Introduction

Exposures before birth are increasingly recognised as significant factors that impact health outcomes throughout the lifespan. Reference Barker, Gelow, Thornburg, Osmond, Kajantie and Eriksson1–Reference Louey and Thornburg4 Specifically, a stressful environment in utero can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in offspring when they reach adulthood, a concept first introduced by Sir Prof David Barker in the late 20th century. Reference Barker and Osmond5,Reference Barker, Osmond, Golding, Kuh and Wadsworth6 He observed that both men and women with the lowest birth weights exhibited the highest standardised mortality ratios for ischaemic heart disease. Reference Barker and Osmond5 This understanding underpins the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) framework, suggesting that fetal growth and organ development before birth influence the development of diseases like CVD decades later. Reference Barker7,Reference McMillen and Robinson8

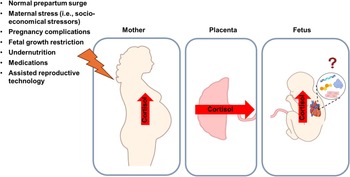

In normal pregnancies, a factor that influences overall fetal growth and cardiac maturation is the late gestation surge in cortisol, a key glucocorticoid (GC) hormone that prepares both mother and fetus for birth. Reference Mastorakos and Ilias9,Reference Mastorakos and Ilias10 There is some transfer of this GC from maternal to fetal circulation; however, it is tightly regulated by placental proteins such as P-glycoprotein and 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11βHSD2) acting as a barrier. Reference Mastorakos and Ilias10–Reference Zhu, Wang, Zuo and Sun13 Suppression of GC transport across the placenta is vital for maintaining a safe environment for fetal growth, ensuring normal physiological GC concentrations within the fetal circulation for the appropriate stage of development, and preventing the fetus from excess GC that could impede the trajectory of normal fetal growth and organ maturation. Reference Reynolds14

The mechanisms underlying the link between increased GC exposure in fetal life as a result of complicated pregnancy and poor cardiac outcomes remain unclear. A variety of factors during pregnancy can compromise the placental biology, resulting in fetal overexposure to cortisol. These include increased cortisol concentrations in maternal circulation due to psychosocial stress Reference Eberle, Fasig, Brueseke and Stichling15 and pregnancy complications like fetal growth restriction (FGR), preeclampsia, poor diet (maternal obesity or undernutrition) and gestational diabetes. Reference Zambrano and Nathanielsz16–Reference Aufdenblatten, Baumann and Raio18 This overexposure of GC at inappropriate times for the stage of organ maturation may underly some of the observed poor offspring outcomes, including insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia, both of which are major cardiometabolic syndrome risk factors. Reference Entringer, Kumsta, Hellhammer, Wadhwa and Wüst19–Reference Sacco, Cornish, Marlow, David and Giussani22 Moreover, while fetal overexposure to cortisol can arise from increased maternal cortisol concentrations and altered placental transfer, some pregnancy complications can prematurely activate the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is responsible for regulating the production of cortisol, leading to an earlier and higher rise in fetal plasma cortisol concentration. Reference Ng23–Reference Phillips, Simonetta, Owens, Robinson, Clarke and McMillen25 In the long-term, altered HPA axis function persists into adult life and contributes to the development of CVD and other cardiometabolic syndrome risk factors. Reference Seckl and Holmes26–Reference Balasubramanian, Varde, Abdallah, Najjar, MohanKumar and MohanKumar29

In addition to complicated pregnancies, the use of antenatal drug therapies during pregnancy may also lead to fetal GC overexposure. This includes antenatal GC therapy, commonly given to pregnant women at risk of preterm labour, to improve neonatal survival via direct activation of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and maturation of the fetal lung. 30–Reference Mwansa-Kambafwile, Cousens, Hansen and Lawn32 Although antenatal GCs have greatly improved the morbidity and mortality associated with preterm birth, off-target adverse effects have recently been highlighted. Reference Meakin, Gatford, Lien, Wiese, Simmons and Morrison33–Reference Rittenschober-Böhm, Rodger and Jobe37 Clinical concerns are growing with evidence that antenatal GC exposure increases the risk of mental and behavioural disorders in children, Reference Asztalos, Murphy and Matthews35 supporting preclinical findings that antenatal GC disrupts brain development. Reference Jobe and Goldenberg38–Reference Moss, Doherty, Nitsos, Sloboda, Harding and Newnham40 There is also a potential off-target impact of GC therapy on other organs, such as the fetal heart, but they are not well characterised. For example, existing studies report mixed cardiac outcomes across animal models of GC fetal overexposure. Reference de Vries, Bal and Homoet-van der Kraak41–Reference Reini, Dutta, Wood and Keller-Wood48 Assisted reproductive technology (ART) is commonly used prior to pregnancy, and this is associated with increased maternal cortisol concentrations and greater stress in late pregnancy. Reference Caparros-Gonzalez, Romero-Gonzalez, Quesada-Soto, Gonzalez-Perez, Marinas-Lirola and Peralta-Ramírez49 While some links have been made between offspring conceived through ART and indices of later-life cardiac dysfunction, Reference Dancause, Veru, Andersen, Laplante and King20,Reference Seckl and Holmes26,Reference Von Arx, Allemann and Sartori50–Reference Barnes, Sutcliffe and Kristoffersen52 little is known about how these outcomes relate to altered fetal cardiac development.

These findings underpin the hypothesis that GC play a double-edged role in heart development in that they support maturation but are potentially harmful when dysregulated. However, the mechanisms by which both physiological and pathological elevations in GC concentrations influence the programming of fetal cardiometabolic pathways and long-term cardiovascular outcomes remain unclear. Given the rising prevalence of stress-related disorders, pregnancy complications, and pregnancy interventions that can alter GC in fetal circulation or influence GR expression, this review aims to explore the effects of GC on fetal heart development and, thus, how they may underpin long-term programming of CVD. Examining these interactions may provide valuable insights to guide future clinical practice and public health strategies, ultimately helping to mitigate future cardiovascular risk.

Sheep as an animal model to study fetal heart development

In human pregnancies, it is difficult to study fetal physiology in a non-invasive manner; however, there are a range of animal models available to recapitulate aspects of human pregnancy. The development of the cardiac system in sheep is most similar to humans Reference Wang, Botting and Padhee2,Reference Botting, Wang and Padhee3,Reference Morrison, Berry and Botting53 in that the maturation of cardiomyocytes, which involves the transition from proliferation to terminal differentiation and glucose to predominantly fatty acid metabolism, occurs before birth. Reference Kim, Kim, Lee, Rah, Sawa and Schaper54–Reference Chattergoon, Giraud, Louey, Stork, Fowden and Thornburg58 However, due to their limited ability to generate new cardiomyocytes after birth, cardiomyocytes in humans and sheep are at higher risk of being programmed by the in utero environment with impacts that last throughout the life course. Reference Wang, Botting and Padhee2,Reference Louey and Thornburg4,Reference Wang, Botting, Zhang, McMillen, Brooks and Morrison59–Reference Morrison, Botting, Dyer, Williams, Thornburg and McMillen63 In contrast, cardiomyocytes of rodents maintain proliferative capacity and dependence on glucose metabolism in the immediate period after birth and do not reach relative maturity until neonatal day 7 – 10, Reference Li, Wang, Capasso and Gerdes64–Reference Lopaschuk and Jaswal66 providing a postnatal window for hyperplastic cardiac development after pregnancy. Reference Black, Siebel, Gezmish, Moritz and Wlodek67

