The 1800s in Panama were socially and politically effervescent. Independence from Spain in 1821, increased regional commerce, the construction of the transisthmian railroad, the start of work on the canal, armed conflict – life was hardly uneventful.Footnote 1 However, its cultural activity, and music in particular, has been largely overlooked in the historiography. In this essay, I discuss Panama’s musical landscape in the later nineteenth century through analysis of primary sources, focusing on the life and work of Panamanian violinist Miguel Iturrado (d. 1879). His musical activities are collected in several contemporary sources, yet all but ignored in traditional music historiography. Iturrado is one of several locally born musicians whose deeds and potential influence on the subsequent development of a musical landscape in Panama have gone unnoticed by key authors throughout the twentieth century. The isthmian country separated from Colombia in 1903, and the first authors to address the telling of its musical history favoured an account of the nineteenth century which focused on overseas-driven social transformations which paved the way toward sovereignty. The result strongly emphasizes the contributions of immigrants, this as part of a conscious effort to dissociate from its immediate Colombian ancestry and to build a ‘romantic’ past for Panama deeply rooted in fin-de-siècle traditions from the countryside.

I argue, based on primary sources and a critical analysis of Iturrado’s career as a leading dance musician, that Panama’s musical and cultural landscape in the nineteenth century differs considerably from those painted in traditional music histories. Sources include traveller’s chronicles, primarily those by Theodore Johnson (b. 1818), Édouard Auger (dates unknown) and Jenny White (1835–1867), as well as newspaper articles, reviews and advertisements from El Panameño and The Star and Herald,Footnote 2 ecclesiastical records from the city and not least importantly, the Díaz Family’s oral history as collected in 1915 by violinist and composer Narciso Garay Díaz (1876–1953). Analysis of these sources reveals an active and cosmopolitan musical landscape in nineteenth-century Panama that sharply contrasts with the customary histories woven by twentieth-century writers. I further argue that the violin-led culture spearheaded by Miguel Iturrado became the ground from which flourished both a prominent generation of Panamanian concert violinists and also the composers of the Azuero School,Footnote 3 authors of a prominent violin dance repertoire with long-standing consequences in Panama’s popular music.

Panamanian concert violinists born in the late 1800s – such as Alfredo De Saint Malo (1898–1984), Manuel Arias Hidalgo (1861–1926), Antonio Gáez (b. ca. 1890) and Narciso Garay, to name but a few– are indeed responsible for creating or leading active platforms for music performance as well as training institutions whose ramifications extend to this day and some even transcend Panamanian borders. Soon after, along Azuero’s eastern coast, Artemio De Jesús Córdoba (1895–1988), Francisco ‘Chico Purio’ Ramírez (1903–1988), Escolástico ‘Colaco’ Cortez (1904–1976) and Clímaco Batista (1907–1978) created a substantial repertoire of violin dance music which, I suggest, can be traced to the salon dance platform cultivated by Iturrado and his contemporaries. The Azuero School repertoire, composed largely in the first decades of the twentieth century, became the basis for most modern popular dance music in Panama.Footnote 4 This significant corpus of pieces, preserved through notation, recordings and oral tradition, is considered a strong part of a ‘Panamanian’ identity by its practitioners and by the folklorists who study it and keep it alive through various strategies of conservation. I conclude that these two relevant phenomena, significant themselves in the development of modern musical culture in Panama, are the consequences of a musical landscape shaped largely by the work of locally born violinist Miguel Iturrado and by the community that supported, cared for, and praised him in nineteenth-century Panama.

Searching for a Forgotten Panama

The story of Panamanian music – as it has been told for decades – begins late in the nineteenth century at the hands of immigrants.Footnote 5 The curtain usually rises with the arrival in the 1860s of French bandleader Jean Marie Victor Dubarry (1831–1873), who was appointed chief of the principal military band of Panama City and founded a training school for the musicians under his charge. Not long after that, in the 1890s, German consul and violinist Arthur Köhpcke (b. 1849) landed on the isthmus and taught notable Panamanian musicians such as Alfredo De Saint Malo and Narciso Garay. Cuban emigré Lino Boza (1840–1899) and his family were famed bandleaders, educators and arrangers who contributed to the building of local repertoire with several dance pieces and marches in their catalogues. Lino’s nephew Maximo Arrates Boza (1859–1936) was especially instrumental in the development of important musical institutions at the turn of the century, namely the Banda Republicana, thus stewarding Panamanian music-making into a new era at the dawn of the Republic. After the 1903 separation from Colombia,Footnote 6 Spanish-born organist Santos Jorge Amatriain (1870–1941), who had been chapel master of the Archdiocese since his arrival in 1889, became the author of the new country’s national anthem with recycled music from his 1893 Himno a Bolívar. The march was selected through public acclaim to accompany the new lyrics by Jerónimo De La Ossa (1847–1907), much to the delight of the local community, already familiar with the melodies.Footnote 7 Jorge’s contribution as author of the national anthem seems to neatly fit as closing seal for a narrative of foreign builders of fin-de-siècle Panamanian music history, offered by Charpentier and reiterated by Jaime Ingram and Erik Wolfschoon.Footnote 8

While the compositional output and performances of these musicians are essential to consider when approaching the construction of a Panamanian musical landscape at the turn of the century, the foundational narrative focused largely on foreign agency has tended to overlook the role of local musicians in the creation of an urban musical culture. This active musical platform predates the kick-off point of the traditional story by at least a century.Footnote 9 Popular music is not addressed or discussed in any of the accounts from twentieth-century authors, therefore erasing the rich history of cultural exchange and global awareness whose protagonists were local musicians. As primarily a performer, bandleader and composer of dance music, Miguel Iturrado and the highly influential musical platform built by him and his contemporaries largely fell through the cracks. Traditional music historiography – the little that has been produced – seems to suggest that close to nothing musical happened in Panama during the time when the isthmus was part of Colombia (1821–1903), during the Spanish colony (1513–1821), or even in the pre-Columbian era.Footnote 10 Conventional twentieth-century histories of Colombian Panama centred on the neglect and even disdain from Bogotá which, in the assessment of the authors who penned them, was reflected in a barren cultural and social landscape.

Juan B. Sosa (1870–1920) and Enrique J. Arce (1871–1947) wrote the book which perhaps contributed the greatest to this view in the collective imagination of Panamanians, including future scholars. Their 1911 Compendio de Historia de Panamá was adopted as the official source text for the instruction of Panamanian history in all schools of the new country.Footnote 11 In their ten chapters concerning Panama’s Colombian period, the authors focus on a genealogy of political authorities, secession attempts by various factions from across the social spectrum and larger key events such as the construction of the transisthmian railroad in the 1850s and the French canal attempt by Ferdinand De Lesseps. These events, due to the scope and purpose of the volume, are covered only through discrete political causes and consequences, without diving into social history and only tangentially discussing society and culture. Their work greatly influenced subsequent writings about the nation’s history, including the widely disseminated Libro Azul de Panamá and Panamá en 1915.Footnote 12 These were distinct efforts by the young government in order to portray Panama as a key player in the region, separate from Colombia, sovereign, with a culture of its own. The nation that is Panama after 1903, one could surmise from these readings, did not owe its modernity and progress to any cultural or social development during the Colombian period, but rather to the fact that Panamanians were able to secede from it and govern their own destiny away from social and administrative abandonment.

