Introduction

In the summer of 2015, during which approximately 1 million people arrived in European territories from Turkey and an estimated number of 799 migrants died,Footnote 1 an immediate response was formulated under the 2016 EU–Turkey Statement (the so-called Refugee Deal),Footnote 2 with the intention to construct and intensify the transnational infrastructure of externalized border governance not only across the Aegean Sea and within Turkey, but also in the countries of origin.Footnote 3 With the Statement, the EU has presumed Turkey to be a “safe third country” despite the fact that it does not provide refugee status to people coming from a non-European country owing to the principle of geographical limitation in the 1951 Convention.Footnote 4 Since then, Turkey has been hosting the largest displaced population in the world. What was initially framed as the return of those who “irregularly” crossed from Turkey to the Greek islands in 2016 has culminated in the return of Syrians from Turkey being at the center of political debates, with society on the brink of social turmoil and escalating antirefugee discourse and hyperimpoverishment in recent years.

In 2021, a newly established far-right party whose main platform is strident antirefugee rhetoric came to prominence. Under its sponsorship, a nine-minute video, entitled “The Silent Occupation,” was posted on YouTube and widely circulated on social media. Portraying a dystopian future in which the Turkish republic had collapsed, the video shows Turks as second-class citizens who are being discriminated against and oppressed by Arab migrants. Following a social media campaign dubbed “send Syrians home” and the general discourse of the main opposition, the issue of migration became one of the most significant aspects of the national election process, and on May 4, 2022 the Turkish president announced the commencement of a return plan for 1 million Syrians to prefabricated houses, schools, and hospitals being constructed in northern Syria under the control of the Turkish army.Footnote 5 Reconnect, a project for training Turkey’s first national voluntary return counsellors, was launched in October 2022, co-implemented by the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) and the Presidency of Migration Management of Turkey (PMM).Footnote 6

This chapter turns the spotlight onto Turkey, a country at the EU’s frontier and a candidate country that has a frozen accession history and is currently hosting the world’s largest displaced population (around 4 million as of spring 2024, including registered Syrians and non-Syrians),Footnote 7 Turkey itself is witnessing economic downturn, hyperinflation, extreme impoverishment coupled with authoritarian rule, and deterioration of the rule of law. The EU’s decades-long border policies, producing new spaces of intervention exercised with its neighbors and along migratory routes, have sparked considerable scholarly interest and criticism. This has led to an examination of the reconfiguration of border mechanisms as outsourced, offshored, shifting, mobile, itinerant, and dispersed, operating within and beyond the territorial limits of sovereign states (Balibar, Reference Balibar2004; Bialasiewicz, Reference Bialasiewicz2008, 2012; Casas, Cobarrubias, & Pickles, Reference Casas-Cortes, Cobarrubias and Pickles2011; Casas-Cortes, Cobarrubias, & Pickles, Reference Casas-Cortes, Cobarrubias and Pickles2013, Reference Casas-Cortes, Cobarrubias and Pickles2016; Coleman, Reference Coleman2007; Newman, Reference Newman2006; Rumford, Reference Rumford2006, Reference Rumford2008; Shachar, Reference Shachar2020b; Walters, Reference Walters2004, Reference Walters2006; Weizman, Reference Weizman2007). These processes have not only turning the Mediterranean Sea into a “death world” (Mbembe, Reference Mbembe2003), but have also created various forms of “deterritorialized zones of lawlessness” (Benhabib, Reference Benhabib2020: 96).

For historians, the assumption that the regulation of movement is a constitutive aspect of any political order is nothing new. Throughout history, apparatuses of enclosure, forced displacement, and free circulation of movement have been exercised in various formulations and allocations (Kotef, Reference Kotef2015; Nail, Reference Nail2016). In today’s world, we witness borders and legal barriers to be increasingly in flux; as Ayelet Shachar nicely puts it, operating “in a quantum-like fashion, simultaneously fixed and fluid, stationary and portable, exerting influence over those coming under its kaleidoscopic dominion” (Shachar, Reference Shachar2020b: 9). Besides the spatial mobility of today’s borders, Elizabeth F. Cohen (Reference Cohen2018) reminds us how time as well is assigned as a form of political value and is frequently inserted into political procedures for conferring and denying citizenship rights. Many others are analyzing the complex temporalities at stake in contemporary modes of governing migration (Jacobsen et al. Reference Jacobsen, Karlsen and Khosravi2021). Yet concerning the overlapping of time–space coordinates at borders, the Western gaze has to be transcended in order to go beyond current concepts and to grasp the level of “liquidity” in the Global South as opposed to that in the Global North (see Bauman, Reference Bauman2000).