In addition to similarities in cardiometabolic development between sheep and humans, sheep are particularly well suited for studying the impacts of GCs on the fetal heart. Cortisol is the predominant GC in both species, whereas corticosterone plays this role in mice and rats. Reference Dimasi, Darby and Morrison56,Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa68 The developmental timeline of the sheep fetal heart also closely parallels that of humans, with a comparable cortisol surge occurring primarily in late gestation, making the fetal heart highly responsive to GC manipulation during this critical window of development. Reference Morrison, Berry and Botting53,Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa68 Furthermore, maternal and fetal HPA axis regulation and placental 11βHSD2 activity in sheep resemble those in humans, shaping fetal GC exposure. Reference Morsi, DeFranco and Witchel24,Reference Fowden, Li and Forhead69,Reference Jensen, Gallaher, Breier and Harding70 Thus, sheep provide a translationally relevant model for investigating the impact of fetal GC exposure on cardiovascular development.

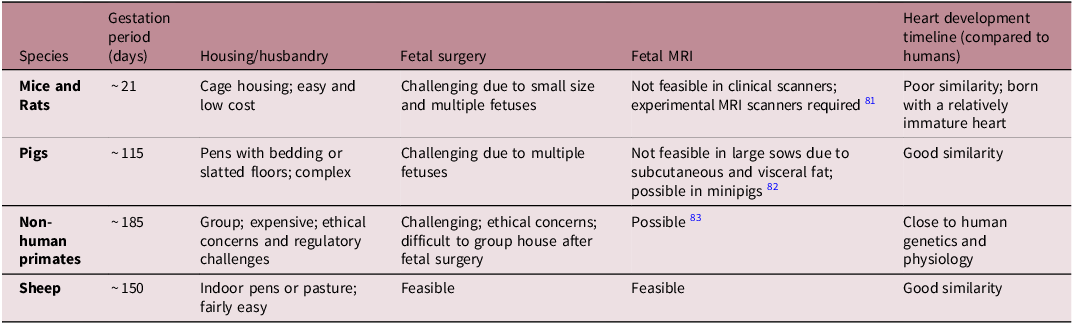

Mice and rats are widely used in medical research due to their short gestation (∼21 days), large litters, transgenic models and low cost (Table 1). However, their fetal heart development differs significantly from humans, and fetal surgery is challenging. Reference Morrison, Berry and Botting53,Reference Dimasi, Darby and Morrison56,Reference Lock, Tellam and Botting71 Pigs have a heart similar to humans Reference Dimasi, Darby and Holman72 and a medium gestation length (∼115 days), but fetal surgery is difficult due to multiple fetuses and the large size of the sow (Table 1). Non-human primates closely resemble human genetics and physiology, but ethical concerns, long gestation (∼180 days) and high maintenance costs can limit their use (Table 1). Reference Cox, Olivier, Spradling-Reeves, Karere, Comuzzie and VandeBerg73,Reference Huber, Jenkins, Li and Nathanielsz74 Favourably, sheep exhibit a similar pattern of cardiac growth and metabolism to humans, fetal surgery is more feasible than in rodents and pigs, and they are easier and less expensive to maintain than pigs and primates. Reference Morrison, Berry and Botting53,Reference Dimasi, Darby and Morrison56,Reference Lock, Tellam and Botting71 However, they have a longer gestation compared to rodents (∼150 days; Table 1). Moreover, advancements in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technologies allow the assessment of maternal and fetal cardiovascular function in sheep, Reference Duan, Lock and Perumal75–Reference Schrauben, Saini and Darby77 with placental and fetal oxygen consumption rates being similar in humans and sheep. Reference Saini, Darby and Portnoy78 Collectively, sheep serve as an excellent model for studying pregnancy complications and fetal heart development. However, sheep may be less suitable for studying congenital heart defects, as these conditions are relatively rare in sheep compared with murine models. Reference Wessels and Sedmera79 Given the genetic basis of structural heart development, murine models are more appropriate because they enable easier genetic manipulation, including knockout and overexpression approaches. Reference Yutzey and Robbins80

Table 1. Common animal models available for fetal heart development research. A range of animal models are available that can be used to recapitulate human pregnancy and investigate fetal heart development. Each model shares its own unique similarities and dissimilarities to humans, of which sheep offers the greatest advantages

Ontogeny of fetal cardiometabolic pathways

Cardiac proliferative and hypertrophic growth

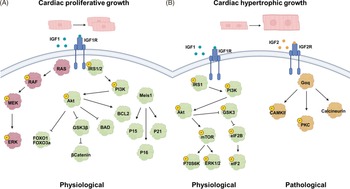

During fetal heart development, there are complex molecular changes that facilitate the transition from proliferative to hypertrophic cardiac growth. Cardiomyocytes make up the majority of cells in the heart, with mononucleated cardiomyocytes playing a key role in proliferative cardiac growth (increase in cell number) throughout much of fetal development. Reference Soonpaa and Field84,Reference Thornburg, Jonker and O’Tierney85 Later in gestation, these cells undergo binucleation, a process in which nuclear division (karyokinesis) occurs without subsequent cell division (cytokinesis), in sheep and rodents. Reference Jonker, Zhang, Louey, Giraud, Thornburg and Faber55,Reference Li, Wang, Capasso and Gerdes64,Reference Ahuja, Sdek and MacLellan86,Reference Burrell, Boyn, Kumarasamy, Hsieh, Head and Lumbers87 Binucleated cardiomyocytes have limited proliferative capacity and instead contribute to heart growth primarily through hypertrophy (increase in cell size). Reference Botting, Wang and Padhee3,Reference Oparil, Bishop and Clubb88 At the molecular level, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), one of the most abundant growth hormones in fetal circulation, binds to the IGF1 receptor (IGF1R) at the cardiomyocyte cellular membrane, initiating a downstream signalling cascade via the ERK/MAPK and/or P13K/Akt pathway, leading to cardiac proliferative growth (Fig. 1A). Reference Wang, Botting, Zhang, McMillen, Brooks and Morrison59,Reference Chattergoon, Louey, Jonker and Thornburg89–Reference Díaz del Moral, Benaouicha, Muñoz-Chápuli and Carmona92 Moreover, the IGF1R has a high binding affinity for IGF1 and IGF2, but it also binds insulin, albeit with lower affinity. Reference LeRoith, Holly and Forbes93 Importantly, we have recently shown that both an early Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa94 and natural rise Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa68 in cortisol as well as antenatal betamethasone Reference Amanollahi, Meakin and Holman95 can each reduce the expression of IGF1R in the developing heart. This effect may be mediated through altered expression of GR isoforms in the heart. Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa68,Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa94,Reference Amanollahi, Meakin and Holman95

