INTRODUCTION

Patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) have a variety of non-motor symptoms that are becoming more recognized.Reference Chaudhuri, Martinez-Martin and Schapira 1 Among these are such oculovisual symptoms as dry eyes,Reference Biousse, Skibell, Watts, Loupe, Drews-Botsch and Newman 2 difficulty reading and double vision,Reference Chaudhuri, Martinez-Martin and Schapira 1 , Reference Archibald, Clarke, Mosimann and Burn 3 which can affect quality of life in PD patients. Alterations in some visual functions have also been documented in PD, among which is convergence insufficiency (CI), a decreased ability to converge both eyes on an object located at a near distance.Reference Biousse, Skibell, Watts, Loupe, Drews-Botsch and Newman 2 When present, CI can lead to blurred vision, tearing, ocular fatigue and double vision, and make it difficult or impossible for a person to read comfortably. This can be detrimental to many aspects of a person’s life in modern countries, where the ability to read efficiently permeates the educational, working or even recreational environments.

Over the last two decades, a few studies have addressed CI-type symptomatology in individuals with PD.Reference Biousse, Skibell, Watts, Loupe, Drews-Botsch and Newman 2 - Reference Almer, Klein, Marsh, Gerstenhaber and Repka 6 The CI-related symptoms most frequently cited in PD were difficulty reading and diplopia. All of these studies, however, were conducted on limited numbers of participants, and none used a questionnaire developed and validated for CI. Our objective was to estimate the prevalence of CI-type symptomatology, in a systematic fashion, in a large population of individuals with PD, compared to age-matched controls.

METHODS

This study was conducted in collaboration with the Institut Universitaire de Gériatrie de Montréal (IUGM), the Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM) and the Montreal General Hospital (MGH). The study protocol was approved by the research ethics committee of each of the three hospitals, and the study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants signed an informed consent in accordance with the requirements of the various ethics committees.

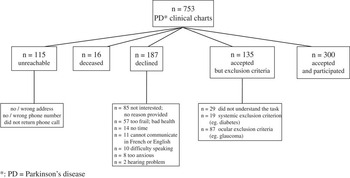

A total of 300 participants ≥50 years of age with a clinical diagnosis of PD were recruited from the movement disorder clinics (MDCs) of the neurology departments at the CHUM and the MGH (Figure 1). They were each matched for age (±5 years) and opposite sex to a control participant without PD. Opposite sex was used in trying to facilitate recruitment in case spouses would be interested in participating and knowing that a gender-related prevalence of CI had not been documented.Reference Scheiman, Gwiazda and Li 7 A control was chosen among the spouse, family or friends of each participant with PD, and if none was found, the control was then recruited from the bank of participants at the IUGM. A few controls had to be recruited from a third alternative source, that is, the Clinique Universitaire de la Vision de l’Université de Montréal. The matching was done with a spouse (20.0%), a family member (0.3%) or another unrelated adult (79.7%).

Figure 1 Recruitment of Parkinson’s disease participants.

A review of clinical charts excluded individuals where binocular dysfunction other than CI (e.g., strabismus), known ocular disease/decreased visual acuity (e.g., glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, amblyopia), other forms of neurodegenerative disease (e.g., Huntington’s disease, dementia) or diseases likely to affect the extraocular muscles (e.g., Graves’ thyroid disease, myasthenia gravis) or visual function (e.g., diabetes) were reported.

Individuals who met the study criteria based on their clinical chart review were contacted by mail and provided the following documents: a letter from a research neurologist explaining the study, ethics documents including information and the consent form, and answer codes for the Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS–15) questionnaire. Approximately 10 days later, the research assistant (RA) called each individual to answer any questions and determine if they were interested in taking part in the study. If individuals did not want to participate, no other contacts were made. If a person was interested in participating, he/she was first allowed to ask any questions related to the study, and then was given the choice to answer the phone questionnaires right away or at any other convenient time. The participant was asked to sign the consent form and mail it back to the research team, according to each ethics committee’s requirements.

