There has been a surge of interest in policy advisory systems (PAS): the assemblage of advisory units and practices that exist at a given time with which governments and other actors engage for policy purposes (Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020). Initially, the conventional approach captured the basic domestic public sector sources of policy advice along with the political components and international advisory bodies but has since expanded as researchers have detailed important changes in the number and type of policy advisers, their role within these systems, and as comparative analysis has shed light on how they operate and evolve (Aubin and Brans Reference Aubin and Brans2021; Howlett Reference Howlett2019; Hustedt and Veit Reference Hustedt and Veit2017; Hustedt Reference Hustedt2019; van den Berg Reference van den Berg2017). Yet, a major gap remains with little to no attention having been paid to how governments attempt to manage these systems. That is, how governments seek to optimise PAS configuration and operation for their governance needs. This can be done through privileging or marginalising particular sets of advisers including public servants, private sector consultants, various specialised advisory bodies, or via structural and procedural changes that alter how these systems of advice operate.

While recognised in the literature, PAS management remains undertheorised and insufficiently linked to the empirical findings gained through rigorous study of countries and sectors spanning several administrative traditions. It most often remains implicitly associated with the degree of “control” exercised by elected governments over the available supplies and the advisory system itself (Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020; Halligan Reference Halligan, Peters and Savoie1995). In this article, we argue that PAS management is best characterised as government agency – involving choices by prime ministers and ministers about when and how the government exercises its power in policymaking contexts with varying degrees of government discretion to intervene. Even in contexts where governments maintain high degrees of control, they may choose not to engage in PAS management, whereas they may choose or be compelled to engage in PAS management in situations in which they have little to no control. Drawing on an analysis of PAS experiences in four countries within the anglophone administrative tradition – Australia, Britain, Canada, and New Zealand – we introduce and develop concepts and analysis to further our understanding and the study of PAS.

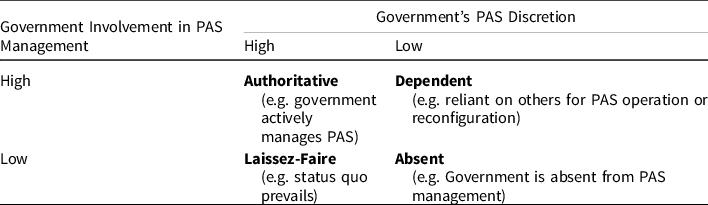

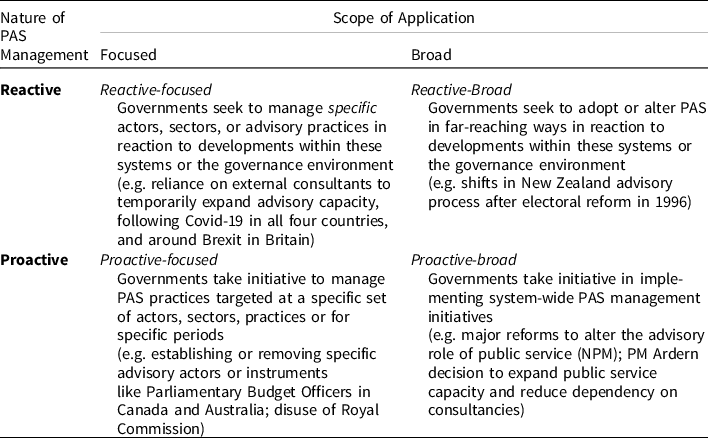

We argue that PAS management falls into four forms: authoritative, dependent, laissez-faire, or absent, based on government agency and discretion rather than simply degrees of control governments may exert. While we theorise and identify these forms as distinct, we acknowledge that in practice, governments may adopt a combination of these forms as they deal with multiple policy issues while governing. We apply this typology to cases from the four countries using evidence from secondary literature to illustrate and clarify how various governments have applied these approaches. The analysis supports the importance of agency and discretion and also underscores that these important aspects of PAS management lead to differences in the country and situation-specific applications of these management forms. Governments adopt a range of instruments and initiatives in their attempts to Manage PAS that vary based on the targeted or broad scope of PAS management. Additionally, management can be triggered by governments seeking to proactively manage PAS or reactively, following developments that compel or invite governments to respond. Analysis of the experience of these four countries and the typologies developed provide further clarity on questions of PAS management. This helps orient analysis away from exclusive considerations of government control to analysis of government agency and discretion, and to the scope and nature of PAS management. This opens up new avenues for theory building and empirical study of PAS, including the conditions under which governments take up different management forms, how they materialise in practice, and the role that context and constraints play in impacting PAS management in specific applications, and under various administrative traditions.

Theorising policy advisory “system” management

Initial theorising and study of PAS was focused on description and analysis of the supply and demand of advice, variation in the types of policy advice, and country and governance contexts pertinent to advising governments. The notion of a system was used loosely, as a device to categorise and analyse regular advisory practices and interactions amongst a set of actors typically bounded by country-level analysis (Plowden Reference Plowden1987). Locational approaches dominated with research focused on the where and who of policy advice – proximity and distribution of policy advisory supply within and around governments were linked to policy influence (Halligan Reference Halligan, Peters and Savoie1995; March et al. Reference March, Toke, Befrage, Tepe and McGough2009). Research also sought to understand the causes and consequences of shifts in the demand for advice on the part of the government, typically prime ministers and ministers. Additionally, it engaged with questions about supply-side dynamics, often focused on public services or debates about technocracy, evidence basis, politicisation of the public service, and the role of various brokers who served to match supply with demand in these systems (Peters and Barker Reference Peters and Barker1993; Verschuere Reference Verschuere2009; Craft and Howlett Reference Craft and Howlett2012).

