Psychological therapists in the National Health Service (NHS) see patients from a range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Women are more likely than men to access treatment for anxiety and depression 1 and, to encourage uptake, address health inequalities and optimise treatment outcomes, services must be able to meet the practical and cultural needs of women from minoritised ethnic groups. While guidance supporting therapists to deliver treatment for diverse groups exists, Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2,3 inequalities in access and experiences of treatment for people from minoritised ethnic communities persist, Reference Ajayi (Sotubo)4,Reference Sharland, Rzepnicka, Schneider, Finning, Pawelek and Saunders5 as do differences in outcomes. Reference Arundell, Saunders, Lewis, Stott, Singh and Jena6

The concept of racial or ethnic difference that has influenced healthcare research and practice throughout history may have contributed to discriminatory practices, stigmatisation and health outcome disparities for people from minoritised ethnic groups. Reference Bryant, Jordan and Clark7 Mental health inequalities experienced by minoritised ethnic communities may be due to lack of patient awareness of, and pathways to, treatment, Reference Bogenschutz8–Reference Memon, Taylor, Abel, Collins, Campbell and Porter10 the suitability of available treatments Reference Benish, Quintana and Wampold11,Reference Sekhon, Cartwright and Francis12 and mental health stigma. Reference Memon, Taylor, Abel, Collins, Campbell and Porter10,Reference Watson, Harrop, Walton, Young and Soltani13,Reference Knifton14 Work to tackle ethnic inequalities has included a strong focus on cultural adaptations to treatment, which have been shown to benefit people from minoritised ethnic groups. Reference Arundell, Barnett, Buckman, Saunders and Pilling15 Suggestions in regard to improving care for these groups have included better mental health education and awareness, Reference Silverwood, Nash, Chew-Graham, Walsh-House, Sumathipala and Bartlam16,Reference Bhui, Aslam, Palinski, McCabe, Johnson and Weich17 cultural competence training for practitioners Reference Kirmayer18,Reference Kirmayer and Jarvis19 and better service integration (e.g. different healthcare professionals working more closely together). Reference Silverwood, Nash, Chew-Graham, Walsh-House, Sumathipala and Bartlam16

Qualitative research exploring patients’ experiences of mental health care has helped to understand the challenges faced by minoritised ethnic communities, Reference Memon, Taylor, Abel, Collins, Campbell and Porter10 and findings from research exploring women’s experiences of perinatal mental health treatment demonstrate the benefits of this work. Reference Watson, Harrop, Walton, Young and Soltani13,Reference Smith, Lawrence, Sadler and Easter20 In fact, a considerable amount of research on women’s mental health outcomes is focused on the efficacy of interventions to address postpartum- and pregnancy-related mental health conditions. Reference Megnin-Viggars, Symington, Howard and Pilling21–Reference Shi and MacBeth23 Given that women are more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety and depression and that they are more likely to access treatment and comply with it once started, Reference Riecher-Rössler24 it is vital to ensure that services are offering the best possible chance for optimal outcomes for women who seek treatment for these conditions. What is known about how a person’s ethnic and gender identity intersect to influence their life experiences, Reference Barber, Gronholm, Ahuja, Rüsch and Thornicroft25–Reference Crenshaw28 mental health access, treatment Reference Riecher-Rössler24,Reference Gagné, Vasiliadis and Préville29,Reference Corrigan, Druss and Perlick30 and outcomes, Reference Arundell, Saunders, Lewis, Stott, Singh and Jena6 as well as the recognised importance of culture and cultural influences on these factors, Reference Corrigan, Druss and Perlick30,Reference Fernando31 means that a focus on what can be done to best support women from minoritised ethnic communities to benefit from mental health treatment is of vital importance.

Exploring the experiences of practitioners can also provide important insights that may help to remedy inequalities Reference Bains, Bicknell, Jovanović, Conneely, McCabe and Copello32 – for example, by understanding the experiences of practitioners Reference Ashcroft, Donnelly, Dancey, Gill, Lam and Kourgiantakis33,Reference Pope, Redsell, Houghton and Matvienko-Sikar34 and their views on how treatment can better meet the needs of people from diverse backgrounds. Reference Faheem35,Reference Mollah, Antoniades, Lafeer and Brijnath36 A contemporary exploration of practitioners’ experiences providing therapy to women from diverse ethnic backgrounds is warranted, especially since the proliferation of cultural sensitivity training and increased focus on addressing ethnic inequalities in mental healthcare in recent years. Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2

This study aimed to explore therapists’ experiences of providing psychological treatment to women from minoritised ethnic communities, including their insights on adaptations made at the delivery, content and wider organisational levels. The study intended to gather suggestions from therapists about how treatment could be improved for women from minoritised ethnic communities. This research was conducted alongside another piece of qualitative research that explored experiences of care and suggested improvements from the perspectives of female patients. Reference Arundell, Saunders, Barnett, Leibowitz, Buckman and Pilling37 Exploration of treatment experiences and improvements from the perspectives of both clinicians and patients is useful in regard to a more holistic understanding of issues and care improvement solutions.

