The Japanese overran Singapore in February 1942 and then rapidly took control of almost all Southeast Asian sources of natural rubber. This deprived the United States of 97% of its supply of a key material for which it had effectively no domestic sourcing. Other inputs, such as Manila hemp, tin, and a range of strategic and critical metals and minerals also faced wartime supply disruptions.Footnote 1 But for the United States, no other input offered such limited alternate sources of supply or opportunities for substitution. There were simply no satisfactory substitutes for rubber in a variety of critical uses, particularly tire carcasses and treads, the ultimate end use of 70% of rubber inputs.Footnote 2 The severe shortage of natural rubber that resulted adversely affected the ability of the US military to project force and contributed to the disappointing record of wartime manufacturing productivity.

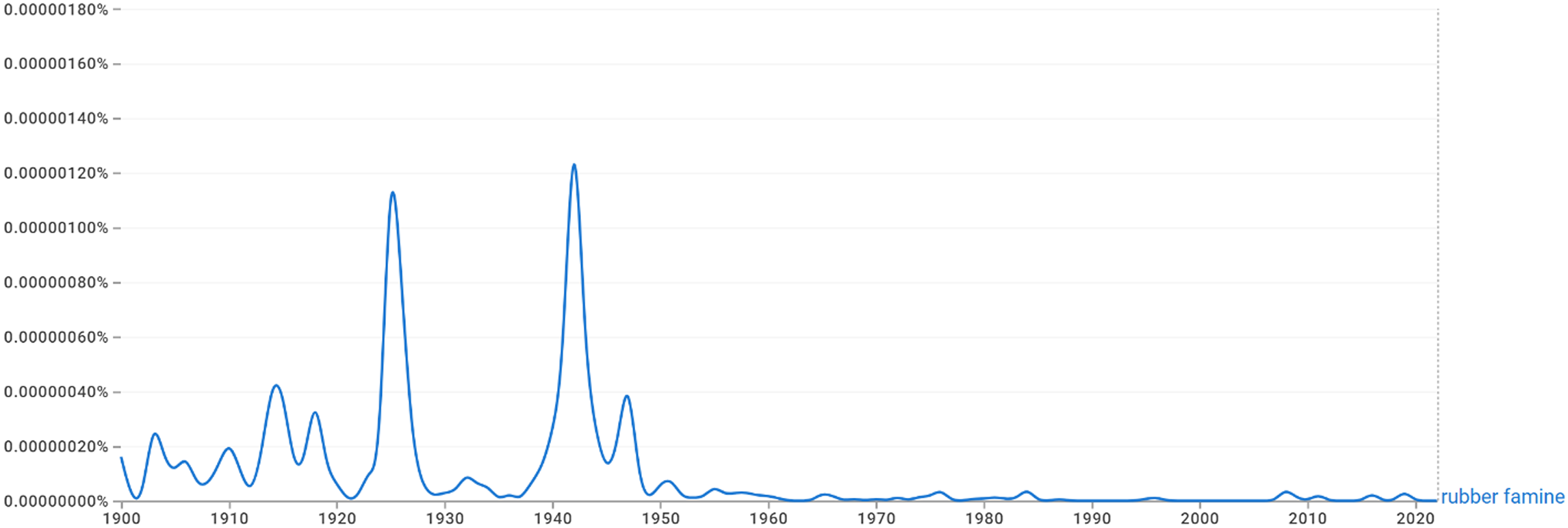

The passage of time has dulled awareness of the famine and its consequences. The challenge it represented was reflected in widespread anticipatory concerns before the war and peaked during it, as a search for the terms using Google’s Ngram viewer illustrates. Figure 1 shows a boomlet during World War I (Britain cut off East Asian exports to the US for two weeks in 1914 until the country agreed not to reexport to Germany via the Netherlands), followed by a boom in the 1920s peaking in 1925, reflecting the success of the Stevenson Restriction Plan, the first of two interwar cartels that drove up the price of the United States’s largest commodity import. References fall off during the 1930s, corresponding to the breakdown and abandonment of the Stevenson Plan in 1928 and the collapse of natural rubber prices during the Depression, but begin to tick up again in 1937 as the prospect of war with Japan loomed larger, with an all-time peak in 1942, the chaotic year in which the prospect of the United States losing the war seemed most possible.

Figure 1. Frequency of references to “rubber famine” in American English-language texts, 1890–2022.

Note: The plot displays, by year, the frequency of n-grams (in this case a 2-gram) in a corpus of printed works in American English, in other words, the fraction of 2-grams that match the identified text string. The search is case insensitive, and the annual data are not smoothed (Google Books Ngram Viewer: https://books.google.com/ngrams).

The subsequent decline of interest in or awareness of the shock has affected even knowledgeable scholars, who have downplayed the challenge it posed to the US economy and Allied war efforts and the ways in which the threat of cutoff could have been more effectively mitigated. The index to one of the most authoritative accounts, Richard Overy’s Why the Allies Won, contains no entry at all for rubber. The material is mentioned once in the text, and there is a reference to a “shortage of tyres,” but it is to a shortage affecting German forces following the D-Day invasion.Footnote 3 Other authors recognize the challenge posed but treat the US synthetic rubber program as obviously the best response and one almost miraculously and effortlessly willed into existence, giving less attention to alternatives and short shrift to the defects in the design and execution of the program. Maury Klein, for example, acknowledged the severe challenge to the economy of the risk of cutoff and the potential benefits of stockpiling but ignored the possible relief an earlier commitment to guayule might have made. And he gives Jesse Jones a pass, not acknowledging his foot dragging on both stockpiling and synthetic rubber.Footnote 4 Paul Koistinen’s analysis is closer to that in this paper, but he also ignores guayule as an option that might have realistically provided an alternate supply of latex had the federal government provided earlier funding for a program of cultivation.Footnote 5

One finds in none of these authors or elsewhere a comprehensive account of the main options for mitigating the risk (and then actuality) of rubber cutoff, why each of these had been pursued in only a limited fashion or not at all at the time of Pearl Harbor, and why the US synthetic rubber program, ultimately chosen as the main route to mitigation, was not the miraculous success it is so often portrayed as. The famine’s history starkly illuminates a policy dilemma still with us: How much insurance should a country carry when it depends heavily on interruptible foreign sourcing of a strategic input?

Despite ex post claims to the contrary, it was widely anticipated before Pearl Harbor that conflict with Japan would very likely result in the loss of almost all supplies of natural rubber. It was also understood that there were three principal means, beyond suppression of consumer demand and encouragement of the use of reclaim, whereby the US might mitigate the risk: (1) accumulate a large strategic stockpile; (2) subsidize domestic production of alternative plant-based sources of latex, in particular guayule; or (3) develop a synthetic capability.Footnote 6 Between 1942 and 1945 the rubber famine aggravated downward pressures on US manufacturing productivity. From a military standpoint, the choices leading to this result threatened the ability of the United States and the United Nations to prevail in the conflict – much more so than the controversial decision to move the US Pacific fleet from San Diego to Pearl Harbor in March 1940.