As the largest refugee host country in the world, Turkey, I argue, manifests a varied set of legal and governing techniques that are designed to monitor millions of displaced people within a broad design of temporality and spatiality. When the country’s contested gatekeeping function for Europe coincides with a shrinking economy, an authoritarian rule seeking to hold on to its political power, and the decades-long ideological aspiration to be a regional actor in the Middle East, millions of displaced bodies are turned into an instrument of demographic engineering, at a time when this is strikingly in flux (İşleyen & Karadağ, Reference İşleyen and Karadağ2023).

In the chapter, I first focus on the legal and spatial/temporal architecture of Turkey’s migration regime, one that produces layered levels of legal precarity and temporal gaps that are intertwined with demarcated spatial boundaries. Second, I explore how this legal and spatial/temporal architecture is daily violated and self-sabotaging in line with the needs of the informal labor market, thus continuously generating irregularity and arbitrariness. Finally, by examining events, I explain a set of governing technologies, at times paradoxical, that transform these irregularized bodies into floating populations engaged in cycles of (forced) movement. The study not only examines the role of legal design in the country, but also analyzes the daily implementation of legal texts, aiming to capture the level of arbitrariness that is present. To that end, I conducted interviews with five lawyers who specialize in Turkish refugee law.

1 Legal Architecture of Protection: Degrees of Temporality and Spatial Organization of Movement

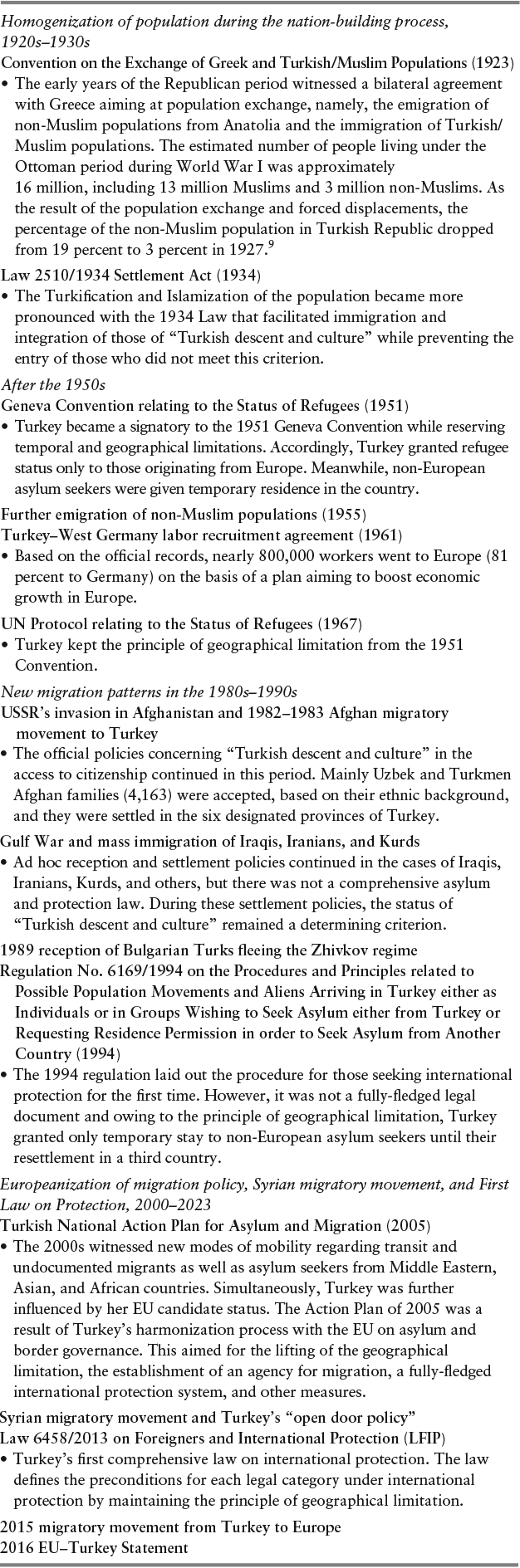

The basis of Turkey’s international protection regime dates to the 1951 Geneva Convention and thereafter the 1967 Protocol, with Turkey still holding to the principle of geographical limitation in its implementation. What this entails is that refugee status is granted only to persons originating from European countries, while non-European asylum seekers have to make an individual asylum application and undergo “refugee status determination” procedures before being resettled in a third country. That is to say, non-European asylum seekers can only stay in Turkey temporarily until they are resettled in a third country. Despite receiving global migration flows over the last few decades, Turkey lacked a fully-fledged legal architecture of international protection until 2013, instead pursuing ad hoc reception and settlement policies that could be linked to her nation-building process (Table 12.1). Accordingly, the arrival of Turkic and Muslim populations was chiefly encouraged in cases of mass displacements,Footnote 8 based on the status of “Turkish descent and culture,” while the emphasis on Turkish ethnicity has continued to be a significant factor (Karadağ, Reference Karadağ2021; Karadağ & Sert, 2023; Kasli & Parla, Reference Kasli and Parla2009; Parla, Reference Parla2011).

Table 12.1 Critical junctures in Turkish migration policy since the early twentieth century

| Homogenization of population during the nation-building process, 1920s–1930s Convention on the Exchange of Greek and Turkish/Muslim Populations (1923)

Law 2510/1934 Settlement Act (1934)

After the 1950s Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951)

Further emigration of non-Muslim populations (1955) Turkey–West Germany labor recruitment agreement (1961)