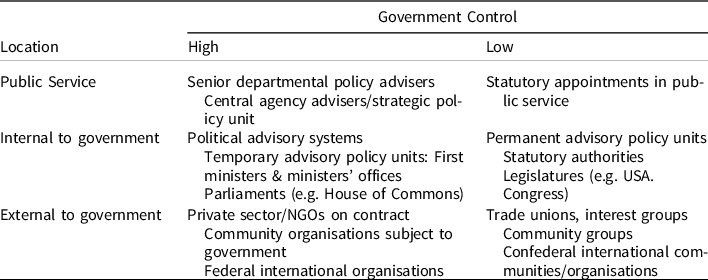

The PAS management-like research that did exist was typically on discrete sets of advisers, particularly the public service who long dominated the world of professional policy advice to government, and to a lesser extent think tanks and international advisory bodies (Abelson Reference Abelson2018; Fleischer Reference Fleischer2009; Meltsner Reference Meltsner1976; Pautz Reference Pautz2012). Management of PAS itself was not explicitly theorised though researchers recognised a variety of ways in which these systems could be organised, considered the benefits and costs of informal versus institutionalised approaches to advisory activity, and recognised tensions and dilemmas in advisory arrangements in democratic polities (Pierre Reference Pierre, Peters and Savoie1998; Seymour-Ure Reference Seymour-Ure and Plowden1987). Halligan’s (Reference Halligan, Peters and Savoie1995) use of government “control” over policy advice sources as a dimension of analysis focused thinking around the ability of governments to exert discretion over advice from certain quarters (see Table 1). It represents an early and implicit attempt to grapple with the management of PAS. In a similar vein, Boston (Reference Boston1994) set out various strategies and tactics that governments could employ when purchasing policy advice. For example, creating and altering market-like conditions to spur improved supply, contestability, and quality in advisory offerings. This, however, often came with costs particularly to policy coordination and coherence. Of note, Halligan and Boston were writing at a time marked by intensive scrutiny of managerialism reforms and new public management practices that were directly engaging with questions of the efficacy of more traditional command and control forms of public administration.

Table 1. Location and control approach to PAS

Source: Halligan (Reference Halligan, Peters and Savoie1995).

We argue that going beyond control to focus on the power and agency of elected governments is essential for improving our ability to understand how governments manage PAS. Not only does this better reflect the reality that governments must often seek to manage PAS in situations in which they have little to no control but it also recognises that the use of direct government control over advisory sources is only one of a number of choices available for PAS management. Governments can use their agency and resources (or not) to prioritise or marginalise policy issues or actors, to frame and create discourse around policy matters, policy instruments, or the target groups of policy, or to persuade, communicate, and (dis)credit-specific sources of policy advice (Craft Reference Craft2022; Majone Reference Majone1989; Schnieder and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1990). Moreover, not only has the governance literature pointed to the limits on state-based command and control forms of governing (see Peters et al. Reference Peters, Pierre, Sørensen and Torfing2022), but it has also highlighted variations in state-centred and collaborative governance arrangements that can involve governments’ use of so-called “soft” power including persuasion, steering, network management, and co-design and co-development or outright dependence on other actors for governance (Dahlstrom et al. Reference Dahlstrom, Peters and Pierre2011; Diamond Reference Diamond2020a; Craft and Howlett Reference Craft and Howlett2012; Peters et al. Reference Peters, Pierre, Sørensen and Torfing2022). This greater range of agency and more diverse set of potential governance arrangements raises major questions about how we conceptualise and understand how governments seek to manage PAS.

Forms of PAS management

The different forms of management are then based on whether governments choose to engage in PAS management (agency) and whether they have the discretion (power) to do so. These two elements form the primary dimensions in the typology of PAS management forms. Agency in PAS management reflects more than control over sources of advice, involving the broader ways governments use their power, resources, and the constraints that shape how governments approach PAS and interact with these systems. As noted, the anglophone administrative tradition provides extensive flexibility and considerable latitude for governments to organise the machinery of government and implement their preferred modes of governing (Halligan Reference Halligan2020; Peters Reference Peters2021).

The level of discretion, on the other hand, involves the degree to which the government has the power Footnote 1 to engage in management of PAS. Government power, in this context, relates its ability to command authority and resources and to use them to direct and influence PAS operation. To account for the variety of ways in which governments seek to do so, we intentionally take a broad definition of power in this context, while recognising that in practice governments may utilise this power in multiple ways – including through direct and overt coercion, changes to assigned roles or responsibilities, capacities and resources, or through its demand and sourcing of advice, as well as through soft power. This recognises that regardless of their agency – governments require authority and resources to manage these systems. Governments in these four countries wield democratically derived authority and can use executive powers to direct bureaucracies, (re)organise the machinery of government, prioritise policy issues or structures, and manage advisory processes. However, discretion also acknowledges that governments face a number of constraints to manage PAS given the contexts and administrative traditions within which they operate. These include legal, constitutional, or legislative constraints, as well as the operational resources required to intervene. These constraints often reflect long-term legacies of administrative traditions that establish appropriate norms, institutional design and operating customs, and values within which PAS operates (Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020; Peters Reference Peters2021). We thus identify these two elements – the degree to which governments decide to engage in PAS management (agency) and their discretion to do so as fundamental to understanding PAS management. Table 2 presents four typical PAS management forms based on these two dimensions and we provide examples of each in our subsequent analysis.