Method

Study design and theoretical framework

A qualitative study was conducted between January and April 2023, using semi-structured interviews with psychological well-being practitioners (PWPs; professionals trained to assess and support people with common mental health problems in the NHS) and high-intensity therapists (HITs; professionals with further training who are equipped and accredited to deliver high-intensity therapies to people with more complex needs in the NHS). A contextualist approach Reference Braun and Clarke38 was used to address questions about NHS Talking Therapies for anxiety and depression (NHS TTad) treatment from the perspectives of therapists treating women from minoritised ethnic groups. Interpretations should be considered within the perspective of the lead author, a female PhD candidate of mixed ethnicity who is interested in ethnic discrepancies in mental health care. Reporting was in line with COREQ Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig39 (Supplementary File 2 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.36).

Setting

The study was conducted across two NHS TTad services serving the boroughs of Camden and Islington in London, UK. The ethnic diversity of the population across these boroughs 40,41 meant that they were an ideal choice within which to explore therapists’ experiences of treating people from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the services using purposive sampling. Study information was circulated via email to HITs and PWPs, and expressions of interest were invited from those who met the following eligibility criteria:

-

(a) qualified psychological therapist (HIT or PWP) working in NHS TTad services in Camden or Islington;

-

(b) experience practising in any NHS TTad service for at least 6 months;

-

(c) experience treating women from minoritised ethnic communities.

Therapists who expressed interest were contacted by email and sent a copy of the Participant Information Sheet. Consent was taken electronically via form (study materials are provided in Supplementary File 1).

Development of interview questions

Potential questions for therapists, informed by contemporary literature and research findings, were brought for discussion to the Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Staff Working Group at the Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust. Following this, a further draft was developed drawing on developments in cultural adaptations research. Reference Arundell, Barnett, Buckman, Saunders and Pilling15 The BAME Staff Working Group and the Trust’s Service User Advisory Group were invited to comment via email on the questions, the structure of the interview schedule, missing discussion topics and any other comments. A final draft of the interview schedule (Supplementary File 1) was agreed between the research team (L.-L.A., S.P. and J.L.).

Procedure

Participants took part in individual semi-structured interviews with one researcher (L.-L.A.). Interviews lasted between 45 and 60 min and were held, recorded and transcribed remotely using Microsoft Teams. 42 Field notes were taken by the interviewer to support with prompts and track the discussion. Transcripts were transferred to NVivo 14 software 43 for analysis. Participants provided demographic information and details about their professional role (including role title and the number of years they had worked in NHS TTad services) via form (Supplementary File 1). All data collected were anonymised. Participants were given £15 for their participation.

Data analysis

The six stages of Reflexive Thematic Analysis Reference Braun and Clarke38 were followed: (a) familiarisation with the data, (b) coding of the data, (c) development of meaningful patterns of data or ‘themes’, (d) refinement of themes, (e) definition of themes and (f) writing up. A strength of reflexive analysis is that it requires the researcher to reflect on the data across each stage of analysis and engage critically with them, taking into account one’s own position and biases. A contextualist approach was considered appropriate to address questions about the experiences of NHS TTad treatment from the perspectives of therapists who treat women from minoritised ethnic groups. This approach sits between the essentialist and constructionist approach, allowing for the acknowledgement of the ways in which individuals derive meaning and make sense of their experiences. Reference Braun and Clarke38 Use of this approach was considered appropriate for the current study because it focused on the perspectives of a certain group (therapists) and was conducted alongside another similar piece of qualitative work exploring the perspectives of patients; Reference Arundell, Saunders, Barnett, Leibowitz, Buckman and Pilling37 this allowed for perceptions and cultural, social and personal contexts in the interpretation of findings.