UN Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees (1967)

New migration patterns in the 1980s–1990s USSR’s invasion in Afghanistan and 1982–1983 Afghan migratory movement to Turkey

Gulf War and mass immigration of Iraqis, Iranians, and Kurds

1989 reception of Bulgarian Turks fleeing the Zhivkov regime Regulation No. 6169/1994 on the Procedures and Principles related to Possible Population Movements and Aliens Arriving in Turkey either as Individuals or in Groups Wishing to Seek Asylum either from Turkey or Requesting Residence Permission in order to Seek Asylum from Another Country (1994)

Europeanization of migration policy, Syrian migratory movement, and First Law on Protection, 2000–2023 Turkish National Action Plan for Asylum and Migration (2005)

Syrian migratory movement and Turkey’s “open door policy” Law 6458/2013 on Foreigners and International Protection (LFIP)

2015 migratory movement from Turkey to Europe 2016 EU–Turkey Statement |

In 2013, the legal construct of migration regulation finally came into force, with the adoption of the Law on Foreigners and International Protection (LFIP), a long-awaited product of the harmonization process with the EU border regime that had developed in tandem with EU membership negotiations since the 2000s. The LFIP contains its own peculiar technologies of governance which render it a sui-generis case of temporal and spatial architecture. First, it still applies geographical limitation and thereby provides refugee status only to those from European countries. Considering that European applicants are nonexistent in practice,Footnote 10 the law mainly lays out the temporal hierarchies according to specific legal categorizations for millions of displaced populations from non-European geographies, in a way echoing what Tize (Reference Tize2020) calls “permanent temporariness” to varying degrees. It also delivers legal spatiality as a settlement policy in which legal access and accordingly entitlements are available for those who reside in their provinces of registration.

The law rests on two main legal pillars: temporary protection status (TPS) for Syrians (3,763,565 persons as of March 2022) and international protection status (IPS) for non-Syrians (330,000 persons as of December 2021).Footnote 11 The latter category involves displaced persons predominantly from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Iran among others, seeking third-country resettlement. A third category, much broader and more contentious than the other two, includes a large spectrum of irregularized migrants, such as apprehended migrants, those kept in removal centers, rejected IPS applicants, those pushed back by the Greek authorities, transit migrants, and those who have never registered. The scope of the third category, which concerns those without a legal status, is totally unknown and still expanding given the cracks in the registration system; this is explored further in Section 2. To illustrate the magnitude of this, the Migration Board Meeting of the Ministry of the Interior announced on September 15, 2021 that 1,293,662 irregular migrants had been “apprehended” in Turkey between 2016 and September 2021.Footnote 12 According to the same statement, Turkey deported a total of 283,790 of these “apprehended” migrants back to their countries of origin during the same period. The number of people deported in the first eleven months of 2022 was 101,574, according to official figures.Footnote 13

