3.1 Introduction

When the late Professor Jean Rudduck and I began researching the notion of student voice in education in the early 1990s, a search for the keywords ‘pupil voice’ and ‘student voice’ would only have retrieved works on vocal cords and speech disorders. Now, thirty years later, a similar keyword search in the British Education Index or Google yields tens of thousands of references to research, practice and policy on initiatives that involve the participation of children and young people. This proliferation of interest in consulting young people and involving them directly in matters concerning their lives and their futures has been widely noted. However, the growth of the student voice movement has not been without challenge and controversy. Some feel it is going too far when children and young people are invited to comment or give their views on matters that are traditionally associated with adult domains, or when children campaign in ways perceived to undermine adult authority. We have also seen a reaction against the tokenism that can arise when children’s voices are used as mere decoration or to tick a box politically. If we are not listening to children and young people with a sincere regard and respect for their views, perspectives and capacities, then student voice efforts risk doing more harm than good.

Adults often applaud children and young people, like Greta Thunberg, Luisa Neubauer and Xiuhtezcatl Martinez, who speak on public platforms about profound and serious issues. However, the contributions of these individuals, although widely celebrated and highly influential, are rarely acted upon directly by policymakers. There is a problematic assumption that the action of voicing itself – being given the opportunity to express oneself – is what matters, whilst the need for adults to listen seriously and act is less significant. The voices of children and young people warrant recognition, but recognition should also (sometimes) give rise to action in terms of policy and practice. In this manifesto, I argue that the time has come to expand the notion of student voice to encompass another largely neglected idea – Aristotle’s notion of practical wisdom (phronēsis) – in order to achieve transformative change in education. I will return to this idea later, but first we need to understand why the principles of student voice and agency have not yet been implemented in full.

Student voice emerged as an idea in the late twentieth century and gradually took root, becoming a worldwide movement of change in education (Rudduck and McIntyre, Reference Rudduck and McIntyre2007). The movement has its origins in earlier studies in the 1970s which explored students’ perspectives on teaching and learning. And the idea of student voice was given impetus by Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (United Nations, 1989). Consulting students and giving them opportunities to take an active role in the decisions that affect their lives and education keyed in with the UNCRC’s aims. Still, the notion of student voice has been interpreted in different ways in different countries. Some, including the UK and Canada, have focused on student voice as a tool for school improvement initiatives, whilst others, such as Denmark and Sweden, have used it as a way to enhance democratic education. There have also been groundbreaking projects like the Design for Change programme, founded by Indian educator, Kiran bir Sethi, which seek to inspire children and young people to design and lead social change projects within their communities (Biddulph, Rolls and Flutter, Reference Biddulph, Rolls and Flutter2022). While many of these efforts have had a positive impact on children and young people’s opportunities for active participation, there is little evidence they led to sustained changes in policy. Concerns have also been raised that short-term initiatives sometimes fail to engage all students, leaving some marginalised and silenced, which can increase students’ sense of alienation, leading to cynicism and disaffection. Furthermore, in cases where students are consulted but their views not taken into consideration in the final decision-making, the result can be a loss of trust in democratic processes and adult authority. In addition, not all educators have welcomed the rise of student voice principles, and some teacher unions have objected to student involvement in school decision-making processes. In recent years, it has been argued that teacher agency has been undermined by prescriptive policymaking, and this has led to concern that student voices are being heard whilst teachers’ are being silenced. It seems fair to ask the question, How can educators nurture agency in young learners if they do not possess it themselves? As the Cambridge Primary Review warned, ‘Pupils will not learn to think for themselves if their teachers are expected merely to do as they are told’ (Alexander, Reference Alexander2010, p. 496).

The fallout of a pandemic, as well as ongoing global economic, social, political and environmental issues, have focused our minds: without a significant shift in our policies and practices, education will become anathema to the lives of our children and young people. Transformation is needed to reimagine an education which is dynamic and young person centred.

So, in a nutshell, our problem is that focusing on developing children and young people’s agency and voice has not led to transformative change in education. In fact, at times, our efforts have resulted in the opposite. Though we were not wrong to set out on this journey, we have reached something of a cul-de-sac. However, having come this far, I believe we should look to practical wisdom to help us uncover a more hopeful way forward.