If Panama as a state within the Colombian republic was neglected through political isolation, frequent internecine conflict, shortage of resource allocation, preclusion of social mobility and little commerce, then it must follow that there was poor education, no production of art and consequently, no significant progress. This view, however, has cast a shadow on any actual political, social and cultural growth during the period in Panama, which has subsequently loomed over the popular imagination of local historians.Footnote 13 More recently, however, scholars have begun to explore several aspects of the Panamanian long nineteenth century from various disciplines, uncovering a period of profound social change, significant political advancement and cultural effervescence, indeed quite different from the traditional narrative.Footnote 14

Apart from Narciso Garay, who was himself born in 1876, writers of Panamanian histories had until recently made but passing references to locally born musicians of the nineteenth century or before.Footnote 15 We can find notable exceptions in the work of historian Alfredo Castillero Calvo, who alludes to several musical events such as parades, social dances, religious ceremonies and processions in the context of in-depth analyses of topics as diverse as wars, religious colonization, commemorations, the quest for independence, or the history of food in Panama.Footnote 16 Both Garay and Castillero Calvo, drawing from oral sources and from an 1849 travel chronicle by Theodore Johnson, respectively, mention a Panamanian-born violinist whose public career sprung in the late 1840s.Footnote 17 The musician performed music for dance, theatre, church and protocol and had achieved so much popularity on the isthmus by 1850 that he was affectionally nicknamed ‘Paganini’ by his fellow citizens after the Genovese virtuoso. Miguel Iturrado, born ‘from the people’ with an ‘irresistible calling for music’Footnote 18 – likely in the populous Panamanian suburb of Santa Ana –Footnote 19 was, according to Garay, taught to play the violin by his own great uncle, Ramón Díaz del Campo y Soparda (b. 1805) in the early 1840s.Footnote 20

No sources suggest that Iturrado was a virtuoso in the customary sense of the term. Panamanian audiences were no strangers to virtuosic performances –pianists Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829–1869) and Henri Herz (1803–1888), as well as violinists José White (1836–1918) and Ernesto Camillo Sivori (1817–1834) were among the most distinguished virtuosos to perform in town while touring between North and South America, or traveling between the East coast and California. Many Panamanians in the city were also surely familiar with Niccolò Paganini’s virtuosity, his career highlights and the legends surrounding his persona – newspapers from around the world were readily available in Panama during the nineteenth century, for a then largely bilingual audience.Footnote 21 The nickname ‘Paganini’ was more likely the result of a profound esteem conferred on Iturrado, and therefore not to be correlated with Niccolò Paganini’s style, technique, virtuosity or choice of repertoire. Iturrado was surely the best violinist his co-citizens knew, and the nickname they gave him should be read as a term of endearment within a culture where people are often known best by a witty soubriquet than by their given name, and not as association or comparison. Iturrado quickly became a staple in balls and public entertainment events as well as in the church, and soon made waves in newspaper articles, traveller chronicles and letters, leaving lasting repercussions on subsequent generations of Panamanian violinists.

A Lively Soundscape

Music historiography has been silent concerning the volume and variety of activity in Panama during most of the nineteenth century. It is important to state that there is no doubt that events in the latter half of the century such as Gold Rush travel, the ensuing construction of the transisthmian Railroad and the French canal initiative had profound consequences in the development of an artistic culture in fin-de-siècle Panama. However, historians and music researchers have frequently overlooked the lively musical landscape before 1850, one that is obliquely referenced by historian Alfredo Castillero Calvo.Footnote 22 Miguel Iturrado was born into this active, rich and diverse musical landscape. It is where he developed an interest for music and where then he worked throughout his life. In this section I show, through discussion of contemporary sources, that Panama City’s inhabitants did indeed produce a dynamic musical culture. A survey of chronicles, newspaper articles, advertisements and archival sources, allows us to reconstruct the very early stages of Miguel Iturrado’s public career. The violinist-bandleader skilfully navigated a diverse Panamanian musical environment, as he swiftly became one of its key figures and a point of reference for his contemporaries.

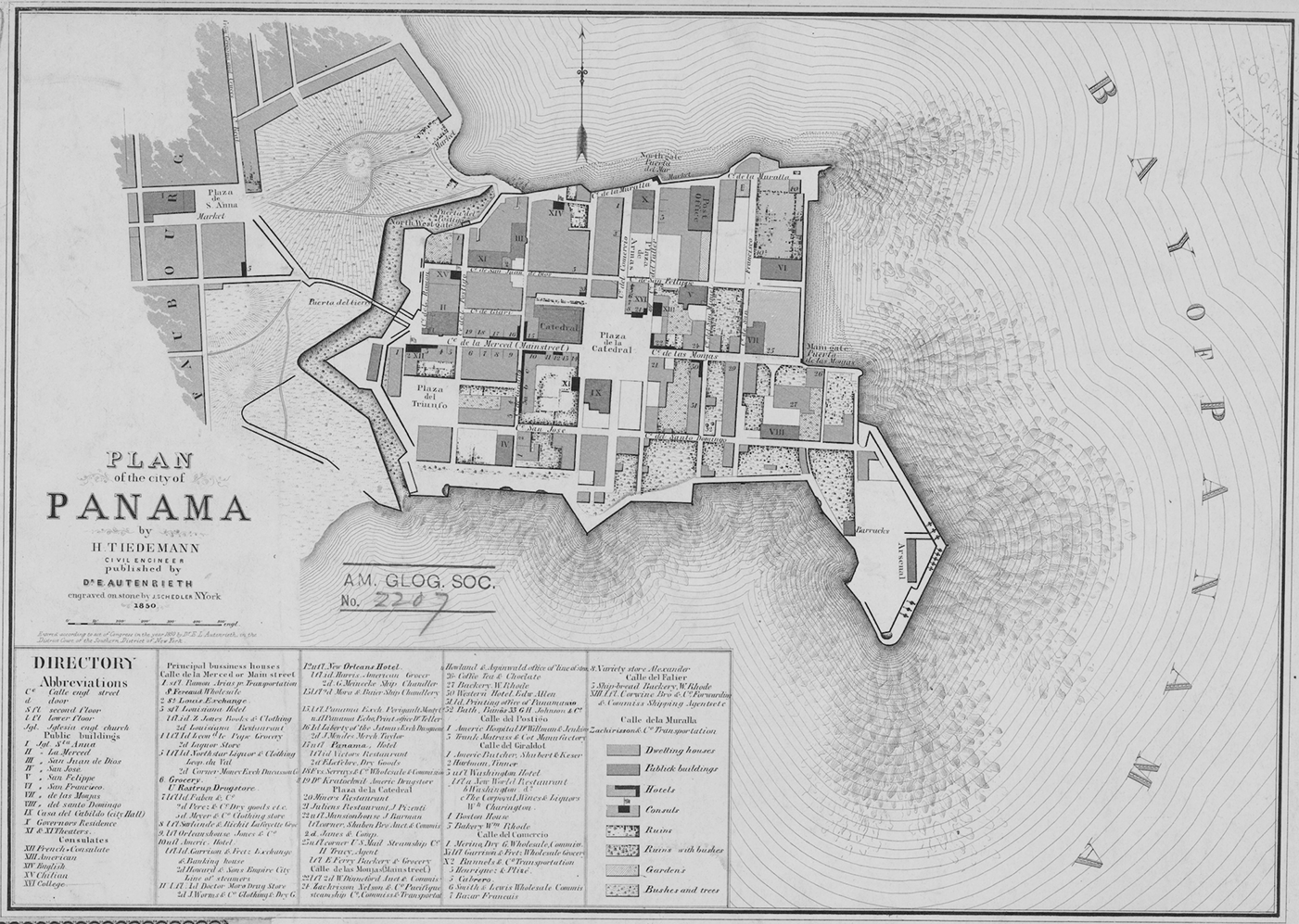

The first mention of Miguel Iturrado in print comes from a US investor who, like thousands of would-be prospectors and traders, was travelling to California at the outset of the Gold Rush of 1849.Footnote 23 Theodore Johnson is credited as being the author of the first published relation of the voyage from the eastern coast of the United States to California via Panama in the context of the Gold Rush. According to his account, Johnson arrives with his party in Panama City on the evening of 21 February 1849 after the arduous crossing of the isthmus by riverboat and mule. Early the next morning, he was awakened by cannon salvos and band music. Johnson soon learned that these were part of Washington’s Birthday festivities offered by the city in honour of the US community and diplomats.Footnote 24 The Governor of Panama provided the principal local military band for the morning parade, as well as the use of the East Battery, as reported by The Panama Star on its inaugural issue. Johnson, watching and listening from his room, was moved by ‘the inspiring strains of Hail Columbia from a full military band’ which led some ‘three or four hundred Americans’ through the narrow streets of Panama. Mr. Jansen, the owner of the American Hotel (Figure 1), offered a concert and dinner to culminate the festivities.Footnote 25 Johnson’s welcome in Panama was indeed filled with music.

