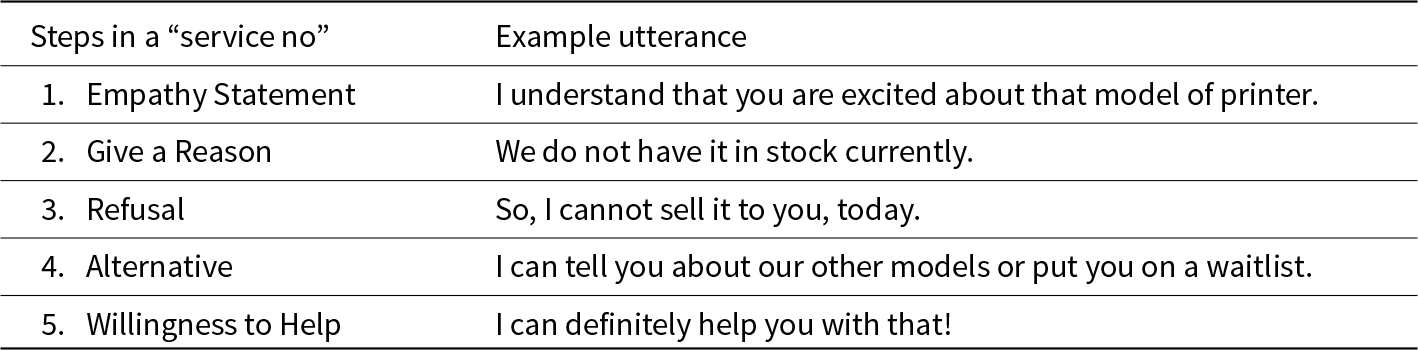

Empathy statements take a regular grammatical form. Asher identified this form in three to four parts, summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Grammatical form of empathy statements.

Empathy statements start with an “I” statement and verbum sentiendi, “a verb of perception,” like “understand” or “see,” or a verbum decendi, “a verb of speech,” such as “agree” or “tell.” These verbs are sometimes accompanied by a modal verb such as “can,” “may,” or “will.” This phrase is followed by a past or present participle adjective which is an adjective formed from another verbum sentiendi by the affixing of a -ed or -ing affix. Then, there is a reference to the speaker and often some kind of hedging phrase. An example would be “I understand that you are frustrated” or “I understand that the situation might be frustrating for you.”

This grammatical Form A from Figure 1 includes both first- and second-person pronouns, which are deictics that cement participant roles in the empathy statement. In the grammatical form B, the subject of S1 is a situation. This could be the description of a situation or simply the phrase “this situation.” Often the verb phrase in Form B has a prepositional phrase “for you” as its compliment, but the referent of the present participle is always a situation rather than the hearer in Form B, whereas the referent of the past participle is always the hearer in Form A. The speaker is the subject of the verb of S2 which references the act of observing or recognizing which, in turn, takes as its object a complementizer phrase centered around a subject of the addressee or situation characterized by an adjective that contains within it a verb that describes some act of feeling or emoting.

Through the use of verbum sentiendi, acts of perception become laminated upon participants as emotional states during the act of speech. This form is similar to the one that Austin (Reference Austin1975) and Searle (Reference Searle2008) noted in their discussions of performative speech acts in that it utilizes the first person and the simple present tense with a special kind of verb (dicendi/’speech’ or sentiendi/’perception’).Footnote 2 In fact some forms of empathy statements are performative locutions in that they use verbum dicendi statements, such as “I agree.”

Empathy statements are speech acts, much like performative locutions in that, rather than convey a denotational message in order to provide information (e.g., My computer is broken), they create a role alignment between the subjects of S1 and S2, the customer and customer service agent. In this role alignment, the subject of S1 is the customer (k) or the situation (l) which is affecting (k) who is explicitly indicated if there is the presence of a prepositional phrase compliment (e.g., “I see that thisl must be challenging for youk”).

The form of these empathy statements was explicitly shared with the TTT trainees by the head trainer Asher. After he explained the grammatical form of the statement, he moved on to discuss the importance of selecting the right emotive adjective. This was crucial to using empathy statements effectively. The performative framework was laid out in the grammar of the sentence, but their effect was closely related to the choice of emotional adjectives.