In this manifesto I argue that by weaving voice, agency and practical wisdom together as threads of change, we can foster collaborative capacities for values-led action and decision-making in our schools and in the world at large. By equipping future generations with the capacity for practical wisdom, we can empower them to make better decisions, act as responsible stewards of the planet and become effective problem solvers capable of addressing complex social issues.

3.2 What Is Practical Wisdom, and Is It Needed?

Writing two and a half thousand years ago, in a time and society very different to our own, the philosopher Aristotle spoke of practical wisdom as being an ‘intellectual virtue’ – a way of being and a way of thinking – that enables a person to lead a flourishing life. Philosopher Stephen Kemmis (Reference Kemmis, Kinsella and Pitman2012, p. 156) offers this modern take on what practical wisdom is and entails:

[Practical wisdom] is a quality of mind and character and action – the quality that consists in being open to experience and being committed to acting with wisdom and prudence for the good. The person who has this virtue has become informed by experience and history and thus has a capacity to think critically about a given situation … and then to think practically about what should be done under the circumstances that pertain here and now, in the light of what has gone before, and in the knowledge that one must act.

Practical wisdom is about deciding what is right under the circumstances – deciding what is the best action to take in the here and now. It is a deliberative process that draws on knowledge, values and experience, and it provides an essential foundation for voice, agency and action. Practical wisdom involves balancing different types of knowledge, ethics, reasoning and skill to reach a judgement that informs action. Before we can express our voices and show agency, we must possess the courage of our convictions and know that what we say and what we are striving for are right. The Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues at the University of Birmingham in the UK has been looking at practical wisdom (phronēsis), and their team has sought to understand its development in adolescents. The Centre’s researchers describe phronēsis as a meta-virtue which plays ‘a fundamental role in bridging the “gap” between knowing the good and doing the good’ (Kristjánnson and Pollard, Reference Kristjánnson and Pollard2021, p. 6). Individuals acquire practical wisdom by interacting with others. And when it is enacted collectively through dialogue, it becomes informed, critical deliberation that characterises the intellectual freedom of which John Dewey (Reference Dewey and Bernstein1960, p. 287) spoke:

Social conditions interact with the preferences of an individual – in a way favorable to actualizing freedom only when they develop intelligence, not abstract knowledge and abstract thought, but power of vision and reflection. For these take effect in making preference, desire, and purpose more flexible, alert, and resolute. Freedom has too long been thought of as an intermediate power operating in a closed and ended world. In its reality, freedom is a resolute will operating in a world in some respects indeterminate, because open and moving toward a new future.

So, although the starting point for practical wisdom lies within the individual, its development and enactment are necessarily social, and integral to expressions of voice and agency. Interestingly, the Great Learning (Da Xue) (Chinaknowledge, 2022), one of the Chinese Confucian texts, written in roughly the same time period as Aristotle, expresses a similar interrelationship between personal and societal responsibility and envisions ‘great learning’ – a notion that embraces knowledge, virtuous character and ethical understanding – as being at the heart of civilised life.

The Great Learning

Despite profound technological and social change in the intervening centuries, these ancient philosophical ideas still resonate with the dilemmas of the twenty-first century. These dimensions of practical wisdom and the Great Learning – sincerity, ethics, reason, dialogue, knowledge, trust, reciprocity and respect – are vital to the successful functioning of civilised societies. And yet, unfortunately, we are still – across the world – a long way from their fullest actualisation. Put crudely, in what way are current educational practices preventing problem solvers from addressing social concerns (e.g. climate)? And what exactly will the inculcation of practical wisdom in subsequent generations do for their capacity to think around/through climate disaster? The question is, How can we cultivate practical wisdom through education for a more hopeful future?

3.3 Practical Wisdom: Creating New Educational Spaces

To create educational spaces that foster the development of practical wisdom, we must review and evaluate the conditions of learning. We can start by considering what is being taught and what aims underpin our curricular decision-making. If we aim to induct children and young people into societies that value justice, equity and sustainability, then a curriculum needs to avail students of different types of knowledge, capacities and reasoning. Moving beyond the commonplace and see-sawing ‘skills versus knowledge’ argument, an emphasis on practical wisdom requires us to offer curricula that seek to balance theoretical knowledge, practical skills, ethical understanding and experiential, intuitive and embodied ways of knowing. As the Cambridge Primary Review proposes, a curriculum needs to build a sense of empowerment, ‘to excite, promote and sustain children’s agency, empowering them through knowledge, understanding, skill and personal qualities to profit from their present and later learning, to discover and lead rewarding lives, and to manage life and find new meaning in a changing world’ (Alexander, Reference Alexander2010, p. 197).