Table 2. Forms of PAS management

Source: Authors.

In situations where government involvement in PAS is high and they also have a high degree of discretion, PAS management takes an authoritative form. In such cases, the government actively engages in PAS management and uses its authority and resources to intervene in the advisory system. In other instances, where the government seeks to involve itself in PAS management but does not have the requisite discretion, PAS management takes on a dependent form. Governments may be inclined to intervene in PAS operation but lack the resources or authorities to do so and are dependent on other policy actors – whether domestic, international, or from the private and third sectors. In such instances, the government is reliant on other PAS actors.

Laissez-Faire forms of PAS management are differentiated by the fact that the government has discretion but opts for the status quo. This form of PAS management is characterised by no major efforts or attempts to manage advisory units or processes that depart from their existing practices. This form characterises a government taking a more “hands-off” approach, for instance favouring self-regulatory activity or public service management of its policy capacity and advisory practices. Government would govern within the confines of the existing PAS. A final form involves scenarios where governments cannot seek to actively manage areas of the PAS at all and also have little to no discretion to do so. In such instances, we are likely to see an Absent form of PAS management. The crucial distinction here is that the government lacks the discretion to manage PAS in a consequential way. The configuration of the PAS then reflects the interests, policy ideas, and preferences of actors from the broader policy subsystem. This form may be prominent in matters that fall under private authority but have public policy implications, pluralist policy areas where a greater policy capacity and policy-relevant knowledge is concentrated outside of the government/public service, and in area governed by international, supranational, or multi-level governance contexts, and where longstanding dependencies have been created with external advisers (e.g. consultants) which have eroded governmental ability to exercise authority on advisory matters.

Comparing Anglo Westminster style PAS: Research design

To advance our knowledge of how governments manage PAS, we focus on the four countries within the shared “Westminster” Anglophone administrative tradition (Australia, Canada, UK and New Zealand) to test and advance the typology of PAS management forms. We acknowledge there are debates within the literature about the usefulness of the term “Westminster” (see Flinders et al. Reference Flinders, Judge, Rhodes and Vatter2022; Russell and Serban Reference Russell and Serban2021). We do however accept that the Westminster tradition is based on shared principles, traditions, and key features, most notably: responsible government and strong cabinet government based on a fusion of the executive and parliament, individual and collective ministerial responsibility, the rule of law, and a permanent public service that is nonpartisan and professional (Grube and Howard Reference Grube and Howard2016; Rhodes et al. Reference Rhodes, Wanna and Weller2009; Richards and Smith Reference Richards and Smith2002)i. The anglophone administrative tradition is also amongst the most flexible which also makes it particularly well suited to studies of PAS management (Halligan Reference Halligan2020; Peters Reference Peters2021; Rhodes et al. Reference Rhodes, Wanna and Weller2009). Prime ministers in particular posses considerable authority in determining how cabinet is constituted and operates, how prime ministers and ministers approach policymaking, the machinery of government, parliament, and how political executive engages with parliament and other policy actors (Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020; Lindquist and Eichbaum Reference Lindquist and Eichbaum2016; Weller Reference Weller2018). Further, having gone through major changes following the adoption of NPM and consecutive reforms, which diversified the scope and type of levers governments have over advisory sources, anglo-Westminster countries serve as “paradigmatic” cases (see Flyvbjerg, Reference Flyvbjerg2011) for applying the typology of PAS management. The changes in the relative roles of advisory sources that followed NPM reforms (and primarily, the dynamics of externalisation and politicisation pervasive in all four countries, albeit with important differences, see Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020) provide a ready landscape for (as well as complicate) government’s involvement in PAS operation.

We apply the theory developed to the diachronic analysis of these countries using secondary literature. We rely on the fundamentals of case study approaches in political and policy sciences: an intense study of a specific unit, with an emphasis on how events interact with contextual factors (Flyvbjerg Reference Flyvbjerg2011; Meyer Reference Meyer2001). We take the approach of “multiple case studies,” as appropriate for studies in which the phenomena of interest appears in multiple contexts, and exploit the similarities in context between the cases (Yin Reference Yin1981, Reference Yin2009; Stake Reference Stake1995). The unit of analysis for this work is cases of government management of PAS in the four countries: that is, we focus on instances where governments – used here to denote the political executive elected with the power to manage PAS rather than the broader executive – engage in altering the configurations and operation of PAS. The cases are all government-, issue-, and context-specific. We adopt convenience sampling by focusing on well-known and well-documented examples of government involvement in advisory systems in these countries. We use the cases to apply, test, and refine the “conceptual categories that guide the research” (Meyer Reference Meyer2001, p. 331; see also: Stake Reference Stake, Denzin and Lincoln2008) and recognise the limits this presents for claims of causality or generalisability. While this limits our ability to claim generalisability, it does support our theoretical approach and facilitates an exploratory and descriptive analysis of how governments seek to manage PAS. It is also in keeping with the “second wave” approach in the study of PAS (Craft and Wilder Reference Craft and Wilder2017), that has called for analysis of PAS grounded in the policy subsystem and focuses on system-level analysis.