Phone interviews lasted about 30 minutes on average. Four questionnaires were filled out over the phone by the RA, in the following order: (1) the Adult Lifestyles Function Interview (ALFI), (2) an ocular history, (3) a general health questionnaire, and (4) the CISS–15. The first three questionnaires were employed to further assess the eligibility of the study participants. The ALFI is a telephone-administered version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), which comprises 22 items aimed at screening for cognitive impairment.Reference Roccaforte, Burke, Bayer and Wengel 8 We designated a score below 14 as an exclusionary criterion.Reference Quail, Addona, Wolfson, Podoba, Lévesque and Dupuis 9 The ocular history and general health questionnaires were developed by the clinician/researcher specialists on our team and designed to ensure that the conditions specified by our inclusion/exclusion criteria were met. The CISS–15 questionnaireReference Scheiman, Mitchell and Cotter 10 was designed to estimate the frequency and severity of CI symptoms and has been shown to be a valid and reliable instrument for CI treatment outcomes.Reference Rouse, Borsting and Mitchell 11 It contains 15 items with a 5-digit scale from 0 to 4. The response to each item expresses the frequency of symptom occurrence (0=never, 4=always), and the potential total score, obtained by adding the individual response scores, ranges from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. A score of 21 has been shown to distinguish between symptomatic (≥21) and asymptomatic (<21) individuals,Reference Rouse, Borsting and Mitchell 11 and so it served as the cutoff for CI-type symptomatology in this study. All individuals who consented to participate were asked to answer the four questionnaires over the phone. Some had to be excluded from the main study because they indicated the presence of a binocular dysfunction other than CI or another ocular disease. Their data were kept and entered into a different Excel spreadsheet.

The statistical average differences and percentage differences between two independent groups were respectively determined using Student’s t test, with the chi-square level of significance set at 0.05.

RESULTS

The PD group included 121 women and 179 men with an average age of 67.3±8.9 years, while the control group comprised 179 women and 121 men with an average age of 67.2±8.7 years (p>0.05). The participants with PD had an average of 2.9±1.7 diseases and were taking 5.1±2.8 medications (including 2.3±1.1 PD-related medications), while the controls had an average of 1.6±1.4 diseases and were taking 2.1±2.2 medications (p<0.001). The mean duration of PD was 8.4±5.9 years. The group average score on the ALFI was 19.5±2.3 for PD participants and 20.3±1.9 for controls (p=0.001). The group average score on the CISS–15 was 15.7±9.3 for PD participants and 10.3±7.0 for controls (p=0.001). Some 29.3% (n=88) of PD participants and 7.3% (n=22) of controls (p=0.001) had scores on the CISS–15 of ≥21.

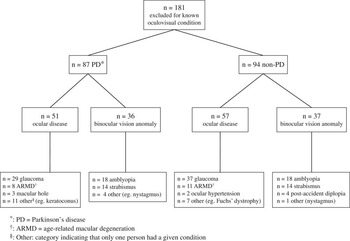

A total of 87 participants with (36 women) and 94 without (68 women) PD were excluded from the main study for known ocular disease (n=51 PD, n=57 controls) or a binocular vision anomaly other than CI (n=36 PD, n=37 controls) (Figure 2). The average age was 70.5±9.7 years for PD participants and 70.7±8.9 years for the controls (p>0.05). The participants with PD had an average of 3.8±2.0 diseases and were taking 5.9±2.6 medications (including 2.3±1.1 PD-related medications), while the controls had an average of 2.0±1.9 diseases and were taking 2.5±2.0 medications (p<0.01). The mean duration of PD was 9.0±6.3 years. The group average score on the ALFI was 18.9±2.4 for PD participants and 20.1±1.8 for controls (p=0.001). The group average score on the CISS–15 was 19.3±11.2 for PD participants and 13.7±9.2 for controls (p=0.001). A score on the CISS–15 of ≥21 was obtained for 39.1% (n=34) of participants with and 19.1% (n=18) without PD (p=0.01).

Figure 2 Oculovisual conditions excluding participants.

An analysis of individual CISS symptoms in participants with positive CI symptomatology revealed that “eyes feel tired” and “eyes feel uncomfortable” when reading or doing close work stood out the most for PD and non-PD participants (Table 1). Those that emerged least were “headache” for “included/excluded” PD and “included” non-PD participants, and “double vision” for “excluded” non-PD participants.