As well as reimagining our educational aims and curricula, we should create educational spaces that foster collaborative learning and reflection. Schools must look for new ways to enable young people and teachers to express their voices and agency together in a spirit of collegiality, reflecting Maxine Greene’s (Reference Greene1995) call for school communities that question and seek out possibilities for social justice, equality and transformative change. Voice and agency flourish when students engage in dialogue with their peers, teachers and communities.

It is important to support students’ empowerment as leaders of transformative change who can draw on their capacities for practical wisdom to make well-informed, values-based judgements. Our educative efforts must be suffused with values, morality and character so that students and teachers can develop practical wisdom – becoming active members of learning communities in which relationships and dialogue are framed as collaborative, constructive and respectful. Far from being an abstract or cerebral ideal, practical wisdom is about taking action, and schools of the future must enable students and teachers to hone their capacities for practical wisdom, both within and beyond their gates. One example of this approach in action can be found in the Round Square international network of schools, described here by Round Square’s chairman, Rod Fraser (Round Square, 2018):

Created collaboratively with 160 schools involved and a writing team that spanned six continents, the RS Discovery Framework offers a structure for teaching and learning, both inside and beyond the curriculum, that connects the Spirit inherent in each of the Round Square IDEALS (International Understanding, Democracy, Environmental Stewardship, Adventure, Leadership and Service) with twelve Discoveries that students explore on their learning journey: inquisitiveness, tenacity, courage, compassion, inventiveness, ability to solve problems, self-awareness, sense of responsibility, appreciation for diversity, commitment to sustainability, communication and team-working skills. Within this Framework, Students and Faculty in RS Member Schools are encouraged to discover and develop their own capabilities through a range of experiences, activities, taught lessons, collaborative projects and challenges. One of the many factors that sets the RS Discovery Framework apart is that it is rooted in genuinely global, multi-curricula practical implementation. It describes, rather than dictates; is examples-led, not theoretical; and whilst it was conceived through a gradual meeting-of-minds between Round Square Heads of School over a number of years, it is inspired and empowered by student voice.

3.4 Practical Wisdom as a Foundation for Teacher Professionalism

I suggested earlier that teachers’ autonomy as professionals has been under pressure in recent decades as a result of educational policy that is increasingly managerial, marketized and prescriptive. In response to this threat to teacher professionalism, there has been growing interest in phronēsis – as a discourse and vision for practice that ‘resists a passive acquiescence to the discourses of professional life that are increasingly instrumentalist, technicist, and managerial’ (Kinsella and Pitman, Reference Kinsella and Pitman2012, p. 171). Elizabeth Kinsella and Alan Pitman explain:

The professional is not simply a technician; rather, the professional is charged with the tasks of making complex interpretive judgements and taking action, as spaces for learning and for professional development. … Phronēsis is a concept of interest, and of hope, for elaborating current conceptions of professional knowledge and for advancing an approach to practice in the professions that seeks to fill the void in current practices – an approach that is felt as a morally informed guiding force oriented toward a wiser path.

Fostering practical wisdom for the teaching profession means creating new structures for reflection and collaboration within teacher settings and communities, both nationally and globally, so that opportunities for building phronēsis are magnified by shared languages, expertise and visions. What might this look like in practice? Professional bodies, subject associations, initial teacher education institutions, teacher unions, educational networks and forums could become repositories that curate professional knowledge, drawn from accumulated practice experience, relevant theory and rigorous research. There are encouraging steps being taken in this direction already: for example the Chartered College of Teaching in the UK is curating teachers’ research through its journal, Impact, and its online platform. Similarly, the growth of teacher-led initiatives like ResearchEd suggest that teachers are concerned that their practices are ‘evidence-led’ and ‘research-informed’. However, phronēsis requires more than theoretical research evidence to arrive at wise decisions and actions: at its core are the professional values which must shape and determine practice. Figures 3.1 and 3.2 use a fictional scenario to contrast the constraints evident in current practice with the affordances created through a divergent framework of phronēsis-framed collegial professionalism. In Figure 3.1 we see the teacher struggling to enact their professional values amidst competing pressures. The teacher’s professional knowledge and values are unrecognised and overwritten. Figure 3.2 suggests that a phronēsis-framed collegial professionalism would allow practice and decision-making to be driven by teachers’ values, informed by an ongoing, collaborative process of critical reflection and collegiality. Such a conceptualisation of teacher professionalism would strengthen teachers’ agency and autonomy and help to create an expanding professional knowledge base for initial teacher education and professional development.