Figure 1. Tiedemann 1850 Plan of Panama Walled City, showing San Felipe Quarter and a section of the suburb of Santa Ana Extramuros. American Geographical Society Library, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries, public domain.

Throughout his stay, Johnson would experience many more instances of music-making, including solemn organs at the Cathedral, a Protestant service at the US Consul’s residence, daily Catholic processions and several instances of military bands on parade. In the context of this active sound landscape, the music which captured Johnson’s attention the most came from a dance and variety band which played regularly at the American Hotel. ‘They performed opera music, overtures, polkas, waltzes, marches, &c., of the best modern composers, and all in the most perfect style’. Johnson then points to the leader of the ensemble, a man known as ‘Paganini’, claiming ‘he was, in truth, one of the best violinists we ever heard’. Miguel Iturrado’s band catered to their mostly US audience by opening and closing their evening’s performances with Hail Columbia and Yankee Doodle, known national airs ‘which were enthusiastically cheered with the regular American hurrah’. Johnson was so impressed with Iturrado and his band that he hired them ‘one lovely evening to serenade the Governor, our consul Mr. Nelson, and the American ladies in town’.Footnote 26

Johnson’s narration reveals an effervescent Panama where the soundscape is as vigorous as it is diverse. His depictions of daily band music in the streets, which is also attested to in contemporary newspapers,Footnote 27 together with the mention of the Governor’s military band, contrasts with the histories offered by Charpentier and Ingram, who seem to suggest that the first official band in the city is the one led by Jean Marie Victor Dubarry.Footnote 28 The Frenchman arrived in 1867, well after the Gold Rush-related events took place. As earlier records continue to surface, it becomes evident that band music was indeed present in the city even before the start of Panama’s Colombian period.Footnote 29 Military bands were an integral part of the Spanish royal armies’ and navy’s protocol, discipline and communication, in peace as well as in war.Footnote 30 Considering that Panama City was a busy transit route for goods, minerals and officers of the crown and clergy throughout the colonial period, military bands provided a quotidian soundscape that was normal and abundant. Band music became, as in many important cities during the long nineteenth century, a fixture in celebratory and protocolar events.Footnote 31 This suggests that the streets where Miguel Iturrado grew up were filled with band music to announce daily events such as the rounds for changing of guards at dawn and evening and also for special occasions, of which there were many: religious feast days, civil commemorations, proclamation of local and national decrees, arrivals of foreign dignitaries and diplomats and national holidays, to mention but a few.

Another important account of music in the transoceanic route during the Gold Rush period is offered by French adventurer Édouard Auger, who crossed the Isthmus in 1852 enroute to California. Auger arrived on the north coast of Panama and, like Johnson, began the crossing by boat up the Chagres River until he reached Cruces, where mules would take him, his companion and their baggage south to Panama City. While in Cruces, Auger witnessed a funeral cortège for a young boy, led through the streets by three musicians: a violinist, a fifer and a drummer. They played, Auger recalls, a ‘most happy’ local dance piece instead of a dirge. Once the procession reached the church, the music continued on during the entire ritual.Footnote 32 Auger’s observation suggests that already in 1852, the violin was part of the popular culture of the Panamanian hinterland. Fifes and drums would have been present in all municipalities in light of their long-standing use as military and civilian signalling and ceremonial devices.Footnote 33

Auger remained in Cruces for a few days before resuming his journey to the city by land. Upon arriving and discovering that he had lost his connection to San Francisco, Auger was forced to stay in Panama City until his shipping agent could arrange for a new vessel. During this time, Auger attended the daily Vespers at the Cathedral, where he heard the female choir singing ‘canticles on the melodies of sainetes and zamacuecas with violin accompaniment’.Footnote 34 The author also enjoyed a performance of ‘an English play by amateurs of the city’ led by a ‘director without a troupe’.Footnote 35 Auger is no doubt referring to Mateo Furnier y Compañía, a theatre company which was quite active during the time and whose performances featured live music and which often performed original works written by Furnier to commemorate special occasions.Footnote 36

Auger’s account from a few days in Panama City reveals that there was indeed much cultural activity across platforms and social groups. Quite relevant for our purposes, his observations tell the story of a Panama where the violin was a common fixture in the highest urban circles as well as in the rural hinterland. The lively violin music that Auger heard in different social and religious contexts, which to his sensibilities sounded like dances, can be quite revealing. I suggest that the violin – and the dance music associated with it – had been a part of Panamanian popular culture for long enough to have been incorporated into the conservative Catholic church by the early 1850s. While we cannot affirm that Miguel Iturrado was the protagonist in any of the events that Auger witnessed, it is not unreasonable to suppose that he was the sole violinist at the evening services of the Cathedral, since we do know that he was employed by the church.Footnote 37 Notwithstanding, Auger’s chronicle invites us to revisit mid-nineteenth century Panama as an active artistic centre, where lively dance-like music flowed between social circles and across platforms at the hands of violinists.

The year following Auger’s travel through the Isthmus, Miguel Iturrado led the band which accompanied the performance of the Ravel Family Circus. An advertisement which ran on page 2 of the Panama Star on 12 and 13 November, announced the international traveling company while featuring Iturrado’s participation: ‘An efficient band under the direction of the well-known Paganini will be in attendance to contribute to the evening’s entertainment’ (emphasis in the source).Footnote 38 Even though the advertisement seeks attendance to an event with international artists, it is clear that by this time Iturrado was esteemed enough in the city to be highlighted within the announcement of one of the best-known traveling circus companies from the period.Footnote 39

Among the most cited primary sources concerning social history in nineteenth-century Panama are the letters from New York socialite Jenny White and later compiled and published by her mother, Rhoda. White married prominent Panamanian businessman Bernardino Del Bal in New York in 1863 and shortly thereafter set out to his hometown of Santiago de Veraguas, 250 kilometers west of the capital city. While in Panama City, the Del Bals attended a number of social functions, including private parties and large public balls. An accomplished pianist and singer herself, White provided accounts of the music she heard throughout her time in Panama. One of the main events the couple attended was a ball offered by the Peruvian consul, which White described as similar to those she experienced in New York society, not only because of the splendour on display by the hosts and the notability of the guests, but also because of the music they danced to. The person in charge of conducting the ‘very good’ band for the evening was a musician, ‘who plays so remarkably on the violin that he is known only as Paganini – a name given him some years since in compliment of his proficiency as violinist. All musical artists who have passed through have complimented him highly’.Footnote 40

White reports that her host, Julián Sosa, informed her that Iturrado charged two dollars an hour, while the band would cost altogether seventy-five dollars for the entire affair. The ball was kicked-off with a pyrotechnic display at sundown, and continued through dawn. That means Iturrado would have taken home some twenty US dollars at the end of the evening, which is equivalent to the purchasing power of five hundred US dollars of today. This amount is half of what the top music official – the leader of the principal military band – earned in a month, according to contemporary documents cited by Eduardo Charpentier.Footnote 41 Beyond monetary compensation, Iturrado’s celebrity status is suggested through a curiosity mentioned by White: ‘Paganini had to be sent for and sent home in a carriage, for he was indisposed!’Footnote 42 In a two-district, rather small, city –about 10,000 inhabitants– with marked social distinctions, travel by carriage was indeed a luxury, and this is reflected in White’s surprised observation.Footnote 43 Not long after the Peruvian consul’s ball, an even larger affair was given in honour of Spanish vessels on a scientific mission which had recently made land on the isthmus, the first since the Independence of 1821. Once again, Iturrado was at the front of the orchestra leading from his violin, but this time the local band was expanded by the Spanish Admiral’s 36 musicians.Footnote 44