According to this condition of layered legal precarity that regulates millions of displaced persons, there is no right of permanent stay but only temporally and spatially restricted movement. Syrians under TPS constitute the relatively privileged group within this period of prolonged uncertainty. Temporary protection policies are not new in refugee law, especially when a large number of people are fleeing an armed conflict or a disaster – given the limited scope of the 1951 Refugee Convention.Footnote 14 In such cases, temporary protection policies designate complementary or exceptional forms of protection so that states are able to provide an immediate response to a humanitarian crisis. Yet in the Turkish case, almost a decade after its initial implementation, TPS is still used as a legal status that designates up to 3.2 million Syrians (as of March 2024) but does not provide any specified time frame. A person from Syria is required to approach the provincial directorates of the PMM, in a province of her own choice, to receive a temporary protection identity card. Once provided with an ID, she can benefit from the right to access to healthcare and education, but does not yet receive a work permit. The 2016 “Regulation on Work Permits of Foreigners Under Temporary Protection” gives Syrians access to work permits under TPS, while the regulation only allows employers to initiate the procedure, thus leading to the minimal numbers (63,789 by 2019) of Syrians who have obtained a work permit.Footnote 15 As a result, the fate of the vast majority is in the cruel hands of the informal labor market.

Syrians under TPS can choose their province of registration provided that it is open to new registrants. However, once they are registered, they are bound to that province and require official permission from provincial authorities to be able to move between cities. Concurrently, their access to healthcare, education, and any other public services is restricted to their province of registration. This regulation vividly illustrates how the spatial configuration of movement defines the core of migration governance, in tandem with the legal production of temporality. In her influential book, Hagar Kotef (Reference Kotef2015: 5) notes that neither subject positions nor political orders can be divorced from movement regimes, which have been differently configured and materialized within sets of “material, racial, geographic and gendered conditions” of those subjects. Consequently, regimes of movement are never simply a form of controlling or regulating mobility, but rather produce different categories of subjectivity, that is, ways of being, defining the contours and limits of subjects. The mobility gap between citizens and displaced persons, marked by the city-based registration system, demarcates the spatial boundaries of legality as well as the spaces in which they move (Shamir, Reference Shamir2005). Therefore, city-based registration corresponds to, in Torpey’s words (Torpey, Reference Torpey2018), the “legitimate means of movement” in the Turkish legal architecture.

A similar apparatus of closure or inward borders applies to non-Syrians under IPS, though in a stricter and more precarious manner. As defined in the LFIP, the PMM assigns those seeking international protection from non-European geographies to satellite cities – from which large metropolises and provinces located on the European borders are omitted.Footnote 16 As long as they reside in their assigned cities, they can access public services and healthcare, but this is limited to one year following their registration. Again unlike Syrians under TPS, they have to register and reside in those designated satellite cities without having any prior knowledge of them or of relatives there. It should be noted that these satellite cities are not camp-like spaces, but rather small open cities that accept applications for international protection. Applicants have to stand on their own feet, by seeking a job in the informal sector. If an application is considered positively, the applicant is granted “conditional refugee status” (eligible for third country resettlement) or “subsidiary refugee status” (not eligible for resettlement but with notable risks of persecution in case of return). Another prominent discrepancy between Syrians under TPS and non-Syrians under IPS is that the latter have to provide proof of their presence to the provincial authorities on a weekly basis while the former do not.

Following this illustration of the spatial organization of the migration and border regime in Turkey, with its legal basis embedded in a temporal architecture, Section 2 discusses the ways in which this legal infrastructure becomes a self-undoing mechanism.

2 Demarcations Overstepped: Productions of Irregularities

“What we are facing is not only irregularity of thousands of displaced persons, but also irregularity of regulars,”Footnote 17 said one of my interviewees, a lawyer, who pointed out the striking discrepancy between the legal architecture and daily transgressions. Despite the legal design that is aimed to limit both Syrians under TPS and non-Syrians under IPS to their provinces of registration, they tend to move to other cities, without travel permits, in order to find jobs in the informal sector. Because their legal statuses do not grant work permits, migrants face two options: either a life with legal status or a job.

The lawyers I interviewed frequently drew attention to the institutional changes that occurred in the aftermath of 2018. As of September 2018, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) terminated its operations, and subsequently, the processes of first registration, refugee status determination, and resettlement have been entirely under the mandate of the PMM. Following this institutional shift, new registrations were halted in metropolitan cities owing to the overwhelming burden of internal mobility (European Council on Refugees and Exiles [ECRE], 2020). As a result, Syrians under TPS were deprived of the opportunity to transfer their registration to the larger cities where they informally reside and are employed. For non-Syrians under IPS, larger cities have never been considered to be satellite cities, so all applicants have been guided to the assigned small cities. A similar scenario is valid for them. Moving to bigger cities, even though it is prohibited, has become the only way in which many can survive, given the one-year limit on health services and the shortage of jobs.

