Introduction

Even though U.S. regulations under 42 CFR §483.80 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) mandate structured Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs (ASPs) in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), meeting regulatory minimums does not guarantee clinically effective stewardship. Reference Stone, Herzig, Agarwal, Pogorzelska-Maziarz and Dick1 SNFs continue to exhibit substantial gaps in prescribing quality with approximately 1 out of every 10 residents are actively receiving an antibiotic and around 50% of prescriptions deemed inappropriate in indication, dose, or duration. Reference Thompson, LaPlace and Epstein2,Reference Rancourt, Moisan, Baillargeon, Verreault, Laurin and Grégoire3 Inappropriate antibiotic practices directly contribute to elevated rates of antimicrobial resistance, Clostridioides difficile infection increases, and worse patient outcomes. Reference Rodríguez-Villodres, Martín-Gandul and Peñalva4,Reference Appaneal, Shireman and Lopes5

Following the 2016 CMS regulation self-reported progress has been substantial with adherence to stewardship best practices rising from 42% to 83% among facilities participating in the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). Reference Palms, Kabbani, Bell, Anttila, Hicks and Stone6,Reference Luciano, Kabbani and Neuhauser7 Yet important gaps remain. A state-based survey beyond just NHSN facilities indicated only 67% of facilities report access to infectious diseases expertise, suggesting NHSN-reporting facilities may not be representative. Reference Mosleh, Clements, Beard, Weil, Radloff and Schenk8 Moreover, even among NHSN-reporting facilities less than one-third use electronic health records for antibiotic use tracking. Reference Luciano, Kabbani and Neuhauser7 These are not minor oversights as prospective audit with feedback from infectious diseases experts is a core driver of ASP success, and accurate tracking is essential for measuring impact. Reference Doernberg, Abbo and Burdette9 Consequently, program effectiveness varies widely despite CMS requirements.

While CMS regulations specifically target SNFs, the evidence base for effective antimicrobial stewardship spans the broader landscape of long-term care. Accordingly, this review synthesizes these evidence-based interventions for application across all long-term care facilities (LTCFs), grounding them in the specific CMS requirements for SNFs and highlighting practical, LTCF-specific tools for implementation and measurement. Reference Proctor, Ramsey, Saldana, Maddox, Chambers and Brownson10