Learning to neutralize feeling

Though the basic format for empathy statements in Figure 1 sheds light on the grammatical categories involved in these statements’ production, describing the format of empathy statements was only the first TTT lesson in their use. The next part of the training was focused on differentiating between “good” and “bad” empathy statements in a wide range of contexts. This involved two kinds of semiotic frameworks: the differentiation between the two grammatical options for empathy statements and the choice of the right kind of emotive adjective. All empathy statements are not made the same, and some of those differences are embedded in overtly described grammatical categories. Form A and Form B from Figure 1 were not considered of equal effectiveness. Asher explained to the trainees that empathy statements with present participle adjectives (Form B) were better for dealing with customer feelings than past participle (Form A):

Asher: Yeah, so you can either say, “I understand how disoriented you must feel,” or you can say, “I understand how disorienting”, present participle, “it must be for you.” So, there are two ways of saying it. I actually prefer targeting the situation, because we don’t want to say how you feel, because then we are, like, questioning their ability to deal with the situation. Like, “You must be disoriented.” Maybe you’re not. Maybe someone else would not be. But if I’m saying the situation can be disorienting, it means it could be for everyone. So, I prefer this one [points at “present participle” on the whiteboard] but this one [points at “past participle”] is not completely wrong. You could use that as well. “I can understand how frustrated you must be,” but I feel it’s better to say how frustrating the situation is, because then you are targeting the situation. You aren’t targeting the person. That’s what empathy is about.

The fact that the past participle of a verb and the present participle of a verb orient differently towards their subjects means that utterances with these grammatical forms of emotive verbs have a head which is either the origin of the feeling or the receiver of the feeling. In the case of “disoriented,” the subject of the sentence is the one who experiences disorientation (its object), whereas in the case of “disorienting,” the subject is the thing which causes the disorientation (its subject). In a sentence “x disorients y,” the subject (x) is the origin of the disorientation, whereas the object (y) is the receiver of the disorientation. Disorient, as a transitive verb, takes two predicates: Disorient(x,y). In the sentence “x is disorienting for y,” the relationship between x and y is still Disorient(x,y). In the sentence “y is disoriented by x” the relation Disorient(x,y) stays the same, but y is the grammatical subject of the sentence rather than the object. It is for this reason that “Jena is frustrated” and “Jena is frustrating” have very different meanings. Taking into consideration the performative nature of empathy statements, the feeling that is being laminated takes on a different object depending on which form is used and has a different social effect.