Figure 1. Signalling pathways involved in cardiac proliferative (A) and hypertrophic (B) growth. A) binding of IGF1 to its receptor IGF1R activates downstream signalling through the RAS/RAF and PI3K/Akt pathways. These cascades promote cellular growth, survival, and protein synthesis via the activation of key effectors, facilitating physiological cardiac proliferative growth. B) IGF1 activates IGF1R, triggering the PI3K/Akt pathway to promote physiological cardiac hypertrophic growth. In contrast, IGF2 binds to IGF2R and activates Gαq-mediated signalling, leading to pathological cardiac hypertrophic. IGF; insulin-like growth factor. IGF1R; insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. RAS; rat sarcoma. RAF; rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma. PI3K; phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase. Akt; protein kinase B. CaMKII; calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. PKC; protein kinase C. Meis1; myeloid ecotropic viral integration site 1. ERK; extracellular signal-regulated kinase. MEK; Mitogen-activated protein kinase. FOXO; forkhead box O. IRS; insulin receptor substrate. Figure made in Biorender.

Notably, Meis1 plays an important role in cardiac growth by activation of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors such as p15, p16, and p21 to induce cardiomyocyte cell cycle exit at birth (Fig. 1A). Reference Lock, Tellam and Botting71,Reference Mahmoud, Kocabas and Muralidhar96 In the later stages of cardiac development, the same IGF1R pathway can also induce enlargement of cardiomyocytes, leading to physiological cardiac hypertrophic growth (Fig. 1B). Reference Burrell, Boyn, Kumarasamy, Hsieh, Head and Lumbers97–Reference Bernardo, Weeks, Pretorius and McMullen100 The role of IGF2 is less defined than IGF1; however, it is known that under conditions of stress, IGF2 has a higher affinity for IGF2R, initiating a downstream signalling cascade leading to pathological cardiac hypertrophic growth (Fig. 1B). Reference Wang, Botting and Padhee2,Reference Wang, Botting, Zhang, McMillen, Brooks and Morrison59–Reference Morrison, Botting, Dyer, Williams, Thornburg and McMillen63,Reference Bernardo, Weeks, Pretorius and McMullen100

Cardiac metabolism and contractility

The heart must produce sufficient energy to support cellular processes related to cardiac growth. In fetal life, glucose is the primary fuel source and is transported into the cardiomyocyte via glucose transporters (GLUT). Reference Shao and Tian101 The two dominant cardiac glucose transporters are GLUT1, which allows for glucose entry independent of insulin, and GLUT4, which is mediated by insulin through the IRS1/Akt/AS160 signalling pathway Reference Shao and Tian101–Reference Hocquette, Sauerwein, Higashiyama, Picard and Abe103 (Fig. 2A). Upon entering the cell cytoplasm, glucose is metabolised to pyruvate, whereby its byproducts enter the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and feed into the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC), undergoing oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to produce ATP for cellular energy (Fig. 2A). OXPHOS is a critical process that occurs in the inner mitochondrial membrane, producing ATP through five complexes where I – IV create a proton gradient and V produces ATP. Reference Dimasi, Darby and Morrison56,Reference Lopaschuk and Jaswal66 In late gestation, human and sheep fetal hearts begin to utilise metabolism of fats that can generate higher amounts of energy compared to glucose by upregulating metabolic machinery. Reference Chattergoon, Louey, Jonker and Thornburg89,Reference Drake, Louey and Thornburg104 Fatty acids are taken up via cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) and fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs), converted to fatty acyl-CoA, and transported into the mitochondria by carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), whereby they undergo fatty-acid β oxidation and byproducts enter the OXPHOS pathway (Fig. 2A). Reference Dimasi, Darby and Morrison56,Reference Shao and Tian101 PDK4 mediates the metabolic switch of substrate utilisation from glucose to fatty acids. Reference Rowles, Scherer and Xi105,Reference Sugden and Holness106

Figure 2. Key proteins involved in cardiac metabolism (A) and contractility (B). A) insulin signalling through IRS1 activates akt and AS160, facilitating GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake alongside insulin-independent GLUT1. Glucose is metabolised through glycolysis to produce pyruvate, which is converted to acetyl-CoA within the mitochondria. Fatty acids are taken up via CD36 and FATP, converted to fatty acyl-CoA, and transported into mitochondria by CPT1. Finally, acetyl-CoA enters the TCA cycle, leading to ATP production through OXPHOS. B) calcium enters the cardiomyocyte via LTCC, initiating excitation–contraction coupling. During contraction, calcium is released from the SR via ryR and binds to myofibrils. PKA also phosphorylates troponin I and C, modulating myofibril sensitivity and enhancing contractility. PKA and caMKII phosphorylate PLN, relieving its inhibition of the SERCA pump and promoting calcium reuptake by SR for relaxation. IRS; insulin receptor substrate. Akt; protein kinase B. AS160; akt substrate of 160 kDa. GLUT; glucose transporter. CD36; cluster of differentiation 36. FATP; fatty acid transport protein. CPT1; carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1. TCA; tricarboxylic acid cycle. LTCC; L-type calcium channel. PKA; protein kinase A. CaMKII; calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. PLN; phospholamban. SERCA2; sarco/endoplasmic reticulum-type calcium transport ATPase 2. SR; sarcoplasmic reticulum. RyR; Ryanodine receptor. Figure made in Biorender.

These changes in metabolic machinery are necessary to allow for more efficient metabolism of fatty acids to produce enough ATP to support the fetal heart in preparation for greater contractile demand after birth. Reference Drake, Louey and Thornburg104 Thus, both the metabolic and contractile apparatus undergo maturational shifts concurrently in late gestation. Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa68,Reference Dimasi, Darby and Holman72,Reference Bertossa, Darby and Holman107,Reference Posterino, Dunn, Botting, Wang, Gentili and Morrison108 Contraction of the heart is controlled through excitation – contraction (EC) coupling involving a number of key calcium (Ca2+)-handling proteins. After the cardiomyocytes are structurally mature enough, with an adequate sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), a change in membrane potential (the action potential) moves along the t-tubules, activating the voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC), allowing a small amount of extracellular Ca2+ to enter the cardiomyocyte Reference Manfra, Louey and Jonker109 (Fig. 2B). This rise in intracellular Ca2+ initiates further calcium release via the ryanodine receptor (RyR), allowing Ca2+ release from the large store within the SR that subsequently binds to troponin, triggering contraction of the myofibril (Fig. 2B). Upon relaxation of the cardiomyocytes, the majority of Ca2+ is either, under the regulation of phospholamban (PLN), returned back into the SR via Sacro/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2) and sequestered by calsequestrin (CSQ), or is removed from the cardiomyocyte by the sodium calcium exchanger (NCX; Fig. 2B). Reference Nusier, Anureet and Dhalla110,Reference Park and Kho111