This paper considers why the strategic stockpile was so low. It explains why the passage of legislation in 1942 providing $45 million for an Emergency Rubber Program based largely on guayule cultivation was too late. And it documents how the design and structure of the synthetic rubber program and the delays in initiating butadiene plant construction exposed the country to potential disaster. In the process, it considers the outsized role played by businessman/politician Jesse H. Jones, as well as the multiple channels through which the rubber famine adversely affected the country’s wartime economy and military capability.

Stockpiling

Stockpiling was the simplest way to protect against the consequences of cutoff. Warehousing entailed no biological/botanical uncertainty about how well a particular plant species might grow under US or friendly country soil and climate conditions. Unlike synthetic rubber, it did not rely on untested engineering or chemical processes. The costs were predictable, and a strategic reserve provided almost perfect substitutes for timely imports of natural rubber. The US stockpile increased from 125,800 long tons (LT) in 1939 to its peak in April 1942 (634,152 LT) with arrival of shipments on their way to the US as Japanese forces completed their seizure of Southeast Asian exporting sites.Footnote 7 This reserve, less than twice what it had been at the end of the Depression year 1932 (379,000 LT), remained woefully inadequate given the wartime needs of the country and its allies.Footnote 8

The USA consumed 591,000 LT of natural rubber in 1939. By 1941, as the country’s negative output gap closed, US consumption had increased to 781,259 LT, and imports had grown to 1,023,631 LT as stocks were accumulated. Then Singapore fell, followed, as war planners and many others had long feared, by almost complete supply cutoff. In the next four calendar years (1942–1945), the United States imported 583,053 LT, barely half of what it brought in during 1941 alone. At the end of 1944, natural rubber inventories stood at just 93,650 LT. Import flows were lowest in 1943, but wartime end-of-year inventory stocks reached their lowest point in December 1944. Had the joint US–British Combined Raw Materials Board not reallocated output from Ceylon (Sri Lanka)—the one Southeast Asian supplier still under Allied control—to the US and the Soviet Union, the US would have run out in that year.Footnote 9

The eventual availability of synthetic rubber in quantity did not end the rubber famine. Synthetic had to be blended with natural in the manufacture of almost all products, and in some cases synthetic could not be used at all.Footnote 10 During World War II, the United States never escaped the threat of running out of rubber, which stood as a sword of Damocles over the entire economic and military effort. In 1944 the country almost ran out of natural rubber and would have, had the war continued into 1946.Footnote 11

Jesse Jones

The inadequate level of the 1942 stockpile owed much to the judgments and decisions of a powerful Washington insider simultaneously occupying multiple institutional positions. Jesse Jones headed the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) from 1933 through 1939, when he resigned as chair to assume the post of director of the Federal Loan Agency. The RFC, along with an alphabet soup of other federal agencies, remained under Jones’s purview throughout the war, with close associates nominally running them. In 1940 he became concurrently (and after a special enabling act of Congress) Secretary of Commerce and, in 1942, at its inception, a member of the War Production Board. Because, up to a very generous debt ceiling, Congress had given the RFC authority to borrow on the full faith and credit of the United States by issuing its own bonds, either directly or through the Treasury, Jones and the RFC had a spending and lending authority more flexible than that of Congress itself. “You’d better see Jesse” was common advice in wartime Washington for those wanting funding for a new program.

After the war, Jones justified his reluctance to build the stockpile more rapidly on the grounds that, if he had bid aggressively, pushing up the world price by even a few cents, the rubber growers, rather than shipping more, would “begin to hold their stocks in the expectation of still higher prices.”Footnote 12 The defect in this justification is revealed in the next chapter of his memoir, which allows that he held a powerful weapon to use in negotiations with the cartel: the threat that the US would develop synthetic rubber. As he wrote in a letter to Roosevelt on September 16, 1940: “they are extremely anxious to sell the rubber and are not enthusiastic about our building synthetic plants.”Footnote 13 Neither, for that matter, was Jones, but those with whom he was negotiating did not need to know that.

In 1940 and 1941, Jones downplayed the likelihood of cutoff, in contrast to the judgments of many knowledgeable observers. Jones, moreover, was wrongly optimistic that, if Southeast Asian shipments were cut, supply from friendly countries in Latin America and elsewhere would prove highly elastic. Above all, he was allergic to ‘wasting’ taxpayer money and was therefore reluctant to spend on the stockpile because he doubted how much was needed and because he awaited the price of natural rubber falling to lower levels.Footnote 14

In June 1941 the Office of Production Management (OPM) increased its stockpile target to 1,200,000 LT, barely half of which would eventually be accumulated.Footnote 15 In summer of that year the Navy and Maritime Commission wished to allow ships to unload Southeast Asian rubber in San Francisco rather than continuing through the Panama Canal to New York, thus permitting vessels to return more quickly to the rubber-producing areas. Jones would not pay the modest additional cost of shipping the rubber across the country by rail. His actions meant that shipping capacity, then in very short supply, was unnecessarily tied up in the San Francisco–New York return transit and less rubber was ultimately brought in.Footnote 16

Jones’s propensity to apply a banker’s mentality to a national security problem is also illustrated by his reaction when a government warehouse in Fall River, Massachusetts, burned down on October 12, 1941, destroying more than 15,000 LT of crude rubber. Jones reportedly exclaimed, in a remarkable display of near-sightedness, given how critical the size of the stockpile would be less than half a year later, “Good thing we had it insured.”Footnote 17 Commercial policies could not insure the country against the full range of possible consequences of loss of US access to Southeast Asian supplies of natural rubber.

As RFC head in the 1930s, Jones played an effective role in liquifying and recapitalizing the US banking system through loans and purchases of preferred stock, a program that ended up (as he reminded his correspondents and the public repeatedly) yielding profit to the US Treasury.Footnote 18 His default practice, from which he could sometimes be dislodged if pressed hard enough by others with power, was to loan conservatively on good collateral at robust rates that made it unlikely the RFC would lose money. What mattered most was avoiding an accusation that he had disbursed funds in what might be judged an imprudent fashion. Jones “had no philosophical objection to state capitalism as long as it wasn’t bad capitalism… Jones would not risk money on bad loans.”Footnote 19 That record, and his reputation for probity and conservative management, was the key to the high levels of esteem in which he was held by members of both political parties in Congress. This, along with his close personal relationship with Roosevelt, underlay the power and influence he wielded in Washington.