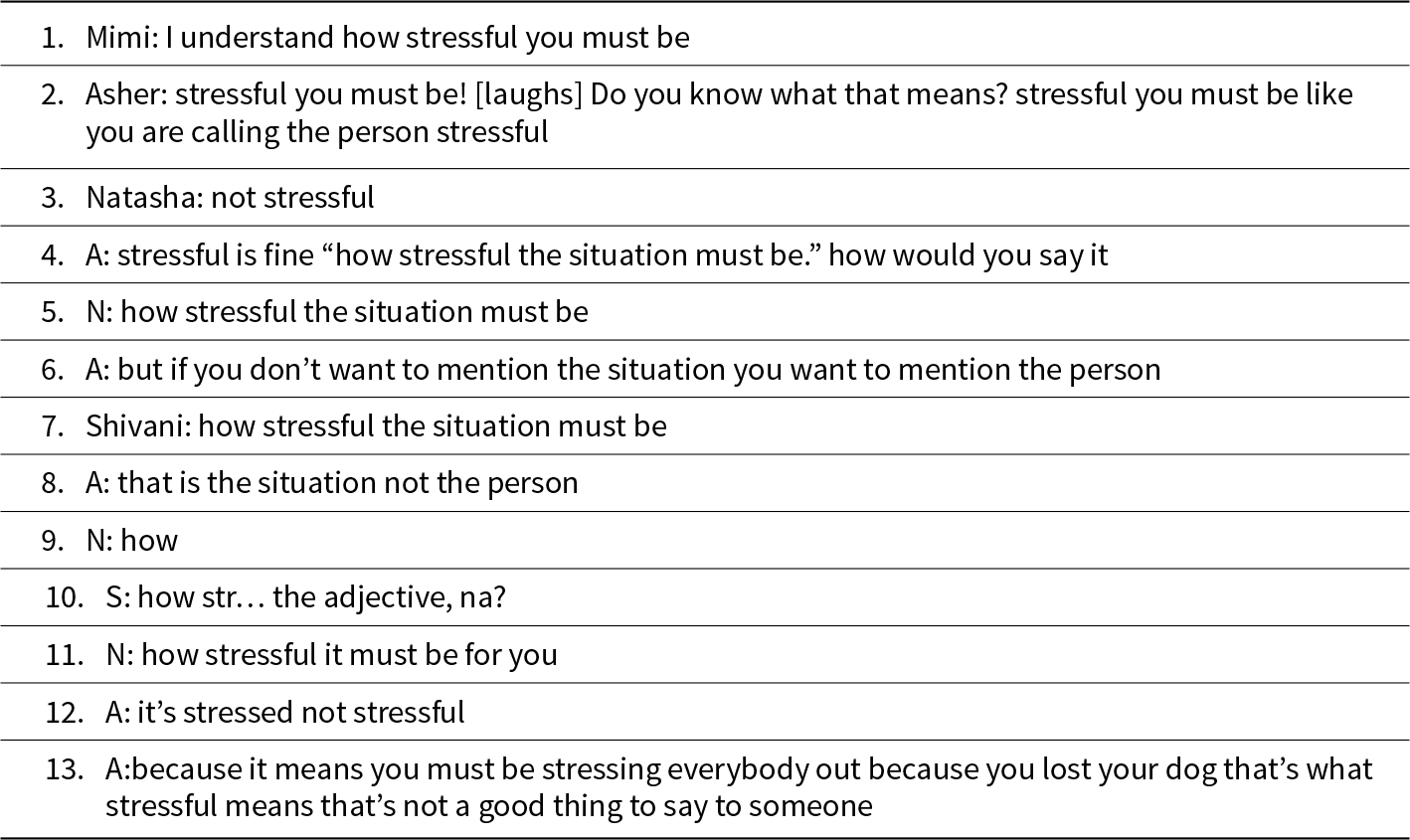

This difference was highlighted in the case of Mimi, the TTT trainee from Manipur, trying to produce an empathy statement using a derivation of the verb “to stress” for a person who lost their dog, a continuation of the introduction story. The other trainees, Natasha and Shivani, try to help her find the right kind of adjective to make an adequate empathy statement.

In Table 1, Mimi uses stressful instead of stressed with the subject of a person, indicating that the cause of the stress was “you,” the hearer. Natasha and Shivani work together to fix Mimi’s mistake. To further cement the lesson on participles, Asher gives the example of “stressing everybody out” as the equivalent of “stressful.” To make an empathy statement, a call center worker must form a sentence with the pronoun “I” as the subject of a verb of observation, followed by an emotive verbal adjective. However, the choice of the right adjective and emotion word was important to crafting a “good” empathy statement.

Table 1. Stressed and stressful

Different emotive verbal adjectives in empathy statements were ranked and graded in Asher’s feedback to trainees in relation to their relative “strength.” Empathy adjectives that were “too strong” were undesirable, especially in the case of negative emotions. In one study of call center debt collectors, the juxtaposing of emotional orientation was one tactic used in controlling customer response in Indian call centers (Poster Reference Poster2013). In the TTT at ODSS, the trainers in training were not expected to counter emotions with their opposites, but rather mirror customer emotions with slightly “less intensity.”