Learning from Westminster style governments: PAS management in practice in Anglo Westminster

The cases, while sharing a similar administrative tradition, have seen their own country-specific interpretations and applications of those traditions and various public sector reforms (Aucoin Reference Aucoin1995; Halligan Reference Halligan2020). Similarly, while politicisation and externalisation Footnote 2 have been used to chart major dynamics reshaping Westminster style PAS as a whole (Aucoin Reference Aucoin2012; Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020; Diamond Reference Diamond2020a, Reference Diamond2020b), analysis has revealed how these PAS dynamics have varied both among the countries and over time (Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2017). The interaction of involvement and discretion as set above in Table 1 produce different forms of PAS management, but we argue these manifest themselves in various country and policy-specific practices and initiatives which reflect country, policy, and governance contexts specific to each country. In this section, we provide a range of examples drawn from the secondary literature of how governments have engaged in PAS which further support the authoritative, dependent, laissez-faire, and absentee forms of PAS management and provide concrete applications within the forms

Constraining and restoring public service policy capacity

Altering public service policy capacity is a common practice of governments adopting an authoritative form of PAS management. Most analyses of these countries weighs heavily with analysis of NPM and subsequent administrative reforms, with governments actively constraining the policy capacity of the public sectors to address perceived or real issues of their responsiveness and efficiency (Aucoin Reference Aucoin1995; Halligan Reference Halligan2020; Pollitt and Bouckaert Reference Pollitt and Bouckaert2017). Restraining, repurposing, or eroding public service capacity is also preferred when governments deem the bureaucracy as obstructionist to their policy agenda, and when decision-makers’ attempt to overcome a “bureaucratic capture.” In practice, this is achieved by halting hiring in the public service; outsourcing research and policy analysis functions that were once within the realm of the public service; or actively closing departments and units (Boston Reference Boston1994; Commonwealth of Australia 2021; Halligan Reference Halligan2020; Zussman Reference Zussman and Parson2015).

Conversely, governments can use such authoritative PAS management to manage or rebuild public service capacity for policy advisory purposes. This typically involves reallocating existing policy resources amongst departments or agencies for various priorities (Henderson and Craft Reference Henderson and Craft2022) or expanding the size of public sector units of policy analysis and research by investing in recruiting and training civil service employees. These efforts enable governments to respond directly to some of the massive impact on policy capacity that resulted from administrative reforms and from the rise of complex policy problems, demanding more extensive and nuanced policy expertise and skills. For example, in New Zealand in 2018 the Ardern government announced it was removing the cap on hiring core public service staff, a policy that was introduced following the financial crisis in 2008, to rebuild its policy capacity and reversing the extensive reliance on private market consultants (Bennet Reference Bennet2018; Government of New Zealand 2018). In contrast, in Australia, less has been done to address persistent challenges in public service capacity despite successive research and calls for by public sector reviews that have consistently underscored clear capability problems (APSC 2014; Commonwealth of Australia 2021; Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 2019; Head Reference Head, Head and Crowley2015; Tiernan Reference Tiernan2011; Lindquist and Tiernan Reference Lindquist and Tiernan2011).

Managing advisory processes and accessibility

Governments also wield significant discretion and demonstrate high involvement in shaping the accessibility and processes by which policy advice is generated and consumed, which is another practice of Authoritative management. In all four countries, the elected government directly controls many aspects of the machinery of government, which allows governments to set the policy agenda, shape key policy sequencing, and various procedural requirements or preferences that match with its desires for consultation, transparency, or opacity (Rhodes et al. Reference Rhodes, Wanna and Weller2009; Weller Reference Weller2018). Indeed, governments have had to manage the PAS tensions inherent in Westminster style government whereby pressures to “open up” policy processes butt up against Westminster traditions that emphasise secrecy and cabinet confidentiality, and bureaucratic anonymity. A vivid illustration of comparative differences would be the move by the New Zealand executive to make public all cabinet minutes which reveal the advice and deliberations of cabinet. In contrast, the other three jurisdictions continue to function under classical cabinet secrecy modes with cabinet documents and deliberations becoming public only after lengthy periods (Campagnolo Reference Campagnolo2020). Another illustration is the tensions created in PAS management given the adoption of access to information regimes in all four countries. While these, as a general rule, provide some public access to information about government policymaking, governments have continued to use the tactic of assigning advice as a cabinet confidence to provide immunity from such disclosures given the scrutiny and politics that such releases engender (Roberts Reference Roberts2005; Campagnolo Reference Campagnolo2020; Hazell and Worthy Reference Hazell and Worthy2010).

Similarly, there are a variety of choices governments make around how they engage in public consultation as an input into the advisory processes of government, and if and how they proactively release information about advisory matters to the public. Governments can strategically manipulate the number, type, and timing of public consultations, or at times must manage through those that are mandated as part of legislated changes to regulations or programmes (Fraussen et al. Reference Fraussen, Albareda and Braun2020). Some governments have sought to use consultation as a tactic to manage policy deliberations, shifting them to favourable or more political arenas, while others have sought to avoid or minimise them in favour of more closed and bureaucratic advisory and policy development practices (Boucher Reference Boucher2013). More guarded or careful consultations with stakeholders and muzzling of science policy advice within government were ongoing criticisms of the Harper government in Canada (Zussman Reference Zussman and Parson2015, Reference Zussman, Ditchburn and Fox2016).