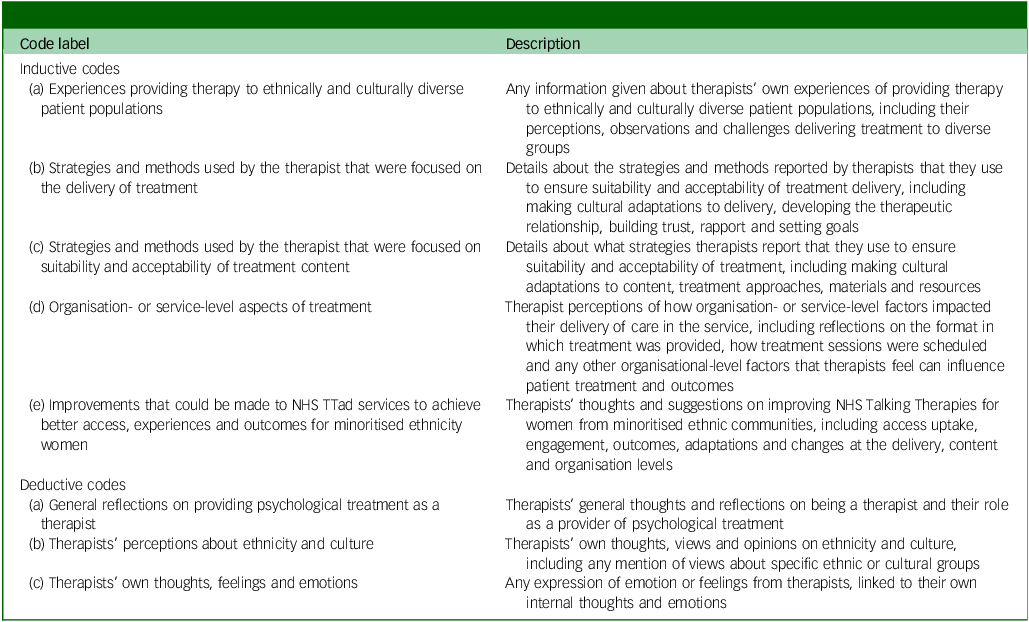

Coding was staged. First, important segments within the text were identified and highlighted during data familiarisation (before interpretation). A codebook Reference Crabtree and Miller44 was then applied to organise the text data for interpretation. The codebook was defined from existing work on cultural adaptations to psychological therapies Reference Arundell, Barnett, Buckman, Saunders and Pilling15 in line with the interview questions. A hybrid approach of both inductive and deductive analysis Reference Fereday and Muir-Cochrane45 was used to embed interpretation of themes into existing knowledge while allowing for the establishment of any new codes in an iterative process, as the data were sifted and understood. The coding structure is presented in Table 1, and a description of the stages of data coding in Supplementary File 1.

Table 1 High-level inductive and deductive codes developed for text analysis of therapist interview data

NHS TTad, NHS Talking Therapies for anxiety and depression.

Themes were discussed between the research team and validated using a portion of the data (two randomly selected interview transcripts). Two participants provided input on the themes and interpretation of results for additional validation. A full description of the stages of data coding performed by researchers is provided in Supplementary File 1.

Results

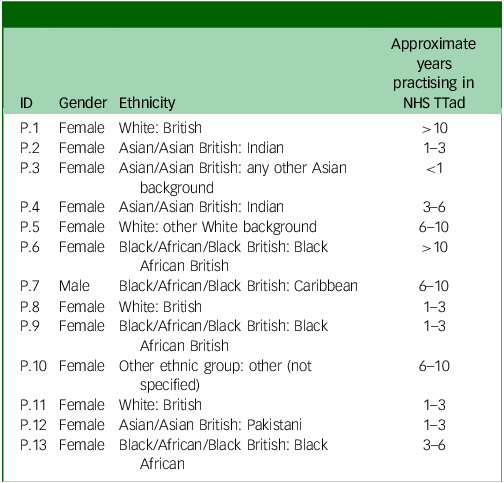

Thirteen therapists took part, 12 of whom identified as female (92%). Five participants reported their age as between 25 and 34 years (38.5%), four as 35–44 years (30.8%) and two as 18–24 years (15.4%). One participant reported their age as between 45 and 54 years (7.7%) and another chose not to disclose this (7.7%). Six participants were HITs and seven were PWPs. Further participant characteristics are given in Table 2.

Table 2 Therapist participant characteristics (N = 13)

NHS TTad, NHS Talking Therapies for anxiety and depression.

Themes

Theme 1: incorporating ethnicity and culture in the delivery of psychological therapies

Figure 1 displays theme 1 and second-order themes (P number in parentheses refers to the therapist involved). Therapists discussed being aware of someone’s ethnicity or culture, and their experiences because of these factors, as being important to consider when identifying the best approach to treatment and whether adaptations are needed:

‘I think the identity factor comes in a lot of ways to the adaptations I make … not just in terms of thinking about anxieties and negative thoughts and recognising, you know, is this related to an identity factor and is it helpful for me to dismiss that? … And I do think one of the things we underestimate is people’s sense of identity and perhaps that can actually be even … a more important factor for individuals who struggle with their sense of identity because of experiences and due to … – racism and discrimination’. (P.11)

Fig. 1 ‘Incorporating ethnicity and culture in the delivery of psychological treatment’ and second-order themes.

Use of culturally congruent terms or reframing talking points in a culturally sensitive manner was discussed:

‘… language is really important. And I know that there’s a lot of different ways of just referring to things and within … different cultures and countries and people coming from a different cultural background will have a preference for the way they refer to even things like their mental health and well-being and the terms they use’. (P.11)

Therapists provided examples of when they had made faith-based adaptations in response to patients’ needs:

‘Incorporating things like reading the Quran, praying, because BA [behavioural activation] is always about activities’. (P.12)

Faith-based adaptations also factored into organisational-level aspects of treatment – for example, when the patient might need to attend their treatment session at an alternative time or day:

‘… making sure that you are flexible around like the holy days or festivals ….’. (P.4)

The ways by which therapists could address the challenges associated with awareness and stigma were discussed:

‘… explaining kind of very thoroughly what the sessions are gonna involve, because I think a lot of people have quite- especially they’ve not accessed therapy before and if they’re from a kind of, minoritised group where mental health is quite stigmatised, then they might have a very stereotyped vision of what therapy involves’. (P.8)

Therapists spoke of demonstrating interest in a person’s ethnicity or culture and their experiences related to that, as part of developing therapeutic rapport:

‘Unfortunately, we know that some … people from minoritised backgrounds do encounter discrimination, racism. “Is this something that is important or has happened?” And then you may wish to … check in with them’. (P.6)

Therapists commonly recognised that patients might feel more comfortable working with a therapist with whom they shared the same or similar identity characteristics, such as ethnicity, culture or gender:

‘… I do think often … especially women from BAME backgrounds … because of the shame, a lot of the times, especially in the Asian community… mental health is still not classified as mental health … there’s this notion that there is no such thing as depression when they see an Asian woman as a practitioner … giving them a space to talk, it definitely does, I think, behave as the facilitator, gives them that confidence to talk …’. (P.12)

Also discussed as essential to the therapeutic relationship and building rapport was the presence of quality interpreters for people for whom English is not their native language:

‘They [interpreter] can be really helpful in that sense. Like there was a couple of questionnaires that hadn’t been translated into Ukrainian. So, I got an interpreter to kind of write down the questions … sometimes they’ll help explain things about the kind of cultural norms and stuff like that’. (P.1)

Therapists gave examples of occasions where they thought supervision had supported their professional growth or development around working with diverse groups:

‘… I had a sort of one-off supervision session with the [position of person in service removed to maintain anonymity]. And she was from a minority ethnic group. And she was sort of really interested in this bit of the critical incident [of the patient] where there’d been some kind of racism. And she was saying, like, “oh, tell me a bit more about, you know, the patient like, has she experienced racism at other times…?”’. (P.1)

Therapists often spoke warmly about their experiences treating people from diverse backgrounds, including that the experiences were enriching and that they had learned from working with people from different cultures:

‘… I enjoy working with multicultural groups of people … it’s enriching … it kind of keeps you on your toes. So yeah … I would describe it as quite an enriching experience … and a learning experience’. (P.9)

While therapists reflected on their own individual responsibilities in the provision of good care for people from minoritised ethnic groups, they also discussed the vital role of the organisation in supporting them to do so. A manageable workload was one factor that was considered essential:

‘I think that’s always hard … because we’re always- always doing back-to-back to back appointments, especially as a PWP, you don’t even have time sometimes in between to think about even [sic] adaptations’. (P.12)

Also considered important was the organisation enabling therapists a degree of flexibility with regard to treatment formats, timing and intervention duration:

‘I have this other Turkish lady starting … she’s got mobility difficulties and the adjustment with her is she wants to have sessions every other week and she – she can’t come in every week because of the mobility difficulties, because she is dependent on others, but also there’s issues with connecting online because she doesn’t have a laptop and a device’. (P.4)

A multi-ethnic, multicultural workforce was seen as a benefit to patients who belong to minoritised ethnic groups:

‘I’m thinking about recruitment and actually having a diverse workforce that is more reflective of the community that we [are] working within’. (P.10)

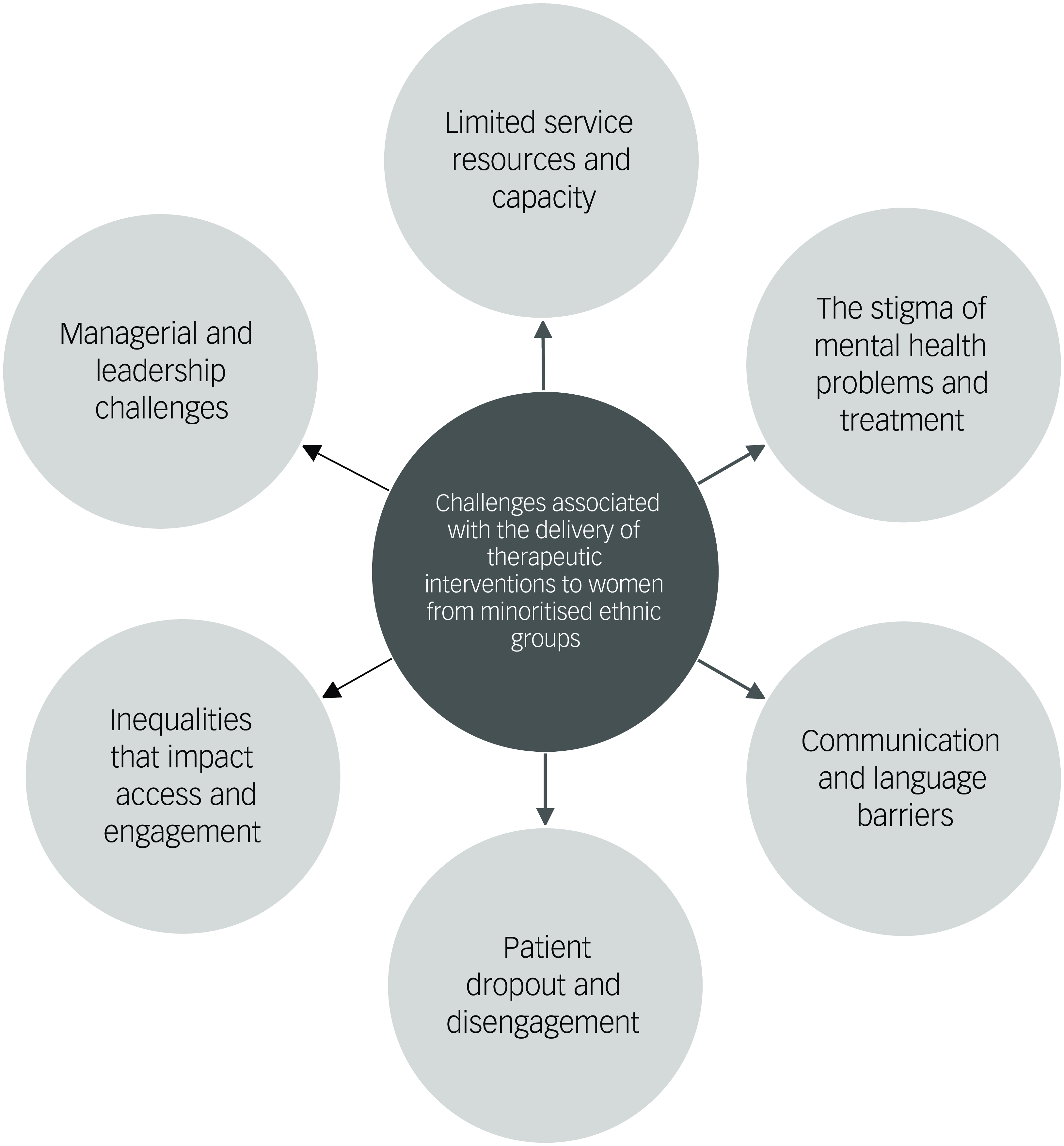

Theme 2: challenges associated with the delivery of therapeutic interventions to women from minoritised ethnic groups