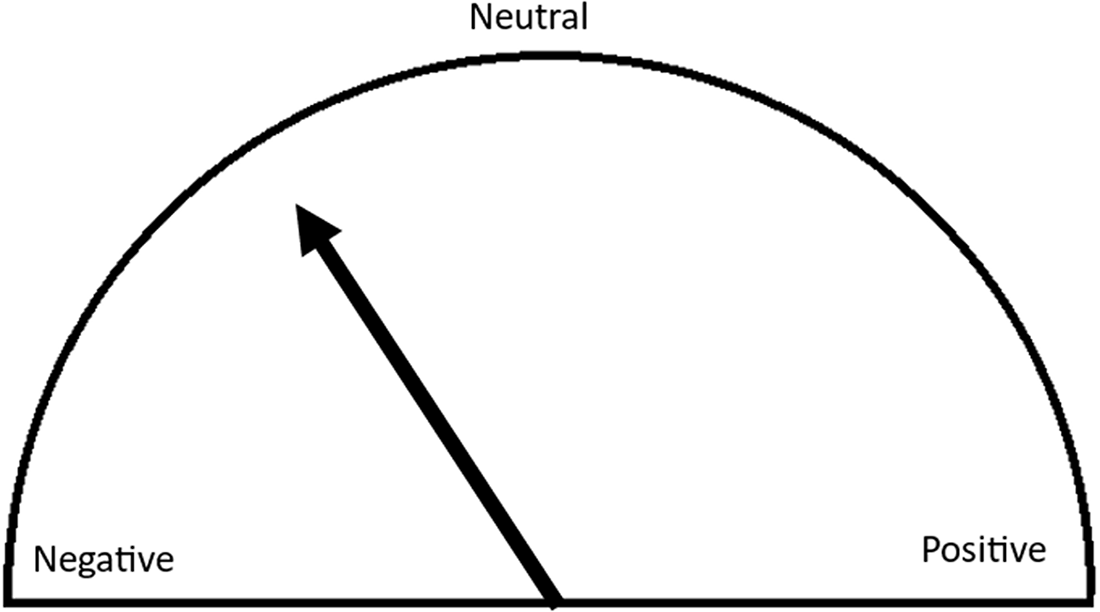

Asher explained that emotions could be positive, negative, or neutral in their orientation and drew an emoti-meter (depicted in Figure 2) on the board where one side was negative emotions, the other side was positive emotions, and “neutral” was in the middle. Empathy statements, he explained, were geared towards the emotional orientation of the customer, but would be slightly more “neutral,” in order to keep customers away from expressing extreme emotions on a call.

Figure 2. Reproduction of the “emoti-meter” Asher drew on the whiteboard.

“Neutral” as a term is highlighted in emotive training in a way which parallels its use in accent training (author, 2025). Being recognized as “neutral” according a semiotic framework of emotions was key to being appropriate to use in empathy statements. A customer’s emotions needed to be ratified but not overstated. Through training, Asher imbued certain words with relatively “marked” emotional values.

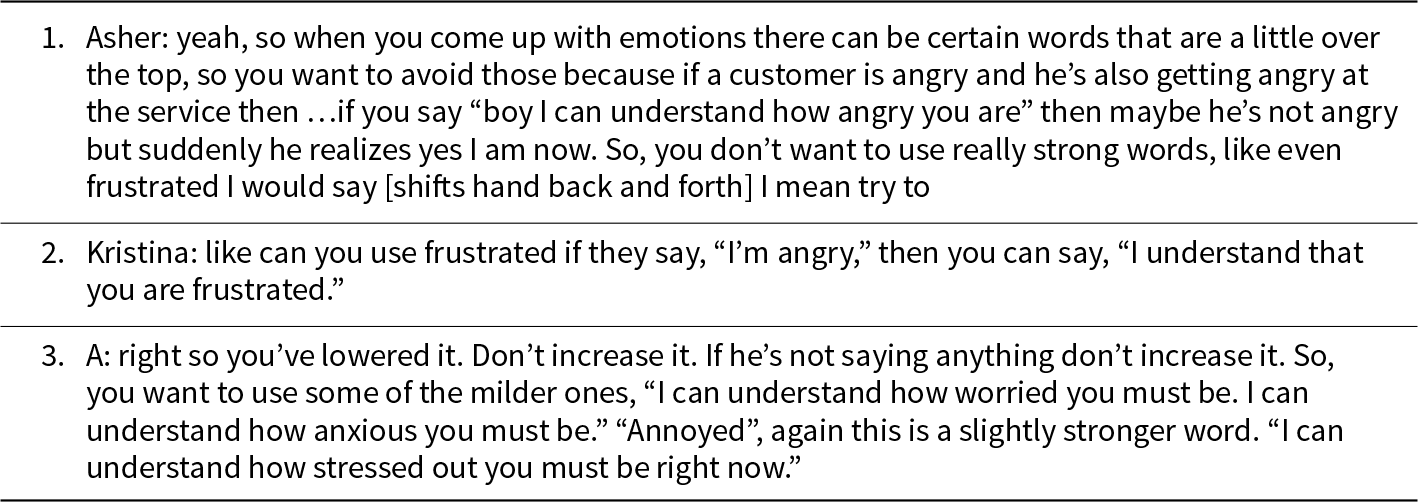

Besides their positive and negative valences, emotive words would vary in how “strong” they were. Weaker words were closer to neutral valence and better for “safer” empathy statements. In one activity, Asher had the cohort of trainees list emotive adjectives for someone who had lost their phone. The group came up with the words “disoriented,” “sad,” “angry,” “insecure,” “irate,” “frustrated,” “stressed,” “depressed,” “worried,” “helpless,” “tense,” and “anxious.” Asher then asked the group which of these words could be used in an empathy statement starting with “I understand you must be …” Some of the words were deemed “too strong” to use in good empathy statements, in Table 2 Asher describes why it is important to use words that are more neutral, rather than “strong” words.