White passed away in Santiago from yellow fever a mere four years after the above events. During this time, she enthusiastically gave her time as a musician by singing, playing the piano, and coaching the musicians at the parish of Santiago Apóstol. While in Santiago, White described several occasions in which music was present, always showing deep admiration for the local’s talents. Music was a part of everyday life not only in Panama City, but also in the countryside, be it in yearly or periodic events such as carnivals or bullfights, or the more common serenades which were presented as a sign of respect. White even recalls a choral composition she wrote for the festivities of the Blessed Virgin Mary.Footnote 45 For her first Holy Week in Santiago, White attended the Good Friday service, for which she had been asked to sing the Stabat Mater. White complied after ‘hastily’ arranging a setting of the sequence accompanied by ‘an admirable violin player’.Footnote 46

The soundscape painted by Jenny White both in Panama City and in Santiago is one with not only vibrant musical activity across platforms, but one that is also diverse, globally connected, and produced by people who were certainly devoted to it. White even mentions that Panamanians were ‘passionately fond of music’,Footnote 47 a statement which articulates her descriptions of music-making in the capital as well as in the countryside. Her two encounters with Iturrado are a testament to the violinist’s celebrity as dance musician by this point in his career. Furthermore, I would suggest that the violinists she heard in Santiago, including the one who performed on Good Friday with her, are indicative of how widespread the instrument and violin instruction was by the 1860s throughout Panama. The violin had become, I propose, a platform for cultural exchange.

While several violinists were observed during religious ceremonies, the music is constantly described as dance music, or dance-like. The one professional violinist we know by name, Miguel Iturrado, is actually known to have performed both, seemingly to the delight of his listeners. I contend that violinists in nineteenth-century Panama such as Iturrado were using their versatility and their knowledge of current regional and global repertoire in order to transport musical traits –such as rhythms, melodic gestures, and performance styles across genres and musical stages. I suggest that this practice, and the popularity of musicians like Iturrado, produced a violin-led culture in Panama and its hinterland which eventually spawned generations of concert violinists, dance violinist-composers, and an entire tradition of popular dance music.

Iturrado’s Last Ten Years

The final decade of Miguel Iturrado’s life was quite active. Contemporaneous writings suggest that the esteem the citizens of Panama had conferred upon him only grew with the years. Above all, sources show Iturrado as the undisputed leader among dance musicians of the capital city, particularly in his final years. Study of these sources reveals the importance of dance music in many aspects of life, outside of the ballroom as well as inside. As we have seen above, even in religious events, the music is frequently described as dancelike. As an active dance music performer in the city, Iturrado would have likely incorporated elements from dance forms into music for worship. He would have likewise incorporated dance styles and the ‘music from the best modern composers’Footnote 48 into his own compositions of which, regrettably, none survive.Footnote 49 The fact that sources suggest that Iturrado was in great demand as a dance musician, but was also heard in a number of other musical contexts, is key to considering the connections between his musical activities and the diverse and rich violin culture which emerged in the fin de siècle.

Public balls were frequent, and Miguel Iturrado seems to have been present at most major important dances in Panama during the 1870s, whether they were official or private affairs. An example is his performance at the residence of J.H. Leverich in the city of Colon.Footnote 50 There are records of him performing for a special ball for the attendees of French violinist Monsieur Greffi’s recital at the Club de Panamá, a ball offered in honour of rear admiral Murray and the officers of the USS Pensacola, and a grand event in honour of businessman Manuel Lozada Plisé. In these reports Iturrado is dubbed ‘the inimitable’, ‘the renowned’, and ‘the celebrated Panamanian Paganini’.Footnote 51

A few months before his death, while suffering from the unknown illness that would ultimately end his life, Iturrado performed at two balls for the officers of the USS Lackawanna and the USS Adams, both of which were in Panama on diplomatic missions. The USS Adams ball was offered by the US Consulate, on land in March of 1879, and the Lackawanna ball was on board ship in February of that year. By this time, the Star and Herald staff writers reported that the music for the events had been in charge of ‘the now celebrated’, ‘our immortal Paganini’.Footnote 52 During Iturrado’s lifetime, there are no instances in the media of other dance musicians – or any other local musicians, for that matter – referred to in such terms. Accolades range from stating the fact that he is ‘well known’ to openly declaring him (metaphorically) immortal. No other musician appears nearly as often in the media, at least not by name.Footnote 53 It is important to reiterate here that his nickname does not refer to Niccolò Paganini’s virtuosity, style or repertoire, but rather is an affectionate deference to a local violinist whose ability seems to have far surpassed that of any of his contemporaries.

Iturrado continued his appearances outside of the ballroom as well. One such performance was quite eventful. In November 1869, the International Circus Company visited Panama for a number of performances. The Star and Herald reports an incident which occurred during the climactic moment of one of these evenings:

Miss Marie’s ‘Jump of Life’ nearly had the opposite effect. As the acrobat fell down, she grazed our Maestro Conductor Miguel Iturrado, throwing him toward the edge of the stage, causing light injuries to his face and wrecking his violin. Even so, the musicians in the orchestra played better than the night before.Footnote 54

Respect for Miguel Iturrado and his musical and leadership skills are evidenced here not only from the fact that his musicians were able to play satisfactorily even through a dangerous accident, but also because of the affection with which he is referred to: ‘our Maestro’. This, together with the records explored above, suggests that he was considered a symbol of the city, their very own ‘legendary’ musician.

Not all written sources are entirely flattering, a fact evidenced in an editorial review from Italian singer Luisa Riva de Visoni’s recital, where Iturrado was a guest artist, though we are not told of the capacity in which he performed:

Mr. Iturrado played his violin part regularly, taking into consideration the little time he had for rehearsals. Iturrado has a natural disposition and he needs only to study, to work diligently in order to be able to play compositions of merit. Why does he not?Footnote 55

While Garay declares that Iturrado learned to play the violin from Ramón Díaz Del Campo y Soparda, the above review seems to contradict this. It is possible nonetheless that he was started on the instrument by Díaz Del Campo, and then continued to learn on his own.Footnote 56 The review suggests that Iturrado could indeed read music, as he could perform with internationally acclaimed artists with but a few rehearsals. However, it is quite probable that his ability on the instrument favoured the music he performed the most, which consisted primarily of dance music. While it is not clear what the author of the review understands by ‘compositions of merit’, the context would suggest that they refer to concert music. Apart from accounts of operatic excerpts, sources do not indicate that Iturrado approached standard European violin repertoire or had any formal instruction therein. He focused, rather, on the music which was most on demand in his city’s daily soundscape.

Panama’s ‘Principal Musical Celebrity’

In June of 1879, a Monsieur Bonet, leader of the ‘Compañía Atletas de Ambos Mundos’, a local troupe of acrobats and variety artists, organized a special charity performance in order to raise funds to cover the costs of Miguel Iturrado’s illness. Half of the evening’s ticket would be given to Iturrado’s family. The ‘known Panamanian violinist, Miguel Iturrado (a) Paganini’ was enduring ‘a long illness’. Mr. Bonet assured the readers of the Star and Herald that the show would be ‘varied and entertaining’, and that he had no doubt that ‘the Panamanian public will come en masse to remedy the necessities of Mr. Iturrado’.Footnote 57