Jones made a fortune in lumber, tobacco, newspapers, and banking and as a hotel and commercial real estate developer in Houston and New York City, playing a major role in the development of Houston as a city and inland port. Politically astute, he operated at the pinnacles of American economic and political society, despite having left school after the eighth grade. Intimately familiar with borrowing and lending, both as a consumer and provider of financial services, he held strong views about what constituted sound business and banking practice. Herbert Feis wrote that he and others at the State Department wished to pursue purchases more aggressively but were thwarted by Jones, who placed sharp limits on what Rubber Reserve would pay.Footnote 20 Jones “hoarded the Rubber Reserve Corporation fund, searching for bargains that did not exist because war was inflating commodity prices.”Footnote 21

Jones enjoyed positive press during most of the 13 years he spent in Washington. But his management of the threat and then actuality of rubber shortage coincided with the worst press and Congressional criticism he received during his career, as well as a physical altercation with longtime antagonist Eugene Meyer, former head of the Federal Reserve System, first head of the RFC, and publisher of the Washington Post. Meyer had published an editorial two weeks earlier sharply critical of Jones’s management of the rubber crisis.Footnote 22

Aside from stockpiling, Jones also balked at funding a synthetic rubber program, beyond perhaps the construction of small experimental facilities.Footnote 23 For all his success in the private sector and then as a government banker, Jones lacked the experience to design—let alone evaluate the merits or size of—a proposed synthetic rubber industry. When confronted with a program offered by an oil company with an interest in its evolution, Jones acted to stall its forward momentum and appears to have influenced or at least reinforced Roosevelt in taking (at least initially) a similarly skeptical view of its necessity. Questions about the choices reflected in Standard Oil of New Jersey’s proposal can justifiably be entertained, but blocking its advance demanded, under the circumstances, articulation of something to take its place. Jones exhibited little interest in assembling within his staff the disinterested technical competencies that might have helped him develop an alternative.

By November 1940 a program reflecting Standard Oil’s blueprint had advanced to a planning stage and was moving forward. In February 1941, Jones cancelled it, defending his action on the grounds that he did not want to waste government money on “expensive plants,” except in an “extraordinary emergency,” which in his judgment did not then exist. Jones believed he knew oil (both the industry and the men) and acted, he thought, to protect taxpayers. On February 26, 1941, Standard’s CEO received the memo explaining this, which included the claim that the RFC had accumulated a stockpile of natural rubber sufficient “to carry us for three years.” That claim, which could be supported only under the most extraordinary assumptions, was developed by William L. Clayton, Jones’s deputy, and presumably reflected the judgments of his boss.Footnote 24 In March, Jones backtracked in response to protests about the cancellation, proposing that each of the Big 4 rubber product manufacturing companies be given funds to build a small, 2,500-ton per year demonstration plant to gain experience with copolymerization. But there was no funding for butadiene production, expenditures on facilities for the production of which would ultimately consume about half the government investment in the synthetic program (construction of copolymerization plants cost about a quarter).Footnote 25

In subsequent testimony before the Gillette Committee that year, Jones stated that “the RFC only carries out policies, it does not formulate them,” which might have been true formally but was not so in practice.Footnote 26 Relying with great confidence on his own judgment, he ended up hamstringing both the stockpiling and synthetic rubber routes to remediation. In testimony before the Truman Committee in 1942, Jones also displayed strong skepticism about the merits of prewar efforts to develop guayule cultivation.Footnote 27 Guayule, the third route to mitigation, escaped some of Jones’s restraining influence because it was in the Department of Agriculture’s bailiwick, headed until 1940 by his rival Henry Wallace (who then became vice president). Nevertheless, by the time funds were appropriated for guayule by Congress, it was too late.

A Counterfactual

The synthetic rubber program produced approximately 3 billion pounds (1.34 million LT) of synthetic during the war.Footnote 28 Most of this was Government Rubber-Styrene (GR-S), where it would substitute for natural rubber.Footnote 29 If the stockpile had been that much higher than its maximum in April 1942 (634,152 LT), it could have obviated the need for the entire wartime output of the synthetic rubber program, with the additional bonus of avoiding the milling penalties of working with synthetic–natural blends in fabrication.

The world price of natural rubber remained at or below 20 cents/pound prior to US entry in the war. Southeast Asian suppliers had, in the aggregate, substantial excess capacity, which is part of what had incentivized the creation of the two interwar cartel schemes. More could easily have been produced. We can assume that the US would have continued to accept contractual language limiting its ability to dump its stockpile in the event it avoided war. The conclusion is that about $600 million spending on additional stockpiling could have replaced the entire wartime output of the US synthetic rubber industry (3 billion × $0.20 = $600 million).

As of June 30, 1942, the US stockpile of natural rubber was stored in 135 warehouses around the country.Footnote 30 These facilities needed temperature control, protection against ultraviolet (UV) damage from sunlight, and sprinkler systems with adequate water pressure. Labor requirements were modest—mostly armed security guards—as were requirements for interior furnishings or equipment, certainly compared with any of the synthetic plants constructed. Natural rubber in storage deteriorates but has a recommended shelf life of between three and five years. Standard storage costs were $120/ton in and out and $.50 per ton per month ($6 per ton per year).Footnote 31 In and out costs would have been about $160 million ($120 × 1.34 million). Adding $20 million for storage of what would have been a declining stock over a four-year period, for total warehousing costs of $180 million, would bring total acquisition and storage costs to $780 million ($600 million + $180 million), about the cost of construction of the 51 plants comprising the synthetic rubber program ($700 million).

In addition to plant construction, the synthetic program required about $2 million/day to operate.Footnote 32 Calculating two years of expenses (365 × 2 × $2 million = $1,460 million) brings us to a combined construction and operating cost for the US synthetic rubber program of slightly more than $2 billion ($700 million + $1,460 million), as much as was spent on the Manhattan project. Relying entirely on stockpiling could have resulted in net savings of approximately two thirds of a Manhattan Project ($2.160 billion − $ .780 billion = $1.38 billion). The lower cost of stockpiling is only part of the benefit that would have accrued entering the war with a larger stockpile, which would have supplied a substitute that, in addition to avoiding the time and labor milling penalty, was far less risky in terms of if or when it could actually be accessed.

Other Foreign Sourcing and the Guayule Alternative

One reason the loss of access to Southeast Asian rubber was potentially devastating to the US was that the country had virtually no domestic sources of latex and because there was hardly any supply elsewhere in the world not then under enemy control. (The other main reason was inelastic demand for rubber in the production of final products such as tires). Remaining annual production available to the United Nations from Africa, South America, or Mexico could have satisfied just two weeks of US consumption in 1941.Footnote 33 Hevea brasiliensis, the preferred source of natural rubber, requires a moist, warm climate generally found near the equator.