Figure 2 displays theme 2 and second-order themes. Therapists discussed having limited capacity to engage in outreach and engagement work that they considered necessary to improve the uptake of women from minoritised communities:

‘So, I don’t think [name of service] has any presence in those [communities], so we’ve … been trying to kind of set up something with the Somali community, but we don’t have time. That’s the problem. We don’t have time to kind of see it through’. (P.5)

Fig. 2 ‘Challenges associated with the delivery of therapeutic interventions to women from minoritised ethnic groups’ and second-order themes.

Challenges associated with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic were common:

‘That was our work … every day we’d go to different community centres, offering workshops, making those connections … Obviously, this pandemic happened, so a lot of the connections that I had didn’t quite … things didn’t quite work out ….’. (P.13)

Therapists also discussed the challenges of stigma, including some patients’ tendencies to focus on physical rather than mental health needs:

‘I’ve had … a couple of assessments where they’ve sort of been like “I don’t have any mental difficulties, like my difficulty is purely physical” and the GP picks up on perhaps there is a mental health side … Could be there’s a lack of acceptance of the mental health impact maybe?’. (P.3)

Communication challenges and language barriers were common issues. In particular, the use of interpreter services was considered challenging:

‘… there’d be a range of quality in the interpreting, and we’d find a really good interpreter and then try and book them for all of the sessions that I had with the patient because it’s good for continuity … but then there’d be loads of practical issues where the interpreting company we used would send someone different even though we’d requested the same person’. (P.1)

Therapists also spoke of the challenges of exploring personal difficulties with patients when an interpreter was present:

‘There will be the ones that need interpreters, which makes it hard in the sessions to explore their main difficulties … I guess if there’s a translator – … or it’s on the phone … I don’t know how to explain this, but if it’s like an interpreter in the session with the client and it’s a face-to-face session, there’s a lot of facial expressions that would express that you are being empathetic and you’re listening’. (P.4)

There were challenges perceived to be associated with structural and societal inequalities to access:

‘… I don’t think … enough people from ethnic backgrounds are kind of accessing IAPT services for a few different reasons. But I’d say once you get over the more, kind of, “getting them in the door” aspect of things, the barriers there … again kind of speaking anecdotally, I find that there has been kind of some barriers or some issues in terms of getting people actually into treatment’. (P.7)

Therapists made it clear that their ability to provide adequate care to patients from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds was dependent, to some degree, on adequate support from those in positions of leadership:

‘… I think with our management team they won’t – they won’t necessarily generate these things … It does sometimes feel like it’s all on our shoulders in, in terms of their equality and diversity team that I sometimes wonder if I didn’t mention anything, would it ever be talked about’. (P.5)

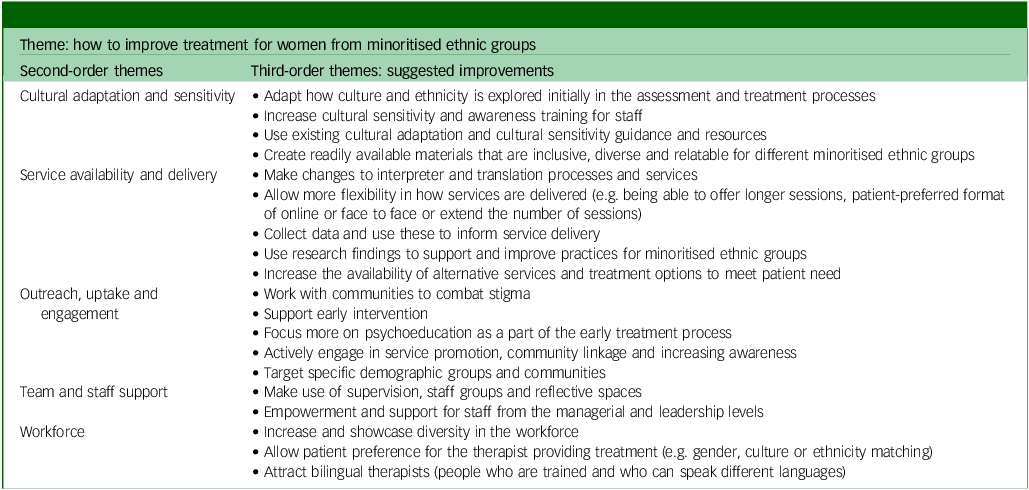

Theme 3: how to improve treatment for women from minoritised ethnic groups

Figure 3 displays theme 3 and second-order themes. This theme was further broken down into third-order themes for deeper exploration, to extract actions that therapists suggested could improve treatment for women from minoritised ethnic groups. Under each second-order theme are third-order themes presented as suggested improvements (Table 3).