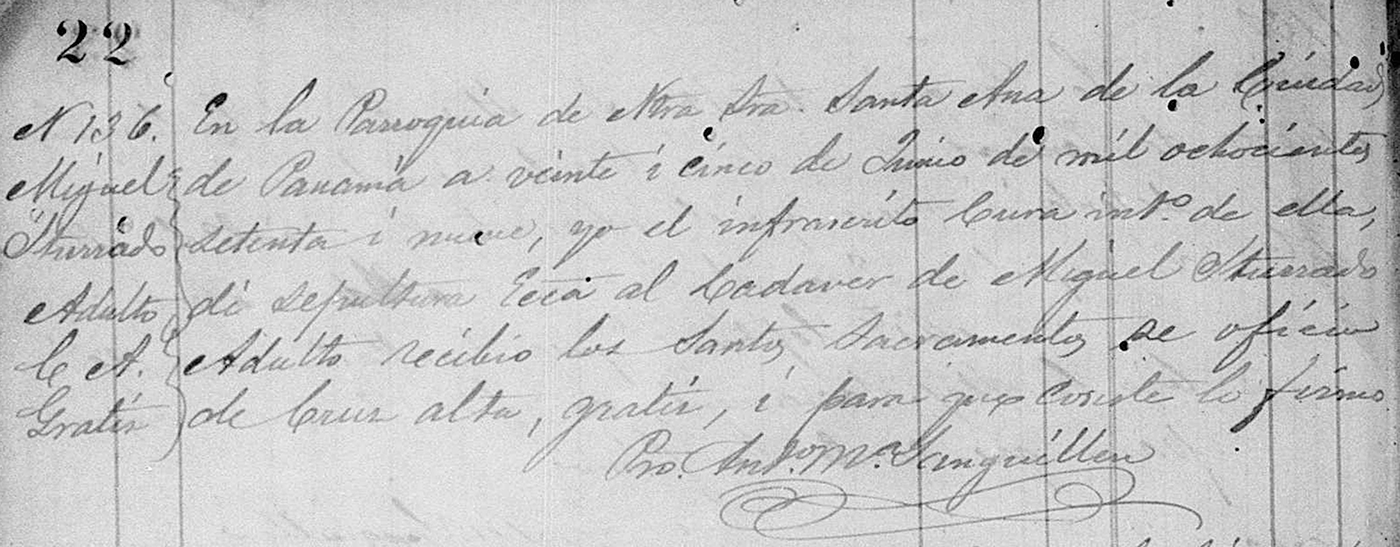

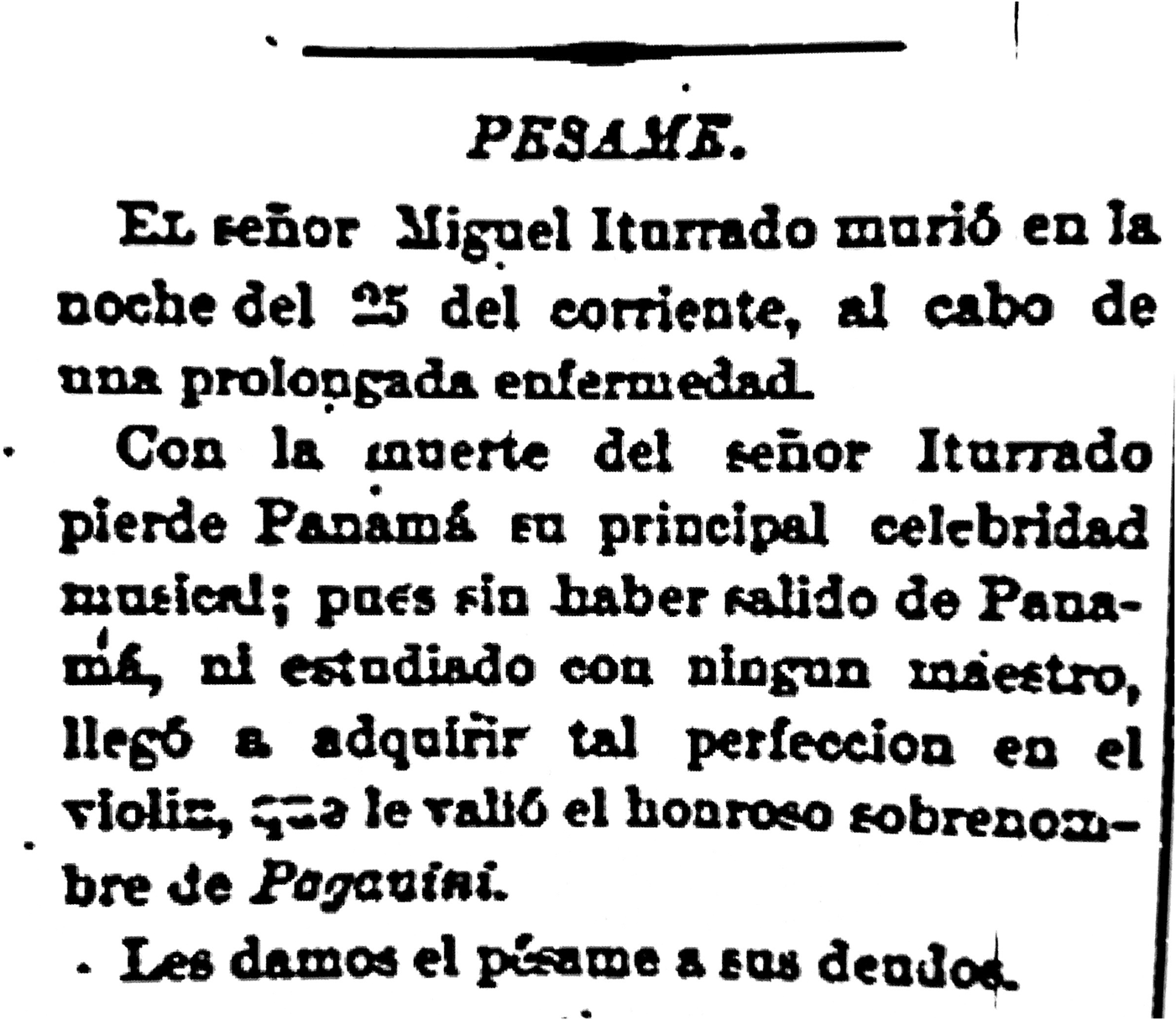

In spite of these efforts, Miguel Iturrado passed away in the suburb of Santa Ana outside the walls of Panama City, on the night of 25 June 1879. He received a High Cross funeral on the same night at no cost to his family (Figure 2) – an honour reserved for upper clergy and for those who could afford a sung high mass, double bell tolls, four priest accompaniment, coffin, incense, and full ecclesiastical vestments. His obituary was run by the Star and Herald on 26 June – in spite of the artist having passed after closing time – and again on July 3. The text is consistent with the esteem shown to Iturrado by both visitors and locals throughout his career, and a celebration of one who embodied the city’s pride and identity (Figure 3):

Mr. Miguel Iturrado passed away on the night of the 25th of the current month, after a prolonged illness. With the death of Mr. Iturrado, Panama loses its principal musical celebrity; since without ever leaving Panama, or having studied under any teacher, he came to acquire such perfection on the violin, which earned him the honourable nickname of Paganini. We offer our condolences to his loved ones (Translation mine, emphasis in source).Footnote 58

Figure 2. ‘In the parish of Our Lady of Santa Ana of Panama City, on the twenty-fifth day of June 1879, the undersigned officiated ecclesiastical burial ceremonies on the body of Miguel Iturrado … with free high cross’ (translation mine), Archive of the Church of Santa Ana Extramuros, burials, July 25, 1879.

Figure 3. Obituary for Miguel Iturrado published by the Daily Star and Herald on 26 June 1879.

Iturrado was survived by his wife, María Antonia, and a daughter, Angelina. The impact that Iturrado left on the musical life of Panama may not be easily quantified, but it is possible to extrapolate it through analysis of the surviving music that Panamanians made in subsequent decades and also through study of the musicians who flourished in following generations. I propose that the musical landscape in the early nineteenth century was significantly transformed by the work of Iturrado and his contemporaries, through the development of an active, globally informed, and musically skilled platform based largely on dance music. While the music performed by him and his musicians in many of the instances cited above is European in origin and quite current, creolization of these dances was a widespread phenomenon in the circum-Caribbean, one that Panama certainly embraced.Footnote 59

Although observers such as Johnson or White only mention Iturrado in connection with European-influenced music performances, the violin also functioned as a platform for cultural exchange in rural and suburban context, as suggested by Auger’s depiction of a rural funeral. It is quite reasonable to infer from the popularity and esteem ascribed to Miguel Iturrado that his violin could be heard in unreported private affairs – religious and secular – closer to his home in the suburb of Santa Ana and in the immediate hinterland of the city, where the music would have certainly responded to grassroots traditions. Based on the few ethnographic sources we have from the period, these would include a call-and-response spontaneous communal music called tamborito,Footnote 60 cumbias, pasillos, and creolized versions of European and Caribbean dances.Footnote 61

The written record suggests that Miguel Iturrado was a leader within a thriving artistic scene, which, in spite of constant social and political turbulence, continued to grow in activity and quality in order to meet the social demand of an expanding commercial and travel centre. Analysis of this corpus of extant written sources from the period reveals that Iturrado was indeed the protagonist in the construction of a violin-led musical culture in Panama later in the century and beyond – a culture that produced generations of violinists and composers who arguably became themselves the pillars of Panamanian music of the twentieth century, from concert circles to outdoor popular dance venues.