Current understanding of how GCs affect fetal contractility and cardiometabolic signalling pathways is limited, but emerging evidence suggests that early or excess exposure can dysregulate these processes. In the fetal sheep, cortisol infusion increased protein abundance of mitochondrial OXPHOS complex I without altering mitochondrial content, Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa94 raising concerns about programmed mitochondrial dysfunction, since complex I is a major site of reactive oxygen species generation. Reference Johnson, Choksi and Widger112,Reference Kudin, Bimpong-Buta, Vielhaber, Elger and Kunz113 Under normal conditions, GR isoforms appear to correlate with OXPHOS expression, but this relationship is disrupted by cortisol exposure in the fetal heart. Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa94 Cortisol exposure earlier in pregnancy has also been shown to promote glucose handling by upregulating GLUT4 and phosphorylated IRS1, consistent with enhanced insulin signalling and early maturation of cardiac glucose uptake. Reference Fowden, Szemere, Hughes, Gilmour and Forhead114,Reference Jellyman, Martin-Gronert and Cripps115 By contrast, exposure to synthetic GCs (betamethasone or dexamethasone) has been linked to downregulation of CD36, disruption of fatty acid metabolic gene expression, and reduced GR expression, suggesting a delayed or altered transition from glucose to fatty acid utilization. Reference Amanollahi, Meakin and Holman95,Reference Ivy, Carter and Zhao43 Interestingly, our recent study found that in betamethasone-exposed hearts, the GRβ:GRα-A ratio positively correlated with GLUT4 expression, suggesting a shift toward greater GC resistance and sustained reliance on glucose metabolism. Reference Amanollahi, Meakin and Holman95 However, GC treatment of primary mouse fetal cardiomyocytes in vitro has been shown to promote ultrastructural maturation, enhance contractile function, and increase the expression of cardiomyocyte maturation markers. Reference Rog-Zielinska, Craig and Manning116 Similarly, dexamethasone treatment of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes increases contractile force and accelerates systolic calcium transient decay. Reference Kosmidis, Bellin and Ribeiro117 Together, these findings highlight that while GCs can drive aspects of cardiometabolic maturation, early or excessive exposure may impact substrate utilisation and mitochondrial function in ways that compromise normal cardiac development.

The role of cortisol, GC receptors and thyroid hormones in fetal heart maturation

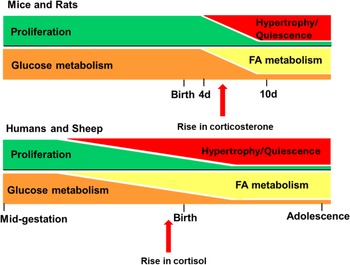

Cortisol is the dominant GC in most mammals, including humans and sheep, whereas corticosterone is dominant in rats and mice. The timing of cardiomyocyte maturation varies between species and is closely linked to the timing of the surge in circulating GC, which occurs before birth in humans and sheep but after birth in rats and mice (Fig. 3). Reference Dimasi, Darby and Morrison56,Reference Fowden, Li and Forhead69,Reference Nathanielsz, Huber, Li, Clarke, Kuo and Zambrano118 Cortisol is produced following activation of the HPA axis, a neuroendocrine cascade that begins with the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus that stimulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) release from the anterior pituitary, which activates receptors in the adrenal cortex, ultimately leading to cortisol release into the circulation. Reference Almanza-Sepulveda, Fleming and Jonas119

Figure 3. Differences in the timing of cardiomyocyte maturity and the concurrent prepartum GC surge between animal models of human pregnancy. In mice and rats, the rise in plasma GC (corticosterone) occurs after birth, compared to large animals such as humans and sheep, in which the GC (cortisol) rise occurs in late gestation. The rise in GC coincides with the transition in cardiac growth (from proliferation to hypertrophy) and metabolism (from glucose to fatty acid; FA). d, days. Figured adapted from Reference Lock, Tellam and Botting71 .

Within the circulation, cortisol can stimulate the deiodination of the thyroid hormone thyroxine (T 4) to the active form tri-iodothyronine (T 3), which is produced and secreted under the regulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis. Reference Chattergoon, Giraud, Louey, Stork, Fowden and Thornburg58,Reference Chattergoon91,Reference Tampakakis and Mahmoud120 The fetal plasma surge in cortisol and circulating T3 concentrations during late gestation (∼132–145 days of gestation, term = 150; sheep) coincides with terminal differentiation of cardiomyocytes and the upregulation of the machinery required for fatty acid metabolism rather than glucose to fuel the heart before birth in sheep (Fig. 3). Reference Phillips, Simonetta, Owens, Robinson, Clarke and McMillen25,Reference Dimasi, Darby and Morrison56,Reference Chattergoon, Giraud, Louey, Stork, Fowden and Thornburg58,Reference Dimasi, Darby and Holman72,Reference Chattergoon, Louey, Jonker and Thornburg89,Reference Chattergoon, Bose, Louey and Jonker121

By comparison, this surge in cortisol occurs postnatally in rats, whereby circulating corticosterone and T3 peak after birth at postnatal day 10 (P10), marking the end of cardiomyocyte maturation (Fig. 3). Reference Dimasi, Darby and Morrison56,Reference Holt and Oliver122 In fetal pigs, cardiac cortisol concentration also has a prepartum surge at ∼106 – 110 days of gestation (Term = 115 days). Reference Dimasi, Darby and Holman72 However, the impact of thyroid hormones on cardiomyocyte proliferation and nucleation has been a subject of ongoing debate. Earlier reports showed that elevated T3 concentrations inhibit proliferation and increase binucleation of fetal sheep cardiomyocytes, suggesting cardiomyocyte maturation. Reference Chattergoon, Giraud, Louey, Stork, Fowden and Thornburg58,Reference Chattergoon, Giraud and Thornburg123 This contrasts with rodents, whereby T3 triggers a brief burst of cardiomyocyte proliferation in neonates at postnatal day 15. Reference Naqvi, Li and Calvert124 More research regarding the role of T3 on cardiomyocyte proliferation is needed to provide greater mechanistic insight.

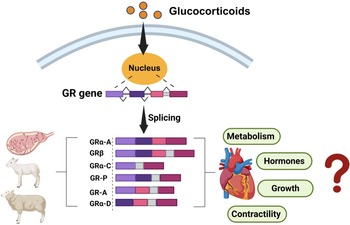

In addition to impact on thyroid hormones, GCs themselves may act to exert maturational effects on cardiomyocytes by binding to different GR isoforms. Reference Rog-Zielinska, Thomson and Kenyon125 Multiple GR isoforms are produced from a single GR gene through alternative splicing and alternative translation initiation (Fig. 4), Reference Lu and Cidlowski126 each selectively activating or suppressing the transcription of target genes. Reference Oakley and Cidlowski127 Briefly, GRα-A is the primary functional isoform, regulating various cardiac developmental genes through its interaction with genes that have GC response elements (GREs). Reference Lu and Cidlowski128 GRβ does not bind to GC agonists and is constitutively located in the nucleus of cells, where it is inactive on GC-responsive reporter genes. Reference Kino, Su and Chrousos129

Figure 4. Identification of GR isoforms in the heart of fetal, neonatal, and adult sheep. Multiple GR isoforms are generated from a single GR gene through alternative splicing and alternative translation initiation. However, the specific role of each isoform in regulating cardiometabolic pathways have not been defined. Figure made in Biorender.