Fig. 3 ‘How to improve treatment for women from minoritised ethnic groups’ and second-order themes.

Table 3 How to improve treatment for women from minoritised ethnic groups: second- and third-order themes from therapist participants

Cultural adaptation and cultural sensitivity

Commonly suggested improvements regarding cultural adaptation and cultural sensitivity included how ethnicity and culture are explored early in the assessment and treatment processes:

‘Diversity … should be taken into account when it comes to their mental health and I would always be interested in asking within assessments about how clients feel their diversity characteristics may impact their mental health and their well-being, and whether historically or currently’. (P.11)

Improvements to cultural sensitivity and awareness training for staff and managers were considered necessary:

‘… going back to that idea of education, training for the provider is really important because I think a big thing that contributes to outcomes is feeling that your therapist doesn’t understand you and there’s not that sort of connection for them to appreciate, sort of where you’re coming from with the difficulties you’re having’. (P.11)

Several therapists (n = 5, 38.5%) made explicit reference to the BAME Positive Practice Guide: Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2

‘I know the positive practice guide and I’ve read through that … that’s quite helpful actually to get like generic guidelines on how to adapt the sessions, including the length of the sessions’. (P.4)

Service availability and delivery

Improvements to interpreter processes and services were common suggestions:

‘… maybe a bit more of a policy in terms of how we manage interpreting with different languages … so that we all know, I guess like a structure in a way’. (P.8)

The issue of greater flexibility in how services are delivered to improve patient experience, engagement and potential outcomes comprised several suggestions. These included therapists being able to offer longer sessions depending on need, and this was often related to challenges working with interpreters:

‘… I had to do this one specific assessment using telephone interpreting … in the 50 minutes I wasn’t able to do the questionnaires, which is a requirement … if we could get like maybe 1 and a 1/2 hours instead of 50 minutes for a session with that interpreter, having that flexibility’. (P.4)

Therapists also suggested that flexibility in the number of sessions they provide could be beneficial to some patients:

‘… if it was a standard to … have a bit more … even just having seven to eight sessions … because six sessions is very brief … I’ve seen amazing things it’s done … in terms of helping clients. But I think when you need firstly to kind of socialise the client to CBT’. (P.13)

There were also suggestions made regarding flexibility in the structure of treatment, depending on need:

‘… let’s say we have three to six half an hour sessions but instead of three to six half an hour sessions we might do like [a] fifteen minute session every week? So, it’s not too overwhelming for them’. (P.12)

Therapists felt that the offer of different treatment formats was beneficial and could be more consistent:

‘… we’re having face to face sessions because she said she would prefer that because of the language barrier and she’s fine face to face …’. (P.4)

Some therapists expressed ideas they’d had about providing therapy in group formats for specific communities of women:

‘I think offering groups and for … people from different minoritised groups … especially for women. Yeah, it’s group sessions. It could be based on ethnic background and more specific problems for women from particular backgrounds … they can be incredibly healing …’. (P.10)

There were suggestions about alternative routes or pathways to care for underserved women:

‘… it’s very related to access … I mean, aside from the general routes of GP, self-referral … there aren’t really any routes that I’m aware of … specifically helping my minoritised … women access our service … it would be good to see maybe specific pathways that … inform minoritised women about our services … more of a pathway to be set up at service level in terms of that’. (P.8)

Outreach, uptake and engagement

Therapists suggested how services could better target specific communities of women at risk of being underserved by mental health services:

‘… you know when you’re doing your advertising and stuff like … is a Black person, particularly a Black woman, maybe a Black woman of a particular age … are they kind of represented? Are you kind of, in the community spaces? … Maybe like … if you can do projects in Black Barber shops, can you also do them in like Black salons?’. (P.7)

Therapists recognised that combating stigma was essential to increasing uptake and engagement with mental health services, and suggested that this could also be tackled with outreach into communities:

‘… workshops and stuff in the community to kind of reduce some of that kind of fear of having to kind of access a service’. (P.2)

Therapists also discussed the need for improved psychoeducation as part of the early treatment process to tackle stigma, and emphasised that educating communities on mental health and normalising help-seeking were essential parts of the process to improve engagement:

‘… start the intervention by doing some psychoeducation and then we move on to – and what the intervention actually is, and I think we almost need to stay in that kind of psychoeducation phase for a little bit more just to kind of understand, reduce the stigma’. (P.3)

Workforce

It was a belief commonly held that demonstrating and showcasing diversity in the workforce would facilitate uptake and engagement for minoritised ethnic women:

‘… although I say yes, we’ve got … colleagues and practitioners you know that that are from BAME background but … there isn’t enough still … I think it’s been increasing over the past few years … there’s been more recruitment into trying to make sure … that we have a diverse workplace … But it’s harder sometimes in some services there might not be a lot of people from BAME backgrounds’. (P.12)

Patient preference to be seen by a therapist with certain characteristics was discussed:

‘… do they need a different therapist? Do they want to have a therapist that relates more to –? That question is never asked. So that question is actually not asked during, you know, a lot of assessment templates, like would you prefer to have a therapist from a similar cultural background to you?’. (P.12)

Despite some varying opinions on ethnic, culture or gender matching, there was a general consensus among therapists that there might be some benefit to asking patients about whom they may prefer to work with:

‘Sometimes it’s more about who they might not want to work with, and I guess I tried to make it feel as safe as possible … “What would help you feel safe?”’. (P.10)