As compared with the exploitation of wild Hevea, plantation cultivation offered the promise of higher yields per acre because of much higher density and the opportunity to raise yields per tree through selective bud grafting and vegetative propagation from cuttings.Footnote 34 Plantation cultivation, however, had not and has not been successful anywhere in the Western hemisphere. Henry Ford made the most ambitious attempt, obtaining a land grant from the Brazilian government of 2.5 million acres located 600 miles up the Amazon and about 190 miles south of Santarém. Beginning in 1928 his organization planted seedlings on thousands of cleared acreage and built Fordlandia, a transplanted midwestern company town replete with schools, hospital, swimming pool, cafeteria, golf courses, and suburban-style housing for his managers.Footnote 35 His efforts were ultimately stymied by insensitivity toward his Brazilian workforce, but more fundamentally by a microorganism (Microcyclus ulei) that causes leaf blight and eventually killed the trees.Footnote 36 In 1934, acknowledging defeat, the company persuaded the Brazilian government to trade 700,000 acres of the original grant for a new site (Belterra) closer to Santarém and began anew. It looked initially as if the second effort might be successful. But the resistant strains proved to be low-yielding, and the plantation continued to struggle with leaf blight. In 1945 Henry Ford II sold both parcels back to the Brazilian government at a loss to the company over the 17-year period of about $20 million.Footnote 37

Ford’s failures are consistent with the conclusion that the US could not and cannot expect cheap plantation rubber to be grown anywhere in the Western hemisphere. Harvey Firestone had more success in Africa, persuading the Liberian government to grant him a 99-year lease on 1 million acres of Firestone’s choosing and, on them, creating the world’s largest rubber plantation.Footnote 38 Firestone’s Liberian operations began in 1926 and continued to operate almost a century later, sometimes at reduced capacity depending on the state of the world rubber market and Liberian internal political conflict. After Pearl Harbor, Rubber Reserve contracted with Firestone for the entire output of the Liberian operation. In 1943, the year of the USA’s lowest imports, these holdings supplied almost a quarter (23%) of a greatly reduced flow of imports, but this was never enough to account for more than about 2% of overall US consumption.Footnote 39

That left hemispheric wild rubber. In Spring 1942 the US negotiated agreements with 26 South and Central American governments, calling for those countries to provide the US (at a negotiated price) all their rubber production beyond that required for domestic consumption. Like the Liberian contract, this program succeeded in covering only a small fraction of US wartime consumption needs.Footnote 40 US consumption (synthetic and natural) totaled 488,535 LT in 1943 and 710,783 LT in 1944. Of this, Latin America provided 26,200 LT in 1943 (5.4%) and 32,800 LT in 1944 (4.6%). This contrasts with earlier confident predictions for 1942 of 75,000–100,000 LT from Latin American wild rubber, and for 1943 and 1944 of 60,000 LT and 120,000 LT respectively. As Wendt concludes, “The Western Hemisphere natural rubber program was not a success.”Footnote 41

Neither wild nor plantation grown rubber in the Western hemisphere or Liberia would alleviate the US rubber famine. After imports from South Asia ceased to be available, stockpiling was no longer an option, and setting aside synthetic rubber, the remaining possibility was to increase the cultivation within the US of other plant-based sources of latex. The most promising of these was guayule (Parthenium argentatum). In the first decade of the twentieth century wild guayule had a record of successful commercial exploitation by the Intercontinental Rubber Company (IRC), which numbered among its investors a pantheon of Wall Street notables including Nelson Aldrich, Bernard Baruch, Daniel and Sol Guggenheim, Jacob Schiff, and John D. Rockefeller Jr. The IRC operation in Mexico, through its operating subsidiary, the Continental Mexican Rubber Company, harvested and then, using a capital-intensive process patented in 1904, extracted rubber from the plants. Polished stones in rotating drums crushed the leaves and stalks. The output was placed in settling tanks, where the rubber floated to the top and was then dried in sheets.Footnote 42 Production increased sharply between 1905 and 1910, and in the latter year guayule provided the raw material for almost a fifth (19%) of US manufactured rubber goods. The IRC eventually controlled over 3.8 million acres in Mexico, giving it a practical monopoly of the shrub’s natural habitat.

Wild guayule’s contribution to US rubber consumption in 1910 was impressive, but there are questions about how sustainable it might have been, given that extraction of rubber from the plant could be done only once, as opposed to Hevea, which could be tapped again and again for decades. In any event, beginning in 1911, Mexican revolutionaries repeatedly disrupted operations at the Torréon facility, and in 1916, the IRC took seeds to the US with the intent of converting the wild plant into a domesticated cultivated crop, planting acreage in southwestern Texas near Laredo, south of Tucson, Arizona, and, in 1926, in Salinas, California. During the spring of 1930, following an invitation from the company, the US Army detailed an obscure major named Dwight D. Eisenhower to visit IRC operations in California, Texas, and Mexico as part of a two-man team. The diary of his visit and his official report are available in his published collected papers.Footnote 43

Eisenhower toured cultivated acreage in Texas and California (Salinas) as well as the remnants of the IRC facilities in Mexico used to process wild guayule, where he also observed the mixed success with attempts to reseed the semiarid terrain. Eisenhower was one of many who correctly feared what would happen in the case of war with Japan. As he observed in his 1930 report to the Assistant Secretary of the Army, “Should our sea communications with [Southeast Asia] be cut in an emergency, shortage of rubber in the United States would rapidly become acute.”Footnote 44

In his report, despite his earlier diary observations, he was no longer optimistic that market forces themselves would bring forth a large supply of irrigated guayule from independent farmers. Moreover, the market risks faced by the IRC made it unlikely that the company would undertake a major expansion on its own account, nor were there other companies in the US with the experience in cultivation and processing that would likely do so in its stead. And he concluded that the US could not rely on revival of a substantial supply of rubber from Mexican guayule owing to the insecurity of property rights in that country and uncertainty about the success of efforts to reseed wild guayule.

These considered judgments lead him to propose subsidization of guayule cultivation in the US, listing seven reasons why this might benefit the nation. The first was that it would reduce dependence on Southeast Asian supplies that could be interrupted by war or restricted by cartelization. He considered the employment benefits during a depression of providing additional jobs for farmers, workers, and mechanics and noted that in 1930 the US was spending $200–300 million annually to pay for rubber imports, the top commodity import by value during the interwar period. He commented on the benefits of shifting acreage away from crops like cotton, corn, and small grains that produced more than the US needed toward the production of an input for which the country was almost entirely dependent on imports. And he noted that the IRC had several decades of experience harvesting and processing guayule, that the plant had been studied extensively, and that the semiarid regions most suited to its cultivation were not well suited to the cultivation of other crops. Finally, he observed that adding even 10% to the world supply of rubber would drive down the price of Hevea, which would benefit the US to the degree it continued to import natural rubber. He therefore proposed that the government subsidize 400,000 acres of cultivated guayule. This would enable the annual production of about 71,400 LT of natural rubber.

Eisenhower’s report vanished into oblivion, its journey to a final resting place speeded on its course by the collapse of rubber prices in the worst years of the Depression.

A Second Counterfactual

A second counterfactual illustrates the difference implementation could have made. Suppose 100,000 acres had been planted each year beginning in 1935. Starting in 1939, a fourth of the cultivated acreage could have been harvested, processed, and replanted annually, with the harvest stockpiled. Between 1939 and 1945, this would have yielded an annual flow into storage of 71,400 LT a year, making unnecessary the production of 428,400 LT of synthetic rubber, about a third of total actual wartime production. This could have complemented a more aggressive pre-Singapore program of importation, requiring an increment to stockpiled imports of only 1.5 times the peak amount stored, that, together with the guayule, would have obviated the need for any synthetic, again with the advantage that guayule, unlike GR-S (and along with imported stockpiled rubber), did not entail the time and labor milling penalty. Guayule was close to a perfect substitute for Hevea in most uses, and superior in some. The costs of the guayule share of the replacement would have been higher than imported Hevea, but there would have been some compensating reductions in warehousing costs, and the supply, since it came from the continental US, would have been secure.