Land of Violinists

The violin continued to be ubiquitous in Panama’s musical circles after Iturrado’s death. Canadian physician Wolfred Nelson (1846–1913), for instance, recorded in the 1880s how spontaneous dancing accompanied by drums would be enhanced by a violinFootnote 62 in a scene which calls to mind Carlos Endara’s famous photograph of ca. 1890, titled ‘Fiesta popular en El Hatillo’ (Popular party at El Hatillo, Figure 4). Nelson also visited the island of Taboga, by then a popular day-trip destination for the citizens of the capital. ‘If a dance was in order’ during one such outing, ‘native musicians were secured on the island with violins and guitar’.Footnote 63 There were surely other musical forces flourishing in the city. Military bands performed weekly (and sometimes bi-weekly) outdoor evening concerts in the most frequented public spaces of Panama City.Footnote 64 This created a platform for composers to showcase their creations and also for audiences from across social strata to be acquainted with international orchestral repertoire, arranged for the band.Footnote 65 Although band concerts were becoming a popular way for Panamanians to enjoy a wide variety of music during the 1880s, the violin continued to be a fixture in dance venues and concert halls. I discuss in this section how the violin-led culture built by Iturrado and his contemporaries provided fertile soil for the following generations of violinists. They in turn, played significant roles in the development of concert and dance music scenes in Panama’s twentieth century.

Figure 4. ‘Fiesta Popular en el Hatillo’ (c. 1890), photography by Carlos Endara, public domain.

Two key indicators help to identify the burgeoning violin culture on the isthmus. The first of these is the increase of opportunities for formal violin instruction on offer in the city as well as in the country. This occurs in the final third of the nineteenth century as demand for players increases in all platforms. Both local and foreign instructors appear. This was true in rural areas as much as in urban centres. As to the former, Chitré native Cecilio Rodríguez (ca. 1854–1928) took advantage of seminary instruction in order to pursue his violin studies, first in Colombia, then in Europe.Footnote 66 North of Azuero, in Santiago de Veraguas, Dionisio Águila (b. ca. 1860) was a well-respected dance and church violinist at the turn of the century.Footnote 67 Both founded schools in their respective hometowns and were responsible for teaching generations of violinists. Manuel Arias Hidalgo, likely a pupil of Rodríguez as a child, was born in Parita, Azuero (approximately 13 kilometers from Chitré). Arias obtained a scholarship to study violin in Milan at an early age. He became a touring soloist across Europe and the Americas. His musical skills even as a 27-year-old ‘reveal[ed] uncommon gifts’ on the violin.Footnote 68 Arias Hidalgo settled in Santiago, Chile, where he continued to teach until his death.Footnote 69 Other instructors are reported by oral tradition, such as Juan Bautista Gomez (b. 1885),Footnote 70 whose life fell into obscurity but remains alive through legend. His students became the pioneers of the Azuero School, famed performers and composers of thousands of dance pieces during the first third of the twentieth century, now considered a traditional music canon.Footnote 71

In the capital city, the arrival of German violinist Arthur Köhpcke allowed for a new generation of young musicians who grew up listening to violins in ballrooms, religious services, and protocolar events to train formally on the instrument. His students included Narciso Garay and Alfredo De Saint Malo, largely considered founding figures of Panamanian concert music of the twentieth century. Garay, who continued studies at the Brussels and Paris Conservatoires, penned several pieces for violin and piano, including the first known violin sonata by a Panamanian. He returned in 1904 to found the first conservatory and symphonic orchestra in the now sovereign country of Panama.Footnote 72 From these platforms, Garay taught several young violinists who would themselves become multiplying agents: Saint Malo, Adriana Orillac (1887–1948),Footnote 73 Antonio Gáez, Demetrio Brid (b. 1890), Richard Neumann (1883–1957) and Köhpcke’s own son, Hans, to name but a few. Of these, Saint Malo would be the top pupil. Saint Malo toured extensively as soloist throughout the world and had a long-lasting musical partnership with French composer and pianist Maurice Ravel.Footnote 74 Spanish organist and composer Santos Jorge, who served as chapel master at the Cathedral, also had violin students since his arrival in 1889.

A second key indicator of the popularity of the violin may be found in print advertisements starting from the mid-1850s. As early as 1854, La Botica de Santa Ana (Santa Ana Apothecary) advertised violin strings and windings.Footnote 75 The same announcement ran for several years and was joined progressively by the competition. Haaz Hermanos, for example, offered violin strings as well as parts for the guitar in an ad placed adjacently to the Botica’s.Footnote 76 The advertisement of violin parts suggests that the instrument’s reach at least in the capital city and its hinterland was widespread enough by the time of the construction of the railroad to require a running supply from competing businesses. If there were indeed sufficient violinists for there to be parts on offer, then the generations born from this period onward, such as Cecilio Rodríguez, Manuel Arias Hidalgo, Narciso Garay, Saint Malo, and others, would have certainly grown up in a culture where the violin was heard frequently and whose main performers were well-respected and admired. The care and esteem conferred upon Miguel Iturrado is evidence of this admiration. Availability of parts, the propagation of formal instruction throughout the country, and the subsequent emergence of numerous proficient instrumentalists with international acclaim, show that Panama was becoming a land of violinists toward the fin-de-siècle, as a consequence of the cultural platform built by Miguel Iturrado and his contemporaries. A question arises at this point: does Panamanian music from the ensuing generation show any evidence of influence from this platform of cultural exchange?

The Azuero School

The twentieth century brought about dramatic changes for Panama. In 1903, the country parted from Colombia in the aftermath of the French Canal failure and the Thousand Days War, one of the largest civil conflagrations in Colombian history.Footnote 77 As Panamanians attempted to comprehend themselves as a sovereign people, a conscious attempt was made by the governing elite to create a ‘romantic’ Panama, one that was not connected with Colombia, but which rather emanated from ‘ancient’ traditions of Panamanian field and mountain dwellers. This entailed a necessary valuation of the cultural artefacts that rural Panamanians produced. Narciso Garay played a central role in this process through the publication of his Tradiciones y cantares de Panamá (1930), a book-length ethnographic study which includes several transcriptions of folk music and texts, many of which became models for artists from the cities and canon for succeeding rural artistans.Footnote 78