However, when co-expressed with GRα, GRβ acts as a dominant negative inhibitor, antagonising the activity of GRα on numerous GC-responsive target genes. Reference Oakley and Cidlowski127 Unlike GRα-A, GRα-B, and GRα-C, which remain in the cytoplasm in the absence of hormone signalling and translocate to the nucleus upon GC binding, the GRα-D isoform is constitutively present in the nuclei of cells. Reference Oakley and Cidlowski127 Furthermore, nuclear-localised GRα-D can associate with GRE-containing promoters of specific target genes, independent of GC presence. Reference Oakley and Cidlowski127,Reference Lu, Collins, Grissom and Cidlowski130

These GR protein isoforms were only identified in select fetal tissues (placenta and lungs) of humans and sheep. Reference Saif, Hodyl and Hobbs131–Reference Orgeig, McGillick, Botting, Zhang, McMillen and Morrison133 We have recently confirmed that multiple GR isoforms can be detected (i.e., GRα-A, GRβ, GRα-C, GR-P, GR-A, GRα-D2, and GRα-D3) within the heart of fetal, neonatal and adult sheep Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa68,Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa94,Reference Amanollahi, Meakin and Holman95,Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Meakin134 ; however, the specific role of these isoforms in cardiac development requires more study (Fig. 4).

The effect of intrafetal cortisol infusion on fetal heart development

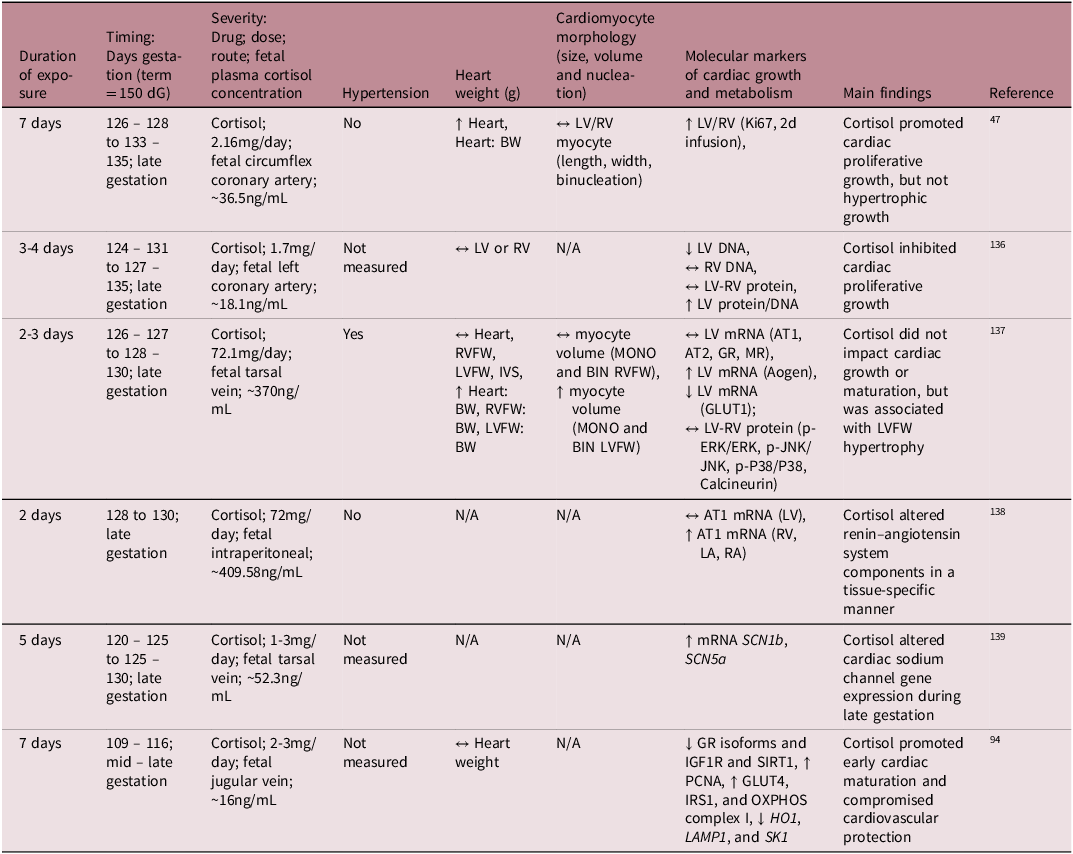

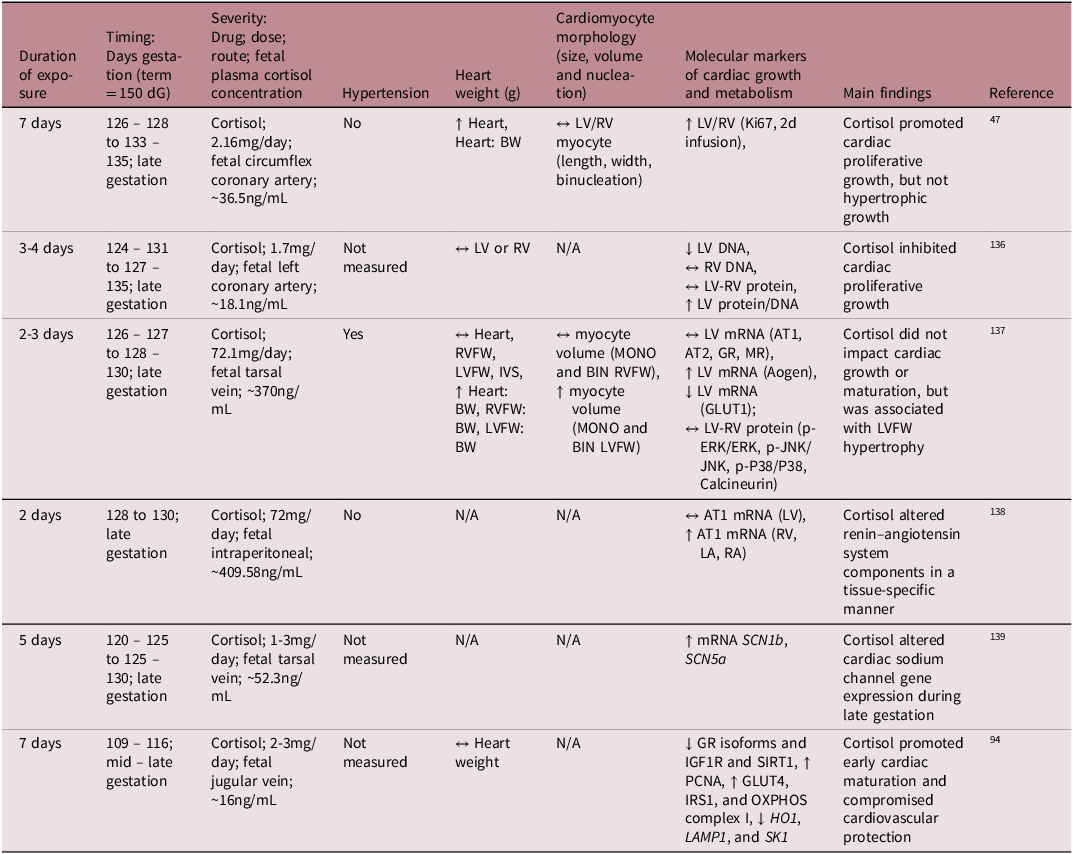

While much is understood about the broader role of cortisol in heart maturation, the specific molecular mechanisms by which the cortisol surge facilitates this process is not yet fully understood. To better understand its mechanistic role on heart development, several preclinical studies have infused cortisol directly into the fetal sheep at different gestational ages, allowing for controlled exposure without the influence of transplacental passage (Table 2). These studies demonstrated that cortisol infusion either inhibited cardiomyocyte proliferation Reference Rudolph, Roman and Gournay135 or had no effect on the rate of terminal differentiation and the total number of cardiomyocytes. Reference Lumbers, Boyce and Joulianos136 Conversely, other studies observed an increase in fetal heart mass, attributed to cardiomyocyte proliferation (hyperplasia) rather than hypertrophy. Reference Giraud, Louey, Jonker, Schultz and Thornburg47 Other studies have shown that cortisol infusion impacted aspects of the renin – angiotensin system (RAS) and altered expression of cardiac sodium channels, which may be early signs of dysregulated blood pressure mechanisms. Reference Segar, Bedell, Page, Mazursky, Nuyt and Robillard137,Reference Fahmi, Forhead, Fowden and Vandenberg138

Table 2. Summary of available literature on the effect of intrafetal cortisol infusion on fetal heart development in sheep

dG, days of gestation; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; RVFW, right ventricular free wall; LVFW, left ventricular free wall; IVS, interventricular septum; BW, fetal body weight; MONO, mononucleated; BIN, binucleated; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; ↔, no change; ↑, increase; ↓, decrease.

Cortisol elevates blood pressure when it exceeds a certain threshold and elevated blood pressure influences heart maturation Reference Barbera, Giraud, Reller, Maylie, Morton and Thornburg139 ; therefore, it is important to distinguish between sub-pressor and pressor doses (Table 2). For instance, Giraud et al. demonstrated that cortisol infusion increased plasma cortisol concentrations without affecting blood pressure and promoted cardiac proliferative growth without inducing hypertrophy. Reference Giraud, Louey, Jonker, Schultz and Thornburg47 In contrast, Lumbers et al. reported that high-dose cortisol infusion stimulated cardiac growth through hypertrophy rather than proliferation, but there was also severe hypertension. Reference Lumbers, Boyce and Joulianos136 Furthermore, the mixed cardiac growth responses to cortisol may be due to different experimental paradigms related to the timing, duration, and dose of cortisol infused. Infusion of cortisol into the mid – late gestation sheep at physiologically comparable concentrations to those that occur during the prepartum surge leads to an increase in cardiac cortisol concentrations, a downregulation of GR isoforms, a reduction in cardiac proliferation markers, and an increase in select OXPHOS complexes. Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa94 However, in the absence of GR signalling (GR-/- KO mice) in late gestation, the fetal heart metabolic and contractility profile remains immature. Reference Rog-Zielinska, Thomson and Kenyon125 Similar findings of delayed cardiomyocyte maturation were observed in the neonatal rodent heart in the absence of GR signalling. Reference Pianca, Sacchi and Umansky140

Cardiovascular consequences of excess cortisol