After Singapore was overrun, the US government had second thoughts about guayule, and three weeks later Congress passed the Emergency Rubber Act (March 5, 1942), sometimes known as the Guayule Act. The legislation appropriated $45 million, and authorized buyout of the IRC facilities, intellectual property, and acreage in Salinas, and a total of 50,000 acres in guayule on government-owned or -leased land—an authorization increased in panic to 500,000 acres in October 1942, following the release of the Baruch (Rubber Survey) Committee report. This would permit an estimated annual harvest of 80,000 LT a year.

These numbers are close to those that would have resulted from implementation of the Eisenhower plan. But it was too late. Guayule plants take four years to mature. Farmers pressured into Emergency Rubber Project contracts to grow guayule soon wanted out so they could grow more profitable cash crops. Most of the acreage planted was eventually plowed under before it could yield much rubber.Footnote 45

Thomas Edison, who spent the last four years of his life researching plant-based alternatives to Hevea, was never a fan of guayule as an emergency rubber source for the same reason: The plant took too long to reach maturity.Footnote 46 Had some version of Eisenhower’s plan been implemented earlier, however, mature plants would have been available for harvesting well before 1942.

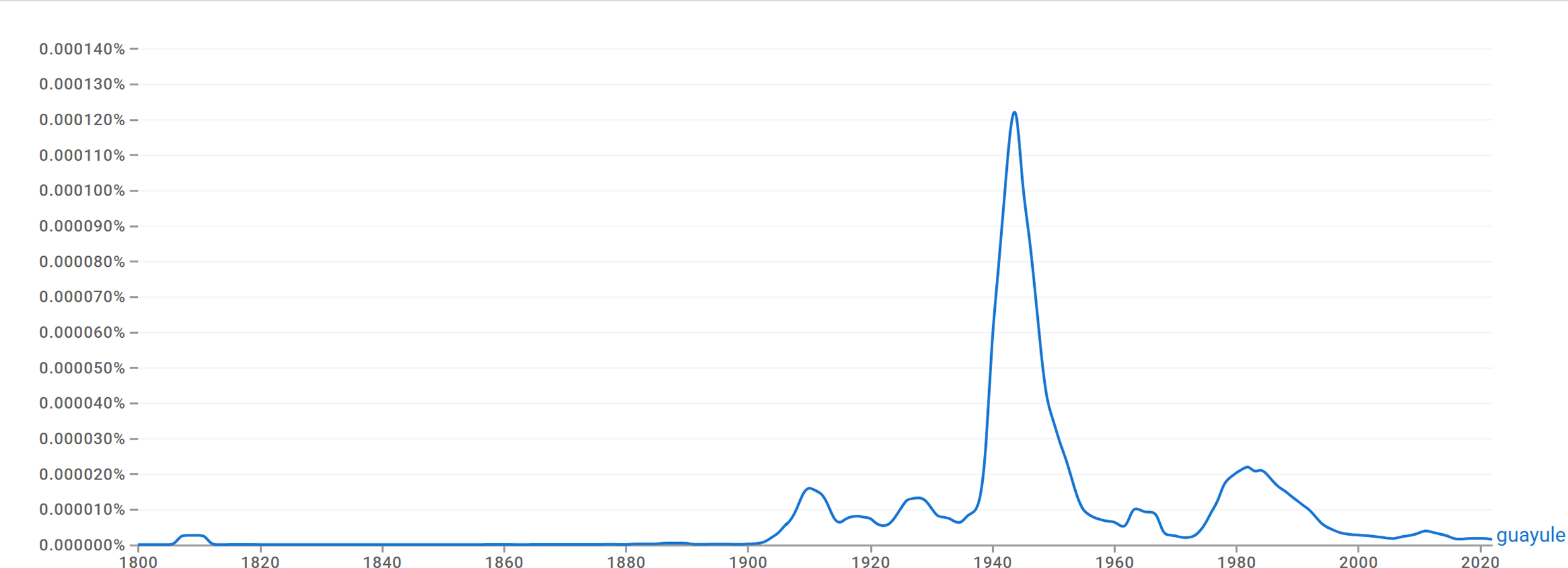

A Google Ngram search reveals how serious was interest in guayule during the war (see Figure 2). The initial peak in 1910 corresponds with the success of the activities of the Intercontinental Rubber Corporation prior to the shutdown of facilities due to revolutionary activity in Mexico. The increased frequency of references in the 1920s corresponds exactly with the success of the Stevenson plan in jacking up the world price of natural rubber, and the decline of references in the first half of the 1930s with the Depression era collapse in its price. The spike in references during the war peaks in 1943, the year of maximum US military production. (The 1980s boomlet reflects the discovery that items made from guayule, such as disposable gloves, could be a viable alternative for those allergic to latex).

Synthetic Rubber

In 1939, when war broke out in Europe, it was not too late for stockpiling but almost too late for guayule. By March 1942 it was too late for either. The two counterfactuals discussed above are no longer relevant because the contemplated actions were no longer possible. A synthetic rubber program was now unavoidable if the country was to prosecute the war successfully. Such a program was under discussion by the Army and Navy Munitions Board beginning in early 1939. Representatives of Standard Oil (NJ) met with the Board repeatedly during that year and sketched out a program that, with some modifications, reflected the design ultimately embarked upon.Footnote 47 The design and execution of that program has, as has so much about the US economic mobilization effort, been uncritically lionized.Footnote 48 The underlying chemistry was well understood, but there was limited experience with the processes that stood at the center of Standard’s blueprint, which relied exclusively on petroleum as the source for butadiene.

There was consensus ex ante that the risks of war with Japan were high and, conditional on a state of war, that the probability of losing access to Southeast Asian rubber was even higher. When examined from the perspective of national security, two synthetic rubber program decisions look questionable both in prospect and in retrospect.

The first was to design the program heavily around the use of petroleum rather than alcohol as the precursor for the butadiene that would be copolymerized with styrene to make GR-S. Butadiene had no other commercial uses, so there was little experience manufacturing it and no option of diverting existing production flows from less essential uses. The second is the more than a full year delay in beginning to build the butadiene plants after the basic design of the program had been set in November 1940. Supplying butadiene in large quantities was widely understood to be the most problematic part of the synthetic program, of far more concern than the copolymerization plants. At the time of Pearl Harbor, construction had begun on none of the butadiene plants.Footnote 49

The design of Standard’s initiative was heavily influenced by the commercial interests of oil companies, particularly Standard, in having the government lay the foundations for a synthetic rubber program that might or might not be profitable in the postwar period but, if it were, would provide a market for byproducts of crude oil refining. The emphasis on petroleum as the exclusive precursor for butadiene reflected that interest, but it did so at the cost of jeopardizing the national (and Allied) objective of winning the war. The design decisions, in the event, did not cause the war to be lost, but they made the economic situation more precarious than it needed to be, even after March 1942, when the necessity of some synthetic rubber program became a given. This in turn constrained the ability of the US and its allies to project force, especially in 1943.Footnote 50

Goodrich and Goodyear had experimented with synthetic rubber before the war, trademarking their products as Ameripol and Chemigum, respectively. Standard viewed these as versions of Buna-N—a synthetic based on the copolymerization of butadiene with acrylonitrile rather than styrene.Footnote 51 Standard claimed that, through its patent exchange agreements with IG Farben, it had US rights to this product, as well as GR-S—the US nomenclature for what the Germans called Buna-S. Through legal pressure prior to Pearl Harbor, Standard forced a wartime standardization on GR-S, a general-purpose rubber suitable for tire treads and carcasses. To make GR-S, one needed styrene, which was manufactured commercially, and butadiene, which was not.