Using or marginalising nonpublic service public sector advisors

Another practice that has been used in all four Westminster PAS involves efforts to limit or cultivate advisers within the public sector but outside of the public service. Such efforts include the development of research and analysis capacities in parliamentary committees and the use of public auditors to review public sector performance, or expanding use of dedicated reviews commissioned by ministers, with varying levels of independence (Diamond Reference Diamond2018; Holland Reference Holland2020; Manwaring Reference Manwaring2018). At other times, it can involve the government closing down such advisory bodies as was illustrated in 2012 when the Harper government dismantled the Canadian National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy, which had served as an independent advisory agent to the government for twenty-five years (Zussman Reference Zussman and Parson2015). Conversely, a Harper-led government created Canada’s first independent Parliamentary Budget Officer in 2008 to provide independent analysis to parliament on economic issues and government finances (Levy Reference Levy2008), Australia created a similar office in 2012, while New Zealand was unable to get parliamentary consensus to establish such an office in 2019 (Coughlan, Reference Coughlan2022; Stewart Reference Stewart2013).

In Australia and Britain, parliamentary committees have been used for inquiries, legislative support as well as exploratory work of new policy agendas. Analysis points to them as having had influence in the policy process and in the expansion and diversification of policy debates (Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020; Monk Reference Monk2012; Rombach Reference Rombach2018). In contrast, Canadian parliamentary committees have largely been ineffective as sources of policy advice though the senate has been active on some issues, while in New Zealand the automatic referral of bills has seen committees increasingly dominated by legislative review (Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020). Governments can also seek to strategically use or marginalise them, as their reports may become thorns in the side of the government who see the policy agenda or media cycle taken over by a damning report or policy advice that runs counter to government preferences.

Indeed, a range of nonpublic service policy advisory instruments are available including blue-ribbon panels, advisory committees on specific issues, task forces, or temporary or longer-term instruments like royal commissions (RC) and commissions of inquiry (CI). These types of instruments typically involve the government issuing broad or specific remits, allocating resources, and often feature nonpublic service advisers and some degree of independence from the government. They can be used for a number of reasons such as to focus public attention, gain expertise on or grapple with complex issues, or to venue shift contentious issues away from governments. The considerable variation in the types and uses if these advisory practices further buoys need to understand why governments adopt such instruments. The empirical record from these four countries points considerable variation but, with the exception of Australia, dramatically less use of royal inquiries and CI given their protracted, resource intensive nature, along with uncertain outcomes from their use (Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2017, 2020, Marsh and Halpin Reference Marsh and Halpin2015).

Externalisation

Government use of external advisers, including private market consultants and think tanks or select senior external advisors, has become a prominent practice in Westminster PAS (Diamond Reference Diamond2020a, Reference Diamond2020b; Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020, Reference Craft and Halligan2017; Savoie Reference Savoie2003). Externalisation reflects a dependent form of PAS management. While the government has agency to redirect issues and advisory resources and activity to externals, it does so because it needs those external actors to secure desired PAS practices or outcomes. Britain provided a vivid illustration of this with governments having spent almost 100 million pounds in 2019 for external policy advice on “no-deal” Brexit planning much of it from large consultancy firms, as government departments were met with shortage in internal capacity to manage the diverse set of issues at a pace sufficient to support national policymaking (CAG/Comptroller and Auditor General (UK) 2019; Cornish Reference Cornish2017). The extensive reliance in all four countries on consulting firms for COVID-19 response is another example (Lewis 2021; Vogelpohl et al. Reference Vogelpohl, Hurl, Howard, Marciano, Purandared and Sturdy2022).

Historically, externalisation featured as part of larger public sector reforms, with the intent to diversify sources of advice to decisionmakers and overcome issues of responsiveness from the public service (Dent Reference Dent2002; Pollit and Bouckaert Reference Pollitt and Bouckaert2017; Halligan Reference Halligan2020). On a smaller scale, it functions as a lever in managing PAS, as it enables governments to supplement lacunes in policy capacity, legitimise policy by providing external credibility, and bypass or create alternatives to in-house advisers (Abelson and Lindquist Reference Abelson and Lindquist2017; MacDermott, Reference MacDermott2008; Marciano Reference Marciano2023; Martin Reference Martin1998; Momani and Khirfan Reference Momani and Khirfan2013). In Australia and Britain, the use of such external advice often depends on the party in power and issue at hand, with some governments drawing on think tanks for policy advisory purposes whereas the comparatively smaller think tank landscape in Canada and New Zealand features their less pronounced regular involvement in policymaking (Abelson Reference Abelson2018; Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020; Pautz Reference Pautz2017).

Continuous reliance on external sources can have accumulating effects on the role and capacity of these actors as well as the standard operating procedures of PAS. It can exacerbate the dependency of governments on externals which has, in Britain and Australia, become widely acknowledged as patterns of externalisation have come to replace various aspects of in-house public service policy work. Studies have repeatedly found a pronounced role for consultancies and think tanks as both key sources of policy ideas and advice, and as technical experts that government must go to given policy capacity shortages after years of budget cuts and austerity measures (Keele Reference Keele2019; Marsh and Stone, Reference Marsh, Stone, Stone and Denham2004; Saint-Martin Reference Saint-Martin2004; van den Berg et al. Reference van den Berg, Howlett, Migone, Howard, Pemer and Gunter2019; Weiss Reference Weiss2018). In Australia, for example, van den Berg et al. (Reference van den Berg, Howlett, Migone, Howard, Pemer and Gunter2019) identify a continuous rise in the scope use of consultants for policy-related issues by the federal government, as well as a change in their substantial role, concurrent with stagnant levels of in-house staffing (see also: Marciano Reference Marciano2022), similar to the rise of the role and influence of consultants in Britain as well (Weiss Reference Weiss2018).