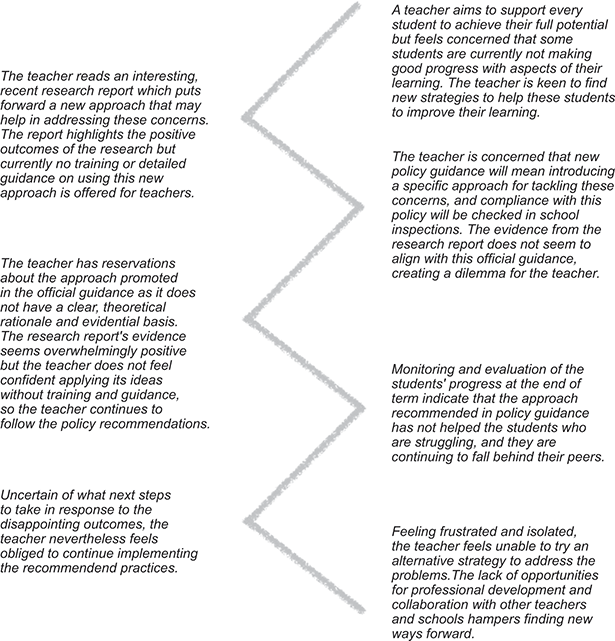

Figure 3.1 Influences on teacher’s praxis and decision-making without phronēsis.

Figure 3.1Long description

The zig-zag flowchart follows the sequence: 1. A teacher aims to support every student to achieve their full potential but feels concerned that some students are currently not making good progress with aspects of their learning. The teacher is keen to find new strategies to help these students to improve their learning. 2. The teacher reads an interesting, recent research report which puts forward a new approach that may help in addressing these concerns. The report highlights the positive outcomes of the research but currently no training or detailed guidance on using this new approach is offered for teachers. 3. The teacher is concerned that new policy guidance will mean introducing a specific approach for tackling these concerns, and compliance with this policy will be checked in school inspections. The evidence from the research report does not seem to align with this official guidance which creates a dilemma for the teacher. 4. The teacher has reservations about the approach promoted in the official guidance as it does not have a clear, theoretical rationale and evidential basis. The research report’s evidence seems overwhelmingly positive but the teacher does not feel confident in applying its ideas without training and guidance, so the teacher continues to follow the policy recommendations. 5. Monitoring and evaluation of the students’ progress at the end of term indicate that the approach recommended in policy guidance has not helped the students who are struggling, and they are continuing to fall behind their peers. 6. Uncertain of what next steps to take in response to the disappointing outcomes, the teacher nevertheless feels obliged to continue implementing the recommended practices. 7. Feeling frustrated and isolated, the teacher feels unable to try an alternative strategy to address the problems. The lack of opportunities for professional development and collaboration with other teachers and schools hampers finding new ways forward.