During a normal pregnancy, the fetus should only be exposed to moderate concentrations of GC such that only ∼ 15% of maternal cortisol crosses the placenta into the fetal circulation. Reference Murphy, Clark, Donald, Pinsky and Vedady11,Reference Reynolds14 The extent of GC transfer and fetal protection from elevated maternal cortisol concentrations is regulated by the placental expression of enzyme 11βHSD2, which serves as a critical placental barrier by converting active cortisol or corticosterone into their inactive forms, protecting the fetus from GC overexposure during pregnancy. Reference Murphy, Clark, Donald, Pinsky and Vedady11–Reference Zhu, Wang, Zuo and Sun13 Maternal stress Reference Eberle, Fasig, Brueseke and Stichling15 and pregnancy complications such as gestational diabetes, Reference Tien Nguyen, Bui Minh and Trung Dinh17 preeclampsia, Reference Aufdenblatten, Baumann and Raio18 maternal overnutrition or undernutrition, Reference Zambrano and Nathanielsz16 and placental insufficiency Reference Phillips, Simonetta, Owens, Robinson, Clarke and McMillen25,Reference Gagnon141,Reference McBride, Meakin and Soo142 can elevate circulating cortisol concentrations in both the mother and the fetus. These conditions may also compromise the placental GC barrier by reducing the abundance or activity of 11βHSD2, Reference Seckl and Holmes26,Reference Monk, Spicer and Champagne143 leading to increased fetal exposure to maternal GC (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Causes of increased intrauterine exposure to cortisol in the developing heart. Under normal pregnancy conditions, fetal GC exposure is tightly regulated. In late gestation, circulating cortisol concentrations naturally increase to support the maturation of fetal organs and prepare both the mother and fetus for birth. However, this finely tuned regulation can be disrupted by various factors, including maternal stress, pregnancy complications, certain medications, and antenatal therapies, leading to fetal overexposure to cortisol or synthetic GC. These observations highlight the double-edged role of GC in heart development in that they are essential for maturation, yet potentially harmful when present in excess or at inappropriate stages of development. However, the effects of GC on the programming of fetal cardiometabolic pathways remain largely unexplored. GC; Glucocorticoid. Figure made in Biorender.

Prolonged exposure to cortisol during pregnancy can also have significant effects on fetal health, especially in the context of maternal diabetes, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), or obesity. Reference Zambrano and Nathanielsz16–Reference Aufdenblatten, Baumann and Raio18 Elevated maternal cortisol concentrations can cross the placenta and disrupt normal fetal development, particularly affecting the HPA axis and leading to increased fetal energy consumption. Reference Diego, Jones and Field144 Evidence from women with GDM shows that higher maternal serum cortisol concentrations are positively correlated with fasting plasma glucose, insulin, triglycerides, insulin resistance indices, and fetal development. Reference Diego, Jones and Field144 In pregnancies complicated by diabetes or obesity, cortisol exposure is often exacerbated due to increased maternal stress, inflammation, and altered placental metabolism. Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel and Lahti145–Reference Darby, Chiu, Regnault and Morrison147 This combination may impair fetal cardiac structure and function, contributing to adverse cardiovascular and developmental outcomes in offspring. Reference Seckl and Holmes26

Maternal cortisol concentrations do not remain static during pregnancy, and evidence shows that the timing and trajectory of exposure can shape offspring outcomes. Reference Hahn-Holbrook, Davis, Sandman and Glynn148 A recent study identified distinct prenatal cortisol trajectories, with steeper increases across gestation predicting accelerated infant growth in the first year of life, a pattern associated with childhood overweight and obesity, known risk factors for chronic conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and CVD. Reference Hahn-Holbrook, Davis, Sandman and Glynn148,Reference Sahoo, Sahoo, Choudhury, Sofi, Kumar and Bhadoria149 These findings suggest that not only the absolute concentration but also the duration and rate of increase in cortisol during pregnancy can influence developmental programming. In the context of cardiac development, this has important implications: GC exposure in early to mid-gestation may disrupt cardiomyocyte proliferation and reduce final cardiomyocyte endowment, Reference Fowden, Li and Forhead69,Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa94,Reference Rudolph, Roman and Gournay135,Reference Fowden and Forhead150 while elevated exposure in late gestation may increase blood pressure and induce hypertrophy, Reference Lumbers, Boyce and Joulianos136,Reference Karamlou, Giraud and McKeogh151 impairing compliance and predisposing to dysfunction after birth.