Finally, externalisation in this context relates primarily in literature to governments using external advisory sources (e.g. consulting firms and think tanks). However, it is also relevant in understanding policy advice fragmentation and polycentrism that stems from where authority, as well as policy-relevant knowledge, is distributed in a variety of governance arrangements (Diamond Reference Diamond2020a; Craft and Howlett Reference Craft and Howlett2012). This fragmentation is linked to calls for greater government transparency or “government open by default” and the rise of various forms of “co-production” in policymaking, which have become established ways of working in all four countries (Bovaird and Loeffler Reference Bovaird and Loeffler2013; Ryan Reference Ryan2012, Vaillancourt Reference Vaillancourt2013). It also relates to cases when various private authority actors generate and apply policy advice and set standards and rules, and self-regulate on a range of issues in areas like forestry and natural resources as well as biotechnology and energy industries (Bell and Hindmoor, Reference Bell and Hindmoor2011; Skogstad Reference Skogstad2003). Some private authority work has raised the prospect of “governance spheres” where policy issues and authority from public and private sources are more fluid than in traditional state-led policymaking. For example, “ECOLOGO” product certification began by the Government of Canada but was subsequently delegated to a private standard setter, UL Environment (Cashore et al. Reference Cashore, Knudsen, Moon and van der Ven2021). In such cases, policy-relevant advice and authority accumulate outside of the government realm, raising implications for PAS management which have yet to be fully confronted. The erosion of government’s authority and expertise in these areas limit government discretion in managing these potential advice sources.

Politicising PAS

Political actors have adopted a range of practices and initiated reforms serving to politicise PAS. Initial focus on politicisation in Westminster systems emphasised attempts by governments to politicise public services appointment of senior officials. All four public services have to varying degrees pushed back and sought to ensure public service independence and professionalism. Comparative analysis reveals that, generally, Australia and Canada have evolved to a more political form of appointments with the executive able to use its influence and shape senior public service appointments (Bourgault Reference Bourgault, Bourgault and Dunn2014; Brock and Shepherd Reference Brock and Shepherd2021; Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020). Whereas in Britain, and particularly New Zealand, the public service remains dominant in the appointment process which has been institutionalised to prevent interference (see Boston and Halligan Reference Boston, Halligan, Bakvis and Jarvis2012; Halligan Reference Halligan2020).

Others have also examined the phenomenon of the permanent or constant campaign mode that has become a feature of contemporary government in these countries. The permanent campaign has been argued to politicise PAS and government more generally given it involves heightened compression of the policymaking cycle, where a handful of key electoral and partisan policy agenda items of government are privileged and expedited through the machinery of government. The remaining day-to-day or “housekeeping” policy matters are left largely to the public service (Craft Reference Craft, Giasson and Esselment2017; Diamond Reference Diamond2018). Comparatively, New Zealand and Australia have now become more accustomed to permanent campaigning given the prominence of minority and coalition governments. Electoral reforms adopted in New Zealand in 1996 have led to a significantly more negotiated form of PAS where governments and their advisers must negotiate, bargain, and coordinate amongst governing and parliamentary factions (Mazey and Richardson Reference Mazey and Richardson2021; Eichbaum and Shaw Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2010; Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020). Canada and Britain have also grappled with formal institutional and machinery of government questions, and the partisan political management realities of minority and coalition government. Policy advice in these contexts often becomes oriented to short-term and partisan calculus (Aucoin Reference Aucoin2012; Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020; Diamond Reference Diamond2018; Van Onselen and Errington Reference Van Onselen and Errington2007).

Centralising and pulling on central levers

The centre of government has become a first port of call for prime ministers seeking to manage PAS. The centre in all four countries includes the three central agencies that together manage finance (budget and/or fiscal policy), enterprise-wide public service management functions (treasury board secretariat or public service commissions) and support the cabinet and/or prime minister (e.g. Privy Council Office or Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet). Also included in the centre are the “private offices” of prime minister’s offices (e.g. No. 10 in Britain or PMO in Canada) that are staffed by the partisan political appointees and in some cases select public servants. The centre is relevant to PAS management given that these organisations provide considerable span of control over the allocation of resources, planning and whole of government policy and administration setting, and shape the primary decision-making processes of cabinet and prime ministers (Craft and Wilson Reference Craft, Wilson, Dobuzinskis and Howlett2018; Craft Reference Craft2016; Esselment et al. Reference Esselment, Lees-Marshment and Marland2014; Weller Reference Weller2018). It is also unquestionably important in its responsibilities and abilities for ensuring coherence and coordination of the government’s policy and management agenda (Dahlstrom et al. Reference Dahlstrom, Peters and Pierre2011).

The rise and fall of specialised units, particularly in Britain as was led by PM Blair in the early 2000s, with the explicit remit of providing specialised policy advice to government, including policy, strategy, innovation, or delivery units, have been stood up in and around the centre to provide additional capacity to prime ministers and cabinet to better coordinate policy (Lindquist and Eichbaum Reference Lindquist and Eichbaum2016). They are also used for additional policy and management capacity and to better contest and coordinate the policy work occurring in and around the core executive, often with a focus on implementation or “delivery” (Diamond Reference Diamond2020b; Gold Reference Gold2014, Reference Gold2017; Lindquist Reference Lindquist2006). The centre has received ongoing scrutiny, especially the role and function of prime ministerial private offices, but also the perceived trend of the concentration of power at the centre of governments by prime ministers and their courts. Australia and particularly Canada have also been well documented for their propensities for prime ministerial centralisation. This is in part because in the Westminster politico-admin system there are tremendous flexibilities and few restraints on prime ministers’ abilities to use the authorities and resources of the centre of government (budgets, machinery of government, and appointments) to command and cajole others to move in their desired direction (Rhodes et al. Reference Rhodes, Wanna and Weller2009; Savoie Reference Savoie2003; Tiernan Reference Tiernan2006, Reference Tiernan2007; Weller Reference Weller2018; Craft and Wilson Reference Craft, Wilson, Dobuzinskis and Howlett2018). This was perhaps most clearly illustrated by Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison who secretly appointed himself co-minister of five portfolios including Finance, Treasury, and Home Affairs and created committees that included only himself to centralise power and his ability to exercise it. The need to respond comprehensively to the COVID-19 pandemic was cited by PM Morrison as what triggered this decision (Butler Reference Butler2022; Remeikis Reference Remeikis2022).