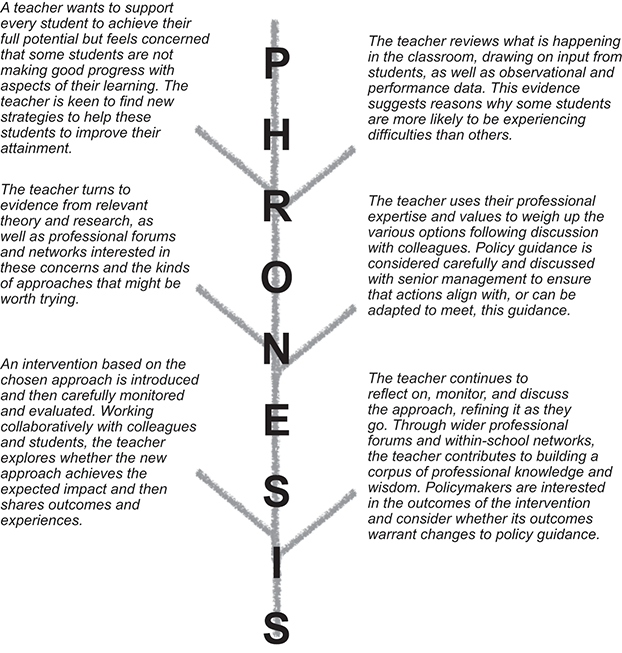

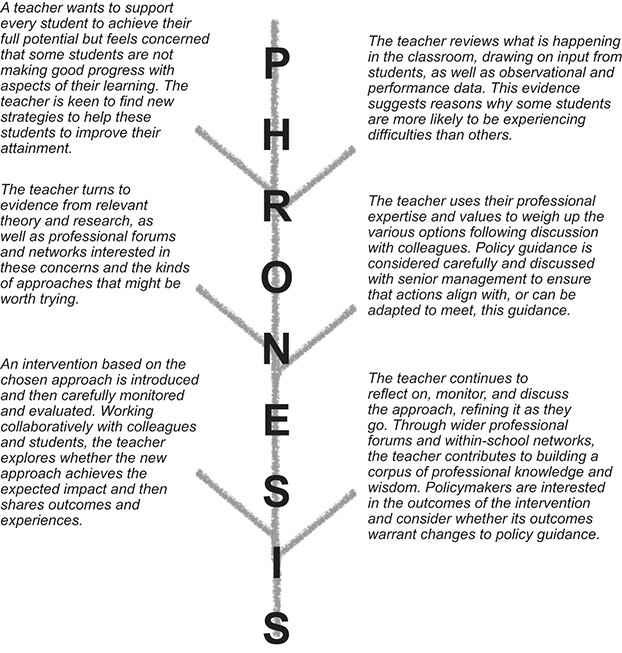

Figure 3.2 Teacher’s praxis and decision-making led by phronēsis.

Figure 3.2Long description

The flowchart with a vertical PHRONESIS label in the centre illustrates a teacher’s reflective process. 1. A teacher wants to support every student to achieve their full potential but feels concerned that some students are not making good progress with aspects of their learning. The teacher is keen to find new strategies to help these students to improve their attainment. 2. The teacher reviews what is happening in the classroom, drawing on input from students, as well as observational and performance data. This evidence suggests reasons why some students are more likely to be experiencing difficulties than others. 3. The teacher turns to evidence from relevant theory and research, as well as professional forums and networks interested in these concerns and the kinds of approaches that might be worth trying. 4. The teacher uses their professional expertise and values to weigh up the various options following discussion with colleagues. Policy guidance is considered carefully and discussed with senior management to ensure that actions align with, or can be adapted to meet, this guidance. 5. An intervention based on the chosen approach is introduced and then carefully monitored and evaluated. Working collaboratively with colleagues and the students, the teacher explores whether the new approach achieves the expected impact and then shares outcomes and experiences. 6. The teacher continues to reflect on, monitor, and discuss the approach, refining it as they go. Through wider professional forums and within-school networks, the teacher contributes to building a corpus of professional knowledge and wisdom. Policymakers are interested in the outcomes of the intervention and consider whether its outcomes warrant changes to policy guidance.

3.5 Weaving a Hopeful Future

‘We do not inherit the Earth from our ancestors, we borrow it from our children’ – this adage attributed to Chief Seattle (also rendered as Sealth or Seathl, Chief of the Duwamish and Suquamish peoples, Washington, USA) reminds us of our obligation to future generations who will inherit the planet. We want those future generations to make better decisions, to take greater care and act as wiser custodians of this planet than we have been. We cannot proffer solutions to the problems they might face in the future, but perhaps we can arm them with the capacities for practical wisdom that will enable them to be better decision-makers and collaborative problem solvers. As we grapple with worldwide challenges in this third decade of the twenty-first century, the words of American philosopher Richard Bernstein (Reference Bernstein1983, p. 229) strike a prescient chord, drawing our attention to the urgent need for practical wisdom, community and dialogue:

At a time when the threat of total annihilation no longer seems to be an abstract possibility but the most imminent and real potentiality, it becomes all the more imperative to try again and again to foster and nurture those forms of communal life in which dialogue, conversation, phronēsis, practical discourse and judgment are concretely embodied in our everyday practices.