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that maternal hypercortisolaemia during pregnancy alters markers of cardiac function, growth, and metabolism in fetal and neonatal lambs. Reference Li, Wood and Keller-Wood152–Reference Antolic, Li, Richards, Curtis, Wood and Keller-Wood157 Mechanistically, chronic elevation of maternal cortisol leads to fetal ventricular enlargement. Reference Jensen, Wood and Keller-Wood158 Notably, this effect does not appear to be secondary to changes in fetal blood pressure, which was not significantly altered by chronic maternal cortisol infusion, suggesting a direct effect of cortisol on cardiac development, potentially mediated by IGFs and/or renin – angiotensin signalling pathways. Reference Jensen, Wood and Keller-Wood158,Reference Reini, Wood, Jensen and Keller-Wood159 Elevated maternal cortisol in late gestation also reduces fetal cardiac expression of 11βHSD2 and IGF1R mRNA, indicating that impaired inactivation of cortisol within the fetal heart may contribute to sustained stimulation of cardiac growth. Reference Reini, Wood, Jensen and Keller-Wood159 Furthermore, chronic maternal cortisol exposure alters fetal cardiac metabolic profiles, including amino acid and TCA cycle intermediates, in both fetal and newborn cardiac tissue. Reference Walejko, Antolic, Koelmel, Garrett, Edison and Keller-Wood154 These metabolic disruptions suggest impaired maturation of cardiac metabolism prior to birth, which may underlie the increased susceptibility to peripartum arrhythmias observed in these animals or long-term cardiomyopathies. Reference Walejko, Antolic, Koelmel, Garrett, Edison and Keller-Wood154 In another study, chronic maternal cortisol infusion in late gestation impaired cardiac function in newborn lambs, as evidenced by altered electrocardiogram (ECG) and aortic blood pressure profiles. Reference Li, Wood and Keller-Wood152 These findings indicate that cortisol affects the cardiac conduction system, consistent with the effects on calcium signalling. Reference Antolic, Li, Richards, Curtis, Wood and Keller-Wood157 Overall, these findings reinforce our recent results, indicating that excessive in utero exposure to the stress hormone cortisol can adversely affect fetal heart development, Reference Amanollahi, Holman and Bertossa94 potentially predisposing offspring to CVD later in life (Fig. 5).

Cardiovascular consequences of ART

In 1978, the world saw the first successful in vitro fertilisation (IVF) pregnancy, marking the beginning of rapid advancements and growth in assisted reproductive technology (ART). Reference Steptoe and Edwards160,Reference Zhao, Brezina, Hsu, Garcia, Brinsden and Wallach161 While ART has provided significant benefits for reproductive success, it can induce stress for both the mother and fetus Reference Osborne, Shin, Mehta, Pitman, Fayad and Tawakol162,Reference Wei, Paradis, Ayoub, Lewin and Auger163 such that women who conceived via ART have higher plasma cortisol concentrations in the first trimester and greater stress in the third trimester compared to those who conceived naturally (Fig. 5). Reference Caparros-Gonzalez, Romero-Gonzalez, Quesada-Soto, Gonzalez-Perez, Marinas-Lirola and Peralta-Ramírez49 This finding is concerning given that late gestation is a critical window of rapid cardiac growth and maturation. In addition to the risk associated with excess GC exposure, ART also involves manipulation of the embryo, and the constituents of the culture media may create a suboptimal in utero environment that may affect epigenetic traits, leading to altered cardiovascular phenotypes in offspring (Fig. 5). Reference Dancause, Veru, Andersen, Laplante and King20 These combined risk factors could negatively impact fetal cardiac development and contribute to poor cardiovascular outcomes in ART-conceived offspring. Reference Padhee, Zhang and Lie164,Reference Padhee, Lock and McMillen165

Recent evidence in humans suggests that ART-conceived fetuses are at increased risk of CVD due to cardiac remodelling, Reference Tasias, Papamichail, Fasoulakis, Theodora, Daskalakis and Antsaklis166 in addition to known altered cardiac morphometry and function. Reference Valenzuela-Alcaraz, Crispi and Bijnens51 Similar outcomes are observed in childhood, Reference Scherrer, Rimoldi and Rexhaj167,Reference Reefhuis, Honein and Schieve168 and these persist into adolescence. Reference Von Arx, Allemann and Sartori50 Increased blood pressure in ART-conceived offspring compared to those conceived naturally has also been reported in humans. Reference Cui, Zhao and Zhang169–Reference Sakka, Loutradis and Kanaka-Gantenbein173 In sheep fetuses, ART increases the growth rate of the heart, Reference Sinclair, McEvoy and Maxfield174 such that heart weight in late gestation is increased. Reference Rooke, McEvoy and Ashworth175,Reference Powell, Rooke and McEvoy176 Even fewer studies have investigated the underlying mechanisms at the molecular level. However, there is an association between ART and an increase in fetal heart growth with an increase in the pathological hypertrophy marker, IGF2R, Reference Powell, Rooke and McEvoy176,Reference Young, Fernandes and McEvoy177 which is an established CVD risk factor in fetuses born to complicated pregnancies. Reference Wang, Botting and Padhee2,Reference Wang, Botting, Zhang, McMillen, Brooks and Morrison59–Reference Morrison, Botting, Dyer, Williams, Thornburg and McMillen63,Reference Darby, McMillen and Morrison178 In low-birth-weight lambs, histone H3K9 acetylation was elevated at both the IGF2R promoter and the differentially methylated region within intron 2, resulting in an increased risk of left ventricular hypertrophy and CVD in adult life. Reference Wang, Tosh and Zhang179

These epigenetic changes may be further influenced by altered GC exposure, as women who conceive via ART often exhibit higher cortisol concentrations throughout pregnancy. Reference Caparros-Gonzalez, Romero-Gonzalez, Quesada-Soto, Gonzalez-Perez, Marinas-Lirola and Peralta-Ramírez49,Reference Barnes, Sutcliffe and Kristoffersen52 Additionally, ART pregnancies may alter cardiac development indirectly via impaired placental function Reference Sakian, Louie and Wong180 , potentially increasing fetal cortisol exposure. Nevertheless, the mechanisms linking ART-associated cardiovascular risk to fetal exposure to excess GC remain poorly understood and warrant further investigation.