Leaning on partisan advisers and expanding ministerial “private” offices

Clear and decisive use of partisan advisers as part of an attempt to authoritatively manage PAS is widely acknowledged (Eichbaum and Shaw Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2008). Important distinctions characterise the organisation and number of partisan advisers in these cases with Canadian and Australian governments having separate ministerial offices staffed with partisan appointees, while New Zealand and Britain have opted for hybrid offices where ministers can only appoint two to three partisan advisers who work alongside career public servants. Attempts by the 2013 UK coalition government saw attempts to experiment with extended ministerial offices. These were designed to provide new policy capacity by way of a minister’s personally selected external appointment to short-term civil service contracts to provide policy support, progress chasing, and strategic advice (Cabinet Office 2013; Paun Reference Paun2013). However, take up was low given rigid rules and heavy No 10 oversight and the experiment was quickly shuttered (Maley Reference Maley2018). More commonly, PAS management has seen authoritative forms via the greatly expanded use of ministers’ office partisan advisers, particularly in Australia and Canada. While original attention was focused on the influence and role of Prime Minister’s office staff their numbers have remained relatively flat across the four countries over time while explosive growth among ministers’ office staff, particularly in Australia and Canada, has drawn more scrutiny (Pickering et al. Reference Pickering, Craft and Brans2023; Maley Reference Maley2015). Not only for their importance in advising ministers on matters of policy and politics but as important tools in modern political and policy management approaches for prime ministers and cabinet who are seeking policy and political coherence within government and with key stakeholders outside of it (Eichbaum and Shaw Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2010; Craft Reference Craft2015; Dahlstom et al. Reference Dahlstrom, Peters and Pierre2011).

Prioritising implementation and “delivery”

Governments have also been very active at managing PAS by seeking to add resources and configure it to provide policy advice that facilitates effective implementation or “delivery” of key government priorities. Governments have always been sensitive to the need to demonstrate their ability to effectively govern, as is evidenced by a long track record of managing for results and results-based approaches to governing (Aucoin Reference Aucoin1995; Lindquist and Eichbaum Reference Lindquist and Eichbaum2016). From a PAS perspective, there have been more recent attempts to experiment actively with organisational and behavioural tactics (centralised delivery/implementation units and performance management) to ramp up government’s ability to control and succeed in the delivery of government policy. Typically, centrally administered, but at times extending to ministers in departments or partisan advisers, governments use their agency and discretion to take a more “hands-on” approach to the operational aspects of governing. This serves to emphasise the implementation rather than the formulation of policy with corresponding shifts in advisory practices focused on “what works” and “stock takes” of how government policy initiatives are advancing. Britain’s “deliverology” approach being the most widely known, and clearly representing an authoritative PAS management form whereby implementation-related advice was prioritised and emphasised in governance, has been emulated. Results and delivery units of various guises are now an established instruments for governments seeking to engage more forcefully in directing PAS and to ensure promises made translate into promises kept across these four anglophone cases, but with mixed reviews of their assessments to secure results (Gold Reference Gold2014; Lindquist Reference Lindquist2006; Wanna Reference Wanna2006).

Nature and scope of PAS management practices

Above, we outlined broad forms of PAS management. Our analysis charts a diversity in PAS management in practice yet is also in line with our theoretical propositions, whereby fundamentally PAS management involves elected governments’ agency to engage in managing PAS, and the level of discretion they have to do so. Within the authoritative form, governments have used their agency and considerable discretion to manage PAS as seen with public service capacity building efforts in New Zealand under Arden; through the attempt to manage PAS more forcefully through the creation of a delivery units under Blair in the Britain; or through the concentration of power exemplified by the uncharted secret self-appointment of PM Morrison to five additional policy portfolios. We have also showcased the practices associated with dependent forms of PAS management, which have been most clearly manifested in the acute examples of private sector consultant use in Britain for Brexit purposes, but also via ongoing reliance on consultants in Australia required by governments for policymaking. In laissez-faire management form we see a more hands-off or status quo approach to the use of first ministers’ partisan advisers with virtually flat numbers and similar functions across the cases, while ministerial office partisan advisers have swelled (Pickering et al. Reference Pickering, Craft and Brans2023). More generally, while all four countries have demonstrated that centralisation of power around first ministers or heavy use of central government levers, there is widespread recognition that governments have limited capacity to manage everything. Rather, governments in these four countries have, through PAS management, often sought to focus and prioritise leaving many policy matters to lumber along under the status quo with little to no active government management unless required (Savoie Reference Savoy1999; Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020; Diamond Reference Diamond2018; Weller Reference Weller2018). This is exemplified through increased adoption of permanent campaigning and centralised delivery units. With the former prioritising policy advice to secure governments’ political and electoral priorities, and the latter intended to manage PAS to focus on a specific set of policy priorities as seen under Blair in Britain and Trudeau in Canada (Lindquist and Eichbaum Reference Lindquist and Eichbaum2016). Finally, we identify instances of absent management form, as we drew on examples from private authority where governments may be absent from market, industry, or nonprofit standard and rule setting. In these instances, governments can become involved as issues move to or from governance spheres where governments are active (Cashore et al. Reference Cashore, Knudsen, Moon and van der Ven2021). We also flag this management form as an area for further study, given the limited attention paid to it so far in secondary literature.