Evidence on ASP interventions in LTCFs

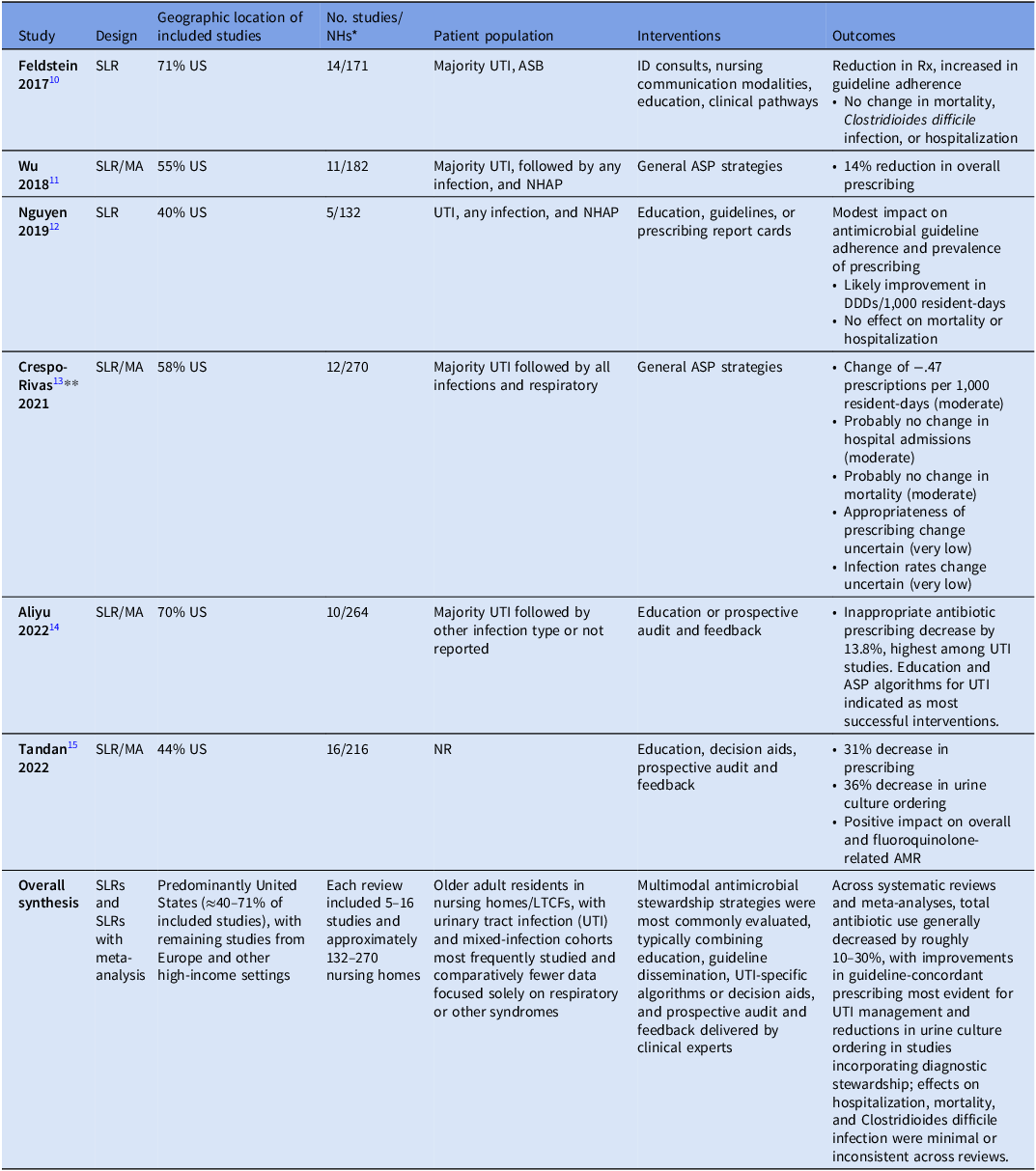

The literature on antimicrobial stewardship in long-term care has expanded dramatically since the 2016 CMS regulations, with publications indexed by the National Library of Medicine rising from just ten in the three years prior to a peak of 63 in 2021. 11 Recent systematic review literature (SLR) summaries as well as newer randomized controlled trials and public health government-sponsored quality improvement projects provide critical insights into the effectiveness of various interventions (Table 1). Across SLRs, most studies were conducted in the United States, ranging from 40% to 71% of studies. Reference Feldstein, Sloane and Feltner12–Reference Tandan, Thapa, Maharjan and Bhandari17 The number of studies included among SLRs ranged from 5 to 16 studies and 132 to 270 LTCFs reflected among the SLRs.

Table 1. Systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses of ASP interventions in LTCFs

* NHs may overlap across studies; included for context, not weight.;

** GRADE certainty of evidence ratings for outcomes in parentheses; AMR, antimicrobial resistance; ASB, asymptomatic bacteriuria; DDD, defined daily dose; NHAP, nursing home associated pneumonia; NR, not reported; Rx, prescriptions; US, United States; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Consistently, urinary tract infections (UTI) interventions were the most common syndrome targeted, though categories of “all infection types” and respiratory interventions were frequent as well. These interventions moved beyond general education, specifically targeting the differentiation of asymptomatic bacteriuria from active infection to reduce unnecessary initiation, optimizing agent selection, and reducing duration of therapy. Most studies involved multimodal interventions with activities including educational strategies, clinical practice guidelines, local consensus process, audit and feedback, patient-mediated interventions, tailored interventions, continuous quality improvement, care pathways, infectious diseases team, and information/communication technology. Reference Crespo-Rivas, Guisado-Gil and Peñalva15 Where these interventions were quantified by type, total interventions per study ranged from 2 to 7 with a median of 3. Reference Crespo-Rivas, Guisado-Gil and Peñalva15

While these SLRs confirm the efficacy of multimodal strategies, they often lack granular guidance on which specific interventions yield the highest return on investment for resource-constrained facilities. Similar resources for other general public health initiatives are routinely compiled by the CDC. 18 Consequently, recent research has pivoted from general efficacy reviews to expert consensus and behavioral science frameworks to prioritize implementation. Unlike the CDC Core Elements, which provide the structural framework for what a program should contain, these data offer guidance on how to prioritize actions when resources are limited.