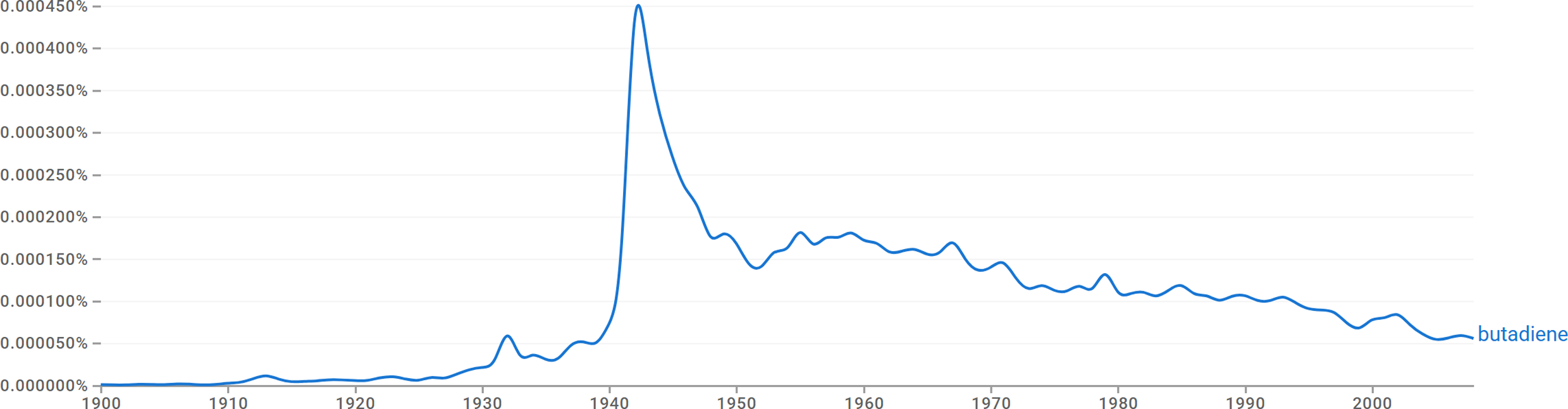

Butadiene is infrequently mentioned in discussion today. The opposite was true during the war, as Figure 3 shows. A gas, it could be obtained in multiple ways. The process preferred by Standard worked from isobutylene, a byproduct of its oil refineries. It could also be made from butane or from naphtha, both of which could also be byproducts of the distillation and refinement of crude oil, depending upon how the crude oil was cracked. Butane is also abundant in natural gas. And finally, butadiene could be produced from industrial alcohol (ethanol), which could be obtained either from fermentation of plant material or synthesized from petroleum.Footnote 52 The butadiene would then be copolymerized with styrene in a 3:1 ratio to make GR-S.

Neither copolymerization nor additional manufacture of styrene was anticipated to pose serious problems, and they did not. The big question was butadiene, particularly because the process favored by Standard was untested. Yet the original design of the program was built entirely around the use of petroleum rather than ethanol as feedstock. Once the program had been designed along this route, and in the absence of an alternative, its execution was delayed, and once again, Jones’s skepticism about the severity of the threat played a role.

The first part of Table 1 documents the impact of Jones and the RFC in delaying the construction of plants to produce butadiene and in general acting to block or slow the development of a synthetic rubber program, until overruled by William Knudsen at the Office of Production Management. We also see the frantic increases in the targeted size of the program starting in early 1942, as the full scope of the looming disaster became apparent. The timeline also documents the belated willingness, under the War Production Board (WPB), to allow some of the butadiene production to come from plants using ethanol. The first butadiene plant was not completed until April 1943. All three of the big alcohol plants opened that year, and they produced far more than their rated annual capacity. Of the five petroleum-based butadiene plants, the three largest did not begin production until 1944, and consistently produced below their rated capacity.

Table 1: Key Dates in the Evolution of the US Synthetic Rubber Program, 1939–1944

Sources: 1939–1942: US Senate, Hearings before a Special Committee Investigating the National Defense Program. Part II. March 5, 24, 26, 27, 31, April 1, 2 3, 7, 1942. Rubber. Seventy-Seventh Congress. (Washington, DC, 1942), 4553; Robert A. Solo, Synthetic Rubber: A Case Study in Technological Development under Government Direction. Committee on the Judiciary, US Senate, 85th Congress, 2nd session (Washington D.C., 1959), 19.

1943–1944: US War Production Board, Special Report of the Office of the Rubber Director on the Synthetic Rubber Program: Plant Investment and Production Costs (Washington, DC, 31 Aug. 1944), Table II, 4; Paul Wendt, “The Control of Rubber in World War II,” Southern Economic Journal 13 (1947): 209.

Of the total 425,360 LT of butadiene produced up through and including June 1944, the month of the D-Day invasion, 321,370 LT was produced by the alcohol-based plants. The four isobutylene-based petroleum plants listed on the timeline provided just 64,570 LT.Footnote 53

A Third Counterfactual

Given earlier inaction or inadequate action on stockpiling or guayule, the delays in butadiene production were one of a number of factors (shortage of landing craft was another) making near impossible the execution of a successful cross-channel invasion in 1943, as originally planned.Footnote 54 US rubber consumption (all sources) fell from 781,258 LT in 1941 to 394,442 LT in 1942 before rising to 488,525 LT in 1943 and then 710,783 LT in 1944. Assume that the difference between 1944 and 1943 consumption (222,258 LT) roughly represents the additional requirements of a cross-channel invasion counterfactually moved back in time by one year and that Lend Lease continued at actual 1943 levels, as did military action in the Mediterranean/Italy, China/Burma, and Pacific theatres. The natural rubber stockpile had already fallen to 139,594 LT by the end of 1943. The country could not have squeezed more natural rubber imports from Africa and Latin America in 1943, or it would have done so, and the same was true of synthetic production, given Jesse Jones’s earlier obstructionism. Even if the 1943 end-of-year stockpile had been entirely depleted in support of an earlier cross-channel invasion, there remains a gap of 82,644 LT, or about a third of the delta, for which no alternate sources in 1943 can be identified. As it was, in 1944 the military was forced to strip tires from domestic motor pools and ship them to Europe and take delivery of vehicles without spares and in some cases without tires.Footnote 55

Without alcohol-based butadiene, it is hard to see how D-Day could have gone forward in June 1944. In retrospect, it is not clear that petroleum-based butadiene was needed at all to win the war. Butadiene from isobutylene was cheaper in the long run because, even though plants using this input were more expensive to construct, required more complex engineering, and relied on untested processes, the feedstock (petroleum) was ultimately cheaper. Due to huge agricultural surpluses accumulated during the Depression, however, the opportunity cost of ethanol was far lower during the war years, an advantage augmented by the much lower capital requirements of the process using it to produce butadiene.