However, it was acknowledged that some patients might prefer not to be seen by a therapist with whom they share a cultural or ethnic background:

‘… I think there’s an assumption that somebody will benefit from having somebody who is linked with their ethnic background and provide the support they’re looking for. But actually, it can certainly – and I’ve seen it go the other way where actually, like, [it] can make people more uncomfortable if mental health is viewed in a specific way’. (P.11)

A particularly common workforce improvement centred around efforts to recruit bilingual therapists to the service:

‘… I think it would be good if we could maybe encourage like people who speak different languages to offer services in their native language if they were to feel comfortable doing so, because I think as well as one thing going for therapy … I think that would be good to kind of encourage or maybe provide more support for staff to offer those kinds of things’. (P.8)

Team and staff support

Improvements regarding team and staff support included opportunities for closer working with colleagues to share resources, experiences and learning:

‘… even like speaking to colleagues … – and share resources with them like … what would you recommend for this particular client …? And … share resources amongst us as well would be quite helpful … have like shared BAME resources’. (P.13)

Finally, therapists also made suggestions about how they felt they could be better supported and empowered by those in managerial and leadership positions:

‘I think there needs to be more training on how managers can be more culturally competent as managers … I do think these things trickle down to the care that we provide’. (P.10)

Further detail on themes, subthemes and supporting quotes is presented in Supplementary File 1.

Discussion

This study presents a qualitative exploration of experiences of therapists providing psychological treatment, with a focus on their experiences treating women from minoritised ethnic communities. Although this study was conducted with just two services, the findings resonate with existing cultural adaptations and mental health service improvement literature, and highlight actions that therapists themselves, as well as those in leadership and decision-making positions, could take to improve care for underserved groups of women.

Therapists recognised the well-evidenced value of incorporating ethnicity and culture into psychological treatment, especially when working with people from diverse cultural backgrounds. Reference Arundell, Barnett, Buckman, Saunders and Pilling15,Reference Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey and Domenech Rodríguez46 Cultural competence and the ability to display cultural sensitivity were considered particularly vital skills, corroborating previous research. Reference Kirmayer18,Reference Kirmayer and Jarvis19,Reference Faheem35 Similar research that included a qualitative exploration of therapists’ perspectives on ethnic inequalities in NHS TTad services was conducted with a broader sample of participants from regions across England. 47 Findings from this research align with the current study in highlighting the importance of cultural sensitivity, proactively discussing cultural issues both with patients and in practitioner supervision and integrating culture into the therapeutic process. Although therapists spoke often about cultural sensitivity and having awareness of how a person’s ethnicity might influence their experiences, identity and therapeutic rapport, issues regarding racism and discrimination were only minimally discussed. Even where structural and organisational barriers perpetuating inequalities were raised by participants, racist and discriminatory practice was not a key theme in this study. This contrasts with other research exploring ethnic differences in mental healthcare where systemic and structural racism were found to be key factors in service failures for people from minoritised ethnic communities. Reference Bansal, Karlsen, Sashidharan, Cohen, Chew-Graham and Malpass48

Many of the suggested improvements focused on the actions therapists themselves could take to improve treatment delivery, such as making efforts to utilise existing cultural adaptations resources and actively displaying cultural sensitivity in early interactions. In addition, several improvement suggestions were aimed at the services or wider organisation (the NHS Trust) and their responsibility to provide the training, support, infrastructure and processes needed for therapists to deliver culturally sensitive care. Reference Faheem35 Organisational-level adaptations are shown to have a beneficial influence on outcomes for minoritised ethnic communities Reference Arundell, Barnett, Buckman, Saunders and Pilling15 and therapists picked up on this notion, raising improvement suggestions such as enabling more flexibility in treatment format (i.e. remote, via telephone- or internet-enabled technologies and in-person treatment options), session timing and intervention duration. Providing treatment in a variety of formats is recommended in treatment guidance, 3 and research has shown that clinicians appreciate the value of remote treatment. Reference Buckman, Saunders, Leibowitz and Minton49 However, therapists in the current study were cognisant of the limitations of remote treatment Reference Johnson, Dalton-Locke, Vera San Juan, Foye, Oram and Papamichail50 and recognised differences in its suitability for different people depending on their individual needs and resources. Reference Liberati, Richards, Parker, Willars, Scott and Boydell51

Therapists considered improved psychoeducation, which is a vital component of many forms of psychological therapy, Reference Khoury and Ammar52,Reference Roth and Pilling53 as particularly important for women who are not familiar with mental health treatment or who may be concerned about stigma. While psychoeducation and familiarisation fall within a therapist’s set of responsibilities, therapists recognised that this could not be achieved in the absence of support from the service to allow for longer treatment sessions or an extended period of treatment where needed.

All therapists referenced improving outreach or increasing awareness. The value of outreach to underserved communities is reported extensively in the mental health literature. Reference Castillo, Ijadi-Maghsoodi, Shadravan, Moore, Mensah and Docherty54,Reference Wright, Callaghan and Bartlett55 Engagement and uptake are also linked to addressing stigma, Reference Corrigan, Druss and Perlick30 which was another challenge raised by therapists in this study. Again, the requirement for the organisation to provide the infrastructure to ensure that therapists have the time and resources to engage in outreach work, either by ensuring a sufficiently large workforce or developing specific roles responsible for community linkage, is emphasised by the findings of this study. One significant workforce-related improvement focused on the attraction and recruitment of culturally and ethnically diverse therapists and those who could provide psychological treatment in languages other than English.