Kruger et al conducted a multiphase modified Delphi method using a 16-member multidisciplinary panel of experts and resident representatives to facilitate the selection and adoption of interventions through consensus prioritization. Reference Kruger, Bronskill, Jeffs, Steinberg, Morris and Bell19 Their results reflect a descending prioritization of (1) guidelines for empiric prescribing, (2) audit and feedback, (3) communication tools, (4) short-course antibiotic therapy, (5) scheduled antibiotic reassessment, and (6) clinical decision support systems. Interestingly, many interventions were not supported, including nursing home antibiograms, educational interventions, formulary review, and automatic substitution.

Enriching the perspective offered by the modified Delphi study, Crayton et al performed a systematic review to identify interventions targeting antibiotic use in LTCFs and then apply behavioral science frameworks for classifying intervention types and component behavior change techniques used. Reference Crayton, Richardson and Fuller20 Interventions were classified as “very promising” if all outcomes were statistically significant, “quite promising” if some were significant, and “not promising” if all were non-significant. Among 20 studies, they found most promising interventions included “persuasion” (communication to stimulate action; eg., infectious diseases physician communication to reinforce messaging from education, guidelines), “enablement” (increasing capability; eg., feedback case sessions), and “education” (increasing knowledge and understanding; eg., guidelines). Additionally, they identified the most promising behavior change techniques included “feedback on behavior” (monitoring and giving information on performance behavior; eg., qualitative factors influencing prescribing) and restructuring the social environment (eg., staff role changes). The results of this SLR can facilitate planning of future interventions or refinement of current activities. Similarly, Colin et al performed a systematic review and mixed methods appraisal of implementation strategies for ASPs in LTCFs. Reference Conlin, Hamard and Agrinier21 Using data from 48 studies, they mapped strategies and outcomes to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) framework. Forty percent of studies included one of three ERIC domains including education and training, evaluative and iterative strategies, and support clinicians. Implementation frameworks, models, or theories were only used in 17% of studies. More research on dissemination and implementation strategies to localize interventions for ASPs in LTCFs are needed.

Resources and tools for antimicrobial stewardship in LTCF

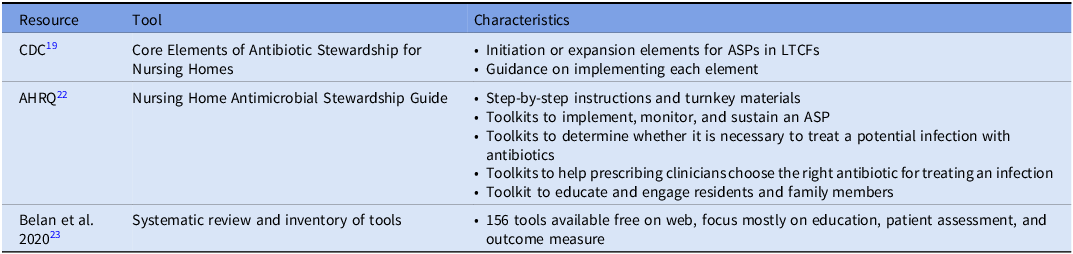

While evidence and guidance on prioritization of interventions and approaches for implementation strategy are still evolving, many tools exist to facilitate establishing ASPs and improving antimicrobial use in LTCFs (Table 2). A primary starting tool is the CDC’s Stewardship for Nursing Homes. Reference Conlin, Hamard and Agrinier21 Designed to guide the initiation and expansion of ASPs, this framework outlines seven structural components. To ensure structural support, facilities must establish Leadership Commitment (demonstrating administrative support), Accountability (identifying medical, nursing, and pharmacy leads), and Drug Expertise (accessing consultant pharmacists with infectious diseases training). Operational success relies on Action (implementing policies to improve use), Tracking (monitoring process and outcome measures), and Reporting (providing regular feedback to staff). Finally, Education ensures that clinicians, residents, and families understand the risks of resistance. Rather than a rigid checklist, the framework encourages stepwise implementation. Promisingly, NHSN Long-Term Care Facility Component annual surveys have reflected by 2018, 83% of nursing homes reported implementation of all 7 core elements of CDC core elements of antimicrobial stewardship in nursing homes. Reference Luciano, Kabbani and Neuhauser7 Notably, a similar outline of guidance from the Dutch Working Party on Antibiotic Policy (Dutch acronym “SWAB”) has been developed from their efforts on implementing ASPs in one of the largest nursing home care providers in the Netherlands. Reference Eikelenboom-Boskamp, Van Loosbroek and Lutke-Schipholt22