Table 2. Neutral emotive adjectives

Shown in Table 2, Asher and my interaction during training shows how “lowering” the adjective is a tactic to deal with customer emotions. He also hierarchizes the adjectives. “Annoyed” is stronger than “anxious” which is stronger than “worried.” “Angry” is also deemed “too strong” to use in an effective empathy statement.

Translating emotion and enregistering empathy

Learning the semiotic frameworks discussed above involved practice through mock scenarios where Asher would evaluate statements that the trainees came up with. This process of enregisterment often involved formulating some kinds of feedback as Indian and others as acceptable forms of empathy. Trainees practiced empathy statements in an activity where they were given nine scenarios and had to write an empathy statement for each one, which they would then present for Asher to critique. Asher’s feedback was in relation to the relative “power” of the statement they designed and its adherence to the format of the empathy statement. Sometimes it was okay to break the grammatical form of the empathy statement, but those situations were also critiqued and given feedback on the relative appropriateness of the response. In this way, through repetition and constant metapragmatic commentary, trainees were enregistered into this new system of emotive speech. Forms which would typically be indicative of care for an Indian audience but less appreciated by American customers (e.g., advice) were banned, and gradually trainees learned how to make empathy statements on the fly.

In the first scenario in Table 3, Asher describes Nitasha’s response to a customer’s new job as “overkill.” He also is worried that the wrong tone with the words “good luck” could indicate sarcasm. He rejects these statements but also uses comparative constructs, like “over” and “enough.” There is a fine balance in finding the right power of a response that was still confusing for the trainees. Arriving at the best response of “congratulations” was only achieved after a somewhat long process of commensuration as different responses are tried, compared, and reformulated, much like how accents were trained in the previous chapter. Nuanced ideas about appropriate responses that might seem normal to an American client are rigorously trained in these back-and-forth sessions.

Table 3. New job

In Table 4, all three of the trainees in attendance that day formulated an answer to the scenario of a customer whose son has a birthday. In these responses, Asher responds to the strength of Nitasha’s word “nice” but the tone of the responses of Mimi and Shivangi. In response to Asher’s request for “more excitement,” Shivangi attempted to sound like me by raising her pitch and on her second try did so in a way that sounded dramatic to the point of sarcasm. This kind of speech was often associated with American voices, such as mine, and felt weird for the trainees. Like with the “power” of emotion adjective for empathy statements, finding the right balance in tone was also key to nailing empathy.

Table 4. Son’s birthday

The third (Table 5) scenario was a customer who was divorced. This scenario posed a problem and was meant to represent a social difference between India and the United States. In India, divorce is often considered a taboo subject, especially among Hindus. However, in the United States, divorce is sometimes welcomed and might be associated with relief. The trainees struggled to find the right tone, without knowing the emotional state of the imagined customer relative to his divorce. At the end, Asher refers to me as an American cultural expert to come up with an appropriate response to news of a divorce, which was not to empathize at all.

Table 5. Divorce

In this situation, I was a bit stumped at first in trying to figure out what exactly Asher was going for. I was learning about empathy statements myself. However, Asher assumed that this knowledge would be a part of my cultural knowledge as an American. This shows how empathy statements were viewed as an act of translation.

In the beginning vignette, Mimi is chastised for advising a customer. In this and in other practice situations, whenever trainees suggested what the figurative customer should do with themselves, Asher told them that what they were saying was advice and not empathy, and identified advice as an Indian response to situations. We explained to trainees that though Indians often associated advice with care, Americans do not view unsolicited advice favorably. They often feel judged rather than cared for. In a scenario where the customer was faced with a hurricane event, Shivangi suggested that they take shelter to which Asher doubled down on the importance of never giving advice to customers.

Empathy statements were formulated as alternatives to Indian ways of to responding to emotion. Once the trainees started to understand how to formulate them and use them in response to practice situations, they were taught to use them in scripts that were specific to customer service situations. In the next section, I show how these statements were used to mitigate potential emotional responses of customers in calling scripts.