The US government ended up establishing the foundations for a commercially successful synthetic rubber industry in the postwar period, one using petroleum as the principal feedstock, as Standard intended. Given that synthetic rubber would be needed during the war, it would have been cheaper and faster to have focused from the outset on ethanol as the feedstock. Standard Oil bears responsibility for the emphasis on petroleum. Whether petroleum or ethanol was to be the feedstock, however, construction on the butadiene plants should have started earlier, and for that, Jones bears much of the responsibility.

The Economic Effects of the Rubber Famine

Total factor productivity in US manufacturing declined between 1941 and 1948 and fell even more sharply between 1941 and 1945. The main cause was the transition from making goods with which manufacturers had a great deal of experience to those with which they had little.Footnote 56 The effects of the product mix changes would have been serious even had there been no additional disruptions. But there were additional disruptions.

Aside from Pearl Harbor, US territory did not suffer from a major attack during the war. A Japanese submarine ineffectively shelled oil storage tanks near Santa Barbara in 1942, and in 1945 six people were killed in Oregon by an incendiary bomb carried by balloon on air currents from Japan.Footnote 57 Nevertheless, enemies disrupted the US productivity trajectory through means other than simply forcing changes in the product mix. The Germans did so via U-boat predation, shutting down the “tanker pipeline” that brought petroleum and petroleum products from East Texas and Louisiana to the Eastern seaboard.Footnote 58 But of all enemy-inflicted supply disruptions, the Japanese cutoff of Southeast Asian rubber proved the gravest threat to the US economy and its military capabilities. The resulting famine combined limited opportunities for substitution of the refined material in production of final products with limited opportunities for alternate sourcing of the raw material, or production of substitutes for it. The effects potentiated each other, resulting in a very high cost of remediation.Footnote 59

The rubber famine’s negative impact on productivity (efficiency) operated through multiple channels, both within the manufacture of rubber products and in the expanding industry producing synthetic substitutes for the raw material. Synthetic rubber (GR-S) was not a perfect substitute for natural, lacking its plasticity and tack. When flexed and allowed to return to its original shape, it generates more heat than natural rubber.Footnote 60 The manufacture of almost all products, especially airplane and heavy truck tires, required blending synthetic with natural or, in some cases, could use no synthetic at all, which is why the supplies of natural rubber remained so critical.Footnote 61 In the final stage of tire fabrication (where natural and synthetic was blended along with additives and fillers and then vulcanized), mixtures of synthetic and natural rubber took longer to mill and required up to a third more labor time as compared with using all natural rubber.Footnote 62 The Baruch report noted this and, as a consequence, anticipated a shortage of milling capacity in 1943 and 1944, which is precisely what happened. The constraint began to bind in January 1944 and continued through August, placing a hard cap on the total amount of rubber, synthetic and natural, that could be processed into final products. In the remainder of 1944, shortages of labor limited rubber product manufacture, as did a critical shortage of carbon black in the first half of 1945 that forced a cutback from seven to six days of weekly production.Footnote 63 Any uptick in production intermittency reduced total factor productivity by reducing capital productivity since the capital service flows continued mostly uninterrupted, independently of the intensity of utilization.Footnote 64

Even after the program changes made in 1942, the design of the synthetic program heavily favored petroleum as the feedstock for butadiene. Priority claims on boilers, valves, pumps, heat exchangers, metals (particularly stainless steel, which needed chromium and nickel to manufacture), and other construction material and manpower were far in excess of what would have been necessary had alcohol played a more prominent role in program design.

In most cases the rubber program had priority access to subassemblies and materials, a preference which the Petroleum Administrator for War (Harold Ickes) bitterly resented and sometimes overcame.Footnote 65 The more timely completion of the alcohol plants reflected the reality that capital requirements were lower and the engineering less complex, placing less strain on supplies of construction materials, subassemblies, and specialized materials. Conflict with the aviation fuel program also probably played a role in prioritizing delivery of the more limited capital requirements for the alcohol plants and delaying completion of the petroleum-based butadiene plants. Isobutylene from refinery operations could be used to make either butadiene or toluene. The aviation program needed toluene to make 100 octane fuel, which permitted the operation of high-compression engines.

If, by privileging petroleum as the feedstock, the rubber program obtained materials or construction labor it could have done without, it starved other sectors of scarce inputs. If it failed to get the inputs it needed, conditional on the design of the program, synthetic rubber supplies were delayed. In either case the result contributed to output intermittency, an affliction that dragged down productivity and product completion rates throughout the war. The rubber famine led directly to the imposition of a 35-mph speed limit and nationwide gas rationing in a country that, in the aggregate, was awash in petroleum. The intent was not to save fuel but to reduce tread wear on the tires installed on the nation’s 27 million automobiles and 5 million trucks, almost all of which were otherwise forecast to be off the roads within two years.Footnote 66 These restrictions made it more difficult for people to get to and from work, contributing to absenteeism, and impacted the distribution of products by truck.

Prior to the war the country enjoyed cheap and reliable delivery of hundreds of thousands of tons annually of Southeast Asian natural rubber. In response to the cutoff, the production of synthetic rubber required building 51 plants at a cost of about $700,000,000 and spending millions more to operate them. Synthetic rubber yielded, at great expense, an imperfect substitute for natural rubber that required additional labor in final product fabrication.

The Rubber Survey Report (September 1942) repeatedly stressed the severe threat posed by the rubber famine. It emphasized how critical the availability of synthetic rubber would be in 1943, and planned/promised 400,000 LT of GR-S. Because of the delayed completion and poor initial performance of the petroleum-based butadiene plants, less than half that amount was delivered. The Soviet victories at Stalingrad and Kursk gave the Allies breathing space, allowing delay of the cross-channel invasion, which irked the Soviets but was welcomed by the British. In the event, as noted, rubber shortages that year probably made a successful cross-channel invasion impossible. During the following year (1944) synthetic production began to approach the expanded GR-S targets set during the panicked months of 1942. Now, the complementarity between natural and synthetic began to bind, and as the natural rubber stockpile shrank to dangerously low levels, unusable stocks of synthetic accumulated.