Cardiovascular consequences of antenatal GC

When preterm delivery is anticipated, the standard protocol in many countries recommends administration of synthetic GC (either betamethasone (12 mg in two doses over 24 h) or dexamethasone (6 mg in four doses over 24 h) 48 h before anticipated delivery. 30,31 Betamethasone and dexamethasone readily cross the placenta without being degraded by placental 11βHSD2, Reference Kemp, Newnham, Challis, Jobe and Stock181 allowing for rapid maturation of the fetal lungs, thus preventing respiratory distress syndrome. Reference Ballard and Ballard182,Reference Thevathasan and Said183 Despite their widespread use in clinical practice, the broader off-target impacts of this GC treatment on other fetal organs, such as the heart, remain unclear (Fig. 5). However, it is necessary to understand, especially with emerging evidence suggesting that GC treatment may perturb the development of other vital fetal organs, such as the brain. Reference Jobe and Goldenberg38–Reference Moss, Doherty, Nitsos, Sloboda, Harding and Newnham40

In animal models of normal pregnancy, maternal betamethasone or dexamethasone administration in late pregnancy can cause fetal blood pressure to rise in sheep. Reference Derks, Giussani and Jenkins184–Reference Bennet, Kozuma, McGarrigle and Hanson186 and primates Reference Koenen, Mecenas, Smith, Jenkins and Nathanielsz187 Prenatal GC treatment in late gestation also alters basal cardiac function, including reduced cardiac output in fetal sheep. Reference Miller, Supramaniam, Jenkin, Walker and Wallace188,Reference Fletcher, McGarrigle, Edwards, Fowden and Giussani189 In rodent fetuses, antenatal GC in late pregnancy can reduce heart weight Reference Mosier, Dearden, Jansons, Roberts and Biggs190,Reference O’Sullivan, Cuffe and Paravicini191 and at the molecular level, downregulate cardiac GR protein and interfere with the normal maturational swift towards fatty acid metabolism. Reference Ivy, Carter and Zhao43 In chicken embryos, GC treatment also downregulated cardiac GR protein abundance, resulting in fewer but larger cardiomyocytes, leading to fetal cardiac dysfunction. Reference Garrud, Teulings and Niu192

In newborn sheep and baboon offspring, hypertension persists after exposure to antenatal GC at various points in pregnancy, Reference Dodic, May, Wintour and Coghlan193,Reference von Bergen, Koppenhafer and Spitz194 possibly related to altered baroreflex mechanisms. Reference Segar, Roghair, Segar, Bailey, Scholz and Lamb195 There is conflicting evidence of neonatal changes at the molecular level in the heart. Preterm treatment with betamethasone promoted indices of cardiac maturation as evidenced by increased binucleation, transition to terminal differentiation and improved cardiac function in piglets, Reference Kim, Eiby and Lumbers46 but there was no overall impact on cardiovascular physiology in sheep. Reference Jobe, Polk, Ervin, Padbury, Rebello and Ikegami196 This contrasts with neonatal changes in rodents exposed to dexamethasone, including cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and reduced DNA content, Reference Slotkin, Seidler, Kavlock and Bartolome197 as well as indices of delayed cardiac maturation. Reference Torres, Belser, Umeda and Tucker198

In adulthood, prenatal GC exposure can lead to HPA axis programming in guinea pigs Reference Liu, Li and Matthews199 likely contributing to increased production of cardiac mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) in young adult sheep. Reference von Bergen, Koppenhafer and Spitz194 Moreover, antenatal GC programmes hypertension and indices of cardiac hypertrophy in baboon, sheep and rodent offspring in adolescence through to adulthood Reference O’Sullivan, Cuffe and Paravicini191,Reference Dodic, May, Wintour and Coghlan193,Reference Levitt, Lindsay, Holmes and Seckl200–Reference Langdown, Holness and Sugden203 and abnormal fat deposition around the adult primate heart. Reference Kuo, Li and Li204

Overall, antenatal GC exposure impacts cardiovascular development, with effects that may be shaped by species and timing of exposure. In animal models, GCs raise blood pressure, reduce cardiac output, and disrupt growth and metabolic maturation in the fetus. Reference Ivy, Carter and Zhao43,Reference Amanollahi, Meakin and Holman95,Reference Derks, Giussani and Jenkins184–Reference Garrud, Teulings and Niu192 Long-term, GC exposure has been shown to programme hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy across animal models, including primates, sheep, and rodents. Reference Kim, Eiby and Lumbers46,Reference O’Sullivan, Cuffe and Paravicini191,Reference Dodic, May, Wintour and Coghlan193,Reference von Bergen, Koppenhafer and Spitz194,Reference Slotkin, Seidler, Kavlock and Bartolome197,Reference Torres, Belser, Umeda and Tucker198,Reference Levitt, Lindsay, Holmes and Seckl200–Reference Kuo, Li and Li204 Human studies also link antenatal GC with elevated adolescent blood pressure, Reference Doyle, Ford, Davis and Callanan205 reinforcing concern over lasting cardiovascular risk. Despite this evidence, major gaps remain. It is still unclear whether the adverse outcomes are primarily driven by direct binding of GCs to cardiac GRs or by indirect mechanisms such as placental dysfunction, disrupted thyroid hormone signalling, or altered HPA axis programming. Additionally, the extent to which the timing of exposure (early, mid, or late gestation) influences the resulting phenotype remains unresolved. Addressing these questions is critical for refining antenatal GC therapy to balance life-saving respiratory benefits against potential long-term cardiovascular risks.

Conclusion

This review highlights the double-edged role of GC on heart development. Under normal pregnancy conditions, circulating cortisol concentrations naturally rise during late gestation to support fetal organ maturation and prepare both the mother and fetus for birth. However, this finely tuned physiological regulation can be disrupted by various factors such as maternal stress, pregnancy complications, specific medications, antenatal therapies, and ART, potentially leading to fetal overexposure to endogenous or synthetic GC. The effects of such exposure on the fetal heart are highly variable and influenced by timing, duration, and dose. Understanding the precise role of GC in influencing cardiac development is essential to disentangle the beneficial effects from potential harms on the fetal cardiometabolic profile. Nevertheless, the mechanisms through which both physiological and pathological elevations in GC concentrations programme fetal cardiometabolic pathways and influence long-term cardiovascular outcomes remain poorly understood. These uncertainties call for further mechanistic research to identify key molecular targets that may help mitigate the adverse cardiac effects of GC exposure, thereby minimising long-term cardiovascular risks.

Data availability

All data supporting the results are presented in the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from members of the Early Origins of Adult Health Research Group.

Author contribution

Conception or design of the work: RA, MCL, KLT, JLM

Acquisition or analysis or interpretation of data for the work: RA, MRB, MCL, MDW, KLT, JLM

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: RA, MRB, MCL, MDW, KLT, JLM

Final approval of the version to be published and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work: all.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial support

R.A. was funded by a University of South Australia President’s Scholarship, and M.R.B was funded by the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.