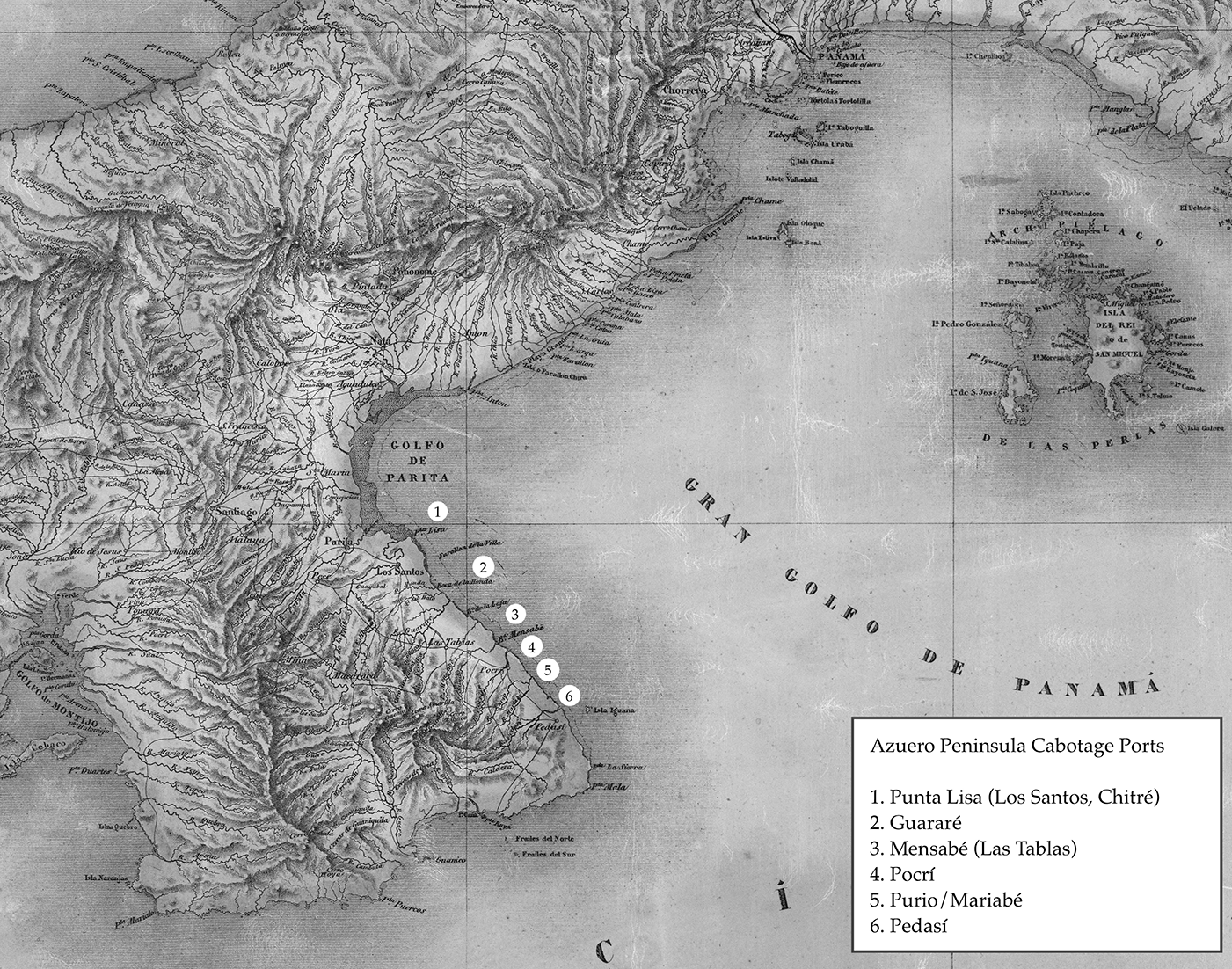

Of particular interest to our current purpose is the repertoire of pasillos and danzones composed in the Azuero peninsula on the pacific littoral during the first half of the twentieth century, which comprises thousands of pieces. Azuero was linked to the capital by maritime commerce through routes established centuries earlier and which are still used today (Figure 5). The violinists who composed these dances had been taught by some of the emerging instructors from the nineteenth century discussed above: Cecilio Rodríguez, Dionisio Águila, Juan Bautista Gómez, among others. Initially, the many danzones, cumbias and pasillos would be performed in open-air venues and private houses during feast days with a small ensemble comprising of one or two violins, guitar and maracas, and catering to local demand.Footnote 79 Artemio De Jesús Córdova, Francisco ‘Chico Purio’ Ramírez, Escolástico Cortez, Clímaco Batista and several others produced a large array of dance pieces unified by instrumentation, compositional style, purpose and performance practice. As the popularity of these composers and performers grew, so did their influence on the construction of Azuerense identity.

Figure 5. Carta Corográfica del Estado de Panamá (detail), Manuel Ponce De León, 1864, Corographic Commission. Cabotage ports in use throughout the 1800s along the Eastern coast of Azuero península have been indicated by the author. David Rumsey Map Collection, David Rumsey Map Center, Stanford University. Used with permission.

Example 1. Traditional cumbia from Azuero, transcribed by Narciso Garay (Tradiciones y Cantares de Panamá, 1930): 198. The melody is repeated for the duration of the dance.

The previous instrumental dance music considered as traditionally Azuerense, cumbias and dance mejoranas, was described and copied by Garay in Tradiciones. It was also performed on the violin, rabel, or on locally made fiddles and accompanied by guitar, mejorana, or bocona.Footnote 80 Dances were spontaneous and the music features simple melodies and harmonies, with only few exceptions parting from a tonic–dominant oscillation. Traditional cumbias relied heavily on short phrases that would be repeated several times with little or no variation (Example 1), while dance mejoranas rely on melodic formulas delivered over a stock two- or three-chord progression. Traditional violinists use a bowing technique derived from rabel playing, where at least one string is used as a drone. To facilitate this, bridges are carved flatter than on a classical violin and bows habitually gravitate toward the fingerboard. Bowstrokes are usually a combination of détaché porté and flautando, except for occasional legato for pairs of notes. Tremolo double stops for dance openings and endings are also customary. The instrument is held low on the shoulder – sometimes even resting on the chest – and the left wrist is turned to support the weight of the violin, the music consequently remains in the first position and makes little use of the fourth finger. There is also little if any vibrato in traditional violin performance. This type of cumbia is now only commonly performed in distant rural communities, while the dance mejorana is only preserved by a handful of troupes.Footnote 81

The repertoire of the Azuero School – which started with the music of Guararé’s Artemio de Jesús Córdova – differed from these previous cumbia traditions of the Peninsula in four key ways, which I argue were adopted in the region through increased contact with Caribbean and European dances via Panama City and performance styles and instruction in both music theory and classical violin technique. These, I suggest, are the result of the violin culture established in the nineteenth century by Iturrado and his contemporaries. First, dance music became actual compositions, set dances, the structured works of individuals who became themselves known as creators. ‘Old cumbias’, on the other hand, were anonymous and composed of repetitions of formulas as seen in Example 1. Second, composers allowed for an active dialogue to occur with other dance forms of the circum-Caribbean, in opposition to the elite’s agenda to consciously build a pure, ‘romantic nation’, based upon an imagined common link to the rural country. This reveals the desire of composers to connect with the world beyond political boundaries, which I propose is enabled by the global connections established through Miguel Iturrado’s musical platform during a critical time of change, social mobility and increased contact with travellers in Panama. Third, dance pieces were now notated, in response to – and perhaps also causing – the new, more complex structures. Notation made them easier to preserve and to spread. Finally, though no less relevant, the unified style traits and performance practice of the repertoire are clearly related to the salon dance tradition and repertoire of nineteenth-century Panama City, with social customs which were derived from formal dance protocol.Footnote 82