Table 1 Occurrence/severity of the most and least frequent symptoms in included/excluded participants having subjective convergence insufficiency

CI=convergence insufficiency; PD=Parkinson’s disease.

DISCUSSION

The findings of our study indicate that CI-type visual symptomatology: (1) is higher in PD than in non-PD participants; (2) remains higher in PD versus non-PD participants, for those having a known oculovisual condition; and (3) is higher in PD and non-PD participants having versus not having a known oculovisual condition. Overall, these results indicate that having a known oculovisual condition is accompanied by a high prevalence of visual symptoms, and they further suggest that having PD per se places individuals with the disease at higher risk for visual symptomatology.

The prevalence of CI-type visual symptomatology in individuals with PD (29.3%) was found to be four times greater than for those without PD (7.3%) and two times higher in PD (39.1%) versus non-PD (19.1%) for individuals with a preexisting oculovisual condition. These results are rather strong and deserve some interpretation. It is important to point out that the CISS–15 questionnaire employed in the present study was originally designed by experts to address the symptoms most likely to be present in individuals having a diagnosis of CI, and to serve as an outcome measure of success for CI treatment. In other words, this questionnaire was to be used in people already with a diagnosis of CI and was not meant to serve as a screening tool for CI. Knowing this limitation, the CISS–15 questionnaire was utilized here since it was the only existing validated tool to at least enquire about “CI-type” symptoms that could be used in a large number of participants. The similarity of symptoms found in CI and in other oculovisual conditions could have increased the prevalence of symptoms found in the present study. The elevation of CISS scores in those having a known oculovisual condition is consistent with this. The present results confirm those obtained in our previous reportReference Irving, Chriqui and Law 12 indicating that “eyes feel tired or uncomfortable while reading or doing close work” is a more prevalent/severe symptom than “double vision” in that population, and they suggest that this item could be added in non-motor screens to better identify PD individuals with vision problems. It is also important to point out that our data showing a higher prevalence of CI-type symptomatology in PD does not indicate that a diagnosis of CI is more prevalent in PD. Further research that would include a complete eye exam is needed to address this issue and has been pursued in view of the strength of the results obtained here. Although the limited resources available for the present study prevented the provision of an eye exam for all participants, we have been able to perform eye exams in a subset of 80 PD and 80 non-PD participants. Results from this research have shown that a clinical diagnosis of CI is in fact more prevalent in PD (43.8%) versus non-PD (16.3%) participants.Reference Irving, Chriqui and Law 12 Taken together, these prevalence data underline the importance of evaluating oculovisual symptomatology and CI in individuals with PD. Oculovisual symptomatology being particularly prevalent in PD, it is important to provide these individuals with regular eye exams and treat any underlying oculovisual condition if at all possible. If symptoms were to be linked with a diagnosis of CI in patients experiencing significant discomfort and decreased quality of life, then it could be possible to offer them some form of treatment, such as prism or orthoptic therapy. These therapies would have to be decided based on the stability of the clinical findings, however, and if judged of potential benefit, would have to be well-explained and reserved to highly motivated patients, since they are known to work for older individualsReference Teitelbaum, Pang and Krall 13 - Reference Wick 15 but have not been formally evaluated in PD.

Another limitation to this study is that we could not stage the severity of PD since the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale scores or Hoehn and Yahr staging were not available. Although this does not allow a comparison between severity of PD and severity of CI-type symptomatology, it does not change the results that indicate a higher prevalence of CI-type symptomatology in PD versus non-PD individuals. In addition, using clinical charts to identify and recruit PD participants may have affected the population representativity of our sample, but it would be difficult to offer an opinion on the direction or magnitude of any potential selection bias. However, the strength of these data suggests that similar results would likely have been obtained in another PD population recruited under a different mode of selection.