Understanding the role of agency and discretion can further help in better theorising and empirically studying the operational practice of PAS management. Even when governments choose to engage actively and have discretion to do it, there are questions about their agency over the scope of PAS management. New Public Management reforms stand out as the most prominent example where governments implemented broad and far-reaching changes to PAS configuration and practice (Aucoin Reference Aucoin1995; Halligan Reference Halligan2020). Our analysis points to other examples such as the practice of expanding the use of ministerial partisan advisers in Australia and Canada with major implications for how policy advising and policymaking are now undertaken (Craft Reference Craft2016; Eichbaum and Shaw Reference Eichbaum and Shaw2010; Pickering et al. Reference Pickering, Craft and Brans2023). Likewise, the institutionalised reliance on private consultants for essential policy advisory activity in Australia reflects a broader PAS management application (van den Berg et al. Reference van den Berg, Howlett, Migone, Howard, Pemer and Gunter2019). In contrast, PAS management in these countries clearly includes governments adopting a more focused scope of PAS management (see Table 3). That is, targeting specific types of advisers, certain advisory practices, or focused on particular policy sectors or issues. A clear example in Britain was the targeted use of consultants for Brexit planning and execution, in Canada, Harper government’s shuttering of the national roundtable on the environment and the economy, or the creation of independent budget officers in some of the cases.

Table 3. Nature and scope of PAS management practices

Source: Authors.

Additionally, the proactive or reactive nature of PAS management also reveals how agency and discretion come into play. In many cases, policymakers may come to office with the decision to proactively engage in PAS management. Classic and well established examples include the Thatcher and Mulroney governments clear proactive and broad approaches to restructuring advisory practices in Britain and Canada (Savoie Reference Savoie1994; Aucoin Reference Aucoin1995). PM Ardern’s decision in 2018, immediately after coming to office, to issue clear instructions and resources to rebuild the public service policy capacity and reduce reliance on consultancies is another. At the same time, understanding the nature of PAS management further reveals the complexity of how agency is applied. Decisionmakers are often compelled to engage in managing the operation of PAS reactively due to policy failures and crises, external shocks, or political pressures or performance data. In such cases, their agency is complicated by the changing context. The decision to extensively draw on consultants to temporarily expand policy capacity in response to COVID-19 pandemic in all four cases represents such a case (Lewis 2021; Vogelpohl et al. Reference Vogelpohl, Hurl, Howard, Marciano, Purandared and Sturdy2022); as well as the choice in Britain to drew heavily on external expertise in Brexit planning or Australia’s PM Morrison’s decision to centralise power and expertise during the crisis. Such crisis conditions expand decision-makers’ agency in applying such changes, because of the expectation for a swift and sufficient response, and a temporary relaxation of institutional constraints associated with crises (Capoccia and Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007). Nevertheless, decisionmakers then become materially constrained by the available level of policy capacity within system actors and by the readiness and abilities of advisory sources to organise quickly and sufficiently.

Conclusion: Implications for PAS management

This article has developed the concept of PAS management – the ways in which governments seek to optimise PAS to better meet their objectives or to address their limitations. It further identifies four PAS management forms, determined by the level of government involvement and its level of discretion to affect PAS. Analysing the PAS management experiences of the four anglophone Westminster countries demonstrates that there is a range of practices being deployed by governments. They allocate resources, enhance or reduce capacity, or the number and types of advisers or alter key advisory structures and processes. The analysis offered here helps us in identifying and explicitly linking such practices with the role of agency and discretion in the forms of PAS management. It also highlights important variation in the scope of governments’ attempts to manage PAS more broadly or in more targeted fashions, and that PAS management can have proactive or reactive dimensions.

The work presented here provides an initial overview and analysis of PAS management forms. Our analysis has relied on anglophone and particularly Westminster style governments and further supports the importance of within-administrative tradition variation (Craft and Halligan Reference Craft and Halligan2020). The theory building and analysis are however pertinent to other administrative traditions such as the Napoleonic, Germanic, and Scandinavian among others where discretion and agency may be conceived of and operate differently given differences beliefs, practices, and traditions linked to political-administrative relations, management and administrative practices, and institutional and governance contexts (see Peters Reference Peters2021). More generally, additional research is needed that is aimed at understanding how PAS management forms are put to action, what triggers them, and what is the shape they take in different contexts. The following questions are important: What compels governments to use these management forms – what are conditions under which they are likely to utilise each approach, and when are they likely to move from one approach to another? Considering the limited attention placed on power to date in the study of PAS, more research needs to be directed to how the agency and power of advisory actors themselves should be considered and integrated into the analysis of PAS management forms. This is especially important in areas in advisory systems where governments have less discretion to intervene including international and transnational organisations. Finally, while the typologies presented in this article are applied to issue and contextspecific PAS management cases, we recognise that in practice governments are managing multiple policy issues and that circumstances may dictate the concurrent use of multiple approaches and varied practices. We draw attention to the need to further theorise and study the PAS management mixes that governments adopt to do so, as well as what compels governments to shift these mixes or move from one approach to another.

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.