Conclusion

The blue-ribbon committee appointed by Roosevelt to survey the rubber situation did not mince words in its September 1942 report: “If we fail to secure quickly a large new rubber supply, our war effort and domestic economy will collapse.”Footnote 67 In May 1942 Ferdinand Eberstadt had used similar language in a letter he wrote to Bernard Baruch: “unless synthetic rubber is available in quantity by the time the crude stockpile is exhausted… we would appear to have no alternative but to call the whole thing off.”Footnote 68 There are no qualifiers here nor reason to believe that the language was hyperbolic, nor reason, with the benefit of hindsight, to doubt their judgment.Footnote 69

The magnitude of the threat to the US may nevertheless still strike some readers as difficult to credit. A celebratory imperative emerging out of the evident victory of the US and its allies has dulled our critical sensibilities in thinking about the economic history of the war, and this aspect of it is no exception. The rubber famine has largely faded from US consciousness, and many are not aware that it really was a very serious thing.Footnote 70 For those who know more of the history, skepticism persists because of two related beliefs, both false: first, that the synthetic rubber program was almost effortlessly willed into existence—the terms “miracle” and “miraculous” often feature in discussions of it—and second, that once it was available, synthetic was an almost perfect substitute for natural rubber. Synthetic rubber had to be blended with natural in the manufacture of almost all products—imposing a time and labor cost milling penalty—and for some products such as airplane tires, only natural rubber could be used.

By 1944 GR-S was finally available in quantity, but at that point the rapidly dwindling stockpile of natural rubber became the binding constraint on overall rubber product manufacture.Footnote 71 The frantic increases during 1942 in GR-S program targets combined with the reliance on petroleum-based butadiene and the delays in building the plants to produce the gas led to a program that underdelivered in 1943 and, in terms of the absorptive capacity of the economy, overdelivered in 1944. In the process of overbuilding capacity using an unnecessarily expensive process, the program sat on or consumed valuable resources needed by other war programs.

The 1944 report of the Rubber Development Corporation emphasized that the increased availability of synthetic in that year did not by any means alleviate the rubber famine: “the need for natural rubber under these circumstances remains as acute as ever, and every effort must be continued to assure that every possible ton will be secured from the sources available to us.” In 1945 the War Production Board forecast that, in the event of an invasion of Japan, the US would simply run out of natural rubber in 1946.Footnote 72 Among other consequences, the US would then have been unable to manufacture airplane tires.

Controls on the consumption of natural (but not synthetic) rubber continued after Victory over Japan (VJ) day.Footnote 73 The frenzied buying and stockpiling of natural rubber by the US at the outbreak of the Korean War offers additional testimony to the imperfect substitutability of synthetic for natural rubber and underlies again how critical was the size of the natural rubber stockpile in 1942. At the start of the Korean conflict, the Preparedness Subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Armed Forces, chaired by Lyndon Baines Johnson, announced that “we must stockpile and conserve rubber as if our very lives depended upon it because that may be the reality.”Footnote 74 Johnson made this statement even though the US government then possessed a large synthetic capability, with abundant access to the necessary feedstocks, all still entirely under its own control.

Taking a broader view, the history of rubber before and during the war highlights the benefits and risks for the US of reliance on global supply chains, particularly for materials of strategic importance. The basic tradeoff—one evident during the COVID-19 pandemic in choices involving vaccine manufacturing supplies and personal protective equipment and immediately after it in the supply shortages due to scarce computer chips—was between the risks of depending on cheap foreign sourcing that might not always be available and the expense and efficiency penalties of stockpiling or developing or retaining standby or operational raw material or manufacturing capacity via subsidies or protection.Footnote 75

What of Jesse Jones’s role in aggravating the World War II rubber famine? To his credit, there is no evidence that he or anyone close to him benefitted financially from his stances. And, following Pearl Harbor and the fall of Singapore, he worked effectively to implement a flawed program. Still, he slowed or stood athwart implementation of two of the three risk-mitigation strategies (stockpiling and synthetic rubber) and would have done so for the third (guayule) had it been within his bailiwick. The consequences for US productivity and the ability of the country to prevail in the war were serious. When we create a system with many checks and balances, we often complain that decision makers are too hamstrung, and nothing can get done, or done quicky. When we grant to or allow a government official to amass great power, we may not always be happy with their decisions or the outcomes. This is reflective of broader tradeoffs that are unlikely to be resolved easily. A country benefits from civil servants who are honest and effective. But it also needs those who can recognize when they need to seek out additional knowledge or expertise, particularly when they are invested with czar-like powers. Roosevelt, though he appears initially to have shared some of Jones’s gut-level judgements and prejudices, eventually realized this and, in the summer of 1942, availed himself of the counsel of Baruch, Conant, and Compton. By then, considerable damage had already been done. The time windows during which two of the three key mitigation strategies (stockpiling and guayule) could be exploited had closed. And the implementation of the third (synthetic rubber) had, beyond its design defects, been seriously delayed.

In September 1942 the distinguished American journalist Mark Sullivan wrote that “Our deprivation of rubber is as great a disaster … as Pearl Harbor.” Unlike the latter, however, he attributed the former to “our own unforgivable negligence, prolonged over many months.”Footnote 76

US vulnerability to rubber cutoff during the war was inescapable. Both before and after US entry, that vulnerability could have been addressed in ways that would have required different or more spending in advance but, ex post, would have been far less damaging to wartime productivity and national security. As in all considerations of insurance, such spending might, after the fact, have been deemed unnecessary, using the same questionable logic that might lead one to conclude that buying home insurance last year was a waste because in its absence one would today be richer (assuming the house remained undamaged). In the rubber case, additional and/or different ex ante expenditures would have been well justified by reasonable estimates of the risks they would have been intended to mitigate.

Figure 2. Frequency of references to “guayule” in American English-language texts, 1800–2023.

Note: The plot displays, by year, the frequency of n-grams (in this case a 1-gram) in a corpus of printed works in English, in other words, the fraction of 1-grams that match the identified text string. Search is case insensitive. The annual data have been smoothed (smoothing parameter = 2). The data for each year include that year’s count averaged with the count of the years two years before and two years after) (Google Books Ngram Viewer: https://books.google.com/ngrams).

Figure 3. Frequency of references to “butadiene” in English-language texts, 1900–2020.

Note: The plot displays, by year, the frequency of n-grams (in this case a 1-gram) in a corpus of printed works in English, in other words, the fraction of 1-grams that match the identified text string. Search is case insensitive. The annual data have not been smoothed (Google Books Ngram Viewer: https://books.google.com/ngrams).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680525101141.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for feedback from participants in the meeting of the all-University of California (UC) Group in Economic History at UC Davis on June 3, 2023; the World Cliometrics meetings in Dublin, Ireland, July 22, 2023; and the Economic History Association meetings in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, September 9, 2023, as well as from presentations at Santa Clara University, September 27, 2023; Chapman University, October 19, 2023; the ASSA meetings, San Antonio, Texas (January 5, 2024); the Business History Conference, Providence, Rhode Island (March 15, 2024); the World War II Discussion Forum (WWIIDF) on April 30, 2024; and the Robert Gordon Retirement Conference at Northwestern University (April 25, 2025). Thanks to Rowena Gray and Jonathan Rose for comments, to Hugh Rockoff for his detailed reading of the paper, and to David Foord for suggestions of additional sources.

Author biography

Alexander J. Field is the Michel and Mary Orradre Professor of Economics at Santa Clara University. He has authored two books on the economic development of the United States during the second quarter of the twentieth century: A Great Leap Forward: 1930s Depression and U.S. Economic Growth (2011) and The Economic Consequences of U.S. Mobilization for the Second World War (2022).