Despite these acknowledged limitations, the higher prevalence of symptoms found in those having PD certainly stresses the impact the disease has on the oculovisual system. It has been reported that ocular changes take place early on in the course of PD, likely a result of the disease itself.Reference Biousse, Skibell, Watts, Loupe, Drews-Botsch and Newman 2 Our results further suggest that particular care should be provided to patients with PD during an eye exam, in order to verify the extent of their symptoms and address them if at all possible. Similarly, as mentioned by Chaudhuri et al.,Reference Chaudhuri, Martinez-Martin and Schapira 1 neurologists should also pay special attention to non-motor symptoms, including the oculovisual ones, in the care of their PD patients. This is particularly important knowing that PD medications can have a positive effect on visual function.Reference Almer, Klein, Marsh, Gerstenhaber and Repka 6 , Reference Racette, Gokden, Tychsen and Perlmutter 16 To that effect, it is worth mentioning that daytime somnolence has been linked with diplopia.Reference Archibald, Clarke, Mosimann and Burn 3 The authors suggested that drowsiness may alter the ability to maintain fusion,Reference Archibald, Clarke, Mosimann and Burn 3 a condition that may or may not be helped by PD medications, depending on whether the drowsiness is induced by a symptomatic undiagnosed binocular vision problem or the medication itself, or is due directly to the disease process itself (i.e., degeneration of wake-promoting nuclei). It is interesting to add that the issue of how ocular pathology contributes to disability in PD has been raised in a review paper addressing the retina in PD.Reference Archibald, Clarke, Mosimann and Burn 17 Although our results cannot provide an answer to that question, they certainly demonstrate that symptoms are higher in the presence of an ocular pathology or a visual dysfunction, and they reinforce the importance of pursuing research aimed at better understanding vision in PD.

In conclusion, our data have shown that convergence insufficiency-type symptomatology is higher in individuals with Parkinson’s disease having or not having a concurrent visual dysfunction or ocular pathology. Our results further stress the importance of providing regular eye exams for individuals affected by this disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Comité Aviseur pour la Recherche Clinique (CAREC) at the IUGM, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, MOP-123462) and the Canadian Optometric Education Trust Fund (COETF). These funding sources had no involvement in the research performed or the research report. The authors thank the team of neurologists and personnel at the movement disorder clinic; the “Gestion de l’Information” and the “Archive” departments of the CHUM; and the team of neurologists and personnel at the neurology department of the MGH; as well as Milena Dimitrova.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Statement of Authorship

Conception of the project (EC, MJK, BSL, MP, ELI, HK); data acquisition (CL, EC); expertise in various aspects of participant recruitment (MJK, MP, ELI, RP, SC, HK); writing and critical review of the manuscript (all coauthors); and statistical analyses (BSL).

Disclosures

Marie-Jeanne Kergoat has the following disclosures: CAREC–IUGM: grant recipient, research grant; CIHR: grant recipient, research grant; Alzheimer Society of Canada: grant recipient, research grant; FRSQ–Pfizer: grant recipient, research grant; CCNA, grant recipient, research grant.

Estefania Chriqui, Bernard-Simon Leclerc and Caroline Law do not have anything to disclose.

Michel Panisset has the following disclosures: Merz: advisory board, honoraria; Allegan: advisory board, honoraria; Medtronic: independent investigator, research support.

Elizabeth Irving has the following disclosures: CIHR, co-investigator, research grant; NSERC, principal investigator; Canadian Optometric Education Trust Fund: research grant; University of Waterloo Research Incentive Fund: research grant; CIMVHR, research contract.

Ronald Postuma has the following disclosures: Roche: consultant, honoraria; CIHR, grantee, grant; FRSQ, grantee, grant; Parkinson Society of Canada: grantee, grant; Michael J. Fox Foundation: grantee, grant; Weston Garfield Foundation: grantee, grant; Biogen: consultant, honoraria; Biotie: consultant, honoraria; Teva: speaker, honoraria; Webster: grantee, grant.

Sylvain Chouinard has the following disclosures: Abbie: advisor, consulting fees; Merz: advisor, consulting fees; Allergan: advisor, consulting fees.

Hélène Kergoat has the following disclosures: COETF: grant recipient, research grant; CAREC–IUGM: grant recipient, research grant; NSERC, grant recipient, research grant; CIHR, grant recipient, research grant; Alzheimer Society of Canada: grant recipient, research grant.