Empathy in scripts

Empathy statements are always embedded in a speech chain of interactions where they are an n + 1 utterance, where n is something said by the customer which indicates an emotional state. Asher told the trainees that they needed to listen to the tone of voice of the customer to understand their emotional state and to listen to the customer’s words to understand the situation. A good empathy statement accurately accounts for both the situation and the customer’s emotional state. Using the format laid out in Figure 1, empathy statements create role alignments between customer and customer service representative to meet a goal of the customer service rep. The speech chain of these interactions is described in Figure 3. The eventual goal of an empathy statement is to intervein in the conversation so that the n + r action of the customer (k) is to give agent (j) a satisfactory customer service score, or “CSAT” score. The higher an agent’s average CSAT score, the more money that agent is able to make. CSAT scores are also how BPOs report success to the companies that hire them to manage their customer service. The n utterance is meant to be represented in the S1 portion of empathy statements (e.g., you must be frustrated, that situation must be frustrating) and by embedding this phrase in S2, the agent indicates their own understanding of the customer’s emotion in an attempt to laminate feelings onto role alignments in an attempt to intervein in the conversational flow.

Figure 3. Speech chain analysis of empathy interaction.Footnote 4

Empathy statements formed a key part of several important scripts for call center soft skills training. These include dealing with irate customers, polite refusal/service no, call openings, and apologizing. In these scripts, call center agents were meant to use empathy statements to temper clients’ negative emotions.

After trainees learned the grammatical form of empathy statements and how to pick relatively “neutral” emotions to use in them, they were able to use empathy statements in calling scripts. Scripts are flow charts for interactions with customers, though customer service agents are expected to improvise and almost always do so (Woydack and Lockwood Reference Woydack and Lockwood2017). Empathy statements are worked into scripts for the general call flow and for specific interventions as moments where the agent must improvise relative to the emotional state and situation of the customer.

Empathy statements in the TTT were worked into three scripts: the general call flow, dealing with irate customers, and the service no. In a general call flow, an empathy statement is used directly after a customer identifies their problem. According to Asher, this empathy statement is meant to build rapport with the customer and ratify their emptions in the situation. In other situations, empathy statements are used as the need arises.

When a customer wants something that they cannot have, customer service agents need to say “no” while still trying to achieve a good CSAT score at the end of the call. This is done through what the industry calls a “service no.” In Table 6, I lay out the steps of a service no. The empathy statement is used as the first step in the refusal to temper the response of a customer to being denied at a later step. This script is repeated each time a refusal needs to be made. Asher used the example of a customer wanting to buy a printer model but that model not being available. He started by recognizing the customer’s desire for the printer in an empathy statement and then stating the reason for the denial before actually delivering the news, followed by immediately tempering the news with viable alternatives.Footnote 5

Table 6. Service no

Empathy statements were translations of Indian emotive responses into more Americanized ones but also were used to translate the feelings of customers into more “neutral” forms, ideally earning high customer satisfaction scores. These statements were ways of performatively setting the emotional expectations of an interaction, sometimes altering the tone that the customer sets before the statement is uttered.

Conclusion

People, the world over, talk about feelings. The way that we express those feelings is highly variable. Further, the way we expect people to respond to our talk about feelings is contextually relative. While there has been a push in recent years away from a focus on the semiotics of such interactions, especially in literature on affect, the example I have put forward in this paper shows how feelings and their exchanges are semiotically grounded and far from universal. Rather, feelings need translating. Call center workers train hard to learn how to navigate expected linguistic formulation of feelings with the help of empathy statements.

Call center workers engage in translation as they learn a new way of talking about and formulating emotion during training. Responses that involve advice are formulated as a type of “Indian” emotional talk and empathy statements are offered by Asher as a new professional, American alternative. The rendering of words as commensurate and interchangeable is by no means a neutral process. On calls, they use empathy statements to reformulate emotional phrases of customers, using the tool of translation to navigate emotionally heightened situations. “Angry” becomes “frustrated.” “Anxious” becomes “concerned.” “I understand that you are worried” itself is a performative statement that sets the tone of customer interactions.

The processes laid out in the paper show how translation is not limited to words and sounds, but also can involve formulations of feeling. One emotive response can be equated to another in translative frameworks. The overtly performative nature of empathy statements is not limited to the translation of empathy, but to any form of translation. In a world where we are exposed to emotive talk from all over the world through media, translation is anything but a neutral exchange of one code for another. The act of translation itself changes our social worlds through reflexively formulating new semiotic frameworks within which we imagine ourselves and others.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Fulbright-Nehru fellowship, the Center for the Advanced Study of India, at the University of Pennsylvania. I would like to thank Ashish Khan and Dr. Asher Jesudoss at One Direction Skill Solutions for their continued support of my research. I am grateful for the advice of Asif Agha, Greg Urban, and Andrew Curruthers during the research and writing process.