The lawyers I interviewed underlined the devastating implications of closed registrations in large cities for Syrians, which had been previously tolerated to a large extent. As noted, until 2018, Syrians under TPS easily accessed healthcare and education in Istanbul even if their province of registration was different. With the hardening of migration policies in the metropolitan areas, “a great crisis has appeared at the door,” as an interviewee noted:

There has been a huge problem regarding the joint children of the spouses in different provinces. Marriage and family reunification is close to impossible in Istanbul […] The parents are registered in Istanbul, there is a minor mistake of a letter in the identity information, then the registration process is reset […] There are also problems with child registration. If one of the parents is registered outside of Istanbul, the approach of the PMM is to refer them outside of Istanbul, that is, to make the family reunification in another province. In the cases of severe illness requiring treatment in a university hospital, again other provinces are prioritized. Since about 2018, Istanbul has been following a very strict registration policy.Footnote 18

Strict registration policies in metropolitan cities result in Syrians under TPS falling into de facto irregularity owing to their inability to change their city of registration. Though the exact number is not clear, a recent field study conducted by the PMM and IOM in 2018–2019 estimated that approximately 1 million Syrians were residing in Istanbul with only 496,000 of them registered in the city.Footnote 19 Hence, nearly half a million Syrians under TPS became irregularized in 2019.

The satellite city system for non-Syrian IPS applicants gives us an even more precarious picture. Testimonies of lawyers demonstrate that the vast majority of cities have been closed to registration; applicants have to go continuously from one city to another to access registration. It is officially uncertain which satellite cities are available for new registrations because of the lack of coordination between provincial authorities. “We, as lawyers, put an Excel tab on the Google Drive, and change the color of provinces as yellow or green to mark whether they are open or not. This can change overnight,” noted my interlocuter.Footnote 20

The obstacles are far from over when registration finally takes place. The applicant finds herself in a small city to which she has been assigned without any guidance regarding accommodation, job, or aid. Hence, she becomes trapped in “chronic waiting,” as Khosravi (Reference Khosravi, Anderson and Keith2014) puts it, for resettlement. This is often a remote possibility in the distant future owing to the astonishingly small quotas for the countries in the Global North:

When the UNHCR suspended all operations, the fate of IPS was plunged into complete uncertainty. Some cities are closed, some receive, and others do not, it is totally unclear. Third country resettlement, despite obstacles, was at least pursued under the UNHCR until 2018, but when the mandate changed, it was completely turned into a lottery; who gets the resettlement message no one knows […] I applied for IPS last year in the city of Uşak, for my LGBTIQ+ Iranian client. It was said that they would call for an interview in two weeks [refugee determination status interview]. No call. We approached again after two months. We trusted them that they would call at some point. It has been two years now.Footnote 21

Another lawyer points to the blindness of the international community and the UNHCR who have entirely abandoned the persons seeking IPS:

The purpose of the satellite city was related to conditional refugee status and resettlement in a third country. People were kept under control with the aim that this would increase their chances of being resettled. However, as the numbers increased, the resettlement decreased, and now it no longer works. It is almost nonexistent. The UNHCR proudly announced that it had resettled 5,000 families in 2021. Really? Five thousand among hundreds of thousands of persons? After seeing the news, I was deeply embarrassed on behalf of them […] There is no international protection in operation here […] As a lawyer, I just laugh at the social integration projects which were pursued for ten years. If there is no registration, then you cannot talk about integration. This is not an issue of humanitarian or education aid; they [the UNHCR] see it is not working. Maybe they saw that it would not work, and they terminated their operations.Footnote 22

Closed registrations in satellite cities constantly produce irregularity: Job shortages, lack of access to healthcare (limited to one year), and protracted waiting push registered asylum seekers, who are required to sign in every week, to move to metropolises at the expense of their temporary legality.