Despite the prevailing sense of urgency and fear, there is hope on the horizon, and it can be heard in the voices of children and young people themselves. We must listen. For the past century, every year, a group of young people have come together to write the Peace and Goodwill Message, which is now translated into 100 different languages and sent out to the children of the world, under the auspices of Urdd Gobaith Cymru, the Welsh National Voluntary Youth Organisation. The Urdd’s (2022) message, marking its centenary, is titled ‘The Climate Emergency’. I offer this manifesto in the hope that it may inspire you and your students to explore new possibilities for nurturing practical wisdom; I leave its final words to the young people of Wales (Urdd Gobaith Cymru, 2022).

3.6 Discussion Points: Gathering Threads

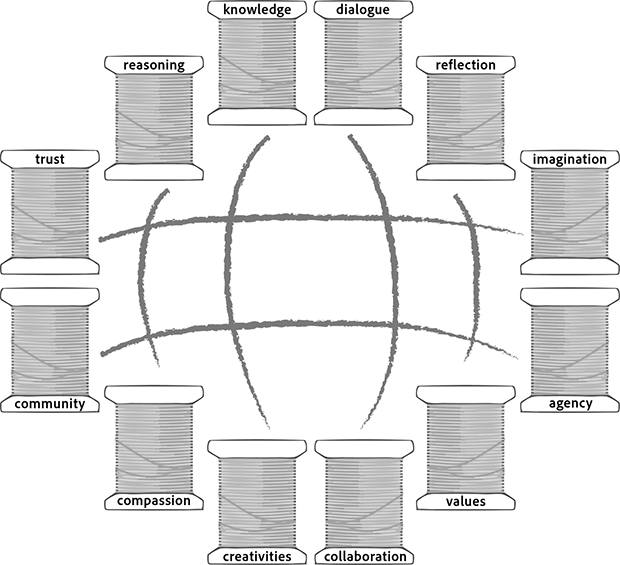

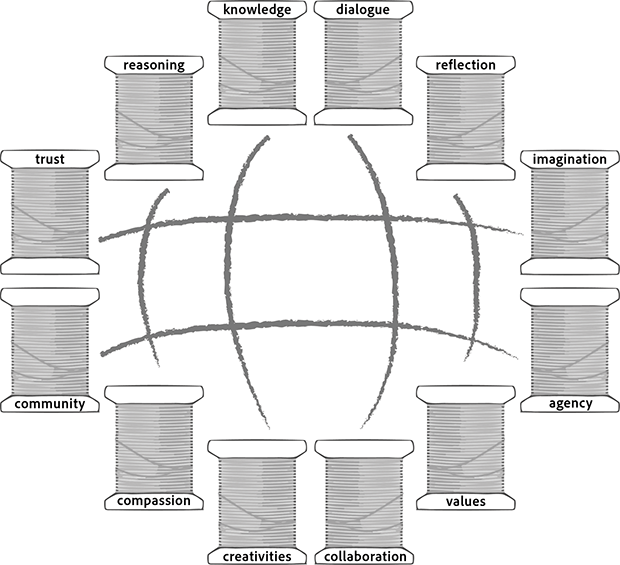

The threads shown in Figure 3.3 do not represent a bullet point list of recommendations or mottoes for a wall poster. There are no carefully worded guidelines, blueprints or sets of principles to prescribe or prioritise; rather, I would like you to think of these words as threads, to be taken in hand, discussed and woven together into the fabric of the future.

What do these threads mean? How do you, your colleagues and your students think about each of them? Are some threads particularly important in your setting or community?

How are these threads woven through your own practice and educational setting right now?

Are there ways to weave these threads differently to create new patterns of possibility for your students, colleagues and communities?

What other threads might you and your students, colleagues and communities want to weave in?

Figure 3.3 Threads for discussion.

Figure 3.3Long description

Twelve cartoon spools of threads, each labelled with a value, are arranged in a circle. Labelled from the top, clockwise, they are: dialogue, reflection, imagination, agency, values, collaboration, creativities, compassion, community, trust, reasoning, knowledge. In the middle of the circle there are crossing lines joining the spools in a network.