Table 2. Resources and tools for AMS in LTCF

For facilities seeking ready-to-implement interventions to operationalize these elements, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Nursing Home Antimicrobial Stewardship Guide serves as the primary practical resource. 23 Based on low, medium, or high availability of resources, ASPs can select among potential goal areas in identifying potential problems, helping clinicians identify an infection, helping clinicians choose the right antibiotic, and educating residents and family members. Each goal area has specific ready-to-use resources for implementation such as a “Be Smart About Antibiotics” education sheet for residents to inform them on appropriate and inappropriate use of antibiotics, risks of antibiotics, and what they can do to help be good stewards. 24 Notably, a study by the AHRQ using these tools along with education through webinars among 439 LTCFs, reflected an overall decrease in total antibiotic courses with fluoroquinolones reflecting the largest decrease, and antibiotic course reductions were greatest at facilities with the most webinar attendance while low engagement facilities lacked an impact on course reductions. Reference Katz, Tamma and Cosgrove25 Finally, the tools and program were associated with a significant decrease in urine cultures ordered.

While the AHRQ guide provides a curated set of standard interventions, facilities with unique needs or those seeking to refine specific program aspects may require a broader repository of tools. In 2020, Belan et al published a systematic review and inventory of tools on ASPs in nursing homes. Reference Belan, Thilly and Pulcini26 In total, 156 freely available tools were identified from the literature found in their review. The majority of tools focused on education and practical training (n = 58) or other actions aiming at responsible antimicrobial use (n = 58; diagnosis/algorithms, communication / assessment, microbiology testing, and antibiograms). Other identified tool categories included management leadership, accountability and responsibility, available expertise on infection management, monitoring and surveillance, reporting and feedback, and general recommendations for implementation. The inventory of these tools is available in their supplementary materials of their article with institution, description, format of material, and weblink provided.

Finally, regarding tools for monitoring and surveillance, recent efforts have developed LTCF-specific methods to address resource limitations. Research from Song et al used pharmacy invoices from the dispensing pharmacy for the facilities as a data source for tracking and reporting antibiotic use in nursing homes. Reference Song, Wilson, Marek and Jump27 They outline the steps of data cleaning, calculating census of bed days of care as well as using publicly available bed allocations per nursing home, and generating several antibiotic use metrics including days of antibiotic therapy, length of antibiotic therapy, rate of antibiotic starts, and antibiotic spectrum index. Finally, they created an easily accessible template for summarizing data within and across facilities. In the absence of such data, other research has reflected performing a point prevalence survey across 18 facilities required less than 2 hours for a 100-bed facility, an approach that could be repeated multiple times a year to facilitate tracking. Reference Heudorf and Stalla28 Benchmarking antibiotic use metrics in LTCFs is still being evaluated by the CDC. Reference Dickinson, Gouin, Neuhauser, Benedict, Cincotta and Kabbani29,Reference Kabbani, Wang and Ditz30

Conclusions

In conclusion, antimicrobial stewardship in LTCFs has rapidly evolved in recent years from establishing feasibility to optimizing impact. Evidence-based interventions, such as educational strategies, clinical practice guidelines, and audit and feedback, have demonstrated efficacy in reducing inappropriate antibiotic use and enhancing guideline adherence, especially in the management of UTIs. The availability of comprehensive tools and resources, like the CDC’s Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship for Nursing Homes and the AHRQ’s Nursing Home Antimicrobial Stewardship Guide, provides essential support for implementing and sustaining ASPs (ASPs). However, a critical gap remains between identifying effective interventions and successfully implementing them. As noted in our review of implementation strategies, only 17% of studies utilized formal frameworks to guide adoption, and research on behavioral drivers (eg., “persuasion,” “enablement”) is limited compared to traditional clinical outcomes. Consequently, future research must pivot from testing new clinical guidelines to evaluating the implementation strategies required to change prescribing culture. Specifically, rigorous investigation is needed to determine which behavioral techniques most effectively sustain stewardship in settings with high staff turnover and limited infectious diseases expertise.

Acknowledgements

The work of T.T.T. on this manuscript was done as part of his MPH program internship requirements at East Tennessee State University.

Financial support

This work was not funded.

Competing interests

None of the authors report any relevant conflict of interest.