Consequently, both for Syrians by the million under TPS and non-Syrians by the thousand under IPS, the city-based legal system has become a self-sabotaging mechanism, that gives rise to the arbitrary exercise of power and triggers considerable internal movement. My interviewees pointed out that the PMM, as the sole authority in migration governance since 2018, has rationalized that irregularity and arbitrariness are the new rules, both in the sense of legal protection and the mode of governance. One lawyer referred to Franz Kafka’s novel The Castle when he illustrated the modus operandi, a view shared by my other interviewees:

PMM is not a state institution that is legally ascribed, impersonal, has a corporate culture, does not hinge on personal decisions, and is bound by the legislation. There is no corporate precedent. It is completely personal and arbitrary, whose procedures and decisions change from day to night. It is a group of people that we, as lawyers, cannot deal with. We cannot even make them implement court decisions.Footnote 23

3 Cycles of (Im)mobility: Floating Populations

In explaining the conditions of deportees in France, whose lives are reduced to a forced circular mobility through prisons, detention centers, and public space, Carolina Sanchez Boe (2017) uses the term of floating populations. Nicholas De Genova (Reference Genova, Jacobsen, Karlsen and Khosravi2021) furthers this discussion by referring to “the carceral circle,” alluding to Foucault (Reference Foucault1995), and delves into how rejected asylum seekers or illegalized migrants become susceptible to “a repetitive cycle of rejection and detention, expulsion and capture” (Genova, Reference Genova, Jacobsen, Karlsen and Khosravi2021: 192). While these theoretical attempts aptly characterize the disposability of migrants’ lives, they all focus on countries on the Global North, in which the number of cases stands dwarfed in the face of the millions of displaced persons under the temporal lacuna in the Global South, particularly in Turkey.

Here, I seek to extend the scope of the term “floating populations,” by drawing on Turkey. I argue that this showcases a stretching of the term in terms of speed and magnitude by means of numerous modes of governance that at times seem paradoxical. The turning points to be explored in this section, though taking place within a very short period since the 2016 EU–Turkey Deal, correspond to episodes of tightening and loosening of borders in line with the changing political conjunctures and priorities of labor markets.

Following the closure of new registrations in metropolitan cities in 2018, the provincial governorate of Istanbul announced another major policy turn in July 2019. This corresponded to the defeat of the AKP government in the municipal election in Istanbul for the first time since 1994, one of the principal reasons being growing public uneasiness about the overwhelming mobility of Syrians and non-Syrians toward the city. The previous de facto policies of toleration were terminated overnight and the number of police checkpoints dramatically increased across the city. Reports indicate that even though the law (LFIP) does not mandate it, Syrians under TPS and non-Syrians under IPS were detained in large numbers because of their violation of residence restrictions; they were registered in other cities (ECRE, 2020). Official announcements indicated that some were sent back to their provinces of registration and 315,000 Syrians “voluntarily” returned to their country.Footnote 24 Published reports question the element of voluntariness in these return procedures (Amnesty International, 2020).

According to one of my interviewees, “that was the period when the policy of dilution and sweeping, as they call it, came into force.” My lawyer respondent continued:

Persons were intercepted from various parts of Istanbul; targets were given to the police such as “you will reach thirty to forty persons a day or a target figure per week.” There is long list of those apprehended: those who were not registered in Istanbul but in a different province, those who were totally unregistered or undocumented; those who were involved in a crime, those who had problems with their identity documents, and those who had been found to have false statements on their IDs. This is done by internal circulars mostly, and we do not even see some of these circulars.Footnote 25

The process lost momentum over six months and restrictive policies were slightly weakened, as lawyers testify. People who were sent back to their provinces of registration or even to Syria often sought to find ways to return. Resonating with how Franz Fanon (Reference Fanon2004) describes the rationalities of power exercised upon colonized subjects, in which “confused by the myriad signs of the colonial world, he never knows whether he is out of line,” lines are constantly shifting in the Turkish migration regime, and people suddenly find themselves to be violating the law.