Many of the findings from this study of therapists are corroborated by a qualitative study with female patients from minoritised ethnic communities, which explored their perspectives on how to improve psychological treatment within NHS TTad services. Reference Arundell, Saunders, Barnett, Leibowitz, Buckman and Pilling37 Across both qualitative studies, suggestions arose about allowing for patient preferences for the therapist providing their treatment. While ethnic and culture matching were discussed in both, views as to whether this would serve as a facilitator or a hindrance to improved care were varied. This is in line with existing research that has shown ethnic matching to be highly variable. Reference Cabral and Smith56 While ethnic matching views were varied, there is general consensus across both studies around gender matching and giving patients a choice about the gender of the therapist they are going to see. For female patient participants, relatability of the therapist was raised as an important factor and tended to be based on perceptions of the therapist’s identity characteristics (such as age and gender). Reference Arundell, Saunders, Barnett, Leibowitz, Buckman and Pilling37 As with ethnic matching, the research on the benefits of gender matching in psychotherapy is inconclusive, Reference Bhati57,Reference Schmalbach, Albani, Petrowski and Brähler58 yet offering this to patients was seen as a vital improvement that services could make to improve care for minoritised ethnic women. Reference Arundell, Saunders, Barnett, Leibowitz, Buckman and Pilling37 Several patients reported that they considered having a female therapist as essential to their treatment, especially in cases where they had experienced previous traumatic experiences with men. Reference Arundell, Saunders, Barnett, Leibowitz, Buckman and Pilling37

This study contributes to the existing evidence on the need for improvements to psychological therapy services to optimise treatment for women from minoritised ethnic communities. The study provides evidence of the importance of incorporating culture and ethnicity in treatment, the challenges associated with delivery of treatment to minoritised communities and suggested improvements. The findings suggest that therapists are aware of many of the issues that commonly impact access, engagement and outcomes for minoritised ethnic women, but that they also recognise the solutions that could contribute to positive changes. Improvements to mental health services rely upon therapists’ competences and abilities, as well as support from those in leadership and decision-making positions to implement changes and adaptations. Important factors include ensuring that there is flexibility in how services are accessed and delivered, a stronger focus on outreach and increasing awareness, provision of strategies to remove language and communication barriers and increasing workforce diversity and representation. Although the study was focused on minoritised ethnic women using NHS TTad services, many of the suggestions are generalisable across genders and treatment settings. As such, the findings have the potential for wider clinical application and utility.

Limitations

The sample was limited to 13 participants, of whom 12 (92%) identified as female. While the vast majority of therapists in NHS TTad services are female (80%), 59 the paucity of male participants means that the study was not able to hear the voices of an important group of therapists. Similarly, there was little representation of older working-age therapists. The recurrent emergence of themes suggested that data saturation was reached, although it is possible that higher numbers of male and older participants may have presented additional views.

The sample was taken from two NHS TTad services covering Camden and Islington, both of which are ethnically and culturally diverse areas, housing large populations of international students, recent immigrants and refugees. The limitations of the generalisability of findings to services operating in regions with starkly different population demographics should be noted. The generally positive perceptions and experiences of NHS TTad expressed by therapists in this study could be a reflection of service provision in these London boroughs specifically, where the services may be particularly well delivered and well received compared with NHS TTad services in other regions. The study recruited an ethnically diverse sample of participants, and the majority of therapists (77%) reported belonging to a minoritised ethnic group themselves; nationally, the NHS TTad workforce is predominantly comprised of White or White British individuals. 59 While it was not possible to obtain an accurate breakdown of workforce ethnicity by service, Trust-level data from the NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard show that London has the highest percentage of Black, Asian and minoritised ethnic (BME) staff compared with other regions of the country. 60 The ethnic diversity of the practitioners sampled is likely to have influenced their perspectives on culturally appropriate treatment, their views about service delivery for minoritised ethnic communities and, as such, the inferences drawn.

Transcripts were not double-coded, although the codebook was developed based on existing research and was independently applied to a sample of randomly selected transcripts by two researchers.

Interviews were conducted remotely using Microsoft Teams, a method chosen due to COVID-19 restrictions when the study was designed. While remote interviews provide benefits such as accessibility and efficiency, interviews conducted remotely may yield different findings than face-to-face interviews. Reference Lobe, Morgan and Hoffman61

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.36

Data availability

The appendices provided in Supplementary File 2 contain a more detailed description of results, together with further quotes supporting identified themes. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (L.-L.A.) upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

L.-L.A. was responsible for conceptualisation, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, resources, writing of the original draft, visualisation and project administration. R.S. undertook conceptualisation, methodology, writing review and editing and supervision. P.B. carried out validation, formal analysis, writing review and editing. J.L. performed conceptualisation, methodology, resources and writing review and editing. J.E.J.B. was responsible for conceptualisation, methodology and writing review and editing. F.W. undertook formal analysis, interpretation and writing review and editing. S.P. carried out conceptualisation, methodology, validation, resources, writing review and editing and supervision.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2013. Procedures were approved by the UK Health Research Authority: project nos EDGE ID: 138495XX and IRAS ID: 288406; and Research Ethics Committee: reference no. 21/SW/0094.

Consent statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.