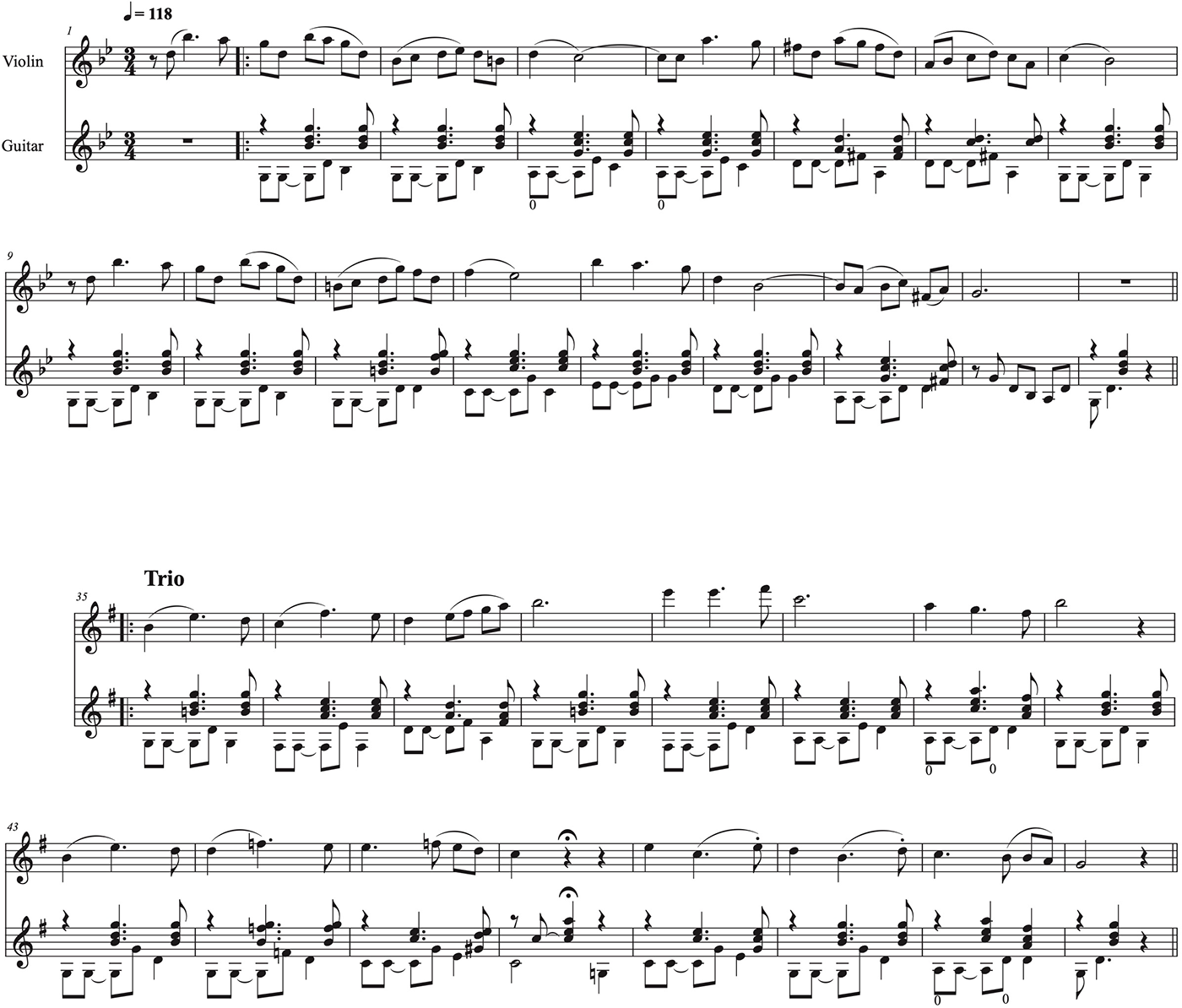

I offer Cordova’s pasillo Así soy yo Footnote 83 (Example 2) as an illustration of the above points. Azuero School composers usually notated melody and chords, much like a lead-sheet. While they and other violinists read music, guitarists usually did not, so they were free to develop accompanying figures based on their own previous experience and the requirements of the style at hand. I have incorporated a realization of the guitar accompaniment for this example, based on common pasillo practice, in order to show the reader the resulting structure and musical interaction in the style. Far from being an anonymous formula used for spontaneous dancing, Cordova’s music forms a planned structure usually responding to nineteenth-century set dances intended for planned social events. The sectional structure often features period phrases and is certainly intended as an authored composition. The pasillo, a creolized version of the waltz popular across the circum-Caribbean, is a prime example of the mapping of musical traits from European dance forms to new local ones.

Example 2. Así soy yo, pasillo by Artemio de Jesús Córdova. Reproduced with permission from the Córdova-Segistán family, guitar accompaniment realization by the author.

The sectional form, as is the case with set dances, helps dancers orient in the steps. The trio in the parallel major, a common feature in Azuero compositions, provides variety in intensity and in character. A similar transport of sectional structure, melodic design and harmonic complexity occurs in the development of other circum-Caribbean dances, such as the danzon, which in Azuero became the danzon cumbia.Footnote 84 Since Azuero School melodies are composed by classically trained violinists, they will usually involve third, fourth and fifth position shifting as in the trio of Así soy yo. Bowing is also quite more diverse, requiring several techniques and providing diversity of tone in order to perform richer phrasing. An Azuero-style violinist may play the four slurred quavers in bar 37 using legato bowing, but the same player might also use portato for variety in a repetition. In spite of leveraging the use of multiple bow strokes, Azuero-style violinists will also resort to styles typical of the ‘old cumbia’ practice, such as sul tasto bowing, détaché and double-stop drones. While the new melodic, rhythmic and harmonic complexity dictates that the music be written down for ease of transmission and teaching, players will certainly contribute stylistic elements from traditional cumbia playing as well as from their classical training in order to enrich their performances.

The use of these traits made the music interesting and memorable for dancers and listening audiences, for whom Caribbean and European set dances were very much still a part of their social life until the first decades of the twentieth century. Azuero School creators and performers became esteemed public figures and, quite often, local legends.Footnote 85 This, I suggest, cemented the cumbias, danzones and pasillos of the Azuero School first into local consciousness, then into national identity, as can be seen in rural celebrations of today and even in the music of modern popular artists.Footnote 86 We have seen how a solid dance music platform was developed throughout the nineteenth century with Miguel Iturrado at the forefront. The popularity of the violin resulted in the flourishing of formal instruction in urban and rural settings, several newly trained violinists soon followed. This, as evidenced by the appearance of violinists-composers such as Córdova, Ramírez, Batista, and Cortez, carried particular strength in the Azuero peninsula.

I propose that the vast repertoire by Azuero School composers in the first third of the twentieth century is a consequence of the active, culturally diverse, and globally connected musical landscape led by Iturrado since he first appears on stages in the mid-1800s. The global network of which Panama’s ports were important nodes, which influenced the repertoire Iturrado performed and was acknowledged by those who witnessed it, enabled the next generation of violinists-composers to incorporate elements from several musical traditions practiced in Europe and in the circum-Caribbean, linked first by commerce and tourism amd later by radio broadcasts.Footnote 87 Salon dance styles and their accompanying protocol flowed through maritime connections to the port towns of rural Azuero, where the music found fertile soil in the hands of young, resourceful, and aptly trained violinists. These artists saw an opportunity to create music to satisfy the new local demand for original salon-style dances. The new danzones, pasillos and cumbias, based on European dance harmonies of the waltz, polkas, mazurkas, and redowas performed in Panama by Iturrado and his contemporaries were now imbued with local performance practice and traits from circum-Caribbean dance forms which continuously arrived to Azuero by sea and then through airwaves. The effort soon developed into a massive corpus of dance music which, in a short time, became engrained into Azuerense and Panamanian consciousness.

Today, the violin is still considered a ‘truly Panamanian’ instrument. Musicologist Gonzalo Brenes featured it in his treatise on folk instruments, Los instrumentos de la etnomúsica de Panamá.Footnote 88 Several conservation strategies have flourished in order to preserve traditional violin dance repertories and their respective performance styles. Festivals celebrate the violin, competitions honouring Azuero School composers abound. The Panamanian music composed for the instrument in the generation after Iturrado’s death continues to be frequently performed and reinterpreted by popular dance groups and concert composers. Panamanians have, however, largely forgotten about Miguel Iturrado and some of his immediate successors, aside from isolated mentions as discussed here. They – Antonio Gáez, Juan Bautista Gómez, Cecilio Rodríguez, Dionisio Águila, and several others – can be credited with building the platform upon which much of the Panamanian music of today rests. Panamanian violin repertoire and performers become, then, quite a relevant avenue for future research, one which I am committed to pursuing and encouraging.

Acknowledgements

This research is made possible thanks to support from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the Sistema Nacional de Investigación (SENACYT, Panama). Many thanks to Tomás Mendizábal and Marixa Lasso for their feedback from the initial phase of my study. Deepest gratitude to both Readers during the review process of this article, who provided insightful and extensive feedback which certainly helped me arrive at this final version. A heartfelt thanks to guitarist Rodrigo Denis and violinists Graciela Núñez and Néstor Ibarra for their valuable technical input. I would especially like to thank Alfredo Castillero Calvo for his enthusiastic support of this project, for his illuminating comments on nineteenth-century life in Panama and for introducing me to Miguel Iturrado through his writings.