The next episode opened with an unprecedented moment that implied de facto infringement of the EU’s outsourced border policies and engineered migration at the Greek-Turkish border (İşleyen & Karadağ, Reference İşleyen and Karadağ2023; Karadağ & Bahar, Reference Karadağ and Bahar2022). On February 27, 2020, another announcement came from the government, stating that Turkey had not received adequate financial support from the EU and would no longer stop displaced persons aiming to reach Europe (Human Rights Watch [HRW], 2020). Right after the announcement, during a single night, the Turkish police, gendarmerie, and border guards were ordered to stand down and let thousands of people rush to the Pazarkule border gate in Edirne at the Greek–Turkish land border. As cited in the reports, the testimonies of nongovernmental organizations who were present in the area hint that removal centers were emptied across the country, with undocumented persons without legal status constituting the vast majority, approximately 13,000 people, at the border gate (International Organization for Migration [IOM], 2020; Karadağ & Üstübici, Reference Karadağ and Üstübici2021). However, there were also Syrians under TPS and non-Syrians under IPS, albeit the minority. People stayed in the buffer zone for a month while they were brutally beaten, assaulted, robbed, and pushed back by the Greek security forces (HRW, 2020). By the end of March 2020, Turkish authorities decided to clear the zone, this time by evacuating the tents and transferring people back to removal centers in random cities. Since these events coincided with the COVID-19 outbreak, people were quarantined in removal centers and dormitories for fourteen days. Strikingly enough, testimonies reveal that they were released from the removal centers in cities in which they did not reside or were registered after quarantine in the midst of total lockdown. None of my respondents had any information about what had happened to those under TPS or IPS, that is, whether they lost their existing status or not. The Pazarkule events, symbolizing an orchestrated mobility at the borders, exacerbated the already existing precarity of displaced populations. Since then, the city of Edirne at the Greek–Turkish border has been witnessing hypermobility that circulates around Istanbul, border villages in Edirne, and the Evros river, with many eventually being pushed back by GreeceFootnote 26.

When it comes to people without any legal status, production of a floating subject materializes in microepisodes every day of their lives. As subjects on the move and deprived of any rights, they constantly rotate from one city to another, despite intercity mobility restrictions, going wherever jobs are available and constituting the cheapest labor force in the country. Some seek to reach Europe but then get pushed back, continuing their journey across the country and taking part in the informal job market until their next attempt to enter Europe or their detention or deportation. These two latter acts might come at any time in their daily lives, with indeterminant periods of containment following.

There are currently twenty-eight removal centers in Turkey, operating in different twenty-four cities and holding approximately 20,000 persons.Footnote 27 The construction of new centers and refurbishment of reception centers as removal centers have been undertaken using the EU budget as part of the EU–Turkey Deal.Footnote 28 From a legal perspective, when an undocumented person is intercepted by the police on the street, they are first taken to the police station. After assessing fingerprints and an identification process, the police transfer files to the PMM as the institutional body that determines whether administrative detention (six months maximum to be extended for an additional six months) or deportation is called for, based on the scope of Articles 54 and 57 of the LFIP. According to the lawyers, this procedure, aside from its arbitrariness, contrasts with the state of administrative law from the very beginning:

[T]he first problem in terms of legality is that the decisions of administrative detention are taken by an unauthorized institution, which is the PMM […] Lawlessness starts from here: The law says that the decision of an administrative detention shall be taken by the Governor’s Office, but in effect it is the PMM that takes the decision. It is based on the transfer of authority protocol made between the two offices. I constantly voice the unlawfulness of this practice and make legal objections, but they are ignored by the courts.Footnote 29

Once someone is put under administrative detention in a removal center, nobody knows what will happen next. The duration of stay and whether they will be released or deported are unknown and subject to numerous dynamics: the ability to communicate with officers in Turkish, whether or not they are pressured into signing the voluntary return form, the financial arrangement of the charter flights (supported by the IOM budget), the occupancy rate of removal centers, the number of available seats in the buses taking people to another removal center, and so on.

It needs to be underlined that the very act of detention is not exercised for its actual outcomes, but rather it is the potential for detainability, as De Genova (Reference Genova2007) aptly puts it, that operates as a disciplinary form of power. The potential constantly propagates fear, which is not equally distributed. For instance, the testimonies of undocumented Afghans indicate that “proper” looks, proficiency in the Turkish language, and an ability to keep away from trouble might increase the chances of avoiding detention on the street (Karadağ, Reference Karadağ2021). Police checkpoints do not often include workplaces involving construction, manufacturing, restaurants, and sheepherding areas, where displaced persons are generally hosted. And once they are put in detention, some people are released in weeks or months while others are deported. On the official website of the Ministry of Interior, it is stated that 320,172 foreigners have been deported (as of April 2022) “within the scope of the fight against irregular migration” since the EU–Turkey Deal was signed in 2016.Footnote 30 For the lawyers I interviewed, the final verdict is predicated upon the signing of the voluntary return form:

I had two Afghan clients aged eighteen to nineteen; they stayed in Tuzla removal center (in Istanbul) for about two and a half months. The authorities interviewed them regularly every week, tried to persuade them that as there was a search warrant against them, they could not live in Turkey. The clients were patient for two months and did not sign. They could not deport them, then they got them on buses with other 150 people and dropped them off in Edirne [a city at the Greek–Turkish border]. Nobody crossed the border, everybody came back.Footnote 31

For those who have been given a deportation decision, another type of forced mobility can occur: movement between removal centers across the country:

[Though they are detained in Istanbul] there is no official record in their names in Istanbul. They are sent to other cities. Deportation orders for them are made in those cities. After a person is caught, the family usually receives the news when they are taken to another city. Tuzla removal center is also used for the purpose of transfer. There is no payphone, no lawyer, no notary public, no file. Because the file will be created in the province where they are taken, you can hear from the person a week later. You receive a call from the other side of the country, a couple of hours before the deportation.Footnote 32

Since January 2022, especially after the general elections in May 2023, Turkey has entered another episode, which is to a large extent the institutionalization of the return policy. Since the beginning of a series of campaigns on social media launched in 2021, there has been use of phrases such as “there is a deadline for hospitality” and “this is an invasion.” Following the surge of public reaction against refugees in the summer of 2021, the process of dilution and sweeping is now at its peak. Research dated 2021 shows that the most pressing issue for the public is the economy, while the question of refugees comes second (rising to 17.9 percent from 6 percent in 2020).Footnote 33

The current political atmosphere in Turkey has a direct effect on evermore intensifying the speed and magnitude of forced mobility of those holding various legal statuses. As part of the dilution and sweeping policy, numerous provinces and districts were completely closed for registration renewal beginning in February 2022.Footnote 34 Furthermore, Syrians under TPS who do not reside in their province of registration (they are in the thousands, as previously noted), were given forty-five days to reregister in their provinces and notified that their IDs would otherwise be cancelled. “We have entered a period in which temporary protection status has been cancelled very intensely,” noted my lawyer interlocuter. Concomitantly, for undocumented persons (non-Syrians), the PMM announced that deportations were being radically stepped up. They added that the rate of deportation had gone up to 50 percent of “irregular migrants apprehended,” compared with 18 percent in Europe.Footnote 35

The repetitive cycles of im/mobility of displaced populations in Turkey demonstrate the inconceivable number of moving subjects, in the millions, exist in perpetually shifting spatialities and temporalities. The episodic policies turn into a self-sabotaging mechanism whose modes of operation give rise to the materialization of arbitrary power. The borders are changing nonstop while disruptive uncertainty and arbitrariness become the rules.

Concluding Remarks

In his book, Pascalian Meditations, Pierre Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu2000) notes that “absolute power is the power to make oneself unpredictable and deny other people any reasonable anticipation and to place them in total uncertainty.” Bourdieu’s description of “absolute power” here does not necessarily account for the absolute coercion enforced by the sovereign, but the powers that create a wide range of governing techniques that constantly produce precarious subjects. The case of Turkey epitomizes the level of instrumentalization of millions of displaced bodies that are trapped within a temporal lacuna. As their mobility is blocked by European countries, they are sentenced to waiting for indeterminate periods in Turkey, periods that might even exceed their lifetimes.

By turning the spotlight on the EU’s contentious frontier, onto the world’s largest refugee hosting country, this chapter not only shows the devastating fallouts of Europe’s externalization policies that lead to neighboring countries bearing the burden of refugee movements, but also describes the ways in which those countries in turn capitalize on displaced bodies and turn them into a political weapon.

As the political process of disenfranchisement continues, Turkey is sliding ever deeper into realms of lawlessness, and even her own citizens verge on becoming “rightless” subjects in terms of freedom of speech, human rights, and justice. Transforming millions of displaced people into irregularized and floating subjects is accompanied by the native population’s feeling that it is being left to its own fate, while the long-brewing collective anger towards noncitizens is about to boil over. In a context within which civil, political, and social rights are seriously hampered even for its own citizens, we witness a growing affinity between citizens and noncitizens in terms of economic deprivation, civil and political freedoms, and legal precarity. The situation does not result in the total erosion of citizen/noncitizen distinction, but the conditions of lawlessness and hence the undermining of rights lead to the subjection of both the former and the latter to the ad hoc aspirations of decision-makers in Turkey.